Submitted:

30 October 2024

Posted:

31 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

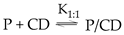

2. Classification of preservatives and their physiochemical properties

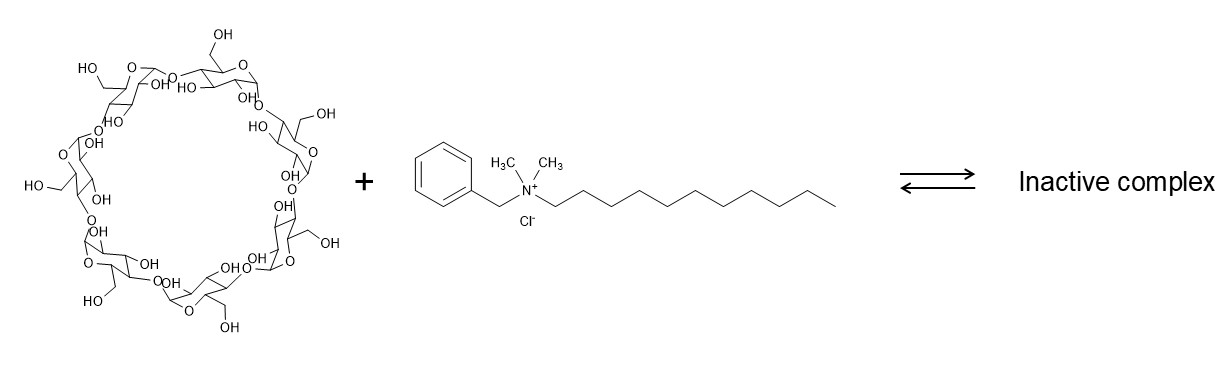

3. Preservative – cyclodextrin interactions

4. Studies of Antimicrobial Efficacy in Aqueous CD Solutions

5. Examples of Marketed Products

6. Examples from the Patent Literature

7. Conclusions

- The chemical structure and physiochemical properties of a preservative determine its affinity for CDs and their inactivation.

