Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Survey of Pharmacy and Public Health Professionals—Overview and Data Analysis

2.1.1. Survey of Pharmacy Professionals

- ▪

- Explore the number of pharmacy professionals who have experience in leading public/population health projects or have completed/are undertaking additional public/population health training.

- ▪

- Explore the context in which pharmacists are currently involved in public/population health related roles (excluding nationally commissioned public health services through community pharmacy),

- ▪

- Understand the drivers and barriers associated with pharmacists undertaking public/population health roles.

2.1.2. Survey of Public Health Professionals

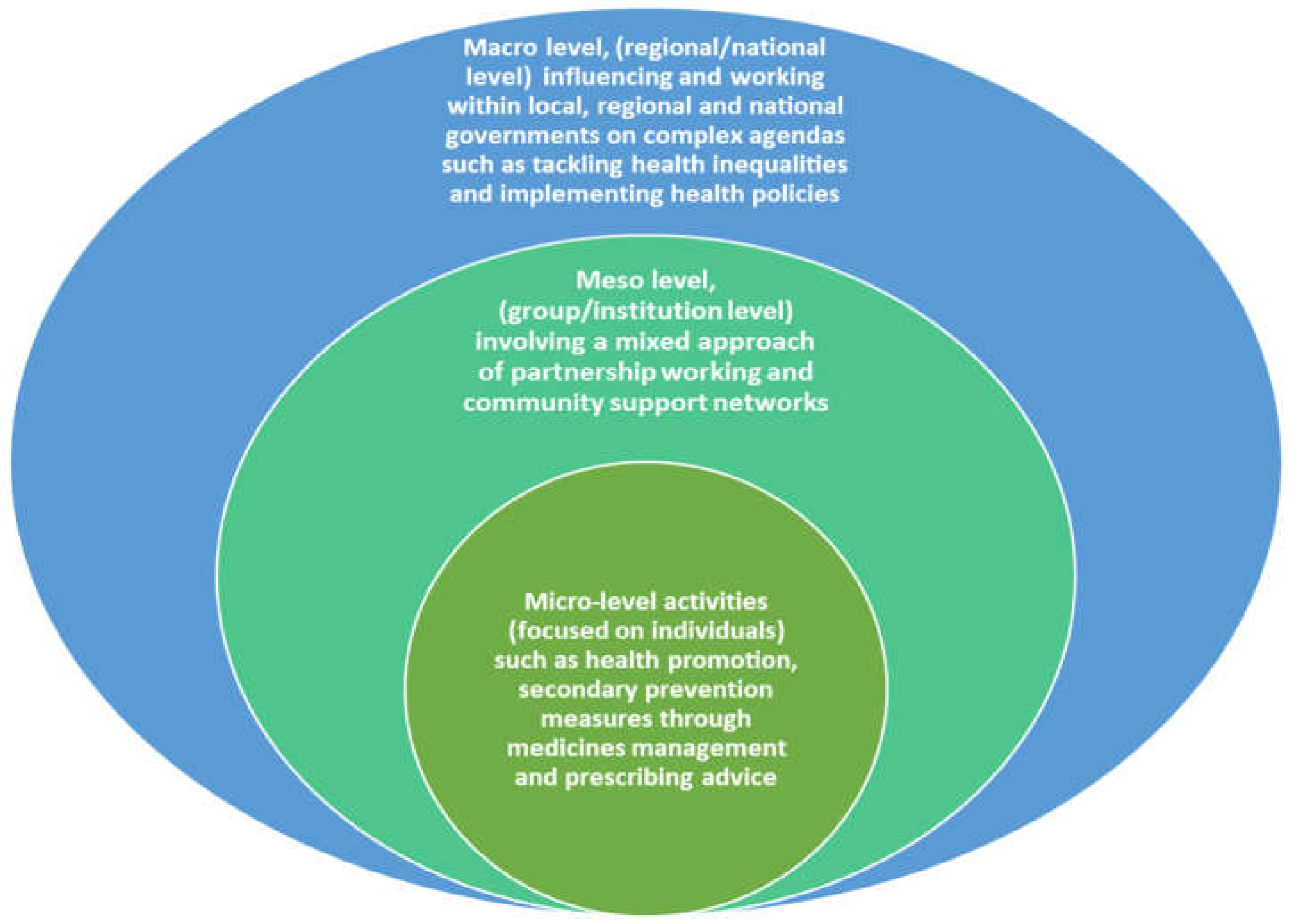

- The potential functions of public health that can benefit from pharmacists’ unique expertise including access to care, prevention services as well as pharmacotherapy, pharmacoepidemiology and economics,

- The contributions of pharmacy professionals to public/population health (in addition to traditionally/nationally commissioned community pharmacy services) that they were aware of in the four UK nations.

