Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

05 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. RNA-Seq Data Retrieval from Macrophages Infected with Leishmania Major

2.2. Bioinformatic Identification of lncRNAs and Gene Expression Analysis

2.3. The Cis-Target Gene Identification and Functional Enrichment Analysis

2.4. PPI Network Construction and Hub Gene Identification

3. Results

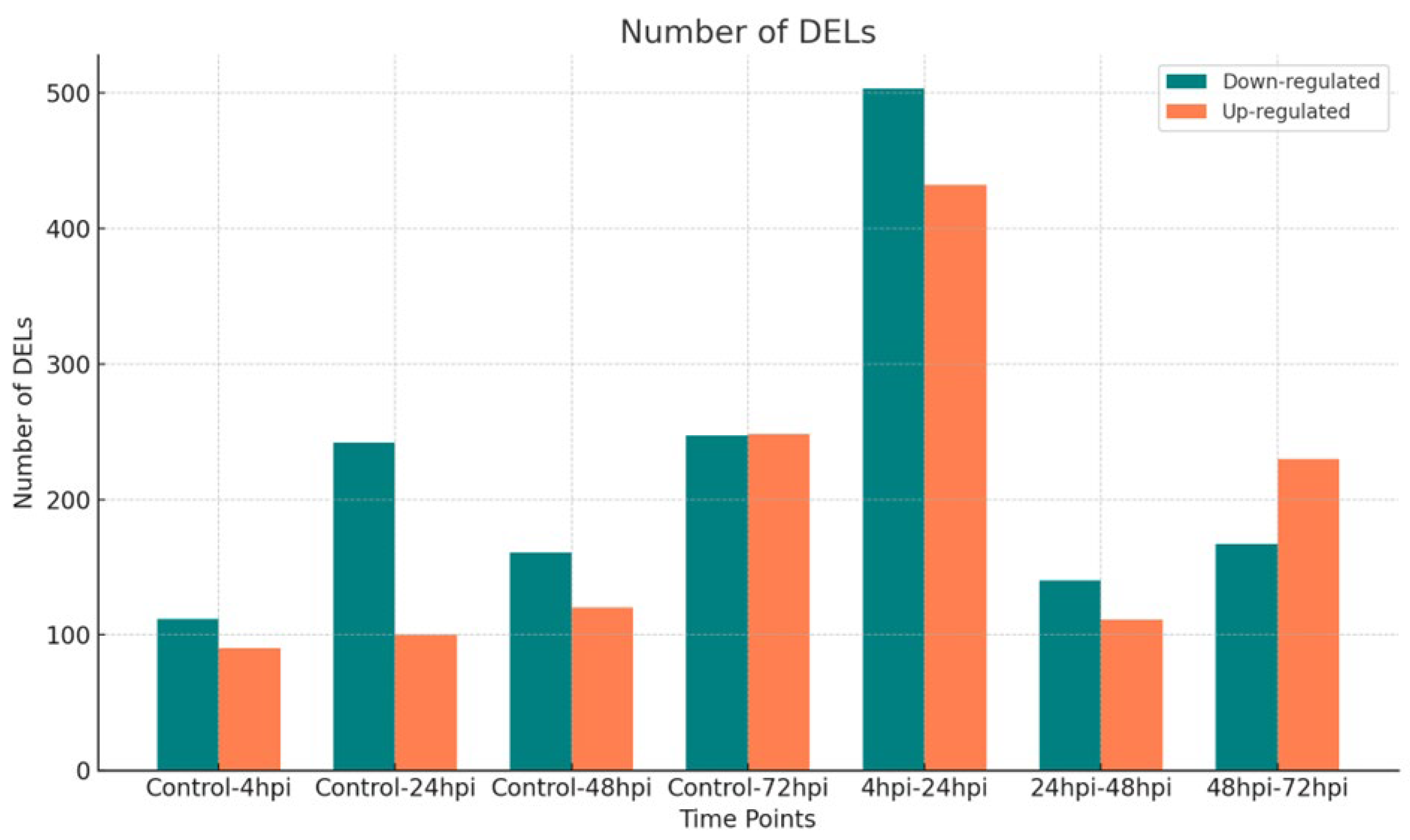

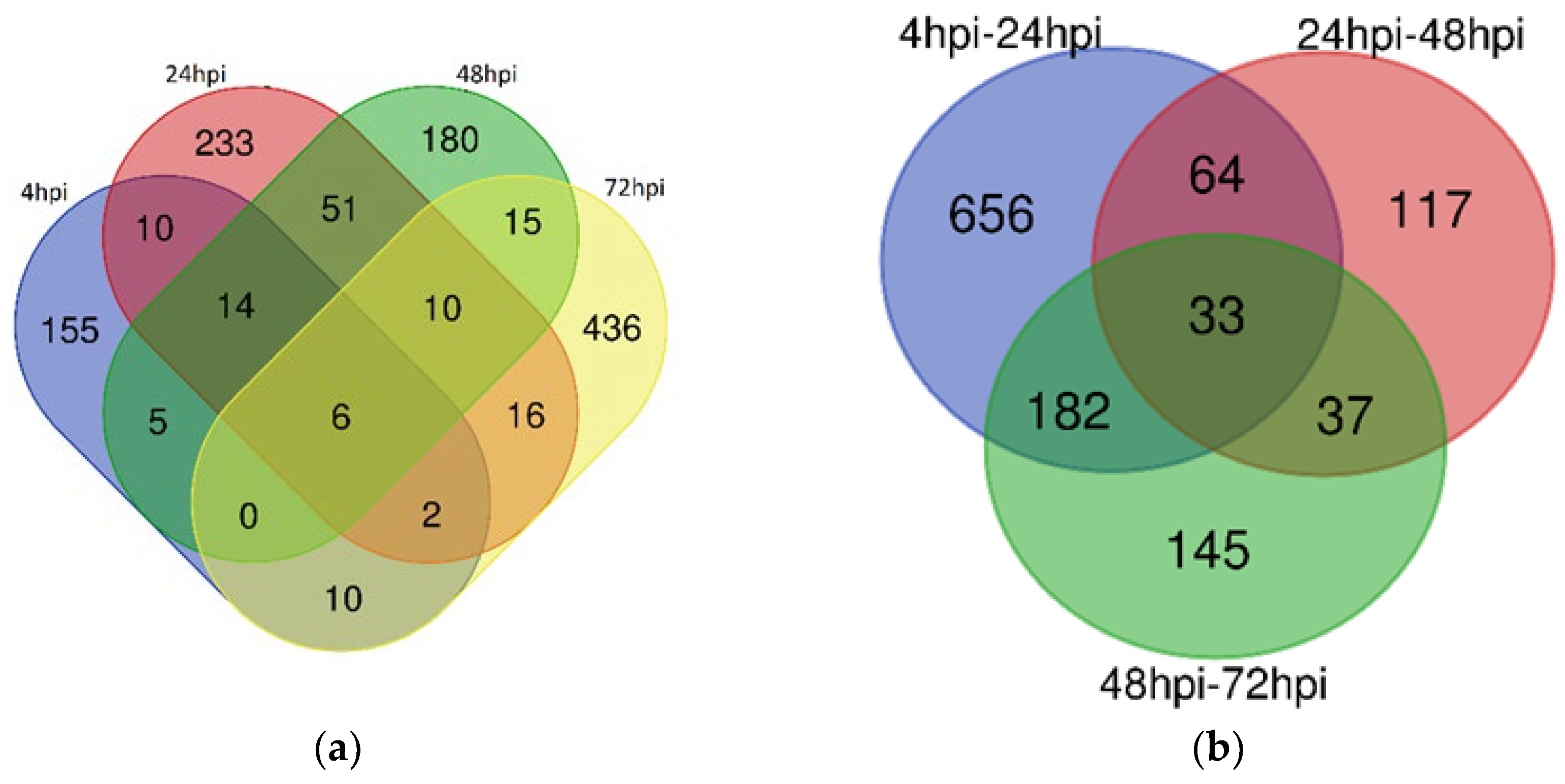

3.1. Differentially Expressed lncRNAs Between Time Point Comparisons in Human Macrophages

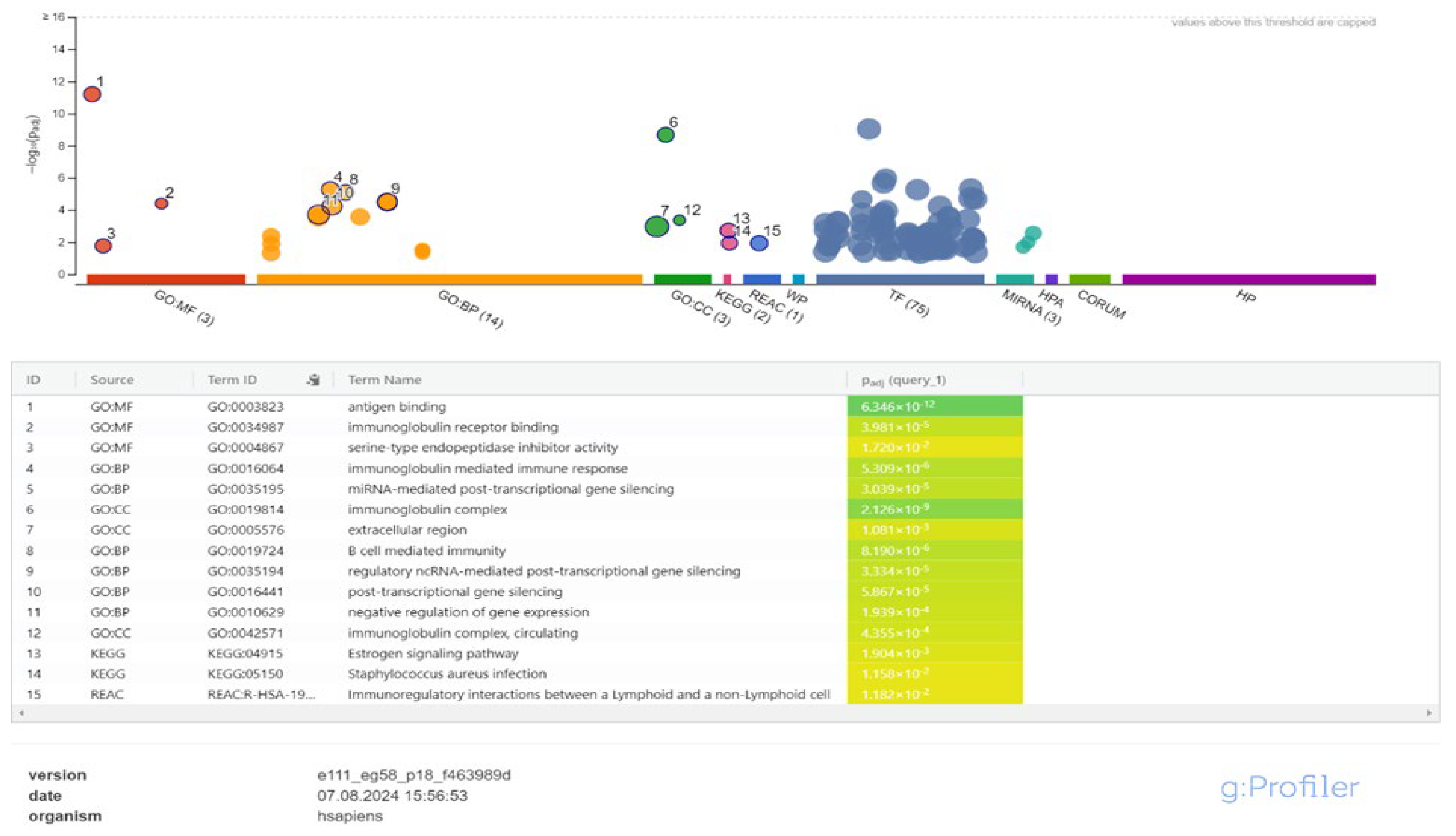

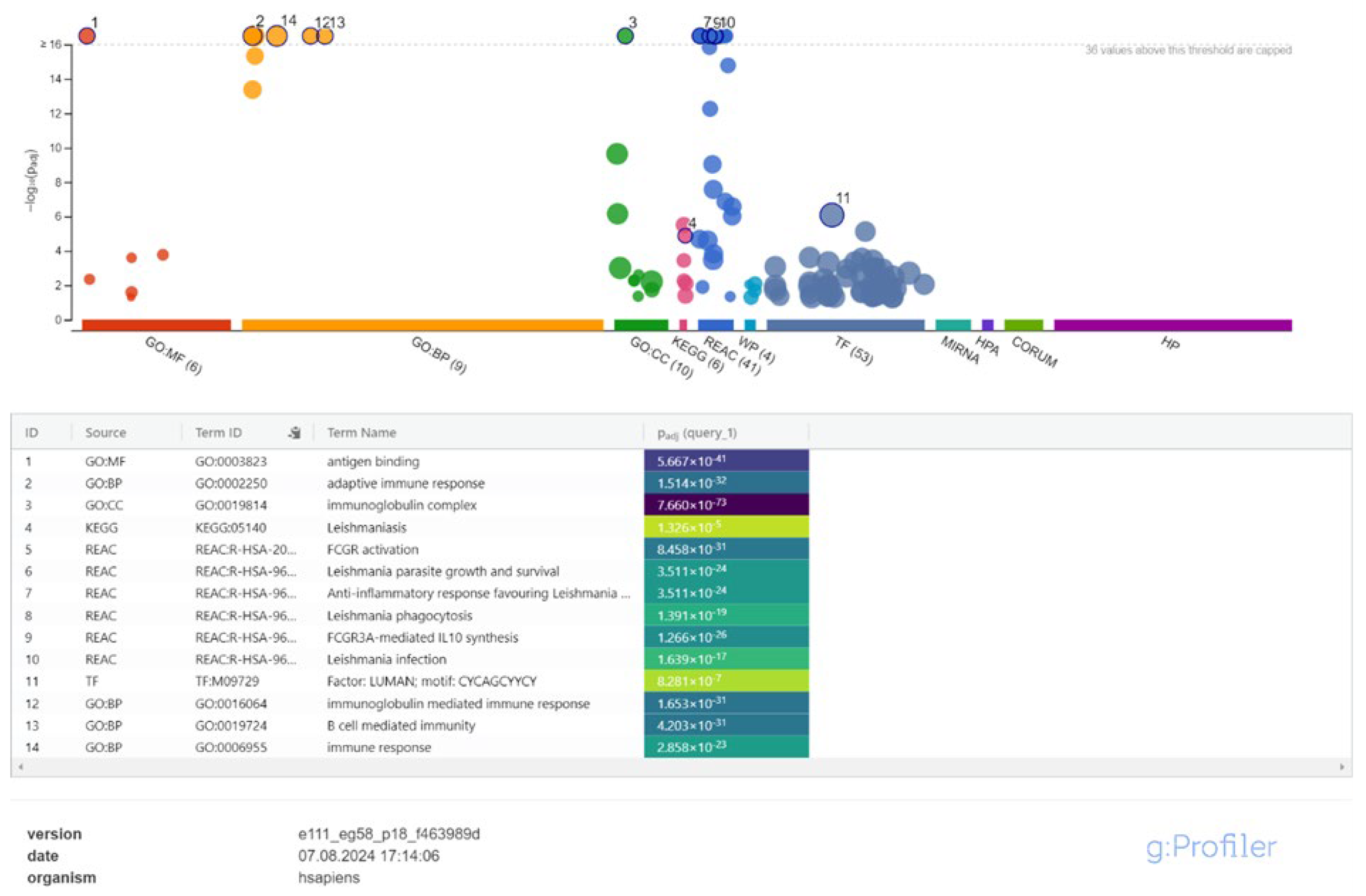

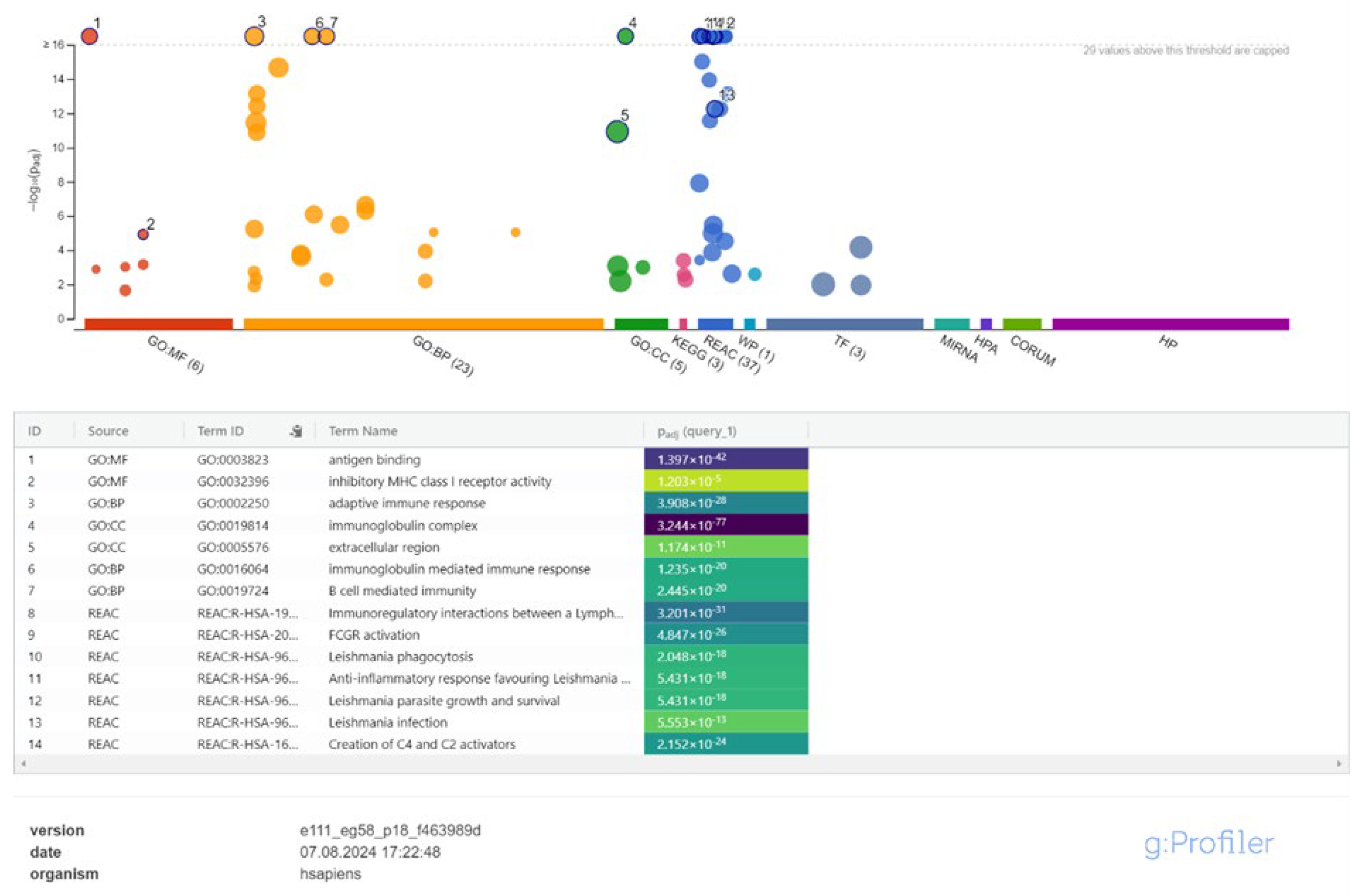

