Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

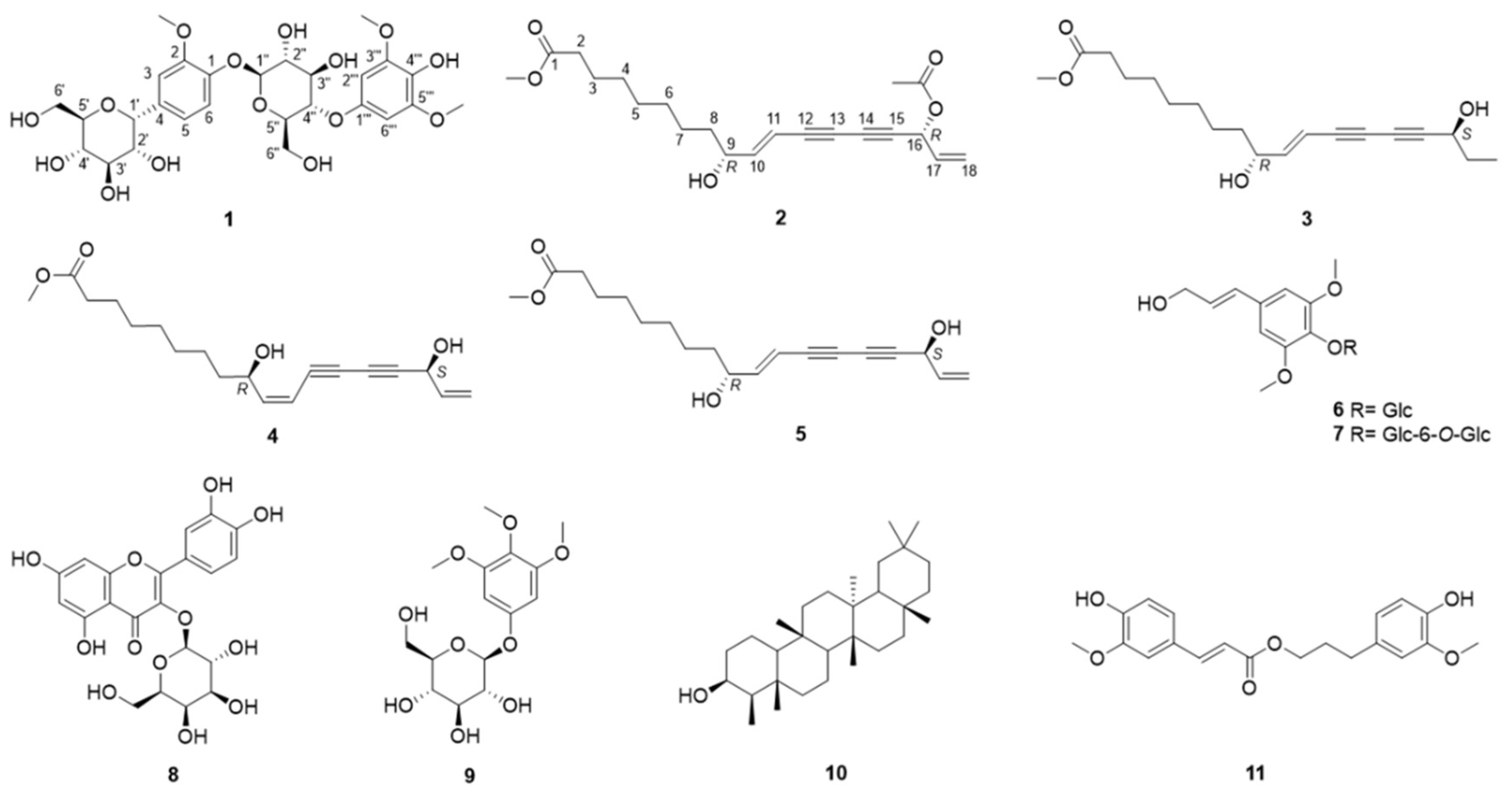

Dendropanax morbifera Leveille is a traditional medicine used to treat migraine headache and dysmenorrhea. In this study, a new phenolic glycoside, morbiferoside A (1), and three polyacetylenes, methyl (10E,9R,16R)-16-acetoxy-9-hydroxyoctadeca-10,17-dien-12,14-diynoate (2), methyl (10E,9R,16S)-9,16-dihydroxyoctadeca-10-en-12,14-diynoate (3), and methyl (10Z,9R,16S)-9,16-dihydroxyoctadeca-10,17-dien-12,14-diynoate (4), were isolated from the aerial parts of D. morbifera, together with seven known compounds (5–11). Importantly, the isolates, 7 and 9 were found in the family Araliaceae for the first time in this study. Compounds 1−11 were evaluated for their binding affinity to AMPK and CTSS receptors using in silico docking simulations. Only compound 8 increased the protein expression levels of PPAR-α, Sirt1, and AMPK when administered to HepG2 cells as a PPAR-α agonist. On the other hand, 8 did not produce any significant reduction in CTSS activity. This study could pave the way for the discovery of novel treatments from D. morbifera targeting PPAR-α and AMPK.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