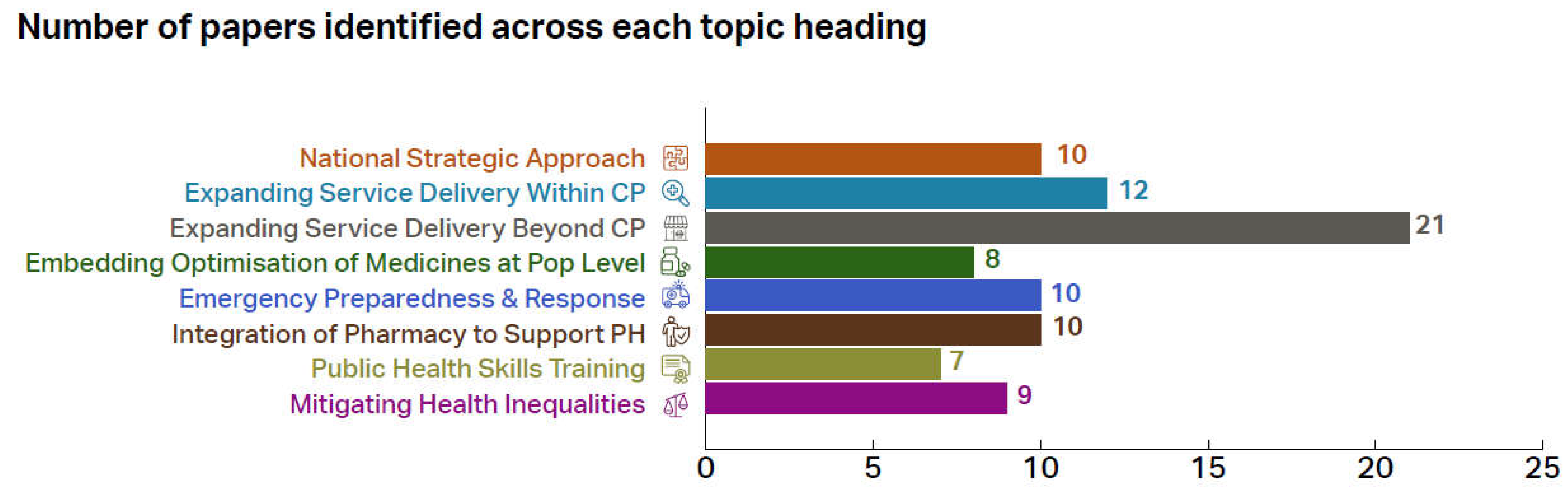

2.2. Call for Evidence

- National Strategic Approach

- Expanding Service Delivery within Community Pharmacy

- Expanding Service Delivery beyond Community Pharmacy

- Embedding Optimisation of Medicines at a Population Health Level

- Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response

- Integration of Pharmacy to Better Support Public Health Protection & Improvement Goals

