1. Introduction

Infectious diseases caused by pathogenic bacteria represent a significant threat to society, constituting one of the leading causes of mortality in developing countries and posing a critical challenge for developed nations [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. The urgent need for the development of novel, more efficient, and safe therapeutic approaches is paramount.

The complex and protracted treatment involving high-dose medications often leads to the emergence of a multitude of undesirable side effects, while bacterial strains simultaneously cultivate resistance and multidrug resistance (MDR) mechanisms [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13]. It is well-established that modern antibacterial agents of the third and fourth generations effectively eliminate pathogenic bacteria under in vitro conditions, often requiring relatively low dosages. However, their efficacy in vivo is significantly compromised, as they exhibit limited penetration into the targeted sites of bacterial localization, including within alveolar macrophages. The low bioavailability of certain drugs necessitates the administration of high doses, particularly in cases such as atypical intracellular pneumonia and pulmonary tuberculosis, which can persist for extended periods, posing a significant risk to the overall health of the patient.

Theranostic system that combines diagnostics and therapy into one molecular container, which allows early detection and effective treatment of diseases with minimal impact on healthy tissues of the body [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25]. Examples of theranostic include radionuclide, photodynamic, and thermotherapy. Herein, we suggest employing dyes and fluorophores as components of a synergistic theranostic formulation to enable the simultaneous diagnosis and treatment of diseases, including photodynamic therapy. This technology is embodied in therapeutics, which represents a unique fusion of a fluorescent dye and an antimicrobial agent in a single formulation. This approach allows for simultaneous visualization of the infection and targeted elimination of pathogens, resulting in more effective treatment while minimizing the adverse effects associated with traditional therapies.

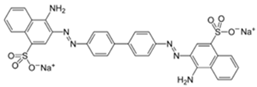

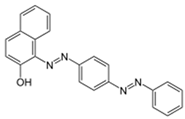

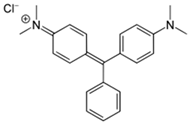

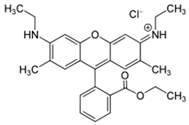

Here we propose to a combination of fluorophores and drugs, specifically antibiotics. The fluorophores used in the diagnostic system must satisfy the requirements of safety, biocompatibility, and effectiveness of their antimicrobial action. We have selected a set of promising fluorophores based on their biological activity, taking into account the literature indications on their anti-inflammatory properties. Some examples of bioactive fluorophores are listed below (

Table 1).

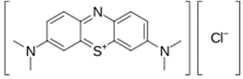

Methylene blue exhibits remarkable antibacterial properties, particularly effective against fungal infections [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The mode of action is related to its capacity to induce oxidative stress within microorganisms, leading to damage to their cellular membranes. Crystal violet (gentian violet), not only serves as a stain for staining bacteria, but also demonstrates activity against a wide range of gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, operating by disrupting the integrity of their cell walls [

33,

34]. The rhodamines 123, B, 6G, and its derivatives are employed as fluorophores, exhibiting pronounced antibacterial effects [

35,

36,

37,

38]. The mechanism of action relies on the photodynamic process, which involves the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under the influence of light (550-700 nm). Curcumin has been highlighted in numerous studies for its potent antibacterial and anti-inflammatory attributes. Curcumin interacts with bacterial cell membranes, permeating into cells and disrupting metabolic processes [

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45].

The employment of dyes and fluorophores possessing antibacterial activity presents a promising avenue in the battle against infections, particularly in the context of increasing antibiotic resistance. However, further exploration is required to elucidate their mechanisms of action, optimize their application, and assess their clinical efficacy. Combining these substances with conventional antibiotics may prove to be a strategic approach to enhance their antimicrobial potency and overcome antibiotic resistance.

The fluorophores exert the antibacterial or cytotoxic effects through various mechanisms (

Table 1).

Table 1.

Mechanisms of antibacterial or cytotoxic effects of dyes and fluorophores.

Table 1.

Mechanisms of antibacterial or cytotoxic effects of dyes and fluorophores.

| Mechanism |

Description |

Examples |

| Intercalation in DNA |

A wide range of dyes are capable of binding to DNA, interfering with the processes of replication and transcription processes. Dues establish hydrogen bonds with the bases of DNA, thereby hindering its functional activity. |

Acridine orange [28,46,47],

Methylene blue [28],

Ethidium bromide [28,48,49],

Proflavine, doxorubicin [50] |

| Damage to the Cell Membrane |

Certain dyes can interact with the phospholipids of a bacterial cell membrane, resulting in its destruction and ultimately leading to cell lysis. Lipophilic compounds tend to accumulate within the membrane, disrupting the functionality of ion pumps and enhancing proton permeability. The toxic effects of these compounds on membranes can manifest themselves through mechanisms such as membrane blockage and expansion of membranes. |

Sudan dyes [51,52],

Indocarbocyanine derivatives [53],

Alexa and Atto [54] |

| Oxidative Stress |

Fluorophores like rhodamine contribute to oxidative stress within cells by inducing the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS cause damage to cellular structures, including lipids, proteins, and DNA |

Doxorubicin [55],

Fluorescein and rhodamine derivatives [56] |

| Ionization and Metabolic Disorders |

Disruption metabolic processes, hindering the synthesis of ATP or the biosynthesis of cellular components, inhibition of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation |

Rhodamine 6G [57], Fluorescein Analogues [58] |

| Use in photodynamic therapy |

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a minimally invasive treatment that involves the use of a photosensitizing agent, usually a dye, and a specific wavelength of light. When a photosensitizing agent absorbs light, it generates ROS that damage target cells. The dyes used in PDT are carefully selected to ensure that they can penetrate the tissues and affect certain cells or structures of the body. They are usually water-soluble or fat-soluble, depending on the location of the desired exposure. |

Phthalocyanines, Porphyrins, Chlorins [59,60,61,62], Methylene blue [31], Rhodamine 123 [63] |

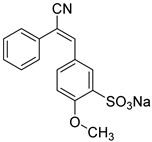

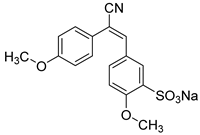

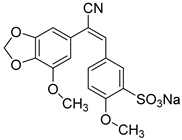

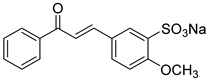

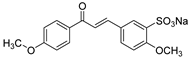

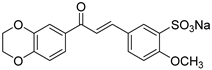

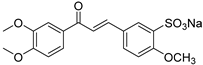

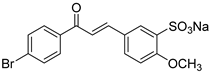

As candidates to the antibacterial agents here we are exploring a set of bioactive substances of different class such as chalcones, cyano-methoxychromene, stilbenoids and, xanthylium derivatives, in comparison with the well-known antiseptic agents, with the aim of uncovering their novel properties and expanding their applications. The investigation of the antibacterial potential of “drug candidates” assumes particular significance in light of the escalating issue of multidrug resistance. They can serve as alternative antimicrobial agents or be combined with conventional antibiotics or cytostatic drugs to enhance their efficacy.

The use of adjuvants derived from natural extracts, chalcones, cyano-methoxychromene, stilbenoids and their derivatives in a single delivery system with antibiotics is expected to enhance the efficacy of drugs while reducing the risk of side reactions. These compounds may exhibit synergistic effects with antibiotics, potentially mitigating the development of bacterial resistance.

A notable group of promising compounds in this category are stilbenoids and chalcones [

64,

65,

66,

67,

68], that have been gaining attention among researchers due to their promising bioactive properties. Stilbenoids are chemical compounds based on the structure of so-called E-stilbene, a condensed ring system with the formula R-C

6H

4-CH=CH-C

6H

4-R

1, where R and R

1 represent various substituents. Naturally compounds stilbenoids exhibit a wide range of biological activities, including antitumor and antimalarial effects. Moreover, many stilbene derivatives demonstrate antibacterial activity, as exemplified by a compound extracted from the leaves of

Combretum woodii. These substances have anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, antitumor, cardiovascular and neuroprotective properties. They are low-molecular-weight compounds, such as resveratrol, pterostilbene and many others. Tamoxifen and raloxifene are synthetic stilbene derivatives approved by the FDA and are prescribed for various skin conditions [

69]. Due to their poor water solubility, stilbenoid derivatives face significant challenges in medical applications. Chalcones and stilbenoids are being considered as potential novel medications for the treatment of inflammatory conditions, cancer, and infections.

