3.1. Generating Artificial Time Series

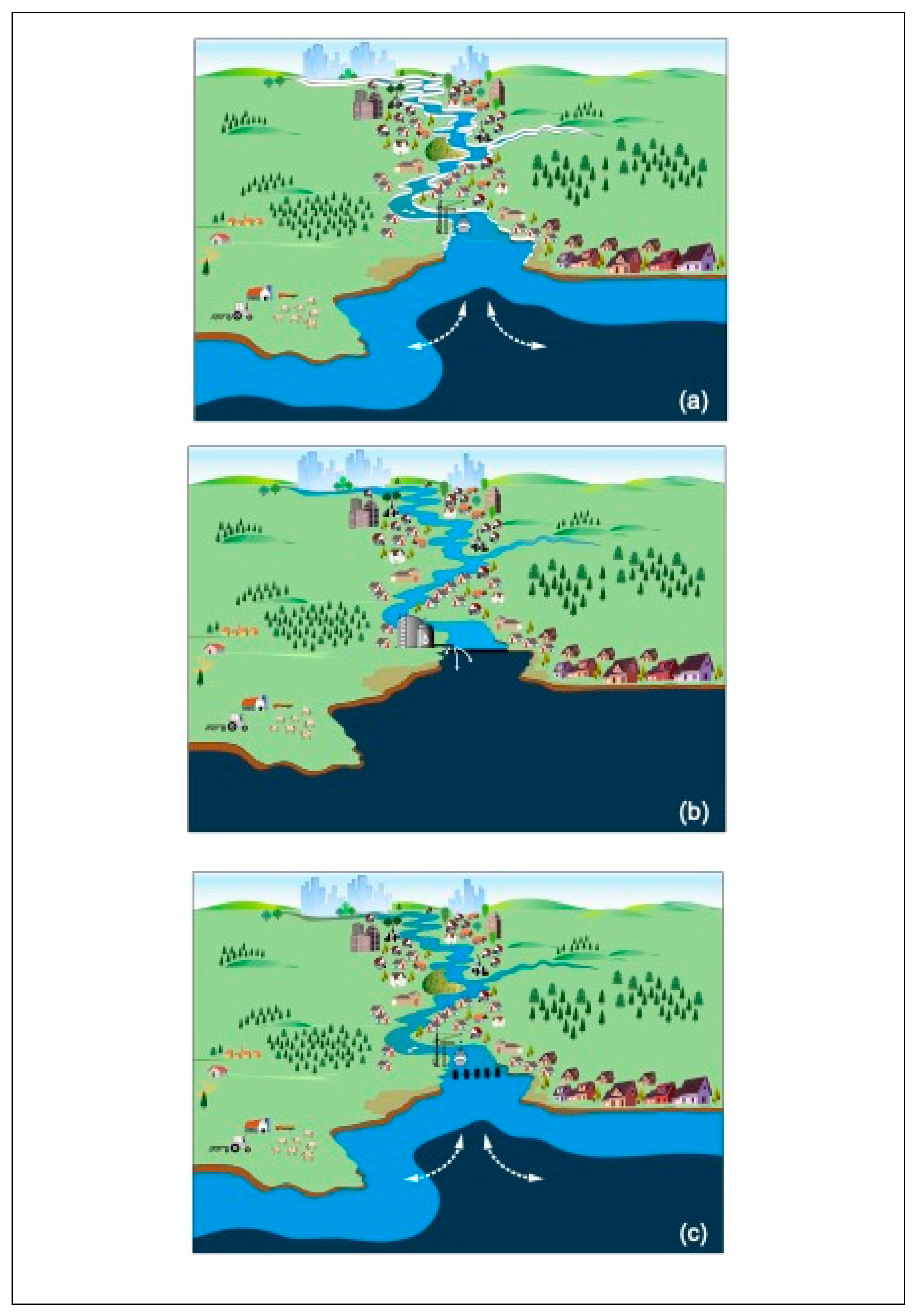

In the first stage, we generate artificial time series of total water level, with realistic characteristics that match observations, at the two tide gauge sites on which barrier closure decisions are respectively made, namely: Roompot Buiten for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier; and Southend-on-Sea for the Thames Barrier. We use different statistical methods, with parameters fitted to measured historical datasets, to create time series of the three components of still water level (i.e., astronomical tides, storm surges and relative mean sea level) separately, ensuring we accurately reproduce observed temporal variability (e.g., seasonality) and auto-correlation, in each component. We superimpose these time series with climate change projections to generate future time series for different scenarios. Then we combine them to generate records of total water level. We use a Monte Carlo approach to represent intra- and inter-annual variability and therefore to account for uncertainty. Closure decisions for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier are based purely on forecast high water levels at the barrier exceeding 3 m NAP (

Supplementary Figure S1a), and so the water level time series at Roompot Buiten are all we need to predict likely closure statistics. However, for the Thames Barrier (as discussed in

Section 2.2), decisions to closure the barrier are guided by a matrix, based on both forecast still water levels at Southend-on-Sea and forecast river discharge at Teddington Weir (

Supplementary Figure S1b). Hence, we also generate future artificial time series of river discharge at Teddington Weir. The approach we use to generate total water levels is described in

Section 3.1.1 and river flow in

Section 3.1.2.

3.1.1. Water Levels

Extreme still water levels arise as combinations of: (1) astronomical tides; (2) storm surges; and (3) relative mean sea level (Pugh and Woodworth, 2014). These three components exhibit considerable natural intra- and inter-annual variability. While the tidal component is deterministic, with predictable modulations on fortnightly, monthly, seasonal, 4.4-year and 18.6-year timescales (Haigh et al., 2011), the variability in the storm surges and mean sea-level components is stochastic, with intra-annual (e.g., seasonal) signals and inter-annual variability linked to regional climate cycles (such as the North Atlantic Oscillation; Hurrell, 1995). It is important that our approach realistically reproduces both the temporal variability at different timescales and auto-correlation observed in each of the components, at our two tide gauge sites. Below we describe how we generate artificial time series for each of the three components separately, before combining them to create records of total still water level.

Astronomical tide: First, we generate time series of astronomical tides, at each of the two tide gauge sites, by undertaking a harmonic tidal analysis (on the available measured 10-minute water level data) and prediction, using the U-Tide software tool (Codiga, 2024). For past years, a separate tidal analysis was undertaken for each calendar year, using the standard tidal constituents, to predict the tide for that given year. For years with less than 6 months of data coverage, the tidal component was predicted using harmonic constituents estimated for the nearest year with sufficient data. For the future period, we first undertook a harmonic analysis of the data from the most recent 5 years (2019-2023) and used the standard 68 tidal constituents returned by U-Tide, to predict the tide for all future years from 2024 onwards. Hence, we generate time series of predicted tide (at 10-minute intervals) from the date of the first barrier closure, until a chosen year in the future. Note, when predicting the tides we set the amplitude of the seasonal (SA) and semi-seasonal (SAA) tidal constituents to zero. This is because these are largely driven by non-astronomical processes and these seasonal variations in sea level are represented later in the mean sea-level component, described below.

We predict the tides until the end of 2150. Our tidal predictions accurately capture the variations on daily, fortnightly, monthly, seasonal, 4.4-year and 18.6-year timescales, at each site. As tides are deterministic, we only need a single time series of tidal values at each of the two tide gauge sites. To determine closure statistics, we just need times and heights of predicted high waters (not the full tidal curve), as it is the height of the forecast high water that closure decisions are made on. Therefore, we extract time series of ~twice-daily tidal high waters, using a peaks algorithm (and check that the correct number, between 705 to 708 high waters, are selected each year). Time series of past and future ~twice-daily high tidal levels at Roompot Buiten (Eastern Scheldt Barrier) and Southend-on-Sea (Thames Barrier) are shown in

Supplementary Figures S3a and S4a, respectively.