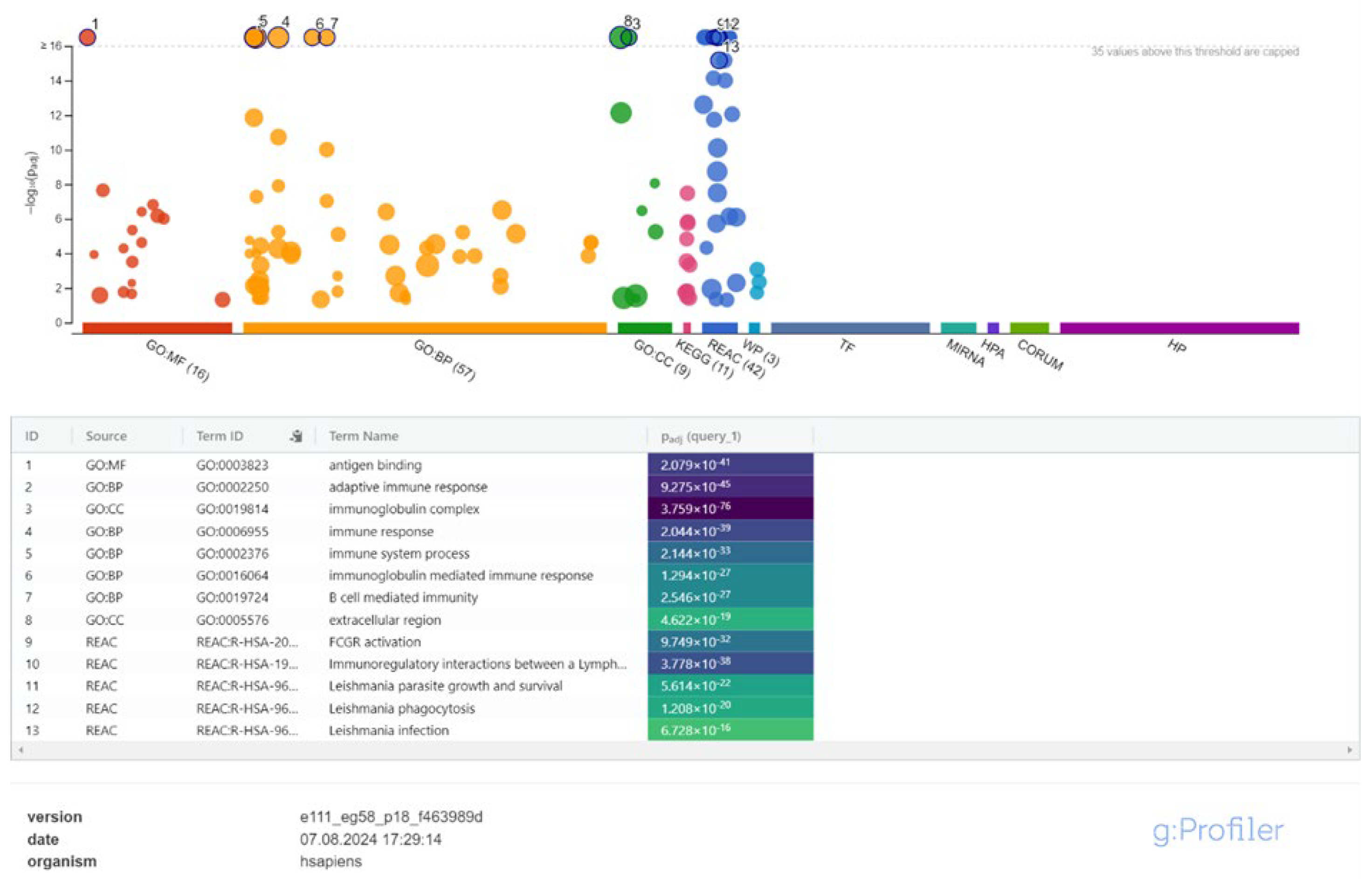

3.2. Cis-Target Genes of DElncRNAs and Functional Enrichment Analysis

3.3. Temporal Dynamics of lncRNA Expression and Immune Response

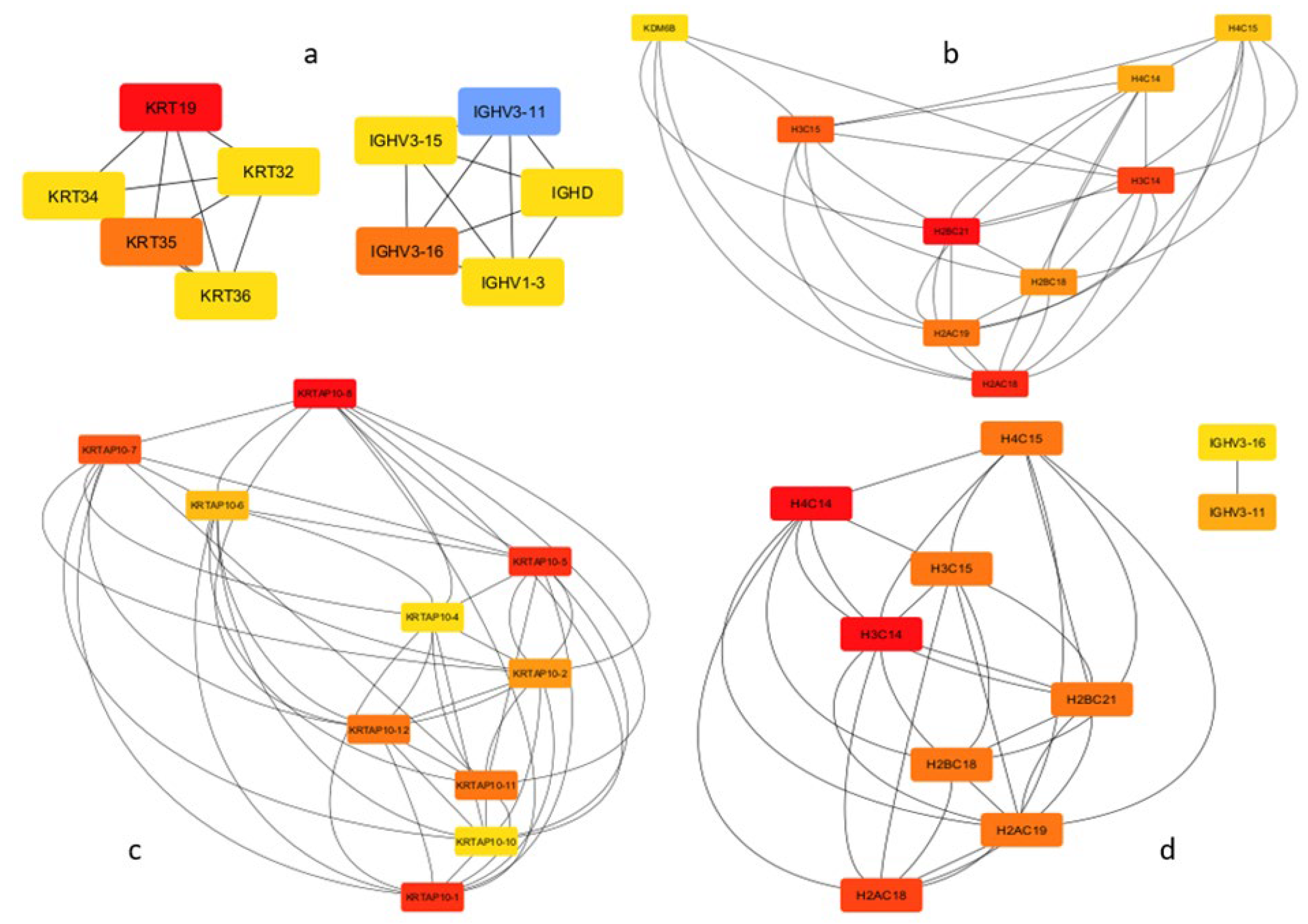

3.4. Hub Gene Identification

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaye, P.; Scott, P. Leishmaniasis: Complexity at the Host-Pathogen Interface. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 9, 604–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sacks, D.; Sher, A. Evasion of Innate Immunity by Parasitic Protozoa. Nat. Immunol. 2002, 3, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ovalle-Bracho, C.; Franco-Muñoz, C.; Londoño-Barbosa, D.; Restrepo-Montoya, D.; Clavijo-Ramírez, C. Changes