1. Introduction

Air quality monitoring and activity recognition are of paramount importance in ensuring healthy and safe environments, particularly in indoor spaces such as residential, commercial, and public buildings. In recent years, the field of activity recognition has garnered significant attention due to its wide-ranging applications across various domains, including healthcare, robotics, and human-computer interaction [

1,

2]. Activity of Daily Living (ADL) classification plays a crucial role in understanding and predicting human actions, leading to advancements in personalized healthcare and behavior analysis [

1,

3,

4].

The primary objective of ADL classification is to optimize an individual’s quality of life and promote independence. However, this research area presents numerous challenges, including variability in sensor data, inter-subject and intra-subject variability, and privacy concerns [

5,

6,

7]. To address these challenges in accurately classifying ADLs from sensory data while preserving user privacy, researchers have turned to novel approach combining Deep Learning (DL) and Federated Learning (FL) techniques, specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which have demonstrated remarkable performance in various computer vision tasks and preserving privacy [

8,

9,

10].

FL has emerged as a powerful paradigm that enables decentralized model training across multiple edge devices or servers holding local data samples without exchanging raw data [

11]. This approach is particularly crucial for activity recognition and air quality monitoring in smart buildings, where privacy preservation is paramount. In an FL framework, each client (e.g., a smart building or user device) trains a local model on its data, sharing only model updates with a central server that aggregates them to enhance a global model [

12].

FL has demonstrated significant success across many fields such as healthcare, IoT environments, energy management, and air quality monitoring. This decentralized approach enables collaborative model training while preserving data privacy, offering substantial advantages over traditional centralized methods in handling sensitive and distributed data.>

In [

13], the authors present an energy distribution optimization solution through the analysis of energy demand in individual homes. Their approach leverages edge computing technology and utilizes a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network enhanced by a multi-head attention mechanism. The model is trained on sensor data collected from various sources to predict energy demand. To facilitate decentralized learning, they employ a FL framework, incorporating an aggregation decision module to enhance performance by rejecting poorly trained models. This method contributes to the development of a robust global FL model. To further strengthen data security, a blockchain network with a Byzantine fault tolerance mechanism and Proof of Stake (PoS) consensus is integrated into the system. The proposed architecture evaluated on a publicly available dataset, demonstrating its effectiveness and potential benefits. However in [

14], the authors introduce FedHome, an innovative cloud-edge FL framework designed for in-home health monitoring. The framework enables the training of a shared global model in the cloud while preserving data privacy by keeping user data locally at the edge devices. To address the challenges of imbalanced and non-IID data typically found in user environments, they develop a generative convolutional autoencoder (GCAE). The GCAE refines the model by generating a class-balanced dataset from users’ personal data, improving the accuracy and personalization of health monitoring. Additionally, the GCAE is lightweight, facilitating efficient transfer between the cloud and edge devices, thereby reducing the communication overhead in the FL process within FedHome. Extensive experiments on realistic human activity recognition data validate that FedHome significantly outperforms widely-adopted existing methods. The authors in [

15], introduce a novel privacy-by-design FL model based on a stacked LSTM architecture. Their approach demonstrates more than twice the training convergence speed compared to a centralized traditional LSTM model. The FL framework is evaluated on three real-world datasets generated by an IoT-based production system at General Electric’s smart buildings. It achieves state-of-the-art performance in both classification and regression tasks when compared to baseline methods. The experimental results highlight the framework’s ability to significantly reduce overall training costs while maintaining high prediction accuracy.

Our work focuses on the application of CNN-based FL methods for ADL classification and air quality monitoring, aiming to improve both accuracy and privacy. By leveraging the hierarchical nature of CNNs, which extract complex features automatically, we can effectively capture discriminative patterns and temporal dependencies from multimodal sensor data while maintaining data locality (or privacy). The proposed approach entails the development of a novel deep learning model for the classification of different activities and air quality types based on measurements collected by sensors, all within a federated learning framework.

To evaluate the effectiveness of our approach, we conduct experiments using an air quality dataset specifically curated for ADL classification, distributed across multiple simulated clients. Our contributions in this paper are twofold:

We propose a novel Fed-CNN1D-based model that accurately recognizes and classifies different types of activities and air quality based on sensor data in indoor spaces, designed to work within a federated learning framework. We implement and evaluate a FL approach for training our model across multiple clients, demonstrating its effectiveness in preserving privacy while maintaining high classification accuracy.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 describes the FL framework and our proposed local CNN architecture.

Section 3 presents the experimental setup and results, including dataset description, evaluation metrics, and comparison with centralized approaches.

Section 4 concludes the paper and discusses future directions.