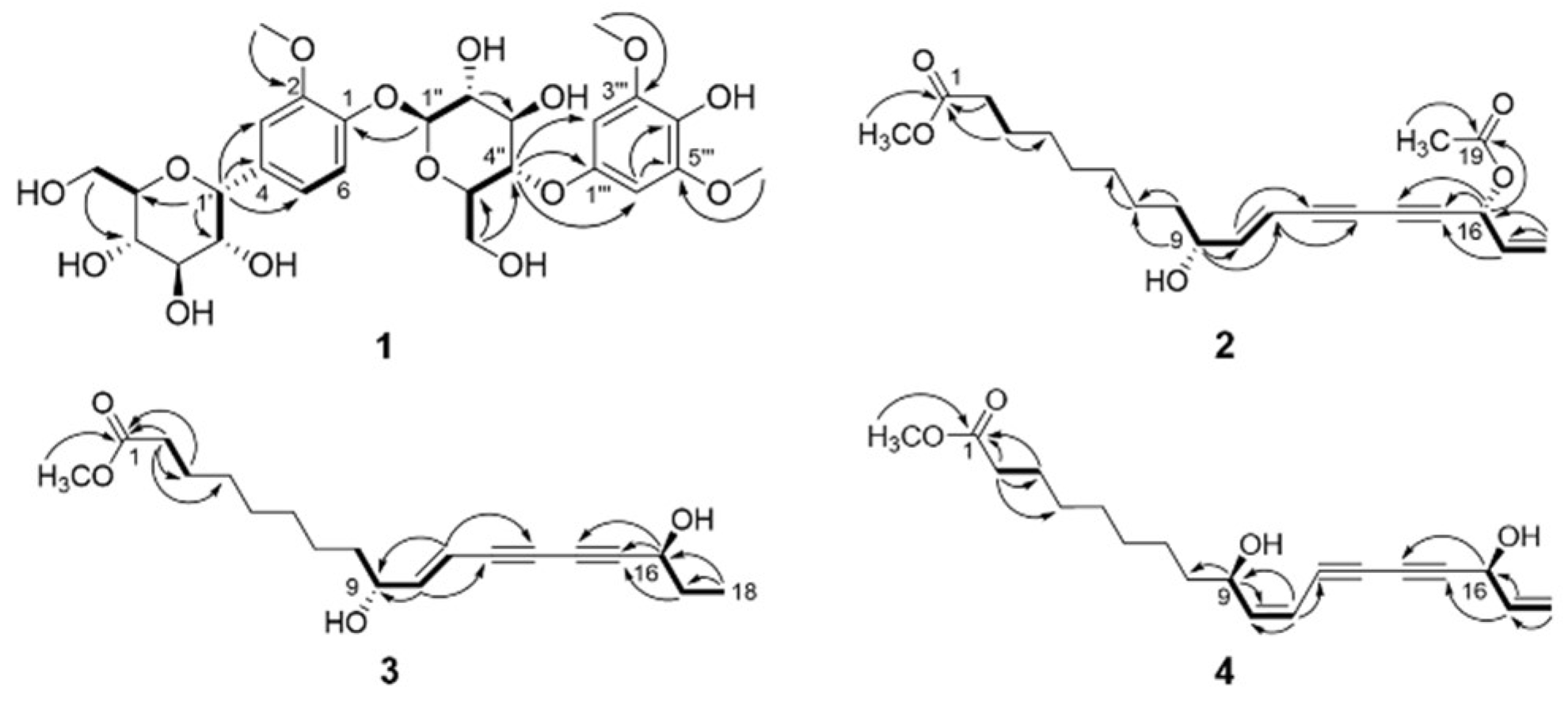

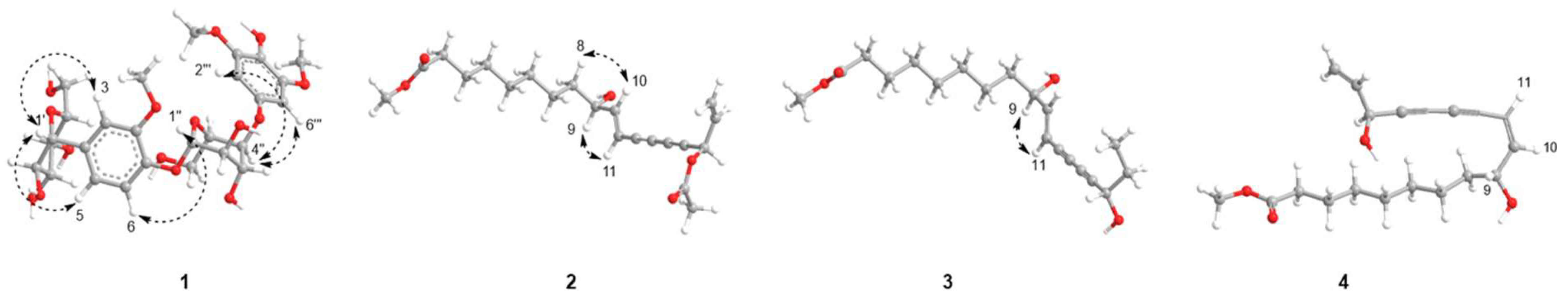

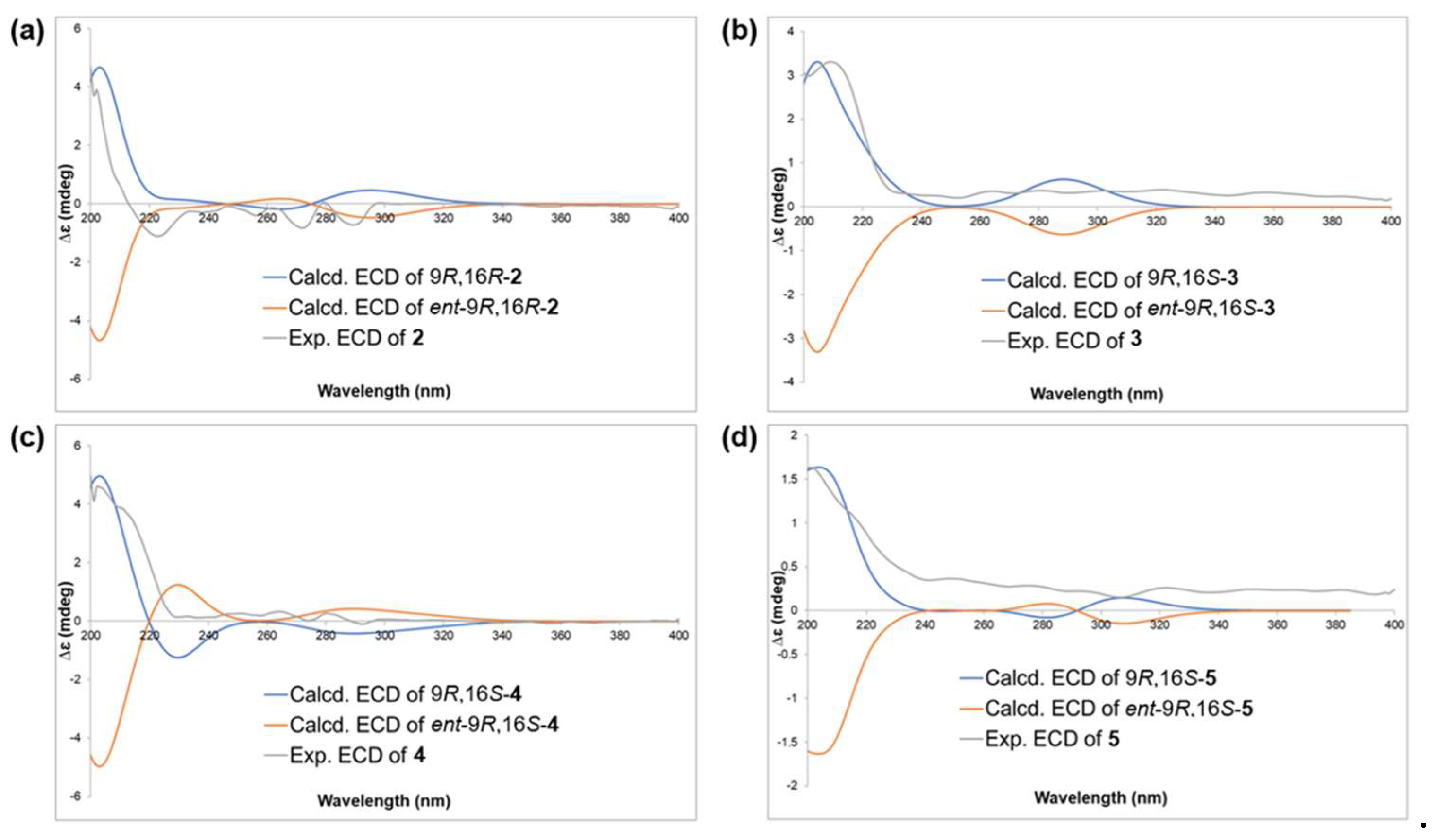

2.1. Structure Elucidation

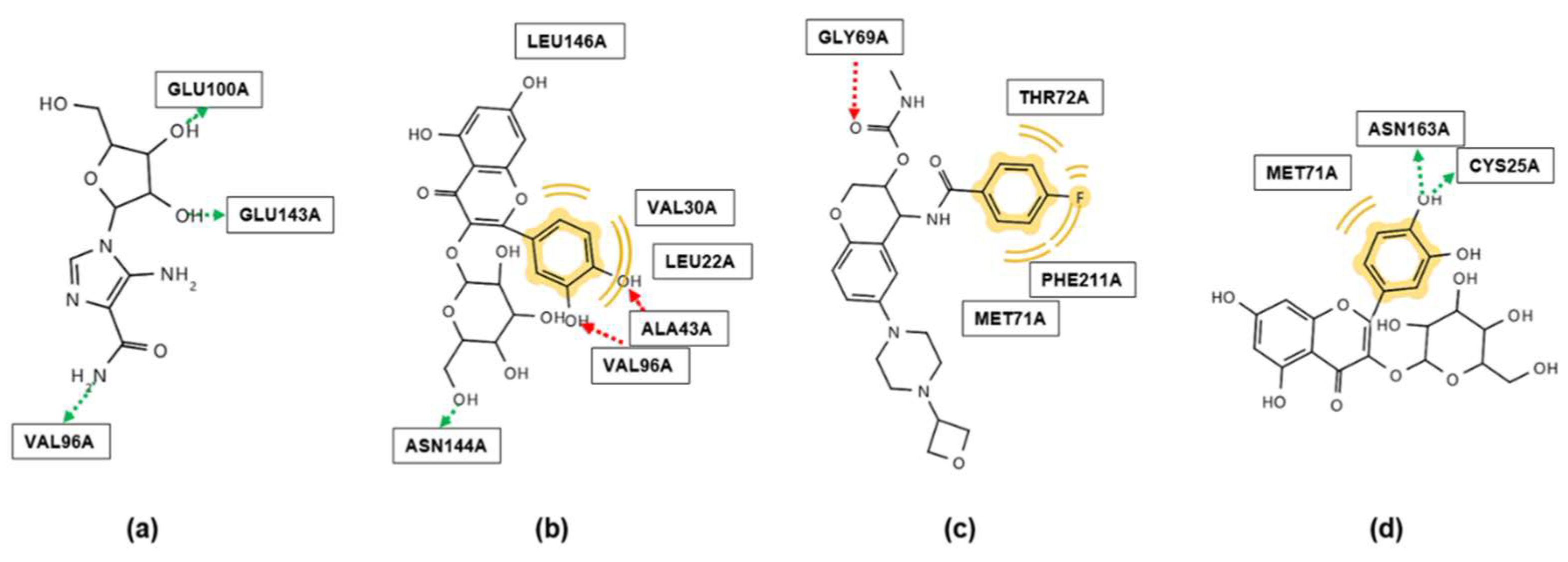

2.2. Molecular Docking

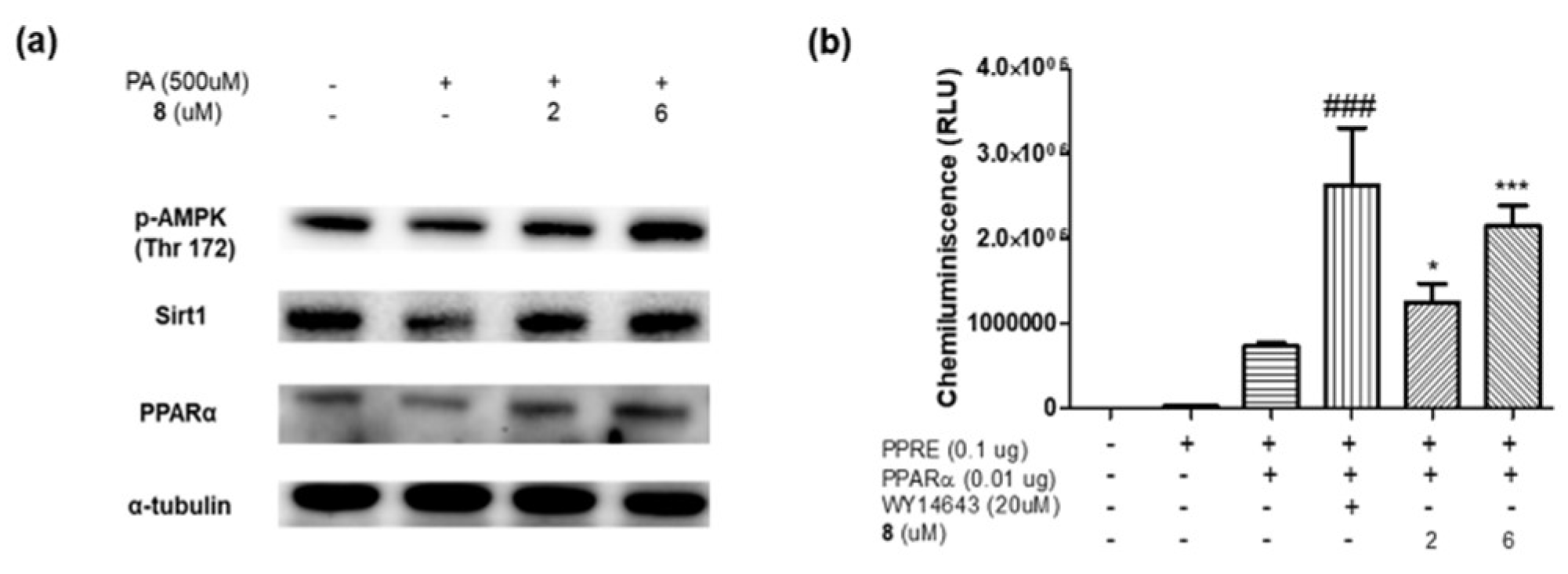

2.3. In Vitro Assay

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Plant Materials

3.2. General Experimental Procedures

3.3. Extraction and Isolation

Morbiferoside A (1)

Methyl (10E,9R,16R)-16-acetoxy-9-hydroxyoctadeca-10,17-dien-12,14-diynoate (2)

Methyl (10E,9R,16S)-9,16-dihydroxyoctadeca-10-en-12,14-diynoate (3)

Methyl (10Z,9R,16S)-9,16-dihydroxyoctadeca-10,17-dien-12,14-diynoate (4)

3.4. Conformational Search and DP4+ Calculation for 2–5

3.5. ECD Calculation

3.6. Molecular Docking

3.7. Cell Treatment Experiments

3.8. Protein Extraction and Western Blotting

3.9. Transfection and Luciferase Assay

3.10. CTSS Activity Assay

3.11. Reagents

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, S.H.; Jung, Y.H.; Oh, M.H.; Ko, M.H.; Oh, Y.S.; Koh, S.C.; Kim, M.H.; Oh, M.Y. Phytogenetic relationship of the Dendropanax morfera and D. trifidus based on PCR-RAPD. Korean J. Genet. 1998, 20, 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Awais, M.; Akter, R.; Boopathi, V.; Ahn, J.C.; Lee, J.H.; Mathiyalagan, R.; Kwak, G.-Y.; Rauf, M.; Yang, D.C.; Lee, G.S.; et al. Discrimination of Dendropanax morbifera via HPLC fingerprinting and SNP analysis and its impact on obesity by modulating adipogenesis- and thermogenesis-related genes. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1168095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, K. The medicinal plants of Korea; Kyo-Hak Publishing Company: Seoul, 2000; Volume 260. [Google Scholar]