For future scenarios (see

Section 4), we start by just considering SLR and assume that tidal characteristics do not change in the future. For these storylines we use the tidal constituents obtained from the harmonic analysis of the 5 most recent years of data, to predict tides into the future (as described above), assuming tidal characteristics remain the same as today. However, an increasing number of studies have observed that tidal levels in many locations have changed and are likely to vary into the future due to non-astronomical factors over seasonal, decadal, and secular time scales (see Haigh et al., 2020a for a detailed review of the topic). Increases in tidal range have been observed at several sites around the southern North Sea, including along the coast of the Netherlands and in the Thames Estuary over the last ~100 years (Jänicke et al., 2000; Haigh et al., 2020a). Therefore, we run additional storylines (see

Section 4) in which we account for possible future increases in tidal range, that have been predicted (e.g., Pickering et al., 2017). We do this in a relatively simple way. We use the tidal constituents obtained from the harmonic analysis of the 5 most recent years of data, to predict tides into the future, but each year we increase the M

2 tidal constituent by a selected amount (i.e., 1, 2, or 3 mm/yr). We only change the M

2 tidal constituent, and no other constituents, because at both tide gauge sites considered here, this constituent is the dominant constituent, as these regions are strongly semi-diurnal.

Skew surges: Second, we generate realistic time series of skew surges, at each of the two tide gauge sites, using an advanced statistical approach, fitted to the historic dataset. Note, we deliberately chose to generate time series of ~twice-daily skew surges and not (10 minute) non-tidal residuals, for two key reasons. Firstly, the non-tidal residual primarily contains the meteorological contribution termed the ‘storm surge’ but may also contain harmonic prediction errors or timing errors, and importantly, non-linear interactions. Non-linear interactions between the tide and storm surge components are particularly large in the southern North Sea (e.g., Horsburgh and Wilson, 2007; Arns et al., 2020). They are complex and vary considerably spatially and are not easily represented in a statistical model. Secondly, as discussed above, closure decisions are only based on heights of high waters, and not the full tidal curve, and so only information at the time of high water is needed. A skew surge is the difference between the maximum observed sea level and the maximum predicted tidal level regardless of their timing during the tidal cycle, and hence each tidal cycle has one high water value and one associated skew surge value. The advantages of using skew surge, instead of non-tidal residual, are that it is: (1) a simple and unambiguous measure of the storm surge relevant to any predicted high water; (2) operationally it defines the quantity relevant to barrier closure decisions; and (3) as Williams et al. (2016) demonstrated, there is negligible dependence between astronomical tide and skew surge, which simplifies our approach, as we can treat the tide and skew surge time series independently (if we generated time series of non-tidal residual, we would have to build an advanced approach to account for non-linear dependence between tide and the non-tidal residual).

Skew surges exhibit strong seasonality, as they are driven meteorologically, and temporal dependence since storm events span multiple tidal cycles. We develop an advanced statistical approach for simulating realistic skew surge time series; this is the first approach, to the best of our knowledge, for simulating realistic skew surge time series that reflect both the seasonality and temporal dependence exhibited in the observed data. To generate time series of skew surges for both past and future years we build on the methodology of D’Arcy et al. (2023), who derived a model for sea levels that uses skew surge and peak tide as two components of sea levels in a joint probabilities framework. They split the distribution of skew surges into extreme and non-extreme values using a peaks-over-threshold framework (Coles, 2001). They use a monthly threshold

uj for

j = 1, . . . , 12 to account for seasonality, with

uj being a quantile, for a fixed percentile, of month

j’s skew surge distribution. Using a percentile-based threshold ensures a similar number of exceedances each month. Skew surges below these thresholds are modelled using the monthly empirical distribution to capture within-year non-stationarity of non-extreme values. When tide gauge records have long observational periods, this non-parametric approach can reliably model the main body of the data. For exceedances of the monthly thresholds, they use a generalised Pareto distribution (GPD), which is a well-established model for modelling threshold exceedances (Coles, 2001). This distribution is characterised by three parameters

σ > 0, ξ and

λ ∈ [0, 1], the scale, shape and rate parameter, respectively. To capture seasonality, they allow the scale

σ and rate

λ parameter to be dependent on day in year

d = 1, . . . , 365 and month

j, parameterised by harmonics. For example, for the scale parameter,

for

α > β > 0, φ ∈ [0, 365) parameters to be estimated and

f = 365 the periodicity. The shape parameter ξ does not vary with any covariate to avoid introducing additional uncertainty typically associated with estimating this parameter.

D’Arcy et al. (2023) account for temporal dependence using the extremal index (Ferro and Segers, 2003). However, this makes simulation difficult and only captures dependence in extreme values. Therefore, here we develop and apply a new approach for accounting for temporal dependence in skew surges. To do so, we use a copula to model dependence of values separated by lag k, assuming the process follows a kth order Markov process. We now describe how we choose the copula model and the value of k to capture temporal dependence. We denote our observed skew surge series as X1, . . . , Xn for n the total number of observations at a specific location. Copulas describe the association between observations separated by some lag k in a series and take different forms; they are commonly used in statistics and extreme value analysis (Nelsen, 2006). We test two different copula models (Gaussian and bivariate logistic extreme value distribution) to contrast the extremal dependence structures (asymptotic independence and asymptotic dependence; Coles et al., 1999). When there is a non-zero probability of Xt+k being large given Xt is large (i.e., exceeding some extreme levels), we say that the series exhibits asymptotic dependence. The Gaussian copula gives a better fit, which agrees with our exploratory findings of asymptotic independence, so there is zero probability of Xt+k being large given Xt is large is zero. This copula is parametrised by a dependence parameter ρ ∈ [0, 1]. We then assume the series follows a kth order Markov process; this is a stochastic process where the distribution a time t is dependent on the distribution at times t − 1, . . . , t − k. The value of k is chosen carefully, by fitting copula models for various values and selecting k based on Akaike and Bayesian information criteria (AIC and BIC, respectively); these are common tools for statistical model selection. We perform this selection at both sites independently, as the storm behaviour can differ. However, we find k = 5 for both sites, corresponding to ~2.5 days. This reflects the known average duration of storm events that typically impact the region (Haigh et al. 2016). Therefore, our model for temporal dependence is characterised by 5 parameters, ρτ ∈ [0, 1] for τ = 1, . . . , 5 representing the strength of dependence for values separated by τ values.

As skew surge records are stochastic, with considerable variability each year, rather than generating a single time series for each of our two tide gauge sites, like for astronomical tides, we generate multiple time series for each site. For Roompot Buiten (Eastern Scheldt Barrier) we generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily skew surge values, at time of high tide, from 1986 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S3b. For Southend-on-Sea (Thames Barrier) we also generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily skew surge values from 1982 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S4b. To demonstrate that our framework generates time series with realistic characteristics that match observations, we compare observed and simulated skew surge datasets for both sites in

Supplementary Figure S5. Monthly boxplots of the observed and simulated skew surges are shown in

Supplementary Figure S6. Both figures demonstrate that the model does an excellent job of reproducing the observed characteristics, and has the advantage that larger, but still physically plausible skew surges values, are predicted than has been observed in the past.

For future scenarios (see

Section 4), we start by just considering SLR and assume that skew surge characteristics do not change in the future. However, we also run additional storylines in which we account for possible future increases in extreme skew surges. To do this we add a year covariate via a linear term to the parametrisation of the scale parameter, assuming mean skew surges change linearly across years. The GPD scale parameter approximates the mean of extreme skew surges, so it makes sense to incorporate long-term increases in storminess through this parameter, although one could also represent changes in the frequency of extreme skew surge events via the rate parameter λ (see D’Arcy et al., 2023). Our updated parameterisation is denoted

where

is the parameterisation previously defined,

y represents the year of interest and

is the increase in mean skew surges per year (in metres). For simulation purposes, we specify the value of

to create possible future increases in storminess representative of 100%, 200% and 300% changes in skew surges by 2150.

Mean sea level: Third, we generate realistic monthly time series of mean sea level, at each of the two tide gauge sites, and interpolate these to ~twice-daily times of high water. Monthly time series of mean sea level exhibit seasonality, year-to-year variability and a longer-term trend associated with climate change; we aim to capture these variations in our simulations to reflect the realism of the mean sea level component. First, at both Roompot Buiten (Eastern Scheldt Barrier) and Southend-on-Sea (Thames Barrier) tide gauges we compute monthly mean time series of sea level from the observations. We firstly detrend the data-using a quadratic trend to remove long-term trends. Then, we use harmonic analysis to capture the 6-monthly and annual cycles present in the mean sea level. We subtract the fitted seasonal cycle, obtained from the harmonics, from the detrended monthly record, leaving us with a residual time series. We find that it is reasonable to assume this residual time series is independent, and follows a normal distribution, at both sites. Hence, to simulate a realistic mean sea level series, we sample from a normal distribution (with parameters inferred from the fit to the observed data) and add back on the fitted 6-monthly and annual harmonics. This yields a stationary sequence that mean sea-level projections can be added onto.

