Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

11 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

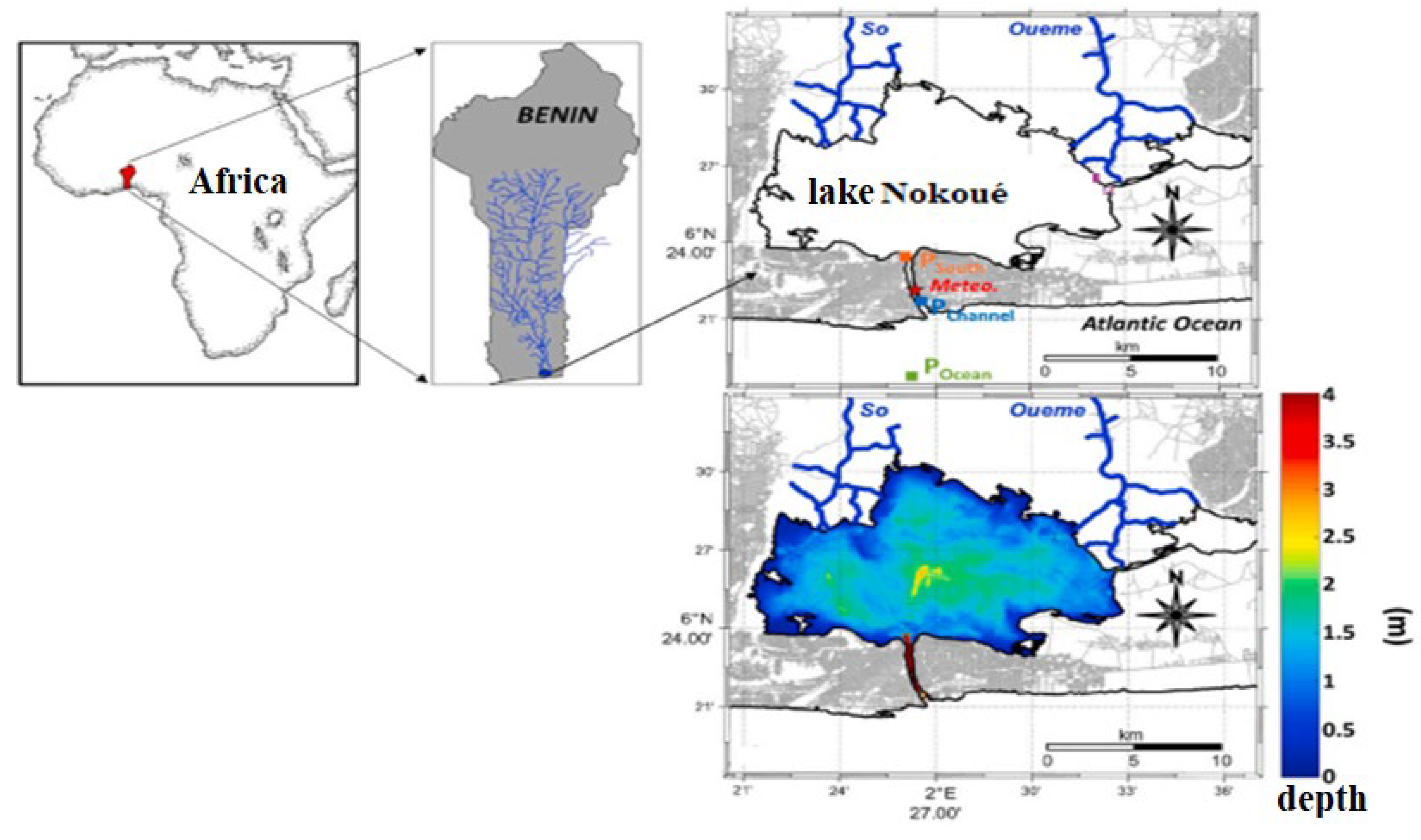

2.1. Study areas

2.2. Statistic Description of Water Level Peaks Values

2.3. Standaedized Water Level Peaks Indices Calculation and Categorization of Flood Hazard

2.4. Implementation of Frequency Models

- Hypothesis testing.

- ✓

- Stationarity test

- -

- H0: The statistical characteristics of the random variables are constant over time.

- -

- H1: The statistical characteristics of the random variables are not constant over time.

- ✓

- Independence test

- -

- H0: the series is independent.

- -

- H1: the series is not independent.

- ✓

- Homogeneity

- Selection and calculation of empirical probabilities of water level peaks values

