Overview of Bioremediation and Lead Poisoning

Since the advent of human civilization, anthropogenic activities have altered the environment, often negatively impacting human and environmental health (1). This issue has escalated with industrialization, driving the use of chemicals, pesticides, and heavy metals, causing widespread pollution of soil, land, and water (1). The rise in pollution, coupled with a growing population and varying global standards, has intensified environmental concerns (2). Traditional remediation methods, which involve transporting contaminated soil to landfills, merely shift the problem without solving it (3,4).

Heavy metals can be removed through physical remediation, chemical remediation, or bioremediation (4, 5). Bioremediation is an innovative technology that employs biological agents such as bacteria, fungi, algae, yeasts, molds, and plants to eliminate, detoxify, transform, or neutralize heavy metals (6). Unlike several physicochemical techniques, bioremediation is cost-effective and efficient. Microorganisms play a significant role in bioremediation, proficiently dissolving and participating in the oxidation and reduction of heavy metals (6, 7). Utilizing microorganisms' metabolic abilities for heavy metal pollution eradication is a form of green technology.

Bioremediation uses naturally occurring or deliberately introduced microorganisms, plants, or other life forms to break down environmental pollutants, presenting a promising solution due to its economic advantage, enhanced efficiency, and environmental friendliness (6, 7). This technology can be categorized into in situ and ex situ methods, employing aerobic, anaerobic, or both types of microorganisms. Techniques like rhizoremediation, phytoremediation, and vermicomposting further augment bioremediation. A significant advantage of bioremediation is its ability to operate on-site, reducing transportation costs and detoxifying pollutants into carbon dioxide, water, and biomass, offering a sustainable alternative to expensive cleanup machinery (8).

Lead Poisoning: a historical perspective

Humankind has utilized lead for nearly 6,000 years, with documented poisoning cases spanning at least 2,500 years (9). The Romans identified the link between lead exposure and toxicity in the 1st century. They used lead pots to preserve and sweeten wine, leading to widespread lead poisoning in ancient Rome. Some suggest that this widespread poisoning contributed to the decadence and eventual fall of the Roman Empire. In the 19th century, lead poisoning reemerged as a significant issue during industrialization, prompting comprehensive clinical studies and initial preventive efforts (9,10). However, understanding of lead poisoning remained clinical until the late 20th century when subclinical and early forms of lead toxicity were recognized, leading to stricter hygiene standards.

Pediatric lead poisoning became a severe concern with the introduction of tetraethyl lead in gasoline in the 1920s (10, 11). Restrictions on lead use in the 1980s significantly reduced blood lead levels (12). However, lead still poses a health hazard in the 21st century, as tragically underscored by the Flint water crisis in the United States (12, 13). Lead levels in the environment have increased more than a thousand times since the 18th century, primarily due to fossil fuel combustion and factory operations (14). The United States is the second-largest producer of refined lead, contributing less than 10%, while China accounts for over 40% of the world's total refined lead production (13, 14). Lead is used in various industries, including the production of lead-acid batteries, ammunition, metal products, and X-ray shielding devices. However, recent events like the Flint water crisis have led to a decrease in global refined lead production (14, 15).

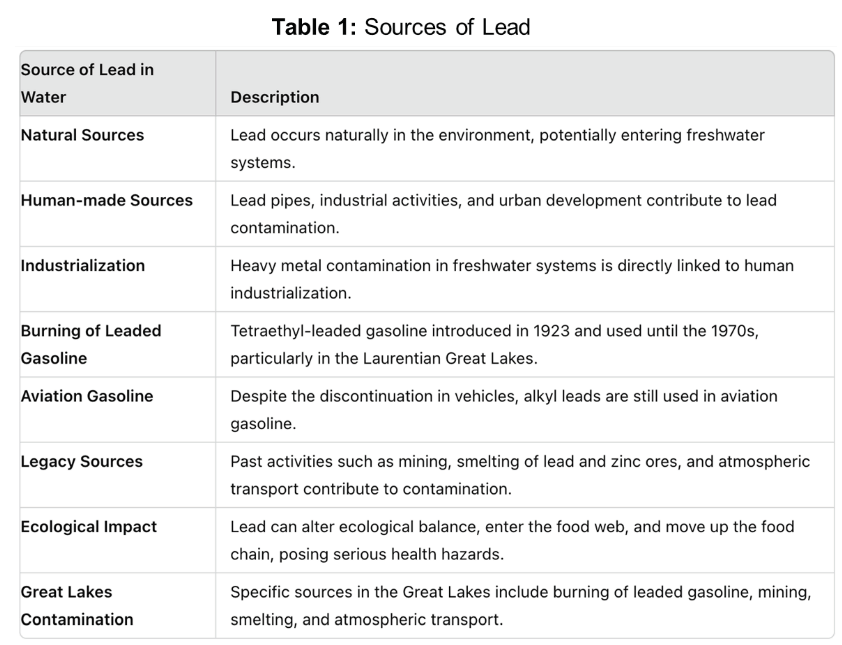

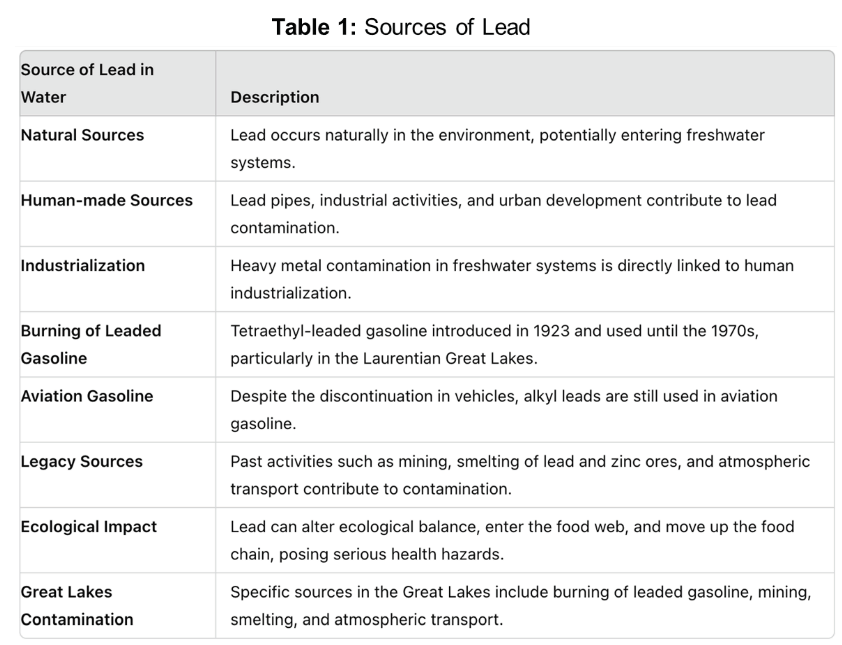

Sources of Lead in Water

Lead, even at low concentrations, can be highly persistent and toxic, causing serious health hazard and environmental stress (16). It alters the ecological balance. Heavy metals, including lead can occur in freshwater environments in dissolved, colloidal, and particulate forms, differing in bioavailability and toxicity (17, 18). Once present in the aquatic environment, either natural or from human made (lead pipes as in Flint), lead can enter the food web and move up the food chain, thus becoming serious human health hazard (19). Human industrialization has directly linked heavy metal contamination of freshwater systems (Table 1). For example, in the Laurentian Great Lakes, heavy metals like copper, iron, lead, and mercury are linked to the area's development (17, 18). Lead contamination in the Great Lakes is primarily due to the burning of tetraethyl-leaded gasoline introduced in 1923 (20). Despite discontinuing leaded gasoline in vehicles after the 1970s, alkyl leads are still used in aviation gasoline. Legacy sources of lead in Lake Michigan include mining, smelting of lead and zinc ores, and atmospheric transport (20). Conventional remediation methods are not environmentally or economically sustainable, making bioremediation a more viable solution.

