Introduction

A rare form of ectopic pregnancy, cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) has the potential to result in significant complications. The incidence of CSP is on the rise in conjunction with the increase in the rate of cesarean deliveries [

3]. This condition is particularly prevalent among women who have undergone a prior cesarean section, and it carries significant risks, including uterine rupture, abnormal placental adhesion, and excessive bleeding. The early diagnosis and treatment of CSP are of vital importance for the preservation of maternal health and fertility.

Although ultrasonography is a commonly employed diagnostic technique in cases of CSP, establishing a diagnosis during the early gestational weeks can prove challenging [

7]. Conventional ultrasonography may prove inadequate in the hands of inexperienced operators, particularly in the context of pregnancy implantation in the scar area. It is, therefore, crucial to employ supplementary techniques in order to establish an early and precise diagnosis in patients exhibiting symptoms suggestive of CSP. Elastosonography has recently emerged as a promising method for the diagnosis of CSP. By measuring the stiffness of the tissue it can assist in the detection of abnormalities in the scar area, thereby overcoming the limitations of conventional ultrasonography. The concurrent utilization of these two modalities can enhance the precision and dependability of CSP diagnosis, facilitating prompt referral of patients for suitable treatment.

This article will focus on the role and significance of elastosonography in the diagnosis of CSP. The current diagnostic methods for CSP will be evaluated in comparison, and the potential contribution of elastosonography to this diagnostic process will be discussed. Moreover, the potential of combining different diagnostic modalities to enhance diagnostic accuracy and improve patient care in CSP management will be assessed.

Material Ve Method

Study Design

This is a prospective cohort study that includes patients admitted with CSP by cesarean section in our clinic between October 2023 and January 2024. It will be analyzed retrospectively.

Patient Selection

Sixty-one patients with a history of previous cesarean section, between 6-12 weeks of gestational age, and CSP findings on transvaginal ultrasonography (empty uterine cavity, closed internal os, gestational sac located between myometrium and bladder) were included in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with a history of at least one previous cesarean section.

Patients between 6-12 weeks of gestation.

Patients with CSP findings on transvaginal ultrasonography (empty uterine cavity, closed internal os, gestational sac located between myometrium and bladder).

Patients who can give written informed consent.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with a gestational week less than six or greater than 12.

Patients who do not show signs of CSP on transvaginal ultrasonography.

Patients with conditions that preclude elastosonography (e.g., extreme obesity, infection at the scar site).

Patients who refused to participate in the study or were unable to give written informed consent.

Patients lost to follow-up during the study.

Patients with pregnancy complications (e.g., bleeding, uterine rupture).

Patients with other serious health conditions (e.g., heart disease, renal failure).

Data Collection

Demographic characteristics (age, gestational week, body mass index, parity, number of previous cesarean sections) were recorded. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography was performed in all patients. The degree of stiffness (strain rate) of the scar area was measured by elastosonography in patients diagnosed with CSP.

Elastosonography

Elastosonography was performed by an experienced radiologist using Mindray DC-80 ultrasonography device sound touch Elastography and sound touch Quantification software. Compression was applied to the scar area from 5 different points, and strain rates were recorded and averaged.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was the diagnostic accuracy of elastosonography in the diagnosis of CSP.

Secondary outcome measures were the relationship between strain rates measured by elastosonography and demographic characteristics and the variation of strain rates with gestational week.

Our study was designed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval of our study was obtained from Mardin Artuklu University ethics committee (Study Ethics Committee no: 2024/9-11). The patients included in the study were informed, and written informed consent was obtained.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 15.0 for Windows program was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were given as numbers and percentages for categorical variables and mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median for numerical variables.

The diagnostic accuracy of elastosonography in the diagnosis of CSP will be evaluated by ROC curve analysis, and the area under the curve (AUC) will be calculated.

The relationship between strain rates and demographic characteristics will be analyzed using the independent sample t-test, Mann-Whitney U test, ANOVA, or Kruskal-Wallis test.

The change in strain rates with the gestational week will be analyzed using repeated measures, such as the ANOVA or Friedman test. The relationship between elastosonography and ultrasonography findings will be analyzed using a chi-square test. The significance level will be accepted as p < 0.05.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the patients included in the study are presented in

Table 1.