In the scenarios we run (see

Section 4), we use actual annual mean sea level values for the past period at each of the two sites (i.e., 1986 to 2023 at Roompot Buiten and 1982 to 2023 at Southend-on-Sea), calculated from the observations, to capture the observed rise in mean sea level. For the future period we use annual mean sea-level rise projections from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (SAR; Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). We offset the projections so that they start from zero in the year 2023. Thus, the simulated time series of mean sea level have; (1) a fitted seasonal cycle; (2) random monthly noise from a normal distribution fitted to the observed data; and (3) annual past mean sea level changes up to 2023 and future projected changes after 2023. Note, for the period 2024 onwards, we use the average mean sea level over the last 5 years (2019 to 2023) as a baseline, upon which we add the annual projections. We use an average of 5 years, rather than one year (i.e., 2023) to represent the future baseline, as annual mean sea level can vary considerably from year to year. Finally, these monthly time series are interpolated to the ~twice-daily high tidal date and times, so they can be combined with the astronomical tide and skew surge time series. For Roompot Buiten (Eastern Scheldt Barrier) we generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily mean sea level values, at time of high tide, from 1986 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S3c, with a high emission SLR scenario (see

Section 4). For Southend-on-Sea (Thames Barrier) we generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily mean sea level values from 1982 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S4c, with a high emission SLR scenario.

Total water level: To generate simulated total water level records, we simply combine the single astronomical high tide time series at each site, with one of the 500 skew surge and 500 mean sea level time series. For Roompot Buiten (Eastern Scheldt) we therefore generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily total high water level values, at time of high tide, from 1986 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S3d, with a high emission SLR scenario. For Southend-on-Sea (Thames Barrier) we generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily total high water values from 1982 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S4d, with a high emission SLR scenario.

3.1.2. River Discharge

Closure decisions at the Eastern Scheldt Barrier, are based purely on forecast high water levels (

Supplementary Figure S1a), so no time series of river discharge are needed. However, decisions to close the Thames Barrier are based on both forecast still water levels at Southend-on-Sea and forecast river flow at Teddington Weir (Figure Supplementary S1b). Hence, we also generate artificial but realistic future time series of river discharge at Teddington Weir. The daily variation in river discharge over individual storm events, seasons and the longer term is very different to skew surges. For example, auto-correlation operates over much longer periods (days to weeks), and the changes in river discharge over individual storm events are much more asymmetrical, typically with a rapid rise in river discharge followed by a much more gradual decrease, due to the various river catchments draining into the Thames River. This therefore requires a more sophisticated statistical method, than the one we used for skew surges, which is described above. We are in the process of developing an advanced statistical method to capture this variability (see D’Arcy and Tawn, 2024). However, for the purpose of this paper, we took a much simpler approach and just resampled the past dataset. For each future year (note again, a year goes from July to June of the subsequent year to capture a complete winter period), a year from the past between 1883/84 and 2022/23 is chosen to represent that given future year. River discharges are available at daily frequency, and so we use the same value ~twice each day, to correspond with times of ~twice-daily high waters. For Teddington Weir (Thames) we therefore generate 500 time series of ~twice-daily river discharge values, at time of high tide, from 1986 to 2150, and an example of a single select record is shown in

Supplementary Figure S4e. Note, we assumed independence between the skew surge and river discharge time series. For the UK east coast, including the Thames region, Hendry et al. (2019) showed that there is negligible dependence between storm surges and river discharge, as the storms that typically generate high skew surges are distinct from the types of storms that tend to generate high river discharge.

For future scenarios (see

Section 4), we start by just considering SLR and assume that river discharge characteristics do not change in the future. However, it is likely that future changes in rainfall patterns will influence river discharge in the Thames Estuary and at Teddington Weir (Murphy et al., 2018). Therefore, we run additional storylines (see

Section 4) in which we increase the river discharge by different temporally varying percentage changes based on projections from the Environment Agency for the region (Environment Agency, 2022).

3.4. Future Scenarios

Having demonstrated that the tool accurately predicts past closure statistics, we now use the tool to estimate potential future numbers of closures considering different projections of SLR, changes in storm surges, tides and river discharge, and varying water level forecast errors (Objective 2).

First, we consider just relative changes in SLR, assuming that skew surges, tides and in the case of the Thames Barrier, river discharge, remain unchanged from past/present conditions. We consider 4 SLR scenarios from the IPCC AR6 (Fox-Kemper et al., 2021):

The 83rd percentile of projection SSP1-1.99, which equates to a low emission scenario;

The 83rd percentile of projection SSP2-4.5, which equates to a medium emission scenario;

The 83rd percentile of projection SSP5-8.5, which equates to a high emission scenario; and

The 95th percentile of the low confidence projection SSP5-8.5, which equates to a high-end (e.g., low-likelihood but high impact) scenario.

We downloaded the local SLR projections for the locations nearest to the Roompot Buiten and Southend-on-Sea tide gauges from the NASA Sea Level Project Tool webpage (

https://sealevel.nasa.gov/ipcc-ar6-sea-level-projection-tool). The projections include vertical land movements and are listed in

Table 1 for both sites. They are available every decade from 2020 to 2150, relative to a 1995-2014 baseline. We offset each of the 4 chosen projections, so they are zero in 2023 and then interpolate these to the ~twice-daily high-water time series. For the simulations, for both the Eastern Scheldt and Thames Barriers, we assume a rounded water level forecast error of 0.2 m (close to the 0.19 m that gave the best agreement at the Thames Barrier with observed closures;

Section 3.3) for consistency and to make it easier to compare statistics between the two study barriers (even though this is larger than the 0.11 m forecast error which gave the best comparison with observed closures at the Eastern Scheldt Barrier;

Section 3.3).

