Submitted:

27 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- (RQ1) How does altering the visual realism of a virtual environment affect brain activity?

- (RQ2) Are specific brain patterns associated with the subjective sense of presence in virtual environments?

2. Background and Related Works

- User experience and sense of presence: The evaluation of user experience in VR is a multifaceted area of research that spans various aspects, including ease of use, level of presence/immersion, engagement, and psychological impacts. Over the years, studies tried investigating and evaluating these areas to improve VR applications [26,27]. One of the important factors of user experience in an immersive environment is the sense of presence [28]. Users would expect the sense of presence as a basic functionality of these environments [23]. The stronger this sense of presence, the more likely participants are to behave similarly to how they would in a real-world setting.

- Categorization and definition of presence: Researchers have delineated and categorized presence in various manners, contingent upon individuals’ perceptions of a virtual experience [29]. As a simple definition, presence can be defined as a subjective feeling of being in the virtual experience [30]. As a more detailed description, Skarbez et al. [31] categorize presence in "being there", "non-mediation", and "other". The dimension of "non-mediation" encompasses conceptualizations of Presence within technological contexts. Here, presence is delineated as the perceptual illusion of transcending mediation or as the suspension of disbelief, leading users to immerse themselves in an alternate reality detached from the actual world [32,33]. The "other" category regards presence as the perception of the virtual world as if it were real [34]. Within an alternative structure, users’ experience of presence can be categorized in two fields: spatial presence and social presence [32,35]. Social presence mainly focuses on experiencing interpersonal connections in a virtual world. Spatial presence can be considered as the "presence of place" and refers to the perceptual illusion of non-mediation, i.e., the illusion of being in a place while experiencing the virtual world. In this way, social presence requires a multi-user virtual experience, but spatial presence can be experienced whenever a virtual environment exists.

- Evaluation of sense of presence: In order to assess presence in VR, one can consider realism as an influencing factor on the level of presence, as it is also considered in IPQ and previous studies [37,38,39]. In this way, comparing two distinguishable conditions with clear differences in the level of realism can lead to an acceptable interpretation of the results. Earlier studies categorized realism based on the level of the perceived image into physical, photorealism, and functional realism categories [40]. In a different approach, a two-dimensional categorization approach proposed by Goncalves et al. [41] considers user perception and proximity to real-world counterparts. The first dimension is subjective and correlates with how users perceive the virtual world, regardless of whether it is designed to be realistic or imaginary. Here, the coherency of the experience plays an important role. Users may accept an environment as perceptually realistic if the sequence of events in a virtual environment has a reasonable coherency [42]. In the second dimension, realism is regarded as an objective measure that can be compared with the expectation of real-world conditions. Slater et al. [39] considered realism as the combination of two components: illumination and geometry. Illumination realism is influenced by the precision of lightning including shadows, global illumination, and reflection. Geometrical realism is related to the similarity of virtual objects to real ones, including polygonal shape, texture, and material. Most of these studies used questionnaires to assess the influence of differentiation in the level of realism on the sense of presence. Although these questionnaires can provide a general overview of the level of presence, an in-depth understanding can be achieved using physiological measures [39]. In this study, we will focus solely on visual realism, without considering other types such as auditory realism.

- Subjective measurement of presence: Subjective measures involve self-reported information provided by users following a VR experience, typically gathered through questionnaires. These measures are relatively simple to implement and straightforward to analyze due to their questionnaire-based structure. Throughout the years, researchers have developed various questionnaires, such as IPQ and Witmer-Singer [43], to assess the sense of presence in VR. However, evaluating presence factors is challenging due to the subjective nature of it. The initial problem that raise due to the change in the environment of experiencing VR and answering the questions. This change can cause a break in presence (BIP) and negatively influences the general user experience [28,44]. In recent years, several studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of implementing questionnaires in VR to avoid BIP [13,23,45]. Schwind et al. [23] assessed the presence of in-VR and out-VR conditions after VR intervention. In their study, participants played a first-person shooter game in two design conditions: abstract and realistic. The results indicate a significant influence of virtual realism on the sense of presence using IPQ. In a more comprehensive study, Alexandrovsky et al. [45] conducted an expert survey followed by two user studies to compare user responses to user experience questionnaires in both in-VR and out-VR conditions. According to their expert survey, most of the researchers see the necessity of embedding questionnaires in VR but their user study indicated lower usability and higher physical demand compared to out-VR questionnaires. Although in these studies the majority of users preferred in-VR questionnaires over the out-VR ones, they did not find significant differences in the results of questionnaires. In addition, some studies reported inconsistency of the responses with the experiment conditions [12]. As an example, they reported different responses to the realism item of IPQ questionnaires without changing the virtual environment and just by changing the questionnaire user interface, from out-VR to in-VR [12,13]. These inconsistencies can push studies towards using different methods such as different sensory measurements to improve the reliability of the results.

- Objective measurement of presence: Utilizing physiological measurements as a tool for assessing presence in VR offers the potential for continuous, non-intrusive, and objective data capture [46,47]. Specifically, the integration of VR technology with objective physiological metrics, rather than solely relying on subjective assessments, is rapidly gaining traction as a valuable tool for guiding design choices in the initial stages of artificial environment projects [48,49] and for examining human/environment interactions. Additionally, there is a growing body of research exploring the utility and efficacy of VR-based therapy for psychiatric conditions [50,51]. Given the correlation between presence and certain brain activities, exploring the brain activity patterns associated with the sense of presence is crucial, which has been relatively understudied so far.

