1. Introduction

The “periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis” (PFAPA) syndrome is a shadowy disorder of childhood, which can be defined by the combination of periodically recurring fevers with nonspecific mucosal signs consisting of oral aphthosis and pharyngitis (either exudative or non-exudative), and cervical lymph node enlargement [

1]. There is no specific diagnostic test to strictly identify PFAPA children, and the disease can be suspected through the handful of “classical” clinical signs drafted by Marshall in 1987 from the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, then modified by Thomas in 1999, requiring that febrile attacks start within 5 years of age and that patients should not display any respiratory tract infection along with fevers, should be completely symptomless between febrile episodes, and should have unimpaired growth [

2]. A careful reconstruction of family history, considering patient’s ethnicity, nontypical symptoms suggesting specific causes of fever, and results of laboratory tests which turn to normal between PFAPA episodes can help sustaining PFAPA diagnosis and excluding the many other causes of recurrent fevers in a child [

3]. The evolution of the syndrome remains unpredictable in the long run.

The pathogenesis of PFAPA syndrome is not yet deciphered, warranting the hypothesis of a multifactorial origin probably based on a polygenic pattern of susceptibility; its treatment relies on the administration of one-shot low-dose corticosteroid at the febrile attack, which promptly aborts the flare, but cannot prevent the subsequent recurring fever episodes over time, which recur for an unpredictable lapse [

4,

5]. Tonsillectomy has also proved to be successful in some pediatric patients, but a larger experience confirming its efficacy is needed to tilt towards a primary surgical approach for PFAPA children [

6]. Furthermore, the increasing number of reports of PFAPA syndrome in adults has emphasized the misconception that this disorder could be limited to sole pediatric patients [

7,

8]. In this study related to a single-center cohort of children with a confirmed diagnosis of PFAPA syndrome, who were longitudinally assessed in the long term, we have retrospectively evaluated patients’ medical charts to define which general, demographic, clinical or laboratory clues might potentially influence the time required for disease resolution, i.e. full PFAPA disappearance, or predict disease persistence with a recurrent pattern over time.

2. Patients and Methods

We have retrospectively evaluated the medical charts of 153 Italian children with history of recurrent fevers in the Outpatients Clinic of Pediatric Rheumatology of our Institution, all without any evidence of chronic diseases, immune deficiencies or autoimmune disorders, who satisfied Marshall/Thomas and EuroFever criteria for diagnosing PFAPA syndrome during the period 2014-2024. The exclusion of hereditary monogenic autoinflammatory disorders by genetic analysis was performed in 25 patients (16.3% of the initial cohort), based on their ethnicity, medical history, or previous immunological investigations. During the follow-up evaluation two patients were excluded from the cohort, as they were found to have the P369S/R408Q MEFV mutations (consenting to accordingly diagnose familial Mediterranean fever) and the V377I/G347V MVK mutations (consenting to accordingly diagnose mevalonate kinase deficiency), respectively. One further patient was also excluded from the cohort as she developed signs of autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. No pathogenic mutations were found in the remainder of the genetically-tested PFAPA patients.

2.1. Inclusion of PFAPA Patients for the Retrospective Assessment

A total of 150 patients from the initial cohort were included in our assessment: 88 males, 62 females, mean age at onset of 2.5±1.7 years, age range of 0.3-9.4 years, mean age at diagnosis of 4.5±2.0 years. The study was conducted according to guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Local Ethical Committee as part of a larger protocol based on the evaluation of patients with complex or rare diseases (approval code from our Ethical Committee: 2105, approval date: 5 February 2019): all patients’ parents and/or their legal guardians signed an informed consent for a retrospective assessment. General, demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected analyzing patients’ medical charts: for each patient we longitudinally recorded anthropometric data since diagnosis, duration of fever episodes, duration of intervals between fever episodes, and the clinical manifestations occurring during attacks.

