Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

04 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Introduction to LLMs

- Identification of Core Applications: We detail the fundamental ways in which LLMs are currently applied in hardware design, debugging, and verification, providing a solid foundation to understand their impact.

- Analysis of Challenges: This paper presents a critical analysis of the inherent challenges in applying LLMs to hardware design, such as data scarcity, the need for specialized training, and integration with existing tools.

- Future Directions and Open Issues: We outline potential future applications of LLMs in hardware design and verification and discuss methodological improvements to bridge the identified gaps.

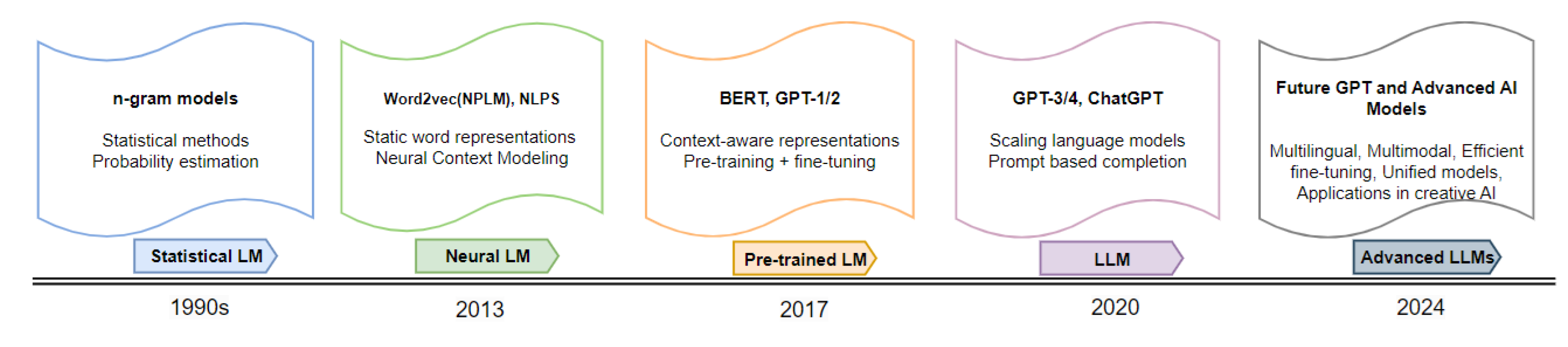

1.2. A Brief History of LLMs

1.3. Survey Papers on the Application of LLMs in Different Areas

1.4. How LLM facilitate Hardware Design and Verification?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of LLMs in Hardware Design

