Background: A reassuringly pernicious flaw in the fabric of autocratic regimes is the disconnect that can emerge between those in power and those they rule [

1]. In the absence of regular, free-and-fair elections, the legitimacy and self-confidence of these regimes must rely instead on whatever insight their internal security and political cadres can discern. Yet such insight is fraught with bias. Loyal apparatchiks – keen to curry favour and advance their own positions – have a vested interest in reassuring the leadership of popular support even when this is thin on the ground. In contrast, those delivering more balanced but less welcome news, may find this dismissed as inaccurate, heretical or dangerously subversive [

2].

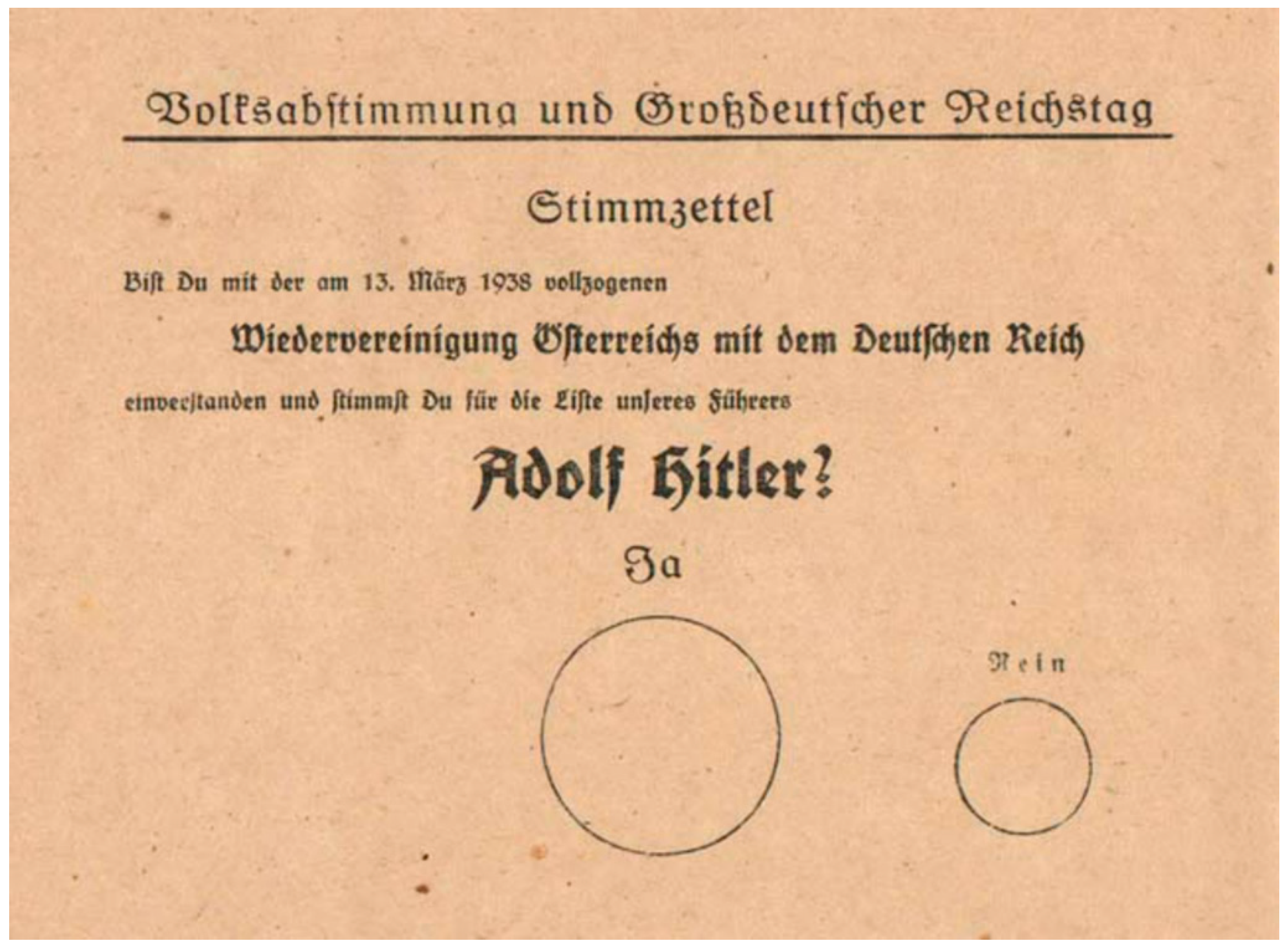

At the same time, a ‘spiral of silence’ can suppress public disclosure of popular disillusion or discontent, even when this has