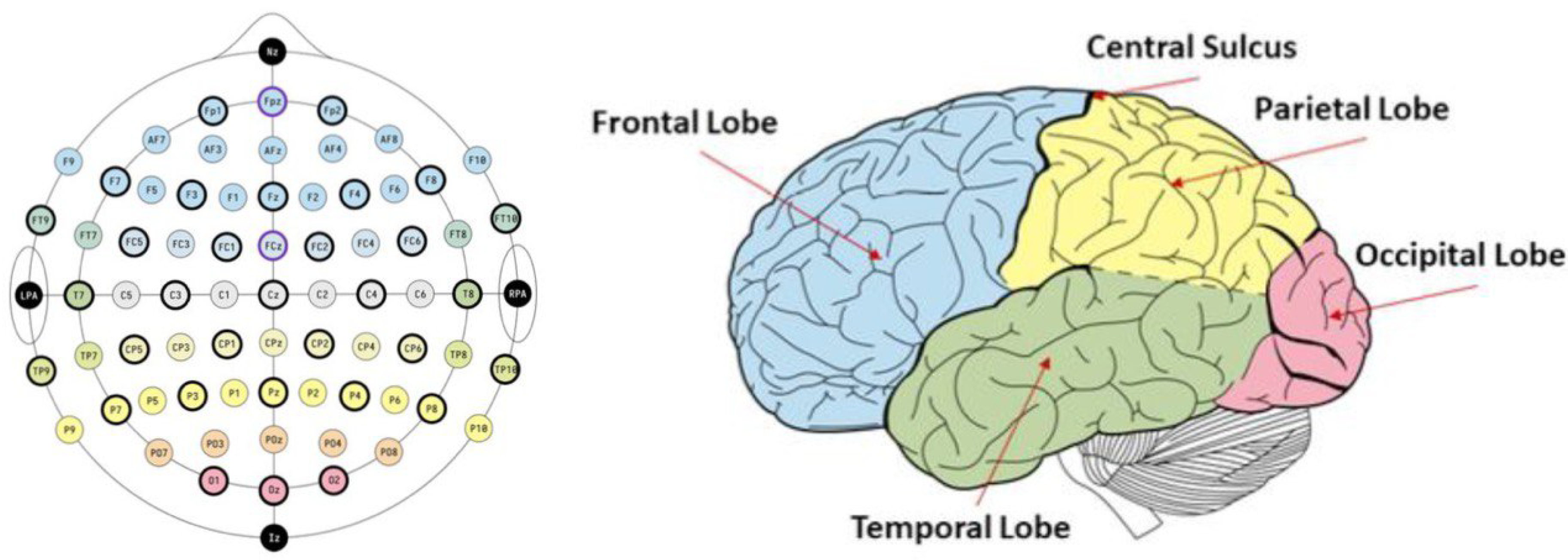

- EEG as an objective measurement tool: EEG waveforms are generally classified according to their frequency, amplitude, and shape, as well as the sites on the scalp at which they are recorded. The five most commonly used frequency bands and their corresponding frequency ranges are: delta (0.5-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (14-30 Hz), and gamma (> 30 Hz) [58,59]. Different mental states, like motivation, emotion, attention, and higher cognitive processes are strongly linked to brain waves in these different frequency bands [60,61,62,63,64]. Therefore, investigating frequency-specific changes in EEG data can lead to valuable insights in terms of how study participants process or respond to different stimuli.

- Functional meaning of the different EEG bands: EEG bandpower analysis in different brain regions provides insight into various cognitive and emotional states [62]. The four primary frequency bands (alpha, beta, gamma, and theta) are associated with distinct neural activities and functions, and their significance can vary depending on the brain region in which they are observed.

3. Methodology

3.1. VR Application

3.2. Material

3.3. Setup

3.4. Participants

3.5. Procedure

3.6. Signal Processing

3.6.1. Preprocessing

3.6.2. Feature Extraction

- Absolute Bandpower: The bandpower of the trials were calculated using the Matlab provided function bandpower() and cutoff frequencies of different frequency bands. This function gives the average bandpower of the entire trial of each ROI. The complete trial is determined by starting in one environment and collecting 6 coins there and is then terminated. The outliers of the calculated bandpower were removed when these outliers were located more than 3 scaled median absolute deviations from the median. The arithmetic means and the standard deviation of the absolute bandpower were displayed. For statistical analysis, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test with a significance level of 5% and 1% was used.

- Relative Bandpower: The participant-specific relative bandpower was then derived by dividing the HP-bandpower with the LP-bandpower while using the LP as a baseline. This method demonstrates greater stability, as it reduces the occurrence of the outliers and is able to show, whether the bandpower was increased or decreased in the HP trial relative to the LP trial. The relative bandpower were presented within the group HP-LP and LP-HP.

