Submitted:

08 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Data Collection Procedure

2.2. Instrument

2.3. Data Analysis Design

3. Results

3.1. Gender Differences and Bivariate Correlations

3.2. Regression and Mediational Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewin-Bizan, S.; Bowers, E. P.; Lerner, R. M. One good thing leads to another: Cascades of positive youth development among American adolescents. Development and psychopathology 2010, 22(4), 759-770. [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, R., & Wiium, N. Handbook of positive youth development: Advancing the next generation of research, policy and practice in global contexts (pp. 3-16). Springer International Publishing, 2021.

- Lerner, R. M.; Almerigi, J. B.; Theokas, C.; Lerner, J. V. Positive youth development a view of the issues. The journal of early adolescence 2005, 25(1), 10-16. [CrossRef]

- Bowers, E. P.; Li, Y.; Kiely, M. K.; Brittian, A.; Lerner, J. V.; Lerner, R. M. The five Cs model of positive youth development: A longitudinal analysis of confirmatory factor structure and measurement invariance. Journal of youth and adolescence 2010, 39, 720-735. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez Espinosa, A. D. C.; Wiium, N.; Jackman, D.; Ferrer-Wreder, L. Healthy lifestyle behaviors and the 5Cs of positive youth development in Mexico. Handbook of Positive Youth Development: Advancing Research, Policy, and Practice in Global Contexts 2021, 109-121.

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Wiium, N. Positive youth development and subjective happiness: examining the mediating role of gratitude and optimism in Spanish emerging adults. Handbook of positive youth development: Advancing research, policy, and practice in global contexts 2021, 187-202.

- Milot Travers, A. S.; Mahalik, J. R. Positive youth development as a protective factor for adolescents at risk for depression and alcohol use. Applied Developmental Science 2021, 25(4), 322-331. [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G. J.; Bowers, E. P.; Mueller, M. K.; Napolitano, C. M.; Callina, K. S.; Lerner, R. M. Longitudinal analysis of a very short measure of positive youth development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2014, 43, 933-949. [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, M. R.; Kofler, M. J.; Burns, G. L.; Luebbe, A. M.; Garner, A. A.; Jarrett, M. A.; Becker, S. P. Factor structure and criterion validity of the five Cs model of positive youth development in a multi-university sample of college students. Journal of youth and adolescence 2019, 48, 537-553. [CrossRef]

- Holsen, I.; Geldhof, J.; Larsen, T.; Aardal, E. The five Cs of positive youth development in Norway: Assessment and associations with positive and negative outcomes. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2017, 41(5), 559-569.

- Novak, M.; Šutić, L.; Gačal, H.; Roviš, D.; Mihić, J.; Maglica, T. Structural model of 5Cs of positive youth development in Croatia: relations with mental distress and mental well-being. International journal of adolescence and youth 2023, 28(1), 2227253.

- Marín-Gutiérrez, M.; Caqueo-Urízar, A.; Castillo-Francino, J.; Escobar-Soler, C. The 5Cs of positive youth development: their impact on symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, and emotional distress in Chilean adolescents. BMC psychology 2024, 12(1), 372.

- Pivec, T.; Kozina, A. Anxiety and COVID-19 anxiety in positive youth development: A latent profile analysis study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2023, 52(11), 2328-2343.

- Kozina, A.; Gomez-Baya, D.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Tome, G.; Wiium, N. The association between the 5Cs and anxiety—insights from three countries: Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain. Frontiers in psychology 2021, 12, 668049.

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Babić Čikeš, A.; Hirnstein, M.; Kurtović, A.; Vrdoljak, G.; Wiium, N. Positive youth development and depression: An examination of gender differences in Croatia and Spain. Frontiers in psychology 2022, 12, 689354. [CrossRef]

- Manrique-Millones, D.; Gómez-Baya, D.; Wiium, N. The importance of the 5Cs of positive youth development to depressive symptoms: A cross-sectional study with university students from Peru and Spain. Behavioral Sciences 2023, 13(3), 280. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, E.; Dennhag, I. Compassion in three perspectives: Associations with depression and suicidal ideation in a clinical adolescent sample. Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology 2023, 11(1), 120-127. [CrossRef]

- Saarinen, A.; Keltikangas-Järvinen, L.; Cloninger, C. R.; Veijola, J.; Elovainio, M.; Lehtimäki, T.; ... Hintsanen, M. The relationship of dispositional compassion for others with depressive symptoms over a 15-year prospective follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 250, 354-362. [CrossRef]

- Geldhof, G. J.; Larsen, T.; Urke, H.; Holsen, I.; Lewis, H.; Tyler, C. P. Indicators of positive youth development can be maladaptive: The example case of caring. Journal of Adolescence 2019, 71, 1-9.