Mechanism/Pathway of Bioremediation Processes of Lead

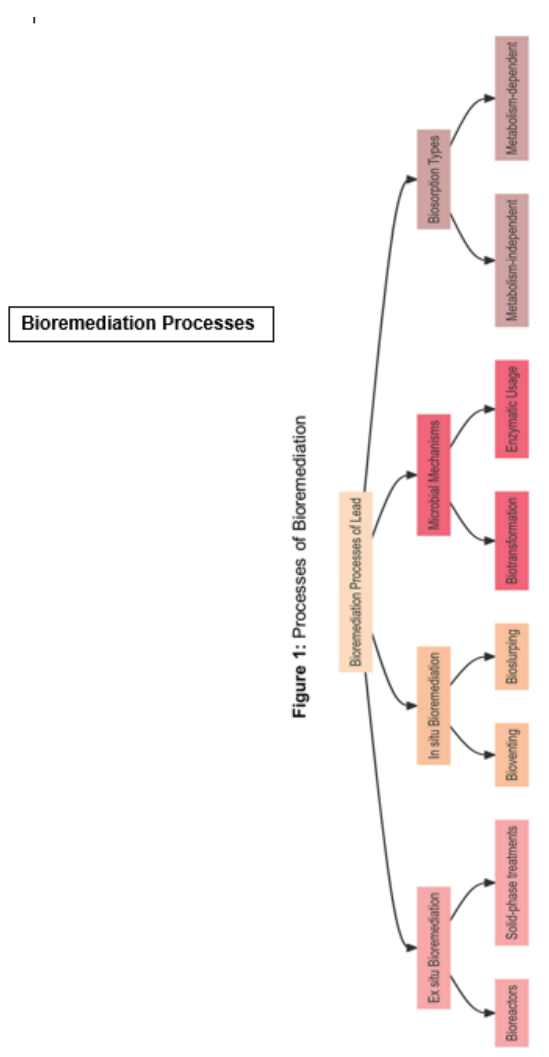

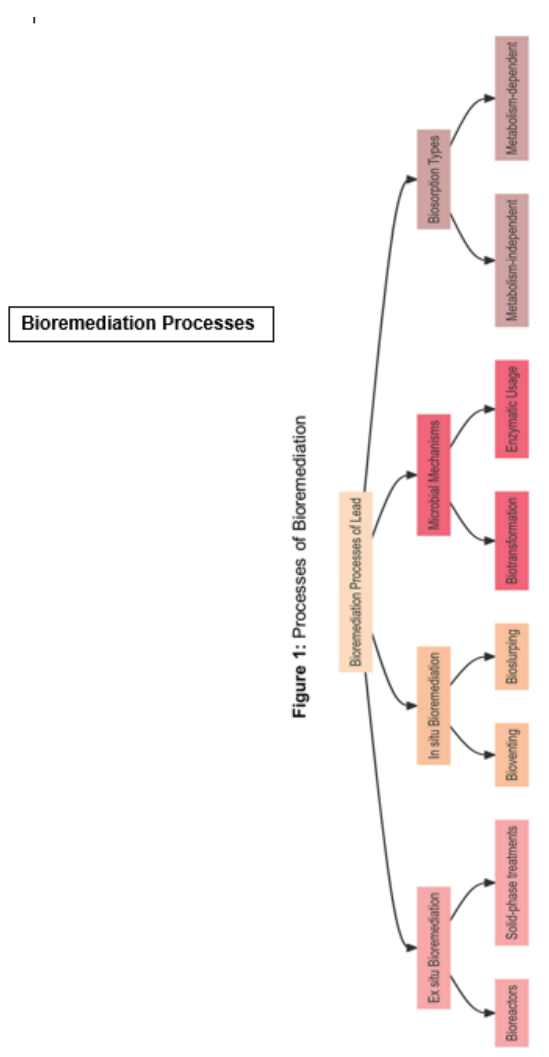

Microbial bioremediation techniques involve identifying novel microbes at contamination sites with significant potential to reduce pollutants (21, 22). Microbial consortia include genetically modified strains to enhance bioremediation by promoting bioaccumulation and biodegradation mechanisms (summarized in Figure 1). Bioremediation can be either ex situ or in situ (21, 22, 23). Ex situ involves physically removing contaminated waste to a different location using bioreactors, solid-phase treatments, biopiles, or windrow techniques. In situ bioremediation treats pollutants at their origin with minimal soil disturbance, employing techniques like bioventing and bioslurping to enhance microbial activity and pollutant degradation.

The microbial species have evolved to utilize distinct mechanisms for survival or detoxification and/ or developing resistance to heavy metals in the environment. They include, but are not limited to, mechanisms such as gene regulation, chemical transformations such as chelation through the production of specific compounds like metallothionein, altering enzymatic pathways, generating exopolysaccharides and biosurfactants, or undergoing biotransformation (23-29). For instance, bacteria titrate, i.e. either upregulate or downregulate the expression of genes that are responsible for heavy metal efflux or sequestration in direct response to the amounts of heavy metal in their environment (30, 31). They can also regulate chemical interactions that involve ion exchange, redox or electrostatic properties to regulate the uptake or efflux of heavy metals (32, 33). Metal efflux or metal-ligand degradation mechanisms or generation of anionic structures on the cell wall that include NH2, COO-, thiol, or sulfonyl groups that bind to adsorb the heavy metal cations through biosorption are amongst the processes utilized by bacteria (34, 35). Thus, bacteria utilize a variety of mechanisms to deal with heavy metal toxins, and the preferred mechanism is a function of species and the amount and type of heavy metal in the environment.

The microbial species have evolved to utilize distinct mechanisms for survival or detoxification and/ or developing resistance to heavy metals in the environment. They include, but are not limited to, mechanisms such as gene regulation, chemical transformations such as chelation through the production of specific compounds like metallothionein, altering enzymatic pathways, generating exopolysaccharides and biosurfactants, or undergoing biotransformation (23-29). For instance, bacteria titrate, i.e. either upregulate or downregulate the expression of genes that are responsible for heavy metal efflux or sequestration in direct response to the amounts of heavy metal in their environment (30, 31). They can also regulate chemical interactions that involve ion exchange, redox or electrostatic properties to regulate the uptake or efflux of heavy metals (32, 33). Metal efflux or metal-ligand degradation mechanisms or generation of anionic structures on the cell wall that include NH2, COO-, thiol, or sulfonyl groups that bind to adsorb the heavy metal cations through biosorption are amongst the processes utilized by bacteria (34, 35). Thus, bacteria utilize a variety of mechanisms to deal with heavy metal toxins, and the preferred mechanism is a function of species and the amount and type of heavy metal in the environment.

