1.0. Introduction

Sleep is crucial for all living things especially among undergraduate students. Studies have shown that poor sleep quality contributes to the development and maintenance of depressive symptoms, and depression impairing sleep disturbances [

1,

2]. A strong association has been established between sleep quality and depression in different studies conducted among undergraduates from different institutions [

3,

4,

5]. University students are at a higher risk of developing depression and decreased sleep quality than the general population [

6,

7]. Different trends in sleep quality and depression among university students includes gender [

8,

9], age [

10], physical activity [

11], course of study/heavy academic pressure [

13], and in recent years, post COVID lockdown measures [

7,

8,

10].

Studies conducted among Chinese international undergraduate students [

11] reported that the female students had more prevalence of sleep disturbance and depressive mood changes based on their level of participation in the study. Previous studies on depressive symptoms among undergraduates at the University of Georgia also reported similar trend [

14].

However, physical inactivity can result in an increase in students' social isolation, depressive symptoms and presumably affect their level of sleep quality [

15]. Medical students have a higher prevalence of sleep disturbance and depression in comparison to nonmedical students due to academic stress [

9,

16]. Although, an international meta-analysis study observed that the prevalence of depression among pre-pandemic university students worldwide was 30.6%, direct result of the pandemic and its associated control measures, higher education students are expected to face worsened mental health challenges due to drastic deviations from their normal routines as they transition to an online learning environment [

17].

This study examined trends in sleep quality and depressive symptoms among University of Georgia students from 2020 to 2024. A cross-sectional study used secondary data from 2020, and primary data collected in 2024.

2.0. Methods

Data Collection

For this study, we used secondary data and collected primary had varying sample sizes and types of information because researchers used different protocols when collecting in Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index PSQI [

18] and becks depression inventory-II (BDIII) [

19] reports.

Secondary data were retrieved from the medical department's database, focusing on previously self-administered PSQI and Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) assessments from 2019 to 2024. We contacted the authors to obtain their raw data. And we used the year of data collection, the participant's score for each BDI-II item, the BDI-II total score, the PSQI item, PSQI global score, the year of study. and demographics (age, sex, nationality, covid symptoms,)

Primary data: for 2024 using the university mailing system and personal distribution methods, after obtaining verbal consent. The participants invited were all University of Georgia students, including both local and international students. Additional variables collected included age, gender, year of study, country of origin, and COVID-19 symptoms in the past three months. Data from these two time-points were compared.

Inclusion criteria: students with active status, able to provide informed consent, and willing to complete at least one of the PSQI or BDI-II assessments were the inclusion criterion. Archived data included only students studying at the University of Georgia, both Georgian and international.

Exclusion criteria: responses with more than two missing variables (n=28), participants aged ≤17 (n=3), and archived data students that are not enrolled in the University of Georgia or those aged ≤17(n=0).

Study Instruments

PSQI

The PSQI, a validated and widely used instrument available in many languages including English, was translated into Georgian for this study. It consists of 19 self-rated questions assessing the respondent’s sleeping patterns, the impact of sleep disturbances on daytime functioning, and the use of sleep aids. The PSQI comprises seven components, and the global score ranges from 0 to 21 [

18]. A score higher than 5 indicates poor sleep quality, while a score of 5 or lower reflects good sleep quality. This cut-off score has a sensitivity of 89.6% and specificity of 86.5% for detecting poor sleepers [

18]. The Georgian translation of the PSQI was validated among a sample of university students, demonstrating adequate internal consistency. In this study, the PSQI’s total score was computed only for respondents who provided complete and valid answers to all survey questions.

BDI-II

The BDI-II was employed to evaluate depression severity among university students. The BDI-II is a globally recognized 21-item self-report instrument that assesses depressive symptoms over the past two weeks. Each item offers four response options, ranging from 0 (no symptom) to 3 (severe symptom). The total score ranges from 0 to 63 and is interpreted as follows: 0-10 indicates normal fluctuations in mood, 11-16 suggests mild mood disturbance, 17-20 signifies borderline clinical depression, 21-30 represents moderate depression, 31-40 indicates severe depression, and scores over 40 extreme depressions [

19]. This scoring system was chosen for its specificity, sensitivity, high reliability, and enhanced concurrent and content validity, making it suitable for identifying depression among university students. The study adhered to the conventional cut-off scores to differentiate between severity levels [

20].

