Submitted:

25 October 2024

Posted:

28 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

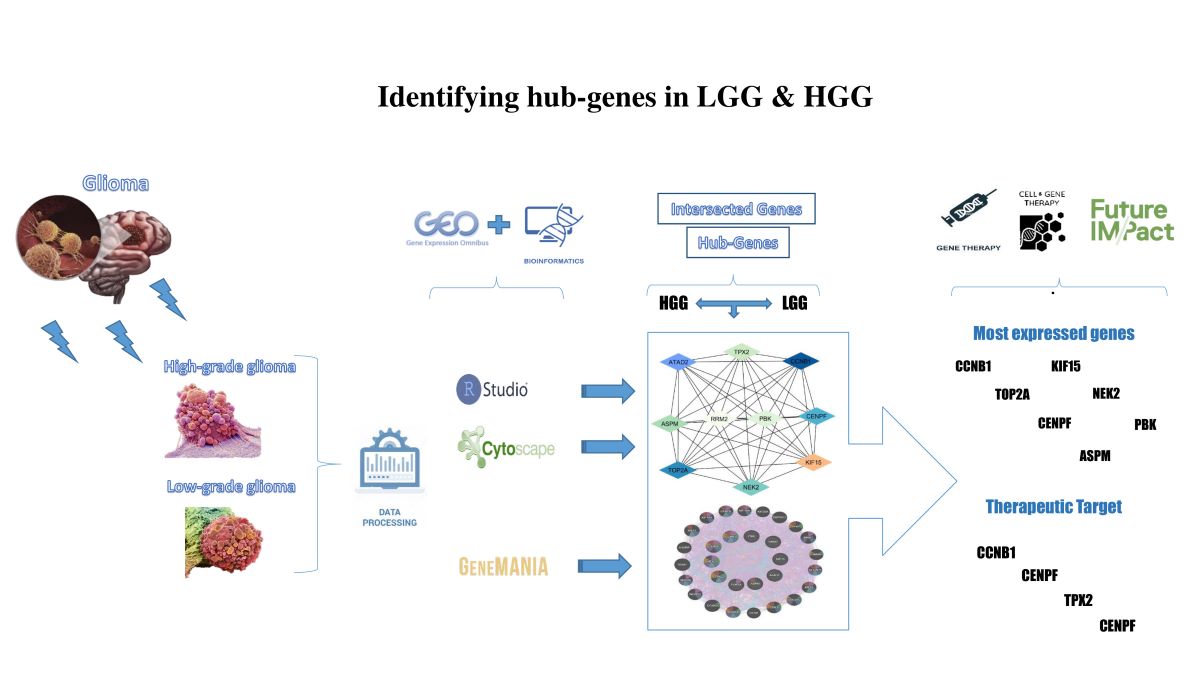

1. Inrtoduction

| Sample Number | Data Generation Platform | Data Type | Experiment design | Sample Size / VolumeDisease Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE50161 | GPL570 | High grade glioma | Clinical trials of immunotherapy | n=130 samples117 13 |

| GSE107850 | GPL14951 | Low grade glioma | Clinical trials of chemotherapy and radiotherapy | n=195 samples195 0 |

