1. Introduction

White oak (

Quercus alba L.) is a keystone species in the oak-dominated forests of the eastern United States, with its significant ecological and economic value [

1]. This long-lived, slow-growing species is not just important for its high-quality timber, but also for its contribution to biodiversity by providing habitat and food for a diverse range of wildlife species. However, in recent decades, white oaks in the eastern United States are experiencing increased mortality, which is evident across much of its natural range [

2,

3]. This decline is associated with a variety of biotic and abiotic factors, including stand density and soil properties, which may significantly influence tree growth, survival, and mortality.

Stand density, which reflects the number of trees per unit area or basal area per area [

4], has long been recognized as a crucial factor affecting white oaks forest dynamics, especially concerning the competition for essential resources such as sunlight, water, and soil nutrients. High stand densities can exacerbate competition, leading to increased susceptibility to stressors such as drought, pests, and diseases, which may result in tree mortality [

5]. This can influence the prevalence of fungal diseases such as oak wilt and insect pests such as the gypsy moth (

Lymantria dispar), both of which have been shown to have a negative influence on white oak populations. For instance, scientists discovered that dense white oak stands were more commonly damaged by gypsy moth outbreaks, as the proximity of trees facilitated the rapid spread of defoliation [

6]. Similarly, reports have shown that oak wilt can spread more easily through interconnected root systems in high-density stands, leading to localized but significant mortality events [

7]. Conversely, lower stand densities may reduce competition and promote growth but could also make individual trees more vulnerable to environmental extremes.

White oak is sensitive to soil conditions since it requires well-drained, nutrient-rich soil for maximum growth. Soil texture, including the proportions of sand, silt, and clay, has a direct impact on water retention and drainage, all of which are critical for tree health [

8]. White oak thrives on loamy soils when there is a balance of moisture and aeration, whereas clay-heavy or poorly drained soils might cause waterlogging, root rot, and other stress-related problems that contribute to higher mortality in oaks [

9]. Furthermore, coarse-textured soils may exacerbate water shortages during droughts, rendering plants more susceptible to mortality in thick stands where competition for water is increased.

Soil properties such as moisture content, nutrient availability, and texture are also important in determining white oaks’ tree health and survival. In the eastern US, where soils are highly varied, the interplay of soil conditions and stand density may play a critical influence in defining white oak decline [

10]. Soils that are poorly drained or have low fertility might impede tree growth and recovery, especially in high-density stands where resource competition is strong. On the other hand, soils with a high organic matter content and improved nutrient cycling, may support trees, even in thick stands. Soil moisture and organic matter concentration are other important factors in determining the stand density of white oaks [

11]. Organic matter improves soil structure, increases moisture retention, and provides a delayed release of nutrients, all of which are required for good tree growth. The white oaks with increased organic matter content have lower mortality rates, owing to improved water and nutrient availability [

12]. Soils with low organic content, which are common in degraded or over-harvested forests, may result in greater death rates due to increased sensitivity to drought stress and nutrient limits, especially in dense stands with intense resource competition.

A significant research gap exists regarding the role of soil properties influencing the stand density of declining white oaks. While previous studies have broadly investigated the relationship between soil properties on oak growth, the specific effects of different soil textures, such as clay loam, fine sandy loam, and loamy fine sand, on the stand density of declining of white oaks have received limited attention. Moreover, the interaction between soil texture, soil organic matter, and the total available water (TAW) concerning stand density of declining white oaks remains under-explored. Current research primarily focuses on general factors influencing oak decline, such as climate variability and biotic stressors (e.g., pest and competition) [

13], but there is insufficient data on how particular soil attributes, especially in combination with moisture availability, directly affect white oak stand density across broader scales. This study aims to (1) assess the stand density of declining white oaks across the eastern US and (2) investigate the relationship between the stand density of declining white oaks and soil properties. Specifically, we hypothesized that the very low total available water (TAW) and clay loam soil significantly impact the stand density of declining white oaks. By examining these factors, we seek to provide insights into how soil texture, moisture availability, and organic matter influence the stand density of declining white oaks and contribute to the overall understanding of oak forest dynamics and management strategies in the eastern U.S.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