not been actively discouraged, suppressed or outlawed [

3]. Indeed, self-censorship alone can subvert any measures autocracies might take to gauge or demonstrate public opinion [

4], including continuing to hold ostensibly democratic elections and plebiscites (as Nazi Germany did up until 1938) – rendering the results of these polls inherently untrustworthy or, quite literally, incredible. Germany’s 1938 election, for example, delivered a turnout of 99.6%, with 99.1% in favour of the only candidates allowed on the ballot, these being: “the list of [candidates approved by] our Führer, Adolf Hitler” (see

Figure 1) [

5].

Measuring the

genuine opinions of populations subject to autocratic rule therefore offers a tantalising opportunity for adversaries to exploit any unacknowledged weaknesses in popular support by assessing the morale and loyalty of those required (and relied upon) to do the regime’s bidding [

6].This is what lay behind Geoffrey Pyke’s 1939 attempt to gauge what ordinary Germans thought about the Nazis – and about the prospect of war with Britain, France and Russia. Without the formal support or backing of officials in Whitehall, Pyke – who John Desmond Bernal FRS described as “one of the most ingenious and original minds I know” – concocted an audacious and breathtakingly simple scheme to persuade Germany’s leaders that they lacked the popular support required for war.

‘Maudsley’, OpSec and tradecraft: In 1938, with the threat of another European war looming, Pyke set out to recruit German-speaking ‘conversationalists’ who would be willing to visit Germany and record the views of ordinary Germans whilst posing as tourists – a freelance operation nonetheless organised in great secrecy under the codename ‘Maudsley’.

Pyke had previous form in this regard, having travelled to Germany on a false passport in 1914 to document the views of ordinary Germans for the

Daily Chronicle (through ad hoc conversations, and by eavesdropping) only to be swiftly arrested by the authorities and held in Ruhleben internment camp before escaping and making his way back to England in 1915 (and to some acclaim, being the first British citizen to enter and leave Germany during the course of the Great War) [

7].