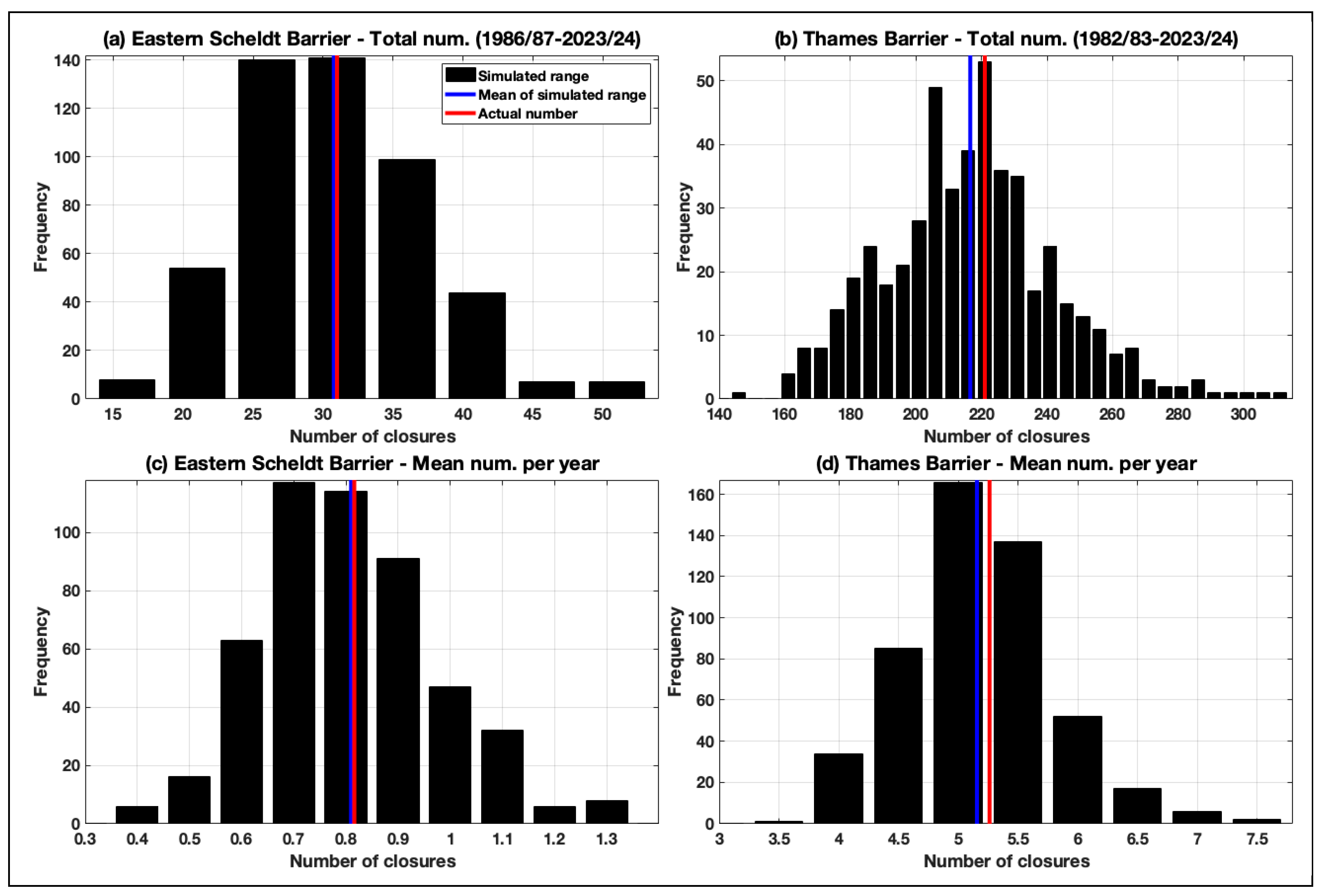

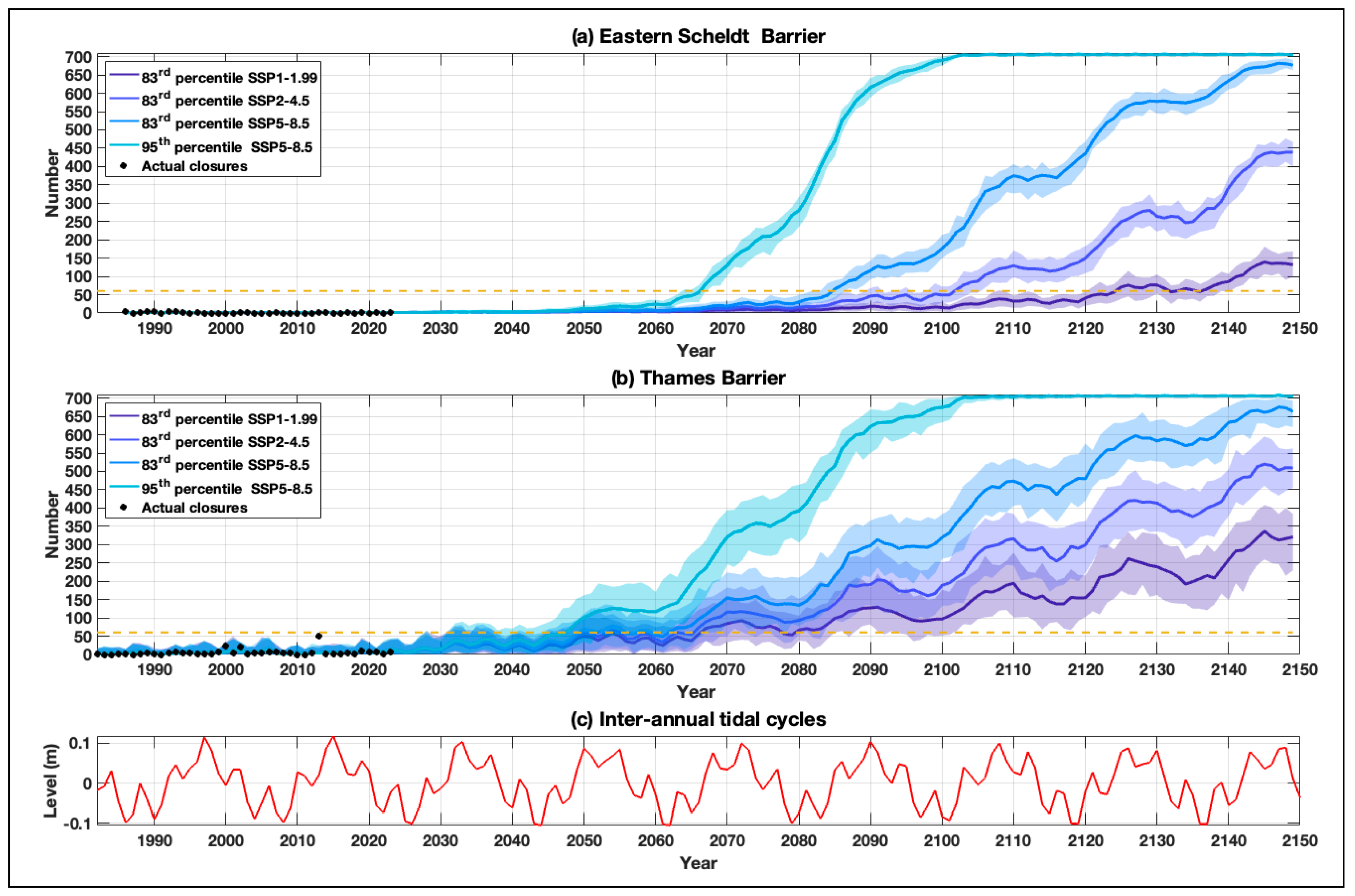

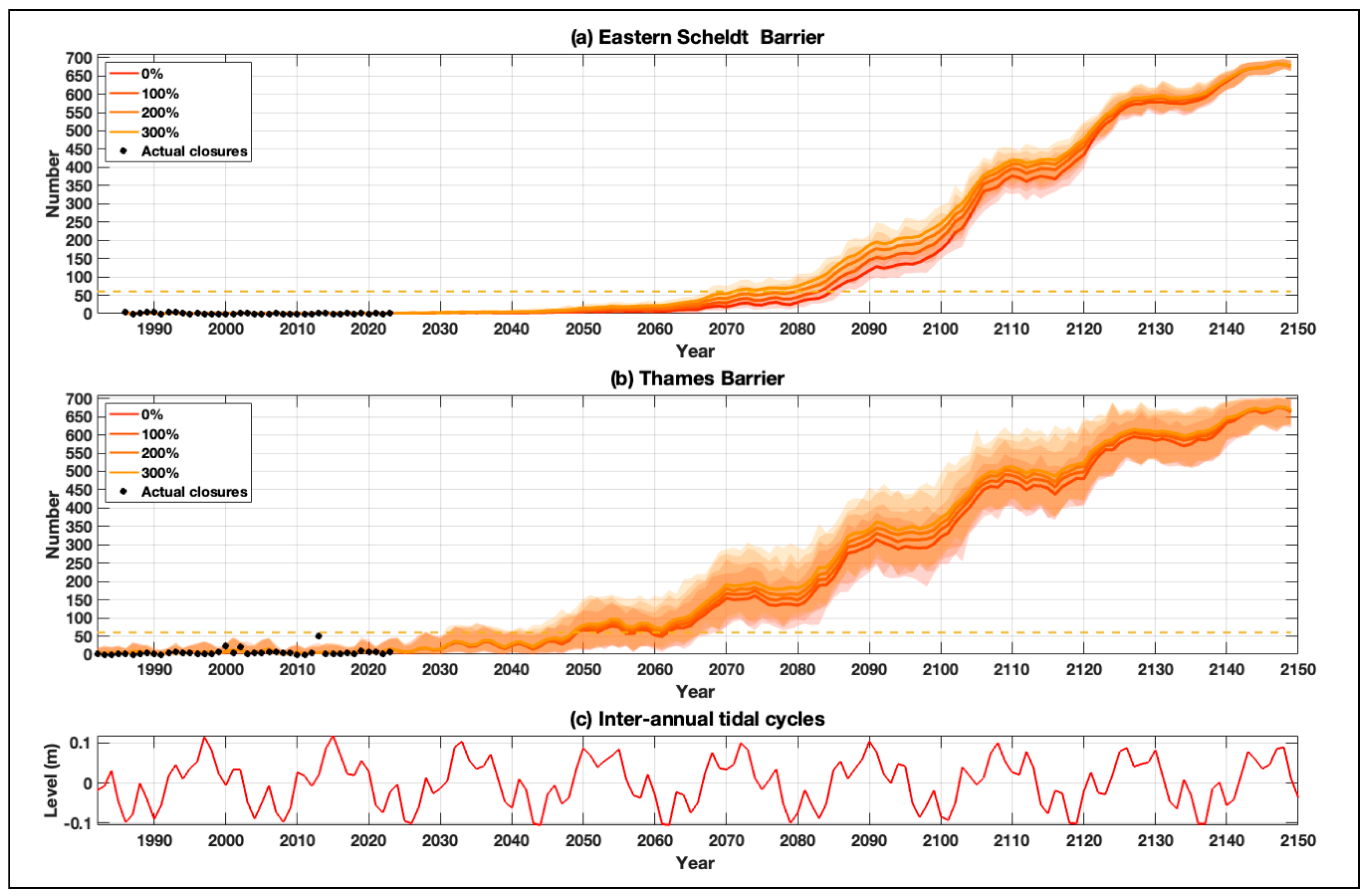

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) of the estimated number of barrier closures, across each of the 500 simulated time series and for each year from 1986/87 to 2149/50, is shown in