Data Analysis

A total sample size of both retrieved data and original consists of 1090 of PSQI responses and 387 BDI-II responses of, we compared 2 main groups, the first group who completed the questionnaire in 2020 had 534 PSQI responses and 155 BDI-II responses and the second group in 2024 had 556 PSQI responses and 210 BDI-II responses, includes other variables and we divided them as follows, age: (≤24-≥25), sex: (Male, Female), nationality: (Georgian, International), Covid status: (positive, negative), year of study: (first year, second year, third year, ≥ forth year), PSQI global score(≤5 good night sleep, ≥6 poor night sleep) BDI-II classification(≤16=low,17-30=moderate, ≥31significant)

Statistical Analysis

The SPSS software version 23 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows) was used for the data analyses. Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were used for the analysis of demographic characteristics. The total scores for both the (PSQI) and the BDI-II were computed for each respondent and presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Independent t-tests were used to measure the differences in global PSQI and BDI-II scores between the 2020 and 2024 samples. Pearson chi-square tests were employed to assess the differences between demographic variables, total sleep quality scores, and BDI-II scores.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study protocol was approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board (reference number: UGREC-01-22). The participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. No personal identifiers were collected, and all responses were anonymous. Our study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

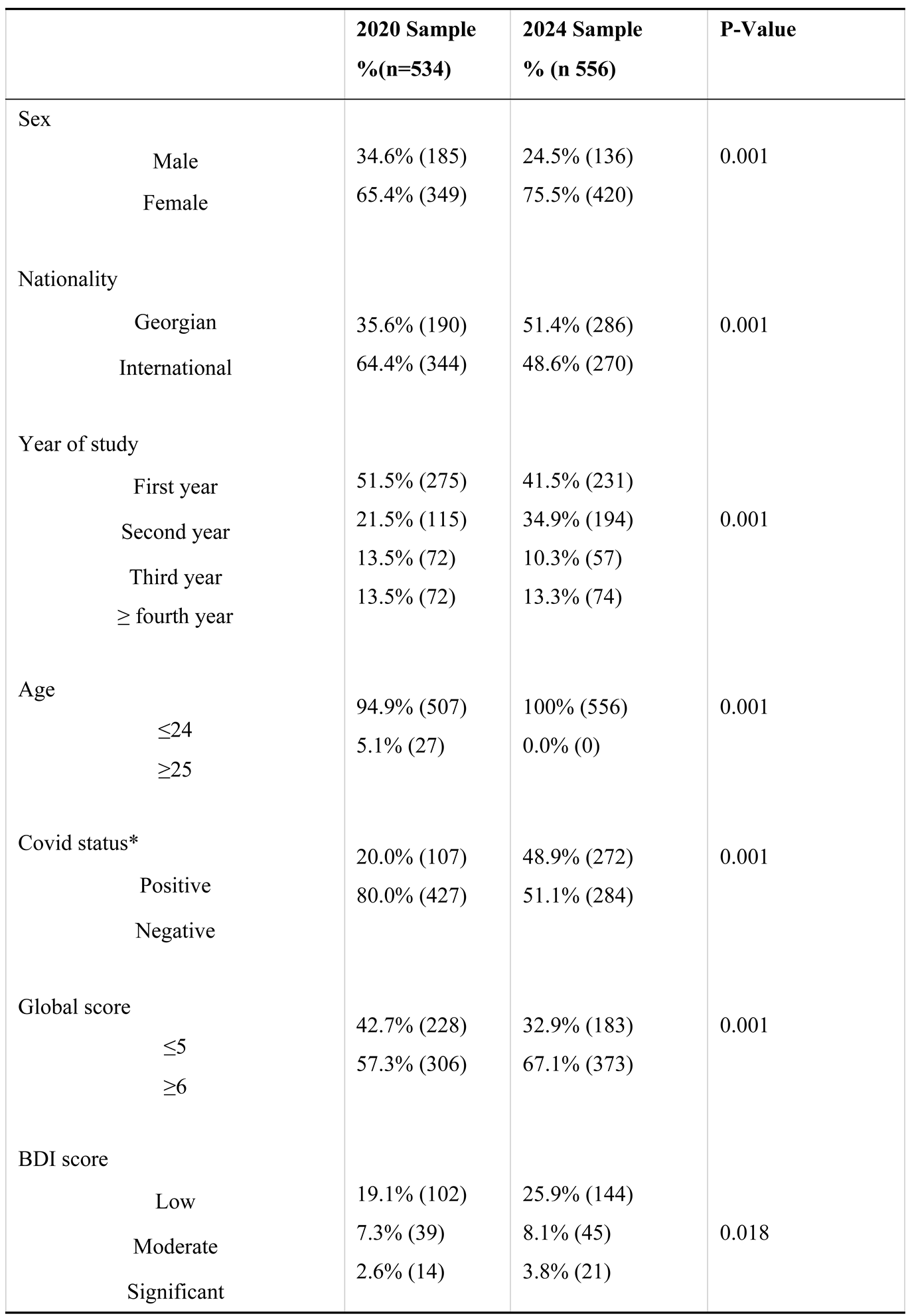

