Submitted:

04 November 2024

Posted:

06 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

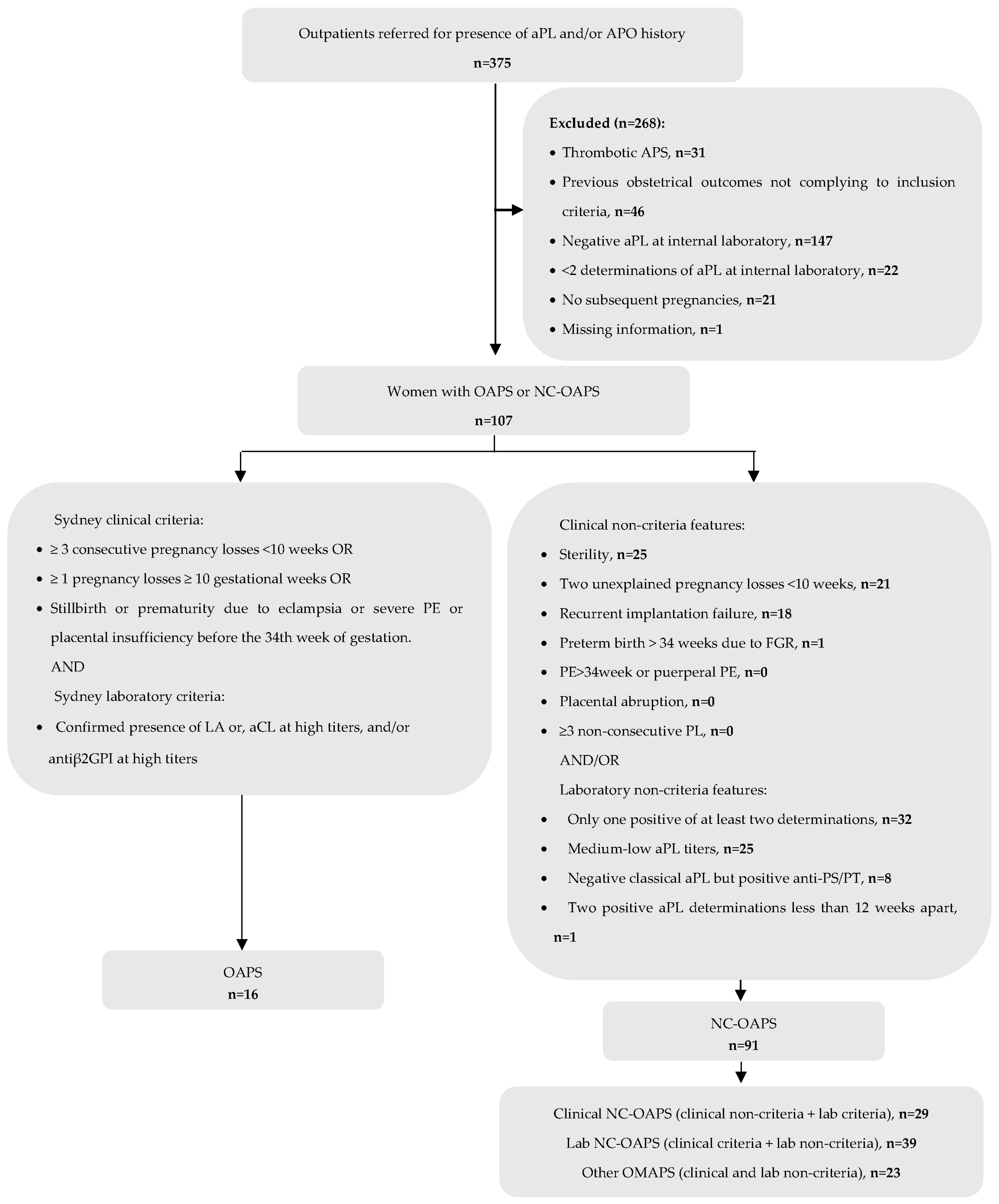

2.3. Exclusion Criteria (Figure 1):

2.4. Recorded Information and Definitions

- early PL: spontaneous PL before week 10 of gestation

- late PL: spontaneous PL of a morphologically normal fetus at or beyond week 10 of gestation

