Submitted:

07 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theory of Linear Multistep Methods

3. Development of the New Symmetric Method

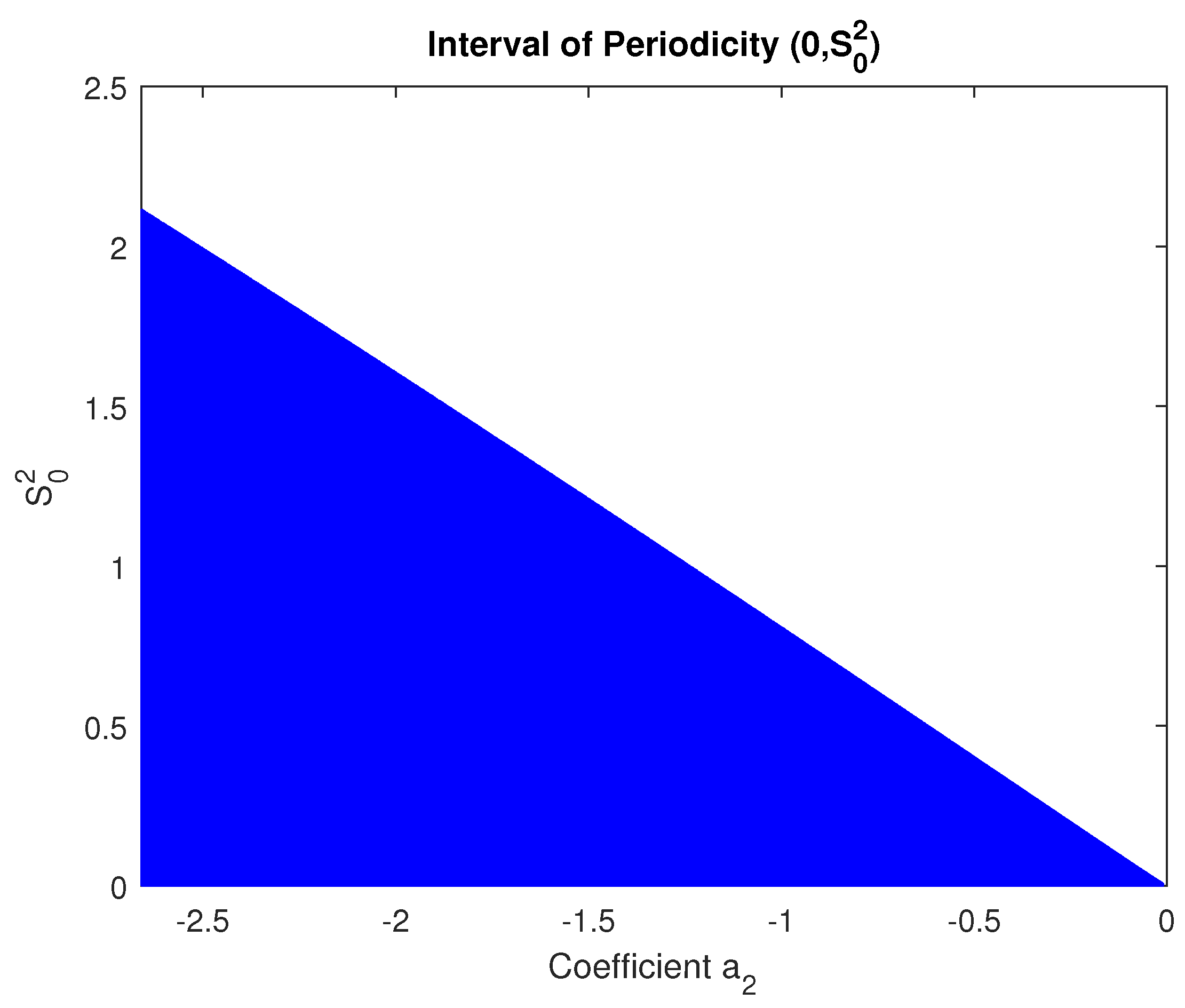