- Schieman, S.; Turner, H. A. " When feeling other people's pain hurts": The influence of psychosocial resources on the association between self-reported empathy and depressive symptoms. Social Psychology Quarterly 2001, 376-389.

- Memmott-Elison, M. K.; Holmgren, H. G.; Padilla-Walker, L. M.; Hawkins, A. J. Associations between prosocial behavior, externalizing behaviors, and internalizing symptoms during adolescence: A meta-analysis. Journal of adolescence 2020, 80, 98-114.

- Andreychik, M. R.; Migliaccio, N. Empathizing with others’ pain versus empathizing with others’ joy: Examining the separability of positive and negative empathy and their relation to different types of social behaviors and social emotions. Basic and Applied Social Psychology 2015, 37(5), 274-291. [CrossRef]

- Andreychik, M. R.; Lewis, E. Will you help me to suffer less? How about to feel more joy? Positive and negative empathy are associated with different other-oriented motivations. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 105, 139-149. [CrossRef]

- Morelli, S. A.; Lieberman, M. D.; Zaki, J. The emerging study of positive empathy. Social and Personality Psychology Compass 2015, 9(2), 57-68.

- Morrison, A. S.; Mateen, M. A.; Brozovich, F. A.; Zaki, J.; Goldin, P. R.; Heimberg, R. G.; Gross, J. J. Empathy for positive and negative emotions in social anxiety disorder. Behaviour research and therapy 2016, 87, 232-242. [CrossRef]

- Telle, N. T.; Pfister, H. R. Positive empathy and prosocial behavior: A neglected link. Emotion review 2016, 8(2), 154-163. [CrossRef]

- Tomé, G.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Reis, M.; Gomez-Baya, D.; Coelhoso, F.; Wiium, N. Positive youth development and wellbeing: gender differences. Frontiers in Psychology 2021, 12, 641647.

- Wiium, N.; Wreder, L. F.; Chen, B. B.; Dimitrova, R. Gender and positive youth development. Zeitschrift für Psychologie 2019. [CrossRef]

- Conway, R. J.; Heary, C.; Hogan, M. J. An evaluation of the measurement properties of the five Cs model of positive youth development. Frontiers in psychology 2015, 6, 1941.

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Reis, M.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Positive youth development, thriving and social engagement: An analysis of gender differences in Spanish youth. Scandinavian journal of psychology 2019, 60(6), 559-568. [CrossRef]

- Stimpson, D.; Jensen, L.; Neff, W. Cross-cultural gender differences in preference for a caring morality. The Journal of Social Psychology 1992, 132(3), 317-322. [CrossRef]

- Van der Graaff, J.; Carlo, G.; Crocetti, E.; Koot, H. M.; Branje, S. Prosocial behavior in adolescence: Gender differences in development and links with empathy. Journal of youth and adolescence 2018, 47(5), 1086-1099. [CrossRef]

- Rueckert, L.; Branch, B.; Doan, T. Are gender differences in empathy due to differences in emotional reactivity? Psychology 2011, 2(6), 574.

- Rochat, M. J. Sex and gender differences in the development of empathy. Journal of neuroscience research 2023, 101(5), 718-729.

- Hankin, B. L.; Abramson, L. Y.; Moffitt, T. E.; Silva, P. A.; McGee, R.; Angell, K. E. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of abnormal psychology 1998, 107(1), 128.

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Salinas-Perez, J. A.; Sanchez-Lopez, A.; Paino-Quesada, S.; Mendoza-Berjano, R. The role of developmental assets in gender differences in anxiety in Spanish youth. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 13, 810326. [CrossRef]

- Leach, L. S.; Christensen, H.; Mackinnon, A. J.; Windsor, T. D.; Butterworth, P. Gender differences in depression and anxiety across the adult lifespan: the role of psychosocial mediators. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology 2008, 43, 983-998. [CrossRef]

- Charbonneau, A. M.; Mezulis, A. H.; Hyde, J. S. Stress and emotional reactivity as explanations for gender differences in adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Journal of youth and adolescence 2009, 38, 1050-1058. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zeng, X.; Su, J.; Zhang, X. The dark side of empathy: Meta-analysis evidence of the relationship between empathy and depression. PsyCh journal 2021, 10(5), 794-804.

