1. Introduction

Sepsis is an extremely dangerous and life-threatening disease with mortality rates increasing by 4% every hour of delayed treatment, emphasizing the importance of timely intervention [

1,

2]. Modern continuous-monitoring blood culture systems (CMBCSs) have provided faster and more reliable diagnostic results to address the limitations of traditional culture methods, which require continuous manual observation after inoculating the culture media. While systems such as the BacT/Alert

® 3D (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Étoile, France) and BACTEC™ FX (Becton Dickinson and Company (BD), Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) have been among the most widely used, these were initially developed in the 1970s [

3,

4,

5]. These systems fundamentally detect the carbon dioxide produced by bacterial growth in blood culture bottles. Each company applies different engineering methods to sense bacterial proliferation automatically, ensuring that the systems can effectively identify microbial growth [

5].

While the CMBCS was designed to reduce time and labor significantly, the automated instrument demanded other essential resources, including a budget for optimal performance, infrastructure for reliable operation, and a suitable environment to contain consumables stably [

6]. These requirements posed challenges to the optimal functioning of CMBCS [

7,

8]. Consequently, smaller and more affordable systems have been developed and designed to meet the needs of these settings with limited space and financial resources [

6]. Although fully automated systems offer convenience, relying solely on such systems means accepting the inevitable challenges associated with achieving faster detection times [

4,

9]. These challenges often included complex maintenance requirements and other operational issues that came with the advanced automation technologies [

9,

10].

The identification and characterization of clinical microorganisms in Republic of Korea was a critical issue that led a significant attention both to the nation and individuals. This interest has led to that South Korea began actively participating in the World Health Organization (WHO)’s Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) in 2016, establishing a more advanced system that has led to the production of high-quality national data [

11,

12]. In response to growing interest and demand, a domestic CMBCS was developed and tailored to the local environment and resources. To evaluate the performance of this system, an in vitro comparative performance evaluation was conducted using simulated sepsis specimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism Preparation

Our research focused on microorganisms of particular interest in South Korea to assess the practical utility of this equipment in real-world settings [

13]. This analysis included the representative pathogens of clinical infections and organisms commonly used for quality control in laboratories. The selected gram-positive bacteria included

Staphylococcus aureus (SAU) and

Streptococcus pneumoniae (SPN), whereas

Escherichia coli (ECO) and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PAE) were the gram-negative bacteria. This study also included

Bacteroides fragilis (BFR) as an anaerobic bacterium and

Candida albicans (CAL) as a fungal species.

Once the required microorganisms were identified, fresh pure cultures were prepared on the previous day. For pure cultures, sheep blood agar BAP (BANDIO BioScience Co., Pocheon-si, South Korea) was used for gram-positive bacteria, and MacConkey agar MAC (BANDIO BioScience Co.) was used for ECO and PAE. BFR was cultured on BRUCELLA Blood Agar (BANDIO BioScience Co.) with a desiccant, and CAL was grown on SDAC (BANDIO BioScience Co.).

2.2. Instruments with Culture Bottles

Samples used for comparative analysis consisted of in vitro specimens, while instruments, which were BACTEC™ FX (BD), BacT/Alert® 3D (bioMérieux), in real set in clinical laboratories were employed for this research. HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc., Chuncheon-si, South Korea), the instrument selected for comparison, was implemented within a clinical laboratory where other CMBCSs were established. Each system was provided with a manufacturer-specific aerobic or anaerobic medium. In the BACTEC™ FX (BD), BACTEC™ Plus Aerobic/F Culture Vials (BD) and BACTEC™ Lytic/10 Anaerobic/F Culture Vials (BD) were used as aerobic and anaerobic media, respectively. Similarly, in BacT/Alert® 3D (bioMérieux), BACT/ALERT® SA (bioMérieux) served as an aerobic media, while BACT/ALERT® SN (bioMérieux) was designated for an anaerobic culture bottle. Hubix A (HUFIT Inc.) and Hubix N (HUFIT Inc.) were used as the exclusive aerobic and anaerobic culture bottles, respectively, for the HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.).