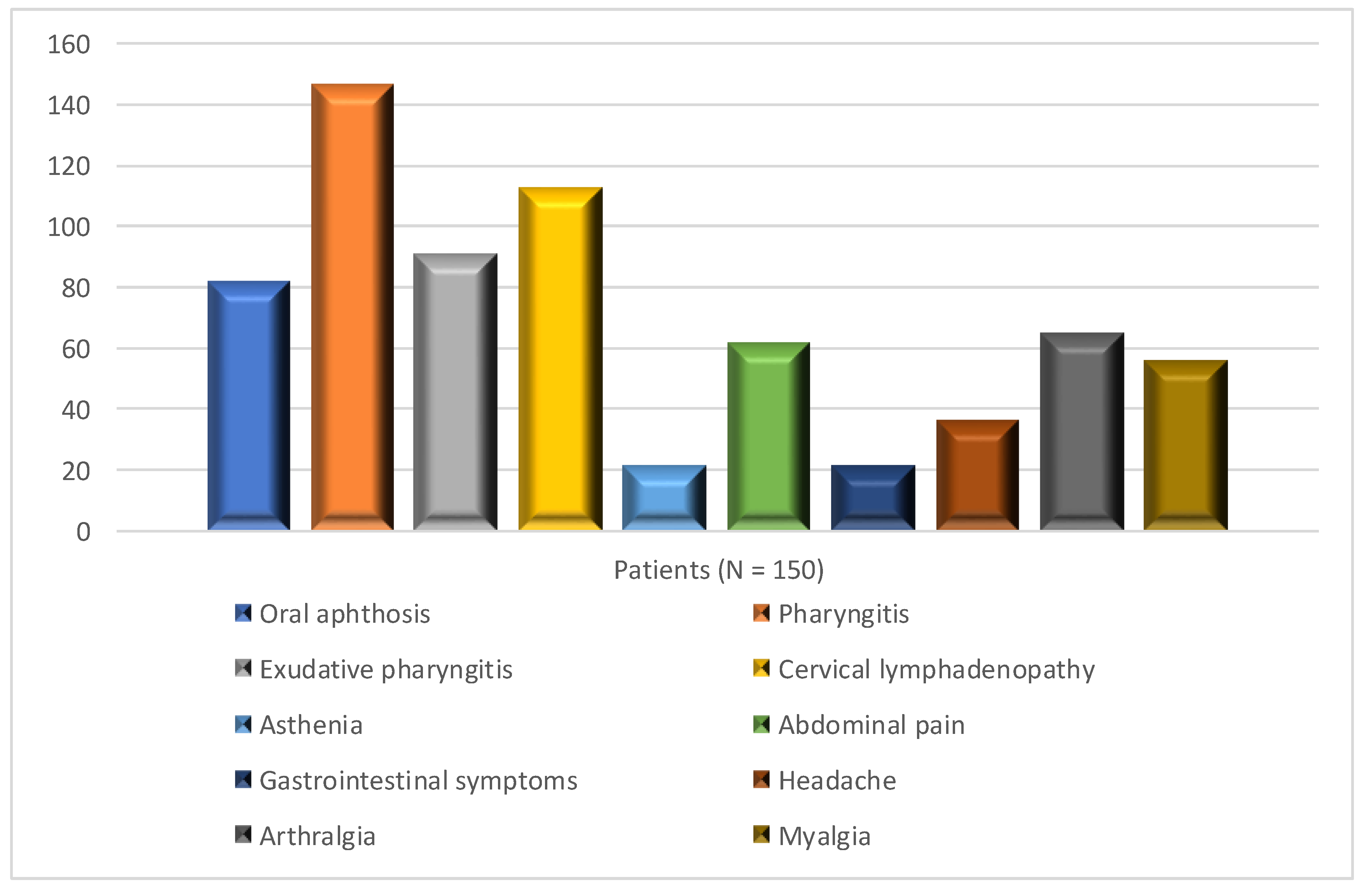

Figure 1 shows the phenotype displayed during flares by patients of the cohort. Infant’s birth weight, vitamin D supplementation at the period of PFAPA diagnosis, and auxological characteristics of patients were not considered by the study.