- PE or eclampsia during gestation or puerperium

- placental abruption

- FGR: estimated fetal weight below the 3rd percentile for a given gestational age, or below the 10th percentile associated with doppler abnormalities

- premature delivery (before 37 weeks of gestation) because of placental vasculopathy

- low birthweight (under 2500 grams)

- neonatal death before hospital discharge due to complications of prematurity and/or placental insufficiency.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Patients with NC-OAPS

3.2. Subsequent Pregnancies in Patients with NC-OAPS: Treatment and Outcomes

3.3. Comparison Between NC-OAPS and OAPS Groups

3.4. Risk Factors for Unexplained Pregnancy Loss

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, W.A.; Gharavi, A.E.; Koike, T.; Lockshin, M.D.; Branch, D.W.; Piette, J.C.; et al. International consensus statement on preliminary classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome: report of an international workshop. Arthritis Rheum 1999, 42, 1309–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyakis, S.; Lockshin, M.D.; Atsumi, T.; Branch, D.W.; Brey, R.L.; Cervera, R.; et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006, 4, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhaiya, M.; Zuily, S.; Naden, R.; Hendry, A.; Manneville, F.; Amigo, M.C.; et al. The 2023 ACR/EULAR Antiphospholipid Syndrome Classification Criteria. Arthritis Rheumatol 2023, 75, 1687–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires da Rosa, G.; Bettencourt, P.; Rodriguez-Pinto, I.; Cervera, R.; Espinosa, G. "Non-criteria" antiphospholipid syndrome: A nomenclature proposal. Autoimmun Rev 2020, 19, 102689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijotas-Reig, J.; Esteve-Valverde, E.; Ferrer-Oliveras, R.; Saez-Comet, L.; Lefkou, E.; Mekinian, A.; et al. Comparative study of obstetric antiphospholipid syndrome (OAPS) and non-criteria obstetric APS (NC-OAPS): report of 1640 cases from the EUROAPS registry. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020, 59, 1306–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chighizola, C.B.; Raimondo, M.G.; Meroni, P.L. Does APS Impact Women's Fertility? Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vomstein, K.; Voss, P.; Molnar, K.; Ainsworth, A.; Daniel, V.; Strowitzki, T.; et al. Two of a kind? Immunological and clinical risk factors differ between recurrent implantation failure and recurrent miscarriage. J Reprod Immunol 2020, 141, 103166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadimitriou, E.; Boutzios, G.; Mathioudakis, A.G.; Vlahos, N.F.; Vlachoyiannopoulos, P.; Mastorakos, G. Presence of antiphospholipid antibodies is associated with increased implantation failure following in vitro fertilization technique and embryo transfer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2022, 17, e0260759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.F.; Xu, L.; Li, T.T.; Wu, Y.T.; Ma, W.W.; Ding, J.Y.; et al. Serum antiphospholipid antibody status may not be associated with the pregnancy outcomes of patients undergoing in vitro fertilization. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e29146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockshin, M.D.; Kim, M.; Laskin, C.A.; Guerra, M.; Branch, D.W.; Merrill, J.; et al. Prediction of adverse pregnancy outcome by the presence of lupus anticoagulant, but not anticardiolipin antibody, in patients with antiphospholipid antibodies. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 2311–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yelnik, C.M.; Laskin, C.A.; Porter, T.F.; Branch, D.W.; Buyon, J.P.; Guerra, M.M.; et al. Lupus anticoagulant is the main predictor of adverse pregnancy outcomes in aPL-positive patients: validation of PROMISSE study results. Lupus Sci Med 2016, 3, e000131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saccone, G.; Berghella, V.; Maruotti, G.M.; Ghi, T.; Rizzo, G.; Simonazzi, G.; et al. Antiphospholipid antibody profile based obstetric outcomes of primary antiphospholipid syndrome: the PREGNANTS study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017, 216, 525 e1–525 e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Chen, D.; Duan, X.; Li, L.; Tang, Y.; Peng, B. The association between antiphospholipid antibodies and late fetal loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2019, 98, 1523–1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Lim, W.; Crowther, M.; Garcia, D. A systematic review of the association between anti-beta-2 glycoprotein I antibodies and APS manifestations. Blood Adv 2021, 5, 3931–3936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meroni, P.L.; Borghi, M.O.; Grossi, C.; Chighizola, C.B.; Durigutto, P.; Tedesco, F. Obstetric and vascular antiphospholipid syndrome: same antibodies but different diseases? Nat Rev Rheumatol 2018, 14, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekinian, A.; Bourrienne, M.C.; Carbillon, L.; Benbara, A.; Noemie, A.; Chollet-Martin, S.; et al. Non-conventional antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with clinical obstetrical APS: Prevalence and treatment efficacy in pregnancies. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016, 46, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelo, D.E.; Cabrera-Marante, O.; Abad, M.; Rodriguez-Frias, E.A.; Naranjo, L.; Vazquez, A.; et al. Anti-Phosphatidylserine/Prothrombin Antibodies in Healthy Women with Unexplained Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. J Clin Med 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, F.; Wang, M.; Zeng, X.; Liu, L.; Wang, F. Preconception Non-criteria Antiphospholipid Antibodies and Risk of Subsequent Early Pregnancy Loss: a Retrospective Study. Reprod Sci 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alijotas-Reig, J.; Esteve-Valverde, E.; Anunciacion-Llunell, A.; Marques-Soares, J.; Pardos-Gea, J.; Miro-Mur, F. Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Management of Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Med 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnolato, F.; Gerosa, M.; Raimondo, M.G.; Comerio, C.; Bartoli, F.; Lonati, P.A.; et al. EUREKA algorithm predicts obstetric risk and response to treatment in women with different subsets of anti-phospholipid antibodies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2021, 60, 1114–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Fang, X.; Lu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Kwak-Kim, J. Anticardiolipin and/or anti-beta2-glycoprotein-I antibodies are associated with adverse IVF outcomes. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 986893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, Y.; Xia, X.; Wang, J.; Qian, Y.; Yuan, C.; et al. A retrospective study on IVF/ICSI outcomes in patients with persisted positive of anticardiolipin antibody: Effects of low-dose aspirin plus low molecular weight heparin adjuvant treatment. J Reprod Immunol 2022, 153, 103674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Devreese, K.M.J.; de Groot, P.G.; de Laat, B.; Erkan, D.; Favaloro, E.J.; Mackie, I.; et al. Guidance from the Scientific and Standardization Committee for lupus anticoagulant/antiphospholipid antibodies of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis: Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection and interpretation. J Thromb Haemost 2020, 18, 2828–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakos, G.; Bentow, C.; Mahler, M. A Clinical Approach for Defining the Threshold between Low and Medium Anti-Cardiolipin Antibody Levels for QUANTA Flash Assays. Antibodies (Basel) 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pires da Rosa, G.; Ferreira, E.; Sousa-Pinto, B.; Rodriguez-Pinto, I.; Brito, I.; Mota, A.; et al. Comparison of non-criteria antiphospholipid syndrome with definite antiphospholipid syndrome: A systematic review. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 967178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekinian, A.; Alijotas-Reig, J.; Carrat, F.; Costedoat-Chalumeau, N.; Ruffatti, A.; Lazzaroni, M.G.; et al. Refractory obstetrical antiphospholipid syndrome: Features, treatment and outcome in a European multicenter retrospective study. Autoimmun Rev 2017, 16, 730–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xi, F.; Cai, Y.; Lv, M.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Anticardiolipin Positivity Is Highly Associated With Intrauterine Growth Restriction in Women With Antiphospholipid Syndrome. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2020, 26, 1076029620974455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Yue, J.; Lu, Y.; Li, T.; Li, X.; Zhang, J.Y. Recurrent miscarriage and low-titer antiphospholipid antibodies. Clin Rheumatol 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Taboada, V.M.; Blanco-Olavarri, P.; Del Barrio-Longarela, S.; Riancho-Zarrabeitia, L.; Merino, A.; Comins-Boo, A.; et al. Non-Criteria Obstetric Antiphospholipid Syndrome: How Different Is from Sidney Criteria? A Single-Center Study. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Deng, X.; Duan, H.; Zeng, L.; Zhou, J.; Liu, C.; et al. Clinical features associated with pregnancy outcomes in women with positive antiphospholipid antibodies and previous adverse pregnancy outcomes: a real-world prospective study. Clin Rheumatol 2021, 40, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carolis, S.; Tabacco, S.; Rizzo, F.; Giannini, A.; Botta, A.; Salvi, S.; et al. Antiphospholipid syndrome: An update on risk factors for pregnancy outcome. Autoimmun Rev 2018, 17, 956–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, S.; Sanna, G.; Murru, V.; Roccatello, D.; Khamashta, M.A.; Bertolaccini, M.L. The global anti-phospholipid syndrome score in primary APS. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2015, 54, 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, M.; Schreiber, K.; Costanzo, P.; Cecchi, I.; Roccatello, D.; Baldovino, S.; et al. The adjusted Global AntiphosPholipid Syndrome Score (aGAPSS) for risk stratification in young APS patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol 2017, 240, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, M.; Cecchi, I.; Schreiber, K.; Rubini, E.; Roccatello, D.; Cuadrado, M.J.; et al. Pregnancy success rate and response to heparins and/or aspirin differ in women with antiphospholipid antibodies according to their Global AntiphosPholipid Syndrome Score. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020, 50, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciascia, S.; Radin, M.; Sanna, G.; Cecchi, I.; Roccatello, D.; Bertolaccini, M.L. Clinical utility of the global anti-phospholipid syndrome score for risk stratification: a pooled analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018, 57, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Barrio-Longarela, S.; Martinez-Taboada, V.M.; Blanco-Olavarri, P.; Merino, A.; Riancho-Zarrabeitia, L.; Comins-Boo, A.; et al. Does Adjusted Global Antiphospholipid Syndrome Score (aGAPSS) Predict the Obstetric Outcome in Antiphospholipid Antibody Carriers? A Single-Center Study. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2022, 63, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandevelde, A.; Chayoua, W.; de Laat, B.; Gris, J.C.; Moore, G.W.; Musial, J.; et al. Semiquantitative interpretation of anticardiolipin and antibeta2glycoprotein I antibodies measured with various analytical platforms: Communication from the ISTH SSC Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibodies. J Thromb Haemost 2022, 20, 508–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | NC-OAPS patients (n=91) |