2.3. Simulated Septic Blood Specimen

Clinical microbiology laboratories prepare diagnostic specimens by suspending bacterial colonies in a solution based on the turbidity standards proposed by McFarland [

14,

15]. However, at the early onset of sepsis, blood colony-forming units (CFU) levels were markedly low, typically less than 10 CFU/mL in neonates and under 100 CFU/mL in adults [

16,

17]. Consequently, this study involved diluting the samples to create simulated sepsis specimens (SSS). Normal saline (NS) was used for the dilutions. The initial McFarland standard was set to 0.33 using the DENSICHEK

® Plus Standards Kit (bioMérieux).

On the day of the experiment, each culture bottle was designed to receive 3 mL of SSS, and the total SSS volume was calculated. Even when SSS is prepared from the same microorganism, creating samples on different days could generate bias. Therefore, on each experimental day, a sufficient quantity of SSS was produced to allow comparisons across multiple instruments. The colonies were transferred from the solid agar plates, and the entire SSS was adjusted to the final dilution concentration within 30 min. The process, from preparation to injection into the culture bottles, was completed in less than 30 min to ensure uniformity.

2.4. CFU Verification and Growth Confirmation

A 5 mL syringe was used to inject SSS into each culture bottle. Because of the differing nutrient composition of each medium, procedures were implemented to reduce the carryover contamination bias using syringes.

The entire SSS was divided into several culture bottles requiring inoculation;

A single syringe was used to inoculate no more than five bottles;

After the inoculation of one type of culture bottle, a new syringe was used;

After inoculation, 250 µL of the remaining divided sample was used to verify the actual CFU by inoculating it onto the solid plate initially used for pure culture.

Culture bottles containing two or more CMBCS instruments were removed when a positive growth signal was detected. Bottles installed on the same day were then randomly selected by instrument and media type, and specimens drawn from the bottles were inoculated onto the medium initially used for pure culture. Once colonies appeared, they were identified using the MALDI Biotyper Smart System (Bruker Daltonics GmbH, Bremen, Germany).

2.5. Statistical Analysis

To ensure statistically valid comparisons, 30 paired tests per microorganism were conducted for each system, resulting in 90 paired culture bottle tests per strain. The performance of each system was evaluated based on time-to-growth detection. Because not all tests were performed on a single day, histograms of all results were gathered, and histograms of alarm time were generated to verify consistency and normality across test results. Statistical significance was defined as a p < 0.05, and all analyses were performed using R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

3. Results

The experimental schedule is presented in

Table S1. The dilution factor and CFU concentration of SSS for each bacterial strain are listed in

Table 1. Although the CFU levels varied by bacterial strain, the actual inoculated amounts were considered equivalent based on z-score assessments (

Table 1). Although some media for CFU verification showed no colony growth (

Figure S1–6 show the actual inoculation images), all culture bottles showed positive growth signals. Confirmation of growth indicated that all strains inoculated on the same day were accurately identified as the intended strains.