2.2. Data Related to Maternity Care and Breastfeeding

The medical charts of PFAPA patients were also used to retrieve further information related to mothers of each patient: maternal demographic, socio-economic characteristics including their ability to breastfeed their daughters or sons, and data about breastfeeding. No child of the cohort had any previous congenital malformations that might interfere with breastfeeding. Exclusive breastfeeding implied that the infant received only breast milk (without intake of non-human milk or other liquids), though allowing the child to receive vitamin supplementation. We also assessed the education level of patients' mothers, dividing them into two groups: high school diploma or graduation as having a high level of education, and middle school diploma or lower as having a low level of education; we chose this simple division to avoid comparing groups with smaller numbers of individuals. Mothers’ age, gestational age of pregnancy, modes of delivery, singleton or twin pregnancy were not evaluated by this assessment. Also mothers’ employment, marital status, type of maternity hospital (in residential or country areas), body mass index before pregnancy, and previous breastfeeding experience were not considered as well as smoking habits and caffeine consumption before conception, antepartum and postpartum. Any eventual correlations with the COVID19 pandemic (during the period 2020-2022) were not considered.

2.3. Management of PFAPA Patients

All children of the cohort were followed-up for a median period of 5 years (IQR: 4-7): in particular, patients displaying the resolution of PFAPA syndrome were followed-up for 6 years (IQR: 5-9), while the follow-up lasted 5 years (IQR: 4-6,75) for those having persistent PFAPA symptoms (

p=0.16). All patients were treated with one-shot low-dose corticosteroids given during the febrile attack, and this strategy was successful in 143 cases (95%), leading to disease disappearance in 125 (83%) after a variable period of time with no mid-long term sequelae. Tonsillectomy was performed in 9 patients who had persistent recurrent fevers and persistent oral manifestations in spite of on-demand corticosteroid administration. Finally, 23 patients (15.3% of the cohort) were treated with oral supplementation of

Streptococcus salivarius K12, as this probiotic given for at least 6 months had been found to mitigate febrile attacks in PFAPA patients [

9].

2.4. Statistical Analysis Performed in the Study

The statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS version 25. Continuous data were presented using the mean and standard deviation for normally distributed data, and the median and interquartile range for non-normally distributed data. Dichotomous data were described as counts and percentages of the total. To compare continuous variables we used the Student's t-test (for normally distributed data) and the Mann-Whitney test (for non-normally distributed data). To compare prevalence we used the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test (the latter if the count in a group was less than 6). We also performed a multivariate analysis using multinomial logistic regression, including all variables that had a p-value less than 0.15 at the univariate analysis, and adjusting data for sex and age. A p less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