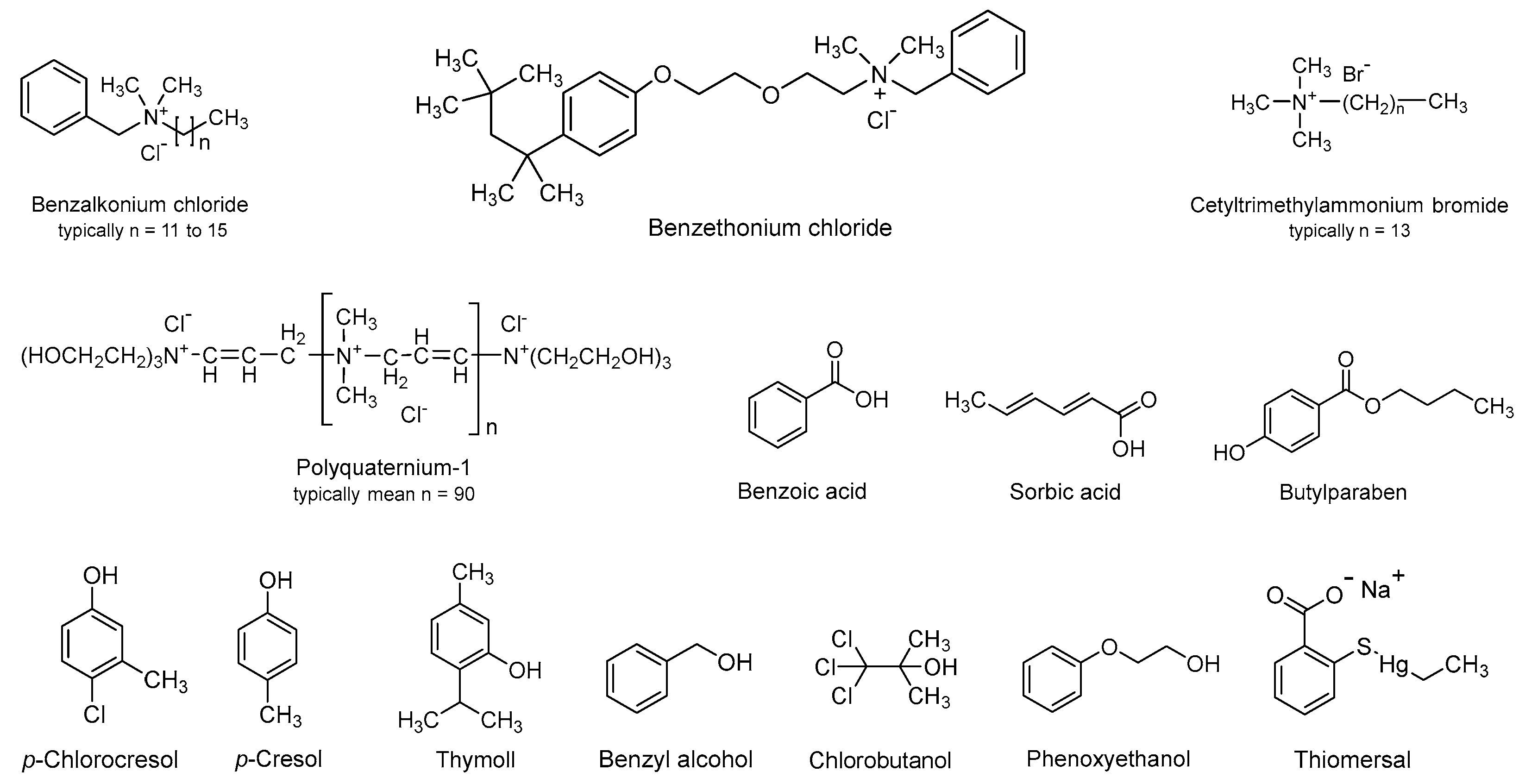

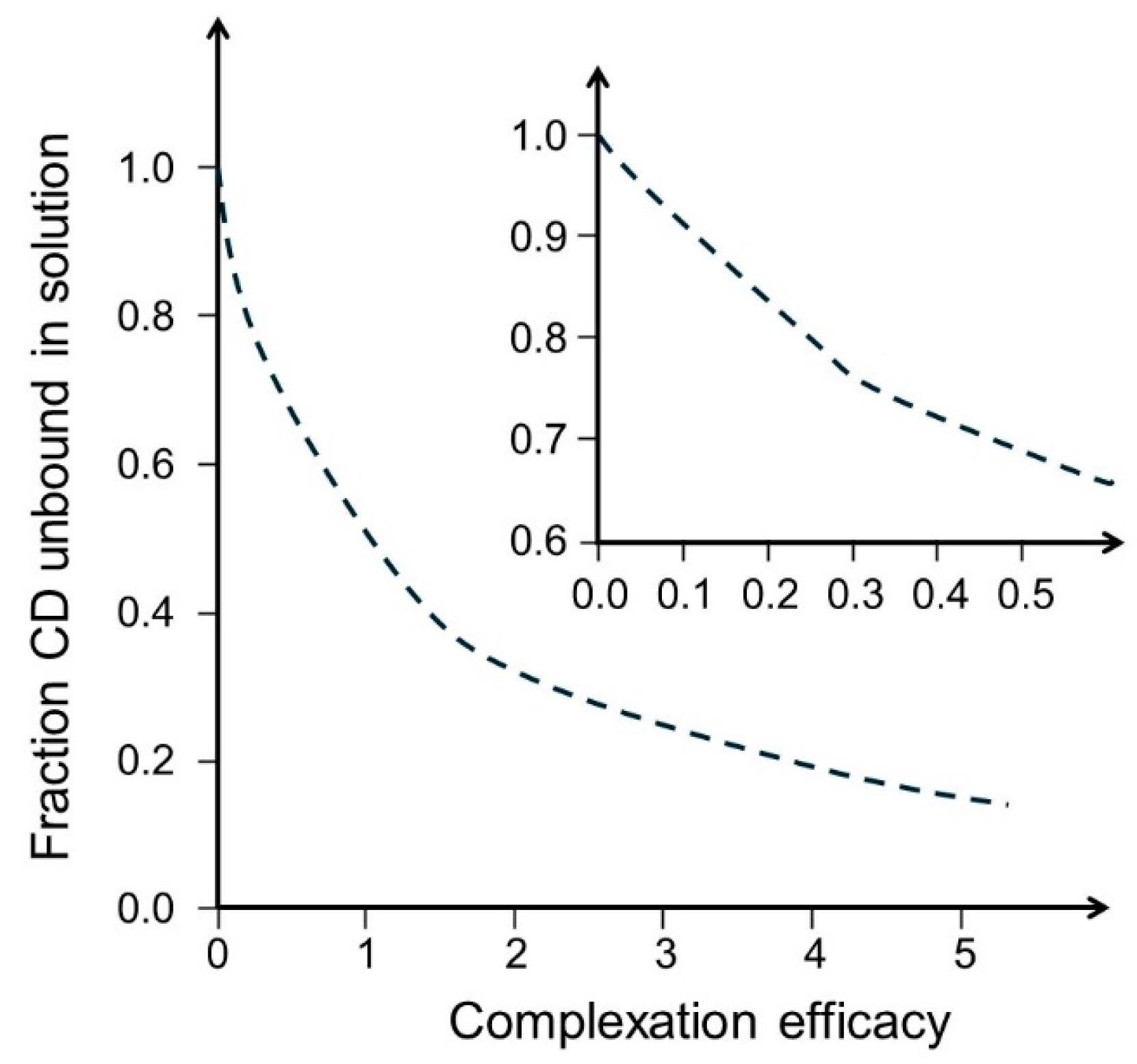

- Antimicrobial preservation is highly dependent on CD concentration, where approximately 1% CD can have an insignificant effect, but concentrations above approximately 5% have a significant effect.

- In general, highly hydrophilic preservatives have less affinity for CDs and are less likely to be inactivated by CDs.

- Highly water-soluble preservatives can be inactivated by CDs because preservative molecules that carry lipophilic moieties can form inclusion CD complexes.

- The CD concentration in a given aqueous drug formulation is determined by the drug concentration and is generally high with respect to the preservative. Thus, the drug will have negligible effect on the fraction of free preservatives in the formulation.

- The inclusion of excipients that possess some antimicrobial activity on their own (e.g., antimicrobial efficacy enhancers such as EDTA, boric acid, borax, and zinc ions) can boost the preservation efficacy of pharmaceutical excipients in aqueous CD formulations.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cox, S.D.; Mann, C.M.; Markham, J.L. Interactions between components of the essential oil of Melaleuca alternifolia. Journal of Applied Microbiology 2001, 91, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurup, T.R.; Wan, L.S.; Chan, L.W. Availability and activity of preservatives in emulsified systems. Pharm Acta Helv 1991, 66, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bean, H.; Heman-Ackah, S.; Thomas, J. The activity of antibacterials in two-phase systems. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem 1965, 16, 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes, A.R. Compatibility of a commercially available low-density polyethylene eye-drop container with antimicrobial preservatives and potassium ascorbate. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 1995, 20, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anurova, M.N.; Bakhrushina, E.O.; Demina, N.B.; Panteleeva, E.S. Modern Preservatives of Microbiological Stability (Review). Pharm. Chem. J. 2019, 53, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inaba, K.; Minami, M.; Yamaguchi, M.; Goto, R.; Otake, H.; Kotake, T.; Nagai, N. Effects of the Ophthalmic Additive Mannitol on Antimicrobial Activity and Corneal Toxicity of Various Preservatives. Chem. Pharm. Bull. (Tokyo) 2020, 68, 1069–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, L.V. Rx Remington: The Science and Practice of Pharmacy, 22nd Edition: Volume 1-The Science of Pharmacy; PhP: 2013.

- Physicochemical Principles of Pharmacy in Manufacture, Formulation and Clinical Use; Florence, A.T., Attwood, D., Eds.; Pharmaceutical Press: 2015; p. 664.

- Sinko, P.J. , (Ed.) Martin's Physical Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. 6 ed.; Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Loftsson, T.; Stefánsdóttir, Ó.; Friðriksdóttir, H.; Guðmundsson, Ö. Interactions between preservatives and 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin. 1992, 18, 1477-1484. [CrossRef]