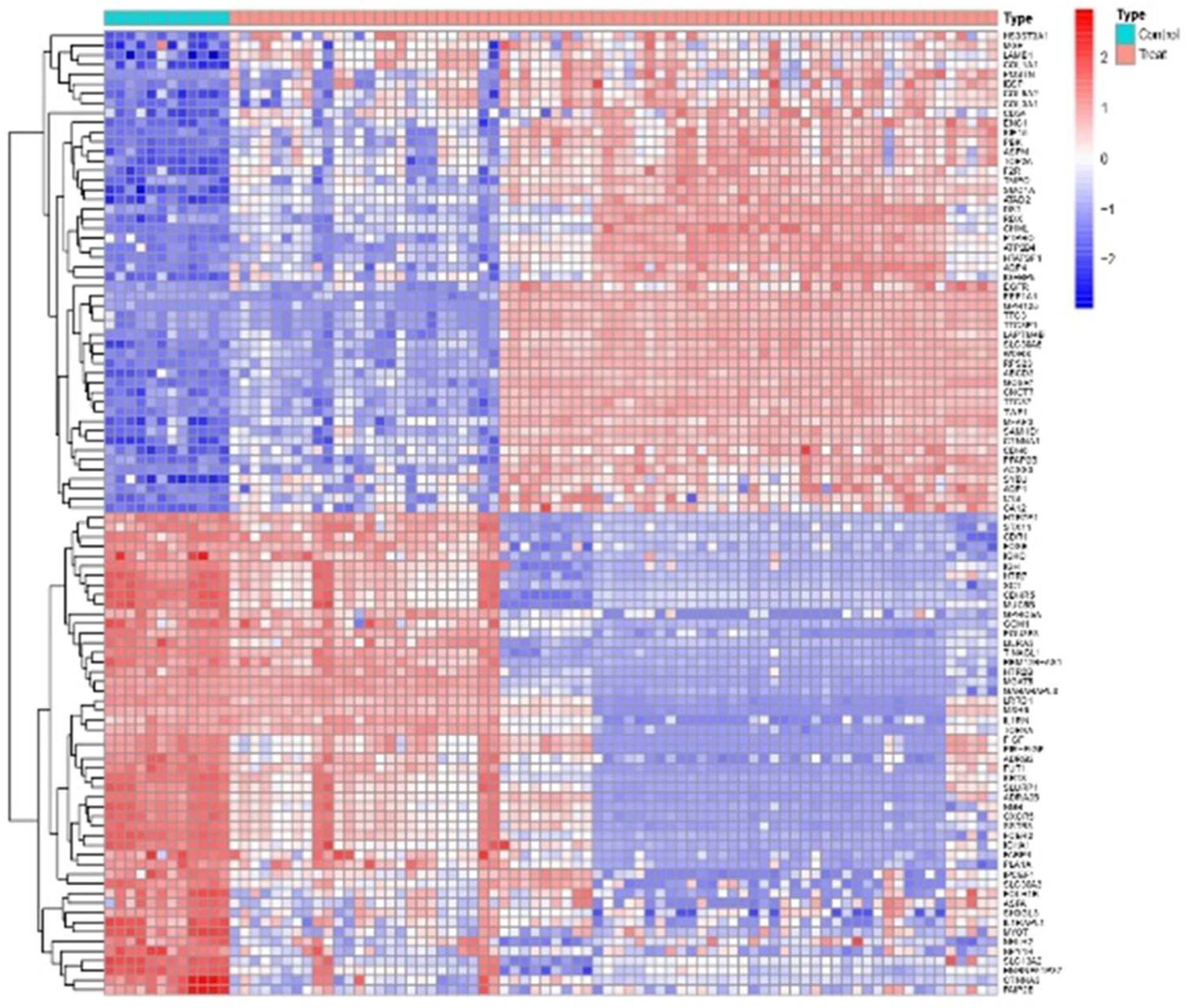

1.1. Differential Expression Analysis

1.2. Venn Analysis of Intersection Genes

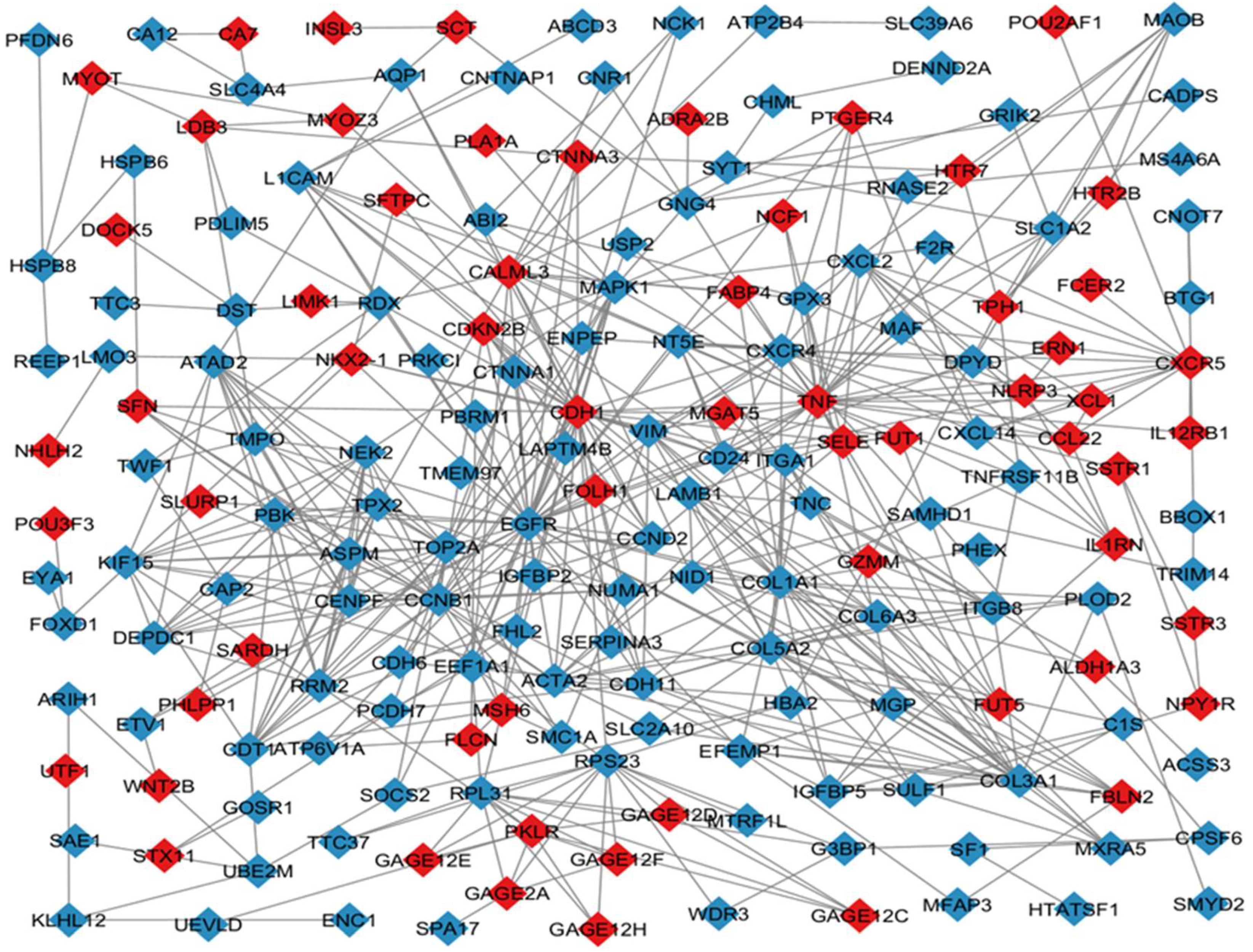

1.3. Cytoscape Analysis

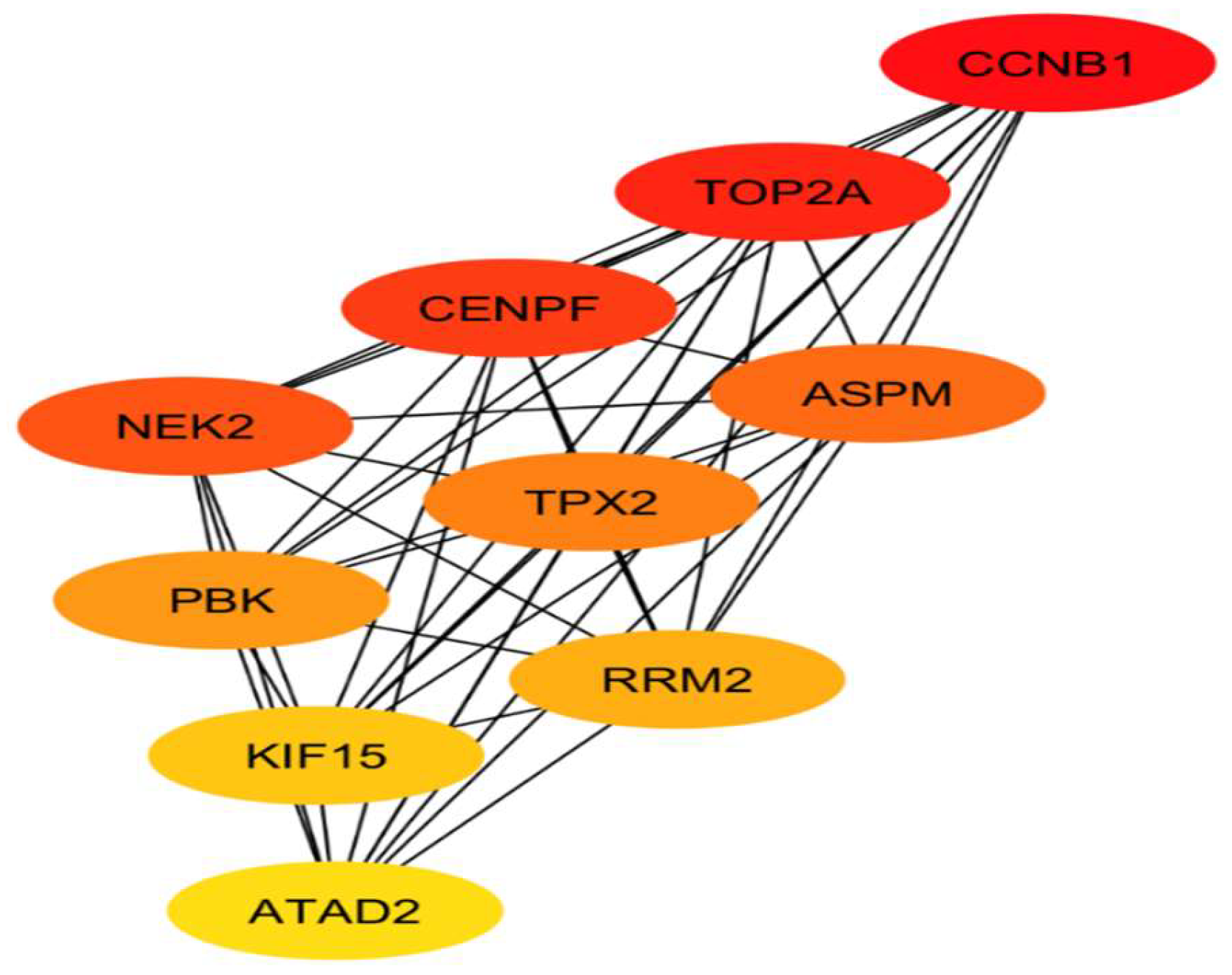

1.4. CytoHubba Analysis

| Ranking | Name | Type |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CCNB1 | Up-regulated |