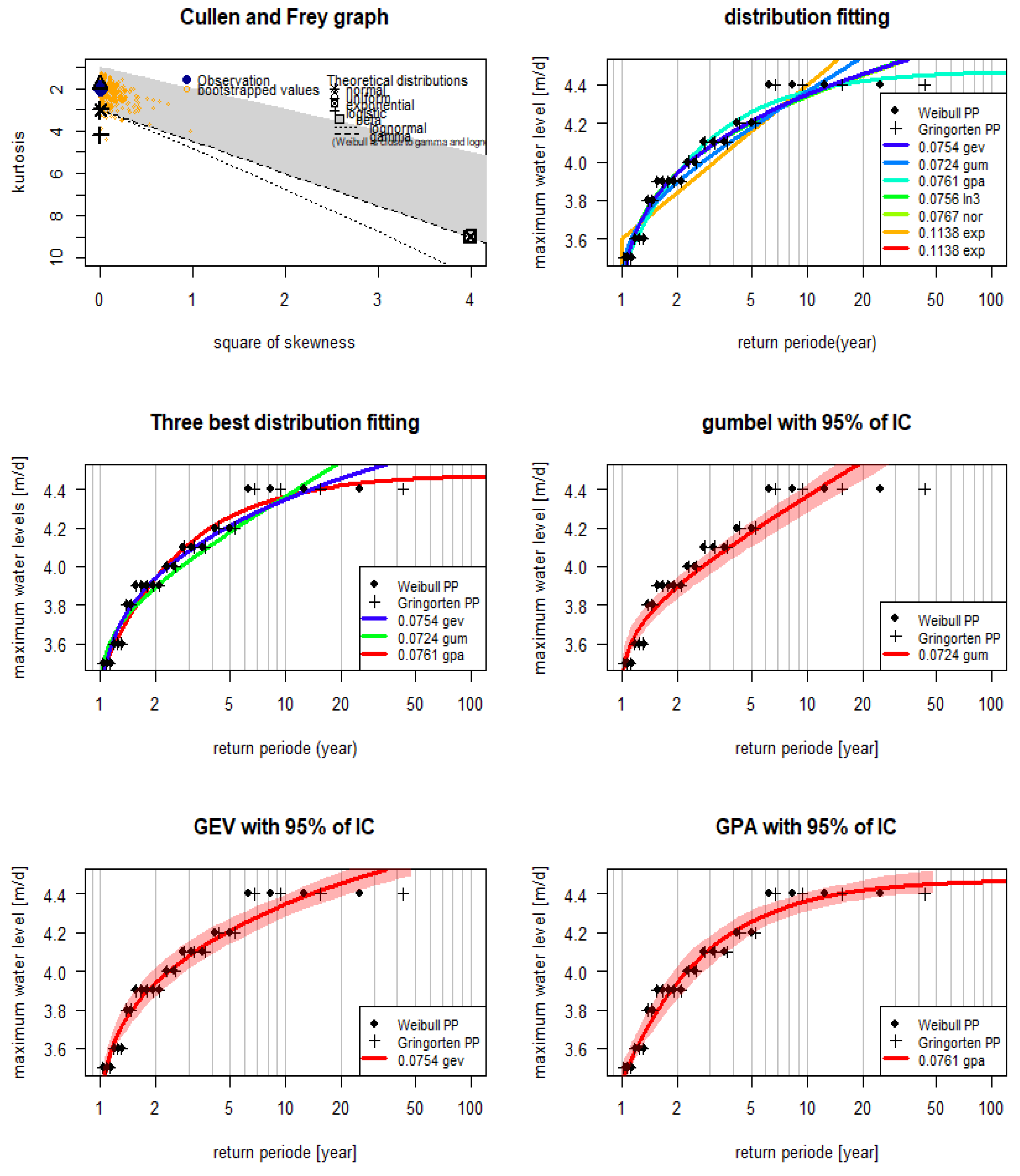

- Fitting distributions to the sample of annual water level peaks values

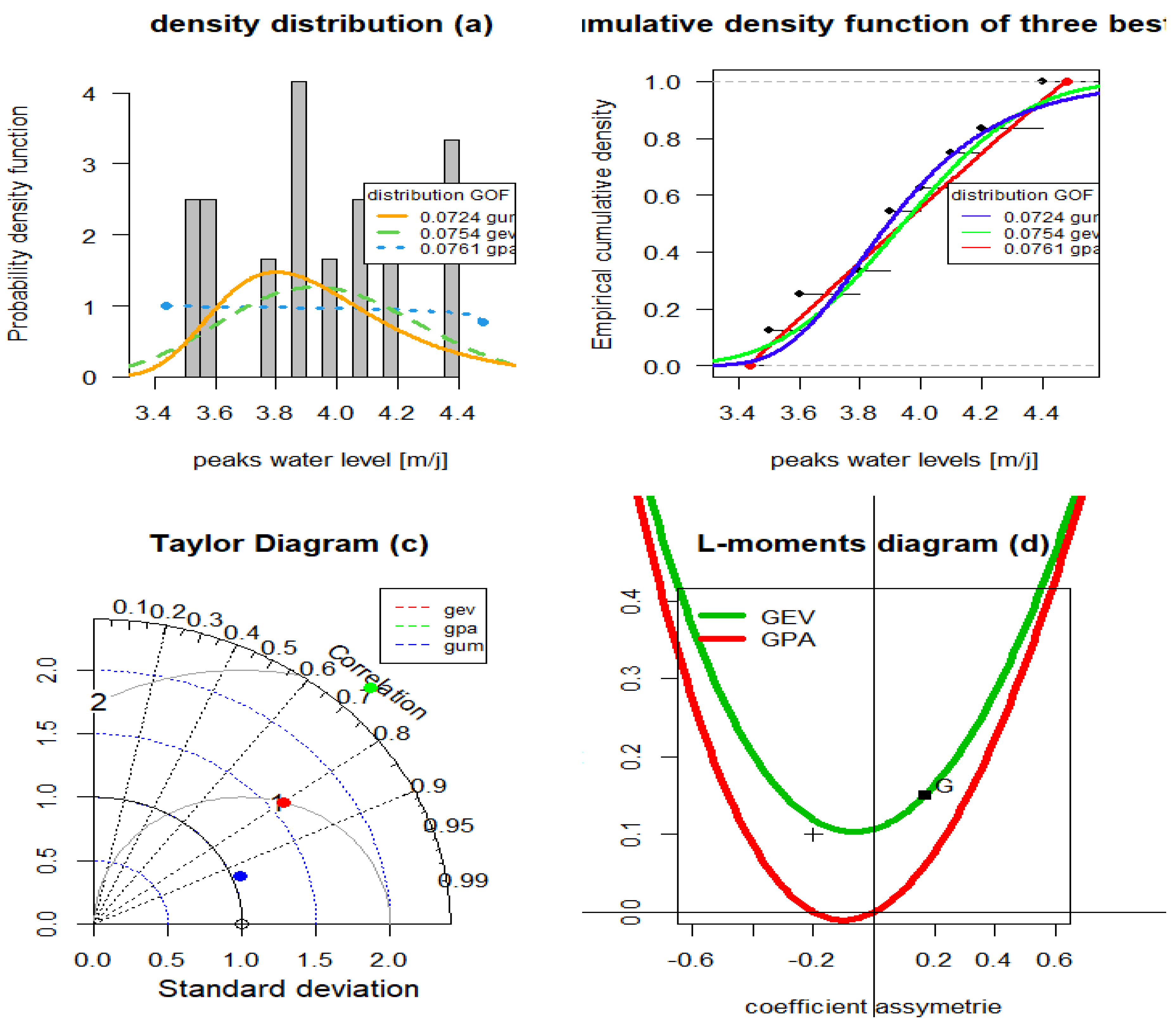

2.5. Model Performance Metrics

- Root Mean Square Error criterion

- Linear moments diagram

- Taylor diagram

3. Results

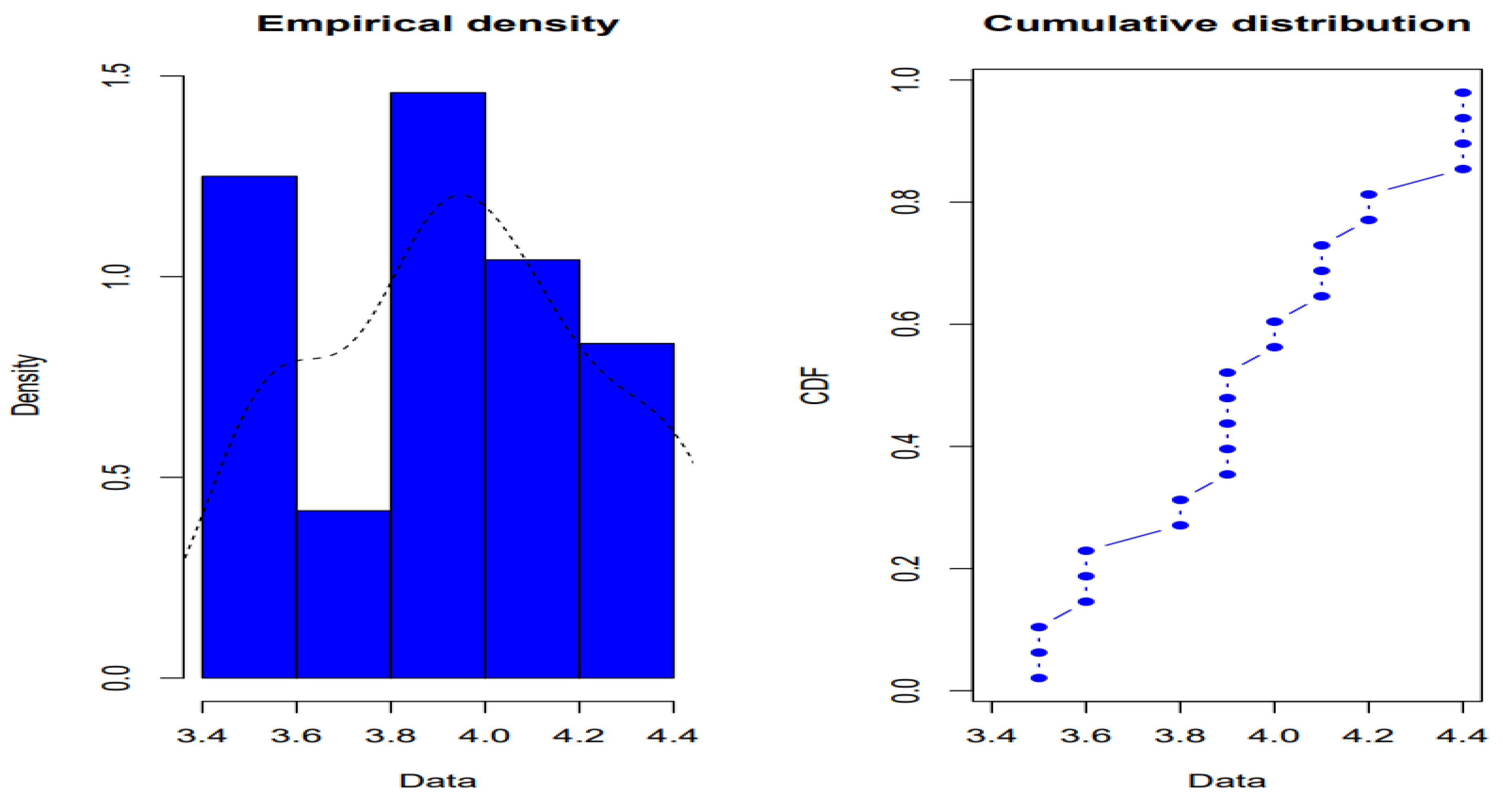

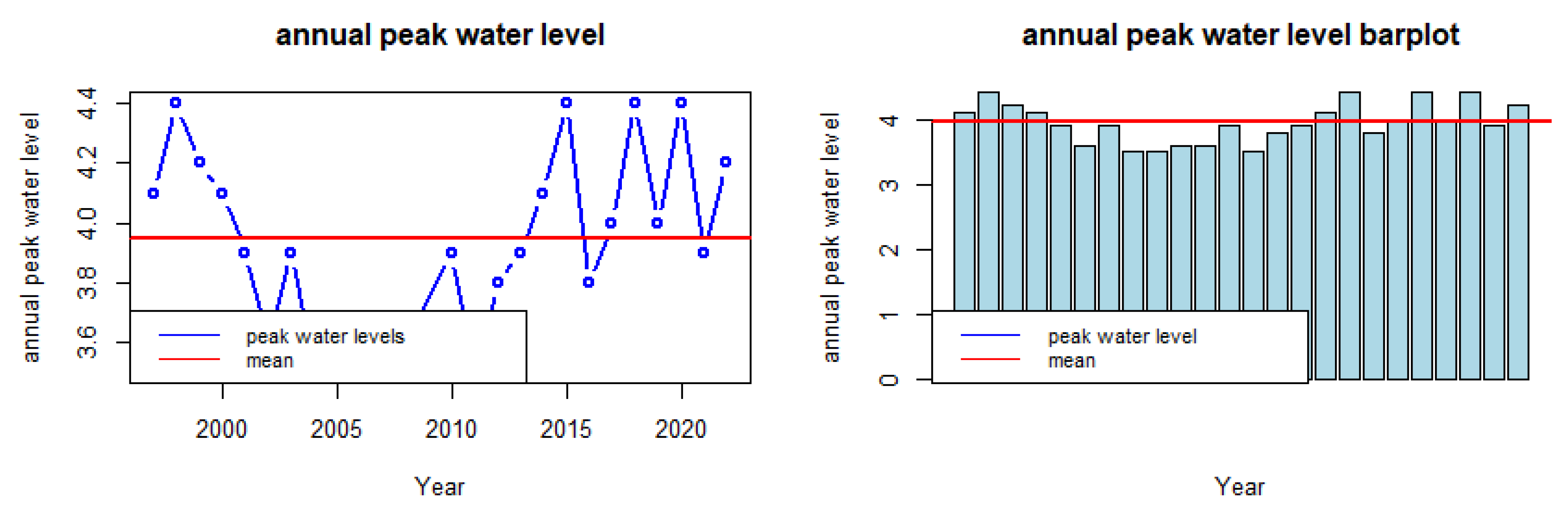

