1. Introduction

The

CEP290 gene plays a crucial role in the assembly and regulation of the cilia, especially in photoreceptors, where it is essential to mantain the structure and function of the connecting cilium [

1]. This region is pivotal for protein and vesicle transport, which supports photoreceptor activity. Given its high expression in photoreceptors and nasal mucosa, CEP290 dysfunction leads to significant disruptions in these tissues, contributing to a variety of ciliopathies, syndromic and non-syndromic alike [

1,

2]. Pathogenic variants in

CEP290 are well-documented for their association with severe, early-onset inherited retinal dystrophies (IRDs), both in syndromic forms

, such as Joubert syndrome 5 (JBTS5, MIM#6101889), Senior-Loken syndrome 6 (SLSN6, MIM#610189) and Meckel syndrome 4 (MKS1, MIM#611134), and non-syndromic forms, including Leber congenital amaurosis 10 (LCA10, MIM#611755) [

1,

3]. In these cases, patients typically exhibit progressive and severe retinal degeneration beginning in early childhood. This had reinforced the perception that

CEP290-related IRDs follow an aggressive clinical course [

4,

5]. However, recent studies suggest that the phenotypic spectrum of

CEP290 variants is broader than initially thought [

6,

7,

8]. In addition to severe cases, a subset of individuals with

CEP290 variants may exhibit milder, slower progressing forms of retinal dystrophy [

8]. These cases offer valuable insights into genotype-phenotype correlations and challenge prior assumptions regarding the clinical trajectory of

CEP290-related diseases. In this report, we present two siblings with biallelic

CEP290 variants who present distinct non-syndromic IRD phenotypes: one sibling exhibits the expected severe retinal dystrophy, while the other has a notably milder, slowly progressing form of the disease. By characterizing this phenotypic variability, our objective is to expand the understanding of

CEP290-related IRDs and provide more nuanced information for genetic counseling and patient management.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ophtalmologic Evaluation

Both probands underwent comprehensive ophthalmological assessments. Best-corrected visual acuity was measured using the ETDRS chart, and biomicroscopy was performed using slit-lamp examination. Tropicamide was administered to dilate the pupils, allowing for a detailed fundus examination. Retinal imaging, including both fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and retinography, was obtained using Optos ultra-widefield (UWF™) retinal imaging (Optos California, Optos plc). To assess the retinal layers and detect structural abnormalities, swept-source optical coherence tomography (OCT) (Topcon Triton, Topcon Corporation) was performed. Retinal function was evaluated through central visual field testing (CV 10.2) and electrophysiology (Roland Consult), including full-field electroretinography (ffERG) and multifocal electroretinography (mfERG), and following the current standards of the International Society for Clinical and Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV).

2.2. Whole-Exome Sequencing and Data Analysis

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) was conducted using the SureSelect XT HS Low Input Human All Exon V8 kit (Agilent Technologies, Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA). Paired-end sequencing (2 x 150 bp) was performed on the NovaSeq X Plus System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Bioinformatic analysis used the Data Genomics Exome pipeline (v22.4.0) developed by Health in Code (Valencia, Spain). Variant calling and copy number variation (CNV) analysis were conducted using VarSeq (Golden Helix, Inc., Bozeman, MT, USA). Sequence alignment and variant calling were based on the hg19 human genome reference.

A virtual panel of 489 genes associated with IRDs was used to filter variants (Supplementary Data). A minimum read depth of 20 and an allele frequency threshold of 20% were applied. A minor allele frequency threshold of 1 in 500 was applied using gnomAD v2.1.1 [

9]. Missense variants were analyzed using REVEL [

10], while SpliceAI was used for splice variants [

11]. Variants were classified according to the ACMG-AMP guidelines [

12] and the SVI-WG recommendations [

13]. Parental DNA was analyzed to determine whether the variants were inherited in

trans configuration by Sanger sequencing.

Ethical approval was obtained (reference number PR235/24) from the Research Ethics Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital. Informed consent was collected for genetic testing and the publication of clinical data.