Biosorption of heavy metal bacteria is either dependent or independent of metabolism (36-39). The metabolism-independent biosorption occurs at the exterior of the cell while dependent biosorption is intracellular in nature that include redox reactions, species transformations, and sequestration methods (38, 39). The extracellular sequestration of metallic ions involves components of the cell in the periplasm or the gathering of metallic ions as insoluble compounds through production of genes that promote metal resistance that are often induced by the specific heavy metal. The intracellular sequestration of metals can be exploited for the treatments of effluents (40). Microbes can interchange metal ions from one oxidation state to another, resulting in the reduction of harmfulness (41, 42). Metals and metalloids are used by bacteria as electron donors or acceptors throughout the energy-generation process (43, 44).

Mechanisms of lead bioremediation by bacteria: Bacteria are ubiquitous in the natural environment and some can thrive in an environment polluted by heavy metals, including lead (45). The toxic heavy metals are converted by these bacteria into non-toxic forms. Bacteria maintain a defense mechanism in two ways (i) for targeted pollutants develop degrading enzymes (ii) resisting related heavy metals (46). Bacteria utilize several strategies: adhesion, immobilization, oxidation, processing, and volatilization of heavy metals. By understanding the mechanisms that regulates the strategies will enable development of bioremediation processes that can be more effective (47). Microbe-metal mechanisms of interaction allow for various processes such as biotransformation, biosorption, biomineralization, bioleaching and bioaccumulation as modes of bioremediation (Figure 2).

Biosorption is a biological physicochemical process that is employed for the removal of recalcitrant compounds, including metal ions (48). The analysis of the supernatant derived from suspension cultures of bacteria revealed that the primary factor responsible for metal sequestration is the soluble exopolysaccharides that facilitate biosorption heavy metals, including lead (Pb) (49). The secretion of exopolysacchardies has been observed in various bacterial strains (discussed below in more detail). They include, but not limited to Bacillus, Paenibacillus etc (50, 51). The biosorption of the exopolysaccharide molecule depends on the type of the heavy metal. For instance, the capacity to eliminate Pb is distinct for different distinct exopolysaccharide molecules. It is regulated by the electrostatic interactions that occur between the negatively charged functional groups of exopolysaccharide and the positively charged Pb ion (52). It is also influenced by the bacterial immobilization processes, including the attachment and encapsulation methods, are utilized by the bacteria (53).

Bioleaching mechanisms is another process that is employed by the microbes for removal of lead (54). This process is highly dependent on the pH. For example reduction in pH and increase in oxidation–reduction potential creates an optimal environment for the removal of lead. The process of bioleaching can occur either through the direct metabolic activity of leaching bacteria or indirectly through the by-products of bacterial metabolism (55).

Biomineralization refers to the process by which various solid minerals, such as carbonates, phosphates, silicates, and sulphates are formed from lead (heavy metal) ions that are subsequently precipitated by microorganisms (56). Biomineralization is contingent upon urea hydrolysis, pH, and temperature and utilized not only by bacteria but also by other microorganisms, including photosynthetic microorganisms and other microbes utilizing autotrophic and heterotrophic pathways (57). Genetic engineering of bacteria to affect processes like oxidation-reduction and other desirable traits to enhance biosorption, bioaccumulation, bioleaching etc could be utilized (58). Both intracellular and extracellular mechanisms, in which passive absorption is limited, determine the bioaccumulation process. Metagenomics and metatranscriptomics analysis highlighting the function of major genes and pathways provide for potential targets for genetic engineering to enhance bioremediation by the bacteria. involved in bioaccumulation (59, 60).