2. Proposed Methodology

2.1. Pipeline of the System

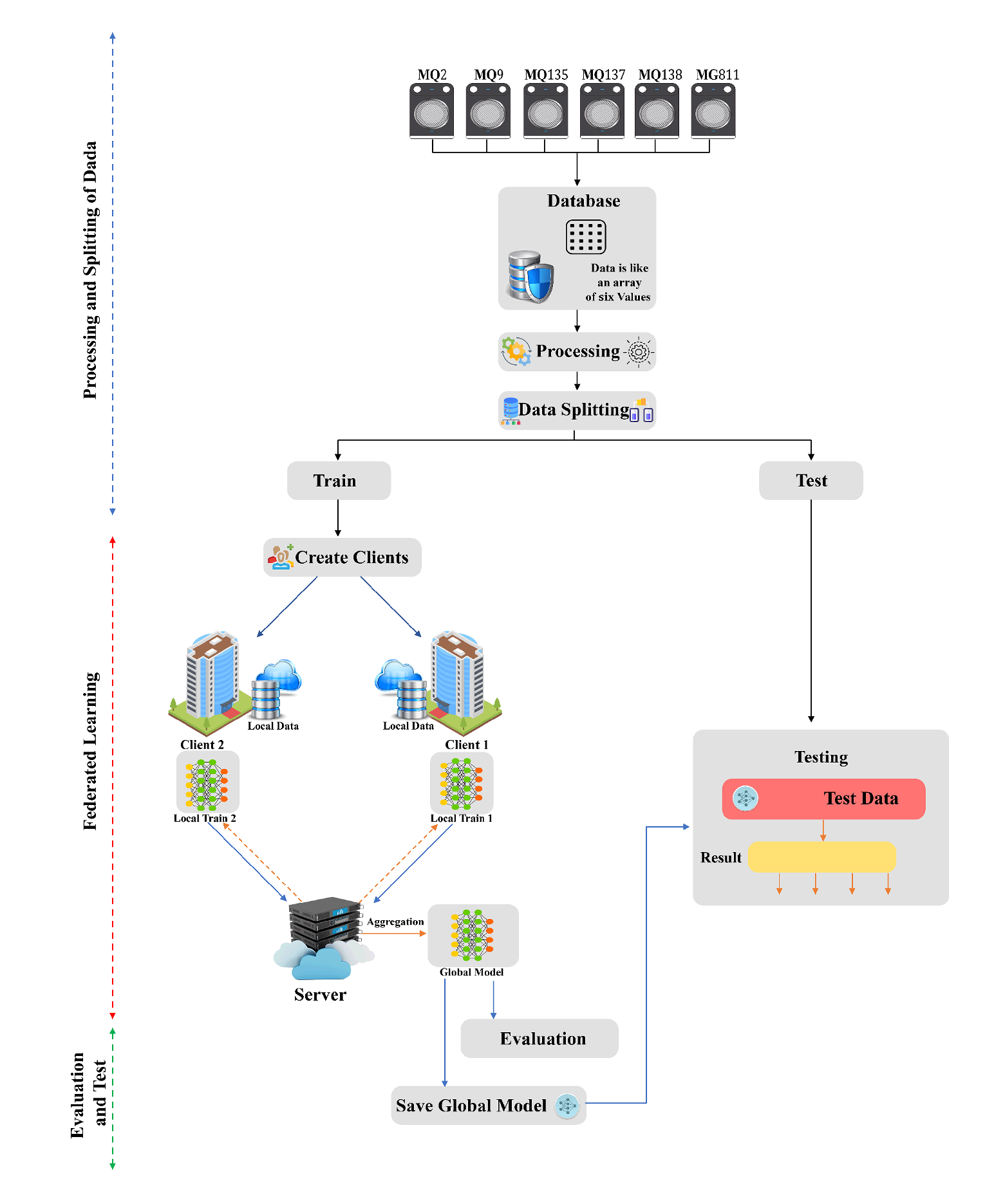

This section outlines an innovative Fed-CNN1D approach for privacy-preserving Activities of Daily Living (ADL) detection and air quality monitoring in smart building environments, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Our proposed framework employs FL techniques to address data privacy concerns while enabling sophisticated analysis across multiple locations. Our system utilizes a distributed network of strategically placed gas sensors and a novel CNN-1D model, trained locally at each site. The global model is refined through secure aggregation of local updates using FedAvg, effectively mitigating common centralized learning challenges such as data privacy risks, latency issues, and bandwidth limitations. This methodology allows for accurate activity prediction and air quality assessment without compromising individual privacy or system efficiency.

First, there are distinct five MQ-series gas sensors (MQ2, MQ9, MQ135, MQ137, MQ138), each one of this sensors is responsive to a variety of gases. Additionally, an MG-811 CO2 sensor. The MG-811 is noted for its high sensitivity to carbon dioxide and minimal susceptibility to temperature and humidity fluctuations. These sensors are strategically deployed to collect data, with outputs providing specific measurement parameters based on gas concentrations. The collected data is structured and stored in CSV format.

Table 1 presents the gas detection capabilities of each sensor, highlighting their ability to detect multiple gas types.

2.2. Data Processing

Data processing, particularly normalization, is crucial for optimizing input quality in artificial intelligence models. Normalization standardizes feature values, preventing attributes with larger magnitudes from disproportionately influencing the learning process. This critical step enhances model performance by accelerating convergence and mitigating gradient-related issues [

16,

17,

18]. Our methodology’s processing pipeline begins by addressing missing or anomalous values through interpolation and outlier detection techniques. Then, min-max scaling is applied, a widely adopted normalization technique that scales feature values between 0 and 1. This approach effectively ensures that all features, regardless of their original scale distributions, contribute proportionally to the model, reducing the risk of bias introduced by varying features magnitudes.

The normalized data is designed for compatibility with our AI-based FL models and facilitates efficient training. It involves converting raw sensor data to numerical values and reshaping it into a 2D array structure, where each sample is encoded as a feature vector [

1,

9,

19].

