Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

25 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Heterocyclic ring modifications. Incorporating heterocyclic rings, such as pyridine, piperazine, triazole, imidazole, or oxazole, in conjunction with the tetrazole moiety, can modulate antifungal activity and selectivity.

- Substitution pattern on the tetrazole ring. Generally, electron-withdrawing substituents such as halogens, trifluoromethyl or nitro groups, on the tetrazole ring or adjacent aromatic rings tends to enhance antifungal activity.

- Aryl substituents. Electron-rich aryl or hetaryl groups are often preferred.

- Steric effects. The introduction of bulky substituents, such as cyclohexyl or benzyl groups, can improve selectivity towards fungal cells over mammalian cells.

- Linker chain length and flexibility. The length and flexibility of the linker chain between the tetrazole moiety and other functional groups can improve the binding affinity to the target enzyme or receptor.

- Hydrophobicity and lipophilicity. Moderate hydrophobicity and lipophilicity of the tetrazole derivatives can enhance their ability to penetrate the fungal cell membrane and reach their target site: long undecyl chain, phenyl rings, etc. However, excessive hydrophobicity or lipophilicity may lead to poor solubility and bioavailability issues.

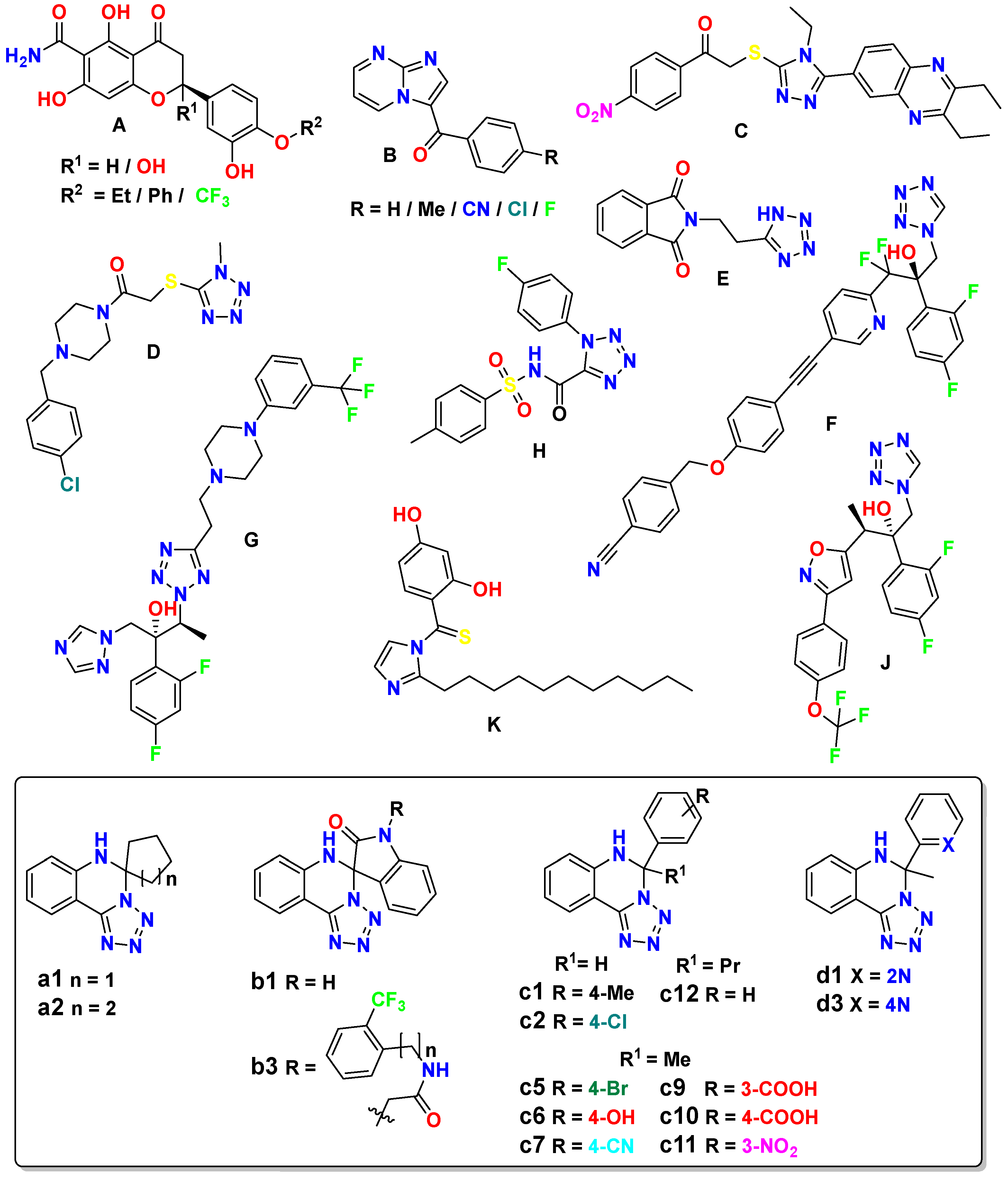

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Antifungal Studies

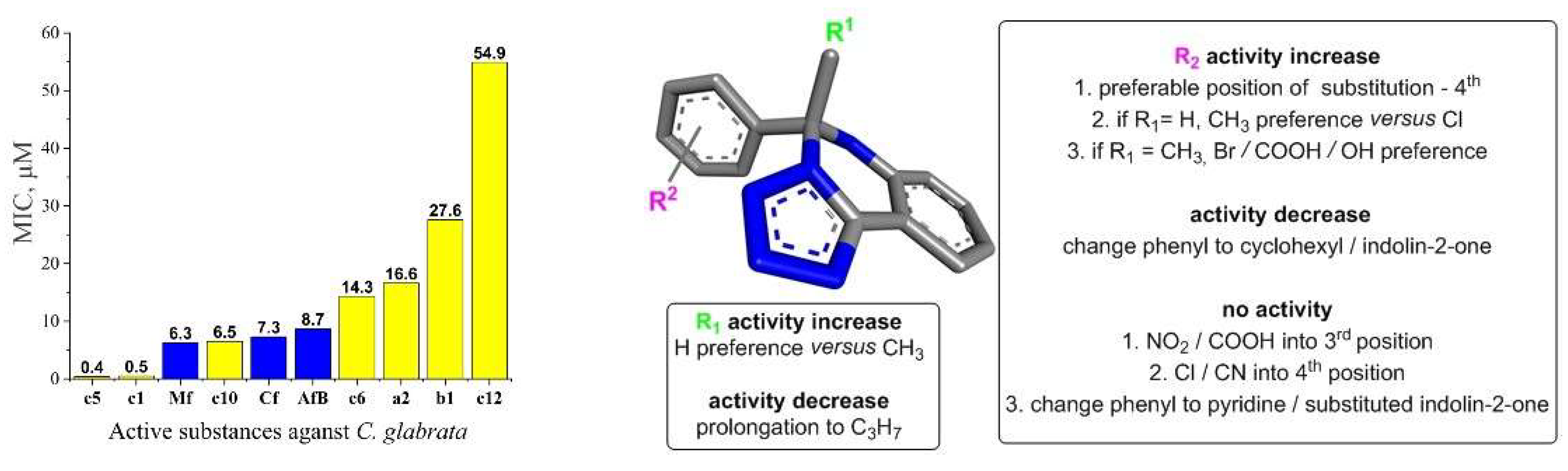

2.3. Antifungal Studies

- R1 alkyl prolongation: extending the alkyl chain from methyl to propyl may introduce unfavorable steric clashes or conformational restrictions, leading to decreased activity.

- 4th Position substitution of phenyl ring: the preference for substitution at the 4th position over other positions on the bicyclic ring system suggests, that the steric and electronic environment at this specific site is optimal for binding to the target enzyme. Substituents at this position may participate in critical interactions like hydrogen bonding, π-stacking, or filling a hydrophobic pocket. Besides the presence of aromatic moiety in these compounds increased hydrophobicity, which improves their permeability into the cell membrane, therefore enhancing the antifungal activity.

