Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

07 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

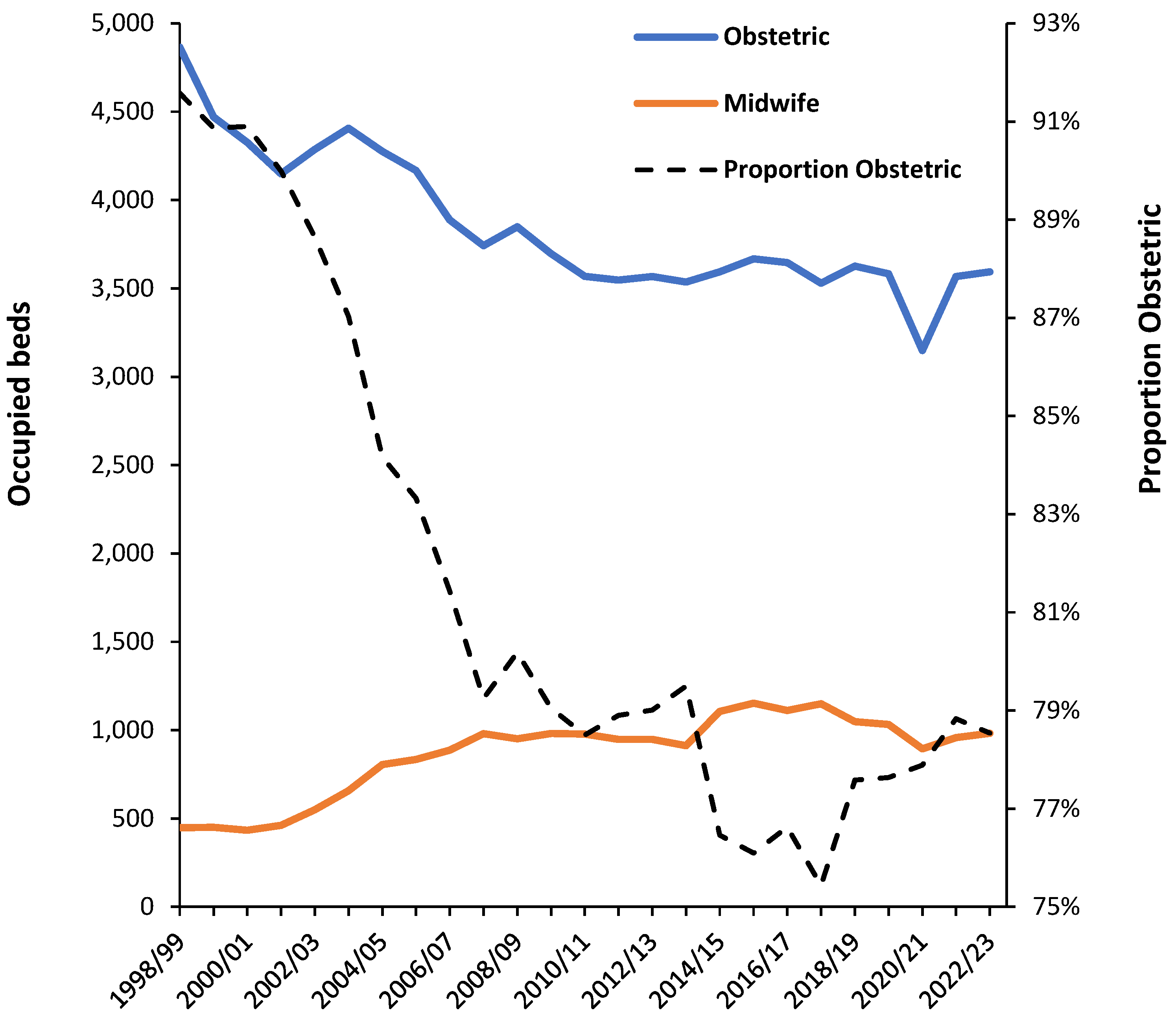

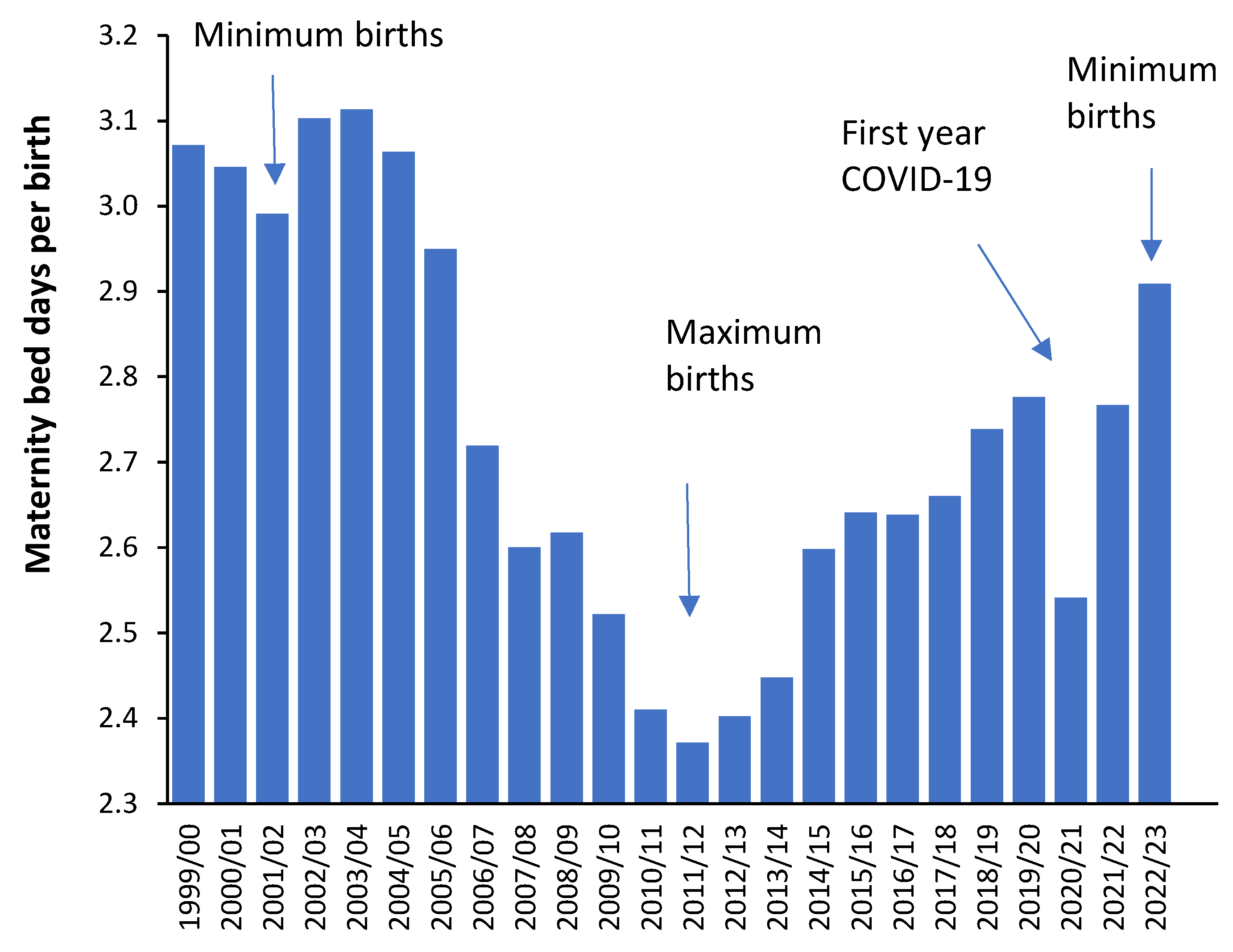

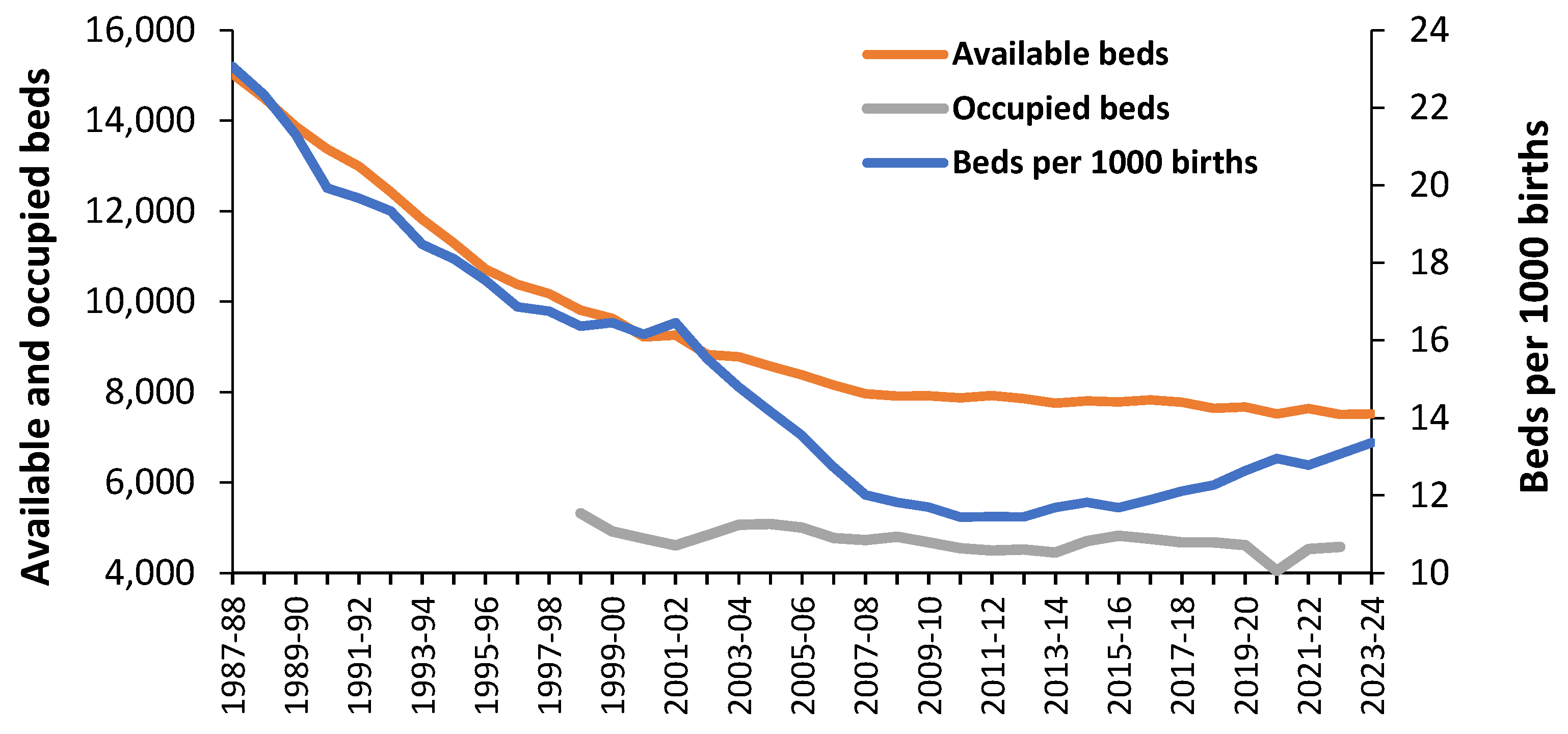

3.1. Trends in Available Beds in England