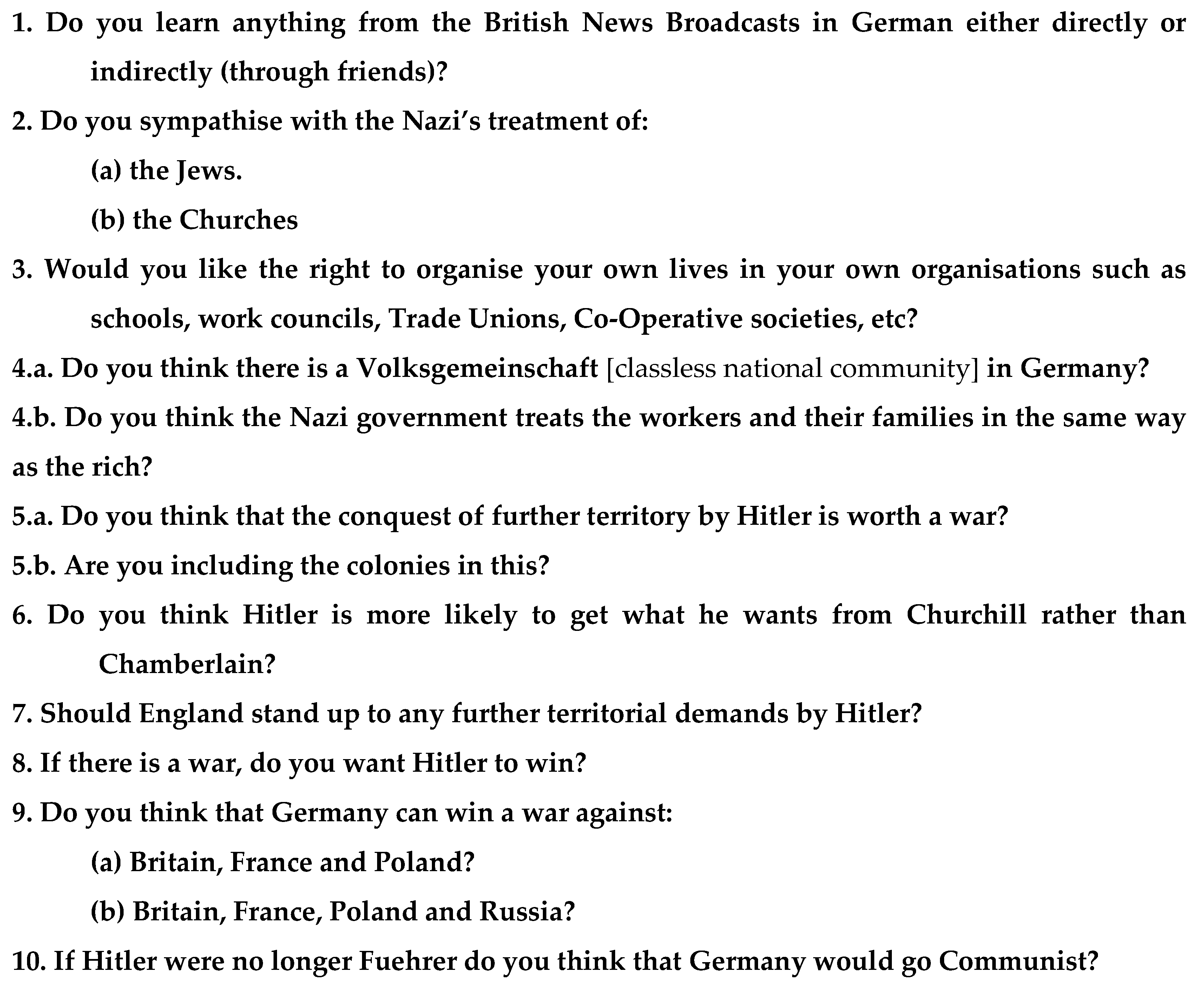

Paying close attention to the technical innovations pioneered by Gallup’s American Institute of Public Opinion (which had been founded just three years before, in 1935) [

8], Pyke carefully crafted the wording and sequence of the questions his pollsters would ask (see Figure 2); and gave considerable thought to the range of respondents they should approach in order to ensure that the views they recorded would accurately reflect those of the population as a whole.

Recognising that evidencing his survey’s validity would be critical to its utility in the subsequent influence operations he had in mind – which included persuading President Roosevelt to broadcast the survey’s results – Pyke even arranged for five of his ‘conversationalists’ to operate independently in the same city for several days (and unbeknownst to one another) to evaluate (and demonstrate) the comparability and consistency of their findings. Meanwhile, the suitability of potential pollsters was independently (and anonymously) assessed by a respected German refugee (Rolfe Rünkel – operating under the alias “Professor Higgins”) – who was tasked with vetting each of the applicants and ensuring they could accurately recall not only the questions (which they were required to slip into the conversations they struck up with ordinary Germans), but also the answers to each of these questions (which would need to be written down afterwards, and in private – often only by retreating to the rest room of a nearby bar or restaurant).

