1. Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a systemic autoimmune disease of unknown etiology. RA is the most common chronic disorder, with a global prevalence incidence of 0.5-1% [

1]. Citrullination is a post-translation modification (PMT) process related to human physiology and some pathological diseases. In inflammatory diseases such as RA, MS, and PsA, citrullinated peptides (CPs) have been found to trigger antibodies against such modified proteins [

2]. Autoantibody measures have been a constant companion for physicians managing RA patients, and their significance has grown over the past few decades. Autoantibody investigations include the measurement of rheumatoid factor (RF) and anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs). ACPAs and RF improve diagnostic accuracy and are included in the 2010 ACR/EULAR criteria [

3,

4]. RF is commonly used as a diagnostic marker of RA, whereas anti-ACPAs, including anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP) and anti-mutated citrullinated vimentin (anti-MCV), are being used as specific prognostic and diagnostic biomarkers for RA. Both anti-CCP and anti-MCV may exist in patients' sera years before the appearance of clinical symptoms; thus, they can predict the early progression of RA [

4,

5]. However, RA could be classified as seropositive RA (SPRA) or seronegative RA (SNRA). SPRA refers to the presence of IgM-RF and/or ACPAs, whereas SNRA refers to the absence of these autoantibodies in confirmed RA. Based on clinical and laboratory evidence, seropositivity occurs in 60-80% of patients with confirmed RA [

6].

Despite the exact cause of RA is still unknown, a bulk of evidence indicates that many factors might increase the risk of RA, including age, gender, genetic, environmental, and metabolic factors. The combination of genetic and environmental factors is strongly associated with RA. The early diagnosis of RA is important in the treatment and prevention of worse stages [

7]. Many epidemiologic studies indicate sex-related factors in RA risk, as two-thirds of RA patients are female. Therefore, it has long been thought that there are female-specific characteristics that increase the risk of RA [

8]. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis investigated the association between gender type and serostatus, i.e., seropositive and seronegative. This meta-analysis found that men with RA are more likely to have seropositive RA than women. The results indicated that RF-positivity in males was 16% higher than in females. Similarly, the analysis of ACPA seropositivity showed that males who were ACPA-positive were 12% higher than females [

9]. Many studies have elucidated that hormonal replacement therapy (HRT) and the use of oral contraceptives (OCs) for ≥7 years were effective against ACPA and RF development [

10,

11].

The frequency of RF and ACPA positivity was variable among different age groups. Some reports revealed that seropositivity is more frequent in patients aged above 40 and up to 60 years, while it is less prevalent in other age groups, i.e., <40 and >60 years [

12,

13]. Considering disease duration, it has been found that there is no significant change in autoantibody existence in patients with early RA (<1 year) and established RA (>2 years). A slight rise has been reported in RF, anti-CCP, and anti-MCV [

4]. However, another stydy found that anti-CCP and IgM-RF increased significantly after 5 years of duration [

14]. This was supported by further studies that have found that ant-CCP frequency and level exacerbate in the early onset of RA (≤1 year) and then decline decrementally within 3-5 years. Afterward, anti-CCP increased significantly after 5 years of duration [

15,

16]. Extensive epidemiologic studies have demonstrated that the RA risk for smokers is two times higher than that of non-smokers, notably in male smoker RA patients [

17,

18]. Even in the absence of RA, smoking has long been linked to a positive RF [

19,

20]. Many studies have linked the presence of ACPA in smokers to the fact that smoking induces the citrullination process during lung inflammation. It has been found that there is a considerable correlation between smoking and anti-CCP concentration, whereas RF levels were comparable between smoker and non-smoker RA patients [

21,

22,

23,

24].

RA is highly heritable and, unfortunately, tends to run in families. According to various studies, 50–60 percent of RA cases are thought to be heritable [

25,

26]. Assessment of family history in autoimmune diseases may be considered before the identification of genetic factors [

27,

28]. The human leukocyte antigen (HLA) has essential roles in antigen presentation and immune response in RA. HLA-DRB1 carrying shared epitopes (SE) is a class II-HLA, and it is well established to be the strongest genetic risk factor for developing RA [

29]. Recent studies have clarified the high expression of HLA-DRB1 SE on the immunocytes of RA patients. The HLA-DRB SE can bind and present the citrullinated protein and trigger the autoimmunity response in RA [

30,

31]. Considering the serostatus, early familiar and genetic studies found that family aggregation was higher in seropositive RA cases than in seronegative cases [

32,

33].

Interestingly, it has been verified that RA patients had higher levels of extracellular vesicles (Evs) than healthy individuals [

34]. Furthermore, people with RA have been reported to have distinct exosome cargo, which may help with diagnosis [

35]. Exosomes are the smallest and most well-studied class of Evs, with an average diameter of 30-150 nm and density of 1.13–1.19 g/ml; they have a spherical cup-like shape in EM images [

36,

37]. Exosome cargo includes proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, small molecules, and receptors. These nanoparticles have many critical roles in biological systems' physiology, pathology, and therapy [

38]. Exosomes encompass many proteins in their cargo, with the proteome of a typical exosome containing approximately 4,400 proteins [

39]. The most common proteins in exosomes are ESCRT proteins (Alix and tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101)), heat shock proteins (HSP70 and HSP90), and tetraspanin (CD9, CD63, and CD81). Distinctly, these exosome-enriched proteins are highly utilized as specific markers for exosomes [

40]. The high stability of exosomes in the extracellular space enables them to carry their cargo far away to interact with distant cells [

41].

The proteomic and immunological studies of immune cell-derived exosomes obtained from different body fluids revealed the significant role of these nanovesicles in the regulation and modulation of immune responses, including both immune suppression and immune stimulation [

42]. Serum exosomes can transfer several proteins involved in RA pathogenesis and might be predictors of therapeutic responses. Serum exosomes exhibit antigen-presenting functions as they can express HLA, especially HLA-DRB1 SE, which has a great affinity to citrullinated proteins [

43]. A recent study has shown that B cells produce a high level of HLA-bearing exosomes [

44]. Furthermore, proteomics of RA serum exosomes showed that exosomes could present the citrullinated peptides to effector CD8+ cells to release TNF-α and IFN-γ [

45]. Citrullinated fibrinogen (cFBG) has been identified as a major autoantigen for ACPAs that play a role in RA pathogenesis. The increased levels of cFBG have been detected in the serum and synovium of RA patients and have been linked to joint damage and RA severity. [

46,

47,

48]. Analysis of exosomes derived from inflamed synovium led to the detection of cFBG on the exosome surface, which may trigger the production of ACPAs [

49]. In our current work, we aim to explore the presence of cFBG in serum-derived exosomes. However, as far as we know, no studies have investigated cFBG in exosomes extracted from the serum of RA patients.

4. Discussion

This study investigated 116 RA patients, with an 8:1 female-to-male ratio. In Saudi Arabia, there is no adequate data available about the exact prevalence of RA in the Saudi population. According to several past studies, the prevalence of the disease among the Saudi population is about 0.1−0.22%, with three to four times higher rates in women than men, which reflects the high risk of worsening the condition [

50]. However, recent reports suggest that the incidence of RA is increasing, and the number of RA patients is expected to stand at around 250,000 cases in the near term, or about 1.2% of the Saudi population. [

51,

52]. For all participants, the average duration of RA is 8.4±6 years, while for 66% of the population, the average disease duration is more than 5 years. The mean age for RA patients in this study is 51.3±11.5 years, with 54% of females and 67% of males being above 50 years of age. This is in line with most data, which suggests that RA development occurs in those over the age of 50 [

13,

53,

54].