3.1. Description of the Annual Water Level Peaks Values

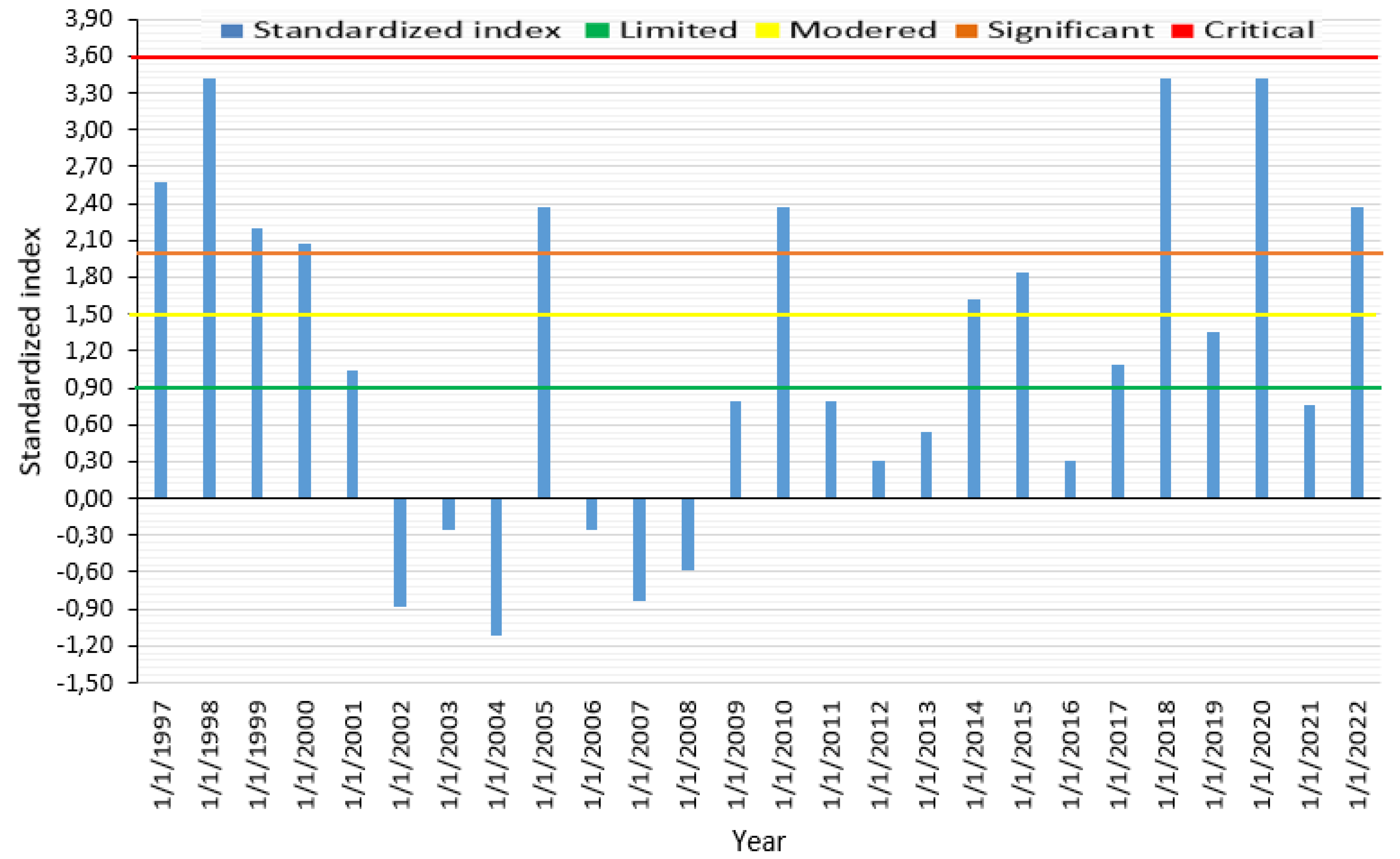

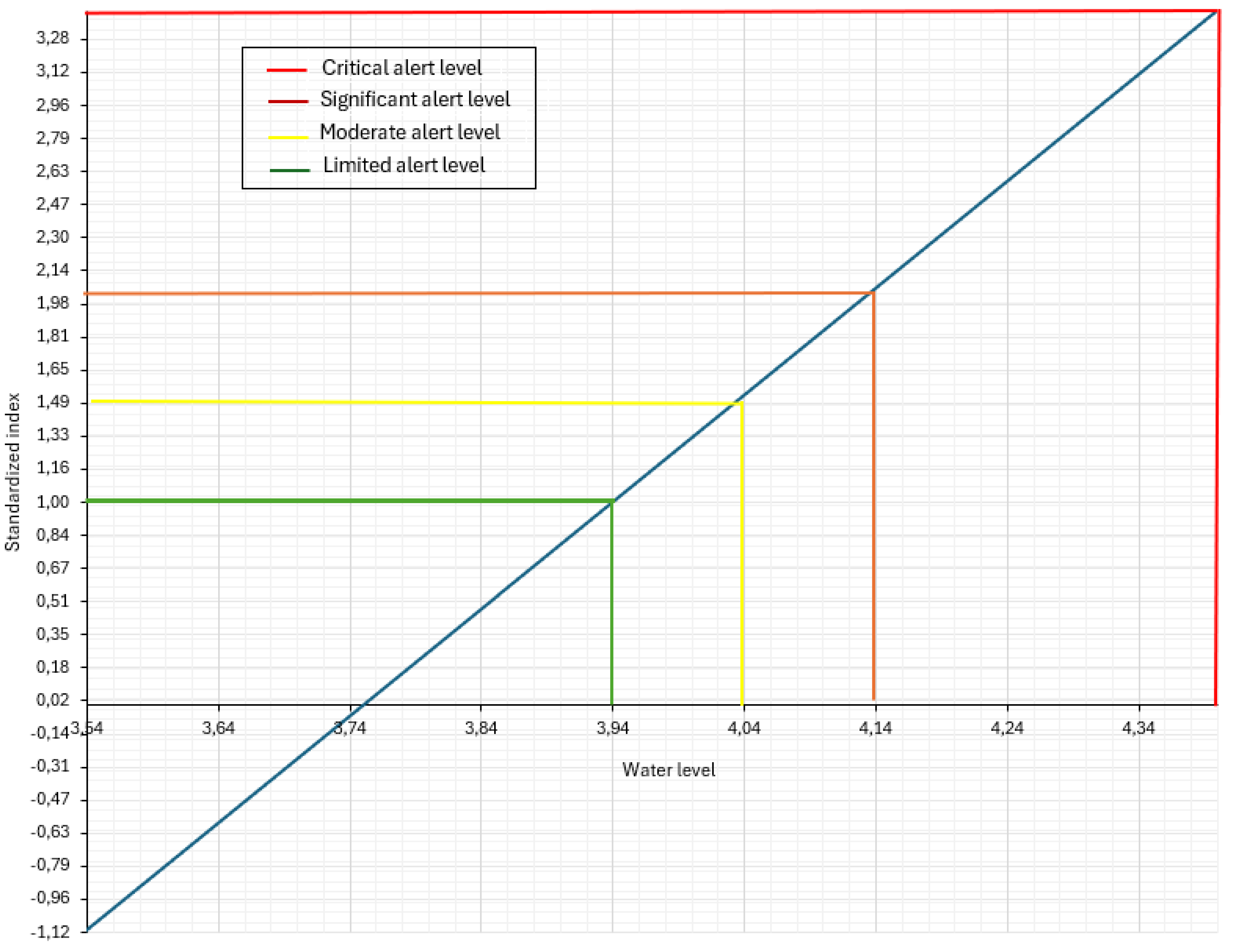

3.2. Results of Standardized Water Level Index

3.3. Results of Hypothesis Tests

- The hypothesis that the data series of annual peak water level is independent is accepted with a 95% confidence level. There is no correlation between the data in the series.

- The absolute value of the Mann-Kendall statistic is evaluated at 0.The hypothesis that there is no trend in data series is accepted at a 5% significance level.

- The absolute value of the Wilcoxon statistic is evaluated at 0.The mean of the two sub-samples (1997-2015 and 2016-2022) is statistically equal, meaning the series is homogeneous. Thus, the null hypothesis is accepted at a 5% significance level.

