Submitted:

02 November 2024

Posted:

08 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

This study explores the intersection of bioinformatics, computational biology, and biomathematics, focusing on how mathematical models are applied to analyze biological data and develop computational tools. This study highlights the foundational role of biomathematics in biological research including genomics, proteomics, and systems biology. Key areas of focus include the use of statistical models, algorithms, and simulations to create computational tools to aid in data interpretation and drug discovery. Additionally, this paper delves into emerging trends such as artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data in bioinformatics. By analyzing case studies and real-world applications, this study underscores the significance of biomathematics in advancing biological sciences and the potential for future innovations in personalized medicine and interdisciplinary approaches.

Keywords:

Contents

Introduction

Background

Biomathematics

Research Statement

Objectives and Research Questions

- To understand the fundamental role of biomathematics in bioinformatics and computational biology.

- To explore how mathematical models are employed in the analysis of biological data.

- To evaluate the impact of computational tools underpinned by biomathematics in modern biological research.

- How do biomathematics contribute to the analysis of large-scale biological data such as genomic and proteomic datasets?

- What are the key mathematical models used in bioinformatics and how do they enhance the development of computational tools?

- How have integrated biomathematics and bioinformatics advanced our understanding of biological systems and contributed to scientific discoveries?

Bioinformatics and Computational Biology: Foundations and Applications

Bioinformatics: Definition and Significance

Computational Biology: Definition and Applications

Biomathematics in Bioinformatics: Supporting Biological Research

Real-World Applications: Genomics, Proteomics, and Beyond

The Role of Biomathematics in Biological Data Analysis

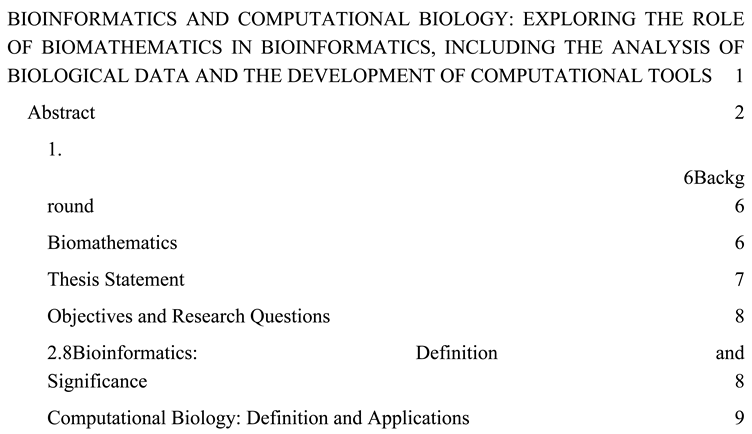

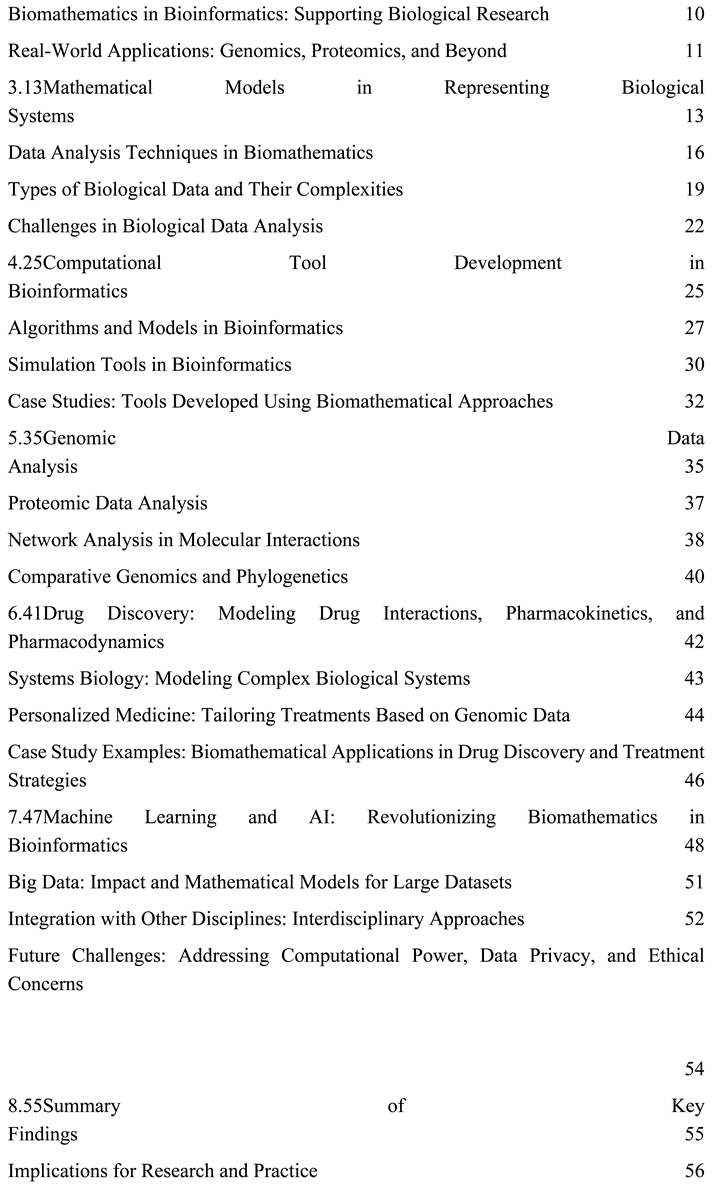

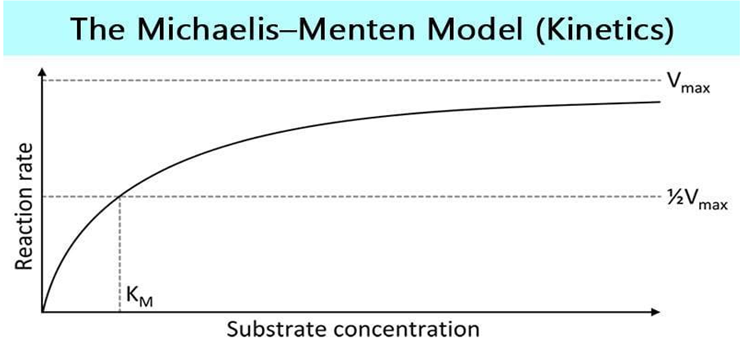

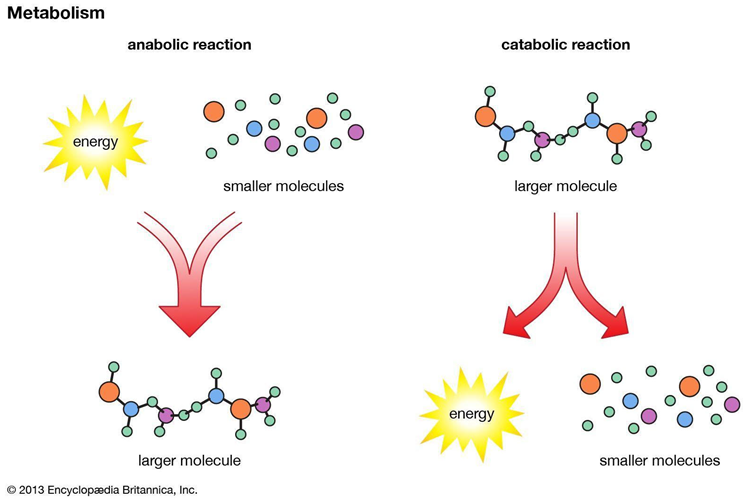

Mathematical Models in Representing Biological Systems

Data Analysis Techniques in Biomathematics

Types of Biological Data and Their Complexities

Challenges in Biological Data Analysis

Development of Computational Tools Using Biomathematics

Computational Tool Development in Bioinformatics

- Problem Definition: The first step in developing a computational tool is to clearly define the biological problem it aims to solve. For example, a tool may be needed to identify homologous sequences in DNA, predict protein structures, or analyze gene expression patterns (Athar et al., 2024). The problem must be articulated with precision, outlining the specific biological data to be handled and the desired outcome of the analysis.

- Data collection and preparation: Computational tools often require large amounts of biological data for effective functioning. The data must be collected from reliable sources, such as genomic databases (e.g., GenBank or Ensembl), and properly formatted for input into the tool (Matellio, 2024). This stage often involves data cleaning, annotation, and normalization to ensure that the data are consistent and ready for analysis.

- Algorithm Design: The core of any bioinformatics tool is the algorithm that processes biological data and provides meaningful results. An algorithm must be chosen or designed based on this problem. For example, sequence alignment tools rely on dynamic programming algorithms to efficiently compare sequences (Clark and Lillard, 2024). Biomathematics heavily influences algorithm design because mathematical models often underpin the logic of these algorithms.

- Software Development: Once the algorithm is defined, the next step is to implement it in software. This involves writing code in programming languages such as Python, R, or C++, and creating an interface that allows users to interact with the tool. User experience is a critical factor, as bioinformatics tools are used by biologists who may need a deeper understanding of the underlying algorithms (Pereira et al., 2020). The software must be intuitive and accessible, while still providing powerful analytical capabilities.

- Testing and Validation: Before computational tool is released for public use, it must be rigorously tested. Testing involved running the tool on known datasets to ensure accurate and reliable results. The performance of the tool was also benchmarked against other tools to assess its speed, accuracy, and scalability (Pereira et al., 2020). The validation ensures that the tool provides meaningful insights into real-world biological research.

- Distribution and Maintenance: Once tool is fully developed, it must be available to the scientific community. Many bioinformatics tools are distributed as open-source software, allowing researchers to freely use and modify them (Pereira et al., 2020). However, developers must continue to maintain and update software to accommodate new data types, fix bugs, and improve performance over time.

Algorithms and Models in Bioinformatics

- a)