In this paper, we also discuss a class of chromenes (Benzopyran derivatives) – substances with various biological properties that are widely found in nature [

70,

71]. Compounds with a chromene framework exhibit many properties, including antibacterial and fungicidal action, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity. However, chromenes are practically insoluble in water, which makes their use difficult. To address this challenge, it became necessary to synthesize water-soluble chromene derivatives. These derivatives would solve the problem of low solubility in water, making it easier to use chromenes in various applications.

For the delivery of a combine theranostic composition, we propose using cyclodextrin as the basis for creating a joint delivery system. Cyclodextrin (CD) is a natural cyclic oligosaccharide with a unique ability to form inclusion complexes with various molecules (as well as the possibility of forming double complexes), including medicinal substances and radioactive isotopes, which makes it an ideal candidate for the creation of theranostic delivery systems. Many promising pharmaceutical compounds face a critical challenge in the form of their poor solubility and inadequate potency, which significantly hinders their clinical development and necessitates the search for innovative solutions. Among the promising strategies, the employment of cyclodextrins (CDs) stands out as a promising avenue. These molecules have the unique ability to form complexes with active pharmaceutical ingredients, enhancing their solubility and bioavailability, ultimately leading to enhanced efficacy and expanded therapeutic potential [

72,

73,

74,

75,

76,

77,

78,

79]. They exhibit unique properties, including the capacity to form complexes with a variety of drug molecules, rendering them valuable in the fields of pharmaceuticals and the food industry. The incorporation of dyes into cyclodextrin structures can significantly augment their antibacterial efficacy by facilitating the targeted delivery of active molecules and enhancing their bioactivity. CD possesses a hydrophobic interior space and a hydrophilic exterior shell, enabling them to engage in complexation with a diverse range of molecules, including both dyes and pharmaceuticals.

The advantages of using CD to enhance the therapeutic potential of “drug candidates”:

Enhanced aqueous solubility: This attribute is particularly crucial for substances with limited solubility in water, as enhanced bioavailability translates into more potent antibacterial efficacy.

Resistance to degradation: Incorporation into the CD shields dyes from the deleterious effects of light, heat, and oxygen, thereby enhancing their stability and prolonging their shelf life.

Optimized targeted delivery: The use of cyclodextrins enhances the precision of dye delivery to the site of infection, mitigating toxicity to healthy cells. This feature is particularly advantageous in bacterial infection treatment, as it minimizes adverse reactions.

In our study, we investigated a range of biologically active substances of natural origin as «drug candidates» in comparison with known antibiotics, to assess their potential for use in the development of a highly effective theragnostic system that incorporates a fluorophore and an antibacterial agent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

2.1.1. Chemicals

Rhodamine 6G (R6G), methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA). Dyes, salts for the preparation of buffer solutions, NaOH, and HCl were produced by Reachim (Moscow, Russia). Components for LB medium were bactotrypton, agarose and yeast extract (Helicon, Russia), NaCl (Sigma Aldrich, USA).

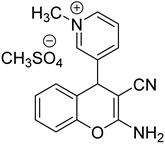

2.1.2. Preparation of– 1-Methyl-3-(2-Amino-7-Methoxy-3-Cyanochromene-4-yl) and Pyridinium Methanesulfate (Sample 17)

Stage 1. Preparation of 2-Amino-7-methoxy-4-(pyridine-3-yl)-3-cyanochromene.

0.3 g of triethylamine was added to a solution of 1.07 g (10 mmol) nicotinic aldehyde, 0.66 g (10 mmol) malonic nitrile and1.24 g (10 mmol) 3-methoxyphenol in 12 ml of methanol. The reaction mixture was boiled for 4 hours. Then cooled to 0—5 °C and left overnight. The precipitate was filtered, washed with cold methanol and dried. 1.7 g of the substance (60%) was obtained. Tmelt = 224-227 °C. 1H NMR spectrum (DMSO-d6): 3.76 s(3H, OCH3), 4.82 s(1H, Hch(4)), 6.62 s (1H, Hch(8)), 6.72 d (1H, Hch(6)), 6.94d (1H, Hch(5)), 7.04 s ((2H, NH2), 7.34 t(1H, Hpd(5)), 7.55 d (1H,Hpd(4)), 8,46 d (1H, Hpd(6)), 8,50 s (1H, Hpd(2)).

Stage 2. Preparation of Sample 17 (1-methyl-3-(2-amino-7-methoxy-3-cyanochromene-4-yl) pyridinium methanesulfate).

A mixture of 0.56 g (2 mmol) of Sample X and 0.32 g (2.6 mmol) of dimethyl sulfate in 5 ml of methanol was boiled for 4 hours. Then the solvent was evaporated at reduced pressure and the residue was ground in a mixture of ethyl acetate-petroleum ether = 1:2. After the start of crystallization, the mixture was left overnight. The fallen crystals were filtered, washed with a mixture of ethyl acetate-petroleum ether = 1:2 and dried. The yield is 0.6 g (80%). Tmelt = 186-192 °C. 1H NMR spectrum (DMSO d6): 3.40 s (3H, N-CH3), 3.76 s(3H, N-CH3), 3.76 s (3H, CH3O), 4.36 s (3H, CH3OSO3-), 5.12 s(1H, Hch(4)), 6.63 s (1H, Hch(8)), 6.76 d (1H, Hch(6)), 8.90 d (1H, Hpd(6)), 9,04 s (1H, Hpd(2)).

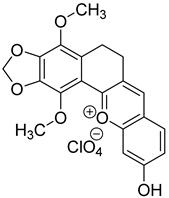

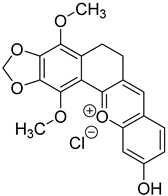

2.1.3. Synthesis of R351 Compounds of Xanthylium Derivatives

The synthesis of R351 compounds of xanthylium derivatives was carried out by the Claisen-Schmidt condensation reaction from apiol-tetralone and 2,4-dihydroxybenzaldehyde in methanol with the addition of HCl or HClO4.

2.1.4. Synthesis of the Chalcone and Stilbenoid Derivatives

Samples, from 7 to 15 inclusive, are obtained by the Claisen-Schmidt reaction in an aqueous alcohol medium in the presence of alkali. The reaction between ketones and sulfo-anisic aldehyde proceeds at 20 °C for 6-8 hours. The precipitate that has fallen out of the solution is filtered, washed with alcohol, and dried. The yield of the condensation product is 95-98%. If the corresponding nitrile derivatives are used instead of ketones, the reaction proceeds at 0–5 °C [

80,

81].

2.2. Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MCD) Inclusion Complexes Obtaining

2.2.1. Complexation in an Aqueous Buffer Solution

To 2–3 mg of the substance, add 1 mL of MCD solution in PBS (10 mM, pH 7.4). The molar ratio of cyclodextrin to the guest is varied from 0.25 to 10. The mixture is incubated at 37°C for 1 h. After that, it is centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 5 min to separate insoluble fractions. The obtained complexes are analyzed spectroscopically (UV and FTIR) to determine the solubility of the compound and the parameters of the complexation.

2.2.2. Complexation in Organic Solvent

Mix 2–5 mg of an aromatic substance with 5–50 mg of MCD, and then add 200 mL of acetonitrile. Thoroughly mix the mixture (rubbing method), and if necessary, use another volatile organic solvent. Incubate the solution at 37 °C for 1 h, then dry the complexes at an elevated temperature in a stream of dry air.

2.2.3. Calculation of Solubility of Compounds and Dissociation Constants of Complexes with MCD

The calculation of the solubility of compounds and the dissociation constants of complexes with MCD was carried out as described earlier [

73,

82].

2.3. Molecular Absorption Spectroscopy and CD Spectroscopy in the UV/Visible Range

UV/visible absorption spectra of solutions of the studied substances and its MCD-complexes were recorded on the AmerSham Biosciences UltraSpec 2100 pro device (USA). Circular dichroism spectra were recorded on Jasco J-815 CD Spectrometer (JASCO, Tokyo, Japan).

