Submitted:

01 November 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

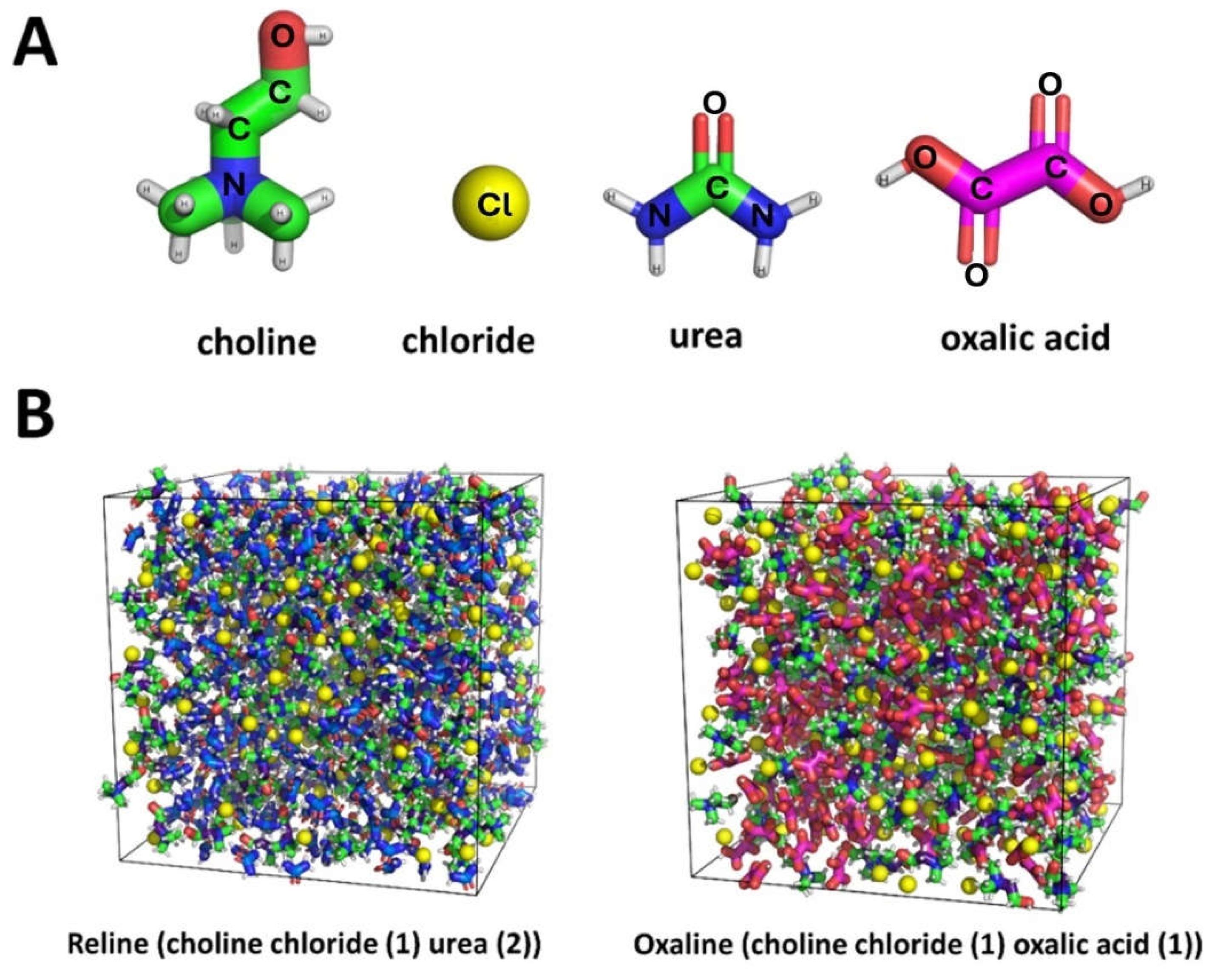

2. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

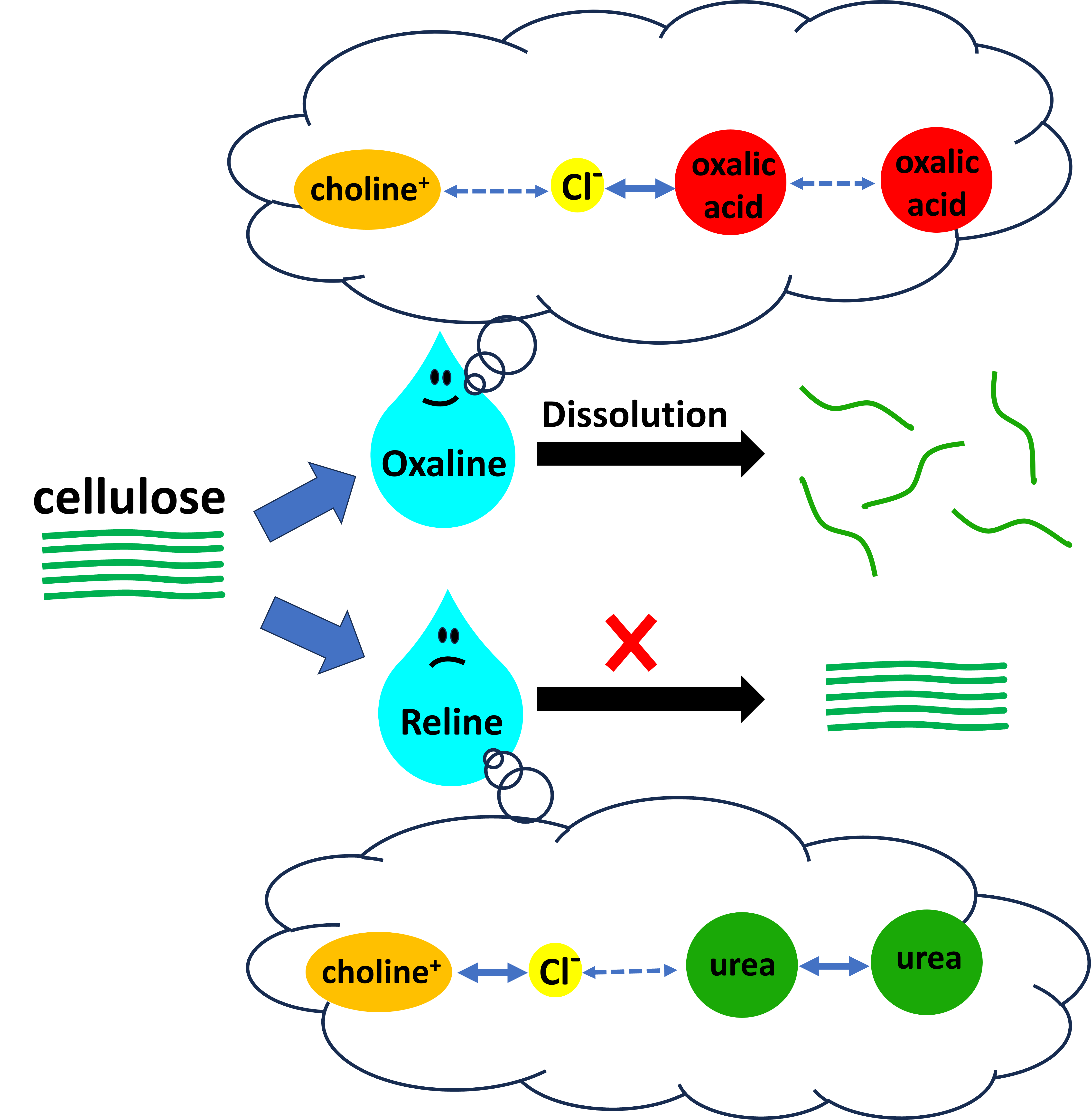

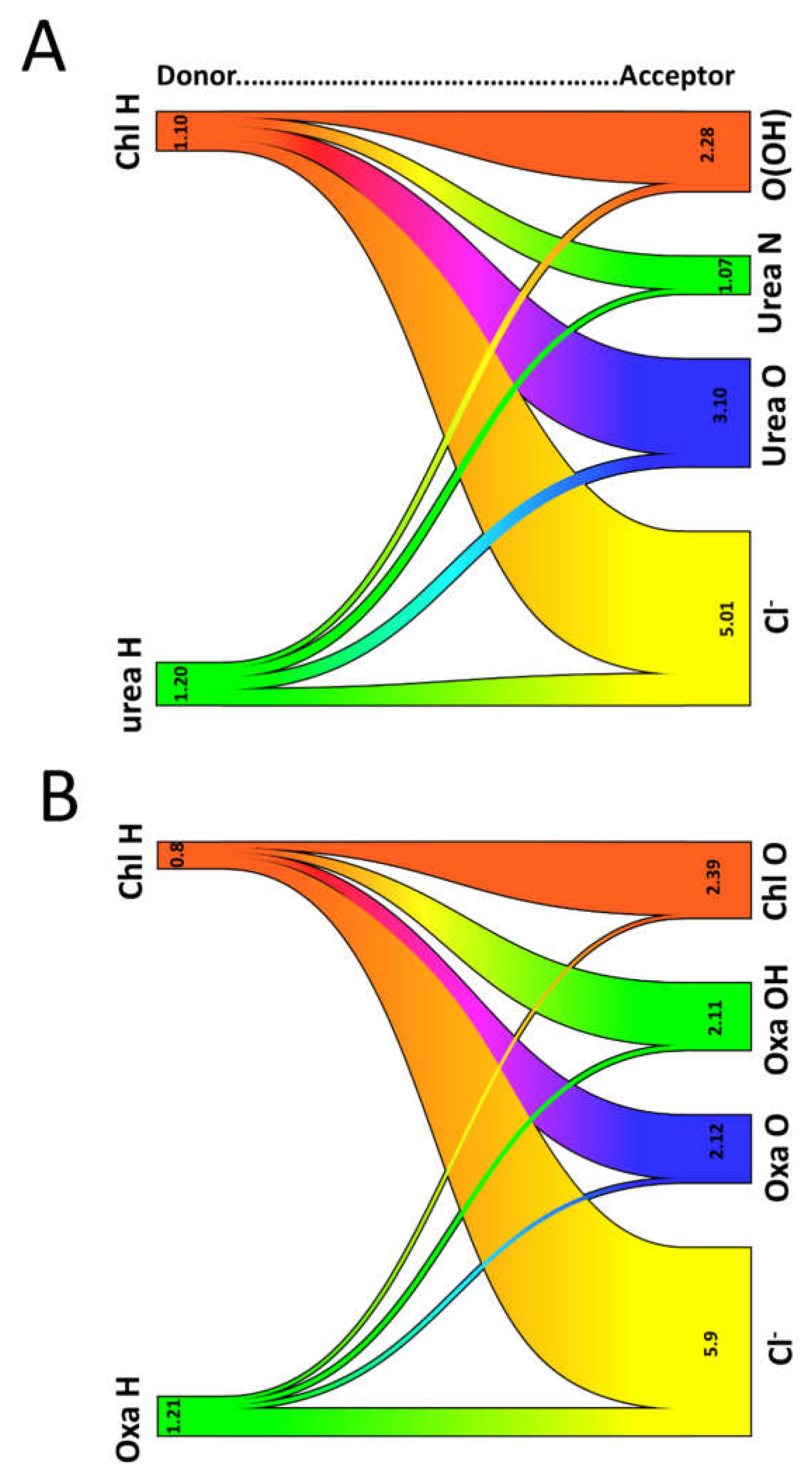

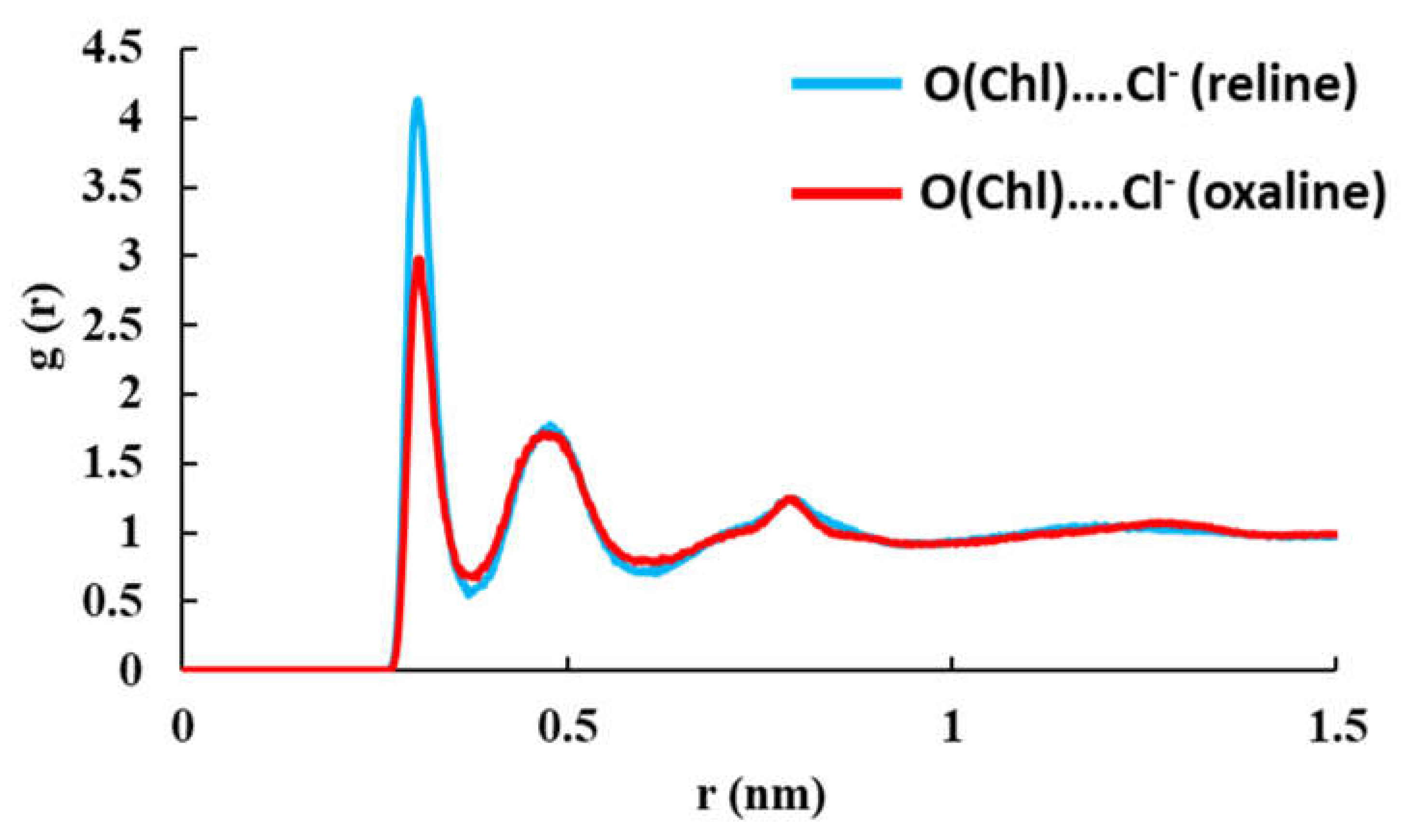

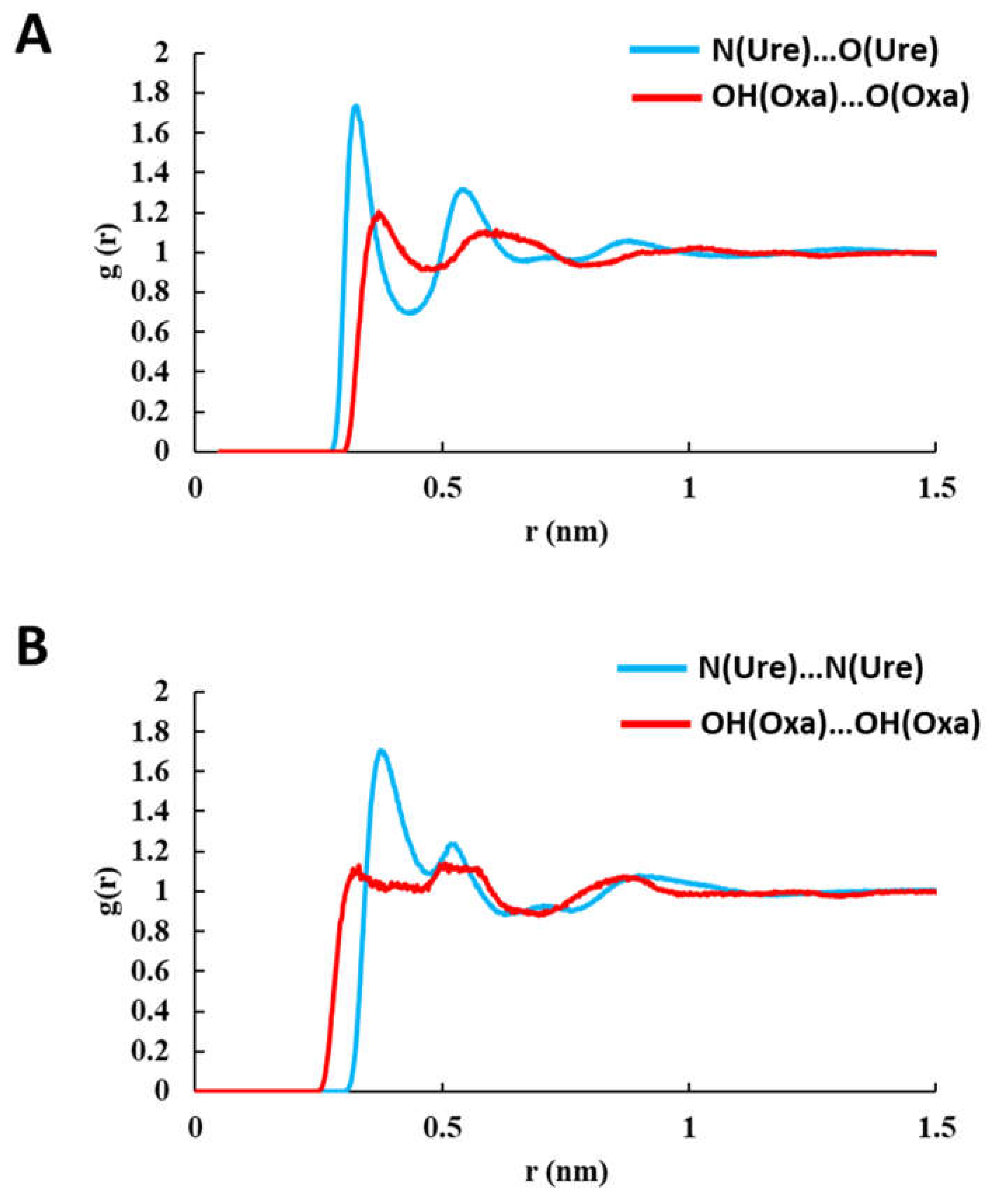

3.1. Hydrogen Bonding Network in Pure Solvents

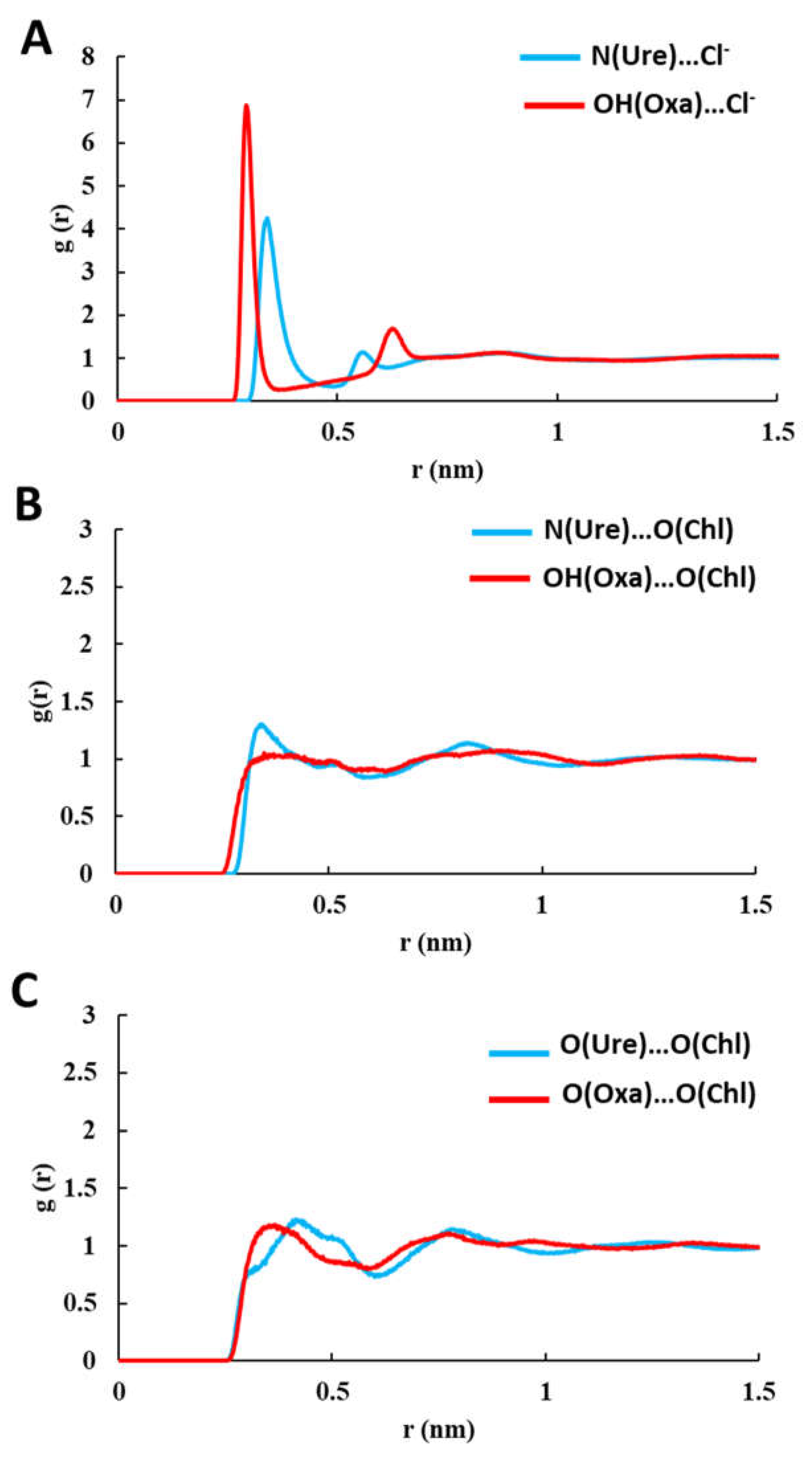

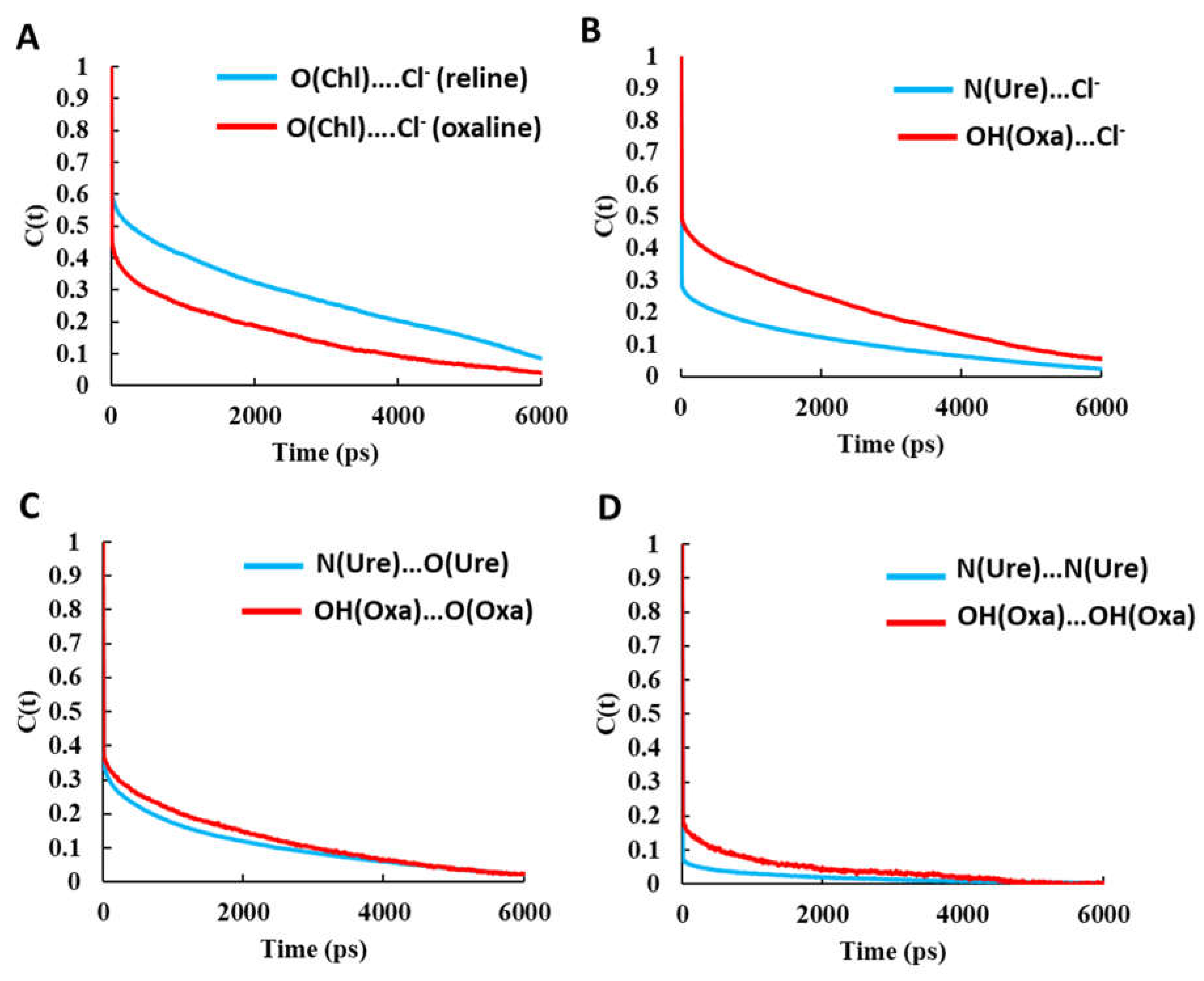

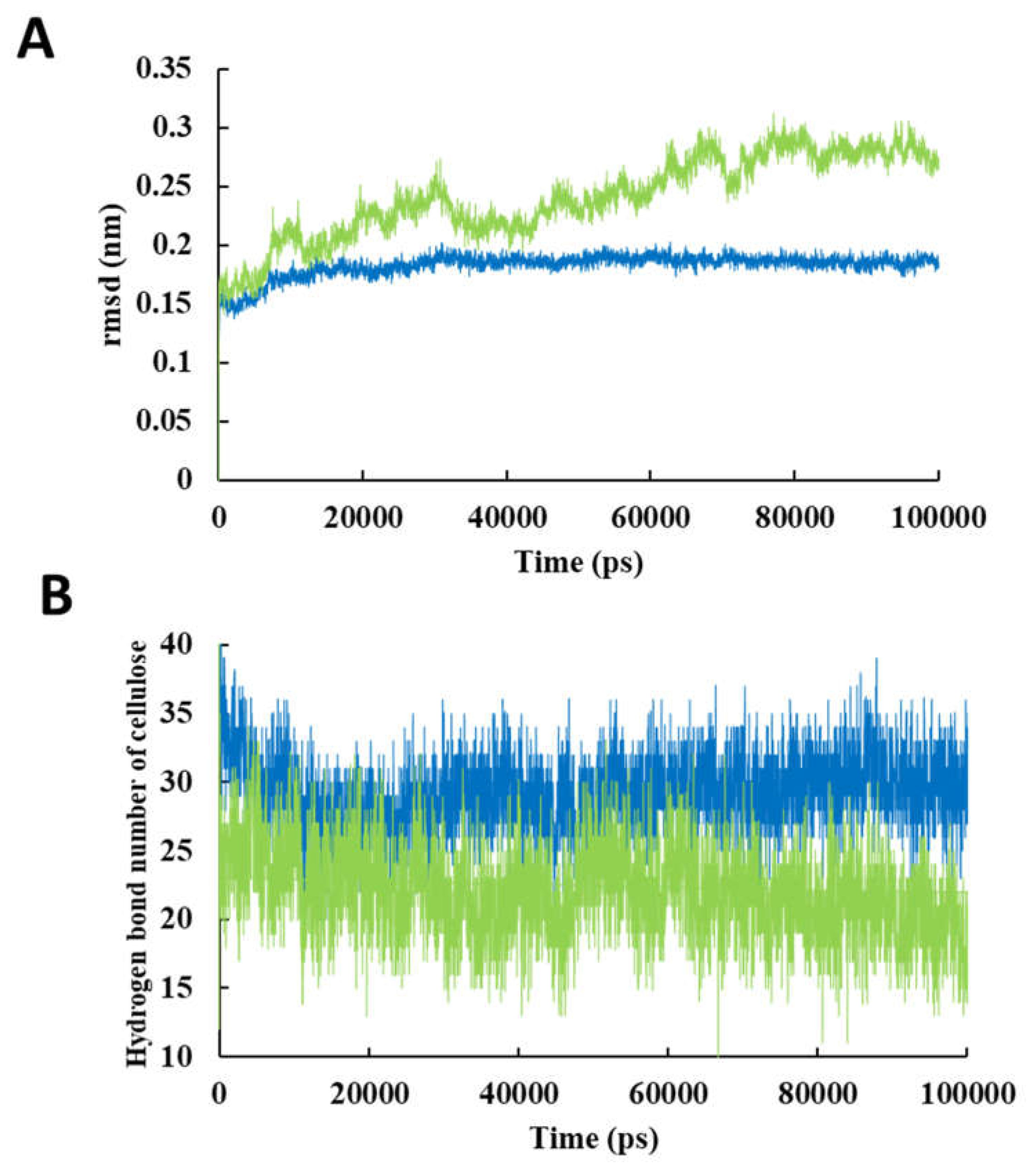

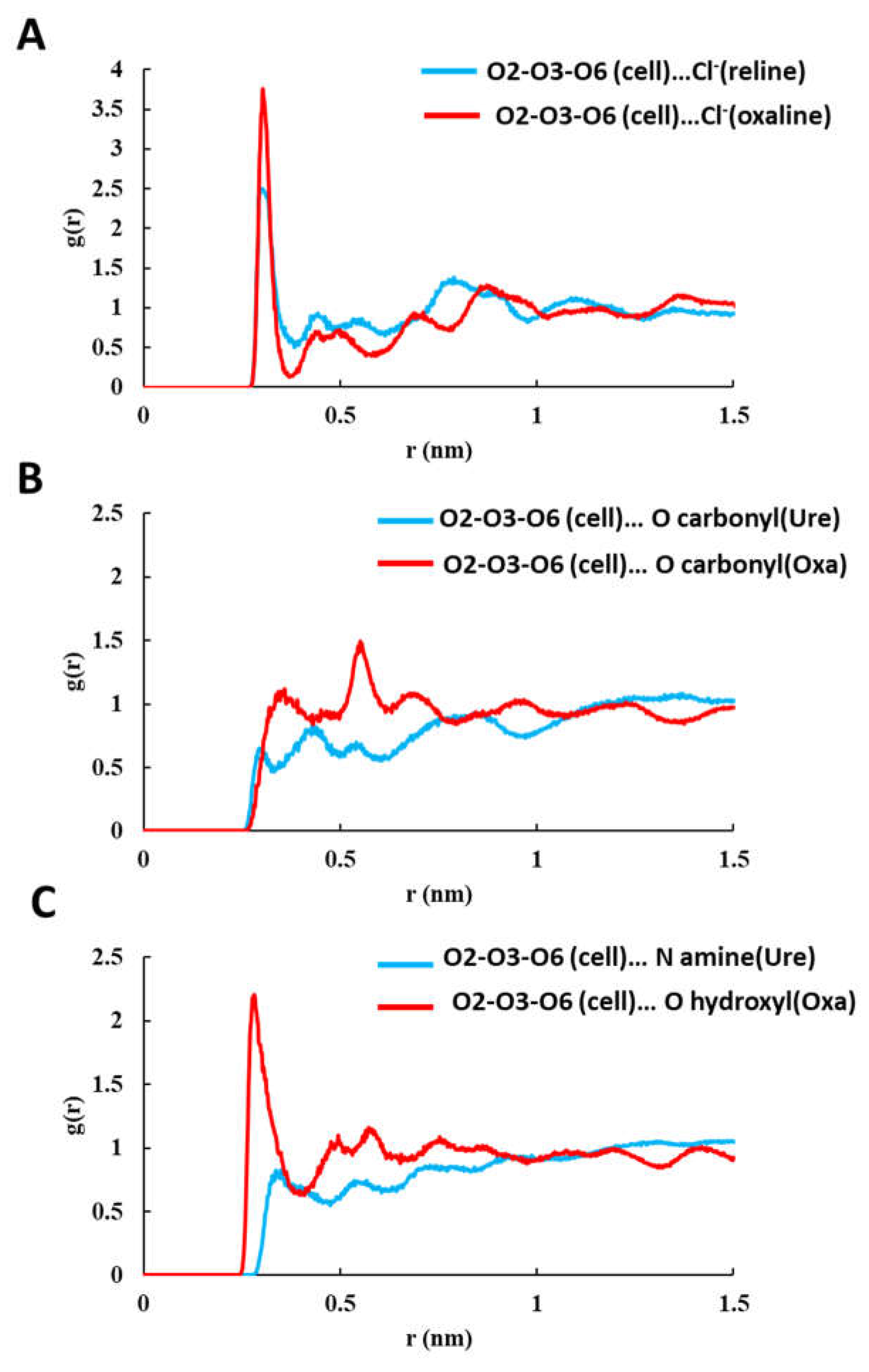

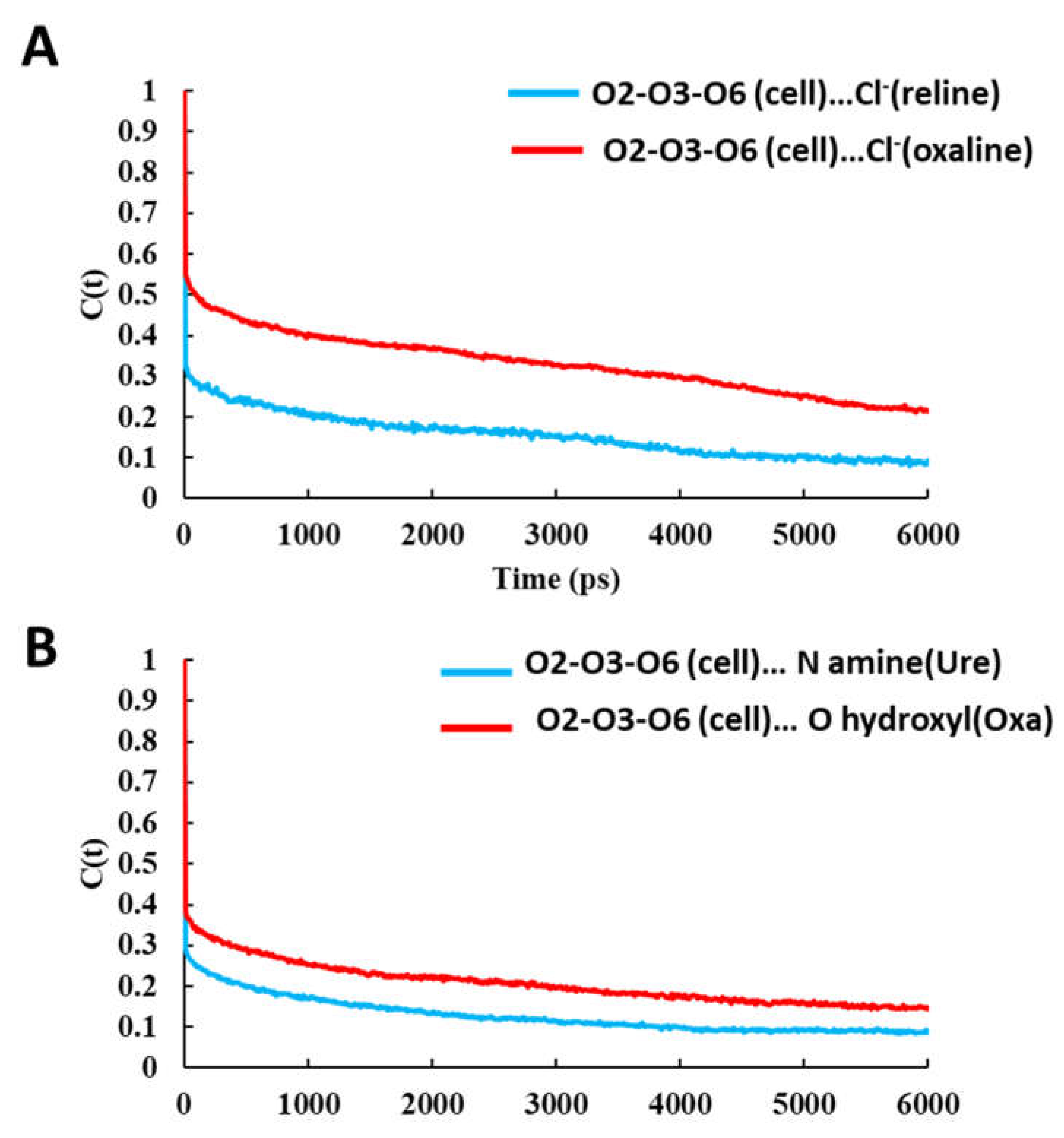

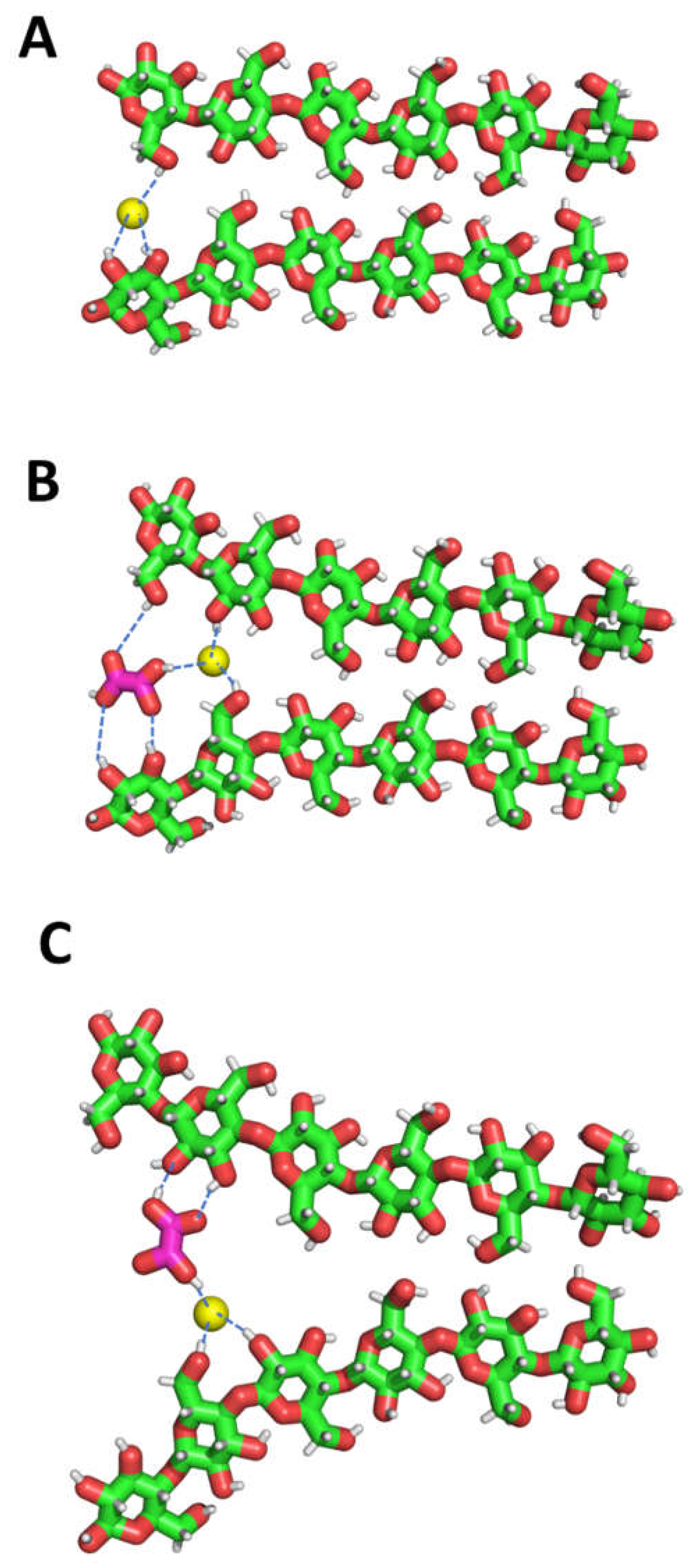

3.2. Cellulose-DES Interactions

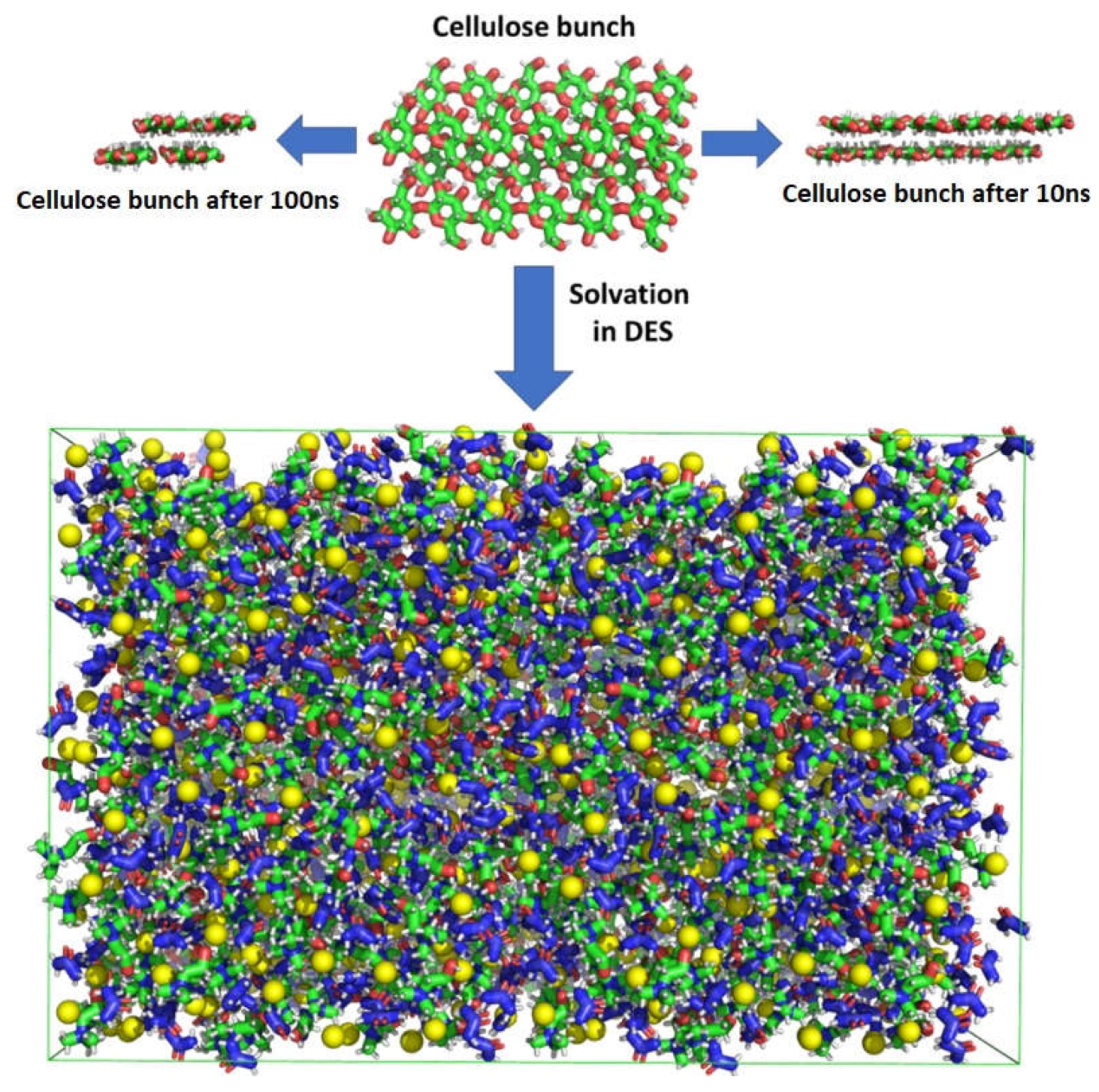

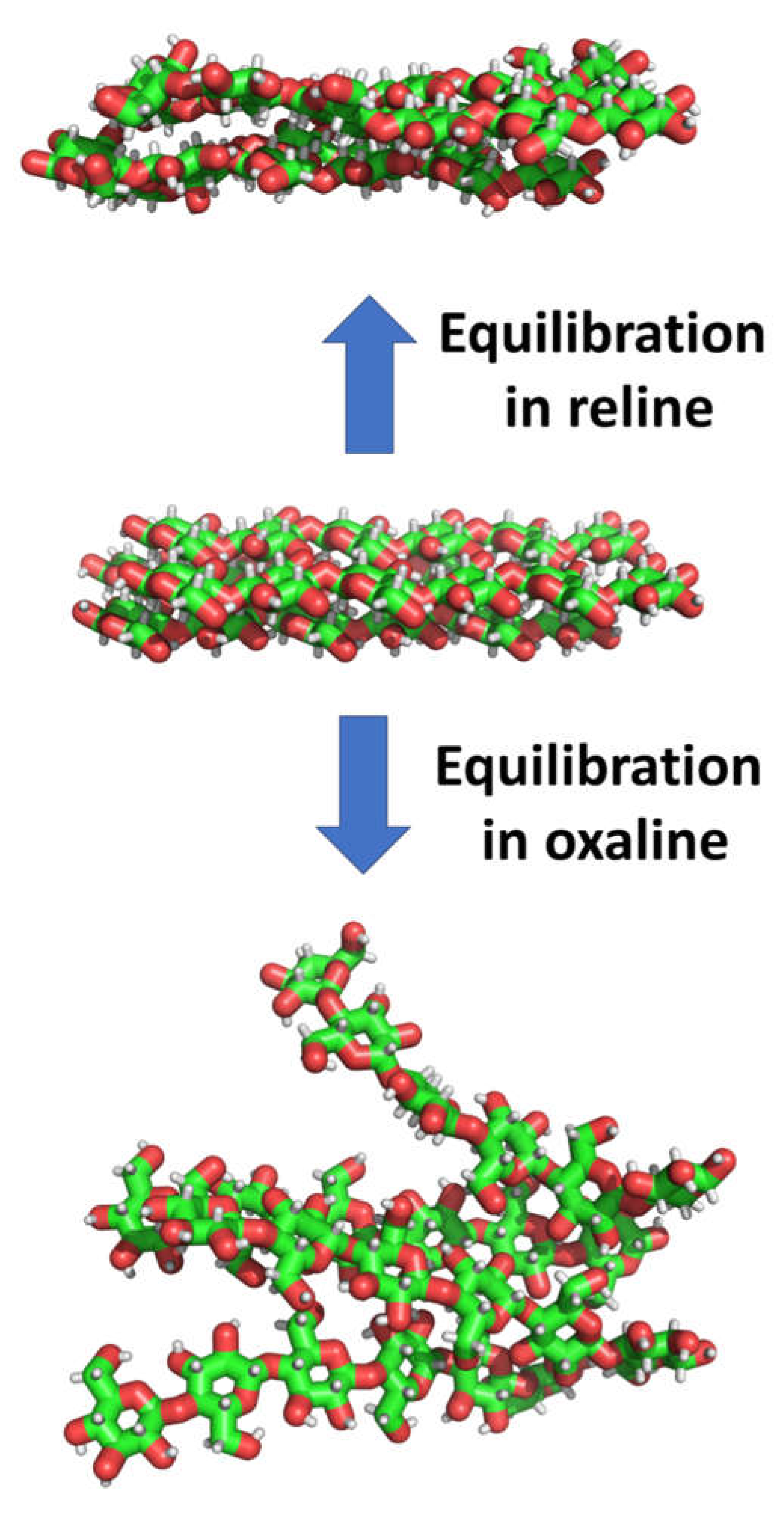

4. Molecular Mechanism of Cellulose Dissolution in Oxaline