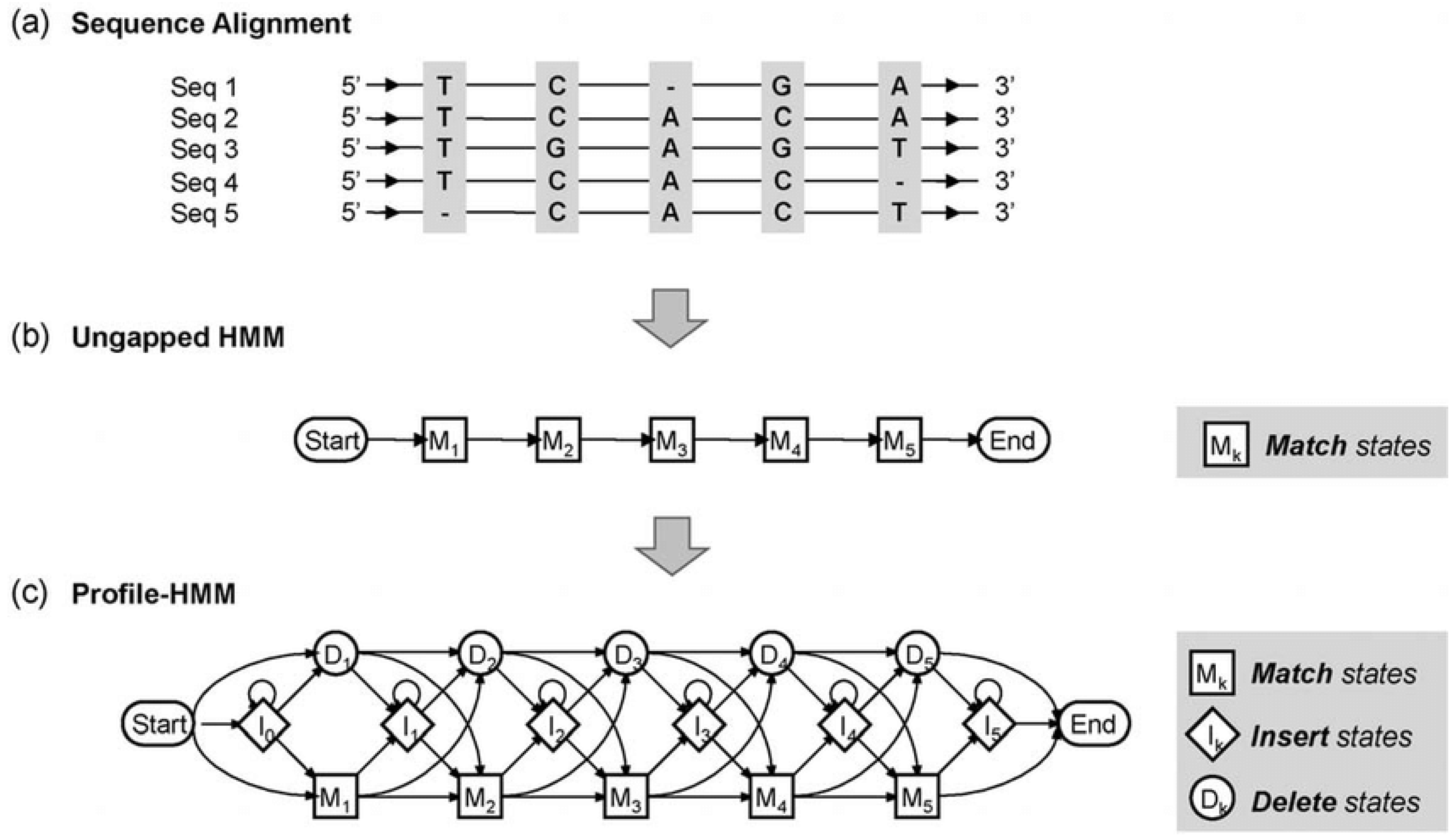

- Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): HMMs are widely used in bioinformatics, particularly for sequence alignment and gene prediction. They are probabilistic models that describe systems with hidden states, such as the underlying structure of a protein or evolutionary relationships between DNA sequences. In sequence alignment, HMMs are used to model the probabilities of transitions between different sequence motifs, allowing the detection of conserved regions across genomes (Yoon, 2009). The biomathematical foundation of HMMs is based on the probability theory, where each state transition is governed by a set of probabilities.Figure 4. Profile of hidden Markov model. (a) Multiple sequence alignment for constructing profile-HMM. (b) The ungapped HMM represents the consensus sequence of alignment. (c) Final profile of HMM that allows insertions and deletions.Figure 4. Profile of hidden Markov model. (a) Multiple sequence alignment for constructing profile-HMM. (b) The ungapped HMM represents the consensus sequence of alignment. (c) Final profile of HMM that allows insertions and deletions.

- b)

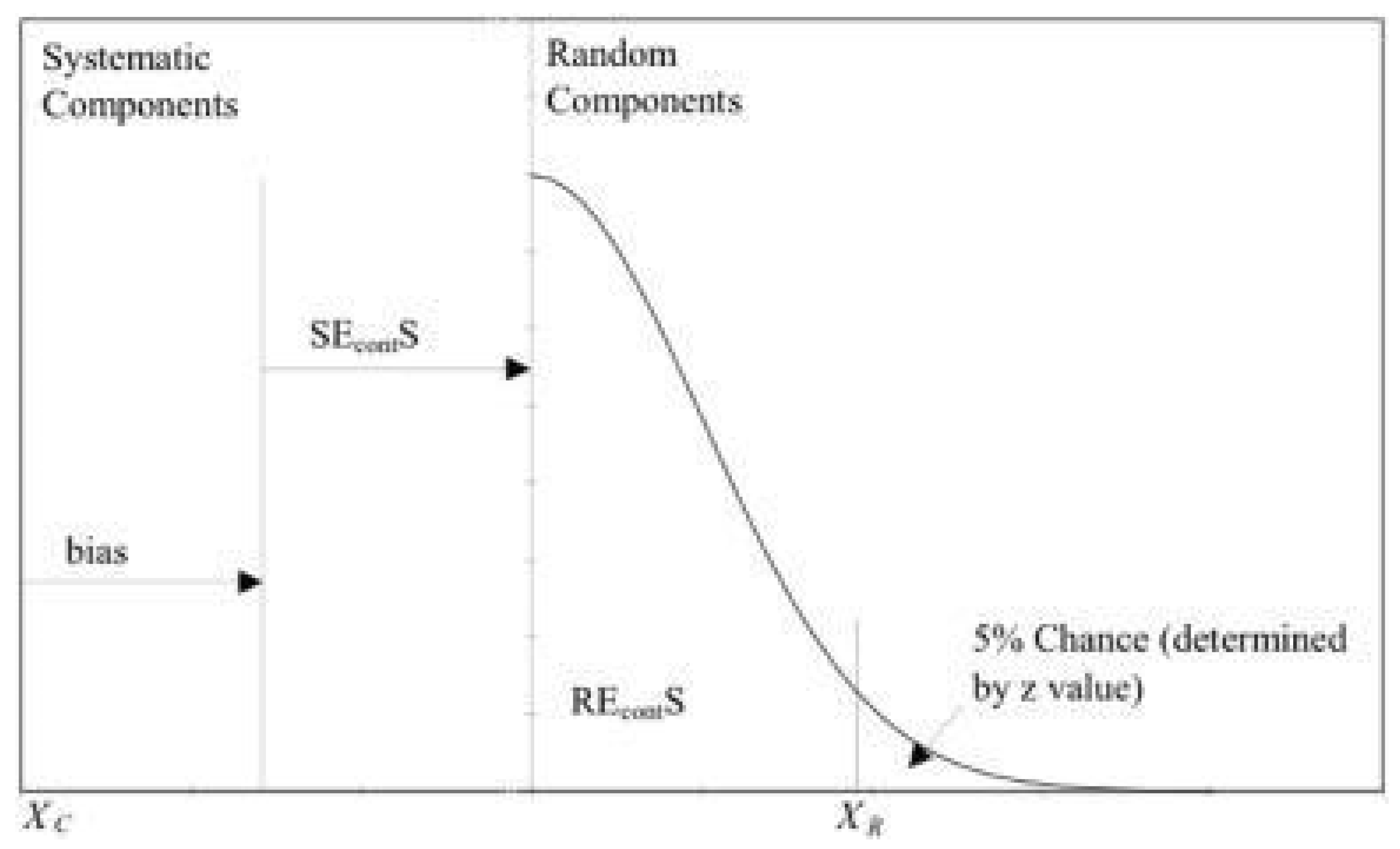

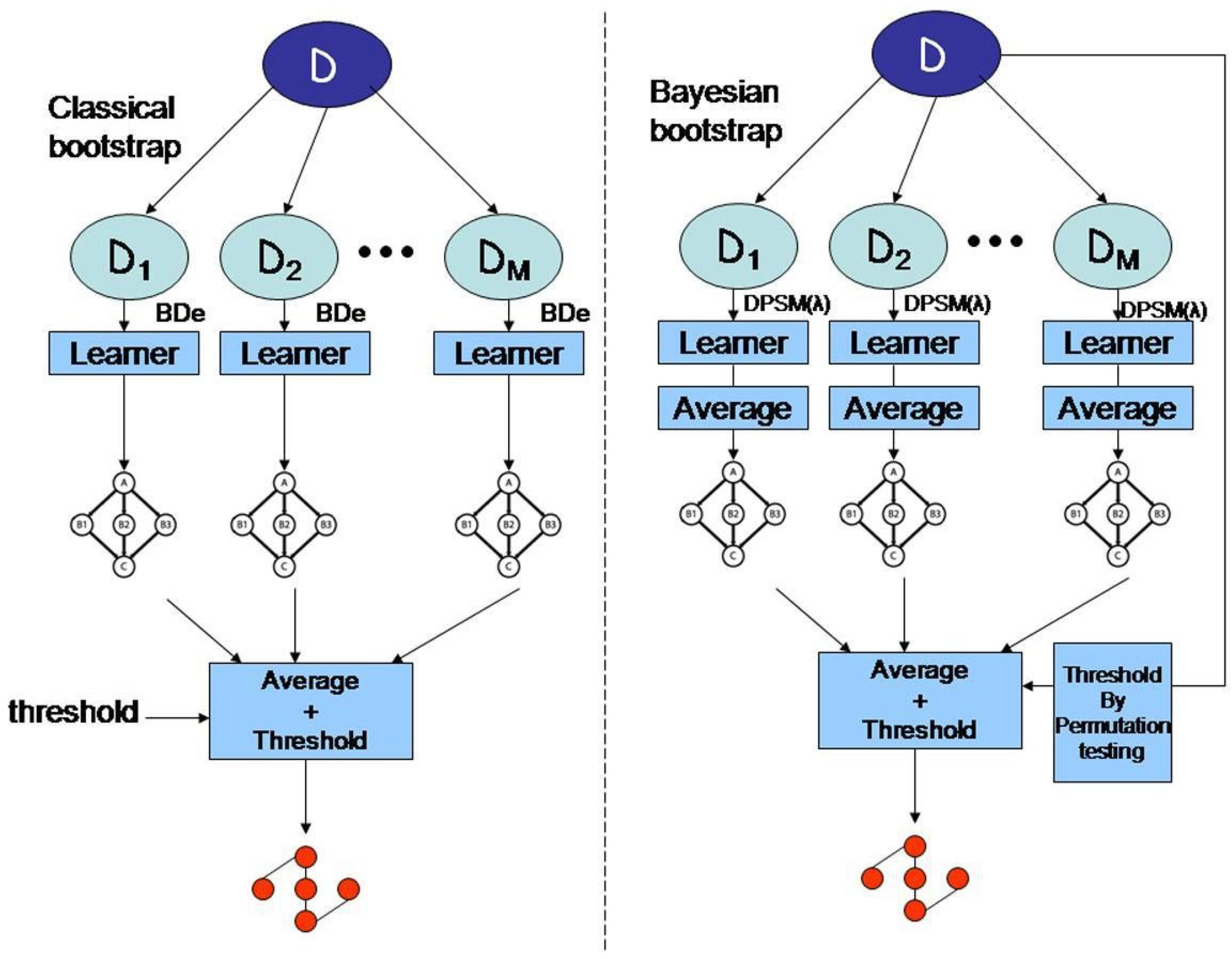

- Bayesian Methods: Bayesian inference is another essential mathematical technique used in bioinformatics for phylogenetic analysis, gene expression profiling, and population genetics. Bayesian methods rely on Bayes’ theorem to update the probability of a hypothesis based on new data (Dey et al. 2010). This approach is beneficial for biological research in which uncertainty is inherent in the data. Bayesian models allow researchers to incorporate prior knowledge and uncertainty into their analyses, thus making them highly flexible and robust.Figure 5. Model averaging strategies for structure learning in Bayesian networks with limited data.