More female students participated in the study (70.6%) than male (29.4%). in 2020 34.6% men and 65.4% women, while the 2024 sample included 24.5% men and 75.5% women. The nationality had both local and international students, local 35.6% in 2020 and 51.4% in 2024, while international students were 63.4% in 2020 and 48.6% in 2024. Most students were in their first year of study (51.5%) and 13.5% in their fourth year or higher in 2020, and 41.5% in their first year and 13.3% in their fourth year or higher in 2024. Age distribution was predominantly under 24 years, with 94.9% of students aged ≤24 in 2020, and 100% of students aged ≤24 in 2024. COVID-19 positive cases varied between the two sample years, increased over time, with 20.0% positive cases in 2020, and 48.9% positive cases in 2024 (

Table 1).

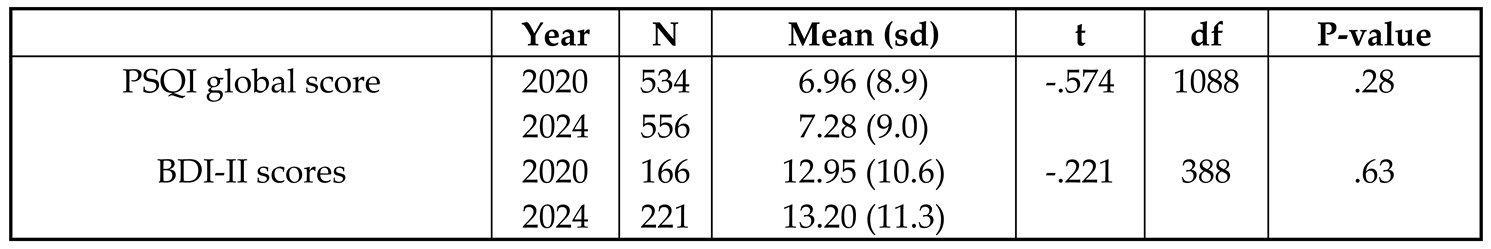

Total PSQI scores were calculated for the sample of students. Most respondents had PSQI scores greater than 5 (67.1%) in 2024 compared to (57.3%) 2020 , with a mean PSQI score of 6.96(SD=8.9) in 2020 while 7.28(SD=10.6) showed slight increase .the mean of BDI score in 2020 12.9(SD=10.6) while in 2024 increased to 13.2 (SD=11.35) (

Table 1&

Table 3).

The gender distribution showed a significant difference between female and male students (χ² (1) = 13.5, p < 0.0001). Similarly, age distribution differed significantly between students aged ≤24 and those aged ≥25 (χ² (1) = 28.8, p < 0.0001). COVID-19 status also exhibited a significant variation between the two years (χ² (1) = 100.1, p < 0.0001). The analysis of the year of study revealed significant differences across the samples (χ² (3) = 25.3, p = 0.001). Additionally, there was a significant difference in the distribution of Georgian and international students (χ² (1) = 27.8, p = 0.001).