2.4. FTIR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectra of samples in the dispersed state were obtained using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer (Bruker, Ettlingen, Germany), FTIR spectra of samples in the solid state were obtained using a MICRAN-3 IR microscope (Simex, Novosibirsk, Russia) equipped with a cooled MCT detector. The spectra were obtained in the ATR mode.

2.5. NMR Spectroscopy

The 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of free substances in d6-DMSO and complex substances with MCD in D2O were registered on a Bruker DRX-500 device [working frequencies of 500.13 MHz (1H) and 125.76 MHz (13C)]. Chemical shifts were expressed in parts per million (ppm) and assigned to the appropriate NMR solvent peaks.

2.6. Microbiology Experiments

2.6.1. Bacterial Strains

In this study, we utilized two bacterial strains: Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922) obtained from the National Resource Center of the Russian Collection of Industrial Microorganisms at SIC “Kurchatov Institute,” and Lactobacillus, which was a commercially available lactobacillus liquid concentrate. The cultures were cultivated for 18–20 hours at 37 °C to achieve an approximate concentration of 2×10⁷ CFU/ml. This concentration was determined through measurement of optical density (A600) and plating onto Petri dishes. The nutrient medium employed, Luria–Bertani, possessed a pH of 7.2 and was agitated at 120 rpm.

2.6.2. Antibacterial Testing

Suspensions of cells containing 10⁷ CFUs were subjected to incubation with solutions of the studied substances and the MCD-complexes. The incubation period lasted 24 hours at 37 °C. Following incubation, cell viability was assessed through optical density measurement (A700) and confirmed via plating of the cell suspensions onto plates. These plates were subsequently incubated at 37 °C for a further 24 hours to allow for colony formation. Colonies-forming units (CFUs) were subsequently determined.

2.6.3. Visualization of Plates Using Fluorescent Images

Fluorescent images of plates containing E. coli (10⁷ CFUs/0.5 ml) placed on 20 ml agar were acquired using the UVP BioSpectrum Imaging System (BioSpectrum, UVP, Upland, CA, USA). The fluorophore wells had a diameter of 0.9 cm, with fluorophore (R6G or FITC, or R351) concentrations of 0.1-1 mg/ml. The excitation wavelength (λexci, max) was set at 480 nm, and emission wavelengths ranged between 515–570 nm.

2.7. CLSM of Staining of Bacterial Cells Using a Theranostic Fluorescent Preparation

The study involved visualizing the staining of bacterial cells using a theranostic fluorescent preparation. Bacterial cells, with a concentration of 5×106 cells per mL, were incubated with different concentrations of R6G and complexes with MCD. After incubation, the cells were subjected to double washing for 5 minutes at 8000 × g and then transferred to 96-well plates. The cells were subsequently fixed with paraformaldehyde and filled with 70 μL of a solution containing 50% glycerol and PBS. Confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) images were acquired using an Olympus FluoView FV1000 confocal microscope equipped with a spectral scanning unit and a transmitted light detector. The measurements were performed using an Olympus UPLSAPO 40X NA 0.90 dry objective lens. Fluorescence emission was collected through emission windows set at 510-560 nm (green channel) and 560-610 nm (red channel).

2.8. Antioxidant Activity Using ABTS Assay

The capacity of the drug formulations to neutralize free radicals was assessed using the ABTS assay, as outlined in papers [

83,

84]. This method involved measuring the absorbance at a wavelength of 734 nm of an ABTS cation radical in the presence of the drugs. The results are presented in comparison with the reference antioxidant quercetin.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Drug Candidates

Table 2 present the compounds under investigation encompasses a variety of antimicrobial dyes, including “drug candidates” chalcone, stilbenoid, cyano-7-methoxychromene and xanthylium derivatives, R351, as well as antiseptic agents and antibiotics (

Table 2).

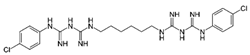

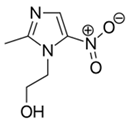

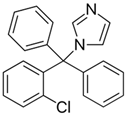

To create a combined theranostic antibacterial system, we have selected derivatives of natural compounds such as chalcones and stilbenoids and dyes/fluorophores as study objects, as they exhibit a broad spectrum of pharmacological activities, including antibacterial and antioxidant properties. These substances can act in synergy, amplifying the efficacy of antibiotic therapy, for example, metronidazole main component enhancement. To optimize the synergistic effect, we have developed a common delivery system to create effective drugs system for combating infections.

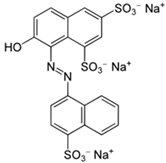

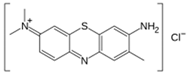

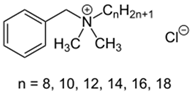

Such dyes as crystal violet, congo red, Sudan III, malachite green, rhodamine 6G, methylene blue, ponceau 4R and toluidine blue have antibacterial activity against various microorganisms. Xanthylium derivatives such as R351-ClO

4- and R351-Cl- are considered as perspective antibacterial agents. Some chalcones and stilbenoids exhibit antibacterial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria [

85,

86]. Among other applications, they can serve to inhibit the efflux of antibiotics in bacteria that are resistant or have developed multiple resistances [

67]. Previous studies of chalcons and stilbenoids that do not contain sulfogroups revealed their antibacterial and cytostatic properties, but their low solubility in water limited their use. Here the sulfo-derivatives of chalcons and stilbenoids are investigates as perspective antibacterials. The introduction of sulfogroups, increasing solubility, creates new opportunities that require studying the effect on the activity of water. Benzalkonium chloride and chlorhexidine are well-known antiseptics with high antibacterial activity. Metronidazole is an antibiotic that is effective against anaerobic bacteria, while clotrimazole is an antifungal drug with antibacterial properties.

The issue of suboptimal drug efficacy and the development of bacterial resistance necessitates the search for innovative solutions. We suggest a theranostic agent by combining the primary drug with adjuvants derived from the class of chalcones or dyes/fluorophores. Theranostics encompasses the diagnosis of infections and inflammatory conditions, as well as their concurrent treatment. Of particular interest is the study of the effect of CD as a molecular container on the effectiveness of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory agents. We expected that the use of CD for the inclusion of drugs and adjuvants could increase their effectiveness and bioavailability, which opens up new therapeutic options. This approach can also be used to create antioxidant formulations, expanding the range of applications of cyclodextrins in medicine.

3.2. Molecular Absorption Spectroscopy of Dyes and Its Complexes with MCD

Figure 1 presents the absorption spectra of the investigated dyes in free form in a buffer solution and complexed with methyl-cyclodextrin (MCD). Upon the formation of these complexes, there is a discernible decrease in absorption intensity, which can be attributed to the formation of a complex that affects the physicochemical properties of the dyes. The incorporation of dyes such as Congo red, Methylene Blue, and others into the hydrophobic interior of MCD results in several critical changes.

Firstly, shifts in absorption maximum were detected. For example, the inclusion of congo red in the MCD is accompanied by a shift of the absorption maximum in the long-wavelength region from 490 to 495 nm, and in the case of Xanthylium derivatives R351, a shift is observed in the short-wavelength region from 520 to 512 nm, which correlates with alterations in its microenvironment upon interaction with MCD.

Secondly, there is a decline in the potency of absorption for the majority of dyes due to the influence of radiation shielding. The development of these complexes results in a partial protection of dye molecules from interaction with the solvent, potentially diminishing their capacity for absorbing light.

Moreover, modifications in the spectral pattern occur when dye–MCD complexes of the “guest–host” type are formed. In the case of Malachite Green, there is an augmentation in the proportion of the short-wavelength component by 425 nm, which corresponds to an increase in the fraction of monomeric species (dissociation of microcrystals). Analogous alterations are observed for xanthylium derivatives such as R351.

Table 3 presents the physico-chemical characteristics of the dyes, including their molar weights and molar absorptivity coefficients. These data provide valuable insights into prediction the behavior of these dyes in various chemical environments and optimize their use in applications ranging from staining biological tissues to developing colored materials.

MCD, a cyclic oligosaccharide, enhances the solubility of various compounds, including dyes in aqueous solution. In the presence of MCD at a concentration of 5 mM, the solubility typically increases by several orders of magnitude compared to that in PBS solution (

Table 3). The mechanism underlying this increase in solubility involves the formation of inclusion complexes between MCD molecules and dye molecules. The cyclic structure of MCD allows it to form a cavity that accommodates dye molecules, reducing their hydration energy and consequently increasing the solubility in PBS.