- c)

- Dynamic Programming: Dynamic programming algorithms, such as the Needleman-Wunsch and Smith-Waterman algorithms, are fundamental to sequence alignment tools. These algorithms break down complex problems into smaller subproblems and solve them recursively. This approach is highly efficient in aligning large DNA or protein sequences and identifying homologous regions across genomes (Doerr et al. 2011). Dynamic programming is grounded in biomathematics, particularly in optimizing biological functions, where the goal is to find the best alignment or match between sequences.Figure 6. Dynamic Programming.

Simulation Tools in Bioinformatics

- I.

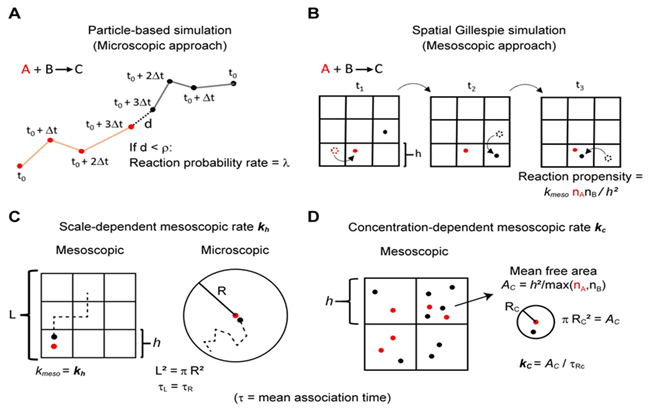

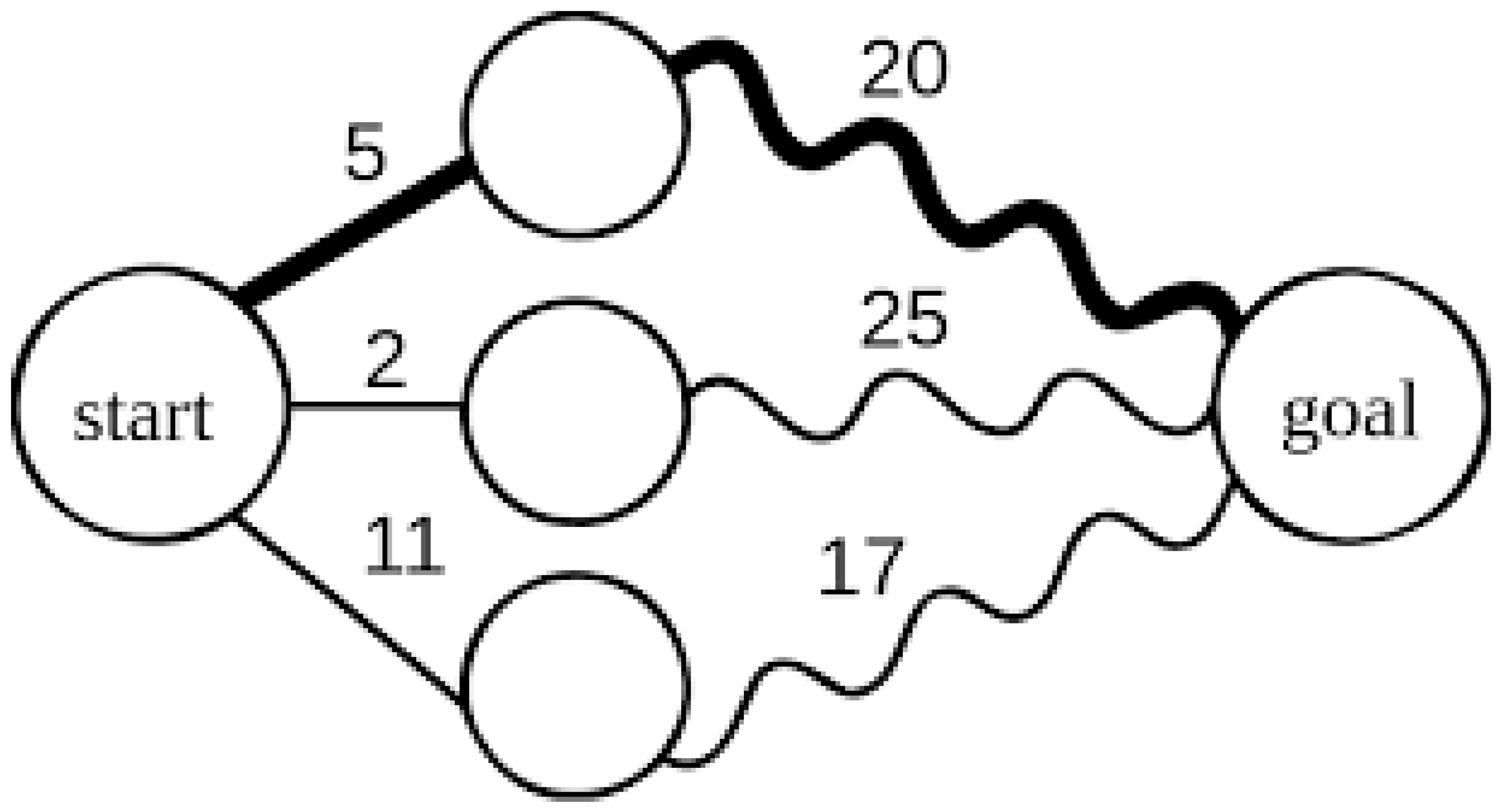

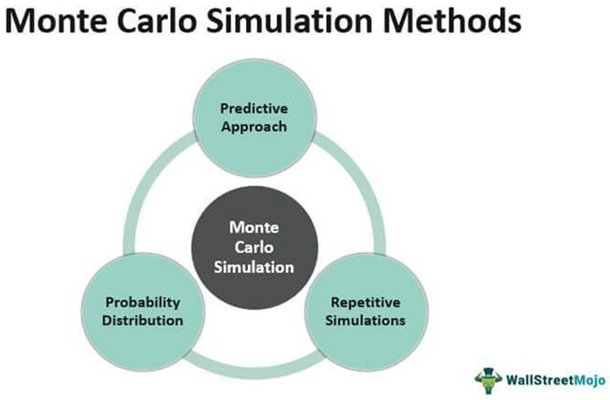

- Monte Carlo Methods: Monte Carlo simulations are widely used in bioinformatics to model complex stochastic processes. These methods rely on random sampling to explore possible outcomes of biological systems. For example, Monte Carlo simulations can be used to model protein folding, in which the energy landscape of a protein is explored through random conformational changes (Giró et al., 1986). These simulations provide insights into the most likely structures that a protein can adopt based on its amino acid sequence. Monte Carlo methods are grounded in probability theory and are particularly useful when dealing with high-dimensional biological data.

- II.

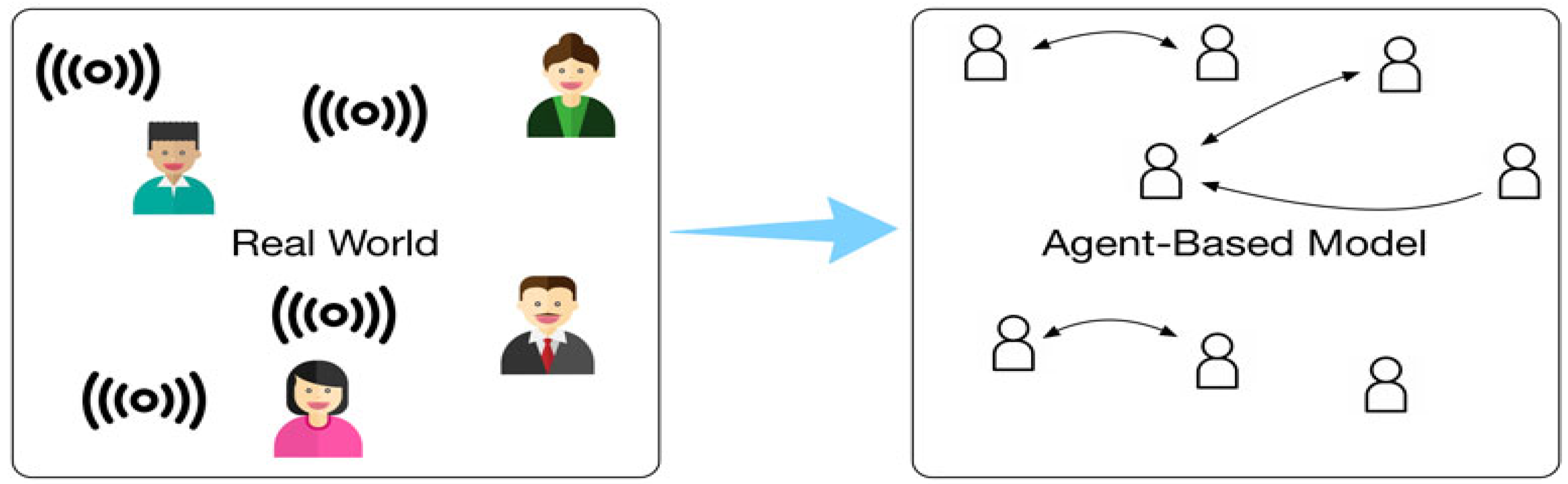

- Agent-Based Modeling: In agent-based models, individual biological entities (e.g., cells, molecules, and organisms) are modeled as agents with specific behaviors. These agents interact with each other and with their environment, leading to emergent phenomena. Agent-based models are commonly used in systems biology to simulate complex interactions in biological systems, such as tumor growth and immune responses (Breitwieser et al., 2022). The biomathematical foundation of agent-based models lies in systems theory and differential equations, which describe the interactions between agents over time.Figure 7. Data-driven Agent-based Simulation.

- III.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: MD simulations were used to model the physical movements of the atoms and molecules over time. These simulations are particularly useful for studying protein dynamics and drug and molecular interactions. MD simulations rely on principles of physics and biomathematics, such as Newton’s laws of motion, to calculate the trajectories of individual atoms in a biological system (Oyewusi et al., 2024). By simulating molecular motion, researchers can gain insights into the structural stability and function of biological macromolecules.

Case Studies: Tools Developed Using Biomathematical Approaches

- i.

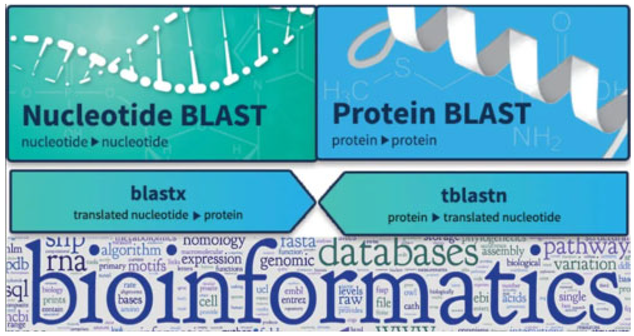

- BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) is one of the most widely used bioinformatics tools for comparing nucleotide or protein sequences to sequence databases. It uses a heuristic algorithm to quickly identify regions of similarity between sequences (Samal et al., 2021). The biomathematical foundation of BLAST is based on dynamic programming and probabilistic models, which enables the tool to identify homologous sequences with high accuracy. BLAST has revolutionized the field of genomics by allowing researchers to annotate genes, identify conserved sequences, and study evolutionary relationships across species.

- ii.

- FASTA (Fast Alignment Search Tool): Like BLAST, FASTA is used for sequence alignment and searching databases for similar sequences. The FASTA algorithm uses heuristic methods and dynamic programming to align sequences efficiently (Alok & Shrivastava, 2022). The mathematical models used in FASTA allow it to handle large-scale genomic datasets and provide accurate alignments, making it a cornerstone of bioinformatic research.