3.1. Local Truncation Error and Periodicity Analysis

4. Numerical Results

4.1. The Problems

- The Schrödinger equation - Resonance problem

- The "almost" periodic orbit problem by Stiefel and Bettis

- The Duffing equation

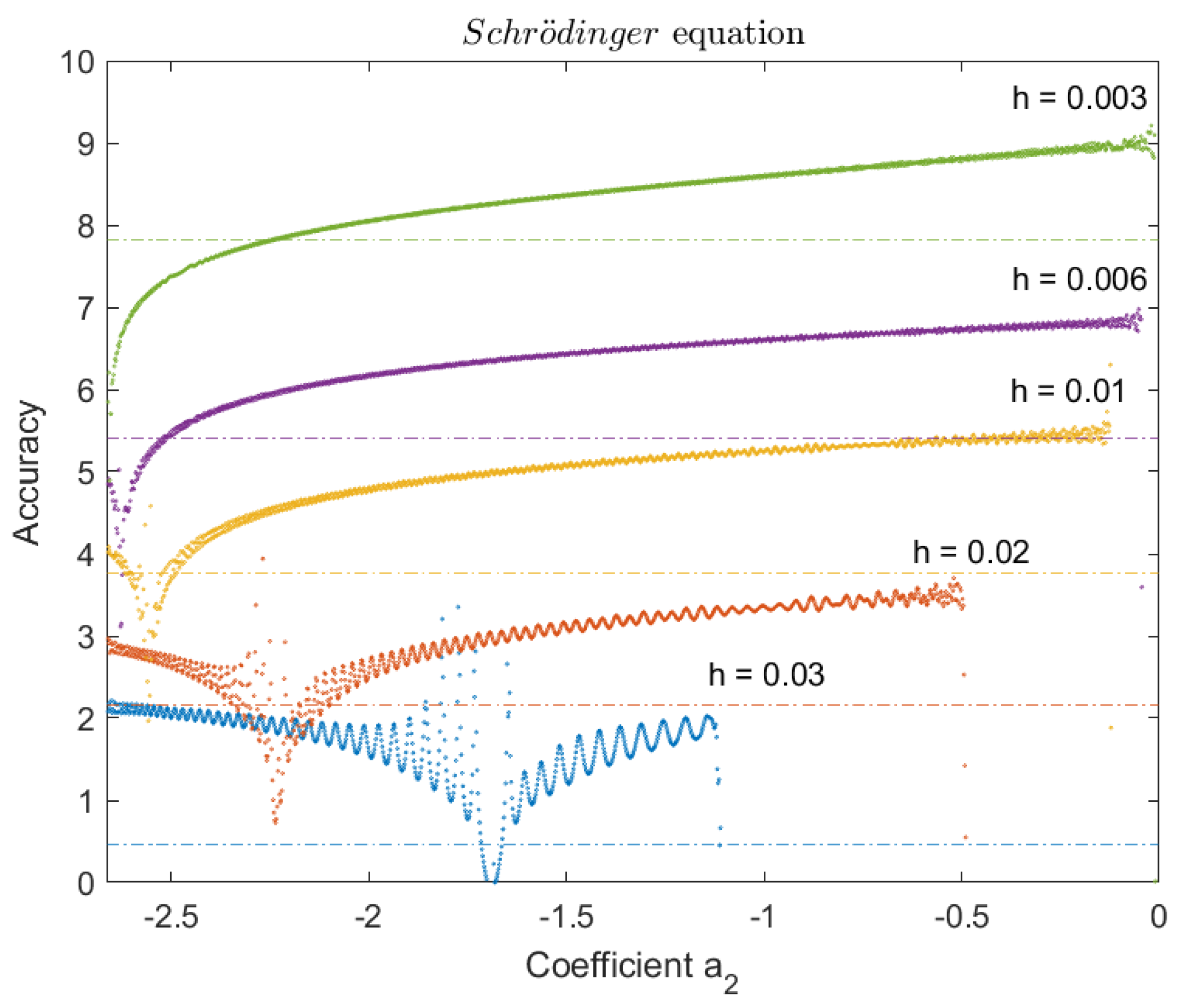

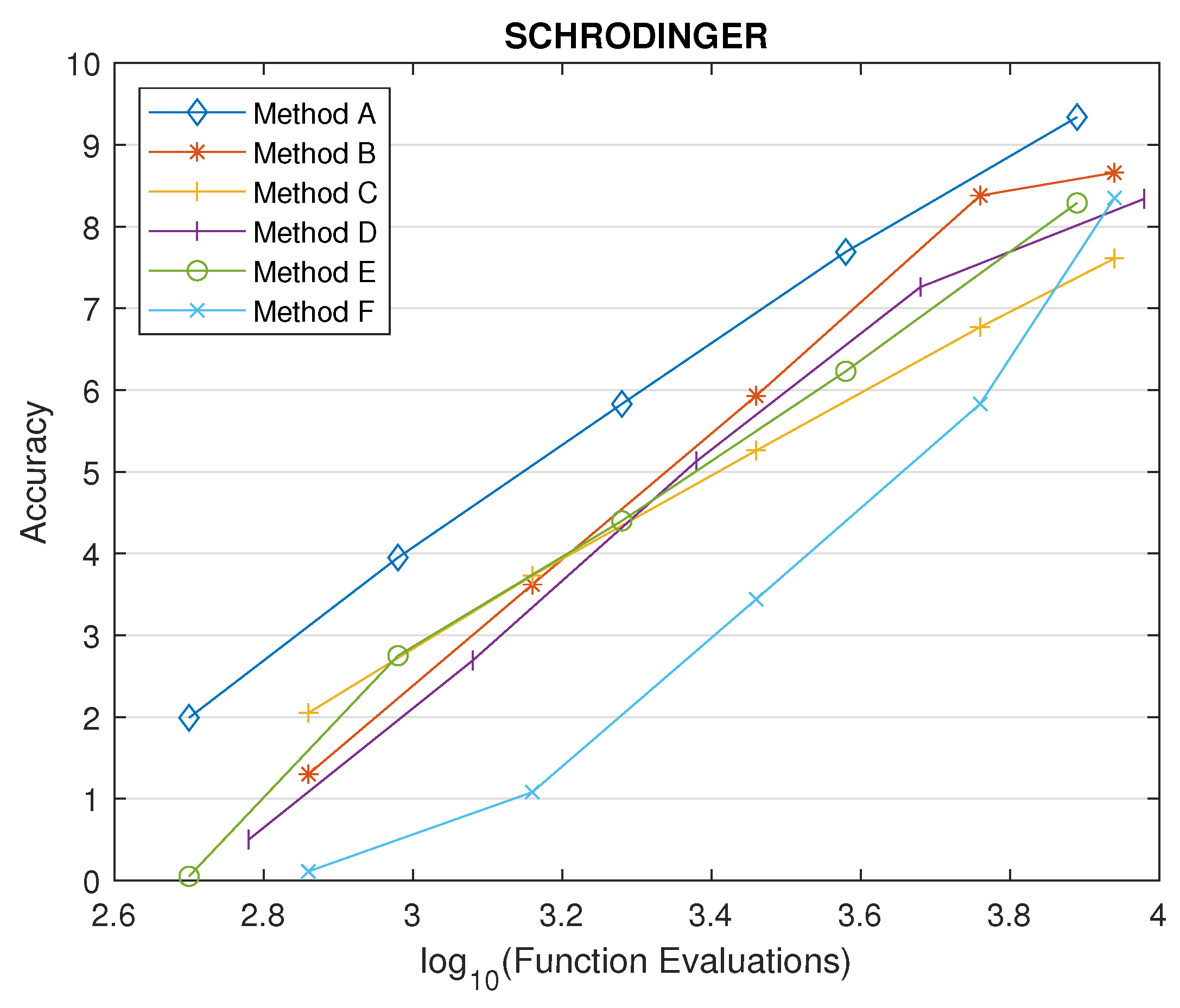

4.1.1. Schrödinger Equation - Resonance Problem

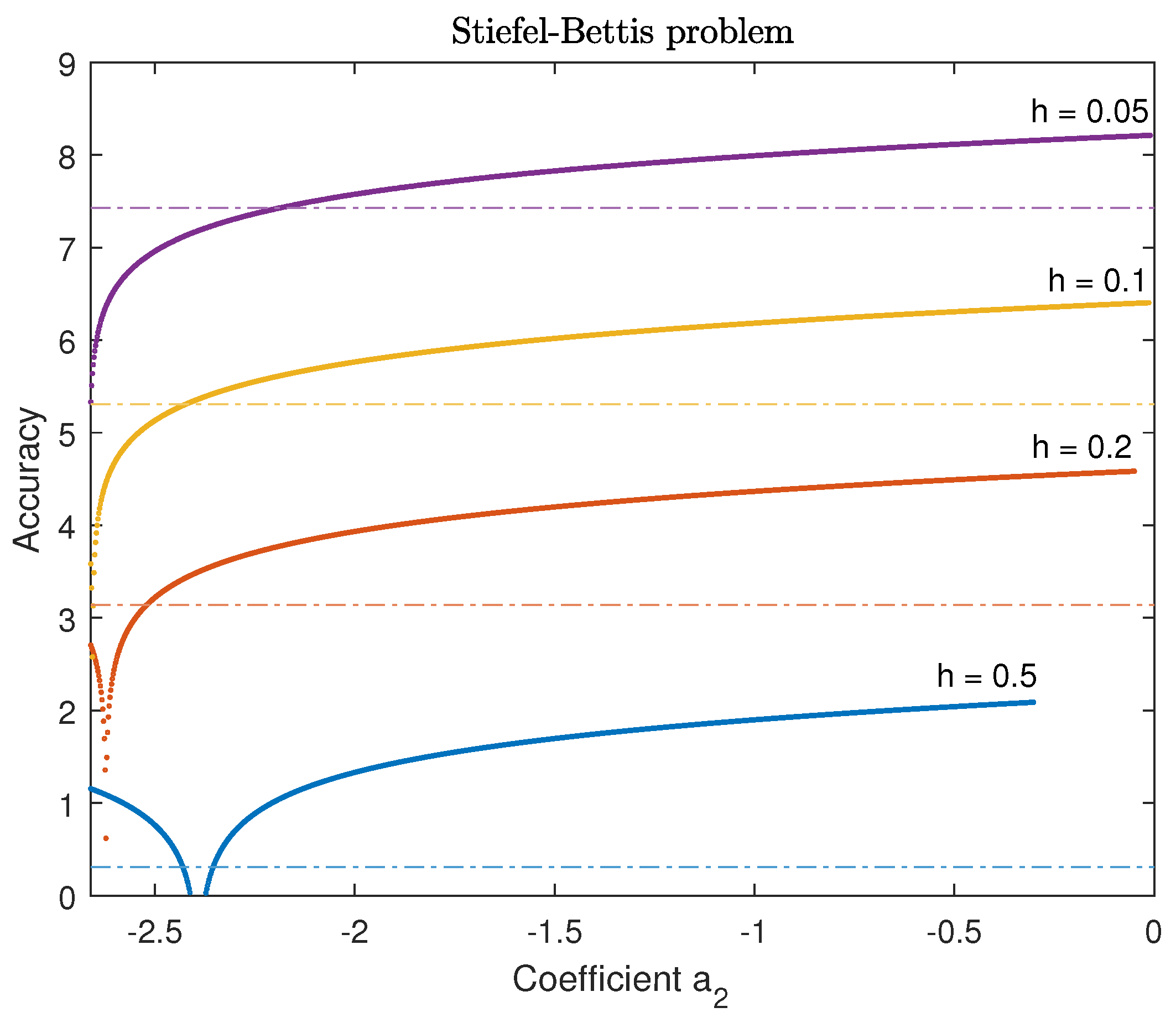