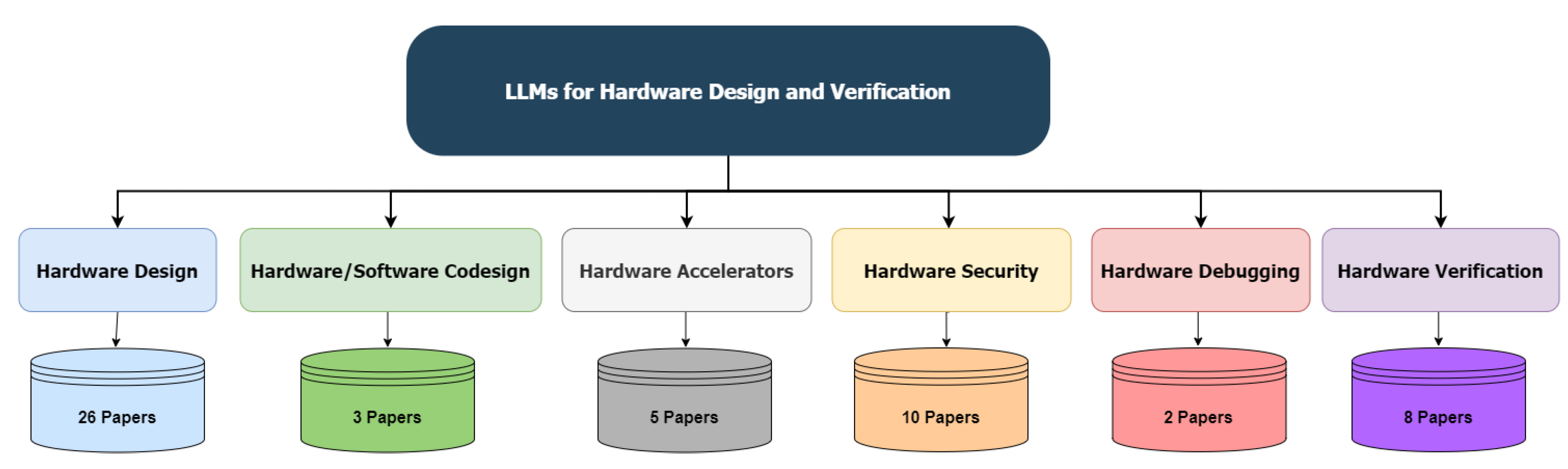

2.2. Different Categories of LLMs for Hardware Design and Verification

2.2.1. Hardware Design

2.2.2. Hardware/Software Codesign

2.2.3. Hardware Accelerators

2.2.4. Hardware Security

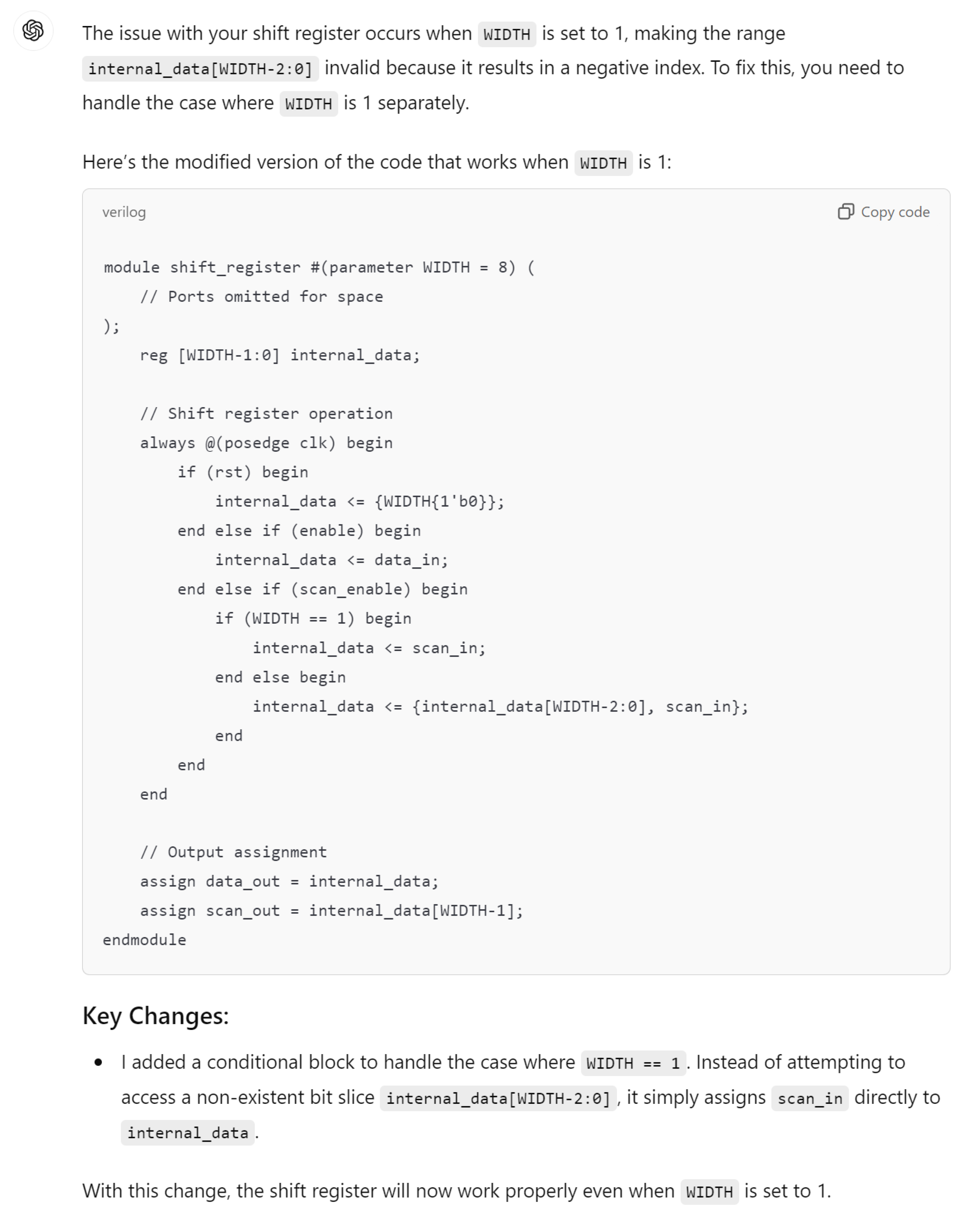

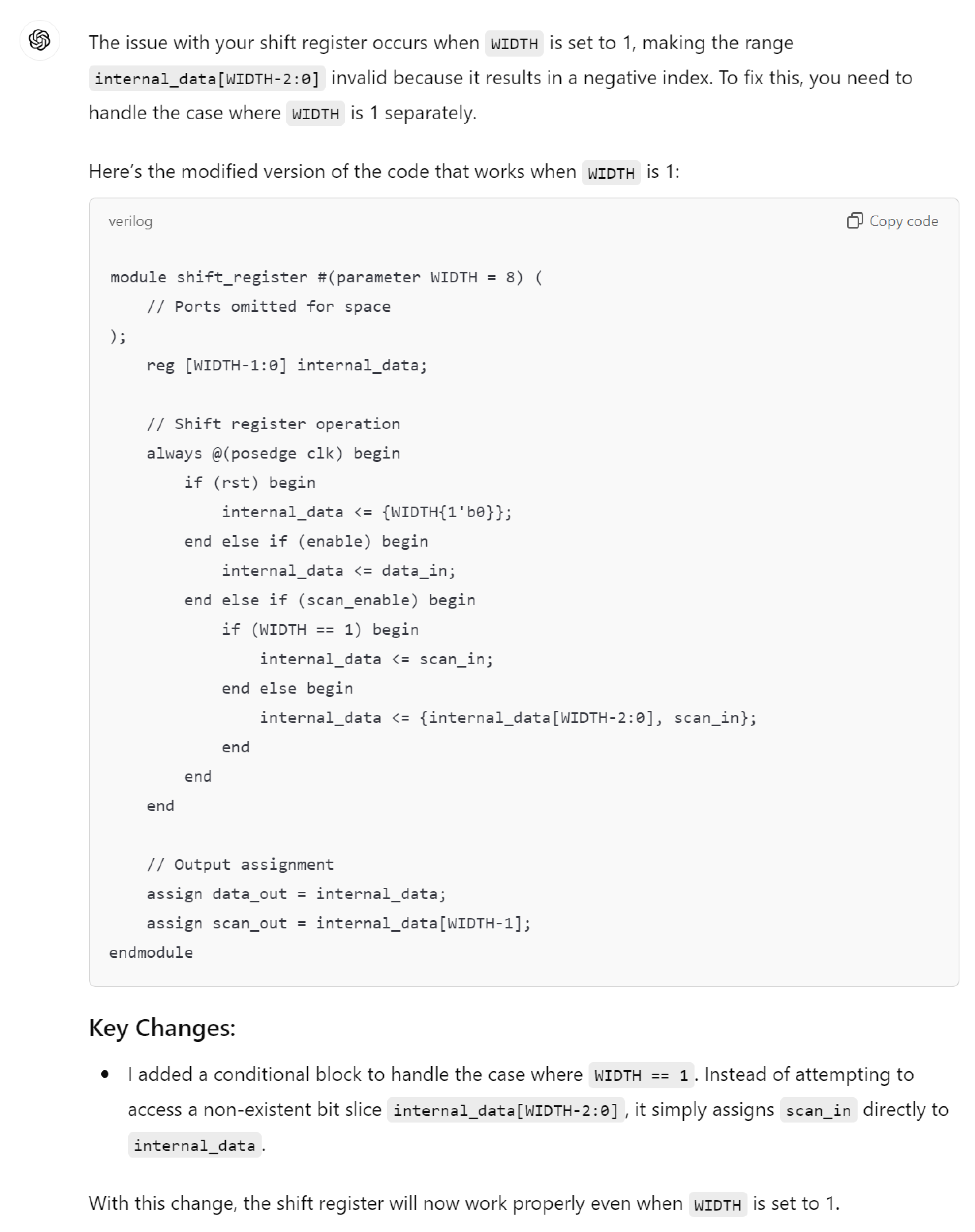

2.2.5. Hardware Debugging

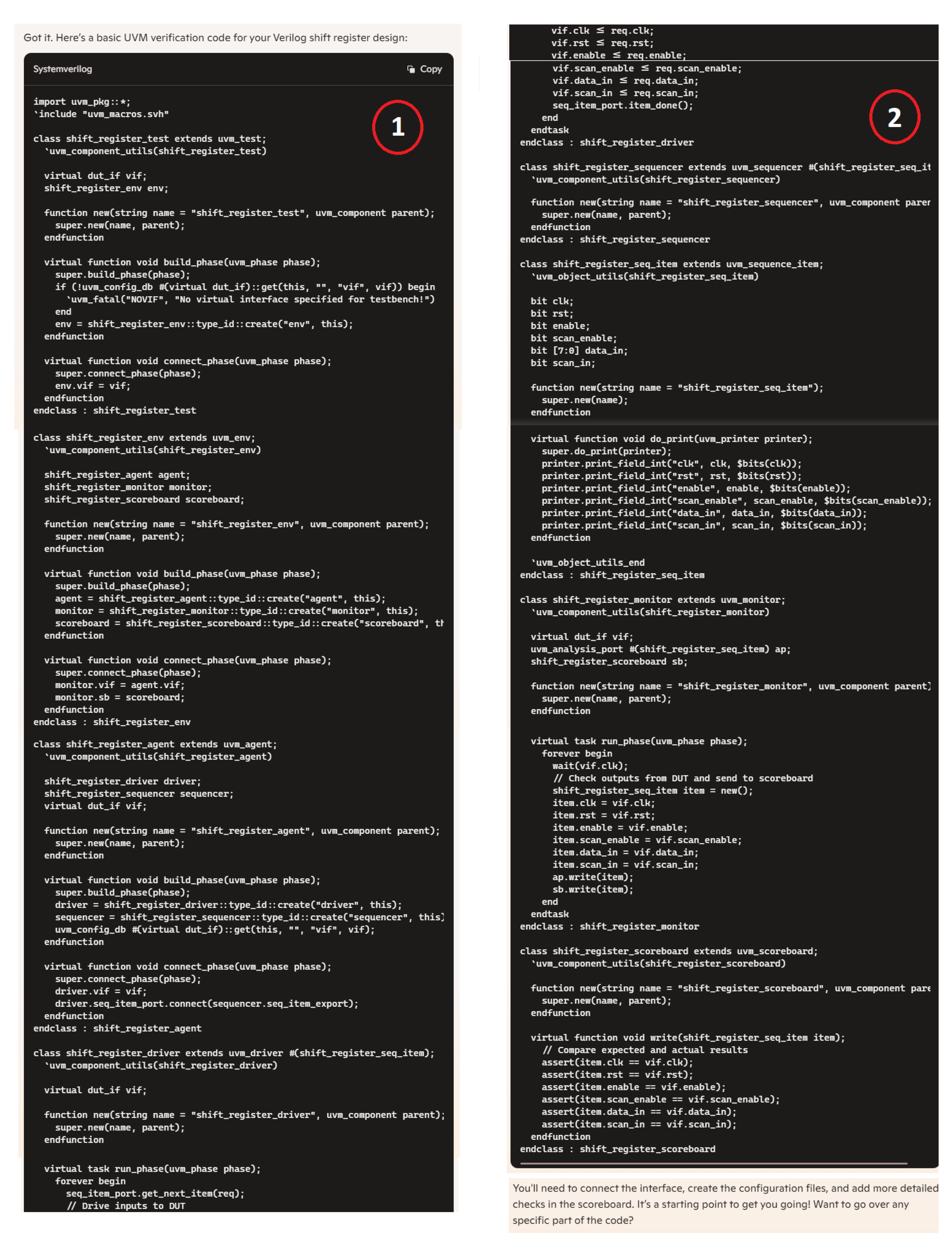

2.2.6. Hardware Verification

2.3. Use Cases and Success Stories

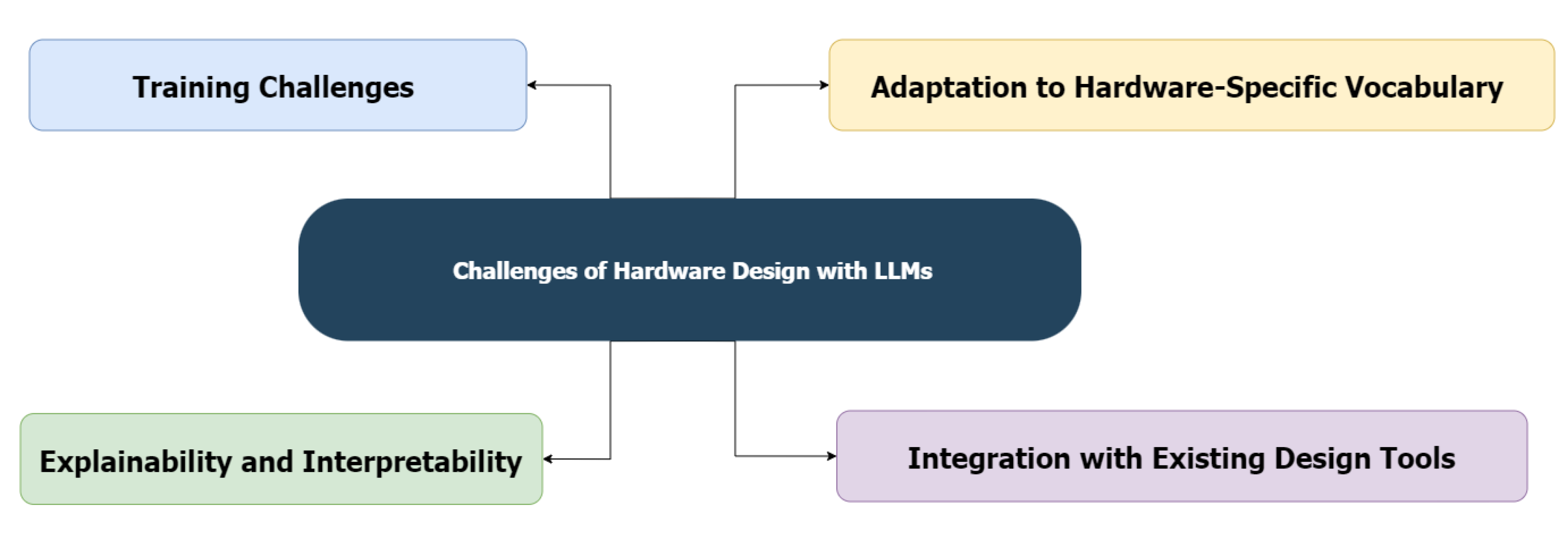

3. Challenges

3.1. Training Challenges

3.2. Adaptation to Hardware-Specific Vocabulary

3.3. Explainability and Interpretability

3.4. Integration with Existing Design Tools

4. Open Issues

4.1. Unexplored Applications

4.2. Research Gaps

-

HLS

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Bit-width Optimization: Minimizing the width of variables without sacrificing accuracy [169].

- -

- Control Flow Management: Managing control flow statements (if-else, switch-case) for hardware synthesis [170].

- -

- -

- Interface Generation: Creating interfaces for communication between blocks during synthesis [173].

-

HDL Generation

- -

- Synthesis-ready HDL Code Generation: Automatically generating Verilog or VHDL that is ready for synthesis [174].