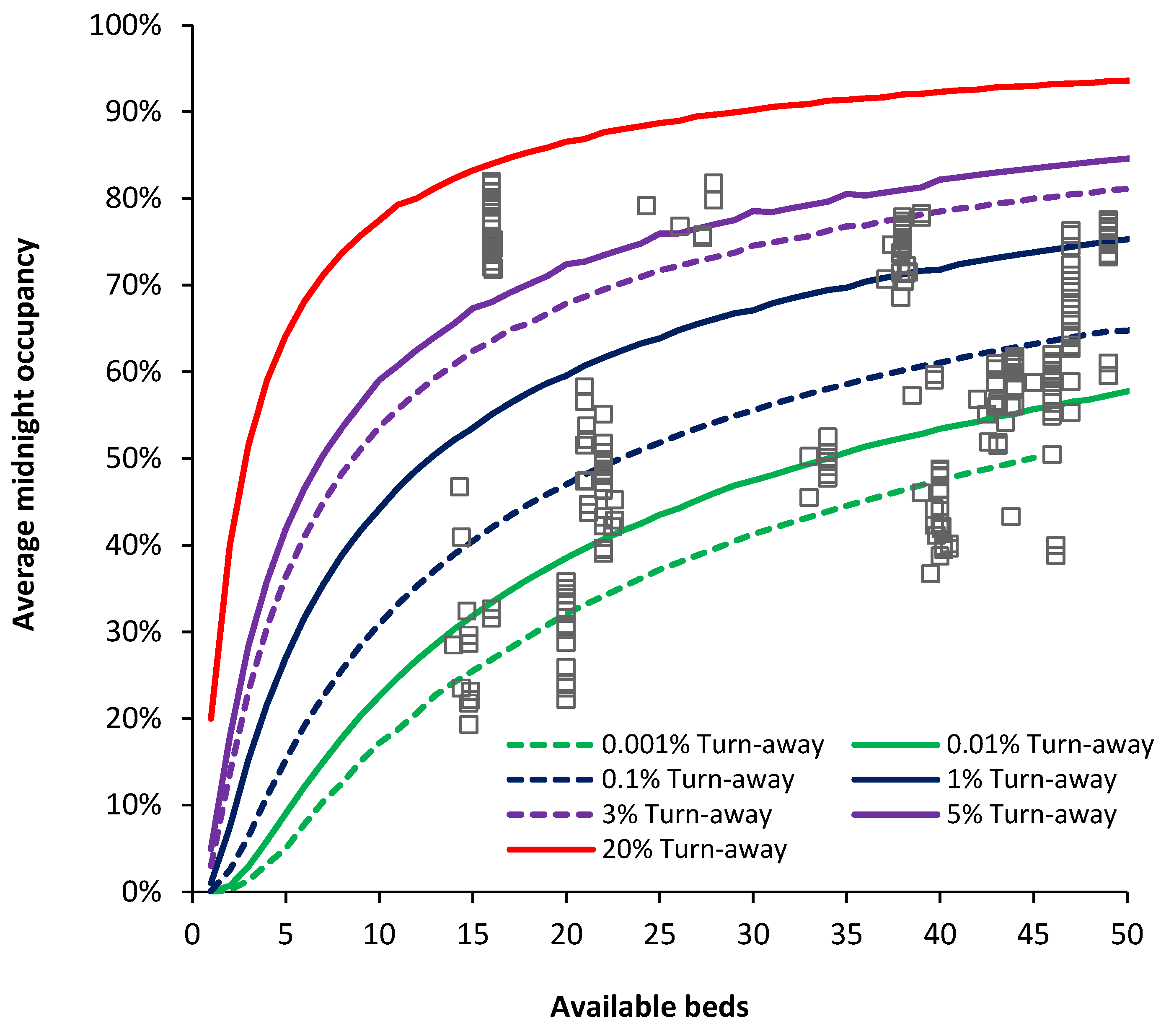

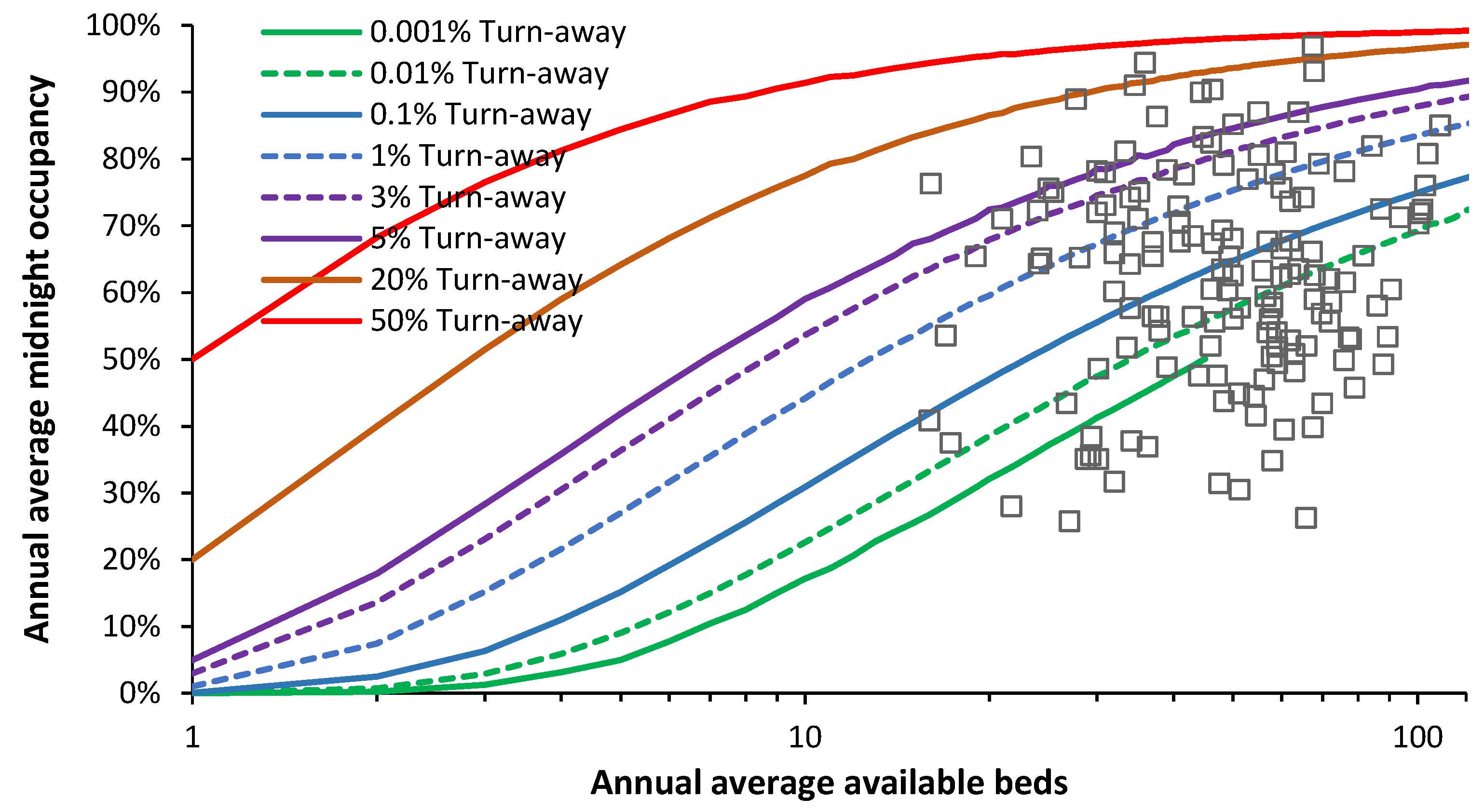

3.2. Assessing Current Bed Sufficiency Using Average Bed Occupancy

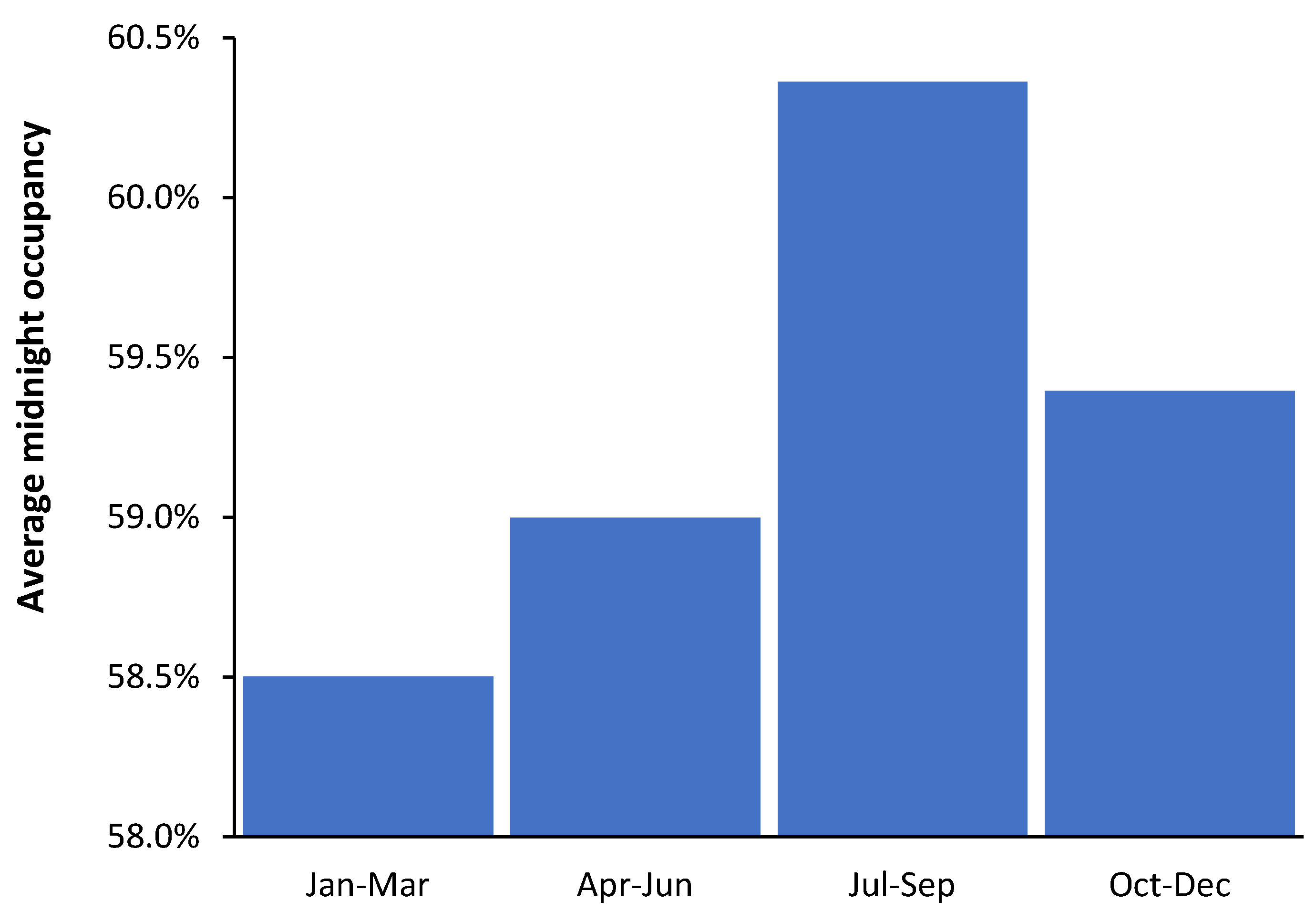

3.3. Seasonality in Births and Bed Demand

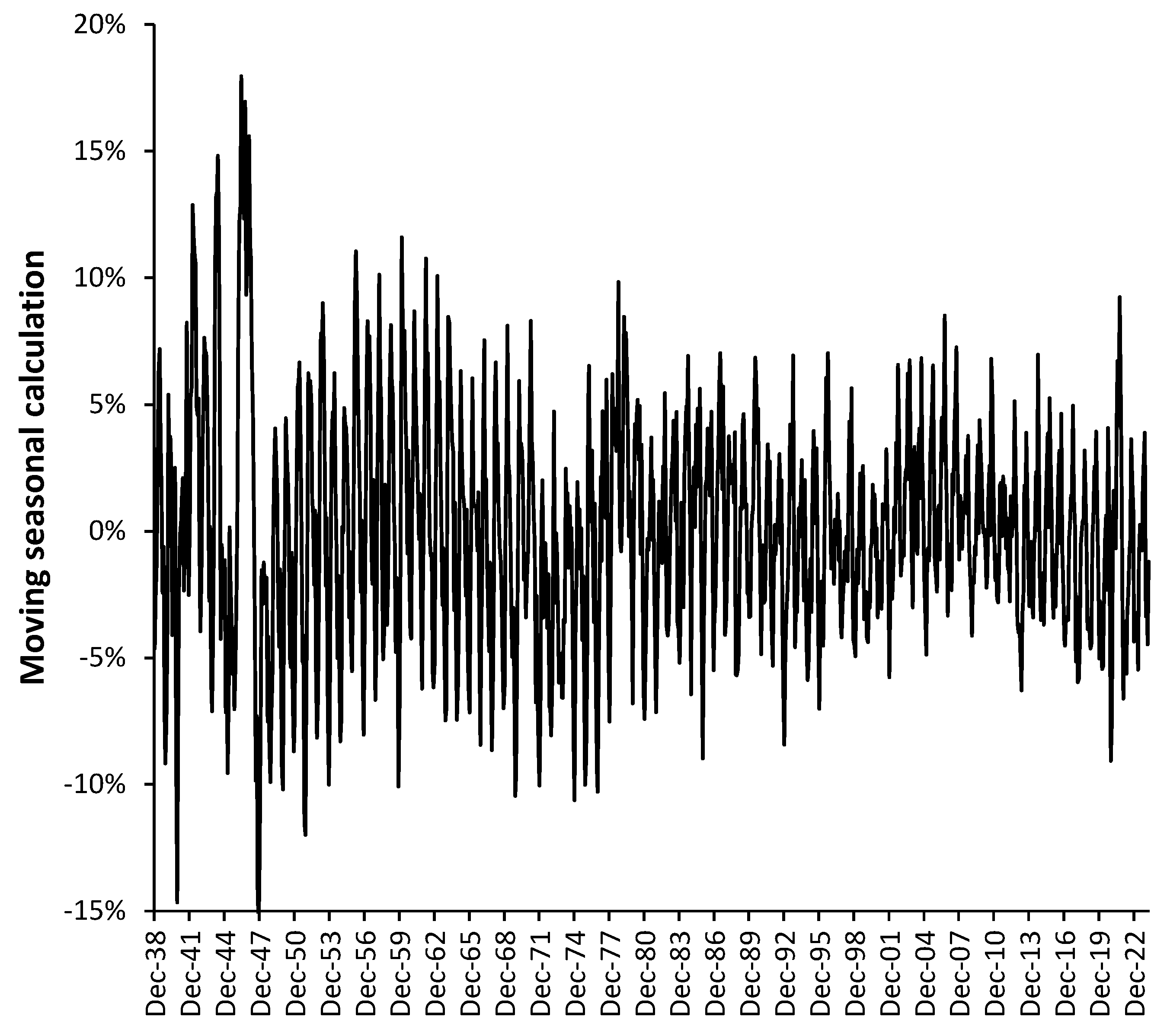