- CH3 vs. Cl when R1 = H: the preference for a methyl group over chloro, when R1 is unsubstituted could be attributed to the more lipophilic nature of the methyl substituent, and to steric factors, where the smaller hydrogen atom allows for better accommodation, and binding within the target pocket. The chloro group, being larger and more electronegative, may experience unfavorable steric clashes or result in suboptimal binding interactions.

- Br/COOH/OH vs. CN when R1 = methyl: the preference for bromo, carboxyl, or hyd-roxyl substituents over a cyano group at R2 suggests, that the electron-withdrawing nature of the groups may be disfavored. The electron-rich bromine, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups could form favorable hydrogen bonding or ionic interactions with the target.

- Change from phenyl to cyclohexyl or indolin-2-one substituents: this structural modification leads to a decrease in the biological activity, potentially indicating that the size of the rings is important for the desired activity.

- NO2 / COOH substitution into the 3rd position: the introduction of strongly electron-withdrawing nitro or carboxyl groups at the 3rd position may significantly alter the electronic distribution and potentially disrupt crucial binding interactions, leading to a complete loss of activity.

- Cl substitution into the 4th position: Similar to the 3rd position substitution, placing a chloro group at the 4th position of the R2 phenyl ring also leads to a complete lack of activity. This indicates that the specific substitution pattern on the phenyl ring is essential for the compound to exhibit the desired a antifungal effects.

- Change from phenyl to pyridine or substituted indolin-2-one: similar to the cyclohexyl and indolin-2-one modifications, changing the phenyl ring to a pyridine or substituted indolin-2-one moiety likely disrupts essential aromatic interactions or introduces steric hindrances, leading to a complete loss of activity.