Our reported female/male ratio is significantly higher than that estimated either globally or within Saudi Arabia, and we thought that was a limitation due to the small number of male patients (12), which represents 10% of the enrolled patients. In Saudi Arabia, many studies on RA patients have been done in the last decade. A study conducted by Almoallim et al. showed that the female-to-male ratio in the cohort of 433 RA patients was 3:1, with a mean age of 49±11 years [

55].

A recent study by [

56] included 210 patients with a mean age of 46±11 and reported a prevalence of females with a ratio of about 4:1. Interestingly, a study conducted by Aseel et al. demonstrated a female-to-male ratio of 8:1 in their study, which included 438 RA patients, which is similar to our findings [

57]. However, some population-based studies have reported a higher incidence of RA in females, with a ratio as high as 9:1 [

58,

59].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic disease that results from the interaction of multiple genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors. ACPAs are produced as an autoimmune response for abnormal citrullination reactions. However, ACPAs are specific and predictive biomarkers for RA, and they can be detected in patients' sera up to 10 years before the clinical RA onset. But in fact, many RA patients might lack these antibodies. Therefore, RA diagnosis can be classified into seronegative RA (SPRA) and seropositive RA (SNRA) [

60].

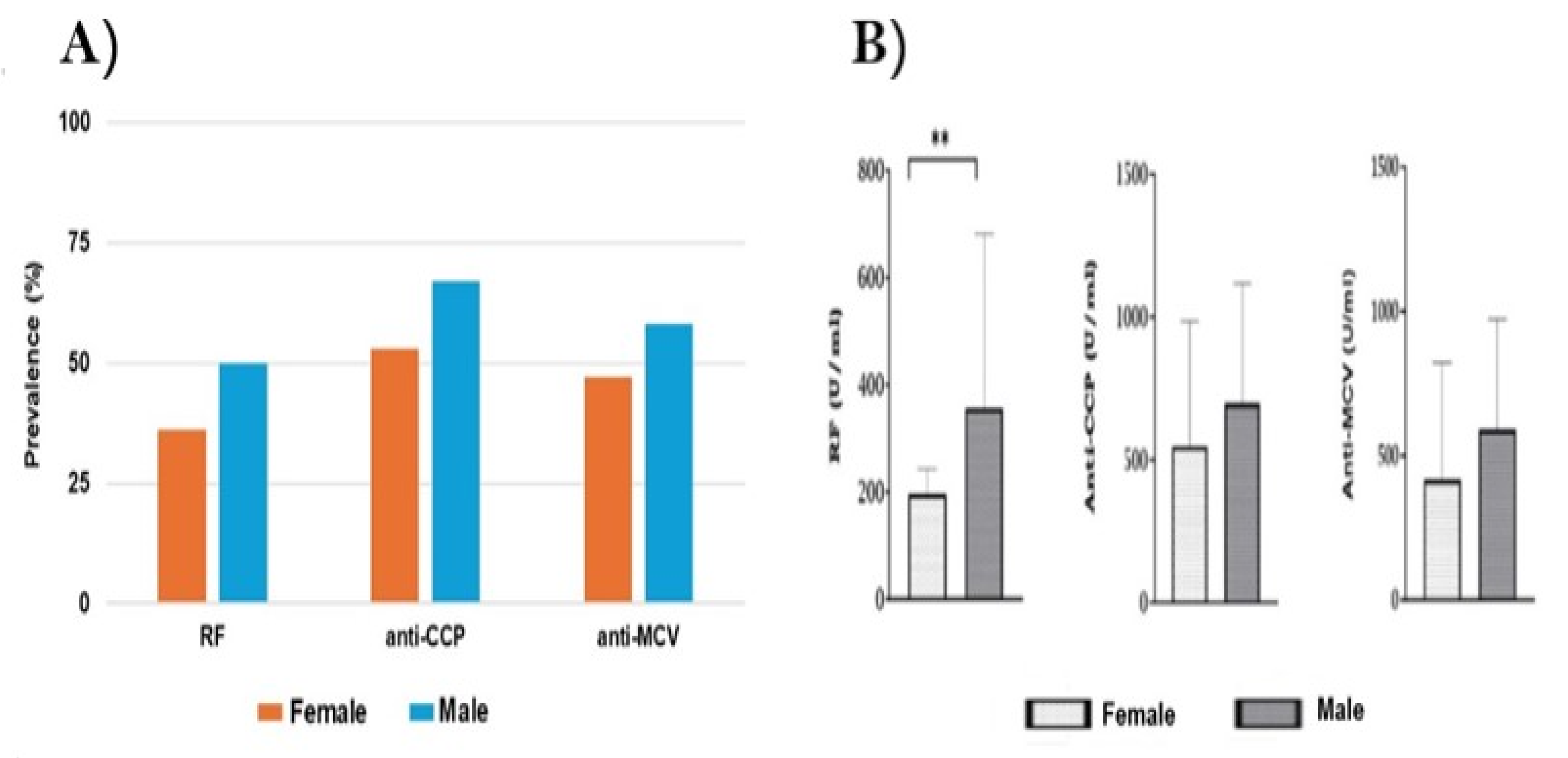

The association between RA-related autoantibodies and factors such as gender, age, disease duration, and smoking status has been investigated by many previous studies. The influence of age and gender on the development of RA has been described by several global studies [

13,

61,

62]. In the current study, 71 out of 116 patients (61%) were SPRA, and the seropositivity percentages in men were higher than those in women. However, estimations of seropositivity among RA patients have reported inconsistent percentages across a retrospective study [

63] and a comparative observational study [

64]. Our data showed that about 75% of males were SPRA, while 60% of females were SPRA. Furthermore, the titers for anti-CCP and anti-MCV were higher in males than in females without significant difference (P<0.05). These findings are consistent with the recent systematic review and meta-analysis study in 2022, which searched databases of eighty-four studies, including 141,381 RA patients, and found that seropositivity is more associated with males than females [

9]. However, our results differ from those of a recent cross-sectional study that found females represented 76% of the SPRA patients (P<0.001) [

65].