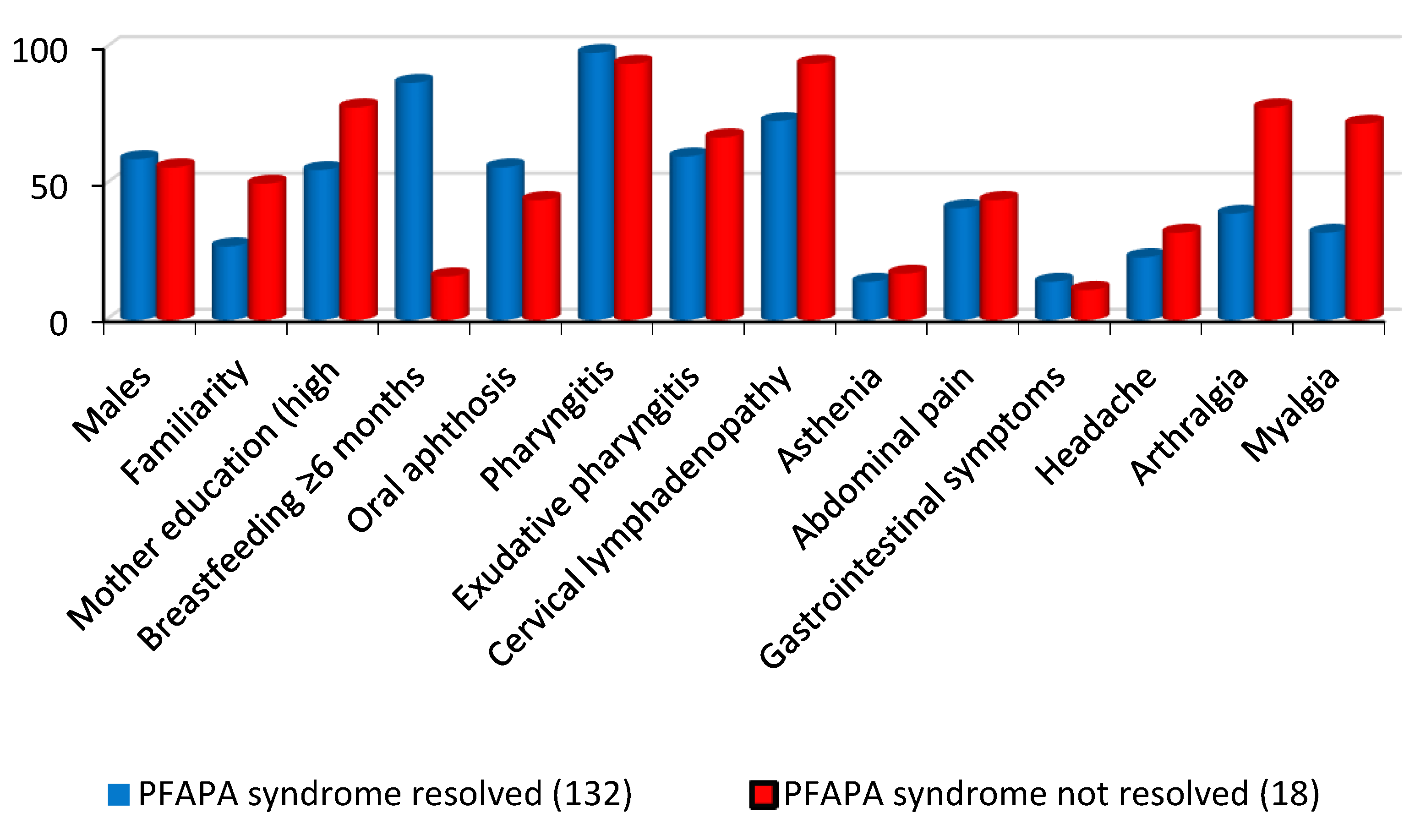

After dividing PFAPA patients into two groups based on the disappearance or persistence of PFAPA symptoms during the follow-up we found that family history of recurring fevers, presence of cervical lymphadenopathy, presence of arthralgia and myalgia during attacks were associated with the persistence of PFAPA syndrome. Conversely, breastfeeding for more than 6 months was associated with the resolution of all recurring PFAPA symptoms (

Table 1,

Figure 2).

Performing a multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and age, we found that only breastfeeding for more than 6 months and a higher level of maternal education remained independently associated with a disappearance of PFAPA symptoms (see

Table 2).

4. Discussion

Systemic autoinflammatory disorders represent a rising spectrum of diseases stamped by dysregulation of the innate immune system: PFAPA syndrome is the most frequent multi-factorial autoinflammatory-based disorder, as a genetic basis with a specific inheritance pattern are yet unknown, though many reports had shown a familial clustering of the disease [

10]. The screening of genes involved in inherited autoinflammatory syndromes or encoding components of the human inflammasome, including

MEFV,

TNFRSF1A,

MVK or

NLRP3, showed no DNA variants that could be linked to PFAPA molecular pathology in a monogenic fashion [

11]. New hypothetical genetic susceptibility loci for PFAPA suggest that this might be a complex genetic disorder linked to Behçet's disease, A20 haploinsufficiency and/or recurrent aphthous ulcers [

12].