- Miyajima, K.; Ikuto, M.; Nakagaki, M. Interaction of Short-Chain Alkylammonium Salts with Cyclodextrins in Aqueous Solutions. Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin 1987, 35, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.J. Neutralisation of the antibacterial action of quaternary ammonium compounds with cyclodextrins. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1992, 90, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, S.J.; Müller, B.W.; Seydel, J.K. Interactions between p-hydroxybenzoic acid esters and hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin and their antimicrobial effect against Candida albicans. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1993, 93, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, R.; Olesen, N.E.; Alexandersen, S.D.; Dahlgaard, B.N.; Westh, P.; Mu, H. Thermodynamic investigation of the interaction between cyclodextrins and preservatives — Application and verification in a mathematical model to determine the needed preservative surplus in aqueous cyclodextrin formulations. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2016, 87, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehner, S.J.; Müller, B.W.; Seydel, J.K. Effect of Hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin on the Antimicrobial Action of Preservatives. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 1994, 46, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaekeh-Nikouei, B.; Fazly Bazzaz, B.S.; Soheili, V.; Mohammadian, K. Problems in Ophthalmic Drug Delivery: Evaluation of the Interaction Between Preservatives and Cyclodextrins. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology 2013, 6, 6333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, G.S.; Tozetto, N.M.; Pedroso, T.A.A.; de Mattos, M.A.; Urban, A.M.; Paludo, K.S.; dos Santos, F.A.; Neppelenbroek, K.H.; Urban, V.M. Anti-Candida Activity and in Vitro Toxicity Screening of Antifungals Complexed With β-cyclodextrin. Journal of Applied Toxicology 2024, 44, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, S.; Agrawal, G.P. Preparation and characterization of solid inclusion complex of cefpodoxime proxetil with β-cyclodextrin. Current Drug Delivery 2008, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shlar, I.; Droby, S.; Choudhary, R.; Rodov, V. The Mode of Antimicrobial Action of Curcumin Depends on the Delivery System: Monolithic Nanoparticles vs. Supramolecular Inclusion Complex. RSC Advances 2017, 7, 42559–42569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jug, M.; Kosalec, I.; Maestrelli, F.; Mura, P. Analysis of triclosan inclusion complexes with β-cyclodextrin and its water-soluble polymeric derivative. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 54, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizera, M.; Szymanowska, D.; Stasilowicz, A.; Siakowska, D.; Lewandowska, K.; Miklaszewski, A.; Plech, T.; Tykarska, E.; Cielecka-Piontek, J. Computer-aided design of cefuroxime axetil/cyclodextrin system with enhanced solubility and antimicrobial activity. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-g.; Li, D.-h.; Kong, Y.-m.; Zhang, R.-r.; Gu, Q.; Hu, M.-x.; Tian, S.-y.; Jin, W.-g. Enhanced antibacterial efficacy and mechanism of octyl gallate/beta-cyclodextrins against Pseudomonas fluorescens and Vibrio parahaemolyticus and incorporated electrospun nanofibers for Chinese giant salamander fillets preservation. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 361, 109460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, K.I.R.; Denadai, A.M.L.; Sinisterra, R.D.; Cortes, M.E. Cyclodextrin modulates the cytotoxic effects of chlorhexidine on microorganisms and cells in vitro. Drug Delivery 2015, 22, 444–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sripetch, S.; Prajapati, M.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrins and Drug Membrane Permeation: Thermodynamic Considerations. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2022, 111, 2571–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kis, G.L.; Fetz, A.; Schoch, C. Ophthalmic compositions containing cyclodextrins and quaternary ammonium compounds. WO971 0805, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, E.J.; Espino, R.L. Preservative systems for pharmaceutical compositions containing cyclodextrins. WO980 6381, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, D.; Crowley, P.J. Antimicrobial preservatives part one: choosing a preservative system. American Pharmaceutical Review 2017, 20, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, Y.; Kimura, A.; Coffey, M.J.; Tyle, P. Pharmaceutical Development of Suspension Dosage Form. In Pharmaceutical Suspensions: From Formulation Development to Manufacturing, Kulshreshtha, A.K., Singh, O.N., Wall, G.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, 2017; pp. 103–126. [Google Scholar]

- Geier, D.A.; Sykes, L.K.; Geier, M.R. A Review of Thimerosal (Merthiolate) and its Ethylmercury Breakdown Product: Specific Historical Considerations Regarding Safety and Effectiveness. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health, Part B 2007, 10, 575–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashman, A.L.; Warshaw, E.M. Parabens: a review of epidemiology, structure, allergenicity, and hormonal properties. Dermatitis 2005, 16, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, K.M. Functional Materials Based on Molecules With Hydrogen-Bonding Ability: Applications to Drug Co-Crystals and Polymer Complexes. Royal Society Open Science 2018, 5, 180564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.; Nakashima, S.; Zimmerman, S.C. Synthesis of a Soluble Ureido-Naphthyridine Oligomer That Self-Associates via Eight Contiguous Hydrogen Bonds. Organic Letters 2005, 7, 3005–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Brewster, M.E. Cyclodextrins as functional excipients: Methods to enhance complexation efficiency. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2012, 101, 3019–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murai, S. Inclusion into β-cyclodextrin and adsorption by β-cyclodextrin polymer for ionic surfactants. Kenkyu Hokoku - Kanagawa-ken Sangyo Gijutsu Senta 2008, 14, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Matsui, Y.; Mochida, K. Binding forces contributing to the association of cyclodextrin with alcohol in an aqueous solution. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979, 52, 2808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá Couto, A.R.; Ryzhakov, A.; Larsen, K.L.; Loftsson, T. Interaction of native cyclodextrins and their hydroxypropylated derivatives with parabens in aqueous solutions. Part 1: evaluation of inclusion complexes. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry 2019, 93, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Nishihata, T.; Rytting, J.H. Study of the interaction between β-cyclodextrin and chlorhexidine. Pharm. Res. 1994, 11, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, Y.; Nishioka, T.; Fujita, T. Quantitative structure-reactivity analysis of the inclusion mechanism by cyclodextrins. Top. Curr. Chem. 1985, 128, 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Buvari, A.; Barcza, L. Complex formation of phenol, aniline, and their nitro derivatives with β-cyclodextrin. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1988, 543.