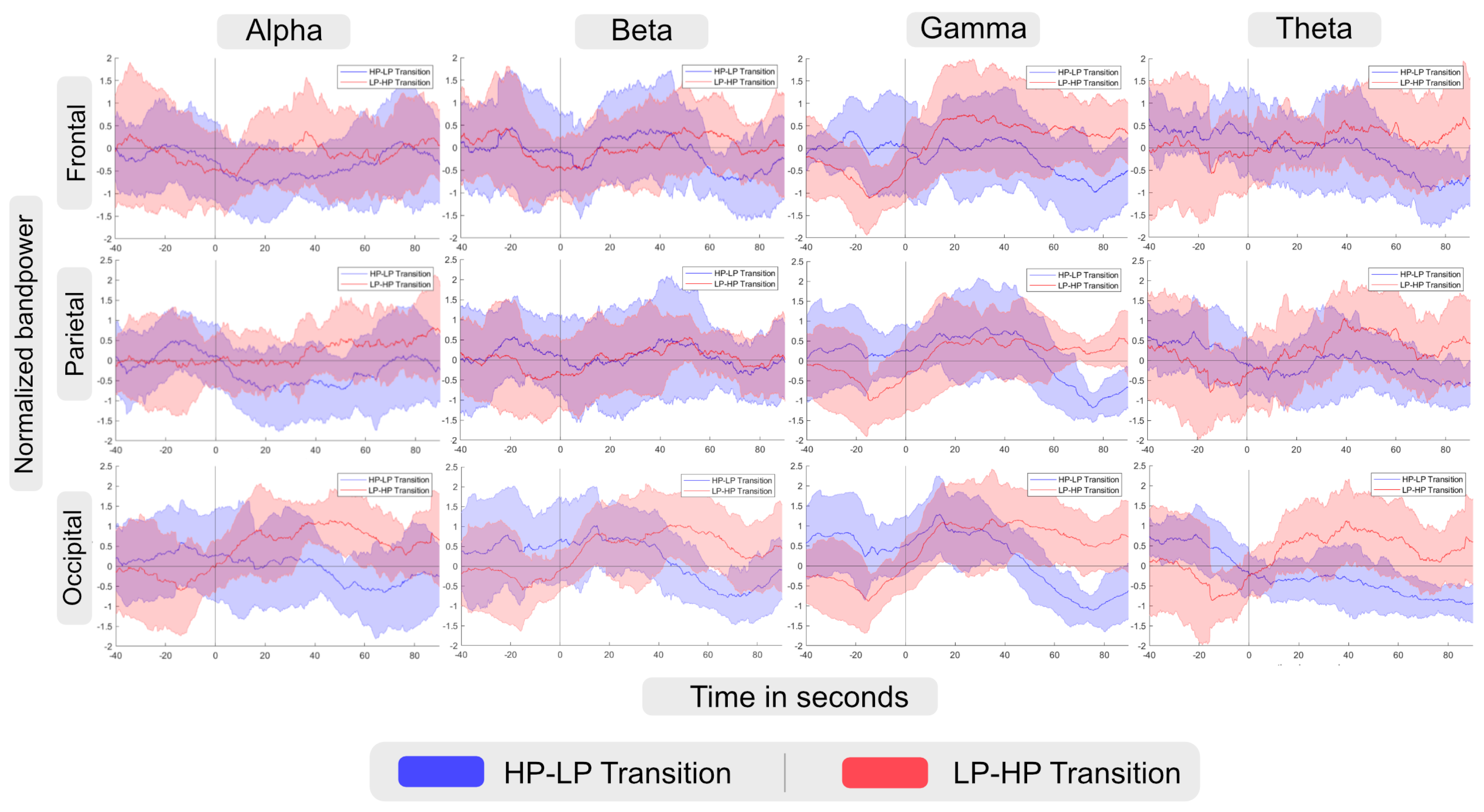

- Break Response: For displaying the bandpower activation over time and the neural responses due to the different environments the segmented HP and LP trials were concatenated accordingly (by the sequence of the polygon environments) and repositioned to ensure that the break was centered at the specific time point. Given the individual variations of the temporal parameters (recording time) concerning collecting 6 coins, the maximum duration of recording before and after the break was set at 3.3 minutes. The time-point of the break was defined as 0 seconds.

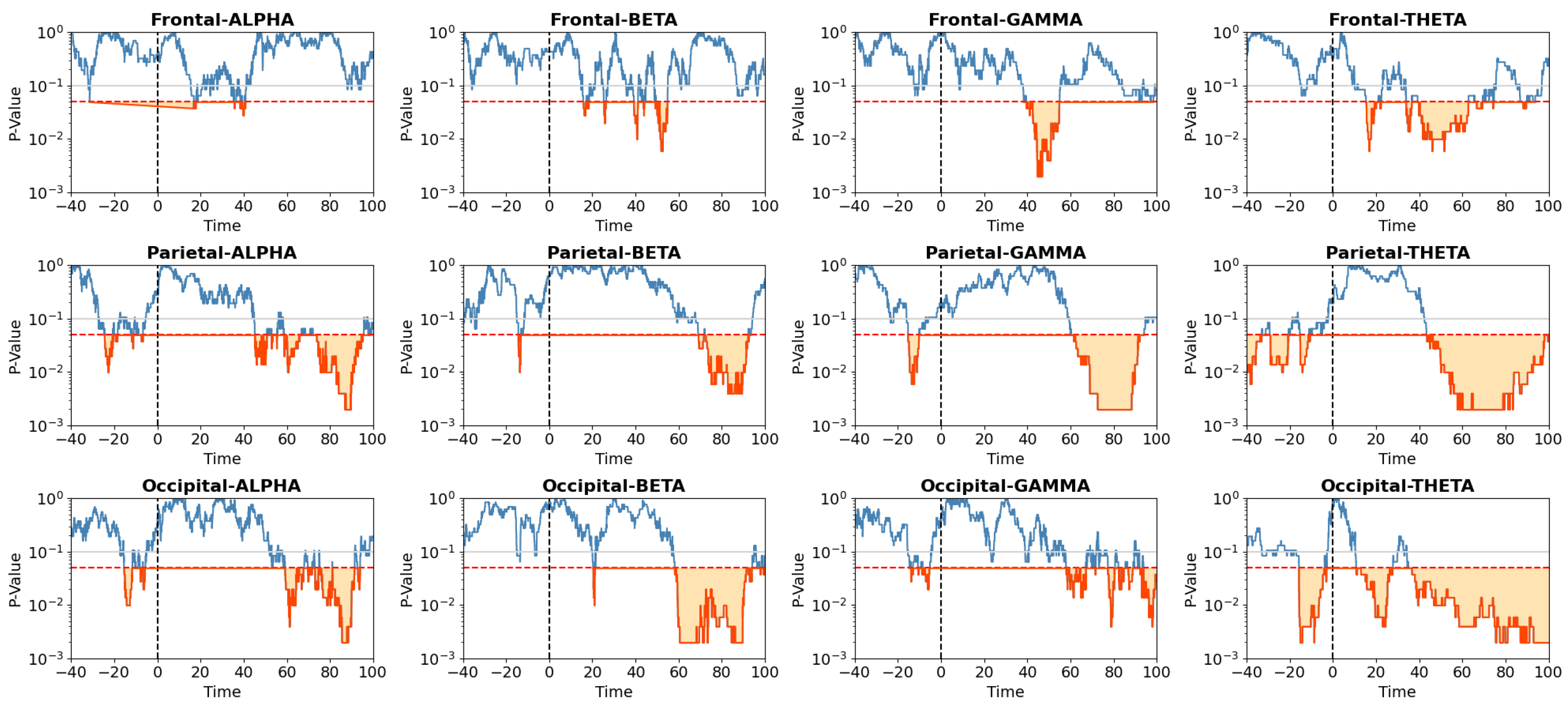

- Adaptation time: In this study, we defined the adaptation time (AT) as the time required to achieve the maximum value of the normalized bandpower within 100 seconds. For extracting the AT for adapting to the new environment, the EEG data were exactly processed like in the previous part (filtering, squaring, moving averaging, and normalizing) with the difference that the length of the moving average window was set to 60 seconds. The upper boundary of the AT with 100 seconds was chosen as Baka et al. [84] showed that the time period needed for the adaptation of the brain was at approximately 40 seconds. The comparison was then conducted with the LP trials of the LP-HP in the beginning state and with the LP-trials of the HP-LP trials after the break. For the statistical analyses, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used. Statistical significant results were indicated with stars (single star for alpha=5% and double star for alpha=1%), see Figure 7.