- Public Health Skills and Training

- Mitigating Health Inequalities

2.3. Workshops

2.4. Ethics Approval and Consent

3. Results

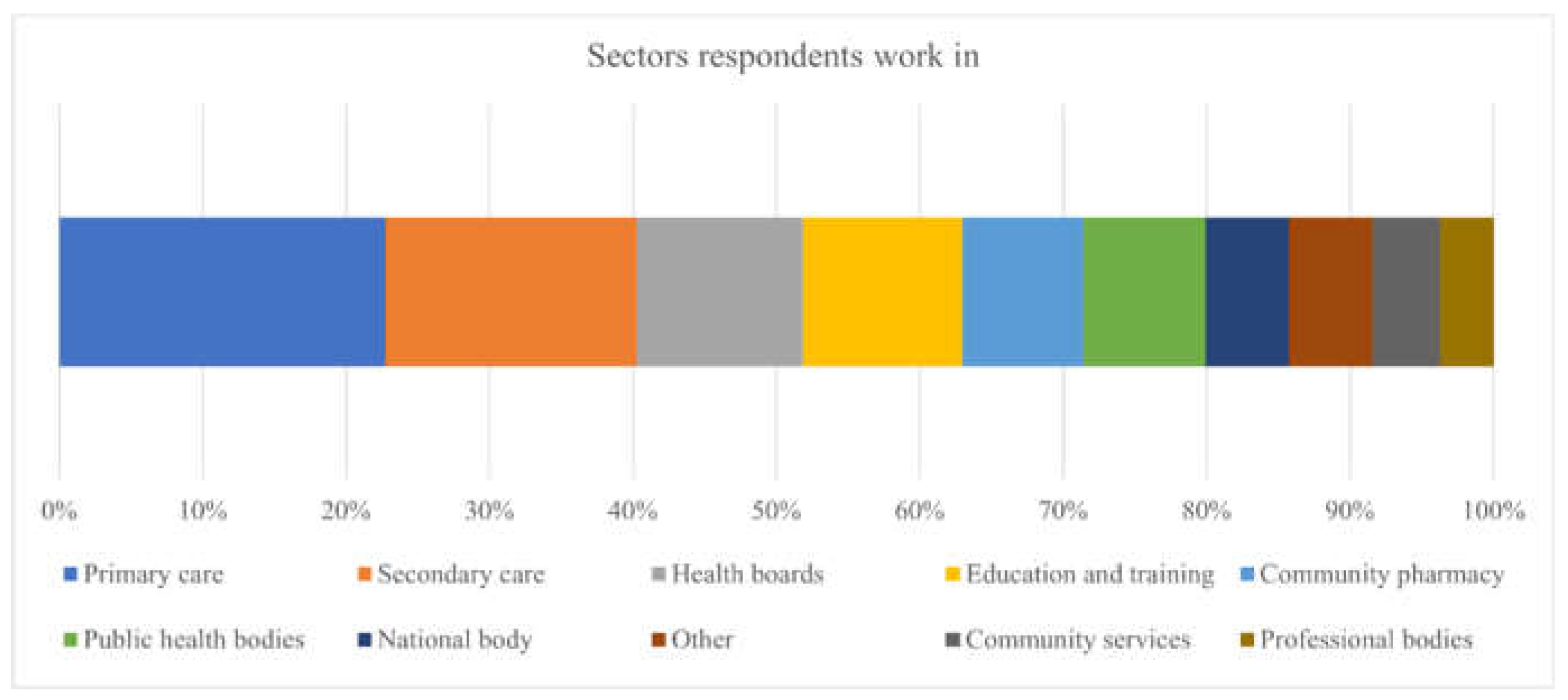

3.1. Survey of Pharmacy and Public Health Professionals

3.1.1. Survey of Pharmacy Professionals

3.1.1.1. Demographics

3.1.1.2. Public Health Qualifications and Motivation

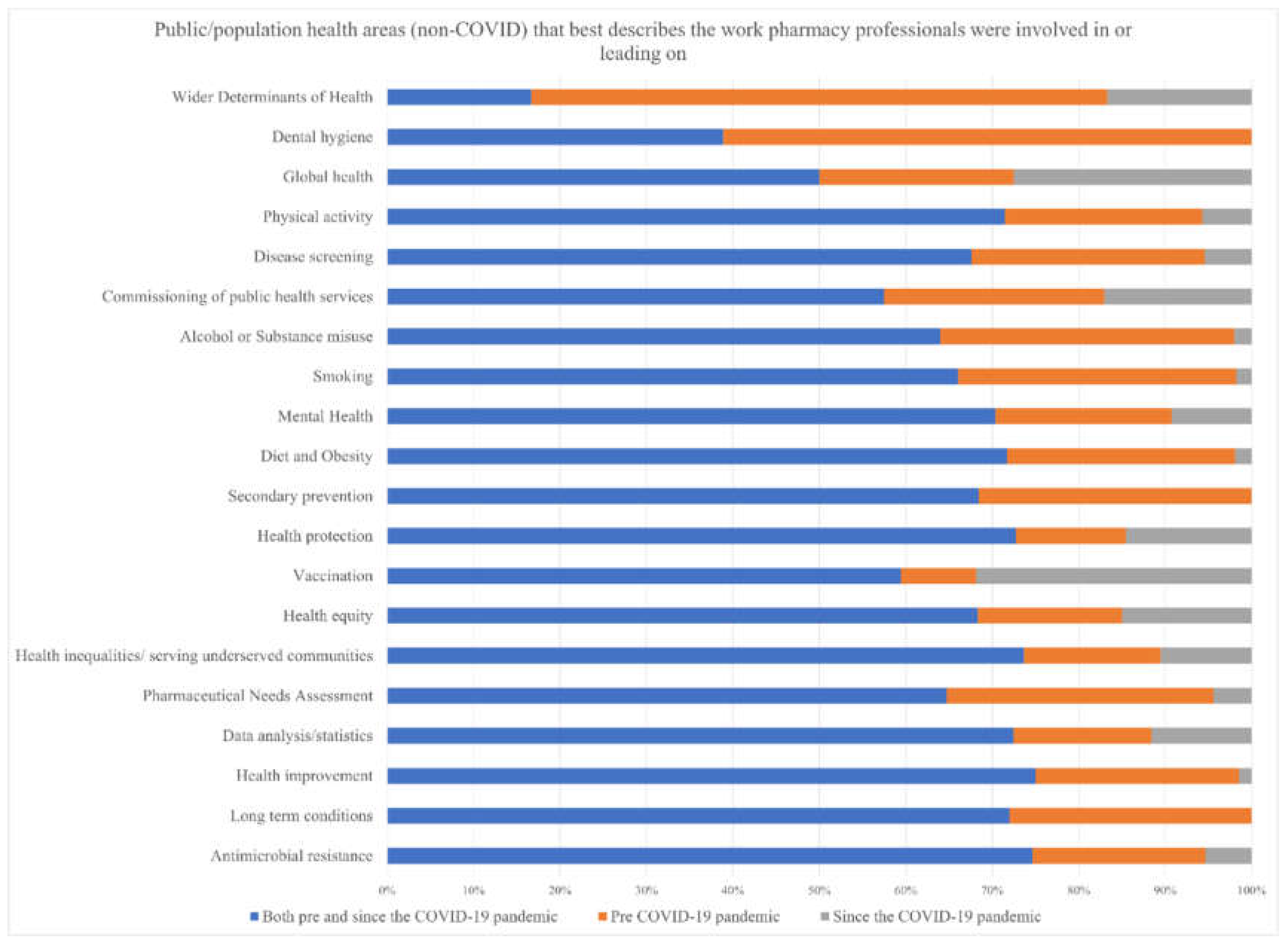

3.1.1.3. Public Health Experience

3.2. Survey of Public Health Professionals

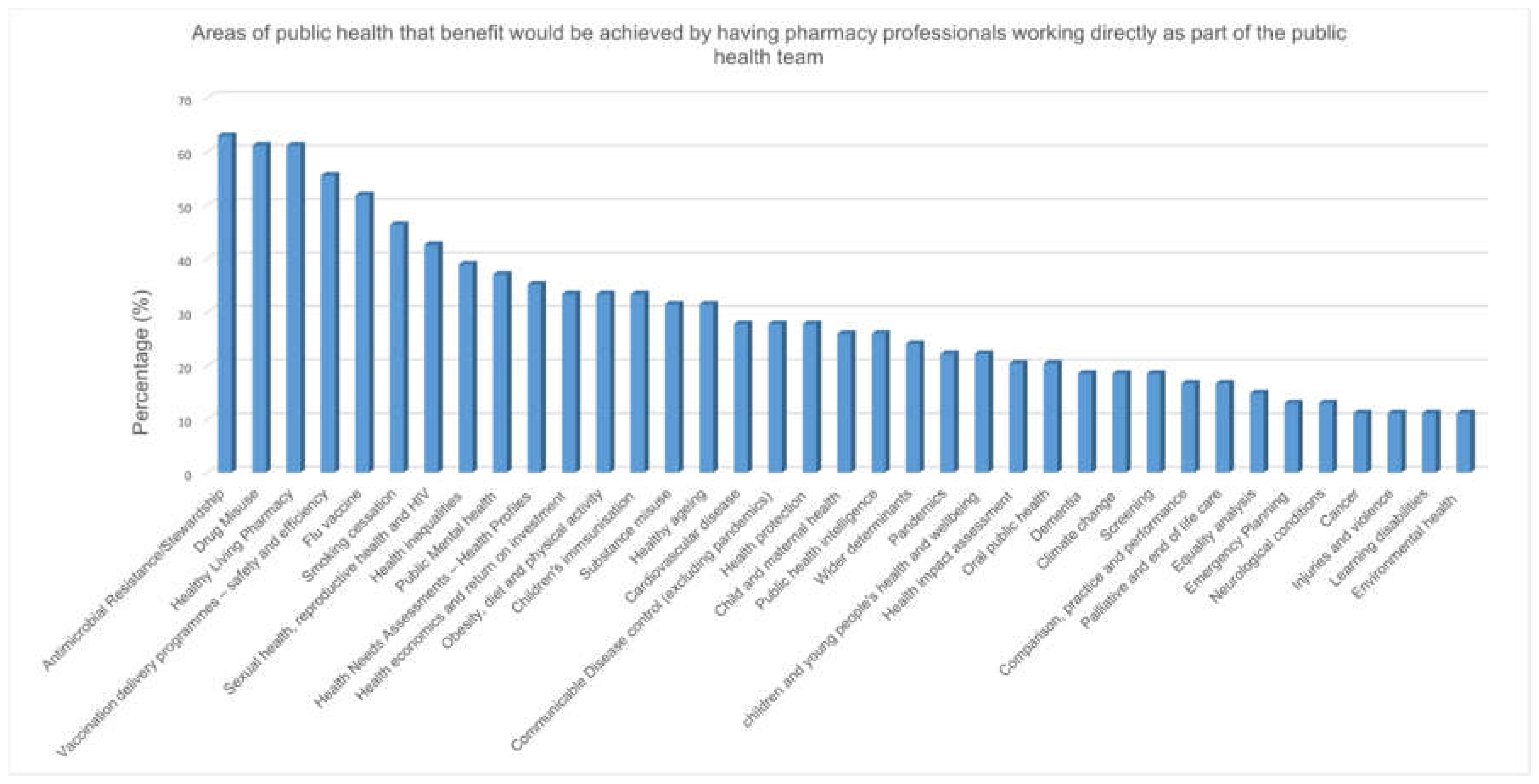

3.2.1. Benefits and Barriers to Specialist Roles for Pharmacists in Public Health

3.2.2. Call for Evidence

3.3. Workshops to Generate Recommendations

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations for Action

- Clearer regional and national leadership is required, defining standards and career pathways for pharmacy professionals in public health, with a robust competency framework and accreditation.

- Review of relevant regulations such as the Pharmaceutical Needs Assessment (PNA) regulations in UK would ensure that the emerging role of pharmacy professionals in public health is highlighted, and that data is formally collected as part of the PNA process.

- Setting priorities for public health contributions from pharmacy professionals in areas with limited pharmacy input, such as in emergency preparedness and planning, health protection, medicines surveillance and interventions, integration of primary, secondary and tertiary care, and health inequalities—the latter particularly in areas with a high population of underserved communities.

- Defining a PPH career pathway will allow pharmacy professionals to remain within the profession whilst contributing or leading on public health matters, including at strategic levels. Within undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, public health competencies can be embedded within the curricula, such as undergraduate foundation modules or public health components in clinical and prescribing courses.

- Promoting specialism in PPH, for example in the UK through the Royal Pharmaceutical Society’s consultant credentialing and/or joint recognition or registration with the General Pharmaceutical Council and Faculty of Public Health (or UKPHR) would be a strong step to validating pharmacy professionals pursuing this avenue. For pharmacy technicians and pharmacy support staff, embedding PPH within their respective training courses would highlight the importance of pharmacy involvement in this area.