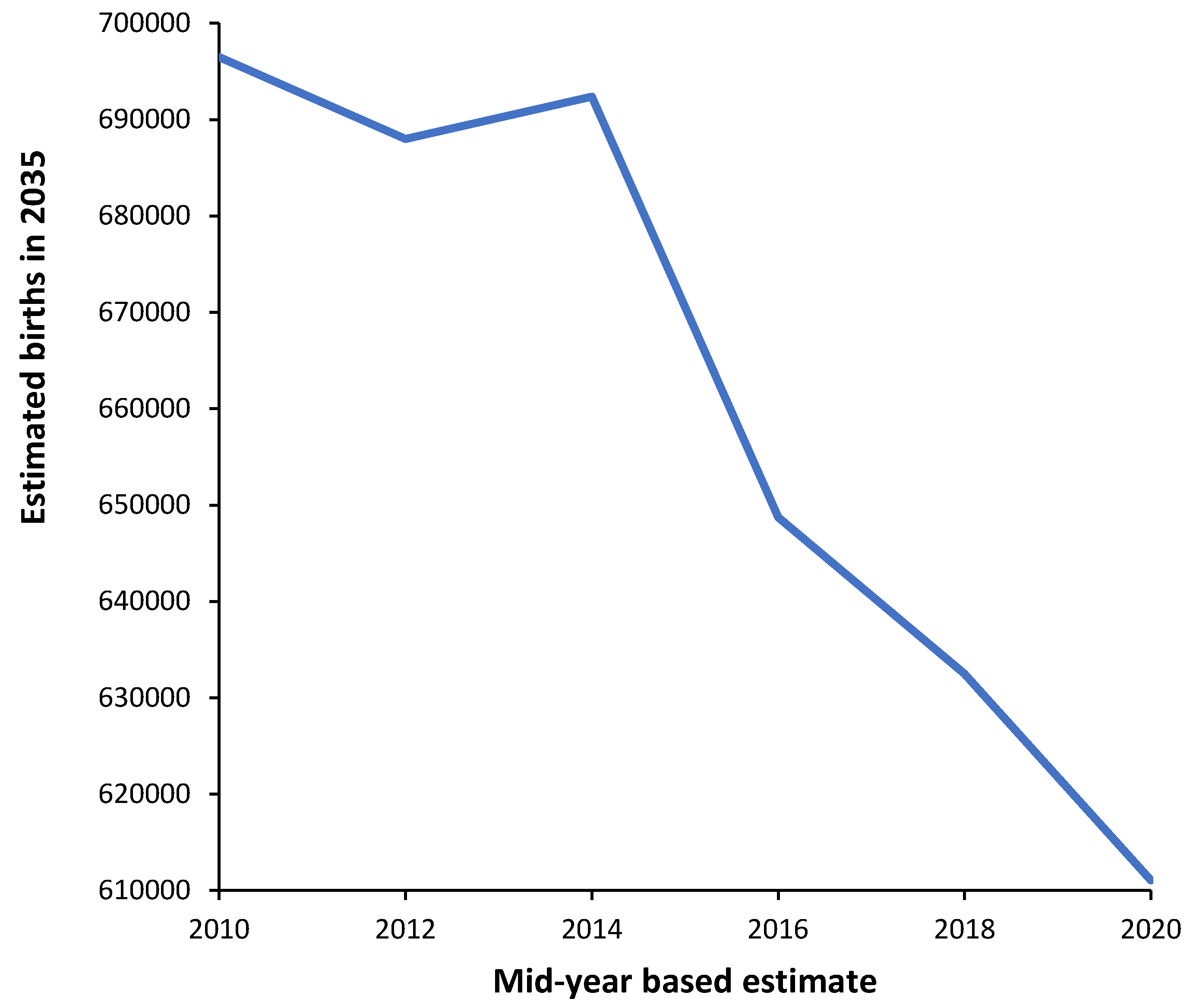

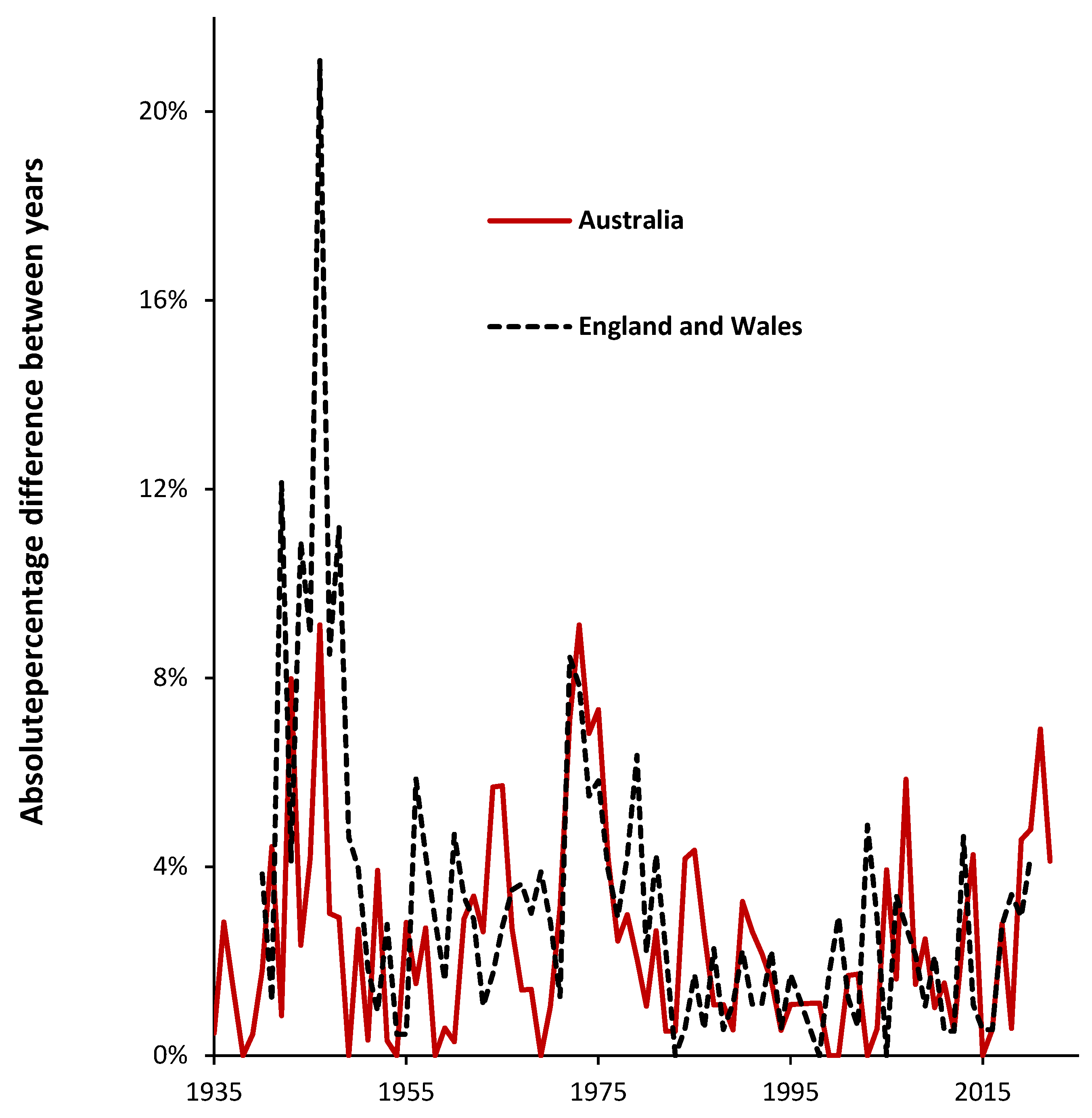

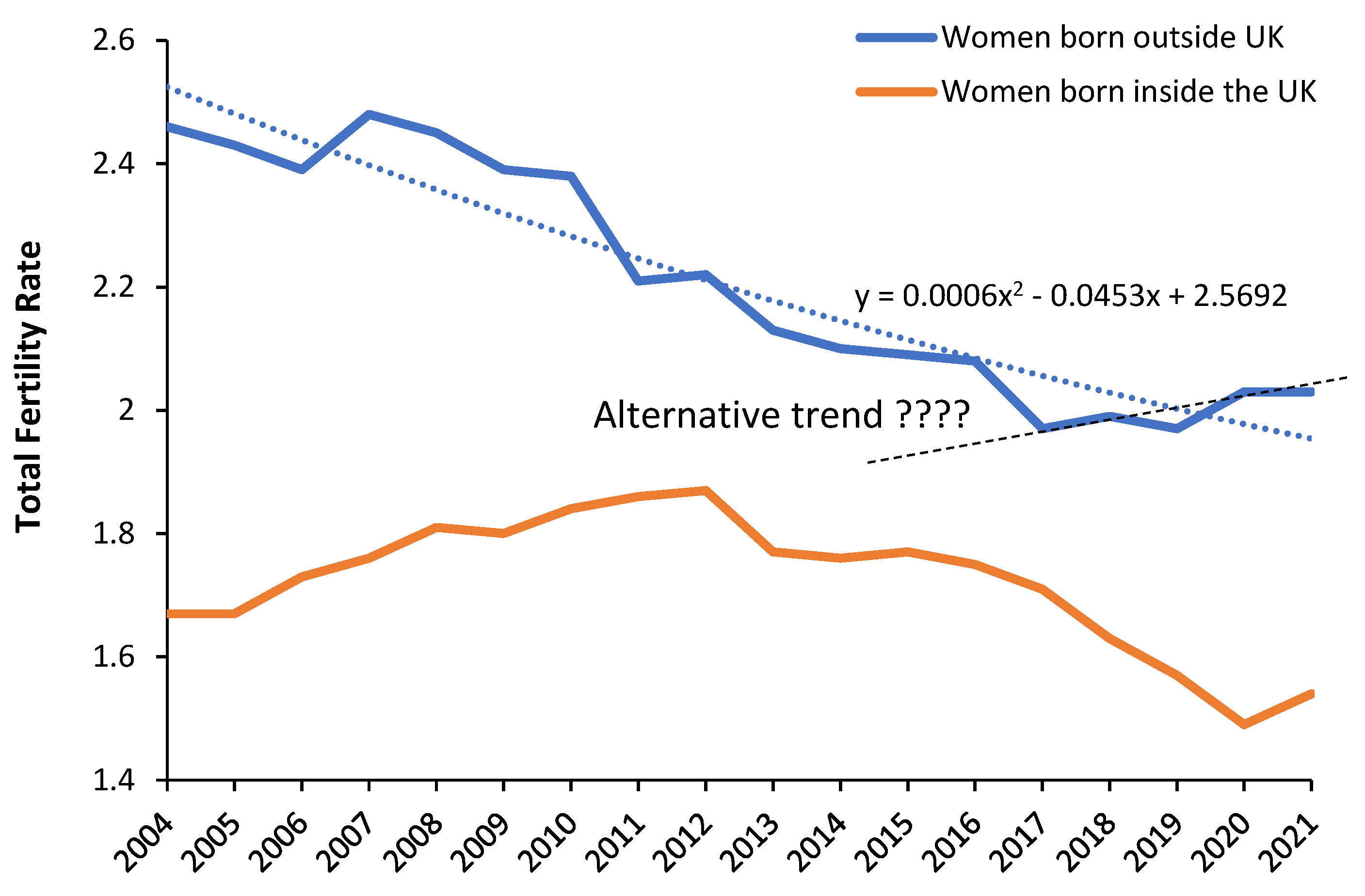

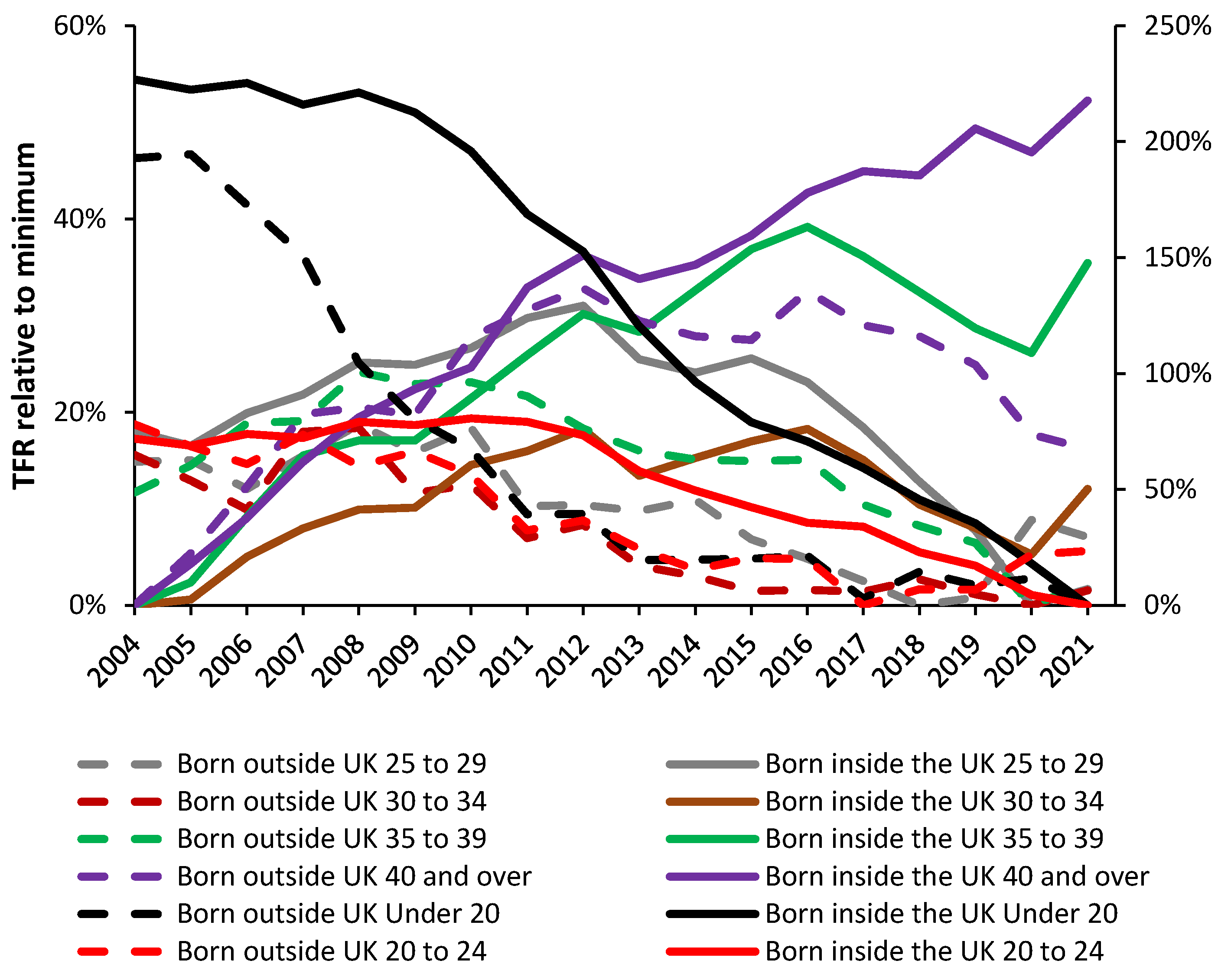

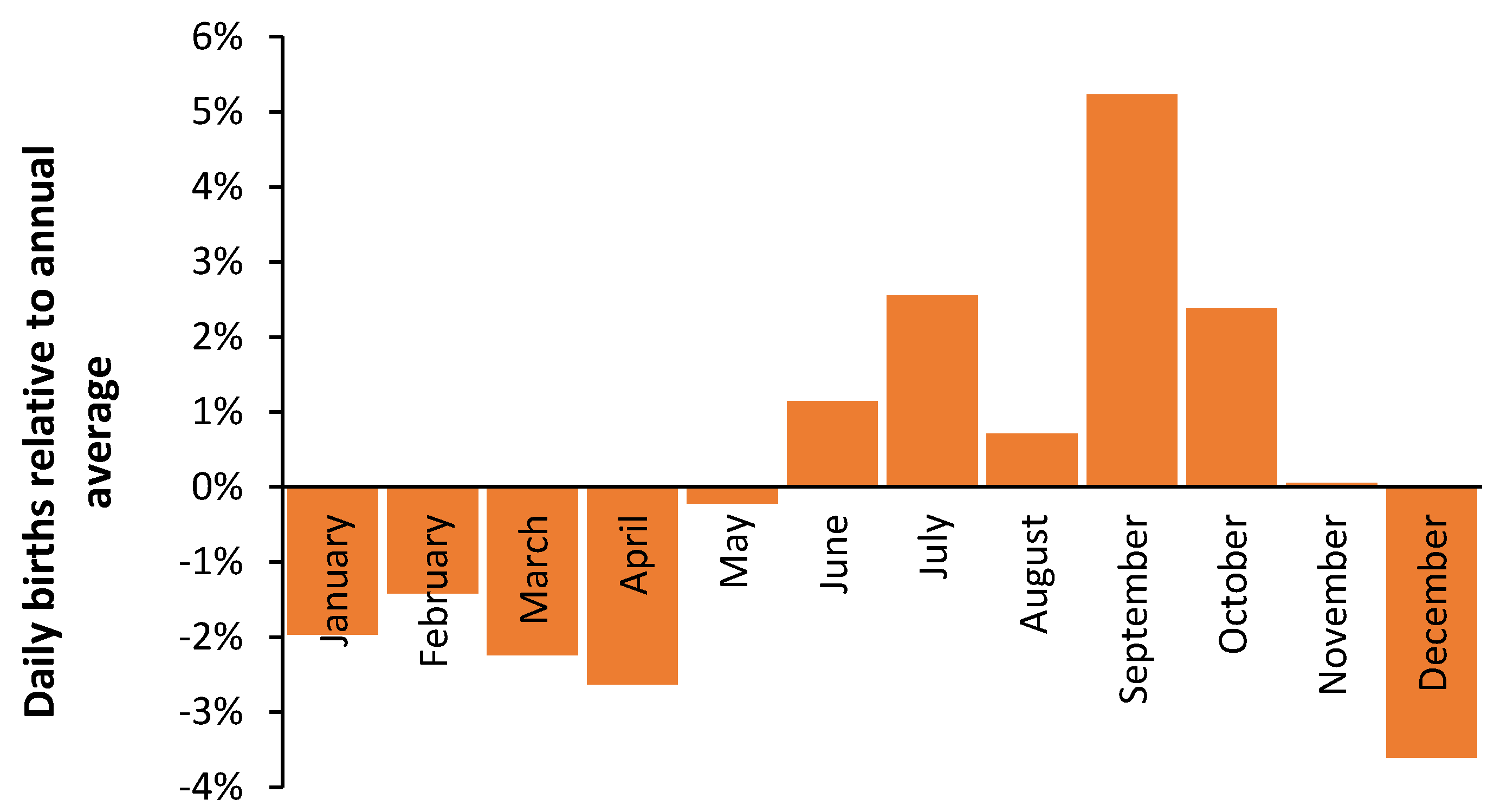

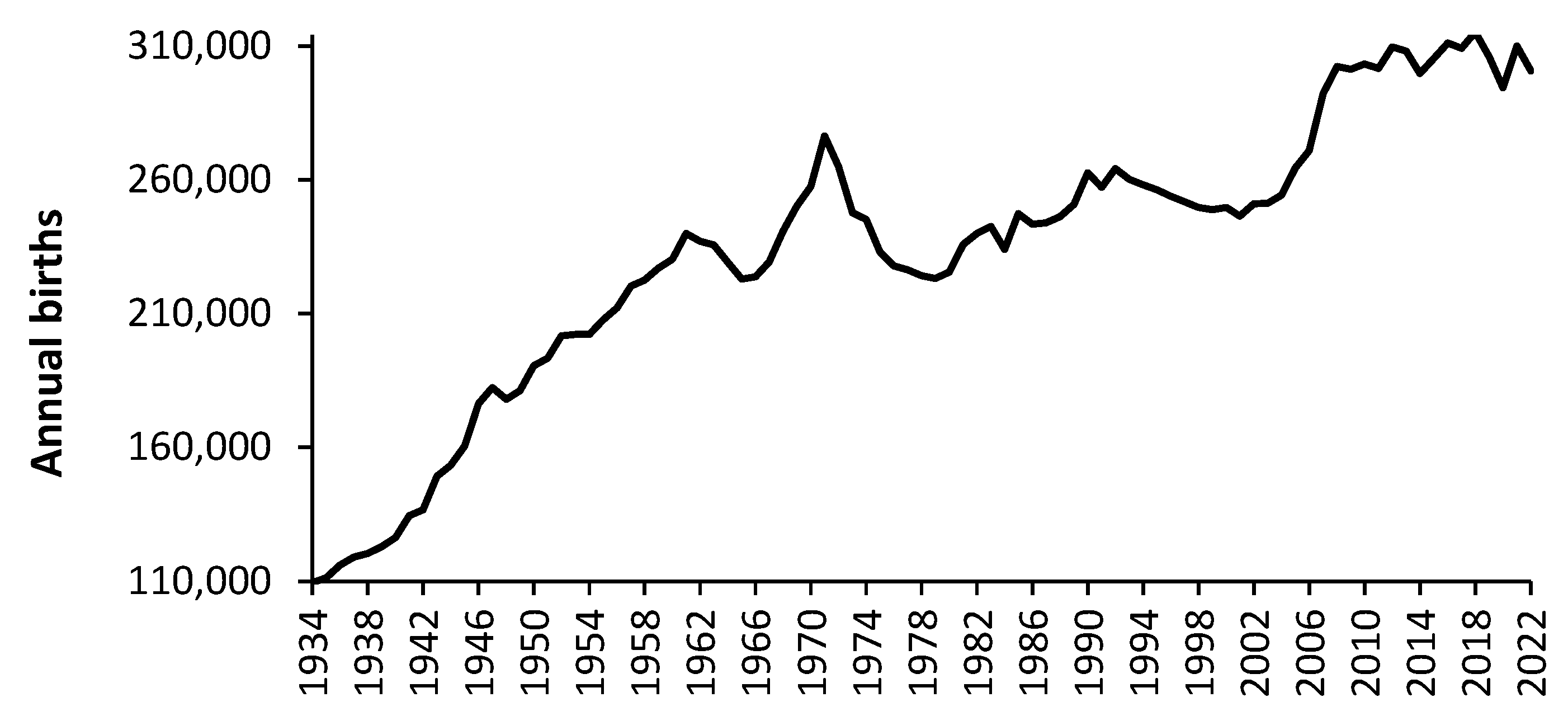

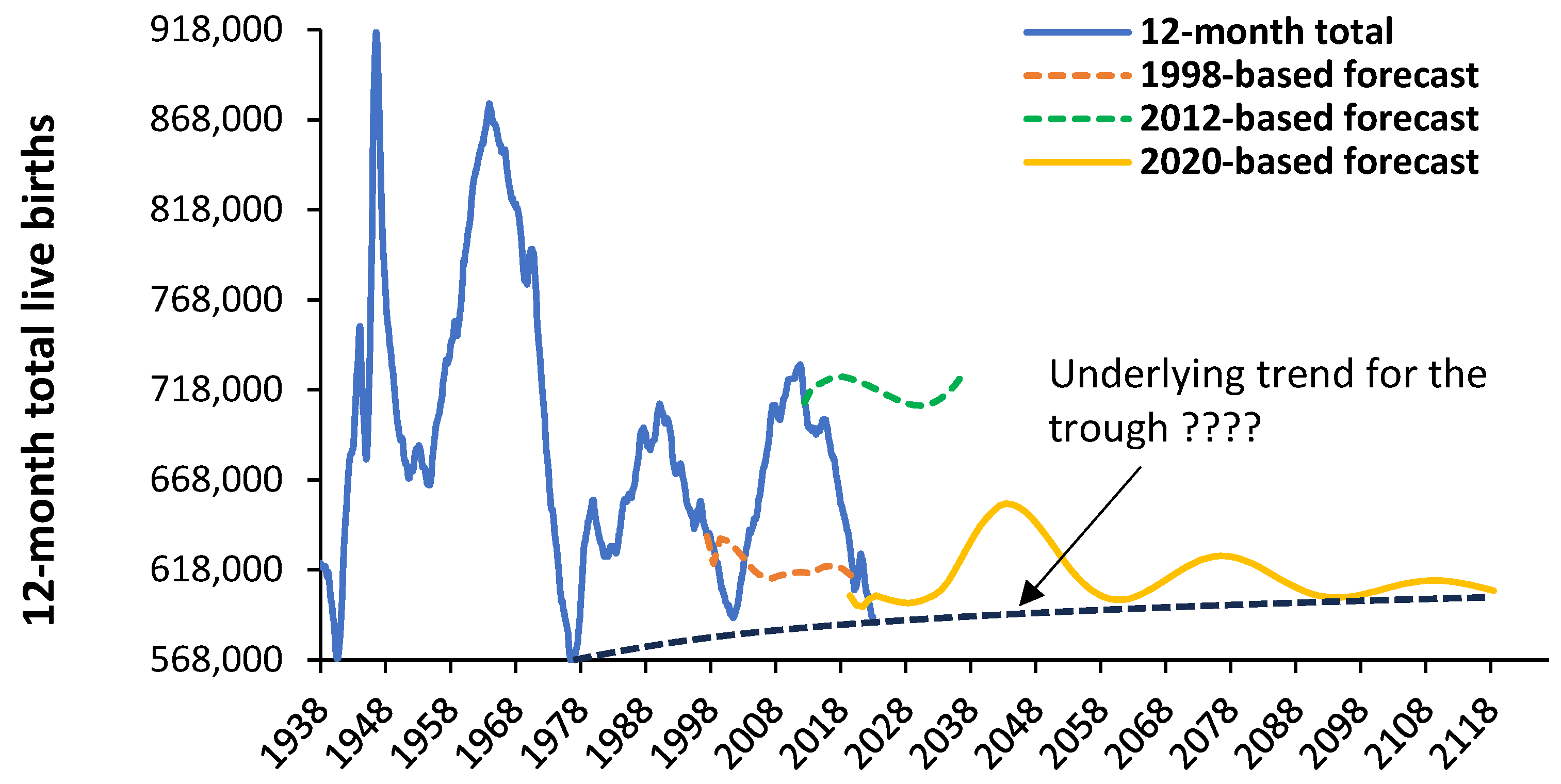

