Submitted:

29 October 2024

Posted:

30 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Survey Instrument

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

2.4. Ethical Considerations

2.5. Data Analysis

3. Results

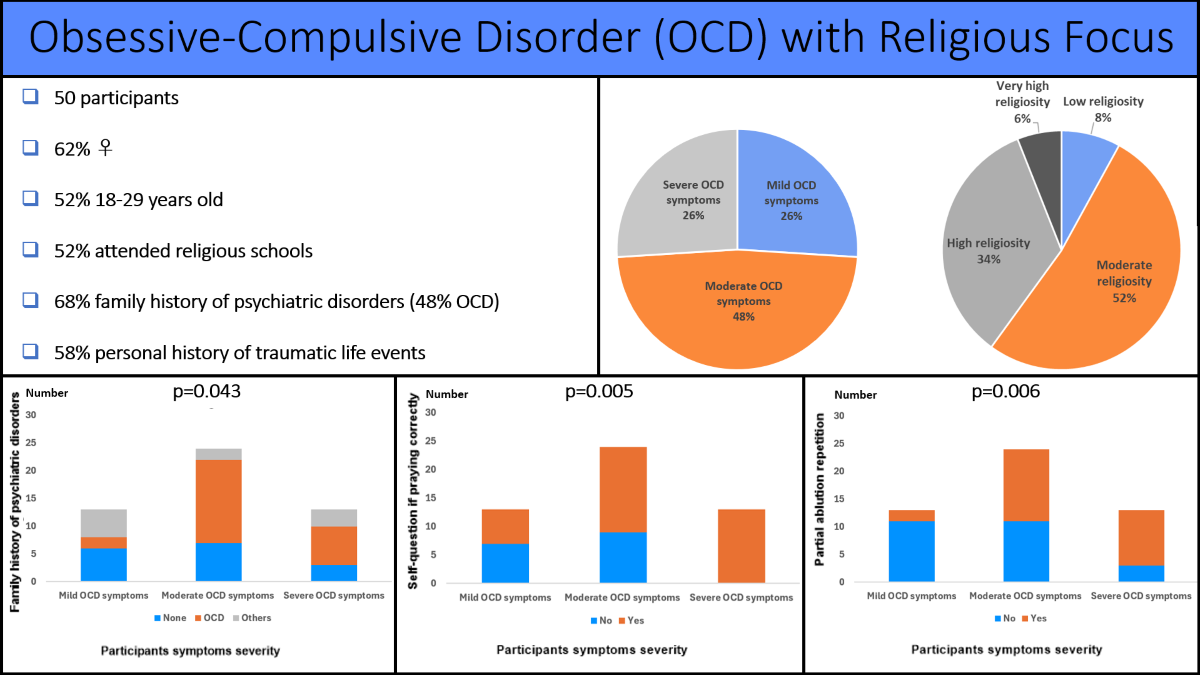

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

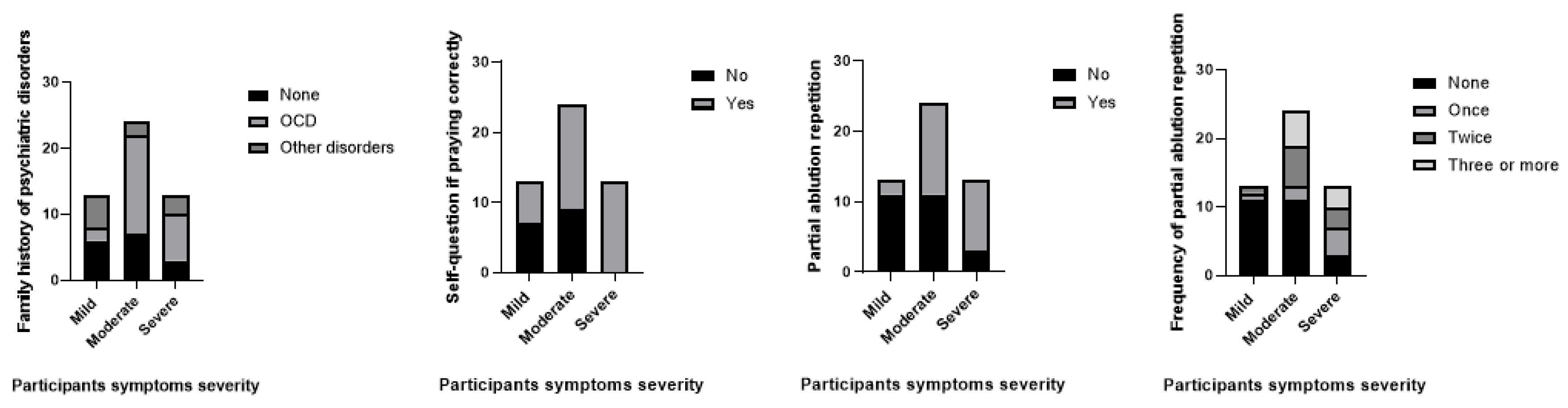

3.2. Bivariate Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics

4.2. Religiosity and Spirituality

4.3. Limitations and Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hirschtritt, M.E.; Bloch, M.H.; Mathews, C.A. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Advances in Diagnosis and Treatment. JAMA. 2017, 317, 1358–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chalah, M.A.; Ayache, S.S. Could Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation Join the Therapeutic Armamentarium in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stein, D.J.; Costa, D.L.C.; Lochner, C.; Miguel, E.C.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Shavitt, R.G; et al. Obsessive–compulsive disorder. Vol. 5, Nature Reviews Disease Primers; Nature Publishing Group, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, H.; Hany, M. Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. 2023 May 29. In StatPearls [Internet]; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 29 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.), 2022.

- Karam, E.G.; Mneimneh, Z.N.; Karam, A.N.; Fayyad, J.A.; Nasser, S.C.; Chatterji, S.; et al. Prevalence and treatment of mental disorders in Lebanon: a national epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2006, 367, 1000–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezani, Z.; Rahimi, C.; Mohammadi, N. Birth Order and Sibling Gender Ratio of a Clinical Sample Predicting Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Subtypes Using Cognitive Factors. Iranian J Psychiatry. Iran J Psychiatry. 2016, 11, 75–81. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, D.J.; Costa, D.L.C.; Lochner, C.; Miguel, E.C.; Reddy, Y.C.J.; Shavitt, R.G.; et al. Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palermo, S.; Marazziti, D.; Baroni, S.; Barberi, F.M.; Mucci, F. The Relationships Between Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Psychosis: An Unresolved Issue. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2020, 17, 149–157. [Google Scholar]