- Training programme for pharmacy professionals should include options to undertake public health activities, including health policy, wider determinants of health and financial drivers of population health. Constructing an effective professional development network will provide peer support and continual workforce development.

- Promoting the sharing of good PPH practice models and increasing the dissemination and adoption of research, audits and project findings by individuals will strengthen the PPH community. For high quality research, creating funding mechanisms for PPH with in turn promote involvement and collaboration in public health spheres.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- John Coggon, What Is Public Health? (London: Faculty of Public Health, 2023. https://www.fph.org.uk/what-is-public-health/.

- Walker, R. Pharmaceutical public health: the end of pharmaceutical care? Pharm J 2000;264:340–1.

- Mulvale, G., Embrett, M. & Razavi, S.D. ‘Gearing Up’ to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC Fam Pract 17, 83 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Stokes G, Rees R, Khatwa M, Stansfield C, Burchett H, Dickson K, Brunton G, Thomas J. Public health service provision by community pharmacies: a systematic map of evidence. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=3753 (accessed 28 October 2024).

- Root G, Varney J. Pharmacy: a way forward for public health. Opportunities for action through pharmacy for public health. Public Health England: London, UK. 2017:1-53.

- Todd A, Copeland A, Husband A, Kasim A, Bambra C. The positive pharmacy care law: an area-level analysis of the relationship between community pharmacy distribution, urbanity and social deprivation in England. BMJ Open. 2014 Aug 12;4(8): e005764. [CrossRef]

- National Health Service. The NHS long term plan London NHS; 2019 https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan/ (Accessed 6 Oct 2023).

- Scottish Government. Scotland’s public health priorities. 2018 https://www.gov.scot/publications/scotlands-public-health-priorities/ (Accessed 6 Oct 2023).

- Department of Health, Northern Ireland. Making Life Better—a whole system framework for public health. 2014 https://www.health-ni.gov.uk/publications/making-life-better-strategy-and-reports (Accessed 6 Oct 2023).

- Welsh Government. A Healthier Wales: Long Term Plan for Health and Social Care (Wales). 2021 https://www.gov.wales/healthier-wales-long-term-plan-health-and-social-care (Accessed 6 Oct 2023).

