1. Introduction

On 23

rd October 2014, the New York Times front page reported its finding “

What Drugmakers Did Not Tell Volunteers in Alzheimer’s Trials,” which disclosed serious concerns about the clinical trials conducted for Alzheimer’s drugs like Eisai's Leqembi (lecanemab-irmb) and Eli Lilly’s Kisunla (donanemab-azbt )[

1]. It describes how drug companies failed to disclose critical genetic test results to participants, especially regarding the APOE4 gene variant, which increases the risk of brain injuries in patients receiving these drugs [

2]. By 2021, about 2,000 participants enrolled in the Leqembi trials, among them a high-risk subset predisposed to brain bleeding and swelling [

3].

Despite informing volunteers about potential genetic testing, companies withheld individual results, a decision now seen as a violation of informed consent principles by bioethicists. Two high-risk volunteers died, and over 100 experienced brain bleeding or swelling, some with severe consequences. Eisai's Leqembi received FDA approval in 2023 under an accelerated approval process despite its safety concerns, which should not have shown only a modest cognitive benefit [

4]. In 2024, the FDA had called a meeting to discuss whether it should receive traditional approval. Despite many serious concerns, including the author, the FDA granted traditional approval [

3]. However, regulatory agencies in the European Union [

5] and Australia [

6] rejected it due to its temporary and limited efficacy compared to its risks.

2. Testing Antibodies to Treat Neurological Disorders

The risks associated with amyloid-beta, tau protein, and alpha-synuclein-targeting drugs extend beyond immediate brain injuries, with studies suggesting a higher mortality rate among those treated with antibodies than untreated Alzheimer’s patients. There is also emerging evidence that these drugs may accelerate brain shrinkage, further compounding concerns about their long-term safety. Considering these findings, the clinical trials exemplify the ethical and medical complexities of advancing treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

The relationship between amyloid-beta, tau protein, and alpha-synuclein-targeting drugs and mortality rates among treated patients is an emerging area of research, particularly in neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease.

Many antibodies targeting amyloid-beta (e.g., aducanumab, lecanemab) have been investigated for their ability to clear amyloid plaques in Alzheimer's patients. Some studies have reported an increase in mortality or serious adverse events in patients treated with these antibodies compared to controls, particularly in those with more advanced disease or certain comorbidities [

7]. Similar observations were reported with treatments targeting tau protein [

8] and the alpha-synuclein-targeting antibodies (e.g., prasinezumab) [

9]. Many of the concerns about mortality have emerged from post-hoc analyses of clinical trial data, emphasizing the need for ongoing monitoring and long-term studies. This concern is now further highlighted in the recent NY Times investigation.

While companies continue to pursue the development of these drugs, scientists suggest a broader focus on alternative therapeutic avenues, such as reducing inflammation or enhancing blood flow, as the amyloid theory alone appears insufficient to address Alzheimer's multifaceted nature. The list failed antibodies include Aducanumab [

10], Bapineuzumab [

11], Bepranemab [

12], Cinpanemab [

13], Crenezumab [

14], Gantenerumab [

15], GSK933776 [

16], Ponezumab [

17], Prasinezumab [

13], Semorinemab [

18], Solanezumab [

19], Tilavonemab [

12]

3. Future

While the flaws in clinical trials of neurological disorder treatments with antibodies have begun to rise, a more significant issue, whether these drugs even qualify to be tested in the first place based on their lack of bioavailability in the brain, has been widely ignored [

20]. The known bioavailability of these antibodies is 0.01-0.1% [

21] requiring high dosing to capture the minute effects; it shows that these antibodies are highly effective, but their inevitable high dosing makes them a significant clinical concern. There is also a possibility that these effects are placebo driven, as commonly found in such treatments [

22,

23,

24,

25].

The issue of ensuring bioavailability becomes more relevant since there are known mechanisms to improve the entry of antibodies into the brain. Antibodies can be readily made effective and safe by engineering them to go through transcytosis [

26] such as by binding the antibodies with transferrin protein or its N-methyl lobe using a cleavable linker to avoid exocytosis, increasing the half-life of these antibodies in the brain [

27].