There is no identifiable infectious agent in the etiology of PFAPA syndrome, though many of these children are often treated with antimicrobials. In the PFAPA there is an increased expression of various inflammatory cytokines, especially interleukin (IL)-1β as a result of inflammasome overactivity. Moreover, febrile PFAPA attacks are characterized by significantly increased serum levels of IL-6 and interferon-γ compared to symptom-free periods [

13]. In a recent pediatric study serum levels of IL-4 were significantly reduced in PFAPA children compared with cases of recurrent tonsillitis alone [

14].

The outcome of PFAPA syndrome is unpredictable, though it generally resolves itself over a variable period with no sequelae: the recurring PFAPA clinical picture may be related to rhythmic variations in physiological processes mediated by both endogenous and exogenous factors as changes in ratio of microflora elements of the oropharyngeal mucosa.

Environmental factors may be relevant to both pathogenesis and evolution of PFAPA symptoms: a Finnish case-control study showed that maternal smoking was more common among mothers of PFAPA children than in mothers of healthy controls (23

versus 14%,

p=0.005) and that the first had lower breastfeeding rates in comparison with controls (94

versus 99%,

p=0.006) [

15]. Furthermore, it is known that early intestinal flora in children can be determined by gestational age, mode of delivery, or nutrition habits, all influencing a regular microbiome functional development, and that gut microbiota elicits effects on the promotion of entero-endocrine signaling and innate immunity within the gut epithelial barrier [16]. The overall gut microbiota composition has been correlated with different childhood diseases; however the exact microbial contributions to the origin of this disease remain unclear.

Common knowledge is benefit to the infant deriving from breastfeeding, which has been related with a lower rate of infectious diseases, obesity and hypertension, following gut microbiota colonization through communities of microorganisms co-evolving with the host and involved in nutrient absorption and metabolism [

17,

18]. In particular, breastfeeding has been linked to the development of a specific microbiota ‘within’ the mouth, ensuring local immunity with proactive commensal flora and beneficial host-flora interactions [

19]. Breastfeeding might have a protective effect for some childhood immune-mediated disorders like Kawasaki disease as well as several autoimmune disorders.

Na et al. performed a nationwide cohort study in South Korea to explore the relationship of environmental factors with Kawasaki disease, including almost 2.000.000 infants. The most prevalent feeding type in these children was exclusive breastfeeding (41.5%) and, at the 1 year-follow-up, 3,854 (0.2%) of these infants had developed Kawasaki disease, hypothesizing that breastfeeding could protect children by disease development [

20]. Guo et al. performed a retrospective cohort study related to 249 children with Kawasaki disease, analyzing breastfeeding rates in the first 6 months of life and finding that it was associated with a shorter duration of fever and lower risk of persistent coronary artery abnormalities [

21].

A Turkish study evaluated 182 patients diagnosed with acute rheumatic fever between 2010 and 2019, divided into groups according to the presence of carditis; patients’ demographic, socio-economic, and breastfeeding data were compared between groups, and breast milk intake for less than 6 months was shown as an independent predictor for the development of carditis [

22]. Definitely, breastfeeding remains a cornerstone of child’s healthy development, as it provides crucial nutritional components and numerous biologically active molecules for a regular microbiota settlement [

23]. However, barriers to adhering to breastfeeding recommendation exist, often resulting in a lack of initiation or in a premature cessation of breastfeeding. In fact, the World Health Organization European Regions have the lowest rates of exclusive breastfeeding due to socio-cultural features, characteristics of the health-care services, institutional policies, and public health frameworks [

24].

The association between exclusive breastfeeding and its overall duration with the onset of PFAPA syndrome has not been elucidated so far. On the other hand, the clock-work periodism of PFAPA syndrome might derive from a rhythmic défaillance in the regulation of innate immunity within the oral cavity, which may periodically recur due to the disrupted recognition of resident microbial communities as commensals, triggering an autoinflammatory response [

25].