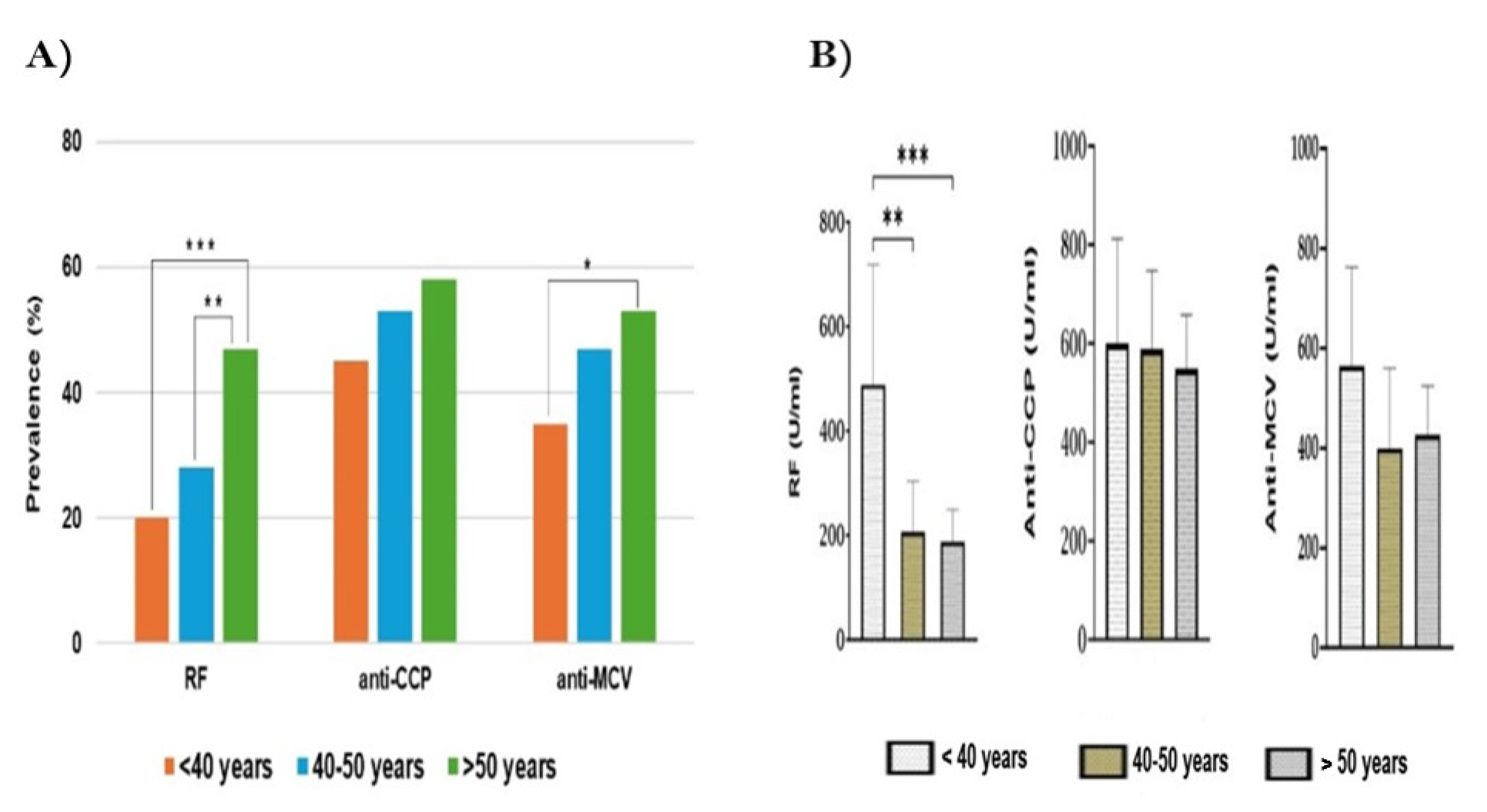

Despite the occurrence of ACPA-positive patients in our work increasing gradually with patients' age, there was no significant association for anti-CCP prevalence with age. For anti-MCV, we found it was significantly frequent in patients above 50 years of age. However, the antibody levels across age groups were almost similar or slightly decreased for both ACPAs (P<0.05). This is supported by a previous study that found a non-significant decrease of ant-CCP levels in older RA patients [

66]. Findings of our study showed that SPRA patients are older (52.1 ± 11.2 years) than SNRA patients (50.2 ± 11.9), without significant differences (P=0.39). There are some parallels and some differences between the findings of the literature and ours. Our findings are in line with previous studies that demonstrated that the prevalence of ACPA-positive RA was more frequent at older age, above 50 years [

67] and 40 years [

66]. Conversely, older age has been found to be strongly associated with SNRA than SPRA (54 ± 11 years vs. 43 ± 14 years; P< 0.001) [

65]. Furthermore, a multicohort study conducted by Boeters et al. showed that the ACPA-negative RA was more associated with older age than ACPA-positive [

68].

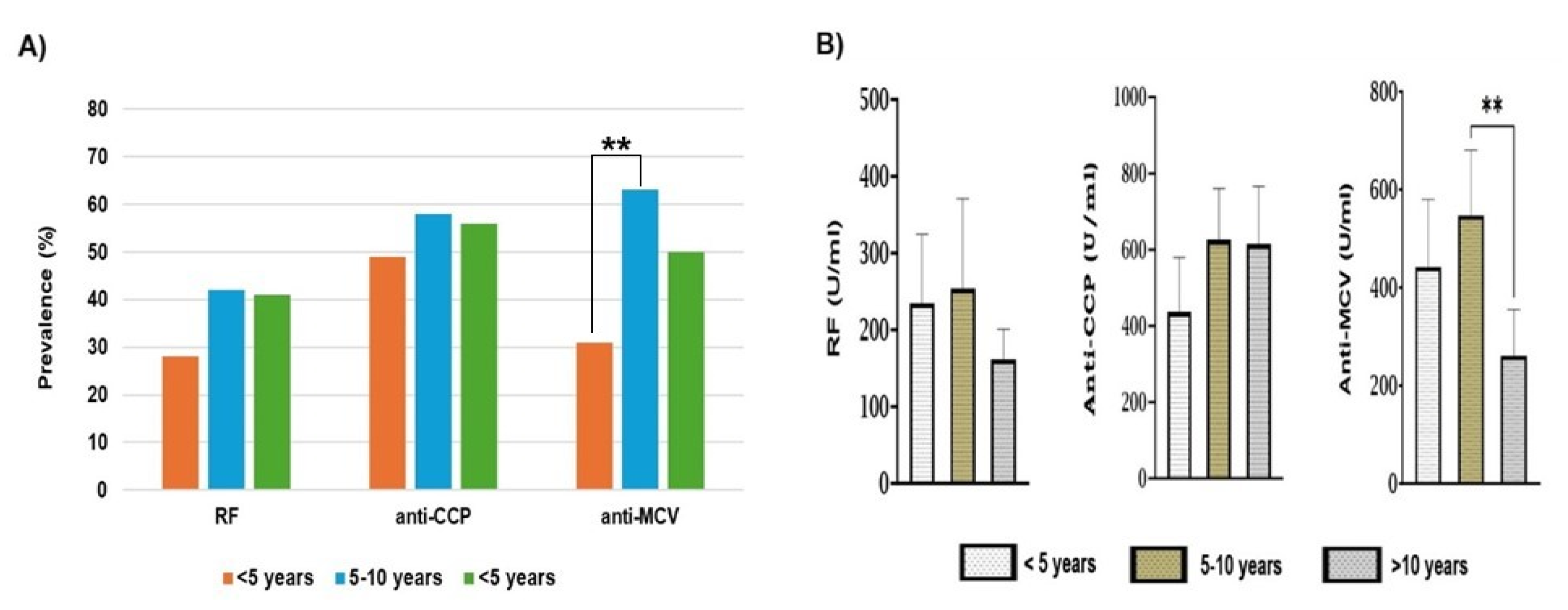

Our current work also highlights the contribution of RA duration to ACPAs. The period of 5-10 years duration reflects the highest incidences and levels for both anti-CCP and anti-MCV. But despite that, we didn’t find a significant association between positive anti-CCP and RA duration, either for prevalence or for antibody levels. A recent observational study showed that the higher incidence of ACPA-positive antibodies was associated with RA duration <10 years, followed by 5-10 years and less <5 years, respectively [

69]. A previous cross-sectional study has shown that the positive anti-CCP was more prevalent in patients with RA duration >10 years (79%) than those with duration less than 10 years (62%). This study also revealed that anti-CCP levels were comparable between the two periods of duration [

70]. We found that the prevalence of anti-MCV antibodies increased after 5 years of duration, whereas the high levels were associated with the period of 5-10 years of duration. The assessment of anti-MCV by Poulsom and Charles. Showed that the prevalence of ant-MCV was higher in short RA duration than in long duration [

71].