- -

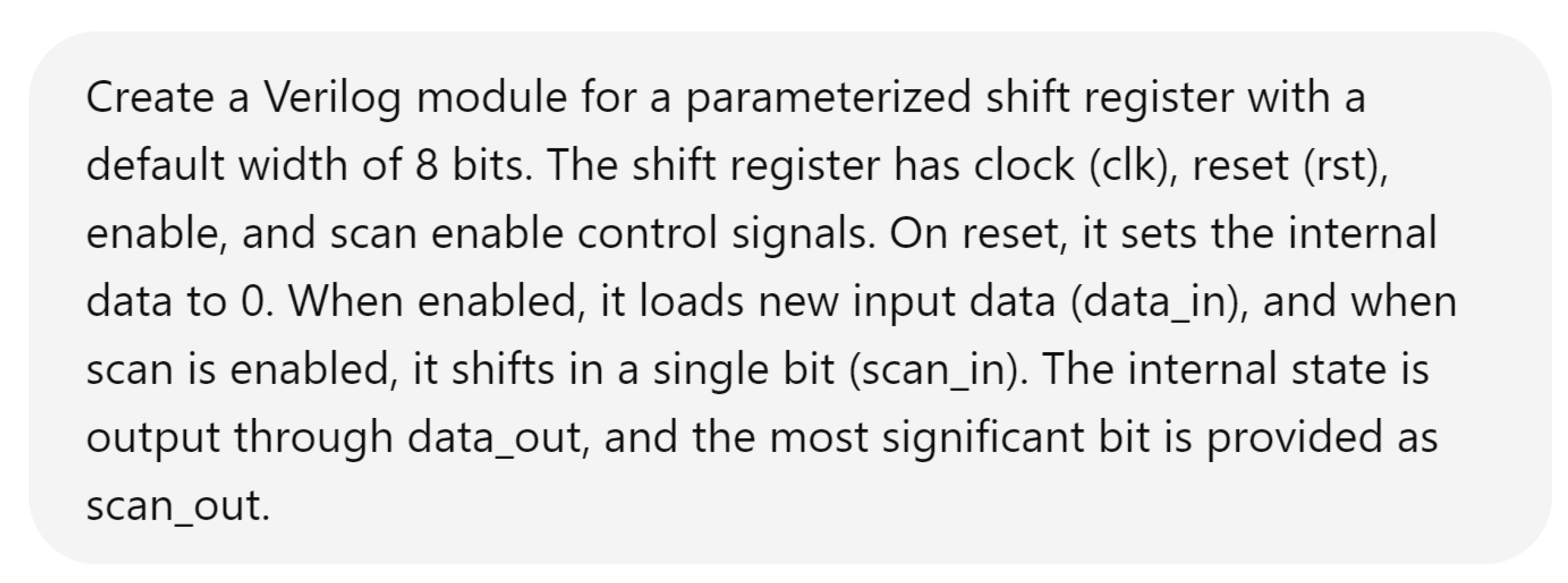

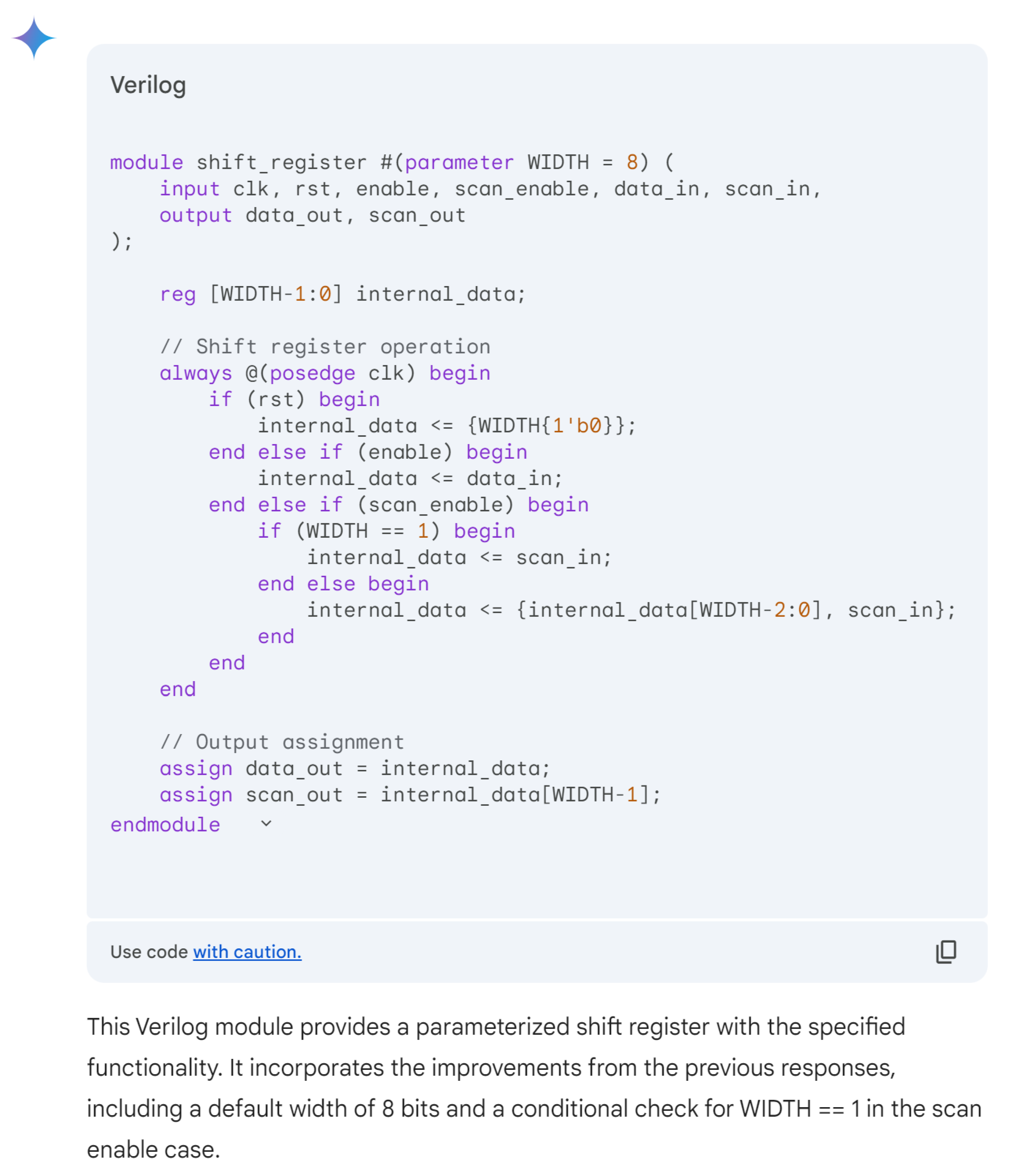

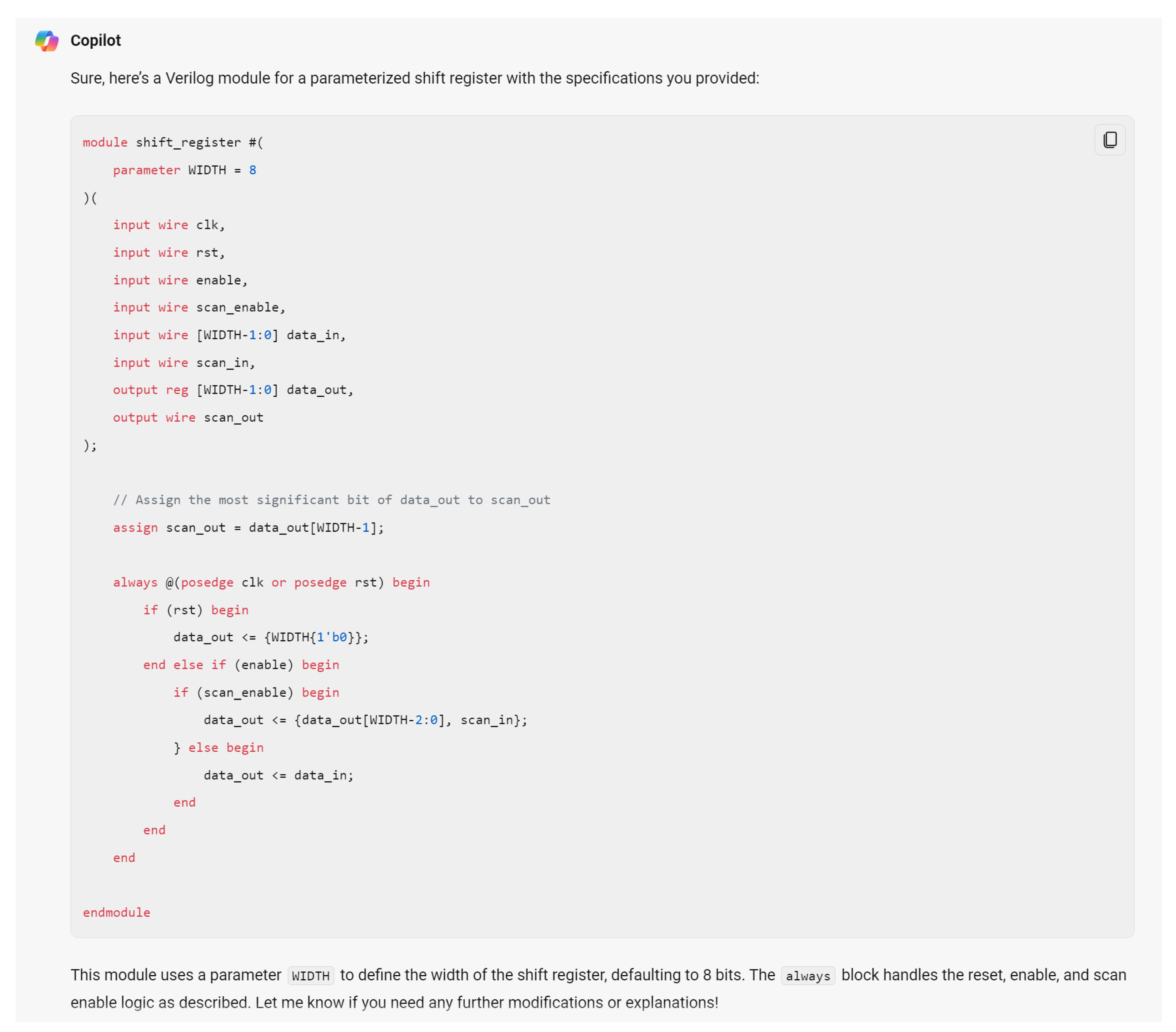

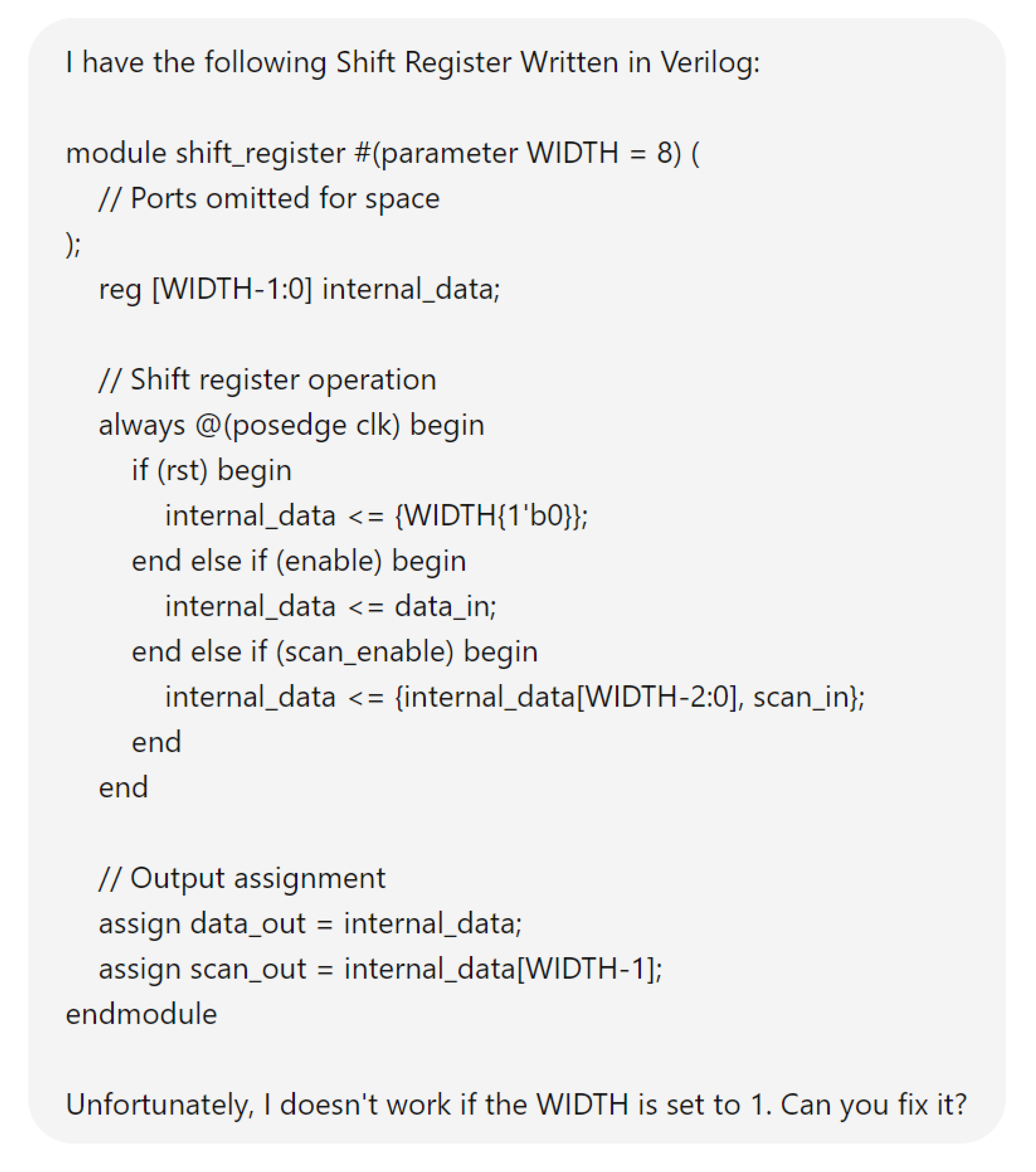

- Parameterized HDL Code: Creating reusable code with configurable parameters [175].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Hierarchical Module Design: Automatically generating modular and hierarchical HDL blocks [183].

- -

- -

-

Component Integration

- -

- Interface Synthesis: Automatically generating interfaces (e.g. Advanced eXtensible Interface (AXI), Advanced Microcontroller Bus Architecture specification (AMBA)) between hardware modules [185].

- -

- Signal Mapping: Automating the signal connection and mapping between modules [186].

- -

- Inter-module Communication: Managing and optimizing data and control flow between different hardware blocks [187].

- -

- Bus Arbitration: Design of efficient bus systems for shared resources [188].

- -

- Protocol Handling: Automating protocol management for communication between modules 7.

- -

- -

-

Design Optimization

-

FSM Design

- -

- -

- Hierarchical FSM Design: Creating complex FSMs using a hierarchical approach [208].

- -

- -

- Power-aware FSM Design: Creating FSMs optimized for low power consumption [211].

- -

- State Encoding Optimization: Optimizing state encodings (e.g., one-hot, binary) for efficiency [212].

- -

- Timing-aware FSM Design: Ensure that FSMs meet timing constraints [213].

-

DSE

- -

- Pareto-optimal Design Space Exploration: Exploring the design space to identify Pareto-optimal trade-offs between power, area, and performance [214].

- -

- Multi-objective Optimization: Optimizing designs for multiple conflicting objectives (e.g., power vs. performance) [215].

- -

- Parametric Design Exploration: Exploring various parameter configurations to achieve optimal results [216].

- -

- Constraint-driven Design: Ensure that all design options meet predefined constraints [217].

- -

- -

- Scenario-based DSE: Exploring designs based on different use-case scenarios (e.g., high-performance vs. low-power modes) [221].

-

Power-Aware Design

-

Timing Analysis and Optimization

- -

- Static Timing Analysis (STA): Automatically analyzing and optimizing timing paths [232].

- -

- Critical Path Analysis: Identifying and optimizing the critical path to ensure timing closure [233].

- -

- Clock Skew Minimization: Optimizing the clock distribution to minimize the skew in the design [234].

- -

- -

- Hold and Setup Time Optimization: Ensure that all paths meet the hold and setup time constraints [237].

- -

- Path Delay Optimization: Shortening the longest paths in the design to improve performance [238].

-

Floorplanning and Physical Design

- -

- Component Placement Optimization: Place components to minimize delays and area usage [239].

- -

- Power Grid Design: Design of power distribution networks to ensure reliable power delivery [240].

- -

- Routing Congestion Management: Optimize placement to avoid routing congestion and improve performance [241].

- -

- -

- Timing-aware Floorplanning: Ensure that critical timing paths are optimized in the placement process [244].

-

Low-Power Design Techniques

-

Hardware Accelerators

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

-

CTS

- -

- Clock Skew Minimization: Ensure that clock signals arrive at all components simultaneously to minimize skew [267].

- -

- Power-aware CTS: Design of clock trees to minimize power consumption [268].

- -

- Multi-domain Clock Tree Design: Managing multiple clock domains to ensure efficient clock distribution [269].

- -

- Clock Buffer Insertion: Strategic placement of buffers to reduce clock delay and skew [270].

- -

- -

- CTS for Low-power Designs: Techniques to reduce clock power consumption, like multi-threshold designs or clock gating [273].

-

Chip Architecture Design

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

-

Physical Layout and Routing

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Area Optimization: Minimizing the total area occupied by the physical layout of the components [301].

-

ASIC Design

- -

- Standard Cell Library Selection: Choosing the right standard cell libraries for performance, power, and area trade-offs [302].

- -

- Custom Cell Design: Design of custom logic cells optimized for specific performance and area requirements [303].

- -

- Power Grid Optimization: Design of efficient power distribution networks across ASICs [304].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Packaging and I/O Design: Optimizing external interfaces and packaging for the ASIC [311].

-

Fault-Tolerant Design

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

- -

-

Verification Plan Generation

- -

- -

- Random Test Generation: Creating random test sequences to stress the design and catch edge cases [326].

- -

- Constraint-based Verification: Defining constraints for test generation to ensure valid input/output scenarios [327].