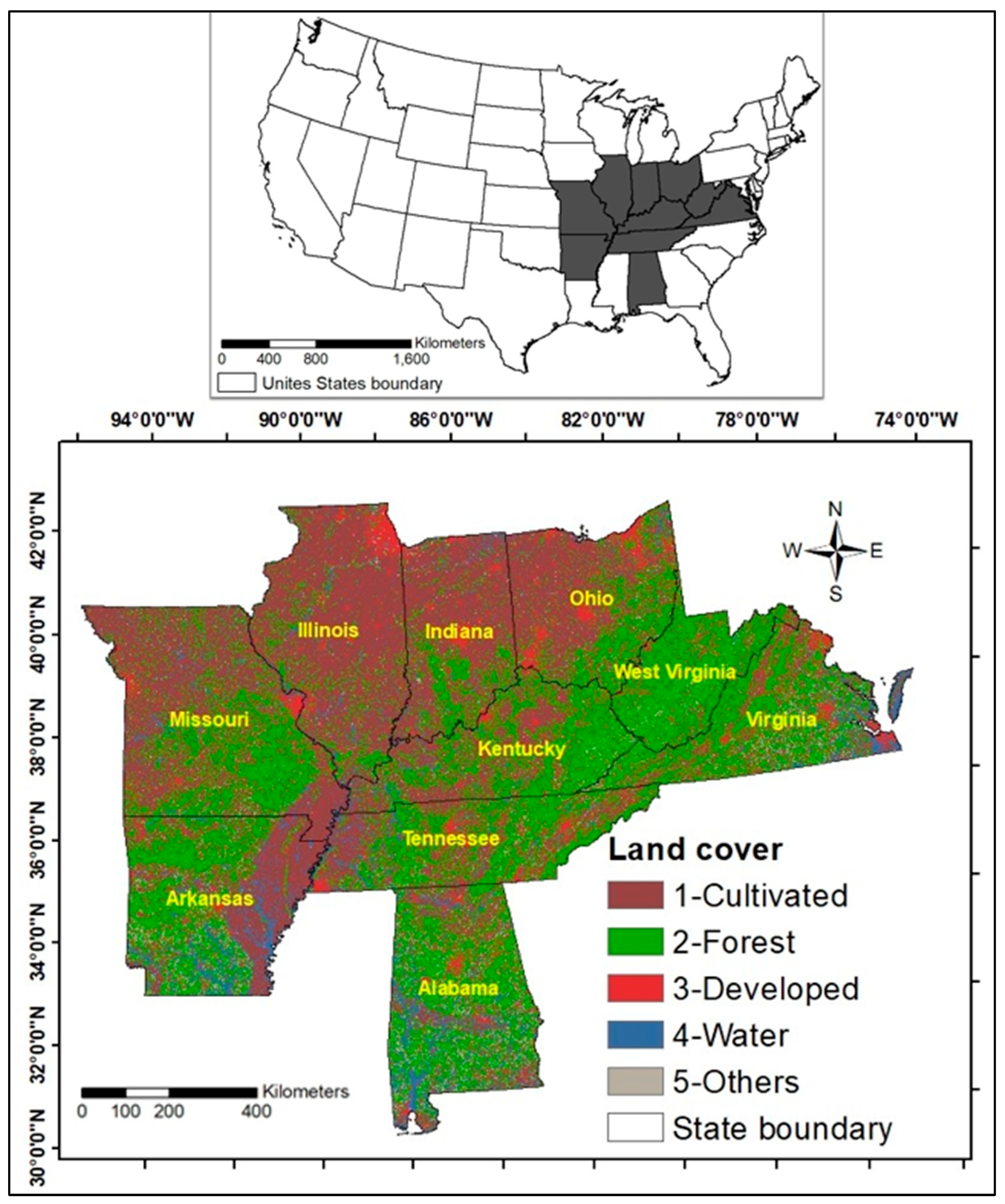

Our study area consists of vast areas of oak forests across the eastern United States [

14]. The study area contains ten states i.e., Alabama, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Missouri, Ohio, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia (

Figure 1). It has a diverse spectrum of tree species, as well as climate, soil, and topography [

15]. Our study are mostly covers forests followed by cultivated land, urban, waters and others. The geographical configuration in the eastern section of our study area is predominantly Appalachian plateaus, with low mountains, small valleys, and sharp edges. The western section ranges from highly flat central till plains to inner low plateaus, as well as Ozark Highlands. In the south, from Illinois’ central till plains Oak-Hickory to Alabama’s interior low plateau Highland Riff.

Our study area has a lengthy, hot summer and a cool winter temperature. The mean annual temperature varies from 4 to 18℃ throughout the east-west gradient, with milder temperatures in the south. The precipitation ranges from 500 to 1650mm. There are various types of soils from alfisols, mollisols, ultisols, and inceptisols. Our study area was historically dominated by oaks, pines, and hickories. Nowadays, agriculture and fast urbanization have displaced most of the forest lands in the eastern U.S.

2.2. Data Acquisition and Processing

2.2.1. Selection of Declining White Oaks Data

Plot-level data for white oaks were obtained from the USDA Forest Service DataMart, where plots were already classified into strata by the forest inventory program across various states. The weight of each stratum within the plot sampling estimation unit is determined by the proportion of the stratum [

16]. The plot dataset included geographic coordinates (latitudes and longitudes) for a sample area of 0.40 ha, though these coordinates did not account for every tree. To protect landowner privacy, the recorded plot locations by the Forest Service are within one mile of the actual locations [

16,

17]. For declining white oak plots, we focused on only forested conditions, which captured a significant proportion of white oak trees within the ten-state of the study area.

Our dataset concentrated exclusively on white oaks due to the limited research on the stand density of declining white oaks affected by soil characteristics on a broader scale. Although multiple oak species are present within the sample plots, we restricted our selection to plots containing white oaks and performed our analysis using data from surveys conducted between 1998 to 2019. The data on white oak were obtained from the USDA Forest Service and encompassed various details, including the inventory year (INVYR), which reflects the survey date and the county code (COUNTYCD), designating a specific county; unique plot number (PLOT), assigned to each white oak; species code (SPCD), which identified white oaks in this study; and tree status code (STATUSCD), which denoted live trees (coded as 1) based on the Forest inventory and Analysis (FIA) program. Additionally, the dataset included trees per acre unadjusted (TPA_UNADJ), representing the number of trees per acre theoretically represented by the sample tree according to the sample design; and the current diameter (DIA), measured at breast height (4.5 feet above ground). The dataset also incorporated the cycle (CYCLE), which denotes the set of plots measured over a specific time frame.

2.2.2. Soil Properties Data

We acquired soil variables such as soil texture, soil organic matter, and total available water from the Gridded National Soil Survey Geographic Database (gNATSGO), initially a resolution of 30 m was acquired which was later resampled to a 1km grid as our study area covers a broader scale analysis, provided by USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service [

18]. We acquired limited soil variables due to a larger dataset from ten states that requires more time to process. Therefore, we chose soil variables such as soil texture, soil organic matter, and total available water only, which might reflect a more significant impact on the stand density of declining white oaks. Also, soil texture is vital in soil characteristics which identifies the proportion of sand, silt, and clay affecting organic matter content and water-holding capacity in oak-dominated forests [

19,

20].

The soil texture classifications from SSURGO tabular data were combined with the spatial soil data provided with GIS shapefiles (

Table 1). Some regions were null for soil texture classification, which was addressed by obtaining information from the FAO dataset [

21]. We used the Soil Texture Triangle as a reference to fill all null values for soil texture by placing SSURGO and FAO spatial soil data into ArcGIS version 10.8.1 [

22]. By doing this, we obtained eighteen types of soil texture classification (including inland water) that were common in our study area. We also calculated soil organic matter and total available water using soil horizon thickness; and classified them into five classes using natural breaks (Jenks).