The PSQI global scores showed a significant difference between the samples (χ² (1) = 11.0, p = 0.001). the BDI-II scores also showed a significant difference between the two samples (χ² (3) = 10.0, p = 0.018). An independent samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean scores of the global PSQI and BDI-II between 2020 and 2024. The results showed no significant differences in mean global PSQI scores t (1088) = -0.574, p = 0.28) and BDI-II scores t (385) = -0.221, p = 0.63 across the two time points (

Table 2).

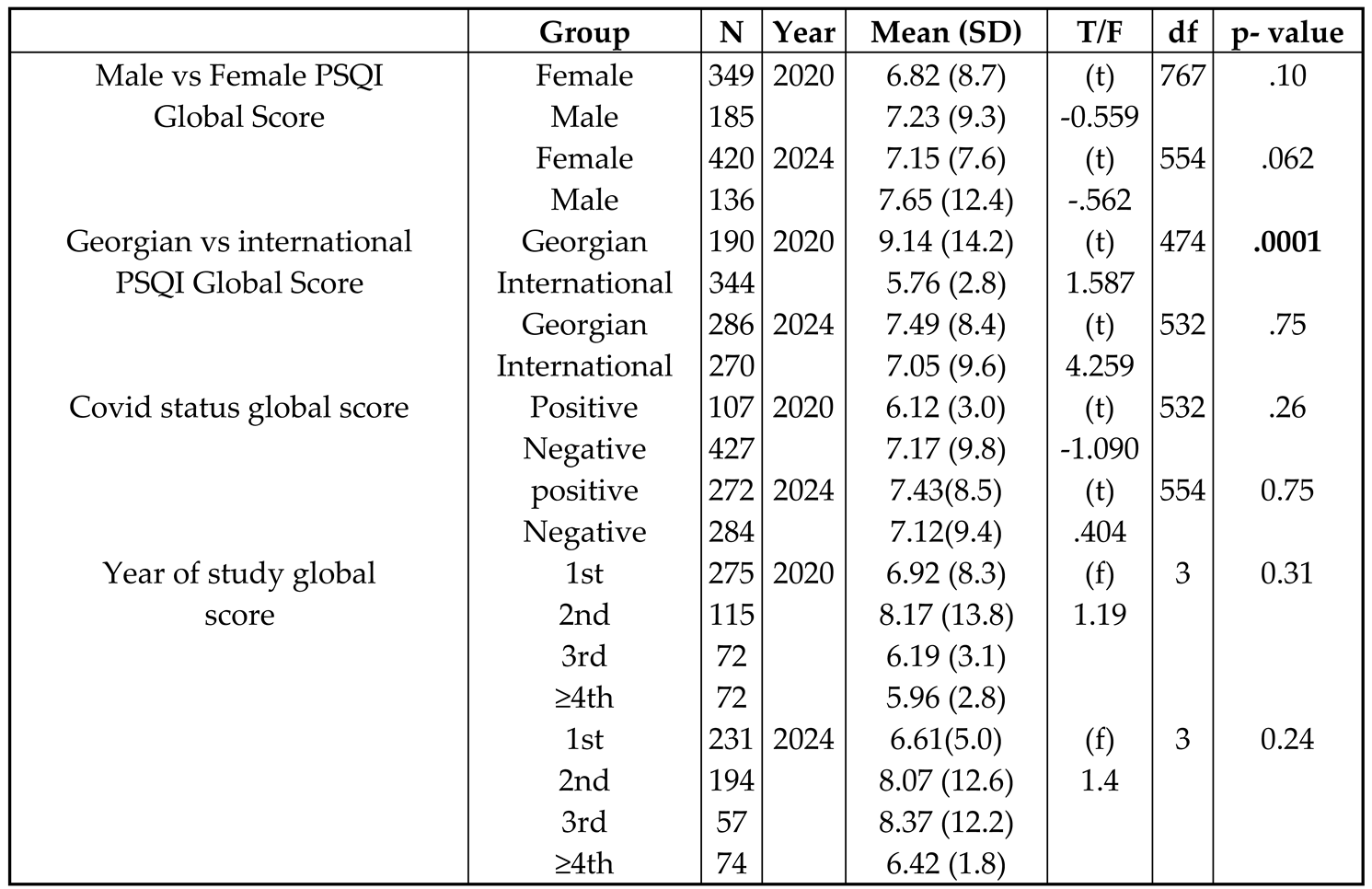

In comparing the 2020 and 2024 samples, the mean PSQI Global Scores for females were 6.82 (SD = 8.7) in 2020 and 7.23 (SD = 9.3) in 2024, while for males, the scores were 7.15 (SD = 7.6) in 2020 and 7.65 (SD = 12.4) in 2024 almost no change, respectively. Significant differences were found between Georgian and international students' PSQI scores in 2020 t (474)= 1.587, p = 0.0001), but not in 2024 t (532) = 4.2, p = 0.75). For COVID-19 status, no significant differences were observed in PSQI scores. Analysis by year of study no statistically significant differences in PSQI scores for either 2020 or 2024 (

Table 3).

Discussion

The findings of this study have shown significant insights into the trends in sleep quality and depression among university students at the University of Georgia between 57.3% in 2020 and 67.1% in 2024. Our data revealed that there was a noticeable shift in sleep quality over this period, consistent with other studies [

21], illustrating the impact of external factors such as the COVID-19 pandemic [

22,

23] and increased academic pressures on students' well-being, especially during exam periods [

24]. The analysis of PSQI scores indicated an increase in poor sleep quality among students from 2020 to 2024 This change can be attributed to various factors, including night use screen time and media use [

25], alcohol use [

26] other and lifestyle factors such as, caffeine [

27]. Specifically, the mean PSQI score in 2020 was 6.96 which increased to 7.28 in 2024 table 2. This trend suggests that sleep quality has deteriorated.