2.3. Data Splitting

The reshaped dataset is randomly shuffled and partitioned to create distinct subsets for model training and testing, ensuring a representative distribution of classes across both partitions [

1]. The data splitting process is performed as follows:

2.3.1. Training Set

80% of the data is allocated for training and fine-tuning local models during the local training phase of the FL process.

2.3.2. Testing Set

The remaining 20% of the data is reserved as an independent testing set. This subset is employed to assess the generalization capability and the performance of the global aggregated model [

19,

20,

21].

2.4. Create Clients

In real-world application of FL, each individual FL client possesses its own decentralized dataset to ensure data privacy and maintain data localized. As depicted in

Figure 1, the system framework has a distinct dataset for each client, comprising data from six sensors per client. Each client collects data from these sensors for local processing and communicates to share only model updates with the server. For our approach, we implement an existing database by partitioning (dividing) into two equal subsets, representing two clients, each corresponding to a different building. These subsets are used for local training at their respective smart building locations,ensuring that the data remains localized.By maintaining data locality, we adhere to privacy-preserving principles while allowing independent model training at each client.

2.5. Server

In FL system, the server function as a central entity, that coordinates communication rounds between clients. These communication rounds involve clients sending their locally trained model updates or weights to the server, which aggregates them to create a global FL model. The frequency and number of communication rounds play a critical role in model performance, as they determine how often local models are synchronized with the global model, affecting convergence speed and accuracy. Additionally, the server optimizes the global model by aggregating the local models parameters shared from all clients without accessing their local data, thus ensuring privacy. It initiates the global model, coordinates the synchronization process, and manages communication with clients, ensuring that model updates occur efficiently across all communication rounds.

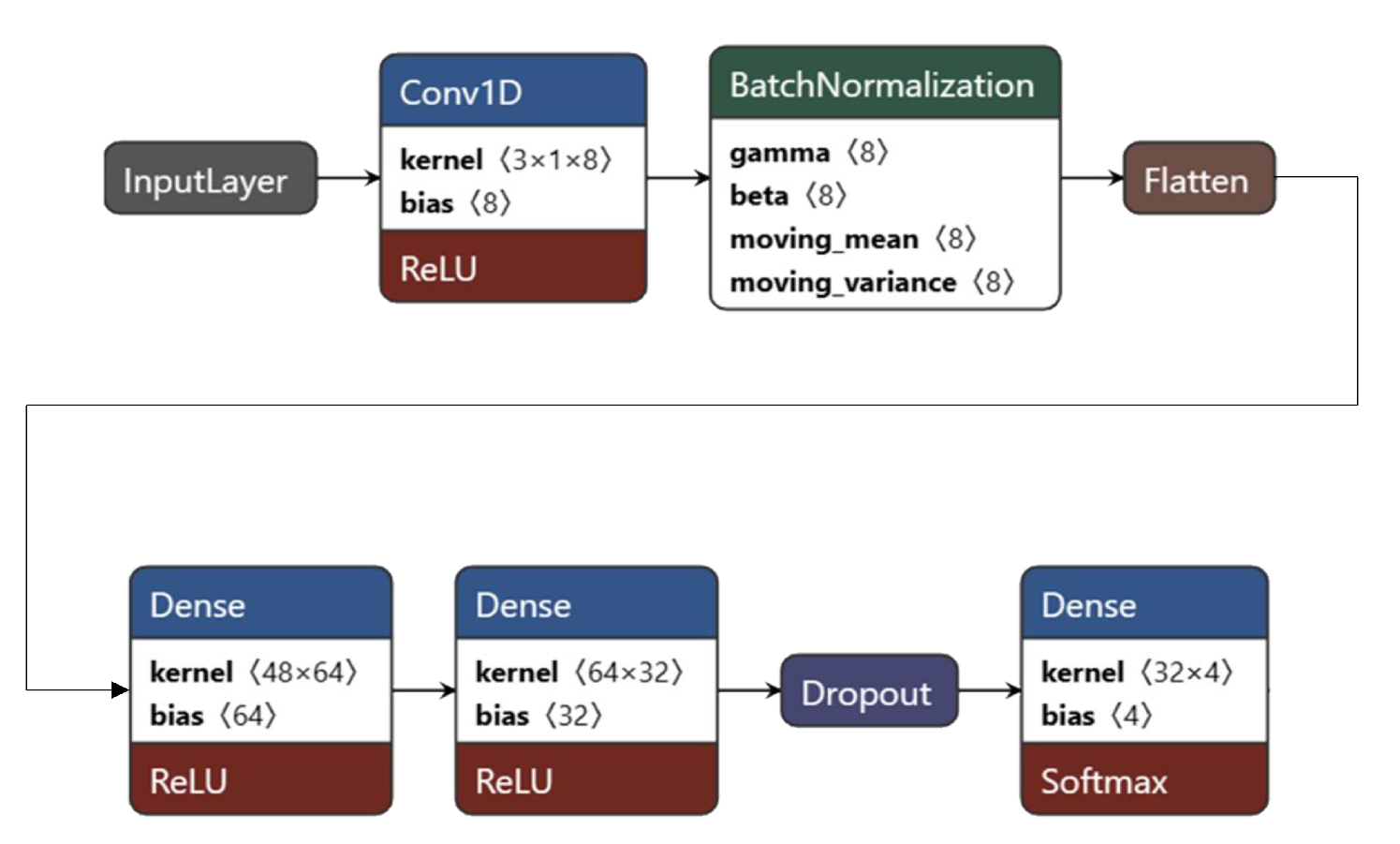

2.6. Local Model

Our system employs a DL-CNN-1D model for indoor activity and air quality detection based on gas concentration data. The architecture, initialized by a central server and disseminated to clients for local training phase of the FL process, comprises 5,412 parameters, it occupies an estimated storage space of 51 KB, and accepts a sequence of six input air quality features corresponding to sensor outputs. Local training utilizes Python with 100 communication rounds, a batch size of 64, and the Adam optimizer a popular optimization algorithm, was employed to adjust the model’s parameters and optimize its performance, with categorical cross-entropy as the loss function specifically designed for multi-class classification tasks, was utilized to measure the discrepancy between the predicted gas classes and the actual labels in the training data. As depicted in