- Padula, C.; Pescina, S.; Grolli Lucca, L.; Demurtas, A.; Santi, P.; Nicoli, S. Skin Retention of Sorbates from an After Sun Formulation for a Broad Photoprotection. Cosmetics 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Hreinsdottir, D.; Masson, M. Evaluation of cyclodextrin solubilization of drugs. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2005, 302, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loftsson, T.; Hreinsdóttir, D.; Másson, M. The complexation efficiency. Journal of Inclusion Phenomena and Macrocyclic Chemistry 2007, 57, 545–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maw, P.D.; Jansook, P. Cyclodextrin-based Pickering nanoemulsions containing amphotericin B: Part I. evaluation of oil/cyclodextrin and amphotericin B/cyclodextrin inclusion complexes. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 68, 103118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Praphanwittaya, P.; Saokham, P.; Jansook, P.; Loftsson, T. Aqueous solubility of kinase inhibitors: I the effect of hydrophilic polymers on their γ-cyclodextrin solubilization. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansook, P.; Stefánsson, E.; Thorsteinsdóttir, M.; Sigurdsson, B.B.; Kristjánsdóttir, S.S.; Bas, J.F.; Sigurdsson, H.H.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrin solubilization of carbonic anhydrase inhibitor drugs: Formulation of dorzolamide eye drop microparticle suspension. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2010, 76, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansook, P.; Hnin, H.M.; Praphanwittaya, P.; Loftsson, T.; Stefansson, E. Effect of salt formation on γ-cyclodextrin solubilization of irbesartan and candesartan and the chemical stability of their ternary complexes. J. Drug. Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 67, 102980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansook, P.; Kulsirachote, P.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrin solubilization of celecoxib: solid and solution state characterization. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2018, 90, 75–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khin, S.Y.; Soe, H.M.S.H.; Chansriniyom, C.; Pornputtapong, N.; Asasutjarit, R.; Loftsson, T.; Jansook, P. Development of fenofibrate/randomly methylated β-cyclodextrin-loaded eudragit RL 100 nanoparticles for ocular delivery. Molecules 2022, 27, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malaekeh-Nikouei, B.; Sajadi Tabassi, S.A.; Ashari, H.; Gholamzadeh, A. Evaluation the effect of cyclodextrin complexation on aqueous solubility of fluorometholone to achieve ophthalmic solution. J. Inclusion Phenom. Macrocyclic Chem. 2009, 65, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirri, M.; Maestrelli, F.; Corti, G.; Furlanetto, S.; Mura, P. Simultaneous effect of cyclodextrin complexation, pH, and hydrophilic polymers on naproxen solubilization. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis 2006, 42, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soe, H.M.; Kerdpol, K.; Rungrotmongkol, T.; Pruksakorn, P.; Autthateinchai, R.; Wet-osot, S.; Loftsson, T.; Jansook, P. Voriconazole Eye Drops: Enhanced Solubility and Stability through Ternary Voriconazole/Sulfobutyl Ether β-Cyclodextrin/Polyvinyl Alcohol Complexes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaekeh-Nikouei, B.; Bazzaz, B.S.F.; Soheili, V.; Mohammadian, K. Problems in Ophthalmic Drug Delivery: Evaluation of the Interaction Between Preservatives and Cyclodextrins. Jundishapur Journal of Microbiology 2013, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, W.J. Neutralization of the antibacterial action of quaternary ammonium compounds with cyclodextrins. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1992, 90, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimian, A.; Lakzaei, M.; Askari, H.; Dostdari, S.; Khafri, A.; Aminian, M. In vitro assessment of Thimerosal cytotoxicity and antimicrobial activity. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology 2023, 77, 127129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puskás, I.; Szente, L.; Szöcs, L.; Fenyvesi, E. Recent List of Cyclodextrin-Containing Drug Products. Periodica Polytechnica-Chemical Engineering 2023, 67, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurin, F.; Pages, B.; Coquelet, C. Ready-to-use eye lotions containing indomethacin. EP076 1217A1, 1997.

- Cox, M.; Nanda, N. Methods of treating pediatric cancers. US1119 1766B2, 2017.