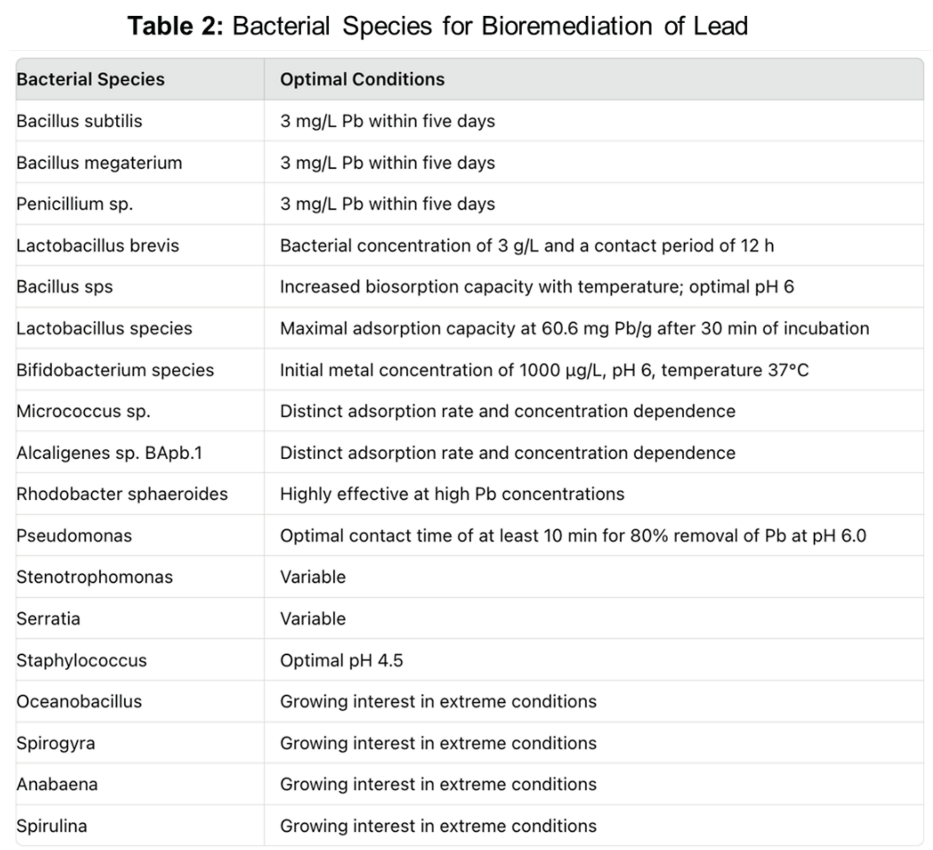

Bacterial species for bioremediation of lead

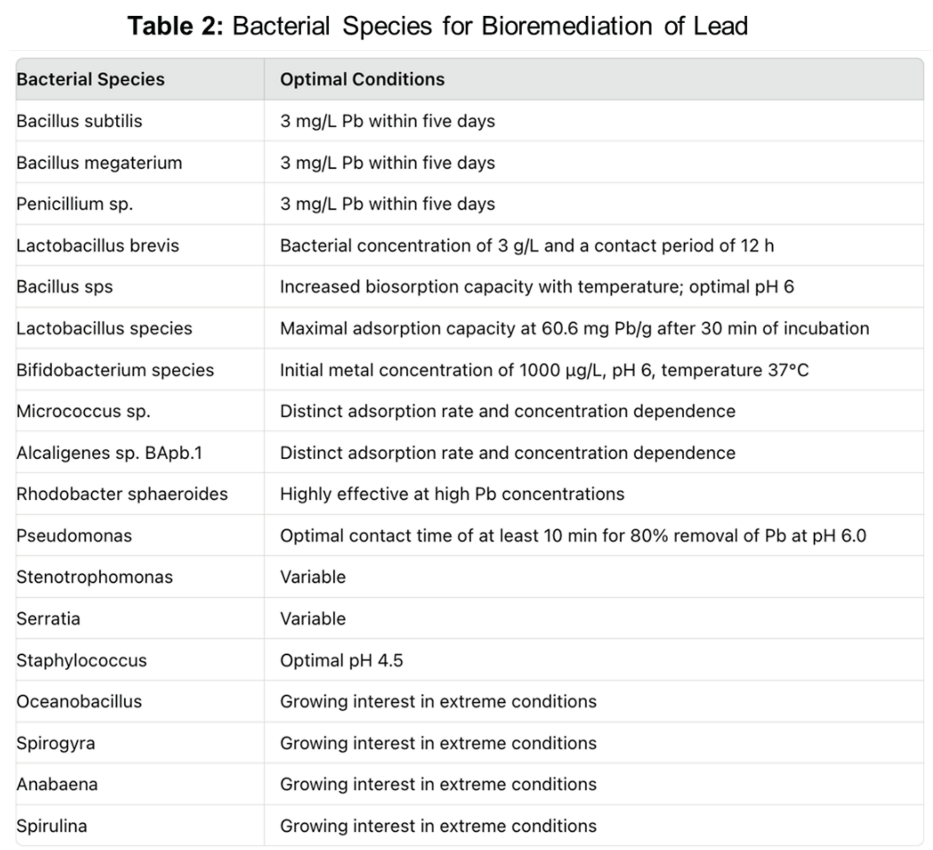

Bacteria are specifically suited for remediation of metals from environment. Several features and mechanisms of bacteria, either individually or collectively, that can be exploited for bioremediation of heavy metals will be reviewed briefly below and summarized in Table 2. The nature of the bacterial cell-wall can be exploited for biosorption of heavy metals (61-63). Bacteria, that survive in metal-stressed environments evolved multiple cell-wall related mechanisms to tolerate metal ion uptake. Biosorption to cell walls and entrapment in the extracellular capsule, pre-capitation the efflux of metal ions outside the cell, encasing them in extracellular capsules, precipitation, complexation, in addition to enzymatic oxidation-reduction reactions, buildup of metal ions in a less poisonous state, and chemisorption of metal ions are some of the mechanisms (64). Because of the presence of novel catabolic enzymes, bacterial strains can survive in a variety of ecological niches (65).

Numerous bacterial strains have been isolated and characterized for their ability to reduce lead in liquids and in soil. Bioaccumulation is the most efficient method of metal removal from aqueous medium by bacterial strains, and it is predicated on the bacterial cell’s metabolic activity (58). Specifically, for instance, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus megaterium, and Penicillium sp. reduced 3 mg/L Pb within five days (66). By contrast the biosorption of Pb by Lactobacillus brevis is best at bacterial concentration of 3 g/L and a contact period of 12 h (67). The biosorption of Pb ions by Bacillus sps is greatly impacted by temperature and when temperature was increased, the biosorption capacity also increased (67). Similarly pH also had significant effect on biosorption capacity and when pH was adjusted 3, the biosorption is poor, and it increased as pH climbed and reach its greatest binding of Pb was optimal at pH 6 and hereafter it decreased when pH increased over 6 (56, 58, 68).

Different bacterial species show variation based on not only on pH but also the underlying concentration of lead and the time period of incubation in the laboratory and mechanisms employed by the bacterial species may be distinct (69). For example, some Lactobacillus species that had maximal adsorption capacity at 60.6 mg Pb/g after 30 min of incubation (70). Mechanistic studies demonstrated morphology of the strain changed before and after Pb biosorption. The results revealed that Pb was primarily connected with bacterial cell surfaces, and that changes in surface morphology were caused by exopolysaccharide secretion (70). Different Lactobacillus species demonstrated that increasing pH and bacterial concentrations have major impact on lead removal capacity (69, 71, 72). Experimental data on lead removal by Bifidobacterium species was optimal at initial metal concentration was 1000 μg/L, pH 6 and temperature 37°C (72, 73). By contrast, Micrococcus sp. isolated from effluent sample of electroplating industry in India showed ability to produce amylase, and bioremediate Pb at an adsorption rate and concentration dependence that was distinct from the Alcaligenes sp. BApb.1 species isolated from China (74, 75). Another Pb-resistant strain Rhodobacter sphaeroides is also highly effective at Pb removal at a high concentrations of Pb (76). Besides Lactobacillus, other Firmicutes also possess variable potential to eliminate Pb (77).

It is important to note that certain of these features for lead biosorption are also exhibited by bacteria that are known human pathogens. Bacteria that cause significant human morbidity and mortality such as Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, Serratia and Staphylococcus also have capacity for lead biosorption (78-82). Once again, the pH and the concentration of the lead, the contact time remain critical features. For example, biosorption potential of a species of Pseudomonas showed an optimal contact time requirement of at least 10 min for 80% removal of Pb at an optimal pH of 6.0 (83). The biosorption potential of Staphylococcus for Pb is more acidic (pH 4.5) (84). Thus amongst the bacteria that regulate lead, the temperature, pH, biomass and Pb concentration are critical factors that affect the biosorption process. While several pathogenic bacteria are discussed, other microbial organisms that are pathogenic, especially in immune-compromised individuals, such as fungi, have been described to possess substantial lead bioremediation capabilities, but are not discussed here in order to keep the focus of the review on bacteria.

There is also growing interest and some evidence that other anaerobic microbes and extremophiles, that grow at diverse pH, temperature and other harsh conditions could be leveraged for lead bioremediation (85). Microbes such as Oceanobacillus, Spirogyra, Anabaena, Spirulina, and others (85). Furthermore, most studies have been done to explore the characteristics and optimal features in bioremediation capabilities of bacteria in isolation. The role and functions, in the context of whole microbiome- the ecological niches, and the synergies and antagonistic interactions that can impact lead bioremediation will need to be analyzed before the strategies can be reliably applied in diverse lead laden water contamination. Utilization of emerging nanotechnologies with carefully designed artificial intelligence modelling along with genetic engineering may usher in new era of leveraging microbial bioremediation strategies against lead contamination of water to make it a more efficient, broad, cost-effective technique when compared to other physical and chemical methods.

