Submitted:

31 October 2024

Posted:

01 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Notation

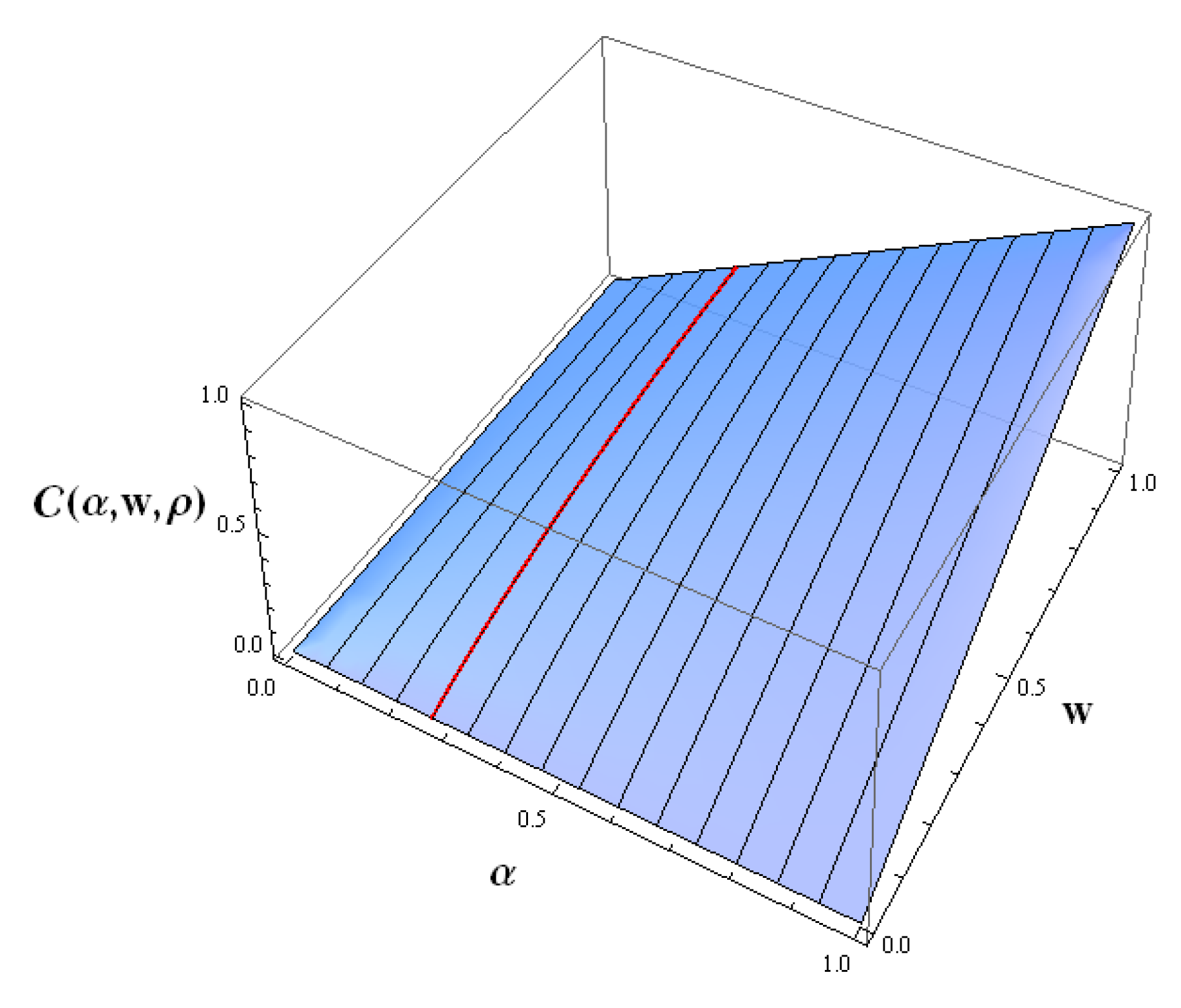

2.1. CoVaR in the Copula Setting