- iii.

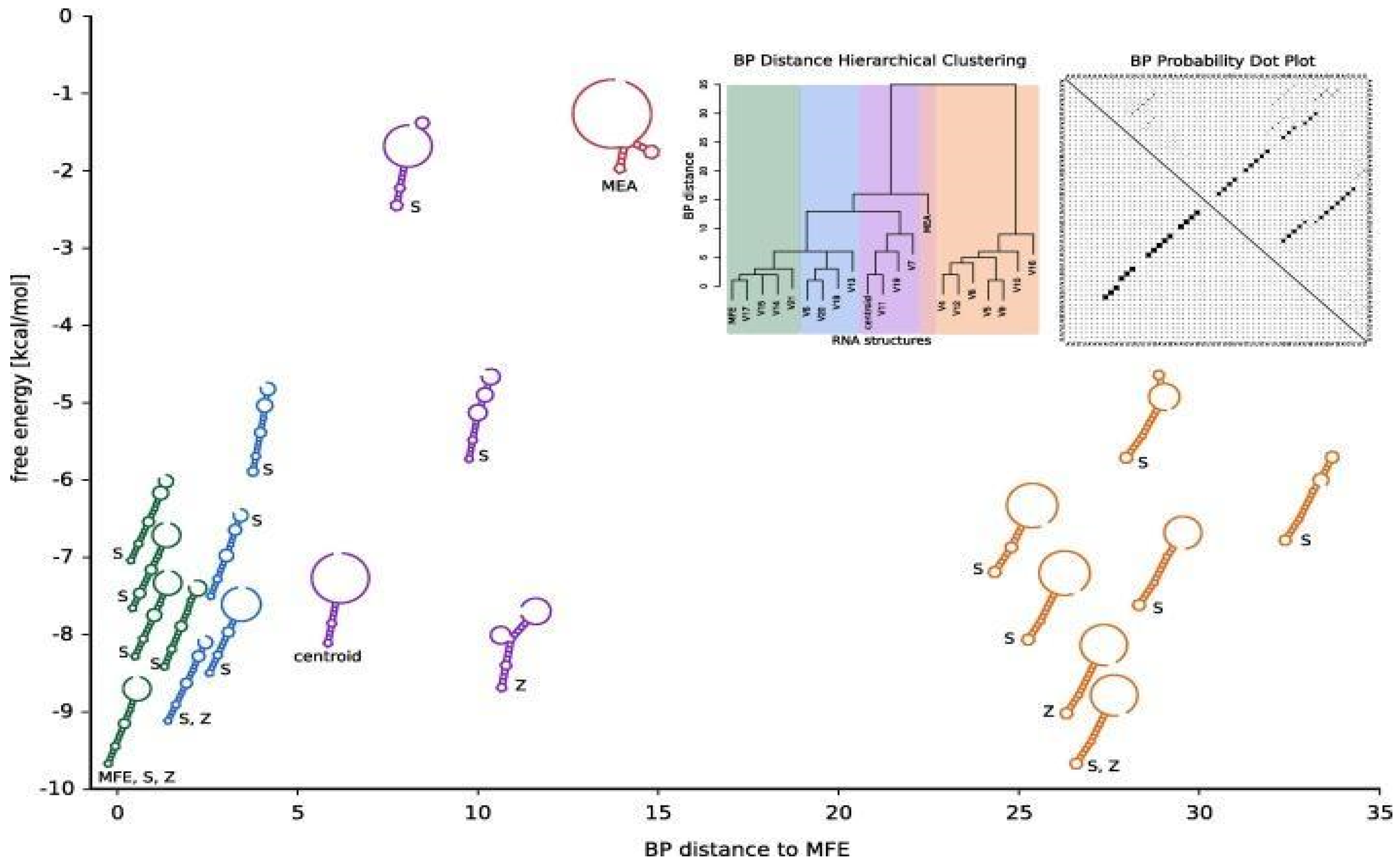

- RNA structure prediction tools: MFold and RNAfold use biomathematical approaches to predict the secondary structure of RNA molecules. These tools rely on dynamic programming algorithms and thermodynamic models to predict the most stable RNA structures based on nucleotide sequences (Afanasyeva et al., 2019). The biomathematical foundation of RNA structure prediction tools is based on statistical mechanics and thermodynamics, which allows researchers to model the folding process of RNA molecules and predict their functional structures.Figure 8. Predicting RNA secondary structures from sequence and probing data.

Biomathematics in Genomics and Proteomics

Genomic Data Analysis

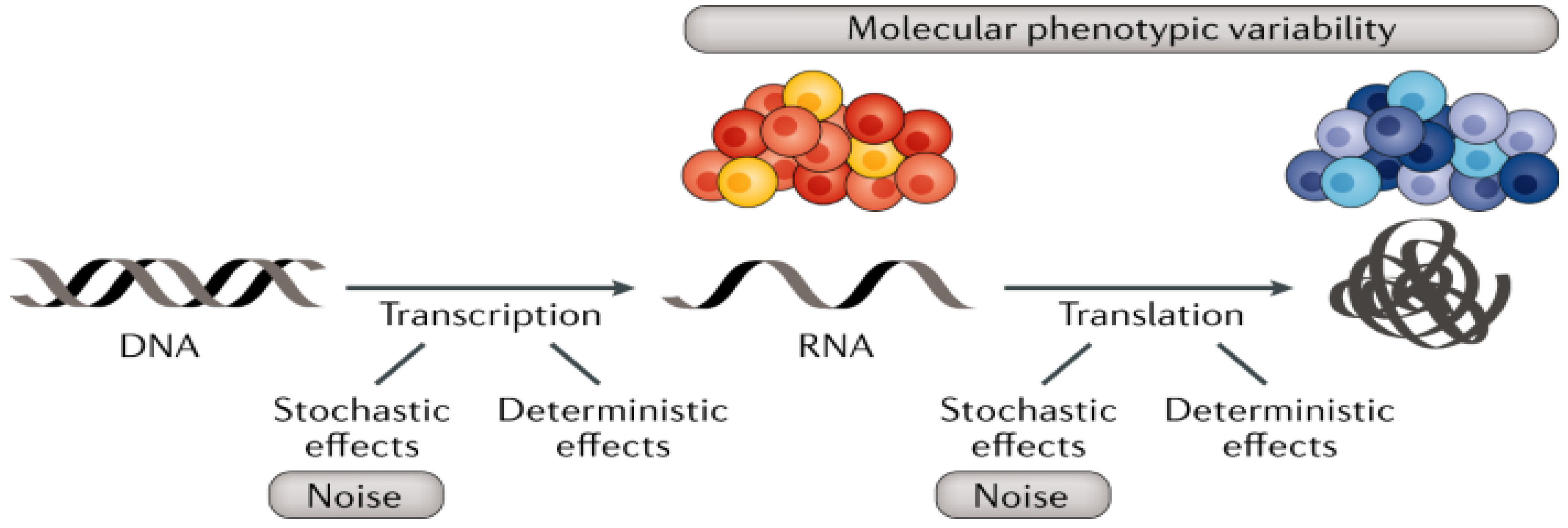

Gene Expression and Differential Analysis

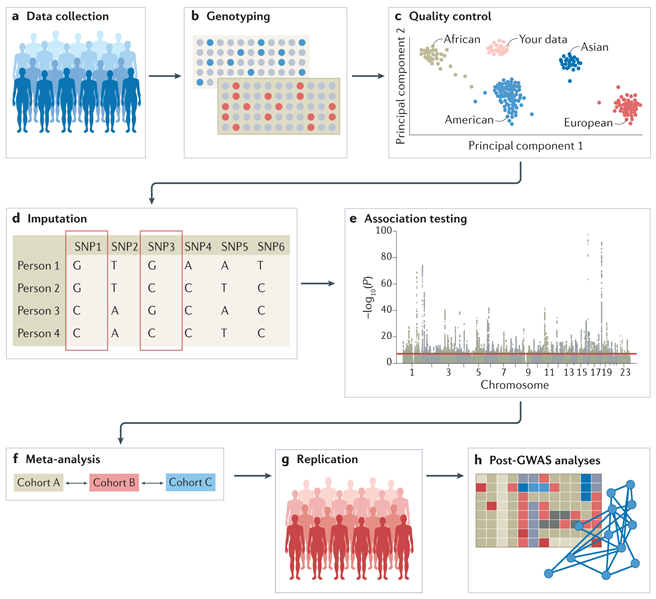

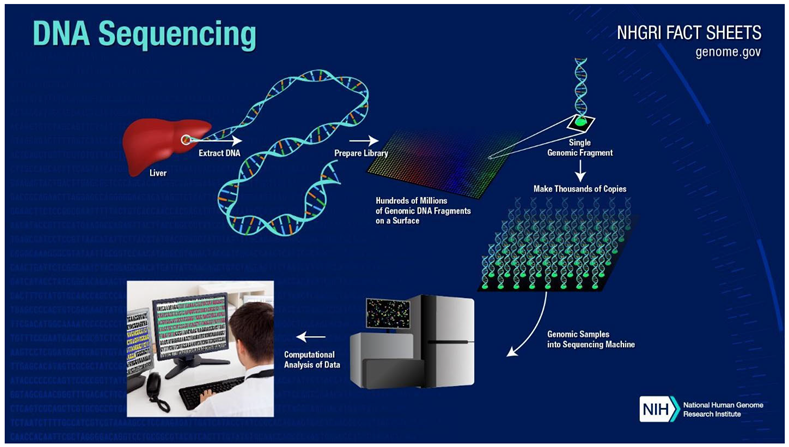

Sequencing Data and Genomic Mapping

Variant Calling and Population Genomics

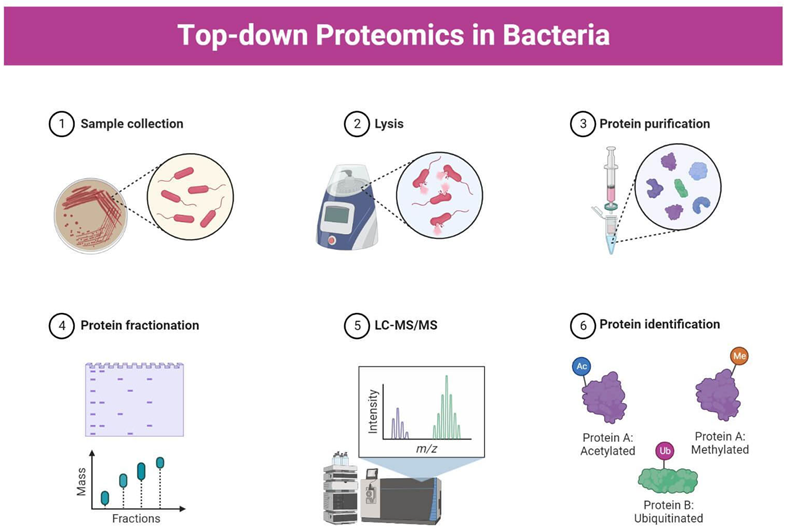

Proteomic Data Analysis

Protein Structure Prediction

- Homology modeling: This approach predicts protein structures based on their similarity to known structures. Mathematical algorithms, such as BLAST and PSI-BLAST, align sequences and identify structural homologs, which are then used as templates to build models of unknown proteins (Samal et al., 2021).