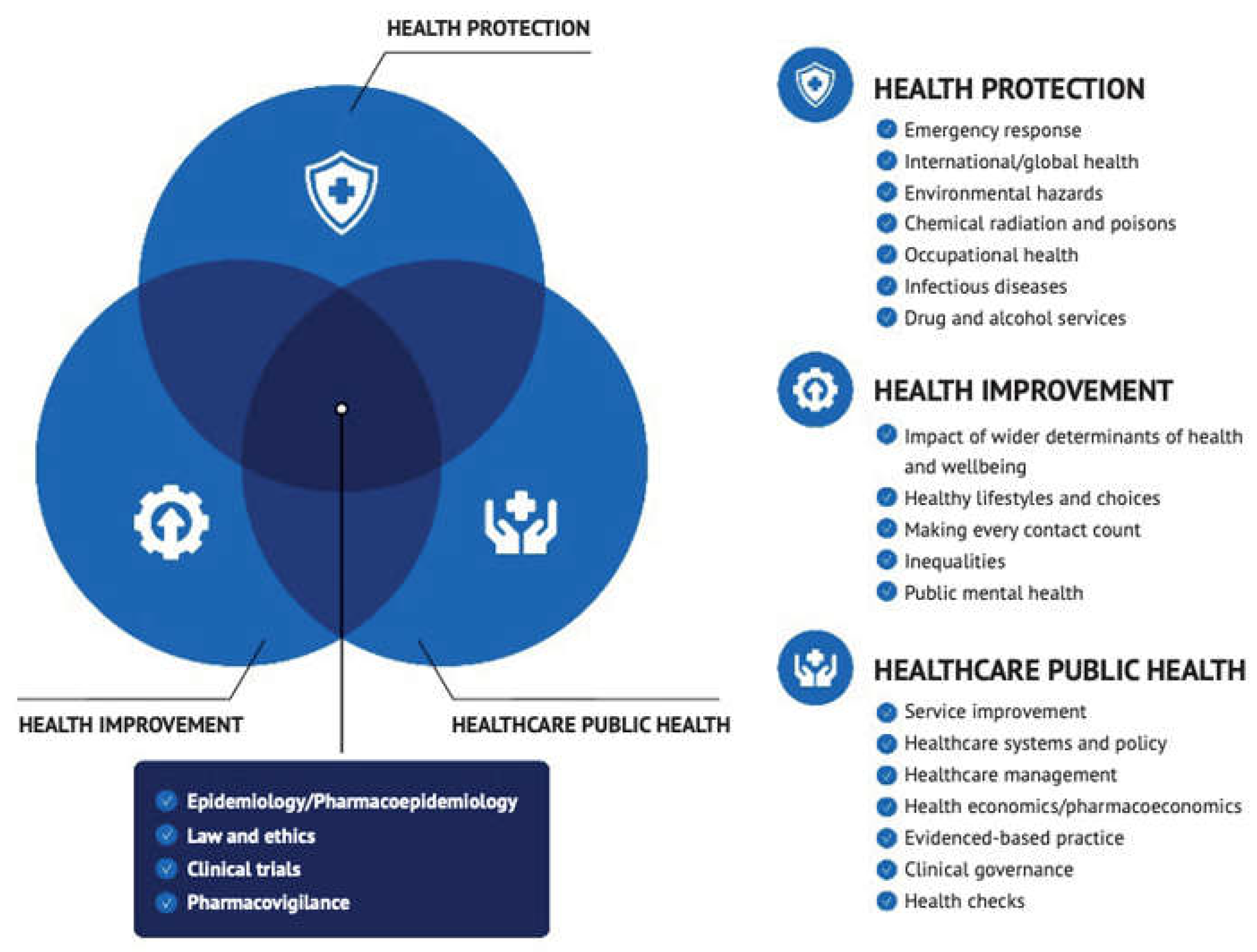

- Griffiths S, Jewell T, Donnelly P. Public health in practice: the three domains of public health. Public health. 2005 Oct 1;119(10):907-13. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO-ASPHER competency framework for the public health workforce in the European region. World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe; 2020. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/347866 (accessed 06 Oct 2024).

- Mulvale G, Embrett M, Razavi SD. ‘Gearing Up’to improve interprofessional collaboration in primary care: a systematic review and conceptual framework. BMC family practice. 2016 Dec;17(1):1-3.

- McConkey R. The Health Foundation-Technical annexes A–G: NHS workforce projections 2022. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/nhs-workforce-projections-2022 (accessed 28 October 2024).

- Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: Effects of Practice-based Interventions on Professional Practice and Healthcare Outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;3:CD000072.

- Petrelli F, Francesco T, Scuri S, Cuc NT, Grappasonni I. The pharmacist’s role in health information, vaccination and health promotion. Annali Di Igiene Medicina Preventiva E Di Comunità. 2019;31(4):309-15.

- Thomson K, Hillier-Brown F, Walton N, Bilaj M, Bambra C, Todd A. The effects of community pharmacy-delivered public health interventions on population health and health inequalities: a review of reviews. Preventive Medicine. 2019 Jul 1;124:98-109. [CrossRef]

- Mossialos E, Courtin E, Naci H, Benrimoj S, Bouvy M, Farris K, Noyce P, Sketris I. From “retailers” to health care providers: Transforming the role of community pharmacists in chronic disease management. Health Policy. 2015 May;119(5):628-39. [CrossRef]

- Garber J, Downing D. Perceptions, Policy, and Partnerships: How Pharmacists Can Be Leaders in Reducing Overprescribing. Sr Care Pharm. 2021 Mar 1;36(3):130-135.

- Maidment I, Young E, MacPhee M, Booth A, Zaman H, Breen J, Hilton A, Kelly T, Wong G. Rapid realist review of the role of community pharmacy in the public health response to COVID-19. BMJ Open. 2021 Jun 16;11(6): e050043. [CrossRef]

- Aruru M, Truong HA, Clark S. Pharmacy Emergency Preparedness and Response (PEPR): a proposed framework for expanding pharmacy professionals’ roles and contributions to emergency preparedness and response during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021 Jan;17(1):1967-1977. [CrossRef]

- Noe B, Smith A. Development of a community pharmacy disaster preparedness manual. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2013 Jul-Aug;53(4):432-7. [CrossRef]

- Anderson C, Blenkinsopp A, Armstrong M. The contribution of community pharmacy to improving the public’s health: summary report of the literature review 1990–2007.

- Strand MA, DiPietro Mager NA, Hall L, Martin SL, Sarpong DF. Pharmacy Contributions to Improved Population Health: Expanding the Public Health Roundtable. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020 Sep 24;17:E113. [CrossRef]

- Strand MA, Tellers J, Patterson A, Ross A, Palombi L. The achievement of public health services in pharmacy practice: A literature review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016 Mar-Apr;12(2):247-56. [CrossRef]

- Power A; NHS Education for Scotland Pharmacy Team. Scotland: a changing prescription for pharmacy. Educ PrimCare. 2017 Sep;28(5):255-257.

- Xyrichis A, Lowton K. What fosters or prevents interprofessional teamworking in primary and community care? A literature review. IJNS. 2008 Jan 1;45(1):140-53. [CrossRef]

- Faculty of Public Health. Functions and Standards of a Public Health System. 2021. https://www.fph.org.uk/professional-development/good-public-health-practice/ (accessed 06 October 2023).

- Roberts W, Satherley P, Starkey I, et al. The unusual suspects: unlocking the potential of the wider public health workforce [Online]. 2024. Available at: https://www.rsph.org.uk/our-work/policy/wider-public-health-workforce/unusual-suspects-unlocking-potential-wider-public-health-workforce-report.html#:~:text=%22This%20new%20RSPH%20report%20makes,healthier%20and%20more%20prosperous%20future.%22 (accessed 06 October 2023).

