Submitted:

06 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Particle Size Distribution (PSD)

2.2.2. Density of Chocolate Samples

2.2.3. Melting Properties of Chocolates

2.2.4. Chocolate Hardness

2.2.5. Rheological Properties of Chocolate Mass

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

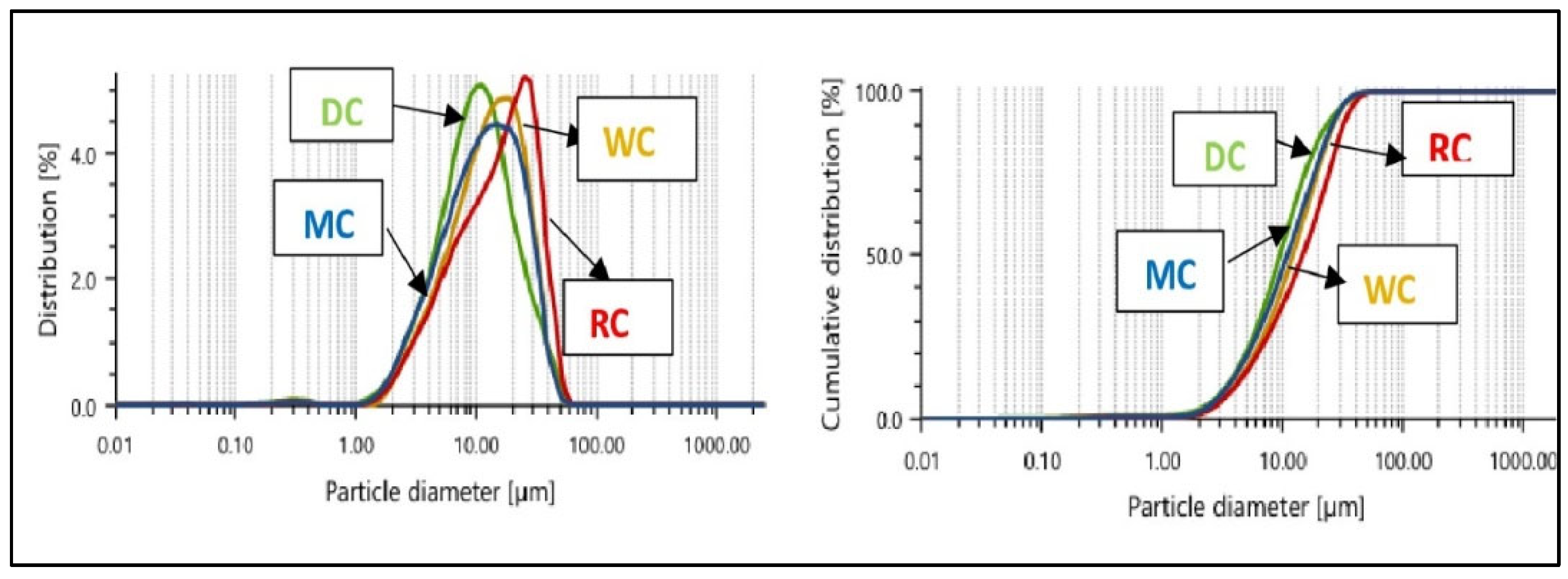