| 2 | TOP2A | Up-regulated |

| 3 | CENPF | Up-regulated |

| 4 | NEK2 | Up-regulated |

| 5 | ASPM | Up-regulated |

| 6 | TPX2 | Up-regulated |

| 7 | PBK | Up-regulated |

| 8 | RRM2 | Up-regulated |

| 9 | KIF15 | Up-regulated |

| 10 | ATAD2 | Up-regulated |

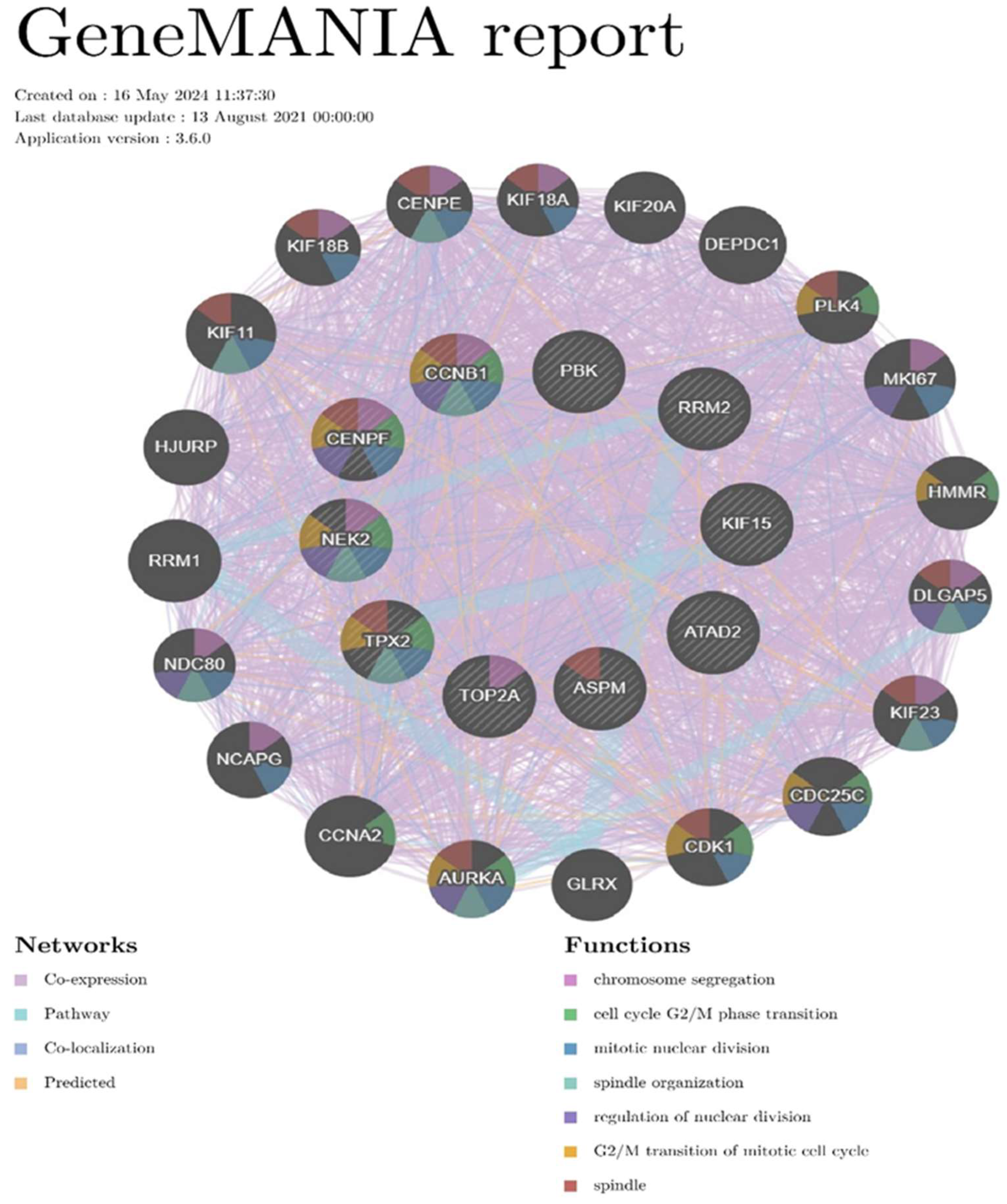

1.5. Gene Mania Analysis

2. Research Progress About Hub Genes Involved in Gliomas

2.1. Review Methods

| Index | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Types | Prospective/Retrospective cohort, Systemic review, Meta-analysis, Randomized controlled trial, etc. | *Case reports, Experts’ opinions, and Personal websites. * Non-affluent abstract (lack of required data) |

| Time of the study | New publications after 2007-2024 | Old publications before 2007 |

| Language of the study | Publications in English or translated to English | Non-English publications |

| Methods | *Quantitative *Studies depend on clinical trials and clinical systemic analysis. |

*Qualitative *Studies depend on questionnaire or interview |

2.2. Review Findings

2.2.1. CCNB1

2.2.2. TOP2A

2.2.3. CENPF

2.2.4. NEK2

2.2.5. ASPM

2.2.6. TPX2

2.2.7. PBK

2.2.8. RRM2

2.2.9. KIF15

2.2.10. ATAD2

| Title | ReferencesAuthors Year | Key points of finding |

|---|---|---|

| CCNB1 | ||

| Hub biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of glioblastoma based on microarray technology. | Cui, K, et al. (2021)[72] | CCNB1 exhibits elevated expression levels in patients with glioblastoma (GBM) compared to control groups, increased expression is associated with disease-free survival and overall survival rates among GBM patients. |

| USP39-mediated deubiquitination of Cyclin B1 promotes tumor cell proliferation and glioma progression. | Xiao, Y, et al. (2023)[74] | Overexpression of Cyclin CCNB1 effectively reverses the cell cycle arrest occurring at the G2/M transition and the inhibited proliferation of glioma cells resulting from USP39 knockdown. |

| TOP2A | ||

| DNA topoisomerase II alpha promotes the metastatic characteristics of glioma cells by transcriptionally activating β-catenin. | Liu, Y, et al. (2022)[77] | Silencing of TOP2A hindered glioma cell proliferation and aggressiveness. |

| Targeted sequencing of cancer-related genes reveals a recurrent TOP2A variant which affects DNA binding and coincides with global transcriptional changes in glioblastoma. | Gielniewski, B, et al. (2023)[78] | The deleterious TOP2A mutation observed in these IDH-wild-type glioblastomas (GBMs), and potentially contributing to the pathology of the disease. |

| CENPF | ||

| Transcriptome analysis revealed CENPF associated with glioma prognosis. | Zhang, M, et al. (2021)[82] | CENPF is one of the genes that exhibit substantial protein expression levels, and strongly associated with glioma development, CENPF as a potential biomarker candidate in glioma research |

| CENPE promotes glioblastomas proliferation by directly binding to WEE1. | Ma, C, et al. (2020)[83] | CENPE regulates GBM proliferation primarily through the WEE1 G2 checkpoint kinase (WEE1) pathway, thereby influencing cell cycle progression and proliferation in GBM cells. |

| NEK2 | ||

| NEK2 enhances malignancies of glioblastoma via NIK/NF-Κb pathway. | Xiang, J, et al. (2022)[87] | NEK2 has been identified as significantly upregulated in GBM, and knockdown of NEK2 attenuates cell proliferation, migration, invasion, and tumorigenesis in GBM, |

| CCNA2 and NEK2 regulate glioblastoma progression by targeting the cell cycle. | Zhou, H, et al. (2024)[88] | Elevated expression of NEK2 in glioma is associated with poor clinical outcomes, and upregulated in a subset of positive neural progenitor cells (P-NPCs), NEK2 is crucial in regulating glioblastoma progression. |

| ASPM | ||

| ASPM Is a Prognostic Biomarker and Correlates With Immune Infiltration in Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma and Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. | Deng, T, et al. (2022)[99] | ASPM was found to be strongly correlated with tumor grade, exhibiting an increase in recurrence compared to the initial lesion. |

| ASPM is a predictor of overall survival and has therapeutic potential in endometrial cancer. | Zhou, J, et al. (2020)[101] | Recent studies have demonstrated ASPM overexpression in malignant gliomas, while its knockdown has been shown to effectively inhibit tumour proliferation. |

| TPX2 | ||

| High TPX2 expression results in poor prognosis, and Sp1 mediates the coupling of the CX3CR1/CXCL10 chemokine pathway to the PI3K/Akt pathway through targeted inhibition of TPX2 in endometrial cancer. | Yang, M, et al. (2024)[106] | Elevated TPX2 levels have been observed in several glioma cell lines, where it promotes cellular proliferation, decreases the proportion of cells in the G0/G1 phase. |

| CircPOSTN/miR-361-5p/TPX2 axis regulates cell growth, apoptosis and aerobic glycolysis in glioma cells. | Long, N, et al. (2020)[109] | TPX2 may facilitate glioma progression by activating the protein kinase B (AKT) signaling pathway. |

| PBK | ||

| Identification of CDK1, PBK, and CHEK1 as an Oncogenic Signature in Glioblastoma: A Bioinformatics Approach to Repurpose Dapagliflozin as a Therapeutic Agent. | Chinyama, H, et al. (2023)[114] | PBK is one of three key genes, and highlighting PBK’s role as a biomarker with predictive properties in GBM. |