- Ab initio modeling: Using physics-based simulations for proteins with no known homologs, ab initio modeling predicts the structures from scratch. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and energy minimization techniques are mathematical tools used in this approach. Rosetta, a leading tool in ab initio structure prediction, uses Monte Carlo simulations and scoring functions to evaluate the most likely protein conformations.

- AlphaFold, an artificial intelligence-based tool, has revolutionized protein structure prediction using deep-learning algorithms trained on large datasets of known protein structures. The underlying biomathematics include optimization techniques, neural networks, and statistical models to predict the most probable folding pattern.

Functional Annotation of Proteins

Network Analysis in Molecular Interactions

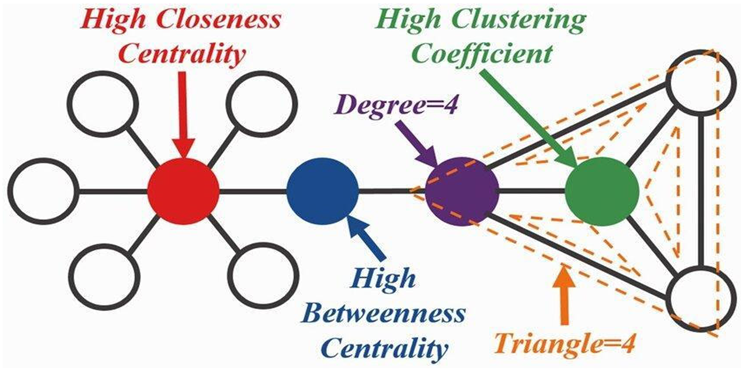

Graph Theory in Molecular Networks

- Nodes represent entities, such as genes, proteins, and metabolites.

- Edges represent relationships, such as protein-protein interactions (PPIs), gene regulatory networks (GRNs), or metabolic pathways.

Systems Biology and Network Models

Comparative Genomics and Phylogenetics

Comparative Genomics

Phylogenetic Analysis

- Maximum likelihood models the evolution of DNA sequences based on statistical probability, generating a tree that best explains the observed data. Tools such as RAxML and PhyML are well known for this method.

- Bayesian methods incorporate the prior knowledge of evolutionary processes and provide a probabilistic framework for tree construction. MrBayes is a tool that uses Bayesian inference to construct phylogenies and integrate uncertainties into the analysis.

Case Studies: Biomathematics in Drug Discovery and Systems Biology

Drug Discovery: Modeling Drug Interactions, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics

Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics Modeling

- Case Study: Remdesivir in COVID-19 Treatment Remdesivir, an antiviral drug originally developed for Ebola, was repurposed for the treatment of COVID-19. Mathematical models of PK/PD were used to determine the optimal dosing regimen for remdesivir, balancing the need for effective antiviral action with the risk of adverse effects (Conway and Wiesch, 2021). A model used compartmental analysis to simulate drug concentrations in plasma and lung tissue, helping researchers determine the appropriate dose and administration schedule for hospitalized COVID-19 patients (Zhang et al., 2022). This biomathematical model has guided clinical trials and was instrumental in establishing remdesivir as one of the first approved treatments for COVID-19.

Molecular Docking and Drug Interactions

- Case Study: HIV Protease Inhibitors The development of HIV protease inhibitors (PIs), such as ritonavir and saquinavir, relies heavily on molecular docking models. Using quantum and statistical mechanics models, researchers have simulated how potential inhibitors would bind to the HIV protease enzyme, which is critical for viral replication (Ghosh et al., 2016). These models not only reduce the time needed to identify effective inhibitors but also guide structural modifications to improve the potency of drugs and minimize resistance.

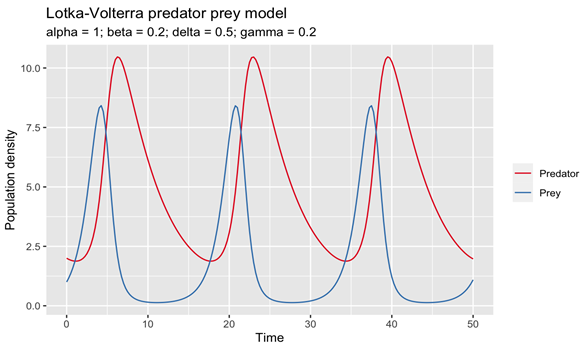

Systems Biology: Modeling Complex Biological Systems

Systems Biology and Network Models

- Case Study: The MAPK Signaling Pathway in Cancer The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway plays a key role in cell proliferation and survival, making it a critical target for cancer therapies. Researchers have developed biomathematical models using ODEs to simulate the dynamics of the MAPK pathway in response to different growth factors and inhibitors (Fröhlich et al., 2023). This model has been used to predict how cancer cells would respond to RAF inhibitors, leading to the development of targeted therapies for melanoma. The model’s predictions were validated through experimental studies, and the insights gained from the model were crucial in designing combination therapies to overcome drug resistance.

Personalized Medicine: Tailoring Treatments Based on Genomic Data

Pharmacogenomics and Biomarker Discovery

- Case Study: HER2-Positive Breast Cancer The development of trastuzumab (Herceptin) for HER2-positive breast cancer is a landmark example of personalized medicine. HER2 is overexpressed in a subset of breast cancers, leading to aggressive tumor growth. Mathematical models based on tumor genomics were used to identify HER2 as a key driver of cancer in these patients, leading to the development of trastuzumab, which specifically targets the HER2 receptor (Swain et al., 2023). By tailoring treatment to patients with HER2-positive tumors, biomathematics plays a crucial role in improving survival rates and reducing adverse effects in patients who are unlikely to benefit from traditional chemotherapy.

Predictive Models for Treatment Optimization

- Case Study: Predicting Chemotherapy Response in Colorectal Cancer In a study a machine learning model was developed to predict how colorectal cancer patients would respond to chemotherapy (Russo et al., 2022). The model integrates genomic data (e.g., mutations in KRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA genes) with clinical variables (e.g., tumor stage and patient age) to predict treatment outcomes. The model successfully identified patients who were likely to benefit from chemotherapy and those who would not, thereby allowing for more personalized treatment decisions. This biomathematical approach helped to optimize patient outcomes while minimizing unnecessary toxicity.

Case Study Examples: Biomathematical Applications in Drug Discovery and Treatment Strategies

- Case Study: The Development of Imatinib (Gleevec) for Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML): The development of imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor used to treat CML, relies heavily on biomathematical models of the BCR-ABL fusion protein, a key driver of CML. Using quantitative modeling of protein interactions and kinase activity, researchers were able to design a drug that specifically targeted the BCR-ABL protein, leading to high efficacy and long-term remission in CML patients (Lai et al., 2024). This biomathematical approach has accelerated the development of imatinib, making it one of the first examples of targeted cancer therapies.

- Case Study: Insulin Dynamics and Diabetes Treatment: In the management of diabetes, mathematical models have been used to simulate insulin-glucose dynamics, leading to the development of insulin pumps and closed-loop systems for blood glucose control (Kovatchev et al., 2009). A mathematical model was developed to describe the interaction between insulin and glucose in the human body, providing a framework for optimizing insulin dosing in patients with diabetes. This model has been integrated into modern artificial pancreas systems, which automatically adjust insulin delivery based on real-time glucose measurements, improve patient outcomes, and reduce the burden of diabetes management.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions in Biomathematics and Bioinformatics