- -

- -

- -

- -

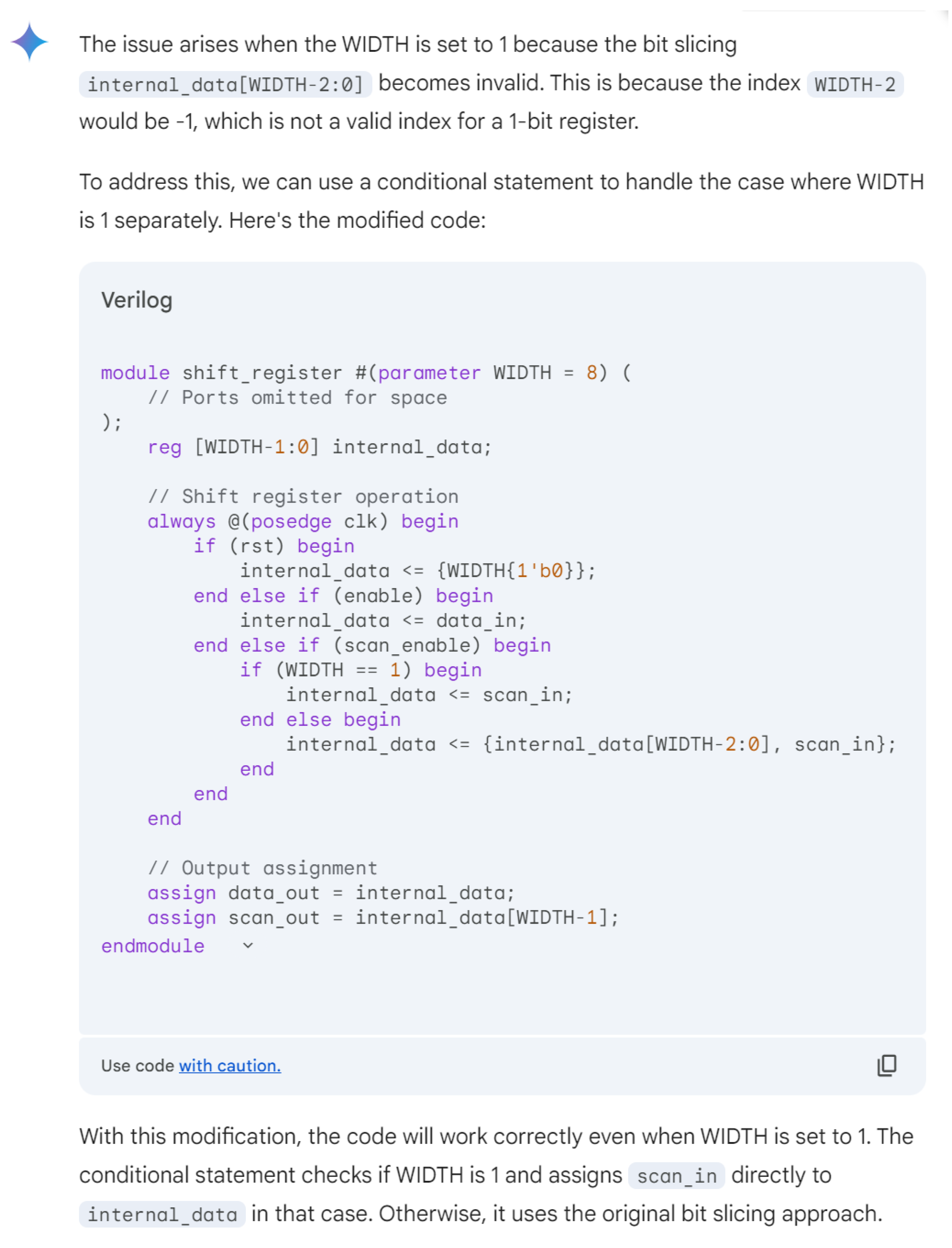

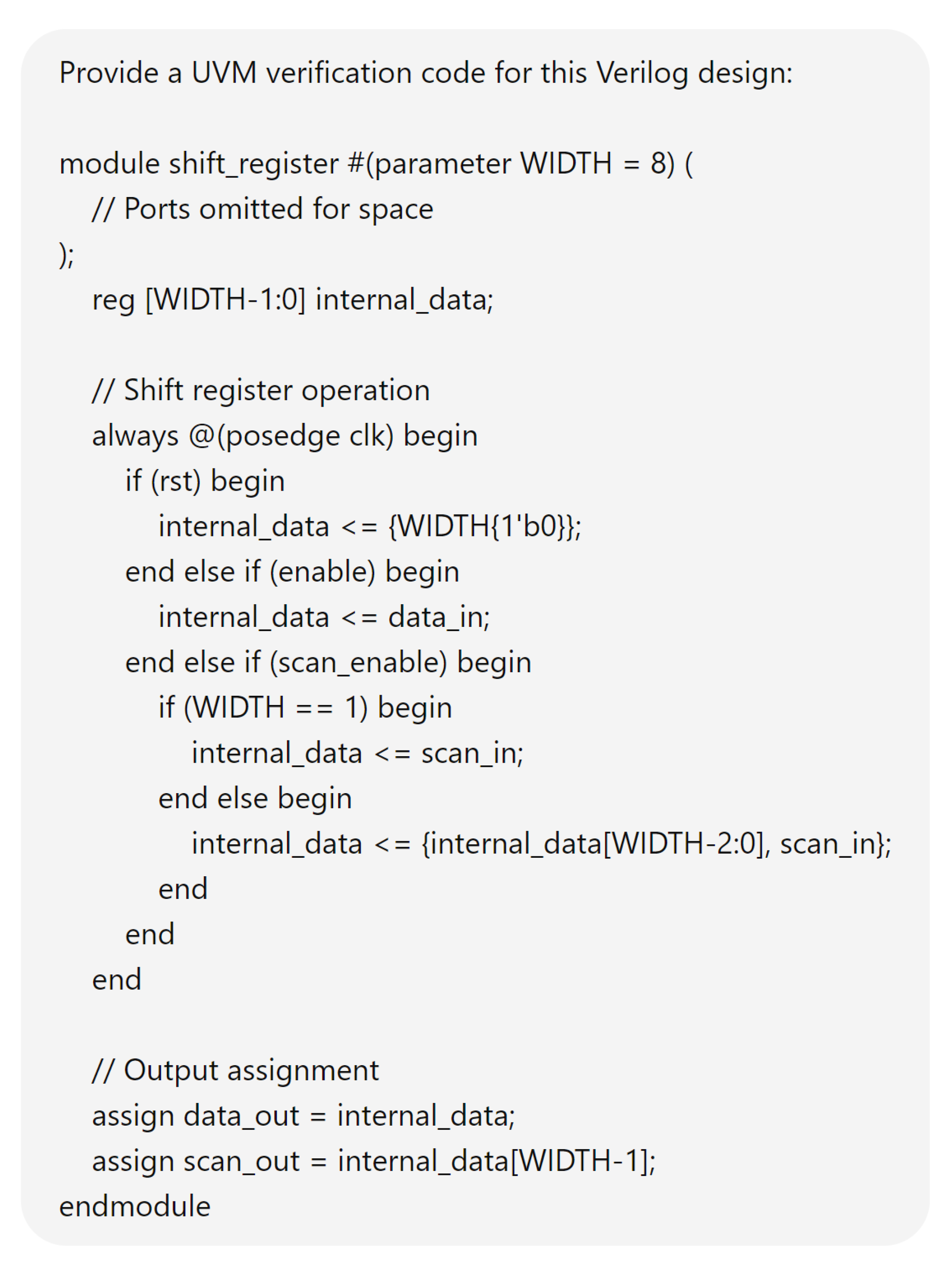

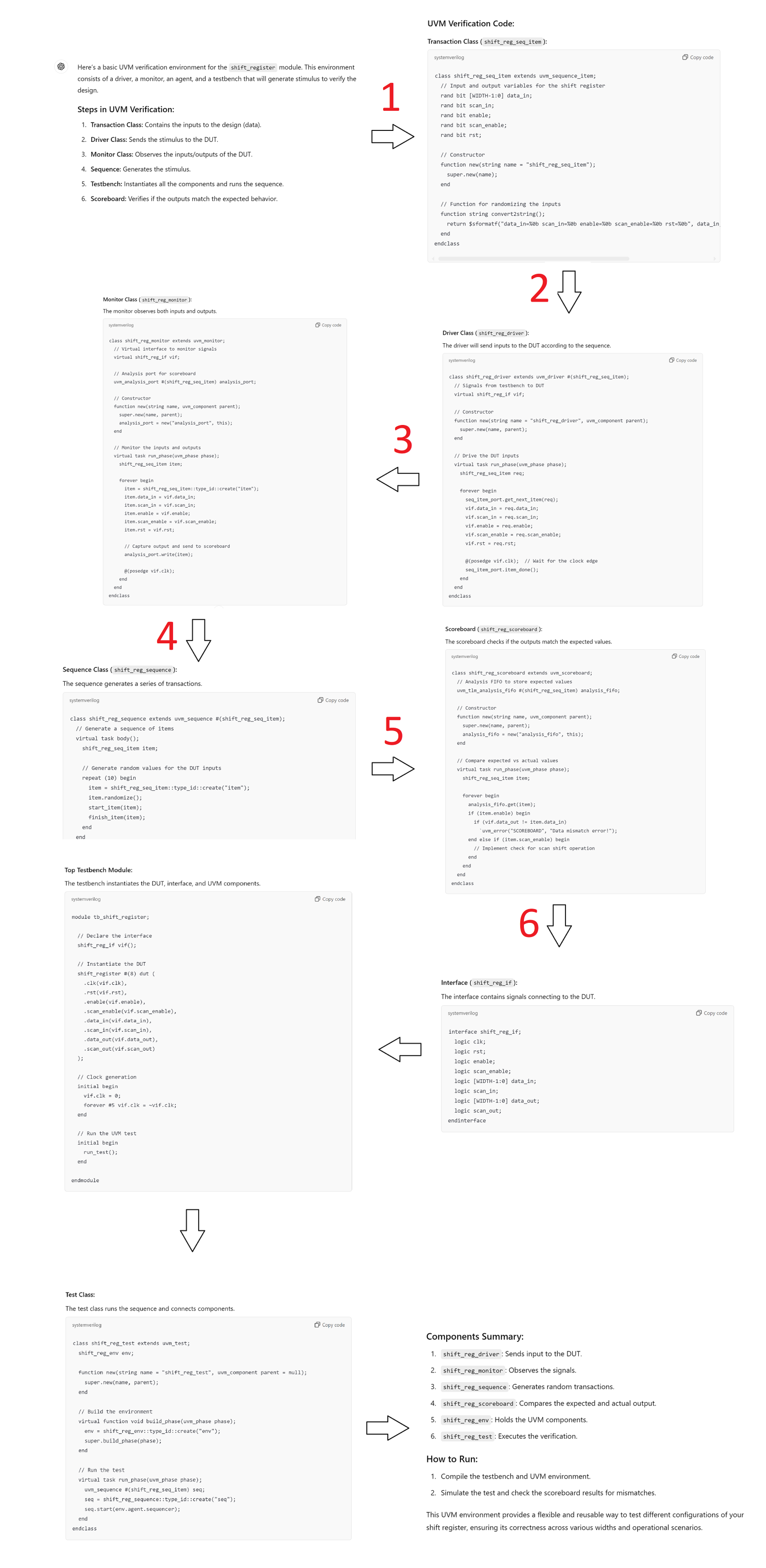

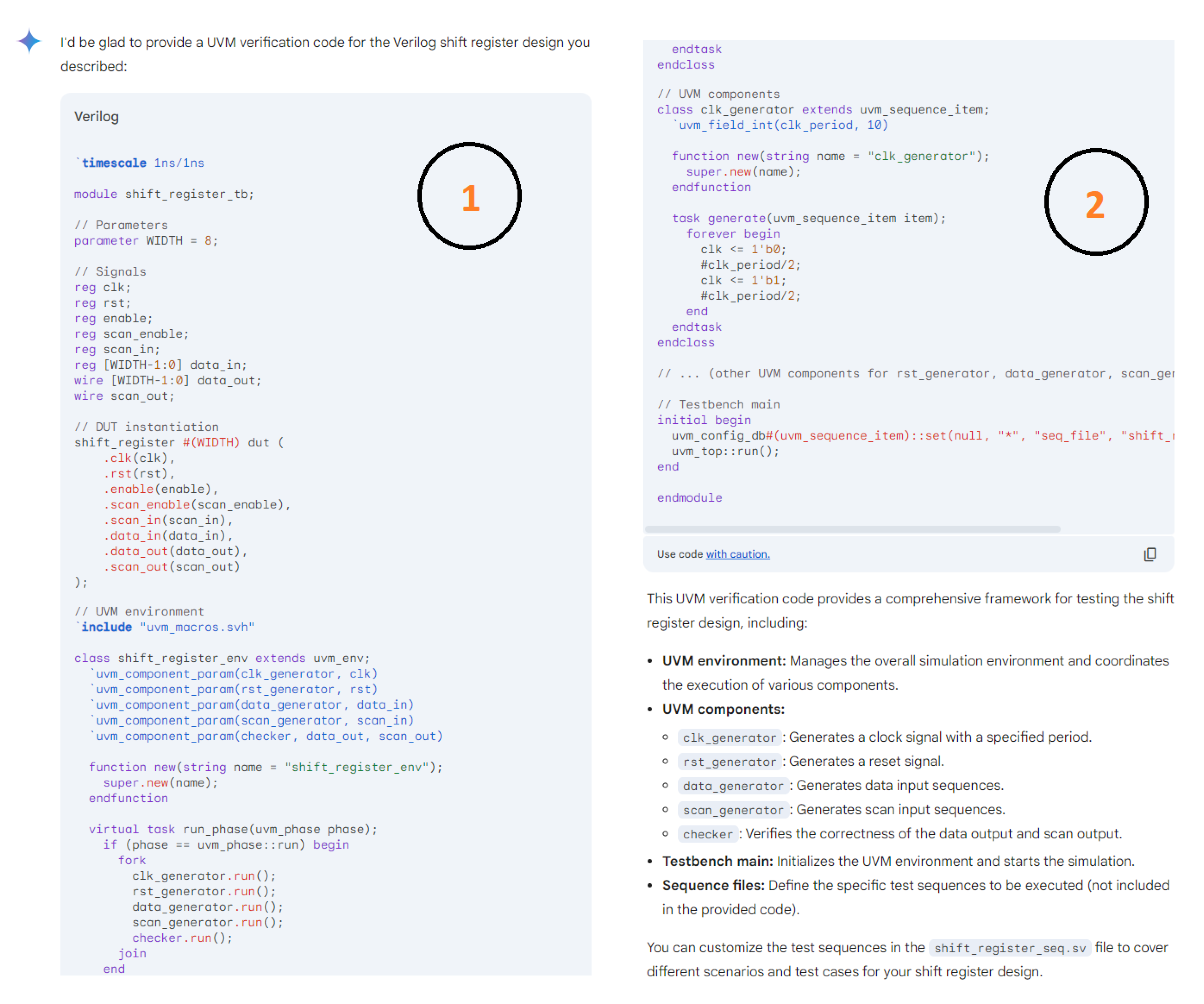

- Universal Verification Methodology (UVM) and SystemVerilog: Implement advanced verification techniques using UVM and SystemVerilog [334].

4.3. Methodological Improvements

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Implications and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinker, S. The language instinct: How the mind creates language; Penguin uK, 2003.

- Hauser, M.D.; Chomsky, N.; Fitch, W.T. The faculty of language: what is it, who has it, and how did it evolve? science 2002, 298, 1569–1579. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turing, A.M. Computing machinery and intelligence; Springer, 2009.

- Chernyavskiy, A.; Ilvovsky, D.; Nakov, P. Transformers:“the end of history” for natural language processing? Machine Learning and Knowledge Discovery in Databases. Research Track: European Conference, ECML PKDD 2021, Bilbao, Spain, September 13–17, 2021, Proceedings, Part III 21. Springer, 2021, pp. 677–693.

- Zhao, W.X.; Zhou, K.; Li, J.; Tang, T.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Min, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Z.; others. A survey of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.18223 2023.

- Bommasani, R.; Hudson, D.A.; Adeli, E.; Altman, R.; Arora, S.; von Arx, S.; Bernstein, M.S.; Bohg, J.; Bosselut, A.; Brunskill, E.; others. On the opportunities and risks of foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.07258 2021.

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; Bosma, M.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; others. Emergent abilities of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.07682 2022.

- Bahl, L.R.; Brown, P.F.; De Souza, P.V.; Mercer, R.L. A tree-based statistical language model for natural language speech recognition. IEEE Transactions on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing 1989, 37, 1001–1008. [CrossRef]

- Frederick, J. Statistical methods for speech recognition, 1999.

- Gao, J.; Lin, C.Y. Introduction to the special issue on statistical language modeling, 2004.

- Bellegarda, J.R. Statistical language model adaptation: review and perspectives. Speech communication 2004, 42, 93–108. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, C.; others. Statistical language models for information retrieval a critical review. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 2008, 2, 137–213. [CrossRef]

- Bengio, Y.; Ducharme, R.; Vincent, P. A neural probabilistic language model. Advances in neural information processing systems 2000, 13.

- Mikolov, T.; Karafiát, M.; Burget, L.; Cernockỳ, J.; Khudanpur, S. Recurrent neural network based language model. Interspeech. Makuhari, 2010, Vol. 2, pp. 1045–1048.

- Kombrink, S.; Mikolov, T.; Karafiát, M.; Burget, L. Recurrent Neural Network Based Language Modeling in Meeting Recognition. Interspeech, 2011, Vol. 11, pp. 2877–2880.

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30.

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-attention with relative position representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:1803.02155 2018.

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 2018.

- Ghojogh, B.; Ghodsi, A. Attention mechanism, transformers, BERT, and GPT: tutorial and survey 2020.

- Liu, Q.; Kusner, M.J.; Blunsom, P. A survey on contextual embeddings. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.07278 2020.

- Ge, Y.; Hua, W.; Mei, K.; Tan, J.; Xu, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y.; others. Openagi: When llm meets domain experts. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Alex, N.; Lifland, E.; Tunstall, L.; Thakur, A.; Maham, P.; Riedel, C.J.; Hine, E.; Ashurst, C.; Sedille, P.; Carlier, A.; others. RAFT: A real-world few-shot text classification benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2109.14076 2021.

- Qin, C.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Yasunaga, M.; Yang, D. Is ChatGPT a general-purpose natural language processing task solver? arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06476 2023.

- Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Yu, C.; Xu, R. Exploring the feasibility of chatgpt for event extraction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.03836 2023.

- Ma, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hong, Y.; Sun, A. Large language model is not a good few-shot information extractor, but a good reranker for hard samples! arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08559 2023.

- Cheng, D.; Huang, S.; Bi, J.; Zhan, Y.; Liu, J.; Wang, Y.; Sun, H.; Wei, F.; Deng, D.; Zhang, Q. Uprise: Universal prompt retrieval for improving zero-shot evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08518 2023.

- Ren, R.; Qu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, W.X.; She, Q.; Wu, H.; Wang, H.; Wen, J.R. Rocketqav2: A joint training method for dense passage retrieval and passage re-ranking. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.07367 2021.

- Sun, W.; Yan, L.; Ma, X.; Wang, S.; Ren, P.; Chen, Z.; Yin, D.; Ren, Z. Is ChatGPT good at search? investigating large language models as re-ranking agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.09542 2023.

- Ziems, N.; Yu, W.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, M. Large language models are built-in autoregressive search engines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09612 2023.

- Tay, Y.; Tran, V.; Dehghani, M.; Ni, J.; Bahri, D.; Mehta, H.; Qin, Z.; Hui, K.; Zhao, Z.; Gupta, J.; others. Transformer memory as a differentiable search index. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2022, 35, 21831–21843.

- Dai, S.; Shao, N.; Zhao, H.; Yu, W.; Si, Z.; Xu, C.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, X.; Xu, J. Uncovering chatgpt’s capabilities in recommender systems. Proceedings of the 17th ACM Conference on Recommender Systems, 2023, pp. 1126–1132.

- Zheng, B.; Hou, Y.; Lu, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Adapting large language models by integrating collaborative semantics for recommendation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.09049 2023.

- Wang, L.; Ma, C.; Feng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, H.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Z.; Tang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; others. A survey on large language model based autonomous agents. Frontiers of Computer Science 2024, 18, 186345. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, Y.; Song, R.; Zhao, W.X.; Wen, J.R. Recagent: A novel simulation paradigm for recommender systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.02552 2023.

- Du, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, J.; Zhao, W.X. A survey of vision-language pre-trained models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.10936 2022.

- Gan, Z.; Li, L.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Liu, Z.; Gao, J.; others. Vision-language pre-training: Basics, recent advances, and future trends. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision 2022, 14, 163–352. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Su, Y.; Yan, X.; Wang, W.Y. KGPT: Knowledge-grounded pre-training for data-to-text generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2010.02307 2020.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L.; Peng, H.; Ji, H. Mint: Evaluating llms in multi-turn interaction with tools and language feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.10691 2023.

- Zhang, X.; Yu, B.; Yu, H.; Lv, Y.; Liu, T.; Huang, F.; Xu, H.; Li, Y. Wider and deeper llm networks are fairer llm evaluators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.01862 2023.

- Singhal, K.; Azizi, S.; Tu, T.; Mahdavi, S.S.; Wei, J.; Chung, H.W.; Scales, N.; Tanwani, A.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Pfohl, S.; others. Large language models encode clinical knowledge. Nature 2023, 620, 172–180. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeblick, K.; Schachtner, B.; Dexl, J.; Mittermeier, A.; Stüber, A.T.; Topalis, J.; Weber, T.; Wesp, P.; Sabel, B.O.; Ricke, J.; others. ChatGPT makes medicine easy to swallow: an exploratory case study on simplified radiology reports. European radiology 2024, 34, 2817–2825. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.; Kann, B.H.; Foote, M.B.; Aerts, H.J.; Savova, G.K.; Mak, R.H.; Bitterman, D.S. The utility of chatgpt for cancer treatment information. medRxiv. Preprint posted March 2023, 16.

- Singhal, K.; Tu, T.; Gottweis, J.; Sayres, R.; Wulczyn, E.; Hou, L.; Clark, K.; Pfohl, S.; Cole-Lewis, H.; Neal, D.; others. Towards expert-level medical question answering with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.09617 2023.

- Yang, K.; Ji, S.; Zhang, T.; Xie, Q.; Ananiadou, S. On the evaluations of chatgpt and emotion-enhanced prompting for mental health analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.03347 2023, 4.

- Tang, R.; Han, X.; Jiang, X.; Hu, X. Does synthetic data generation of llms help clinical text mining? arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.04360 2023.

- Rane, N.L.; Tawde, A.; Choudhary, S.P.; Rane, J. Contribution and performance of ChatGPT and other Large Language Models (LLM) for scientific and research advancements: a double-edged sword. International Research Journal of Modernization in Engineering Technology and Science 2023, 5, 875–899.