Figure 4a for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier, for each of the 4 SLR projections considered. The actual number of closures each year that occurred between 1986/87 to 2023/24 are overlaid, as black dots. The average number of closures each year, averaged over each decade from 1990-2000 to 2140-2150, are listed in

Table 2. As expected, the number of closures rapidly increases in the future, with SLR. For the high-end SLR scenario (95

th percentile of projection SSP5-8.5), the tool indicates that the barrier would close for every single high water just after 2100. For each of the 4 SLR projections, the number of closures of the Eastern Scheldt increases from an average of 1.1, 1.1, 1.1 and 1.1 times per year in 1990-2000, to 2.5, 2.7, 3.1 and 5.3 in 2040-50, to 16, 44, 135 and 654 in 2090-2100, to 122, 411, 667 and 706 times per year in 2140-2150, respectively.

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) in number of closures each year from 1982/83 to 2149/50 is shown in

Figure 4b for the Thames Barrier. The average number of closures each year, averaged over each decade, are listed in

Table 2. There is a more rapid increase in the number of closures for the Thames Barrier compared to the Eastern Scheldt Barrier, and a much greater spread across the 500 simulations. This is expected given that the Thames Barrier currently closes around 5 times more frequently each year than the Eastern Scheldt. For each of the 4 SLR projections, the number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases from an average of 4.0, 3.9, 4.0 and 4.0 times per year in 1990-2000, to 24, 26, 31 and 49 in 2040-50, to 108, 180, 298 and 646 in 2090-2100, to 305, 496, 659 and 706 times per year in 2140-2150, for the 4 SLR scenarios considered, respectively. The tidal variation of the 4.4-year perigean and 18.6-year nodal cycle at Southend-on-Sea is shown in

Figure 4c (note, the phase is the same at Roompot Buiten, but the magnitude slightly less). Interestingly, as SLR increases over time, the number of closures is more strongly influenced by the 18.6-year nodal cycle, for both the Eastern Scheldt (

Figure 4a) and Thames (

Figure 4b) Barriers. The number of closures is also influenced by the quasi 4.4-year perigean cycle, but to a lesser extent.

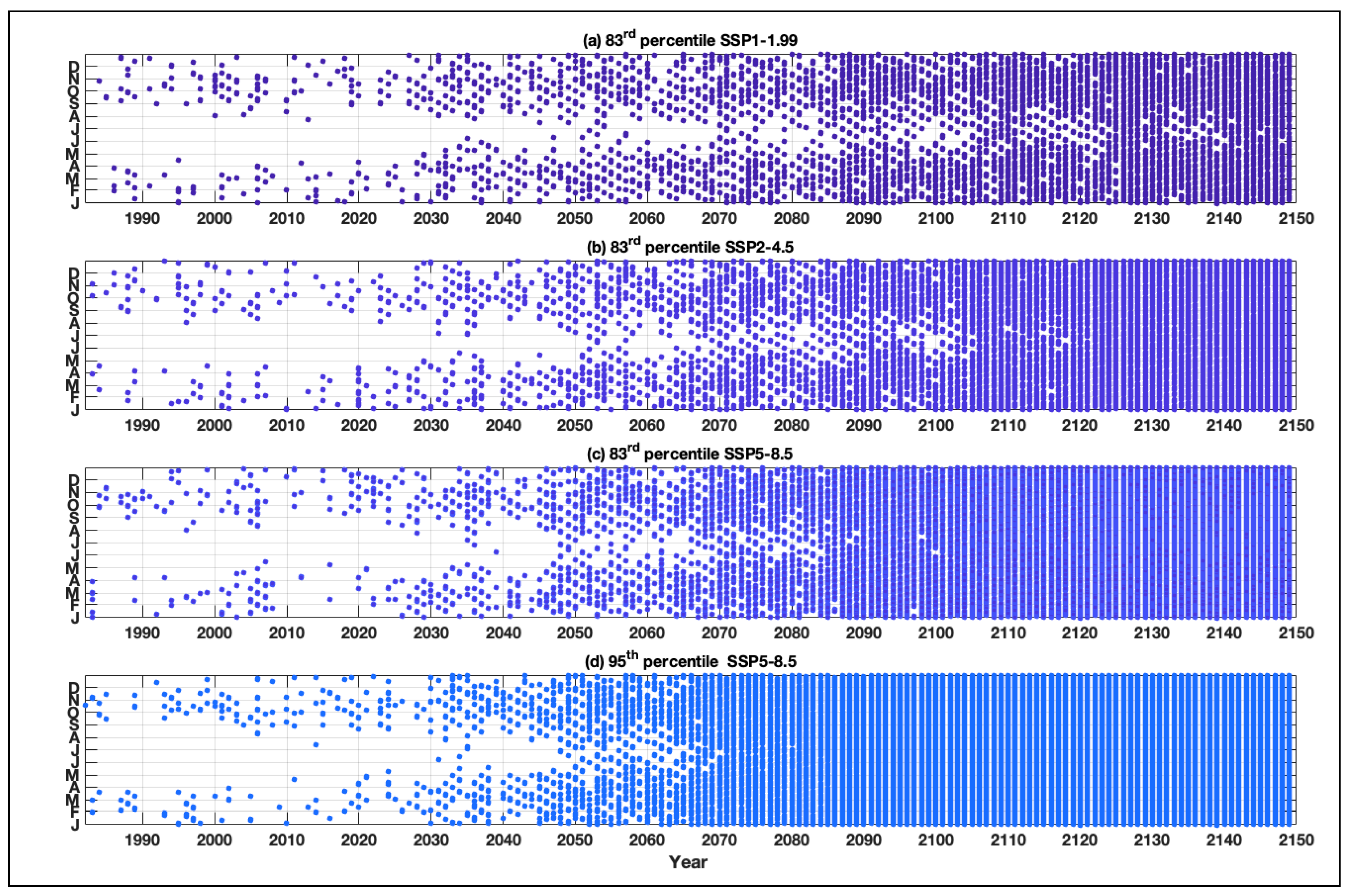

The tool not only captures the number of closures each year, but the date and time when each closure occurs, across the 500 simulations, and so we are also able to examine changes in closure statistics throughout the year. As an example, we show in

Figure 5, the dates when closures occurred for the Thames Barrier, for 1 of the 500 simulations, for each of the 4 different SLR projections considered. In these plots each year is on the

x-axis and the

y-axis shows dates through the year, from January to December. Currently closures typically occur between September and April, for the Thames Barrier (see also

Supplementary Figure S2d). However, with future SLR, closures will begin to increasingly occur over the summer months. Closures will start to occur year-round (i.e., every month) from around 2090 in the low-emission scenario, 2070 in the medium-emission scenario, 2050 high-emission scenario and 2050 in the high-end scenario. Again, the plots in

Figure 5 show the influence of the 18.6-year nodal cycle, in terms of times of year when closures typically occur.

Second, we consider changes in skew surges. There is little evidence for long-term systematic changes in storminess or storm surge magnitude over the last 100 years above natural variability in the North Sea and around the world (Marcos et al., 2015; Mawdsley and Haigh, 2016; Haigh et al., 2022), although a recent paper challenges this view (Calafat et al., 2022). Moreover, there remains low confidence in future projections of changes in extra-tropical storms or storm surges in the North Sea and globally (Palmer et al., 2018; Fox-Kemper et al., 2021). However, to illustrate that the tool can account for changes in skew surge, and as a sensitivity test, we ran simulations in which we increased the magnitude of the skew surges in time corresponding to 0%, 100%, 200% and 300% increases by 2150. We ran these simulations with the high emission SLR scenario (83rd percentile of projection SSP5-8.5) and a water level forecast error of 0.2 m for both barriers.