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- D. Klemm, B. Heublein, H.-P. Fink, A. Bohn, Cellulose: Fascinating Biopolymer and Sustainable Raw Material, Angewandte Chemie International Edition 44(22) (2005) 3358-3393.

- J.T. McNamara, J.L. Morgan, J. Zimmer, A molecular description of cellulose biosynthesis, Annu Rev Biochem 84 (2015) 895-921. [CrossRef]

- S. Acharya, S. Liyanage, P. Parajuli, S.S. Rumi, J.L. Shamshina, N. Abidi, Utilization of Cellulose to Its Full Potential: A Review on Cellulose Dissolution, Regeneration, and Applications, Polymers (Basel) 13(24) (2021). [CrossRef]

- A.J. Sayyed, N.A. Deshmukh, D.V. Pinjari, A critical review of manufacturing processes used in regenerated cellulosic fibres: viscose, cellulose acetate, cuprammonium, LiCl/DMAc, ionic liquids, and NMMO based lyocell, Cellulose 26(5) (2019) 2913-2940. [CrossRef]

- B. Medronho, B. Lindman, Brief overview on cellulose dissolution/regeneration interactions and mechanisms, Advances in Colloid and Interface Science 222 (2015) 502-508. [CrossRef]

- A. Isogai, R.H. Atalla, Dissolution of Cellulose in Aqueous NaOH Solutions, Cellulose 5(4) (1998) 309-319. [CrossRef]

- J. Cai, L. Zhang, Rapid Dissolution of Cellulose in LiOH/Urea and NaOH/Urea Aqueous Solutions, Macromolecular Bioscience 5(6) (2005) 539-548. [CrossRef]

- A.-L. Dupont, Cellulose in lithium chloride/N,N-dimethylacetamide, optimisation of a dissolution method using paper substrates and stability of the solutions, Polymer 44(15) (2003) 4117-4126. [CrossRef]

- S. Zhang, F.-X. Li, J.-y. Yu, Y.-L. Hsieh, Dissolution behaviour and solubility of cellulose in NaOH complex solution, Carbohydrate Polymers 81(3) (2010) 668-674. [CrossRef]

- L. Soh, M.J. Eckelman, Green Solvents in Biomass Processing, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 4(11) (2016) 5821-5837.

- R.P. Swatloski, S.K. Spear, J.D. Holbrey, R.D. Rogers, Dissolution of cellose with ionic liquids, Journal of the American chemical society 124(18) (2002) 4974-4975.