2.3. Data Processing and Analysis

2.3.1. Identification of Declining White Oaks

The annualized dataset spanning 1998 to 2019 was processed to identify white oak plots (

Figure 2). Following data cleaning and integration from three key tables i.e., plot, forest condition, and tree, we focused on the plot data to isolate criteria for locating white oak plots on accessible forest land. For instance, the Virginia plot table provided essential attributes, including unique plot identifiers linked to specific counties and cycles, as well as geographic coordinates corresponding to survey years. Only plots with at least one forested condition deemed accessible were selected for further analysis. The forest condition table contained comparable attributes, minus location data, and was utilized to connect with the plot data. Both the condition and tree tables were processed with the same criteria, prioritizing accessible forest land. The tree table offered crucial information such as unique plot numbers, county codes, species codes, tree diameters, tree density (trees per acre), and survey cycles.

White oaks were identified within the tree table using the species code 802. From this dataset, we calculated the basal area for white oaks, which serves as an important measure of forest structure and tree health across sampled plots.

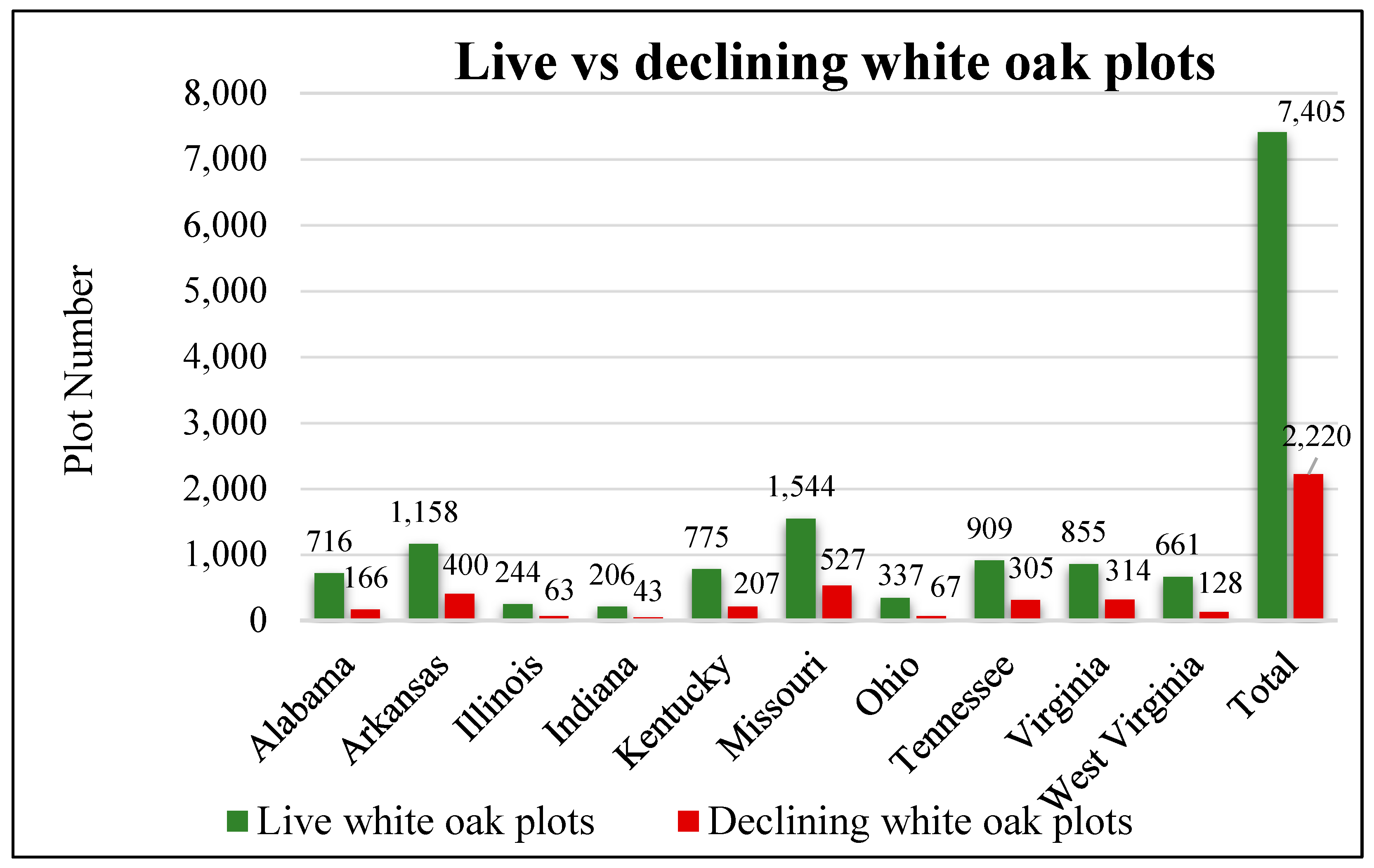

We linked the forest condition and tree tables by using unique plot identifiers. The combined dataset was then summarized by calculating the basal area (m2/ha) for each plot. Following this, we joined the summarized basal area with the plot table, again based on unique plot numbers. This resulted in a comprehensive dataset that included white oak plots, plot locations, basal area values, and survey cycles. Our dataset, initially annual, was grouped into multi-year cycles following a five-year survey period. For example, Virginia’s cycle 7 spanned inventory years from 1998 to 2002, with subsequent cycles covering 2003-2007 (cycle 7), 2008-2012 (cycle 9), 2013-2017 (cycle 10), and 2018-2019 (cycle 10). This same process was applied to other states, extracting white oak plots from cycles for corresponding survey years. Furthermore, we linked individual cycles using a formula that combined county and plot numbers COUNTYCD + (PLOT)/100,000 to identify changes over time. For instance, by subtracting the basal area of cycle 7 from cycle 8, we identified declining plots with negative basal area values. The same procedure was followed to compare cycle 8 to cycle 9, cycle 9 to cycle 10, and cycle 10 to cycle 11. To avoid duplications, we retained only one basal area value per plot. Using this method within ArcGIS version 10.8.1, we identified 2,220 declining white oaks plots out of 7,405 live white oaks plots across ten states.