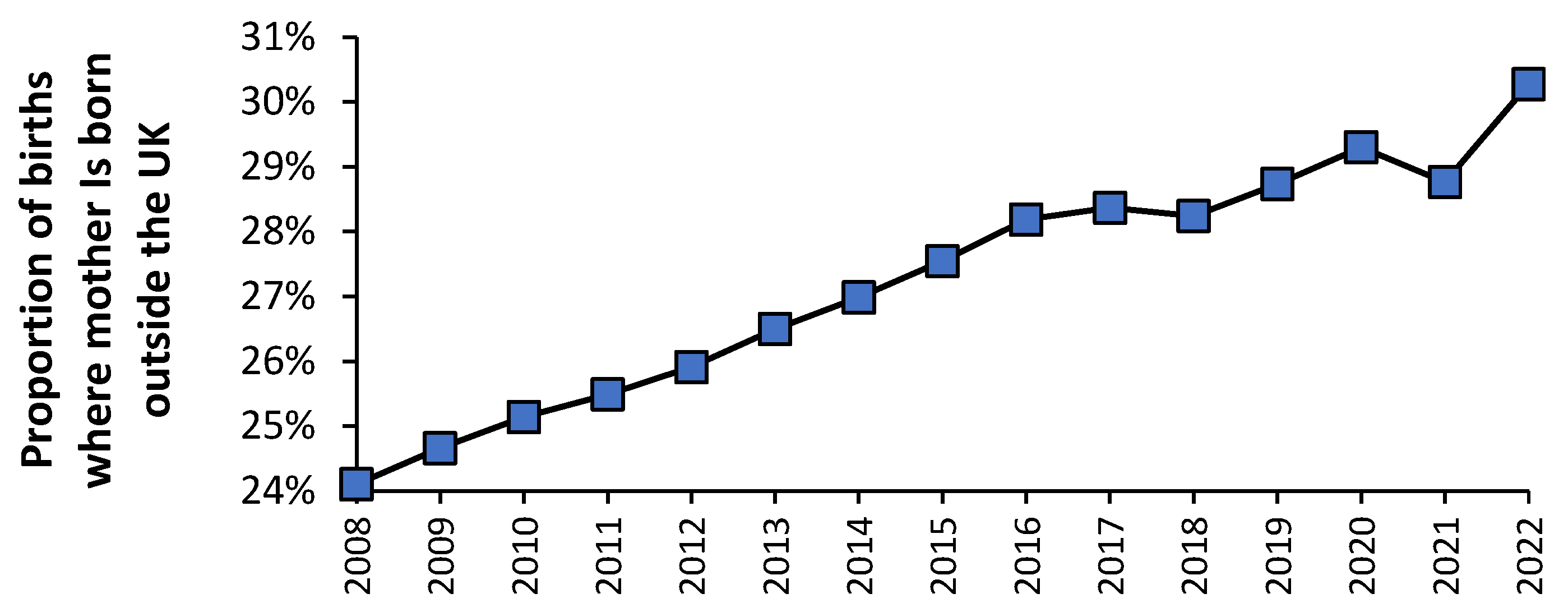

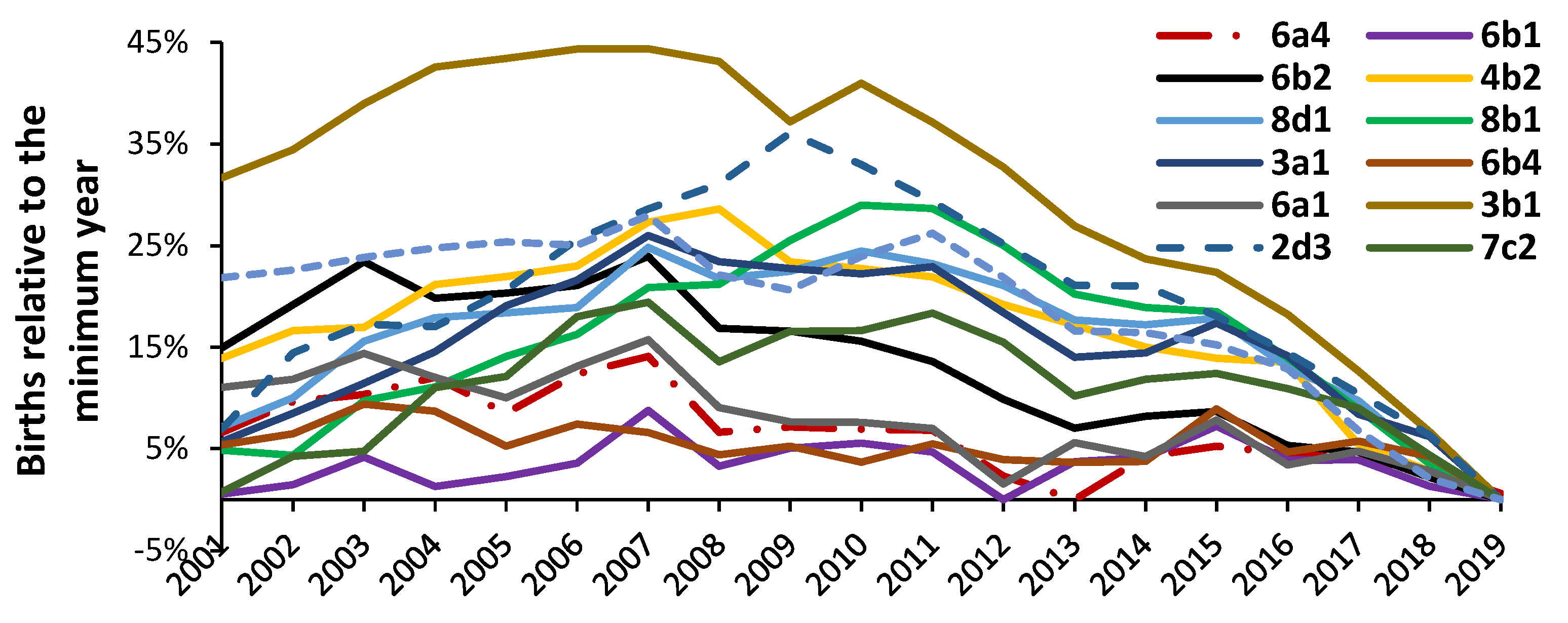

3.4. Forecasting Births

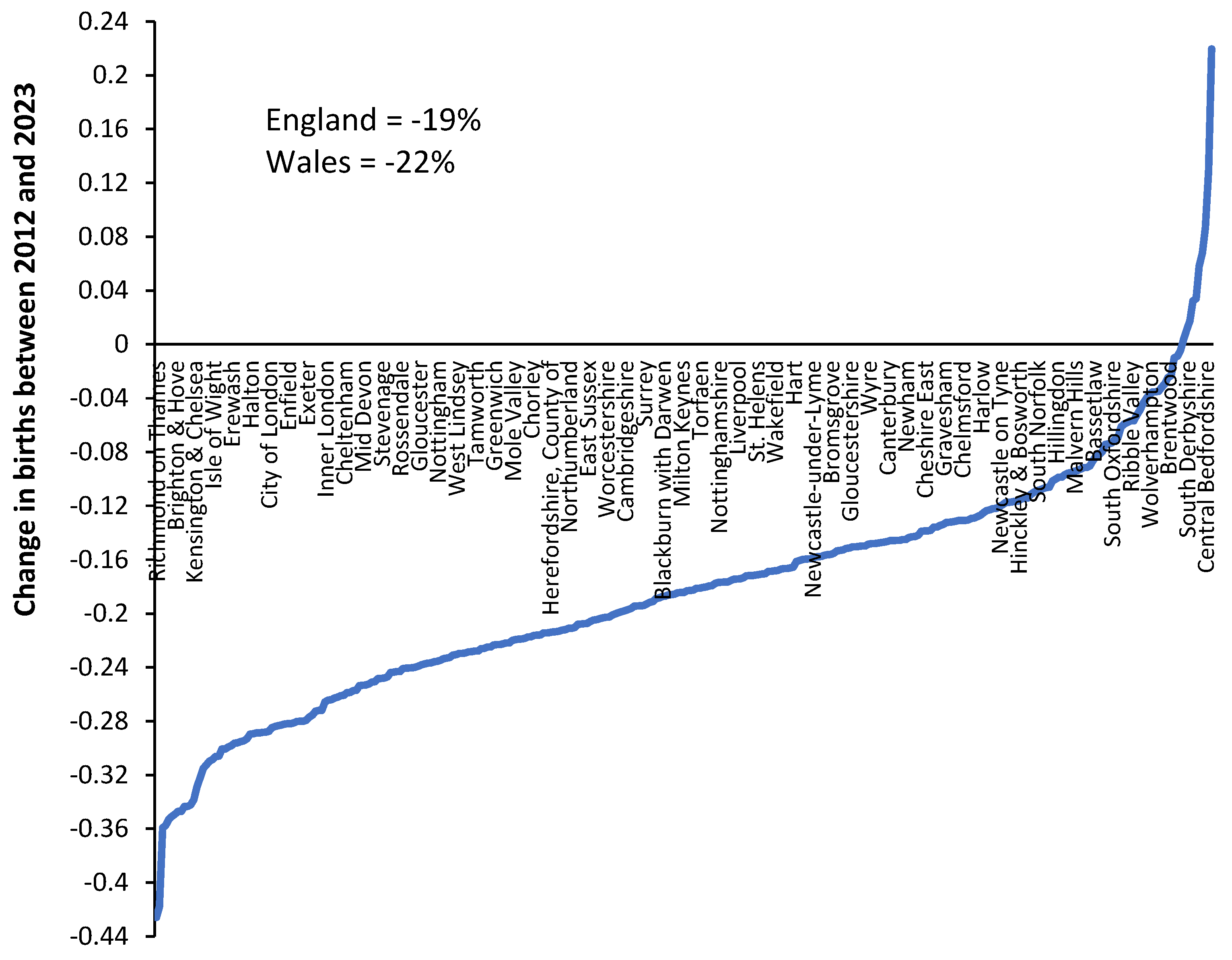

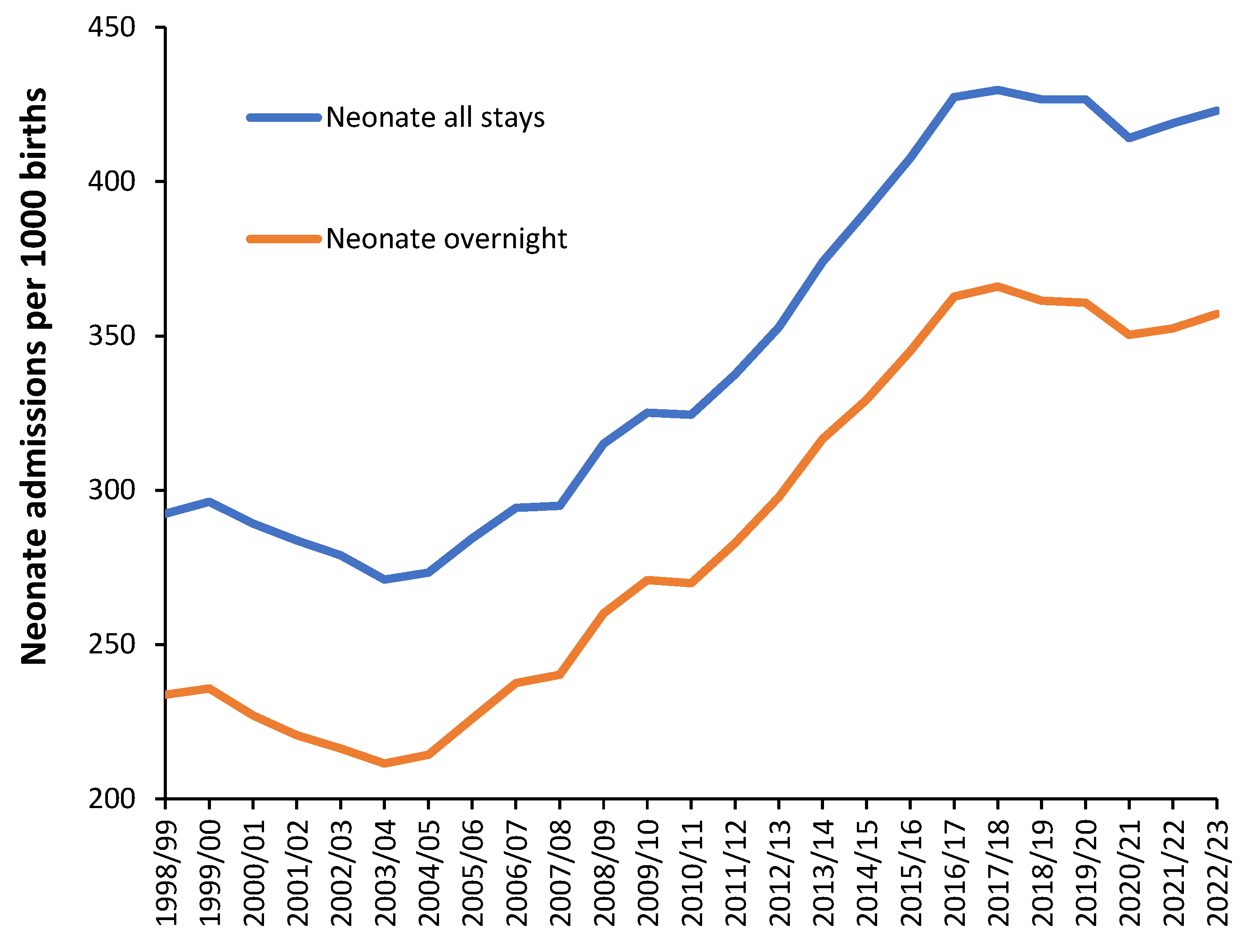

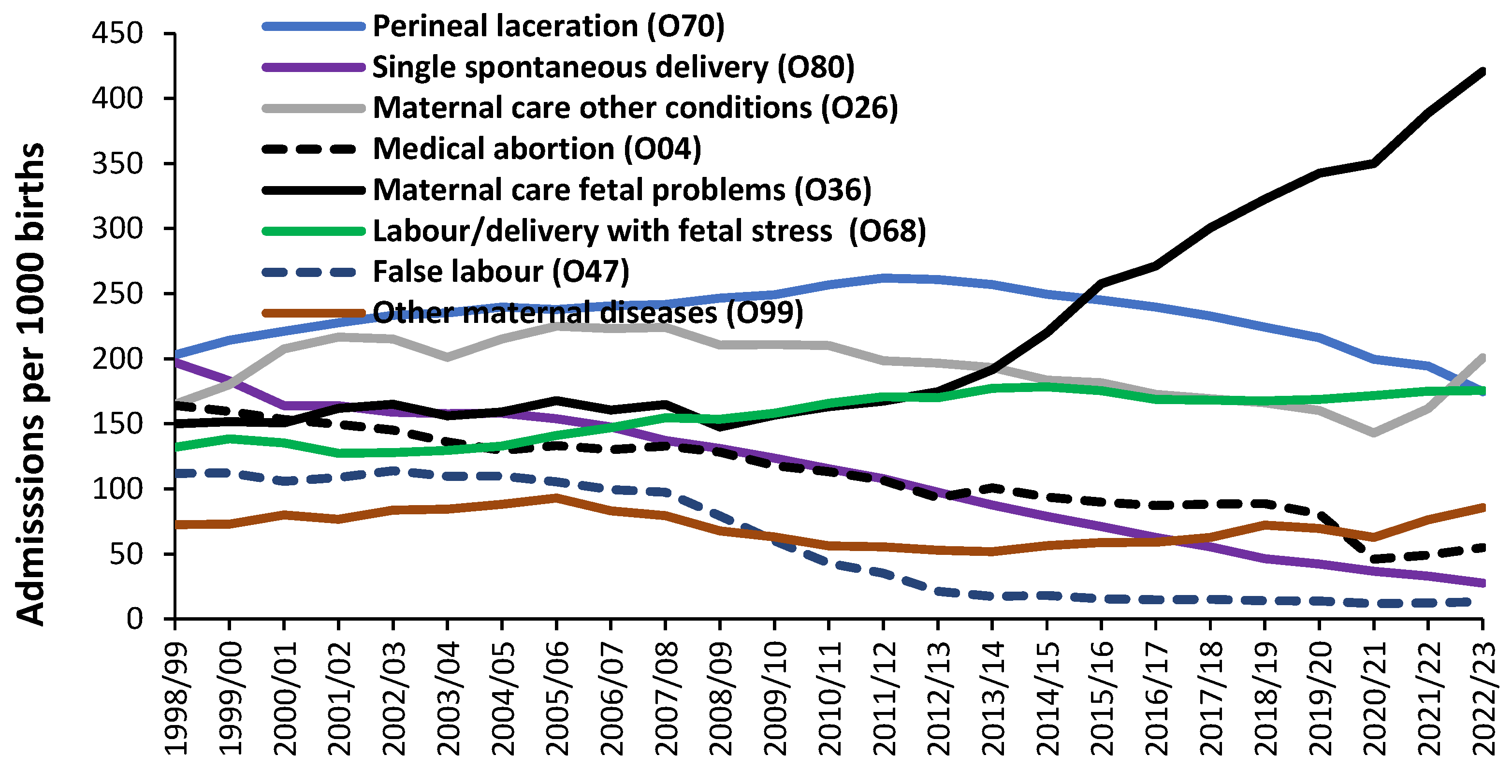

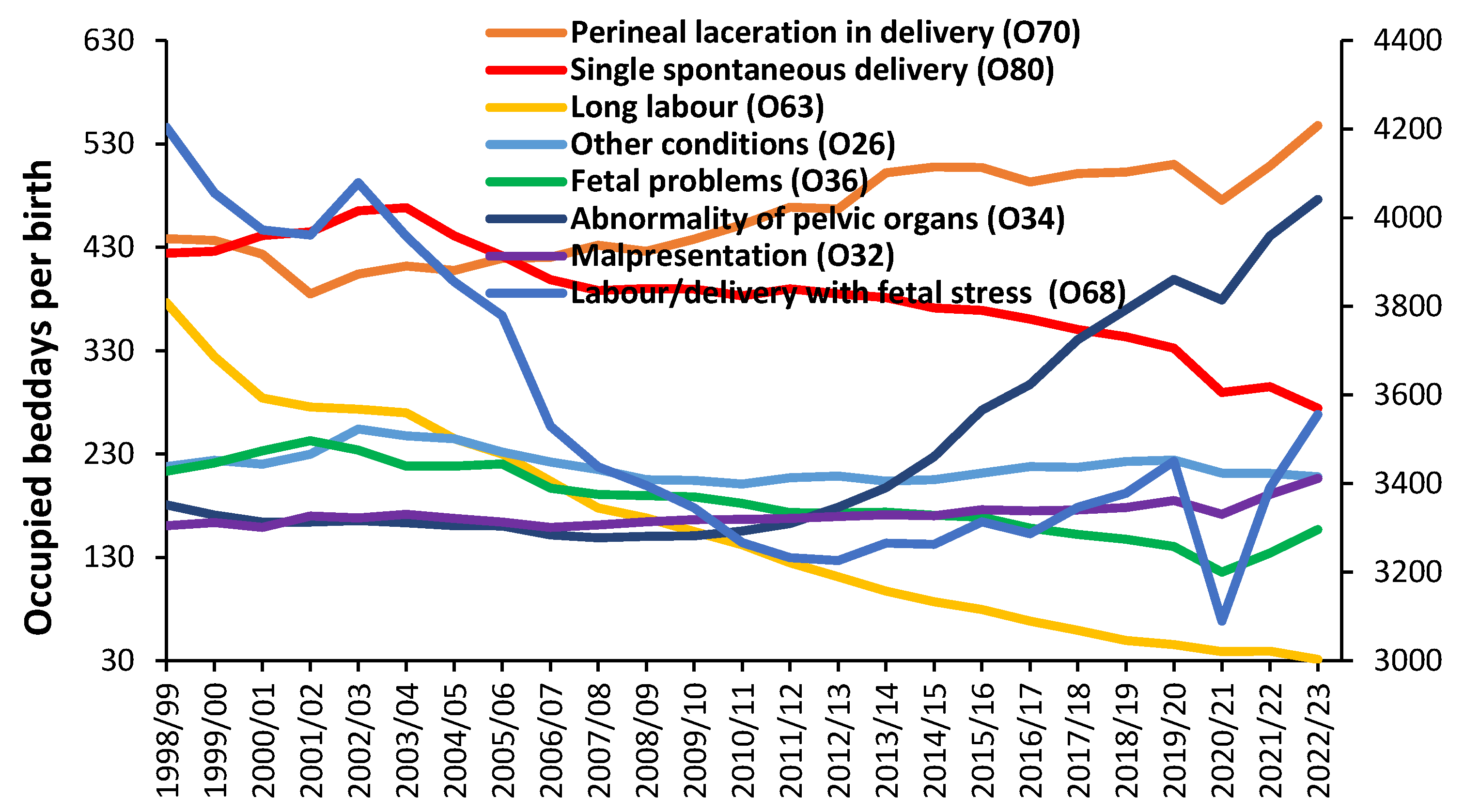

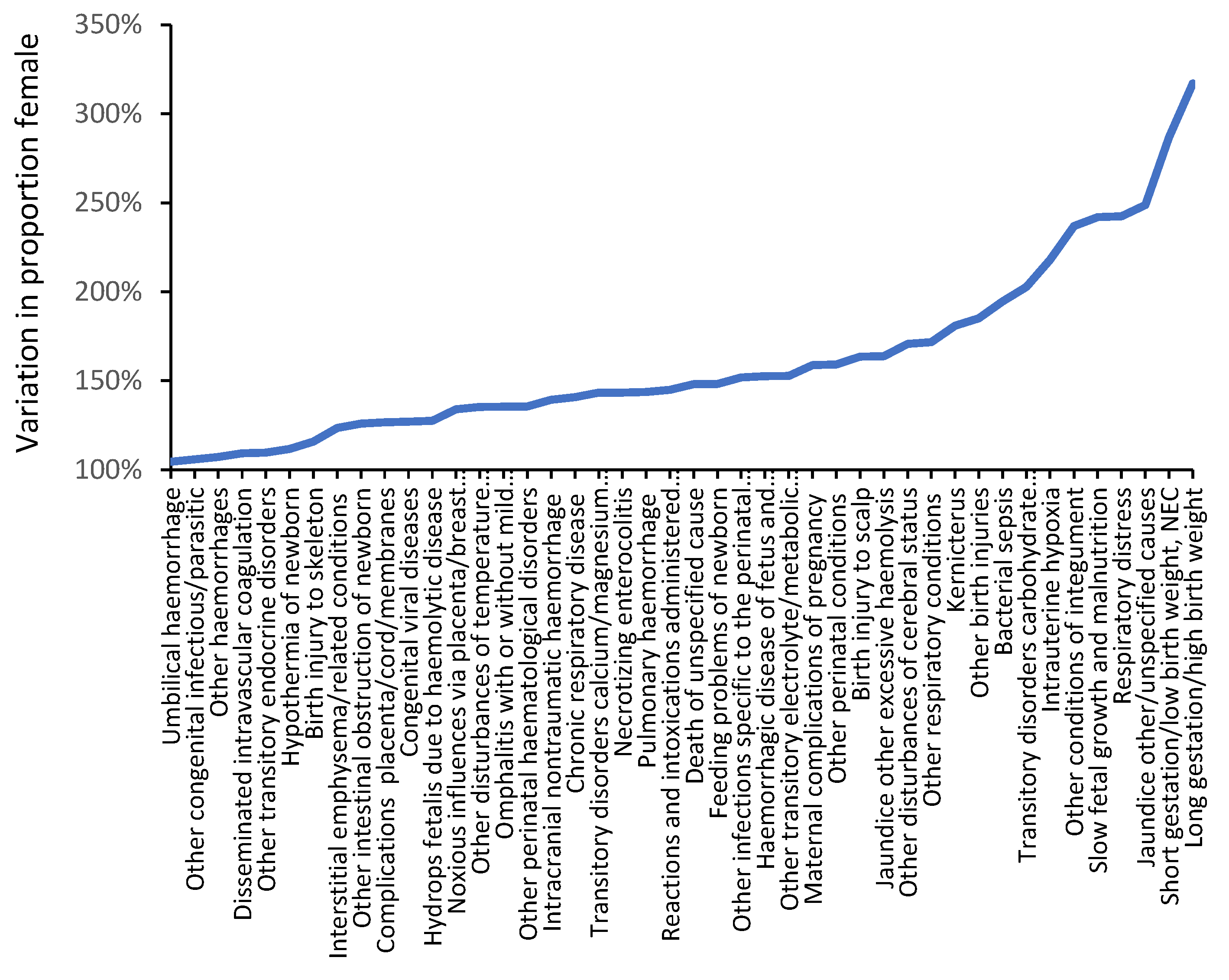

3.5. Trends in Admissions Relating to Pregnancy and Childbirth

3.6. An Impending Maternity Crisis?

3.7. A Survey of Capacity Preparedness in England

- Are they aware that the reported bed occupancy at the obstetric unit is higher than may be expected for their size?