Our observation suggests that breastfeeding for more than 6 months can be associated with self-resolution of PFAPA syndrome for children who will develop this disorder during infancy. Furthermore, the multivariate analysis adjusted for sex and age reveals that only exclusive breastfeeding for more than 6 months and a higher level of education for PFAPA patients’ mothers are independently associated with resolution of PFAPA symptoms. In 6% of the cohort with persistent PFAPA symptoms, we programmed performing tonsillectomy, which led to the PFAPA resolution in 6 of them (66.6%). Additionally, 23 patients (15,3%) were given probiotic therapy with Streptococcus salivarius K12: out of these, 9 showed a complete remission (39,1%). The PFAPA syndrome generally recovers by its own, but children who do not manifest a tendency to remission after ‘on demand’ one-shot corticosteroid therapy may be addressed to tonsillectomy, while the use of Streptococcus salivarius K12 given per os may also be a suitable therapeutic tool.

This evaluation of ours is a simple snapshot related to children affected with PFAPA syndrome and has several limitations: various factors might have an impact on breastfeeding initiation and duration. These factors were not considered by this retrospective study, including child’s birth weight, mother’s body mass index, promotion of different feeding practices following midwife-led antenatal breastfeeding counseling and support during the breastfeeding period, etc.

5. Conclusions

Environmental factors can be important in the evolution of PFAPA syndrome, though they should be further evaluated in future studies considering larger samples of patients from different countries and cultures to help clinicians and mothers in optimizing the infant microbiota throughout infancy and later life, and better evaluating whether differences in breastfeeding indicators might ostensibly influence the outcome of PFAPA syndrome during childhood.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, D.R..; methodology, M.C.; investigation, D.R.; formal analysis, M.C..; data curation, D.R. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.; writing—review and editing, D.R. Both authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore, Rome, Italy (protocol code: 2015, date of approval: February 5th 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parents or caregivers of patients considered in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the families of children who gave their written consent for the participation to this retrospective study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rigante D. When, how, and why do fevers hold children hostage? J Evid Based Med 2020, 13, 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/jebm.12377.

- Manthiram K. What is PFAPA syndrome? Genetic clues about the pathogenesis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2023, 35, 423–428. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000956.

- Rigante D, Frediani B, Galeazzi M, Cantarini L. From the Mediterranean to the sea of Japan: the transcontinental odyssey of autoinflammatory diseases. Biomed Res Int 2013, 2013: 485103. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/485103.

- Okamoto CT, Chaves HL, Schmitz MJ. Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis syndrome in children: a brief literature review. Rev Paul Pediatr 2022, 40: e2021087. https://doi.org/10.1590/1984-0462/2022/40/2021087IN.

- Gardner NJ. PFAPA syndrome in children. JAAPA 2023, 36, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.JAA.0000977712.81696.b9.

- Ohnishi T, Sato S, Uejima Y, Kawano Y, Suganuma E. Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis syndrome: clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes - a single center study in Japan. Pediatr Int 2022, 64, e15294. https://doi.org/10.1111/ped.15294.

- Rigante D, Vitale A, Natale MF, Lopalco G, Andreozzi L, Frediani B, D’Errico F, Iannone F, Cantarini L. A comprehensive comparison between pediatric and adult patients with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenopathy (PFAPA) syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2017, 36, 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-016-3317-7.

- Sicignano LL, Rigante D, Moccaldi B, Massaro MG, Delli Noci S, Patisso I, Capozio G, Verrecchia E, Manna R. Children and adults with PFAPA syndrome: similarities and divergences in a real-life clinical setting. Adv Ther 2021, 38, 1078–1093. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-020-01576-8.

- La Torre F, Sota J, Insalaco A, Conti G, Del Giudice E, Lubrano R, Breda L, Maggio MC, Civino A, Mastrorilli V, Loconte R, Natale MF, Celani C, Romeo M, Patroniti S, Gentile C, Vitale A, Caggiano V, Gaggiano C, Diomeda F, Cattalini M, Lopalco G, Emmi G, Parronchi P, Gentileschi S, Cardinale F, Aragona E, Shahram F, Marino A, Barone P, Moscheo C, Ozkiziltas B, Carubbi F, Alahmed O, Iezzi L, Ogunjimi B, Mauro A, Tarsia M, Mahmoud AAA, Giardini HAM, Sfikakis PP, Laskari K, Więsik-Szewczyk E, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Frediani B, Gómez-Caverzaschi V, Tufan A, Almaghlouth IA, Balistreri A, Ragab G, Fabiani C, Cantarini L, Rigante D. Preliminary data revealing efficacy of Streptococcus salivarius K12 (SSK12) in Periodic Fever, Aphthous stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and cervical Adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: a multicenter study from the AIDA Network PFAPA syndrome registry. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10: 1105605. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2023.1105605.