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

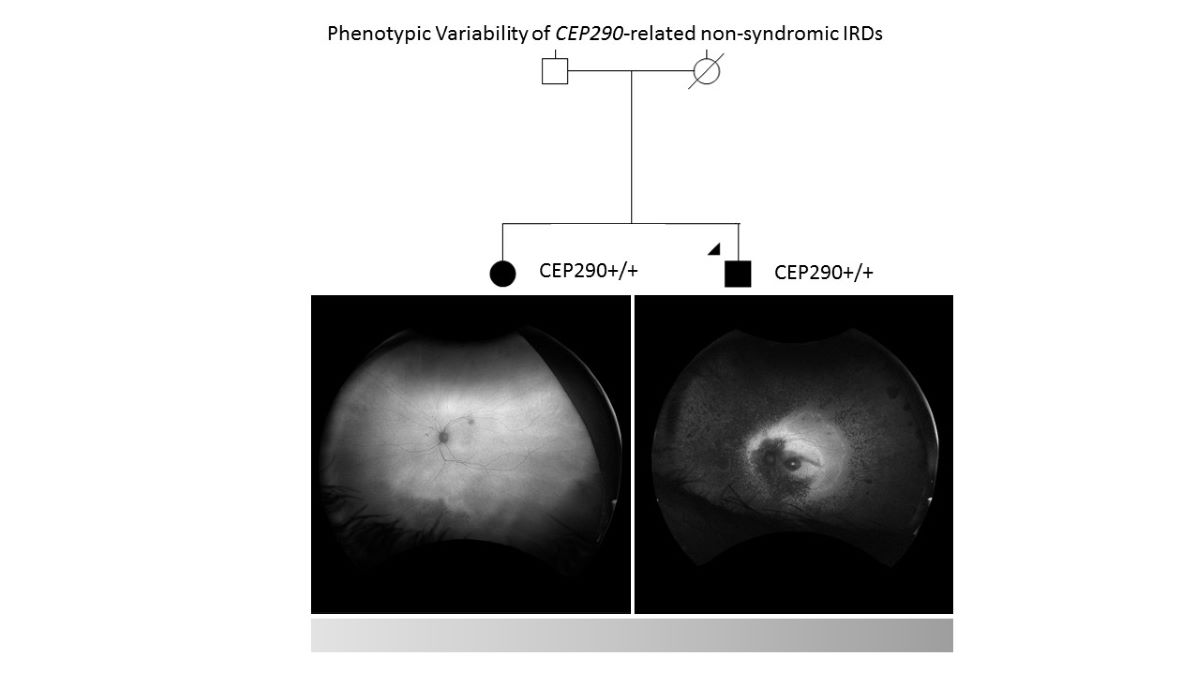

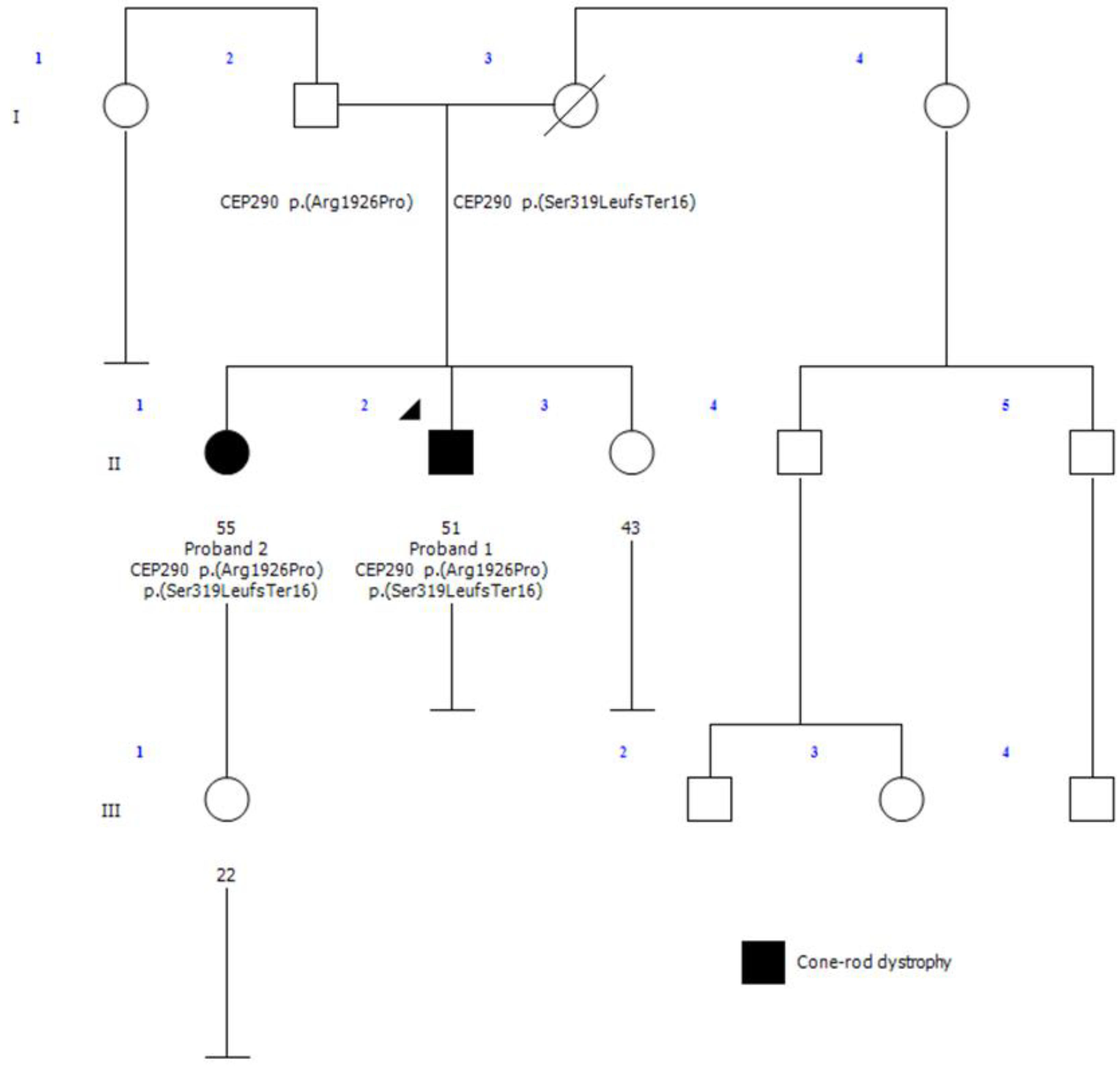

Proband 1 (II-2,

Figure 1) is a 51-year-old male diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa (RP) at age 3, initially presenting with photophobia. Recent symptoms include worsening of night blindness and difficulty adjusting to varying light conditions. At the time of referral (age 50), the ophthalmic examination revealed severe central visual impairment (20/500 OD, 20/640 OS) and peripheral visual field defects. Anterior segment examination showed central subcapsular cataract in both eyes, with intraocular pressure (IOP) of 20 mmHg bilaterally. Fundus examination showed optic disc pallor, 360° pigmentary changes and bone spicules, macular atrophy, and thinned retinal vessels. FAF revealed extensive hypoautofluorescence in the peripheral retina, extending into the superior and inferior nasal quadrants, with a narrow hyperautofluorescent ring around the fovea (

Figure 2A). The OCT confirmed the loss of the outer retinal layers and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE), consistent with macular atrophy (

Figure 2B). Based on these findings, a clinical diagnosis of early onset cone-rod dystrophy was made.

Proband 2 (II-1,