2.2. Portfolio Selection

3. The Mean-CoVaR Model

4. Proofs and Auxiliary Results

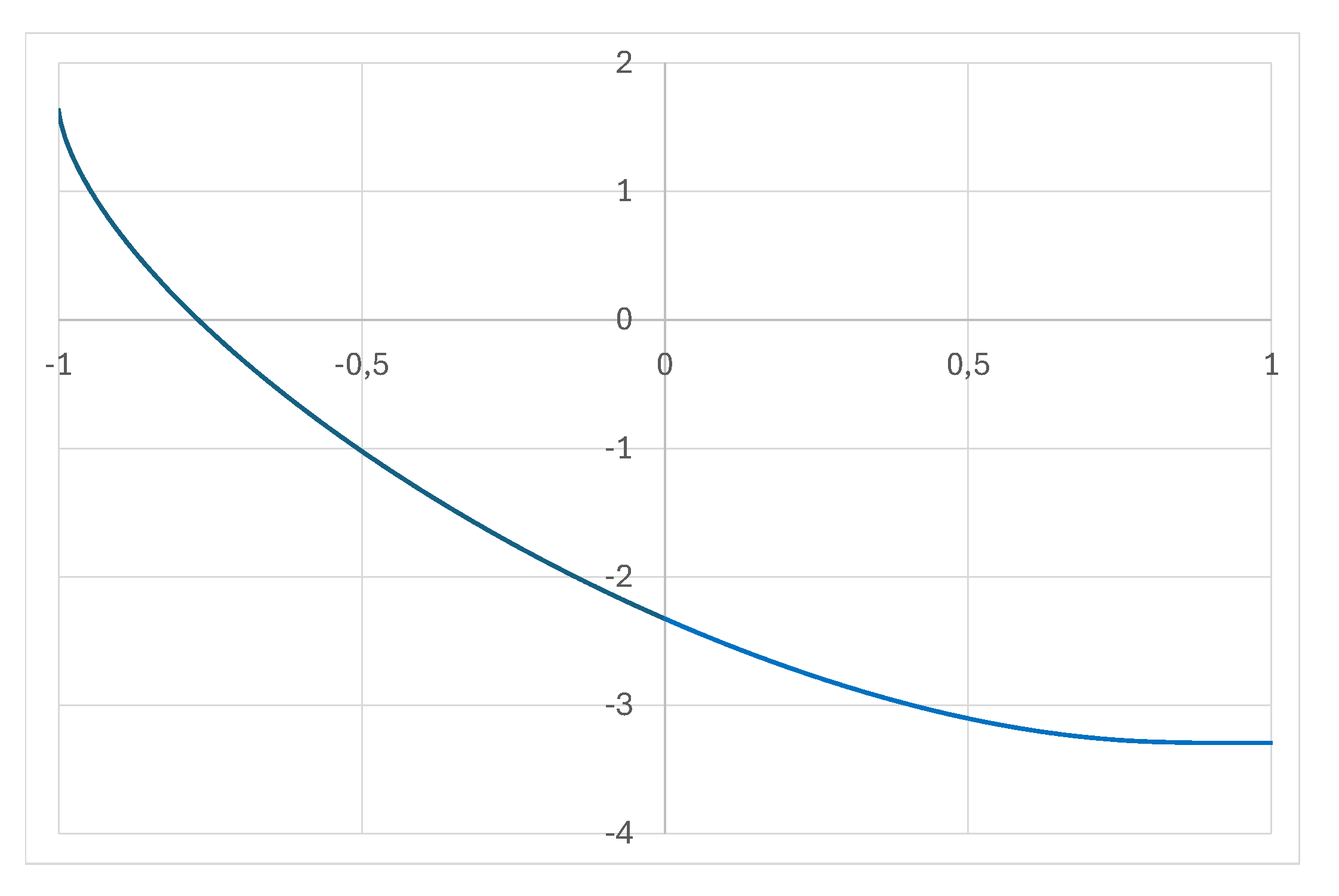

4.1. Gaussian Copulas

- (1)

- (2)

- (3)

- .