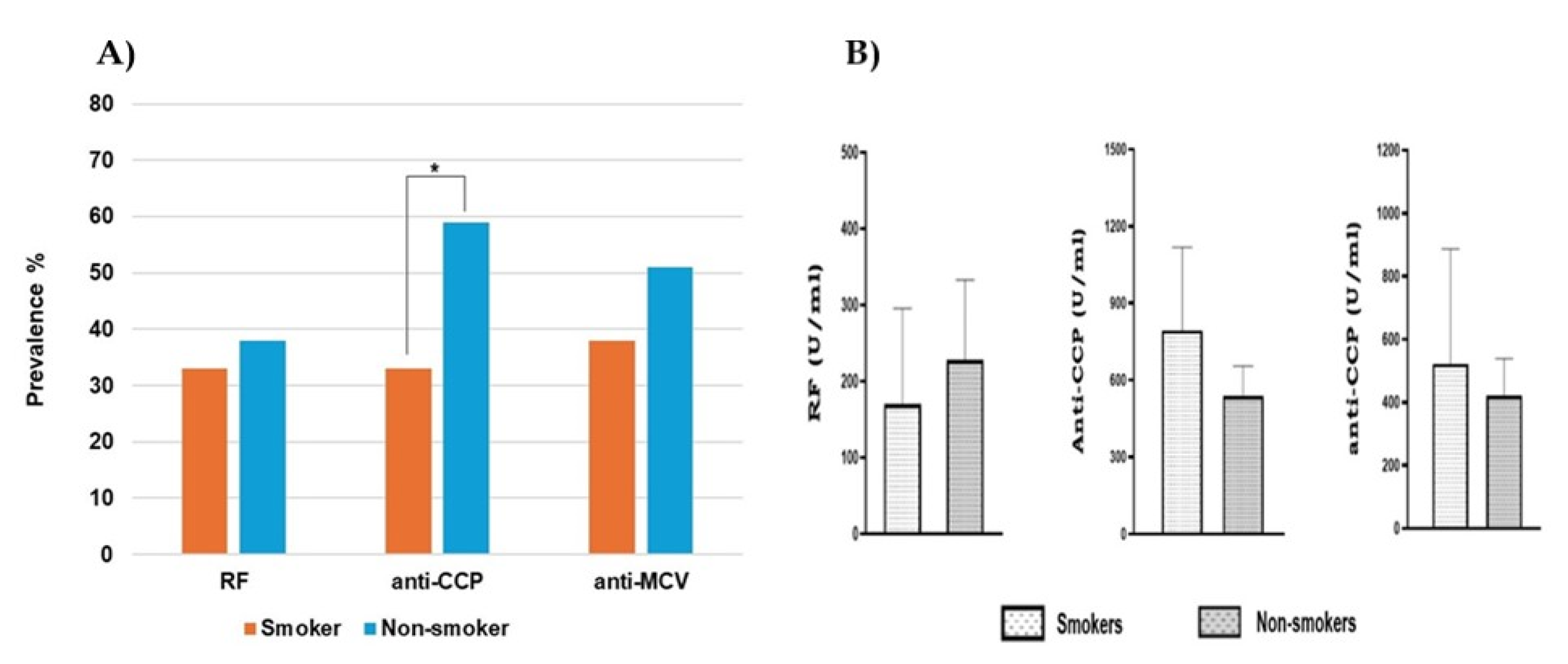

Smoking is considered a known risk factor for rheumatoid arthritis development [

72]. A case-control Myeira study by Abqariyah et al. confirmed the association between smoking and ACPA-positive (64%) in the Malaysian RA population [

73]. The current study doesn’t find a relationship between smoking and the ACPAs incidence. On the contrary, seropositivity, whether for anti-CCP or anti-MCV, was more frequent in non-smokers than smokers. Our estimations revealed that smoking is responsible for less than 40% of ACPA-positive RA in smokers compared to more than 50% in non-smokers. This is in line with data from the Swedish Epidemiological Investigation of Rheumatoid Arthritis (EIRA) that showed that smoking is responsible for 35% of ACPA-positive RA [

74]. In this experiment, smoker RA patients showed a non-significant increase in ACPA titers. However, a previous cross-sectional analysis demonstrated a significant association between smoking and the high titers of ACPA [

75].

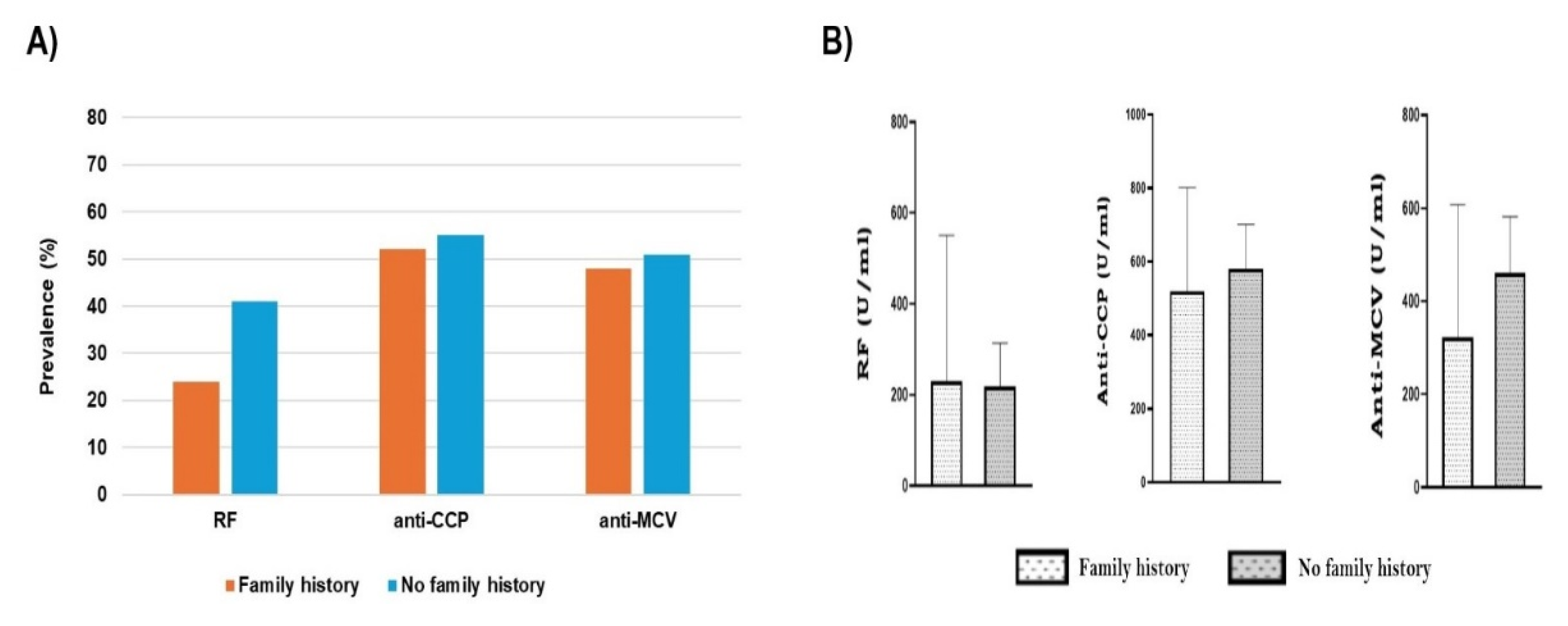

Our correlation between family history and seropositivity showed no significant association. We found that patients with no family history have a similar tendency to seropositivity as those with positive family history, even for prevalence or concentration. For instance, Diane et al. suggested that the heritability of ACPA-positive and ACPA-negative is comparable (65%) [

76]. Nevertheless, a heritability of around 50% for ACPA-positive RA and approximately 20% for ACPA-negative RA was shown to be compatible with familial hazards in register-based nested case-control research conducted in the Swedish population [

77]. The titers of anti-CCP and anti-MCV for RA patients in our work show no significant differences between those with family history and without. This is not in accordance with the findings of Kim et al., who found that the high levels of anti-CCP and anti-MCV were correlated with the presence of family history [

78].