- Heo, M.-G.; Byun, J.-H.; Kim, J.; Choung, S.-Y. Treatment of Dendropanax morbifera leaves extract improves diabetic phenotype and inhibits diabetes induced retinal degeneration in db/db mice. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 46, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Li, T.; Jin, L.; Piao, Z.H.; Liu, B.; Ryu, Y.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, G.R.; Jeong, J.E.; Wi, A.J.; et al. Dendropanax morbifera prevents cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by inhibiting the Sp1/GATA4 pathway. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2018, 46, 1021–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, Y.-C.; Liu, R.; Sun, H.-N.; Yun, B.-S.; Choi, H.S.; Lee, D.-S. Dihydroconiferyl ferulate isolated from Dendropanax morbiferus H.Lév. suppresses stemness of breast cancer cells via nuclear EGFR/c-Myc signaling. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-W.; Ryu, H.W.; Lee, S.U.; Son, T.H.; Park, H.A.; Kim, M.O.; Yuk, H.J.; Ahn, K.-S.; Oh, S.-R. Protective effect of polyacetylene from Dendropanax morbifera Leveille leaves on pulmonary inflammation induced by cigarette smoke and lipopolysaccharide. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 32, 358–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, R.; Cho, D.-Y.; Su-Kim, I.; Choi, D.-K. Dendropanax Morbiferus and other species from the genus dendropanax: Therapeutic potential of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacology. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, T. Phenylpropanoid biosynthesis. Mol. Plant. 2010, 3, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, A.A.; Andrade, L.N.; de Sousa É, B.; de Sousa, D.P. Antitumor phenylpropanoids found in essential oils. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 392674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkina, L.G. Phenylpropanoids as naturally occurring antioxidants: From plant defense to human health. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2007, 53, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Korkina, L.; Kostyuk, V.; De Luca, C.; Pastore, S. Plant phenylpropanoids as emerging anti-inflammatory agents. Mini-Rev. Med. Chem. 2011, 11, 823–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nabavi, S.M.; Šamec, D.; Tomczyk, M.; Milella, L.; Russo, D.; Habtemariam, S.; Suntar, I.; Rastrelli, L.; Daglia, M.; Xiao, J.; et al. Flavonoid biosynthetic pathways in plants: Versatile targets for metabolic engineering. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020, 38, 107316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajasekar, M.; Bhuvanesh, P.; Varada, P.; Selvam, M. Review on anticancer activity of flavonoid derivatives: Recent developments and future perspectives. Results Chem. 2023, 6, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciumărnean, L.; Milaciu, M.V.; Runcan, O.; Vesa Ș, C.; Răchișan, A.L.; Negrean, V.; Perné, M.G.; Donca, V.I.; Alexescu, T.G.; Para, I.; et al. The effects of flavonoids in cardiovascular diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 4320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouveia, H.; Urquiza-Martínez, M.V.; Manhães-de-Castro, R.; Costa-de-Santana, B.J.R.; Villarreal, J.P.; Mercado-Camargo, R.; Torner, L.; de Souza Aquino, J.; Toscano, A.E.; Guzmán-Quevedo, O. Effects of the treatment with flavonoids on metabolic syndrome components in humans: A systematic review focusing on mechanisms of action. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minto, R.E.; Blacklock, B.J. Biosynthesis and function of polyacetylenes and allied natural products. Prog. Lipid. Res. 2008, 47, 233–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P. Biological activities of naturally occurring acetylenes and related compounds from higher plants; Trivandrum, India: 1998; Volume 2, pp. 227-257.