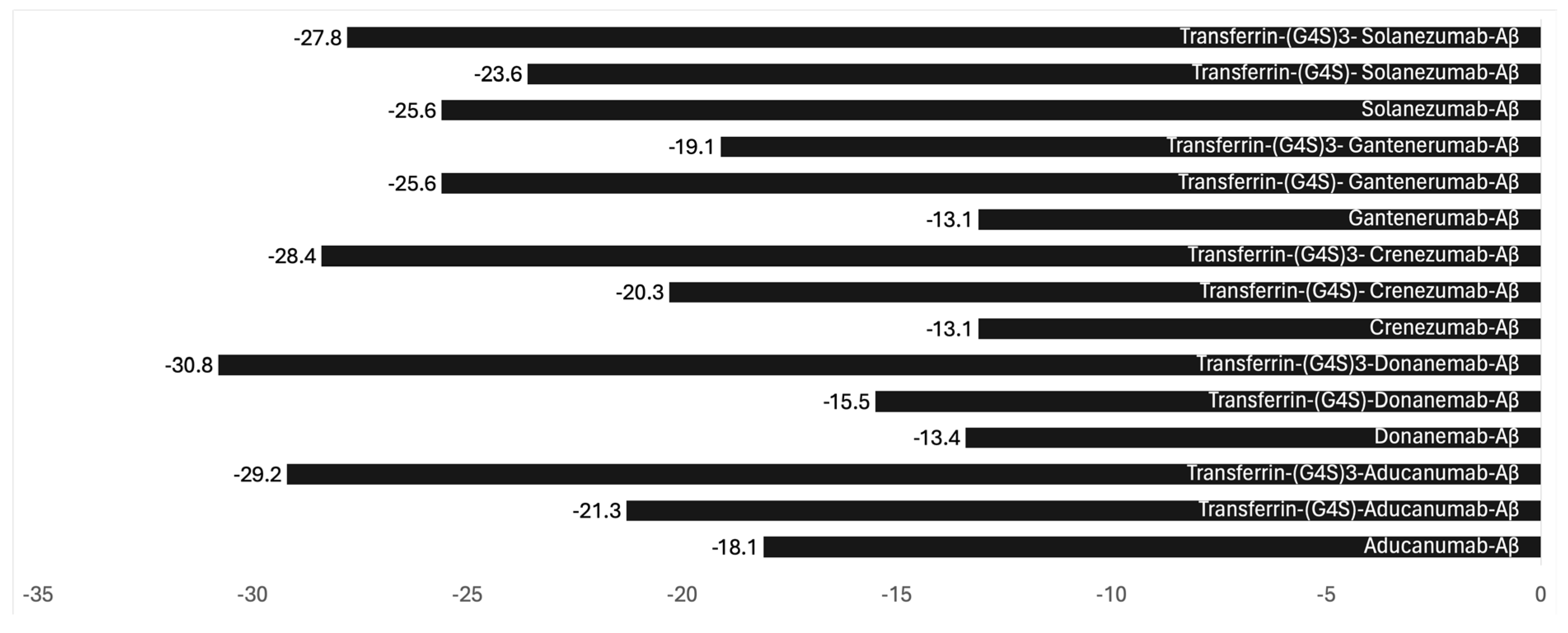

Binding antibodies with transferrin protein or N-methyl lobe with a cleavable linker is the most optimal engineering. To demonstrate that such binding does not adversely impact the efficacy of these antibodies, we employed bioinformatic modeling to investigate the impact of non-cleavable linkers (G4S)n) on antibody binding. Our examination, centered on steric hindrance, sought to understand the effects of the length of the linker and its influence on the binding avidity with the Aβ protein.

In addition to the clearance pathways, the behavior of antibodies in the brain can vary depending on their affinity for specific target antigens. For instance, antibodies designed to bind high-affinity receptors, such as those on transport mechanisms like the transferrin receptor or therapeutic targets such as amyloid-beta in Alzheimer’s disease, may experience enhanced retention due to these interactions [

28].