- Thorsen, A.L.; Kvale, G.; Hansen, B.; van den Heuvel, O.A. Symptom dimensions in obsessive-compulsive disorder as predictors of neurobiology and treatment response. Curr. Treat. Options Psychiatry. 2018, 5, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, B.P.; Wang, D.; Li, M.; Perriello, C.; Ren, J.; Elias, J.A.; et al. Use of an Individual-Level Approach to Identify Cortical Connectivity Biomarkers in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Boil. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2019, 4, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Himle, J.A.; Chatters, L.M.; Taylor, R.J.; Nguyen, A. The relationship between obsessive-compulsive disorder and religious faith: Clinical characteristics and implications for treatment. Psycholog Relig Spiritual. 2011, 3, 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, D.; Huppert, J.D. Scrupulosity: a unique subtype of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010, 12, 282–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolini, H.; Salin-Pascual, R.; Cabrera, B.; Lanzagorta, N. Influence of Culture in Obsessive-compulsive Disorder and Its Treatment. Curr Psychiatry Rev. 2017, 13, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besiroglu, L.; Karaca, S.; Keskin, I. Scrupulosity and obsessive compulsive disorder: the cognitive perspective in Islamic sources. J Relig Health. 2014, 53, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yorulmaz, O.; Gençöz, T.; Woody, S. OCD cognitions and symptoms in different religious contexts. J Anxiety Disord. 2009, 23, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinker, M.; Jaworowski, S.; Mergui, J. [Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in the ultra-orthodox community--cultural aspects of diagnosis and treatment]. Harefuah. 2014, 153, 463–466, 498, 497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Khoubila, A.; Kadri, N. [Religious obsessions and religiosity]. Can J Psychiatry. 2010, 55, 458–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badaan, V.; Richa, R.; Jost, J.T. Ideological justification of the sectarian political system in Lebanon. Curr Opin Psychol. 2020, 32, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baytiyeh, H. Has the Educational System in Lebanon Contributed to the Growing Sectarian Divisions? Educ. Urban Soc. 2017, 49, 546–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. The development and validation of the Arabic Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Eur J Psychol Assess. 1998, 14, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. Manual of the Arabic Scale of Obsession-compulsion; The Anglo-Egyptian Bookshop: Cairo, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Abdel-Khalek, A.M. (2018). The construction and validation of the revised Arabic Scale of Obsession-Compulsion (ASOC). Online J Neurol Brain Disord. 2018, 1, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Metwally Elsayed, M.; Ahmed Ghazi, G. Fear of covid-19 pandemic, obsessive-compulsive traits and sleep quality among first academic year nursing students, Alexandria University, Egypt. Egypt. J. Health Care. 2021, 12, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatch, R. L.; Burg, M. A.; Naberhaus, D.S.; Hellmich, L.K. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale. Development and testing of a new instrument. J Fam Pract. 1998, 46, 476–86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Musa, A.S. Psychometric Evaluation of an Arabic Version of the Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale in Jordanian Muslim College Nursing Students. J. Educ. Pract. 2015, 6, 64–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, B. M.; Morabito, D. M.; Schmidt, N.B. Epidemiological and Clinical Gender Differences in OCD. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019, 21, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benatti, B.; Girone, N.; Celebre, L.; Vismara, M.; Hollander, E.; Fineberg, N. A.; et al. The role of gender in a large international OCD sample: A Report from the International College of Obsessive-Compulsive Spectrum Disorders (ICOCS) Network. Compr Psychiatry. 2022, 116, 152315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathis, M.A.; Alvarenga, P.D.; Funaro, G.; Torresan, R.C.; Moraes, I.; Torres, A. R.; et al. Gender differences in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a literature review. Braz J Psychiatry, 2011, 33, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, W.; El Hayek, S.; de Filippis, R.; Eid, M.; Hassan, S.; Shalbafan, M. Variations in obsessive compulsive disorder symptomatology across cultural dimensions. Front Psychiatry. 2024, 15, 1329748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachander, S.; Meier, S.; Matthiesen, M.; Ali, F.; Kannampuzha, A.J.; Bhattacharya, M.; et al. Are There Familial Patterns of Symptom Dimensions in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder? Frontiers Psychiatry. 2021, 12, 651196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.H.; Cheng, C.M.; Tsai, S.J.; Bai, Y.M.; Li, C.T.; Lin, W.C.; et al. Familial coaggregation of major psychiatric disorders among first-degree relatives of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: a nationwide study. Psychol Med. 2021, 51, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromer, K.R.; Schmidt, N. B.; Murphy, D.L. An investigation of traumatic life events and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007, 45, 1683–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, G.; Albert, U.; Asinari, G.F.; Bogetto, F.; Maina, G. Stressful life events and obsessive-compulsive disorder: clinical features and symptom dimensions. Psychiatry Res. 2012, 197, 259–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K.; Nakao, T.; Ohno, A.; Tsuruta, S.; Tomiyama, H.; Hasuzawa, S.; et al. Impacts of Stressful Life Events and Traumatic Experiences on Onset of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. Frontiers Psychiatry. 2020, 11, 561266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, M.L.; Brock, R.L. The effect of trauma on the severity of obsessive-compulsive spectrum symptoms: A meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2017, 47, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahgoub, O.M.; Abdel-Hafeiz, H.B. Pattern of obsessive-compulsive disorder in Eastern Saudi Arabia. Br J Psychiatry. 1991, 158, 840–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abramowitz, J.S.; Buchholz, J.L. Chapter 4 - Spirituality/religion and obsessive–compulsive-related disorders. Handbook of Spirituality, Religion, and Mental Health (Second Edition). 2020, 61-78.