- Lopalco, A.; Lopedota, A.A.; Laquintana, V.; Denora, N.; Stella, V.J. Boric Acid, a Lewis Acid with Unique and Unusual Properties: Formulation Implications. J. Pharm. Sci. (Philadelphia, PA, U. S.) 2020, 109, 2375–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jansook, P.; Kurkov, S.V.; Loftsson, T. Cyclodextrins as solubilizers: formation of complex aggregates. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2010, 99, 719–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kis, G.L.; Fetz, A.; Schoch, C. Ophthalmic compositions containing cyclodextrins and quaternary ammonium compounds. WO971 0805, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Szente, L.; Kis, G.L.; Schoch, C.; Fetz, A.; Szeman, J.; Szejtli, J. Development of a diclofenac-Na/HPγCD ophthalmic composition. In Proceedings of the Cyclodextrin: From Basic Research to Market, International Cyclodextrin Symposium, 2000; pp. 210-218.

- Lyons, R.T.; Chang, J.N. Inhibition of irritating side effects associated with use of a topical ophthalmic medication. US2005000 4074, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho Feitosa, R.; Souza Ribeiro Costa, J.; van Vliet Lima, M.; Sawa Akioka Ishikawa, E.; Cogo Müller, K.; Bonin Okasaki, F.; Sabadini, E.; Garnero, C.; Longhi, M.R.; Lavayen, V.; et al. Supramolecular Arrangement of Doxycycline with Sulfobutylether-β-Cyclodextrin: Impact on Nanostructuration with Chitosan, Drug Degradation and Antimicrobial Potency. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skuredina, A.A.; Tychinina, A.S.; Le-Deygen, I.M.; Golyshev, S.A.; Kopnova, T.Y.; Le, N.T.; Belogurova, N.G.; Kudryashova, E.V. Cyclodextrins and Their Polymers Affect the Lipid Membrane Permeability and Increase Levofloxacin’s Antibacterial Activity In Vitro. Polymers 2022, 14, 4476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Gaetano, F.; Marino, A.; Marchetta, A.; Bongiorno, C.; Zagami, R.; Cristiano, M.C.; Paolino, D.; Pistarà, V.; Ventura, C.A. Development of Chitosan/Cyclodextrin Nanospheres for Levofloxacin Ocular Delivery. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaki, N.; Pipkin, J.D. Composition containing sulfoalkyl ether cyclodextrin and latanoprost. US10463677B2 2012.

- Mosher, G.L.; Gayed, A.A.; Wedel, R.L. Taste-masked formulations containing sertraline and sulfoalkyl ether cyclodextrin. US2005025 0738A1, 2005.

- Loftsson, T.; Pilotaz, F. Multidose aqueous ophthalmic compositions comprising drug/cyclodextrin complexes and sorbic acid. WO202314 8231, 2023. [Google Scholar]

| Preservative | Molecular weight (g/mol) | pKa | H-bonds | LogD4 | LogD7 | Solubility (mg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Donors | Acceptors | pH 4 | pH 7 | |||||

| Benzethonium chloride | 448.08 | - | 0 | 3 | - | 4.0 | >10 | >10 |

| Benzoic acid | 122.12 | 4.20 | 1 | 2 | 1.35 | -1.08 | 8.8 | 1000 |

| Benzyl alcohol | 108.14 | - | 1 | 1 | 1.06 | 1.06 | 47 | 47 |

| Benzyldodecyldimethylammonium chloride* | 339.99 | - | 0 | 1 | 2.63 | 2.63 | 866 | 866 |

| Butyl paraben | 194.23 | 8.22 | 1 | 3 | 3.41 | 3.38 | 0.50 | 0.54 |

| Chlorobutanol | 177.46 | - | 1 | 1 | 1.73 | 1.73 | 10 | 10 |

| Chlorohexidine | 505.45 | 11.51 | 10 | 10 | 1.56 | 1.58 | 1.1 | 1.0 |

| m-Cresol | 108.14 | 10.07 | 1 | 1 | 2.04 | 2.04 | 23 | 23 |

| Diazolidinyl urea | 278.22 | 11.22 | 5 | 11 | -5.40 | -5.40 | 999 | 999 |

| Imidazolidinyl urea | 388.29 | 7.41 | 8 | 16 | -4.93 | -5.02 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Isobutyl paraben | 194.23 | 8.17 | 1 | 3 | 3.25 | 3.23 | 0.56 | 0.60 |

| Methyl paraben | 152.15 | 8.31 | 1 | 3 | 1.88 | 1.86 | 5.5 | 5.6 |

| Phenol | 94.11 | 9.86 | 1 | 1 | 1.54 | 1.54 | 96 | 96 |

| Phenoxyethanol | 138.16 | - | 1 | 2 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 17 | 17 |