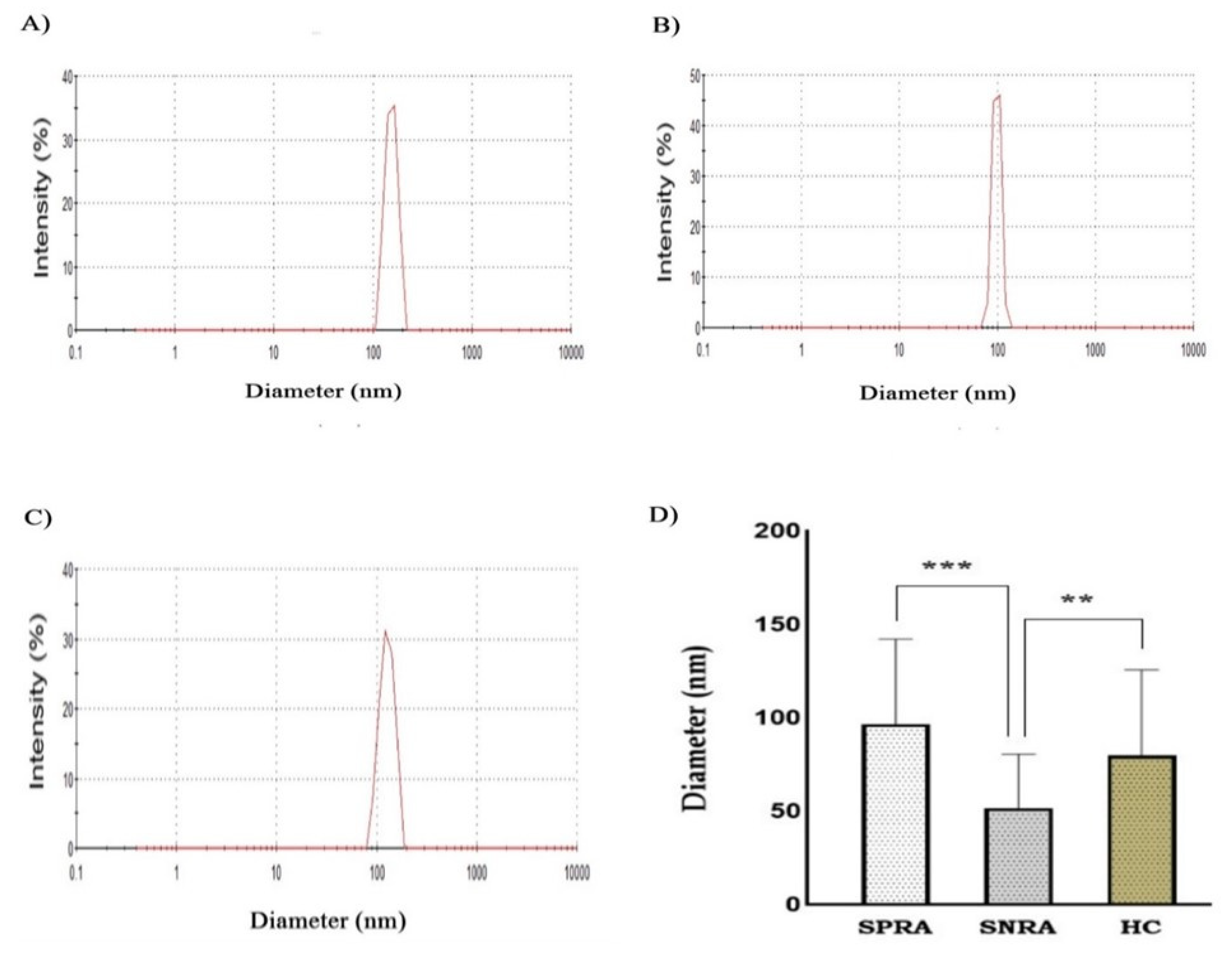

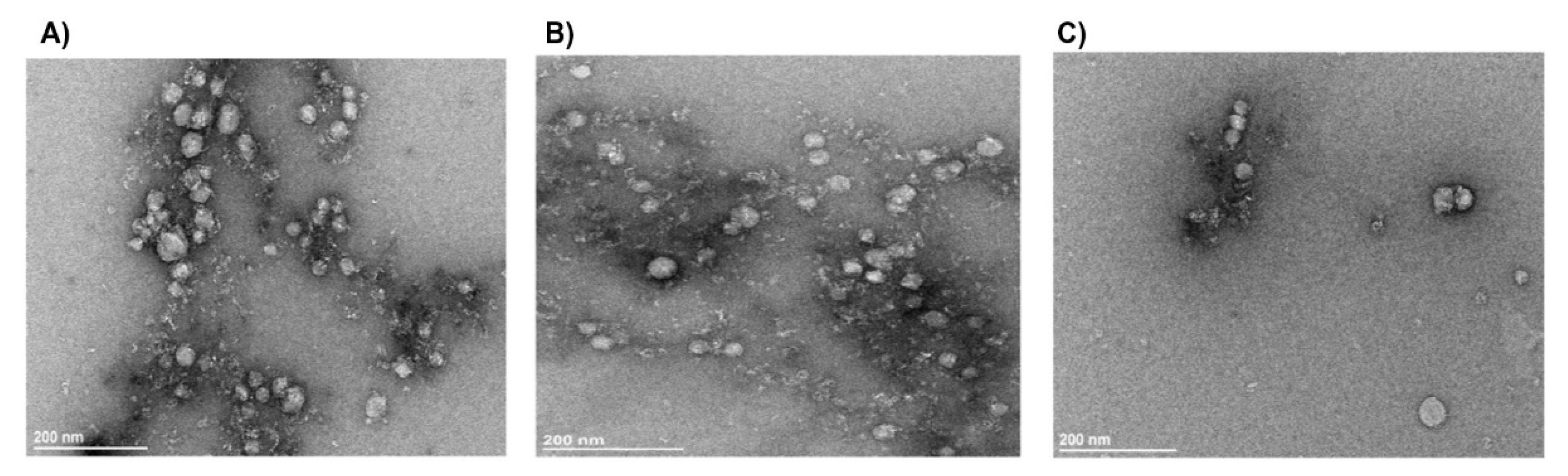

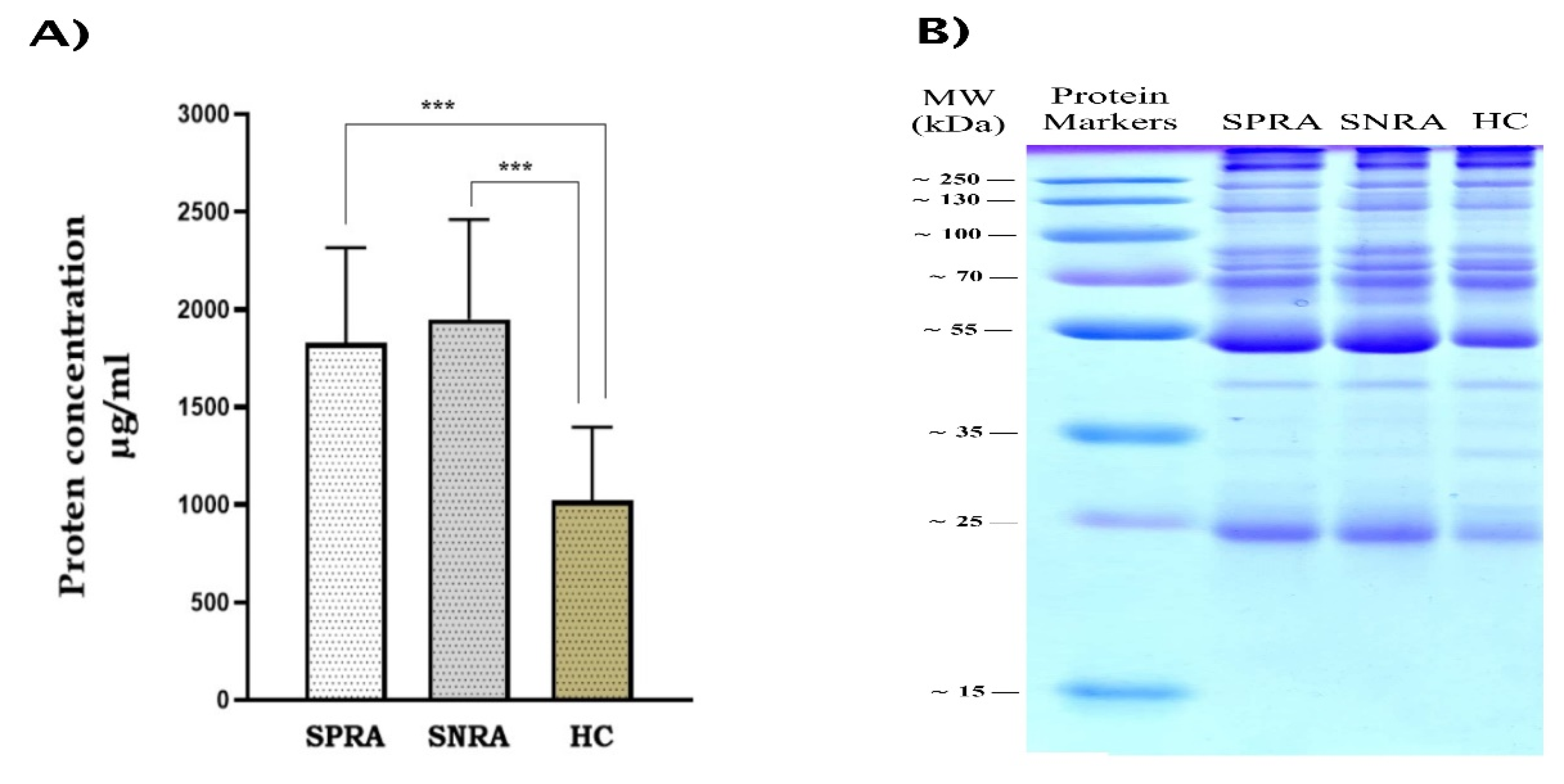

Exosomes are the smallest and most extensively researched type of Evs that participate in various biological processes and disorders. In current work, serum-derived exosome preparations of RA patients and HC were validated for morphology and protein content. Negative staining TEM is the most popular technique for visualizing exosomes [

79,

80,

81]. Using TEM, we verified that all preparations had the typically described morphology of exosomes and were within the expected size range (30-150 nm) [

82,

83,

84]. However, DLS measurements showed that SNRA-exosomes were smaller than SPRA-exosomes (P<0.001) and HC-exosomes (P=0.004). Furthermore, the exosome fraction from SPRA samples showed significant heterogeneity when compared to exosomes from SNRA and HC samples. Exosomes are known to have a very diverse population, and it is challenging to isolate exosomes because of their heterogeneity in size, composition, and function [