|---|---|

| Ethnicity, n (%): | |

| Caucasian | 81 (89.0) |

| Hispanic/ South American | 5 (5.5) |

| Maghrebi | 1 (1.1) |

| Asian | 3 (3.3) |

| Black | 1 (1.1) |

| BMI, mean (S.D.)a | 24.73 (4.61) |

| Smoking habits, n (%)a | 18 (20.0) |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 1 (1.1) |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1 (1.1) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 1 (1.1) |

| Presence of other autoimmune diseases, n (%): | 24 (26.4) |

| Autoimmune thyroiditis | 9 (9.8) |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 3 (3.3) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 2 (2.2) |

| Psoriasis | 2 (2.2) |

| Cutaneous lupus | 1 (1.1) |

| Systemic sclerosis | 1 (1.1) |

| Sjögren's syndrome | 1 (1.1) |

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disease | 1 (1.1) |

| Seronegative spondyloarthropathy | 1 (1.1) |

| Immune thrombocytopenic purpura | 1 (1.1) |

| IgA vasculitis | 1 (1.1) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1 (1.1) |

| Inherited thrombophilia, n (%) | 6 (6.6) |

| Previous APO | |

| 2 early pregnancy losses, n (%) | 22 (24.2) |

| ≥3 early pregnancy losses, n (%) | 22 (24.2) |

| ≥1 late pregnancy loss, n (%) | 16 (17.6) |

| Neonatal death (because of FGR/PE/prematurity), n (%) | 2 (2.2) |

| Preterm birth <34 weeks because of FGR, n (%) | 3 (3.3) |

| Preterm birth >34 weeks because of FGR, n (%) | 2 (2.2) |

| PE/eclampsia <34 weeks, n (%) | 2 (2.2) |

| PE/eclampsia >34 weeks, n (%) | 1 (1.1) |

| Placental abruption, n (%) | 2 (2.2) |

| Recurrent implantation failure, n (%) | 20 (22.0) |

| Unexplained sterility, n (%) | 30 (36.3) |

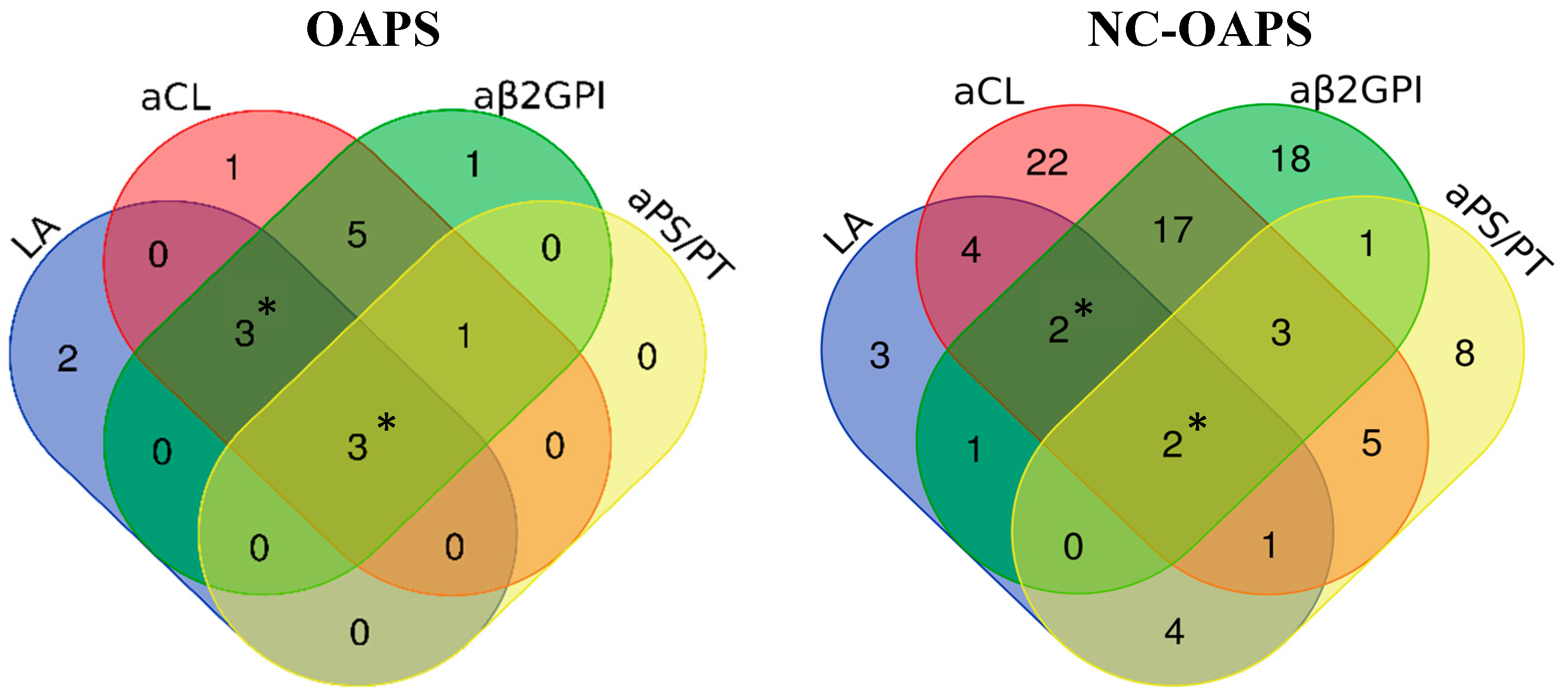

| Antiphospholipid antibodies subtypes | |

| Lupus anticoagulant, n (%) | 17 (18.7) |

| aCL IgM and/or IgG autoantibodies, n (%) | 56 (61.5) |

| aβ2GPI IgM and/or IgG autoantibodies, n (%) | 44 (48.4) |

| aPS/PT IgM and/or IgG autoantibodies, n (%)b | 24 (51.1) |

| Treatment | Subsequent pregnancies (n=119) |

| No treatment, n (%) | 1 (0.8) |

| LDA alone, n (%) | 12 (10.1) |

| LMWH alone, n (%) | 2 (1.7) |

| LDA plus LMWH, n (%) | 104 (87.4) |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 23 (19.3) |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 17 (14.3) |

| Obstetric and maternal outcomes | |

| Live births, n (%) | 98 (82.4) |

| Pregnancy loss <10w, n (%) | 18 (15.1) |

| Pregnancy loss 10-24w, n (%) | 2 (1.7) |