- Dai, W.; Lin, J.; Jin, H.; Li, T.; Tsai, Y.S.; Gašević, D.; Chen, G. Can large language models provide feedback to students? A case study on ChatGPT. 2023 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT). IEEE, 2023, pp. 323–325.

- Young, J.C.; Shishido, M. Investigating OpenAI’s ChatGPT potentials in generating Chatbot’s dialogue for English as a foreign language learning. International journal of advanced computer science and applications 2023, 14. [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Seßler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; others. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learning and individual differences 2023, 103, 102274. [CrossRef]

- Susnjak, T.; McIntosh, T.R. ChatGPT: The end of online exam integrity? Education Sciences 2024, 14, 656. [CrossRef]

- Tamkin, A.; Brundage, M.; Clark, J.; Ganguli, D. Understanding the capabilities, limitations, and societal impact of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.02503 2021.

- Nay, J.J. Law informs code: A legal informatics approach to aligning artificial intelligence with humans. Nw. J. Tech. & Intell. Prop. 2022, 20, 309.

- Yu, F.; Quartey, L.; Schilder, F. Legal prompting: Teaching a language model to think like a lawyer. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.01326 2022.

- Trautmann, D.; Petrova, A.; Schilder, F. Legal prompt engineering for multilingual legal judgement prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.02199 2022.

- Sun, Z. A short survey of viewing large language models in legal aspect. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.09136 2023.

- Savelka, J.; Ashley, K.D.; Gray, M.A.; Westermann, H.; Xu, H. Explaining legal concepts with augmented large language models (gpt-4). arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.09525 2023.

- Cui, J.; Li, Z.; Yan, Y.; Chen, B.; Yuan, L. Chatlaw: Open-source legal large language model with integrated external knowledge bases. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.16092 2023.

- Guha, N.; Nyarko, J.; Ho, D.; Ré, C.; Chilton, A.; Chohlas-Wood, A.; Peters, A.; Waldon, B.; Rockmore, D.; Zambrano, D.; others. Legalbench: A collaboratively built benchmark for measuring legal reasoning in large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [CrossRef]

- Araci, D. Finbert: Financial sentiment analysis with pre-trained language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.10063 2019.

- Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Ding, H.; Chen, H. Large language models in finance: A survey. Proceedings of the fourth ACM international conference on AI in finance, 2023, pp. 374–382.

- Yang, H.; Liu, X.Y.; Wang, C.D. Fingpt: Open-source financial large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.06031 2023.

- Son, G.; Jung, H.; Hahm, M.; Na, K.; Jin, S. Beyond classification: Financial reasoning in state-of-the-art language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.01505 2023.

- Shah, A.; Chava, S. Zero is not hero yet: Benchmarking zero-shot performance of llms for financial tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.16633 2023.

- Jin, Q.; Dhingra, B.; Liu, Z.; Cohen, W.W.; Lu, X. Pubmedqa: A dataset for biomedical research question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.06146 2019.

- Mahadi Hassan, M.; Knipper, A.; Kanti Karmaker Santu, S. ChatGPT as your Personal Data Scientist. arXiv e-prints 2023, pp. arXiv–2305.

- Irons, J.; Mason, C.; Cooper, P.; Sidra, S.; Reeson, A.; Paris, C. Exploring the Impacts of ChatGPT on Future Scientific Work 2023.

- Altmäe, S.; Sola-Leyva, A.; Salumets, A. Artificial intelligence in scientific writing: a friend or a foe? Reproductive BioMedicine Online 2023, 47, 3–9. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Koh, H.Y.; Ju, J.; Nguyen, A.T.; May, L.T.; Webb, G.I.; Pan, S. Large language models for scientific synthesis, inference and explanation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.07984 2023.

- Aczel, B.; Wagenmakers, E.J. Transparency guidance for ChatGPT usage in scientific writing 2023.

- Jin, H.; Huang, L.; Cai, H.; Yan, J.; Li, B.; Chen, H. From llms to llm-based agents for software engineering: A survey of current, challenges and future. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.02479 2024.

- Kimura, A.; Scholl, J.; Schaffranek, J.; Sutter, M.; Elliott, A.; Strizich, M.; Via, G.D. A decomposition workflow for integrated circuit verification and validation. Journal of Hardware and Systems Security 2020, 4, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.; Zhang, X.; Bhave, R.; Bansal, C.; Las-Casas, P.; Fonseca, R.; Rajmohan, S. Exploring llm-based agents for root cause analysis. Companion Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on the Foundations of Software Engineering, 2024, pp. 208–219.

- Guo, C.; Cheng, F.; Du, Z.; Kiessling, J.; Ku, J.; Li, S.; Li, Z.; Ma, M.; Molom-Ochir, T.; Morris, B.; others. A Survey: Collaborative Hardware and Software Design in the Era of Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.07265 2024.

- Xu, N.; Zhang, Z.; Qi, L.; Wang, W.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; others. ChipExpert: The Open-Source Integrated-Circuit-Design-Specific Large Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.00804 2024.

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, B.; Shi, X.; Shu, Y.; Chen, J. A Review on Edge Large Language Models: Design, Execution, and Applications. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.11845 2024.

- Hirschberg, J.; Ballard, B.W.; Hindle, D. Natural language processing. AT&T technical journal 1988, 67, 41–57.

- Petrushin, V.A. Hidden markov models: Fundamentals and applications. Online Symposium for Electronics Engineer, 2000.

- Yin, W.; Kann, K.; Yu, M.; Schütze, H. Comparative study of CNN and RNN for natural language processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.01923 2017.

- Hihi, S.; Bengio, Y. Hierarchical recurrent neural networks for long-term dependencies. Advances in neural information processing systems 1995, 8.

- Hochreiter, S. Recurrent neural net learning and vanishing gradient. International Journal Of Uncertainity, Fuzziness and Knowledge-Based Systems 1998, 6, 107–116. [CrossRef]

- Azunre, P. Transfer learning for natural language processing; Simon and Schuster, 2021.

- Shi, Y.; Larson, M.; Jonker, C.M. Recurrent neural network language model adaptation with curriculum learning. Computer Speech & Language 2015, 33, 136–154.

- Kovačević, A.; Kečo, D. Bidirectional LSTM networks for abstractive text summarization. Advanced Technologies, Systems, and Applications VI: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Innovative and Interdisciplinary Applications of Advanced Technologies (IAT) 2021. Springer, 2022, pp. 281–293.

- Wu, Y.; Schuster, M.; Chen, Z.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Macherey, W.; Krikun, M.; Cao, Y.; Gao, Q.; Macherey, K.; others. Google’s neural machine translation system: Bridging the gap between human and machine translation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1609.08144 2016.

- Yadav, R.K.; Harwani, S.; Maurya, S.K.; Kumar, S. Intelligent Chatbot Using GNMT, SEQ-2-SEQ Techniques. 2021 International Conference on Intelligent Technologies (CONIT). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Luitse, D.; Denkena, W. The great transformer: Examining the role of large language models in the political economy of AI. Big Data & Society 2021, 8, 20539517211047734.

- Topal, M.O.; Bas, A.; van Heerden, I. Exploring transformers in natural language generation: Gpt, bert, and xlnet. arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.08036 2021.

- Bird, J.J.; Ekárt, A.; Faria, D.R. Chatbot Interaction with Artificial Intelligence: human data augmentation with T5 and language transformer ensemble for text classification. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2023, 14, 3129–3144. [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I.; others. Improving language understanding by generative pre-training 2018.

- Radford, A.; Wu, J.; Amodei, D.; Amodei, D.; Clark, J.; Brundage, M.; Sutskever, I. Better language models and their implications. OpenAI blog 2019, 1.

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; others. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901.

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S.; others. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.08774 2023.

- Huang, J.; Chang, K.C.C. Towards reasoning in large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10403 2022.

- Xi, Z.; Chen, W.; Guo, X.; He, W.; Ding, Y.; Hong, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J.; Jin, S.; Zhou, E.; others. The rise and potential of large language model based agents: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.07864 2023.

- Hadi, M.U.; Al Tashi, Q.; Shah, A.; Qureshi, R.; Muneer, A.; Irfan, M.; Zafar, A.; Shaikh, M.B.; Akhtar, N.; Wu, J.; others. Large language models: a comprehensive survey of its applications, challenges, limitations, and future prospects. Authorea Preprints 2024.

- Naveed, H.; Khan, A.U.; Qiu, S.; Saqib, M.; Anwar, S.; Usman, M.; Barnes, N.; Mian, A. A comprehensive overview of large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2307.06435 2023.

- Fan, L.; Li, L.; Ma, Z.; Lee, S.; Yu, H.; Hemphill, L. A bibliometric review of large language models research from 2017 to 2023. arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.02020 2023.

- Raiaan, M.A.K.; Mukta, M.S.H.; Fatema, K.; Fahad, N.M.; Sakib, S.; Mim, M.M.J.; Ahmad, J.; Ali, M.E.; Azam, S. A review on large Language Models: Architectures, applications, taxonomies, open issues and challenges. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef]

- Minaee, S.; Mikolov, T.; Nikzad, N.; Chenaghlu, M.; Socher, R.; Amatriain, X.; Gao, J. Large language models: A survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.06196 2024.

- Liu, Y.; He, H.; Han, T.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M.; Tian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Gao, X.; Zhong, T.; others. Understanding llms: A comprehensive overview from training to inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.02038 2024.

- Cui, C.; Ma, Y.; Cao, X.; Ye, W.; Zhou, Y.; Liang, K.; Chen, J.; Lu, J.; Yang, Z.; Liao, K.D.; others. A survey on multimodal large language models for autonomous driving. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, 2024, pp. 958–979.

- Chang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Wu, Y.; Yang, L.; Zhu, K.; Chen, H.; Yi, X.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; others. A survey on evaluation of large language models. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15, 1–45. [CrossRef]

- Kachris, C. A survey on hardware accelerators for large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.09890 2024.

- Zhang, H.; Ning, A.; Prabhakar, R.; Wentzlaff, D. A Hardware Evaluation Framework for Large Language Model Inference. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.03134 2023.

- Korvala, A. Analysis of LLM-models in optimizing and designing VHDL code. Master’s thesis, Modern SW and Computing technolgies, Oulu University of Applied Sciences, 2023.

- Thakur, S.; Blocklove, J.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Garg, S.; Karri, R. Autochip: Automating hdl generation using llm feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.04887 2023.

- Thakur, S.; Ahmad, B.; Fan, Z.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Karri, R.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Garg, S. Benchmarking large language models for automated verilog rtl code generation. In 2023 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE), 2023.

- Blocklove, J.; Garg, S.; Karri, R.; Pearce, H. Chip-chat: Challenges and opportunities in conversational hardware design. 2023 ACM/IEEE 5th Workshop on Machine Learning for CAD (MLCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Chang, K.; Wang, Y.; Ren, H.; Wang, M.; Liang, S.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X. Chipgpt: How far are we from natural language hardware design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14019 2023. [CrossRef]

- Martínez, P.A.; Bernabé, G.; García, J.M. Code Detection for Hardware Acceleration Using Large Language Models. IEEE Access 2024.

- DeLorenzo, M.; Gohil, V.; Rajendran, J. CreativEval: Evaluating Creativity of LLM-Based Hardware Code Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.08806 2024.

- Tomlinson, M.; Li, J.; Andreou, A. Designing Silicon Brains using LLM: Leveraging ChatGPT for Automated Description of a Spiking Neuron Array. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.10920 2024.

- Xiang, M.; Goh, E.; Teo, T.H. Digital ASIC Design with Ongoing LLMs: Strategies and Prospects. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.02329 2024.

- Wang, H.; others. Efficient algorithms and hardware for natural language processing. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2020.

- Fu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, Z.; Li, S.; Ye, Z.; Li, C.; Wan, C.; Lin, Y.C. Gpt4aigchip: Towards next-generation ai accelerator design automation via large language models. 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–9.

- Fu, W.; Li, S.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, H.; Dutta, R.; Zhang, X.; Yang, K.; Jin, Y.; Guo, X. Hardware Phi-1.5 B: A Large Language Model Encodes Hardware Domain Specific Knowledge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01728 2024.

- Wang, H.; Wu, Z.; Liu, Z.; Cai, H.; Zhu, L.; Gan, C.; Han, S. Hat: Hardware-aware transformers for efficient natural language processing. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.14187 2020.

- Chang, K.; Ren, H.; Wang, M.; Liang, S.; Han, Y.; Li, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y. Improving Large Language Model Hardware Generating Quality through Post-LLM Search. Machine Learning for Systems 2023, 2023.

- Guo, C.; Tang, J.; Hu, W.; Leng, J.; Zhang, C.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Guo, M.; Zhu, Y. Olive: Accelerating large language models via hardware-friendly outlier-victim pair quantization. Proceedings of the 50th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2023, pp. 1–15.

- Liu, S.; Fang, W.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z. Rtlcoder: Outperforming gpt-3.5 in design rtl generation with our open-source dataset and lightweight solution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.08617 2023.

- Lu, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z. Rtllm: An open-source benchmark for design rtl generation with large language model. 2024 29th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 722–727.

- Pandelea, V.; Ragusa, E.; Gastaldo, P.; Cambria, E. Selecting Language Models Features VIA Software-Hardware Co-Design. ICASSP 2023-2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Cerisara, C. SlowLLM: large language models on consumer hardware. PhD thesis, CNRS, 2023.

- Li, M.; Fang, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xie, Z. Specllm: Exploring generation and review of vlsi design specification with large language model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.13266 2024.

- Kurtić, E.; Frantar, E.; Alistarh, D. ZipLM: Inference-Aware Structured Pruning of Language Models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36.

- Thorat, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, H.; Xie, X.; Lei, B.; Zhang, J.; Ding, C. Advanced language model-driven verilog development: Enhancing power, performance, and area optimization in code synthesis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.01022 2023.

- Huang, Y.; Wan, L.J.; Ye, H.; Jha, M.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. New Solutions on LLM Acceleration, Optimization, and Application. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.10903 2024.

- Goh, E.; Xiang, M.; Wey, I.; Teo, T.H.; others. From English to ASIC: Hardware Implementation with Large Language Model. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.07039 2024.

- Mudigere, D.; Hao, Y.; Huang, J.; Jia, Z.; Tulloch, A.; Sridharan, S.; Liu, X.; Ozdal, M.; Nie, J.; Park, J.; others. Software-hardware co-design for fast and scalable training of deep learning recommendation models. Proceedings of the 49th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture, 2022, pp. 993–1011.

- Wan, L.J.; Huang, Y.; Li, Y.; Ye, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. Software/Hardware Co-design for LLM and Its Application for Design Verification. 2024 29th Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference (ASP-DAC). IEEE, 2024, pp. 435–441.

- Yan, Z.; Qin, Y.; Hu, X.S.; Shi, Y. On the viability of using llms for sw/hw co-design: An example in designing cim dnn accelerators. 2023 IEEE 36th International System-on-Chip Conference (SOCC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Nazzal, M.; Vungarala, D.; Morsali, M.; Zhang, C.; Ghosh, A.; Khreishah, A.; Angizi, S. A Dataset for Large Language Model-Driven AI Accelerator Generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.10875 2024.

- Vungarala, D.L.V.D. Gen-acceleration: Pioneering work for hardware accelerator generation using large language models. Master’s thesis, Electrical and Computer Engineering, New Jersey Institute of Technology, 2023.