85,

86].

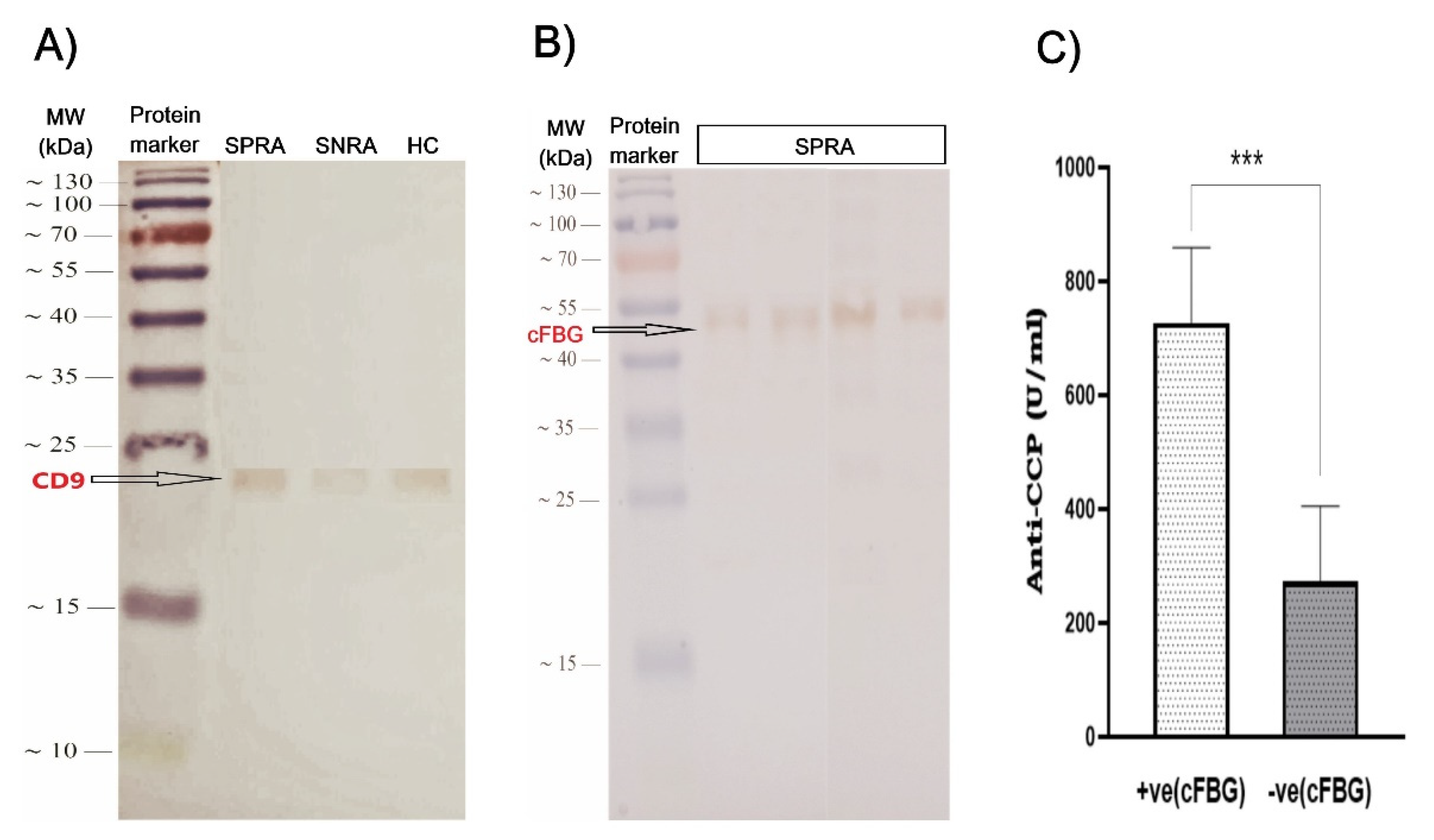

Western blot (WB) analysis is another method of exosome confirmation that looks at preparation purity and the presence of exosome markers. Tetraspanins (CD9, CD63, and CD81) are among the most widely used exosome markers; nevertheless, these proteins have also been found to be expressed positively in other EV types [

87]. These proteins have been discovered to be highly enriched in EVs as opposed to originating cells [

88]. CD9 is a 25-kDa membranous protein that can be detected by WB. Yue-Ting et al. found that exosomes have an equivalent or even higher level of CD9 than the source cells [

89]. In this experiment, all exosome samples derived from patients and controls expressed clear CD9 bands with variable intensity. We found that the intensity of CD9 bands in HC samples is not as strong as they are in patient samples.