Figure 2, the model architecture consists of a 1D Convolutional layer (8 kernels, size 3) with zero-padding and ReLU activation, followed by Batch Normalization, a flattening operation, two Dense layers (64 and 32 neurons) with ReLU activation, a Dropout layer (rate 0.3) mitigates overfitting. The output Dense layer comprises 4 nodes (corresponding to the number of categories) with softmax activation, aligning with the multi-class classification task. This FL approach involves iterative communication between clients and the server, aggregating local models into a global model for redistribution and refinement, balancing model capacity with computational efficiency for effective indoor environmental monitoring.

2.7. Aggregation

Upon completion of local models training, each client shares the trained local model with the server. The server then aggregates these received local models to create global model, through the using of FedAvg (Federated Averaging) method, involving by updating the model parameter w (weights). The server awaits for the submission of locally trained models from all clients to start the aggregation process. This aggregation of models is based on model parameters (weights), using the Equation (

1):

Here, represent the aggregated parametrs (weightes) of the global model post aggregation. K is the number of clients, n signifies the totale number of data samples from all clients, and is the number of samples from client. illustate the local objective function for client k, and dentes the local objective function the client with model parameters w.

3. Performance and Result Discussion

This section provides dataset utilized and the results visualization of our proposed Fed-CNN1D approach for indoor air quality monitoring based on activities of daily living. We implemented a two-client system located in separate buildings, each with a locally processed dataset. The FL process began with the server initializing local models and distributing them to clients, who then performed localized training on their private data. Our FL process involved periodic communication between clients and the server. After each epoch, clients shared their trained local models for aggregation. The server employed FedAvg to create an improved global model, which was then redistributed to clients. This iterative approach enhanced the global model’s accuracy while preserving data privacy and reducing computational costs. The decentralized training allowed the model to learn from diverse data sources without direct access to sensitive information, demonstrating the efficacy of FL in privacy-preserving air quality monitoring systems. The following results showcase the performance and effectiveness of our proposed Fed-CNN1D method in accurately classifying indoor activities based on air quality parameters while privacy preserving.

3.1. Dataset

The Air Quality Dataset for ADL Classification which is available, forms the foundation of our approach. This comprehensive dataset collects indoor gas concentration variations over time, enabling the assessment and determination of specific activities within domestic environments. By leveraging AI, we circumvent the need for precise sensor calibration that would otherwise be required for quantitative gas concentration analysis. The dataset comprises readings from an array of six low-cost sensors, recorded at successive time intervals, and the stored values are associated with the specific action that generated them. Through appropriate data processing and ML algorithms, the system can recognize various household activities after an initial training phase. The presence of chemicals in the air is determined through a series of electrochemical gas sensors that have been selected based on the stated technical specifications on the ability to detect classes of compounds. The sensor set can be categorized into two main categories:

MQ Sensors (MQ2, MQ9, MQ135, MQ137, MQ138): These offer high sensitivity, low latency, and cost-effectiveness, with each sensor responsive to multiple gases.

Analog CO2 Gas Sensor (MG-811): This sensor exhibits excellent sensitivity to carbon dioxide, with minimal affectation by the temperature and humidity of the air.