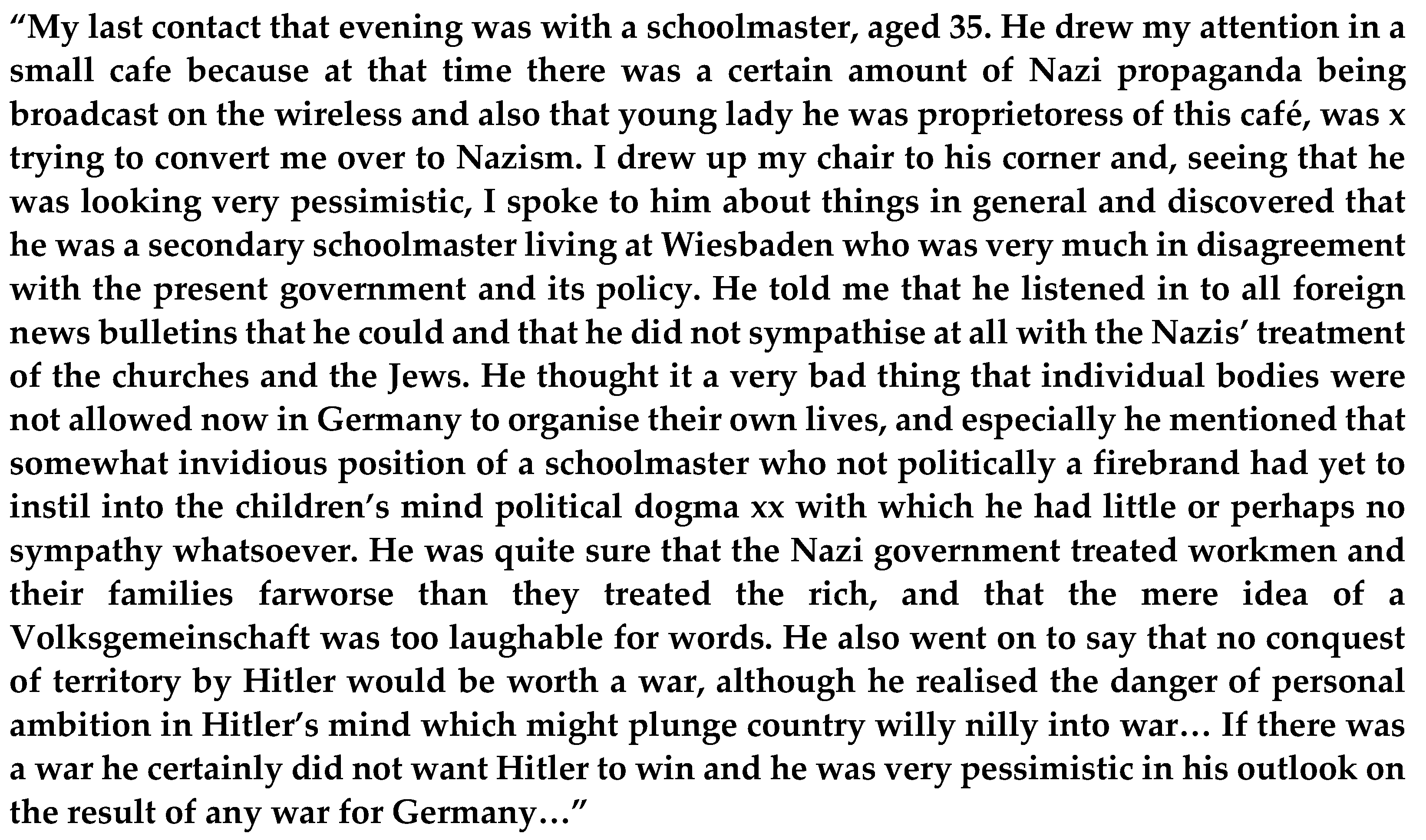

Instructed by Pyke to conform to the popular and affectionate German caricature of the eccentric and comfort-obsessed English tourist abroad, Pyke’s amateur pollsters had an unforeseen advantage over their professional counterparts. The necessity of concealing their true identities and intentions gave them licence to contrive a level of rapport that appeared to have substantially attenuated any recourse to response bias or the vagaries of self-censorship. Indeed, when sharing their views and opinions with these amiable foreigners, it is clear that Pyke’s instructions had a disarming effect on a good many of the Germans they approached – making them much more willing to share what they

actually thought (see

Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Verbatim reproduction of the sequence of questions Pyke devised for his 1939 survey of German public opinion.

Figure 2.

Verbatim reproduction of the sequence of questions Pyke devised for his 1939 survey of German public opinion.