| Polyquaternium-1 | >800 | - | 6 | ≥8 | -9.90 | -9.90 | ** | ** |

| Propyl paraben | 180.20 | 8.23 | 1 | 3 | 2.90 | 2.88 | 1.1 | 1.2 |

| Quaternium-15 | 251.16 | 3.7 | 0 | 4 | - | -0.1 | - | 1000 |

| Sorbic acid | 112.13 | 4.60 | 1 | 2 | 1.17 | -1.12 | 11 | 1000 |

| Thiomersal | 404.82 | 3.62 | 0 | 3 | - | -1.88 | - | 1000 |

| Preservative | Effective conc. (% w/v) | Cyclodextrin | K1:1 (M-1) | CE | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzalkonium chloride | 0.004 – 0.02 | βCD | 1400 | 3500 | [34] |

| Benzoic acid, unionized | 0.1 – 0.2 | βCD | 678 | 30 | [14] |

| RMβCD | 1013 | 44 | [14] | ||

| HPβCD | 536 | 36 | [14] | ||

| SBEβCD | 924 | 41 | [14] | ||

| Benzyl alcohol | 0.5 – 5 | αCD | 22 | 9.5 | [35] |

| βCD | 50 | 22 | [35] | ||

| Butyl paraben | 0.02 – 0.4 | αCD | 701 | 0.38 | [36] |

| HPαCD | 323 | 0.18 | [36] | ||

| βCD | 4582 | 2.5 | [36] | ||

| HPβCD | 16,240 | 9.0 | [36] | ||

| Chlorohexidine | 0.1 – 0.2 | βCD | 268 | 0.58 | [37] |

| m-Cresol | 0.15 – 0.3 | βCD | 95 | 20 | [38] |

| Ethyl paraben | 0.1 – 0.3 | αCD | 193 | 0.84 | [36] |

| HPαCD | 149 | 0.65 | [36] | ||

| βCD | 1709 | 7.46 | [36] | ||

| Methyl paraben | 0.01 – 0.4 | HPαCD | 67 | 1.3 | [36] |

| βCD | 772 | 27 | [14] | ||

| RMβCD | 1453 | 52 | [14] | ||

| HPβCD | 1128 | 28 | [14] | ||

| SBEβCD | 1519 | 55 | [14] | ||

| Phenol | 0.2 – 0.5 | βCD | 129 | 129 | [39] |

| Phenoxyethanol | 0.25 – 0.5 | HPβCD | 100 | 12 | [13] |

| Propyl paraben | 0.005 – 0.1 | αCD | 240 | 0.42 | [36] |

| HPαCD | 230 | 0.39 | [36] | ||

| βCD | 1548 | 9.3 | [14] | ||

| RMβCD | 3544 | 21 | [14] | ||

| HPβCD | 2360 | 16 | [14] | ||

| SBEβCD | 3165 | 19 | [14] | ||

| Sorbic acid, unionized | 0.05 – 0.5 | αCD | [119]1 | [2.2]1 | [40] |

| HPβCD | [42]1 | [0.76]1 | [40] | ||

| Thiomersal | 0.001 – 0.1 | HPβCD | 1916 | 19 | [13] |

| Drug | MW (g/mol) | S0 (M) | Cyclodextrin | CE | D:CD molar ratio | funbound | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetazolamide (pKa 7.4) | 222.25 | 0.003 | HPβCD | 0.246 | 1:5 | 0.80 | [41] |

| RMβCD | 0.566 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [42] | |||

| HPγCD | 0.021 | 1:50 | 0.98 | [42] | |||

| Amphotericin B (pKa 5.7, 10.0)1 | 924.09 | 0.000002 | αCD | 0.002 | 1:500 | 1.0 | [43] |

| βCD | 0.001 | 1:1000 | 1.0 | [43] | |||

| γCD | 0.069 | 1:16 | 0.94 | [43] | |||

| HPγCD | 0.039 | 1:27 | 0.96 | [43] | |||

| Axitinib (pKa 4.3)2 | 386.47 | 0.000001 | γCD | 0.0002 | 1:5,000 | 1.00 | [44] |

| Brinzolamide (pKa 5.9, 8.4) | 383.51 | 0.001 | γCD | 0.02 | 1:50 | 0.98 | [45] |

| HPγCD | 0.03 | 1:35 | 0.97 | [45] | |||

| Candesartan cilexetil (pKa 3.5, 5.9)3 | 610.66 | 0.00001 | γCD | 0.0012 | 1:835 | 1.0 | [46] |