| Identification of PBK as a hub gene and potential therapeutic target for medulloblastoma. | Deng, Y, et al. (2022)[115] | Abnormal expression of PBK in medulloblastoma, and significant association between higher PBK expression levels and poorer clinical outcomes in non-wingless medulloblastomas. |

| RRM2 | ||

| RRM2 is a potential prognostic biomarker with functional significance in glioma. | Sun, H, et al. (2019)[123] | Elevated RRM2 expression is negatively correlated with the survival of glioma patients. When RRM2 was knocked down using RNA interference (RNAi), RNA sequencing revealed an upregulation of genes involved in apoptosis, proliferation, cell adhesion, and the negative regulation of signaling. |

| Inhibition of RRM2 radiosensitizes glioblastoma and uncovers synthetic lethality in combination with targeting CHK1. | Corrales, S, et al. (2023)[125] | Targeting RRM2 could be a promising strategy for glioma treatment, impacting apoptosis, cell proliferation, and signaling pathways. |

| KIF15 | ||

| Identification of KIF15 as a potential therapeutic target and prognostic factor for glioma. | Wang, Q, et al. (2020)[131] | KIF15 has been found to be significantly upregulated in glioma tumor tissues, demonstrating a positive correlation with pathological staging, recurrence risk, and unfavorable prognosis. Elucidated the regulatory role of KIF15 knockdown on apoptosis- and cell cycle-related proteins. |

| Kinesin family member 15 can promote the proliferation of glioblastoma. | Wang, L, et al. (2022)[132] | KIF15 plays a crucial role in glioblastoma progression as a potential genetic factor. Elevated expression levels of KIF15 have been observed in GBM tumor tissues, showing correlations with tumor size, clinical stage. |

| ATAD2 | ||

| Polo-like kinase4 promotes tumorigenesis and induces resistance to radiotherapy in glioblastoma. | Wang, J, et al. (2019)[138] | Upregulation of ATAD2 through exogenous overexpression significantly increased the expression of PLK4 in GBM cells, and ATAD2-dependent transcriptional regulation of PLK4 contributes to enhanced cell proliferation and tumorigenesis, as indicated by recent research findings. |

| Tumor-Promoting ATAD2 and Its Preclinical Challenges. | Liu, H, et al. (2022)[139] | Exogenous ATAD2 can lead to a substantial increase in the expression levels of PLK4, thereby promoting the initiation of GBM and its resistance to radiation therapy. This reveals that ATAD2 might play a pivotal role as a regulator of PLK4 transcription in GBM. |

3. Summary and Discussion

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Statement

References

- Charles, N. A.; Holland, E. C.; Gilbertson, R.; Glass, R.; Kettenmann, H. The brain tumor microenvironment. Glia 2012, 60(3), 502–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araque, A.; Navarrete, M. Glial cells in neuronal network function. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2010, 365(1551), 2375–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grady, C.; Melnick, K.; Porche, K.; Dastmalchi, F.; Hoh, D. J.; Rahman, M.; Ghiaseddin, A. Glioma Immunotherapy: Advances and Challenges for Spinal Cord Gliomas. Neurospine 2022, 19(1), 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, X.; Gao, K.; Bai, X.; Wang, N.; Xie, W.; Liu, H. Polo-like kinase 4 promotes tumorigenesis and induces resistance to radiotherapy in glioblastoma. Oncol Rep 2019, 41(4), 2159–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Kang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, R.; Yu, J.; Li, W. Signaling pathways in brain tumors and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2023, 8(1), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samad, M. A.; Nathani, K. R.; Choudry, U. K.; Waqas, M.; Khan, S. A.; Enam, S. A. Evidence-based advances in glioma management. IJS Short Reports.

- Xu, C.; Xiao, M.; Li, X.; Xin, L.; Song, J.; Zhan, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Q.; Yuan, X.; Tan, Y.; et al. Origin, activation, and targeted therapy of glioma-associated macrophages. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 974996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalamarty, S. S. K.; Filipczak, N.; Li, X.; Subhan, M. A.; Parveen, F.; Ataide, J. A.; Rajmalani, B. A.; Torchilin, V. P. Mechanisms of Resistance and Current Treatment Options for Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM). Cancers (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Hanif, F.; Muzaffar, K.; Perveen, K.; Malhi, S. M.; Simjee Sh, U. Glioblastoma Multiforme: A Review of its Epidemiology and Pathogenesis through Clinical Presentation and Treatment. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2017, 18(1), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevastre, A. S.; Costachi, A.; Tataranu, L. G.; Brandusa, C.; Artene, S. A.; Stovicek, O.; Alexandru, O.; Danoiu, S.; Sfredel, V.; Dricu, A. Glioblastoma pharmacotherapy: A multifaceted perspective of conventional and emerging treatments (Review). Exp Ther Med 2021, 22(6), 1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angom, R. S.; Nakka, N. M.; Bhattacharya, S. Advances in Glioblastoma Therapy: An Update on Current Approaches. In Brain Sciences, 2023; Vol. 13.

- Yang, K.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, N.; Wu, W.; Wang, Z.; Dai, Z.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y.; et al. Glioma targeted therapy: insight into future of molecular approaches. Mol Cancer 2022, 21(1), 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shikalov, A.; Koman, I.; Kogan, N. M. Targeted Glioma Therapy—Clinical Trials and Future Directions. In Pharmaceutics, 2024; Vol. 16.

- Carrera, D.; Hayes, J.; Mueller, S.; Shelton, S.; Weinschenk, T.; Song, C.; Fritsche, J.; Schoor, O.; Kuttruff-Coqui, S.; Hilf, N.; et al. IMMU-52. SELECTION OF GLIOMA T-CELL THERAPY TARGETS BASED ON THE ANALYSIS OF TUMOR IMMUNOPEPTIDOME AND EXPRESSION PROFILES. Neuro-Oncology 2017, 19, vi124–vi124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, M.; van den Bent, M.; Preusser, M.; Le Rhun, E.; Tonn, J. C.; Minniti, G.; Bendszus, M.; Balana, C.; Chinot, O.; Dirven, L.; et al. EANO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of diffuse gliomas of adulthood. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2021, 18(3), 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, Z.; Chen, Y.; Geng, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, X.; Yan, Q.; Wang, T.; Ling, C.; Xu, Y.; Duan, J.; et al. NcRNAs: Multi-angle participation in the regulation of glioma chemotherapy resistance (Review). Int J Oncol. [CrossRef]

- Lawrie, T. A.; Gillespie, D.; Dowswell, T.; Evans, J.; Erridge, S.; Vale, L.; Kernohan, A.; Grant, R. Long-term neurocognitive and other side effects of radiotherapy, with or without chemotherapy, for glioma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019, 8(8), Cd013047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leary, J. B.; Anderson-Mellies, A.; Green, A. L. Population-based analysis of radiation-induced gliomas after cranial radiotherapy for childhood cancers. Neurooncol Adv 2022, 4(1), vdac159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Cao, S.; Imbach, K. J.; Gritsenko, M. A.; Lih, T.-S. M.; Kyle, J. E.; Yaron-Barir, T. M.; Binder, Z. A.; Li, Y.; Strunilin, I.; et al. Multi-scale signaling and tumor evolution in high-grade gliomas. Cancer Cell, 1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda, E.; Domenech, M.; Hernández, A.; Comas, S.; Balaña, C. Recurrent Glioblastoma: Ongoing Clinical Challenges and Future Prospects. Onco Targets Ther 2023, 16, 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvi, M. A.; Ida, C. M.; Paolini, M. A.; Kerezoudis, P.; Meyer, J.; Barr Fritcher, E. G.; Goncalves, S.; Meyer, F. B.; Bydon, M.; Raghunathan, A. Spinal cord high-grade infiltrating gliomas in adults: clinico-pathological and molecular evaluation. Modern Pathology 2019, 32(9), 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, S.; Choudhury, A.; Keough, M. B.; Seo, K.; Ni, L.; Kakaizada, S.; Lee, A.; Aabedi, A.; Popova, G.; Lipkin, B.; et al. Glioblastoma remodelling of human neural circuits decreases survival. Nature 2023, 617(7961), 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Aaroe, A.; Liang, J.; Puduvalli, V. K. Tumor microenvironment in glioblastoma: Current and emerging concepts. Neurooncol Adv 2023, 5(1), vdad009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, H. S.; Johung, T. B.; Caretti, V.; Noll, A.; Tang, Y.; Nagaraja, S.; Gibson, E. M.; Mount, C. W.; Polepalli, J.; Mitra, S. S.; et al. Neuronal Activity Promotes Glioma Growth through Neuroligin-3 Secretion. Cell 2015, 161(4), 803–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyadharan, S.; Prabhakar Rao, B. V.; Perumal, Y.; Chandrasekharan, K.; Rajagopalan, V. Deep Learning Classifies Low- and High-Grade Glioma Patients with High Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Specificity Based on Their Brain White Matter Networks Derived from Diffusion Tensor Imaging. In Diagnostics, 2022; Vol. 12.