in Macrophage Gene Expression Associated with Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis Infection. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0128934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Uzonna, J.E. The Early Interaction of Leishmania with Macrophages and Dendritic Cells and Its Influence on the Host Immune Response. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.X.; Rastetter, R.H.; Wilhelm, D. Non-Coding RNAs: An Introduction. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2016, 886, 13–32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Deng, W.; Zhu, X.; Skogerbø, G.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, Z.; Wang, Y.; He, H.; Cai, L.; Sun, H.; Liu, C.; et al. Organization of the Caenorhabditis elegans Small Non-Coding Transcriptome: Genomic Features, Biogenesis, and Expression. Genome Res. 2006, 16, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, V.; Aceto, S.; Musacchia, F.; Colonna, V.; Robinson, M.; Benes, V.; Cicotti, G.; Bongiorno, G.; Gradoni, L.; Volf, P.; et al. De Novo Assembly and Sex-Specific Transcriptome Profiling in the Sand Fly Phlebotomus perniciosus (Diptera, Phlebotominae), a Major Old World Vector of Leishmania infantum. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponting, C.P.; Oliver, P.L.; Reik, W. Evolution and Functions of Long Noncoding RNAs. Cell 2009, 136, 629–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Paulson, A.; Li, H.; Piekos, S.; He, X.; Li, L.; Zhong, X.B. Developmental Programming of Long Non-Coding RNAs during Postnatal Liver Maturation in Mice. PLoS One 2014, 9, e114917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angrand, P.O.; Vennin, C.; Le Bourhis, X.; Adriaenssens, E. The Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs in Genome Formatting and Expression. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imamura, K.; Akimitsu, N. Long Non-Coding RNAs Involved in Immune Responses. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J. The Functional Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs and Epigenetics. Biol. Proced. 