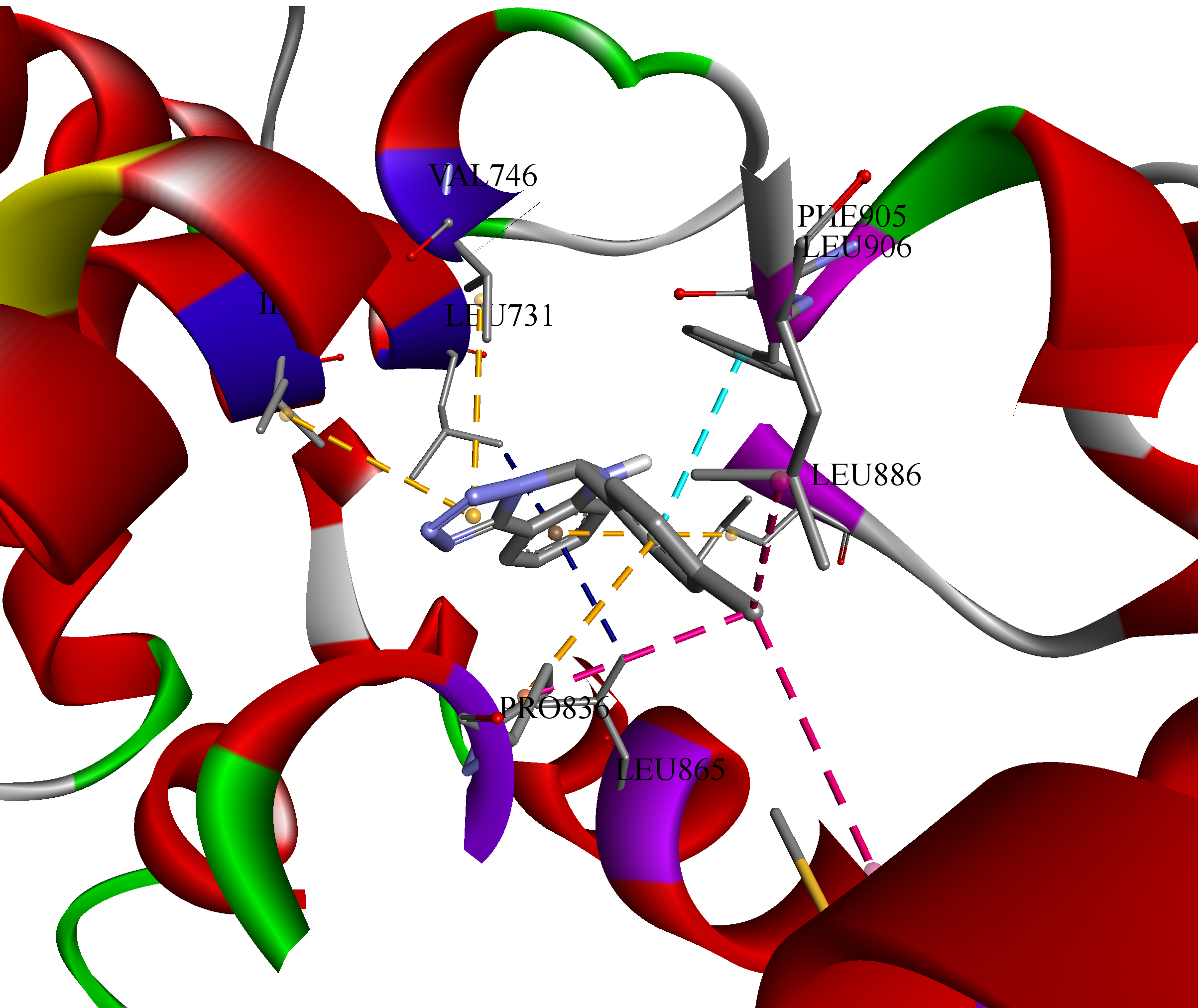

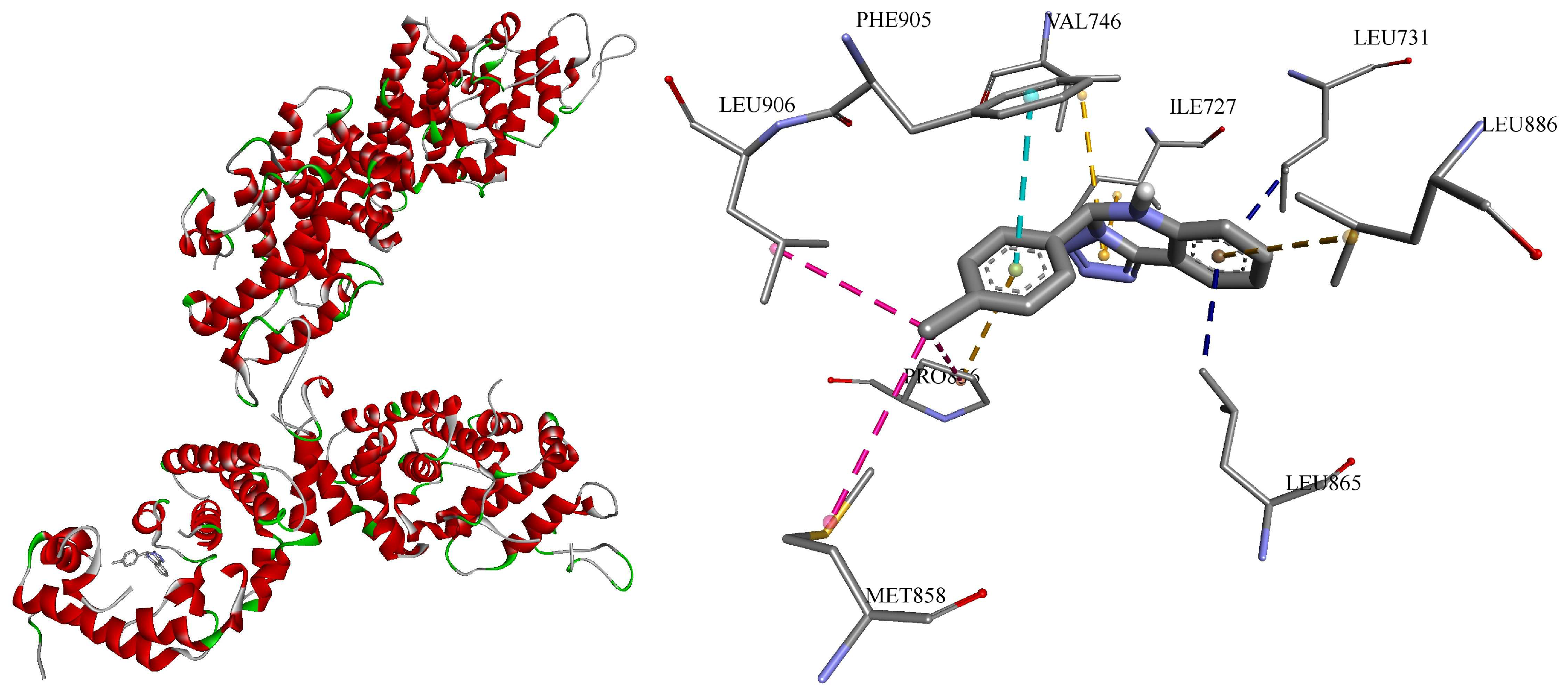

2.4. Molecular Docking

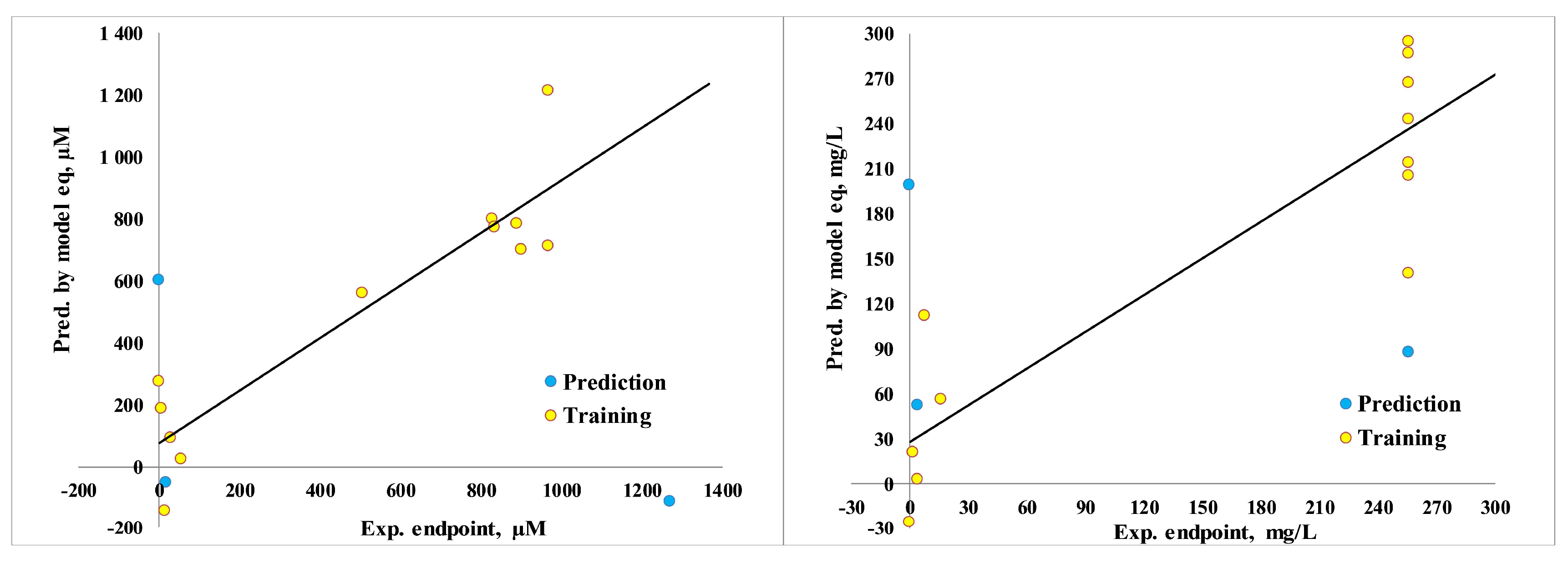

2.5. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship

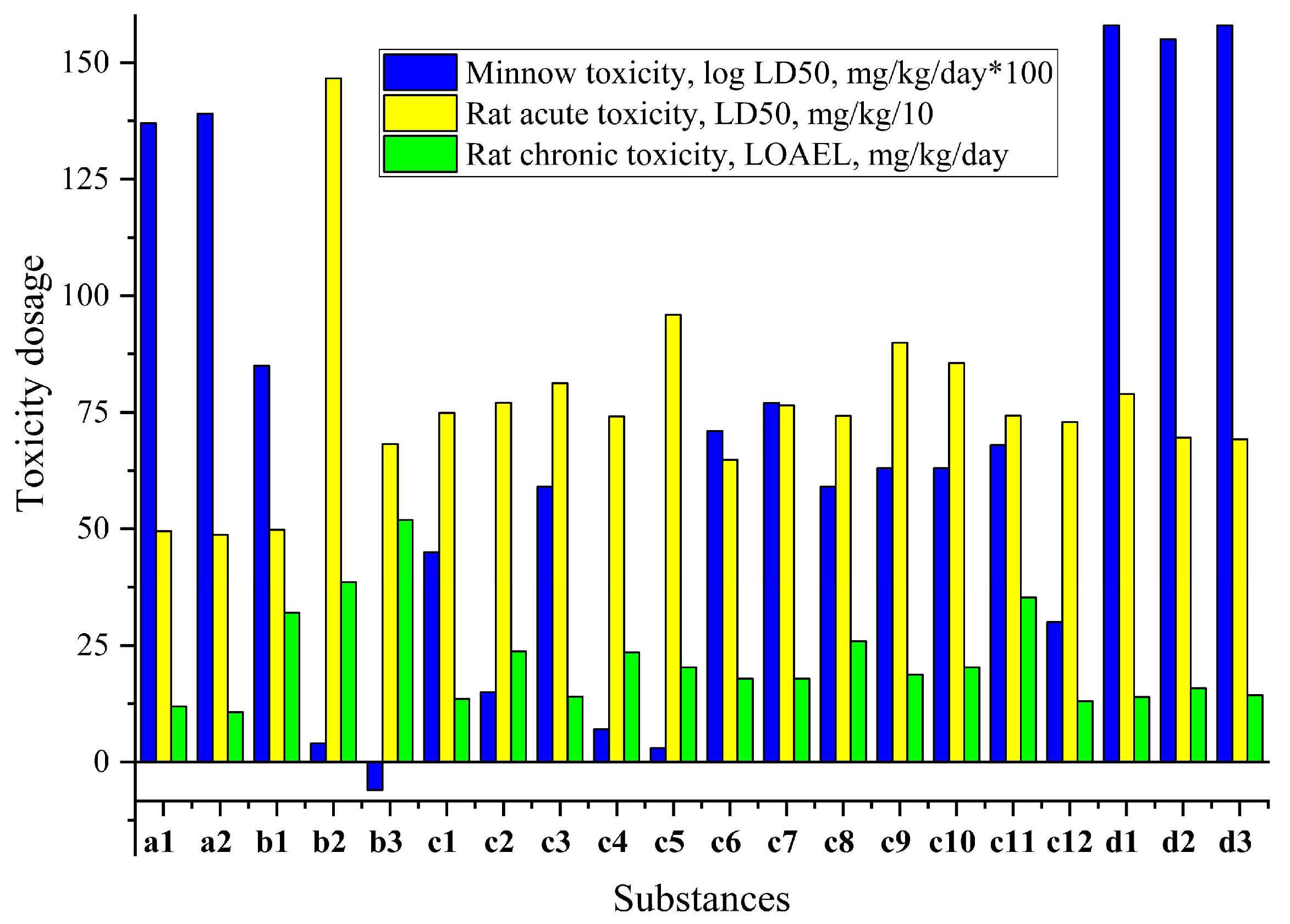

2.6. Toxicity Prediction

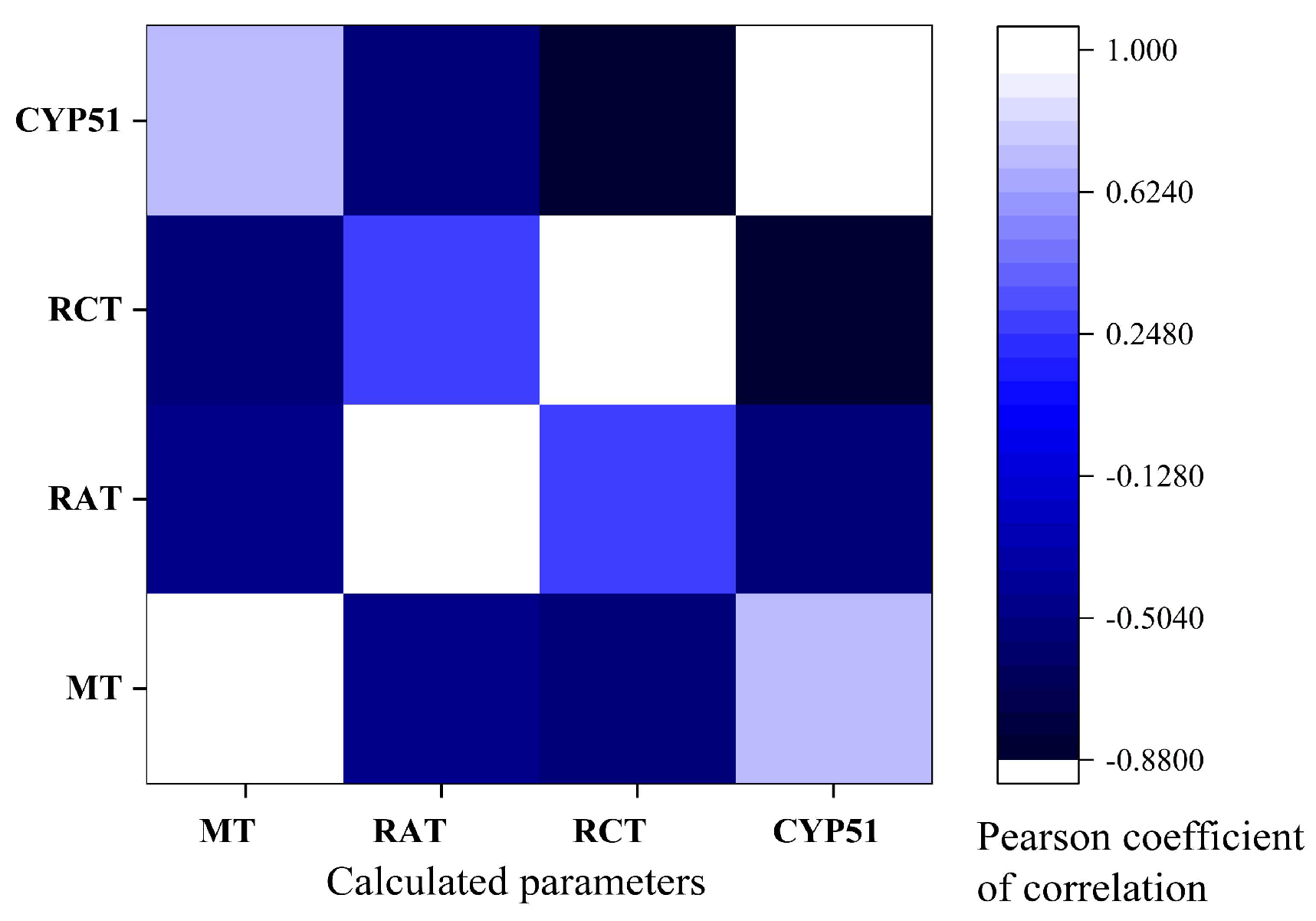

2.7. Pearson Correlations

3. Conclusions

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Synthesis

4.1.1. General

4.1.2. Synthesis of the c11 and c12

4.2. Antifungal Studies

4.3. Molecular Docking Studies

4.4. QSAR Modeling

4.5. Toxicity Studies

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anderson, H.W. Yeast-Like Fungi of the Human Intestinal Tract. J. Infect. Dis. 1917, 21, 341–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, K.C. New and Emerging Yeast Pathogens. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1995, 8, 462–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Lionakis, M.S.; Arendrup, M.C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Kullberg, B.J. Invasive Candidiasis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2018, 4, 18026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, P.; Motherway, C.; Powell, J.; Elsaka, A.; Sheikh, A.A.; Jahangir, A.; O’Connell, N.H.; Dunne, C.P. Candidaemia in an Irish Intensive Care Unit Setting between 2004 and 2018 Reflects Increased Incidence of Candida glabrata. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 102, 347–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gülmez, D.; Sığ, A.K.; Akar, N.; Duyan, S.; Arıkan Akdağlı, S. Changing Trends in Isolation Frequencies and Species of Clinical Fungal Strains: What Do the 12-Years (2008-2019) Mycology Laboratory Data Tell About? Mikrobiyol. Bul. 2021, 55, 53–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, M.A.; Melo, A.P.; Bento, A.D.; Souza, L.B.; Neto, F.D.; Garcia, J.B.; Zuza-Alves, D.L.; Francisco, E.C.; Melo, A.S.; Chaves, G.M. Epidemiology and Prognostic Factors of Nosocomial Candidemia in Northeast Brazil: A Six-Year Retrospective Study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0221033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, C.F.; Silva, S.; Henriques, M. Candida glabrata: A Review of Its Features and Resistance. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 33, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domagk, D.; Bisping, G.; Poremba, C.; Fegeler, W.; Domschke, W.; Menzel, J. Common Bile Duct Obstruction Due to Candidiasis. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2001, 36, 444–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, Z.; Abolhasani, H.; Mirjafary, Z.; Najafi, G.; Heidari, F. Efficient Synthesis, Molecular Docking and ADMET Studies of New 5-Substituted Tetrazole Derivatives. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1277, 134867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Break, T.J.; Desai, J.V.; Healey, K.R.; Natarajan, M.; Ferre, E.M.N.; Henderson, C.; Zelazny, A.; Siebenlist, U.; Cohen, O.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P.; Lionakis, M.S. VT-1598 Inhibits the In Vitro Growth of Mucosal Candida Strains and Protects Against Fluconazole-Susceptible and -Resistant Oral Candidiasis in IL-17 Signaling-Deficient Mice. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 2089–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleveland, A.A.; Harrison, L.H.; Farley, M.M.; Hollick, R.; Stein, B.; Chiller, T.M.; Lockhart, S.R.; Park, B.J. Declining Incidence of Candidemia and the Shifting Epidemiology of Candida Resistance in Two US Metropolitan Areas, 2008-2013: Results from Population-Based Surveillance. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C.; Arikan-Akdagli, S.; Jørgensen, K.M.; Barac, A.; Steinmann, J.; Toscano, C.; Hoenigl, M. European Candidaemia Is Characterized by Notable Differential Epidemiology and Susceptibility Pattern: Results from the ECMM Candida III Study. J. Infect. 2023, 87, 428–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.S.; Lee, S.S.; Chen, W.C.; Tseng, C.H.; Lee, N.Y.; Chen, P.L.; Li, M.C.; Syue, L.S.; Lo, C.L.; Ko, W.C.; Hung, Y.P. COVID-19-Associated Candidiasis and the Emerging Concern of Candida Auris Infections. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2023, 56, 672–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malani, A.N.; Psarros, G.; Malani, P.N.; Kauffman, C.A. Is Age a Risk Factor for Candida glabrata Colonisation? Mycoses 2011, 54, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-García, O.; Andrade-Pavón, D.; Campos-Aldrete, E.; Ballinas-Indilí, R.; Méndez-Tenorio, A.; Villa-Tanaca, L.; Álvarez-Toledano, C. Synthesis, Molecular