The decline of white oak was calculated by using basal areas (negative) of surveyed cycles, which were grouped into five years. Some of the white oak plots were remeasured in the period from 1998 to 2019. Hence, we omitted those repeated plots to have accurate results. However, we summed up all those remeasured plots’ basal areas to obtain the true basal area. We selected all the basal areas from declining plots of white oaks concerning surveyed years. The declining plots were chosen based on reduced basal area. Reduced basal area refers to the change in basal area (negative) referring to declining white oak plots. For instance, we calculated Viginia’s reduced basal area from each cycle as:

2.3.2. Calculation of stand Density of Declining White Oaks

From the set of declining white oak plots, we captured all the basal areas corresponding to white oak decline. Based on the basal area and area provided in each plot, we calculated stand density concerning white oaks that are considered as declined. For this, we summarized all those stand densities in the plot systems so that each declining plot of white oaks has a unique number for stand density. The stand density can be expressed as:

2.3.3. Data Analysis for the Relationship Between Stand Density of Declining White Oaks and Soil Properties

We did a log transformation for the stand density of declining white oaks so that our data distribution could achieve normality. Basal area per area from declining plots of white oaks was calculated for stand density. Soil textures were classified (18 classes in our study area) taking a reference from the Food and Agriculture Organization Soils Portal based on the World Reference Base (WRB) soil classification system (

https://www.fao.org/soils-portal/data-hub/soil-classification/en/). We interpolated soil organic matter and TAW and used the interpolated results to compare them with the stand density of declining white oaks. Soil organic matter and TAW percentage were classified into five classes i.e., very low, low, medium, high, and very high using natural breaks (Jenks) from ArcGIS version 10.8.1. Our data were analyzed using R studio [

23], in which we fitted a linear model (

lm) to build the relationship between stand density of declining white oaks and soil variables using significance levels at α = 0.05. The linear regression model equation for stand density with respect to soil variables was expressed as:

In this model, y represents the stand density of declining white oaks as the dependent variable; β0 is the y-intercept, and β1, β2, and β3 are slope coefficients for each independent variable X. Here, X1 is the soil texture class, X2 is the soil organic matter class, X3 represents the total available water class, with e as the error term.

3. Results

3.1. Relationship Between Stand Density of Declining White Oaks and Soil Variables

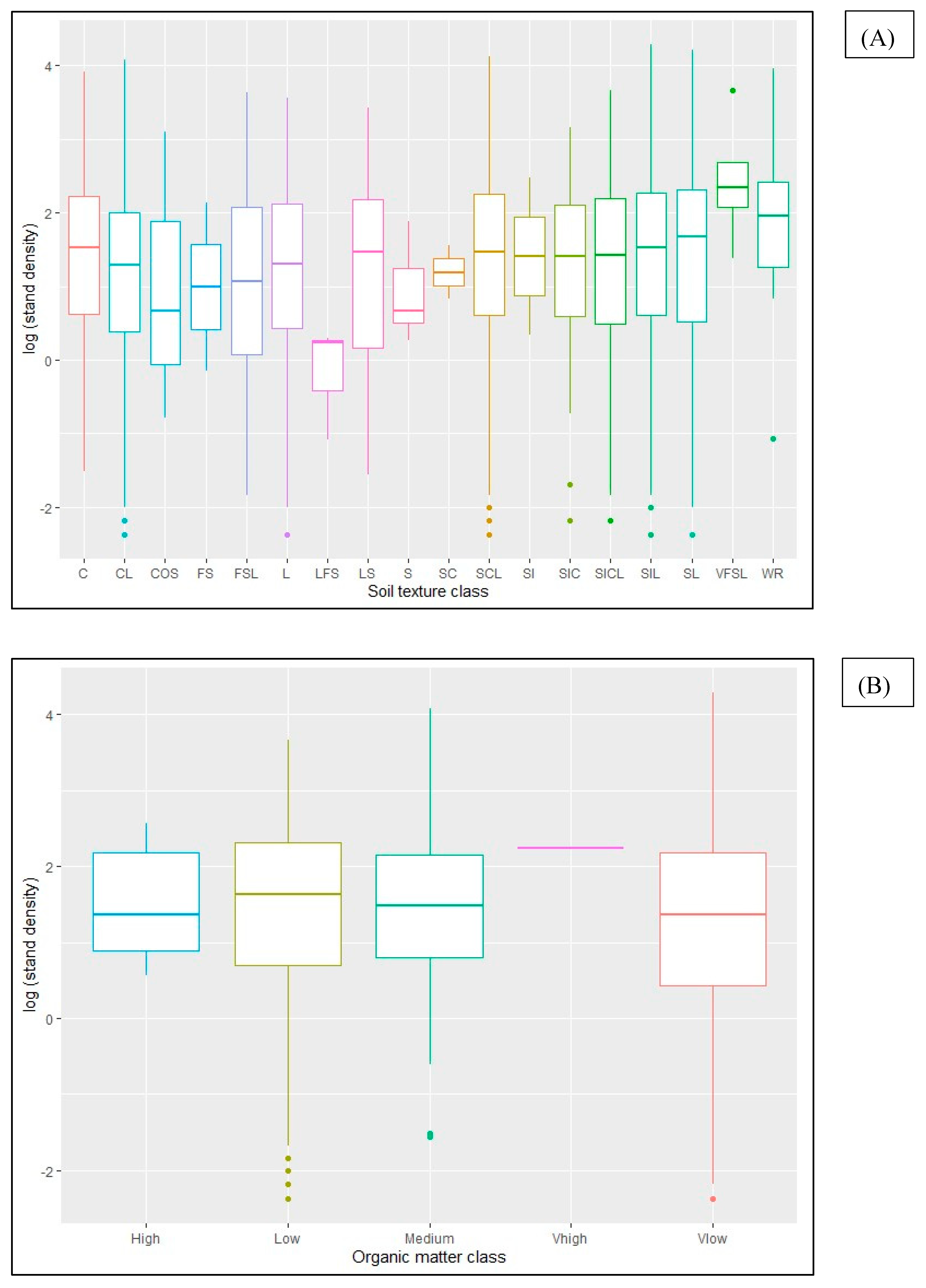

Our box plot analysis indicated a higher tendency of VFSL (i.e., approx. 2.1 m

2/ha) concerning the stand density of declining white oaks as compared to other soil variables (

Figure 3A). This suggests that VFSL has a greater degree of variability in relation to the stand density of declining white oaks. However, there was a lower tendency for LFS in relation to stand density of declining white oaks revealing lower distributional variation between them. The results reveal a significant relationship between the stand density of declining white oaks and various soil properties, particularly soil texture, organic matter, and total available water (p = 0.00;

Table 1). The analysis indicated that soil texture plays a key role, with loamy fine sand (β = -1.50; p = 0.04) all showing a negative linear relationship with the stan density of declining white oaks. This suggests that as the content of these soil types increases, the density of declining white oaks decreases, implying that certain soil textures may exacerbate white oaks’ decline.