4. Results

4.1. EEG Measurement Results

- Adaptation Time: The statistical analysis conducted on AT for adapting to the new environment utilized the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. In this part of the analysis, we compared AT between groups at the time of experiencing the same environment. In this way, we can compare RT for the participant’s experience within the HP environment either as the first scene or the second one, see Figure 7. We ran the same comparison also for the LP environment, see Figure 7. The detailed analysis for these two figures is presented in Table A1, Table A2, Table A3, Table A4, Table A5 and Table A6 of the Appendices section. In these figures, blue bars denote AT for the group experiencing the LP/HP scene before the break, and red bars represent AT for the group experiencing the LP/HP scene after the break. According to this analysis, no significant differences in AT were observed before and after the break in any regions between groups when they were experiencing the HP condition, i.e. the first environment for the HP-LP group and the second environment for the LP-HP group. However, significant differences in AT were discerned for various Regions of Interest (ROIs) in the LP condition:

- (I) Alpha waves exhibited significant differences in the frontal (p=0.0067) and temporal lobes (p=0.038). (II) Beta waves displayed significant differences in the frontal-left (p=0.01), parietal (p=0.0378), and occipital lobes (p=0.007). (III) Gamma waves demonstrated significant differences in the occipital lobe (p=0.002). (IV) Theta waves revealed significant differences in the frontal (p=0.03), temporal (p=0.004), parietal-left (p=0.045), and occipital (p=0.001) lobes.

4.2. Questionnaires

- IPQ: The evaluation of sense of presence using IPQ shows no significant difference between the two groups in all items. Table 1 shows the mean/standard-deviation as well as p-value for each item of this questionnaire.

- NASA TLX: We found no significant difference between the two groups in all items except for a borderline condition of physical demand (p-value=0.056). According to these results, summarized in Table 2, participants experienced low-demanding tasks and found themselves successful in accomplishing the game quest.

5. Discussion

5.1. The Influence of Realism on Neural Activity

- Alpha band: According to the description provided in Section 2, an increase in alpha band power in the frontal lobe can be interpreted as a decrease in cognitive load. In the Alpha-Frontal subfigure of Figure 5, we can observe an increase in band power activity in both groups after changing the scene with a short delay. However, the LP-HP group experienced a faster increase in band power activity than the HP-LP group. In addition, considering Figure 6 we can also observe significant differences during the time period when LP-HP groups showed higher band power activity. As the second scene for LP-HP is the realistic scene and for HP-LP is the simplified one, we can conclude that a realistic scene may lead to a lower cognitive load compared to a simpler scene. It can be due to the point that the realistic scene is more compatible/similar to the environment that users are expected or used to see in real life.

- Beta band: In Section 2, we discussed that beta bandpower in the frontal lobe is associated with decision-making and cognitive process load. As the Beta-Frontal subfigure of Figure 5 shows, after switching scenes, with a short delay (less than 20 seconds), participants in the LP scene (for the HP-LP group) experience higher beta bandpower in the frontal lobe and after about 50 seconds this behavior happens for the other group. However, we only found significant differences in the time range when EEG results for the HP-LP group show higher beta bandpower. In this case, we can interpret that participants in the LP scene experience a higher decision-making and cognitive process load after switching the scene with a short delay.

- Gamma band: As a summary, gamma bandpower in the frontal lobe is known to be associated with enhanced executive functions, decision-making, and problem-solving, see Section 2. According to the Gamma-Frontal subfigure of Figure 5, participants who experienced the HP scene after the break, showed higher band power activity. Following that we assume the realistic condition might lead to improved executive function and problem-solving. Similarly, the gamma bandpower in parietal lobes shows a higher value after about 60 seconds, considering significant differences in Figure 6, in the HP scene after the break. Accordingly, we suppose a higher spatial awareness in this time period. In addition, since we observe higher gamma band power in the occipital lobes for the HP condition both before and after the break, we can interpret that the HP scene may lead to better visual information analysis and heightened visual attention.

- Theta band: The Theta-Frontal subfigure of Figure 5, shows the higher theta bandpower in participants who experienced HP scene after the break (we just found significant differences between groups after the break, see Figure 6). This result suggests that this group may have better working memory capabilities and superior cognitive control, allowing them to manage and manipulate information effectively over short periods. In addition, we also observe higher theta bandpower for the HP scene after the break, in particular after 40 seconds based on Figure 6, in parietal lobes that can be associated with higher integration of sensory information for HP condition compared to LP.

- (RQ1) How does altering the visual realism of a virtual environment affect the EEG-derived brain activity data?

- (RQ2) Are specific patterns of brain activation associated with the subjective sense of presence in virtual environments?

- Limitations: In our study, we discuss the influence of altering visual realism on brain activity using EEG results. However, previous research suggests that different types of realism can also have an impact on presence. To achieve these goals, additional features like animated objects or interactive characters can be added to the game. It should be considered, that these features need to be implemented with care, as any errors or inaccuracies in their design may negatively affect the sense of plausibility and presence.

- Future Works: We have shown how realism affects brain activity in different lobes of the brain. This information can be used to create research scenarios to explore the impact of specific activities in VR on the feeling of presence. For instance, researchers could examine how changes in presence occur during tasks such as solving puzzles, engaging in memory activities, or facing creative challenges in VR games.

6. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha aB | 40.2±33.5 | 42.0±33.0 | 35.7±33.4 | 47.1±35.0 | 48.2±33.8 | 58.7±23.9 | 51.8±33.0 | 46.4±33.7 | 56.6±31.1 | 40.0±28.7 |

| Alpha bB | 52.9±38.7 | 56.6±35.8 | 52.5±39.1 | 51.0±35.6 | 57.4±30.4 | 60.9±29.9 | 42.6±31.2 | 39.1±34.4 | 42.9±31.6 | 40.6±27.5 |

| Beta aB | 57.5±39.6 | 61.3±41.1 | 59.0±37.2 | 62.0±37.2 | 56.2±35.2 | 62.2±36.3 | 49.0±38.9 | 51.6±41.9 | 47.7±34.5 | 45.8±36.0 |

| Beta bB | 74.8±32.7 | 72.2±36.1 | 81.1±23.6 | 71.9±26.0 | 63.6±23.9 | 68.9±28.7 | 54.3±28.7 | 59.3±27.7 | 55.6±29.7 | 40.3±33.5 |