Docking, and Antimycotic Evaluation of Some 3-Acyl Imidazo[1,2-a]pyrimidines. Molecules 2018, 23, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmaniye, D.; Baltacı Bozkurt, N.; Levent, S.; Benli Yardımcı, G.; Sağlık, B.N.; Ozkay, Y.; Kaplancıklı, Z.A. Synthesis, Antifungal Activities, Molecular Docking and Molecular Dynamic Studies of Novel Quinoxaline-Triazole Compounds. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 24573–24585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Çevik, A.U.; Celik, I.; Işık, A.; Gül, Ü.D.; Bayazıt, G.; Bostancı, H.E.; Özkay, Y.; Kaplancıklı, Z.A. Synthesis, and Docking Studies of Novel Tetrazole-S-Alkyl Derivatives as Antimicrobial Agents. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2023, 198, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atalay, E.V.; Asar, S. Determination of the Inhibition Effect of Hesperetin and Its Derivatives on Candida glabrata by Molecular Docking Method. Eur. Chem. Biotechnol. J. 2024, 1, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Groot, P.W.; Kraneveld, E.A.; Yin, Q.Y.; Dekker, H.L.; Groß, U.; Crielaard, W.; de Koster, C.G.; Bader, O.; Klis, F.M.; Weig, M. The Cell Wall of the Human Pathogen Candida glabrata: Differential Incorporation of Novel Adhesin-Like Wall Proteins. Eukaryot. Cell 2008, 7, 1951–1964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afsarian, M.H.; Farjam, M.; Zarenezhad, E.; Behrouz, S.; Rad, M.N.S. Synthesis, Antifungal Evaluation and Molecular Docking Studies of Some Tetrazole Derivatives. Acta Chim. Slov. 2019, 66, 874–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upadhayaya, R.S.; Sinha, N.; Jain, S.; Kishore, N.; Chandra, R.; Arora, S.K. Optically Active Antifungal Azoles: Synthesis and Antifungal Activity of (2R,3S)-2-(2,4-Difluorophenyl)-3-(5-[2-[4-aryl-piperazin-1-yl]-ethyl]-tetrazol-2-yl/1-yl)-1-[1,2,4]-triazol-1-yl-butan-2-ol. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004, 12, 2225–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selvarasu, S.; Srinivasan, P.; Mannathusamy, G.; Maria Susai, B. Synthesis, Characterization, in Silico Molecular Modeling, Anti-Diabetic and Antimicrobial Screening of Novel 1-Aryl-N-tosyl-1H-tetrazole-5-carboxamide Derivatives. Chem. Data Collect. 