Interestingly, no statistically significant relationships were found between soil organic matter and stand density, though the very high organic matter exhibited a higher tendency to stand density of declining white oaks (2 m

2/ha) than other organic matter classes (

Figure 3B). While the remaining classes showed positive relationships with stand density, their impact was not as pronounced from our regression analysis.

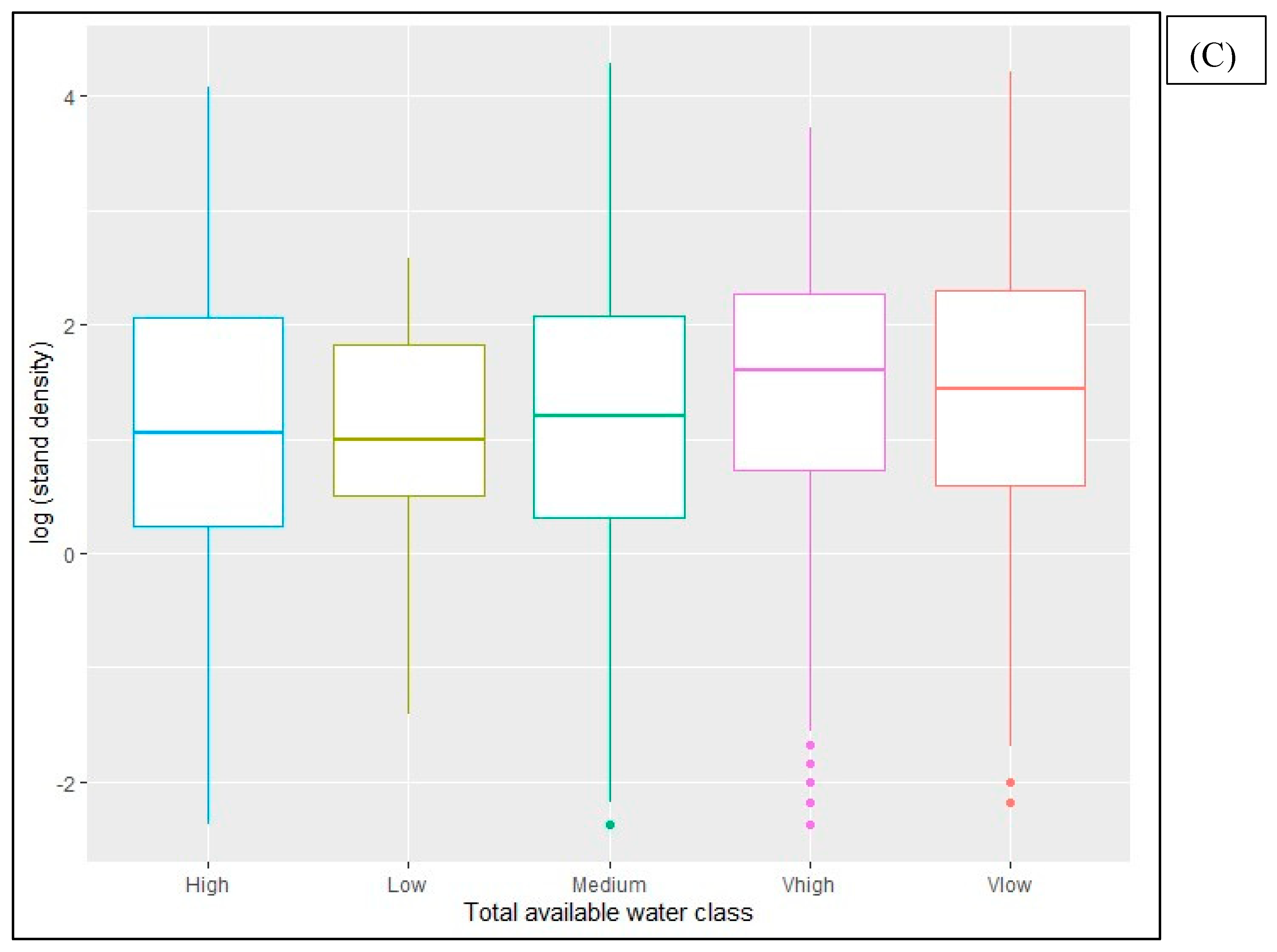

The box plot analysis showed that the very high total available water class exhibited a greater degree of variability in relation to the stand density of declining white oaks (

Figure 3C). Additionally, the analysis highlighted a significant distributional variation in the stand density of declining white oaks within the very low TAW class, indicating that both extremes of water availability have a marked influence on the data distribution of the stand density of declining white oaks. A positive coefficient indicates that higher levels of TAW are linked to an increase in the stand density of declining white oaks (β = 0.32, p = 0.00). This might reveal that white oak stands in areas with very high soil moisture tend to have higher density, potentially because these conditions support tree growth but may also lead to stress factors like waterlogging or pathogen susceptibility, which can contribute to white oak decline. A positive coefficient for very low TAW suggests that drought-prone areas are more vulnerable to white oak decline reducing the stand density of white oaks (β = 0.28 and p = 0.001;

Table 2).

These results suggest that specific soil textures and water availability play crucial roles in the analysis of the stand density of declining white oaks, providing insights into how soil characteristics influence tree mortality. Effective management strategies might involve focusing on soil properties to better understand and mitigate white oak decline by managing stand density across the eastern US.

4. Discussion

4.1. Soil Variables Effects on Stand Density of Declining White Oaks and Their Ecological Significance

The relationship between TAW and stand density of declining white oaks offers valuable insights into the ecological dynamics affecting white oak forests in the eastern US. The significant variations observed between very high and very low TAW classes and their impact on white oak stand density indicate that extremes in water availability are critical factors influencing white oak decline. This suggests that both insufficient and excessive water availability can induce physiological stress in oaks, making them more susceptible to other biotic and abiotic stressors [

24].