- Has any National or Professional Society guidance ever been published on how to correctly size a maternity unit?

- Do they have any planning documents relating to the choice of the current number of maternity beds?

4. Discussion

4.1. General Issues

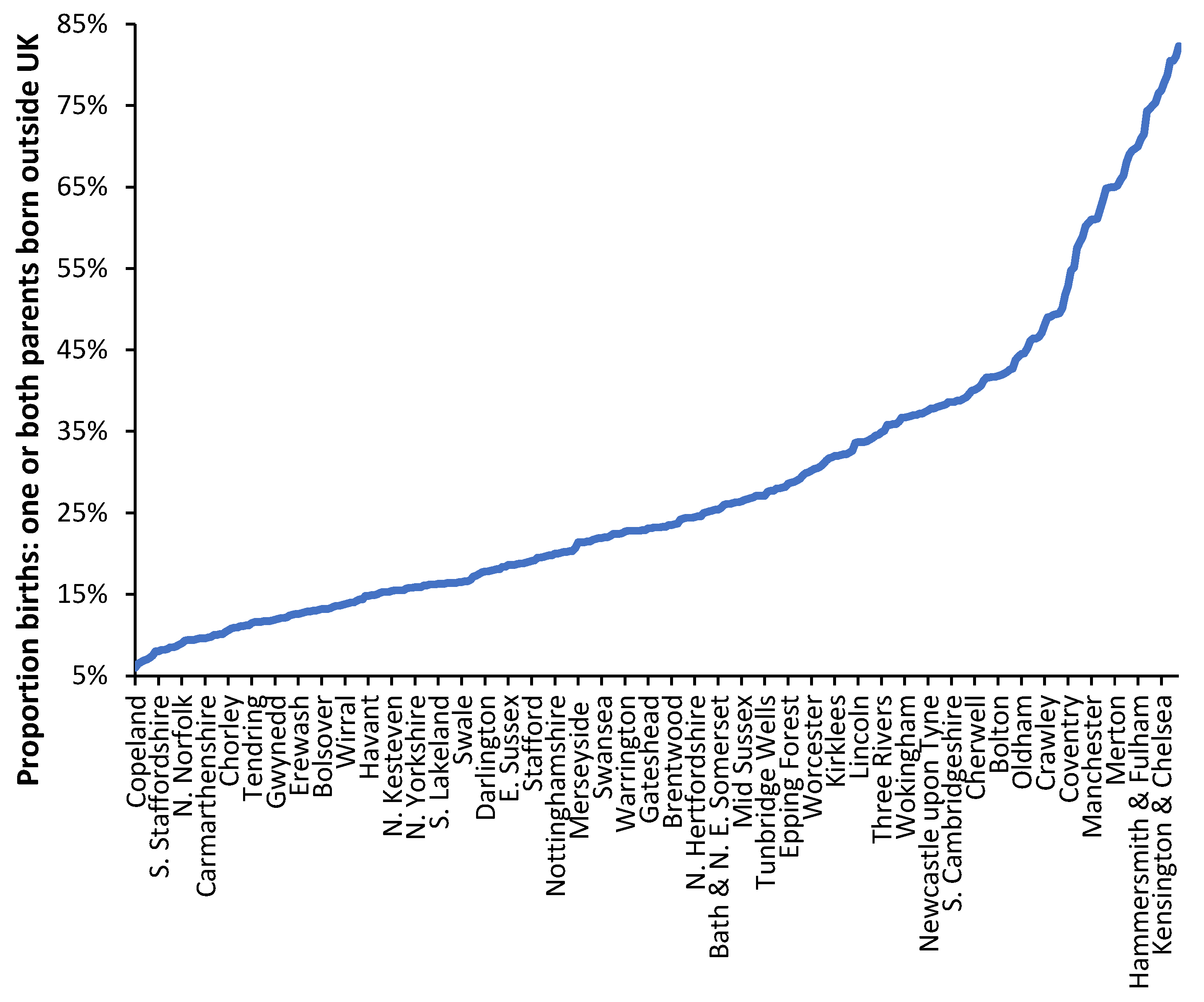

4.2. Forecasting Long-Term Trends in Births

4.3. Seasonality in Births

4.4. 24-Hour and Weekday Cycles in Bed Occupancy

4.5. Lunar and Solar Cycles

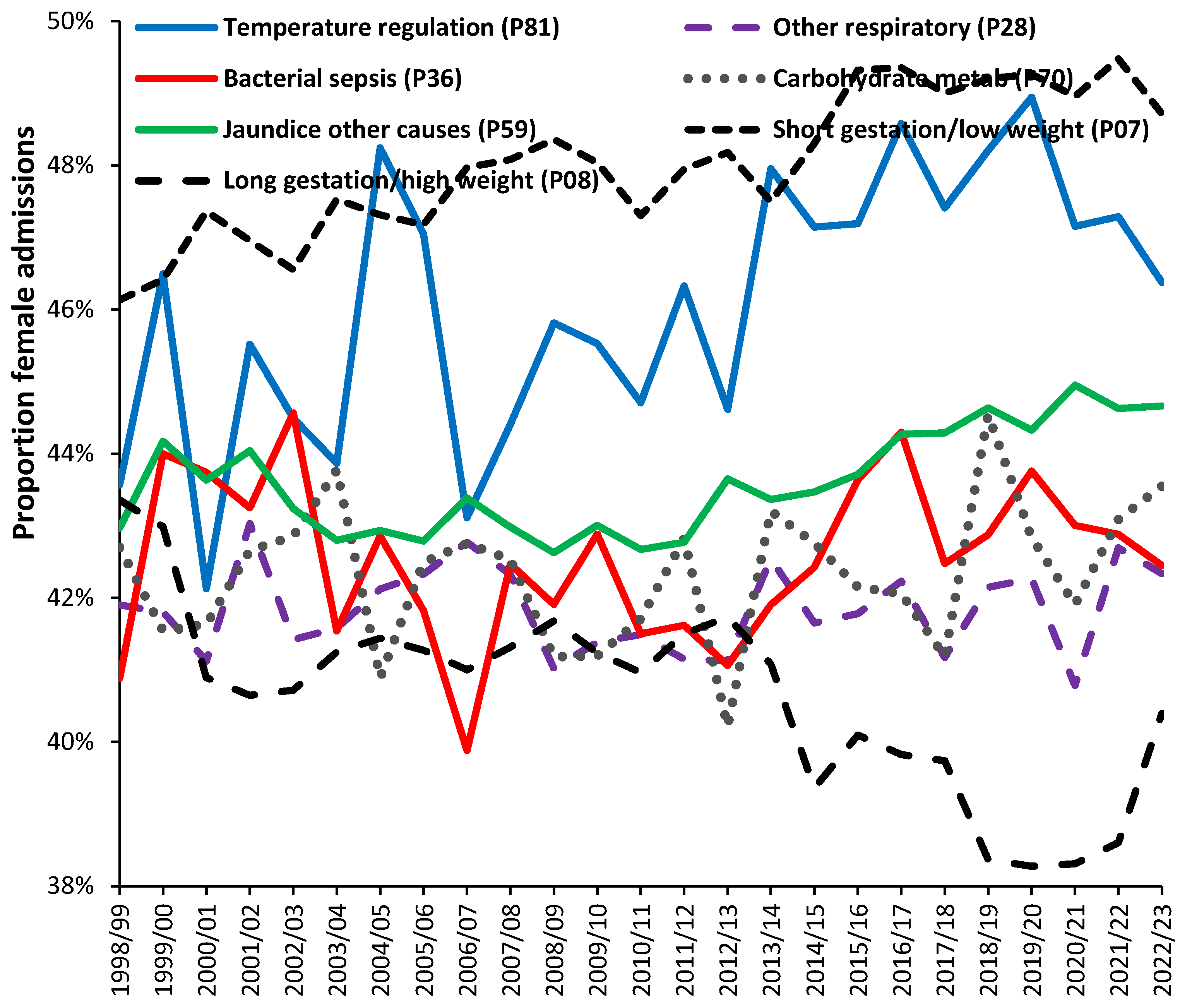

4.6. Infections and Pregnancy

4.7. Risk Factors

4.10. The English NHS National Maternity Review

4.11. Issues of Population Density and Distance

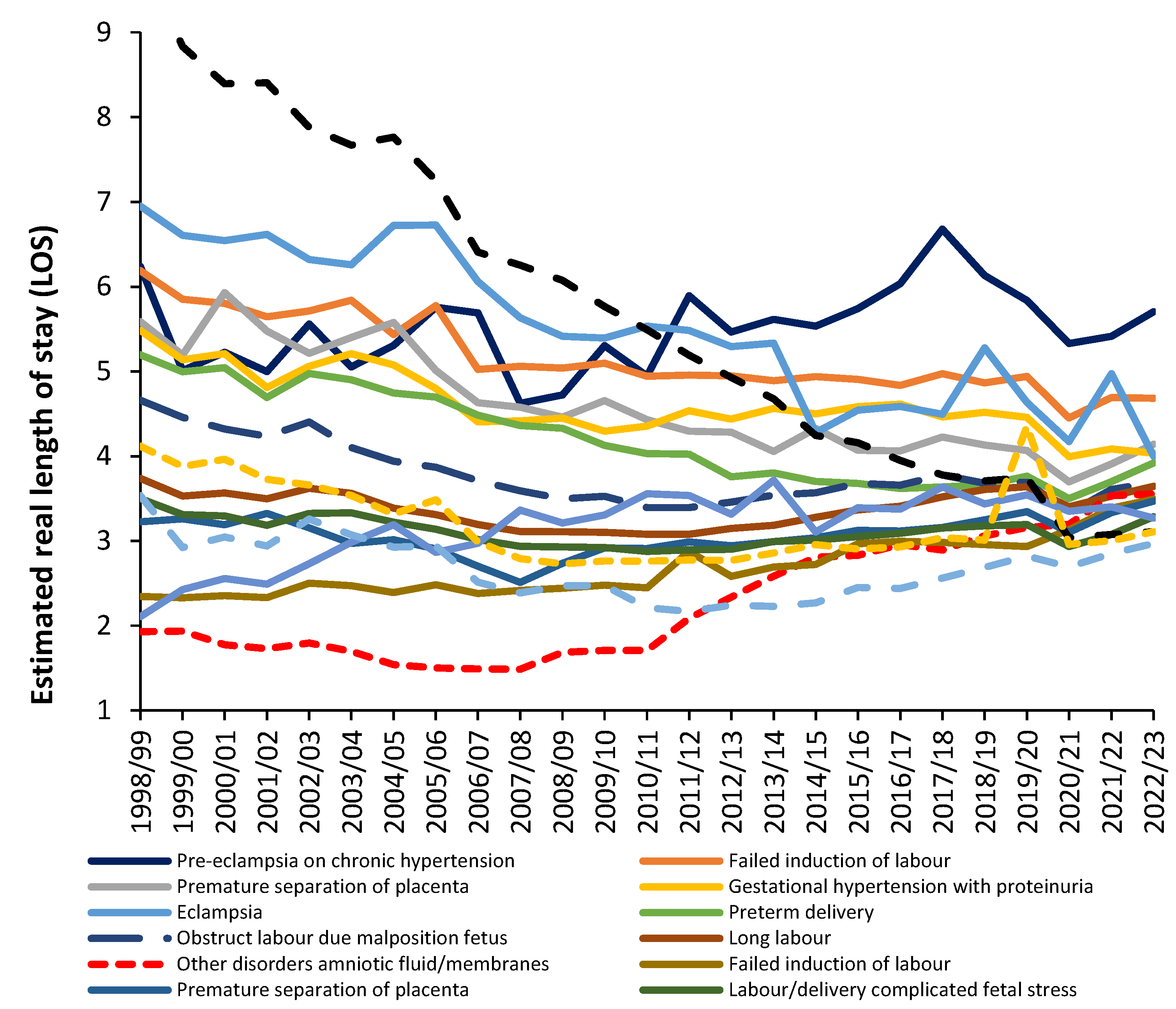

4.12. Does Decreasing Length of Stay (LOS) Actually Reduce Costs

“This is because for both medical and surgical patients, the main costs occur in the first half of the stay when input from staff, investigation, and intervention are at a maximum. Stays in hospital are almost always shortened by reducing lower dependency “cheaper” days, usually in the second half of the stay”. Along similar lines another study noted that “not all hospital days are economically equivalent”[100].

- a.

- How are direct maternity costs allocated based on time? Is time-based costing used?

- b.

- How are wider hospital overhead costs allocated to the maternity department, and would a change in the apportionment method used for each function have a significant effect on the supposed ‘cost’?