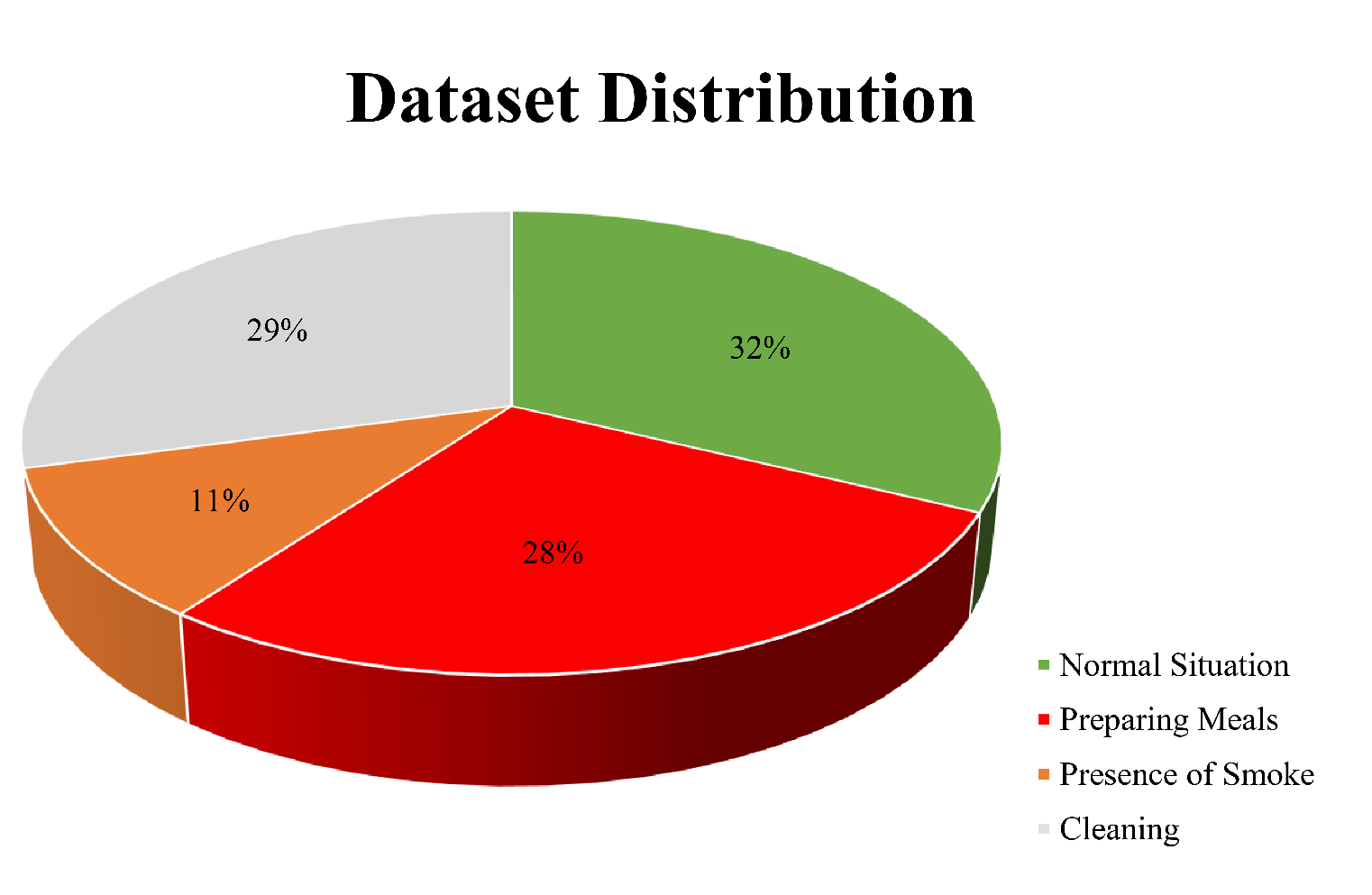

The dataset contains 1,845 samples categorized into four distinct activity types: Normal Situation, Preparing Meals, Presence of Smoke, and Cleaning. These activities are associated with distinct air compositions, accounting for various factors such as human respiration, metabolic processes, combustion/oxidation byproducts, and household detergent evaporation [

1]. As illustrated in

Figure 3, each sample consists of seven values: the first six represent sensor outputs, while the seventh is the activity label. This structured dataset enables our proposed approach to effectively learn and classify indoor activities based on air quality parameters [

1,

22].