In regions with very low TAW, water limitations are likely due to a primary factor driving white oak decline. Soil moisture deficits can lead to hydraulic failure, causing reduced photosynthesis, growth inhibition, and ultimately, tree death. Water scarcity such as prolonged drought conditions has been linked to reduced photosynthetic activity, impaired stomatal conductance, and diminished carbon assimilation in white oaks. For instance, Kabrick et al. [

25] and Khadka et al. [

2] reported that a decline in white oaks occurred across various U.S. regions, including Arkansas and Missouri, where periods of water scarcity contribute to affect white oaks by weakening the trees’ resilience to pests and diseases. The findings of our study align with other researchers, as declining white oaks’ stand density with limited access to water in very low water availability likely suffers from the adverse effects of moisture stress and competition for water resources [

26].

Conversely, the results indicating a significant relationship between very high TAW and stand density of declining white oaks may seem counterintuitive, but it suggests that soil drainage and aeration issues are involved in the process. Such drainage issues often indicate soils with excessive water retention experiencing poor aeration, leading to hypoxic conditions in the root zone of white oaks [

27]. Studies have found that white oak roots have suffered from oxygen deprivation in waterlogged soils, reducing their ability to absorb nutrients and weakening the trees over time [

28]. Such conditions also create environments favorable for root rot pathogens, further accelerating white oak decline. Studies suggest that poorly drained soils in regions of the southeastern US are affected by pathogens like phytophthora, which thrived in saturated conditions and infected oak tree roots [

29]. This dynamic of excess water contributing to white oak decline affecting the stand density might suggest that white oaks are sensitive to excess moisture in the soil.

Clay loam soils, characterized by fine particles and moderate water retention, were found to be negatively affecting the stand density of declining white oaks. Soils with high clay content often have poor drainage and can become compacted, limiting root growth and oxygen availability, leading to stress in white oaks [

30]. These soils also tend to hold more moisture, which can exacerbate root diseases such as Phytophthora root rot, which thrives in waterlogged conditions and is a known factor in oak decline [

31]. The negative association between clay loam soils and oak density is reflective of these physiological and pathological stresses that can arise when roots are deprived of sufficient aeration and drainage. For instance, in the southeastern US, oak decline has been linked to poorly drained soils with high clay content, particularly in bottomland and riparian zones [

32]. This suggests that in areas where clay loam is prevalent, forest managers need to consider soil treatments or hydrological modifications to enhance drainage and reduce the risk of mortality associated with root disease and poor soil aeration.

The negative relationship between fine sandy loam and declining white oak stand density might be attributed to its moderate water retention capacity. While this soil type offers improved aeration, its reduced capacity to hold water compared to more loamy soils may lead to increased moisture stress during drought conditions, which are becoming more frequent in the eastern US due to climate change. Pinto et al. [

33] reported that white oak stand density is particularly sensitive to soil moisture availability, and in regions with fine sandy loam soils, fluctuating moisture levels might exacerbate water stress during dry periods, contributing to higher rates of white oak decline. Fine sandy loam soils, while more favorable for root growth than clay loam, may still present challenges under prolonged drought conditions, which could explain the negative association with white oak’s stand density observed in this study [

34].

Our study also indicated that the negative relationship between loamy fine sand and declining white oak stand density highlighting the challenges posed by soils with high sand content. Loamy fine sand soils typically have low water retention capacity, which can lead to rapid drying after precipitation events. In such soils, white oaks may experience chronic moisture stress, particularly in areas with limited rainfall or in years of drought [

35]. This moisture deficit can limit nutrient uptake and reduce the overall health and vigor of white oaks, making them more susceptible to mortality. For instance, in regions with predominantly sandy soils such as sandy uplands, white oak often struggles to maintain adequate moisture levels, which can result in reduced growth and higher declining rates [

36]. The findings from this study align with other research showing that oak species in sandy soils often exhibit lower productivity and higher vulnerability to environmental stressors, including drought [

37].

4.2. Management Implications

The impacts of extreme TAW levels highlight the vulnerability of white oak stands to both droughts and waterlogging conditions that are expected to become more prevalent with ongoing climate variability. Forest managers may need to adapt silvicultural practices to improve soil water management in regions prone to either extreme, through techniques like thinning, soil management programs, or even hydrological interventions to promote better drainage or water retention [

38,

39]. Managing white oak stand density in response to these water-related challenges will be key to maintaining healthy white oak populations and their ecological functions, including habitat provision, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration, across diverse landscapes in the eastern US.

From a management perspective, forest managers can use this information to tailor silvicultural practices based on soil characteristics. For instance, in areas dominated by clay loam or loamy fine sand, practices such as soil amendments, or drainage improvements may be necessary to reduce stress on white oak stand density and mitigate future decline. Furthermore, understanding these soil-oak tree interactions can help guide reforestation efforts, ensuring that oak species are to be planted in specific soil types where they are more likely to thrive [

40,

41].

4.3. Limitations of the Study

The large spatial extent of the study area i.e., eastern US, which spans multiple states, introduces significant variability in climate, land use, and forest management practices, potentially confounding the observed relationships between stand density and soil properties. Additionally, the plot sampling from FIA might not have captured subtle variations in soil properties at finer scales. Our data covers the period from 1998 to 2019, although this period is significant, annual fluctuations in climate (droughts, heatwaves, etc.) and disturbances (insect outbreaks, fire, etc.) could have had strong year-specific effects on the stand density of white oak and its decline. Aggregating data into multiyear cycles may obscure these short-term effects, leading to a simplified interpretation of long-term trends. Furthermore, soil properties such as texture, organic matter, and water availability were likely derived from regional soil datasets (e.g., gNATSGO). However, the resolution of these datasets may not capture small-scale heterogeneity in soil properties at each plot location, potentially introducing bias in the relationship between soil variables and declining white oak stand density.