Out of the 556 students who participated in our questionnaire, the majority (70.6%) are female. A slight difference in PSQI scores between male and female students was noted in 2024. The discrepancy may be attributed to the difference in response rate between male (136) and female (420) participants. It was observed that both male and female participants experienced poor sleep. However, male participants had slightly worse sleep quality, as indicated by their higher PSQI Global Scores in both 2020 and 2024. These gender differences do not align with other studies by [

1,

5,

11]. These studies noted that females typically experience poorer sleep quality compared to males. Our findings, however, suggest that male students in our sample experienced poorer sleep quality compared to their female counterparts.

Georgian students had higher PSQI mean score compared to international students both in 2020 [

10] and 2024. However, in these two years, local (Georgian) students exhibited poorer sleep quality compared to international students, irrespective of the differences in significance observed in both years. This finding contrasts with a study conducted in China among Chinese students studying from home and abroad conducted. This study revealed that Chinese students studying abroad experienced poorer sleep compared to those studying at home [

1]. The study highlighted that student studying abroad faced additional stressors such as cultural adjustments, language barriers, and isolation, which contributed to their sleep disturbances. In contrast, our findings suggested that local Georgian students faced unique challenges during both the COVID-19 pandemic and the post-pandemic period, potentially including heightened academic pressure, socio-economic stress, and limited access to supportive resources, all of which could have negatively impacted their sleep quality.

As opposed to the big difference in PSQI mean score in 2020 based on COVID 19 status, which may be attributed to the small sample size of COVID19 positive students, the PSQI mean score in 2024 shows only a minor difference. The significant difference in 2020 may be due to the initial outbreak of COVID-19, which led to heightened stress and depressive symptoms among medical students as they had to go through the uncertainties and disruptions caused by the pandemic. By 2024, the effects of COVID-19 may have stabilized, resulting in a smaller difference in PSQI mean scores. Similar findings were reported in a study by Chen et al. [

9], which also highlighted the significant impact of the pandemic on students' mental health causing depressive symptoms and poor sleep quality during the initial outbreak period.