Figure 1), the 53-year-old sister of proband 1, was referred to our clinic at age 51 after a consultation in ophthalmology at a private clinic due to complaints of eye fatigue. She presented milder symptoms, including mild photophobia and peripheral visual field loss, especially in the lower and right lateral areas, but denied experiencing nyctalopia. Upon further inquiry, she recalled childhood difficulties in tracking objects and interpreting visual cues, though she attributed these issues to clumsiness at the time. At presentation, the ophthalmic examination showed moderate visual impairment (20/100 OD, 20/50 OS) with posterior subcapsular cataracts. Fundus examination revealed pigmentary changes and bone spicules in the inferior and temporal peripheral retina of both eyes, although less pronounced than in her brother. Retinal vasculature and optic disc were within normal limits. FAF demonstrated localized hypoautofluorescent patches in the inferior and temporal peripheral retina of both eyes, sparing the posterior pole, with a hyperautofluorescent demarcation line (

Figure 2C). The OCT showed minimal structural abnormalities, with slight fusion and blurring of the outer retinal layers at the subfoveal level, but preservation of the inner retina and a well-defined foveal contour (

Figure 2D). ffERG showed preserved scotopic responses with delayed and reduced photopic cone responses, and abolition of the flicker response. MfERG revealed markedly reduced central amplitudes (

Supplementary Figure S1). These findings suggest a milder form of cone-rod dystrophy.