- Adam Todd, Diane Ashiru-Oredope, Building on the success of pharmaceutical public health: is it time to focus on health inequalities?, IJPP, 32 (5): 337–339,. [CrossRef]

- Warren, R., Young, L., Carlisle, K., Heslop, I. ., & Glass, B. (2021). REVIEW: Public health competencies for pharmacists: A scoping review. Pharm Ed, 21, p. 731–758. [CrossRef]

- Auimekhakul T, Suttajit S, Suwannaprom P. Pharmaceutical public health competencies for Thai pharmacists: A scoping review with expert consultation. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2024 Apr 22;14:100444. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Warren R, Young L, Carlisle K, Heslop I, Glass B. A systems approach to the perceptions of the integration of public health into pharmacy practice: A qualitative study. Explor Res Clin Soc Pharm. 2023 May 9;10:100279. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- D Ashiru-Oredope, T Harrison, E Wright, R Osman, C Narh, U Okereke, E Harvey, M Bennie, C Garland, A Evans, C Pyper, Barriers and facilitators to pharmacy professionals’ specialist public health roles: a mixed methods UK-wide pharmaceutical public health evidence review, International Journal of Pharmacy Practice, Volume 30, Issue Supplement_2, December 2022, Pages ii2–ii3.

- Ashiru-Oredope D, Osman R, Narh C, Okereke U, Harvey EJ, Garland C, Pyper C, Bennie M, Evans A. Public health qualifications, motivation, and experience of pharmacy professionals: exploratory cross-sectional surveys of pharmacy and public health professionals. Lancet. 2023 Nov;402 Suppl 1:S24. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender identity | |

| Female (including trans women) | 90 (70) |

| Male (including trans men) | 35 (27) |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (3) |

| Ethnic group or background | |

| White—British | 62 (48) |

| Asian or Asian British—Indian | 13 (10) |

| White—Irish | 12 (9) |

| Black or Black British—African | 11 (9) |

| White—Any other White background | 8 (6) |

| Prefer not to say | 5 (4) |

| Asian or Asian British—Any other Asian | 3 (2) |

| Asian or Asian British—Pakistani | 3 (2) |

| Mixed—Any other mixed background | 3 (2) |

| Other Ethnic Groups—Chinese | 3 (2) |

| Black or Black British—Caribbean | 2 (2) |

| Black or Black British—Any other Bla | 1 (1) |

| Mixed—White and Asian | 1 (1) |

| Not stated | 1 (1) |

| Country of work | |

| England region | 96 (75) |

| South East | 20 (21) |

| Midlands | 18 (19) |

| London | 17 (18) |

| North East and Yorkshire | 11 (11) |

| National | 9 (9) |

| East of England | 8 (8) |

| North West | 7 (7) |

| South West | 6 (6) |

| Scotland | 13 (10) |

| Northern Ireland | 9 (7) |

| Wales | 9 (7) |

| GB | 1 (0.1) |

| Total | 128 (100) |

| Themes | Number | Sample quotes |

| Limited career opportunities/ no defined career pathway | 39 (19.7%) |

No clear career pathway, very few boards have pharmacy public health posts. There is a lack of job opportunities for pharmacy professionals within public health teams themselves as there is a lack of recognition of the core knowledge and qualification that pharmacy professionals possess. There is also a lack of clarity with regards to professional management of the pharmacy professional within public health. Not a traditional role. Used to be common placed for a PH pharmacists in boards but sadly no longer the case |

| Poor professional recognition | 34 (17%) |

Not always seen as public health champions the profession is often overlooked as a solution, The barriers for pharmacist to be involved in public and population health are: 1. lack of awareness in public health of what pharmacists can bring to the table. 2. lack of awareness in the pharmacy community of the role that pharmacists can play in public health at a policy and strategy level. I suspect many pharmacists will not be aware of needs assessments other than that for community pharmacies. There appears to not be a good understanding from other healthcare professionals and the general public of the impact pharmacy professionals could have given the opportunity Pharmacist are not seeing as a profession that can contribute to public health |

|

Limited resources (time or financial) |

32 (16%) |

capacity- pharmacists workload, less protected time for research/QI, under-resourced profession in multiple sectors Busy on daily task. No time to put aside to capture data to understand impact of our daily work on public health. No time to design audits. Prohibitive costs associated with studying a Master’s course and lack of sponsorships for experienced healthcare professionals from high income countries. capacity, resources and whether it is seen as economically viable |

| Lack of training and support | 30 (15%) |

lack of pharmacy specific formal training that can easily be accessed. to progress in public health as a pharmacist means moving away from being a pharmacist to become a public health specialist/consultant. Pharmacy technicians for example are only required to ‘know’ about public health issues and not to be able to demonstrate how they can tackle them. |

| Inadequate Public Health knowledge |

21 (11%) |

Lack of understanding of the difference between individual and population health and how inadvertent actions to do better for every individual may actually widen inequality. No undergraduate training in epidemiology and/or data science. Pharmacy degree doesn’t set people up very well for research. There’s too much focus on completing clinical diploma post-reg for people to consider a career in PH I feel that a lot of pharmacists don’t consider aspects of what they are already doing as public health. Having this broader understanding may change the way they think about delivery of certain services and care. Public health not a core part of the pharmacy degree (that I am aware of) Training on Health promotion and changing health behaviours would be helpful for all pharmacists. There are vast opportunities for pharmacy professionals to be involved in public health but the initial education of neither profession enables a natural progression towards that. |

| Organisational and structural barriers | 19 (10%) |

workload and staffing structures & wider corporate agenda (large multiples) for Community pharmacy For popoulation health lack of understanding within pharmacy senior leadership in practice settings, lack of education and training in this area (prior experience and access to), no pharmacy network Generally work gets focused on medication management leave less scope for work on wider determinants and other aspects of healthcare public health like screening, Health Impact assessment, health promotion programmes though options are increasing.More likely to have a public health component to work rather than have it as a primary focus |

| Not capitalizing on available opportunities | 12 (6%) |

Just about not being aware of what the role entails and having experience in publishing research and drafting proposals/business cases. Not knowing the opportunities available Pharmacy professionals advocating for traditional roles |

| Poor representation in public health domains | 11 (6%) |

Pharmacists are not actively targeted for our experiences to work for PH. There aren’t many pharmacists directly employed by LAs—I don’t know why this is. Provide a service then take it away and see what happens—back to the “proving one’s worth” in a political organisation maybe? In some arenas there are perceptions that all avenues are covered. It’s only when pharmacists/technicians become involved that new solutions or alternative ways of working are exposed. |

| Themes | Number | • Sample quotes |

| A range of Public Health areas pharmacy professionals can get involved in | 44 |