- Santos, J.A.M.; Santos, C.; Freitas Filho, J.R.; Menezes, P.H.; Freitas, J.C.R. Polyacetylene glycosides: Isolation, biological activities and synthesis. Chem. Rec. 2022, 22, e202100176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, L.P.; Brandt, K. Bioactive polyacetylenes in food plants of the Apiaceae family: Occurrence, bioactivity and analysis. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2006, 41, 683–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saklayen, M.G. The global epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2018, 20, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Eckel, R.H. Pharmacological treatment and therapeutic perspectives of metabolic syndrome. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2014, 15, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diradourian, C.; Girard, J.; Pégorier, J.-P. Phosphorylation of PPARs: From molecular characterization to physiological relevance. Biochimie 2005, 87, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, M. The role of PPARα in lipid metabolism and obesity: Focusing on the effects of estrogen on PPARα actions. Pharmacol. Res. 2009, 60, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Towler, M.C.; Hardie, D.G. AMP-activated protein kinase in metabolic control and insulin signaling. Circ. Res. 2007, 100, 328–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Mao, X.; Du, M. Phytanic acid activates PPARα to promote beige adipogenic differentiation of preadipocytes. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 67, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, D.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, Y.H.; Noh, J.R.; Kim, D.K.; Park, J.H.; Hwang, J.H.; Lee, M.R.; Jeong, K.H.; Lee, I.K.; et al. Fenofibrate differentially regulates plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene expression via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase-dependent induction of orphan nuclear receptor small heterodimer partner. Hepatology 2009, 50, 880–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Zhang, B.; Moses, M.A. Making the cut: Protease-mediated regulation of angiogenesis. Exp. Cell Res. 2006, 312, 608–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilkinson, R.D.A.; Williams, R.; Scott, C.J.; Burden, R.E. Cathepsin S: Therapeutic, diagnostic, and prognostic potential. Biol. Chem. 2015, 396, 867–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsing, L.C.; Kirk, E.A.; McMillen, T.S.; Hsiao, S.H.; Caldwell, M.; Houston, B.; Rudensky, A.Y.; LeBoeuf, R.C. Roles for cathepsins S, L, and B in insulitis and diabetes in the NOD mouse. J. Autoimmun. 2010, 34, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taleb, S.; Lacasa, D.; Bastard, J.P.; Poitou, C.; Cancello, R.; Pelloux, V.; Viguerie, N.; Benis, A.; Zucker, J.D.; Bouillot, J.L.; et al. Cathepsin S, a novel biomarker of adiposity: Relevance to atherogenesis. FASEB J. 2005, 19, 1540–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhuang, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Ran, T.; He, J.; Han, N.; Duan, J. Cathepsin S inhibitor reduces high-fat-induced adipogenesis, inflammatory infiltration, and hepatic lipid accumulation in obese mice. Ann. Transl. Med. 2022, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, N.; Meta, M.; Schuppan, D.; Nuhn, L.; Schirmeister, T. Novel opportunities for Cathepsin S inhibitors in cancer immunotherapy by nanocarrier-mediated delivery. Cells 2020, 9, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Jiang, H.; Cheng, X.W. Cathepsin S are involved in human carotid atherosclerotic disease progression, mainly by mediating phagosomes: Bioinformatics and in vivo and vitro experiments. PeerJ 2022, 10, e12846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) α/γ agonist. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2014, 87, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junco, J.J.; Cho, J.; Mancha, A.; Malik, G.; Wei, S.J.; Kim, D.J.; Liang, H.; DiGiovanni, J.; Slaga, T.J. Role of AMPK and PPARα in the anti-skin cancer effects of ursolic acid. Mol. Carcinog. 2018, 57, 1698–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.U.; Yang, S.Y.; Guo, R.H.; Li, H.X.; Kim, Y.H.; Kim, Y.R. Anti-melanogenic effect of Dendropanax morbiferus and its active components via protein kinase A/cyclic adenosine monophosphate-responsive binding protein- and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-mediated microphthalmia−associated transcription dactor downregulation. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 507. [Google Scholar]