3.2. Identification of Biallelic Variants in CEP290

WES analysis of proband 1 identified two heterozygous variants in the CEP290 gene: NM_025114.3:c.955del, p.(Ser319LeufsTer16) and NM_025114.3:c.5777G>C, p.(Arg1926Pro). Given the mild clinical presentation observed in proband 2, a diagnosis of CEP290-related IRD was initially ruled out for this individual. Consequently, WES was performed on proband 2 instead of targeted Sanger sequencing of the identified variants as the initial molecular diagnostic approach to explore other potential molecular causes. Unexpectedly, the same two CEP290 variants identified in proband 1 were also present in proband 2, with no additional genetic variants detected. This finding suggests a shared genetic basis for their IRD diagnosis, despite the observed clinical differences.

The variant NM_025114.3:c.955del, located in exon 12/54, results in a nucleotide deletion that is predicted to cause a frameshift, introducing a premature stop codon, p.(Ser319LeufsTer16). This variant is expected to result in a loss-of-function effect due to mRNA degradation via nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), a mechanism previously associated as a mechanism of pathogenicity in this gene (PVS1-very strong). It has a low frequency in gnomAD v2.1.1 population database (0.0006149%) (PM2-supporting), consistent with the recessive inheritance model for

CEP290-related disorders. This variant has been classified as pathogenic in ClinVar (ID:1073010) and HGMD (CD1212112). It has been associated with MKS1 in a homozygous patient [

14] and with LCA10 in a compound heterozygous patient alongside another pathogenic variant (PM3-moderate) [

15]. Additional truncating variants in

CEP290 have been linked to various ciliopathies [

4,

7,

16,

17]. Based on current evidence and ACMG classification guidelines, this variant was classified as pathogenic.

The variant NM_025114.3:c.5777G>C, located in exon 42/54, results in an amino acid substitution p.(Arg1926Pro), changing a positively charged arginine to a neutral proline. It has a low frequency in the gnomAD v2.1.1 population database (0.0004187%) (PM2-supporting), supporting its association with

CEP290-related disorders in a recessive inheritance model.

In silico predictions for this variant are uncertain (REVEL score 0.35), and functional studies have not been conducted. It has been classified as pathogenic in various databases, including HGMD (CM111853), ClinVar (ID: 659046) and LOVD (CEP290_000296). This variant has been reported in individuals with LCA10 in compound heterozygosity with other pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants (PM3-strong) [

5,

18,

19], and it has been shown to segregate in a family with two affected members (PP1-supporting) [

19]. Based on current evidence and following the ACMG classification guidelines, this variant was classified as likely pathogenic.

Parental segregation analysis confirmed that these variants were inherited in trans configuration. Despite both siblings carrying the same biallelic CEP290 variants, their clinical phenotypes differed significantly.

4. Discussion

This study highlights the phenotypic variability associated with biallelic CEP290 variants, demonstrating that even within the same family, individuals can present with dramatically different disease severities. Proband 1 exhibited severe, early-onset retinal dystrophy, consistent with classical CEP290-related IRD phenotypes, while proband 2 displayed a much milder, slowly progressing form of the disease. These findings expand the known clinical spectrum of CEP290-related IRDs, reinforcing the need for personalized clinical management.

Previous studies have primarily associated

CEP290 variants with severe ciliopathies, particularly LCA10, characterized by aggressive retinal degeneration. However, this case study suggests that some patients, despite harboring the same pathogenic variants, may experience milder disease courses. The c.955del variant has consistently been reported alongside loss-of-function alleles. It was observed in a homozygous state in a Pakistani family with MKS1 [

14] and, in another case, in compound heterozygosity with the pathogenic c.4661_4663del variant in a patient with LCA10 [

15], further highlighting its link to severe disease phenotypes. Similarly, the c.5777G>C variant has been frequently reported in combination with other null variants, including the common deep intronic variant c.2991+1655A>G [

18], the c.4966_4967del variant [

19], and the c.1189+2T>C variant [

5] in patients with LCA10. Notably, this study represents, to our knowledge, the first instance of the c.955del variant occurring alongside a missense variant (c.5777G>C), suggesting a potential for a broader phenotypic spectrum, including milder disease presentations, as demonstrated in one of the siblings in our study. This observation raises the possibility that this specific combination of variants could contribute to a less severe clinical course, thus expanding the known phenotypic variability associated with

CEP290-related IRD.