Figure 3.

Verbatim excerpt from the typed transcript of notes made by one of Pyke’s ‘conversationalist-interviewers’.

Figure 3.

Verbatim excerpt from the typed transcript of notes made by one of Pyke’s ‘conversationalist-interviewers’.

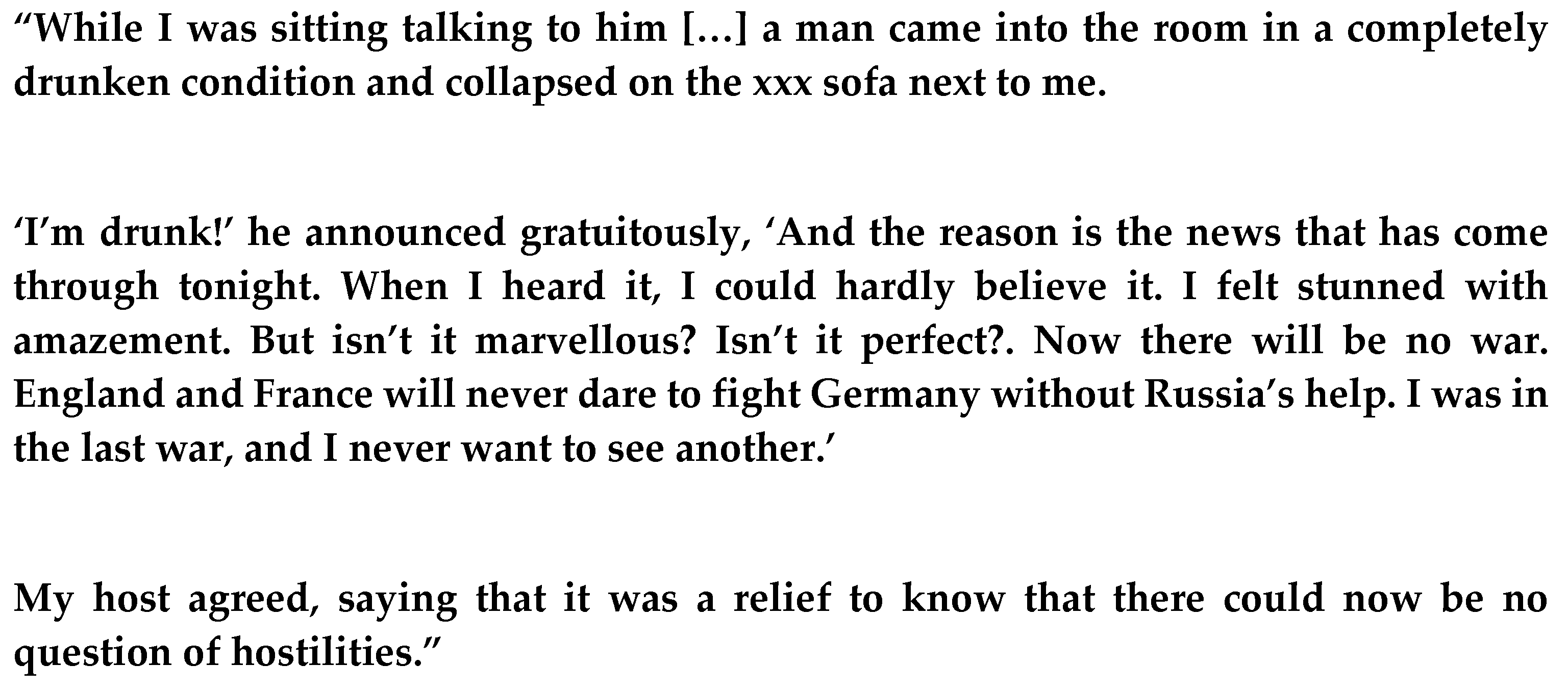

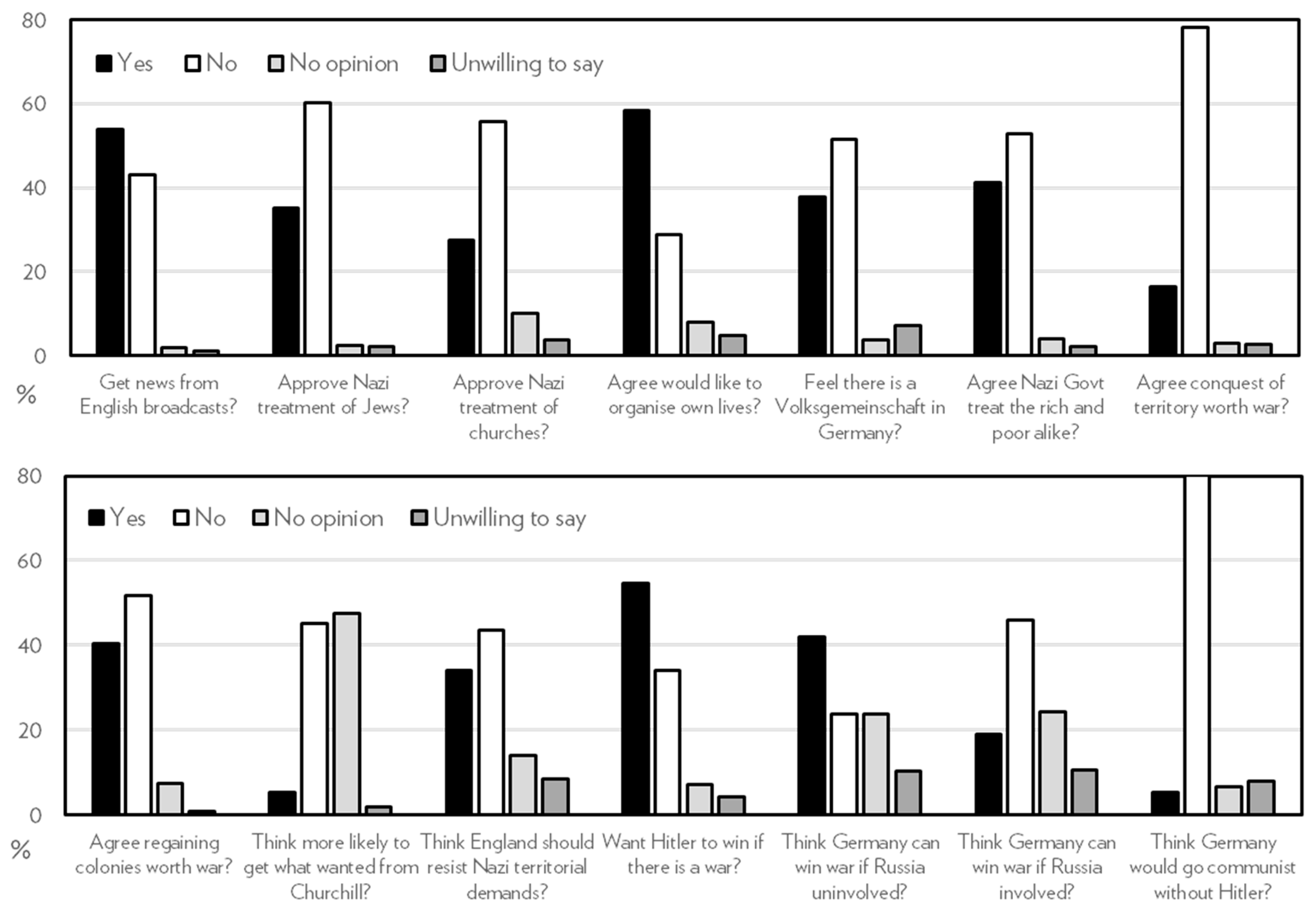

Findings: Although Pyke’s 10 amateur pollsters managed to complete 232 interviews in 14 cities during their first 2 weeks in Germany (keeping in touch with Pyke through coded postcards sent to a range of third-party addresses in the UK; see

Figure 4) the success of the scheme was overtaken by events when – on 21st August 1939 – they witnessed first-hand the dramatic shift in public opinion that took place when news leaked of the impending Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (see

Figure 5). Forced to abandon any further survey work, they were lucky to escape home before the outbreak of war. Undeterred, Pyke promptly wrote up and circulated a summary of his survey’s findings – which suggested that a good many of the Germans his ‘conversationalists’ had spoken to were far from supportive of the Nazi’s policies and territorial ambitions (see

Figure 6).