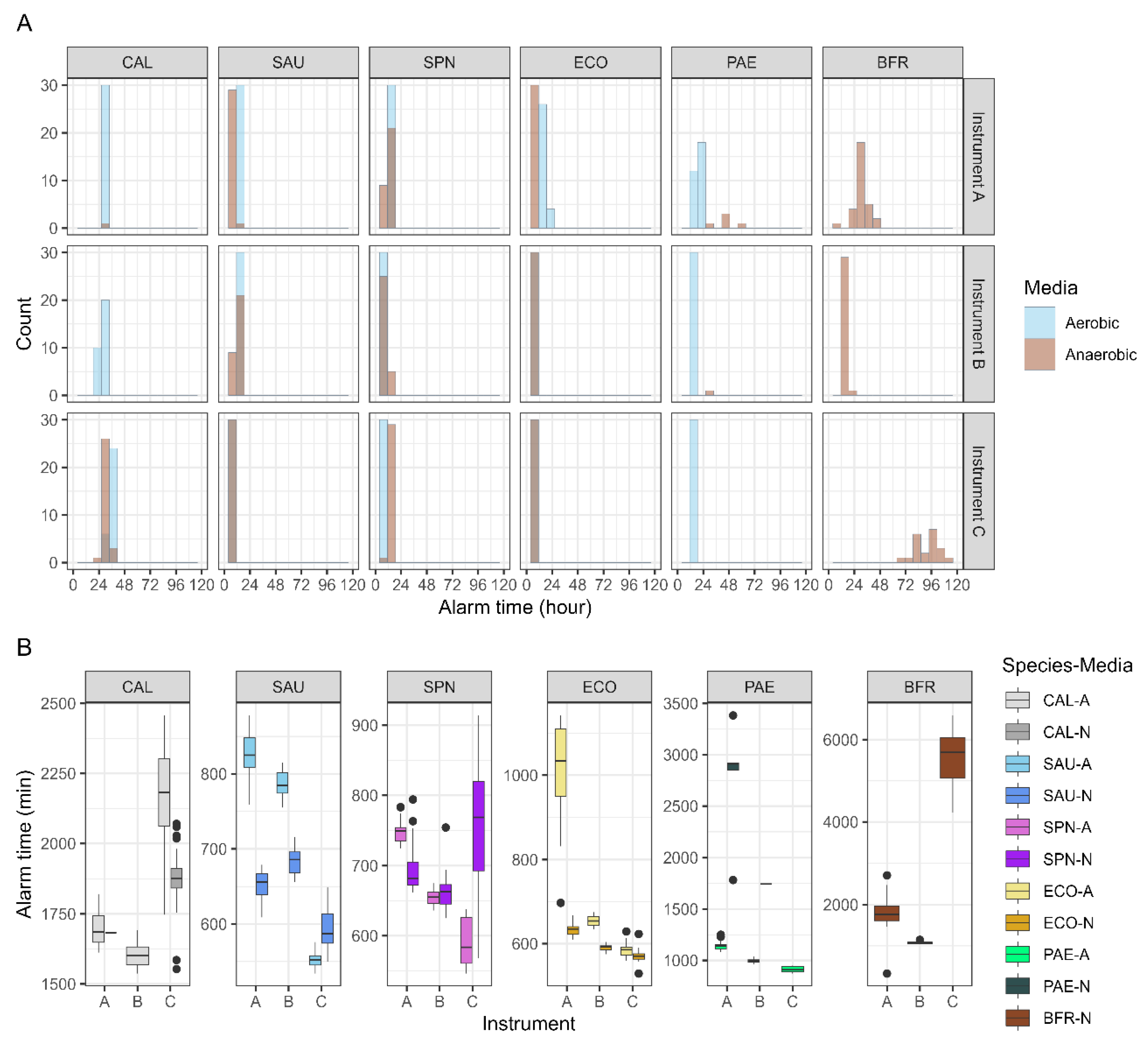

SAU, SPN, and ECO grew in both aerobic and anaerobic media across all instruments. Consistently, among the three systems, PAE grew in all aerobic media, whereas BFR grew exclusively in anaerobic media. CAL grew in both aerobic and anaerobic bottles only in HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.), whereas it grew solely in aerobic media in the other two systems. For BFR, growth alarm time showed high reproducibility only in BACTEC™ FX (BD), with the other two instruments displaying distributions with low kurtosis (

Figure 1A). SAU and ECO exhibited faster growth alarm times in anaerobic media for all instruments, whereas SPN exhibited faster growth alarm times in aerobic media. CAL cultured in Hubix N (HUFIT Inc.) displayed faster growth alarm times than CAL cultured in Hubix A (HUFIT Inc.) (

Figure 1B).