4.2. The Optimization Problems

4.2.1. The Basic Problem

4.2.2. The Markowitz Problem

4.2.3. Critical Plane

4.2.4. Auxiliary Optimization Problem

4.2.5. Proof of Theorem 3.1

4.2.6. Proof of Theorem

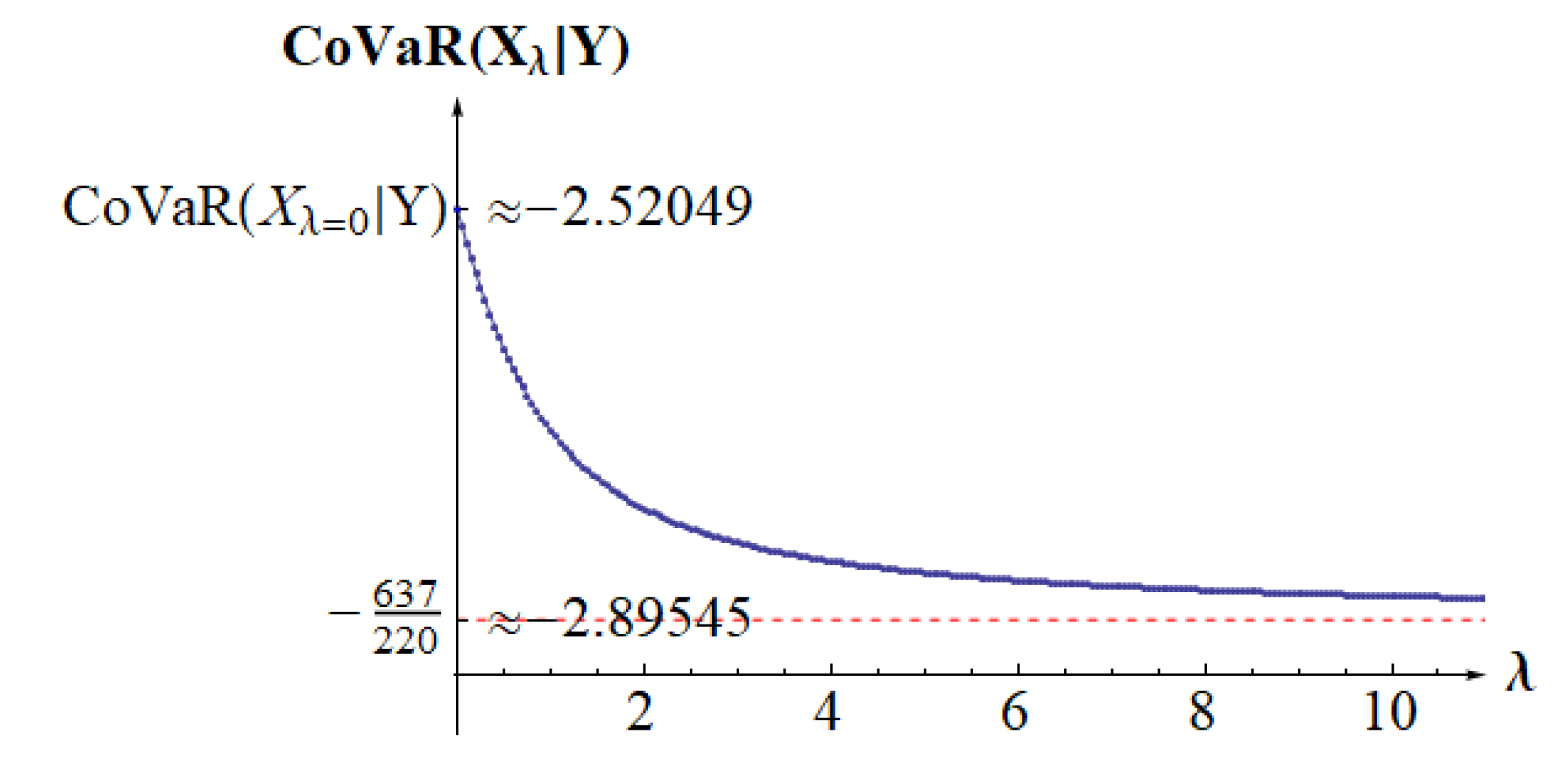

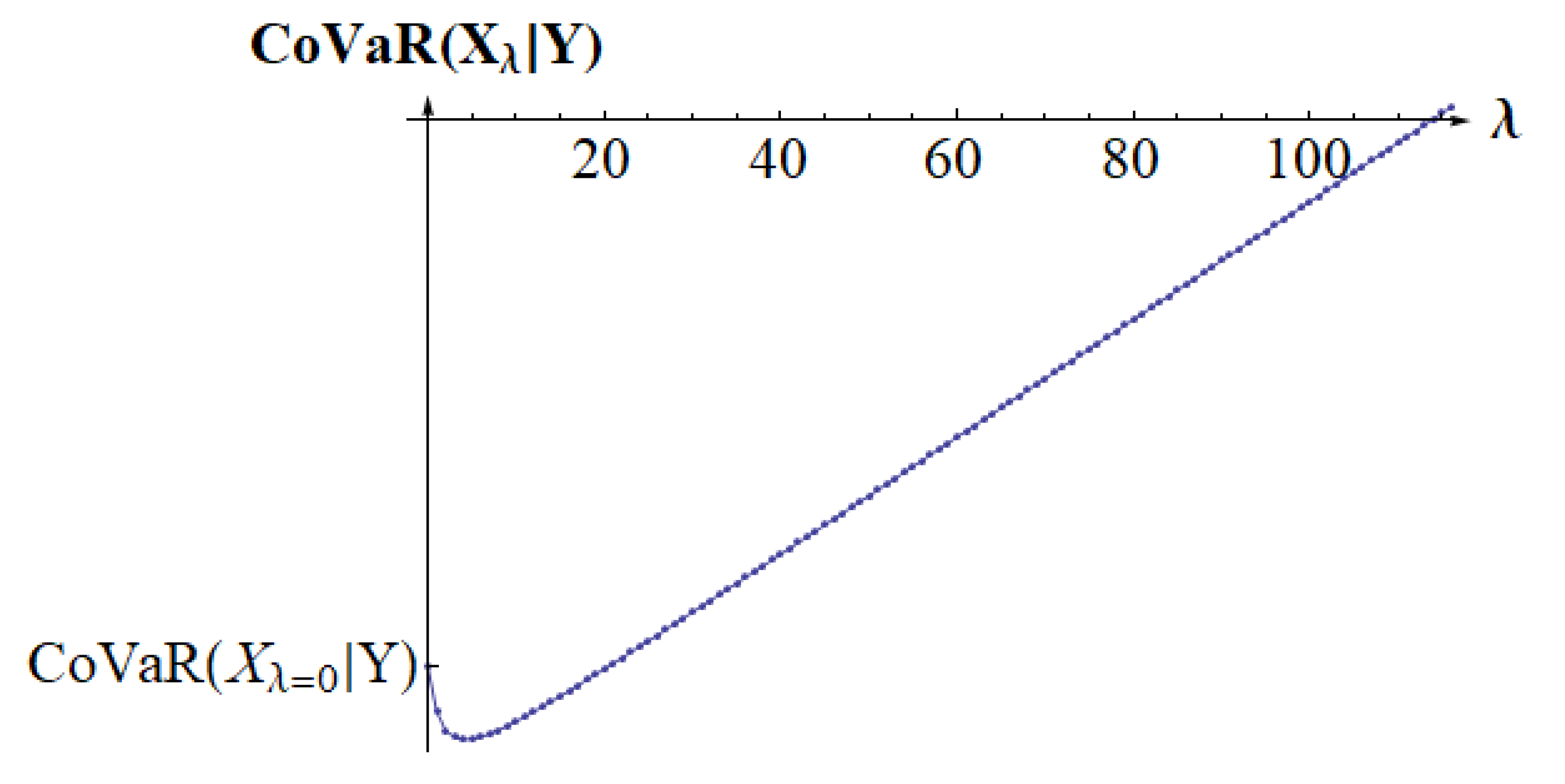

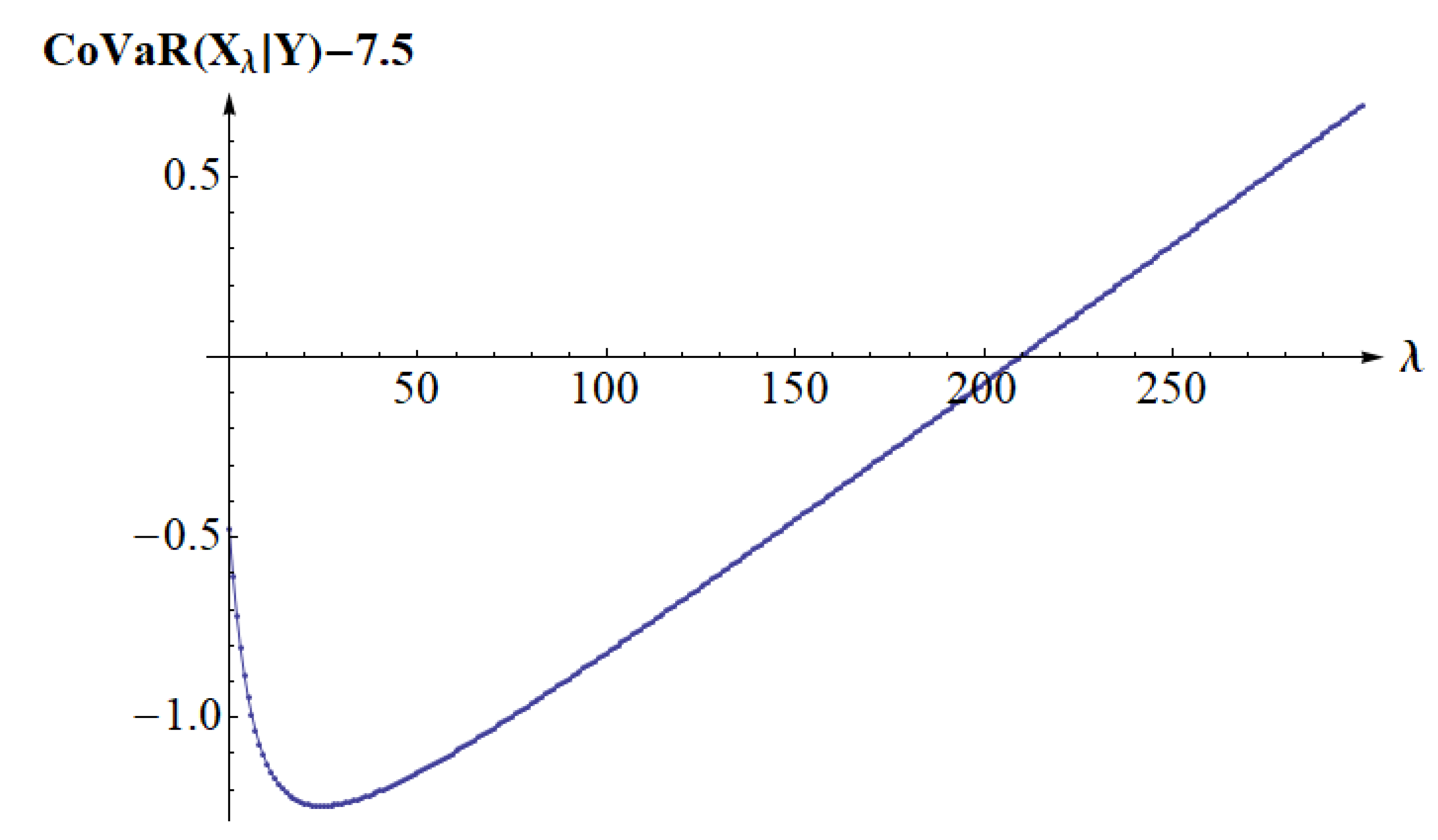

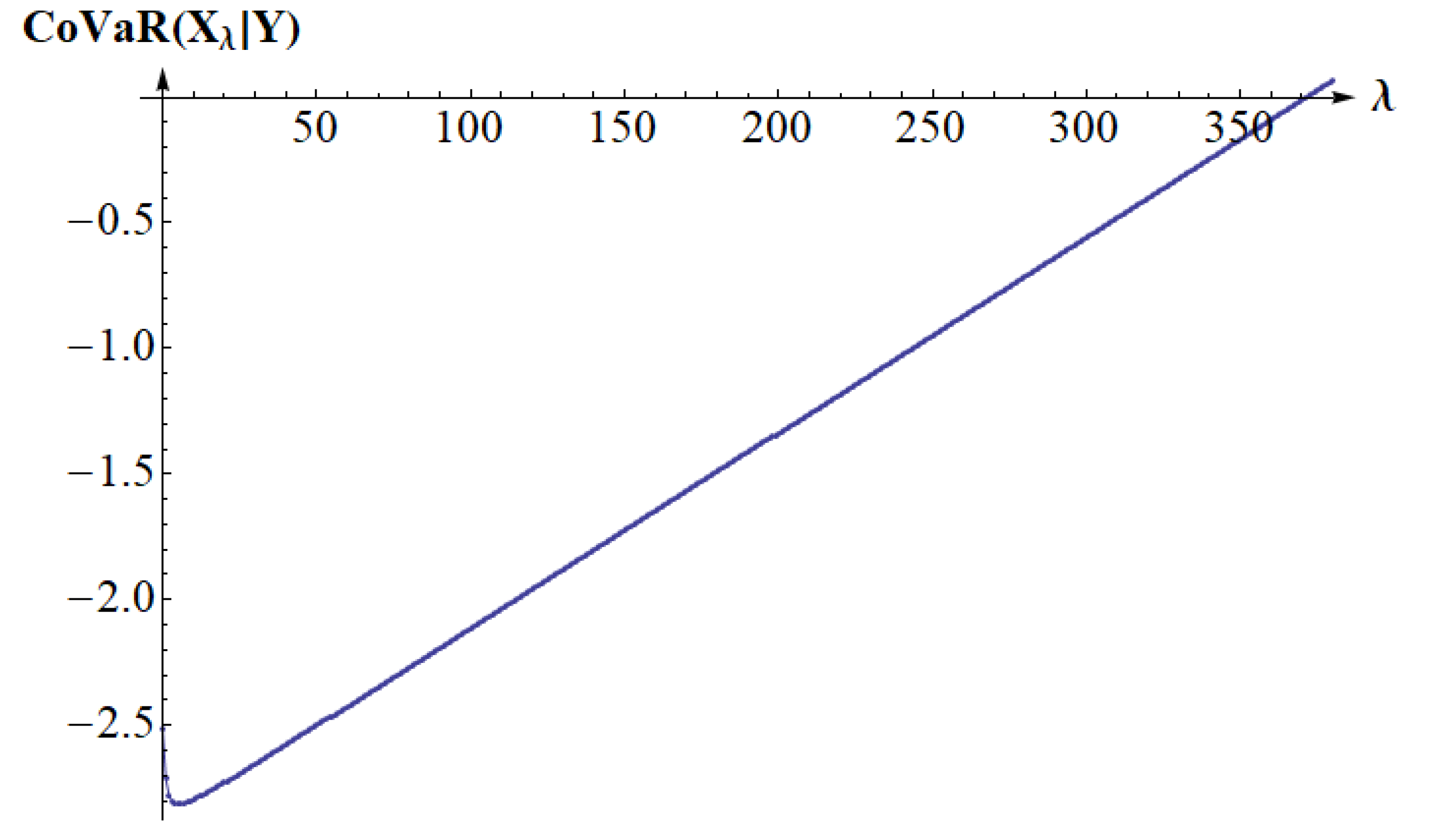

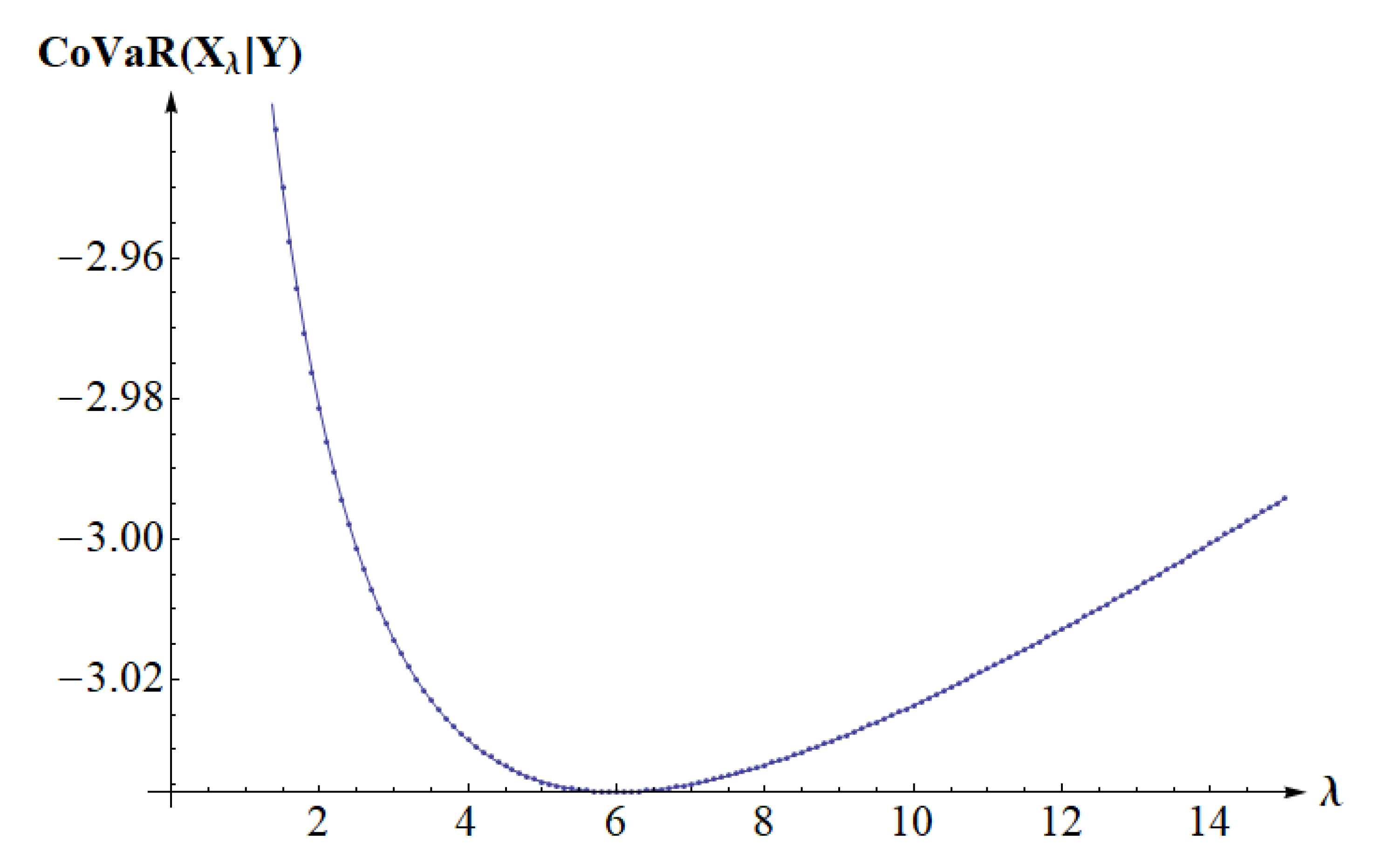

5. Examples

References

- Adrian, T., Brunnermeier, M.K.: CoVaR, The American Economic Review 106.7, 1705-1741 (2016).