| Pregnancy loss >24w, n (%) | 0 (0) |

| Preeclampsia, n (%)c | 5 (5.2) |

| HELLP syndrome, n (%)c | 1 (1.0) |

| Placental abruption, n (%)c | 1 (1.0) |

| Fetal and neonatal outcomes | Neonates (n=101) |

| FGR, n (%)c | 9 (9.0) |

| Preterm birth related to PE/HELLP/FGR, n (%)c | 3 (3.0) |

| Low birthweight, n (%)c | 11 (11.5) |

| Neonatal death, n (%) | 1 (1.0) |

| OAPS (n=16) |

NC-OAPS (91) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and clinical characteristics | |||

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.201 | ||

| Caucasian | 12 (75.0%) | 81 (89.0%) | |

| Hispanic/ | 2 (12.5%) | 5 (5.5%) | |

| South American | |||

| Maghrebi | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| Asian | 1 (6.2%) | 3 (3.3%) | |

| Black | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.1%) | |

| BMI, mean (S.D.)* | 25.03 (6.10) | 24.73 (4.61) | 0.830 |

| Smoker, n (%)** | 1 (6.7) | 18 (20.0) | 0.296 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 1 (1.1) | 0.058 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.1) | 1.000 |

| Presence of other autoimmune diseases, n (%) | 4 (25.0) | 24 (26.4) | 1.000 |

| Inherited thrombophilia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 6 (6.6) | 0.588 |

| Age at first subsequent pregnancy, years, mean (S.D.) | 36.81 (6.41) | 36.86 (3.94) | 0.979 |

| Subsequent pregnancies per patient, mean (S.D.) | 1.5 (0.82) | 1.31 (0.59) | 0.261 |

| Previous obstetric history | |||

| Live births before study, n (%) | 7 (43.8) | 18 (19.8) | 0.053 |

| 2 early pregnancy losses, n (%) | 1 (6.2) | 22 (24.2) | 0.184 |

| ≥3 early pregnancy losses, n (%) | 3 (18.8) | 22 (24.2) | 0.758 |

| ≥1 late pregnancy loss, n (%) | 10 (62.5) | 16 (17.6) | 0.000 |

| Neonatal death (because of FGR/PE/prematurity), n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (2.2) | 0.105 |

| Previous preterm birth <34 weeks because of FGR, n (%) | 1 (6.2) | 3 (3.3) | 0.482 |

| Previous preterm birth >34 weeks because of FGR, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | 1.000 |

| PE/eclampsia <34 weeks, n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 2 (2.2) | 0.105 |

| PE/eclampsia >34 weeks, n (%) | 1 (6.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.278 |

| Placental abruption, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.2) | 1.000 |

| Recurrent implantation failure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 20 (22.0) | 0.038 |