- Niwa, M.; Iwadare, Y.; Wu, Y.-C.; Hirata, Y. Two new phenylpropanoid glycosides from Wikstroemia sikokiana. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 1158–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, L.Y.; Lu, Y.; Molan, A.L.; Woodfield, D.R.; McNabb, W.C. The phenols and prodelphinidins of white clover flowers. Phytochemistry 2000, 54, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achenbach, H.; Benirschke, G. Joannesialactone and other compounds from Joannesia princeps. Phytochemistry 1997, 45, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kiem, P.; Van Minh, C.; Huong, H.T.; Nam, N.H.; Lee, J.J.; Kim, Y.H. Pentacyclic triterpenoids from Mallotus apelta. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2004, 27, 1109–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.Z.; Hano, Y.; Nomura, T.; Chen, Y.J. Alkaloids and phenylpropanoids from Peganum nigellastrum. Phytochemistry 2000, 53, 1075–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, L.; Haque, M.A.; Harikrishnan, H.; Ibrahim, S.; Jantan, I. Syringin from Tinospora crispa downregulates pro-inflammatory mediator production through MyD88-dependent pathways in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced U937 macrophages. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2024, 51, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aventurado, A.C.; Castillo, L.A.; Vasquez, D.R. Syringin as TGF-βR1, HER2, EGFR, FGFR4 kinase, and MMP-2 inhibitor and potential cytotoxic agent against ER+ breast cancer cells. Curr. Enzyme Inhib. 2023, 19, 55–64. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, V.K.; Thakur, D.C.; Rajak, N.; Giri, R.; Garg, N. Immunomodulatory potential of bioactive glycoside syringin: A network pharmacology and molecular modeling approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2023, 42, 3906–3919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gohari, A.; Saeidnia, S.; Bayati-Moghadam, M.; Amin, G.; Hadjiakhoondi, A. Phytochemical and chemotaxonomic investigation of Stelleropsis iranica. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2009, 3, 3423–3427. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, N.; Ahmad, S.; Malik, A. Phenylpropanoid glycosides from Daphne oleoides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1999, 47, 114–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.-A.; Park, D.W.; Sohn, E.H.; Lee, S.R.; Kang, S.C. Hyperoside suppresses tumor necrosis factor α-mediated vascular inflammatory responses by downregulating mitogen-activated protein kinases and nuclear factor-κB signaling. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 294, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orzelska-Górka, J.; Szewczyk, K.; Gawrońska-Grzywacz, M.; Kędzierska, E.; Głowacka, E.; Herbet, M.; Dudka, J.; Biała, G. Monoaminergic system is implicated in the antidepressant-like effect of hyperoside and protocatechuic acid isolated from Impatiens glandulifera Royle in mice. Neurochem. Int. 2019, 128, 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Sun, F.; Feng, W.; Qiu, X.; Liu, Y.; Yang, B.; Chen, Y.; Xia, P. Hyperoside inhibits biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 1647–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.C.; Jin, Y.J.; Xue, X.; Li, J.; Xu, G.H. Chemical constituents from the bark of Betula platyphylla. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2023, 59, 190–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Kanchanapoom, T.; Sawangjaroen, N.; Hutadilok-Towatana, N. Antioxidant, antibacterial and antigiardial activities of Walsura robusta Roxb. Nat. Prod. Res. 2010, 24, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yun, X.; Yang, T.; Xu, T.; Shi, D.; Li, X. Epifriedelanol delays the aging of porcine oocytes matured in vitro. Toxicon 2023, 233, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kundu, J.K.; Rouf, A.S.S.; Nazmul Hossain, M.; Hasan, C.M.; Rashid, M.A. Antitumor activity of epifriedelanol from Vitis trifolia. Fitoterapia 2000, 71, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Msengwa, Z.; Rwegoshora, F.; Credo, D.; Mwesongo, J.; Mafuru, M.; Mabiki, F.; John Mwang’onde, B.; Mtambo, M.; Kusiluka, L.; Mdegela, R.; et al. Epifriedelanol is the key compound to antibacterial effects of extracts of Synadenium glaucescens (Pax) against medically important bacteria. Front. Trop. Dis. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.-Z.; Wu, H.-F.; Xu, X.-D.; Yang, J.-S. Two new flavone C-glycosides from Trollius ledebourii. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2011, 59, 1393–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Chen, C.; Sun, W.; Zang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, W.; Zeng, F.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, Q.; et al. Phenolic C-glycosides and aglycones from marine-derived Aspergillus sp. and their anti-inflammatory activities. J. Nat. Prod. 2019, 82, 1098–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslund, M.U.; Tähtinen, P.; Niemitz, M.; Sjöholm, R. Complete assignments of the 1H and 13C chemical shifts and JH-H coupling constants in NMR spectra of D-glucopyranose and all D-glucopyranosyl-d-glucopyranosides. Carbohydr. Res. 2008, 343, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimatu, E.; Ishikawa, T.; Kitajima, J. Aromatic compound glucosides, alkyl glucoside and glucide from the fruit of anise. Phytochemistry 2003, 63, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, B.; Park, E.-J.; Doan, T.-P.; Cho, H.-M.; An, J.-P.; Pham, T.-L.-G.; Pham, H.-T.-T.; Oh, W.-K. Heliciopsides A−E, unusual macrocyclic and phenolic glycosides from the leaves of Heliciopsis terminalis and their stimulation of glucose uptake. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.J.; Li, J.H.; Zhou, M.M.; Luo, J.; Jian, K.L.; Tian, X.M.; Xia, Y.Z.; Yang, L.; Luo, J.; Kong, L.Y. Toonasindiynes A-F, new polyacetylenes from Toona sinensis with cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory activities. Fitoterapia 2020, 146, 104667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.G.; Goodman, J.M. Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: The DP4 probability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 12946–12959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcarino, M.O.; Cicetti, S.; Zanardi, M.M.; Sarotti, A.M. A critical review on the use of DP4+ in the structural elucidation of natural products: The good, the bad and the ugly. A practical guide. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 58–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, I.