- H. Wang, G. Gurau, R.D. Rogers, Ionic liquid processing of cellulose, Chemical Society Reviews 41(4) (2012) 1519-1537.

- S. Zhu, Y. Wu, Q. Chen, Z. Yu, C. Wang, S. Jin, Y. Ding, G. Wu, Dissolution of cellulose with ionic liquids and its application: a mini-review, Green Chemistry 8(4) (2006) 325-327. [CrossRef]

- M. Isik, H. Sardon, D. Mecerreyes, Ionic liquids and cellulose: dissolution, chemical modification and preparation of new cellulosic materials, Int J Mol Sci 15(7) (2014) 11922-40. [CrossRef]

- C. Verma, A. Mishra, S. Chauhan, P. Verma, V. Srivastava, M.A. Quraishi, E.E. Ebenso, Dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquids and their mixed cosolvents: A review, Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 13 (2019) 100162. [CrossRef]

- J. Flieger, M. Flieger, Ionic Liquids Toxicity—Benefits and Threats, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020. [CrossRef]

- D. Coleman, N. Gathergood, Biodegradation studies of ionic liquids, Chemical Society reviews 39 (2010) 600-37.

- J. Zhao, M.R. Wilkins, D. Wang, A review on strategies to reduce ionic liquid pretreatment costs for biofuel production, Bioresource Technology 364 (2022) 128045. [CrossRef]

- L. Chen, M. Sharifzadeh, N. Mac Dowell, T. Welton, N. Shah, J.P. Hallett, Inexpensive ionic liquids: [HSO4]−-based solvent production at bulk scale, Green Chemistry 16(6) (2014) 3098-3106.

- S.K. Singh, A.W. Savoy, Ionic liquids synthesis and applications: An overview, Journal of Molecular Liquids 297 (2020) 112038. [CrossRef]

- A.P. Abbott, D. Boothby, G. Capper, D.L. Davies, R.K. Rasheed, Deep Eutectic Solvents Formed between Choline Chloride and Carboxylic Acids: Versatile Alternatives to Ionic Liquids, Journal of the American Chemical Society 126(29) (2004) 9142-9147. [CrossRef]

- B. Nian, X. Li, Can deep eutectic solvents be the best alternatives to ionic liquids and organic solvents: A perspective in enzyme catalytic reactions, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 217 (2022) 255-269. [CrossRef]

- A.P. Abbott, G. Capper, D.L. Davies, R.K. Rasheed, V. Tambyrajah, Novel solvent properties of choline chloride/urea mixtures, Chemical Communications (1) (2003) 70-71. [CrossRef]

- A. Paiva, R. Craveiro, I. Aroso, M. Martins, R.L. Reis, A.R.C. Duarte, Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents – Solvents for the 21st Century, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2(5) (2014) 1063-1071. [CrossRef]

- C. Florindo, F. Lima, B.D. Ribeiro, I.M. Marrucho, Deep eutectic solvents: overcoming 21st century challenges, Current Opinion in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 18 (2019) 31-36.