2014, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, J.C.R.; Gonçalves, A.N.A.; Floeter-Winter, L.M.; Nakaya, H.I.; Muxel, S.M. Comparative Transcriptomic Analysis of Long Noncoding RNAs in Leishmania-Infected Human Macrophages. Front. Genet. 2023, 13, 1051568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Dillon, L.A.; Belew, A.T.; Bravo, H.C.; Mosser, D.M.; El-Sayed, N.M. Dual Transcriptome Profiling of Leishmania-Infected Human Macrophages Reveals Distinct Reprogramming Signatures. mBio 2016, 7, e00027–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, S. A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Kim, J.S.; Lee, K.T.; Bahn, Y.S. Deciphering the Regulatory Mechanisms of the cAMP/Protein Kinase A Pathway and Their Roles in the Pathogenicity of Candida auris. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0215223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, N.L.; Pimentel, H.; Melsted, P.; Pachter, L. Near-Optimal Probabilistic RNA-Seq Quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. edgeR: A Bioconductor Package for Differential Expression Analysis of Digital Gene Expression Data. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 139–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, S.P.; Nettleton, D.; McCarthy, D.J.; Smyth, G.K. Detecting Differential Expression in RNA-Sequence Data Using Quasi-Likelihood with Shrunken Dispersion Estimates. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2012, 11, 1544–6115.1826. [Google Scholar]