- Rakesh, K.; Arvind, S.; Dutt, B.P.; Mamta, B.; Bhavneesh, S.; Kavita, M.; et al. The Role of Religiosity and Guilt in Symptomatology and Outcome of Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2021, 51, 38–49. [Google Scholar]

- Inozu, M.; Ulukut, F.O.; Ergun, G.; Alcolado, G.M. The mediating role of disgust sensitivity and thought-action fusion between religiosity and obsessive compulsive symptoms. Int J Psychol. 2014, 49, 334–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A.D.; Lau, G.; Grisham, J.R. Thought-action fusion as a mediator of religiosity and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2013, 44, 207–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rassin, E.; Muris, P.; Schmidt, H.; Merckelbach, H. Relationships between thought-action fusion, thought suppression and obsessive-compulsive symptoms: a structural equation modeling approach. Behav Res Ther. 2000, 38, 889–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mild (n=13) | Moderate (n=24) | Severe (n=13) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Age 18-29 years 30-49 years ≥50 years |

5 7 1 |

13 11 0 |

8 5 0 |

0.489 |

|

Sex Females Males |

5 8 |

17 7 |

9 4 |

0.162 |

|

Educational level Middle school High school University degree |

1 2 10 |

1 9 14 |

1 0 12 |

0.057 |

|

Relationship status Single Married Divorced |

6 6 1 |

13 10 1 |

4 8 1 |

0.713 |

|

Area of living (childhood) Outside the capital Within the capital |

10 3 |

20 4 |

11 2 |

0.897 |

|

Area of living (current) Outside the capital Within the capital |

10 3 |

19 5 |

11 2 |

>0.999 |

|

Monthly living income (Lebanese pounds and equal rates in USD) <2 millions (~22 USD) Between 2 & 5 millions (~22-56 USD) Between 5 & 10 millions (56 –112 USD) Between 10 & 20 millions (112-224 USD) >20 millions (>224 USD) |

0 3 4 2 4 |

3 14 2 3 2 |

2 6 1 2 2 |

0.240 |

|

Attended school Religious Non-religious Both |

3 6 4 |

5 13 6 |

4 5 4 |

0.913 |

|

Parents’ relationship status Married Divorced Widowed |

12 0 1 |

18 4 2 |

11 1 1 |

0.650 |

|

Traumatic life events No Yes |

7 6 |

9 15 |

5 8 |

0.662 |

|

Age of diagnosis Before 12 years 12-18 years 18-25 years >25 years |

2 0 6 5 |

1 8 9 6 |

1 1 7 4 |

0.184 |

|

Family history of psychiatric illness None OCD Others |

6 2 5 |

7 15 2 |

3 7 3 |

0.043 |

|

Current OCD medications Untreated Treated |

7 6 |

10 14 |

10 3 |

0.119 |

|

Current or past psychotherapy None Past Current |

9 1 3 |

12 7 5 |

6 5 2 |

0.482 |

|

Praying frequency Rarely Irregularly Daily or weekly |

0 1 12 |

1 2 21 |

0 3 10 |

0.702 |

|

Self-question if praying correctly No Yes |

7 6 |

9 15 |

0 13 |

0.005 |

|

Self-question if prayers are accepted by God No Yes |

4 9 |

10 14 |

1 12 |

0.111 |

|

Frequency of prayers repetition if questioning None Once Twice Three of more |

9 1 1 2 |

14 2 6 2 |

5 5 3 0 |

0.162 |

|

Praying location No preference As long as the setting is available Home only Home & praying place |

7 1 3 2 |

16 1 4 3 |

6 2 2 3 |

0.830 |

|

Frequency of partial ablution Daily 3-5/day More than 5/day |

12 1 |

18 6 |

12 1 |

0.404 |

|

Partial ablution repetition No Yes |

11 2 |

11 13 |

3 10 |

0.006 |

|

Frequency of partial ablution repetition None Once Twice Three or more |

11 1 1 0 |

11 2 6 5 |

3 4 3 3 |

0.041 |

|

Partial ablution location No preference Home only Home & praying place |

6 5 2 |

15 9 0 |

4 5 4 |

0.058 |

|

Full ablution repetition No Yes |

10 3 |

16 8 |

5 8 |

0.123 |

|

Frequency of full ablution repetition None Once Twice Three of more |

10 2 1 0 |

16 4 2 2 |

5 4 0 4 |

0.166 |

|

Frequency of fasting practice None During the holy month 1-6 months per year Throughout the year during religious ceremony |