| Unexplained sterility, n (%) | 2 (12.5) | 30 (36.3) | 0.062 |

| aPL profile | |||

| Subtypes of aPL | |||

| Lupus anticoagulant, n (%) | 8 (50.0) | 17 (18.7) | 0.011 |

| aCL autoantibodies, n (%) | 13 (81.2) | 56 (61.5) | 0.129 |

| IgM | 3 (23.1) | 14 (25.0) | 1.000 |

| IgG | 8 (61.5) | 37 (66.1) | 0.756 |

| IgM+IgG | 2 (15.4) | 5 (8.9) | 0.609 |

| aβ2GPI autoantibodies, n (%)* | 13 (86.7) | 44 (48.4) | 0.006 |

| IgM | 3 (23.1) | 17 (38.6) | 0.346 |

| IgG | 7 (53.8) | 24 (54.5) | 0.965 |

| IgM+IgG | 3 (23.1) | 3 (6.8) | 0.125 |

| aPS/PT autoantibodies, n (%)** | 4 (50.0) | 24 (51.1) | 1.000 |

| IgM | 3 (75.0) | 20 (85.7) | 1.000 |

| IgG | 0 (0) | 1 (4.2) | 1.000 |

| IgM+IgG | 1 (25.0) | 3 (12.5) | 0.481 |

| Number of positive aPL tests | |||

| In patients with aPS/PT determination (n=55): | |||

| Single positive, n (%) | 2 (25.0) | 27 (57.4) | 0.131 |

| Double positive, n (%) | 2 (25.0) | 14 (29.8) | 1.000 |

| Triple positive, n (%) | 1 (12.5) | 4 (8.5) | 0.559 |

| Four positive, n (%) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (4.3) | 0.018 |

| In patients without aPS/PT determination (n=52): | |||

| Single positive, n (%) | 2 (25.0) | 24 (54.5) | 0.248 |

| Double positive, n (%) | 3 (37.5) | 18 (40.9) | 1.000 |

| Triple positive, n (%) | 3 (37.5) | 2 (4.5) | 0.022 |

| aGAPSS *, n (%) |

0.003 |

||

| ≤5 | 4 (26.7) | 61 (67.0) | |

| >5 | 11 (73.3) | 30 (33.3) |

| OAPS n=24 |

NC-OAPS n=119 |

p value |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment regimen | |||

| No treatment, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.8) | 1.000 |

| LDA alone, n (%) | 3 (12.5) | 12 (10.1) | 0.718 |

| LMWH alone, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 2 (1.7) | 0.426 |

| LDA plus LMWH, n (%) | 20 (83.3) | 104 (87.4) | 0.527 |

| Additional treatments | |||

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 2 (8.3) | 23 (19.3) | 0.250 |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 2 (8.3) | 17 (14.3) | 0.741 |

| ART, n (%) | 6 (25.0) | 55 (46.6%) | 0.070 |

| Treatment doses | |||

| Aspirin 100mg, n (%) | 15 (62.5) | 103 (86.6) | 0.015 |

| Aspirin 150mg, n (%) | 8 (33.3) | 13 (10.1) | 0.009 |

| Prophylactic doses LMWH, n (%) | 15 (62.5) | 92 (77.3) | 0.127 |

| Intermediate doses LMWH, n (%) | 6 (25.0) | 10 (8.4) | 0.030 |

| Therapeutic doses LMWH, n (%) | 0 (0) | 4 (3.4) | 1.000 |

| Corticosteroids ≥10mg/day, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 13 (10.9) | 0.465 |

| Final pregnancy outcome | |||

| Live births, n (%) | 18 (75.0) | 98 (82.4) | 0.400 |

| Elective medical termination, n (%) | 1 (4.2) | 1 (0.8) | 0.308 |

| Pregnancy loss <10w, n (%) | 5 (20.8) | 18 (15.1) | 0.543 |

| Pregnancy loss 10-24w, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (1.7) | 1.000 |

| Pregnancy loss >24w, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Obstetric and maternal outcomes | |||