4.13. Pitfalls in Benchmarking Length of Stay (LOS) and Costs

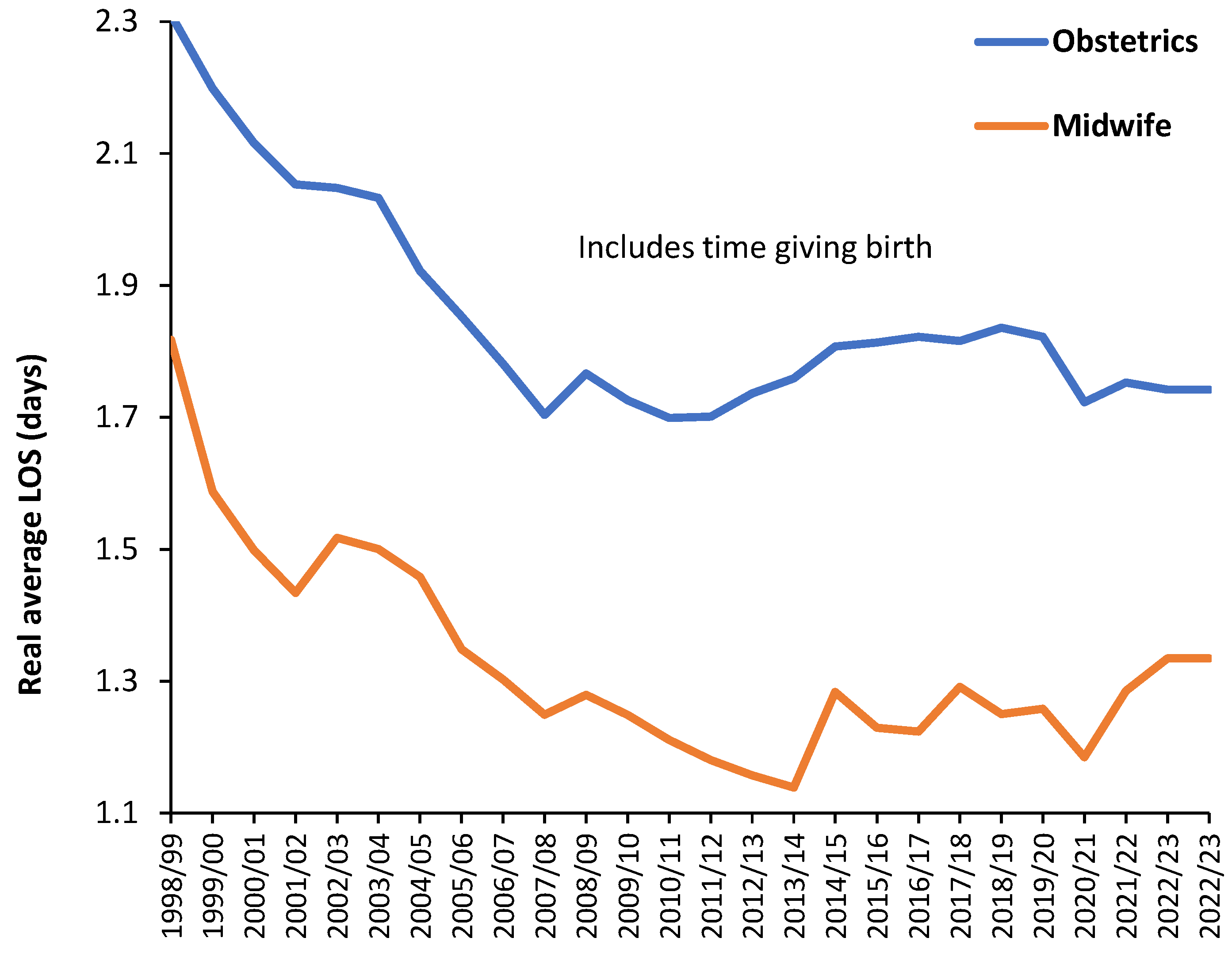

4.14. When Did England Reach the Optimum LOS?

“The hospital stay of the mother and her healthy term newborn infant should be long enough to allow identification of problems and to ensure that the mother is sufficiently recovered and prepared to care for herself and her newborn at home. The LOS should be based on the unique characteristics of each mother-infant dyad, including the health of the mother, the health and stability of the newborn, the ability and confidence of the mother to care for herself and her newborn, the adequacy of support systems at home, and access to appropriate follow-up care in a medical home. Input from the mother and her obstetrical care provider should be considered before a decision to discharge a newborn is made, and all efforts should be made to keep a mother and her newborn together to ensure simultaneous discharge.”[108]

4.15. Matching Staffing with Demand

4.16. Size, Statistical Chaos and Income

4.17. Fair Funding for Maternity Units

4.18. Flexible Staffing to Offset the Efect of Size

4.19. A System-Wide View of Maternity Costs

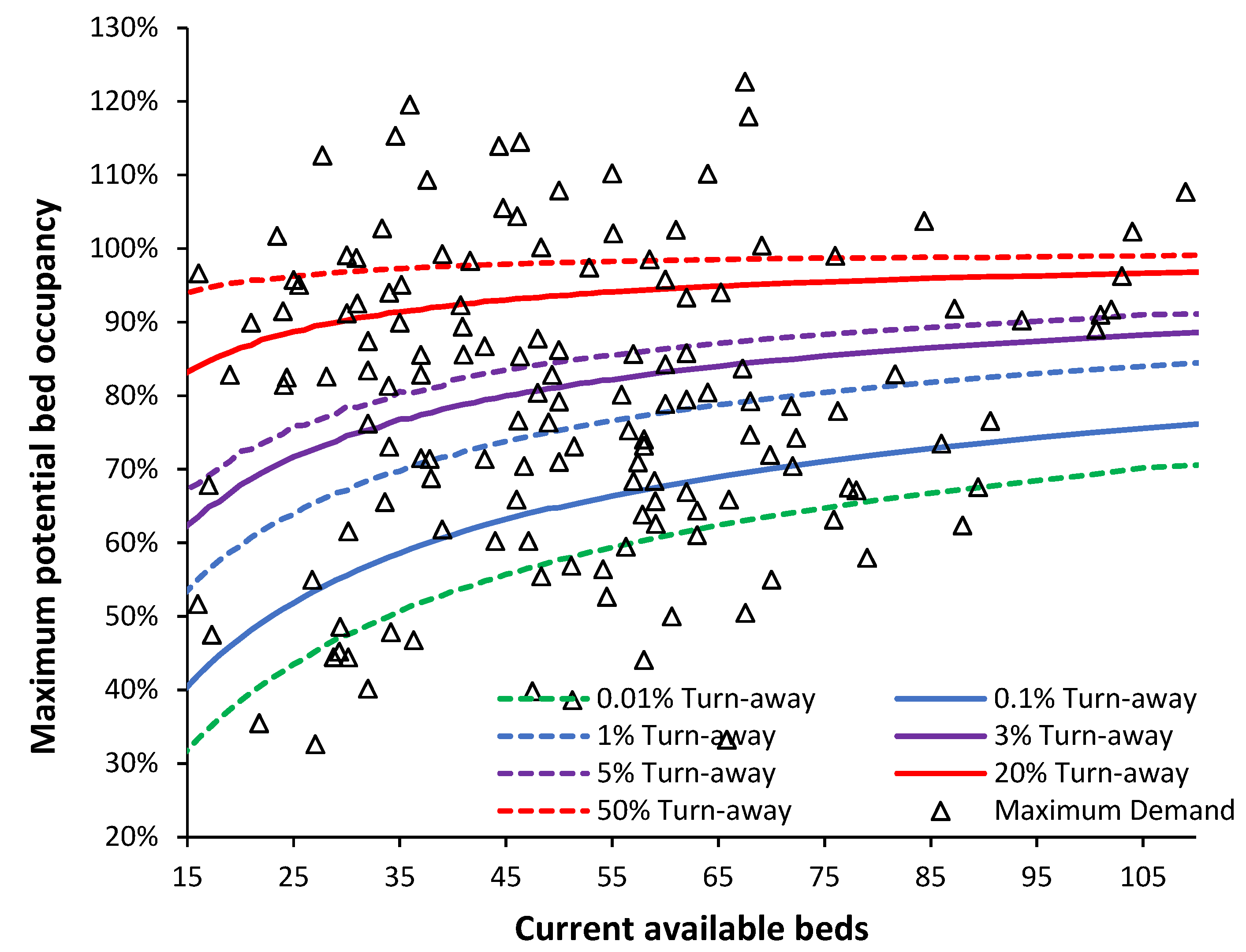

4.20. Key Recommendations

- Government health departments should encourage the use of turn-away for understanding maternity unity capacity preparedness.

- There is reliable evidence that maternity demand is subject to hourly, seasonal and environmental fluctuations implying that the annual average occupancy should ideally be below 0.01% turn-away.

- Any maternity unit with an annual average turn-away greater than 1% must flag this on the hospital risk register and implement plans to correct this situation.

- Research is required to disentangle the effects of turn-away and poor staffing on safety and outcomes in maternity units.

- Maternity units should monitor bed occupancy and associated turn-away hourly throughout the year in the birthing unit, the postpartum maternity unit, any associated maternity (short stay) assessment unit and any midwife-led community units. Past trends in such metrics should also be investigated to determine the local fluctuations in demand and ongoing trends.

- Maternity units should refresh their estimates of future demand every two to three years and compare how actual demand compares with past estimates.

- Government regulators should establish guidelines regarding the maximum acceptable turn-away in maternity units.

- Benchmarking of maternity unit LOS needs to be against nationally agreed levels of quality and safety. High turn-away units should be excluded from the derivation of such benchmarking

- To compare costs on a like-for-like basis the cost per HRG/DRG requires identification of the separate components of cost, namely, depreciation on capital (buildings and equipment), organization wide apportioned costs for all the non-patient facing departments, and the direct costs of care. The direct costs of care per birth will be higher as the unit gets smaller and, on this basis, small midwife-led low risk units are unlikely to be cost effective—although they may be considered desirable by mothers.

- In England, which uses the HRG tariff, all maternity units should receive extra funding based on size to mitigate the unavoidable higher costs relating to size.

4.21. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country of birth of mother | 2001 TFR | 2011 TFR | Country of birth of mother | 2001 TFR | 2011 TFR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| North Africa | 4.6 | 3.9 | New EU | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Pakistan | 4.7 | 3.8 | Central Asia | 2.7 | 2.2 |

| Western Africa | 2.7 | 3.3 | Poland | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| Bangladesh | 3.9 | 3.3 | European Union | 1.6 | 1.9 |

| Central Africa | 5.0 | 3.1 | Non-EU Europe | 2.7 | 1.9 |

| Southern Asia | 3.6 | 3.0 | United Kingdom | 1.6 | 1.8 |

| Eastern Africa | 2.3 | 2.6 | Southern Africa | 1.4 | 1.8 |

| Middle East | 3.1 | 2.6 | Central America | 1.7 | 1.8 |

| Sri Lanka | 3.5 | 2.6 | South America | 2.3 | 1.8 |

| Oceania (excl Australia) | 2.0 | 2.6 | North America | 1.7 | 1.7 |

| India | 2.2 | 2.4 | Eastern Asia | 1.1 | 1.5 |

| Caribbean | 2.8 | 2.3 | South East Asia | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Australasia | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| Function |

|---|

| Chief Executive, Chairman, Non-executive directors |

| Human Resources (Personnel, recruitment) |

| Media and Communications |

| Procurement |

| Women’s and Children’s Management |

| Estates and Facilities (buildings and grounds, maintenance) |

| Finance, annual accounts, payroll, debt recovery, etc |

| Information Technology and supporting software |

| Information Management, monthly reports, etc |

| Medical Records (non-computerized) |

| Strategy and Planning |

| Portering |

| Patient transport |

| Pathology (blood biochemistry, microbiology, etc) |

| Radiology |

| Medical Instrumentation |

| Intensive Care |

| Housekeeping (cleaning, etc) |

| Health and Safety |

| Infection Control |

| Medical Illustration |

| Library |

| Capital costs via depreciation of buildings and equipment |

References

- Jones, R. Addressing the Knowledge Deficit in Hospital Bed Planning and Defining an Optimum Region for the Number of Different Types of Hospital Beds in an Effective Health Care System. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, R. A New Approach for Understanding International Hospital Bed Numbers and Application to Local Area Bed Demand and Capacity Planning. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2024, 21, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Bruin, A.M.; Bekker, R.; van Zanten, L.; Koole, G.M. Dimensioning hospital wards using the Erlang loss model. Ann. Oper. Res. 2010, 178, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, G.; Lim, A.J.; Quinn, B.; et al. Obstetric operating room staffing and operating efficiency using queueing theory. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023, 23, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sülz, S.; Fügener, A.; Becker-Peth, M.; Roth, B. The potential of Patient-based nurse staffing—a queuing theory application in the neonatal intensive care setting. Health Care Manag Sci. 2024, 27, 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, N.; Reamer, C.; Reynolds, T.; Howell, L.; Moldenhauer, J.; Day, T. Capacity Planning for Maternal–Fetal Medicine Using Discrete Event Simulation. Amer J Perinatology. 2014, 32, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehlivan, C.; Augusto, V.; Xie, X.; Crenn-Hebert, C. Multi-period capacity planning for maternity facilities in a perinatal network: A queuing and optimization approach, IEEE International Conference on Automation Science and Engineering (CASE), Seoul, Korea (South), 2012, pp. 137-142. [CrossRef]

- Ramalhoto, M. Erlang’s Formulas. In: Lovric, M. (eds) International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science.2011. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Joranger, P.; Huitfeldt, A.S.; Bernitz, S.; et al. Cost minimisation analyses of birth care in low-risk women in Norway: a comparison between planned home birth and birth in a standard obstetric unit. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024, 24, 1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzybowski, S.; Stoll, K.; Kornelsen, J. Distance matters: a population based study examining access to maternity services for rural women. BMC Health Serv Res 2011, 11, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Bed availability and occupancy—KH03. Available online: Statistics » Bed Availability and Occupancy—KH03 (england.nhs.uk) (Accessed on 19 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Northern Ireland Department of Health. Hospital statistics: inpatient and day case activity 2023/24. Available online: hs-inpatient-hts-tables-23-24.xlsx (live.com) (Accessed on 12 October 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. Births, Australia. Available online: Births, Australia, 2022 | Australian Bureau of Statistics (abs.gov.au) (Accessed on 13 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Office for National Statistics. Births in England and Wales: Summary Tables. Available online: Births in England and Wales: summary tables–Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk) (Accessed on 13 September, 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Office for National Statistics. Birth characteristics in England and Wales. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthcharacteristicsinenglandandwales/2022 (accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. Births in England and Wales: 2020. Available online: Births in England and Wales—Office for National Statistics) (Accessed on 21 October 2024) MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Office for National Statistics Vital statistics in the, U.K. Available online: Vital statistics in the UK: births, deaths and marriages—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. Population projections incorporating births, deaths and migration for regions and local authorities. Available online: Population projections incorporating births, deaths and migration for regions and local authorities: Table 5—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 13 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Office for National Statistics. Live births by output area, England and Wales: mid-year periods (1 July to 30 June) 2001 to 2020. Available online: Live births by output area, England and Wales: mid-year periods (1 July to 30 June) 2001 to 2020—Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk) (Accessed on 13 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Office for National Statistics. 2011 OAC clusters and names Available online: Datasets—Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk) (Accessed on 13 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- NHS England. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity. Available online: Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity—NHS England Digital (Accessed on 16 October 2024) MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Grace, K. Considering climate in studies of fertility and reproductive health in poor countries. Nat Clim Chang. 2017, 7, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Museum Australia. Postwar immigration drive. Available online: Postwar immigration drive | National Museum of Australia (nma.gov.au) (Accessed on 27 September, 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Migration Watch, U.K. Youth Unemployment and Immigration from the A8 Countries. January 2012. Available online: MW247 : Youth Unemployment and Immigration from the A8 Countries | Migration Watch UK (Accessed on 27 September 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Liao, P.; Dollin, J. Half a century of the oral contraceptive pill: historical review and view to the future. Can Fam Physician. 2012, 58, e757–60. [Google Scholar]

- Office for National Statistics. Parents’ country of birth. Available online: Parents’ country of birth—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. About the area classifications. Available online: About the area classifications—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 29 October 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. Maps. Available online: Maps—Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk) (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

- World Health Organization. Obesity. Available online: Obesity (who.int) (Accessed on 19 October 2024).

- Creanga, A.; Catalano, P.; Bateman, B. Obesity in pregnancy. New England Journal of Medicine, 2022, 387, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.; Freaney, P.; Perak, A.; Greenland, P.; Lloyd-Jones, D.; Grobman, W.; Khan, S. Trends in prepregnancy obesity and association with adverse pregnancy outcomes in the United States, 2013 to 2018. J Amer Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e020717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubens, M.; Ramamoorthy, V.; Saxena, A.; McGranaghan, P.; Veledar, E.; Hernandez, A. Obstetric outcomes during delivery hospitalizations among obese pregnant women in the United States. Sci Rep. 2022, 12, 6862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavazos-Rehg, P.; Krauss, M.; Spitznagel, E.; Bommarito, K.; Madden, T.; Olsen, M.; Subramaniam, H.; Peipert, J.; Bierut, L. Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Matern Child Health J. 2015, 19, 1202–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. NHS Long Term Workforce Plan, June 2023. Available online: NHS England » NHS Long Term Workforce Plan (Accessed on 1 October 2024) MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Department of Health. Children, young people and maternity services. Health Building Note 09-02: Maternity care facilities. Available online: HBN_09-02_Final.pdf (england.nhs.uk) (Accessed on 14 October 2024). MDPI: Please do not edit the url as it contains an embedded full url which is very long.