Follow-up: Pyke then worked tirelessly to adapt his scheme to the changed situation in Europe: one of several ideas being to involve US citizens (who, as neutrals, would still have been able to travel freely to, and within, Germany); another being to import German-language newspapers for subsequent analysis (an idea rejected by HMG’s Board of Trade, who were worried about the cost in terms of scarce foreign currency); and, (perhaps the most inspired of all) the notion of dispatching foreign hairdressers via Switzerland (an idea that sprang to mind, unsurprisingly, whilst having his hair cut by a Russian barber – one of many who had worked in Germany and spoke fluent German).

Despite the tangible merits of these ideas, the truth of the matter was that once the Phoney War was over and the defeat of France took shape, few in HMG believed that evidence of lacklustre public support would persuade the Nazi leadership to suspend hostilities – and not least while they were winning on the battlefield, and popular support for the regime approached its zenith.

Nonetheless, the legacy of Pyke’s unique experiment in covert sentiment analysis is evident in the enduring relevance of audience analysis, the human terrain, and ‘the will to fight’ in all subsequent conflicts to this day [10]. It also offers an under-explored insight into the elusive possibility of peace in 1939; and the paucity of popular support for the Nazi’s domestic and international policies on the eve of the Second World War.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to Henry Hemming and the staff of The Churchill Archives Centre (in particular Cherish Watton and Andrew Riley) for their assistance in locating and accessing the materials required to undertake this research; which was only possible with RSDs generously provided by the RAFC’s BSG, and 11Gp’s IntResWg. Thanks also to Ralph Ellison for his prompt assistance with German translations.

References

- Unger, A.L. The public opinion reports of the Nazi party. Public Opinion Quarterly 1965, 29, 565–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGruddy, J. Talking truth to power for the Intelligence Professional – feeling the fear and doing it anyway! Journal of Strategic Security 2013, 6, 221–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheufle, D.A.; Moy, P. Twenty-five years of the spiral of silence: A conceptual review and empirical outlook. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 2000, 12, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, G.T.H. A bump in domestic approval offers little reassurance for Putin’s military strategy. UK Defence Journal 2024, Oct 17.

- Hamilton, R.F. Who voted for Hitler? Princeton University Press; 2014 – se also: Database and Search Engine for Direct Democracy. Deutsches Reich, 10. April 1938: Anschluss Österreichs; Reichstagliste.

- Berinsky, A.J. Public opinion and international conflict. In: Emerging Trends in the Social and Behavioral Sciences (Ed.s Scott RA, Kosslyn SM). Wiley Inc; 2015.

- Pyke, G. To Ruhleben - and Back: A Great Adventure in Three Phases. Constable and Company Ltd.; 1916.

- Gallup, G.; Rae, S.F. The Pulse of Democracy: The Public-Opinion Poll and How it Works. Simon and Schuster; 1940.

- Arquilla J, Borer DA (Ed.s) Information Strategy and Warfare: A Guide to Theory and Practice. Routledge; 2009.

Author Biographies

George Ellison DSc is Professor of Data Science at the University of Central Lancashire. His research focuses on the social production of knowledge, and on the role of cognitive, conceptual and methodological issues within contemporary epistemology and intelligence practice. https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8914-6812

Robert (Bob) Mattes PhD is Professor of Politics at the University of Strathclyde. A specialist in survey methodology, he is co-founder and Senior Adviser of Afrobarometer, a regular social and political survey of over 30 countries in Africa. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0567-9385

Andrew Shepherd MA joined the MOD in 2005 and has been employed in a number of operationally focused roles. Since 2010, he has been involved in the development of intelligence-linked information and influence methodologies; and the design of a number of innovative wargames on these and related topics – games focusing on delivering foresight and wider understanding as part of the Operational Planning Process.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).