Establishing genotype-phenotype correlations in

CEP290-related conditions has proven challenging due to overlapping phenotypes and substantial clinical variability, even within the same family [

1,

20]. Differences in clinical presentation between siblings in this study may be due to several contributing factors. One possibility is that residual levels of CEP290 protein could explain the milder presentation of the disease in one sibling [

21]. Although the c.955del variant is predicted to undergo NMD, mechanisms such as nonsense-associated altered splicing (NAS) may produce functional transcripts that bypass premature termination codons [

22]. This could lead to some residual expression of the CEP290 protein, which could contribute to a less severe clinical course. Additionally, the presence of other gene variants acting as modifiers could exert protective effects, preserving ciliary function and accounting for the milder phenotype observed in a sibling [

20,

23,

24]. Other cellular mechanisms, those involved in protein quality control and degradation, including endoplasmic reticulum-associated protein degradation (ERAD), have been studied as potential modifiers in the pathogenesis of various diseases, particularly in neurological contexts. Although ERAD’s role in retinal diseases is less established, its involvement in misfolded protein handling suggests that it could contribute to disease progression. Further research is needed to clarify its impact in retinal diseases and explore its potential as a modifier in these conditions [

25,

26].

The lack of clear genotype-phenotype associations in our study further supports the hypothesis that non-genetic factors likely play a role in the observed phenotypic variability. Recent research has highlighted the influence of epigenetic regulation, environmental factors, and allelic heterogeneity on the shaping of disease severity and progression in

CEP290-related IRDs. While the variants identified in this study have not previously been associated with milder IRD phenotypes [

6,

8], it is plausible that epigenetic modifications, environmental exposures (such as oxidative stress or light exposure), or additional, uncharacterized genetic modifiers could explain the discrepancies observed between siblings. Further research is needed to clarify the complex interactions between genetic and non-genetic factors that drive this variability in

CEP290-related IRD.

In our internal cohort of 950 genetically tested individuals with IRD, nine additional individuals were found to carry biallelic pathogenic

CEP290 variants (

Supplementary Table S1). All of them exhibited aggressive early-onset forms of retinal degeneration, with most carrying the common intronic variant c.2991+1655A>G, which has previously been correlated with more severe disease manifestations [

8]. Interestingly, two patients with exonic variants were diagnosed with non-syndromic RP and ACL10, although both exhibited more severe forms of IRD compared to proband 2.

The findings in this report also highlight the importance of genetic counseling in the management of

CEP290-related IRDs, where a broad range of phenotypes must be considered. Genetic testing is increasingly integrated into clinical practice, making personalized management strategies essential. These strategies should involve tailored monitoring and treatment plans, reflecting the diverse clinical presentations of

CEP290-related diseases. Furthermore, emerging gene therapies targeting

CEP290 variants offer promising prospects for treatment, although variability in disease progression requires careful selection of candidates and timing of intervention [

27].