- Szklarczyk, D.; Franceschini, A.; Wyder, S.; Forslund, K.; Heller, D.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Roth, A.; Santos, A.; Tsafou, K.P.; et al. STRING v10: Protein-Protein Interaction Networks, Integrated over the Tree of Life. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, D447–D452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, P.; Markiel, A.; Ozier, O.; Baliga, N.S.; Wang, J.T.; Ramage, D.; Amin, N.; Schwikowski, B.; Ideker, T. Cytoscape: A Software Environment for Integrated Models of Biomolecular Interaction Networks. Genome Res. 2003, 13, 2498–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, O.; Akira, S. Pattern Recognition Receptors and Inflammation. Cell 2010, 140, 805–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimmerjahn, F.; Ravetch, J.V. Fcgamma Receptors as Regulators of Immune Responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 34–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, H.W.; Berman, J.D.; Davies, C.R.; Saravia, N.G. Advances in Leishmaniasis. Lancet 2005, 366, 1561–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, T.H.; Tsai, K.W.; Wu, Y.J.; Liao, M.T.; Lu, K.C.; Hu, W.C. The Framework for Human Host Immune Responses to Four Types of Parasitic Infections and Relevant Key JAK/STAT Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 13310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, A.T.; Heaton, N.S. The Impact of Estrogens and Their Receptors on Immunity and Inflammation during Infection. Cancers 2022, 14, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oghumu, S.; Lezama-Dávila, C.M.; Isaac-Márquez, A.P.; Satoskar, A.R. Role of Chemokines in Regulation of Immunity against Leishmaniasis. Exp. Parasitol. 2010, 126, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, F.F.; Costa-Silva, M.F.; Pereira, A.A.S.; Rêgo, F.D.; Pereira, V.H.S.; de Souza, J.P.; Fernandes, L.O.B.; Martins-Filho, O.A.; Gontijo, C.M.F.; Peruhype-Magalhães, V.; et al. Chemokines in Leishmaniasis: Map of Cell Movements Highlights the Landscape of Infection and Pathogenesis. Cytokine 2021, 147, 155339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, N.E.; Chang, H.K.; Wilson, M.E. Novel Program of Macrophage Gene Expression Induced by Phagocytosis of Leishmania chagasi. Infect. Immun. 2004, 72, 2111–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, S.P.; Doyen, N.; Mishra, G.C.; Saha, B.; Chandel, H.S. TLR9-Deficiency Reduces TLR1, TLR2 and TLR3 Expressions in Leishmania major-Infected Macrophages. Exp. Parasitol. 2015, 154, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buates, S.; Matlashewski, G. General Suppression of Macrophage Gene Expression during Leishmania donovani Infection. J. Immunol. 2001, 166, 3416–3422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, L.A.; Okrah, K.; Hughitt, V.K.; Suresh, R.; Li, Y.; Fernandes, M.C.; Belew, A.T.; Corrada Bravo, H.; Mosser, D.M.; El-Sayed, N.M. Transcriptomic Profiling of Gene Expression and RNA Processing during Leishmania major Differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 6799–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, M.C.; Dillon, L.A.; Belew, A.T.; Bravo, H.C.; Mosser, D.M.; El-Sayed, N.M. Dual Transcriptome Profiling of Leishmania-Infected Human Macrophages Reveals Distinct Reprogramming Signatures. mBio 2016, 7, e00027–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dutta, M.; Qamar, T.; Kushavah, U.; Siddiqi, M.I.; Kar, S. Exploring Host Epigenetic Enzymes as Targeted Therapies for Visceral Leishmaniasis: In Silico Design and In Vitro Efficacy of KDM6B and ASH1L Inhibitors. Mol. Divers. 2024, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafarzadeh, A.; Nair, A.; Jafarzadeh, S.; Nemati, M.; Sharifi, I.; Saha, B. Immunological Role of Keratinocytes in Leishmaniasis. Parasite Immunol. 2021, 43, e12870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scorza, B.M.; Wacker, M.A.; Messingham, K.; Kim, P.; Klingelhutz, A.; Fairley, J.; Wilson, M.E. Differential Activation of Human Keratinocytes by Leishmania Species Causing Localized or Disseminated Disease. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 2149–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Time Interval | lnc-CMPK2-2 | lnc-TMEM121-26 |

|---|---|---|

| 0hpi - 4hpi | 2.71 | -2.48 |

| 4hpi - 24hpi | 3.61 | 5.38 |

| 24hpi - 48hpi | 2.36 | -3.51 |

| 48hpi - 72hpi | -4.10 | -3.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).