White oak decline is often influenced by complexities of stand dynamics, such as tree composition, succession, and age structure as well as multiple interacting factors, including biotic stressors like pests and pathogens, which are not fully captured in our analysis and might have brought biased results. However, the effects of soil characteristics on the stand density of declining white oaks might be useful to forest managers and landowners for a general understanding of white oak stands and their decline in the broader perspective of the eastern US.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that soil characteristics play a significant role in influencing the stand density of declining white oaks across the eastern United States. Specifically, the findings revealed that TAW and soil texture such as clay loam, fine sandy loam, and loamy fine sand exhibit significant relationships with the stand density of white oaks, highlighting the sensitivity of oak forests to variations in soil conditions.

Our study indicated a positive relationship between both very low and very high TAW and stand density, suggesting that moisture availability influences oak stand dynamics at both extremes. White oaks in regions with very low TAW might be more vulnerable to drought, leading to a decline in stand density. Conversely, areas with very high TAW, possibly due to excessive water retention, may create conditions of poor drainage or saturation, which could also reduce stand vigor. This dual impact of water availability points to the need for further investigation into how soil moisture variability drives a decline in white oaks’ stand density, especially under the increasing variability in climate patterns across the eastern U.S.

We found a negative relationship between the stand density of declining white oaks and soil textures, which suggests more compacted or nutrient-poor soils are less favorable for white oak sustainability. These soil types may restrict root growth or limit nutrient availability, thereby reducing the resilience and productivity of white oak stands. This indicates the importance of soil texture in forest management and the potential need for targeted soil amendments or restoration strategies in areas dominated by these soil types.

Future studies should integrate climatic factors, such as precipitation and temperature, alongside soil properties to better understand the interactive effects of soil and climate on the stand density of declining white oaks. Considering the effects of drought, heatwaves, and extreme weather events will help refine predictions of white oak stand density conditions in response to changing environmental conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.; methodology, S.K.; validation, S.K., and S.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.K.; writing—review and editing, S.K., and S.B.; supervision, S.B.; project administration, S.B.; funding acquisition, S.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

United States Department of Agriculture/National Institute of Food and Agriculture 1890 Capacity Building Grant.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Lincoln University of Missouri for its facilities and support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Cabrera, S.; Alexander, H.D.; Willis, J.L.; Anderson, C.J. Midstory Removal of Encroaching Species Has Minimal Impacts on Fuels and Fire Behavior Regardless of Burn Season in a Degraded Pine-Oak Mixture. For Ecol Manage 2023, 544. [CrossRef]

- Khadka, S.; He, H.S.; Bardhan, S. Investigating the Spatial Pattern of White Oak (Quercus Alba L.) Mortality Using Ripley’s K Function Across the Ten States of the Eastern US. Forests 2024, 15, 1809. [CrossRef]

- Abbott, A.G.; Staton, M.E.; Lohtka, J.M.; DeWald, L.E.; Zhebentyayeva, T.; Kapoor, B.; Thomas, A.M.; Larson, D.A.; Hadziabdic, D.; DeBolt, S.; et al. Will “Tall Oaks from Little Acorns Grow”? White Oak (Quercus Alba) Biology in the Anthropocene. Forests 2024, 15. [CrossRef]

- Zeide, B. Comparison of Self-Thinning Models: An Exercise in Reasoning. Trees - Structure and Function 2010, 24, 1117–1126. [CrossRef]

- Restaino, C.; Young, D.J.N.; Estes, B.; Gross, S.; Wuenschel, A.; Meyer, M.; Safford, H. Forest Structure and Climate Mediate Drought-Induced Tree Mortality in Forests of the Sierra Nevada, USA. Ecological Applications 2019, 29. [CrossRef]

- Muzika, R.M. Opportunities for Silviculture in Management and Restoration of Forests Affected by Invasive Species. Biol Invasions 2017, 19, 3419–3435. [CrossRef]

- Juzwik, J.; Appel, D.N.; Macdonald, W.L.; Burks, S. Challenges and Successes in Managing Oak Wilt in the United States. Plant Dis 2011, 95, 888–900. [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Soil Organic Matter and Water Retention. Agron J 2020, 112, 3265–3277. [CrossRef]

- Iverson, L.R.; Hutchinson, T.F.; Prasad, A.M.; Peters, M.P. Thinning, Fire, and Oak Regeneration across a Heterogeneous Landscape in the Eastern U.S.: 7-Year Results. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255, 3035–3050. [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.M.; Long, R.P.; Madden, L. V.; Bonello, P. Association of Phytophthora Cinnamomi with White Oak Decline in Southern Ohio. Plant Dis 2010, 94, 1026–1034. [CrossRef]

- Brockett, B.F.T.; Prescott, C.E.; Grayston, S.J. Soil Moisture Is the Major Factor Influencing Microbial Community Structure and Enzyme Activities across Seven Biogeoclimatic Zones in Western Canada. Soil Biol Biochem 2012, 44, 9–20. [CrossRef]

- Lyczak, S.J.; Kabrick, J.M.; Knapp, B.O. Long-Term Effects of Organic Matter Removal, Compaction, and Vegetation Control on Tree Survival and Growth in Coarse-Textured, Low-Productivity Soils. For Ecol Manage 2021, 496. [CrossRef]

- Teshome, D.T.; Zharare, G.E.; Naidoo, S. The Threat of the Combined Effect of Biotic and Abiotic Stress Factors in Forestry Under a Changing Climate. Front Plant Sci 2020, 11. [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.L.; Schweitzer, C.J. Stand Dynamics of an Oak Woodland Forest and Effects of a Restoration Treatment on Forest Health. For Ecol Manage 2016, 381, 258–267. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.Y.; Yan, D.H.; Song, X.S.; Wang, H. Impact of Biochar on Water Holding Capacity of Two Chinese Agricultural Soil. In Proceedings of the Advanced Materials Research; Trans Tech Publications Ltd, 2014; Vol. 941–944, pp. 952–955.