Advances in Bacterial Technologies for Lead Bioremediation

Extensive endeavors have been undertaken over a prolonged period to tackle the persistence of lead contamination in the environment. Notwithstanding changes in industries that used lead, the issue persists as demonstrated by the Flint water crisis even in resource rich country like the United States (13, 14). To mitigate the potential ecological ramifications of lead pollution, it is imperative to develop innovative and robust ecological technologies that can effectively utilized to reclaim lead from contaminated environments, including water. As noted above, the utilization of microbial bioremediation could be a cost-effective approach to address this issue. Several novel technologies might hold promise for bioremediation of lead from water and environment. They include microbial fuel cells, biofilm, nanotechnology, and as mentioned earlier, genetic engineering.

Microbial Fuel Cells: Microbial fuel cells (MFCs) have been identified as a feasible approach to mitigate environmental contamination (86). MFCs convert chemical energy into electrical energy via oxidation mechanisms facilitated by microorganisms or enzymatic catalysis (87). These are thus bio-electrochemical devices that facilitate the decomposition of organic waste into smaller molecules, liberating protons and electrons, which production of energy. Briefly, microorganisms, such as bacteria, generate electrons and protons at the anode through the process of oxidizing organic materials and assimilate metal ions into their biomass (88). The transportation of electrons occurs through an external circuit, while the diffusion of protons toward the cathode takes place through the solution while a chemical with a high redox potential such as heme molecules function as the electron acceptor (89). MFCs offer certain advantages over conventional fuel cells because the production of fuel is achieved through the utilization of diverse organic or inorganic materials, including but not limited to soil sediments and organic water waste (86, 87). However, currently the technology as yet generates suboptimal electrical generation. More research is needed to enhance the approach as a long-term viable strategy across resource rich and poor regions.

Nano-technology: The employment of nanotechnology offers considerable opportunities for environmental bioremediation of lead (90). The principal modality by which nanomaterials eliminate heavy metals, including lead, is through their elevated adsorption capacity for them. Carbon nanotubes have demonstrated exceptional adsorption capabilities towards Pb (and other heavy metals) (90, 91). However, its utilization for the purpose of removing lead is likely cost-prohibitive (91, 92). The utilization of silica-based nanomaterials is also a possibility to extract lead (93). Lead biosorption can be achieved through the utilization of nano-silica as the foundation for nanocomposites and the silica-based nanomaterials are non-toxic (90, 93). The use of microorganisms and bio-fabrication of nanoparticles offers a potentially even more viable and environmentally safer bioremediation approach for removal of lead from water. Chemically generated nanomaterials may have are limited when used in aqueous solutions because of potential for self-agglomeration. By contrast, nanomaterials synthesized with natural sources like bacterial, fungal enzymes and plant extracts that may be a viable solution. In aqueous conditions, such nanoparticles achieve greater firmness due to co-precipitation or by putting bioactive compounds and protein to the external face of nanoparticles (90, 93, 94). Thus, in addition to natural bioremediation capability of the many bacteria, they also contribute to enhancing nanotechnology in many ways (94).

Biofilm and Genetic Engineering: In the context of environmental duress in the water, such as nutritional deprivation, pH, or temperature alterations, bacteria respond by synthesizing biomolecules called exopolysaccharides (95). These molecules can enhance the capacity of the bacteria to sequester or release heavy metals, which can be exploited for the bioremediation of lead. For instance, the generation of exopolysaccharides from a collection of bacteria from the same or different species, which is influenced by environmental stressors, can form biofilms that are anionic in nature (95, 96, 97). While the formation of biofilms protects bacteria from challenging environments, they also serve to sequester cationic heavy metals (95, 97). The generation of biofilms by bacteria can, therefore, serve as a potential mechanism that can be exploited for the removal of lead from water.

Rapidly evolving genome engineering techniques such as genetic engineering, metagenomics, meta-transcriptomics, CRISPR gene editing and recombinant DNA technology offer tremendous potential for bioremediation with bacteria (97-100). Metagenomics and metabolic investigations offer insights into microbial diversity, population, and functional composition with respect to metal resistance genes (98, 99). These findings can be leveraged to improve the efficacy of microbial strains in the removal or degradation of heavy metals such as lead. The field of genetic engineering will allow for large scale and highly efficient transfer of advantageous traits from one species to another, resulting in the development of specific strains for the purpose of bioremediating polluted water.

References

- Policies for accelerating access to clean energy, improving health, advancing development, and mitigating climate change. Haines A, Smith KR, Anderson D, Epstein PR, McMichael AJ, Roberts I, Wilkinson P, Woodcock J, Woods J. Lancet. 2007 Oct 6;370(9594):1264-81.

- The Lancet Commission on pollution and health. Landrigan PJ, Fuller R, Acosta NJR, Adeyi O, Arnold R, Basu NN, Baldé AB, Bertollini R, Bose-O'Reilly S, Boufford JI, Breysse PN, Chiles T, Mahidol C, Coll-Seck AM, Cropper ML, Fobil J, Fuster V, Greenstone M, Haines A, Hanrahan D, Hunter D, Khare M, Krupnick A, Lanphear B, Lohani B, Martin K, Mathiasen KV, McTeer MA, Murray CJL, Ndahimananjara JD, Perera F, Potočnik J, Preker AS, Ramesh J, Rockström J, Salinas C, Samson LD, Sandilya K, Sly PD, Smith KR, Steiner A, Stewart RB, Suk WA, van Schayck OCP, Yadama GN, Yumkella K, Zhong M. Lancet. 2018 Feb 3;391(10119):462-512.

- A comprehensive assessment of plastic remediation technologies. Leone G, Moulaert I, Devriese LI, Sandra M, Pauwels I, Goethals PLM, Everaert G, Catarino AI. Environ Int. 2023 Mar;173:107854.

- A Current Review of Water Pollutants in American Continent: Trends and Perspectives in Detection, Health Risks, and Treatment Technologies. Warren-Vega WM, Campos-Rodríguez A, Zárate-Guzmán AI, Romero-Cano LA. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 3;20(5):4499.

- Response surface optimization and modeling in heavy metal removal from wastewater-a critical review. Bayuo J, Rwiza M, Mtei K. Environ Monit Assess. 2022 Apr 8;194(5):351.

- Bioengineered microbes for soil health restoration: present status and future. Rebello S, Nathan VK, Sindhu R, Binod P, Awasthi MK, Pandey A. Bioengineered. 2021 Dec;12(2):12839-12853.

- Bioremediation of micropollutants using living and non-living algae - Current perspectives and challenges. Ratnasari A, Syafiuddin A, Zaidi NS, Hong Kueh AB, Hadibarata T, Prastyo DD, Ravikumar R, Sathishkumar P. Environ Pollut. 2022 Jan 1;292(Pt B):118474.

- Microbial Interventions in Bioremediation of Heavy Metal Contaminants in Agroecosystem. Pande V, Pandey SC, Sati D, Bhatt P, Samant M. Front Microbiol. 2022 May 6;13:824084.

- Historical documentation of lead toxicity prior to the 20th century in English literature.Jonasson ME, Afshari R. Hum Exp Toxicol. 2018 Aug;37(8):775-788.