The investigation of the spectral patterns of chromophores in their complexes with MCD allowed us to determine еhe dissociation constants of dye or chalcone complexes with MCD to describe the stability of these guest-host inclusion complexes with the studied compounds; the values are of the order of 10–4-10–5 M, indicating to the relative strength of the complex and sufficient to increase the solubility of the bioactive substance and improve bioavailability, as well as to create combined unified delivery systems several components of drug + dye + adjuvant at once.

3.3. FTIR Spectroscopy of Dyes and Its Complexes with MCD

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy is a powerful analytical technique used to identify functional groups and molecular interactions in a variety of compounds, including dyes and the complexes with MCD. This technique provides information about the oscillations of molecular bonds, allowing for the analysis of molecular structures and the assessment of complex formation.

Figure 2 presents the FTIR spectra of the investigated dyes in free form in a buffer solution and complexed with MCD.

FTIR spectra of the dyes and compounds under investigation, such as chalcones and others, typically exhibit distinctive absorption peaks associated with specific functional groups, such as –CH2–, –NH–, –C=O, and aromatic C=C stretches. For example, peaks at 3000-2800 cm–1 correspond to ν(C-H), while peaks in the region of 1500-1600 cm⁻¹ often relate to aromatic C=C oscillation, 1150-1050 cm⁻¹ C-O stretching oscillation. MCD displays distinct peaks associated with its molecular structure, the most important 1150-1050 cm⁻¹ C-O-С stretching oscillation.

In the FTIR spectrum of a chalcone derivative 9 (

Figure 2a), prominent peaks can be found at 1650-1580 cm⁻¹ ν(C=C), 2210 cm

–1 ν(C-N nitrile), 1300-1250 cm⁻¹ ν(SO

3–). When chalcone 9 or sample 17 (

Figure 2ab) form complexes with MCD, the ν(C=C) around 1600 cm⁻¹ peak as well as other analytically significant peaks (for example, corresponding to the sulfogroup, ether bonds) exhibit decreased intensity, suggesting interaction with the cyclodextrin cavity. Additionally, a slight shift of the characteristic maxima towards the low-frequency range (from 1 to 5 cm⁻¹), for instance, in oscillations with aromatic C=C, can be employed as an additional marker of the formation of MCD complex with chalcones.

In the FTIR spectrum of a chromene derivative (17) (

Figure 2b), prominent peaks can be found at 1740-1720 ν(C=C in pyridinium), 1680-1580 cm⁻¹ ν(C=C in methoxychromene system), 2190 cm

–1 ν(C-N nitrile), 1060 cm⁻¹ ν(C–C) and 1280-1190 cm⁻¹ ν(CH

3SO

4–). Upon complexation of chromene derivative with MCD, the spectral features corresponding to the functional groups within the drug molecule undergo alterations due to the establishment of hydrogen bonding interactions or Van der Waals forces. In particular, a displacement of the O-H stretch band may suggest the formation of hydrogen bonds between the drug molecule and the MCD component. This is manifested in a reduction of the intensity of characteristic peaks of the compound upon its incorporation into the hydrophobic pocket of the MCD. Simultaneously, charged groups, such as C=N

+ or the counterion CH

3SO

4−, being highly polar, remain exposed to the aqueous environment rather than fully immersed within the MCD pocket. These groups engage in hydrogen bonding interactions due to their accessibility to water molecules. Consequently, there is a more pronounced decrease in the absorption peak at 1280–1190 cm⁻¹ associated with CH

3SO

4− compared to the rest of the molecular complex involving MCD.

FTIR spectra of other chalcones and its complexes with MCD are presented in Supplement (Figure S1). The inclusion of chalcones into the hydrophobic cavity of the MCD occurs mainly in the more hydrophobic part (ring), which is reflected in a decrease in the intensity of the corresponding peaks in the FTIR spectrum. For example, for chalcone 12, there is a decrease in the peak intensity of 1600-1550 cm–1, and an increase in the peak intensity at 1640 cm–1, which indicates the inclusion of a ring A with a benzodioxol “nose” into the hydrophobic cavity, and conversely, the orientation of the ring B with a methoxy and sulfogroup into the solvent.

It is known, that the main force of the guest-host complexation is the hydrophobic interactions of aromatic systems of bioactive substances and the hydrophobic structure of cyclodextrin (enthalpy factor), with simultaneous displacement of water (entropy factor) [

87,

88]. Dyes or fluorophores often contain functional oxygen- and/or nitrogen-containing (N) groups, which can participate in the formation of hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups of MCD, which further stabilizes the complex. This information is crucial for optimizing the use of these compounds in various applications, such as drug delivery and encapsulation of dyes. The use of FTIR in combination with other techniques, such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and UV-Vis spectroscopy, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the complex phenomenon under study.

3.4. ¹H NMR Spectroscopy of Chalcones and Its Complexes with Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin

1H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR) is a highly effective method for elucidating the structural features of organic molecules, as well as shedding light on the intricate mechanisms underlying drug interactions with molecular targets, such as chalcones complexed with MCD. The NMR spectra of chalcones are presented in

Figure 3, with a particular focus on compound 9.

Analysis of the chalcone spectrum (sample 9,

Figure 3a) reveals a number of characteristic features in its structure. Protons in the benzodioxole ring can resonate in the range from 6.7 to 7.4 ppm for the aromatic fragment and from 3 to 4 ppm for the oxol - fragment. Protons attached to the carbon atoms of the double bond give a signal at about 8.3 ppm. The methoxy groups give a signal in the range from 3.0 to 4.0 ppm. The spectrum of the MCD-chalcone complex (

Figure 3b) also contains signals from the CD. H1, H1’ protons give the lowest-field signals, observed at 5.25, 5.04 ppm. It is sensitive to the environment of the MCD molecule and may vary depending on the presence of a guest in the cavity. Protons H-2, H-3, H-4, H-5, H-6 give signals in the range of 3.2-4.1 ppm.

The proposed structure of the complex obtained during computer modeling is shown in

Figure 3c, it confirms the immersion of aromatic fragments of compound 9 (chalcone) into the hydrophobic layer of cyclodextrin. The hydrophobic aromatic core is submerged within the MCD, with the benzodioxyl «nose» protruding from the MCD’s surface, capable of engaging with a second MCD molecule akin to a lid. The sulfogroup, owing to its high polarity and charge, has directed into solution. During the complexation of chalcone with MCD, drug signals are shifted due to changes in the microenvironment of the aromatic molecule from the DMSO medium to the environment of the hydroxyl group MCD: for example, for protons of the aromatic ring, the shift occurs from 7.1-7.0 ppm to 7.3-7.2 ppm (due to a more hydrophobic microenvironment inside the MCD), and for methoxy groups, on the contrary, into a strong field (due to a more hydrophilic microenvironment, since these groups “stick out” from the aromatic systems in different directions and cannot avoid contact with the OH groups of MCD). This indicates the inclusion of the aromatic core of the drug molecule into the cyclodextrin cavity, the successful formation of the guest-host complex.

3.5. Antibacterial Activity of Substances

In our research, we explore the antibacterial capabilities of novel promising chemical compounds as «drug candidate» chalcones, chromene and stilbenoids, xanthylium derivatives, conducting comparative analysis with standart antibiotics. Of particular interest is the synergistic interaction between these novel compounds with metronidazole.

Table 4 provides information on the viability of

E. coli cells (%) and the synergistic coefficient with metronidazole for various compounds. High viability: Samples such as Chalcone derivative (8-14) (90% at 1 mM) and Congo Red (94% at 1 mM) demonstrate low efficacy as the antibacrterial agent. However, chalcones 9, 12, and 15 exhibit moderate antibacterial activity, with a survival rate of 75–80% of cells, owing to the presence of a benzodioxole moiety or a bromine atom functioning as a substituent for ring A. This benzodioxole fragment serves as a critical component in mediating the encapsulation of the antibacterial properties inherent in natural compounds like apiol as early was shown [

73]. Low viability of bacterial cells is achieved by the action of Benzalkonium chloride (5% at 1 mM) and Malachite Green (12% at 1 mM) on them, which indicates their high antibacterial activity. These substances can serve both for topical use and as an adjuvant to the main component – metronidazole.