Regarding the year of study, most participants were first-year students in both 2020 and 2024. However, it was the second-year students who experienced the worst sleep quality in both the COVID-19 period of 2020 and the post-COVID period of 2024. Contrary to the findings of Yin et al. [

8], which indicated that senior students had a higher likelihood of experiencing poor sleep compared to those in lower years, our study found that senior students had better sleep compared to those in their 2nd and 3rd years. This may suggest that the stressors and challenges impacting sleep may vary significantly across different educational contexts and time periods. The poorer sleep quality among second-year students in our study could be attributed to the unique pressures they face, such as adjusting to more demanding coursework and greater academic expectations, which were prevalent in both 2020 and 2024.

Conclusion

Our findings align with the observations made by Johansson et al. (2024), who reported similar trends in mental health challenges among university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, Chen et al 2022 highlighted the impact of changes in environment on emotions and sleep quality, a factor that our study supports given the significant correlations found between and both PSQI and BDI-II scores. These findings have important implications for university policies and student support services. Universities should create more support systems and prioritize mental health resources. For future research, it is essential to explore the trends on students' mental health and to evaluate the effectiveness of various interventions aimed at improving sleep quality and reducing depression among university students.

Funding

This study was not funded.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participating students and the university for their cooperation.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study protocol was approved by the University of Georgia Institutional Review Board. All participants provided informed consent.

References

- Bi, C., Lin, H., Zhang, J., & Zhao, Z. (2022). Association between sleep quality and depression symptoms in Chinese college students during the COVID-19 lockdown period.Children, 9(8), 1237. [CrossRef]

- Alqurashi, Y. D., Al Qattan, A. H., Al Abbas, H. E., Alghamdi, M. A., Alhamad, A. A., Al-Dalooj, H. A., Yar, T., Al khathlan, N. A., Alqarni, A. S., & Salem, A. M. (2022). Association of sleep duration and quality with depression among university students and faculty.Acta Biomed, 93(5), e2022245. [CrossRef]

- Alam, S., Kalra, S., Mohapatra, S. C., Rai, R., & Raghav, D. (2023). Frequency and associated factors of physical activity and sleep with depression in college-going students. JDHUS.

- The 10th Congress of Asian Sleep Research Society and Asian Forum of Chronobiology, 2023. (2023). Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 21(4), 477–502. [CrossRef]

- Salih, A. M. M., Madallah, Z. T., Ibrahim, R. H., Alseadn, M. S. H., & Almushhadany, O. I. (2023). Exploring the relationship between insomnia and depression: A cross-sectional prospective study. Annals of medicine and surgery.

- Johansson, F., Côté, P., Onell, C., Källberg, H., Sundberg, T., Edlund, K., & Skillgate, E. (2023). Strengths of associations between depressive symptoms and loneliness, perfectionistic concerns, risky alcohol use, and physical activity across levels of sleep quality in Swedish university students: A cross-sectional study.Journal of Sleep Research. [CrossRef]

- Gogichadze, M., Mgbedo, N., Landia, N., & Odzelashvili, I. (2023). Sleep quality, perceived academic stress and mental health among international students at the University of Georgia during COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 455, 122242. [CrossRef]

- Yin, F., Chen, C., Song, S., Chen, Z., Jiao, Z., Yan, Z., Yin, G., & Feng, Z. (2022). Factors affecting university students’ sleep quality during the normalisation of COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control in China: A cross-sectional study.Sustainability, 14(17), 10646. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Tuersun, Y., Yang, J., Xiong, M., Wang, Y., Rao, X., & Jiang, S. (2022). Association of depression symptoms and sleep quality with state-trait anxiety in medical university students in Anhui Province, China: A mediation analysis.BMC Medical Education, 22, 627. [CrossRef]

- Mgbedo, N. E., Alighanbari, F., Radmehr, S., George, A. M., & Gogichadze, M. (2022a). Covid-19 pandemic’s impact on the student’s sleep patterns at the University of Georgia. Sleep Medicine, 100. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. (2022). The interaction between sleep quality and gender on depression level among Chinese international students. InThe International Conference on Interdisciplinary Humanities and Communication Studies. University College London. [CrossRef]

- Mgbedo, Nnaemeka Emmanuel, Landia, N., Odzelashvili, I., Alighanbari, F., & Gogichadze, M. (2023). Influence of Covid 19 Conditions on Sleep Alterations of Georgian and Foreign Students at the University of Georgia- A Cross Sectional Study. Qual Prim Care. 31.010.