There are many opportunities for community pharmacy professionals to be involved in public health interventions depending on capacity, training and commissioning of services e.g., smoking cessation, sexual health, vaccination, substance misuse services, infection prevention and testing/treating and contributing to pathways for overweight and obesity. There are also opportunities for pharmacists employed by health boards to be involved in population health e.g., prescribing /medicines management initiatives. The All Wales Therapeutics and Toxicology Centre has various working groups in which pharmacists can be involved in strategic medicines management/pharmaceutical public health which in some instances links to other sources of data to provide a broader perspective . Infectious disease screening and treatment in addition/association to the work commonly done by nurses, e.g., TB. Hepatitis CBRNE and disaster preparedness. Pharmacists long overlooked. Their expertise lends itself to this. Mass vaccination programs Work with diseases of global importance, e.g., haemorrhagic fevers Polypharmacy and de-prescribing • Some local authorities are lacking clinically trained staff. I have found that pharmaceutical expertise embedded within and available to support the local authority public health, and wider LA teams is crucial to enable the appropriate/correct collaboration which is needed for commissioning/transformational change/medicines optimisation. Without this, going forward our community pharmacies may not be considered locally or become recognised as place-based assets to reach their full potential to improve health prevention and chronic disease management as part of the NHS Long Term Plan. • Significant need and opportunity for pharmaceutical public health skills to be deployed at system and place level to support commissioning of medicines and pharmacy services |

| Qualification, knowledge and skills | 26 | • Pharmacy technicians are highly trained, knowledgeable and experienced in providing direct patient care, liaising professionally with other healthcare professionals and are experts in medicines supply and storage • A lot of what Pharmacy professionals do in primary care is on a population basis and has an immediate link with public health. For example from producing a local guideline to seeing its implementation in practice affects the health of our population. • We have a unique perspective on health related to medication. This can be valuable in many different areas • Based at the heart of local communities community pharmacy professionals are most likely to see the patient first in respect of public health issues especially when related to self care and yet they are not always the first choice for commissioners. The sector cannot play its role in integrated care if is not included at the right tables. Seats at the right tables need to be made available to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians (as opposed to the contractor) so that both professions can maximise their usefulness in this arena. |

| Strategic position in the community | 18 | • Very important area—pharmacies are embedded in the heart of our communities, see our population more than any other health professional • Pharmacy professionals is widely accessible by the general public and key to deliver any public health messages • Community pharmacists in particular have an opportunity to engage with the public on PH issues. General Practice and hospital pharmacists also have opportunities to engage with patients during discussion of medication issues. • I believe pharmacists are well placed to be involved in public / population health. They have insights into their local areas and communities. They approach health with a hollistic approach whilst still maintaining the traditional clinical role. Thay are more accessible than most other health care professionals and have greater insight into reasoning for lifestyle choices and behaviours, such as addiction, obesity, etc. • As accessible healthcare professionals, we have increasing opportunities to identify risk and take a proactive approach to improving the health of populations and individuals. • Pharmacists/ technicians are easily accessible on the high street without an appointment to provide advice/ support/ signposting. Lots of opportunity for brief advice in both community and also primary care pharmacy when undertaking medication optimisation/ medication reviews. |

| Recent changing health landscape (health policy e.g., long-term plan) | 4 | • The long term plan has increased the opportunity available for pharmacy professionals. • There is large overlap between public/ population health and pharmacy practice and pharmacists I think have a particular role in pharmaceutical public health. |

| COVID | 3 | • My colleagues were directly involved with the covid vaccinations • Most definitely- involvement in recent Covid vaccination for example. • Pharmacists played a central role in the excellent vaccine rollout in the UK, manufacturing of alcohol rubs, in providing advice on the administration and sourcing of medication to be used in COVID19. We are analytical, excellent communicators, efficient and brilliant decision makers. There are many opportunities for us to demonstrate this at a global, regional and national level. |

| Good public perception | 2 | • The public and healthcare professionals trust our judgement and knowledge, so now is the perfect time to showcase our skills in public/ population health. • trusted professional, expert in medicines, access to patients, |

| Category | Subcategory | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Job Role of Respondent n=54 | Public health consultant | 10 (18.5%) |

| Public health Registrar ST1-3 | 7 (13.0%) | |

| Public health Registrar ST4-5 | 6 (11.1%) | |

| Public health practitioner | 5 (9.3%) | |

| Director of Public health | 5 (9.3%) | |

| Others | 4 (7.4%) | |

| Strategist | 2 (3.4%) | |

| Public Health pharmacist | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Principal public health practitioner | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Public health academic | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Allied health practitioner | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Area of Specialty n=51 | General | 13 (24.1%) |

| Health Improvement | 11 (20.4%) | |

| Health Protection | 10 (18.5%) | |

| Healthcare Public Health | 10 (18.5%) | |

| Commission | 3 (5.6%) | |

| Screening | 2 (3.7%) | |

| Sexual Health | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Substance abuse | 1 (1.9%) | |

| Gender n=54 | Female | 36 (66.7%) |

| Male | 16 (29.6%) | |

| Prefer not to say | 2 (3.7%) | |

| Location of practice (Country) n=54 | England | 32(59.3%) |

| Scotland | 15(27.8%) | |

| Wales | 7(13.0%) | |

| Location of practice (Region) n=22 | Midlands | 7 (22.0%) |

| South West | 6 (19.0%) | |

| South East | 5 (16.0%) | |

| North East and Yorkshire | 4 (13.0%) | |

| North West | 4 (13.0%) | |

| London | 4 (13.0%) | |

| National | 2(6.0%) | |

| East of England | 0 | |

| Description of main area(s) of work n=31 | Local Authority council | 14 (43.8) |