- Sallquist, J.; Eisenberg, N.; Spinrad, T. L.; Eggum, N. D.; Gaertner, B. M. Assessment of preschoolers' positive empathy: concurrent and longitudinal relations with positive emotion, social competence, and sympathy. Journal of Positive Psychology 2009, 4(3), 223- 233.

- Hess, C.; Mesurado, B. Adaptación y validación de la Escala Disposicional de Empatía Positiva a población adolescente argentina. Acta Colombiana de Psicología 2023, 26(1), 27-44.

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R. L.; Williams, J. B. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. Journal of general internal medicine 2001, 16(9), 606-613.

- Muñoz-Navarro, R.; Cano-Vindel, A.; Medrano, L. A.; Schmitz, F.; Ruiz-Rodríguez, P.; Abellán-Maeso, C.; ... Hermosilla-Pasamar, A. M. Utility of the PHQ-9 to identify major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care centres. BMC psychiatry 2017, 17, 1-9.

- Spitzer, R. L.; Kroenke, K.; Williams, J. B.; Löwe, B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Archives of internal medicine 2006, 166(10), 1092-1097.

- García-Campayo, J.; Zamorano, E.; Ruiz, M. A.; Pardo, A.; Pérez-Páramo, M.; López-Gómez, V.; …Rejas, J. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale as a screening tool. Health and quality of life outcomes 2010, 8, 1-11.

- Silke, C.; Brady, B.; Boylan, C.; Dolan, P. Factors influencing the development of empathy and pro-social behaviour among adolescents: A systematic review. Children and Youth Services Review 2018, 94, 421-436. [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Baya, D.; Mendoza, R.; Paino, S.; Gillham, J. E. A two-year longitudinal study of gender differences in responses to positive affect and depressive symptoms during middle adolescence. Journal of Adolescence 2017, 56, 11-23. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Baya, D.; Mendoza, R.; Paino, S.; Gaspar de Matos, M. Perceived emotional intelligence as a predictor of depressive symptoms during mid-adolescence: A two-year longitudinal study on gender differences. Personality and individual differences 2017, 104, 303-312. [CrossRef]

- Rieffe, C.; De Rooij, M. The longitudinal relationship between emotion awareness and internalising symptoms during late childhood. European child & adolescent psychiatry 2012, 21, 349-356.

- Zahn-Waxler, C.; Van Hulle, C. Empathy, guilt, and depression. Pathological altruism 2011, 321-344.

- Andreychik, M. R. Feeling your joy helps me to bear feeling your pain: Examining associations between empathy for others' positive versus negative emotions and burnout. Personality and Individual Differences 2019, 137, 147-156.

- Jolliffe, D.; Farrington, D. P. Development and validation of the Basic Empathy Scale. Journal of adolescence 2006, 29(4), 589-611.

- Stosic, M. D.; Fultz, A. A.; Brown, J. A.; Bernieri, F. J. What is your empathy scale not measuring? The convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity of five empathy scales. The Journal of Social Psychology 2022, 162(1), 7-25. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar de Matos, M.; Santos, T.; Reis, M.; Gómez-Baya, D.; Marques, A. Positive youth development in Portugal: a tool towards gender equity? ARC Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 4(1), 25-35.

- Van Winkle, L. J.; Schwartz, B. D.; Michels, N. A model to promote public health by adding evidence-based, empathy-enhancing programs to all undergraduate health-care curricula. Frontiers in Public Health 2017, 5, 339. [CrossRef]

- Buffel du Vaure, C.; Lemogne, C.; Bunge, L.; Catu-Pinault, A.; Hoertel, N.; Ghasarossian, C., ... Jaury, P. Promoting empathy among medical students: A two-site randomized controlled study. Journal of psychosomatic research 2017, 103, 102-107.

- Levett-Jones, T.; Cant, R.; Lapkin, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of empathy education for undergraduate nursing students. Nurse education today 2019, 75, 80-94.