| Gamma aB | 40.7±37.1 | 46.0±43.0 | 44.4±38.0 | 48.1±40.3 | 49.7±43.5 | 57.0±32.2 | 43.3±43.0 | 49.3±46.7 | 46.2±41.4 | 48.3±33.2 |

| Gamma bB | 60.8±41.1 | 52.1±40.8 | 60.3±41.5 | 58.3±40.6 | 59.2±39.5 | 64.1±36.8 | 40.6±38.4 | 49.6±34.5 | 45.3±38.5 | 42.1±34.1 |

| Theta aB | 43.1±34.5 | 41.0±33.8 | 38.7±32.9 | 38.2±36.5 | 44.1±35.5 | 39.2±36.6 | 46.0±35.2 | 47.2±36.0 | 42.4±37.2 | 41.4±30.0 |

| Theta bB | 49.9±34.8 | 57.0±35.5 | 57.0±33.1 | 57.0±31.2 | 56.8±31.1 | 49.4±30.7 | 53.6±42.2 | 64.9±41.2 | 39.4±35.5 | 36.8±31.0 |

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha | 0.5974 | 0.2597 | 0.4181 | 0.7513 | 0.3787 | 0.7513 | 0.5035 | 0.8053 | 0.2751 | 0.9159 |

| Beta | 0.2178 | 0.5035 | 0.0980 | 0.5974 | 0.7513 | 0.6985 | 0.8603 | 0.8053 | 0.7513 | 0.6985 |

| Gamma | 0.2907 | 1.0000 | 0.3072 | 0.4384 | 0.6220 | 0.5973 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 0.9159 | 0.5974 |

| Theta | 0.5974 | 0.3072 | 0.1697 | 0.1925 | 0.3416 | 0.4179 | 0.3418 | 0.1487 | 0.8603 | 0.7513 |

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha z | 0.5 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.3 | -0.7 | -0.2 | -1.1 | 0.1 |

| Alpha U | 118 | 126.5 | 122 | 115 | 123 | 115 | 100 | 106 | 94 | 112 |

| Beta z | 1.2 | 0.7 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | -0.4 |

| Beta U | 128 | 120 | 134 | 118 | 115 | 116 | 113 | 114 | 115 | 104 |

| Gamma z | 1.1 | 0 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | -0.1 | -0.5 |

| Gamma U | 125.5 | 110 | 125 | 121.5 | 117.5 | 118 | 109.5 | 109.5 | 108 | 102 |

| Theta z | 0.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.2 | -0.3 |

| Theta U | 118 | 125 | 130 | 129 | 124 | 122 | 124 | 131 | 113 | 105 |

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha bB | 77.6±27.8 | 77.4±27.0 | 66.4±34.0 | 64.5±40.1 | 78.8±20.4 | 66.7±34.4 | 57.9±36.3 | 68.2±27.0 | 47.3±39.3 | 27.2±29.6 |

| Alpha aB | 27.5±34.9 | 30.5±34.3 | 41.8±43.6 | 37.8±39.7 | 39.2±38.2 | 39.7±41.0 | 40.6±35.9 | 40.0±34.8 | 44.8±38.1 | 47.0±30.6 |

| Beta bB | 77.0±25.4 | 79.9±21.5 | 83.6±21.8 | 75.6±21.0 | 78.4±19.2 | 69.7±25.5 | 64.6±32.2 | 72.5±28.5 | 58.8±36.4 | 30.8±32.0 |

| Beta aB | 54.3±38.1 | 49.7±36.3 | 40.7±38.7 | 47.0±39.9 | 49.7±36.5 | 53.0±41.1 | 36.4±34.6 | 45.6±34.6 | 49.1±37.9 | 66.3±20.5 |

| Gamma bB | 63.4±36.8 | 69.0±31.2 | 71.5±25.6 | 69.0±29.2 | 78.0±23.7 | 67.7±34.0 | 66.0±30.5 | 68.6±33.1 | 49.8±36.7 | 31.1±30.8 |

| Gamma aB | 61.5±31.9 | 64.4±33.3 | 67.7±34.8 | 59.7±39.9 | 65.0±33.5 | 64.5±37.6 | 84.7±14.0 | 76.7±29.7 | 80.1±23.4 | 79.6±15.2 |

| Theta bB | 42.7±32.7 | 38.7±34.4 | 35.6±32.2 | 38.8±27.2 | 53.8±28.6 | 40.1±35.4 | 47.4±34.9 | 48.8±34.1 | 38.3±36.1 | 27.5±24.6 |

| Theta aB | 69.2±26.5 | 72.6±26.9 | 68.7±26.2 | 77.5±29.0 | 70.2±27.7 | 72.7±27.3 | 61.3±39.9 | 77.0±28.9 | 54.3±38.4 | 72.9±23.0 |

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha | 0.0067 | 0.0092 | 0.1130 | 0.2450 | 0.0378 | 0.1589 | 0.3786 | 0.0844 | 0.9719 | 0.0725 |

| Beta | 0.1927 | 0.0317 | 0.0102 | 0.0980 | 0.0980 | 0.3787 | 0.0378 | 0.0725 | 0.5035 | 0.0067 |

| Gamma | 0.8053 | 0.5035 | 0.8603 | 0.5035 | 0.3787 | 0.5490 | 0.3418 | 0.9159 | 0.1489 | 0.0017 |

| Theta | 0.0620 | 0.0317 | 0.0151 | 0.0043 | 0.0980 | 0.0448 | 0.2453 | 0.0221 | 0.2751 | 0.0014 |

| Frontal | Frontal left |

Frontal right |

Temporal | Temporal left |

Temporal right |

Parietal | Parietal left |

Parietal right |

Occipital | |

| Alpha z | -2.711 | -2.606 | -1.585 | -1.163 | -2.077 | -1.409 | -0.881 | -1.726 | 0.035 | 1.796 |

| Alpha U | 71 | 72.5 | 87 | 93 | 80 | 89.5 | 97 | 85 | 111 | 136 |

| Beta z | -1.303 | -2.148 | -2.57 | -1.655 | -1.655 | -0.88 | -2.077 | -1.796 | -0.669 | 2.712 |

| Beta U | 91 | 79 | 73 | 86 | 86 | 97 | 80 | 84 | 100 | 149 |

| Gamma z | -0.246 | -0.669 | -0.176 | -0.669 | -0.88 | -0.599 | 0.951 | 0.106 | 1.444 | 3.135 |