0 10 3 0 |

3 11 5 5 |

0 6 5 2 |

0.252 |

|

Self-question if fasting correctly No Yes |

10 3 |

16 8 |

6 7 |

0.282 |

|

Self-question if fasting accepted by God No Yes |

9 4 |

15 9 |

7 6 |

0.703 |

|

Frequency of fasting repetition None Rarely Sometimes |

10 2 1 |

21 1 2 |

9 1 3 |

0.495 |

|

Frequency of suspecting intrusive thoughts related to ritual impurity None Sometimes > once per month > once per week > once per day |

6 1 0 3 3 |

6 3 1 2 12 |

2 1 0 1 9 |

0.365 |

|

Frequency of attempts to correct suspected ritual impurities None Rarely Sometimes Every time |

6 1 1 5 |

6 1 4 13 |

2 0 1 10 |

0.445 |

|

Blasphemous thoughts No Yes |

10 3 |

13 11 |

8 5 |

0.459 |

|

Skeptical thoughts regarding the holy book No Yes |

11 2 |

19 5 |

11 2 |

>0.999 |

|

Skeptical thoughts regarding religious scripts or prophetic Hadiths No Yes |

8 5 |

16 8 |

9 4 |

>0.999 |

|

Perceived parents’ religiosity No Practice Low moderate High Very high |

0 2 7 3 1 |

0 5 11 5 3 |

1 0 5 7 0 |

0.221 |

|

Perceived self-religiosity Low moderate High Very high |

0 8 5 0 |

4 12 8 0 |

0 6 4 3 |

0.104 |

|

Frequency of visiting religious places/centers None Rarely Religious occasions Sometimes Weekly Daily |

2 2 3 2 3 1 |

6 1 3 6 7 1 |

1 1 4 2 4 1 |

0.864 |

| SIBS scores | 78.54±10.65 |

83.38±6.03 |

82.15±10.96 |

0.277 |

| Mann-Whitney or Kruskal Wallis test statistics | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | H=3.044 | 0.218 |

| Sex | U=232.000 | 0.211 |

| Educational level | H=2.845 | 0.416 |

| Relationship status | H=0.248 | 0.884 |

| Area of living (childhood) | U=180.500 | 0.921 |

| Area of living (current) | U=193.000 | 0.877 |

| Monthly living income (Lebanese pounds) | H=4.266 | 0.371 |

| Attended school | H=0.915 | 0.633 |

| Parents’ relationship status | H=0.120 | 0.942 |

| Traumatic life events | U=365.500 | 0.230 |

| Age of diagnosis | H=0.611 | 0.894 |

| Family history of psychiatric illness | H=4.419 | 0.110 |

| Current OCD medications | U=248.00 | 0.223 |

| Current or past psychotherapy | H=1.665 | 0.435 |

| Praying frequency | H=1.386 | 0.500 |

| Self-question if praying correctly | U=390.000 | 0.014 |

| Self-question if prayers are accepted by God | U=300.000 | 0.427 |

| Frequency of prayers repetition if questioning | H=3.552 | 0.314 |

| Praying location | H=1.506 | 0.681 |

| Frequency of partial ablution | U=189.000 | 0.594 |

| Partial ablution repetition | U=425.500 | 0.028 |

| Frequency of partial ablution repetition | H=6.785 | 0.079 |

| Partial ablution location | H=0.600 | 0.741 |

| Full ablution repetition | U=13.000 | 0.560 |

| Frequency of full ablution repetition | H=6.832 | 0.077 |

| Frequency of fasting practice | H=1.120 | 0.772 |

| Self-question if fasting correctly | U=368.500 | 0.103 |

| Self-question if fasting accepted by God | U=342.000 | 0.342 |

| Frequency of fasting repetition | H=1.038 | 0.595 |

| Frequency of suspecting intrusive thoughts related to ritual impurity | H=3.653 | 0.455 |

| Frequency of attempts to correct suspected ritual impurities | H=1.933 | 0.586 |

| Blasphemous thoughts | U=338.500 | 0.379 |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding the holy book | U=209.500 | 0.534 |

| Skeptical thoughts regarding religious scripts or prophetic Hadiths | U=289.500 | 0.854 |

| Perceived parents’ religiosity | H=7.912 | 0.095 |

| Perceived self-religiosity | H=3.146 | 0.370 |

| Frequency of visiting religious places/centers | H=1.533 | 0.199 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).