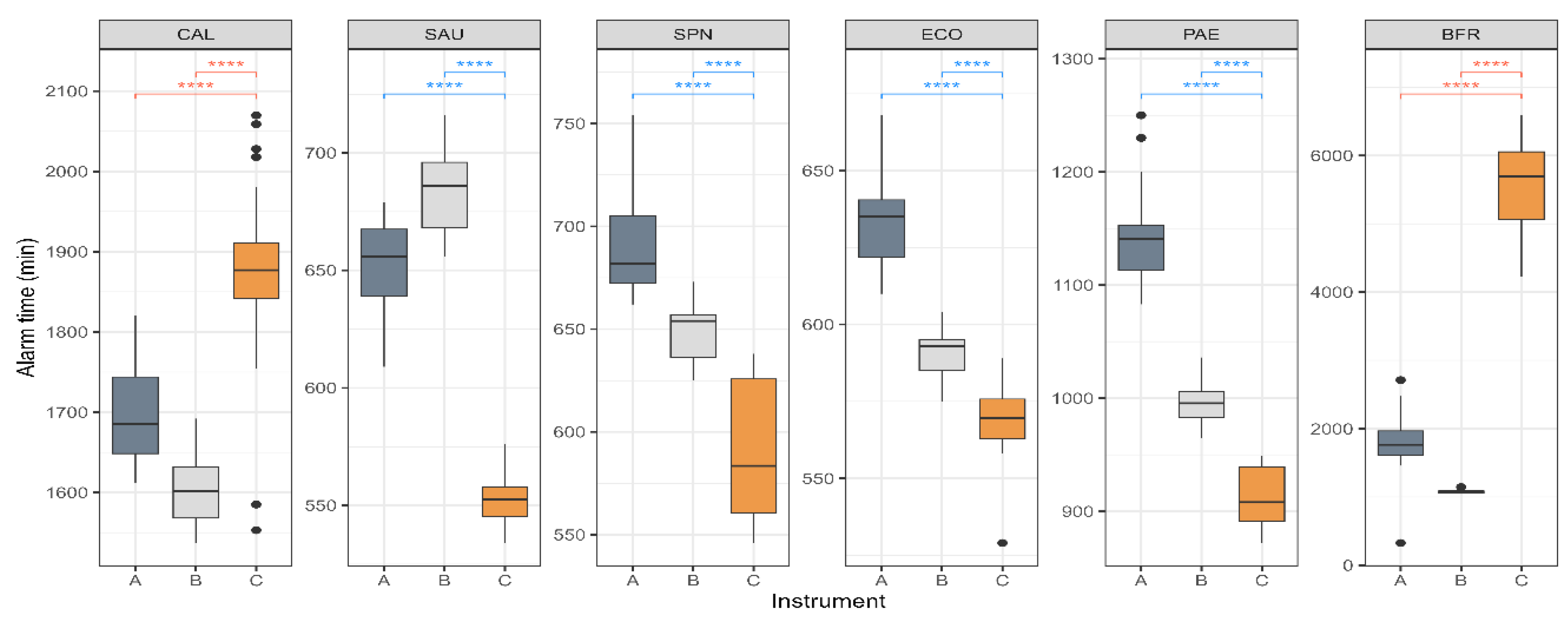

Blood cultures were performed in aerobic and anaerobic bottles. If either bottle signal is positive, the identification of the infectious pathogen can proceed more rapidly. For each strain, only the earliest growth alarm time from each pair was selected for comparison (

Figure 2). The strains representing gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria, SAU, SPN, ECO, and PAE, demonstrated growth alarm times that were approximately 2 h faster in HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.) than in the other systems. Although CAL grew in both media types only in the HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.), its growth alarm time was 200–300 min slower than in the other two instruments. Notably, the BFR exhibited a delay of approximately 4,000 min.