3.4. Results of Empirical Probability

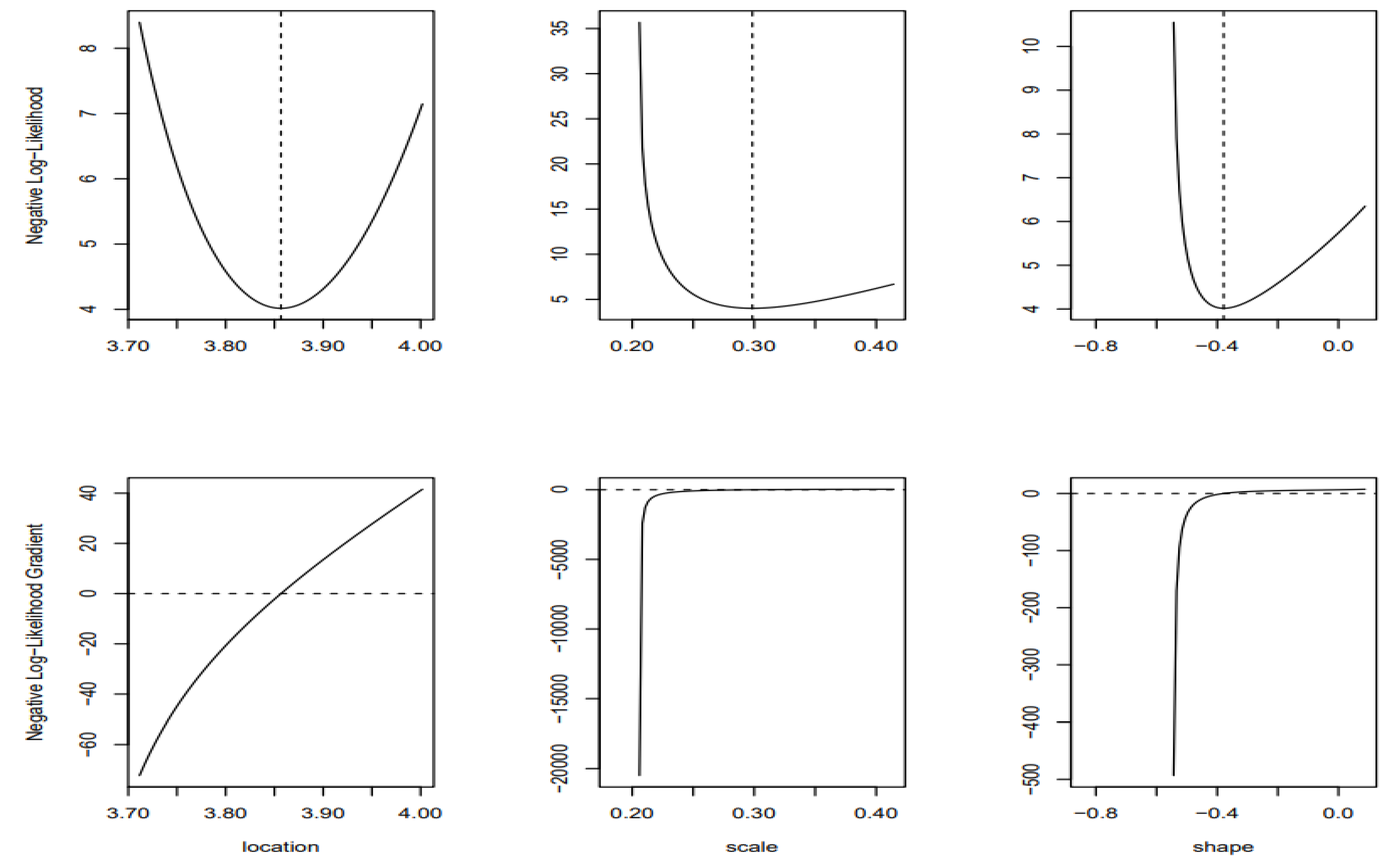

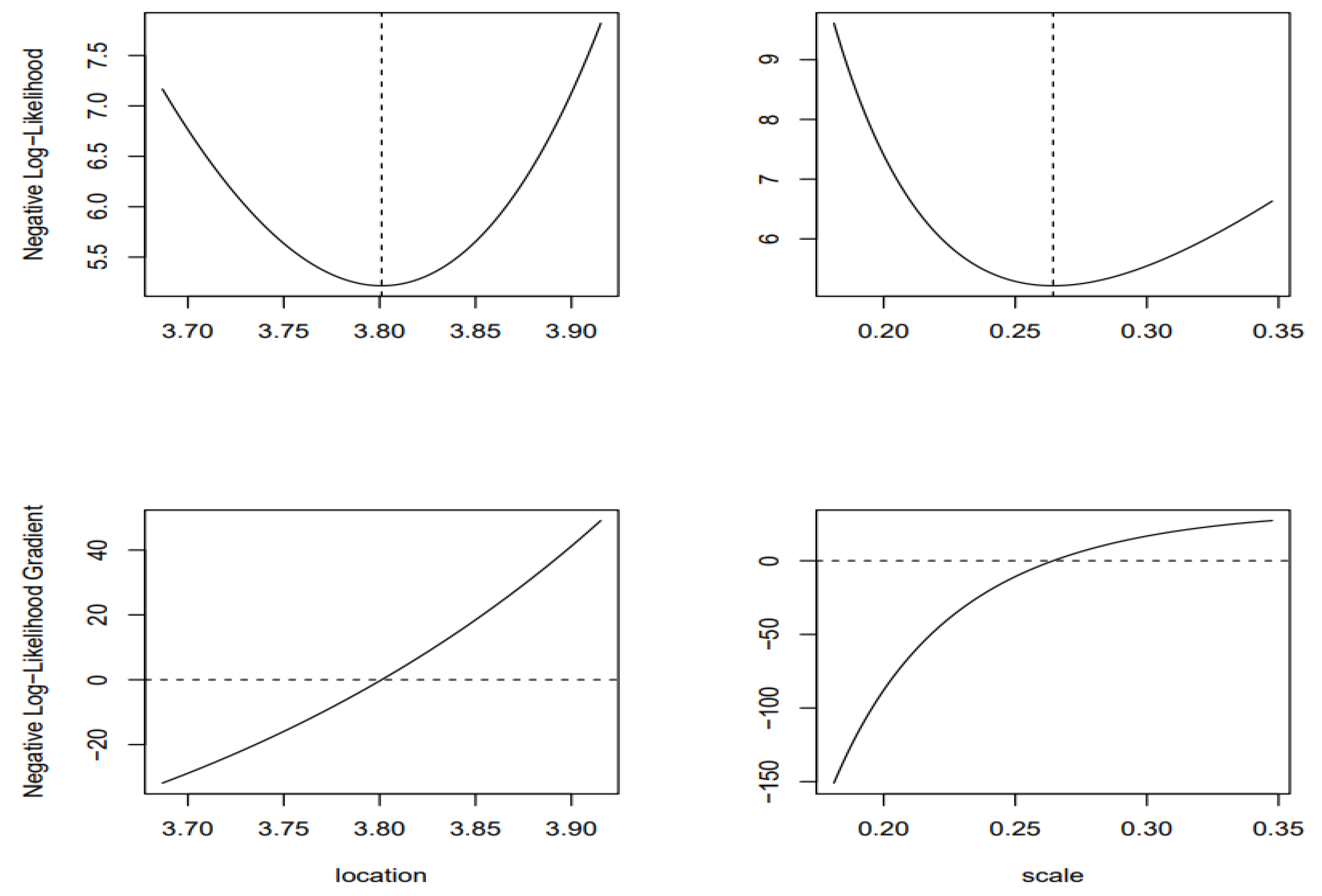

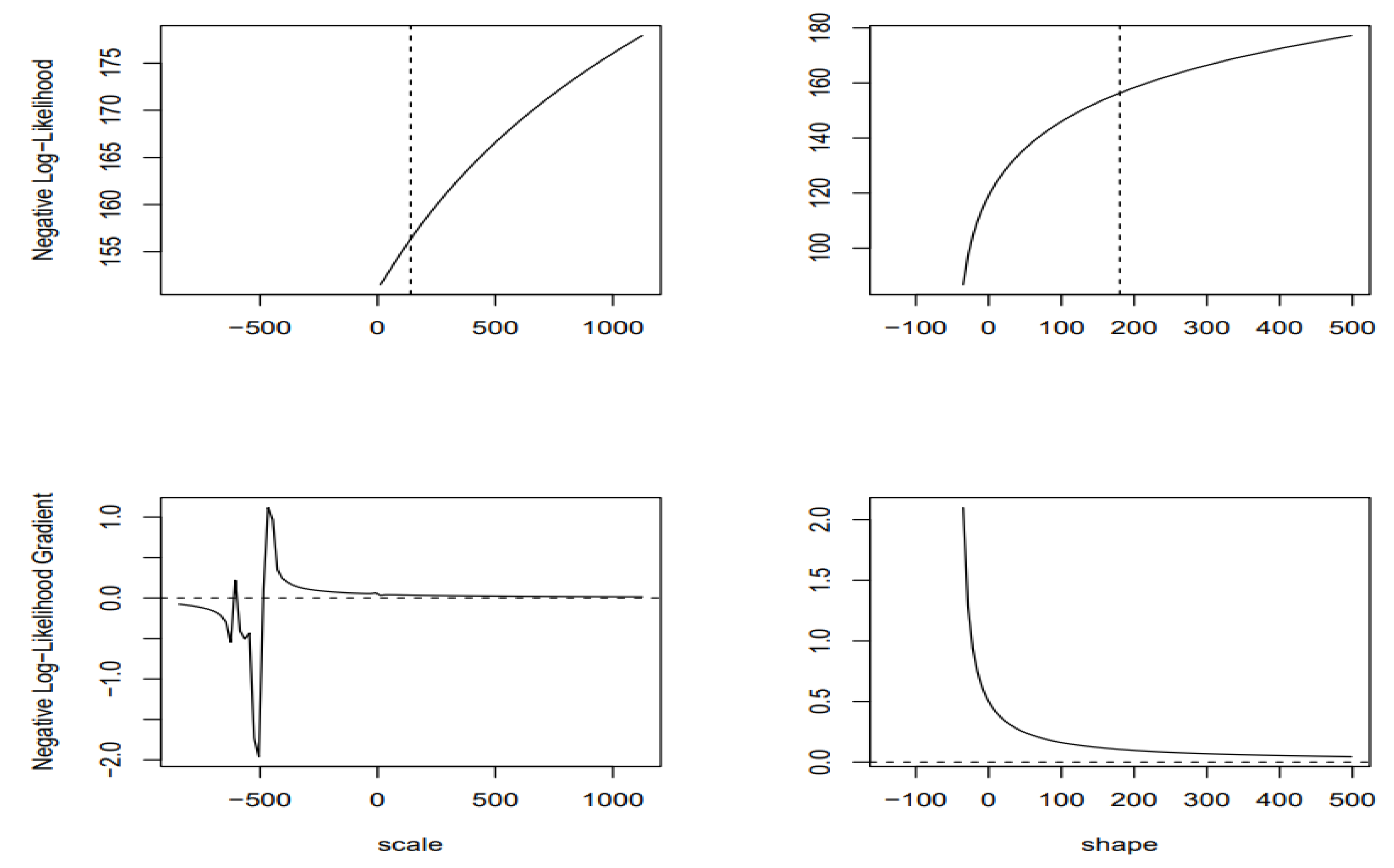

3.5. Results of the Fitting to Statistical Distributions

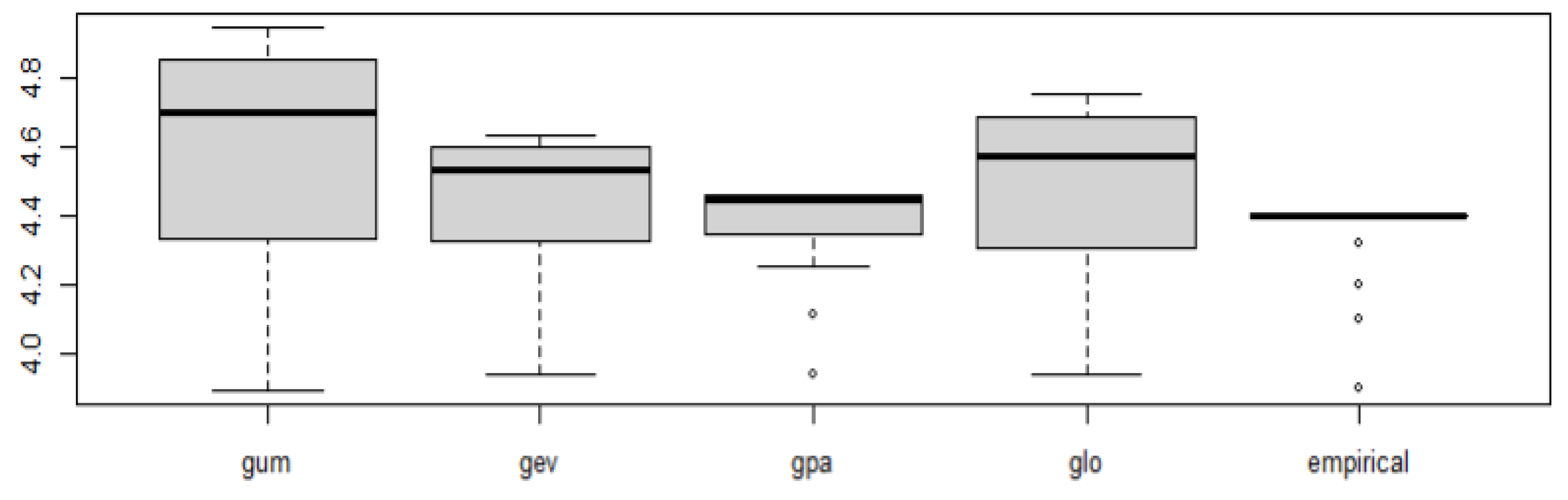

3.6. Results of the Water Level Peaks Estimates for the Gumbel, GEV, and GPA Distributions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Conflicts of interest

References

- S. Yue et P. A. Pilon. Comparison of the power of the test, Mann–Kendall and bootstrap tests for trend detection. Hydrol. Sci. J. 2004,49(1), pp.21 - 38.

- Dabire, N.; Ezin, E.C.;Firmin, A.M. Forecasting Nokoue lagon Water Levels Using Long Short-Term Memory Network. Hydrology journal 2024,.