The complex formed between Aducanumab and Aβ has already been documented in the Protein Data Bank (PDB ID: 6c03)[

29,

30]. Leveraging this information, we conducted modeling experiments focusing on Aducanumab, an Alzheimer's disease treatment recently withdrawn from the market. Our methodology involved pre-processing and standardizing the antibody structure using UCSF Chimera, protein structure prediction using the AlphaFold2, followed by docking analysis using HADDOCK, both before and after linkage with transferrin via the (G4S)n linker. Subsequently, we evaluated binding affinity and interaction patterns through the PRODIGY server, paying particular attention to the linker's length. The binding parameters calculated included (

Figure 1):

Retention of antibodies within the brain can be further influenced by receptor recycling pathways, such as those involving the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn). Such mechanisms are more prominent in peripheral circulation, where FcRn is critical to antibody longevity. Still, their presence in the CNS is limited, and their effect on half-life is less pronounced [

31].

The exocytosis of antibodies can be reduced or prevented by linking the transcytosis agent with a cleavable linker that would break when the conjugate enters the brain [

32].

Antibody engineering may also involve removing the Fc region; however, this approach has several limitations. When the Fc (Fragment crystallizable) region of an antibody is removed, such as in antibody fragments like Fab (antigen-binding fragment) or scFv (single-chain variable fragment), the half-life within the brain can be significantly shortened [

33].

4. Conclusions

Current clinical trials of antibodies intended to treat neurological disorders are unethical, unless there is sufficient proof of their reaching into the brain. While the FDA must answer the New York Times report with evidence that it has followed the GAO recommendations in qualifying the IRBs, the FDA must revise clinical trial guidelines requiring proof of sufficient bioavailability at the target site, where known, to qualify exposing humans to such trials. The developers must adopt antibody engineering to enhance the transcytosis and preventable exocytosis of antibodies targeting the brain tissue. Additionally, such trials should take into consideration the possibility of significant placebo effects, common for these drugs [

27]. It is worth suggesting that the clinical effects reported with a minute of drug reaching out in the brain may be due to placebo effects since, they all end up with high toxic effects.

The need for effective treatment of neurological disorders is critical; developers chasing multibillion dollar markets are eager to test antibodies and finding they are failing and harming patients. The FDA must take actions to reduce human abuse in these trials and encourage development of scientifically rational products, which none of the current antibodies are.

Funding

No Funding was received.

Acknowledgments

SKN is thankful to Teresa Buracchio, MD, Director, Office of Neuroscience, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Food and Drug Administration for her comments on SKN FDA inquiry on this topic.

Conflicts of Interest

SKN is preparing a Citizen Petition to the US FDA to create a new guideline for clinical trials to include proof of bioavailability. SKN is a consultant to the FDA, EMA and MHRA, and a developer of mRNA products.

References

- Kessler WBaC. What Drugmakers Did Not Tell Volunteers in Alzheimer’s Trials https://www.nytimes.com/2024/10/23/health/alzheimers-drug-brain-bleeding.html: The New York Times; 2024 [.

- Giarratana, A.O.; Zheng, C.; Reddi, S.; Teng, S.L.; Berger, D.; Adler, D.; et al. APOE4 genetic polymorphism results in impaired recovery in a repeated mild traumatic brain injury model and treatment with Bryostatin-1 improves outcomes. Scientific Reports. 2020, 10, 19919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, L.K.; Kuan, Y.C.; Lin, H.W.; Hu, C.J. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer disease: A 2020-2023 update. J Biomed Sci. 2023, 30, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FDA. FDA Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-alzheimers-disease-treatment 2023 [.

- EMA. Refusal of the marketing authorisation for Leqembi (lecanemab) https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/smop-initial/questions-answers-refusal-marketing-authorisation-leqembi-lecanemab_en.pdf 2024 [.

- TGA-Australia. TGA's decision to not register lecanemab (LEQEMBI) https://www.tga.gov.au/news/news/tgas-decision-not-register-lecanemab-leqembi 2024 [.