- Park, Y. W.; Vollmuth, P.; Foltyn-Dumitru, M.; Sahm, F.; Ahn, S. S.; Chang, J. H.; Kim, S. H. The 2021 WHO Classification for Gliomas and Implications on Imaging Diagnosis: Part 2—Summary of Imaging Findings on Pediatric-Type Diffuse High-Grade Gliomas, Pediatric-Type Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas, and Circumscribed Astrocytic Gliomas. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 2023, 58(3), 690–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, G.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Xiangli, W.; Yang, H.; Qi, X.; Cui, X.; Idrees, B. S.; Wei, K.; Khan, M. N. Discrimination of infiltrative glioma boundary based on laser-induced breakdown spectroscopy. Spectrochimica Acta Part B: Atomic Spectroscopy 2020, 165, 105787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Hu, G.; Yang, K.; Xiao, C.; Hu, J.; Li, Z.; Zou, Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Alterations of white matter integrity associated with cognitive deficits in patients with glioma. Brain Behav 2020, 10(7), e01639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, P.; Wali, R. 10-Year-Old Pakistani Boy With Multiple Malignancies: Loss Of Pms2-Constitutional Mismatch Repair Deficiency. Journal of Ayub Medical College Abbottabad 2022, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rallis, K. S.; George, A. M.; Wozniak, A. M.; Bigogno, C. M.; Chow, B.; Hanrahan, J. G.; Sideris, M. Molecular Genetics and Targeted Therapies for Paediatric High-grade Glioma. Cancer Genomics Proteomics 2022, 19(4), 390–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollis, P. M.; Ebert, L. M.; Toubia, J.; Bastow, C. R.; Ormsby, R. J.; Poonnoose, S. I.; Lenin, S.; Tea, M. N.; Pitson, S. M.; Gomez, G. A.; et al. Characterising Distinct Migratory Profiles of Infiltrating T-Cell Subsets in Human Glioblastoma. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 850226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toader, C.; Eva, L.; Costea, D.; Corlatescu, A. D.; Covache-Busuioc, R. A.; Bratu, B. G.; Glavan, L. A.; Costin, H. P.; Popa, A. A.; Ciurea, A. V. Low-Grade Gliomas: Histological Subtypes, Molecular Mechanisms, and Treatment Strategies. Brain Sci. [CrossRef]

- Toader, C.; Eva, L.; Costea, D.; Corlatescu, A. D.; Covache-Busuioc, R.-A.; Bratu, B.-G.; Glavan, L. A.; Costin, H. P.; Popa, A. A.; Ciurea, A. V. Low-Grade Gliomas: Histological Subtypes, Molecular Mechanisms, and Treatment Strategies. In Brain Sciences, 2023; Vol. 13.

- Gilard, V.; Tebani, A.; Dabaj, I.; Laquerrière, A.; Fontanilles, M.; Derrey, S.; Marret, S.; Bekri, S. Diagnosis and Management of Glioblastoma: A Comprehensive Perspective. J Pers Med. [CrossRef]

- Greuter, L.; Guzman, R.; Soleman, J. Pediatric and Adult Low-Grade Gliomas: Where Do the Differences Lie? Children (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, R.; Ren, H.; Liu, H.; Liu, H. Predicting factors of tumor progression in adult patients with low-grade glioma within five years after surgery. Translational Cancer Research 2021, 10(4), 1907–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, D. N.; Perry, A.; Reifenberger, G.; von Deimling, A.; Figarella-Branger, D.; Cavenee, W. K.; Ohgaki, H.; Wiestler, O. D.; Kleihues, P.; Ellison, D. W. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol 2016, 131(6), 803–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fathallah-Shaykh, H. M.; DeAtkine, A.; Coffee, E.; Khayat, E.; Bag, A. K.; Han, X.; Warren, P. P.; Bredel, M.; Fiveash, J.; Markert, J.; et al. Diagnosing growth in low-grade gliomas with and without longitudinal volume measurements: A retrospective observational study. PLoS Med 2019, 16(5), e1002810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jooma, R.; Waqas, M.; Khan, I. Diffuse Low-Grade Glioma - Changing Concepts in Diagnosis and Management: A Review. Asian J Neurosurg 2019, 14(2), 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Yan, W.; Zhan, Z.; Hong, X.; Yan, H. Epidemiology and risk stratification of low-grade gliomas in the United States, 2004-2019: A competing-risk regression model for survival analysis. Front Oncol 2023, 13, 1079597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitfield, B. T.; Huse, J. T. Classification of adult-type diffuse gliomas: Impact of the World Health Organization 2021 update. Brain Pathology 2022, 32(4), e13062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Sharie, S.; Abu Laban, D.; Al-Hussaini, M. Decoding Diffuse Midline Gliomas: A Comprehensive Review of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. Cancers (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Wang, J.; Dong, Q.; Zhu, L.; Lin, W.; Jiang, X. Predictors of tumor progression of low-grade glioma in adult patients within 5 years follow-up after surgery. Front Surg 2022, 9, 937556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, B. M.; Cheong, J. H.; Ryu, J. I.; Won, Y. D.; Min, K.-W.; Han, M.-H. Significant Genes Associated with Mortality and Disease Progression in Grade II and III Glioma. In Biomedicines, 2024; Vol. 12.