- Heo, G.; Lee, S.; Cho, J.; Choi, H.; Lee, S.; Ham, H.; Kim, G.; Mahajan, D.; Park, J. NeuPIMs: NPU-PIM Heterogeneous Acceleration for Batched LLM Inferencing. Proceedings of the 29th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 3, 2024, pp. 722–737.

- Lai, C.; Zhou, Z.; Poptani, A.; Zhang, W. LCM: LLM-focused Hybrid SPM-cache Architecture with Cache Management for Multi-Core AI Accelerators. Proceedings of the 38th ACM International Conference on Supercomputing, 2024, pp. 62–73.

- Paria, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Bhunia, S. Divas: An llm-based end-to-end framework for soc security analysis and policy-based protection. arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.06932 2023.

- Srikumar, P. Fast and wrong: The case for formally specifying hardware with LLMS. Proceedings of the International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems (ASPLOS). ACM. ACM Press, 2023.

- Ahmad, B.; Thakur, S.; Tan, B.; Karri, R.; Pearce, H. Fixing hardware security bugs with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.01215 2023.

- Kokolakis, G.; Moschos, A.; Keromytis, A.D. Harnessing the power of general-purpose llms in hardware trojan design. Proceedings of the 5th Workshop on Artificial Intelligence in Hardware Security, in conjunction with ACNS, 2024, Vol. 14.

- Saha, D.; Tarek, S.; Yahyaei, K.; Saha, S.K.; Zhou, J.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. Llm for soc security: A paradigm shift. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.06046 2023.

- Wang, Z.; Alrahis, L.; Mankali, L.; Knechtel, J.; Sinanoglu, O. LLMs and the Future of Chip Design: Unveiling Security Risks and Building Trust. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.07061 2024.

- Ahmad, B.; Thakur, S.; Tan, B.; Karri, R.; Pearce, H. On hardware security bug code fixes by prompting large language models. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024. [CrossRef]

- Kande, R.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Thakur, S.; Karri, R.; Rajendran, J. (Security) Assertions by Large Language Models. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tarek, S.; Saha, D.; Saha, S.K.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. SoCureLLM: An LLM-driven Approach for Large-Scale System-on-Chip Security Verification and Policy Generation. Cryptology ePrint Archive 2024.

- Paria, S.; Dasgupta, A.; Bhunia, S. Navigating SoC Security Landscape on LLM-Guided Paths. Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2024, 2024, pp. 252–257.

- Yao, X.; Li, H.; Chan, T.H.; Xiao, W.; Yuan, M.; Huang, Y.; Chen, L.; Yu, B. Hdldebugger: Streamlining hdl debugging with large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.11671 2024.

- Fu, W.; Yang, K.; Dutta, R.G.; Guo, X.; Qu, G. LLM4SecHW: Leveraging domain-specific large language model for hardware debugging. 2023 Asian Hardware Oriented Security and Trust Symposium (AsianHOST). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Fang, W.; Li, M.; Li, M.; Yan, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, H.; Xie, Z. AssertLLM: Generating and Evaluating Hardware Verification Assertions from Design Specifications via Multi-LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.00386 2024.

- Orenes-Vera, M.; Martonosi, M.; Wentzlaff, D. Using llms to facilitate formal verification of rtl. arXiv e-prints 2023, pp. arXiv–2309.

- Varambally, B.S.; Sehgal, N. Optimising design verification using machine learning: An open source solution. arXiv preprint arXiv:2012.02453 2020.

- Liu, M.; Pinckney, N.; Khailany, B.; Ren, H. Verilogeval: Evaluating large language models for verilog code generation. 2023 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Computer Aided Design (ICCAD). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–8.

- Sun, C.; Hahn, C.; Trippel, C. Towards improving verification productivity with circuit-aware translation of natural language to systemverilog assertions. First International Workshop on Deep Learning-aided Verification, 2023.

- Liu, M.; Ene, T.D.; Kirby, R.; Cheng, C.; Pinckney, N.; Liang, R.; Alben, J.; Anand, H.; Banerjee, S.; Bayraktaroglu, I.; others. Chipnemo: Domain-adapted llms for chip design. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.00176 2023.

- Zhang, Z.; Chadwick, G.; McNally, H.; Zhao, Y.; Mullins, R. Llm4dv: Using large language models for hardware test stimuli generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2310.04535 2023.

- Kande, R.; Pearce, H.; Tan, B.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Thakur, S.; Karri, R.; Rajendran, J. Llm-assisted generation of hardware assertions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.14027 2023.

- Makatura, L.; Foshey, M.; Wang, B.; Hähnlein, F.; Ma, P.; Deng, B.; Tjandrasuwita, M.; Spielberg, A.; Owens, C.E.; Chen, P.Y.; Zhao, A.; Zhu, A.; Norton, W.J.; Gu, E.; Jacob, J.; Li, Y.; Schulz, A.; Matusik, W. Large Language Models for Design and Manufacturing. An MIT Exploration of Generative AI 2024. https://mit-genai.pubpub.org/pub/nmypmnhs.

- Du, Y.; Deng, H.; Liew, S.C.; Chen, K.; Shao, Y.; Chen, H. The Power of Large Language Models for Wireless Communication System Development: A Case Study on FPGA Platforms, 2024, [arXiv:eess.SP/2307.07319].

- Englhardt, Z.; Li, R.; Nissanka, D.; Zhang, Z.; Narayanswamy, G.; Breda, J.; Liu, X.; Patel, S.; Iyer, V. Exploring and Characterizing Large Language Models For Embedded System Development and Debugging, 2023, [arXiv:cs.SE/2307.03817].

- Thorat, K.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, H.; Xie, X.; Lei, B.; Zhang, J.; Ding, C. Advanced Large Language Model (LLM)-Driven Verilog Development: Enhancing Power, Performance, and Area Optimization in Code Synthesis, 2024, [arXiv:cs.LG/2312.01022].

- Lian, X.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, R.; Huang, J.; Thakkar, P.; Zhang, M.; Xu, T. Configuration Validation with Large Language Models, 2024, [arXiv:cs.SE/2310.09690].

- Sandal, S.; Akturk, I. Zero-Shot RTL Code Generation with Attention Sink Augmented Large Language Models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2401.08683 2024.

- Parchamdar, B.; Schafer, B.C. Finding Bugs in RTL Descriptions: High-Level Synthesis to the Rescue. Proceedings of 61st Design Automation Conference (DAC), 2024.

- Tavana, M.K.; Teimouri, N.; Abdollahi, M.; Goudarzi, M. Simultaneous hardware and time redundancy with online task scheduling for low energy highly reliable standby-sparing system. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2014, 13, 86–1. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Hu, S.; Li, C.; Li, G.; Shi, W. Resource scheduling in edge computing: A survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2021, 23, 2131–2165.

- Kumar, S.; Singh, S.K.; Aggarwal, N.; Gupta, B.B.; Alhalabi, W.; Band, S.S. An efficient hardware supported and parallelization architecture for intelligent systems to overcome speculative overheads. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2022, 37, 11764–11790. [CrossRef]

- Kao, S.C.; Jeong, G.; Krishna, T. Confuciux: Autonomous hardware resource assignment for dnn accelerators using reinforcement learning. 2020 53rd Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture (MICRO). IEEE, 2020, pp. 622–636.

- Alwan, E.H.; Ketran, R.M.; Hussein, I.A. A Comprehensive Survey on Loop Unrolling Technique In Code Optimization. Journal of University of Babylon for Pure and Applied Sciences 2024, pp. 108–117.

- Liu, Y.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, B.; Liu, L.; Wang, J.; Tang, S. Improving the computational efficiency and flexibility of FPGA-based CNN accelerator through loop optimization. Microelectronics Journal 2024, 147, 106197. [CrossRef]

- Hasan, B.M.S.; Abdulazeez, A.M. A review of principal component analysis algorithm for dimensionality reduction. Journal of Soft Computing and Data Mining 2021, 2, 20–30.

- Wang, Q.; Li, X.; Yue, C.; He, Y. A Survey of Control Flow Graph Recovery for Binary Code. CCF National Conference of Computer Applications. Springer, 2023, pp. 225–244.

- Talati, N.; May, K.; Behroozi, A.; Yang, Y.; Kaszyk, K.; Vasiladiotis, C.; Verma, T.; Li, L.; Nguyen, B.; Sun, J.; others. Prodigy: Improving the memory latency of data-indirect irregular workloads using hardware-software co-design. 2021 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA). IEEE, 2021, pp. 654–667.

- Ayers, G.; Litz, H.; Kozyrakis, C.; Ranganathan, P. Classifying memory access patterns for prefetching. Proceedings of the Twenty-Fifth International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, 2020, pp. 513–526.

- Kastner, R.; Gong, W.; Hao, X.; Brewer, F.; Kaplan, A.; Brisk, P.; Sarrafzadeh, M. Physically Aware Data Communication Optimization for Hardware Synthesis.

- Fan, Z. Automatically Generating Verilog RTL Code with Large Language Models. Master’s thesis, New York University Tandon School of Engineering, 2023.

- Lekidis, A. Automated Code Generation for Industrial Applications Based on Configurable Programming Models 2023.

- Bhandari, J.; Knechtel, J.; Narayanaswamy, R.; Garg, S.; Karri, R. LLM-Aided Testbench Generation and Bug Detection for Finite-State Machines. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.17132 2024.

- Kibria, R.; Farahmandi, F.; Tehranipoor, M. FSMx-Ultra: Finite State Machine Extraction from Gate-Level Netlist for Security Assessment. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2023, 42, 3613–3627. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, L.; Ishikawa, Y. HDLRuby: A Ruby Extension for Hardware Description and its Translation to Synthesizable Verilog HDL. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems 2024, 23, 1–26. [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.I.; Schaefer, B.C. VeriPy: A Python-Powered Framework for Parsing Verilog HDL and High-Level Behavioral Analysis of Hardware. 2024 IEEE 17th Dallas Circuits and Systems Conference (DCAS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–6.

- Morgan, F.; Byrne, J.P.; Bupathi, A.; George, R.; Elahi, A.; Callaly, F.; Kelly, S.; O’Loughlin, D. HDLGen-ChatGPT Case Study: RISC-V Processor VHDL and Verilog Model-Testbench and EDA Project Generation. Proceedings of the 34th International Workshop on Rapid System Prototyping, 2023, pp. 1–7.

- Kumar, B.; Nanda, S.; Parthasarathy, G.; Patil, P.; Tsai, A.; Choudhary, P. HDL-GPT: High-Quality HDL is All You Need. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.18423 2024.

- Qiu, R.; Zhang, G.L.; Drechsler, R.; Schlichtmann, U.; Li, B. AutoBench: Automatic Testbench Generation and Evaluation Using LLMs for HDL Design. Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Machine Learning for CAD, 2024, pp. 1–10.

- Wenzel, J.; Hochberger, C. Automatically Restructuring HDL Modules for Improved Reusability in Rapid Synthesis. 2022 IEEE International Workshop on Rapid System Prototyping (RSP). IEEE, 2022, pp. 43–49.

- Witharana, H.; Lyu, Y.; Charles, S.; Mishra, P. A survey on assertion-based hardware verification. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–33. [CrossRef]

- Agostini, N.B.; Haris, J.; Gibson, P.; Jayaweera, M.; Rubin, N.; Tumeo, A.; Abellán, J.L.; Cano, J.; Kaeli, D. AXI4MLIR: User-Driven Automatic Host Code Generation for Custom AXI-Based Accelerators. 2024 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Code Generation and Optimization (CGO). IEEE, 2024, pp. 143–157.

- Vivekananda, A.A.; Enoiu, E. Automated test case generation for digital system designs: A mapping study on vhdl, verilog, and systemverilog description languages. Designs 2020, 4, 31. [CrossRef]

- Nuocheng, W. HDL Synthesis, Inference and Technology Mapping Algorithms for FPGA Configuration. International Journal of Engineering and Technology 2024, 16, 32–38.

- Cardona Nadal, J. Practical strategies to monitor and control contention in shared resources of critical real-time embedded systems. PhD thesis, Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, 2023.

- Jayasena, A.; Mishra, P. Directed test generation for hardware validation: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2024, 56, 1–36. [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Mukherjee, R.; Marschner, E.; Seeley, C.; Dobre, S. Low Power SoC Verification: IP Reuse and Hierarchical Composition using UPF. DVCon proceedings 2012.

- Mullane, B.; MacNamee, C. Developing a reusable IP platform within a System-on-Chip design framework targeted towards an academic R&D environment. Design and Reuse 2008.

- Leipnitz, M.T.; Nazar, G.L. High-level synthesis of approximate designs under real-time constraints. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS) 2019, 18, 1–21. [CrossRef]

- Gangadharan, S.; Churiwala, S. Constraining Designs for Synthesis and Timing Analysis; Springer, 2013.

- Namazi, A.; Abdollahi, M. PCG: Partially clock-gating approach to reduce the power consumption of fault-tolerant register files. 2017 Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design (DSD). IEEE, 2017, pp. 323–328.

- Namazi, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Safari, S.; Mohammadi, S. LORAP: low-overhead power and reliability-aware task mapping based on instruction footprint for real-time applications. 2017 Euromicro Conference on Digital System Design (DSD). IEEE, 2017, pp. 364–367.

- Alireza, N.; Meisam, A. LPVM: Low-Power Variation-Mitigant Adder Architecture Using Carry Expedition. Workshop on Early Reliability Modeling for Aging and Variability in Silicon Systems, 2016, pp. 41–44.

- Chandra, A.; Chattopadhyay, S. Design of hardware efficient FIR filter: A review of the state-of-the-art approaches. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2016, 19, 212–226. [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, D.; Harlap, A.; Phanishayee, A.; Seshadri, V.; Devanur, N.R.; Ganger, G.R.; Gibbons, P.B.; Zaharia, M. PipeDream: Generalized pipeline parallelism for DNN training. Proceedings of the 27th ACM symposium on operating systems principles, 2019, pp. 1–15.

- Osawa, K.; Li, S.; Hoefler, T. PipeFisher: Efficient training of large language models using pipelining and Fisher information matrices. Proceedings of Machine Learning and Systems 2023, 5, 708–727.

- Shibo, C.; Zhang, H.; Todd, A. Zipper: Latency-Tolerant Optimizations for High-Performance Buses. To Appear in The Asia and South Pacific Design Automation Conference, 2025.

- Shammasi, M.; Baharloo, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Baniasadi, A. Turn-aware application mapping using reinforcement learning in power gating-enabled network on chip. 2022 IEEE 15th International Symposium on Embedded Multicore/Many-core Systems-on-Chip (MCSoC). IEEE, 2022, pp. 345–352.