- Mo, J.J.; Li, J.Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Feng, J.S. Efficacy and safety of anti-amyloid-β immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2017, 4, 931–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; et al. Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N Engl J Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baggett, D.; Olson, A.; Parmar, M.S. Novel approaches targeting α-Synuclein for Parkinson's Disease: Current progress and future directions for the disease-modifying therapies. Brain Disorders 2024, 16, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevigny, J.; Chiao, P.; Bussière, T.; Weinreb, P.H.; Williams, L.; Maier, M.; et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016, 537, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salloway, S.; Sperling, R.; Fox, N.C.; Blennow, K.; Klunk, W.; Raskind, M.; et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370, 322–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigurdsson, E.M. Tau Immunotherapies for Alzheimer's Disease and Related Tauopathies: Progress and Potential Pitfalls. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018, 64, S555–S565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manoutcharian, K.; Gevorkian, G. Recombinant Antibody Fragments for Immunotherapy of Parkinson's Disease. BioDrugs. 2024, 38, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, J.; Lee, G.; Ritter, A.; Zhong, K. Alzheimer's disease drug development pipeline: 2018. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2018, 4, 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrowitzki, S.; Lasser, R.A.; Dorflinger, E.; Scheltens, P.; Barkhof, F.; Nikolcheva, T.; et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017, 9, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenfeld, P.J.; Berger, B.; Reichel, E.; Danis, R.P.; Gress, A.; Ye, L.; et al. A Randomized Phase 2 Study of an Anti–Amyloid β Monoclonal Antibody in Geographic Atrophy Secondary to Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology Retina. 2018, 2, 1028–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landen, J.W.; Andreasen, N.; Cronenberger, C.L.; Schwartz, P.F.; Börjesson-Hanson, A.; Östlund, H.; et al. Ponezumab in mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: Randomized phase II PET-PIB study. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions. 2017, 3, 393–401. [Google Scholar]

- Teng, E.; Manser, P.T.; Pickthorn, K.; Brunstein, F.; Blendstrup, M.; Sanabria Bohorquez, S.; et al. Safety and Efficacy of Semorinemab in Individuals With Prodromal to Mild Alzheimer Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. 2022, 79, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doody, R.S.; Thomas, R.G.; Farlow, M.; Iwatsubo, T.; Vellas, B.; Joffe, S.; et al. Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2014, 370, 311–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K. Bioavailability as Proof to Authorize the Clinical Testing of Neurodegenerative Drugs—Protocols and Advice for the FDA to Meet the ALS Act Vision. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25, 10211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouhi, A.; Pachipulusu, V.; Kapenstein, T.; Hu, P.; Epstein, A.L.; Khawli, L.A. Brain Disposition of Antibody-Based Therapeutics: Dogma, Approaches and Perspectives. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitriu, A.; Popescu, B.O. Placebo effects in neurological diseases. J Med Life. 2010, 3, 114–121. [Google Scholar]

- Oken, B.S. Placebo effects: Clinical aspects and neurobiology. Brain. 2008, 131, 2812–2823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peciña, M.; Zubieta, J.-K. Molecular Mechanisms of Placebo Responses In Humans. Molecular psychiatry. 2014, 20, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niazi, S.K. A Modern View of Placebo Interventions: From Comparative Clinical Trials to Novel Therapies to Quantum Tunnelling. Preprints: Preprints; 2024.

- Niazi, S.K.; Mariam, Z.; Magoola, M. Engineered Antibodies to Improve Efficacy against Neurodegenerative Disorders. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25, 6683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niazi, S.K. Non-Invasive Drug Delivery across the Blood–Brain Barrier: A Prospective Analysis. Pharmaceutics. 2023, 15, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tien, J.; Leonoudakis, D.; Petrova, R.; Trinh, V.; Taura, T.; Sengupta, D.; et al. Modifying antibody-FcRn interactions to increase the transport of antibodies through the blood-brain barrier. MAbs. 2023, 15, 2229098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marathe, P.H.; Shyu, W.C.; Humphreys, W.G. The use of radiolabeled compounds for ADME studies in discovery and exploratory development. Curr Pharm Des. 2004, 10, 2991–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, J.W.; Qian, F.; Smith, B.A.; Quan, C.; Kilambi, K.P.; Bush, M.W.; et al. Structural and kinetic basis for the selectivity of aducanumab for aggregated forms of amyloid-β. Scientific Reports. 2018, 8, 6412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelke, C.; Spatola, M.; Schroeter, C.B.; Wiendl, H.; Lünemann, J.D. Neonatal Fc Receptor-Targeted Therapies in Neurology. Neurotherapeutics. 2022, 19, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Arashida, N.; Fujii, T.; Shikida, N.; Ito, K.; Shimbo, K.; et al. Exo-Cleavable Linkers: Enhanced Stability and Therapeutic Efficacy in Antibody–Drug Conjugates. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024, 67, 18124–18138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roopenian, D.C.; Akilesh, S. FcRn: The neonatal Fc receptor comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007, 7, 715–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).