- Bailey, N. Queueing for medical care. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics). 1954, 3, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, A. Hospital and ward design with particular reference to obstetrical wards. South African Medical Journal. 1959, 33, 397–400. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, E.; Ayoub, B.; Miller, Y. A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of maternity models of care. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grøntved, S.; Kirkeby, M.; Johnsen, S.; Mainz, J.; Valentin, J.; Jensen, C. Towards reliable forecasting of healthcare capacity needs: A scoping review and evidence mapping. Int. J. Medical Informatics. 2024, 189, 105527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potančoková, M.; Marois, G. Projecting future births with fertility differentials reflecting women’s educational and migrant characteristics. Vienna Yearbook of Population Research. 2020, 18, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keilman, N. Uncertainty in population forecasts for the twenty-first century. Ann Rev Resource Econ. 2020, 12, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comolli, C.; Vignoli, D. Spreading Uncertainty, Shrinking Birth Rates: A Natural Experiment for Italy. Eur Sociol Rev. 2021, 37, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chao, F.; Gerland, P.; Cook, A.; Guilmoto, C.; Alkema, L. Projecting sex imbalances at birth at global, regional and national levels from 2021 to 2100: scenario-based Bayesian probabilistic projections of the sex ratio at birth and missing female births based on 3.26 billion birth records. BMJ Global Health. 2021, 6, e005516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Shang, H.; Raymer, J. Forecasting Australian fertility by age, region, and birthplace. International Journal of Forecasting. 2024, 40, 532–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, J.; Dodd, E.; Forster, J. Forecasting of cohort fertility under a hierarchical Bayesian approach. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society. 2020, 183, 829–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzitiridou-Chatzopoulou, M.; Zournatzidou, G.; Kourakos, M. Predicting Future Birth Rates with the Use of an Adaptive Machine Learning Algorithm: A Forecasting Experiment for Scotland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consterdine, E. The huge political cost of Blair’s decision to allow Eastern European migrants unfettered access to Britain. The Conversation, November 16, 2016. Available online: The huge political cost of Blair’s decision to allow Eastern European migrants unfettered access to Britain (theconversation.com) (Accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. National population projections, fertility assumptions: 2020-based interim. Available online: National population projections, fertility assumptions: 2020-based interim—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Office for National Statistics. National population projections, migration assumptions: 2020-based interim. Available online: National population projections, migration assumptions: 2020-based interim—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

- GovUK National pupil projections. July 2024. Available online: National pupil projections, Methodology—Explore education statistics—GOV.UK (explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk) (Accessed on 14 October 2024).

- Jones, R. Trends in Births and Implications to Maternity Capacity: A Report for Berkshire East PCT. September 2008. Available online: (PDF) Trends in Births and Implications to Maternity Capacity: A Report for Berkshire East PCT (researchgate.net) (Accessed on 23 September 2024).

- Office for National Statistics House building data, U.K. Available online: House building data, UK—Office for National Statistics (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

- Chodick, G.; Flash, S.; Deoitch, Y.; Shalev, V. Seasonality in birth weight: review of global patterns and potential causes. Human biology. 2009, 81, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, S.; Sone, T.; Doi, T.; Kahyo, H. Seasonality of Mean Birth Weight and Mean Gestational Period in Japan. Human Biology. 1993, 65, 481–501. [Google Scholar]

- Bobak, M.; Gjonca, A. The seasonality of live birth is strongly influenced by socio-demographic factors. Human Reproduction. 2001, 16, 1512–1517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, P.; McDonald, B. Seasonal variation of nutrient intake in pregnancy: effects on infant measures and possible influence on diseases related to season of birth. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2007, 61(11), 1271–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riala, K.; Hakko, H.; Taanila, A.; Räsänen, P. Season of birth and smoking: findings from the Northern Finland 1966 Birth Cohort. Chronobiology International. 2009, 26, 1660–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Boland, M.; Miotto, R.; Tatonetti, N.; Dudley, J. Replicating Cardiovascular Condition-Birth Month Associations. Scientific Reports. 2016, 6, 33166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boland, M.; Parhi, P.; Li, L.; Miotto, R.; Carroll, R.; Iqbal, U.; Nguyen, P.; Schuemie, M.; You, S.; et al. Uncovering exposures responsible for birth season—disease effects: a global study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2018, 25, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doyle, M.-A. Seasonal patterns in newborns’ health: Quantifying the roles of climate, communicable disease, economic and social factors. Economics & Human Biology. 2023, 51, 101287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Teoh, A.N.; Shukri, N.; Shafie, S.; Bustami, N.; Takahashi, M.; Lim, P.; Shibata, S. Circadian rhythm and its association with birth and infant outcomes: research protocol of a prospective cohort study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020, 20, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heres, M.; Pel, M.; Borkent-Polet, M.; Treffers, P.; Mirmiran, M. The hour of birth: comparisons of circadian pattern between women cared for by midwives and obstetricians. Midwifery. 2000, 16, 173–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykov, D.; Skeldon, A.; Whyte, M. Analysis of bed occupancy data on the acute medical unit. Future Health Journal 2020, 7, s84–s85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, V.; Boyle, J.; Hassanzadeh, H.; Yoon, J.; Diouf, I.; Khanna, S.; Samadbeik, M.; Sullivan, C.; Bosley, E.; Staib, A.; Lind, J. Do Midnight Censuses Accurately Portray Hospital Bed Occupancy? Health. Innovation. Community: It Starts With Us J. [CrossRef]

- Morton-Pradhan, S.; Bay, R.; Coonrod, D. Birth rate and its correlation with the lunar cycle and specific atmospheric conditions. Amer J Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005, 192, 1970–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arliss, J.; Kaplan, E.; Galvin, S. The effect of the lunar cycle on frequency of births and birth complications. Amer J of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2005, 192, 1462–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, K.; Bender, S.; Heining, J.; Schmidt, C. The lunar cycle, sunspots and the frequency of births in Germany, 1920–1989. Economics & Human Biology. 2013, 11, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, S.-i.; Shirahashi, K. Novel perspectives on the influence of the lunar cycle on the timing of full-term human births. Chronobiology International. 2020, 37, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemeth, K. , Bayraktar, R., Ferracin, M.; Calin, G. Non-coding RNAs in disease: from mechanisms to therapeutics. Nat Rev Genet 2024, 25, 211–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, K.; Gupta, A.; Rawat, V.; Sharma, V.; Shakya, S. Chapter 11—Role of noncoding RNAs in host-pathogen interactions: a systems biology approach, Editor(s): Mohd. Tashfeen Ashraf, Abdul Arif Khan, Fahad, M. Aldakheel, In Developments in Microbiology, Systems Biology Approaches for Host-Pathogen Interaction Analysis, Academic Press, 2024, pp 213-249. [CrossRef]

- Eichner, H.; Karlsson, J.; Loh, E. The emerging role of bacterial regulatory RNAs in disease. Trends Microbiol. 2022, 30, 959–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzur, Y. lncRNAs in fertility: redefining the gene expression paradigm? Trends Genet. 2022, 38, 1170–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, J.; Jin, H.; Zhu, Y. The Role of Placental Non-Coding RNAs in Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khambata, K.; Modi, D.; Gupta, S. Immunoregulation in the testis and its implication in fertility and infections. Explor Immunol. 2021, 1, 309–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, M.; Venkatesh, S.; Gupta, P. The role of infections in infertility: A review. International Journal of Academic Medicine 2020, 6, 189–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giakoumelou, S.; Wheelhouse, N.; Cuschieri, K.; Entrican, G.; Howie, S.E.; Horne, A.W. The role of infection in miscarriage. Hum Reprod Update. 2016, 22, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megli, C.J.; Coyne, C.B. Infections at the maternal–fetal interface: an overview of pathogenesis and defence. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022, 20, 67–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racicot, K.; Kwon, J.; Aldo, P.; Silasi, M.; Mor, G. Understanding the complexity of the immune system during pregnancy. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014, 72, 107–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu-Raya, B.; Michalski, C.; Sadarangani, M.; Lavoie, P.M. Maternal Immunological Adaptation During Normal Pregnancy. Front Immunol. 2020, 11, 575197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lain, K.; Catalano, P. Metabolic changes in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2007 50, 938–48. [CrossRef]

- Légaré, C.; Clément, AA.; Desgagné, V.; et al. Human plasma pregnancy-associated miRNAs and their temporal variation within the first trimester of pregnancy. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2022, 20, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arya, S.; Mulla, Z.; Plavsic, S. Outcomes of Women Delivering at Very Advanced Maternal Age. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2018, 27, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delpisheh, A.; Brabin, L.; Brabin, B. Pregnancy, smoking and birth outcomes. Women’s Health. 2006, 2, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDonald, S.; Han, Z.; Mulla, S.; Beyene, J. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: systematic review and meta-analyses. Bmj. 2010, 20, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, C.; Nassar, N.; Kurinczuk, J.; Bower, C. The effect of maternal alcohol consumption on fetal growth and preterm birth. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2009, 116, 390–400. [Google Scholar]

- Pinto, S.; Dodd, S.; Walkinshaw, S.; Siney, C.; Kakkar, P.; Mousa, H. Substance abuse during pregnancy: effect on pregnancy outcomes. Eur J Obs Gyne Reprod Biol. 2010, 150, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Health Security Agency.UK maps of radon. Available online: UKradon—UK maps of radon (Accessed on 17 October 2024).

- World Health Organization. Radon. Available online: Radon (who.int) (Accessed on 17 October 2024).

- Papatheodorou, S.; Yao, W.; Vieira, C.; Li, L.; Wylie, B.; Schwartz, J.; Koutrakis, P. Residential radon exposure and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Massachusetts, USA: A cohort study. Environ Int. 2021, 146, 106285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.; Li, L.; Son, J.; Koutrakis, P.; Bell, M. Associations between gestational residential radon exposure and term low birthweight in Connecticut, USA. Epidemiology. 2024. [CrossRef]

- NHS England (National Maternity Review). Better Births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England—A Five Year Forward View for maternity care. 22 February 2016. Available online: NHS England » Better Births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England—A Five Year Forward View for maternity care.

- NHS England. Maternity Transformation Programme. Available online: NHS England » Maternity Transformation Programme (Accessed on 14 October 2024).

- NHS England. Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services. Available online: NHS England » Three year delivery plan for maternity and neonatal services (Accessed on 23 October 2024).

- GOVUK Independent investigation of the National Health Service in England. Available online: Independent Investigation of the National Health Service in England (publishing.service.gov.uk) (Accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Homer, C.; Biggs, J.; Vaughan, G.; Sullivan, E. Mapping maternity services in Australia: location, classification and services. Australian Health Review 2011, 35, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilkington, H.; Blondel, B.; Drewniak, N.; et al. Choice in maternity care: associations with unit supply, geographic accessibility and user characteristics. Int J Health Geogr. 2012, 11, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redshaw, M.; Rowe, R.; Schroeder, L.; Puddicombe, D.; MacFarlane, A.; Newburn, M.; McCourt, C.; Sandall, J.; Silverton, L.; Marlow, N. Mapping maternity care: the configuration of maternity care in England. Birthplace in England research programme (Final report part 3 08/1604/140). Southampton, UK: HMSO.2011. Available online: Mapping maternity care: the configuration of maternity care in England (city.ac.uk) (Accessed on 17 September 2024).

- Pilkington, H.; Blondel, B.; Papiernik, E.; Cuttini, M.; Charreire, H.; Maier, R.; Petrou, S.; Combier, E.; Künzel, W.; Bréart, G.; Zeitlin, J. Distribution of maternity units and spatial access to specialised care for women delivering before 32 weeks of gestation in Europe. Health & Place. 2010, 16, 531–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. Why are we trying to reduce length of stay? Evaluation of the costs and benefits of reducing time in hospital must start from the objectives that govern change. Qual Health Care. 1996, 5, 172–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taheri, P.; Butz, D.; Greenfield, L. Length of stay has minimal impact on the cost of hospital admission. J Amer Coll Surgeons 2000, 191, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, G.; Board, N.; Paten, A.; Tazelaar-Molinia, J.; Crowe, P.; Yap, S.-Y.; Brown, A. Decreasing length of stay: The cost to the community. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery. 1999, 69, 433–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauh, S.; Wadsworth, E.; Weeks, W. The fixed-cost dilemma: what counts when counting cost-reduction efforts? Healthc Financ Manage. 2010, 64, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, O.; Cegolon, L.; Macleod, D.; Benova, L. Length of Stay After Childbirth in 92 Countries and Associated Factors in 30 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Compilation of Reported Data and a Cross-sectional Analysis from Nationally Representative Surveys. PLOS Medicine. 2016, 13, e1001972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grašič, K.; Mason, A.; Street, A. Paying for the quantity and quality of hospital care: the foundations and evolution of payment policy in England. Health Econ Rev 2015, 5, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sacchetti, A.; Gerardi, M.; Sawchuk, P.; Bihl, I. Boomerang babies: emergency department utilization by early discharge neonates. Pediatric Emerg Care, 1997, 13, 365–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, C.; Stewart, M. Factors associated with early neonatal attendance to a paediatric emergency department. Arch Disease Childhood 2014, 99, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J.; Cheyne, H. Reducing the length of postnatal hospital stay: implications for cost and quality of care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benitz, W.; Committee on fetus and newborn, Watterberg, K. ; Aucott, S.; Benitz, W.; Cummings, J.; Eichenwald, E.; Goldsmith, J.; Poindexter, B.; Puopolo, K.; Stewart, D.; Wang, K. Hospital Stay for Healthy Term Newborn Infants. Pediatrics, 2015, 135, 948–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datar, A.; Sood, N. Impact of postpartum hospital-stay legislation on newborn length of stay, readmission, and mortality in California. Pediatrics. 2006, 118, 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Safe midwifery staffing for maternity settings. Available online: Overview | Safe midwifery staffing for maternity settings | Guidance | NICE (Accessed on 16 October 2024).

- NHS Improvement. Standards and structures that underpin safer, more personalised, and more equitable care. Available online: Developing-workforce-safeguards.pdf (Accessed on 23 October 2024).

- Carey, K.; Burgess, J.; Young, G. Economies of scale and scope: The case of specialty hospitals. Contemp Econ Policy. 2015, 33, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaynor, M.; Kleiner, S.; Vogt, W. Analysis of hospital production: An output index approach. J. Appl. Econometrics. 2015, 30, 398–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, M.; Savva, N.; Scholtes, S. Economies of Scale and Scope in Hospitals: An Empirical Study of Volume Spillovers. Management Science. 2021, 67, 673–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NHS England. Maternity payment pathway system. Available online: maternity_payment_pathway_system_supplementary_guidance.pdf (Accessed on 29 October 2024).

- NHS England. A guide to the market forces factor. Available online: 23-25NHSPS Guide to the market forces factor (Accessed on 30 October 2024).

- NHS England. Approved costing guidance. Available online: NHS England » Approved Costing Guidance 2024—Introduction (Accessed on 1 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).