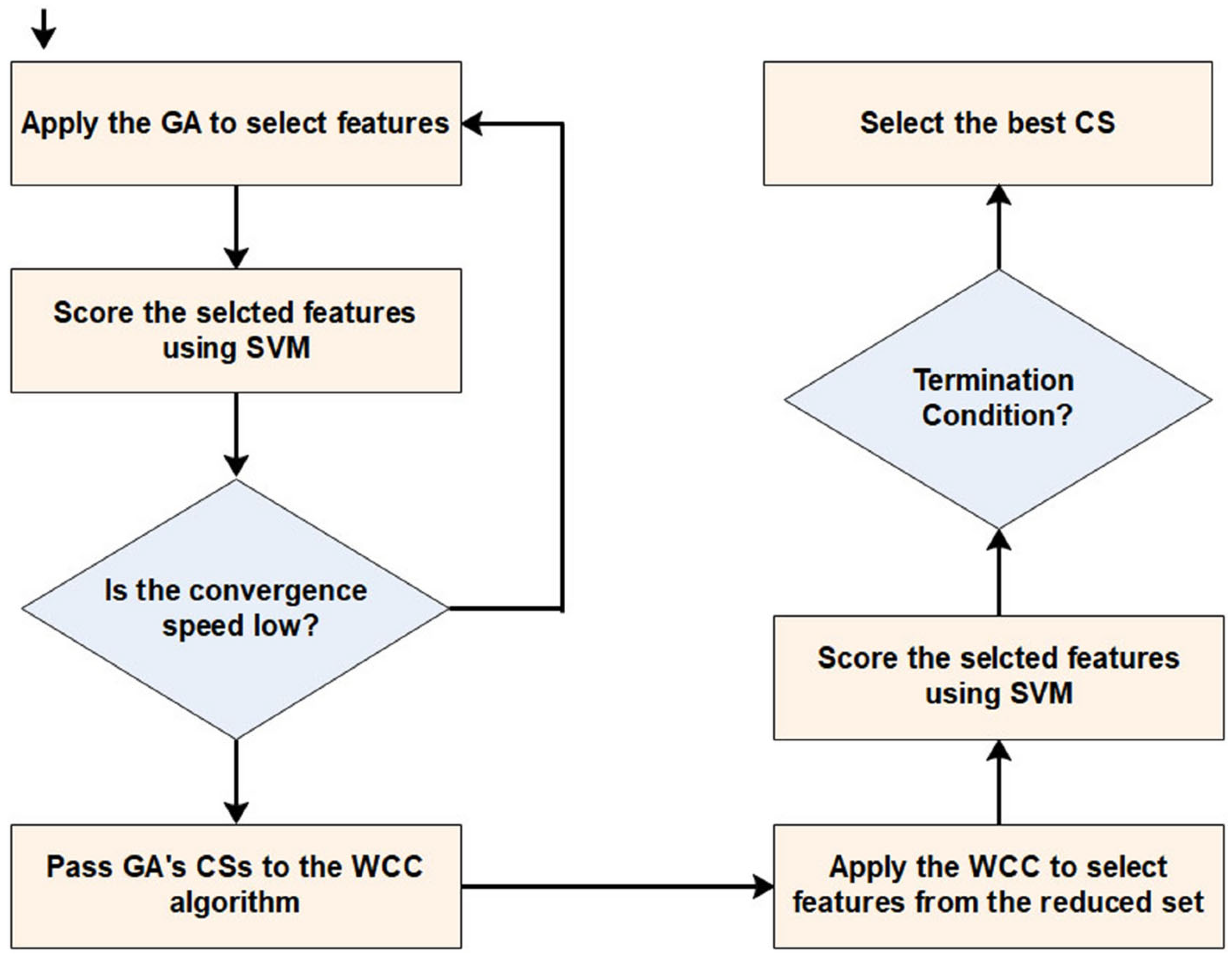

Machine Learning and AI: Revolutionizing Biomathematics in Bioinformatics

Applications of Machine Learning in Bioinformatics

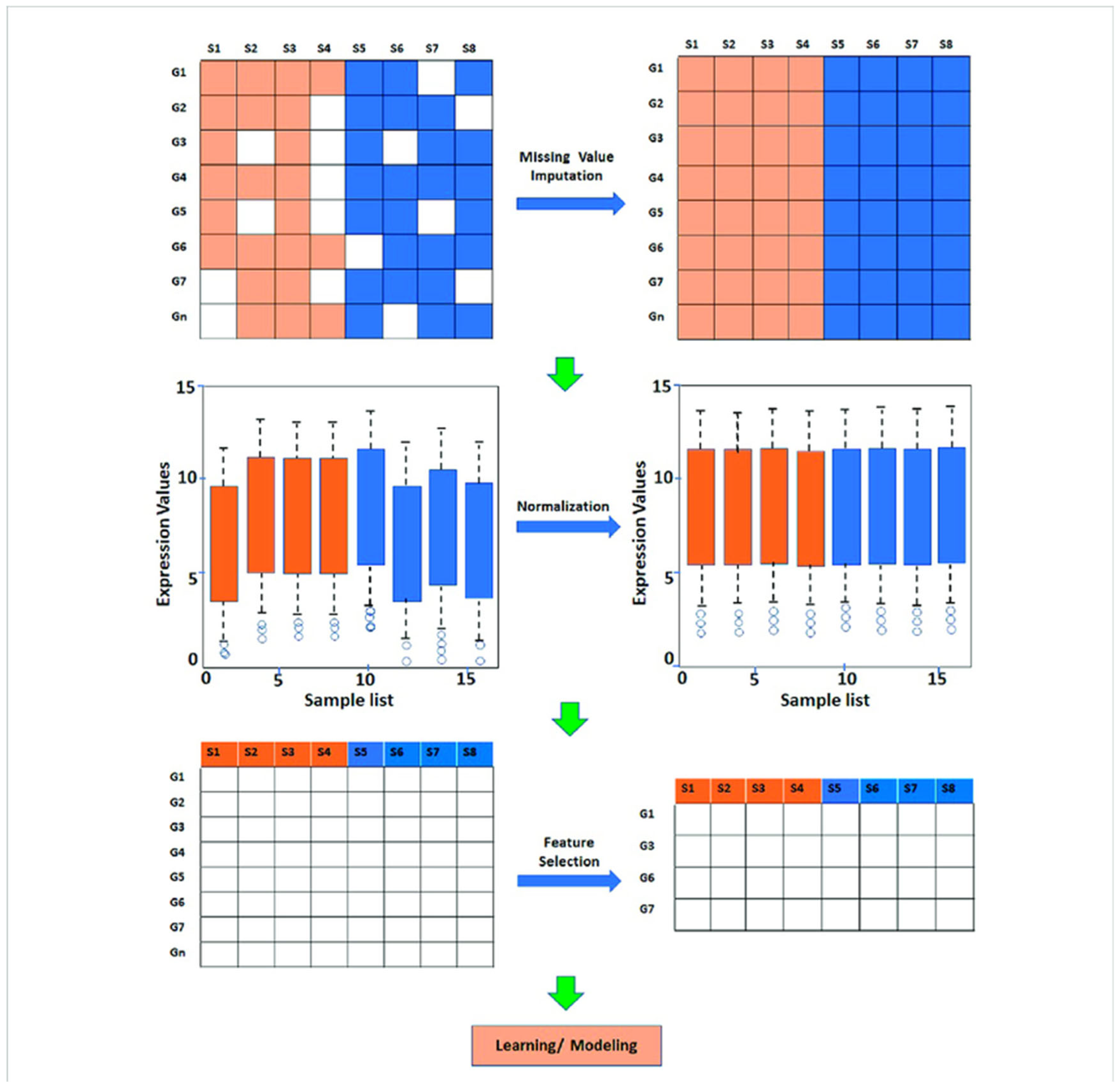

- Predictive Modeling: Machine learning algorithms are widely used to predict various biological outcomes, such as gene expression levels, protein-protein interactions, and patient responses to treatments (Mahood et al., 2020). For instance, gene expression prediction models employ techniques, such as random forests and support vector machines, to analyze large genomic datasets, allowing for accurate predictions of gene activity based on regulatory factors.Figure 9. Steps involved in preprocessing and analysis of gene expression data.

- 2.

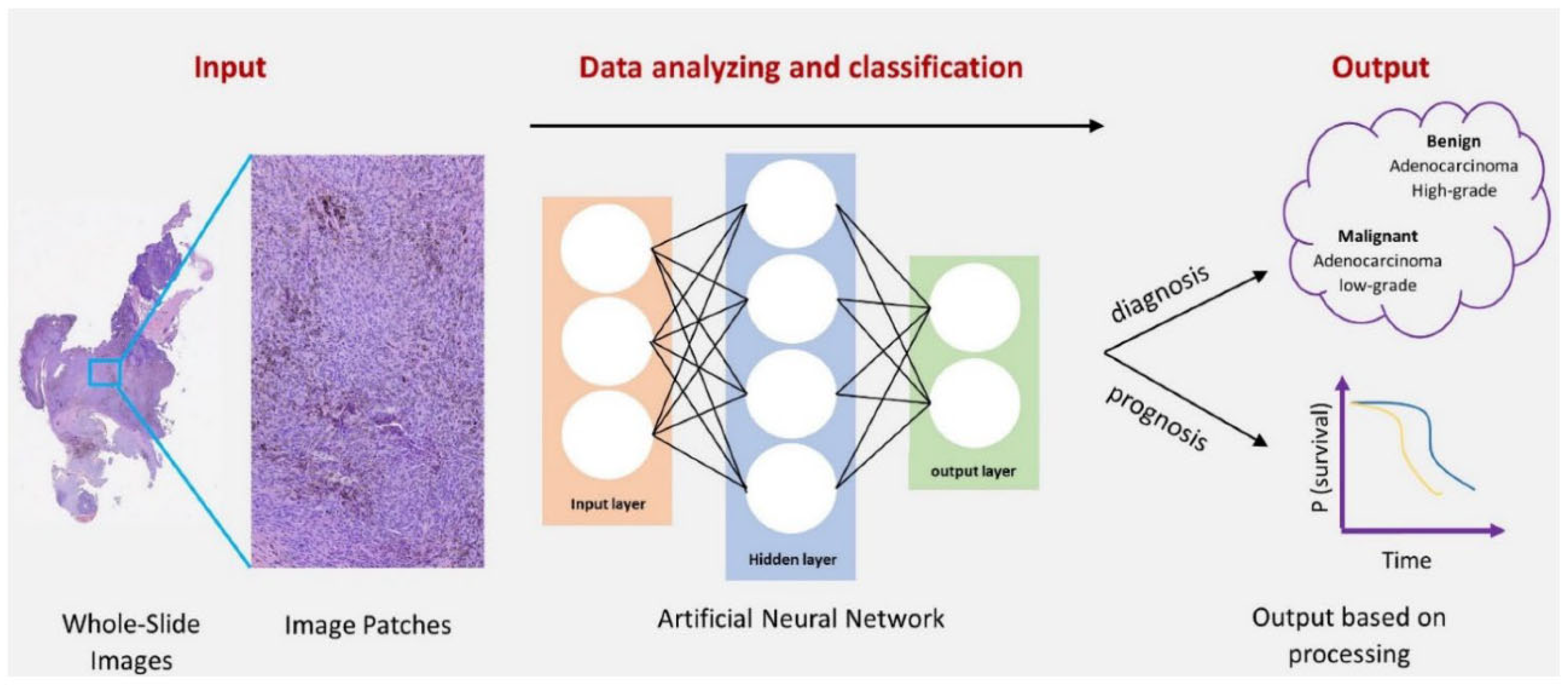

- Image Analysis: AI-driven image analysis is revolutionizing fields, such as medical imaging and histopathology. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are used to analyze histopathological images, helping in the early detection of cancers by identifying abnormal tissue structures (Priya et al., 2024). A notable example is the use of CNNs for detecting breast cancer in mammograms, which significantly improves diagnostic accuracy.Figure 10. Deep Learning Approaches in Histopathology.

- 3.

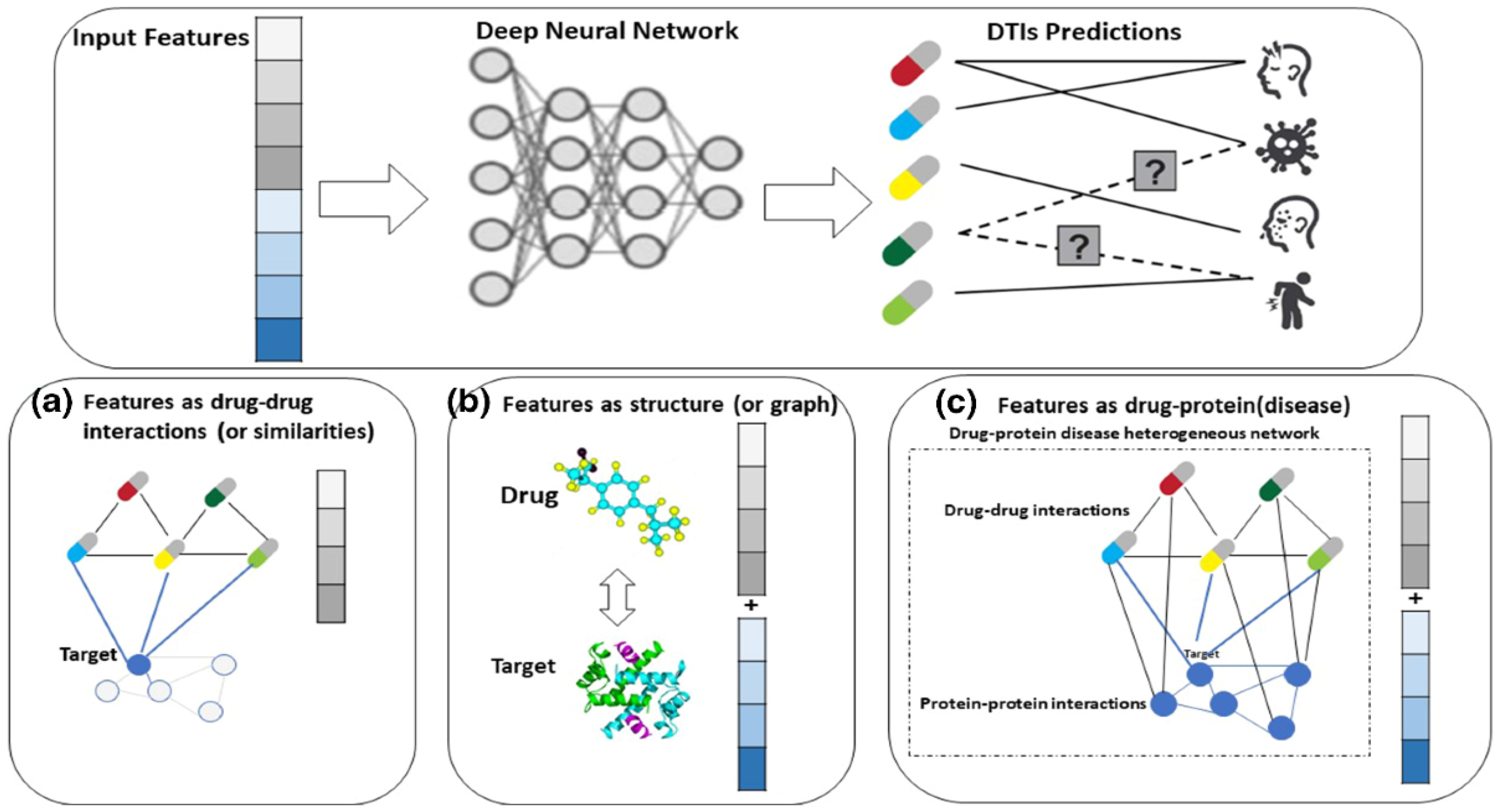

- Drug Discovery: Machine learning has also been applied in drug discovery to predict the efficacy and toxicity of new compounds. Deep learning models can analyze molecular structures and their interactions with biological targets, thereby accelerating the identification of promising drug candidates (Singh et al., 2023). Companies such as Atomwise and In silico Medicine utilize AI-driven platforms to predict molecular interactions and streamline the drug development process.Figure 11. Deep Learning Driven Drug Discovery.