The synergistic coefficient shows how many times the combo formulation is more active than single substances. The coefficient with metronidazole is an important indicator for creating a combined formulation for potentially overcoming drug resistance. The values of the synergistic coefficient (more than 1) indicate that the combination of the substance with metronidazole affects their effectiveness. For example, Chalcone (9) (benzodioxole apiol-like moiety) has a coefficient of 1.36, which indicates a synergistic effect. We have recently demonstrate that apiol show synergistic effect with antibiotics such as levofloxacin due to efflux inhibition [

73]. Rhodamine 6G, Benzalkonium chloride and Chlorhexidine also demonstrate high synergy with metronidazole (up to 1,95). Values below 1, such as Chalcone derivative 10 (0.9) and Ponceau 4R (0.95) indicate to a lack of synergy or antagonistic behavior.

Metronidazole showed the viability of E. coli cells at the level of 15% at 1 mM, indicating its pronounced antibacterial activity compared with most of the listed chalcone derivatives. Some other tested compounds, such as Congo Red and Sudan III, show high cell viability.

Thus, we have demonstrated a variety of antibacterial properties of the tested substances. Chalcone derivatives showed low to moderate efficacy, while agents such as Benzalkonium chloride, Chlorhexidine, dyes methylene blue, rhodamine 6G, malachite green, gentian violet had a strong suppressive effect on E. coli. The results of the synergistic analysis with metronidazole also confirm the effectiveness of these dyes, including for the further creation of complex formulations to improve antibacterial activity.

The most effective formulation involves the combination of a primary drug, such as metronidazole, with a dye or fluorophore, such as methylene blue or rhodamine 6G, for target cell visualization. Additionally, an adjuvant, such as chalcones, is used to inhibit efflux. These formulations demonstrate significant therapeutic potential, enabling simultaneous visualization of target cells and therapeutic action. In the creation of this combined formulation, CDs play a crucial role. MCD enhances the solubility and bioavailability of drugs, as well as augmenting their antibacterial effects. Furthermore, MCD enables the development of a unified system for delivering multiple components to target cells for both visualization and elimination purposes.

3.6. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant Activity

Antioxidants play a crucial role in preventing oxidative stress, a condition that can lead to cellular damage and the onset of various diseases. Their significance lies in their capacity to neutralize free radicals, which are unstable molecules responsible for oxidative stress.

Several methods exist for evaluating the antioxidant capacity of compounds:

The DPPH assay measures the ability of a substance to scavenge free radicals generated by DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl).

The ABTS (2,2’-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) assay assesses the capacity of antioxidants to quench ABTS radicals.

The oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay determines the protective effect against oxidative stress.

In our study, we employed the ABTS method to evaluate the antioxidant potential of the tested substances of different classes(

Figure 4).

Quercetin has been chosen as the benchmark, exhibiting remarkable antioxidant activity in a variety of tests. This activity is attributed to the presence of multiple hydroxyl groups, which enhances its capacity to neutralize free radicals. The antioxidant activity of various substances was evaluated by measuring the rate of ABTS radical neutralization, comparing it with the activity of quercetin, a well-known antioxidant.

It was found that dyes, such as rhodamine 6G, gentian violet and congo red, exhibit moderate antioxidant activity, approximately 50% and 25%, respectively, of quercetin activity at concentrations of 1 and 0.01 mg/mL. These substances are effective at concentrations, exceeding 50–100 µM. Among the compounds tested, xanthylium R351 derivatives demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity, comparable to quercetin. The most potent antioxidant was 1-methyl-3-(2-amino-3-cyano-7-methoxychromene-4-yl)-pyridinium me-thanesulfate (17), exhibiting high activity even at concentrations as low as 0.1 mg/mL due to its ability to readily interact with radicals. For chalcones 7–15, antioxidant activity is virtually nonexistent (

Figure 4b), with even an inverse correlation between activity and concentration observed, suggesting a non-specific mode of action.

The impact of cyclodextrin on the antioxidative potential of dyes is a critical aspect that is contingent upon a multitude of factors. MCD enhances the solubility of the dye in aqueous solutions, rendering it more susceptible to interaction with reactive species, thereby augmenting its antioxidative capacity. The formation of a complex with cyclodextrin alters the electronic distribution within the dye molecule, potentially affecting its microenvironment and influencing its capacity to scavenge free radicals. Furthermore, the spatial arrangement of the dye complexed with MCD, potentially enhancing its antioxidative properties. For instance, we observed that complexes of methylene blue with MCD exhibited a 15% improvement in antioxidative activity compared to free methylene blue, and up to a remarkable 20–25% increase for Xanthylium - R351 (

Table 1). So, here we identified several new compounds with moderate antioxidant activity. The pronounsed antioxidant properties of these substances are observed for Xanthylium derivative - R351 and 1-methyl-3-(2-amino-3-cyano-7-methoxychromene-4-yl)-pyridinium methanesulfate (sample 17). The charged groups conjugated to the condensed aromatic structures play an important role in enhancing antioxidant activity. These substances hold promise as potential antioxidants.

3.8. CLSM Visualization of Bacterial Cells Stained with Theranostic Formulation

CLSM (confocal laser scanning microscopy) used to visualize the penetration of a theranostic formulation containing rhodamine 6G (R6G) into

E. coli bacteria and

lactobacilli. Selective penetration into

E. coli cells is observed, which is confirmed by a more intense fluorescent signal in these cells compared to lactobacilli. Again, the rhodamine complex with cyclodextrin demonstrates significantly more effective staining of bacterial cells compared to free R6G (

Figure 5). These observations open up prospects for the use of this formulation as a theranostic agent for the visualization and therapy of bacterial infections. The results obtained can be used for 1) detection and localization of bacterial infection; selective penetration into

E. coli allows you to visualize infected areas without affecting other cells; 2) develop the targeted drug delivery system directly to bacterial cells.

The substances under consideration for biomedical applications will be employed in conjunction with an antibiotic such as metronidazole to facilitate the visualization of specific cells or tissues and address infections. The theranostic formulation antibiotics with rhodamine 6G and MCD can be or the development of new tools for the diagnosis and treatment of bacterial infections. Such formulations could find application, for instance, in the field of dentistry for diagnosing and treating bacterial infections, such as stomatitis, gingivitis, and the treatment of cysts.

3.8. Discussion of the Results and Its Biomedical Significance

The study of cyclodextrin (CD) as a molecular depot for bioactive compounds in theranostic applications is of great importance.

CD offers several key benefits:

Improved solubility for compounds such as chalcones, stilbenoids, dyes, and xanthylium derivatives, making them more bioavailable.

Enhanced bioavailability due to protection from degradation, which prolongs circulation and allows for higher concentrations in target tissues.

Unified delivery system for combining multiple active agents in a single system, opening up new possibilities for developing theranostic formulations.

Efficacy of antibacterial compounds by increasing their concentration at the site of infection.

Confocal microscopy has shown that CD improves the penetration of compounds into target bacterial cells, with high selectivity for E. coli compared to Lactobacilli. Fluorescent markers such as rhodamine allow visualization of the target cells.

Natural compounds like chalcones and stilbenoids may have additional effects:

Potential applications include treating bacterial infections such as skin infections and wounds, delivering antibiotics to bacterial colonies, and combining with anti-inflammatory drugs for anti-inflammatory therapy. Compared to other systems, CD systems allow targeted delivery of drugs to specific areas. Fluorescent markers make it easy to find the infection, chalcones and stilbenoids inhibit efflux, and the main antibiotic has an antibacterial effect. Additionally, new antioxidant compounds were found such as Xanthylium derivative - R351 and 1-methyl-3-(2-amino-3-cyano-7-methoxychromene-4-yl)-pyridinium methanesulfate: the pronounced antioxidant properties of these substances are observed comparable to quercetin in the efficiency. The charged groups conjugated to the condensed aromatic structures play an important role in enhancing antioxidant activity. These substances hold promise as potential antioxidants. and the activity of CD helps minimize the harmful effects of bacterial toxins and reactive oxygen species on the human body. We have presented new and well-known compounds with new properties that combine the drug with fluorophore/dyes and an efflux inhibitor, creating a promising theranostic formulation.