- Lead Industry Influence in the 21st Century: An Old Playbook for a "Modern Metal". Gottesfeld P. Am J Public Health. 2022 Sep;112(S7):S723-S729.

- Blood lead levels in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Ericson B, Hu H, Nash E, Ferraro G, Sinitsky J, Taylor MP. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Mar;5(3):e145-e153.

- The pervasive threat of lead (Pb) in drinking water: Unmasking and pursuing scientific factors that govern lead release. Santucci RJ Jr, Scully JR. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020 Sep 22;117(38):23211-23218.

- Lead Poisoning in the 21st Century: The Silent Epidemic Continues. Hanna-Attisha M, Lanphear B, Landrigan P. Am J Public Health. 2018 Nov;108(11):1430.

- Pediatric lead exposure and the water crisis in Flint, Michigan. DeWitt RD. JAAPA. 2017 Feb;30(2):43-46. 14. The number of people exposed to water stress in relation to how much water is reserved for the environment: a global modelling study. Vanham D, Alfieri L, Flörke M, Grimaldi S, Lorini V, de Roo A, Feyen L. Lancet Planet Health. 2021 Nov;5(11):e766-e774.

- Towards safe drinking water and clean cooking for all.Ray I, Smith KR. Lancet Glob Health. 2021 Mar;9(3):e361-e365.

- Clinical and molecular aspects of lead toxicity: An update. Mitra P, Sharma S, Purohit P, Sharma P. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2017 Nov-Dec;54(7-8):506-528.

- Mass-Balance Modeling of Metal Loading Rates in the Great Lakes. Bentley C, Junqueira T, Dove A, Vriens B. Environ Res. 2022 Apr 1;205:112557.

- Water quality dynamics and underlying controls in the Halton Region, Ontario. Beckner-Stetson N, Funk K, Estabrooks M, Dunn A, Doulatyari B, Barrett K, Vriens B. Environ Monit Assess. 2024 Jun 29;196(7):677. [CrossRef]

- Social and Built Environmental Correlates of Predicted Blood Lead Levels in the Flint Water Crisis. Sadler RC, LaChance J, Hanna-Attisha M. Am J Public Health. 2017 May;107(5):763-769.

- Land-use legacies are important determinants of lake eutrophication in the anthropocene. Keatley BE, Bennett EM, MacDonald GK, Taranu ZE, Gregory-Eaves I. PLoS One. 2011 Jan 10;6(1):e15913.

- Beneficial microbiomes for bioremediation of diverse contaminated environments for environmental sustainability: present status and future challenges. Kour D, Kaur T, Devi R, Yadav A, Singh M, Joshi D, Singh J, Suyal DC, Kumar A, Rajput VD, Yadav AN, Singh K, Singh J, Sayyed RZ, Arora NK, Saxena AK. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 May;28(20):24917-24939.

- Microbial fuel cells: novel biotechnology for energy generation. Rabaey K, Verstraete W. Trends Biotechnol. 2005 Jun;23(6):291-8.

- Microbes with a mettle for bioremediation. Lovley DR, Lloyd JR. Nat Biotechnol. 2000 Jun;18(6):600-1.

- Picomolar concentrations of lead stimulate brain protein kinase C. Markovac J, Goldstein GW. Nature. 1988 Jul 7;334(6177):71-3.

- Lead absorption mechanisms in bacteria as strategies for lead bioremediation. Tiquia-Arashiro SM. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018 Jul;102(13):5437-5444.

- Microbial controls on metal mobility under the low nutrient fluxes found throughout the subsurface. Boult S, Hand VL, Vaughan DJ. Sci Total Environ. 2006 Dec 15;372(1):299-305.

- Exopolysaccharides from marine microbes with prowess for environment cleanup. Baria DM, Patel NY, Yagnik SM, Panchal RR, Rajput KN, Raval VH. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2022 Nov;29(51):76611-76625.

- Prospective of Microbial Exopolysaccharide for Heavy Metal Exclusion. Mohite BV, Koli SH, Narkhede CP, Patil SN, Patil SV. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2017 Oct;183(2):582-600.

- Lead absorption mechanisms in bacteria as strategies for lead bioremediation. Tiquia-Arashiro SM. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018 Jul;102(13):5437-5444.

- Well-controlled in-situ growth of 2D WO3 rectangular sheets on reduced graphene oxide with strong photocatalytic and antibacterial properties. Ahmed B, Ojha AK, Singh A, Hirsch F, Fischer I, Patrice D, Materny A. J Hazard Mater. 2018 Apr 5;347:266-278.

- The Bacillus subtilis yqgC-sodA operon protects magnesium-dependent enzymes by supporting manganese efflux. Sachla AJ, Soni V, Piñeros M, Luo Y, Im JJ, Rhee KY, Helmann JD. J Bacteriol. 2024 Jun 20;206(6):e0005224.

- Insight Into Microbes and Plants Ability for Bioremediation of Heavy Metals. Vaid N, Sudan J, Dave S, Mangla H, Pathak H. Curr Microbiol. 2022 Mar 23;79(5):141.

- Mineral surfaces and bioavailability of heavy metals: a molecular-scale perspective. Brown GE Jr, Foster AL, Ostergren JD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999 Mar 30;96(7):3388-95.

- Geophysical imaging of stimulated microbial biomineralization. Williams KH, Ntarlagiannis D, Slater LD, Dohnalkova A, Hubbard SS, Banfield JF. Environ Sci Technol. 2005 Oct 1;39(19):7592-600.

- Microbial Biofilms for Environmental Bioremediation of Heavy Metals: a Review. Syed Z, Sogani M, Rajvanshi J, Sonu K. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023 Sep;195(9):5693-5711.

- Microbial functionalities and immobilization of environmental lead: Biogeochemical and molecular mechanisms and implications for bioremediation. Elizabeth George S, Wan Y. J Hazard Mater. 2023 Sep 5;457:131738.

- Comparative studies on Pb(II) biosorption with three spongy microbe-based biosorbents: High performance, selectivity and application. Wang N, Qiu Y, Xiao T, Wang J, Chen Y, Xu X, Kang Z, Fan L, Yu H. J Hazard Mater. 2019 Jul 5;373:39-49.

- A New Strategy for Heavy Metal Polluted Environments: A Review of Microbial Biosorbents. Ayangbenro AS, Babalola OO. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 Jan 19;14(1):94.

- Heavy Metal Removal by Bioaccumulation Using Genetically Engineered Microorganisms. Diep P, Mahadevan R, Yakunin AF. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2018 Oct 29;6:157.

- Biosequestration, transformation, and volatilization of mercury by Lysinibacillus fusiformis isolated from industrial effluent. Gupta S, Goyal R, Nirwan J, Cameotra SS, Tejoprakash N. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012 May;22(5):684-9.

- Effects of various heavy metal nanoparticles on Enterococcus hirae and Escherichia coli growth and proton-coupled membrane transport. Vardanyan Z, Gevorkyan V, Ananyan M, Vardapetyan H, Trchounian A. J Nanobiotechnology. 2015 Oct 16;13:69.