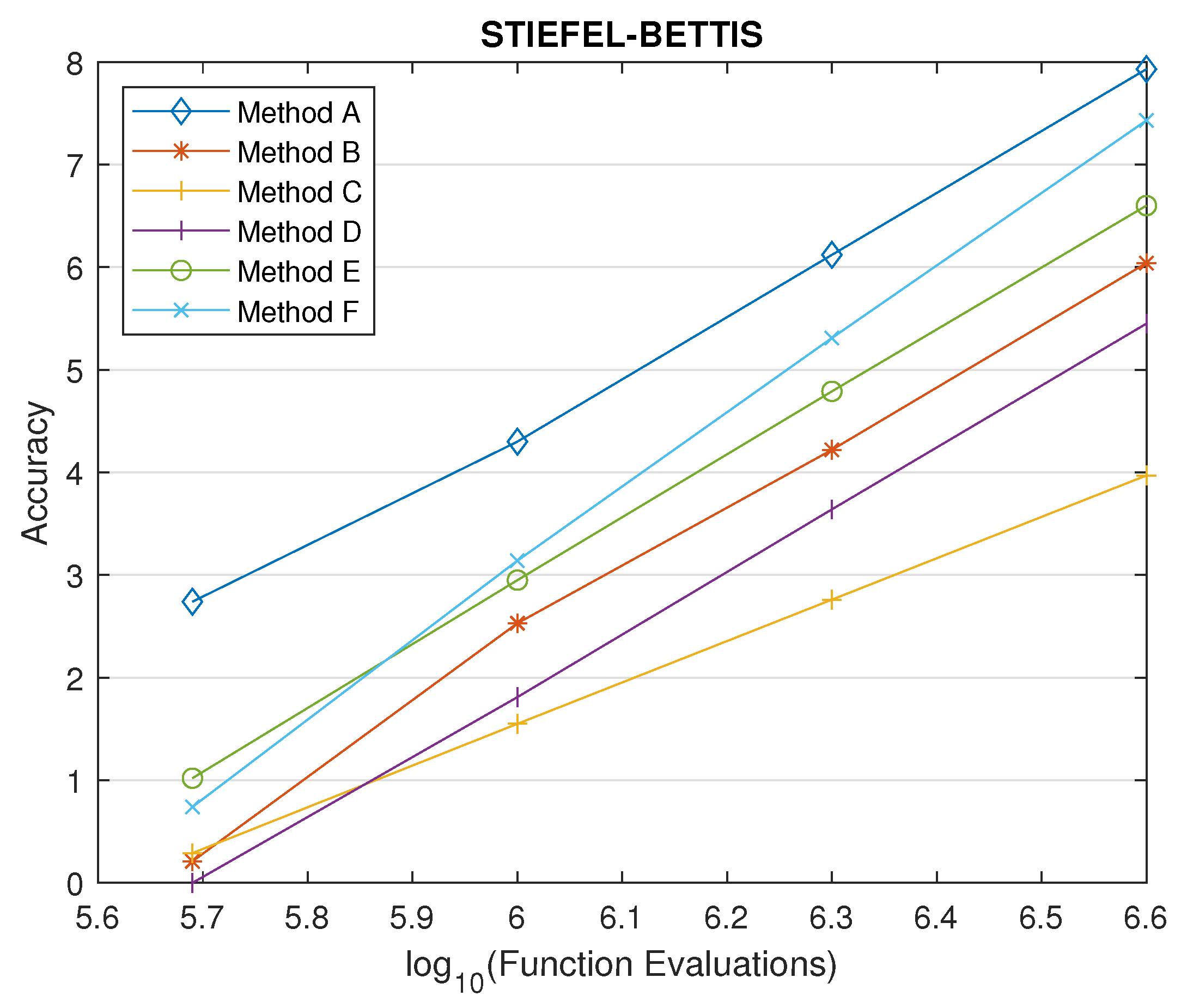

4.1.2. Orbit problem by Stiefel and Bettis

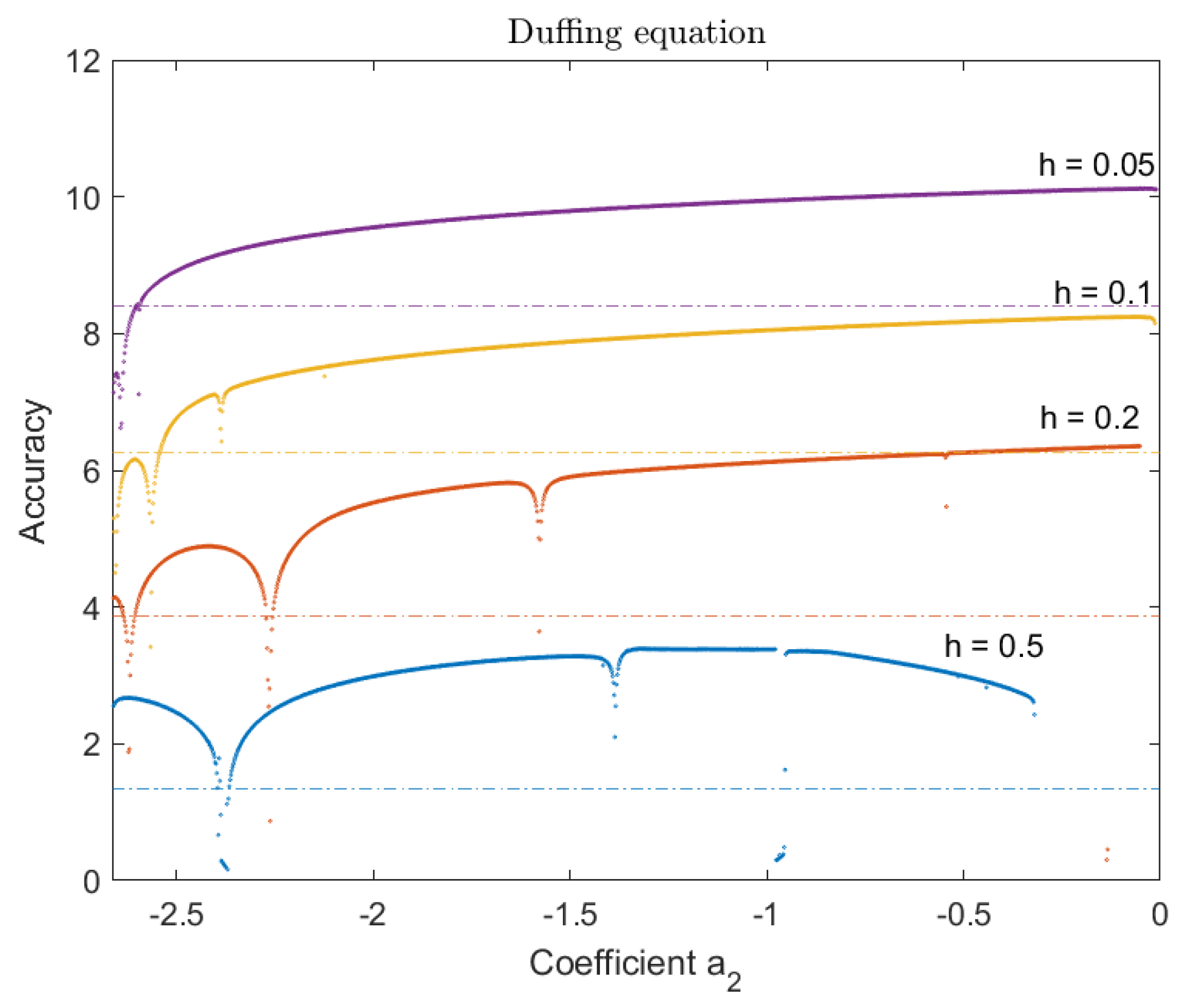

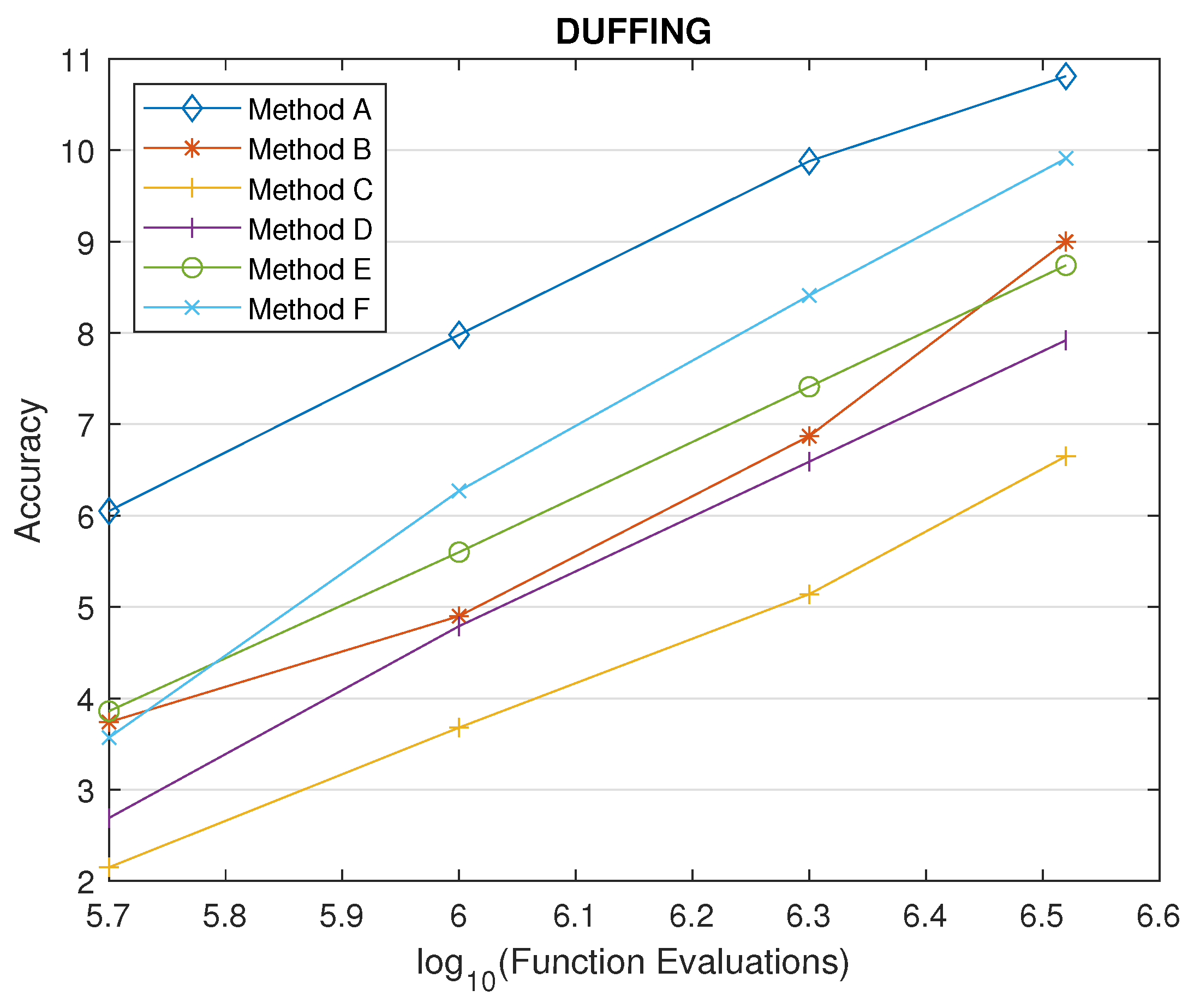

4.1.3. Duffing equation

4.2. The Compared Methods

- Method A: The new phase-fitted parametric method which was derived in Section 3 (for a wide range of parameter ).

- Method B: The 4-step phase-fitted method, developed by Simos [9].

- Method C: The Numerov-type hybrid method, developed by Konguetsof [14].

- Method D: The Runge-Kutta type hybrid method, developed by Alolyan and Simos [11].

- Method E: The zero-dissipative hybrid method, developed by Ahmad et. al [10].

- Method F: The high order method of the Runge-Kutta-Nyström pair, developed by Anastassi and Kosti [1].