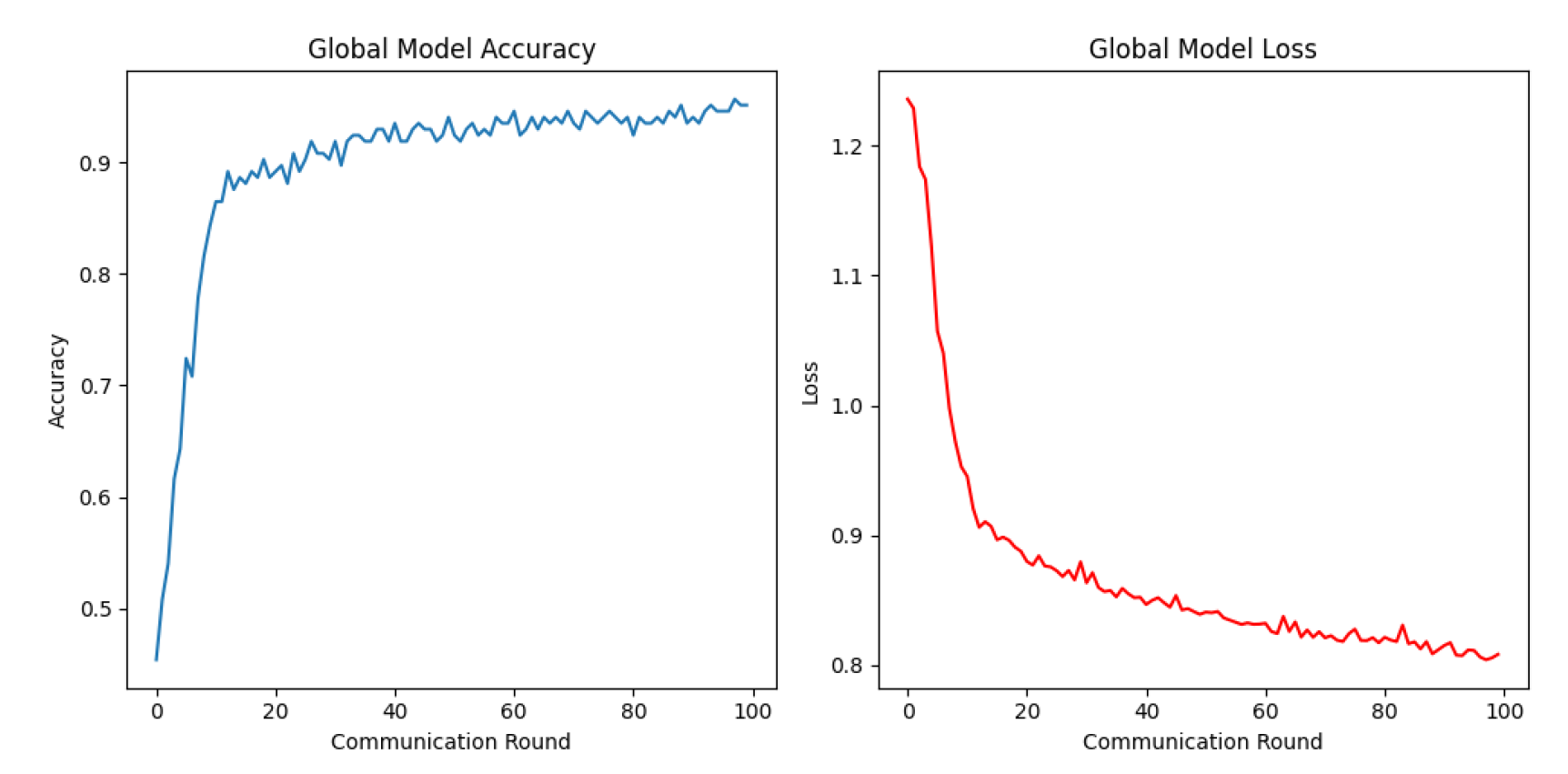

3.2. Accuracy and Loss Graph

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of accuracy and loss metrics throughout communication rounds in FL process.

Initially, the accuracy shows a proportional increase with the progression of communication rounds, starting at 30% and reaching 96.50%, indicating an enhancement in the global model’s capability to correctly categorize and identify indoor activities based on air quality data over time.> Conversely, the loss metric demonstrates an inversely proportional, decreasing significantly with the number of communication rounds, reflecting improved model fit and reduced prediction error over time. These results underscore the effectiveness of federated communication in our Fed-CNN1D approach, optimizing model performance while balancing privacy preservation and communication efficiency. The illustration demonstrates how the iterative process of FL enhances the global model’s accuracy and convergence over time.