- A review on mechanism of biomineralization using microbial-induced precipitation for immobilizing lead ions. Shan B, Hao R, Xu H, Li J, Li Y, Xu X, Zhang J. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Jun;28(24):30486-30498.

- Engineering of a synthetic electron conduit in living cells. Jensen HM, Albers AE, Malley KR, Londer YY, Cohen BE, Helms BA, Weigele P, Groves JT, Ajo-Franklin CM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010 Nov 9;107(45):19213-8.

- Mechanisms of Bacterial Extracellular Electron Exchange.White GF, Edwards MJ, Gomez-Perez L, Richardson DJ, Butt JN, Clarke TA. Adv Microb Physiol. 2016;68:87-138.

- Microbial remediation mechanisms and applications for lead-contaminated environments. Shan B, Hao R, Zhang J, Li J, Ye Y, Lu A. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022 Dec 13;39(2):38.

- Bacterial toxin-antitoxin systems: Novel insights on toxin activation across populations and experimental shortcomings. Pizzolato-Cezar LR, Spira B, Machini MT. Curr Res Microb Sci. 2023 Oct 6;5:100204.

- Microbial bioremediation as a robust process to mitigate pollutants of environmental concern. Bilal M, Iqbal HMN. Case Studies in Chemical and Environmental Engineering 2 (2020) 100011.

- New Trends in Bioremediation Technologies Toward Environment-Friendly Society: A Mini-Review. Dutta K, Shityakov S, Khalifa I. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2021 Aug 2;9:666858.

- Study on bioremediation of Lead by exopolysaccharide producing metallophilic bacterium isolated from extreme habitat. Kalita D, Joshi SR. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2017 Nov 8;16:48-57.

- Bioremediation of Pb contaminated water using a novel Bacillus sp. strain MHSD_36 isolated from Solanum nigrum. Maumela P, Magida S, Serepa-Dlamini MH. PLoS One. 2024 Apr 29;19(4):e0302460.

- Production of a metal-binding exopolysaccharide by Paenibacillus jamilae using two-phase olive-mill waste as fermentation substrate. Morillo JA, Aguilera M, Ramos-Cormenzana A, Monteoliva-Sánchez M. Curr Microbiol. 2006 Sep;53(3):189-93.

- Lead-resistant bacteria from Saint Clair River sediments and Pb removal in aqueous solutions. Bowman N, Patel D, Sanchez A, Xu W, Alsaffar A, Tiquia-Arashiro SM. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2018 Mar;102(5):2391-2398.

- Novel nanohybrids of silver particles on clay platelets for inhibiting silver-resistant bacteria. Su HL, Lin SH, Wei JC, Pao IC, Chiao SH, Huang CC, Lin SZ, Lin JJ. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e21125.

- Removal of heavy metals from mine tailings by in-situ bioleaching coupled to electrokinetics. Acosta Hernández I, Muñoz Morales M, Fernández Morales FJ, Rodríguez Romero L, Villaseñor Camacho J. Environ Res. 2023 Dec 1;238(Pt 2):117183.

- Thermoacidophilic Bioleaching of Industrial Metallic Steel Waste Product. Kölbl D, Memic A, Schnideritsch H, Wohlmuth D, Klösch G, Albu M, Giester G, Bujdoš M, Milojevic T. Front Microbiol. 2022 Apr 13;13:864411.

- Microbial functionalities and immobilization of environmental lead: Biogeochemical and molecular mechanisms and implications for bioremediation. Elizabeth George S, Wan Y. J Hazard Mater. 2023 Sep 5;457:131738.

- Designed bacteria based on natural pbr operons for detecting and detoxifying environmental lead: A mini-review. Hui CY, Ma BC, Wang YQ, Yang XQ, Cai JM. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2023 Nov 15;267:115662.

- Biosorption: current perspectives on concept, definition and application. Fomina M, Gadd GM. Bioresour Technol. 2014 May;160:3-14.

- Comparative metatranscriptomics reveals widespread community responses during phenanthrene degradation in soil. de Menezes A, Clipson N, Doyle E. Environ Microbiol. 2012 Sep;14(9):2577-88.

- Understanding and Designing the Strategies for the Microbe-Mediated Remediation of Environmental Contaminants Using Omics Approaches. Malla MA, Dubey A, Yadav S, Kumar A, Hashem A, Abd Allah EF. Front Microbiol. 2018 Jun 4;9:1132.

- Fungal biosorption--an alternative to meet the challenges of heavy metal pollution in aqueous solutions. Dhankhar R, Hooda A. Environ Technol. 2011 Apr;32(5-6):467-91.

- Isolation of lead-resistant Arthrobactor strain GQ-9 and its biosorption mechanism. Wang T, Yao J, Yuan Z, Zhao Y, Wang F, Chen H. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2018 Feb;25(4):3527-3538.

- Biosorption of lead ion by lactic acid bacteria and the application in wastewater. Liu G, Geng W, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Chen H, Li M, Cao Y. Arch Microbiol. 2023 Dec 12;206(1):18.

- Efflux-mediated heavy metal resistance in prokaryotes. Nies DH. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2003 Jun;27(2-3):313-39.

- Alkaline pH homeostasis in bacteria: new insights. Padan E, Bibi E, Ito M, Krulwich TA. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005 Nov 30;1717(2):67-88. Characterization of siderophore-producing microorganisms associated to plants from high-Andean heavy metal polluted soil from Callejon de Huaylas (Ancash, Peru).

- Tamariz-Angeles C, Huamán GD, Palacios-Robles E, Olivera-Gonzales P, Castañeda-Barreto A. Microbiol Res. 2021 Sep;250:126811.

- Biosorption of lead(II) from aqueous solution by lactic acid bacteria. Dai QH, Bian XY, Li R, Jiang CB, Ge JM, Li BL, Ou J. Water Sci Technol. 2019 Feb;79(4):627-634.

- Characterization of a multi-metal binding biosorbent: Chemical modification and desorption studies. Abdolali A, Ngo HH, Guo W, Zhou JL, Du B, Wei Q, Wang XC, Nguyen PD. Bioresour Technol. 2015 Oct;193:477-87.

- The research progress in mechanism and influence of biosorption between lactic acid bacteria and Pb(II): A review. Lin D, Ji R, Wang D, Xiao M, Zhao J, Zou J, Li Y, Qin T, Xing B, Chen Y, Liu P, Wu Z, Wang L, Zhang Q, Chen H, Qin W, Wu D, Liu Y, Liu Y, Li S. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2019;59(3):395-410.

- In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus KLDS1.0207 for the Alleviative Effect on Lead Toxicity. Li B, Jin D, Yu S, Etareri Evivie S, Muhammad Z, Huo G, Liu F. Nutrients. 2017 Aug 8;9(8):845.

- Assessment of resistance and biosorption ability of Lactobacillus paracasei to remove lead and cadmium from aqueous solution. Afraz V, Younesi H, Bolandi M, Hadiani MR. Water Environ Res. 2021 Sep;93(9):1589-1599.

- Combining strains of lactic acid bacteria may reduce their toxin and heavy metal removal efficiency from aqueous solution. Halttunen T, Collado MC, El-Nezami H, Meriluoto J, Salminen S. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008 Feb;46(2):160-5.