- Aligholipour, R.; Baharloo, M.; Farzaneh, B.; Abdollahi, M.; Khonsari, A. TAMA: turn-aware mapping and architecture–a power-efficient network-on-chip approach. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems (TECS) 2021, 20, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Jayakrishnan, M.; Chang, A.; Kim, T.T.H. Power and area efficient clock stretching and critical path reshaping for error resilience. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications 2019, 9, 5. [CrossRef]

- Smith, F.; Van den Berg, A.E. Hardware genetic algorithm optimisation by critical path analysis using a custom VLSI architecture. South African Computer Journal 2015, 56, 120–135. [CrossRef]

- Barkalov, A.; Titarenko, L.; Mielcarek, K.; Mazurkiewicz, M. Hardware reduction for FSMs with extended state codes. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef]

- Barkalov, A.; Titarenko, L.; CHMIELEWSKI, S. Hardware reduction in CPLD-based Moore FSM. Journal of Circuits, Systems and Computers 2014, 23, 1450086. [CrossRef]

- Barkalov, A.; Titarenko, L.; Malcheva, R.; Soldatov, K. Hardware reduction in FPGA-based Moore FSM. Journal of Circuits, Systems and Computers 2013, 22, 1350006. [CrossRef]

- Fummi, F.; Sciuto, D. A complete testing strategy based on interacting and hierarchical FSMs. Integration 1997, 23, 75–93. [CrossRef]

- Farahmandi, F.; Rahman, M.S.; Rajendran, S.R.; Tehranipoor, M. CAD for Fault Injection Detection. In CAD for Hardware Security; Springer, 2023; pp. 149–168.

- Minns, P.D. Digital System Design Using FSMs: A Practical Learning Approach; John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

- Barkalov, A.; Titarenko, L.; Bieganowski, J.; Krzywicki, K. Basic Approaches for Reducing Power Consumption in Finite State Machine Circuits—A Review. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 2693. [CrossRef]

- Okada, S.; Ohzeki, M.; Taguchi, S. Efficient partition of integer optimization problems with one-hot encoding. Scientific reports 2019, 9, 13036. [CrossRef]

- Uyar, M.Ü.; Fecko, M.A.; Sethi, A.S.; Amer, P.D. Testing protocols modeled as FSMs with timing parameters. Computer Networks 1999, 31, 1967–1988. [CrossRef]

- Amir, M.; Givargis, T. Pareto optimal design space exploration of cyber-physical systems. Internet of things 2020, 12, 100308. [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Si, L.; Zhang, X.; Cheng, R.; He, C.; Tan, K.C.; Jin, Y. Evolutionary large-scale multi-objective optimization: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–34. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shami, A. On hyperparameter optimization of machine learning algorithms: Theory and practice. Neurocomputing 2020, 415, 295–316. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramaniam, D.; Jefferson, C.; Kotthoff, L.; Miguel, I.; Nightingale, P. An automated approach to generating efficient constraint solvers. 2012 34th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE). IEEE, 2012, pp. 661–671.

- Abdollahi, M.; Mashhadi, S.; Sabzalizadeh, R.; Mirzaei, A.; Elahi, M.; Baharloo, M.; Baniasadi, A. IODnet: Indoor/Outdoor Telecommunication Signal Detection through Deep Neural Network. 2023 IEEE 16th International Symposium on Embedded Multicore/Many-core Systems-on-Chip (MCSoC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 134–141.

- Mashhadi, S.; Diyanat, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Baniasadi, A. DSP: A Deep Neural Network Approach for Serving Cell Positioning in Mobile Networks. 2023 10th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Abdollahi, M.; Sabzalizadeh, R.; Javadinia, S.; Mashhadi, S.; Mehrizi, S.S.; Baniasadi, A. Automatic Modulation Classification for NLOS 5G Signals with Deep Learning Approaches. 2023 10th International Conference on Wireless Networks and Mobile Communications (WINCOM). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–6.

- Yoo, H.J.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.K. Low-power noc for high-performance soc design; CRC press, 2018.

- Baharloo, M.; Aligholipour, R.; Abdollahi, M.; Khonsari, A. ChangeSUB: a power efficient multiple network-on-chip architecture. Computers & Electrical Engineering 2020, 83, 106578.

- Yenugula, M. Data Center Power Management Using Neural Network. International Journal of Advanced Academic Studies, 3, 320–25.

- Kose, N.A.; Jinad, R.; Rasheed, A.; Shashidhar, N.; Baza, M.; Alshahrani, H. Detection of Malicious Threats Exploiting Clock-Gating Hardware Using Machine Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 983. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sheng, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Mobile-edge computing: Partial computation offloading using dynamic voltage scaling. IEEE Transactions on Communications 2016, 64, 4268–4282. [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Li, D.; Ogrenci-Memik, S.; Deptuch, G.; Hoff, J.; Jindariani, S.; Liu, T.; Olsen, J.; Tran, N. Multi-Vdd design for content addressable memories (CAM): A power-delay optimization analysis. Journal of Low Power Electronics and Applications 2018, 8, 25. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Bisht, M.R. Leakage Power Reduction in CMOS VLSI Circuits using Advance Leakage Reduction Method. International Journal for Research in Applied Science and Engineering Technology 2021, 9, 962–966. [CrossRef]

- Pathak, A.; Sachan, D.; Peta, H.; Goswami, M. A modified SRAM based low power memory design. 2016 29th international conference on VLSI design and 2016 15th international conference on embedded systems (VLSID). IEEE, 2016, pp. 122–127.

- Birla, S.; Singh, N.; Shukla, N. Low-power memory design for IoT-enabled systems: Part 2. In Electrical and Electronic Devices, Circuits and Materials; CRC Press, 2021; pp. 63–80.

- Cao, R.; Yang, Y.; Gu, H.; Huang, L. A thermal-aware power allocation method for optical network-on-chip. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 61176–61183. [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Barekatain, B.; Abdollahi, M. Power loss analysis in thermally-tuned nanophotonic switch for on-chip interconnect. Nano Communication Networks 2020, 26, 100323. [CrossRef]

- Bhasker, J.; Chadha, R. Static timing analysis for nanometer designs: A practical approach; Springer Science & Business Media, 2009.

- Willis, R. Critical path analysis and resource constrained project scheduling—theory and practice. European Journal of Operational Research 1985, 21, 149–155. [CrossRef]

- Kao, C.C. Clock skew minimization in multiple dynamic supply voltage with adjustable delay buffers restriction. Journal of Signal Processing Systems 2015, 79, 99–104. [CrossRef]

- Hatture, S.; Dhage, S. Multi-clock domain synchronizers. 2015 International Conference on Computation of Power, Energy, Information and Communication (ICCPEIC). IEEE, 2015, pp. 0403–0408.

- Saboori, E.; Abdi, S. Rapid design space exploration of multi-clock domain MPSoCs with Hybrid Prototyping. 2016 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering (CCECE). IEEE, 2016, pp. 1–6.

- Chentouf, M.; Ismaili, Z.E.A.A. A PUS based nets weighting mechanism for power, hold, and setup timing optimization. Integration 2022, 84, 122–130. [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M.; Yeh, I.H. Designing network design strategies through gradient path analysis. arXiv preprint arXiv:2211.04800 2022.

- Mirhoseini, A.; Goldie, A.; Yazgan, M.; Jiang, J.W.; Songhori, E.; Wang, S.; Lee, Y.J.; Johnson, E.; Pathak, O.; Nazi, A.; others. A graph placement methodology for fast chip design. Nature 2021, 594, 207–212. [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Nandi, S.; Trivedi, G. PowerPlanningDL: Reliability-aware framework for on-chip power grid design using deep learning. 2020 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1520–1525.

- Szentimrey, H.; Al-Hyari, A.; Foxcroft, J.; Martin, T.; Noel, D.; Grewal, G.; Areibi, S. Machine learning for congestion management and routability prediction within FPGA placement. ACM Transactions on Design Automation of Electronic Systems (TODAES) 2020, 25, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.M.; Chang, W.Y.; Hsieh, H.Y.; Shyu, Y.T.; Chang, Y.J.; Lu, J.M. Thermal-aware floorplanning and TSV-planning for mixed-type modules in a fixed-outline 3-D IC. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems 2021, 29, 1652–1664. [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Tang, X.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Thermal-Aware Fixed-Outline 3-D IC Floorplanning: An End-to-End Learning-Based Approach. IEEE Transactions on Very Large Scale Integration (VLSI) Systems 2023.

- Kim, D.; Kim, M.; Hur, J.; Lee, J.; Cho, J.; Kang, S. TA3D: Timing-Aware 3D IC Partitioning and Placement by Optimizing the Critical Path. Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Machine Learning for CAD, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Xu, Q.; Rocha, R.T.; Algoos, Y.; Feron, E.; Younis, M.I. Design, simulation, and testing of a tunable MEMS multi-threshold inertial switch. Microsystems & Nanoengineering 2024, 10, 31.

- Hosseini, S.A.; Roosta, E. A novel technique to produce logic ‘1’in multi-threshold ternary circuits design. Circuits, Systems, and Signal Processing 2021, 40, 1152–1165. [CrossRef]

- Haj-Yahya, J.; Alser, M.; Kim, J.; Yağlıkçı, A.G.; Vijaykumar, N.; Rotem, E.; Mutlu, O. SysScale: Exploiting multi-domain dynamic voltage and frequency scaling for energy efficient mobile processors. 2020 ACM/IEEE 47th Annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA). IEEE, 2020, pp. 227–240.

- Tsou, W.J.; Yang, W.H.; Lin, J.H.; Chen, H.; Chen, K.H.; Wey, C.L.; Lin, Y.H.; Lin, S.R.; Tsai, T.Y. 20.2 digital low-dropout regulator with anti PVT-variation technique for dynamic voltage scaling and adaptive voltage scaling multicore processor. 2017 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). IEEE, 2017, pp. 338–339.

- Lungu, A.; Bose, P.; Buyuktosunoglu, A.; Sorin, D.J. Dynamic power gating with quality guarantees. Proceedings of the 2009 ACM/IEEE international symposium on Low power electronics and design, 2009, pp. 377–382.

- Jahanirad, H. Dynamic power-gating for leakage power reduction in FPGAs. Frontiers of Information Technology & Electronic Engineering 2023, 24, 582–598.

- Scarabottolo, I.; Ansaloni, G.; Constantinides, G.A.; Pozzi, L.; Reda, S. Approximate logic synthesis: A survey. Proceedings of the IEEE 2020, 108, 2195–2213. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zukerman, M.; Yung, E.K.N. Energy-efficient base-stations sleep-mode techniques in green cellular networks: A survey. IEEE communications surveys & tutorials 2015, 17, 803–826.

- Ning, S.; Zhu, H.; Feng, C.; Gu, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ying, Z.; Midkiff, J.; Jain, S.; Hlaing, M.H.; Pan, D.Z.; others. Photonic-Electronic Integrated Circuits for High-Performance Computing and AI Accelerators. Journal of Lightwave Technology 2024. [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, S. Hardware accelerator systems for artificial intelligence and machine learning. In Advances in Computers; Elsevier, 2021; Vol. 122, pp. 51–95.

- Hu, X.; Li, X.; Huang, H.; Zheng, X.; Xiong, X. Tinna: A tiny accelerator for neural networks with efficient dsp optimization. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2301–2305. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Cao, Y.; Sun, S. Mapping and optimization method of SpMV on Multi-DSP accelerator. Electronics 2022, 11, 3699. [CrossRef]

- Dai, K.; Xie, Z.; Liu, S. DCP-CNN: Efficient Acceleration of CNNs With Dynamic Computing Parallelism on FPGA. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024.

- Zacharopoulos, G.; Ejjeh, A.; Jing, Y.; Yang, E.Y.; Jia, T.; Brumar, I.; Intan, J.; Huzaifa, M.; Adve, S.; Adve, V.; others. Trireme: Exploration of hierarchical multi-level parallelism for hardware acceleration. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems 2023, 22, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Jamilan, S.; Abdollahi, M.; Mohammadi, S. Cache energy management through dynamic reconfiguration approach in opto-electrical noc. 2017 25th Euromicro International Conference on Parallel, Distributed and Network-based Processing (PDP). IEEE, 2017, pp. 576–583.

- Sanca, V.; Ailamaki, A. Post-Moore’s Law Fusion: High-Bandwidth Memory, Accelerators, and Native Half-Precision Processing for CPU-Local Analytics. Joint Workshops at 49th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (VLDBW’23), 2023.

- Hur, S.; Na, S.; Kwon, D.; Kim, J.; Boutros, A.; Nurvitadhi, E.; Kim, J. A fast and flexible FPGA-based accelerator for natural language processing neural networks. ACM Transactions on Architecture and Code Optimization 2023, 20, 1–24. [CrossRef]

- Kabir, E.; Kabir, M.A.; Downey, A.R.; Bakos, J.D.; Andrews, D.; Huang, M. FAMOUS: Flexible Accelerator for the Attention Mechanism of Transformer on UltraScale+ FPGAs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.14023 2024.

- Lee, H.; Lee, J.; Kang, S. A Robust Test Architecture for Low-Power AI Accelerators. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024.

- Lee, S.; Park, J.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kang, S. A New Zero-Overhead Test Method for Low-Power AI Accelerators. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems II: Express Briefs 2023.

- Shah, N.; Meert, W.; Verhelst, M. Efficient Execution of Irregular Dataflow Graphs: Hardware/Software Co-optimization for Probabilistic AI and Sparse Linear Algebra; Springer Nature, 2023.

- Rashidi, B.; Gao, C.; Lu, S.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, C.; Niu, D.; Sun, F. UNICO: Unified Hardware Software Co-Optimization for Robust Neural Network Acceleration. Proceedings of the 56th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2023, pp. 77–90.

- Arman, G. New Approach of IO Cell Placement Addressing Minimized Data and Clock Skews in Top Level. 2023 IEEE East-West Design & Test Symposium (EWDTS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–5.

- Deng, C.; Cai, Y.C.; Zhou, Q. Register clustering methodology for low power clock tree synthesis. Journal of Computer Science and Technology 2015, 30, 391–403. [CrossRef]

- Kyriakakis, E.; Tange, K.; Reusch, N.; Zaballa, E.O.; Fafoutis, X.; Schoeberl, M.; Dragoni, N. Fault-tolerant clock synchronization using precise time protocol multi-domain aggregation. 2021 IEEE 24th International Symposium on Real-Time Distributed Computing (ISORC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 114–122.

- Han, K.; Kahng, A.B.; Li, J. Optimal generalized H-tree topology and buffering for high-performance and low-power clock distribution. Ieee transactions on computer-aided design of integrated circuits and systems 2018, 39, 478–491. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.S.; Guo, R.; Kamali, H.M.; Rahman, F.; Farahmandi, F.; Abdel-Moneum, M.; Tehranipoor, M. O’clock: lock the clock via clock-gating for soc ip protection. Proceedings of the 59th ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conference, 2022, pp. 775–780.

- Hu, K.; Hou, X.; Lin, Z. Advancements In Low-Power Technologies: Clock-Gated Circuits and Beyond. Highlights in Science, Engineering and Technology 2024, 81, 218–225. [CrossRef]

- Erra, R.; Stine, J.E. Power Reduction of Montgomery Multiplication Architectures Using Clock Gating. 2024 IEEE 67th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 474–478.

- Namazi, A.; Safari, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Abdollahi, M. SORT: Semi online reliable task mapping for embedded multi-core systems. ACM Transactions on Modeling and Performance Evaluation of Computing Systems (TOMPECS) 2019, 4, 1–25. [CrossRef]

- Namazi, A.; Abdollahi, M.; Safari, S.; Mohammadi, S.; Daneshtalab, M. Lrtm: Life-time and reliability-aware task mapping approach for heterogeneous multi-core systems. 2018 11th International Workshop on Network on Chip Architectures (NoCArc). IEEE, 2018, pp. 1–6.

- Abumwais, A.; Obaid, M. Shared Cache Based on Content Addressable Memory in a Multi-Core Architecture. Computers, Materials & Continua 2023, 74.