4. Conclusion

The development of theranostic agents that combine antibiotics with cyclodextrin-based auxiliaries holds great promise for revolutionizing drug delivery systems. These innovative compounds have the potential to improve treatment effectiveness, reduce adverse effects, offer a more targeted approach, and help fight antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Our goal was to create a formulation that can both diagnose and treat infections and inflammatory processes. In our search for antibacterial agents, we are exploring a wide range of bioactive substances, including chalcones, stilbenoids, and xanthylium derivatives. We are comparing these compounds to well-established antiseptic agents to uncover new properties and expand their potential applications.

To create combination products, we aim to optimize the composition by adding dyes/fluorophores, medications, and adjuvants. This research explores the use of cyclodextrin inclusion complexes as a versatile platform to enhance the delivery and bioactivity of various antimicrobial and antioxidant substances.

The study deeply examines the interaction between selected compounds and methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MCD) using spectroscopic techniques such as ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis), infrared (IR), and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR). The observed spectral shifts and variations in peak intensities provide strong evidence of the formation of inclusion complexes, indicating that compounds are effectively encapsulated within the hydrophobic cavity of MCD. For many compounds, this encapsulation exceeds 80%, which can enhance solubility by up to tenfold. This process can lead to improved bioavailability, stability, and tailored release profiles, as has been shown for other antibacterial medications.

The study also explores the antioxidant potential of compounds incorporated into MCD delivery systems, comparing them with well-known reference compounds such as quercetin. The research has identified several novel compounds with high antioxidant activity such as xanthylium derivatives, and chromen-derivative, 1-methyl-3-(2-amino-3-cyano-7-methoxychromene-4-yl)-pyridinium methanesulfate. For these compounds, the concentration of radical semi-elimination is an order of magnitude higher than that of quercetin, which is known as a good antioxidant. The presence of condensed aromatic frameworks also seems to increase antioxidant capacity.

Among the dyes, rhodamine 6G, gentian violet, and Congo Red exhibit moderate antioxidant properties, although their activity levels are an orders of magnitude lower than that of quercetin in concentration. However, they have remarkable potential due to their multifaceted nature, including the ability to visualize target cells.

Chalcones and several dyes can inhibit the efflux process in bacterial cells and bacterial dehydrogenase, enhancing the efficacy of the primary antibacterial compound, such as metronidazole. The observed synergistic interactions between certain compounds and traditional antibiotics, particularly when combined with metronidazole, emphasize the potential for synergistic therapy and the possibility of overcoming antibiotic resistance. For example, chalcone derivatives (7 and 9, which have methoxy and sulfogroups in the ring-B positions, respectively) and dyes, such as rhodamine 6G and methylene blue, have demonstrated a strong synergistic effect with metronidazole, indicating their potential to significantly enhance the effectiveness of antibiotics.

This research presents formulations of promising “drug candidates” with a molecular container (MCD) that, when combined, exhibit theranostic properties.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1. FTIR spectra of the investigated «drug candidates» in free form in a buffer solution and complexed with methyl-cyclodextrin (MCD): (a) chalcone 10; (b) chalcone 12; (c) chalcone 15. PBS (0.01M, pH 7.4). T = 37 °C.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.V.K. and I.D.Z.; methodology, I.D.Z., N.G.B., S.S.K., E.V.K.; formal analysis, I.D.Z., A.N.B., V.E.K., and S.S.K.; investigation, I.D.Z., S.S.K., N.G.B., and E.V.K.; data curation, I.D.Z. and E.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, I.D.Z.; writing—review and editing, E.V.K.; project supervision, E.V.K.; funding acquisition, E.V.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Russian Science Foundation, grant number 24-25-00104.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Cell lines were obtained from Lomonosov Moscow State University Depository of Live Systems Collection (Moscow, Russia).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the main text and in Supplement.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed using the following equipment from the program for the development of Moscow State University: FTIR microscope MICRAN-3, Jasco J-815 CD Spectrometer, and AFM microscope NTEGRA II.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Meng, Q.; Sun, Y.; Cong, H.; Hu, H.; Xu, F.J. An Overview of Chitosan and Its Application in Infectious Diseases. Drug Deliv. Transl. Res. 2021, 11, 1340–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azad, A.K.; Rajaram, M.V.S.; Schlesinger, L.S. Exploitation of the Macrophage Mannose Receptor (CD206) in Infectious Disease Diagnostics and Therapeutics. J. Cytol. Mol. Biol. 2014, 1, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porta, C.; Riboldi, E.; Totaro, M.G.; Strauss, L.; Sica, A.; Mantovani, A. Macrophages in Cancer and Infectious Diseases: The ‘good’ and the ‘Bad’. Immunotherapy 2011, 3, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, H.; He, W.; Jiao, W.; Xia, H.; Sun, L.; Wang, S.; Xiao, J.; Ou, X.; Zhao, Y.; Shen, A. Molecular Characterization of Multidrug-Resistant Tuberculosis against Levofloxacin, Moxifloxacin, Bedaquiline, Linezolid, Clofazimine, and Delamanid in Southwest of China. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deusenbery, C.; Wang, Y.; Shukla, A. Recent Innovations in Bacterial Infection Detection and Treatment. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 695–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalelkar, P.P.; Riddick, M.; García, A.J. Biomaterial-Based Antimicrobial Therapies for the Treatment of Bacterial Infections. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigangirova, N.A.; Lubeneс, N.L.; Zaitsev, A. V.; Pushkar, D.Y. Antibacterial Agents Reducing the Risk of Resistance Development. Klin. Mikrobiol. i Antimikrobn. Himioter. 2021, 23, 184–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Bambeke, F.; Balzi, E.; Tulkens, P.M. Antibiotic Efflux Pumps. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000, 60, 457–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Pang, T.; Wang, J.; Xiong, D.; Ma, L.; Li, B.; Li, Q.; Wakabayashi, S. Down-Regulation of P-Glycoprotein Expression by Sustained Intracellular Acidification in K562/Dox Cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 377, 441–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, G.L.; Kool, M.; Heijn, M.; De Haas, M.; Pijnenborg, A.C.L.M.; Wijnholds, J.; Van Helvoort, A.; De Jong, M.C.; Hooijberg, J.H.; Mol, C.A.A.M.; et al. Specific Detection of Multidrug Resistance Proteins MRP1, MRP2, MRP3, MRP5, MDR3 P-Glycoprotein with a Panel of Monoclonal Antibodies. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 5269–5277. [Google Scholar]

- Rau, S.; Autschbach, F.; Riedel, H.D.; Konig, J.; Kulaksiz, H.; Stiehl, A.; Riemann, J.F.; Rost, D. Expression of the Multidrug Resistance Proteins MRP2 and MRP3 in Human Cholangiocellular Carcinomas. Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 38, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redgrave, L.S.; Sutton, S.B.; Webber, M.A.; Piddock, L.J.V. Fluoroquinolone Resistance: Mechanisms, Impact on Bacteria, and Role in Evolutionary Success. Trends Microbiol. 2014, 22, 438–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, F.; Chu, S.; Bence, A.K.; Bailey, B.; Xue, X.; Erickson, P.A.; Montrose, M.H.; Beck, W.T.; Erickson, L.C. Quantitation of Doxorubicin Uptake, Efflux, and Modulation of Multidrug Resistance (MDR) in MDR Human Cancer Cells. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, D.P.; Lin, X.Y.; Huang, Y.F.; Zhang, X.F. Theranostics Aspects of Various Nanoparticles in Veterinary Medicine. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, M.; Ghosh, M.; Kumar, R.; Brar, B.; Surjith, K.P.; Lambe, U.P.; Ranjan, K.; Banerjee, S.; Prasad, G.; Kumar Khurana, S.; et al. The Importance of Nanomedicine in Prophylactic and Theranostic Intervention of Bacterial Zoonoses and Reverse Zoonoses in the Era of Microbial Resistance. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2021, 21, 3404–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.A.; Barthel, H.; Bengel, F.; Eiber, M.; Herrmann, K.; Schäfers, M. What Is Theranostics? J. Nucl. Med. 2023, 64, 669–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M.; Jamil, B. Nanotheranostics: Applications and Limitations; 2019; ISBN 9783030297688.