4.3. Effectiveness and Optimal Values for the New Parametric Method

4.4. Comparison of the New Parametric Method with Other Phase-Fitted Methods Based on Optimal Values and Upper Limits for

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anastassi, Z.A.; Kosti, A. A 6(4) optimized embedded Runge–Kutta–Nyström pair for the numerical solution of periodic problems. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2015, 275, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monovasilis, T.; Kalogiratou, Z. High order two-derivative runge-kutta methods with optimized dispersion and dissipation error. Mathematics 2021, 9, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D.F.; Simos, T.E. A new methodology for the construction of optimized Runge–Kutta–Nyström methods. International Journal of Modern Physics C 2011, 22, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D.F.; Anastassi, Z.A.; Simos, T.E. A phase-fitted Runge–Kutta–Nyström method for the numerical solution of initial value problems with oscillating solutions. Computer Physics Communications 2009, 180, 1839–1846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulos, D.F.; Anastassi, Z.A.; Simos, T.E. The Use of Phase-Lag and Amplification Error Derivatives in the Numerical Integration of ODEs with Oscillating Solutions. International Conference on Numerical Analysis and Applied Mathematics. AIP Conference Proceedings, 2009, pp. 547–549.

- Tsitouras, C.; Famelis, I.T.; Simos, T.E. Phase-fitted Runge–Kutta pairs of orders 8(7). Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2017, 321, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. Dissipative trigonometrically fitted methods for the numerical solution of orbital problems. New Astronomy 2003, 9, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. An explicit four-step method with vanished phase-lag and its first and second derivatives. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 2014, 52, 833–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, T.E. An explicit four-step method for the numerical integration of second-order initial-value problems. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 1994, 55, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.; Ismail, F.; Senu, N.; Suleiman, M. Zero-dissipative phase-fitted hybrid methods for solving oscillatory second order ordinary differential equations. Applied Mathematics and Computation 2013, 219, 10096–10104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alolyan, I.; Simos, T.E. A new high order two-step method with vanished phase-lag and its derivatives for the numerical integration of the Schrödinger equation. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 2012, 50, 2351–2373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassi, Z.A.; Simos, T.E. A parametric symmetric linear four-step method for the efficient integration of the Schrödinger equation and related oscillatory problems. Journal of Computational and Applied Mathematics 2012, 236, 3880–3889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastassi, Z.A.; Simos, T.E. New Trigonometrically Fitted Six-Step Symmetric Methods for the Efficient Solution of the Schrödinger Equation. MATCH 2008, 60, 733–752. [Google Scholar]

- Konguetsof, A. Two-step high order hybrid explicit method for the numerical solution of the Schrödinger equation. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 2010, 48, 224–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medvedeva, M.A.; Simos, T.E. A multistep method with optimal phase and stability properties for problems in quantum chemistry. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 2022, 60, 937–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopoulos, G.; Anastassi, Z.A.; Simos, T.E. Two optimized symmetric eight-step implicit methods for initial-value problems with oscillating solutionsn. Journal of Mathematical Chemistry 2009, 46, 604–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psihoyios, G.; Simos, T.E. A New Trigonometrically-Fitted Sixth Algebraic Order P-C Algorithm for the Numerical Solution of Radial Schrödinger Equation. Mathematical and Computer Modelling 2005, 42, 887–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raptis, A.; Allison, A. Exponential-fitting methods for the numerical solution of the schrödinger equation. Computer Physics Communications 1978, 14, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z. P-stable linear symmetric multistep methods for periodic initial-value problems. Computer Physics Communications 2005, 171, 162–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, J.; Ixaru, L. P-stability and exponential-fitting methods for y” = f (x, y). IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics 1996, 16, 179–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, J.D.; Watson, I.A. Symmetric multistep methods for periodic initial values problems. IMA Journal of Applied Mathematics 1976, 18, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ixaru, L.; Rizea, M. A numerov-like scheme for the numerical-solution of the Schrödinger-equation in the deep continuum spectrum of energiess. Computer Physics Communications 1980, 19, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefel, E.; Bettis, D.G. Stabilization of Cowell’s Method. Numer. Math. 1969, 13, 154–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, G. Resonances and instabilities in symmetric multistep methods. arXiv:astro-ph/9901136v1, 1999. [Google Scholar]

| Value of | Accuracy |

|---|---|

| for high accuracy () | |

| for fast solution with low accuracy () | |

| for medium accuracy |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).