3.1. Comparative Overview of Particle Size Distribution in Tested Chocolate Samples

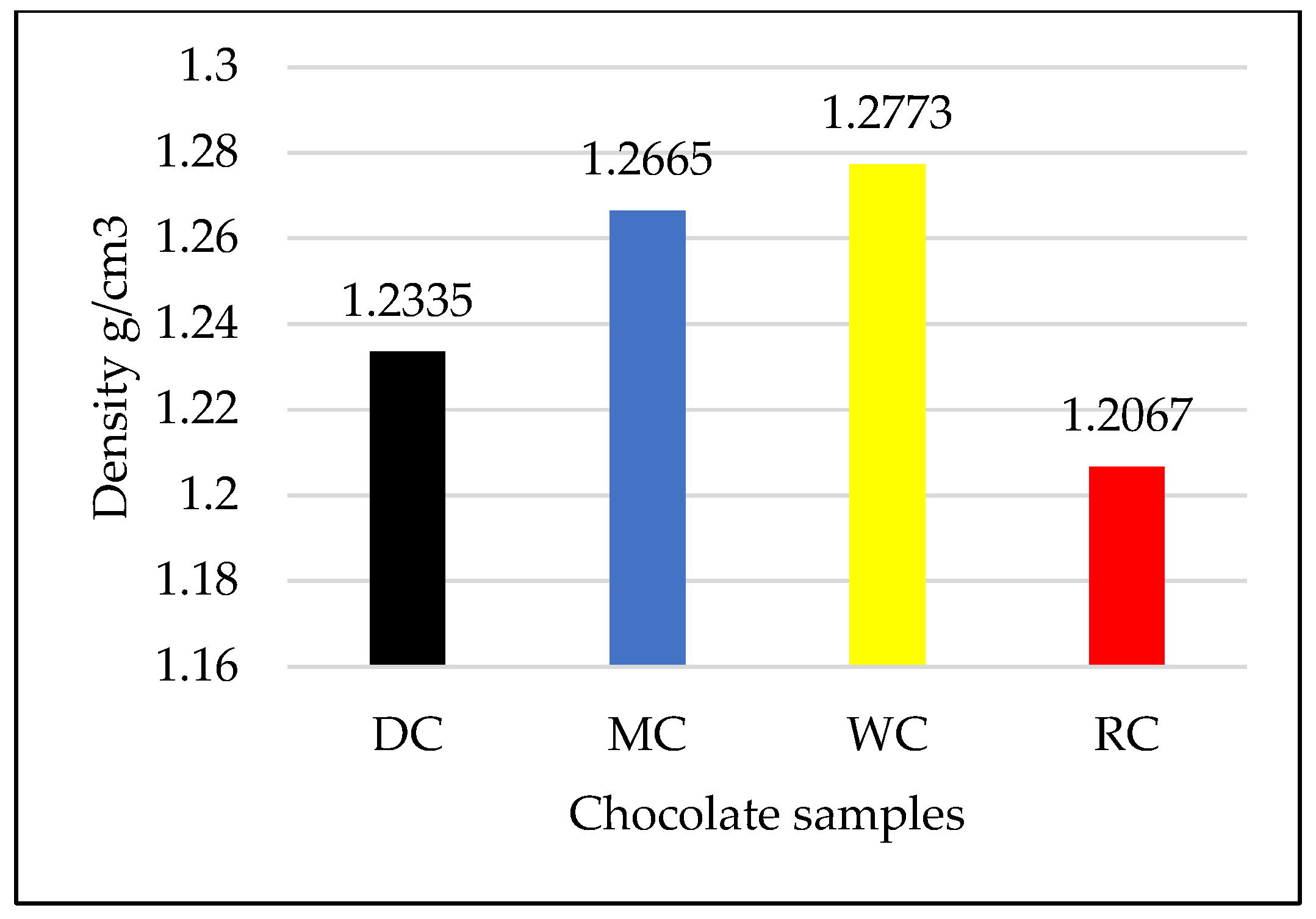

3.2. Comparative Overview of Density in Tested Chocolate Samples