| Gamma U | 106 | 100 | 107 | 100 | 97 | 101 | 124 | 112 | 131 | 155 |

| Theta z | 1.866 | 2.148 | 2.429 | 2.852 | 1.655 | 2.007 | 1.162 | 2.289 | 1.091 | 3.204 |

| Theta U | 137 | 141 | 145 | 151 | 134 | 139 | 127 | 143 | 126 | 156 |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 |

https://www.unrealengine.com/marketplace/en-US/product/ labstreaminglayer-plugin |

| 4 | "HP" denotes "High Polygons," while "LP" signifies "Low Polygons" |

| 5 | Brain Products GmbH, Gilching, Germany |

References

- Asad, M.M.; Naz, A.; Churi, P.; Tahanzadeh, M.M. Virtual reality as pedagogical tool to enhance experiential learning: a systematic literature review. Education Research International 2021, 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampropoulos, G.; Keramopoulos, E. Virtual Reality in Education: A Comparative Social Media Data and Sentiment Analysis Study. Int. J. Recent Contributions Eng. Sci. IT 2022, 10, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Im, T.; others. A systematic review of virtual reality-based education research using latent dirichlet allocation: Focus on topic modeling technique. Mobile Information Systems 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safikhani, S.; Pirker, J.; Wriessnegger, S.C. Virtual Reality Applications for the Treatment of Anxiety and Mental Disorders. 2021 7th International Conference of the Immersive Learning Research Network (iLRN). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–8.

- Banerjee, S.; Pham, T.; Eastaway, A.; Auffermann, W.F.; Quigley III, E.P. The use of virtual reality in teaching three-dimensional anatomy and pathology on CT. Journal of Digital Imaging 2023, 36, 1279–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safikhani, S.; Keller, S.; Schweiger, G.; Pirker, J. Immersive virtual reality for extending the potential of building information modeling in architecture, engineering, and construction sector: Systematic review. International Journal of Digital Earth 2022, 15, 503–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catbas, F.N.; Luleci, F.; Zakaria, M.; Bagci, U.; LaViola Jr, J.J.; Cruz-Neira, C.; Reiners, D. Extended reality (XR) for condition assessment of civil engineering structures: A literature review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putze, S.; Alexandrovsky, D.; Putze, F.; Höffner, S.; Smeddinck, J.D.; Malaka, R. Breaking the experience: effects of questionnaires in vr user studies. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schrepp, M.; Hinderks, A.; Thomaschewski, J. Design and evaluation of a short version of the user experience questionnaire (ueq-s). International Journal of Interactive Multimedia and Artificial Intelligence 2017, 4, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schubert, T.; Friedmann, F.; Regenbrecht, H. The experience of presence: Factor analytic insights. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 2001, 10, 266–281. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, H.L.; Cairns, P.; Hall, M. A practical approach to measuring user engagement with the refined user engagement scale (UES) and new UES short form. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2018, 112, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, S.; Schwind, V. Inconsistencies of presence questionnaires in virtual reality. Proceedings of the 26th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, 2020, pp. 1–3.

- Safikhani, S.; Holly, M.; Kainz, A.; Pirker, J. The influence of In-VR questionnaire design on the user experience. Proceedings of the 27th ACM Symposium on Virtual Reality Software and Technology, 2021, pp. 1–8.

- Slater, M. How colorful was your day? Why questionnaires cannot assess presence in virtual environments. Presence 2004, 13, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, K.; Wiederhold, B.K.; Wiederhold, M.D.; Riva, G. Panic and agoraphobia in a virtual world. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 2002, 5, 197–202. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, D.; Higgins, C. Secondary inputs for measuring user engagement in immersive VR education environments. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01586 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tremmel, C.; Herff, C.; Sato, T.; Rechowicz, K.; Yamani, Y.; Krusienski, D.J. Estimating cognitive workload in an interactive virtual reality environment using EEG. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2019, 13, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S.; Laumann, K.; de Martin Topranin, V.; Thorp, S. Evaluating the effect of multi-sensory stimulations on simulator sickness and sense of presence during HMD-mediated VR experience. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baus, O.; Bouchard, S. Exposure to an unpleasant odour increases the sense of presence in virtual reality. Virtual Reality 2017, 21, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witmer, B.G.; Singer, M.J. Measuring presence in virtual environments: A presence questionnaire. Presence 1998, 7, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riva, G.; Davide, F.; IJsselsteijn, W.A. Being there: The experience of presence in mediated environments. Being there: Concepts, effects and measurement of user presence in synthetic environments 2003, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Barfield, W.; Zeltzer, D.; Sheridan, T.; Slater, M. Presence and performance within virtual environments. In Virtual environments and advanced interface design; 1995; pp. 473–513.

- Schwind, V.; Knierim, P.; Haas, N.; Henze, N. Using presence questionnaires in virtual reality. Proceedings of the 2019 CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2019, pp. 1–12.

- Grassini, S.; Laumann, K.; Rasmussen Skogstad, M. The use of virtual reality alone does not promote training performance (but sense of presence does). Frontiers in psychology 2020, 11, 553693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, H.G.; Richards, T.; Coda, B.; Richards, A.; Sharar, S.R. The illusion of presence in immersive virtual reality during an fMRI brain scan. Cyberpsychology & behavior 2003, 6, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Mubarrat, S.T.; Opafunso, O.; Chowdhury, S.K. The Evaluation of User Experience and Functional Workload of a Physically Inter-active Virtual Reality System. Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting. SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2020, Vol. 64, pp. 2084–2086.