2021, 32, 100648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, L.; Antypenko, O.; Karnaukh, I.; Rebets, O.; Kovalenko, S.; Arisawa, M. 5,6-Dihydrotetrazolo[1,5-c]Quinazolines: Toxicity Prediction, Synthesis, Antimicrobial Activity, Molecular Docking and Perspectives. Arch. Pharm. 2023, 356, e2300029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, T.; Chi, X.; Xie, F.; Li, L.; Wu, H.; Hao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, Y. Design, Synthesis, and Evaluation of Novel Tetrazoles Featuring Isoxazole Moiety as Highly Selective Antifungal Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2024, 246, 115007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matysiak, J.; Niewiadomy, A.; Krajewska-Kułak, E.; Mącik-Niewiadomy, G. Synthesis of Some 1-(2,4-Dihydroxythiobenzoyl)Imidazoles, -Imidazolines and -Tetrazoles and Their Potent Activity Against Candida Species. Il Farmaco 2003, 58, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shantal, C.N.; Juan, C.C.; Sánchez, L.B.; Jerónimo, C.H.; Benitez, E.G. Candida glabrata is a Successful Pathogen: an Artist Manipulating the Immune Response. Microbiol. Res. 2022, 260, 127038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frías-De-León, M.G.; Hernández-Castro, R.; Conde-Cuevas, E.; García-Coronel, I.H.; Vázquez-Aceituno, V.A.; Soriano-Ursúa, M.A.; Farfán-García, E.D.; Ocharán-Hernández, E.; Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C.; Arenas, R.; Robledo-Cayetano, M.; Ramírez-Lozada, T.; Meza-Meneses, P.; Pinto-Almazán, R.; Martínez-Herrera, E. Candida glabrata Antifungal Resistance and Virulence Factors, a Perfect Pathogenic Combination. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.V.G.; Nguyen, H.H.N.; Vo, T.H.; Le, M.T.; Tran-Nguyen, V.K.; Vu, T.T.; Nguyen, P.V. Prevalence and Drug Susceptibility of Clinical Candida Species in Nasopharyngeal Cancer Patients in Vietnam. One Health 2023, 18, 100659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whaley, S.G. Contributions of the Major C. glabrata Triazole Resistance Determinants to the Novel Investigational Tetrazoles VT-1598 and VT-1161. Available online: https://doi.org/10.26226/morressier.5ac39997d462b8028d89a2ae. (accessed on 27 April 2024).