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) in the number of closures each year, for the scenarios in which we have increased skew surge magnitude, is shown in

Figure 6a for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier and

Figure 6b for the Thames Barrier. The average number of closures each year for the skew surge change scenarios, averaged over each decade, are listed in

Table 3. The increases in closures driven by changes in skew surges, are significantly smaller than those driven by SLR. Never-the-less, increases in skew surge magnitude, as expected, drive an increase in closures. Again, as expected the spread of results is larger for the Thames Barrier than for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier. For each of the 4 scenarios considered (i.e., 0, 100%, 200% and 300%), with the high emission SLR scenario, the number of closures of the Eastern Scheldt Barrier increases from an average of 1.1, 1.1, 1.1 and 1.1 times per year in 1990-2000, to 3.1, 4.4, 5.8 and 7.5 in 2040-50, to 135, 163, 187 and 205 in 2090-2100, to 667, 669, 669 and 669 times per year in 2140-2150, respectively. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2090-2100 with 28, 51 and 70 extra closures per year for the corresponding 100%, 200% and 300% increases, compared to no increase in skew surges. The number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases from an average of 4.0, 4.0, 3.9 and 4.0 times per year in 1990-2000, to 31, 34, 37 and 39 in 2040-50, to 298, 318, 335 and 349 in 2090-2100, to 659, 663, 664 and 666 times per year in 2140-2150, for the 4 skew surge scenarios considered, respectively. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2090-2100 with 19, 37 and 51 extra closures per year for the corresponding 100%, 200% and 300% increases, compared to no increase in skew surges.

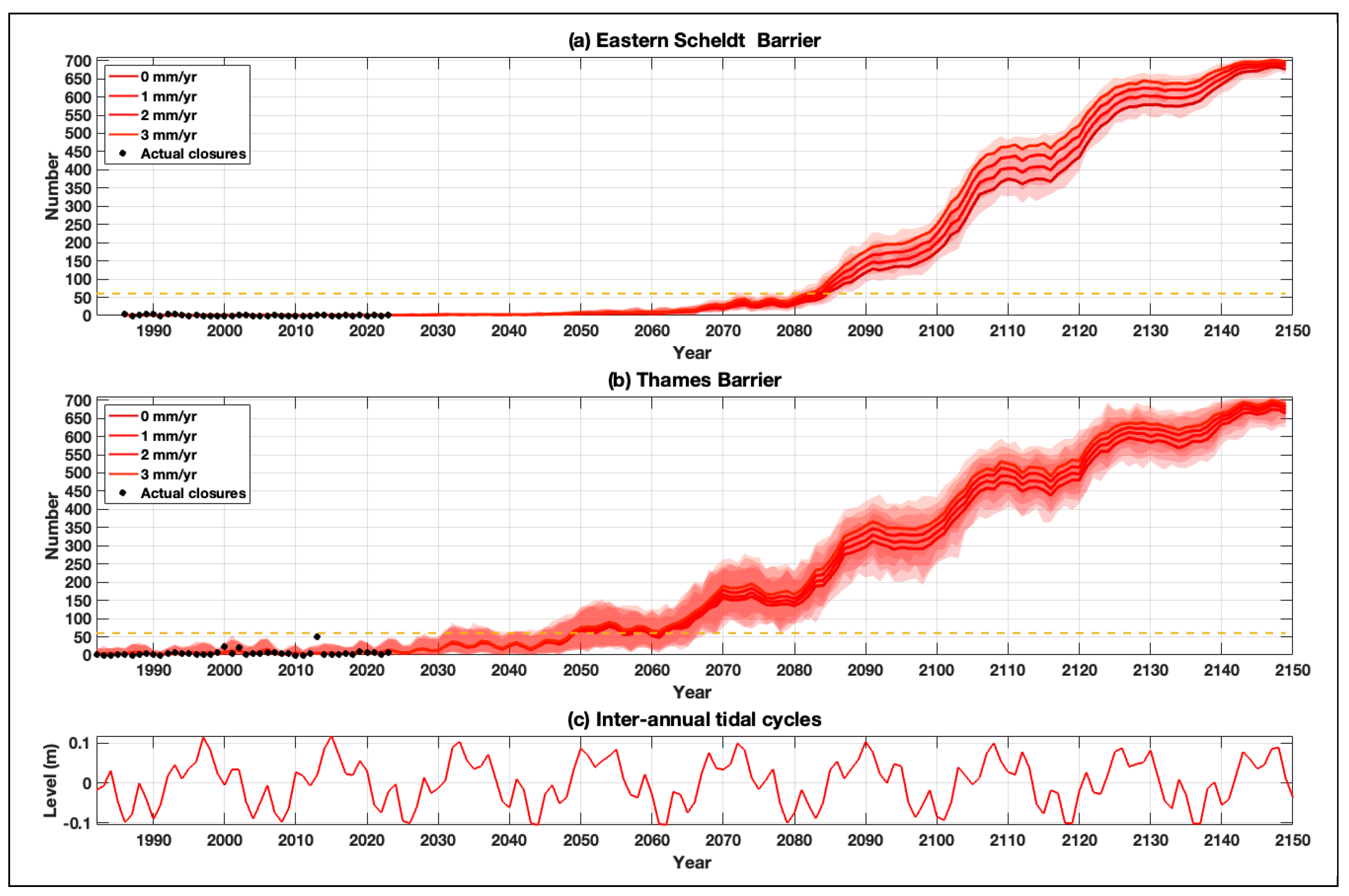

Third, we consider changes in tidal range. Often it is assumed tides will remain stationary into the future. However, over the last few decades, a growing number of studies have identified widespread, sometimes regionally coherent, positive and negative trends in tidal levels during the 19th, 20th and early 21st centuries at sites around the world (see Haigh et al., 2020a and references within). Jänicke et al. (2021) identified trends in tidal range in the North Sea of up to several millimetres per year Such changes to tides could therefore impact extreme water levels. Predictions of future changes in tides have been made by, for example, Pickering et al. (2021; 2017) and Schindelegger et al. (2018). As a sensitivity test, we ran simulations in which we increase the tidal range at both barrier sites by 0, 1, 2 and 3 mm/yr. For consistency with other scenarios described above, we ran these 4 simulations with the high emission SLR scenario (83rd percentile of projection SSP5-8.5) and a water level forecast error of 0.2 m for both barriers.

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) in number of closures each year, for the 4 scenarios in which we have increased tidal range, is shown in

Figure 7a for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier and

Figure 7b for the Thames Barrier. The average number of closures each year for the tidal range change scenarios, averaged over each decade, are listed in

Table 4. The increases in closures driven by changes in tidal range are, like for changes in skew surges, significantly smaller than those driven by SLR. Never-the-less, increases in tidal range, as expected, drive an increase in closures. Again, the spread of results is larger for the Thames Barrier than for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier. For each of the 4 tidal range increases (i.e. 0, 1, 2 and 3 mm/yr) the number of closures of the Eastern Scheldt Barrier increases from an average of 1.1, 1.1, 1.1 and 1.1 times per year in 1990-2000, to 3.1, 3.3, 3.5 and 3.7 in 2040-50, to 135, 156, 177 and 201 in 2090-2100, to 667, 678, 687 and 693 times per year in 2140-2150, respectively. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2100-2110 with 32, 64 and 93 extra closures per year for the corresponding 1, 2 and 3 mm/yr increases, compared to no increase in tidal range. The number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases from an average of 4.0, 4.0, 4.0 and 4.0 times per year in 1990-2000, to 31, 33, 34 and 36 in 2040-50, to 298, 316, 335 and 353 in 2090-2100, to 659, 670, 679 and 686 times per year in 2140-2150, for the 4 tidal range scenarios considered, respectively. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2090-2100 with 19, 38 and 55 extra closures for the corresponding 1, 2 and 3 mm/yr increases, compared to no increase in tidal range.

Fourth, we consider changes in river discharge, just for the Thames Barrier. Increases in rainfall are predicted to occur in the future over Northern Europe (Palmer et al., 2018), which is likely to drive an increase in river discharge. For the Thames we use projections provided by Environment Agency (2022), from the Maidenhead and Sunbury Catchment, directly upstream of Teddington Weir. Projections are in the form of percentage increases in river flow for the 3 epochs: 2020s (2015 to 2039); 2050s (2040-2069) and 2080s (2070-2125), relative to the 1981 to 2000 baseline, for 4 future emission scenarios, as follows:

- 5.