- Somrak, A.; Pogačnik, M.; Guna, J. Suitability and comparison of questionnaires assessing virtual reality-induced symptoms and effects and user experience in virtual environments. Sensors 2021, 21, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenz, M.; Brade, J.; Klimant, P.; Heyde, C.E.; Hammer, N. Age and gender effects on presence, user experience and usability in virtual environments–first insights. PloS one 2023, 18, e0283565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, M.; Gonçalves, G.; Bessa, M.; others. How much presence is enough? qualitative scales for interpreting the igroup presence questionnaire score. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 24675–24685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarbez, R.; Brooks, Jr, F.P.; Whitton, M.C. A survey of presence and related concepts. ACM computing surveys (CSUR) 2017, 50, 1–39. [CrossRef]

- Skarbez, R.; Neyret, S.; Brooks, F.P.; Slater, M.; Whitton, M.C. A psychophysical experiment regarding components of the plausibility illusion. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2017, 23, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, M.; Ditton, T. At the heart of it all: The concept of presence. Journal of computer-mediated communication 1997, 3, JCMC321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slater, M.; Usoh, M. Representations systems, perceptual position, and presence in immersive virtual environments. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 1993, 2, 221–233. [Google Scholar]

- Parola, M.; Johnson, S.; West, R. Turning presence inside-out: MetaNarratives. Electronic Imaging 2016, 28, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IJsselsteijn, W.A.; De Ridder, H.; Freeman, J.; Avons, S.E. Presence: concept, determinants, and measurement. Human vision and electronic imaging V. SPIE, 2000, Vol. 3959, pp. 520–529.

- Slater, M. Place illusion and plausibility can lead to realistic behaviour in immersive virtual environments. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2009, 364, 3549–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.; Gatersleben, B.; Wyles, K.; Ratcliffe, E. The use of virtual reality in environment experiences and the importance of realism. Journal of environmental psychology 2022, 79, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvass, J.; Larsen, O.; Vendelbo, K.; Nilsson, N.; Nordahl, R.; Serafin, S. Visual realism and presence in a virtual reality game. 2017 3DTV conference: The true vision-capture, Transmission and Display of 3D video (3DTV-CON). IEEE, 2017, pp. 1–4.

- Slater, M.; Khanna, P.; Mortensen, J.; Yu, I. Visual realism enhances realistic response in an immersive virtual environment. IEEE computer graphics and applications 2009, 29, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferwerda, J.A. Three varieties of realism in computer graphics. Human vision and electronic imaging viii. SPIE, 2003, Vol. 5007, pp. 290–297.

- Gonçalves, G.; Coelho, H.; Monteiro, P.; Melo, M.; Bessa, M. Systematic review of comparative studies of the impact of realism in immersive virtual experiences. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarbez, R.; Brooks, F.P.; Whitton, M.C. Immersion and coherence: Research agenda and early results. IEEE transactions on visualization and computer graphics 2020, 27, 3839–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witmer, B.G.; Jerome, C.J.; Singer, M.J. The factor structure of the presence questionnaire. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 2005, 14, 298–312. [Google Scholar]

- Slater, M.; Brogni, A.; Steed, A. Physiological responses to breaks in presence: A pilot study. Presence 2003: The 6th annual international workshop on presence. Citeseer, 2003, Vol. 157.

- Alexandrovsky, D.; Putze, S.; Bonfert, M.; Höffner, S.; Michelmann, P.; Wenig, D.; Malaka, R.; Smeddinck, J.D. Examining design choices of questionnaires in VR user studies. Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2020, pp. 1–21.

- Wriessnegger, S.C.; Autengruber, L.M.; Chacón, L.A.B.; Pirker, J.; Safikhani, S. The influence of visual representation factors on bio signals and its relation to Presence in Virtual Reality Environments. 2022 IEEE International Conference on Metrology for Extended Reality, Artificial Intelligence and Neural Engineering (MetroXRAINE). IEEE, 2022, pp. 199–204.

- Athif, M.; Rathnayake, B.L.K.; Nagahapitiya, S.D.B.S.; Samarasinghe, S.A.K.; Samaratunga, P.S.; Peiris, R.L.; De Silva, A.C. Using biosignals for objective measurement of presence in virtual reality environments. 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine & Biology Society (EMBC). IEEE, 2020, pp. 3035–3039.

- Aromaa, S.; Väänänen, K. Suitability of virtual prototypes to support human factors/ergonomics evaluation during the design. Applied ergonomics 2016, 56, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchiato, G.; Tieri, G.; Jelic, A.; De Matteis, F.; Maglione, A.G.; Babiloni, F. Electroencephalographic correlates of sensorimotor integration and embodiment during the appreciation of virtual architectural environments. Frontiers in psychology 2015, 6, 160641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohil, C.J.; Alicea, B.; Biocca, F.A. Virtual reality in neuroscience research and therapy. Nature reviews neuroscience 2011, 12, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rus-Calafell, M.; Garety, P.; Sason, E.; Craig, T.J.; Valmaggia, L.R. Virtual reality in the assessment and treatment of psychosis: a systematic review of its utility, acceptability and effectiveness. Psychological medicine 2018, 48, 362–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.; Avons, S.E.; Meddis, R.; Pearson, D.E.; IJsselsteijn, W. Using behavioral realism to estimate presence: A study of the utility of postural responses to motion stimuli. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 2000, 9, 149–164. [Google Scholar]

- Thorp, S.O.; Rimol, L.M.; Lervik, S.; Evensmoen, H.R.; Grassini, S. Comparative analysis of spatial ability in immersive and non-immersive virtual reality: the role of sense of presence, simulation sickness and cognitive load. Frontiers in Virtual Reality 2024, 5, 1343872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroux, L. Presence in video games: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of game design choices. Applied Ergonomics 2023, 107, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kober, S.E.; Kurzmann, J.; Neuper, C. Cortical correlate of spatial presence in 2D and 3D interactive virtual reality: an EEG study. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2012, 83, 365–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, C.G.; Fairclough, S.H. Use of auditory event-related potentials to measure immersion during a computer game. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 2015, 73, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkildsen, T.; Makransky, G. Measuring presence in video games: An investigation of the potential use of physiological measures as indicators of presence. International journal of human-computer studies 2019, 126, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teplan, M.; others. Fundamentals of EEG measurement. Measurement science review 2002, 2, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Niedermeyer, E.; da Silva, F.L. Electroencephalography: basic principles, clinical applications, and related fields; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and cognitive processes. In Time and the Brain; CRC Press, 2000; pp. 252–277.