The mean age of the 61 cesarean scar pregnancy patients included in the study was 32 years, the mean gestational age was 8.4 weeks, the mean BMI was 27.2, the mean parity was 1.9, and the mean number of previous cesarean sections was 1.3. The elasticity of scar tissue decreased as the gestational week increased (p = 0.003). There was no significant correlation between age, BMI, parity, and number of previous cesarean sections and elastosonography findings (p>0.05).

In the study, elastosonographic parameters such as gestational sac strain ratio, myometrium shear wave velocity, and scar stiffness were found to be statistically significant in the diagnosis of CSP (p<0.05). On the other hand, parameters such as beta-hCG and fetal heart rate did not make a significant difference in the diagnosis of CSP (p>0.05).

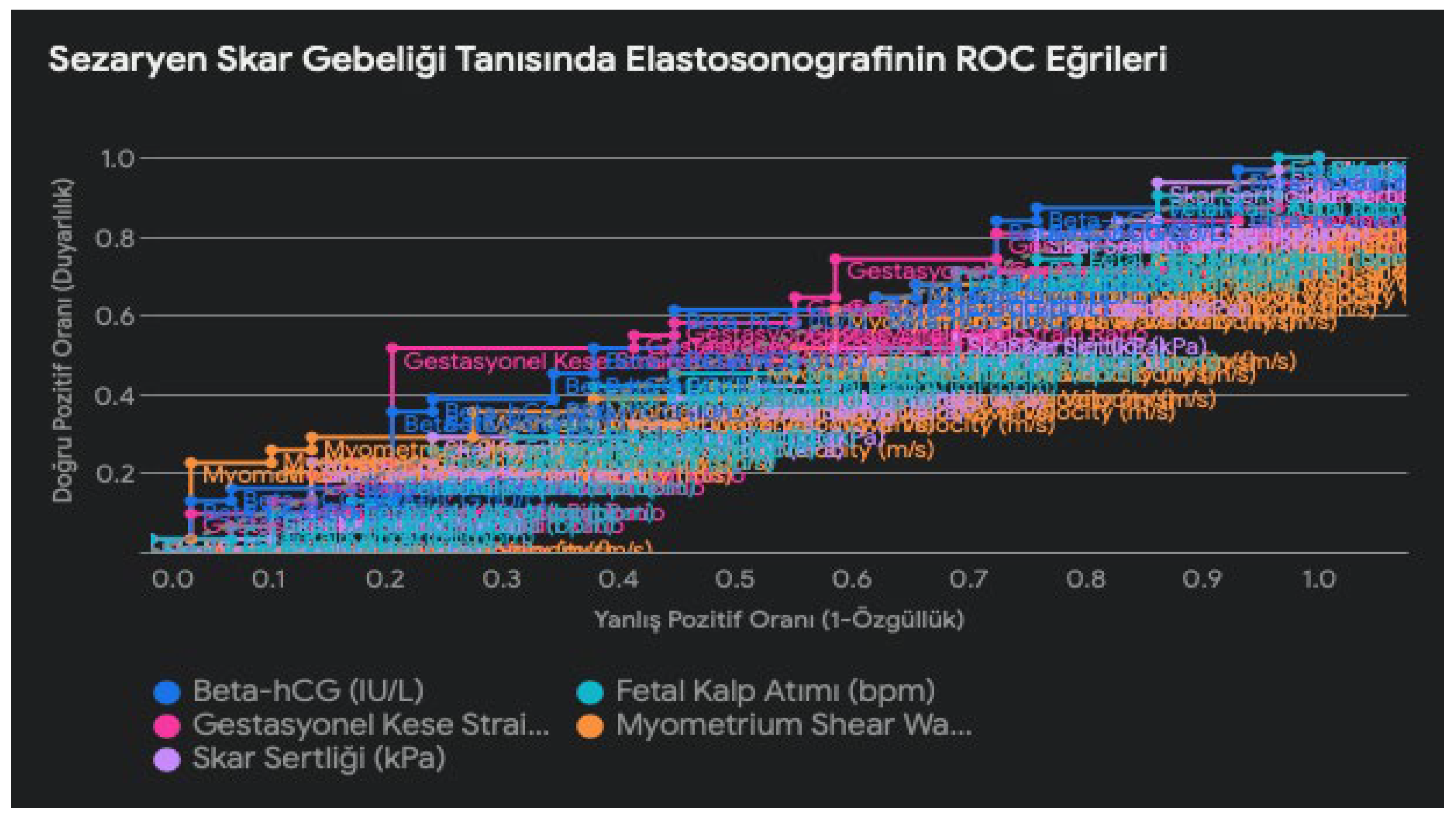

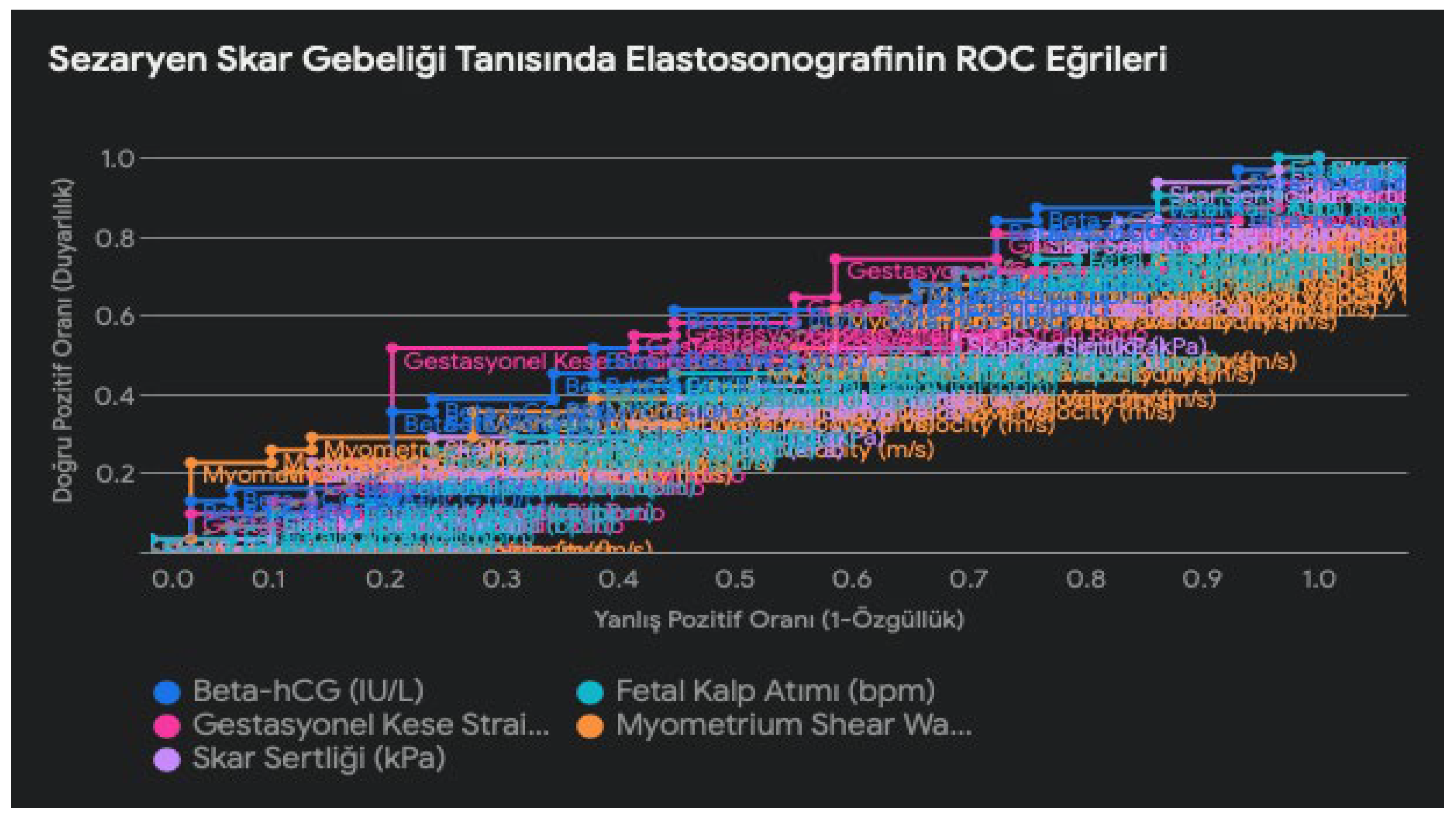

ROC curves show that elastosonography has clinically significant discriminatory power in the diagnosis of cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP). In particular, the gestational sac strain ratio (GCSR) parameter performed better in the diagnosis of CSP with a higher AUC (area under the curve) value (0.57) compared to the other parameters. However, this value is close to 0.5, suggesting that GCSR alone may not be sufficient to be used as a diagnostic test.