- Yang, C.; Zhu, Y. L.; Xia, B. Y.; Li, Y. W.; Zhang, J. The effect of structured empathy education on empathy competency of undergraduate nursing interns: A quasi-experimental study. Nurse education today 2020, 85, 104296. [CrossRef]

- Silke, C.; Davitt, E.; Flynn, N.; Shaw, A.; Brady, B.; Murray, C.; Dolan, P. Activating Social Empathy: An evaluation of a school-based social and emotional learning programme. Social and Emotional Learning: Research, Practice, and Policy 2024, 3, 100021.

- Cullen, J.; Bloemker, G.; Wyatt, J.; Walsh, M. Teaching a social and emotional learning curriculum: Transformative learning through the parallel process. International Journal of Higher Education 2017, 6(6), 163-169.

- Goodwin, J., Behan, L., Kelly, P., McCarthy, K., & Horgan, A. Help-seeking behaviors and mental well-being of first year undergraduate university students. Psychiatry research 2016, 246, 129-135. [CrossRef]

- Berardi, M. K. What are the most effective components of empathy education for undergraduate students to increase their empathy levels? The Pennsylvania State University, 2020.

- Kolb, D. A.; Boyatzis, R. E.; Mainemelis, C. Experiential learning theory: Previous research and new directions. In Perspectives on thinking, learning, and cognitive styles (pp. 227-247). Routledge, 2014.

| Overall M(SD) |

Women M(SD) | Men M(SD) |

t-test | Cohen’s d | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| 1.Positive Empathy | 3.44(.50) | 3.54(.47) | 3.25(.50) | 5.38*** | .697 | (.84) | .35*** | -.09 | -.25** |

| 2.Caring | 4.17(.59) | 4.28(.53) | 3.94(.65) | 5.29*** | .596 | .43*** | (.79) | -.01 | -.01 |

| 3.Depression | 9.24(5.41) | 9.69(5.56) | 8.19(4.88) | 2.48* | .280 | -.02 | .16* | (.84) | .73*** |

| 4.Anxiety | 8.48(5.53) | 9.34(5.65) | 6.57(4.84) | 4.54*** | .512 | .01 | .19** | .71*** | (.91) |