- Valenzuela PM, Majerson D, Tapia JL, Talesnik E. Syndrome of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) in siblings. Clin Rheumatol 2009 Oct;28,1235-7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-009-1222-z.

- Dagan E, Gershoni-Baruch R, Khatib I, Mori A, Brik R. MEFV, TNF1rA, CARD15 and NLRP3 mutation analysis in PFAPA. Rheumatol Int 2010 Mar;30,633-6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-009-1037-x.

- Aeschlimann FA, Laxer RM. Haploinsufficiency of A20 and other paediatric inflammatory disorders with mucosal involvement. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2018 Sep;30,506-13. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000532.

- Stojanov S, Hoffmann F, Kéry A, Renner ED, Hartl D, Lohse P, Huss K, Fraunberger P, Malley JD, Zellerer S, Albert MH, Belohradsky BH. Cytokine profile in PFAPA syndrome suggests continuous inflammation and reduced anti-inflammatory response. Eur Cytokine Netw 2006 Jun;17,90-7.

- Nakano S, Kondo E, Iwasaki H, Akizuki H, Matsuda K, Azuma T, Sato G, Kitamura Y, Abe K, Takeda N. Differential cytokine profiles in pediatric patients with PFAPA syndrome and recurrent tonsillitis. J Med Invest 2021,68(1.2):38-41. doi: 10.2152/jmi.68.38.

- Kettunen S, Lantto U, Koivunen P, Tapiainen T, Uhari M, Renko M. Risk factors for periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: a case-control study. Eur J Pediatr 2018, 177, 1201–1206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-018-3175-1.

- Jiao Y, Wu L, Huntington ND, Zhang X. Crosstalk between gut microbiota and innate immunity and its implication in autoimmune diseases. Front Immunol 2020, 11: 282. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00282.

-

Breastfeeding-related health benefits in children and mothers: vital organs perspective. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 1535. [CrossRef]

- Notarbartolo V, Giuffrè M, Montante C, Corsello G, Carta M. Composition of human breast milk microbiota and its role in children's health. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr 2022, 25, 194–210. https://doi.org/10.5223/pghn.2022.25.3.194.

- Davis JA, Baumgartel K, Morowitz MJ, Giangrasso V, Demirci JR. The role of human milk in decreasing necrotizing enterocolitis through modulation of the infant gut microbiome: a scoping review. J Hum Lact 2020, 36, 647–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334420950260.

- Na JY, Cho Y, Lee J, Yang S, Kim YJ. Immune-modulatory effect of human milk in reducing the risk of Kawasaki disease: a nationwide study in Korea. Front Pediatr 2022, 10: 1001272. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.1001272.

- Guo MM, Tsai IH, Kuo HC. Effect of breastfeeding for 6 months on disease outcomes in patients with Kawasaki disease. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0261156. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261156.

- Gurbuz F, Canbulat Sahiner N, Unal E, Gurbuz AS, Baysal T. Breastfeeding does not protect against the development of carditis in children with acute rheumatic fever. Cardiol Young 2022 Jun 20: 1-5. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951122001834.

- Spatz DL. Breastfeeding is the cornerstone of childhood nutrition. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2012, 41, 112–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01312.x.

- Bagci Bosi AT, Eriksen KG, Sobko T, Wijnhoven TM, Breda J. Breastfeeding practices and policies in WHO European Region Member States. Public Health Nutr 2016, 19, 753–764. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980015001767.

- Rigante, D. Febrile children with breaches in the responses of innate immunity. Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2023, 19, 1293-1298. https://doi.org/10.1080/1744666X.2023.2240960.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).