- M. Pätzold, S. Siebenhaller, S. Kara, A. Liese, C. Syldatk, D. Holtmann, Deep Eutectic Solvents as Efficient Solvents in Biocatalysis, Trends in Biotechnology 37(9) (2019) 943-959. [CrossRef]

- P. Xu, G.W. Zheng, M.H. Zong, N. Li, W.Y. Lou, Recent progress on deep eutectic solvents in biocatalysis, Bioresour Bioprocess 4(1) (2017) 34. [CrossRef]

- D.V. Wagle, H. Zhao, G.A. Baker, Deep Eutectic Solvents: Sustainable Media for Nanoscale and Functional Materials, Accounts of Chemical Research 47(8) (2014) 2299-2308. [CrossRef]

- T. Gu, M. Zhang, T. Tan, J. Chen, Z. Li, Q. Zhang, H. Qiu, Deep eutectic solvents as novel extraction media for phenolic compounds from model oil, Chemical Communications 50(79) (2014) 11749-11752. [CrossRef]

- R.B. Leron, M.-H. Li, Solubility of carbon dioxide in a choline chloride–ethylene glycol based deep eutectic solvent, Thermochimica Acta 551 (2013) 14-19. [CrossRef]

- D. Yang, M. Hou, H. Ning, J. Zhang, J. Ma, G. Yang, B. Han, Efficient SO2 absorption by renewable choline chloride–glycerol deep eutectic solvents, Green Chemistry 15(8) (2013) 2261-2265. [CrossRef]

- S. Sarmad, J.-P. Mikkola, X. Ji, Carbon Dioxide Capture with Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents: A New Generation of Sorbents, ChemSusChem 10(2) (2017) 324-352. [CrossRef]

- M. Zdanowicz, K. Wilpiszewska, T. Spychaj, Deep eutectic solvents for polysaccharides processing. A review, Carbohydrate Polymers 200 (2018) 361-380. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen, T. Mu, Application of deep eutectic solvents in biomass pretreatment and conversion, Green Energy & Environment 4(2) (2019) 95-115. [CrossRef]

- Z. Li, C. Liu, S. Hong, H. Lian, C. Mei, J. Lee, Q. Wu, M.A. Hubbe, M.-C. Li, Recent advances in extraction and processing of chitin using deep eutectic solvents, Chemical Engineering Journal 446 (2022) 136953. [CrossRef]

- D. Skowrońska, K. Wilpiszewska, Deep Eutectic Solvents for Starch Treatment, Polymers, 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Leroy, P. Decaen, P. Jacquet, G. Coativy, B. Pontoire, A.-L. Reguerre, D. Lourdin, Deep eutectic solvents as functional additives for starch based plastics, Green Chemistry 14(11) (2012) 3063-3066. [CrossRef]

- K. Wilpiszewska, D. Skowrońska, Evaluation of starch plasticization efficiency by deep eutectic solvents based on choline chloride, Journal of Molecular Liquids 384 (2023) 122210. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, S. Xu, G. Goksen, C. Yi, P. Shao, Chitosan films plasticized with choline-based deep eutectic solvents: UV shielding, antioxidant, and antibacterial properties, Food Hydrocolloids 135 (2023) 108196. [CrossRef]

- Y.-L. Chen, X. Zhang, T.-T. You, F. Xu, Deep eutectic solvents (DESs) for cellulose dissolution: a mini-review, Cellulose 26(1) (2019) 205-213. [CrossRef]

- H. Malaeke, M.R. Housaindokht, H. Monhemi, M. Izadyar, Deep eutectic solvent as an efficient molecular liquid for lignin solubilization and wood delignification, Journal of Molecular Liquids 263 (2018) 193-199. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, J. Lang, P. Lan, H. Yang, J. Lu, Z. Wang, Study on the Dissolution Mechanism of Cellulose by ChCl-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents, Materials (Basel) 13(2) (2020).

- H. Ren, C. Chen, S. Guo, D. Zhao, Q. Wang, Synthesis of a Novel Allyl-Functionalized Deep Eutectic Solvent to Promote Dissolution of Cellulose, BioResources 11 (2016). [CrossRef]

- H.V.D. Nguyen, R. De Vries, S.D. Stoyanov, Natural Deep Eutectics as a “Green” Cellulose Cosolvent, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 8(37) (2020) 14166-14178.

- V.I.B. Castro, F. Mano, R.L. Reis, A. Paiva, A.R.C. Duarte, Synthesis and Physical and Thermodynamic Properties of Lactic Acid and Malic Acid-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents, Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 63(7) (2018) 2548-2556. [CrossRef]

- A.P. Abbott, G. Capper, D.L. Davies, H.L. Munro, R.K. Rasheed, V. Tambyrajah, Preparation of novel, moisture-stable, Lewis-acidic ionic liquids containing quaternary ammonium salts with functional side chains, Chemical Communications (19) (2001) 2010-2011. [CrossRef]

- M. Akhlaghi Bagherjeri, H. Monhemi, A.N.M.A. Haque, M. Naebe, Molecular mechanism of cellulose dissolution in N-methyl morpholine-N-oxide: A molecular dynamics simulation study, Carbohydrate Polymers 323 (2024) 121433. [CrossRef]

- S.H. Vahidi, H. Monhemi, M. Hojjatipour, M. Hojjatipour, M. Eftekhari, M. Vafaeei, Supercritical CO2/Deep Eutectic Solvent Biphasic System as a New Green and Sustainable Solvent System for Different Applications: Insights from Molecular Dynamics Simulations, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 127(37) (2023) 8057-8065.

- D. Bedrov, J.-P. Piquemal, O. Borodin, A.D. MacKerell, Jr., B. Roux, C. Schröder, Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Ionic Liquids and Electrolytes Using Polarizable Force Fields, Chemical Reviews 119(13) (2019) 7940-7995. [CrossRef]

- S. Tsuzuki, W. Shinoda, H. Saito, M. Mikami, H. Tokuda, M. Watanabe, Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Ionic Liquids: Cation and Anion Dependence of Self-Diffusion Coefficients of Ions, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 113(31) (2009) 10641-10649. [CrossRef]

- T. Köddermann, D. Paschek, R. Ludwig, Molecular Dynamic Simulations of Ionic Liquids: A Reliable Description of Structure, Thermodynamics and Dynamics, ChemPhysChem 8(17) (2007) 2464-2470. [CrossRef]

- D. Tolmachev, N. Lukasheva, R. Ramazanov, V. Nazarychev, N. Borzdun, I. Volgin, M. Andreeva, A. Glova, S. Melnikova, A. Dobrovskiy, S.A. Silber, S. Larin, R.M. de Souza, M.C. Ribeiro, S. Lyulin, M. Karttunen, Computer Simulations of Deep Eutectic Solvents: Challenges, Solutions, and Perspectives, International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Atilhan, S. Aparicio, Molecular dynamics simulations of mixed deep eutectic solvents and their interaction with nanomaterials, Journal of Molecular Liquids 283 (2019) 147-154. [CrossRef]

- J.R. Perilla, B.C. Goh, C.K. Cassidy, B. Liu, R.C. Bernardi, T. Rudack, H. Yu, Z. Wu, K. Schulten, Molecular dynamics simulations of large macromolecular complexes, Curr Opin Struct Biol 31 (2015) 64-74. [CrossRef]

- S.A. Hollingsworth, R.O. Dror, Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All, Neuron 99(6) (2018) 1129-1143.