- Tesileanu, C. M. S.; Vallentgoed, W. R.; Sanson, M.; Taal, W.; Clement, P. M.; Wick, W.; Brandes, A. A.; Baurain, J. F.; Chinot, O. L.; Wheeler, H.; et al. Non-IDH1-R132H IDH1/2 mutations are associated with increased DNA methylation and improved survival in astrocytomas, compared to IDH1-R132H mutations. Acta Neuropathol 2021, 141(6), 945–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Parsons, D. W.; Jin, G.; McLendon, R.; Rasheed, B. A.; Yuan, W.; Kos, I.; Batinic-Haberle, I.; Jones, S.; Riggins, G. J.; et al. IDH1 and IDH2 mutations in gliomas. N Engl J Med 2009, 360(8), 765–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosén, E.; Mangukiya, H. B.; Elfineh, L.; Stockgard, R.; Krona, C.; Gerlee, P.; Nelander, S. Inference of glioblastoma migration and proliferation rates using single time-point images. Communications Biology 2023, 6(1), 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, H.; Gao, P. Metabolic reprogramming and epigenetic modifications on the path to cancer. Protein Cell 2022, 13(12), 877–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, C.; Chen, F. Connections between metabolism and epigenetics in cancers. Semin Cancer Biol 2019, 57, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poljsak, B.; Kovac, V.; Dahmane, R.; Levec, T.; Starc, A. Cancer Etiology: A Metabolic Disease Originating from Life’s Major Evolutionary Transition? Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 7831952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelin, W. G., Jr.; McKnight, S. L. Influence of metabolism on epigenetics and disease. Cell 2013, 153(1), 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nencioni, A.; Caffa, I.; Cortellino, S.; Longo, V. D. Fasting and cancer: molecular mechanisms and clinical application. Nat Rev Cancer 2018, 18(11), 707–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, L.; Pan, Y.; Tu, Q.; He, T.; Zhou, T.; Yuan, J.; Tong, M. PLU1 Promotes the Proliferation and Migration of Glioma Cells and Regulates Metabolism. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2023, 22, 15330338231175768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakola, A. S.; Myrmel, K. S.; Kloster, R.; Torp, S. H.; Lindal, S.; Unsgård, G.; Solheim, O. Comparison of a strategy favoring early surgical resection vs a strategy favoring watchful waiting in low-grade gliomas. Jama 2012, 308(18), 1881–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J. S.; Chang, E. F.; Lamborn, K. R.; Chang, S. M.; Prados, M. D.; Cha, S.; Tihan, T.; Vandenberg, S.; McDermott, M. W.; Berger, M. S. Role of extent of resection in the long-term outcome of low-grade hemispheric gliomas. J Clin Oncol 2008, 26(8), 1338–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogdańska, M. U.; Bodnar, M.; Piotrowska, M. J.; Murek, M.; Schucht, P.; Beck, J.; Martínez-González, A.; Pérez-García, V. M. A mathematical model describes the malignant transformation of low grade gliomas: Prognostic implications. PLoS One 2017, 12(8), e0179999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Jones, H. M.; Witt, D.; Boop, F.; Bouffet, E.; Rodriguez-Galindo, C.; Qaddoumi, I.; Moreira, D. C. Outcomes of Children With Low-Grade Gliomas in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. JCO Glob Oncol 2022, 8, e2200199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangiola, A.; Anile, C.; Pompucci, A.; Capone, G.; Rigante, L.; De Bonis, P. Glioblastoma therapy: going beyond Hercules Columns. Expert Rev Neurother 2010, 10(4), 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaichana, K. L.; McGirt, M. J.; Laterra, J.; Olivi, A.; Quiñones-Hinojosa, A. Recurrence and malignant degeneration after resection of adult hemispheric low-grade gliomas. J Neurosurg 2010, 112(1), 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakarunchai, I.; Sangthong, R.; Phuenpathom, N.; Phukaoloun, M. Free survival time of recurrence and malignant transformation and associated factors in patients with supratentorial low-grade gliomas. J Med Assoc Thai, 1542. [Google Scholar]

- Romanowski, C. A. J.; Hoggard, N.; Jellinek, D. A.; Levy, D.; Wharton, S. B.; Kotsarini, C.; Batty, R.; Wilkinson, I. D. Low Grade Gliomas. Can We Predict Tumour Behaviour from Imaging Features? The Neuroradiology Journal. [CrossRef]

- Griesinger, A. M.; Birks, D. K.; Donson, A. M.; Amani, V.; Hoffman, L. M.; Waziri, A.; Wang, M.; Handler, M. H.; Foreman, N. K. Characterization of distinct immunophenotypes across pediatric brain tumor types. J Immunol 2013, 191(9), 4880–4888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Weenink, B.; van den Bent, M. J.; Erdem-Eraslan, L.; Kros, J. M.; Sillevis Smitt, P.; Hoang-Xuan, K.; Brandes, A. A.; Vos, M.; Dhermain, F.; et al. Expression-based intrinsic glioma subtypes are prognostic in low-grade gliomas of the EORTC22033-26033 clinical trial. Eur J Cancer 2018, 94, 168–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tandon, G.; Yadav, S.; Kaur, S. Chapter 24 - Pathway modeling and simulation analysis. In Bioinformatics, Singh, D. B., Pathak, R. K. Eds.; Academic Press, 2022; pp 409-423.

- Bordini, M.; Zappaterra, M.; Soglia, F.; Petracci, M.; Davoli, R. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis identifies molecular pathways and hub genes involved in broiler White Striping and Wooden Breast myopathies. Scientific Reports 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz, M.; Lopes, C.; Huck, G.; Dong, Y.; Sumer, S.; Bader, G. Cytoscape.js: A graph theory library for visualisation and analysis. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). [CrossRef]

- Page, M.; McKenzie, J.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, B.; Chen, M.-L.; Gao, Z.-Q.; Mi, T.; Shi, Q.-L.; Dong, J.-J.; Tian, X.-M.; Liu, F.; Wei, G.-H. CCNB1 is a novel prognostic biomarker and promotes proliferation, migration and invasion in Wilms tumor. BMC Medical Genomics 2023, 16(1), 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Zhu, H. B.; Song, G. D.; Cheng, J. H.; Li, C. Z.; Zhang, Y. Z.; Zhao, P. Regulating the CCNB1 gene can affect cell proliferation and apoptosis in pituitary adenomas and activate epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Oncol Lett 2019, 18(5), 4651–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, X.; Li, Q.; Li, T. Lamprey Prohibitin2 Arrest G2/M Phase Transition of HeLa Cells through Down-regulating Expression and Phosphorylation Level of Cell Cycle Proteins. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 3932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnittger, A.; De Veylder, L. The Dual Face of Cyclin B1. Trends Plant Sci 2018, 23(6), 475–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, K.; Chen, J. H.; Zou, Y. F.; Zhang, S. Y.; Wu, B.; Jing, K.; Li, L. W.; Xia, L.; Sun, C.; Dong, Y. L. Hub biomarkers for the diagnosis and treatment of glioblastoma based on microarray technology. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2021, 20, 1533033821990368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducray, F.; Idbaih, A.; de Reyniès, A.; Bièche, I.; Thillet, J.; Mokhtari, K.; Lair, S.; Marie, Y.; Paris, S.; Vidaud, M.; et al. Anaplastic oligodendrogliomas with 1p19q codeletion have a proneural gene expression profile. Mol Cancer 2008, 7, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Chen, X.; Hu, W.; Ma, W.; Di, Q.; Tang, H.; Zhao, X.; Huang, G.; Chen, W. USP39-mediated deubiquitination of Cyclin B1 promotes tumor cell proliferation and glioma progression. Transl Oncol 2023, 34, 101713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deweese, J. E.; Osheroff, N. The DNA cleavage reaction of topoisomerase II: wolf in sheep’s clothing. Nucleic Acids Res 2009, 37(3), 738–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, T.; Wang, Y.; Qian, D.; Liang, Q.; Wang, B. Over-expression of TOP2A as a prognostic biomarker in patients with glioma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 1228. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, J.; Song, J. S.; Zhou, H. Y.; Li, J. H.; Luo, C.; Geng, X.; Zhao, H. X. DNA topoisomerase II alpha promotes the metastatic characteristics of glioma cells by transcriptionally activating β-catenin. Bioengineered 2022, 13(2), 2207–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielniewski, B.; Poleszak, K.; Roura, A.-J.; Szadkowska, P.; Jacek, K.; Krol, S. K.; Guzik, R.; Wiechecka, P.; Maleszewska, M.; Kaza, B.; et al. Targeted sequencing of cancer-related genes reveals a recurrent TOP2A variant which affects DNA binding and coincides with global transcriptional changes in glioblastoma. International Journal of Cancer 2023, 153(5), 1003–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, A. M.; Asfahani, R.; Carroll, P.; Bicknell, L.; Lescai, F.; Bright, A.; Chanudet, E.; Brooks, A.; Christou-Savina, S.; Osman, G.; et al. The kinetochore protein, CENPF, is mutated in human ciliopathy and microcephaly phenotypes. J Med Genet 2015, 52(3), 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filges, I.; Bruder, E.; Brandal, K.; Meier, S.; Undlien, D. E.; Waage, T. R.; Hoesli, I.; Schubach, M.; de Beer, T.; Sheng, Y.; et al. Strømme Syndrome Is a Ciliary Disorder Caused by Mutations in CENPF. Hum Mutat 2016, 37(4), 359–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balamuth, N. J.; Wood, A.; Wang, Q.; Jagannathan, J.; Mayes, P.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Rappaport, E.; Courtright, J.; Pawel, B.; et al. Serial transcriptome analysis and cross-species integration identifies centromere-associated protein E as a novel neuroblastoma target. Cancer Res 2010, 70(7), 2749–2758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, Q.; Bai, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J. Transcriptome analysis revealed CENPF associated with glioma prognosis. Math Biosci Eng 2021, 18(3), 2077–2096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, C.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J.; Liao, K.; Yang, M.; Li, F.; Zhang, M. CENPE promotes glioblastomas proliferation by directly binding to WEE1. Transl Cancer Res 2020, 9(2), 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westwood, I.; Cheary, D. M.; Baxter, J. E.; Richards, M. W.; van Montfort, R. L.; Fry, A. M.; Bayliss, R. Insights into the conformational variability and regulation of human Nek2 kinase. J Mol Biol 2009, 386(2), 476–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanyar, S.; Kaplan, D. D.; Deluca, J. G.; Giddings, T. H., Jr.; O’Toole, E. T.; Winey, M.; Salmon, E. D.; Casey, P. J.; Nelson, W. J.; Barth, A. I. beta-Catenin is a Nek2 substrate involved in centrosome separation. Genes Dev 2008, 22(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalkan, B. M.; Ozcan, S. C.; Cicek, E.; Gonen, M.; Acilan, C. Nek2A prevents centrosome clustering and induces cell death in cancer cells via KIF2C interaction. Cell Death & Disease. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.; Alafate, W.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Xie, W.; Bai, X.; Li, R.; Wang, M.; Wang, J. NEK2 enhances malignancies of glioblastoma via NIK/NF-κB pathway. Cell Death & Disease. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H. Y.; Wang, Y. C.; Wang, T.; Wu, W.; Cao, Y. Y.; Zhang, B. C.; Wang, M. D.; Mao, P. CCNA2 and NEK2 regulate glioblastoma progression by targeting the cell cycle. Oncol Lett 2024, 27(5), 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cheng, P.; Pavlyukov, M.; Yu, H.; Zhang, Z.; Kim, S.; Minata, M.; Mohyeldin, A.; Xie, W.; Chen, D.; et al. Targeting NEK2 attenuates glioblastoma growth and radioresistance by destabilizing histone methyltransferase EZH2. The Journal of clinical investigation 2017, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naseer, M. I.; Abdulkareem, A. A.; Muthaffar, O. Y.; Sogaty, S.; Alkhatabi, H.; Almaghrabi, S.; Chaudhary, A. G. Whole Exome Sequencing Identifies Three Novel Mutations in the ASPM Gene From Saudi Families Leading to Primary Microcephaly. Front Pediatr 2020, 8, 627122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaindl, A. M.; Passemard, S.; Kumar, P.; Kraemer, N.; Issa, L.; Zwirner, A.; Gerard, B.; Verloes, A.; Mani, S.; Gressens, P. Many roads lead to primary autosomal recessive microcephaly. Prog Neurobiol 2010, 90(3), 363–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-T.; Lee, M.-S.; Choi, J.-H.; Jung, J.-Y.; Ahn, D.-G.; Yeo, S.-Y.; Choi, D.-K.; Kim, C.-H. The microcephaly gene aspm is involved in brain development in zebrafish. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2011, 409(4), 640–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, F. Cerebral Cortex Evolution and the Gene. In eLS, 2009.