-M.; Song, H.-K.; Kim, S.-J.; Moon, H.-I. Anticomplement activity of polyacetylenes from leaves of Dendropanax morbifera Leveille. Phytother. Res. 2011, 25, 784–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.-Y.; Min, B.-S.; Oh, S.-R.; Kim, J.-H.; Kim, T.-J.; Kim, D.-H.; Bae, K.-H.; Lee, H.-K. Isolation and anticomplement activity of compounds from Dendropanax morbifera. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 90, 403–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.H.; Jo, C.S.; Ryu, S.Y.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.Y. Anti-osteoclastogenic diacetylenic components of Dendropanax morbifera. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018, 41, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.-O.; Kang, M.-J.; Lee, S.-U.; Kim, D.-Y.; Jang, H.-J.; An, J.H.; Lee, H.-S.; Ryu, H.W.; Oh, S.-R. Polyacetylene (9Z,16S)-16-hydroxy-9,17-octadecadiene-12,14-diynoic acid in Dendropanax morbifera leaves. Food Biosci. 2021, 40, 100878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, T.Q.; Vu, N.K.; Woo, M.H.; Min, B.S. New polyacetylene and other compounds from Bupleurum chinense and their chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2020, 92, 104090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.C.; Yi, S.A.; Lee, B.S.; Yu, J.S.; Kim, J.-C.; Pang, C.; Jang, T.S.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.H. Anti-adipogenic polyacetylene glycosides from the florets of safflower (Carthamus tinctorius). Biomedicines 2021, 9, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.-S.; Qin, F.-Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y. Four new polyynes from Codonopsis pilosula collected in Yunnan province, China. Nat. Prod. Res. 2021, 35, 3548–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembitsky, V.M. Anticancer activity of natural and synthetic acetylenic lipids. Lipids 2006, 41, 883–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullins Alex, J.; Webster, G.; Kim Hak, J.; Zhao, J.; Petrova Yoana, D.; Ramming Christina, E.; Jenner, M.; Murray James, A.H.; Connor Thomas, R.; Hertweck, C.; et al. Discovery of the pseudomonas polyyne protegencin by a phylogeny-guided study of polyyne biosynthetic gene cluster diversity. mBio 2021, 12, e00715–00721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, S.; Kato, H.; Hirota, H.; Fusetani, N. Seven new polyacetylene derivatives, showing both potent metamorphosis-inducing activity in ascidian larvae and antifouling activity against barnacle larvae, from the marine sponge Callyspongia truncata. J. Nat. Prod. 1997, 60, 126–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, J.E.; Brocklehurst, K.J.; Marley, A.E.; Carey, F.; Carling, D.; Beri, R.K. Inhibition of lipolysis and lipogenesis in isolated rat adipocytes with AICAR, a cell-permeable activator of AMP-activated protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994, 353, 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.-J.; Kwon, E.-B.; Ryu, H.W.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.-W.; Kim, D.-Y.; Lee, M.K.; Oh, S.-R.; Lee, H.-S.; Lee, S.U.; et al. Polyacetylene from Dendropanax morbifera alleviates diet-induced obesity and hepatic steatosis by activating AMPK signaling pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Y.J.; Kim, K.S.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.R.; Lee, S.H.; Choi, H.B.; Cao, S.; Kumar, V.; Kwak, J.H.; et al. Protective effects of dendropanoxide isolated from Dendropanax morbifera against cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury via the AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2020, 145, 111605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Ryu, J.H. Dendropanax morbifera leaf extracts as PPAR α, γ and δ activity enhancers. KR201305 9128, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Zhang, N.; Wu, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Q. Syringin prevents cardiac hypertrophy induced by pressure overload through the attenuation of autophagy. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2017, 39, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Kim, M.-S.; Hyun, C.-K. Syringin attenuates insulin resistance via adiponectin-mediated suppression of low-grade chronic inflammation and ER stress in high-fat diet-fed mice. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 488, 40–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossin, A.Y.; Inafuku, M.; Takara, K.; Nugara, R.N.; Oku, H. Syringin: A phenylpropanoid glycoside compound in Cirsium brevicaule A. GRAY root modulates adipogenesis. Molecules 2021, 26, 1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Wu, Y.-X.; Qiu, Y.-b.; Wan, B.-b.; Liu, G.; Chen, J.-l.; Lu, M.-d.; Pang, Q.-f. Hyperoside suppresses hypoxia-induced A549 survival and proliferation through ferrous accumulation via AMPK/HO-1 axis. Phytomedicine 2020, 67, 153138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Fan, X.; Gu, W.; Ci, X.; Peng, L. Hyperoside relieves particulate matter-induced lung injury by inhibiting AMPK/mTOR-mediated autophagy deregulation. Pharmacol. Res. 2021, 167, 105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Liang, Q.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, H.; Olatunji, L.A. Hyperoside ameliorates renal tubular oxidative damage and calcium oxalate deposition in rats through AMPK/Nrf2 signaling axis. J. Renin-Angio.-Aldo. Syst. 2023, 2023, 5445548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.W., Y.; Zhu, X.; Tan, W.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z. Protective effect of hyperoside on obese mice with insulin resistance induced by high-fat diet. Shiyong Yaowu Yu Linchuang 2023, 26, 586–591. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.X.; Kang, S.; Yang, S.Y.; Kim, Y.H.; Li, W. Chemical constituents from Dendropanax morbiferus H. Lév. Stems and leaves and their chemotaxonomic significance. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2019, 87, 103936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanardi, M.M.; Sarotti, A.M. Sensitivity analysis of DP4+ with the probability distribution terms: Development of a universal and customizable method. J. Org. Chem. 2021, 86, 8544–8548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, T.; Schaumlöffel, A.; Hemberger, Y.; Bringmann, G. SpecDis: Quantifying the comparison of calculated and experimental electronic circular dichroism spectra. Chirality 2013, 25, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| position | δC | δH |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 147.2 | |