3.3. Confusion Matrix

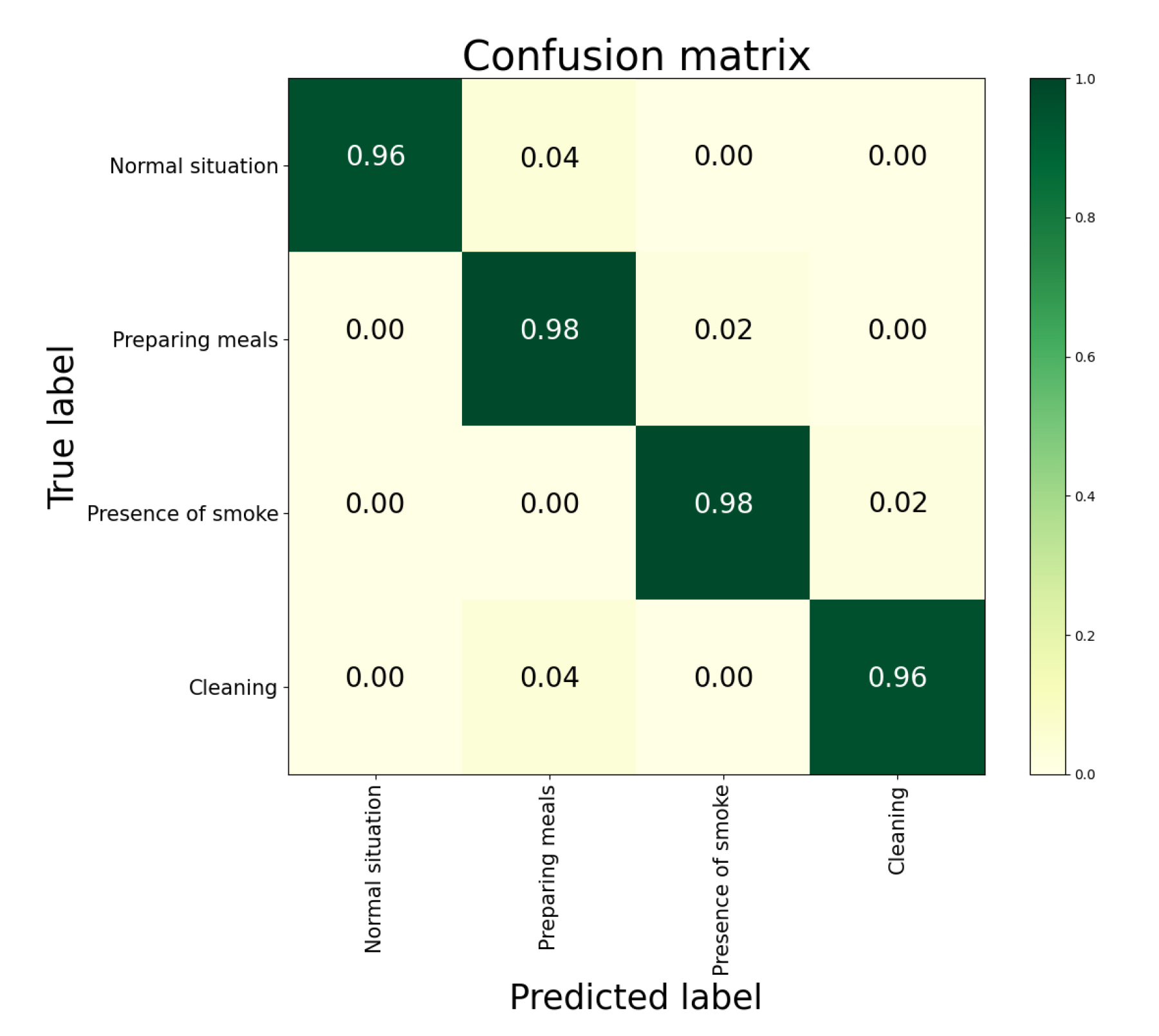

Figure 5 presents the confusion matrix, which is an important tool for a detailed evaluation of our FL global model performance. It provides a detailed summary of model predictions compared to actual class labels.

Based on the analysis of the confusion matrix reveals effective categorization capabilities across four classes: normal situation, preparing meals, presence of smoke, and cleaning activities. The diagonal elements represent accurate identification, with rates of 96%, 98%, 98%, and 96% for the respective classes. These high precision rates demonstrate the overall effectiveness of the global FL model in classifying indoor activities.> However, the off-diagonal elements highlight misclassifications, potentially caused by similarities in measurement parameters across classes. Specifically, 4% of instances in normal situation category are misclassified as preparing meals, 2% of preparing meals instances are misclassified as presence of smoke, 2% of presence of smoke instances are misclassified as cleaning, and 4% of instances in cleaning class are misclassified as preparing meals. These misclassifications suggest overlap in environmental factors such as air quality or particulate matter during these activities, making them more difficult for the model to distinguish. The similarities across activities like cleaning, preparing meals, and normal situation, which all involve changes in air quality parameters, may be the main reason of these misclassifications. Addressing this issue could involve refining the FL model’s feature extraction process to effectively capture the tiny variations between these activities, or incorporating additional data types to improve classification accuracy.>

The confusion matrix demonstrates the robustness of the FL global model while identifying specific areas for improvement. The observed misclassifications provide valuable insights for future work, where refining the model could help to better distinguish between activities with overlapping features, thereby further enhancing the overall classification performance of the system.

We evaluate the performance of our FL global model using key metrics, including accuracy, loss, recall, precision, f1-score and communication cost are summarized in

Table 2. These metrics offer a comprehensive assessment of our Fed-CNN1D model’s effectiveness in balancing classification accuracy with computational and communication efficiency, all within the privacy-preserving approach of FL for indoor air quality monitoring.

3.4. Comparison with recent related work

This section presents a comparative analysis of our Fed-CNN1D approach against recent related work using AI methods for daily living activities classification based on Air Quality dataset.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of various techniques, including ML, DL, and FL approaches. This comparison demonstrates the effectiveness and reliability of our proposed approach across multiple metrics, including accuracy, model, aggregation method, and detection (det) time and additional aspects such as privacy preservation, computational efficiency, and scalability. While accuracy and det time are crucial, our approach provide distinct advantages in areas such as privacy and system scalability. Using of FL ensures that sensitive data remains localized, mitigating privacy risks a significant advantage compared to centralized models. Moreover, the FedAvg aggregation technique employed in our Fed-CNN1D model optimizes communication efficiency by reducing the overhead typically associated with federated systems.> The best results in terms of accuracy were achieved with 1D-CNN, KNN and Random Forest, which achieved accuracies of 97.00%, 96.32%, and 96.19%, respectively. In contrast, the proposed Fed-CNN1D model achieved an accuracy of 96.50% and a det time of 15 ms. While 1D-CNN slightly outperforms our approach in accuracy, our federated framework offers more benefits, including enhanced privacy and efficiency through data localization. Furthermore, our method offers lower computational complexity, making it more efficient for deployment in distributed, privacy-sensitive environments.>

Our Fed-CNN1D approach demonstrates a balanced performance, combining high accuracy with privacy preservation, efficiency, and computational scalability, making it well-suited for real-world applications where privacy and resource optimization are critical.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we have investigated a novel privacy preserving FL approach Fed-CNN-1D a Fed-CNN1D for activity recognition using air quality sensor dataset to address issues like latency, privacy, connectivity, and bandwidth with centralized learning. Our objective was to develop a robust private system capable of accurately detecting the type of activity based on gas sensor measurements of concentration collected from diverse indoor environments for clients, each local model trained on their own local private data to ensure the privacy preservation. By leveraging the power of the CNN-1D for local models and identifying the most accurate global model using FedAvg aggregation method in FL process. Fed-CNN-1D achieved 96.50% accuracy, 96.27% F1-Score, 96.54% Precision, 96.21% Recall, 0.11% Loss, and 15ms pred time, with a low communication cost of 0.099Mb. This study’s approach can significantly enhance air quality by providing real-time, privacy-preserving daily living activities detection, allowing systems to respond empathetically and improve smart building interaction.

References

- M. R. A. Berkani, A. Chouchane, Y. Himeur, A. Ouamane, and A. Amira, “An intelligent edge-deployable indoor air quality monitoring and activity recognition approach,” in 2023 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 184–189.