- Hornick, J. E.; Karanjeet, K.; Collins, E. S.; Hinchcliffe, E. H. Kinesins to the core: The role of microtubule-based motor proteins in building the mitotic spindle midzone. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2010, 21(3), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, W. J.; Cheng, Q.; Wen, Z. P.; Wang, J. Y.; Chen, Y. H.; Zhao, J.; Gong, Z. C.; Chen, X. P. Aberrant ASPM expression mediated by transcriptional regulation of FoxM1 promotes the progression of gliomas. J Cell Mol Med 2020, 24(17), 9613–9626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulcani-Freitas, T. M.; Saba-Silva, N.; Cappellano, A.; Cavalheiro, S.; Marie, S. K.; Oba-Shinjo, S. M.; Malheiros, S. M.; de Toledo, S. R. ASPM gene expression in medulloblastoma. Childs Nerv Syst 2011, 27(1), 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wierstra, I. The transcription factor FOXM1 (Forkhead box M1): proliferation-specific expression, transcription factor function, target genes, mouse models, and normal biological roles. Adv Cancer Res 2013, 118, 97–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, B.; Kang, S. H.; Gong, W.; Liu, M.; Aldape, K. D.; Sawaya, R.; Huang, S. Aberrant FoxM1B expression increases matrix metalloproteinase-2 transcription and enhances the invasion of glioma cells. Oncogene 2007, 26(42), 6212–6219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Tang, Y.; Huo, Q. ASPM Is a Prognostic Biomarker and Correlates With Immune Infiltration in Kidney Renal Clear Cell Carcinoma and Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 632042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bikeye, S.-N. N.; Colin, C.; Marie, Y.; Vampouille, R.; Ravassard, P.; Rousseau, A.; Boisselier, B.; Idbaih, A.; Calvo, C. F.; Leuraud, P.; et al. ASPM-associated stem cell proliferation is involved in malignant progression of gliomas and constitutes an attractive therapeutic target. Cancer Cell International 2010, 10(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. W.; Wang, H.; Sun, W.; Han, N. N.; Chen, L. ASPM is a predictor of overall survival and has therapeutic potential in endometrial cancer. Am J Transl Res, 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, T.; Jiang, X.; Bao, G.; Li, C.; Guo, C. Comprehensive Analysis of the Oncogenic Role of Targeting Protein for Xklp2 (TPX2) in Human Malignancies. Dis Markers 2022, 2022, 7571066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfaro-Aco, R.; Thawani, A.; Petry, S. Structural analysis of the role of TPX2 in branching microtubule nucleation. J Cell Biol 2017, 216(4), 983–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smertenko, A.; Clare, S. J.; Effertz, K.; Parish, A.; Ross, A.; Schmidt, S. A guide to plant TPX2-like and WAVE-DAMPENED2-like proteins. Journal of Experimental Botany 2021, 72(4), 1034–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, N.; Tulu, U. S.; Ferenz, N. P.; Fagerstrom, C.; Wilde, A.; Wadsworth, P. Poleward transport of TPX2 in the mammalian mitotic spindle requires dynein, Eg5, and microtubule flux. Mol Biol Cell 2010, 21(6), 979–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Mao, X.; Li, L.; Yang, J.; Xing, H.; Jiang, C. High TPX2 expression results in poor prognosis, and Sp1 mediates the coupling of the CX3CR1/CXCL10 chemokine pathway to the PI3K/Akt pathway through targeted inhibition of TPX2 in endometrial cancer. Cancer Medicine 2024, 13(5), e6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J. J.; Zhang, J. H.; Chen, H. J.; Wang, S. S. TPX2 promotes glioma cell proliferation and invasion via activation of the AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Lett 2016, 12(6), 5015–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Qi, X. Q.; Chen, X.; Huang, X.; Liu, G. Y.; Chen, H. R.; Huang, C. G.; Luo, C.; Lu, Y. C. Expression of targeting protein for Xenopus kinesin-like protein 2 is associated with progression of human malignant astrocytoma. Brain Res 2010, 1352, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, N.; Chu, L.; Jia, J.; Peng, S.; Gao, Y.; Yang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J. CircPOSTN/miR-361-5p/TPX2 axis regulates cell growth, apoptosis and aerobic glycolysis in glioma cells. Cancer Cell International 2020, 20(1), 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayllón, V.; O’Connor, R. PBK/TOPK promotes tumour cell proliferation through p38 MAPK activity and regulation of the DNA damage response. Oncogene 2007, 26(24), 3451–3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Zhang, J.; Shi, Y.; Wang, Z.; Nie, W.; Cai, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, X.; Lian, C. PBK correlates with prognosis, immune escape and drug response in LUAD. Scientific Reports 2023, 13(1), 20452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joel, M.; Mughal, A. A.; Grieg, Z.; Murrell, W.; Palmero, S.; Mikkelsen, B.; Fjerdingstad, H. B.; Sandberg, C. J.; Behnan, J.; Glover, J. C.; et al. Targeting PBK/TOPK decreases growth and survival of glioma initiating cells in vitro and attenuates tumor growth in vivo. Mol Cancer 2015, 14, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Fan, W.; Fang, S. PBK as a Potential Biomarker Associated with Prognosis of Glioblastoma. J Mol Neurosci 2020, 70(1), 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinyama, H. A.; Wei, L.; Mokgautsi, N.; Lawal, B.; Wu, A. T. H.; Huang, H.-S. Identification of CDK1, PBK, and CHEK1 as an Oncogenic Signature in Glioblastoma: A Bioinformatics Approach to Repurpose Dapagliflozin as a Therapeutic Agent. In International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2023; Vol. 24.