| Public Health England—regional/ local | 7 (21.9%) | |

| Public Health England—national | 2 (6.2%) | |

| Acute national health service (NHS) trust | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Health boards or trusts | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) | 1 (3.1%) | |

| University | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Professional body– regional/ local | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Military | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Mental Health trust | 1 (3.1%) | |

| Primary care Network | 1 (3.1%) |

| Benefit of having pharmacy professional specialise in public health n=52 | Very Beneficial | Beneficial | Somewhat Beneficial |

| 26(50.0) | 19(26.5) | 7(13.5) | |

| Barriers for pharmacy professional to get involved in population health n=50 | Yes | No | Not sure |

| 30(60.0) | 13(26.0) | 1(2.0) | |

| Organization provide placement to funded pharmacy professional for fellowship in public health n=32 | Yes | No | Maybe |

| 10(21.3) | 6(12.8) | 16(34.0) | |

| Local Authority inclusion of medicine service as part of MOU with CCG n=19 | Yes | No | Not sure |

| 1(3.3) | 4(13.3) | 14(46.7) |

| Themes | Number | Sample quotes |

| Organisational and structural barriers | 13 |

“time, staff turnover, recovery from COVID pandemic” “Reluctance to change status quo from senior management and policy down to front-line. Fear of additional workloads in already stretched services (although social prescription and signposting goal would be to reduce reliance), lack of undertanding (not enough data locally or nationally) on the long-term benefits of an increased focus and increase in funding towards social prescription.” “It seems form my experience of working with pharmacies that they are quite pressured for time and there is a high turn over of counter staff sometime as well as a turn over of commercial owners” gaining of agreement for pharmacists to be willing to do more public health focused work as it could be seem as detracting from their ‘core business’. |

| Lack of training and support | 6 |

There will be barriers including limitations to what pharmacists are able to do in their working day, what training they would need to undertake public health work, To be blunt I have been working in XXXXXX for x years and nobody ever suggested I take formal training in this area. People work in silos and as long as you are ticking the boxes, they leave you alone. I feel any senior professional joining a public health organisation without public health training needs to obtain it, fast! |

| Limited career opportunities/ no defined career pathway | 9 |

, not many role models or possibly job opportunities, may need to carve out a niche for themselves potentially difficult to maintain professional practice whilst working in PH there is no defined formal route into public health. Some pharmacists can go via Specialty Registrar, and others have used the Defined specialist route (recently refined). The public health role and opportunity for pharmacists need to be integrated into Learning and Academic organisations to get early buy in There is a lack of job opportunities for pharmacy professionals within public health teams themselves as there is a lack of recognition of the core knowledge and qualification that pharmacy professionals possess. Pharmacy professionals may also lack clarity/confidence in moving to a new area of work especially if they feel that they will need to undertake a new qualification to enable them to work within public health. There is also a lack of clarity with regards to professional management of the pharmacy professional within public health. Not a traditional role. Used to be common placed for a PH pharmacists in boards but sadly no longer the case |

| Poor professional recognition | 10 | |

| Inadequate PH knowledge | 2 |

In general our pharmacy colleagues are not PH trained. They are therefore clearly expert in medicines issues, but don’t have wider skills in population health approaches and epidemiology. Collaborative working with PH specialists and others overcomes this to a large extent, but some training in PH for at least some of our pharmacists would be helpful. Not covered extensively at undergraduate level. Role of pharmacists in public health very variable and topic specific. Pharmaceutical public health not seem by PH fraternity or professional body as a discipline. No formal training to skill pharmacists up in this area broadly. Community pharmacy contract not remunerated for this work |

| Limited resources (time and/or financial) | 11 |

Cant think of any specific barriers although availability of pharmacists in the SW is already a challenge and exacerbating that would be a concern capacity, resources and whether it is seen as economically viable Unlikely to be a full time rule so hard to find match an interested person to a small number of hours e.g., 1 day a week. Entry level of public health professional does not support pharmacy pay grades |

| Not capitalising on available opportunities | 4 |

The importance of public health implications of medicines largely unexplored Expectations around what can be achieved with medicines are often limited to cost savings in commissioning. Wider work on reducing medication, working with community teams to ensure medication cocktails are well suited to patients will be more important as more co-morbidities in population. This work isn’t generally considered public health but it is- making sure system works together is very important. |

| Poor representation in PH domains | 3 |

Lack of understanding of wider benefits to self, profession, community and other HC professionals I think we don’t always understand each other’s areas of work and the ‘business’ side of pharmacy means certain work takes preference , like primary care. |

| Themes | Number of recommendations per theme | Examples of individual recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Public Health Skills and Training: Define PPH career pathway to allow pharmacy professionals to remain within the profession but contribute/lead on PH |

32 | Develop a career development pathway that does not require pharmacy professionals to work outside the speciality to be recognised as qualified public health professionals. |

| National Strategic Approach: Define national standards and career pathway for pharmacy professionals in Public Health (PH) |

31 | Define national standards for population health knowledge to support consistency across all localities of Great Britain and support capability for roll out of national services. |

| Other Commissioning: All ICSs should have PPH representation |

13 | Increase involvement of pharmacy in the commissioning process. |

| Expanding Service Delivery beyond Community Pharmacy: Integrate Pharmaceutical PH (PPH) teams within a variety of care sectors | 10 | Bring elements of public health into pharmacist practice. |

| Integration of Pharmacy to Better Support PH Protection & Improvement Goals | 3 | Involve pharmacy in leading public health services, e.g., National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training practitioners. |

| Mitigating Health Inequalities: Involve PPH as part of Integrated Care Systems (ICS) health inequalities agenda |

3 | Each ICS health inequalities agenda to produce a review of what pharmacy can do to make a difference. |

| Embedding Optimisation of Medicines at a Population Health Level: Include PPH within medicines optimisation at a population level |

1 | Improve the integration / joint working between ICS / LA / PHE to address use of medicines for population health management—as currently addressed at individual sector level but not at strategic level. |

| Emergency Preparedness, Resilience and Response | 1 | Learn from the COVID-19 pandemic experience, particularly regarding the role of specialist pharmacy services and specialist pharmacists working across PHE, NHSEI and CCG’s and how they should be included as part of EPRR future planning processes. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).