- P. Khaire and P. Kumar, “Deep learning and rgb-d based human action, human–human and human–object interaction recognition: A survey,” Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation, vol. 86, p. 103531, 2022.

- A. G. Salguero, J. Medina, P. Delatorre, and M. Espinilla, “Methodology for improving classification accuracy using ontologies: application in the recognition of activities of daily living,” Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing, vol. 10, pp. 2125–2142, 2019.

- A. Ouamane, A. Chouchane, Y. Himeur, A. Debilou, S. Nadji, N. Boubakeur, and A. Amira, “Enhancing plant disease detection: a novel cnn-based approach with tensor subspace learning and howsvd-mda,” Neural Computing and Applications, pp. 1–25, 2024.

- J. Maitre, K. Bouchard, C. Bertuglia, and S. Gaboury, “Recognizing activities of daily living from uwb radars and deep learning,” Expert Systems with Applications, vol. 164, p. 113994, 2021.

- M. Khammari, A. Chouchane, A. Ouamane, M. Bessaoudi et al., “Kinship verification using multiscale retinex preprocessing and integrated 2dswt-cnn features,” in 2024 8th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and their Applications (ISPA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- C. Ammar, B. Mebarka, O. Abdelmalik, and B. Salah, “Evaluation of histograms local features and dimensionality reduction for 3d face verification,” Journal of information processing systems, vol. 12, no. 3, pp. 468–488, 2016.

- A. Chouchane, A. Ouamane, Y. Himeur, W. Mansoor, S. Atalla, A. Benzaibak, and C. Boudellal, “Improving cnn-based person re-identification using score normalization,” in 2023 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 2890–2894.

- A. Chouchane, M. Bessaoudi, A. Ouamane, and O. Laouadi, “Face kinship verification based vgg16 and new gabor wavelet features,” in 2022 5th International Symposium on Informatics and its Applications (ISIA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6.

- A. Chouchane, M. Belahcene, A. Ouamane, and S. Bourennane, “3d face recognition based on histograms of local descriptors,” in 2014 4th International Conference on Image Processing Theory, Tools and Applications (IPTA). IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–5.

- Y. Himeur, I. Varlamis, H. Kheddar, A. Amira, S. Atalla, Y. Singh, F. Bensaali, and W. Mansoor, “Federated learning for computer vision,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.13558, 2023.

- P. Qi, D. Chiaro, A. Guzzo, M. Ianni, G. Fortino, and F. Piccialli, “Model aggregation techniques in federated learning: A comprehensive survey,” Future Generation Computer Systems, 2023.

- D. Połap, G. Srivastava, and A. Jaszcz, “Energy consumption prediction model for smart homes via decentralized federated learning with lstm,” IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics, 2023.

- Q. Wu, X. Chen, Z. Zhou, and J. Zhang, “Fedhome: Cloud-edge based personalized federated learning for in-home health monitoring,” IEEE Transactions on Mobile Computing, vol. 21, no. 8, pp. 2818–2832, 2020.

- R. A. Sater and A. B. Hamza, “A federated learning approach to anomaly detection in smart buildings,” ACM Transactions on Internet of Things, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 1–23, 2021.

- A. Chouchane, A. Ouamanea, Y. Himeur, A. Amira et al., “Deep learning-based leaf image analysis for tomato plant disease detection and classification,” in 2024 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP). IEEE, 2024, pp. 2923–2929.

- M. Khammari, A. Chouchane, M. Bessaoudi, A. Ouamane, Y. Himeur, S. Alallal, W. Mansoor et al., “Enhancing kinship verification through multiscale retinex and combined deep-shallow features,” in 2023 6th International Conference on Signal Processing and Information Security (ICSPIS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 178–183.

- M. Khammari, A. Chouchane, A. Ouamane, M. Bessaoudi, Y. Himeur, M. Hassaballah et al., “High-order knowledge-based discriminant features for kinship verification,” Pattern Recognition Letters, vol. 175, pp. 30–37, 2023.

- M. Rebiai, M. R. A. Berkani, M. Y. Bentegri, and M. T. Seghir, “Mathematical morphology-based envelope detection for cardiac disease classification from phonocardiogram signals,” in 2024 8th International Conference on Image and Signal Processing and their Applications (ISPA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–5.

- B. Bengherbia, M. R. A. Berkani, Z. Achir, A. Tobbal, M. Rebiai, and M. Maazouz, “Real-time smart system for ecg monitoring using a one-dimensional convolutional neural network,” in 2022 International Conference on Theoretical and Applied Computer Science and Engineering (ICTASCE). IEEE, 2022, pp. 32–37.

- M. Bessaoudi, M. Belahcene, A. Ouamane, A. Chouchane, and S. Bourennane, “A novel hybrid approach for 3d face recognition based on higher order tensor,” in Advances in Computing Systems and Applications: Proceedings of the 3rd Conference on Computing Systems and Applications 3. Springer, 2019, pp. 215–224.

- E. Gambi, G. Temperini, R. Galassi, L. Senigagliesi, and A. De Santis, “Adl recognition through machine learning algorithms on iot air quality sensor dataset,” IEEE Sensors Journal, vol. 20, no. 22, pp. 13 562–13 570, 2020.

- S. Srivatsan, S. K. Bamrah, and K. Gayathri, “An ensemble approach to recognize activities in smart environment using motion sensors and air quality sensors,” in Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics: Proceedings of ICDICI 2022. Springer, 2022, pp. 141–150.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).