Big Data: Impact and Mathematical Models for Large Datasets

Challenges of Big Data in Bioinformatics

- Data Integration: Biological data are generated from various sources, including genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics. Integrating heterogeneous data types into cohesive models requires sophisticated mathematical techniques (Greene et al. 2014). Approaches, such as multivariate analysis and network modeling, have been employed to correlate different datasets and uncover biological insights.

- Scalability and Computational Efficiency: Mathematical models must be capable of efficiently handling large volumes of data. High-dimensional datasets often present computational challenges, necessitating the development of algorithms that can scale with data sizes (Biomatics, 2024). Techniques such as dimensionality reduction (e.g., principal component analysis) and parallel computing are essential for effectively managing and analyzing big data.

- Real-time Data Analysis: The demand for real-time data analysis is increasing, especially in clinical settings. Algorithms that can analyze streaming data, such as the continuous monitoring of patient health metrics, must be developed (Pal et al., 2020). This requires dynamic mathematical models that are capable of adapting to incoming data and providing timely insights.

Integration with Other Disciplines: Interdisciplinary Approaches

- Physics and Biophysics: The application of physical principles to biological systems has led to the development of models that describe molecular interactions and dynamics. For example, statistical mechanics is used to understand protein folding, whereas quantum mechanics helps to elucidate electron transfer in biochemical reactions (Goh & Wong, 2020).

- Engineering: Techniques from engineering, such as systems engineering and control theory, are being increasingly applied in biological contexts (Goh & Wong, 2020). The development of biomedical devices such as biosensors and microfluidic systems leverages engineering principles to create tools for real-time biological monitoring and analysis.

- Chemistry: Interplay between chemistry and biomathematics is particularly evident in drug design and discovery. Mathematical models that simulate chemical reactions and molecular interactions are crucial for predicting the behavior of new compounds (Goh & Wong, 2020). The field of cheminformatics employs mathematical and statistical methods to analyze chemical data and facilitate drug development.

Future Challenges: Addressing Computational Power, Data Privacy, and Ethical Concerns

- Computational Power: The growing complexity of mathematical models and the increasing volume of biological data require substantial computational resources (Sharma, 2019). Researchers must seek innovative solutions to enhance the computational power, such as leveraging cloud computing and high-performance computing clusters.

- Data Privacy and Security: With integration of personal genomic data into healthcare, ensuring data privacy and security is paramount. Ethical concerns regarding consent, data ownership, and potential misuse of sensitive information must be addressed (Bonomi et al., 2020). Developing frameworks that balance data accessibility for research and privacy protection is essential for fostering trust in genomic research.

- Ethical Considerations: The use of AI and machine learning in healthcare raises ethical questions regarding accountability, bias, and transparency. As algorithms make increasingly autonomous decisions, ensuring fairness and minimizing bias in predictive models are crucial (Martinez-Martin & Magnus, 2019). Establishing ethical guidelines and frameworks for the use of AI in biomathematics and bioinformatics is vital to maintaining public trust and safety.

Conclusions

Summary of Key Findings

- Biomathematics as a Foundation: Biomathematics serves as a foundational discipline in bioinformatics, providing mathematical frameworks and models that enable the analysis and interpretation of complex biological data. Through the application of statistical methods, differential equations, and computational algorithms, biomathematics facilitates a deeper understanding of biological processes such as tumor growth, genetic variation, and protein interactions.

- Development of Computational Tools: The advancement of computational tools in bioinformatics relies heavily on biomathematical principles. The design and implementation of algorithms, databases, and software tools requires a strong mathematical foundation. Tools such as Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) and Bayesian methods exemplify how biomathematical approaches can enhance data analysis and modeling capabilities.

- Application in Genomics and Proteomics: The role of biomathematics in genomics and proteomics has been emphasized, demonstrating its significance in interpreting genomic data, predicting protein structures, and analyzing molecular interactions. Techniques, such as network analysis and comparative genomics, have been instrumental in understanding the complexities of biological systems and their evolutionary relationships.

- Interdisciplinary Collaboration: The integration of biomathematics with other disciplines, including physics, chemistry, and engineering, has opened new avenues for research and application. Interdisciplinary approaches facilitate the development of robust models, innovative methodologies, and enhanced technologies for biological research.

- Emerging Trends and Future Directions: The impact of machine learning, big data, and AI on biomathematics and bioinformatics is underscored. These technologies are transforming the landscape of biological research and providing powerful tools for data analysis and modeling. However, they also present challenges related to the computational power, data privacy, and ethical considerations that must be addressed.

Implications for Research and Practice

- Enhancing Research Capabilities: The integration of biomathematics into bioinformatics provides researchers with sophisticated tools to analyze large datasets and model complex biological systems. This enhances the capacity to uncover insights that were previously unattainable, such as understanding the genetic basis of diseases, predicting patient responses to treatment, and optimizing drug discovery processes.

- Improving Clinical Applications: In clinical practice, the application of biomathematical models and computational tools can lead to more personalized medical approaches. By analyzing individual genomic data, healthcare providers can tailor treatments according to specific patient profiles, improve outcomes, and reduce adverse effects.

- Guiding Policy and Ethical Considerations: As fields of biomathematics and bioinformatics continue to evolve, it is essential to establish guidelines and policies that address ethical considerations, data privacy, and the responsible use of AI in healthcare. Stakeholders, including researchers, policymakers, and clinicians, must collaborate to create frameworks to ensure the ethical application of these technologies.

- Fostering Interdisciplinary Collaboration: The findings of this study highlight the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in advancing biomathematics and bioinformatics. Encouraging partnerships among mathematicians, biologists, computer scientists, and engineers will foster innovation and lead to the development of more effective models and tools for biological research.

Future Research Directions

- Advancements in Machine Learning Algorithms: Future research should focus on developing more sophisticated machine learning algorithms tailored to specific biological questions. This includes improving the predictive modeling capabilities, enhancing the interpretability of AI-driven models, and ensuring that they are robust against biases inherent in biological data.

- Integration of Multi-Omics Data: As field of bioinformatics expands, integrating multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) is a promising area for future research. Developing mathematical models that can effectively integrate and analyze these diverse datasets will provide a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems.

- Real-Time Data Analysis Tools: The demand for the real-time analysis of biological data, particularly in clinical settings, necessitates the development of dynamic mathematical models and computational tools. Future studies should focus on creating algorithms that can analyze streaming data and provide actionable insights for healthcare professionals.

- Ethics and Governance in Bioinformatics: Addressing the ethical implications of biomathematics and bioinformatics is crucial as these fields evolve. Future research should explore frameworks for ethical decision making, data governance, and public engagement to ensure that advancements are made responsibly and transparently.

- Sustainability and Computational Efficiency: As biological datasets continue to grow, research into sustainable computing practices and efficient algorithms will be vital. Exploring methods to reduce the computational burden associated with large datasets will enhance the accessibility and usability of bioinformatics tools.

References

- Akinbusola, Victoria, (2024). Biomathematics in Cancer Research: Looking into How Mathematical Models Are Used to Understand Tumor Growth and the Effectiveness of Different Treatment Strategies. [CrossRef]

- Akinbusola, Victoria (2024). Mathematical modeling of neural networks: Bridging the gap between mathematics and neurobiology. World Journal of Advanced Engineering Technology and Sciences, 2024,13(01), 516–526. [CrossRef]

- Bayat A. (2002). Science, medicine, and the future: Bioinformatics. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 324(7344), 1018–1022. [CrossRef]

- Collins, F. S., & Fink, L. (1995). Human Genome Project. Alcohol health and research world, 19(3), 190–195.

- Conway, J. M., & Abel Zur Wiesch, P. (2021). Mathematical Modeling of Remdesivir to Treat COVID-19: Can Dosing Be Optimized?. Pharmaceutics, 13(8), 1181. [CrossRef]

- Fischer H. P. (2008). Mathematical modeling of complex biological systems: from parts lists to understanding systems behavior. Alcohol research & health: the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 31(1), 49–59.

- Greene, C. S., Tan, J., Ung, M., Moore, J. H., & Cheng, C. (2014). Big data bioinformatics. Journal of cellular physiology, 229(12), 1896–1900. [CrossRef]

- Hassan, M., Awan, F. M., Naz, A., deAndrés-Galiana, E. J., Alvarez, O., Cernea, A., Fernández-Brillet, L., Fernández-Martínez, J. L., & Kloczkowski, A. (2022). Innovations in Genomics and Big Data Analytics for Personalized Medicine and Health Care: A Review. International journal of molecular sciences, 23(9), 4645. [CrossRef]

- Kovatchev, B. P., Breton, M., Man, C. D., & Cobelli, C. (2009). In silico preclinical trials: a proof of concept in closed-loop control of type 1 diabetes. Journal of diabetes science and technology, 3(1), 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Makrodimitris, S., van Ham, R. C. H. J., & Reinders, M. J. T. (2019). Improving protein function prediction using protein sequence and GO-term similarities. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England), 35(7), 1116–1124. [CrossRef]

- Molecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Group. (2024). Tools Molecular Modeling and Bioinformatics Group. Irbbarcelona.org. https://mmb.irbbarcelona.org/www/tools.

- Afanasyeva, A., Nagao, C., & Mizuguchi, K. (2019). Prediction of the secondary structure of short DNA aptamers. Biophysics and Physicobiology, 16, 287–294. [CrossRef]

- Al-Amrani, S., Al-Jabri, Z., Al-Zaabi, A., Alshekaili, J., & Al-Khabori, M. (2021). Proteomics: Concepts and applications in human medicine. World Journal of Biological Chemistry, 12(5), 57–69. [CrossRef]

- Almaden Genomics. (2023, February 6). Scalable and Effective Solutions for Bioinformatics. Almaden. https://almaden.io/blog/scalable-solutions-for-bioinformatics.

- Alok, K., & Shrivastava. (2022). Introduction to bioinformatics (Database searching, Sequence alignment, and alignment affecting factors) Course Code -BOTY 4204 Course Title-Techniques in plant sciences, biostatistics and bioinformatics. https://mgcub.ac.in/pdf/material/20200406015638ec227591f9.pdf.

- ATHAR, M., MANHAS, A., RANA, N., & IRFAN, A. (2024). Computational and bioinformatics tools for understanding disease mechanisms. Biocell, 48(6), 935–944. [CrossRef]

- Biomatics. (2024). Big Data Challenges: Handling Big Data In Bioinformatics . https://biomatics.co.uk/big-data-challenges-handling-big-data-in-bioinformatics/.