| Anxiety symptoms1 | Depressive symptoms2 | |||||

| F / R2 | β | t | F / R2 | β | t | |

| 7.66*** / .080 | 3.28* / .036 | |||||

| Gender | -.21*** | -3.92 | -.11* | -1.96 | ||

| Age | .05 | .97 | .06 | 1.19 | ||

| Caring | .17** | 2.90 | .14* | 2.29 | ||

| Positive empathy | -.12* | -2.02 | -.09 | -1.54 | ||

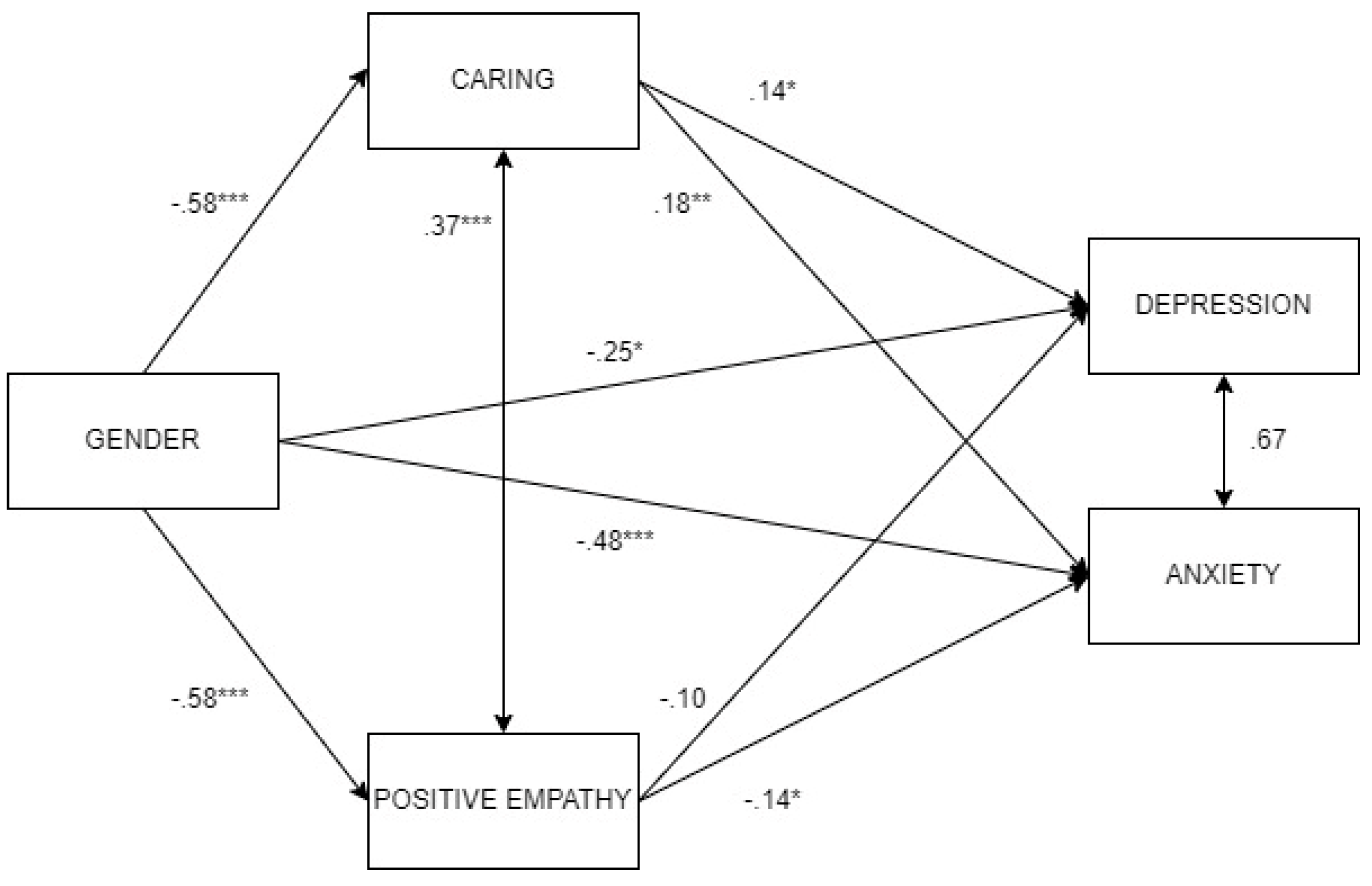

| Est | SE | Z | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| Direct effects | ||||||

| G->Dep | -.25 | .12 | -2.11 | .035 | -.48 | -.02 |

| G->Anx | -.48 | .11 | -4.18 | <.001 | -.70 | -.25 |

| Indirect effects | ||||||

| G-> Ca->Dep | -.08 | .04 | -2.23 | .026 | -.16 | -.01 |

| G->Em->Dep | .06 | .04 | 1.61 | .109 | -.01 | .13 |

| G->Ca->Anx | -.10 | .04 | -2.72 | .006 | -.18 | -.03 |

| G-> Em->Anx | .08 | .04 | 2.22 | .026 | .01 | .15 |

| Total effects | ||||||

| G->Dep | -.27 | .11 | -2.44 | .015 | -.49 | -.05 |

| G->Anx | -.50 | .11 | -4.55 | <.001 | -.71 | -.28 |

| Residual covariances | ||||||

| Ca<->Em | .37 | .05 | 7.03 | <.001 | .27 | .47 |

| Dep<->Anx | .67 | .06 | 11.04 | <.001 | .55 | .79 |

| Path coefficients | ||||||

| Ca->Dep | .14 | .06 | 2.45 | .014 | .03 | .26 |

| Em->Dep | -.10 | .06 | -1.68 | .093 | -.21 | .02 |

| G->Dep | -.25 | .12 | -2.11 | .035 | -.48 | -.02 |

| Ca->Anx | .18 | .06 | 3.17 | .002 | .07 | .29 |

| Em->Anx | -.14 | .06 | -2.44 | .015 | -.25 | -.03 |

| G->Anx | -.48 | .11 | -4.18 | <.001 | -.70 | -.25 |

| G-> Ca | -.58 | .11 | -5.32 | <.001 | -.79 | -.36 |

| G->Em | -.58 | .11 | -5.36 | <.001 | -.79 | -.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).