- Namwinwelbere, D., Eugène, E. C., & Firmin, A. M. Current State of Flooding and Water Quality of Nokoue Lake in Benin (Ouest Africa). European Journal of Environment and Earth Sciences 2022, 3(6), pp.75–81.

- N. Dabire, E.C. Ezin and A.M. Firmin. Water quality index of nokoue lagon prediction using random forest and artificial neural network Int. J. of Adv. Res 2024, pp.610-624.

- N. Dabire, E. C. Ezin and A. M. Firmin. Water Quality Assessment Using Normalized Difference Index by Applying Remote Sensing Techniques: Case of Nokoue lagon. 2024 IEEE 15th Control and System Graduate Research Colloquium (ICSGRC), Shah Alam, Malaysia, 2024, pp.-6, doi:.

- Meylan, P. et Musy, A. Hydrologie fréquentielle. Editions H.G.A Bucarest, 1999, p.413.

- Paturel J. E. et Servat E. Variabilité du régime pluviométrique de l'Afrique de l'Ouest non sahélienne entre 1950 et 1989 : Hydrological Sciences Journal 1998, 43, 921-935.

- Liang Peng and A.H. Welsh. Robust estimation of the generalized pareto distribution. Extremes 2001, 4(1), pp.53–65. [CrossRef]

- Smith R. L Multivariate Threshold Methods. Kluwer, Dordrecht.

- Meylan, P., Favre, A.C, Musy, A. Hydrologie fréquentielle : Une science prédictive. Presses Polytechniques et Universitaires Romandes, 2008, pp.168.

- Édition : Édition du millénaire, p.265.

- Coles S. An Introduction to Statistical Modelling of Extreme Values. Springers Series in Statistics, London, 2001.

- Laborde J.P. Eléments d'hydrologie de surface. L’Université de Nice-Sophia Antipolis, Edition Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (C.N.R.S), 2000, pp.137.

- Hosking J.R.M. and J.R. Wallis. Parameter and quantile estimation for the generalized pareto distribution. Technometrics 1987, 29(3), pp.339–349.

- Kluppelberg C. and A. Bivariate extreme value distributions based on polynomial dependence ¨ functions. Math Methods Appl Sci 2006, 29(12),pp.1467–1480. [CrossRef]

- B. T. Goula, A. Konan, T. Brou, Y. Issiaka, S. V. Fadika et B Srohourou. Estimation des pluies exceptionnelles journalières en zone tropicale: cas de la Côte d'Ivoire par comparaison des lois log normale et de Gumbel. Hydrological sciences journal 2007, 52 (1), pp.49 -67.

- Habibi, M. Meddi et A. Boucefiane. Analyse fréquentielle des pluies journalières maximales : Cas du Bassin Chott-Chergui. Nature et Technology 2013, (8), pp.41.

- N. Soro, T. Lasm, B. H. Kouadio, G. Soro, K. E. Ahoussi. Variabilité du régime pluviométrique du Sud de la Côte d'Ivoire et son impact sur l'alimentation de la nappe d'Abidjan. Rev. Sud Sciences et technologies 2006, (14), pp.30-40.

- Mises, R., von. La distribution de la plus grande de n valeurs. Selected papers, 1954,2, pp.271-294.

- Bortot P. and S. Coles. The multivariate gaussian tail model: An application to oceanographic data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C: Applied Statistics 2000, 49(1), pp.31–49. [CrossRef]

- Coles, J. Heffernan, and J. Tawn. Dependence measures for extreme value analyses. Extremes 1999, 2(4), pp.339–365.

- Fisher R.A. and L.H. Tippett. Limiting forms of the frequency distribution of the largest or smallest member of a sample. In Proceedings of the Cambridge Philosophical Society 1928, 24, pp.180–190. [CrossRef]

- Fréchet M. Sur la loi de probabilité de l’écart maximum. Annales de la Société polo-naise de Mathématique 1927, Cracovie.

- Gumbel É.J. Statistical theory of extreme values and some practical applications. National Bureau of Standards 1954, Washington. [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson A. F. The frequency distribution of the annual maximum (or minimum) values of meteorological events. Quaterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 1955, 81,pp.158–172.

- D. H. Koumassi. Risques hydroclimatiques et vulnérabilité des écosystèmes dans le bassin-versant de la Sota. Thèse de Doctorat de l’Université d’Abomey-Calavi, 2014, pp.244.

- T. P. Zoungrana. Les stratégies d’adaptation des producteurs ruraux à la variabilité climatique dans la cuvette de Ziga, au centre du Burkina Faso". Anales de l’université de Ouagadougou – Série A, Vol. 011, 2010, pp.585 -606.

- S. Rouamba. Variabilité climatique et accès à l’eau dans les quartiers informels de Ouagadougou. Thèse de doctorat de géographie, Université Ouaga I Pr Joseph Ki-Zerbo, 2017, pp.283.

- V. S. H. Totin, E. amoussou, L. Odoulami, M. boko, B. A. Blivi. Seuils pluviométriques des niveaux de risque d’inondation dans le bassin de l’Ouémé au Benin (Afrique de l’ouest) . XXIXe Colloque de l’Association Internationale de Climatologie, Lausanne -Besançon, 2016, pp.369 - 374.

- M. Hache, L. Perreault, L. Remillard et B. Bobee. Une approche pour la sélection des distributions statistiques: application au bassin hydrographique du Saguenay-Lac St-Jean. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 1999, 26 (2), pp. 216 -225.

- Habibi, M. Meddi et A. Boucefiane. Analyse fréquentielle des pluies journalières maximales : Cas du Bassin Chott-Chergui. Nature et Technology, 2013, 3(8), pp.41.

- Jowitt, P.W. The extreme-value type 1 and the principal of maximums entropy. J. Hydrol 1979, 4(2), pp.23-38.

- Juarez S.F. and W.R. Schucany. Robust and efficient estimation for the generalized pareto distribution. Extremes 2004, 7(3), pp.237–251. [CrossRef]

- Pickands J. Multivariate extreme value distributions. In Proceedings 43rd Session International Statistical Institute 1981.

- Pickands J. III. Statistical inference using extreme order statistics. Annals of Statistics, 1975, 3, pp.119–131.

- CIEH. Courbes hauteur de pluie-fréquence Afrique de l‘Ouest et Centrale pour des pluies de duràe 5 mn à 24 h. 1984.

- Christophe Ancey. Risques hydrologiques et aménagement du territoire. École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Ecublens, CH-1015 Lausanne, Suisse,2011.

- Cunnane C. Note on the poisson assumption in partial duration series model. Water Resour Res, 1979, 15(2), pp.489–494. [CrossRef]

- Matthew J. Purvis, Paul D. Bates, Christopher M. Hayes. A probabilistic methodology to estimate future coastal flood risk due to sea level rise,Coastal Engineering 2008, 5(12), pp.1062-1073. [CrossRef]

- Courtney M. Thompson, Tim G. Frazier, Deterministic and probabilistic flood modeling for contemporary and future coastal and inland precipitation inundation, Applied Geography 2014, 50,. [CrossRef]

- ,pp.1-14.