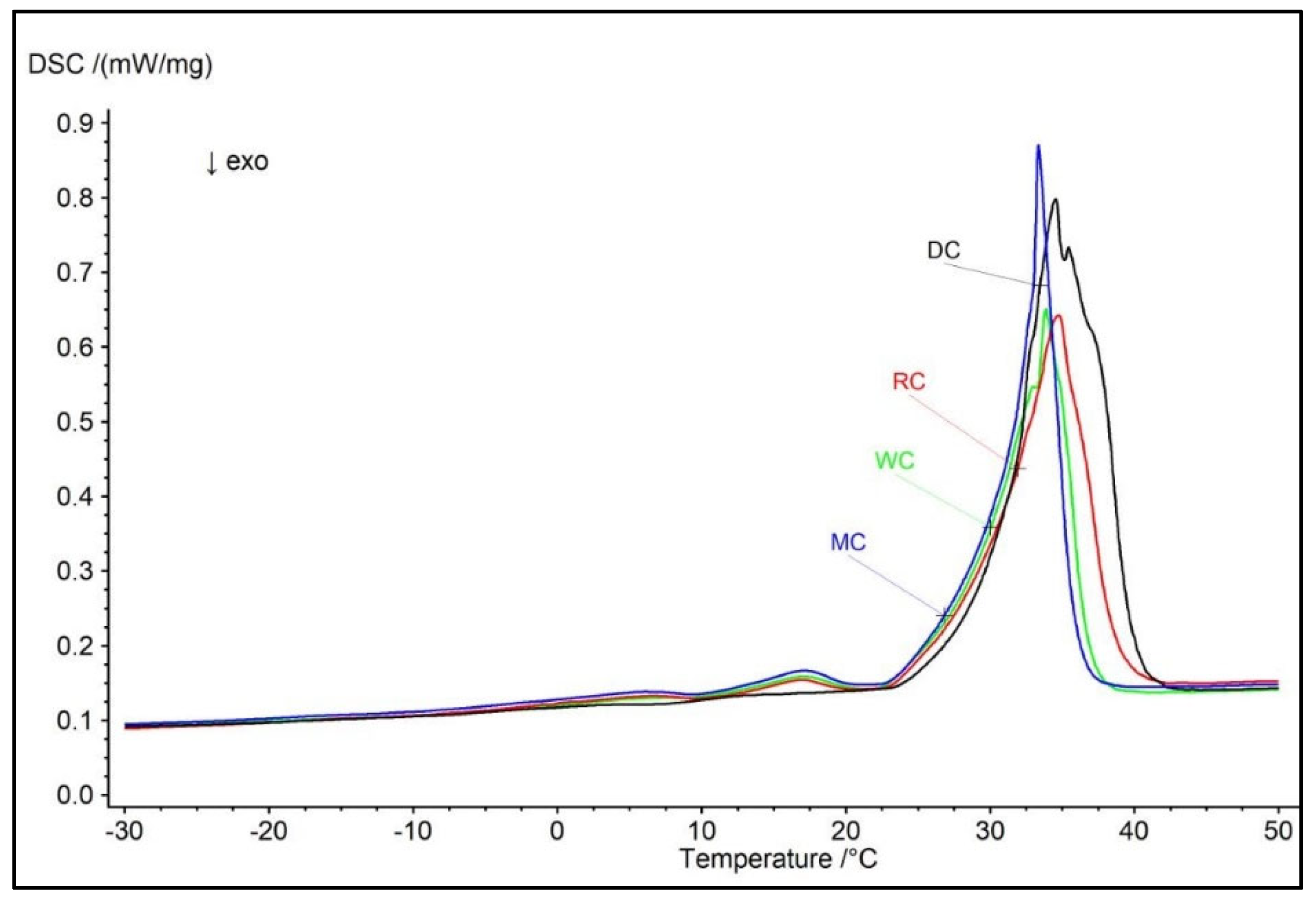

3.3. Comparative Overview of Melting Properties and Hardness in Tested Chocolate Samples

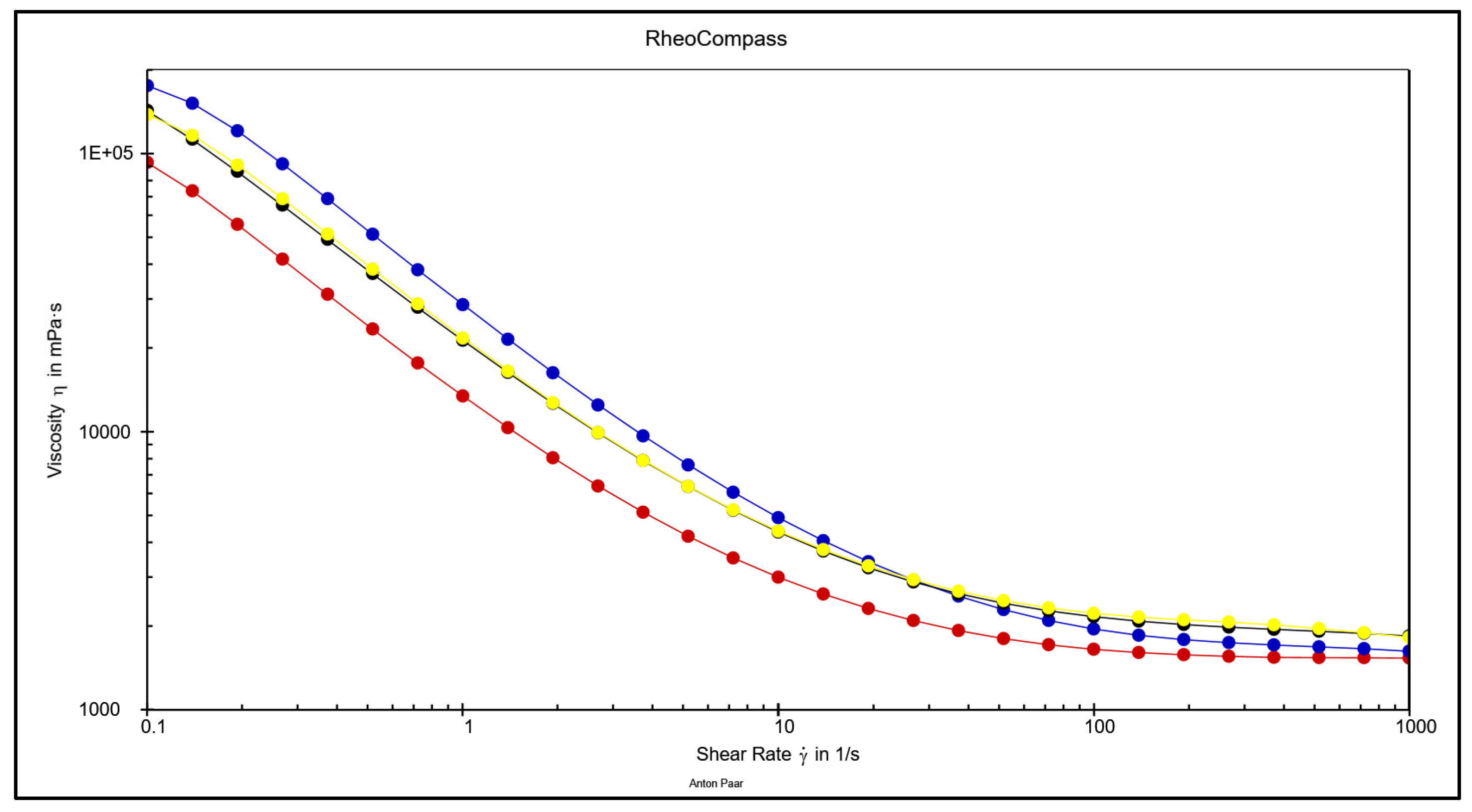

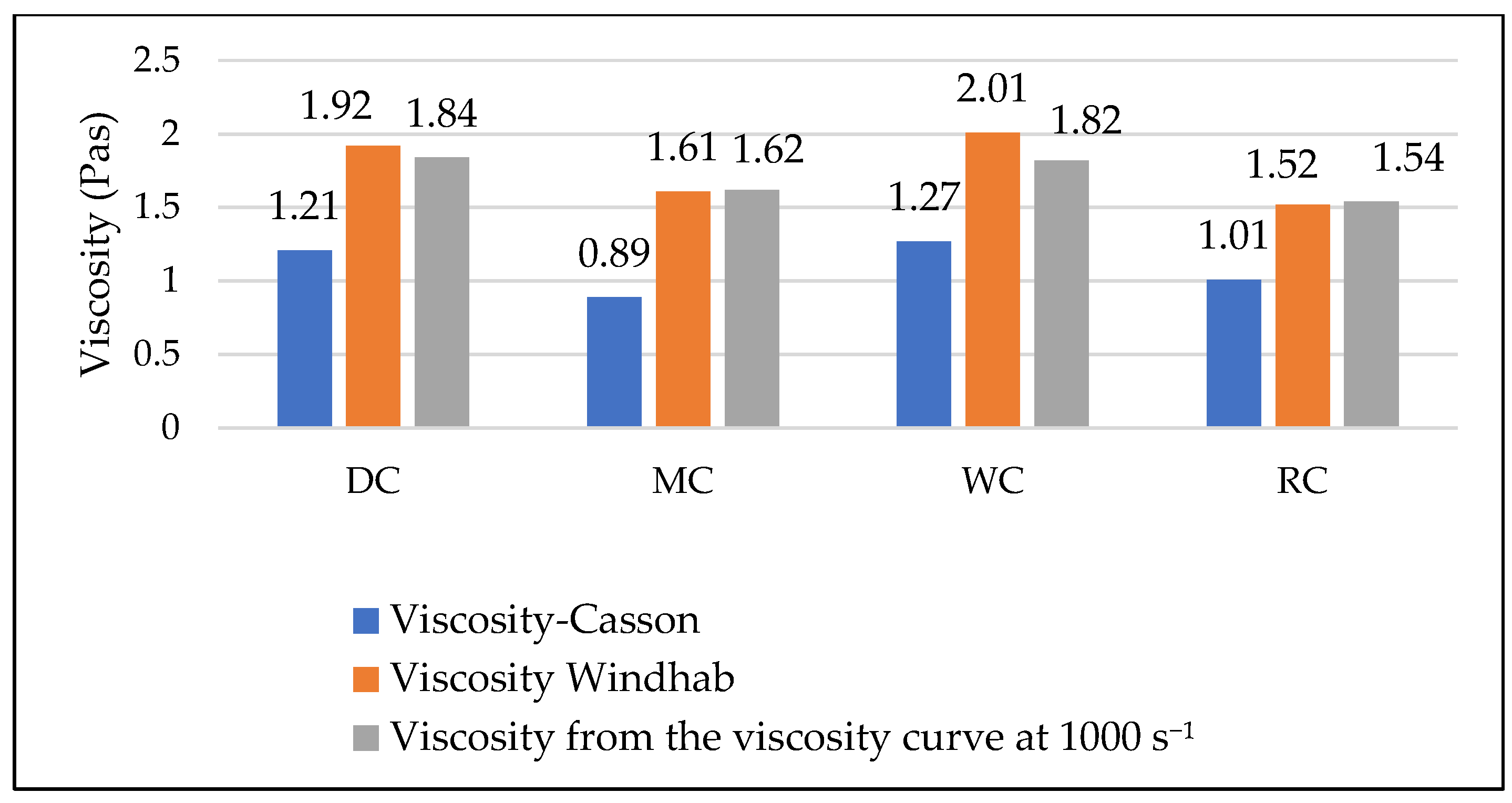