Antibody-based techniques like ELISA, immunohistochemistry, and western blotting are widely used to detect citrullination with high sensitivity and specificity [

90]. But these techniques can't produce a large-scale analysis and reliable localization of citrullinated sites as mass spectrometry (MS) analysis. However, citrullination profiling remains a significant difficulty for mass MS-based approaches, despite its increasing effectiveness in many post-tanslation modification PTM-related investigations [

91]. In the current study, we used an anti-CCP commercial kit for the serological investigation of ACPAs, which is an ELISA-based immunoassay. The anti-CCP test was generated by screening peptide libraries containing millions of cyclic peptides to produce highly purified synthetic peptides that serve as antigens [

92]. However, some ELISA assays designated for testing anti-CCP don't specify the target antigen. Few studies have used anti-CCP assays that specified the type of citrullinated protein, such as collagen [

93], filaggrin [

94], and fibrinogen [

95].

Fibrinogen and its modified (citrullinated) form have been verified to be the most favored autoantigens for ACPAs in RA patients. Citrullinated fibrinogen (cFBG) epitopes play a role in triggering the autoimmune response in RA patients and contribute to synovitis and bone destruction [

47,

96]. With regards to Evs, research on exosomes' role in RA is still in its early stages; a small number of studies have shown that RA patients have aberrant exosome expression [

97]. It has been suggested that exosomes may contribute to joint inflammation in RA patients because they can transport autoantigens and mediators between distant cells [

98].

Recent proteomic studies were performed on exosomes extracted from plasma and serum of RA patients; these studies demonstrated distinct protein profiles in the purified exosomes, but no citrullinated proteins were identified [

45,

99]. Despite the difficulty in identifying citrullinated proteins in exosomes, a previous study compared the proteomic content of exosomes extracted from synovial fluid of RA and osteoarthritis (OA) patients. Skriner et al. were able to detect the citrullinated forms of fibrinogen, including fibrin alpha-chain, fibrin beta-chain, fibrinogen beta-chain precursor, and fibrinogen D fragment in the purified synovial exosomes [

49].

In our work, we extracted exosomes from RA patients' sera, and we confirmed the identity of these microparticles via TEM and DLS. Since cFBG is the most candidate antigen for ACPAs, the goal of our exosome analysis is to explore the presence of cFBG in these microparticles. We used WB to investigate the presence of cFBG in serum-derived exosomes from RA patients, particularly those with positive ACPAs. Several experiments have indicated the contribution of citrullinated proteins in RA pathogenesis. These works investigated cFBG in the serum [

100,

101,

102,

103] and synovium of RA patients [

48,

104,

105]. However, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study exploring the cFBG in exosomes extracted from RA patients' sera.

So, we look at whether cFBG is present in serum-derived exosomes from people with RA, especially those who have anti-CCP antibodies that are positive (SPRA). For this purpose, we performed WB using monoclonal anti-citrullinated fibrinogen antibodies. Our results showed that 36 of the 71 SPRA patients in this study expressed cFBG with clear bands at a molecular weight of about 56 kDa in their blotted exosomes. The other 35 SPRA patients did not express cFBG.

After correlation with seropositivity, our findings showed that all cFBG-positive exosomes had a positive anti-CCP, while among the 35 cFBG-negative exosomes, there were 27 patients tested negative for anti-CCP. To explain this, we suggest that these samples may include citrullinated proteins other than cFBG. Furthermore, we found that the titers of anti-CCP for cFBG-positive exosomes were significantly higher than those for cFBG-negative exosomes. Although 75% of patients with cFBG-positive exosomes were above 50 years of age and had RA for more than 5 years, we couldn’t conclude a specific association of cFBG with either patients' age or disease duration.

Figure 4.

Effect of smoking on autoantibodies. A) The anti-CCP is significantly (*) frequent in non-smokers (P=0.003). No significant difference (P>0.05) for the prevalence of RF and anti-CMCV in both groups. B) No impact of smoking on the titer of positive antibody (P>0.05). The comparison was performed using unpaired t-test, each bar represents the mean, and error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Effect of smoking on autoantibodies. A) The anti-CCP is significantly (*) frequent in non-smokers (P=0.003). No significant difference (P>0.05) for the prevalence of RF and anti-CMCV in both groups. B) No impact of smoking on the titer of positive antibody (P>0.05). The comparison was performed using unpaired t-test, each bar represents the mean, and error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 5.

Association between family history and seropositivity. A) Autoantibodies prevalence in RA patients with and without family history, shows no significant differences (P>0.05). B) No relationship between family history and the titer of a positive antibody. Each bar represents the mean, and error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. An unpaired t-test was used to compare the difference in means (P>0.05).

Figure 5.

Association between family history and seropositivity. A) Autoantibodies prevalence in RA patients with and without family history, shows no significant differences (P>0.05). B) No relationship between family history and the titer of a positive antibody. Each bar represents the mean, and error bars correspond to 95% confidence intervals. An unpaired t-test was used to compare the difference in means (P>0.05).

Figure 6.

Summary of exosome morphology by DLS. Zetasizer histograms represent the size distribution by intensity. A) SPRA B) SNRA C) HC. D) Exosomes isolated from SNRA patients revealed significant small diameter when compared to SPRA (***) and HC samples (**). (SPRA: seropositive RA patients, SNRA: seronegative RA patients, HC: Healthy Control individuals).

Figure 6.

Summary of exosome morphology by DLS. Zetasizer histograms represent the size distribution by intensity. A) SPRA B) SNRA C) HC. D) Exosomes isolated from SNRA patients revealed significant small diameter when compared to SPRA (***) and HC samples (**). (SPRA: seropositive RA patients, SNRA: seronegative RA patients, HC: Healthy Control individuals).

Figure 7.

TEM images of exosomes using negative staining. Exosomes showed round-shaped vesicles with diameters less than 100 nm; scale bar = 200 nm. Representative TEM micrograph of exosomes isolated from (A) SPRA, (B) SNRA, (C) HC. (SPRA: seropositive RA patients, SNRA: seronegative RA patients, HC: Healthy Control).

Figure 7.

TEM images of exosomes using negative staining. Exosomes showed round-shaped vesicles with diameters less than 100 nm; scale bar = 200 nm. Representative TEM micrograph of exosomes isolated from (A) SPRA, (B) SNRA, (C) HC. (SPRA: seropositive RA patients, SNRA: seronegative RA patients, HC: Healthy Control).

Figure 8.

A) Protein content of exosome lysates determined by the Pierce detergent- compatible Bradford assay. Significant differences in exosomes content of protein between patients and HC samples (P<0.001). B) Coomassie blue-stained gel showing protein band separation for exosome lysates from patient and healthy control samples. (SPRA: seropositive RA, SNRA: seronegative RA, HC: healthy control).

Figure 8.

A) Protein content of exosome lysates determined by the Pierce detergent- compatible Bradford assay. Significant differences in exosomes content of protein between patients and HC samples (P<0.001). B) Coomassie blue-stained gel showing protein band separation for exosome lysates from patient and healthy control samples. (SPRA: seropositive RA, SNRA: seronegative RA, HC: healthy control).

Figure 5.

A) Representative western blotting of CD9 in exosome sample groups: SPRA, ANRA, and HC. B) Western blot analysis for the expression of cFBG in exosome lysates that were extracted from SPRA patients. C) Variation of anti-CCP levels between SPRA patients according to the expression of cFBG in their exosome lysates. (SPRA: seropositive RA, SNRA: seronegative RA, HC: healthy control, cFBG: citrullinated fibrinogen).

Figure 5.