- Bonomi, L., Huang, Y., & Ohno-Machado, L. (2020). Privacy Challenges and Research Opportunities for Genomic Data Sharing. Nature Genetics, 52(7), 646–654. [CrossRef]

- Breitwieser, L., Hesam, A., Montigny, de, Vavourakis, V., Iosif, A., Jennings, J., Kaiser, M., Manca, M., Meglio, D., AlArs, Z., Rademakers, F., Mutlu, O., & Bauer, R. (2022). BioDynaMo: a modular platform for highperformance agentbased simulation. Bioinformatics, 38(2), 453–460. [CrossRef]

- Carleton, S. C. (2021, April 28). What is Bioinformatics? Graduate Blog. https://graduate.northeastern.edu/resources/what-is-bioinformatics/.

- Charitou, T., Bryan, K., & Lynn, D. J. (2016). Using biological networks to integrate, visualize and analyze genomics data. Genetics Selection Evolution, 48(1), 27. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y., Li, E.-M., & Xu, L.-Y. (2022). Guide to Metabolomics Analysis: A Bioinformatics Workflow. Metabolites, 12(4), 357. [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. J., & Lillard, J. W. (2024). A Comprehensive Review of Bioinformatics Tools for Genomic Biomarker Discovery Driving Precision Oncology. Genes, 15(8). [CrossRef]

- Clark, L. V., Lipka, A. E., & Sacks, E. J. (2019). polyRAD: Genotype Calling with Uncertainty from Sequencing Data in Polyploids and Diploids. G3 GenesGenomesGenetics, 9(3), 663–673. [CrossRef]

- Cremin, C. J., Dash, S., & Huang, X. (2022). Big data: Historic advances and emerging trends in biomedical research. Current Research in Biotechnology, 4, 138–151. [CrossRef]

- Dey, D. K., Ghosh, S., & Mallick, B. K. (2010). Bayesian Modeling in Bioinformatics. CRC Press.

- Doerr, B., Eremeev, A., Neumann, F., Theile, M., & Thyssen, C. (2011). Evolutionary algorithms and dynamic programming. Theoretical Computer Science, 412(43), 6020–6035. [CrossRef]

- Excedr. (2023, November 27). What Is Bioinformatics & How Does It Compare to Computational Biology? Excedr.com. https://www.excedr.com/blog/what-is-bioinformatics-and-computational-biology#.

- Fan, J., Han, F., & Liu, H. (2014). Challenges of Big Data analysis. Natl Sci Rev, 1(2), 293–314. [CrossRef]

- Fay, D. S., & Gerow, K. (2018). A biologist’s guide to statistical thinking and analysis. In www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. WormBook. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK153593/.

- Fröhlich, F., Gerosa, L., Muhlich, J., & Sorger, P. K. (2023). Mechanistic model of MAPK signaling reveals how allostery and rewiring contribute to drug resistance. Molecular Systems Biology, 19(2), e10988. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. K., Osswald, H. L., & Prato, G. (2016). Recent Progress in the Development of HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of HIV/AIDS. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry, 59(11), 5172–5208. [CrossRef]

- Giró, A., Valls, J., Padr, J. A., & Wagensberg, J. (1986). Monte Carlo simulation program for ecosystems. Bioinformatics, 2(4), 291–296. [CrossRef]

- Goh, W. W. B., & Wong, L. (2020). The Birth of Bio-data Science: Trends, Expectations, and Applications. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 18(1), 5–15. [CrossRef]

- Hoppensteadt, F. (2006). Predator-prey model. Scholarpedia, 1(10), 1563. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S. (2018). Applications of Support Vector Machine (SVM) Learning in Cancer Genomics. Cancer Genomics & Proteomics, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Journal Of Biomedical And Health Informatics. (2024). IEEE JOURNAL OF BIOMEDICAL AND HEALTH INFORMATICS J-B HI Special Issue on “Healthcare Information Systems for Disease Monitoring and Management in Smart Cities.” https://www.embs.org/jbhi/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2023/06/JBHI_SmartCities_SI-1.pdf.

- Lai, X., Jiao, X., Zhang, H., & Lei, J. (2024). Computational modeling reveals key factors driving treatmentfree remission in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Npj Systems Biology and Applications, 10(1), 45. [CrossRef]

- Lakhno, V. D. (2019). Mathematical biology and bioinformatics. Herald of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 81(5), 539–545. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., & Chen, L. (2014). Big Biological Data: Challenges and Opportunities. Genomics, Proteomics & Bioinformatics, 12(5), 187–189. [CrossRef]

- Mahood, E. H., Kruse, L. H., & Moghe, G. D. (2020). Machine learning: A powerful tool for gene function prediction in plants. Applications in Plant Sciences, 8(7), e11376. [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Martin, N., & Magnus, D. (2019). Privacy and ethical challenges in next-generation sequencing. Expert Review of Precision Medicine and Drug Development, 4(2), 95–104. [CrossRef]

- matellio. (2024, February 28). Bioinformatics Software Development: Process, Use Cases, Insights, and More - Matellio Inc. Matellio Inc. https://www.matellio.com/blog/bioinformatics-software-development/.

- Mathematical Institute. (2022). Bioinformatics, Biomathematics and Biostochastics. Uni-Tuebingen.de. https://www.math.uni-tuebingen.de/user/moehle/bio_e.htm.

- Mikolaj, C., & Prusinkiewicz, P. (2019). GillespieLindenmayer systems for stochastic simulation of morphogenesis. In Silico Plants, 1(1), diz009. [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F., Xu, X., & Gao, X. (2021). Impact of computational approaches in the fight against COVID-19: an AI guided review of 17 000 studies. Briefings in Bioinformatics. [CrossRef]

- National Cancer Institute. (2020, March 6). Mapping Cancer Genomic Evolution. Cancer.gov. https://www.cancer.gov/news-events/cancer-currents-blog/2020/mapping-genomic-evolution-as-cancer-develops#.

- Olushola, A., Mart, J., (2022). Fraud Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques. [CrossRef]

- Olushola, A., Mart, J., Alao, V., (2023). Implementations Of Artificial Intelligence In Health Care. [CrossRef]

- Olushola, A., Mart, J., Alao, V., (2023). Predictive Modelling For Disease Outbreak Prediction. [CrossRef]

- Oyewusi, H. A., Wahab, R. A., Akinyede, K. A., Albadrani, G. M., Al-Ghadi, M. Q., Abdel-Daim, M. M., Ajiboye, B. O., & Huyop, F. (2024). Bioinformatics analysis and molecular dynamics simulations of azoreductases (AzrBmH2) from Bacillus megaterium H2 for the decolorization of commercial dyes. Environmental Sciences Europe, 36(1). [CrossRef]

- Pal, S., Bhattacharya, M., Lee, S.-S., & Chakraborty, C. (2023). Quantum Computing in the Next-Generation Computational Biology Landscape: From Protein Folding to Molecular Dynamics. Volume 66. [CrossRef]

- Pal, S., Mondal, S., Das, G., Khatua, S., & Ghosh, Z. (2020). Big data in biology: The hope and presentday challenges in it. Gene Reports, 21, 100869. [CrossRef]

- Parvinen, K. (2022). Ordinary Differential Equations. In E. D. Maria (Ed.), Systems Biology Modelling and Analysis: Formal Bioinformatics Methods and Tools (p. chapter 9). Wiley Online Library. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R., Oliveira, J., & Sousa, M. (2020). Bioinformatics and Computational Tools for Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis in Clinical Genetics. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(1), 132. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, R., Oliveira, J., & Sousa, M. (2020). Bioinformatics and Computational Tools for Next-Generation Sequencing Analysis in Clinical Genetics. Journal of clinical medicine, 9(1), 132. [CrossRef]

- Priya C V, L., V G, B., B R, V., & Ramachandran, S. (2024). Deep learning approaches for breast cancer detection in histopathology images: A review. Cancer biomarkers : section A of Disease markers, 40(1), 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Rosati, D., Palmieri, M., Brunelli, G., Morrione, A., Iannelli, F., Frullanti, E., & Giordano, A. (2024). Differential gene expression analysis pipelines and bioinformatic tools for the identification of specific biomarkers: A Review. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal, 23. [CrossRef]

- Russo, V., Lallo, E., Munnia, A., Spedicato, M., Messerini, L., D'Aurizio, R., Ceroni, E. G., Brunelli, G., Galvano, A., Russo, A., Landini, I., Nobili, S., Ceppi, M., Bruzzone, M., Cianchi, F., Staderini, F., Roselli, M., Riondino, S., Ferroni, P., Guadagni, F., … Peluso, M. (2022). Artificial Intelligence Predictive Models of Response to Cytotoxic Chemotherapy Alone or Combined to Targeted Therapy for Metastatic Colorectal Cancer Patients: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers, 14(16), 4012. [CrossRef]

- Saada, B., Zhang, T., Siga, E., Zhang, J., & Maria. (2024). WholeGenome Alignment: Methods, Challenges, and Future Directions. Applied Sciences, 14(11). [CrossRef]

- Samal, K., Sahoo, J., Behera, L., & Dash, T. (2021). Understanding the BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) Program and a Stepbystep Guide for its use in Life Science Research. Bhartiya Krishi Anusandhan Patrika, 36, 55–61. [CrossRef]

- Saraswathy, N., Ramalingam, P., Saraswathy, N., & Ramalingam, P. (2011). 7 - Genome sequencing methods. In Woodhead Publishing Series in Biomedicine (pp. 95–107). Woodhead Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Schwab, J.D., Kühlwein, S.D., Ikonomi, N., Kühl, M. and Kestler, H.A., 2020. Concepts in Boolean network modeling: What do they all mean?. Computational and structural biotechnology journal, 18, pp.571-582.

- Searls, D. B. (2024, August 14). computational biology. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/computational-biology.

- Sharma, H. (2019). HPCEnhanced Training of Large AI Models in the Cloud. [CrossRef]

- Shmulevich, I., & Aitchison, J. D. (2009). Deterministic and stochastic models of genetic regulatory networks. Methods in enzymology, 467, 335–356. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K. (2023). Convolutional Neural Network in Medical Image Analysis. [CrossRef]

- Singh, S., Kumar, R., Payra, S., Singh, S. K., Singh, S., Kumar, R., Payra, S., & Singh, S. K. (2023). Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Pharmacological Research: Bridging the Gap Between Data and Drug Discovery. Cureus, 15(8). [CrossRef]

- Somda, D., Kpordze, S. W., Jerpkorir, M., Mahora, M. C., Ndungu, J. W., Kamau, S. W., Arthur, V., & Elbasyouni, A. (2023). The Role of Bioinformatics in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Overview. IntechOpen EBooks. [CrossRef]

- Swain, S. M., Shastry, M., & Hamilton, E. (2023). Targeting HER2-positive breast cancer: advances and future directions. Nature reviews. Drug discovery, 22(2), 101–126. [CrossRef]

- Uffelmann, E., Huang, Q. Q., Munung, Nchangwi Syntia, de Vries, Jantina, Okada, Y., Martin, A. R., Martin, H. C., Lappalainen, T., & Posthuma, D. (2021). Genomewide association studies. Nature Reviews Methods Primers, 1(1), 59. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B.-J. (2009). Hidden Markov Models and their Applications in Biological Sequence Analysis. Current Genomics, 10(6), 402–415. [CrossRef]

- Yousef, M., & Allmer, J. (2023). Deep learning in bioinformatics. Turkish Journal of Biology, 47(6), 366–382. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P., Feng, K., Gong, Y., Lee, J., Lomonaco, S., & Zhao, L. (2022). Usage of Compartmental Models in Predicting COVID-19 Outbreaks. The AAPS Journal, 24(5). [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).