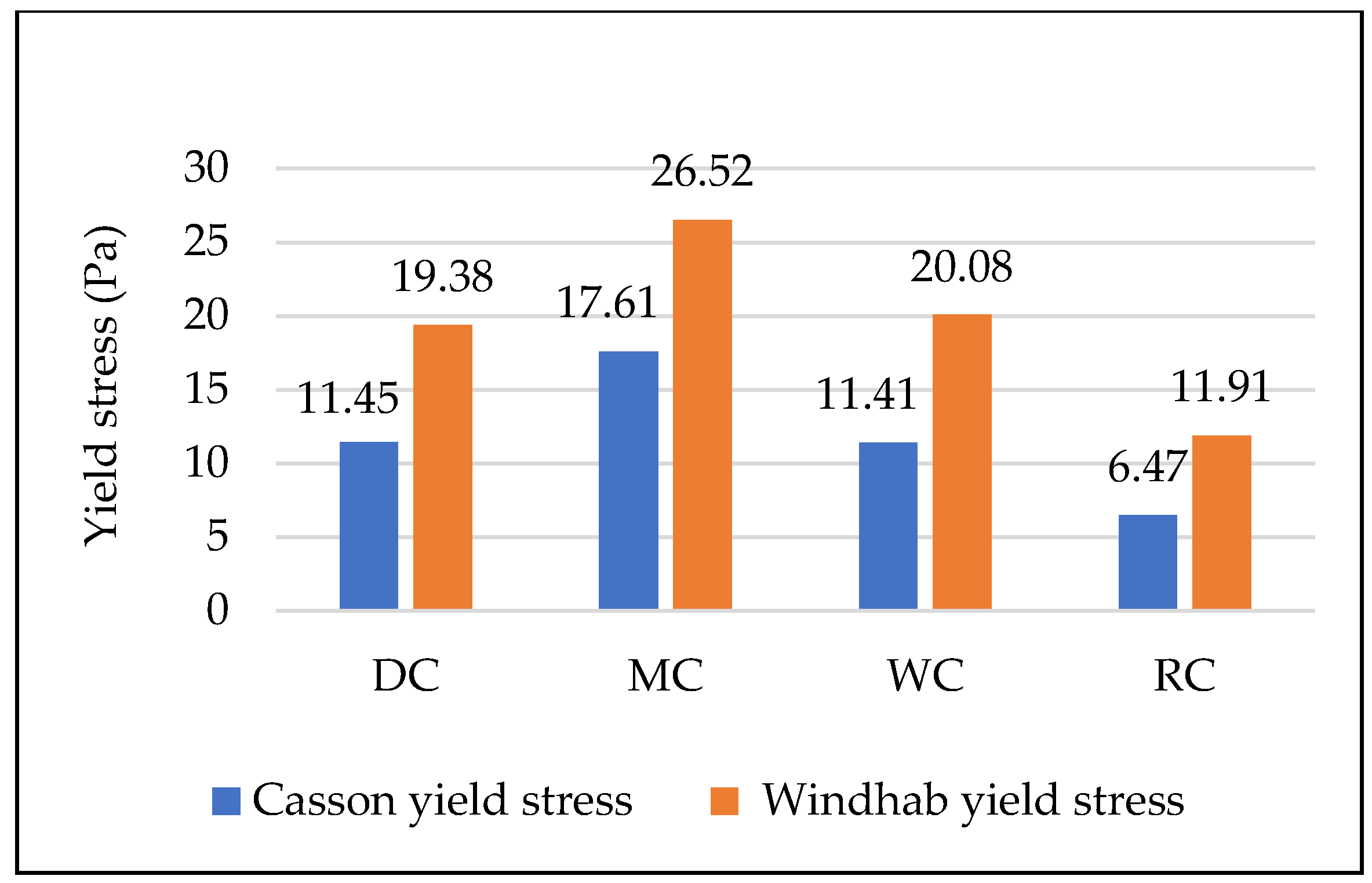

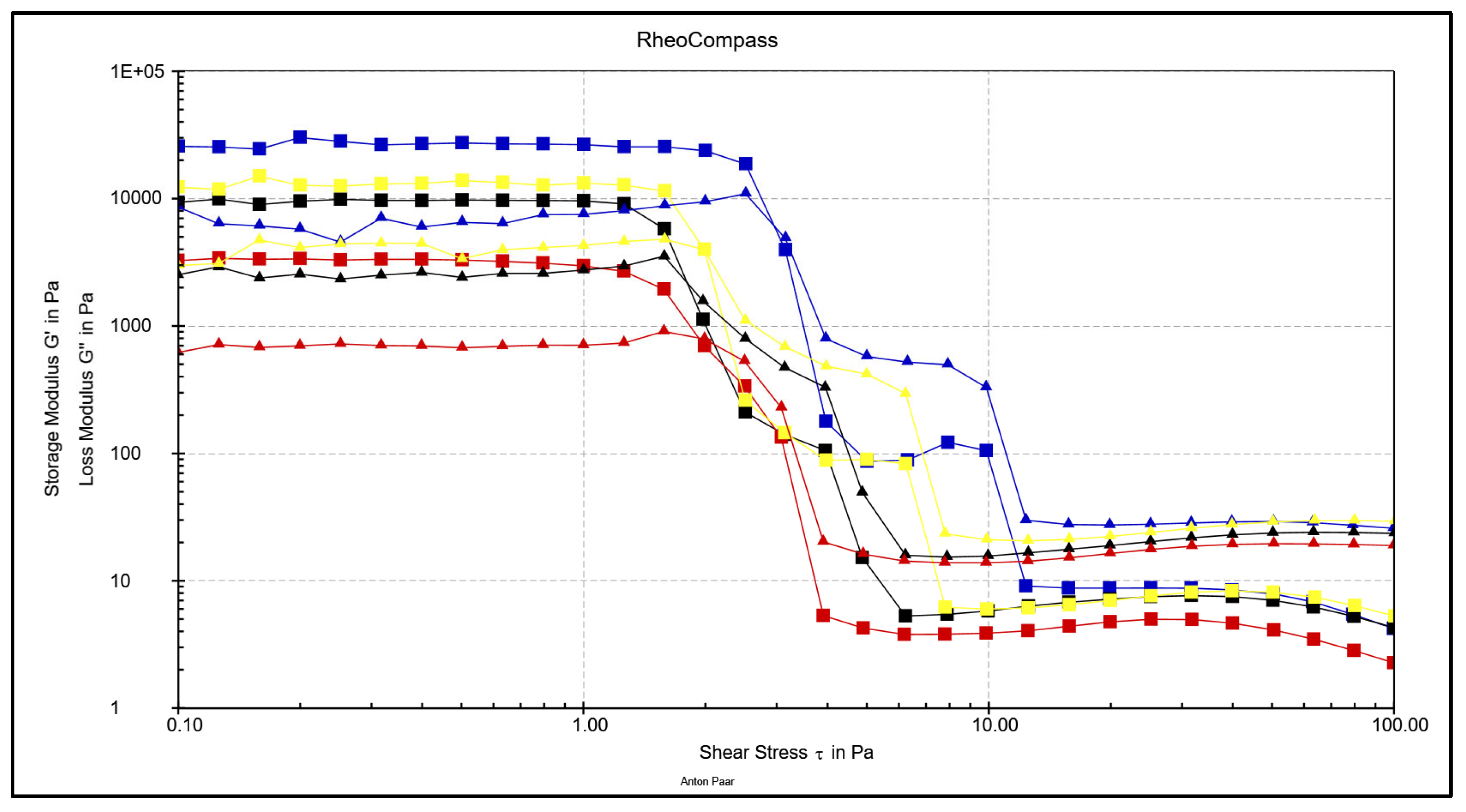

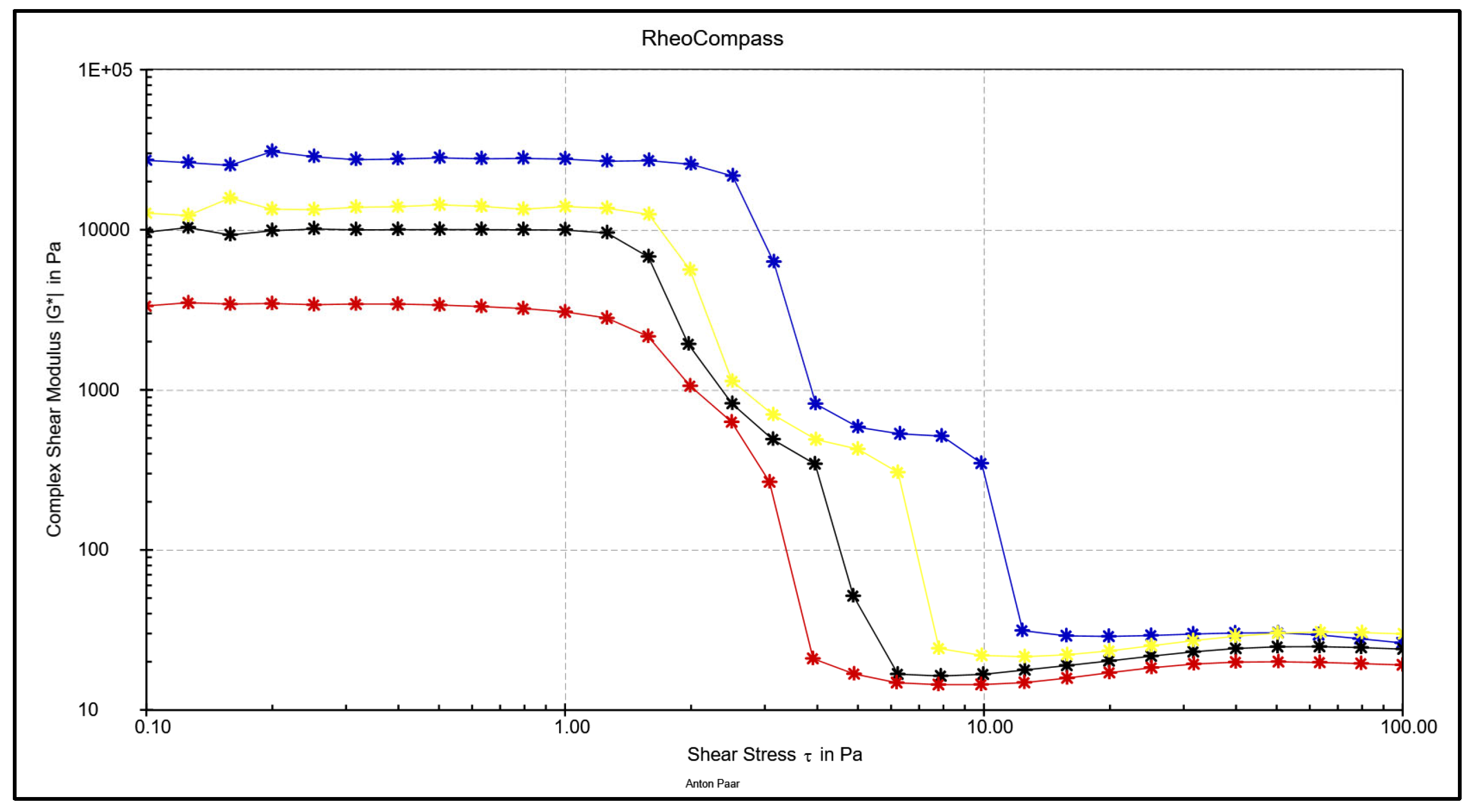

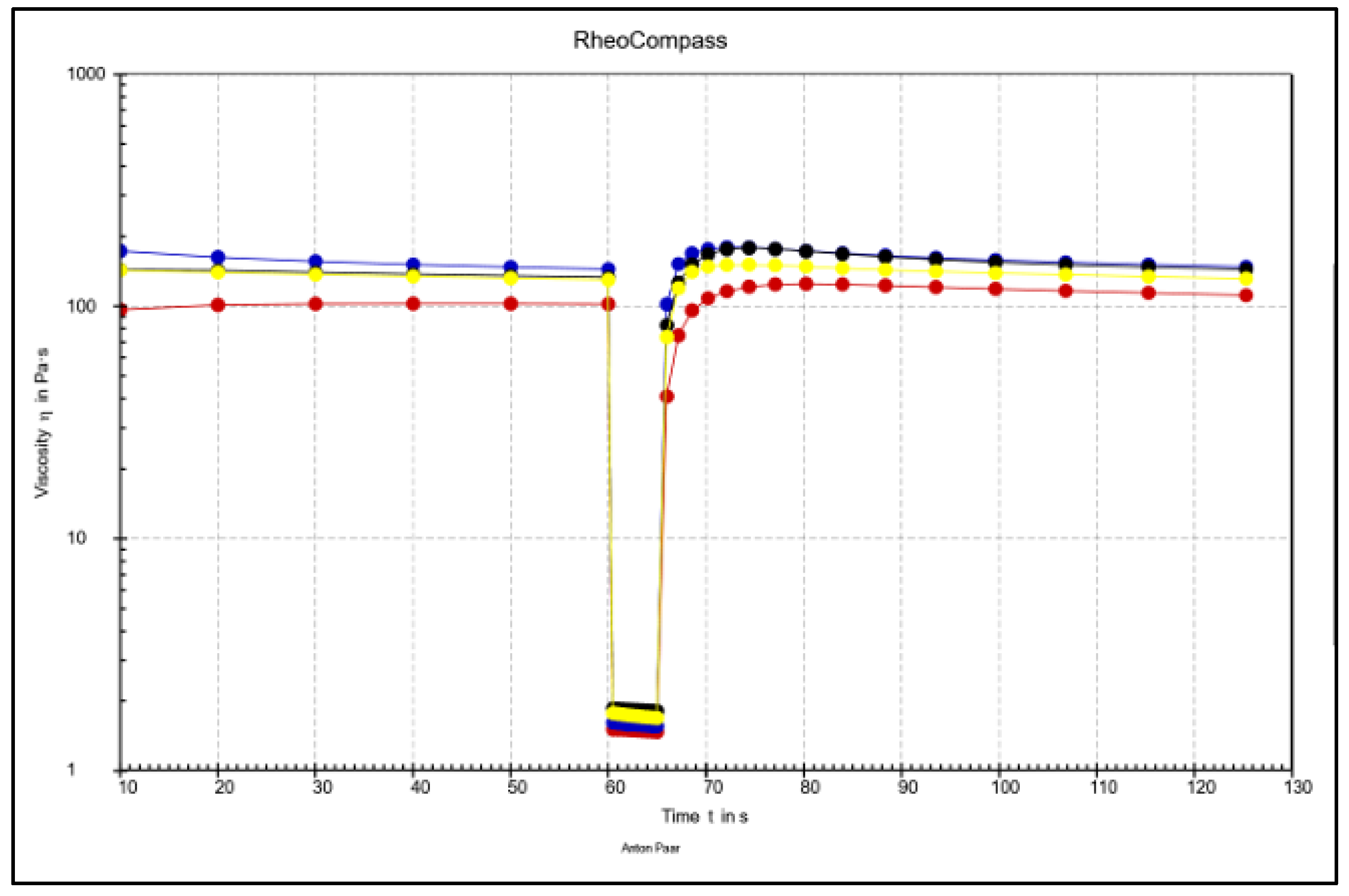

3.4. Comparative Overview of Rheology Properties in Tested Chocolate Samples

4. Conclusions

- Density increases in the order RC - DC - MC - WC and depends on the cocoa content and fat quantity.