| Celecoxib (pKa 9.6) | 381.37 | 0.000003 | αCD | 0.0001 | 1:10,000 | 1.00 | [47] |

| βCD | 0.0022 | 1:500 | 1.00 | [47] | |||

| γCD | 0.0004 | 1:2,500 | 1.00 | [47] | |||

| HPβCD | 0.0075 | 1:135 | 0.99 | [47] | |||

| RMβCD | 0.0089 | 1:113 | 0.99 | [47] | |||

| Cyclosporin A | 1202.61 | 0.00001 | HPβCD | 0.004 | 1:250 | 1.00 | [41] |

| Dexamethasone | 392.46 | 0.0004 | HPβCD | 0.326 | 1:4 | 0.75 | [41] |

| Dovitinib (pKa 7.7)2 | 392.43 | 0.00002 | γCD | 0.011 | 1:92 | 0.99 | [44] |

| Fenofibrate | 360.83 | 0.00001 | αCD | 0.20 | 1:6 | 0.83 | [48] |

| βCD | 1.85 | 1:1.5 | 0.33 | [48] | |||

| γCD | 0.21 | 1:6 | 0.83 | [48] | |||

| SBEβCD | 0.63 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [48] | |||

| HPβCD | 2.62 | 1:1.4 | 0.29 | [48] | |||

| RMβCD | 4.54 | 1:1.2 | 0.17 | [48] | |||

| Fluorometholone | 376.46 | 0.00008 | SBEβCD | 1.91 | 1:1.5 | 0.33 | [49] |

| HPγCD | 0.467 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [49] | |||

| Hydrocortisone | 362.46 | 0.001 | HPβCD | 2.00 | 1:1.5 | 0.33 | [41] |

| Irbesartan (pKa 4.1, 7.4)3 | 428.53 | 0.00001 | γCD | 0.289 | 1:5 | 0.80 | [46] |

| Methazolamide (pKa 7.3) | 236.26 | 0.004 | γCD | 0.04 | 1:26 | 0.96 | [45] |

| HPγCD | 0.05 | 1:21 | 0.95 | [45] | |||

| Naproxen (pKa 4.84)2 | 230.26 | 0.0056 | HPβCD | 1.29 | 1:1.8 | 0.44 | [50] |

| Triamcinolone acetonide | 434.50 | 0.0003 | HPβCD | 0.063 | 1:17 | 0.94 | [41] |

| Voriconazole (pKa 1.7) | 349.31 | 0.002 | αCD | 0.066 | 1:17 | 0.94 | [51] |

| βCD | 0.658 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [51] | |||

| RMβCD | 0.545 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [51] | |||

| HPβCD | 0.668 | 1:3 | 0.67 | [51] |

| Preservative | Comment | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Benzalkonium chloride (BAC) |

In aqueous solution the preservative efficacy was not affected by 0.5% HPβCD but 5% HPβCD had significant effect. | [10] |

| HPβCD and SBEβCD reduced antimicrobial efficacy of BAC, both in the presence and absence of 0.1% EDTA, and presence of competing drug (0.1% fluorometholone) had no effect. Aqueous eye drops containing 0.1% fluorometholone, 5% HPβCD, 0.02% BAC and 0.1% EDTA1 passed the USP antimicrobial efficacy test. | [52] | |

| Benzethonium chloride | 1.1% (10 mM) βCD results in almost 1000-fold increase in the MIC. | [53] |

| Benzoic acid (pKa 4.2) | Aqueous 1% citric acid1 solution containing 5% HPβCD passes the European Pharmacopoeia antimicrobial efficacy test at benzoic acid concentrations ≥0.15% at pH 4.0 and ≥0.36% at pH 5.0. | [14] |

| Chlorobutanol | In aqueous solution the preservative efficacy was not affected by 0.5% HPβCD but 5% HPβCD had significant effect. | [10] |

| m-Cresol | An exponential increase of m-cresol inactivation was observed with rising HPβCD concentration. | [15] |

| Methyl paraben | Aqueous 1% citric acid1 solution, pH 5.0, containing 5% HPβCD passes the USP and Eur. Ph. antimicrobial efficacy test at preservative concentrations ≥0.46%. | [14] |

| HPβCD and SBEβCD reduced antimicrobial efficacy, both in the presence and absence of 0.1% EDTA1, and the presence of competing drug (0.1% fluorometholone) had no effect. | [52] | |

| Thiomersal | Thimerosal is water soluble and a very potent antimicrobial preservative. The antimicrobial activity of thimerosal is not inhibited by 4.5% HPβCD. | [15,54] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).