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, H.P.; Tran, B.H.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Garvey, E.P. Fungal-Specific Cyp51 Inhibitor VT1598 Demonstrates In Vitro Activity Against Candida and Cryptococcus Species, Endemic Fungi, Including Coccidioides Species, Aspergillus Species and Rhizopus arrhizus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 404–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Q.; Wu, X.; Su, T.; Jiang, C.; Dong, D.; Wang, D.; Chen, W.; Cui, Y.; Peng, Y. The Regulatory Subunits of CK2 Complex Mediate DNA Damage Response and Virulence in Candida Glabrata. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waseem, M.; Das, S.; Mondal, D.; Jain, M.; Thakur, J.K.; Subbarao, N. Identification of Novel Inhibitors Against Med15a KIX Domain of Candida glabrata. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 126720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, A.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, R.; Wei, J.; Cui, Y.; Cao, X.; Yang, Y. Design, Synthesis, and Structure-Activity Relationship Studies of Novel Tetrazole Antifungal Agents with Potent Activity, Broad Antifungal Spectrum and High Selectivity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 5741–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, C.; Zhang, W.; Ji, H.; Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; Xu, H.; Zhu, J.; Miao, Z.; Jiang, Q.; Yao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, J.; Lü, J. Structure-Based Optimization of Azole Antifungal Agents by CoMFA, CoMSIA, and Molecular Docking. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 2512–2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrade-Pavón, D.; Sánchez-Sandoval, E.; Tamariz, J.; Ibarra, J.A.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C.; Villa-Tanaca, L. Inhibitors of 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl Coenzyme A Reductase Decrease the Growth, Ergosterol Synthesis and Generation of petite Mutants in Candida glabrata and Candida albicans. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warrilow, A.G.; Hull, C.M.; Parker, J.E.; Garvey, E.P.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Moore, W.R.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. The Clinical Candidate VT-1161 is a Highly Potent Inhibitor of Candida albicans CYP51 but Fails to Bind the Human Enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 7121–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łukowska-Chojnacka, E.; Kowalkowska, A.; Gizińska, M.; Koronkiewicz, M.; Staniszewska, M. Synthesis of Tetrazole Derivatives Bearing Pyrrolidine Scaffold and Evaluation of Their Antifungal Activity Against Candida albicans. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 164, 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reithofer, V.; Fernandez-Pereira, J.; Alvarado, M.; de Groot, P.; Essen, L.O. A Novel Class of Candida glabrata Cell Wall Proteins with Beta-Helix Fold Mediates Adhesion in Clinical Isolates. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Yang, N.; Li, W.; Peng, X.; Dong, J.; Jiang, Y.; Yan, L.; Zhang, D.; Jin, Y. Exploration of Baicalein-Core Derivatives as Potent Antifungal Agents: SAR and Mechanism Insights. Molecules 2023, 28, 6340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondaryk, M.; Łukowska-Chojnacka, E.; Staniszewska, M. Tetrazole Activity against Candida albicans. The Role of KEX2 Mutations in the Sensitivity to (±)-1-[5-(2-Chlorophenyl)-2H-tetrazol-2-yl]propan-2-yl Acetate. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 2657–2663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-López, N.A.; Aguayo-Ortiz, R.; Cuéllar-Cruz, M. Molecular Modeling of the Phosphoglycerate Kinase and Fructose-Bisphosphate Aldolase Proteins from Candida glabrata and Candida albicans. Med. Chem. Res. 2023, 32, 2356–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvvadi, P.R.; Lamoth, F.; Steinbach, W.J. Calcineurin as a Multifunctional Regulator: Unraveling Novel Functions in Fungal Stress Responses, Hyphal Growth, Drug Resistance, and Pathogenesis. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2014, 28, 56–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryder, N.S. Terbinafine: Mode of Action and Properties of the Squalene Epoxidase Inhibition. Br. J. Dermatol. 1992, 126, 2–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschart, A.; Gremmer, K.; El-Mowafy, M.; van den Heuvel, J.; Mueller, P.P.; Bilitewski, U. A Novel Functional Assay for Fungal Histidine Kinases Group III Reveals the Role of HAMP Domains for Fungicide Sensitivity. J. Biotechnol. 2012, 157, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yau, K.P.S.; Weerasinghe, H.; Olivier, F.A.B.; Lo, T.L.; Powell, D.R.; Koch, B.; Beilharz, T.H.; Traven, A. The Proteasome Regulator Rpn4 Controls Antifungal Drug Tolerance by Coupling Protein Homeostasis with Metabolic Responses to Drug Stress. PLoS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, D.J.; Kim, J.G.; Won, K.J.; Kim, B.; Shin, H.C.; Park, J.Y.; Bae, Y.M. Blockade of K+ and Ca2+ channels by azole antifungal agents in neonatal rat ventricular myocytes. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2012, 35, 1469–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Li, T.; Yu, C.; Sun, S. Candida albicans Heat Shock Proteins and HSPS-Associated Signaling Pathways as Potential Antifungal Targets. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caplan, T.; Lorente-Macías, Á.; Stogios, P.J.; Evdokimova, E.; Hyde, S.; Wellington, M.A.; Liston, S.; Iyer, K.R.; Puumala, E.; Shekhar-Guturja, T.; Robbins, N.; Savchenko, A.; Krysan, D.J.; Whitesell, L.; Zuercher, W.J.; Cowen, L.E. Overcoming Fungal Echinocandin Resistance through Inhibition of the Non-Essential Stress Kinase YCK2. Cell Chem. Biol. 2020, 27, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, O.; Antypenko, L.; Kalnysh, D.; Kovalenko, S. ADME Properties Prediction of 5-Phenyl-5,6-Dihydrotetrazolo[1,5-c]Quinazolines. Grail Sci. 2022, 12-13, 684–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, O.; Antypenko, L.; Kalnysh, D.; Kovalenko, S. Molecular Docking of 5-Phenyl-5,6-Dihydrotetrazolo[1,5-c]Quinazolines to Ribosomal 50S Protein L2P (2QEX). Grail Sci. 2022, 12-13, 693–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, O.; Antypenko, L.; Rebets, O.; Kovalenko, S. Molecular Docking of 5-Phenyl-5,6-Dihydrotetrazolo[1,5-c]Quinazolines to Penicillin-Binding Protein 2X (PBP 2X) and Preliminary Results of Antifungal Activity. Grail Sci. 2022, 14-15, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, L.; Antypenko, O.; Fominichenko, A.; Karnaukh, I. Antifungal Activity of 5,6-Dihydrotetrazolo[1,5-c]Quinazoline Derivative against Several Candida Species. In Proceedings of the VI International Scientific and Practical Conference Theoretical and Empirical Scientific Research: Concept and Trends, Oxford, United Kingdom; 2024; pp. 416–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular Docking: A Powerful Approach for Structure-Based Drug Discovery. CCADD 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CB-Dock2. Cavity Detection Guided Blind Docking. Available online: https://cadd.labshare.cn/cb-dock2/index.php (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Gan, J.; Chen, S.; Xiao, Z.X.; Cao, Y. CB-Dock2: Improved Protein–Ligand Blind Docking by Integrating Cavity Detection, Docking and Homologous Template Fitting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W159–W164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- RCSB Protein Data Bank (RCSB PDB). Available online: https://www.rcsb.org/ (accessed on 22 April 2024).