No change in river flow;

- 6.

A central projection based on the 50th percentile, corresponding to a 14%, 17% and 35% increase in river discharge for the 3 epochs, respectively;

- 7.

A higher projection based on the 70th percentile, corresponding to a 19%, 25% and 47% increase in river discharge for the 3 epochs, respectively; and

- 8.

An upper projection based on the 95th percentile, corresponding to a 32%, 45% and 81% increase in river discharge for the 3 epochs, respectively;

We interpolated these projections onto the ~twice-daily high-water time series from the start of the year when the two barriers became operational until 2150, extrapolating beyond the third epoch.

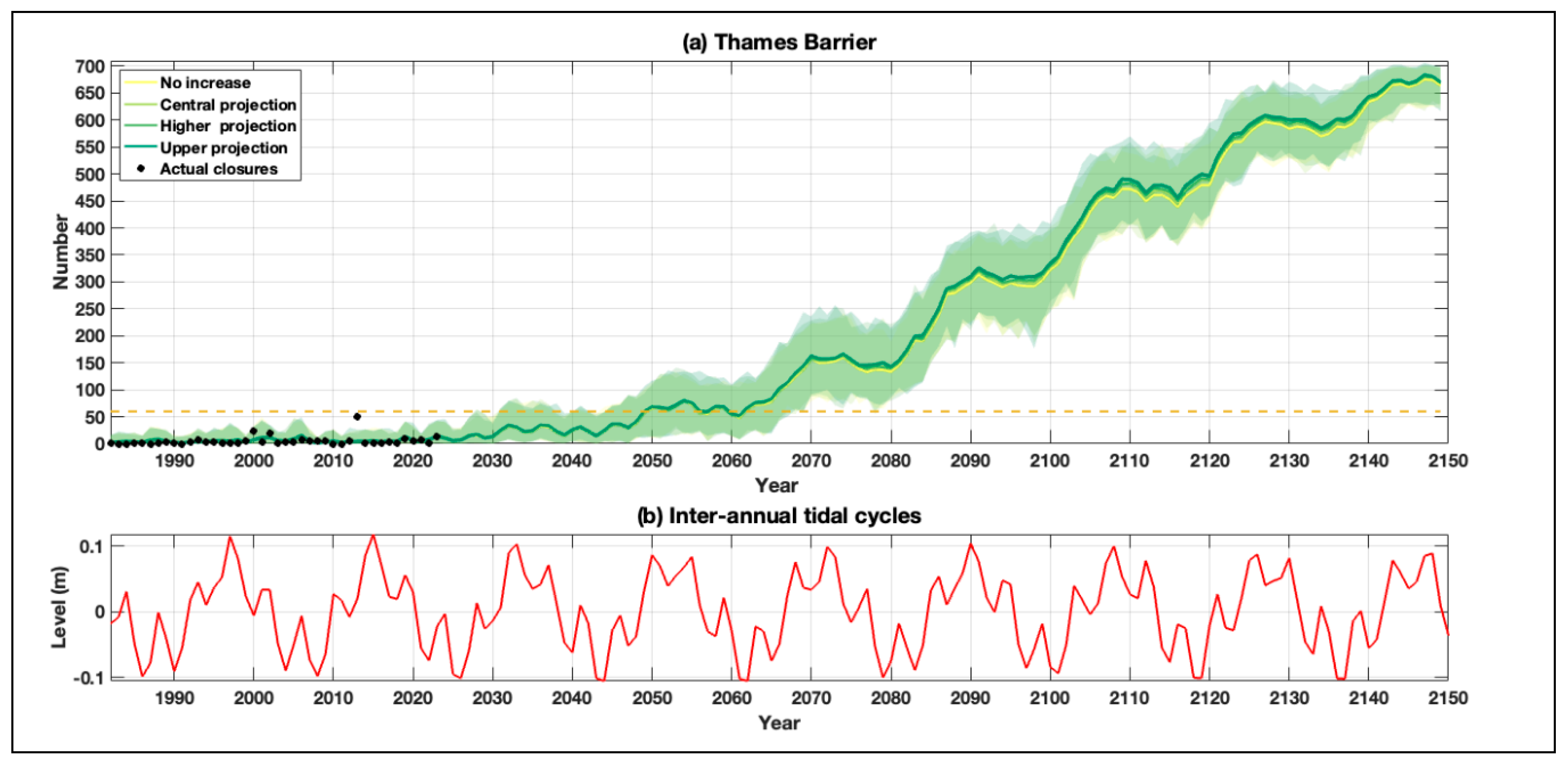

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) of the number of closures each year, for the scenarios in which we have increased river discharge, are shown in

Figure 8a for the Thames Barrier. The average number of closures each year for the changes in river discharge, averaged over each decade, are listed in

Table 5. The increases in barrier closures driven by changes in river discharge are significantly smaller than those driven by SLR, and smaller than those driven by changes in skew surges and tidal range. Nevertheless, increases in river discharge drive a small increase in barrier closures. For each of the 4 scenarios considered, the number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases from an average of 4.0, 3.9, 4.0 and 4.0 times per year in 1990-2000, to 31, 31, 32 and 32 in 2040-50, to 298, 303, 306 and 312 in 2090-2100, to 659, 663, 664 and 667 times per year in 2140-2150, respectively. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2110-2120 with 8, 10 and 18 extra closures per year for the corresponding three scenarios, compared to no increase in river discharge.

Finally, we consider different water level forecast errors, to highlight the important point that the number of times barriers have to close can be decreased by reducing the forecast error. For both study barriers, we ran scenarios with the water level forecast error set as 0, 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 m. For consistency, we ran these simulations with the high emission SLR scenario (83rd percentile of projection SSP5-8.5).

The average (solid line) and range (shaded area) in number of closures each year, for the scenarios in which we altered water level forecast error, is shown in

Figure 9a for the Eastern Scheldt Barrier and

Figure 9b for the Thames Barrier. The average number of closures each year for these 4 different forecast errors, averaged over each decade, are listed in

Table 6. For each of the 4 water level forecast errors the number of closures of the Eastern Scheldt Barrier increases from an average of 0.4, 0.7, 1.1 and 1.8 times per year in 1990-2000, to 1.2, 1.9, 3.1 and 5 in 2040-50, to 52, 86, 135 and 200 in 2090-2100, to 602, 640, 667 and 685 times per year in 2140-2150. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2110-2120 with 78, 159 and 233 extra closures per year for the corresponding 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 m forecast error, compared to zero forecast error. The number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases from an average of 1.0, 2.0, 4.0 and 8.1 times per year in 1990-2000, to 10, 19, 31 and 49 in 2040-50, to 194, 244, 298 and 352 in 2090-2100, to 609, 637, 659 and 676 times per year in 2140-2150. The maximum increase in closures is in the decade 2090-2100 with 50, 105 and 159 extra closures per year for the corresponding 0.1, 0.2 and 0.3 m water level forecast error, compared to zero forecast error.