- Bhushan, A.; Gonsalves, A.; Menon, J.U. Current State of Breast Cancer Diagnosis, Treatment, and Theranostics. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranja, A.G.; Pathak, V.; Lammers, T.; Shi, Y. Tumor-Targeted Nanomedicines for Cancer Theranostics. Pharmacol. Res. 2017, 115, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, S.; Pradeep, A.; Jayakannan, M. Enzyme-Responsive Theranostic FRET Probe Based on l -Aspartic Amphiphilic Polyester Nanoassemblies for Intracellular Bioimaging in Cancer Cells. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 5245–5262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalash, R.S.; Lakshmanan, V.K.; Cho, C.S.; Park, I.K. Theranostics. Biomater. Nanoarchitectonics 2016, 197–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelkar, S.S.; Reineke, T.M. Theranostics: Combining Imaging and Therapy. Bioconjug. Chem. 2011, 22, 1879–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G.; Liu, B. Multifunctional AIEgens for Future Theranostics. Small 2016, 12, 6528–6535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yordanova, A.; Eppard, E.; Kürpig, S.; Bundschuh, R.A.; Schönberger, S.; Gonzalez-Carmona, M.; Feldmann, G.; Ahmadzadehfar, H.; Essler, M. Theranostics in Nuclear Medicine Practice. Onco. Targets. Ther. 2017, 10, 4821–4828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wong, S.T.C. Cancer Theranostics: An Introduction. Cancer Theranostics 2014, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K.; Bircher, A.J.; Figueiredo, V. Blue Dyes in Medicine - A Confusing Terminology. Contact Dermatitis 2006, 54, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Grafskaia, E.; Yu, Z.; Shen, N.; Fedina, E.; Masyutin, A.; Erokhina, M.; Lepoitevin, M.; Lazarev, V.; Zigangirova, N.; et al. Methylene Blue-Loaded NanoMOFs: Accumulation in Chlamydia Trachomatis Inclusions and Light/Dark Antibacterial Effects. ACS Infect. Dis. 2023, 9, 1558–1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nafisi, S.; Saboury, A.A.; Keramat, N.; Neault, J.F.; Tajmir-Riahi, H.A. Stability and Structural Features of DNA Intercalation with Ethidium Bromide, Acridine Orange and Methylene Blue. J. Mol. Struct. 2007, 827, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blessing, W.D.; Stolier, A.J.; Teng, S.C.; Bolton, J.S.; Fuhrman, G.M. A Comparison of Methylene Blue and Lymphazurin in Breast Cancer Sentinel Node Mapping. Am. J. Surg. 2002, 184, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Shuang, S.; Dong, C.; Pan, J. Study on the Interaction of Methylene Blue with Cyclodextrin Derivatives by Absorption and Fluorescence Spectroscopy. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2003, 59, 2935–2941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghahosseini, F.; Arbabi-Kalati, F.; Fashtami, L.A.; Djavid, G.E.; Fateh, M.; Beitollahi, J.M. Methylene Blue-mediated Photodynamic Therapy: A Possible Alternative Treatment for Oral Lichen Planus. Lasers Surg. Med. 2006, 38, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, S.; Hoskin, T.L.; Degnim, A.C. Safety and Technical Success of Methylene Blue Dye for Lymphatic Mapping in Breast Cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2008, 196, 228–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alosaimy, R.A.; Bin Helayel, H.; Ahad, M.A. Gentian Violet (GV) Ink Associated Reaction in a Case of Preloaded Descemet Membrane Endothelial Keratoplasty: Case Report. Am. J. Ophthalmol. Case Reports 2024, 34, 102056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maley, A.M.; Arbiser, J.L. Gentian Violet: A 19th Century Drug Re-emerges in the 21st Century. Exp. Dermatol. 2013, 22, 775–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaedi, M.K.; Lone, O.; Nejad, H.R.; Das, R.; Owyeung, R.E.; Del-Rio-Ruiz, R.; Sonkusale, S. Soft Injectable Sutures for Dose-Controlled and Continuous Drug Delivery. Macromol. Biosci. 2024, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoenke, S.; Serbian, I.; Deigner, H.-P.; Csuk, R. Mitocanic Di- and Triterpenoid Rhodamine B Conjugates. Molecules 2020, 25, 5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Wang, Z.; Chen, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Peng, X.; Yoon, J. Construction of Rhodamine-Based AIE Photosensitizer Hydrogel with Clinical Potential for Selective Ablation of Drug-Resistant Gram-Positive Bacteria In Vivo. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Custódio, B.; Carneiro, P.; Marques, J.; Leiro, V.; Valentim, A.M.; Sousa, M.; Santos, S.D.; Bessa, J.; Pêgo, A.P. Biological Response Following the Systemic Injection of PEG–PAMAM–Rhodamine Conjugates in Zebrafish. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaubey, P.; Mishra, B.; Mudavath, S.L.; Patel, R.R.; Chaurasia, S.; Sundar, S.; Suvarna, V.; Monteiro, M. Mannose-Conjugated Curcumin-Chitosan Nanoparticles: Efficacy and Toxicity Assessments against Leishmania Donovani. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 111, 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, C.; Moriwaki, C.; Claudia, A.; Sato, F.; Luciano, M.; Medina, A.; Matioli, G. Curcumin – b -Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complex : Stability, Solubility, Characterisation by FT-IR, FT-Raman, X-Ray Diffraction and Photoacoustic Spectroscopy, and Food Application. FOOD Chem. 2014, 153, 361–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.H.N.; Hiebner, D.W.; Fulaz, S.; Vitale, S.; Quinn, L.; Casey, E. Synthesis and Self-Assembly of Curcumin-Modified Amphiphilic Polymeric Micelles with Antibacterial Activity. J. Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, A.; Kasoju, N.; Goswami, P.; Bora, U. Encapsulation of Curcumin in Pluronic Block Copolymer Micelles for Drug Delivery Applications. J. Biomater. Appl. 2011, 25, 619–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhat, P.A.; Chat, O.A.; Dar, A.A. Exploiting Co-Solubilization of Warfarin, Curcumin, and Rhodamine B for Modulation of Energy Transfer: A Micelle FRET On/Off Switch. ChemPhysChem 2016, 2360–2372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, D.; Xiao, L.; Qin, W.; Loy, D.A.; Wu, Z.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Q. Preparation, Characterization and Antioxidant Properties of Curcumin Encapsulated Chitosan/Lignosulfonate Micelles. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 281, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Guerra, J.; Palomar-Pardavé, M.; Romero-Romo, M.; Corona-Avendaño, S.; Guzmán-Hernández, D.; Rojas-Hernández, A.; Ramírez-Silva, M.T. On the Curcumin and Β-Cyclodextrin Interaction in Aqueous Media. Spectrophotometric and Electrochemical Study. ChemElectroChem 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyles, M.B.; Cameron, I.L. Interactions of the DNA Intercalator Acridine Orange, with Itself, with Caffeine, and with Double Stranded DNA. Biophys. Chem. 2002, 96, 53–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Malashkeevich, S.M.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E. V. Thermoreversible Gels Based on Chitosan Copolymers as “Intelligent” Drug Delivery System with Prolonged Action for Intramuscular Injection. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zelikin, A.N.; Trukhanova, E.S.; Putnam, D.; Izumrudov, V.A.; Litmanovich, A.A. Competitive Reactions in Solutions of Poly-L-Histidine, Calf Thymus DNA, and Synthetic Polyanions: Determining the Binding Constants of Polyelectrolytes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 13693–13699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muniz, D.F.; dos Santos Barbosa, C.R.; de Menezes, I.R.A.; de Sousa, E.O.; Pereira, R.L.S.; Júnior, J.T.C.; Pereira, P.S.; de Matos, Y.M.L.S.; da Costa, R.H.S.; de Morais Oliveira-Tintino, C.D.; et al. In Vitro and in Silico Inhibitory Effects of Synthetic and Natural Eugenol Derivatives against the NorA Efflux Pump in Staphylococcus Aureus. Food Chem. 2021, 337, 127776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihmels, H.; Otto, D. Intercalation of Organic Dye Molecules into Double-Stranded DNA - General Principles and Recent Developments. Top. Curr. Chem. 2005, 258, 161–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonovich, T.M. Sudan Dyes: Are They Dangerous for Human Health. Drug Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 36, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Gao, H.W.; Ren, J.R.; Chen, L.; Li, Y.C.; Zhao, J.F.; Zhao, H.P.; Yuan, Y. Binding of Sudan II and IV to Lecithin Liposomes and E. Coli Membranes: Insights into the Toxicity of Hydrophobic Azo Dyes. BMC Struct. Biol. 2007, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardizzone, A.; Kurhuzenkau, S.; Illa-Tuset, S.; Faraudo, J.; Bondar, M.; Hagan, D.; Van Stryland, E.W.; Painelli, A.; Sissa, C.; Feiner, N.; et al. Nanostructuring Lipophilic Dyes in Water Using Stable Vesicles, Quatsomes, as Scaffolds and Their Use as Probes for Bioimaging. Small 2018, 14, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, L.D.; Rawle, R.J.; Boxer, S.G. Choose Your Label Wisely: Water-Soluble Fluorophores Often Interact with Lipid Bilayers. PLoS One 2014, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sritharan, S.; Sivalingam, N. A Comprehensive Review on Time-Tested Anticancer Drug Doxorubicin. Life Sci. 2021, 278, 119527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalyanaraman, B. Oxidative Chemistry of Fluorescent Dyes: Implications in the Detection of Reactive Oxygen and Nitrogen Species. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011, 39, 1221–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gear, A.R. Rhodamine 6G: A Potent Inhibitor of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 1978, 249, 3628–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Wang, H.; Gao, F.B.; Li, M.; Yang, H.; Wang, B.; Tai, P.C. Fluorescein Analogues Inhibit SecA ATPase: The First Sub-Micromolar Inhibitor of Bacterial Protein Translocation. ChemMedChem 2012, 7, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaw, D.L.; Bryan, J.N. Photodynamic Therapy. Cancer Manag. Small Anim. Pract. 2009, 90, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsher, D.W. Cancer Revoked: Oncogenes as Therapeutic Targets. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, A.G.; Grumezescu, A.M. Photodynamic Therapy—an up-to-Date Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozharitskaya, O.N.; Shikov, A.N.; Obluchinskaya, E.D.; Vuorela, H. The Pharmacokinetics of Fucoidan after Topical Application to Rats. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michalkova, R.; Mirossay, L.; Gazdova, M.; Kello, M.; Mojzis, J. Molecular Mechanisms of Antiproliferative Effects of Natural Chalcones. Cancers (Basel). 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhalifa, D.; Al-Hashimi, I.; Al Moustafa, A.E.; Khalil, A. A Comprehensive Review on the Antiviral Activities of Chalcones. J. Drug Target. 2021, 29, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Luca, D.; Lauritano, C. In Silico Identification of Type III PKS Chalcone and Stilbene Synthase Homologs in Marine Photosynthetic Organisms. Biology (Basel). 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellewell, L.; Bhakta, S. Chalcones, Stilbenes and Ketones Have Anti-Infective Properties via Inhibition of Bacterial Drug-Efflux and Consequential Synergism with Antimicrobial Agents. Access Microbiol. 2020, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vontzalidou, A.; Dimitrakoudi, S.M.; Tsoukalas, K.; Zoidis, G.; Chaita, E.; Dina, E.; Cheimonidi, C.; Trougakos, I.P.; Lambrinidis, G.; Skaltsounis, A.L.; et al. Development of Stilbenoid and Chalconoid Analogues as Potent Tyrosinase Modulators and Antioxidant Agents. Antioxidants 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Jin, L.; Liu, H.; Hua, Z. Stilbenes: A Promising Small Molecule Modulator for Epigenetic Regulation in Human Diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, M.K.; Dhakad, G.K.; Shivani; Arora, S.; Bhagat, S.; Arora, T.; Kumar, R. Synthetic Strategies and Pharmacological Activities of Chromene and Its Derivatives: An Overview. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1263, 133012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista, J.M.; Lopes, A.A.; Ambrósio, D.L.; Regasini, L.O.; Kato, M.J.; Bolzani, V.D.S.; Cicarelli, R.M.B.; Furlan, M. Natural Chromenes and Chromene Derivatives as Potential Anti-Trypanosomal Agents. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2008, 31, 538–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejashri, G.; Amrita, B.; Darshana, J. Cyclodextrin Based Nanosponges for Pharmaceutical Use: A Review. Acta Pharm. 2013, 63, 335–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Belogurova, N.G.; Krylov, S.S.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V.; Kudryashova, E. V. Plant Alkylbenzenes and Terpenoids in the Form of Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes as Antibacterial Agents and Levofloxacin Synergists. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Valle, E.M.M. Cyclodextrins and Their Uses: A Review. Process Biochem. 2004, 39, 1033–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Jarho, P.; Másson, M.; Järvinen, T. Cyclodextrins in Drug Delivery System. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2005, 2, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kemary, M.; Sobhy, S.; El-Daly, S.; Abdel-Shafi, A. Inclusion of Paracetamol into β-Cyclodextrin Nanocavities in Solution and in the Solid State. Spectrochim. Acta - Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2011, 79, 1904–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfoury, M.; Auezova, L.; Greige-Gerges, H.; Ruellan, S.; Fourmentin, S. Cyclodextrin, an Efficient Tool for Trans-Anethole Encapsulation: Chromatographic, Spectroscopic, Thermal and Structural Studies. Food Chem. 2014, 164, 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milcovich, G.; Antunes, F.E.; Grassi, M.; Asaro, F. Stabilization of Unilamellar Catanionic Vesicles Induced by β-Cyclodextrins: A Strategy for a Tunable Drug Delivery Depot. Int. J. Pharm. 2018, 548, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barman, S.; Barman, B.K.; Roy, M.N. Preparation, Characterization and Binding Behaviors of Host-Guest Inclusion Complexes of Metoclopramide Hydrochloride with α- and β-Cyclodextrin Molecules. J. Mol. Struct. 2018, 1155, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernyshova, N.B.; Tsyganov, D. V.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Raihstat, M.M.; Konyushkin, L.D.; Semenov, R. V.; Semenova, M.N.; Semenov, V. V. Synthesis and Antimitotic Properties of Ortho-Substituted Polymethoxydiarylazolopyrimidines. Arkivoc 2017, 2017, 151–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varakutin, A.E.; Muravsky, E.A.; Tsyganov, D. V.; Shinkarev, I.Y.; Samigullina, A.I.; Kuptsova, T.S.; Chuprov-Netochin, R.N.; Smirnova, A. V.; Khomutov, A.A.; Leonov, S. V.; et al. Synthesis of Chalcones with Methylenedioxypolymethoxy Fragments Based on Plant Metabolites and Study of Their Antiproliferative Properties. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2023, 72, 1632–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlotnikov, I.D.; Dobryakova, N. V.; Ezhov, A.A.; Kudryashova, E. V. Achievement of the Selectivity of Cytotoxic Agents against Cancer Cells by Creation of Combined Formulation with Terpenoid Adjuvants as Prospects to Overcome Multidrug Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dawidowicz, A.L.; Olszowy, M. Does Antioxidant Properties of the Main Component of Essential Oil Reflect Its Antioxidant Properties? The Comparison of Antioxidant Properties of Essential Oils and Their Main Components. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014, 28, 1952–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilyasov, I.R.; Beloborodov, V.L.; Selivanova, I.A.; Terekhov, R.P. ABTS/PP Decolorization Assay of Antioxidant Capacity Reaction Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruijn, W.J.C.; Araya-Cloutier, C.; Bijlsma, J.; de Swart, A.; Sanders, M.G.; de Waard, P.; Gruppen, H.; Vincken, J.-P. Antibacterial Prenylated Stilbenoids from Peanut (Arachis Hypogaea). Phytochem. Lett. 2018, 28, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snow Setzer, M.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Setzer, W. The Search for Herbal Antibiotics: An In-Silico Investigation of Antibacterial Phytochemicals. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.E.I.; Guo, Q. The Driving Forces in the Inclusion Complexation of Cyclodextrins. 2002, 1–14.

- Zarzycki, P.K.; Lamparczyk, H. The Equilibrium Constant of β-Cyclodextrin-Phenolphtalein Complex; Influence of Temperature and Tetrahydrofuran Addition. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 1998, 18, 165–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).