| 2 | 150.5 | |

| 3 | 112.4 | 7.08 (1H, m) |

| 4 | 137.5 | |

| 5 | 120.8 | 6.90 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 2.0 Hz) |

| 6 | 117.6 | 7.11 (1H, dd, J = 8.4, 1.4 Hz) |

| 1’ | 73.8 | 4.95 (1H, d, J = 5.3 Hz) |

| 2’ | 87.2 | 4.24 (1H, m) |

| 3’ | 71.4 | 3.39 (1H, m) |

| 4’ | 78.2 | 3.40 (1H, m) |

| 5’ | 61.5 | 3.55 (1H, m) |

| 6’ | 62.6 | 3.88 (1H, m) 3.69 (1H, m) |

| 1’‘ | 102.9 | 4.88 (1H, d, J = 7.6 Hz) |

| 2’‘ | 75.0 | 3.48 (1H, m) |

| 3’‘ | 77.9 | 3.47 (1H, m) |

| 4’‘ | 75.2 | 4.60 (1H, d, J = 5.4 Hz) |

| 5’‘ | 77.4 | 3.67 (1H, m) |

| 6’‘ | 64.3 | 3.54 (1H, m) 3.41 (1H, m) |

| 1’‘‘ | 139.9 | |

| 2’‘‘ | 105.2 | 6.73 (2H, s) |

| 3’‘‘ | 154.3 | |

| 4’‘‘ | 135.9 | |

| 5’‘‘ | 154.3 | |

| 6’‘‘ | 105.2 | 6.73 (2H, s) |

| 2-OCH3 | 56.8 | 3.85 (3H, s) |

| 3’‘‘-OCH3/5’‘‘-OCH3 | 56.7 | 3.82 (6H, s) |

| 2 | 3 | 4 | ||||

| Position | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC |

| 1 | 174.3 | 173.3 | 173.3 | |||

| 2 | 2.30 (2H, t, J = 7.5 Hz) | 34.1 | 2.28 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz) | 33.2 | 2.28 (2H, t, J = 7.4 Hz) | 33.2 |

| 3 | 1.62 (2H, m) | 24.9 | 1.50 (2H, m) | 24.3 | 1.50 (2H, m) | 24.3 |

| 4 | 1.31 (2H, m) | 29.0 a | 1.24 (2H, m) | 28.3 | 1.25 (2H, m) | 28.3 |

| 5 | 1.31 (2H, m) | 29.1a | 1.24 (2H, m) | 28.7 a | 1.25 (2H, m) | 28.5 a |

| 6 | 1.25 (2H, m) | 29.2 | 1.24 (2H, m) | 28.5 a | 1.25 (2H, m) | 28.6 a |

| 7 | 1.32 (2H, m) | 25.1 | 1.26 (2H, m) | 24.7 | 1.26 (2H, m) | 24.5 |

| 8 | 1.53 (2H, m) | 36.8 | 1.37 (2H, m) | 36.3 | 1.49 (1H, m) 1.34 (1H, m) |

36.4 |

| 9 | 4.20 (1H, m) | 72.0 | 4.03 (1H, m) | 69.8 | 4.35 (1H, m) | 68.5 |

| 10 | 6.34 (1H, dd, J = 15.9, 5.7 Hz) | 150.2 | 6.39 (1H, dd, J = 15.8, 5.1 Hz) | 152.5 | 6.10 (1H, dd, J = 11.1, 8.7 Hz) | 152.5 |

| 11 | 5.76 (1H, ddd, J = 15.9, 1.6, 0.8 Hz) | 107.9 | 5.77 (1H, d, J = 15.8 Hz) | 105.9 | 5.66 (1H, d, J = 11.1 Hz) | 106.2 |

| 12 | 77.7 | 76.9 | 77.1 | |||

| 13 | 73.5 | 73.1 | 75.2 | |||

| 14 | 71.5 | 67.6 | 68.4 | |||

| 15 | 77.2 | 85.3 | 84.2 | |||

| 16 | 5.96 (1H, dq, J = 5.8, 0.8 Hz | 64.7 | 4.28 (1H, t, J = 6.5 Hz) | 62.0 | 4.93 (1H, d, J = 5.4 Hz) | 61.7 |

| 17 | 5.88 (1H, ddd, J = 16.9, 10.3, 5.7 Hz) | 132.1 | 1.58 (2H, m) | 30.3 | 5.88 (1H, ddd, J = 17.0, 10.1, 5.4 Hz) | 137.3 |

| 18 |

trans: 5.55 (1H, dt, J = 16.9, 1.1 Hz) cis: 5.35 (1H, dt, J = 10.3, 1.1 Hz) |

119.6 | 0.90 (3H, t, J = 7.4 Hz) | 9.4 |

trans: 5.33 (1H, dt, J = 17.1, 1.5 Hz) cis: 5.16 (1H, dt, J = 10.1, 1.5 Hz) |

115.5 |

| 1-OCH3 | 3.67 (3H, s) | 51.5 | 3.58 (3H, s) | 51.1 | 3.58 (3H, s) | 51.0 |

| 16-OCOCH3 | 169.5 | |||||

| 16-OCOCH3 | 2.11 (3H, s) | 20.9 | ||||

| Compound | Autodock Vina | Autodock 4 | LeDock | Dock 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AICAR (Control) | -6.3 | -7.4 | -6.0 | -33.5 |

| 1 | -5.9 | -6.1 | -5.4 | -55.3 |

| 2 | -5.8 | -5.3 | -3.5 | -42.9 |

| 3 | -5.7 | -5.3 | -4.2 | -38.3 |

| 4 | -5.8 | -5.8 | -4.4 | -39.5 |

| 5 | -5.8 | -5.5 | -4.1 | -35.6 |

| 6 | -6.8 | -7.2 | -5.2 | -37.8 |

| 7 | -6.8 | -8.7 | -6.0 | -55.5 |

| 8 | -8.9 | -11.4 | -7.0 | -40.6 |

| 9 | -6.6 | -6.6 | -4.4 | -46.3 |

| 10 | -6.5 | -9.3 | -3.3 | -28.5 |

| 11 | -7.6 | -7.9 | -4.5 | -43.8 |

| Compound | Autodock Vina | Autodock 4 | LeDock | Dock 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LY3000328 (Control) | -7.2 | -8.1 | -5.6 | -127.0 |

| 1 | -6.1 | -7.5 | -5.5 | -54.7 |

| 2 | -5.2 | -4.6 | -4.0 | -39.5 |

| 3 | -5.7 | -4.6 | -4.2 | -42.6 |

| 4 | -5.7 | -5.7 | -4.5 | -44.0 |

| 5 | -5.6 | -4.6 | -4.2 | -43.6 |

| 6 | -6.3 | -6.9 | -5.8 | -39.3 |

| 7 | -6.5 | -9.1 | -5.8 | -50.5 |

| 8 | -8.1 | -10.3 | -6.1 | -42.2 |

| 9 | -6.5 | -5.9 | -4.5 | -36.5 |

| 10 | -8.5 | -9.4 | -3.8 | -33.1 |

| 11 | -6.9 | -7.3 | -4.6 | -42.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).