- Rapid removal of lead and cadmium from water by specific lactic acid bacteria. Halttunen T, Salminen S, Tahvonen R. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007 Feb 28;114(1):30-5.

- Characterization of a biofilm-forming, amylase-producing, and heavy-metal-bioremediating strain Micrococcus sp. BirBP01 isolated from oligotrophic subsurface lateritic soil. Pandit B, Moin A, Mondal A, Banik A, Alam M. Arch Microbiol. 2023 Oct 8;205(11):351.

- Biosorption characteristic of Alcaligenes sp. BAPb.1 for removal of lead(II) from aqueous solution. Jin Y, Yu S, Teng C, Song T, Dong L, Liang J, Bai X, Xu X, Qu J. Biotech. 2017 Jun;7(2):123.

- Removal of mercury(II), lead(II) and cadmium(II) from aqueous solutions using Rhodobacter sphaeroides SC01. Su YQ, Zhao YJ, Zhang WJ, Chen GC, Qin H, Qiao DR, Chen YE, Cao Y. Chemosphere. 2020 Mar;243:125166.

- Bioremediation of Heavy Metals by the Genus Bacillus. Wróbel M, Śliwakowski W, Kowalczyk P, Kramkowski K, Dobrzyński J. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Mar 11;20(6):4964.

- Study on bioremediation of Lead by exopolysaccharide producing metallophilic bacterium isolated from extreme habitat. Kalita D, Joshi SR. Biotechnol Rep (Amst). 2017 Nov 8;16:48-57.

- Singly Flagellated Pseudomonas aeruginosa Chemotaxes Efficiently by Unbiased Motor Regulation. Cai Q, Li Z, Ouyang Q, Luo C, Gordon VD. mBio. 2016 Apr 5;7(2):e00013.

- In vitro and in vivo screening of bacterial species from contaminated soil for heavy metal biotransformation activity. Doolotkeldieva T, Bobusheva S, Konurbaeva M. J Environ Sci Health B. 2024;59(6):315-332.

- Serratiopeptidase: An integrated View of Multifaceted Therapeutic Enzyme. Nair SR, C SD. Biomolecules. 2022 Oct 13;12(10):1468.

- Study of synergistic effects induced by novel base composites on heavy metals removal and pathogen inactivation. Nisa ZU, Zulfiqar S, Fazal A, Sajid M, Khalid A, Mehmood Z, Othman SI, Abukhadra MR. Chemosphere. 2023 Nov;340:139718.

- Biosorption of cadmium, copper, lead and zinc by inactive biomass of Pseudomonas Putida. Pardo R, Herguedas M, Barrado E, Vega M. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2003 May;376(1):26-32.

- Electrochemical process for simultaneous removal of chemical and biological contaminants from drinking water. Hussain M, Syed Q, Bashir R, Adnan A. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Sep;28(33):45780-45792.

- Potential applications of extremophilic bacteria in the bioremediation of extreme environments contaminated with heavy metals. Sun J, He X, LE Y, Al-Tohamy R, Ali SS. J Environ Manage. 2024 Feb 14;352:120081.

- A concise review on wastewater treatment through microbial fuel cell: sustainable and holistic approach. Kunwar S, Pandey N, Bhatnagar P, Chadha G, Rawat N, Joshi NC, Tomar MS, Eyvaz M, Gururani P. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2024 Jan;31(5):6723-6737.

- Research progress on using biological cathodes in microbial fuel cells for the treatment of wastewater containing heavy metals. Wang H, Zhai P, Long X, Ma J, Li Y, Liu B, Xu Z. Front Microbiol. 2023 Sep 18;14:1270431.

- Microalgae-bacteria nexus for environmental remediation and renewable energy resources: Advances, mechanisms and biotechnological applications. Abate R, Oon YS, Oon YL, Bi Y. Heliyon. 2024 May 14;10(10):e31170.

- Overview of electroactive microorganisms and electron transfer mechanisms in microbial electrochemistry. Thapa BS, Kim T, Pandit S, Song YE, Afsharian YP, Rahimnejad M, Kim JR, Oh SE. Bioresour Technol. 2022 Mar;347:126579.

- A comprehensive review on bio-stimulation and bio-enhancement towards remediation of heavy metals degeneration. Nivetha N, Srivarshine B, Sowmya B, Rajendiran M, Saravanan P, Rajeshkannan R, Rajasimman M, Pham THT, Shanmugam V, Dragoi EN. Chemosphere. 2023 Jan;312(Pt 1):137099.

- Nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture: A double-edged sword. Shukla K, Mishra V, Singh J, Varshney V, Verma R, Srivastava S. J Sci Food Agric. 2024 Aug 15;104(10):5675-5688.

- Impact of nanomaterials on sustainable pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for biofuels production: An advanced approach. Srivastava N, Singh R, Srivastava M, Mohammad A, Harakeh S, Pratap Singh R, Pal DB, Haque S, Tayeb HH, Moulay M, Kumar Gupta V. Bioresour Technol. 2023 Feb;369:128471.

- Waste-to-Resource: New application of modified mine silicate waste to remove Pb2+ ion and methylene blue dye, adsorption properties, mechanism of action and recycling. Ghaedi S, Seifpanahi-Shabani K, Sillanpää M. Chemosphere. 2022 Apr;292:133412.

- Microbial Nanotechnology for Bioremediation of Industrial Wastewater. Mandeep, Shukla P.Front Microbiol. 2020 Nov 2;11:590631.

- Bacterial tolerance strategies against lead toxicity and their relevance in bioremediation application. Mitra A, Chatterjee S, Kataki S, Rastogi RP, Gupta DK.Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2021 Mar;28(12):14271-14284.

- Metal leaching from plastics in the marine environment: An ignored role of biofilm. Peng G, Pu Z, Chen F, Xu H, Cao X, Chun Chen C, Wang J, Liao Y, Zhu X, Pan K. Environ Int. 2023 Jul;177:107988.

- Investigation of the performance of the combined moving bed bioreactor-membrane bioreactor (MBBR-MBR) for textile wastewater treatment. Uddin M, Islam MK, Dev S. Heliyon. 2024 May 16;10(10):e31358.

- Significance of microbial genome in environmental remediation. Kugarajah V, Nisha KN, Jayakumar R, Sahabudeen S, Ramakrishnan P, Mohamed SB. Microbiol Res. 2023 Jun;271:127360.

- Horizon scanning of potential environmental applications of terrestrial animals, fish, algae and microorganisms produced by genetic modification, including the use of new genomic techniques. Miklau M, Burn SJ, Eckerstorfer M, Dolezel M, Greiter A, Heissenberger A, Hörtenhuber S, Zollitsch W, Hagen K. Front Genome Ed. 2024 Jun 13;6:1376927.

- Advanced bioremediation by an amalgamation of nanotechnology and modern artificial intelligence for efficient restoration of crude petroleum oil-contaminated sites: a prospective study. Patowary R, Devi A, Mukherjee AK. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023 Jun;30(30):74459-74484.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).