- H. Monhemi, M.R. Housaindokht, A.A. Moosavi-Movahedi, M.R. Bozorgmehr, How a protein can remain stable in a solvent with high content of urea: insights from molecular dynamics simulation of Candida antarctica lipase B in urea : choline chloride deep eutectic solvent, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 16(28) (2014) 14882-14893. [CrossRef]

- H. Monhemi, M.R. Housaindokht, A. Nakhaei Pour, Effects of Natural Osmolytes on the Protein Structure in Supercritical CO2: Molecular Level Evidence, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 119(33) (2015) 10406-10416. [CrossRef]

- H. Monhemi, M.R. Housaindokht, M.R. Bozorgmehr, M.S.S. Googheri, Enzyme is stabilized by a protection layer of ionic liquids in supercritical CO2: Insights from molecular dynamic simulation, The Journal of Supercritical Fluids 69 (2012) 1-7. [CrossRef]

- M. Mohtashami, J. Fooladi, A. Haddad-Mashadrizeh, M.R. Housaindokht, H. Monhemi, Molecular mechanism of enzyme tolerance against organic solvents: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation, International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 122 (2019) 914-923. [CrossRef]

- H. Monhemi, H.N. Hoang, D.M. Standley, T. Matsuda, M.R. Housaindokht, The protein-stabilizing effects of TMAO in aqueous and non-aqueous conditions, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 24(35) (2022) 21178-21187. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. Liu, J. Wang, S. Zhang, Insight into the Cosolvent Effect of Cellulose Dissolution in Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquid Systems, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 117(30) (2013) 9042-9049. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, K.L. Sale, B.A. Simmons, S. Singh, Molecular Dynamics Study of Polysaccharides in Binary Solvent Mixtures of an Ionic Liquid and Water, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 115(34) (2011) 10251-10258. [CrossRef]

- B. Derecskei, A. Derecskei-Kovacs, Molecular dynamic studies of the compatibility of some cellulose derivatives with selected ionic liquids, Molecular Simulation 32(2) (2006) 109-115. [CrossRef]

- T.G.A. Youngs, J.D. Holbrey, M. Deetlefs, M. Nieuwenhuyzen, M.F. Costa Gomes, C. Hardacre, A Molecular Dynamics Study of Glucose Solvation in the Ionic Liquid 1,3-Dimethylimidazolium Chloride, ChemPhysChem 7(11) (2006) 2279-2281. [CrossRef]

- T.G.A. Youngs, J.D. Holbrey, C.L. Mullan, S.E. Norman, M.C. Lagunas, C. D’Agostino, M.D. Mantle, L.F. Gladden, D.T. Bowron, C. Hardacre, Neutron diffraction, NMR and molecular dynamics study of glucose dissolved in the ionic liquid 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate, Chemical Science 2(8) (2011) 1594-1605. [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Andanson, E. Bordes, J. Devémy, F. Leroux, A.A.H. Pádua, M.F.C. Gomes, Understanding the role of co-solvents in the dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquids, Green Chemistry 16(5) (2014) 2528-2538. [CrossRef]

- Z. Jarin, J. Pfaendtner, Ionic Liquids Can Selectively Change the Conformational Free-Energy Landscape of Sugar Rings, Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation 10(2) (2014) 507-510. [CrossRef]

- V.S. Bharadwaj, T.C. Schutt, T.C. Ashurst, C.M. Maupin, Elucidating the conformational energetics of glucose and cellobiose in ionic liquids, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17(16) (2015) 10668-10678. [CrossRef]

- H. Liu, K.L. Sale, B.M. Holmes, B.A. Simmons, S. Singh, Understanding the Interactions of Cellulose with Ionic Liquids: A Molecular Dynamics Study, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 114(12) (2010) 4293-4301. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. Liu, J. Wang, S. Zhang, Effects of Cationic Structure on Cellulose Dissolution in Ionic Liquids: A Molecular Dynamics Study, ChemPhysChem 13(13) (2012) 3126-3133. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao, X. Liu, J. Wang, S. Zhang, Effects of anionic structure on the dissolution of cellulose in ionic liquids revealed by molecular simulation, Carbohydrate Polymers 94(2) (2013) 723-730. [CrossRef]

- B. Mostofian, X. Cheng, J.C. Smith, Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Cellulose Solvated in Water and in the Ionic Liquid 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolium Chloride, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 118(38) (2014) 11037-11049. [CrossRef]

- F. Huo, Z. Liu, W. Wang, Cosolvent or Antisolvent? A Molecular View of the Interface between Ionic Liquids and Cellulose upon Addition of Another Molecular Solvent, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 117(39) (2013) 11780-11792. [CrossRef]

- H.M. Cho, A.S. Gross, J.-W. Chu, Dissecting Force Interactions in Cellulose Deconstruction Reveals the Required Solvent Versatility for Overcoming Biomass Recalcitrance, Journal of the American Chemical Society 133(35) (2011) 14033-14041. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Gross, A.T. Bell, J.-W. Chu, Entropy of cellulose dissolution in water and in the ionic liquid 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolim chloride, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 14(23) (2012) 8425-8430. [CrossRef]

- A.S. Gross, A.T. Bell, J.-W. Chu, Thermodynamics of Cellulose Solvation in Water and the Ionic Liquid 1-Butyl-3-Methylimidazolim Chloride, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 115(46) (2011) 13433-13440. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Rabideau, A. Agarwal, A.E. Ismail, Observed Mechanism for the Breakup of Small Bundles of Cellulose Iα and Iβ in Ionic Liquids from Molecular Dynamics Simulations, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 117(13) (2013) 3469-3479. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Rabideau, A.E. Ismail, Mechanisms of hydrogen bond formation between ionic liquids and cellulose and the influence of water content, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17(8) (2015) 5767-5775. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, X. Liu, S. Zhang, Y. Yao, X. Yao, J. Xu, X. Lu, Dissolving process of a cellulose bunch in ionic liquids: a molecular dynamics study, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17(27) (2015) 17894-17905. [CrossRef]

- B. Doherty, O. Acevedo, OPLS Force Field for Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents, The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 122(43) (2018) 9982-9993. [CrossRef]

- T. Darden, D. York, L. Pedersen, Particle mesh Ewald: an Nlog(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems, J. Chem. Phys 98 (1993) 10089–10092.

- B. Hess, H. Bekker, H.J.C. Beredensen, J.E.M. Faraaije, LINCS: a linear constraint solver for molecular simulations, J. Comput. Chem. 18 (1997) 1463–1472.

- H.J.C. Berendsen, J.P.M. Postma, W.F. van Gunsteren, A. DiNola, J.R. Haak, Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath, J. Chem. Phys 81 (1984) 3684–3690. [CrossRef]

- G. Bussi, D. Donadio, M. Parrinello, Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling, J Chem Phys 126(1) (2007) 014101. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xie, H. Dong, S. Zhang, X. Lu, X. Ji, Effect of Water on the Density, Viscosity, and CO2 Solubility in Choline Chloride/Urea, Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data 59(11) (2014) 3344-3352.

- C. Florindo, F.S. Oliveira, L.P.N. Rebelo, A.M. Fernandes, I.M. Marrucho, Insights into the Synthesis and Properties of Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Cholinium Chloride and Carboxylic Acids, ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2(10) (2014) 2416-2425. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, H. Sun, G. Liu, H. Zhang, S. Yuan, Q. Zhu, A molecular dynamics study of cellulose inclusion complexes in NaOH/urea aqueous solution, Carbohydr Polym 185 (2018) 12-18. [CrossRef]

- M. Brehm, M. Thomas, S. Gehrke, B. Kirchner, TRAVIS—A free analyzer for trajectories from molecular simulation, The Journal of Chemical Physics 152(16) (2020) 164105. [CrossRef]

- E. Arunan, G.R. Desiraju, R.A. Klein, J. Sadlej, S. Scheiner, I. Alkorta, D.C. Clary, R.H. Crabtree, J.J. Dannenberg, P. Hobza, H.G. Kjaergaard, A.C. Legon, B. Mennucci, D.J. Nesbitt, Definition of the hydrogen bond (IUPAC Recommendations 2011), 83(8) (2011) 1637-1641. [CrossRef]

- P. Muller, Glossary of terms used in physical organic chemistry (IUPAC Recommendations 1994), 66(5) (1994) 1077-1184. [CrossRef]

- I. Pethes, I. Bakó, L. Pusztai, Chloride ions as integral parts of hydrogen bonded networks in aqueous salt solutions: the appearance of solvent separated anion pairs, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 22(19) (2020) 11038-11044. [CrossRef]

- C. Xu, Q.G. Tran, D. Liu, C. Zhai, L. Wojtas, W. Liu, Charge-assisted hydrogen bonding in a bicyclic amide cage: an effective approach to anion recognition and catalysis in water, Chemical Science 15(39) (2024) 16040-16049. [CrossRef]

- Y. Li, J. Wang, X. Liu, S. Zhang, Towards a molecular understanding of cellulose dissolution in ionic liquids: anion/cation effect, synergistic mechanism and physicochemical aspects, Chemical Science 9(17) (2018) 4027-4043. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhang, J. Wu, J. Yu, X. Zhang, J. He, J. Zhang, Application of ionic liquids for dissolving cellulose and fabricating cellulose-based materials: state of the art and future trends, Materials Chemistry Frontiers 1(7) (2017) 1273-1290.

- M. Wohlert, T. Benselfelt, L. Wågberg, I. Furó, L.A. Berglund, J. Wohlert, Cellulose and the role of hydrogen bonds: not in charge of everything, Cellulose 29(1) (2022) 1-23. [CrossRef]

- X. Yuan, G. Cheng, From cellulose fibrils to single chains: understanding cellulose dissolution in ionic liquids, Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 17(47) (2015) 31592-31607. [CrossRef]

| System | Hexamer cellulose | Choline | Cl- | Urea | Oxalic acid |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reline | - | 250 | 250 | 500 | - |

| Oxaline | - | 250 | 250 | - | 250 |

| Cellulose in reline | 4 | 500 | 500 | 1000 | - |

| Cellulose in oxaline | 4 | 500 | 500 | - | 500 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).