- Jiang, X. -l., Zheng, X. -y., Yang, J., Ye, C. -p., Chen, Y. -y., Zhang, Z. -g., & Xiao, Z. -j. (2015). A systematic review of studies on the prevalence of Insomnia in university students. Public Health, 129(12), 1579–1584. [CrossRef]

- Mgbedo, E.N. During The Covid-19 Pandemic Evaluation of Stress and Depression Among University of Georgia Students: A Pilot Cross-Sectional Study. In Proceedings of 6th Eastern-European Conference of Mental Health & 3rd International Public Mental Health Conference, Zagreb, Croatia (14th October 2022).

- Bulguroğlu, H. I., Bulguroğlu, M., Gevrek Aslan, C., Zorlu, S., Dinçer, S., & Kendal, K. (2023). Investigation of the effects of physical activity level on posture, depression, and sleep quality in university students.International Journal of Disability, Sports, and Health Sciences, 6(2), 119-128. [CrossRef]

- Carpi, M., & Vestri, A. (2023). The mediating role of sleep quality in the relationship between negative emotional states and health-related quality of life among Italian medical students.International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(1), 26. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J., Zhou, F., Hou, W., Silver, Z., Wong, C. Y., Chang, O., Drakos, A., Zuo, Q. K., & Huang, E. (2021). The prevalence of depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance in higher education students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis.Psychiatry Research, 301, 113863. [CrossRef]

- Buysse, D. J., Reynolds, C. F., Monk, T. H., Berman, S. R., & Kupfer, D. J. (1989). The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Research, 28(2), 193–213. [CrossRef]

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Brown, G. (2011). Beck Depression Inventory–II. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-P., & Gorenstein, C. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory-II: A comprehensive review. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 35(4), 416–431. [CrossRef]

- Bourmistrova, N. W., Solomon, T., Braude, P., Strawbridge, R., & Carter, B. (2022). Long-term effects of COVID-19 on mental health: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 299, 118–125. [CrossRef]

- Zawilska, J. B., & Kuczyńska, K. (2022). Psychiatric and neurological complications of long COVID. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 156, 349–360. [CrossRef]

- Alkodaymi, M. S., Omrani, O. A., Fawzy, N. A., Shaar, B. A., Almamlouk, R., Riaz, M., Obeidat, M., Obeidat, Y., Gerberi, D., Taha, R. M., Kashour, Z., Kashour, T., Berbari, E. F., Alkattan, K., & Tleyjeh, I. M. (2022). Prevalence of post-acute COVID-19 syndrome symptoms at different follow-up periods: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 28(5), 657–666. [CrossRef]

- Suardiaz-Muro, M., Ortega-Moreno, M., Morante-Ruiz, M., Monroy, M., Ruiz, M. A., Martín-Plasencia, P., & Vela-Bueno, A. (2023). Sleep quality and sleep deprivation: Relationship with academic performance in university students during examination period. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 21(3), 377–383. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X., Tao, S., Zhang, Y., Zhang, S., & Tao, F. (2015). Low Physical Activity and High Screen Time Can Increase the Risks of Mental Health Problems and Poor Sleep Quality among Chinese College Students. PLoS ONE, 10(3), e0119607. [CrossRef]

- Zunhammer, M., Eichhammer, P., & Busch, V. (2014). Sleep quality during exam stress: The role of alcohol, caffeine and Nicotine. PLoS ONE, 9(10). [CrossRef]

- Lohsoonthorn, V., Khidir, H., Casillas, G., Lertmaharit, S., Tadesse, M. G., Pensuksan, W. C., Rattananupong, T., Gelaye, B., & Williams, M. A. (2013). Sleep quality and sleep patterns in relation to consumption of energy drinks, caffeinated beverages, and other stimulants among Thai college students. Sleep and Breathing, 17(3), 1017–1028. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).