Other elastosonographic parameters, such as myometrial shear wave velocity (MSWV) and scar stiffness, were also significant in the diagnosis of CSP (AUC: 0.49 and 0.46, respectively). Evaluation of these parameters together with GCSR may improve diagnostic accuracy and provide a more comprehensive approach to the diagnosis of CSP.

On the other hand, conventional parameters such as beta-hCG and fetal heart rate did not show as strong discrimination power as elastosonography in the diagnosis of CSP (AUC: 0.55 and 0.46). In this case, the analysis of ROC curves showed that elastosonography has a better discrimination power in the diagnosis of CSP than conventional ultrasound.

Discussion

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication characterized by the implantation of pregnancy into the cesarean scar [

8,

9]. Early diagnosis and treatment are critical to prevent serious complications such as uterine rupture and massive bleeding. Although conventional ultrasonography is widely used, it may be insufficient in some cases, especially in the evaluation of scar tissue [

2,

10]. In recent years, advanced imaging techniques such as elastosonography have contributed to improving the diagnostic process by offering promising results in the diagnosis of CSP [

2,

10,

11].

Elastosonography has gained attention in recent years as a non-invasive imaging technique for assessing tissue elasticity. Investigated as a complementary tool to conventional ultrasound in the evaluation of scar pregnancy, elastosonography offers the potential to provide additional information about the structural characteristics of the affected area.

This study evaluated the efficacy of elastosonography in the diagnosis of CSP compared to conventional ultrasound and other imaging modalities. The study found that scar tissue elasticity decreased with increasing gestational age (p = 0.003). No significant correlation was found between age, body mass index, parity, and number of previous cesarean sections and elastosonographic findings. The results suggest that elastosonographic parameters such as gestational sac strain rate (GCSR), myometrial shear wave velocity (MSWV), and scar tissue stiffness are statistically significant in the diagnosis of CSP [

9,

11]. In contrast, traditional parameters such as beta-hCG and fetal heart rate showed no significant difference in the diagnosis of CSP. These findings suggest that elastosonography is a promising method for the early and reliable detection of CSP [

12].

Shear wave elastography (SWE), a specific application of elastosonography, has been used to assess placental function in pregnancies with complications such as preeclampsia [

13]. Similarly, the use of elastosonography in the evaluation of scar pregnancy may improve diagnostic accuracy by providing valuable information about the integrity and characteristics of the uterine scar.

Conventional ultrasonography, especially transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), still plays an important role in the diagnosis of CSP [

2]. TVUS provides high-resolution imaging and is an optimal method for the evaluation of suspected cases of CSP. The combined use of grayscale and color Doppler ultrasound is recommended for the diagnosis of CSP [

14]. Some experts suggest that in addition to TVUS, transabdominal ultrasonography with a full bladder may be useful to obtain a panoramic view of the uterus and to assess the relationship between the gestational sac and the bladder [

1].

ROC curve analysis revealed that elastosonography has a clinically significant discriminative power in the diagnosis of pregnancy in cesarean scar. In particular, the gestational sac strain rate parameter had a higher area under the curve (AUC) value compared to the other parameters, suggesting that it may be a promising diagnostic marker. However, the AUC value was close to 0.5, indicating that gestational sac strain rate alone may not be a sufficient diagnostic test [

15,

16].

The advantages of elastosonography are clear: the ability to measure the elasticity of scar tissue, which decreases as pregnancy progresses, allows early and accurate diagnosis. The fact that it is not affected by factors such as age and BMI increases its reliability. Conventional ultrasound, on the other hand, focuses on evaluating anatomical structures and may be inadequate in complex cases such as CSP [

1].

However, conventional ultrasonography (especially transvaginal ultrasound-TVUS) still plays an important role in the diagnosis of CSP. TVUS provides high-resolution imaging and is an optimal method for the evaluation of suspected cases of CSP [

17]. The combined use of grayscale and color Doppler ultrasound is recommended for the diagnosis of CSP. Some experts suggest that in addition to TVUS, transabdominal ultrasonography with a full bladder may be useful to obtain a panoramic view of the uterus and to assess the relationship between the gestational sac and the bladder [

18].