- Deng, Y.; Wen, H.; Yang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Bi, Y.; Wang, P.; Zhou, M.; Guan, J.; Zhang, W.; et al. Identification of PBK as a hub gene and potential therapeutic target for medulloblastoma. Oncol Rep 2022, 48(1), 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Yin, L.; Ma, L.; Yang, J.; Yang, F.; Sun, B.; Nianzeng, X. Comprehensive bioinformatics analysis of ribonucleoside diphosphate reductase subunit M2(RRM2) gene correlates with prognosis and tumor immunotherapy in pan-cancer. Aging (Albany NY), 7890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolmusz, V. K.; Karászi, K.; Micsik, T.; Tóth, E. A.; Mészáros, K.; Karvaly, G.; Barna, G.; Szabó, P. M.; Baghy, K.; Matkó, J.; et al. Cell cycle dependent RRM2 may serve as proliferation marker and pharmaceutical target in adrenocortical cancer. Am J Cancer Res, 2041. [Google Scholar]

- Zuo, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Chang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L. Ribonucleotide reductase M2 (RRM2): Regulation, function and targeting strategy in human cancer. Genes Dis 2024, 11(1), 218–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Contreras, A. J.; Specks, J.; Barlow, J. H.; Ambrogio, C.; Desler, C.; Vikingsson, S.; Rodrigo-Perez, S.; Green, H.; Rasmussen, L. J.; Murga, M.; et al. Increased Rrm2 gene dosage reduces fragile site breakage and prolongs survival of ATR mutant mice. Genes Dev 2015, 29(7), 690–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T.; Maeda, D.; Kume, H.; Homma, Y.; Fukayama, M. Ribonucleotide reductase M2 subunit is a novel diagnostic marker and a potential therapeutic target in bladder cancer. Histopathology 2010, 57(6), 885–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, B.; Xue, L.; Yen, F.; Chu, P.; Un, F.; Yen, Y. Ribonucleotide reductase subunits M2 and p53R2 are potential biomarkers for metastasis of colon cancer. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2007, 6(5), 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A.; Amin, A. R.; Wang, D.; Koenig, L.; Nannapaneni, S.; Chen, Z.; Wang, Z.; Sica, G.; Deng, X.; Chen, Z. G.; et al. RRM2 regulates Bcl-2 in head and neck and lung cancers: a potential target for cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res 2013, 19(13), 3416–3428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Zhang, H.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, J.; Yang, Z.; Wei, C.; Xu, T.; Yu, Z.; et al. RRM2 is a potential prognostic biomarker with functional significance in glioma. Int J Biol Sci 2019, 15(3), 533–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, P.; Dugoua, J. J.; Eyawo, O.; Mills, E. J. Traditional Chinese Medicines in the treatment of hepatocellular cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 2009, 28(1), 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrales-Guerrero, S.; Cui, T.; Castro-Aceituno, V.; Yang, L.; Nair, S.; Feng, H.; Venere, M.; Yoon, S.; DeWees, T.; Shen, C.; et al. Inhibition of RRM2 radiosensitizes glioblastoma and uncovers synthetic lethality in combination with targeting CHK1. Cancer Letters 2023, 570, 216308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, J.; Chen, S.; Huang, B.; Li, G.; Feng, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, S. RRM2 promotes the progression of human glioblastoma. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2018, 233(10), 6759–6767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirokawa, N.; Tanaka, Y. Kinesin superfamily proteins (KIFs): Various functions and their relevance for important phenomena in life and diseases. Exp Cell Res 2015, 334(1), 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sebastian, J.; Rathinasamy, K. Benserazide Perturbs Kif15-kinesin Binding Protein Interaction with Prolonged Metaphase and Defects in Chromosomal Congression: A Study Based on in silico Modeling and Cell Culture. Mol Inform 2020, 39(3), e1900035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanneste, D.; Takagi, M.; Imamoto, N.; Vernos, I. The role of Hklp2 in the stabilization and maintenance of spindle bipolarity. Curr Biol 2009, 19(20), 1712–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florian, S.; Mayer, T. U. Modulated microtubule dynamics enable Hklp2/Kif15 to assemble bipolar spindles. Cell Cycle 2011, 10(20), 3533–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Han, B.; Huang, W.; Qi, C.; Liu, F. Identification of KIF15 as a potential therapeutic target and prognostic factor for glioma. Oncol Rep 2020, 43(4), 1035–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Q. Kinesin family member 15 can promote the proliferation of glioblastoma. Math Biosci Eng 2022, 19(8), 8259–8272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessop, M.; Felix, J.; Gutsche, I. AAA+ ATPases: structural insertions under the magnifying glass. Curr Opin Struct Biol 2021, 66, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapier, C. R.; Iwasa, J.; Cairns, B. R.; Peterson, C. L. Mechanisms of action and regulation of ATP-dependent chromatin-remodelling complexes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017, 18(7), 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, H.; Li, L.; Dong, X.; Ru, X.; Fan, X.; Wen, T.; Liu, J. ATAD2 predicts poor outcomes in patients with ovarian cancer and is a marker of proliferation. Int J Oncol 2020, 56(1), 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, T.; Yu, J. Silencing METTL3 inhibits the proliferation and invasion of osteosarcoma by regulating ATAD2. Biomed Pharmacother 2020, 125, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; He, Z.; Hao, Y.; Liu, B.; Yao, D. ATPase family AAA domain-containing protein 2 (ATAD2): From an epigenetic modulator to cancer therapeutic target. Theranostics 2023, 13(2), 787–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zuo, J.; Wang, M.; Ma, X.; Gao, K.; Bai, X.; Wang, N.; Xie, W.; Liu, H. Polo-like kinase�4 promotes tumorigenesis and induces resistance to radiotherapy in glioblastoma. Oncology Reports 2019, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wen, Q.; Yan, S.; Zeng, W.; Zou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Zou, J.; Zou, X. Tumor-Promoting ATAD2 and Its Preclinical Challenges. Biomolecules. [CrossRef]

- Vidyadharan, S.; Prabhakar Rao, B.; Perumal, Y.; Chandrasekharan, K.; Rajagopalan, V. Deep Learning Classifies Low- and High-Grade Glioma Patients with High Accuracy, Sensitivity, and Specificity Based on Their Brain White Matter Networks Derived from Diffusion Tensor Imaging. Diagnostics (Basel). [CrossRef]

- Duffau, H. White Matter Tracts and Diffuse Lower-Grade Gliomas: The Pivotal Role of Myelin Plasticity in the Tumor Pathogenesis, Infiltration Patterns, Functional Consequences and Therapeutic Management. Front Oncol 2022, 12, 855587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piñeros, M.; Sierra, M. S.; Izarzugaza, M. I.; Forman, D. Descriptive epidemiology of brain and central nervous system cancers in Central and South America. Cancer Epidemiology 2016, 44, S141–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claus, E. B.; Walsh, K. M.; Wiencke, J. K.; Molinaro, A. M.; Wiemels, J. L.; Schildkraut, J. M.; Bondy, M. L.; Berger, M.; Jenkins, R.; Wrensch, M. Survival and low-grade glioma: the emergence of genetic information. Neurosurg Focus 2015, 38(1), E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noiphithak, R.; Veerasarn, K. Clinical predictors for survival and treatment outcome of high-grade glioma in Prasat Neurological Institute. Asian J Neurosurg 2017, 12(1), 28–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).