- Woudenberg, S.W.; Conkling, B.L.; O’connell, B.M.; Lapoint, E.B.; Turner, J.A.; Waddell, K.L. The Forest Inventory and Analysis Database: Database Description and Users Manual Version 4.0 for Phase 2; 2010;

- Khadka, S.; Gyawali, B.R.; Shrestha, T.B.; Cristan, R.; Banerjee, S. “Ban”; Antonious, G.; Poudel, H.P. Exploring Relationships among Landownership, Landscape Diversity, and Ecological Productivity in Kentucky. Land use policy 2021, 111. [CrossRef]

- Salley, S.W.; Talbot, C.J.; Brown, J.R. The Natural Resources Conservation Service Land Resource Hierarchy and Ecological Sites. Soil Science Society of America Journal 2016, 80, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Yoo, H.; Lim, H.; Kim, J.; Choi, H.T. Impacts of Soil Properties, Topography, and Environmental Features on Soil Water Holding Capacities (SWHCs) and Their Interrelationships. Land (Basel) 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Slesak, R.A.; Palik, B.J.; D’Amato, A.W.; Kurth, V.J. Changes in Soil Physical and Chemical Properties Following Organic Matter Removal and Compaction: 20-Year Response of the Aspen Lake-States Long Term Soil Productivity Installations. For Ecol Manage 2017, 392, 68–77. [CrossRef]

- Pietsch, D.; Lucke, B. Soil Substrate Classification and the FAO and World Reference Base Systems: Examples from Yemen and Jordan. Eur J Soil Sci 2008, 59, 824–834. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.M.; Franz, T.E.; Abimbola, O.; Steele, D.D.; Flores, J.P.; Jia, X.; Scherer, T.F.; Rudnick, D.R.; Neale, C.M.U. Feasibility Assessment on Use of Proximal Geophysical Sensors to Support Precision Management. Vadose Zone Journal 2022, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, E.; Agca, M.; Adiguzel, F.; Cetin, M. Spatial Data Analysis with R Programming for Environment. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment 2019, 25, 1521–1530. [CrossRef]

- Brunner, I.; Herzog, C.; Dawes, M.A.; Arend, M.; Sperisen, C. How Tree Roots Respond to Drought. Front Plant Sci 2015, 6. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; He, H.S.; Kabrick, J.M. A Remote Sensing-Assisted Risk Rating Study to Predict Oak Decline and Recovery in the Missouri Ozark Highlands, USA. GIsci Remote Sens 2008, 45, 406–425. [CrossRef]

- del Castillo, J.; Comas, C.; Voltas, J.; Ferrio, J.P. Dynamics of Competition over Water in a Mixed Oak-Pine Mediterranean Forest: Spatio-Temporal and Physiological Components. For Ecol Manage 2016, 382, 214–224. [CrossRef]

- Watson, G.W.; Hewitt, A.M.; Custic, M.; Lo, M. The Management of Tree Root Systems in Urban and Suburban Settings: A Review of Soil Influence on Root Growth; 2014; Vol. 40;

- Quine, C.A.N., D.S., D.-L.M.-L., J.R., K.K. Action Oak Knowledge Review : An Assessment of the Current Evidence on Oak Health, Identification of Evidence Gaps and Prioritisation of Research Needs; Action Oak, 2019; ISBN 9781527241930.

- Cahill, D.M.; Rookes, J.E.; Wilson, B.A.; Gibson, L.; McDougall, K.L. Turner Review No. 17. Phytophthora Cinnamomi and Australia’s Biodiversity: Impacts, Predictions and Progress towards Control. Aust J Bot 2008, 56, 279–310. [CrossRef]

- Batey, T. Soil Compaction and Soil Management - A Review. Soil Use Manag 2009, 25, 335–345. [CrossRef]

- Balci, Y.; Halmschlager, E. Incidence of Phytophthora Species in Oak Forests in Austria and Their Possible Involvement in Oak Decline. For Pathol 2003, 33, 157–174. [CrossRef]

- Kabrick, J.M.; Dey, D.C.; Jensen, R.G.; Wallendorf, M. The Role of Environmental Factors in Oak Decline and Mortality in the Ozark Highlands. For Ecol Manage 2008, 255, 1409–1417. [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.R.; Marshall, J.D.; Dumroese, R.K.; Davis, A.S.; Cobos, D.R. Seedling Establishment and Physiological Responses to Temporal and Spatial Soil Moisture Changes. New For (Dordr) 2016, 47, 223–241. [CrossRef]

- Steckel, M.; del Río, M.; Heym, M.; Aldea, J.; Bielak, K.; Brazaitis, G.; Černý, J.; Coll, L.; Collet, C.; Ehbrecht, M.; et al. Species Mixing Reduces Drought Susceptibility of Scots Pine (Pinus Sylvestris L.) and Oak (Quercus Robur L., Quercus Petraea (Matt.) Liebl.) – Site Water Supply and Fertility Modify the Mixing Effect. For Ecol Manage 2020, 461. [CrossRef]

- Keyser, T.L.; Brown, P.M. Drought Response of Upland Oak (Quercus L.) Species in Appalachian Hardwood Forests of the Southeastern USA. Ann For Sci 2016, 73, 971–986. [CrossRef]

- Surrette, S.B.; Aquilani, S.M.; Brewer, J.S. Current and Historical Composition and Size Structure of Upland Forests across a Soil Gradient in North Mississippi. Southeastern Naturalist 2008, 7, 27–48. [CrossRef]

- Kotlarz, J.; Nasilowska, S.A.; Rotchimmel, K.; Kubiak, K.; Kacprzak, M. Species Diversity of Oak Stands and Its Significance for Drought Resistance. Forests 2018, 9. [CrossRef]

- Arthur, M.A.; Alexander, H.D.; Dey, D.C.; Schweitzer, C.J.; Loftis, D.L. Refining the Oak-Fire Hypothesis for Management of Oak-Dominated Forests of the Eastern United States. J For 2012, 110, 257–266. [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Puettmann, K.; Wilson, E.; Messier, C.; Kames, S.; Dhar, A. Can Boreal and Temperate Forest Management Be Adapted to the Uncertainties of 21st Century Climate Change? CRC Crit Rev Plant Sci 2014, 33, 251–285. [CrossRef]

- Löf, M.; Dey, D.C.; Navarro, R.M.; Jacobs, D.F. Mechanical Site Preparation for Forest Restoration. New For (Dordr) 2012, 43, 825–848. [CrossRef]

- Das, S.K.; Ghosh, G.K.; Avasthe, R. Valorizing Biomass to Engineered Biochar and Its Impact on Soil, Plant, Water, and Microbial Dynamics: A Review. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2022, 12, 4183–4199. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).