- Bernardi, M., Durante, F., Jaworski, P., 2017. Covar of families of copulas. Statistics & Probability Letters 120, 8–17.

- Bernardi, M., Durante, F., Jaworski, P., Petrella, L., Salvadori, G.: Conditional Risk based on multivariate Hazard Scenarios. Stochastic Environmental Research and Risk Assessment 32 (2018) 203-211.

- Cherubini, U., Luciano, E., Vecchiato, W.: Copula Methods in Finance, John Wiley & Sons Ltd 2004.

- Durante, F., Sempi, C.: Principles of copula theory, CRC Press 2016.

- Embrechts, P.: Copulas: a personal view. Journal of Risk and Insurance, 76, 639–650 (2009).

- Föllmer, H., Schied, A.: Stochastic Finance. An Introduction in Discrete Time, de Gruyter, 2nd Edition, 2004.

- Girardi, G., Ergün T.A.: Systemic risk measurement: Multivariate GARCH estimation of CoVar, Journal of Banking & Finance 37, (2013) 3169-3180.

- Hakwa B., Jäger-Ambrozewicz, M., Rüdiger, B.: Analysing systemic risk contribution using a closed formula for conditional Value at Risk through copula. Commun. Stoch. Anal., 9(1):131–158, 2015.

- Jaworski, P.: The limiting properties of copulas under univariate conditioning, In: Copulae in Mathematical and Quantitative Finance, P.Jaworski, F.Durante, W.K.Härdle (Eds.), Springer 2013, pp.129–163.

- Jaworski, P., On the Conditional Value at Risk (CoVaR) for tail-dependent copulas, Dependence Modeling 5 (2017) 1-15.

- Jaworski, P., On the Conditional Value-at-Risk (CoVaR) in copula setting, W: Úbeda Flores, M., de Amo Artero, E., Durante, F., Fernández-Sánchez, J. (Eds.) Copulas and Dependence Models with Applications, Springer, Cham 2017, pp. 95-117.

- Joe, H.: Dependence Modeling with Copulas. Chapman & Hall/CRC, London, 2014.

- Mai, J., Scherer, M., 2012. Simulating Copulas: Stochastic Models, Sampling Algorithms, and Applications. Series in quantitative finance. Imperial College Press.

- Mainik G., Schaanning E.: On dependence consistency of CoVaR and some other systemic risk measures. Stat. Risk Model., 31, 49–77 (2014).

- McNeil, A.J., Frey, R., Embrechts, P.. Quantitative risk management. concepts, techniques and tools. Princeton Series in Finance. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2005.

- Meyer, C., 2013. The bivariate normal copula. Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 42 (13), 2402–2422.

- Nelsen, R.B.: An introduction to copulas. Springer Series in Statistics. Springer, New York, second edition, 2006.

- Sheppard, W.F., 1900 On the calculation of the double integral expressing normal correlation. Trans. Camb. Phil. Soc., 19, 23-68.

- Zalewska, A., 2018. On peculiarities of covar-based portfolio selection. Applicationes Mathematicae, 181–197.

| 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).