- Klimesch, W. EEG alpha and theta oscillations reflect cognitive and memory performance: a review and analysis. Brain research reviews 1999, 29, 169–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.X. Where does EEG come from and what does it mean? Trends in neurosciences 2017, 40, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colgin, L.L. Mechanisms and functions of theta rhythms. Annual review of neuroscience 2013, 36, 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Başar, E.; Güntekin, B. A short review of alpha activity in cognitive processes and in cognitive impairment. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2012, 86, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassini, S.; Railo, H.; Valli, K.; Revonsuo, A.; Koivisto, M. Visual features and perceptual context modulate attention towards evolutionarily relevant threatening stimuli: Electrophysiological evidence. Emotion 2019, 19, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazanova, O.; Vernon, D. Interpreting EEG alpha activity. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2014, 44, 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Pfurtscheller, G. Induced oscillations in the alpha band: functional meaning. Epilepsia 2003, 44, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsche, H.; Kaplan, S.; Von Stein, A.; Filz, O. The possible meaning of the upper and lower alpha frequency ranges for cognitive and creative tasks. International journal of psychophysiology 1997, 26, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohaia, W.; Saurels, B.W.; Johnston, A.; Yarrow, K.; Arnold, D.H. Occipital alpha-band brain waves when the eyes are closed are shaped by ongoing visual processes. Scientific reports 2022, 12, 1194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrmann, C.S.; Strüber, D.; Helfrich, R.F.; Engel, A.K. EEG oscillations: from correlation to causality. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2016, 103, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Okamoto, E.; Nishimura, H.; Mizuno-Matsumoto, Y.; Ishii, R.; Ukai, S. Beta activities in EEG associated with emotional stress. International Journal of Intelligent Computing in Medical Sciences & Image Processing 2009, 3, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser, J.; Lutzenberger, W. Cortical oscillatory activity and the dynamics of auditory memory processing. Reviews in the Neurosciences 2005, 16, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herrmann, C.S.; Fründ, I.; Lenz, D. Human gamma-band activity: a review on cognitive and behavioral correlates and network models. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2010, 34, 981–992. [Google Scholar]

- Fell, J.; Axmacher, N.; Haupt, S. From alpha to gamma: electrophysiological correlates of meditation-related states of consciousness. Medical hypotheses 2010, 75, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balconi, M.; Lucchiari, C. Consciousness and arousal effects on emotional face processing as revealed by brain oscillations. A gamma band analysis. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2008, 67, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauseng, P.; Griesmayr, B.; Freunberger, R.; Klimesch, W. Control mechanisms in working memory: a possible function of EEG theta oscillations. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2010, 34, 1015–1022. [Google Scholar]

- Begus, K.; Bonawitz, E. The rhythm of learning: Theta oscillations as an index of active learning in infancy. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 2020, 45, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkedal, M.Y.; Rossi III, J.; Panksepp, J. Human brain EEG indices of emotions: delineating responses to affective vocalizations by measuring frontal theta event-related synchronization. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2011, 35, 1959–1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ninaus, M.; Kober, S.E.; Friedrich, E.V.; Dunwell, I.; De Freitas, S.; Arnab, S.; Ott, M.; Kravcik, M.; Lim, T.; Louchart, S.; others. Neurophysiological methods for monitoring brain activity in serious games and virtual environments: a review. International Journal of Technology Enhanced Learning 2014, 6, 78–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, M.; Ravaja, N. Increased oscillatory theta activation evoked by violent digital game events. Neuroscience letters 2008, 435, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, T.; Valko, L.; Esslen, M.; Jäncke, L. Neural correlate of spatial presence in an arousing and noninteractive virtual reality: an EEG and psychophysiology study. CyberPsychology & Behavior 2006, 9, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, T.; Speck, D.; Wettstein, D.; Masnari, O.; Beeli, G.; Jäncke, L. Feeling present in arousing virtual reality worlds: prefrontal brain regions differentially orchestrate presence experience in adults and children. Frontiers in human neuroscience 2008, 2, 279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayyad, E.; Sra, M.; Höllerer, T. Walking and teleportation in wide-area virtual reality experiences. 2020 IEEE international symposium on mixed and augmented reality (ISMAR). IEEE, 2020, pp. 608–617.

- Baka, E.; Stavroulia, K.E.; Magnenat-Thalmann, N.; Lanitis, A. An EEG-based evaluation for comparing the sense of presence between virtual and physical environments. In Proceedings of Computer Graphics International 2018; 2018; pp. 107–116.

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Student. The probable error of a mean. Biometrika 1908, pp. 1–25.

- Woolson, R.F. Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Wiley encyclopedia of clinical trials 2007, pp. 1–3.

- Klimesch, W.; Sauseng, P.; Hanslmayr, S. EEG alpha oscillations: the inhibition–timing hypothesis. Brain research reviews 2007, 53, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, N.R.; Croft, R.J.; Dominey, S.J.; Burgess, A.P.; Gruzelier, J.H. Paradox lost? Exploring the role of alpha oscillations during externally vs. internally directed attention and the implications for idling and inhibition hypotheses. International journal of psychophysiology 2003, 47, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Stein, A.; Chiang, C.; König, P. Top-down processing mediated by interareal synchronization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2000, 97, 14748–14753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palva, S.; Palva, J.M. New vistas for α-frequency band oscillations. Trends in neurosciences 2007, 30, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aftanas, L.I.; Golocheikine, S.A. Human anterior and frontal midline theta and lower alpha reflect emotionally positive state and internalized attention: high-resolution EEG investigation of meditation. Neuroscience letters 2001, 310, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jensen, O.; Kaiser, J.; Lachaux, J.P. Human gamma-frequency oscillations associated with attention and memory. Trends in neurosciences 2007, 30, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crone, N.E.; Sinai, A.; Korzeniewska, A. High-frequency gamma oscillations and human brain mapping with electrocorticography. Progress in brain research 2006, 159, 275–295. [Google Scholar]

| GP | SP | INV | REAL | |

| Mean/SD | ||||

| HP-LP | 5.00/0.94 | 4.70/0.61 | 4.65/0.73 | 2.83/0.61 |

| LP-HP | 5.00/1.7 | 4.44/0.82 | 4.23/0.76 | 3.05/0.74 |

| p-value | ||||

| 0.56 | 0.3 | 0.45 | 0.48 | |

| MD | PD | TD | Perf. | Eff. | Fru. | |

| Mean/SD | ||||||

| HP-LP | 19/11 | 10/5 | 14/16 | 11/16 | 27/26 | 21/20 |

| LP-HP | 22/21 | 22/22 | 9/6 | 11/14 | 21/21 | 12/11 |

| p-value | ||||||

| 0.5 | 0.06 | 0.14 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.12 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).