In addition, although conventional ultrasound remains the first-line diagnostic tool for scar pregnancy, its limitations in certain scenarios have been recognized. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has also been used in the diagnosis of scar pregnancy due to its superior soft tissue resolution and ability to visualize the endometrium, attachment site, and myometrial structures of the affected area [

19]. In this case, magnetic resonance imaging has led to a high accuracy rate in the diagnosis of CSP [

20]. MRI can be used in suspicious or complex cases when a definitive diagnosis cannot be made with conventional ultrasound or when myometrial invasion is suspected [

21]. MRI is a superior method for assessing the extent of myometrial involvement, the depth of placental invasion, and its relationship to surrounding tissues [

21]. However, the high cost and limited accessibility of MRI may prevent its widespread use in all healthcare settings.

The integration of elastosonography as a complementary diagnostic approach may help overcome some of the limitations associated with conventional imaging techniques. By providing additional information on the mechanical properties of scar tissue, elastosonography could potentially enhance clinicians’ ability to accurately differentiate wound pregnancy from other conditions, leading to more timely and appropriate management interventions.

Looking into the Future: Artificial Intelligence and CSP Diagnosis

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies has revolutionized the medical field. Especially in the field of radiology and imaging, AI-based diagnostic systems play an important role in the early diagnosis and treatment planning of diseases. The potential of AI in the diagnosis of CSP is also very high. By analyzing data from various imaging modalities such as elastosonography, ultrasound, and MRI, AI algorithms can help detect CSP early and accurately. In addition, by evaluating various risk factors, AI can identify patients at high risk of developing CSP and help create personalized follow-up and treatment plans.

Consequently, a multimodal approach to the diagnosis and management of CSP is optimal. Conventional ultrasound (especially TVUS) can be used for initial evaluation and screening, while MRI can be used in suspicious or complex cases. Elastosonography can be used as a complementary tool, especially for early diagnosis and assessment of scar tissue elasticity. The combination of these three modalities offers an important opportunity for early diagnosis, accurate classification, and personalized treatment planning of CSP. In the future, even greater advances in the diagnosis of CSP are expected with the incorporation of artificial intelligence technologies.

Limitations of the Study

Our study has several limitations. First, the relatively small size of our study cohort may limit the generalizability of our results. Second, because elastosonography is a relatively new technique, the lack of standardization between different devices and probes may affect the results. Finally, only a few elastographic parameters were evaluated in this study. Future studies should be designed to include different elastographic parameters in a larger patient population.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-enabled technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Google Gemini for sentence correction. After using this service, the authors reviewed and edited the content as necessary and took full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Monteagudo, A.; Santos, R.; Tsymbal, T.; Pineda, G.; Arslan, A.A. The diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of cesarean scar pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, 44.e1–44.e13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotas, M.A.; Haberman, S.; Levgur, M. Cesarean Scar Ectopic Pregnancies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2006, 107, 1373–1381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s Health. Caesarean section (NICE clinical guideliine 132). Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) Press: London, UK, 2011; 180–195.

- Vikhareva Osser, O.; Valentin, L. Clinical importance of appearance of cesarean hysterotomy scar at transvaginal ultrasonography in nonpregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2011, 117, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Cal`ı G, D’Antonio F, Agten AK. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: Patient Counseling and Management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2019, 46, 813–828.

- Kaelin Agten A, Cali G, Monteagudo A, Oviedo J, Ramos J, Timor-Tritsch I. The clinical outcome of cesarean scar pregnancies implanted ‘‘on the scar’’ versus ‘‘in the niche’’. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 216: 510.e1–6.

- Jurkovic D, Hillaby K, Woelfer B, Lawrence A, Salim R, Elson CJ. First trimester diagnosis and management of pregnancies implanted into the lower uterine segment Cesarean section scar. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003; 21, 220–227.