- Roman Krzysztofowicz. Probabilistic flood forecast: Exact and approximate predictive distributions, Journal of Hydrology 2014, 5(17), pp.643-651. [CrossRef]

- Pascal Lardet, Charles Obled. Real-time flood forecasting using a stochastic rainfall generator,. [CrossRef]

- Journal of Hydrology1994, 1(6), pp. 391-408.

- Shien-Tsung Chen, Pao-Shan Yu. Real-time probabilistic forecasting of flood stages,. [CrossRef]

- Journal of Hydrology2007, 3(4), pp.63-77.

- Roman Krzysztofowicz. The case for probabilistic forecasting in hydrology,. [CrossRef]

- Journal of Hydrology2001, 2(4), pp. 2-9.

- Kupfer, S., MacPherson, L. R., Hinkel, J., Arns, A., & Vafeidis, A. T. A comprehensive probabilistic flood assessment accounting for hydrograph variability of ESL events. Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans, 2024 , pp.129. [CrossRef]

- Karl-Erich Lindenschmidt, Prabin Rokaya, Apurba Das, Zhaoqin Li, Dominique Richard. A novel stochastic modelling approach for operational real-time ice-jam flood forecasting, Journal of Hydrology 2019, 5(7), pp.381-394. [CrossRef]

- S. I. Resnick. Extreme Values, Regular Variation and Point Processes. New–York: Springer–Verlag, 1987.

- R Development Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2006.

- C. Kluppelberg and A. May. Bivariate extreme value distributions based on polynomial dependence ¨ functions. Math Methods Appl Sci, 2006, 29(12), pp.1467–1480. [CrossRef]

- M. Falk and R.-D. Reiss. On pickands coordinates in arbitrary dimensions. Journal of Multivariate Analysis, 2005, 92(2), pp.426–453. [CrossRef]

- S. Coles. An Introduction to Statistical Modelling of Extreme Values. Springer Series in Statistics. Springers Series in Statistics, London, 2001.

- Izinyon, N. Ihimekpen et G.E. Igbinoba. Analyse de la fréquence des inondations du bassin versant de la rivière Ikpoba à Benin City à l’aide de la distribution Log Pearson de type III. Journal des tendances émergentes en génie et en sciences appliquées 2011, 2(1), pp.50–55.

- .Mujere N. Flood frequency analysis using the Gumbel distribution. Int J Comput Sci Eng 2011, 3(7), pp.2774–2788.

- Mukherjee MK. Flood frequency analysis of River Subernarekha, India, using Gumbel’s extreme value distribution. Int J Comput Eng Res 2013, 3(7), pp.12–19.

- Singo LR, Kundu PM, Odiyo JO, Mathivha FI, Nkuna TR. Flood frequency analysis of annual maximum stream flows for Luvuvhu River catchment, Limpopo Province, South Africa. University of Venda, Department of Hydrology and Water Resources, Thohoyandou, South Africa 2013, pp. 1–9.

- E. Haque. Flood Frequency Analysis of the Kaljani River of West Bengal: A Study in Fluvial Geomorphology. In: Das, J., Halder, S. (eds) New Advancements in Geomorphological Research. Geography of the Physical Environment 2024 Springer, Cham,.

| Risk Level | Risk categories |

|---|---|

| Critical | ≥ 2.0 |

| Significant | < 2 |

| Moderate | < 1.5 |

| Limited | < 1 |

| min | 25% | 50% | 75% | max | Standard diviation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 | 3.75 | 3,95 | 4.13 | 4,4 | 0.2 |

| Statistical tests | p-value | Status |

|---|---|---|

| independance | 0.12 | accepted |

| Homogeneity | 0.14 | accepted |

| Stationarity | 0.14 | accepted |

| Statistical distributions | Parameters | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| lois de Gumbel | 3.80 0.25 | ||

| lois GEV | 0.30 0.3 | 0.27 | |

| Lois GPA | 3.43 1.003 | 0.96 | |

| 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.01 | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gumbel | 3.642573 | 3.720708 | 3.893353 | 4.112385 | 4.175660 | 4.362572 | 4.947841 | 0.07238795 |

| GEV | 3.625181 | 3.732998 | 3.941547 | 4.156290 | 4.209517 | 4.347250 | 4.636763 | 0.07543231 |

| GPA | 3.585419 | 3.686597 | 3.941998 | 4.202556 | 4.255658 | 4.363591 | 4.465037 | 0.07610624 |

| Empirical | 3.598333 | 3.683333 | 3.900000 | 4.158333 | 4.200000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | |

| Quantiles mean | 3.592593 | 3.663426 | 3.900000 | 4.134954 | 4.200000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| RP.2 | RP.3 | RP.6 | RP.7 | RP.8 | RP.9 | RP.10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gumbel | 3.893353 | 4.026908 | 4.225984 | 4.267789 | 4.303554 | 4.334811 | 4.362572 |

| GEV | 3.941547 | 4.078418 | 4.249350 | 4.280847 | 4.306698 | 4.328494 | 4.347250 |

| GPA | 3.941998 | 4.114921 | 4.291336 | 4.316985 | 4.336328 | 4.351446 | 4.363591 |

| Empirical | 3.500000 | 3.900000 | 4.200000 | 4.322222 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| Q mean | 3.500000 | 3.900000 | 4.200000 | 4.270988 | 4.384127 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| RP.15 | RP.20 | RP.30 | RP.35 | RP.40 | RP.45 | RP.50 | |

| Gumbel | 4.468026 | 4.541862 | 4.645004 | 4.684007 | 4.717721 | 4.747411 | 4.773935 |

| GEV | 4.413629 | 4.455843 | 4.509497 | 4.528292 | 4.543918 | 4.557220 | 4.568751 |

| GPA | 4.400367 | 4.419004 | 4.437885 | 4.443340 | 4.447454 | 4.450669 | 4.453252 |

| Empirical | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| Q mean | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| RP.55 | RP.60 | RP.70 | RP.75 | RP.80 | RP.85 | RP.90 | |

| Gumbel | 4.797905 | 4.819768 | 4.858464 | 4.875768 | 4.891948 | 4.907140 | 4.921459 |

| GEV | 4.578894 | 4.587922 | 4.603390 | 4.610103 | 4.616268 | 4.621961 | 4.627242 |

| GPA | 4.455374 | 4.457148 | 4.459948 | 4.461073 | 4.462060 | 4.462933 | 4.463711 |

| Empirical | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| Q mean | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

| RP.95 | RP.100 | ||||||

| Gumbel | 4.934999 | 4.947841 | |||||

| GEV | 4.632162 | 4.636763 | |||||

| GPA | 4.464408 | 4.465037 | |||||

| Empirical | 4.400000 | 4.400000 | |||||

| Q mean | 4.400000 | 4.400000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).