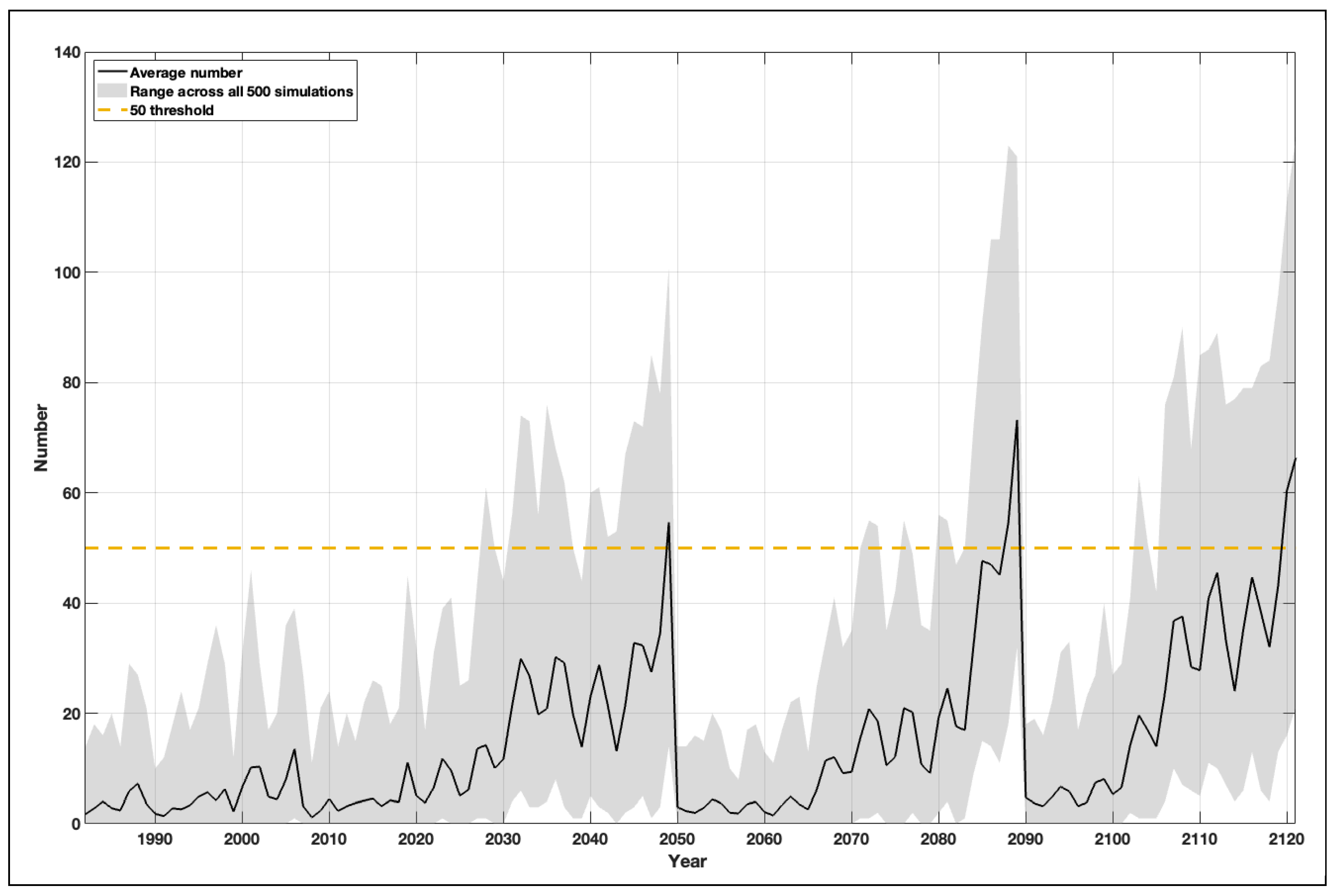

3.5. Adaptative Management

In this section, we illustrate how the tool presented here can be used to guide adaptive flood management approaches including storm surge barrier upgrade/replacement planning (Objective 3). We illustrate this by considering the Thames Barrier in London and associated defences.

In 2012, the UK Environment Agency launched the Thames Estuary 2100 (TE2100) Plan to provide strategic direction for the continued management of flood risk in the Thames Estuary through to the end of the 21st century and beyond (Environment Agency, 2012). This Plan was one of the world’s first flood risk management plans to have an adaptive strategy, which embraced uncertainty in future changes in climate change. The plan was adaptive in two ways. First, the Plan was adaptive in that a possible ‘route’ of ‘no regrets’ defence upgrades could be initially followed, with decisions on the most appropriate future pathway, e.g. raising the existing Thames Barrier or constructing a new barrier, being made later as understanding of the rate and risks of climate change improves. Second, the Plan was adaptive regarding the timing of defence upgrades, e.g. raising defences downstream of the Thames Barrier and decision dates for future pathways, can be brought forward if mean and extreme sea levels are found to be increasing faster than predicted. For an adaptive plan to be effective, it must be monitored and regularly reviewed. A monitoring review and a full update of the Thames Estuary 2100 Plan are undertaken every 5 and 10 years, respectively, to determine if it is necessary to alter the flood risk policies, or timing of the actions, outlined in the original Plan. The first monitoring review was completed in 2016 (Environment Agency, 2016) and the first full update was completed in 2023 (Environment Agency, 2023). Within these reviews and updates 10 key indicators are monitored, namely: (1) sea level rise; (2) extreme water levels; (3) river flows; (4) condition of flood defences; (5) Thames Barrier operations; (6) people, property, infrastructure and policy; (7) extent of erosion and deposition; (8) habitat; (9) social, cultural and commercial value; and (10) public and institutional attitudes to flood risk. Following the introduction of the TE2100 Plan, adaptive flood risk management approaches are increasingly being adopted in other locations around the UK and worldwide (e.g. Brisley et al., 2016; Haasnoot et al., 2019).

The operation of the Thames Barrier is one of the 10 key indicators being monitored in the reviews and full updates of the TE2100 Plan. As discussed in the 10-year full update (Environment Agency, 2023) it is vital that the number of Thames Barrier closures are kept within a manageable limit to maintain its reliability and minimise impacts on water quality and river traffic. This is currently set at an average of 50 per year for strategic planning purposes, although the barrier will be closed a greater number of times if required to protect London. The more a barrier closes, the greater the risk of that barrier not being able to operate and there is less time available for maintenance of the barrier and for vessels to navigate through it. As the results in

Section 5 have shown, the number of closures of the Thames Barrier could start to reach 50 closures per year as early as 2030’s, due to the peak of the 18.6-year nodal cycle, and exceed an average of 50 closures per year from the 2040s onwards with the high-end SLR scenario, 2050s with the high and medium emission scenarios, and 2060s with the low emission scenario (

Figure 4b and

Table 2). To reduce the number of barrier closures and keep it within the limit of an average of 50 closures per year, the TE2100 Plan involves reducing the number of combined tidal/fluvial closures, improving water level forecasts (thus reducing forecast errors) and raising defences upstream of the barrier by up to 0.5 m by 2050 and a further 0.5 m by 2090, with a major upgrade/replacement of the Thames Barrier by 2070. We designed the barrier closure prediction tool so that it could be used flexibly, allowing different closure rules and water level forecast errors to be defined for different years, and our tool was used to assess and guide decisions in the 10-year review of the TE2100 Plan.

To illustrate the way in which we can use the tool to guide adaptative flood management of surge barriers, we have run example simulations in which we alter the closure matrix for the Thames Barrier. For the period 1982/83 to 2049/50 we use the existing closure matrix, an illustration of which is shown by the solid line in

Supplementary Figure S7. For the period 1950/21 to 2089/90 we increase the water level height of the closure matrix by 0.5 m. This corresponds with a planned 0.5 m raise in tidal defences upstream of the barrier, completed by 2050 (Environment Agency, 2023). We also adjust the matrix, to reduce the number of combined tidal/fluvial closures, by increasing the river discharge thresholds, for higher discharge values, relative to the water level. This modified closure matrix is illustrated by the dotted line shown in

Supplementary Figure S7. For the period 2090/91 to 2149/50 we increase the water level height of the closure matrix by a further 0.5 m (1.0 m relative to the original closure matrix), corresponding with a planned further 0.5 m rise in tidal defences upstream of the barrier, completed by 2090 (Environment Agency, 2023). This modified closure matrix is illustrated by the dashed line shown in

Supplementary Figure S7. The number of estimated barrier closures, across all 500 simulations, is shown in

Figure 10, assuming a high emission SLR scenario (83

rd percentile of projection SSP5-8.5), no change in tidal range, skew surge or river discharge and a water level forecast error of 0.2 m. The average number of closures of the Thames Barrier increases and reaches an average of 50 closures per year, just prior to 2050. However, with the first modified closure matrix (corresponding to a 0.5 m increase in the height of defences upstream of the barrier by 2050 and the reduction in combined tidal/fluvial closures), the number of closures reduces back to average levels observed between 1982/83 and 2023/24. With SLR accelerating, the number of closures increases back to an average of 50 closures per year, prior to 2090, but then subsequently reduces back to present/day average levels, when the second modified closure matrix is used, before increasing again to an average of more than 50 closures just prior to 2120. The two raisings of upstream defences, along with the reduction in combined tidal/fluvial closures, would essentially buy time, allowing the barrier to continue to efficiently function and be maintained. In the original 2012 Plan, the raising of the upstream defences was planned for 2065 and 2100, but was brought forward to 2050 and 2090, reflecting the results presented here. This therefore illustrated the flexibility of the tool, and because it is computationally efficient it can be used to quickly run a wide variety of different scenarios within an adaptive framework.