4. Discussion

Appropriate sepsis management begins with the rapid identification of pathogens within the bloodstream [

2]. This action of “identification” with medical significance required specific prerequisite criteria. The key prerequisites include coherence, where different instruments yield the same result under identical experimental conditions; consistency, reflected in repeatable results when detecting a specified concentration of bacteria; and plausibility, ensuring that the pathogens present in the specimen are invariably detected [

18,

19]. In this study, three core principles were prioritized. To shorten the experimental time, it would be sufficient to test all 30 specimens of a single strain on one instrument; however, we simultaneously tested identical SSS across at least two different instruments to ensure coherence. Following inoculation in separate media, we re-inoculated the remaining SSS to verify the CFU and maintain consistency. For samples that indicated the growth of microorganisms, the inoculated strains were identified to establish plausibility.

Numerous microorganisms have the potential to cause infections. However, the WHO prioritized certain infectious syndromes and tracked eight core pathogens through focused surveillance [

20]. Among the pathogens identified in the bloodstream, SAU, SPN, and ECO were the key isolates. In South Korea, PAE constitutes approximately 1.7% of gram-negative bacterial bloodstream infections, which is particularly important due to its multidrug resistance, positioning it alongside SAU, SPN, and ECO as persistently monitored sepsis pathogens [

12,

13]. The HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.) showed particular strength in detecting the growth of these four bacteria up to 2 h faster than the two alternative devices (

Figure 2). While this advantage might not have been universally aligned with other countries’ priorities, the CMBCS’s ability to rapidly detect bacteria significant to its developing country was noteworthy and deserving of attention.

The WHO formally highlighted the need to address blood infections caused by

Candida spp., with South Korea participating in this global initiative [

21]. Won et al. identified

Candida spp. as the fifth most common cause of bloodstream infections, and CAL with

C. tropicalis,

C. glabrata, and

C. parapsilosis was frequently observed, particularly in individuals aged > 60 [

22]. Although Candida spp. generally grow well in aerobic CMBCS bottles [

5,

23], HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.) detected CAL in both aerobic and anaerobic bottles (

Figure 1A), albeit with a 4-h delay compared to other systems (

Figure 1B). The growth of CAL in the anaerobic media suggests an expanded environmental capacity for other

Candida spp. to grow in CMBCS, thereby enhancing their identification potential in clinical laboratories. However, delayed identification compared to current equipment highlights a notable limitation.

BFR, an obligate anaerobe, requires an anaerobic environment for cultivation and is known to grow well on blood agar plates [

24]. Menchinelli et al. also used donated human blood to culture BFR with various CMBCS, and typical growth was observed after 30 h [

4]. In this study, SSS prepared with NS rather than with blood was used to conduct a comparative experiment. The BACTEC™ FX (BD) and BacT/Alert

® 3D (bioMérieux) systems showed growth alarm times within 2,000 min, whereas the HubCentra84 (HUFIT Inc.) took approximately 5,000 min to generate a growth alarm (

Figure 2). BFR was identified as a high-prevalence clinical anaerobe in multiple institutions across South Korea, with a notably high associated mortality rate [

25,

26]. Although rapid growth alarm times have been confirmed for major clinical pathogens, extending the detection time for BFR remains a critical challenge.

This study has some limitations. First, a variety of bacteria were not compared. In the modern era, with an aging population and a large number of therapeutically or pathogenically immunosuppressed patients, clinical laboratories have encountered a completely different spectrum of pathogens. Although six representative microorganisms were included, evaluating the utility of CMBCS in contemporary clinical laboratories would have required testing a greater number of pathogens. Second, uniform CFU concentrations across the various samples were not tested. Although efforts have been made to compare consistent CFU levels among CMBCS, identical CFU counts across bacterial strains have not been achieved. This limits the accuracy of the performance comparison for each strain. The detection limit of the system was determined by calibrating the dilution factor using a wide range of CFU concentrations. Third, actual blood samples from patients with sepsis were not used. Clinical blood specimens offer an ideal means to compare CMBCS performance. However, collecting an additional 20 mL of blood from patients with septic shock for experimental purposes raises ethical concerns. By further improving the performance of the CMBCS and confronting real-world assessments in clinical fields, rigorous performance evaluation by end users could be achieved.