A) Representative western blotting of CD9 in exosome sample groups: SPRA, ANRA, and HC. B) Western blot analysis for the expression of cFBG in exosome lysates that were extracted from SPRA patients. C) Variation of anti-CCP levels between SPRA patients according to the expression of cFBG in their exosome lysates. (SPRA: seropositive RA, SNRA: seronegative RA, HC: healthy control, cFBG: citrullinated fibrinogen).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of RA patients and healthy controls.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of RA patients and healthy controls.

| Characteristic |

RA patients |

HC individuals |

P-value |

| (N=116) |

(N=35) |

| Gender |

|

|

|

| Female, n (%) |

104 (89.7%) |

28 (80%) |

0.13 |

| Male, n (%) |

12 (10.3%) |

7 (20%) |

| Age (mean±SD, years) |

51.3±11.5 |

47±11.6 |

0.05 |

| Age range, years |

(18-70) |

(23-66) |

| Age distribution, n (%) |

|

|

|

| <40 years |

20 (17.2%) |

9 (25.7%) |

0.26 |

| 40-50 years |

32 (27.6%) |

11 (31.4%) |

0.7 |

| >50 years |

64 (55.2%) |

15 (42.9%) |

0.2 |

| Occupation, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Worker |

26 (22.4%) |

11 (31.4%) |

0.28 |

| Retired |

7 (6%) |

2 (5.7%) |

0.94 |

| Housewife |

81 (69.8%) |

20 (57.1%) |

0.16 |

| Student |

2 (1.7%) |

2 (5.7%) |

0.2 |

| Smoking, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Smoker |

21 (18.1) |

NA |

|

| Non-smoker |

95 (81.9) |

NA |

|

| Family history of RA, n (%) |

|

|

|

| Yes |

25 (21.5) |

5 (14.3) |

0.35 |

| No |

91 (78.5) |

30 (85.7) |

Table 2.

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of RA patients.

Table 2.

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of RA patients.

| Characteristic |

All |

Female |

Male |

P-value |

| patients |

F/M |

| Number of patients, [n (%)] |

116 (100) |

104 (89.7) |

12 (10.3) |

|

| Age, mean±SD (Years) |

51.3±11.5 |

51.3±11.6 |

51.7±11.3 |

0.96 |

| Age group, [n (%)] |

|

|

|

|

| <40 years |

20 (17.2) |

18 (17.3) |

2 (16.7) |

0.9 |

| 40-50 years |

32 (27.6) |

30 (28.8) |

2 (16.7) |

0.37 |

| >50 years |

64 (55.2) |

56 (53.9) |

8 (66.6) |

0.4 |

| Disease duration, mean±SD |

8.4±6 |

8.7±6.2 |

6.1±3.8 |

0.16 |

| Disease duration, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| <5 years |

39 (33.6) |

35 (33.7) |

4 (33.3) |

0.98 |

| 5-10 years |

43 (37.1) |

36 (34.6) |

7 (58.4) |

0.11 |

| >10 years |

34 (29.3) |

33 (31.7) |

1 (8.3) |

0.09 |

| Smoking, [n (%)] |

|

|

|

|

| Smoker |

21 (18.1) |

17 (16.3) |

4 (33.3) |

0.15 |

| Non-smoker |

95 (81.9) |

87 (83.7) |

8 (66.7) |

| Family history of RA, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| Yes |

25 (21.6) |

23 (22.1) |

2 (16.7) |

0.66 |

| No |

91 (78.4) |

81 (77.9) |

10 (83.3) |

| Positive autoantibody, n (%) |

|

|

|

|

| RF positive |

43 (37.1) |

37 (35.6) |

6 (50) |

0.33 |

| Anti-CCP positive |

63 (54.3) |

55 (52.9) |

8 (66.7) |

0.36 |

| Anti-MCV positive |

56 (48.3) |

49 (47.1) |

7 (58.3) |

0.46 |

Table 3.

The prevalence and levels of positive antibodies among females and males.

Table 3.

The prevalence and levels of positive antibodies among females and males.

| Autoantibody |

Female |

Male |

P-value |

| N= 104 |

N= 12 |

| RF +ve, n (%) |

37 (36) |

6 (50) |

0.33 |

| RF Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

196.8 ± 236.6 |

356.4 ± 512.8 |

0.004 * |

| Anti-CCP +ve, n (%) |

55 (53) |

8 (67) |

0.36 |

| Anti-CCP (Mean±SD, (IU/ml)) |

547.8 ± 437.8 |

697.1 ± 420.6 |

0.37 |

| Anti-MCV +ve, n (%) |

49 (47) |

7 (58) |

0.46 |

| Anti-MCV Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

415.2 ± 406.6 |

589.2 ± 383.8 |

0.98 |

Table 4.

Prevalence and level of positive antibodies among age groups of RA patients.

Table 4.

Prevalence and level of positive antibodies among age groups of RA patients.

| Autoantibody |

<40 years |

40-50 years |

>50 years |

| N= 20 |

N= 32 |

N= 64 |

| RF+ve, n (%) |

4 (20) |

9 (28) |

30 (47) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

488.6 ± 490.9 |

206.8 ± 271.3 |

186.8 ± 251.0 |

| Anti-CCP+ve, n (%) |

9 (45) |

17 (53) |

37 (58) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

599.2 ± 454.5 |

587.7 ± 444.4 |

549.3 ± 437.9 |

| Anti-MCV+ve,n (%) |

7 (35) |

15 (47) |

34 (53) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

564.1 ± 423.9 |

399.3 ± 445.8 |

427.4 ± 389.5 |

Table 5.

Prevalence and level of positive autoantibodies over the period of RA duration.

Table 5.

Prevalence and level of positive autoantibodies over the period of RA duration.

| Autoantibody |

<5 years |

5-10 years |

>10 years |

| N= 39 |

N= 43 |

N=34 |

| RF, n (%) |

11 (28) |

18 (42) |

14 (41) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/L) |

234.3 ± 277.6 |

254.2 ± 379.7 |

161.9 ± 114.0 |

| Anti-CCP, n (%) |

19 (49) |

25 (58) |

19 (56) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/L) |

437.6 ± 438.5 |

627.0 ± 432.3 |

616.7± 430.9 |

| Anti-MCV, n (%) |

12 (31) |

27 (63) |

17 (50) |

| Mean±SD, (IU/L) |

440.9 ± 428.9 |

546.5 ± 435.3 |

260.2 ± 273.6 |

Table 6.

Comparison of positive autoantibodies among smokers and non-smoker RA patients.

Table 6.

Comparison of positive autoantibodies among smokers and non-smoker RA patients.

| Autoantibody |

Smokers |

Non-smokers |

P-value |

| N= 25 |

N= 91 |

| RF, n (%) |

7 (33) |

36 (38) |

0.7 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

170.9 ± 135.7 |

228.4 ± 308.5 |

0.41 |

| Anti-CCP, n (%) |

7 (33) |

56 (59) |

0.79 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

697.8 ± 425.2 |

538.3 ± 438.9 |

0.55 |

| Anti-MCV, n (%) |

8 (38) |

48 (51) |

0.35 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

522.1 ± 435.7 |

422.8 ± 402.3 |

0.57 |

Table 7.

Association between seropositivity and family history.

Table 7.

Association between seropositivity and family history.

| |

Positive family history |

Negative family history |

P-value |

| N= 25 |

N= 91 |

| RF, n (%) |

6 (24) |

37 (41) |

0.13 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

229.4 ± 306.1 |

192.7 ± 292.9 |

0.58 |

| Anti-CCP, n (%) |

13 (52) |

50 (55) |

0.79 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

519.4 ± 467.5 |

579.1 ± 430.5 |

0.55 |

| Anti-MCV, n (%) |

10 (40) |

46 (50) |

0.35 |

| Mean±SD, (IU/ml) |

322.5 ± 398.1 |

372.3 ± 389.7 |

0.57 |