- Bahn, H.; Cho, K. Implications of NVM based storage on memory subsystem management. Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 999. [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, R.; Abi-Karam, S.; He, Y.; Sathidevi, L.; Hao, C. FlowGNN: A dataflow architecture for real-time workload-agnostic graph neural network inference. 2023 IEEE International Symposium on High-Performance Computer Architecture (HPCA). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1099–1112.

- Kenter, T.; Shambhu, A.; Faghih-Naini, S.; Aizinger, V. Algorithm-hardware co-design of a discontinuous Galerkin shallow-water model for a dataflow architecture on FPGA. Proceedings of the Platform for Advanced Scientific Computing Conference, 2021, pp. 1–11.

- Besta, M.; Kanakagiri, R.; Kwasniewski, G.; Ausavarungnirun, R.; Beránek, J.; Kanellopoulos, K.; Janda, K.; Vonarburg-Shmaria, Z.; Gianinazzi, L.; Stefan, I.; others. Sisa: Set-centric instruction set architecture for graph mining on processing-in-memory systems. MICRO-54: 54th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2021, pp. 282–297.

- Sahabandu, D.; Mertoguno, J.S.; Poovendran, R. A natural language processing approach for instruction set architecture identification. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023, 18, 4086–4099. [CrossRef]

- Baharloo, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Baniasadi, A. System-level reliability assessment of optical network on chip. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2023, 99, 104843. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Baharloo, M.; Shokouhinia, F.; Ebrahimi, M. RAP-NOC: reliability assessment of photonic network-on-chips, a simulator. Proceedings of the Eight Annual ACM International Conference on Nanoscale Computing and Communication, 2021, pp. 1–7.

- Hasanzadeh, M.; Abdollahi, M.; Baniasadi, A.; Patooghy, A. Thermo-Attack Resiliency: Addressing a New Vulnerability in Opto-Electrical Network-on-Chips. 2024 25th International Symposium on Quality Electronic Design (ISQED). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–9.

- Anuradha, P.; Majumder, P.; Sivaraman, K.; Vignesh, N.A.; Jayakar, A.; Anthonirj, S.; Mallik, S.; Al-Rasheed, A.; Abbas, M.; Soufiene, B.O. Enhancing High-Speed Data Communications: Optimization of Route Controlling Network on Chip Implementation. IEEE Access 2024. [CrossRef]

- Nisa, U.U.; Bashir, J. Towards efficient on-chip communication: A survey on silicon nanophotonics and optical networks-on-chip. Journal of Systems Architecture 2024, p. 103171.

- Abdollahi, M.; Firouzabadi, Y.; Dehghani, F.; Mohammadi, S. THAMON: Thermal-aware High-performance Application Mapping onto Opto-electrical network-on-chip. Journal of Systems Architecture 2021, 121, 102315. [CrossRef]

- Bai, C.; Huang, J.; Wei, X.; Ma, Y.; Li, S.; Zheng, H.; Yu, B.; Xie, Y. ArchExplorer: Microarchitecture exploration via bottleneck analysis. Proceedings of the 56th Annual IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture, 2023, pp. 268–282.

- Dave, S.; Nowatzki, T.; Shrivastava, A. Explainable-DSE: An Agile and Explainable Exploration of Efficient HW/SW Codesigns of Deep Learning Accelerators Using Bottleneck Analysis. Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems, Volume 4, 2023, pp. 87–107.

- Bernstein, L.; Sludds, A.; Hamerly, R.; Sze, V.; Emer, J.; Englund, D. Freely scalable and reconfigurable optical hardware for deep learning. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 3144. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Ozatay, M.; Tang, Y.; Valavi, H.; Pathak, R.; Lee, J.; Verma, N. 15.1 a programmable neural-network inference accelerator based on scalable in-memory computing. 2021 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC). IEEE, 2021, Vol. 64, pp. 236–238.

- Lakshmanna, K.; Shaik, F.; Gunjan, V.K.; Singh, N.; Kumar, G.; Shafi, R.M. Perimeter degree technique for the reduction of routing congestion during placement in physical design of VLSI circuits. Complexity 2022, 2022, 8658770. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, G.; Xiong, N.; Su, Y.; Chen, G. A survey of swarm intelligence techniques in VLSI routing problems. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 26266–26292. [CrossRef]

- Karimullah, S.; Vishnuvardhan, D. Experimental analysis of optimization techniques for placement and routing in Asic design. ICDSMLA 2019: Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Data Science, Machine Learning and Applications. Springer, 2020, pp. 908–917.

- Ramesh, S.; Manna, K.; Gogineni, V.C.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Mahapatra, S. Congestion-Aware Vertical Link Placement and Application Mapping Onto Three-Dimensional Network-On-Chip Architectures. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024.

- Rocher-Gonzalez, J.; Escudero-Sahuquillo, J.; Garcia, P.J.; Quiles, F.J. Congestion management in high-performance interconnection networks using adaptive routing notifications. The Journal of Supercomputing 2023, 79, 7804–7834. [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.; Jo, H.; Lee, H.; Kim, M.; Im, Y. Fast and Real-Time Thermal-Aware Floorplan Methodology for SoC. IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology 2024.

- Cho, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, K.; Im, Y.; Lee, H.; Kim, M. Thermal Aware Floorplan Optimization of SoC in Mobile Phone. 2023 22nd IEEE Intersociety Conference on Thermal and Thermomechanical Phenomena in Electronic Systems (ITherm). IEEE, 2023, pp. 1–7.

- Dehghani, F.; Mohammadi, S.; Barekatain, B.; Abdollahi, M. ICES: an innovative crosstalk-efficient 2× 2 photonic-crystal switch. Optical and Quantum Electronics 2021, 53, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, G.; Kumar, Y.; others. RF and Crosstalk Characterization of Chip Interconnects Using Finite Element Method. Indian Journal of Engineering and Materials Sciences (IJEMS) 2023, 30, 132–137.

- Kashif, M.; Cicek, I. Field-programmable gate array (FPGA) hardware design and implementation ofa new area efficient elliptic curve crypto-processor. Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2021, 29, 2127–2139. [CrossRef]

- Bardon, M.G.; Sherazi, Y.; Jang, D.; Yakimets, D.; Schuddinck, P.; Baert, R.; Mertens, H.; Mattii, L.; Parvais, B.; Mocuta, A.; others. Power-performance trade-offs for lateral nanosheets on ultra-scaled standard cells. 2018 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology. IEEE, 2018, pp. 143–144.

- Gao, X.; Qiao, Q.; Wang, M.; Niu, M.; Liu, H.; Maezawa, M.; Ren, J.; Wang, Z. Design and verification of SFQ cell library for superconducting LSI digital circuits. IEEE Transactions on Applied Superconductivity 2021, 31, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Dannan, B.; Grumman, N.; Kuszewski, J.; Vincent, R.; Wu, S.; McCaffrey, W.; Park, A. Improved methodology to accurately perform system level power integrity analysis including an ASIC die. In presented at DesignCon; Signal Integrity Journal, 2022; pp. 5–7.

- Meixner, A.; Gullo, L.J. Design for Test and Testability. Design for Maintainability 2021, pp. 245–264.

- Huhn, S.; Drechsler, R. Design for Testability, Debug and Reliability; Springer, 2021.

- Deshpande, N.; Sowmya, K. A review on ASIC synthesis flow employing two industry standard tools. INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENGINEERING RESEARCH & TECHNOLOGY (IJERT) ICEECT–2020 2020, 8.

- Taraate, V. ASIC Design and Synthesis. Springer Nature 2021.

- Golshan, K. The Art of Timing Closure; Springer, 2020.

- Sariki, A.; Sai, G.M.V.; Khosla, M.; Raj, B. ASIC Design using Post Route ECO Methodologies for Timing Closure and Power Optimization. International Journal of Microsystems and IoT 2023.

- Lau, J.H. Recent advances and trends in advanced packaging. IEEE Transactions on Components, Packaging and Manufacturing Technology 2022, 12, 228–252. [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, M.; Mohammadi, S. Vulnerability assessment of fault-tolerant optical network-on-chips. Journal of Parallel and Distributed Computing 2020, 145, 140–159. [CrossRef]

- Hiller, M.; Kürzinger, L.; Sigl, G. Review of error correction for PUFs and evaluation on state-of-the-art FPGAs. Journal of cryptographic engineering 2020, 10, 229–247. [CrossRef]

- Djambazova, E.; Andreev, R. Redundancy Management in Dependable Distributed Real-Time Systems. In j. Problems of Engineering Cybernetics and Robotics; Prof. Marin Drinov Publishing House of Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 2023; Vol. 79, pp. 37–54.

- Oszczypała, M.; Ziółkowski, J.; Małachowski, J. Redundancy allocation problem in repairable k-out-of-n systems with cold, warm, and hot standby: A genetic algorithm for availability optimization. Applied Soft Computing 2024, 165, 112041. [CrossRef]

- Hantos, G.; Flynn, D.; Desmulliez, M.P. Built-in self-test (BIST) methods for MEMS: A review. Micromachines 2020, 12, 40. [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Lin, Y.; Gupta, S. Built in self test (BIST) for RSFQ circuits. 2024 IEEE 42nd VLSI Test Symposium (VTS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Verducci, O.; Oliveira, D.L.; Batista, G. Fault-tolerant finite state machine quasi delay insensitive in commercial FPGA devices. 2022 IEEE 13th Latin America Symposium on Circuits and System (LASCAS). IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–4.

- Salauyou, V. Fault Detection of Moore Finite State Machines by Structural Models. International Conference on Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management. Springer, 2023, pp. 394–409.

- Pavan Kumar, M.; Lorenzo, R. A review on radiation-hardened memory cells for space and terrestrial applications. International journal of circuit theory and applications 2023, 51, 475–499. [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Cho, S.; Lee, N.; Kim, J. New radiation-hardened design of a cmos instrumentation amplifier and its tolerant characteristic analysis. Electronics 2020, 9, 388. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, S.; Zhou, J.; Tian, C.; Feng, H. AIP-SEM: An Efficient ML-Boost In-Place Soft Error Mitigation Method for SRAM-Based FPGA. 2024 2nd International Symposium of Electronics Design Automation (ISEDA). IEEE, 2024, pp. 351–354.

- Xie, Y.; Qiao, T.; Xie, Y.; Chen, H. Soft error mitigation and recovery of SRAM-based FPGAs using brain-inspired hybrid-grained scrubbing mechanism. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 2023, 17, 1268374. [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Ding, N.; Li, N.; Liu, L.; Hou, N.; Xu, N.; Guo, W.; Tian, L.; Xu, H.; Wu, C.M.L.; others. A review of bearing failure Modes, mechanisms and causes. Engineering Failure Analysis 2023, p. 107518.

- Huang, J.; You, J.X.; Liu, H.C.; Song, M.S. Failure mode and effect analysis improvement: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Reliability Engineering & System Safety 2020, 199, 106885.

- Chen, B.; Zhang, F.; Nguyen, A.; Zan, D.; Lin, Z.; Lou, J.G.; Chen, W. Codet: Code generation with generated tests. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.10397 2022.

- Unno, H.; Terauchi, T.; Koskinen, E. Constraint-based relational verification. International Conference on Computer Aided Verification. Springer, 2021, pp. 742–766.

- Jha, C.K.; Qayyum, K.; Coşkun, K.Ç.; Singh, S.; Hassan, M.; Leupers, R.; Merchant, F.; Drechsler, R. veriSIMPLER: An Automated Formal Verification Methodology for SIMPLER MAGIC Design Style Based In-Memory Computing. IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems I: Regular Papers 2024.

- Coudert, S.; Apvrille, L.; Sultan, B.; Hotescu, O.; de Saqui-Sannes, P. Incremental and Formal Verification of SysML Models. SN Computer Science 2024, 5, 714. [CrossRef]

- Ayalasomayajula, A.; Farzana, N.; Tehranipoor, M.; Farahmandi, F. Automatic Asset Identification for Assertion-Based SoC Security Verification. IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems 2024.

- Rostami, H.; Hosseini, M.; Azarpeyvand, A.; Iman, M.R.H.; Ghasempouri, T. Automatic High Functional Coverage Stimuli Generation for Assertion-based Verification. 2024 IEEE 30th International Symposium on On-Line Testing and Robust System Design (IOLTS). IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–7.

- Tian, K.; Mitchell, E.; Yao, H.; Manning, C.D.; Finn, C. Fine-tuning language models for factuality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2311.08401 2023.

- Yang, Z. Scalable Equivalence Checking for Behavioral Synthesis. PhD thesis, Computer Science Department, Portland State University, 2015.

- Aboudeif, R.A.H. Design and Implementation of UVM-based Verification Framework for Deep Learning Accelerators. Master’s thesis, School of Sciences and Engineering, The American University in Cairo, 2024.

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 | |

| 5 | |

| 6 | |

| 7 |

| Paper | LLMs Model | LLMs API | LLMs Dataset | Domain LLMs | Taxonomy | LLMs Architecture | LLMs Configurations | ML Comparisons | Performance | Parameters and Hardware Specification |

Scope | Key Findings | Methodology and Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Huang et al. [93] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | LLM reasoning abilities |

Explores LLMs’ reasoning abilities and evaluation methodologies |

Reasoning-focused review |

| Xi et al. [94] | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | x | ✓ | x | LLM-based AI agents for multiple domains |

Highlights potential for LLMs as general-purpose agents |

Agent-centric analysis |

| Hadi et al. [95] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | Comprehensive review of LLMs, applications, and challenges |

Highlights potential of LLMs in various domains, discusses challenges and limitations |

Literature review and analysis |

| Naveed et al. [96] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Overview of LLM architectures and performance |

Challenges and advancements in LLM training, architectural innovations, and emergent abilities |

Comparative review of models and training methods |

| Fan et al. [97] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | x | x | x | x | Bibliometric review of LLM research (2017-2023) |

Tracks research trends, collaboration networks, and the evolution of LLM research |

Bibliometric analysis using topic modeling and citation networks |

| Zhao et al. [5] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | Comprehensive survey of LLM models, taxonomy |

Detailed analysis of LLMs evolution, taxonomy, emergent abilities, adaptation, and evaluation |

Thorough review, structured methodology and various benchmarks |

| Raiaan et al. [98] | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Comprehensive review of LLM architectures, applications, and challenges |

Discusses LLM development, applications in various domains, and societal impact |

Extensive literature review with comparisons and analysis of open issues |

| Minaee et al. [99] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | Comprehensive survey of LLM architectures, datasets, and performance |

Comprehensive review of LLM architectures, datasets, and evaluations |

Comprehensive survey and analysis |

| Liu et al. [100] | ✓ | x | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | Training and inference in LLMs |

Cost-efficient training and inference techniques are crucial for LLM development |

Comprehensive review of training techniques and inference optimizations |

| Cui et al. [101] | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | MLLMs for autonomous driving with extensive dataset coverage |

Explores the potential of MLLMs in autonomous vehicle systems |

Survey focusing on perception, planning, and control |

| Chang et al. [102] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Comprehensive evaluation of LLMs across multiple domains and tasks |

Details LLM evaluation protocols, benchmarks, and task categories |

Survey of evaluation methods for LLMs |

| Kachris et al. [103] | ✓ | x | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Hardware solutions for accelerating LLMs |

Energy efficiency improvements through hardware |

Survey on hardware accelerators for LLMs |

| Category | Task | Description |

|---|---|---|