5. Conclusions

Our study compared the performance of existing CMBCS with that of a newly developed automated blood culture system. Efforts were made to ensure the coherence, consistency, and plausibility of comparative results. The findings revealed that the new CMBCS demonstrated earlier growth detection for clinically common bacteria, such as SAU, SPN, ECO, and PAE, compared with other systems. However, further performance improvements are deemed necessary for CAL, a pathogen of recent concern, and BFR, which is frequently encountered in clinical laboratories. The emergence of novel systems, the advancement of stagnant performance, and the recognition of limitations are all expected to contribute significantly to improvements in clinical microbiology.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Test schedules; Figure S1: Verification of colony-forming units of Candida albicans; Figure S2: Verification of colony-forming units of Staphylococcus aureus; Figure S3: Verification of the colony-forming unit of Streptococcus pneumoniae; Figure S4: Verification of the colony-forming units of Escherichia coli; Figure Colony-forming unit verification of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: title; Figure S6: Verification of colony-forming units of Bacteroides fragilis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.U. and K.A.; methodology, K.A.; software, S.H.; validation, Y.U.; formal analysis, K.A.; investigation, K.A.; resources, D.M.S.; data curation, K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, K.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.U. and K.A.; visualization, K.A. and T.L.; supervision, K.A.; project administration, Y.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (approval no. CR324334; Wonju-si, South Korea).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this research are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Han, X.; Spicer, A.; Carey, K.A.; Gilbert, E.R.; Laiteerapong, N.; Shah, N.S.; Winslow, C.; Afshar, M.; Kashiouris, M.G.; Churpek, M.M. Identifying high-risk subphenotypes and associated harms from delayed antibiotic orders and delivery. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 49, 1697–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seymour, C.W.; Gesten, F.; Prescott, H.C.; Friedrich, M.; Iwashyna, T.J.; Phillips, G.S.; Lemeshow, S.; Osborn, T.; Terry, K.M.; Levy, M.M. Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2235–2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, M.R.; Murray, P. R. Historical evolution of automated blood culture systems. Clin. Microbiol. Newsl. 1993, 15, 105–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menchinelli, G.; Liotti, F.M.; Fiori, B.; Angelis, G.D.; D’Inzeo, T.; Giordano, L.; Posteraro, B.; Sabbatucci, M.; Sanguinetti, M.; Spanu, T. In vitro evaluation of BACT/ALERT® VIRTUO®, BACT/ALERT 3D®, and BACTEC™ FX automated blood culture systems for detection of microbial pathogens using simulated human blood samples. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Sun, J.; Pan, S.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Sun, X.; Xu, H.; Ming, L. Comparison of the performance of three blood culture systems in a Chinese tertiary-care hospital. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2019, 9, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, L.; Vermoesen, T.; Genbrugge, E.; Natale, A.; Franquesa, C.; Gleeson, B.; Ferreyra, C.; Dailey, P.; Jacobs, J. Affordable blood culture systems from China: in vitro evaluation for use in resource-limited settings. EBioMedicine 2024, 101, 105004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombelet, S.; Natale, A.; Ronat, J.B.; Vandenberg, O.; Jacobs, J.; Hardy, L. Considerations in evaluating equipment-free blood culture bottles: a short protocol for use in low-resource settings. PLoS One 2021, 17, e0267491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ombelet, S.; Barbé, B.; Affolabi, D.; Ronat, J.B.; Lompo, P.; Lunguya, O.; Jacobs, J.; Hardy, L. Best practices of blood cultures in low- and middle-income countries. Front. Med. 2019, 6, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uh, Y.; Jang, I.H.; Park, S.D.; Kim, K.S.; Seo, D.M.; Yoon, K.J.; Choi, H.K.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, H.Y. Factors influencing the false positive signals of continuous monitoring blood culture system. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 17, 58–64 [Korean]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, K.; Ahn, J.H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.H.; Hwang, G.Y.; Yoo, G.; Yoon, K.J.; Uh, Y. A new bacterial growth graph pattern analysis to improve positive predictive value of continuous monitoring blood culture system. J. Med. Syst. 2018, 42, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yoon, E.J.; Kim, D.; Jeong, S.H.; Won, E.J.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, J.H.; Shin, K.S.; Kim, Y.A.; et al. Antimicrobial resistance of major clinical pathogens in South Korea, May 2016 to April 2017: first one-year report from Kor-GLASS. Euro Surveill. 2018, 23, 1800047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Park, J.S.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.J.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, Y.A.; Uh, Y.; Kim, S.H.; Shin, J.H.; Jeong, S.H.; et al. Standardization of an antimicrobial resistance surveillance network through data management. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1411145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Yoon, E.J.; Hong, J.S.; Choi, M.H.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.R.; Kim, Y.A.; Uh, Y.; Shin, K.S.; Shin, J.H.; et al. Major bloodstream infection-causing bacterial pathogens and their antimicrobial resistance in South Korea, 2017–2019: phase I report from Kor-GLASS. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 799084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, J. The nephelometer: an instrument for estimating the number of bacteria in suspensions used for calculating the opsonic index and for vaccines. JAMA 1907, 14, 1176–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zapata, A.; Ramirez-Arcos, S. A comparative study of McFarland turbidity standars and the densimat photometer to determine bacterial cell density. Curr. Microbiol. 2015, 70, 907–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reier-Nilsen, T.; Farstad, T.; Nakstad, B.; Lauvrak, V.; Steinbakk, M. Comparison of broad range 16S rDNA PCR and conventional blood culture for diagnosis of sepsis in the newborn: a case control study. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagupsky, P.; Nolte, F.S. Quantitative aspects of septicemia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1990, 3, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Ball, E.; Fox, C.E.; Meads, C. Systematic reviews to evaluate causation: an overview of methods and application. Evid. Based Med. 2012, 17, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gvozdenović, E.; Malvisi, L.; Cinconze, E.; Vansteelandt, S.; Nakanwagi, P.; Aris, E.; Rosillon, D. Causal inference concepts applied to three observational studies in the context of vaccine development: from theory to practice. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2021, 21, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global antimicrobial resistance and use surveillance system (GLASS) report 2022. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 10. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062702.

- Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) early implementation protocol for the inclusion of Candida spp.. World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 5. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-WSI-AMR-2019.4.

- Won, E.J.; Choi, M.J.; Jeong, S.H.; Kim, D.; Shin, K.S.; Shin, J.H.; Kim, Y.R.; Kim, H.S.; Kim, Y.A.; Uh, Y.; et al. Nationwide surveillance of antifungal resistance of Candida bloodstream isolates in South Korean Hospitals: two year report from Kor-GLASS. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, K.W.; Lim, Y.K.; Lee, M.K. Comparison of new and old BacT/ALERT aerobic bottles for detection of Candida species. PLos One 2023, 18, e0288674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, T.; Aziz, H. Bacteroides fragilis: a case study of bacteremia and septic arthritis. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2009, 22, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roh, K.H.; Kim, S.; Kim, C.K.; Yum, J.H.; Kim, M.S.; Yong, D.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.M.; Chong, Y. Resistance trends of Bacteroides fragilis group over an 8-year period, 1997–2004, in Korea. Korean J. Lab. Med. 2009, 29, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Choi, J.Y.; Young, D.; Jeong, S.H. Recent trends of anaerobic bacteria isolated from clinical specimens and clinical characteristics of anaerobic bacteremia. Infect. Chemother. 2009, 41, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).