- The hardness of the chocolates decreases in the following order: DC - MC - RC - WC (inversely proportional to particle size and the amount of milk fat).

- Melting enthalpy in the chocolates increases with the rise in cocoa content.

- In classical rheological measurements (viscosity and yield stress), the greatest influence comes from particle size (larger particles result in lower viscosity and yield stress) and the quantity and type of fat (higher fat content reduces both viscosity and yield stress, but has a much greater effect on viscosity).

- According to oscillatory rheological measurements, all chocolates exhibit greater elastic response compared to viscous one until the point of structural disruption (G' > G'').

- The LVE (Linear Viscoelastic) range decreases in the order MC - WC - DC – RC indicating that the strongest network of forces is built in MC and weakest in RC

- Based on oscillatory rheological measurements, the complex modulus (G*), or the rigidity of the system, decreases in the chocolates in the order MC - WC - DC - RC.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fernandes, V.A.; Müller, A.J.; Sandoval, A.J. Thermal, structural and rheological characteristics of dark chocolate with different compositions. J Food Eng. 2013, 116, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2000/36/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council; Official Journal of the European Communities, 23 June 2000.

- Regulation on Cocoa and Chocolate Products Intended for Human Consumption, Official Gazette Serbia 24/2019 and 18/2024.

- Dumarche, A.; Troplin, P.; Bernaert, H.; Lechevalier, P.; Beerens, H.; Landuyt, A. Process for Producing Cocoa-Derived Material. European Patent EP2237677B1, 13 June 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Tuenter, E.; Sakavitsi, M.E.; Rivera-Mondragon, A.; Hermans, N.; Foubert, K.; Halabalaki, M.; Pieters, L. Ruby chocolate: A study of its phytochemical composition and quantitative comparison with dark, milk and white chocolate. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šeremet, D.; Mandura, A.; Vojvodić Cebin, A.; Oskomić, M.; Champion, E.; Martinić, A.; Komes, D. Ruby chocolate—Bioactive potential and sensory quality characteristics compared with dark, milk and white chocolate. Food Health Dis. 2019, 8, 89–96, https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:209754360. [Google Scholar]

- Kumbár, V.; Kouřilová, V.; Dufková, R.; Votava, J.; Hřivna, L. Rheological and Pipe Flow Properties of Chocolate Masses at Different Temperatures. Foods 2021, 10, 2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Dolatowska-Żebrowska, K.; Brzezińska, R.; Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Bryś, J.; Piasecka, I.; Górska, A. Characterization of Thermal Properties of Ruby Chocolate Using DSC, PDSC and TGA Methods. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Marzec, A.; Górska, A.; Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Bryś, J.; Rejch, A.; Czarkowska, K. A Comparative Study of Thermal and Textural Properties of Milk, White, and Dark Chocolates. Thermochim. Acta, 2019, 671, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolatowska-Żebrowska, K.; Ostrowska-Ligęza, E.; Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Brys, J. Characterization of thermal properties of goat milk fat and goat milk chocolate by using DSC, PDSC and TGA methods. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2019, 138, 2769–2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, D.; Sonwai, S. Influence of the Dispersed Particulate in Chocolate on Cocoa Butter Microstructure and Fat Crystal Growth during Storage. Food Biophysics. 2008, 3, 273–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M. Effects of particle size distribution and composition on rheological properties of dark chocolate. Eur Food Res Technol. 2008, 226, 1259–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckett, S. T. ; The Science of Chocolate. 2rd ed.; The Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2008; 104-110.

- Bolenz, S.; Holm, M.; Langkrär, C. Improving particle size distribution and flow properties of milk chocolate produced by ball mill and blending. Eur Food Res Technol. 2014, 238, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J. E.; VanDamme, I.; Johns, M. L.; Routh, A. F.; Wilson, D. I. Shear rheology of molten crumb chocolate. Journal of Food Science, 2009, 74, E55–E61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Graef, V.; Depypere, F.; <monospace> </monospace>Minnaert, M.; Dewettinck, K. Chocolate Yield Stress as Measured by Oscillatory Rheology. Food Res In., 2011, 44, 2660–2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naining, W. , & Hongjian, Z. A study of the accuracy of optical fraunhofer diffraction size analyzer. Part. Sci and Techn 1986, 4, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOCCC. Viscosity of Cocoa and Chocolate Products. Anal. Method 2000, 46, 1–7.

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M.; Vieira, J. Particle size distribution and compositional effects on textural properties and appearance of dark chocolates. J. Food Eng. 2008, 87, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziegler, G.R.; Mongia, G.; Hollender, R. Role of particle size distribution of suspended solids in defining the sensory properties of milk chocolate. Int. J. Food Prop. 2001, 4, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolenz, S. and Manske, A. Impact of Fat Content during Grinding on Particle Size Distribution and Flow Properties of Milk Chocolate. Eur. Food Research Technol. 2013, 236, 863–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glicerina, V.; Balestra, F.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Romani, S. Rheological, textural and calorimetric modifications of dark chocolate during process. J Food Eng. 2013, 119, 173–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bettersize Instruments Ltd. 2024. The Role of True Density Analysis in Chocolate Manufacturing Quality. AZoM, (accessed 17 October 2024). https://www.azom.com/article.aspx?ArticleID=23293.