In conclusion, this study broadens the understanding of CEP290-related IRDs and demonstrates the complexity of genotype-phenotype correlations. Future research should focus on identifying genetic and non-genetic factors that contribute to the phenotypic diversity observed in CEP290-related conditions, as well as exploring the potential for personalized therapeutic interventions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: ffERG results for proband 2; Table S1: Biallelic carriers of CEP290 pathogenic variants in our genetically tested IRD cohort.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.E-G. and C.A.; methodology, A.E-G., C.A., J.C-M. and E.C.; validation, A.E-G., C.A., E.C., J.C-M., A.P-M. and C.S.; investigation, A.E-G; writing—original draft preparation, A.E-G.; writing—review and editing, A.E-G., C.A., E.C., J.C-M., A.P-M. and C.S.; supervision, C.A. and E.C.; project administration, A.E-G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study has been supported by Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge (Grant No. PUB22015 to EC).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Bellvitge University Hospital, protocol code PR235/24 on October 25, 2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We want to particularly acknowledge the participating family, Health in Code for performing the sequencing analysis and Biobank HUB-ICO-IDIBELL (PT20/00171) integrated in the ISCIII Biobanks and Biomodels Platform and Xarxa Banc de Tumors de Catalunya (XBTC) for their collaboration.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Coppieters, F.; Lefever, S.; Leroy, B.P.; De Baere, E. CEP290, a Gene with Many Faces: Mutation Overview and Presentation of CEP290base. Hum Mutat 2010, 31, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papon, J.F.; Perrault, I.; Coste, A.; Louis, B.; Gerard, X.; Hanein, S.; Fares-Taie, L.; Gerber, S.; Defoort-Dhellemmes, S.; Vojtek, A.M.; et al. Abnormal Respiratory Cilia in Non-Syndromic Leber Congenital Amaurosis with CEP290 Mutations. J Med Genet 2010, 47, 829–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sahli, E. A Report on Children with CEP290 Mutation, Vision Loss, and Developmental Delay. Beyoglu Eye Journal 2023, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leroy, B.P.; Birch, D.G.; Duncan, J.L.; Lam, B.L.; Koenekoop, R.K.; Porto, F.B.O.; Russell, S.R.; Girach, A. LEBER CONGENITAL AMAUROSIS DUE TO CEP290 MUTATIONS—SEVERE VISION IMPAIRMENT WITH A HIGH UNMET MEDICAL NEED. Retina 2021, 41, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Xie, Y.; Sun, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; Li, Y. Genetic and Clinical Findings in a Chinese Cohort with Leber Congenital Amaurosis and Early Onset Severe Retinal Dystrophy. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2020, 104, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalska, A.; Tracewska, A.M.; Turno-Kręcicka, A.; Szafraniec, M.J.; Misiuk-Hojło, M. A Mild Phenotype Caused by Two Novel Compound Heterozygous Mutations in CEP290. Genes (Basel) 2020, 11, 1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barny, I.; Perrault, I.; Michel, C.; Soussan, M.; Goudin, N.; Rio, M.; Thomas, S.; Attié-Bitach, T.; Hamel, C.; Dollfus, H.; et al. Basal Exon Skipping and Nonsense-Associated Altered Splicing Allows Bypassing Complete CEP290 Loss-of-Function in Individuals with Unusually Mild Retinal Disease. Hum Mol Genet 2018, 27, 2689–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Sodi, A.; Signorini, S.; Di Iorio, V.; Murro, V.; Brunetti-Pierri, R.; Valente, E.M.; Karali, M.; Melillo, P.; Banfi, S.; et al. Spectrum of Disease Severity in Nonsyndromic Patients With Mutations in the CEP290 Gene: A Multicentric Longitudinal Study. Investigative Opthalmology & Visual Science 2021, 62, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karczewski, K.J.; Francioli, L.C.; Tiao, G.; Cummings, B.B.; Alföldi, J.; Wang, Q.; Collins, R.L.; Laricchia, K.M.; Ganna, A.; Birnbaum, D.P.; et al. The Mutational Constraint Spectrum Quantified from Variation in 141,456 Humans. Nature 2020, 581, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannidis, N.M.; Rothstein, J.H.; Pejaver, V.; Middha, S.; McDonnell, S.K.; Baheti, S.; Musolf, A.; Li, Q.; Holzinger, E.; Karyadi, D.; et al. REVEL: An Ensemble Method for Predicting the Pathogenicity of Rare Missense Variants. The American Journal of Human Genetics 2016, 99, 877–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, K.; Kyriazopoulou Panagiotopoulou, S.; McRae, J.F.; Darbandi, S.F.; Knowles, D.; Li, Y.I.; Kosmicki, J.A.; Arbelaez, J.; Cui, W.; Schwartz, G.B.; et al. Predicting Splicing from Primary Sequence with Deep Learning. Cell 2019, 176, 535–548.e24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richards, S.; Aziz, N.; Bale, S.; Bick, D.; Das, S.; Gastier-Foster, J.; Grody, W.W.; Hegde, M.; Lyon, E.; Spector, E.; et al. Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variants: A Joint Consensus Recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genetics in Medicine 2015, 17, 405–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, E.F.; Azzariti, D.R.; Babb, L.; Berg, J.S.; Biesecker, L.G.; Bly, Z.; Buchanan, A.H.; DiStefano, M.T.; Gong, L.; Harrison, S.M.; et al. The Clinical Genome Resource (ClinGen): Advancing Genomic Knowledge through Global Curation. Genetics in Medicine 2024, 101228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanska, K.; Berry, I.; Logan, C. V; Cousins, S.R.; Lindsay, H.; Jafri, H.; Raashid, Y.; Malik-Sharif, S.; Castle, B.; Ahmed, M.; et al. Founder Mutations and Genotype-Phenotype Correlations in Meckel-Gruber Syndrome and Associated Ciliopathies. Cilia 2012, 1, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Areblom, M.; Kjellström, S.; Andréasson, S.; Öhberg, A.; Gränse, L.; Kjellström, U. A Description of the Yield of Genetic Reinvestigation in Patients with Inherited Retinal Dystrophies and Previous Inconclusive Genetic Testing. Genes (Basel) 2023, 14, 1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppieters, F.; Lefever, S.; Leroy, B.P.; De Baere, E. CEP290, a Gene with Many Faces: Mutation Overview and Presentation of CEP290base. Hum Mutat 2010, 31, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xiao, X.; Li, S.; Jia, X.; Xin, W.; Wang, P.; Sun, W.; Huang, L.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q. Molecular Genetics of Leber Congenital Amaurosis in Chinese: New Data from 66 Probands and Mutation Overview of 159 Probands. Exp Eye Res 2016, 149, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiszniewski, W.; Lewis, R.A.; Stockton, D.W.; Peng, J.; Mardon, G.; Chen, R.; Lupski, J.R. Potential Involvement of More than One Locus in Trait Manifestation for Individuals with Leber Congenital Amaurosis. Hum Genet 2011, 129, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheck, L.; Davies, W.I.L.; Moradi, P.; Robson, A.G.; Kumaran, N.; Liasis, A.C.; Webster, A.R.; Moore, A.T.; Michaelides, M. Leber Congenital Amaurosis Associated with Mutations in CEP290, Clinical Phenotype, and Natural History in Preparation for Trials of Novel Therapies. Ophthalmology 2018, 125, 894–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perea-Romero, I.; Gordo, G.; Iancu, I.F.; Del Pozo-Valero, M.; Almoguera, B.; Blanco-Kelly, F.; Carreño, E.; Jimenez-Rolando, B.; Lopez-Rodriguez, R.; Lorda-Sanchez, I.; et al. Genetic Landscape of 6089 Inherited Retinal Dystrophies Affected Cases in Spain and Their Therapeutic and Extended Epidemiological Implications. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minella, A.L.; Narfström Wiechel, K.; Petersen-Jones, S.M. Alternative Splicing in CEP290 Mutant Cats Results in a Milder Phenotype than LCA CEP290 Patients. Vet Ophthalmol 2023, 26, 4–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.-M.; Ashi, M.O.; Srour, N.; Delpy, L.; Saulière, J. Mechanisms and Regulation of Nonsense-Mediated MRNA Decay and Nonsense-Associated Altered Splicing in Lymphocytes. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Datta, S.; Brabbit, E.; Love, Z.; Woytowicz, V.; Flattery, K.; Capri, J.; Yao, K.; Wu, S.; Imboden, M.; et al. Nr2e3 Is a Genetic Modifier That Rescues Retinal Degeneration and Promotes Homeostasis in Multiple Models of Retinitis Pigmentosa. Gene Ther 2021, 28, 223–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, K.J.; Anderson, M.G. Genetic Modifiers as Relevant Biological Variables of Eye Disorders. Hum Mol Genet 2017, 26, R58–R67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.X.; Wang, J.J.; Starr, C.R.; Lee, E.-J.; Park, K.S.; Zhylkibayev, A.; Medina, A.; Lin, J.H.; Gorbatyuk, M. The Endoplasmic Reticulum: Homeostasis and Crosstalk in Retinal Health and Disease. Prog Retin Eye Res 2024, 98, 101231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.-C.; Kroeger, H.; Sakami, S.; Messah, C.; Yasumura, D.; Matthes, M.T.; Coppinger, J.A.; Palczewski, K.; LaVail, M.M.; Lin, J.H. Robust Endoplasmic Reticulum-Associated Degradation of Rhodopsin Precedes Retinal Degeneration. Mol Neurobiol 2015, 52, 679–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, E.A.; Aleman, T.S.; Jayasundera, K.T.; Ashimatey, B.S.; Kim, K.; Rashid, A.; Jaskolka, M.C.; Myers, R.L.; Lam, B.L.; Bailey, S.T.; et al. Gene Editing for CEP290-Associated Retinal Degeneration. New England Journal of Medicine 2024, 390, 1972–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).