- Timor-Tritsch, I.E.; Monteagudo, A.; Calì, G.; D’antonio, F.; Agten, A.K. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 2019, 46, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pegu, B.; Thiagaraju, C.; Nayak, D.; Subbaiah, M. Placenta accreta spectrum-a catastrophic situation in obstetrics. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2021, 64, 239–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stănculescu, R.V.; Brătilă, E.; Socolov, D.G.; Russu, M.C.; Bauşic, V.; Chirculescu, R.; Coroleucă, C.A.; Pristavu, A.I.; Dragomir, R.E.; Papuc, P.; et al. Update on placenta accreta spectrum disorders by considering epidemiological factors, ultrasound diagnosis and pathological exam – literature review and authors’ experience. Romanian J. Morphol. Embryol. 2022, 63, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.S.-Y.; Chan, C.-P. The sonographic appearance and obstetric management of placenta accreta. Int. J. Women's Heal. 2012, 4, 587–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- di Pasquo, E.; Kiener, A.J.O.; DallAsta, A.; Commare, A.; Angeli, L.; Frusca, T.; Ghi, T. Evaluation of the uterine scar stiffness in women with previous Cesarean section by ultrasound elastography: A cohort study. Clin. Imaging 2020, 64, 53–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cimsit, C.; Yoldemir, T.; Akpinar, I.N. Shear Wave Elastography in Placental Dysfunction. J. Ultrasound Med. 2015, 34, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Yang, M.; Wu, Q. Application of ultrasonography in the diagnosis and treatment of cesarean scar pregnancy. Clin. Chim. Acta 2018, 486, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seliger, G.; Chaoui, K.; Lautenschläger, C.; Jenderka, K.-V.; Kunze, C.; Hiller, G.G.R.; Tchirikov, M. Ultrasound elastography of the lower uterine segment in women with a previous cesarean section: Comparison of in-/ex-vivo elastography versus tensile-stress-strain-rupture analysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2018, 225, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varma, T.R. The value of ultrasonic B-scanning in diagnosis when bleeding is present in early pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1972, 114, 607–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rizk, B.R.M.B.; Puscheck, E.E.; Abbasy, A.; Abuzeid, M.I.; Abuzeid, O.M.; Allahbadia, G.N.; Arora, S.; Awonuga, A.O.; Azmy, O.M.; Badawy, S.Z.A.; et al. Ultrasound diagnosis of cesarean scar ectopic pregnancy; Cambridge University Press (CUP): Cambridge, United Kingdom, 2014; pp. 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, N.; Tulandi, T. Cesarean Scar Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2017, 24, 731–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Jing, Z.; Lin, L.; Li, X. Comparison of diagnostic accuracy of three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of scar pregnancy. Pak. J. Med Sci. 2022, 38, 1743–1747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, X.; Ding, R.; Peng, L.; Liu, H.; Zhu, Y. Diagnostic performance of magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasonography on the detection of cesarean scar pregnancy. Medicine 2021, 100, e27532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alamo, L.; Vial, Y.; Denys, A.; Andreisek, G.; Meuwly, J.-Y.; Schmidt, S. MRI findings of complications related to previous uterine scars. Eur. J. Radiol. Open 2018, 5, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic characteristics.

Table 1.

Patients’ demographic characteristics.

| |

n |

Mean±SD |

Min-Max (Median) |

p |

| Age (year) |

61 |

31.8 ± 5.1 |

30 (22-45) |

> 0.05 |

| Gestational Week (weeks) |

61 |

8.4 ± 1.5 |

8 (6-12) |

0,003 |

| BMI (kg/m²) |

61 |

27.2 ± 3.8 |

26 (21-37) |

> 0.05 |

| Parity |

61 |

1.9 ± 1.1 |

2 (1-5) |

> 0.05 |

| Previous Number of Caesarean sections |

61 |

1.3 ± 0.5 |

1 (1-3) |

> 0.05 |

Table 2.

Elastosonographic values in CSP.

Table 2.

Elastosonographic values in CSP.

| Parameter |

Mean ± SD |

P Value |

Significance Level |

| Gestational Sac Strain Ratio |

2.5 ± 0.8 |

0,03 |

p < 0.05 |

| Myometrium Shear Wave Velocity (m/s) |

3.2 ± 1.1 |

0,01 |

p < 0.05 |

| Scar Hardness (kPa) |

85 ± 20 |

<0,001 |

p < 0.001 |

| Beta-hCG (IU/L) |

15000 ± 5000 |

0,25 |

> 0.05 |

| Fetal Heart Rate (bpm) |

140 ± 15 |

0,1 |

> 0.05 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).