| Deliveries, n | 18 | 98 | |

| Cesarian section, n (%)a | 5 (29.4) | 51 (53.1) | 0.071 |

| Preeclampsia, n (%)b | 3 (16.7) | 5 (5.2) | 0.111 |

| HELLP, n (%)b | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Placental abruption, n (%)b | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| Maternal death, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Maternal thrombosis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 0 (0) | 4 (4.6) | 1.000 |

| Fetal and neonatal outcomes | |||

| Neonates, n | n=18 | n=101* | |

| Gestational Age (weeks), mean (SD) | 38.6 (1.88) | 38.791 (2.00) | 0.653 |

| FGR, n (%)c | 0 (0) | 9 (9.0) | 0.351 |

| Preterm birth related to PE/HELLP/FGR, n (%)c | 1 (5.6) | 3 (3.0) | 0.489 |

| <28 weeks | 0 | 1 | |

| 32-33.6 weeks | 1 | 0 | |

| 34-<37 weeks | 0 | 2 | |

| Birthweight (gr), mean (SD) | 3146 (506) | 3050 (550) | 0.491 |

| Low birthweight, n (%)c | 2 (11.1) | 11 (11.5) | 1.000 |

| Neonatal death, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.0) | 1.000 |

| PL of unknown cause (n=15) | Live birth (n=116) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and previous obstetric history | |||

| BMI, Kg/m2 | 0.416 | ||

| < 25 | 10 (71.4) | 65 (60.2) | |

| ≥ 25 | 4 (28.6) | 43 (39.8) | |

| Associated autoimmune disease, n (%) | 5 (33.3) | 30 (25.9) | 0.544 |

| Live births before study, n (%) | 4 (26.7) | 26 (22.4) | 0.747 |

| Live births before study if at least one previous pregnancy, n (%) | 4 (28.6) | 26 (26.8) | 1.000 |

| ≥ 4 previous PL | 3 (20) | 10 (8.6) | 0.171 |

| Age at subsequent pregnancy, years, n (%) | 0.385 | ||

| < 35 | 3 (20.0) | 39 (33.6) | |

| ≥ 35 | 12 (80.0) | 77 (66.4) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | 0.280 | ||

| OAPS | 4 (26.7) | 18 (15.5) | |

| NC-OAPS | 11 (73.3) | 98 (84.5) | |

| aGAPSS *, n (%) | 0.082 | ||

| ≤ 5 | 12 (80) | 65 (56.5) | |

| > 5 | 3 (20) | 50 (43.5) | |

| Laboratory features | |||

| Subtypes of aPL, n (%) | |||

| LA | 4 (26.7) | 29 (25.0) | 1.000 |

| aCL | 10 (66.7) | 76 (65.5) | 1.000 |

| aβ2GPI * | 5 (33.3) | 67 (58.3) | 0.068 |

| aPS/PT ** | 8 (72.7) | 28 (49.1) | 0.151 |

| Number of positive aPL tests | |||

| If aPS/PT not determined (n=63), n (%) | |||

| Single positive | 3 (75.0) | 28 (47.5) | 0.355 |

| Double positive | 1 (25.0) | 25 (43.1) | 0.633 |

| Triple positive | 0 (0) | 6 (10.2) | 1.000 |

| If aPS/PT determined (n=68), n (%) | |||

| Single positive | 4 (36.4) | 29 (50.9) | 0.378 |

| Double positive | 5 (45.5) | 16 (28.1) | 0.295 |

| Triple positive | 0 (0) | 5 (8.8) | 0.583 |

| Quadruple positive | 2 (18.2) | 7 (12.3) | 0.631 |

| Treatment regimen | |||

| LDA plus LMWH, n (%) | 12 (80.0) | 103 (88.8) | 0.395 |

| LDA alone, n (%) | 3 (20.0) | 9 (7.8) | 0.142 |

| Hydroxychloroquine, n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 19 (16.4) | 1.000 |

| Corticosteroids, n (%) | 2 (13.3) | 15 (12.9) | 1.000 |

| ART, n (%) | 6 (40.0) | 53 (46.1) | 0.656 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).