- Zaric, D.; Rakin, M.; Bulatovic, M; Krunić T. ; Lončarević I.; Pajin B.; Blaževska Z. Influence of added extracts of herbs (Salvia lavandulifolia, Salvia officinalis) and fruits (Malpighia glabra) on rheological, textural, and functional (AChE-inhibitory and antioxidant activity) characteristics of dark chocolate. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2022, 18, 772–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lončarević, I.; Pajin, B.; Fišteš, A.; Tumbas Šaponjac, V.; Petrović, J.; Jovanović, P.; Vulić, J.; Zarić, D. Enrichment of white chocolate with blackberry juice encapsulate: Impact on physical properties, sensory characteristics and polyphenol content. LWT, 2018, 92, 458–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazani, S.M.; Marangoni, A.G. ; Molecular origins of polymorphism in cocoa butter. Food Sci Technol 2021, 12, 567–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merken, G.; Vaeck, S. Étude du polymorphisme du beurre de cacao par calorimetrie DSC, Lebensm. Wiss. Technol. 1980, 13, 314–317. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.; Liu, Y.; Jin, Q.; Meng, Z.; Wang, X. Characterization of cocoa butter substitutes, milk fat and cocoa butter mixtures, Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, D.R.A.; Saputro, A.D.; Rottiers, H.; Van de Walle, D.; Dewettinck, K. Physicochemical Properties and Antioxidant Activities of Chocolates Enriched with Engineered Cinnamon Nanoparticles. Eur. Food Res. Technol, 2018, 244, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, N.; Özhan, B.; Artık, N.; Dalabasmaz, S.; Poyrazoglu, E.S. Rheological and physical properties of inulin-containing milk chocolate prepared at different process conditions. CYTA J. Food. 2013, 12, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtinger, A.; Scholten, E.; Sala, G. Effect of particle size distribution on rheological properties of chocolate. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 9547–9559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afoakwa, E.O.; Paterson, A.; Fowler, M.; Vieira, J. Microstruc-ture and mechanical properties related to particle size distribu-tion and composition in dark chocolate. Int J Food Sci Technol, 2009, 44, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajin, B. ; Tehnologija čokolade i kakao proizvoda, 1rd ed.; Tehnološki fakultet Novi Sad, Serbia, 2014, 100-105.

- Do, T.-A.L.; Hargreaves, J. M.; Wolf, B.; Mitchell, J. R. Impact of particle Size Distribution on Rheological and Textural Properties of Chocolate Models with Reduced Fat Content. J Food Sci, 2007,72, 541-552. [CrossRef]

- Walls,H. J.; Caines,S.B.; Sanchez, A.M.; Khan,S.A. Yield stress and wall slip phenomena in colloidal silica gels. J. Rheol, 2003, 47, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Guo, T.; Han, F.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z. ; Rheological and Sensory Properties of Four Kinds of Dark Chocolates, AJAC, 2015, 6, 1010–1018. [CrossRef]

- Marina, D. Kalić, Physico-chemical and rheological characterization of fish oil microcapsules incorporated in a chocolate matrix, PhD Thesis, University of Novi Sad, Faculty of Medicine, Hajduk Veljkova 3, Novi Sad, Republic of Serbia, 30. 05. 2019.

| RC | DC | MC | WC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Value (kJ) | 2340 | 2255 | 2357 | 2379 |

| Fats (g) | 36 | 39 | 36 | 36 |

| of which saturated fatty acids | 21 | 23 | 22 | 21.6 |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 50 | 31 | 51.9 | 55.5 |

| Of which sugars | 49 | 26 | 50 | 55 |

| Proteins (g) | 9.3 | 8.5 | 7 | 6 |

| Salt (g) | 0.27 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Ingredients | sugar, cocoa butter, skimmed milk powder, whole milk powder, cocoa mass, emulsifier soy lecithin, citric acid, natural vanilla flavor. | cocoa mass, sugar, cocoa powder with reduced cocoa butter content, emulsifier soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavor. | sugar, cocoa butter, whole milk powder, cocoa mass, emulsifier soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavor. | sugar, cocoa butter, whole milk powder, emulsifier soy lecithin, natural vanilla flavor. |

| Cocoa parts: min. (%) | 47 | 70 | 33 | 28 |

| Parameters | Sample of Chocolate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DC | RC | MC | WC | |

| d(0.1) µm | 3.392 ± 0.039a | 4.078 ± 0.018b | 3.525 ± 0.052c | 3.917 ± 0.046d |

| d(0.5) µm | 9.441 ± 0.034a | 14.569 ± 0.133b | 10.790 ± 0.062c | 11.831 ± 0.225d |

| d(0.9) µm | 23.487 ± 0.112a | 31.965 ± 0.211b | 25.181 ± 0.375c | 25.575 ± 0.505c |

| D[4.3] µm | 12.301 ± 0.036a | 17.427 ± 0.118b | 13.445 ± 0.144c | 14.155 ± 0.259d |

| SPAN | 2.128 ± 0.020a | 1.914 ± 0.011b | 2.007 ± 0.260ab | 1.831 ± 0.018c |

| Chocolate | Melting Parameters | Textural Properties | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tons (°C) | Tend (°C) | Tpeak (°C) | ΔH (J/g) | Hardness (g) | |

| DC | 24.4 ± 0.08a | 40.2 ± 0.16a | 34.5± 0.21a | 55.04 ± 0.54a | 4994.0 ± 28.50a |

| MC | 24.3 ± 0.14a | 35.9 ± 0.19b | 33.3± 0.15ab | 36.76 ± 0.32b | 4782.0 ± 26.70b |

| RC | 19.9 ± 0.11b | 38.9 ± 0.12c | 34.7± 0.17ac | 39.91 ± 0.34c | 4648.0 ± 38.20c |

| WC | 23.6 ± 0.09c | 36.8 ± 0.13b | 33.9± 0.20acd | 35.30 ± 0.30b | 4082.0 ± 44.30d |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).