- Roetzer, A.; Gabaldón, T.; Schüller, C. From Saccharomyces cerevisiae to Candida glabrata in a Few Easy Steps: Important Adaptations for an Opportunistic Pathogen. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2011, 314, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DockRMSD. Docking Pose Distance Calculation. Available online: https://seq.2fun.dcmb.med.umich.edu//DockRMSD (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Bell, E.W.; Zhang, Y. DockRMSD: An Open-Source Tool for Atom Mapping and RMSD Calculation of Symmetric Molecules through Graph Isomorphism. J. Cheminform. 2019, 11, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherkasov, A.; Muratov, E.N.; Fourches, D.; Varnek, A.; Baskin, I.I.; Cronin, M.; Tropsha, A. QSAR Modeling: Where Have You Been? Where Are You Going To? J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 4977–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramatica, P. Principles of QSAR Modeling. IJQSPR 2020, 5, 61–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gramatica, P.; Cassani, S.; Chirico, N. QSARINS-Chem: Insubria Datasets and New QSAR/QSPR Models for Environmental Pollutants in QSARINS. J. Comput. Chem. 2014, 35, 1036–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todeschini, R.; Consonni, V. Handbook of Molecular Descriptors; Mannhold, R. , Kubinyi, H., Timmerman, H., Eds.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, New York, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tropsha, A. Best Practices for QSAR Model Development, Validation, and Exploitation. Mol. Inform. 2010, 29, 476–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CropCSM: Identifying Safe and Potent Herbicides. Available online: https://biosig.lab.uq.edu.au/crop_csm/prediction (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Douglas, E.V.; Pires, D.E.V.; Stubbs, K.A.; Mylne, J.S.; Ascher, D.B. CropCSM: Designing Safe and Potent Herbicides with Graph-Based Signatures. Brief. Bioinform. 2022, 23, bbac042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antypenko, L.; Rebets, O.; Karnaukh, I.; Antypenko, O.; Kovalenko, S. Step-by-Step Method for the Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration of a Hydrophobic Biologically Active Substance by the Broth Dilution Method. Grail Sci. 2022, 17, 468–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gramatica, P.; Chirico, N. QSARINS-chem: Insubria Datasets and New QSAR/QSPR Models for Environmental Pollutants in QSARINS. J. Comput. Chem. 2013, 34, 2121–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Substance | Minimum inhibition concentration (64 – 0.125 mg/L), concentration of substance (μM) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.125 | |

| c1 | -* | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.47 |

| c5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.37 |

| c10 | - | - | - | - | - | 6.50 | + | + | + | + |

| a2 | - | - | - | - | 16.58 | + | + | + | + | + |

| c6 | - | - | - | - | 14.32 | + | + | + | + | + |

| b1 | - | - | - | 27.56 | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| c12 | - | - | 54.91 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

|

a1, b3, c2, c7, с9, c11, d1, d3 |

+ | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Growth control | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2.5% DMSO control | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sterility control | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| *Absence (−) / presence (+) of opalescence. Minimum inhibition concentration of references: amphotericin B: 8 mg/L (8.66 μM), caspofungin: 8 mg/L (7.32 μM), and micafungin: 4 mg/L (6.30 μM). Repeated twice. | ||||||||||

| # | Strain* | Classification | Molecule ID | PDB ID** | # | Vina Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SC S288C | transcription | sterol uptake control protein 2 | 4N9N | c1 | -9.6 |

| c5 | -9.9 | |||||

| 2 | NG CBS138 | transcription | sterol uptake control protein 2 | 7VPR | c1 | -10.4 |

| c5 | -7.9 | |||||

| 3 | CA | oxidoreductase / oxidoreductase inhibitor |

sterol 14-alpha demethylase | 5TZ1 | c1 | -10.2 |

| c5 | -9.2 | |||||

| 4 | NG CBS138 | oxidoreductase / oxidoreductase inhibitor |

lanosterol 14-alpha demethylase | 5JLC | c1 | -9.6 |

| c5 | -8.8 | |||||

| 5 | NG CBS138 | oxidoreductase / oxidoreductase inhibitor |

dihydrofolate reductase | 4HOG | c1 | -8.5 |

| c5 | -7.9 | |||||

| 6 | NG | oxidoreductase / oxidoreductase inhibitor |

NADPH-dependent methylglyoxal reductase GRE2 |

7YMU | c1 | -8.1 |

| c5 | -8.2 | |||||

| 7 | CA | hydrolase | exo-b-(1,3)-glucanase | 1EQP | c1 | -9.6 |

| c5 | -9.7 | |||||

| 8 | NG CBS138 | sugar binding protein | 4-alpha-glucanotransferase | 7EKU | c1 | -9.5 |

| c5 | -9.2 | |||||

| 9 | NG CBS138 | carbohydrate | 1,4-alpha-glucan-branching enzyme | 7P43 | c1 | -9.3 |

| c5 | -8.8 | |||||

| 10 | NG CBS138 | cell adhesion | adhesin-like wall protein 1 A-domain | 7O9Q | c1 | -9.4 |

| c5 | -9.1 | |||||

| 11 | NG CBS 138 | cell adhesion | epithelial adhesin 1 | 4D3W | c1 | -7.1 |

| c5 | -7.4 | |||||

| 12 | NG CBS138 | protein transport | importin subunit alpha | 7VPS | c1 | -9.8 |

| c5 | -9.3 | |||||

| 13 | SC | protein transport | importin alpha subunit | 2C1T | c1 | -9.2 |

| c5 | -8.7 | |||||

| 14 | NG CBS138 | transferase | 6,7-dimethyl-8-ribityllumazine synthase |

4KQ6 | c1 | -9.4 |

| c5 | -9.4 | |||||

| 15 | NG | transferase | flavin mononucleotide adenylyltransferase |

3FWK | c1 | -7.9 |

| c5 | -7.9 | |||||

| 16 | CA SC5314 | metal binding protein | enolase 1 | 7VRD | c1 | -8.1 |

| c5 | -8.1 | |||||

| 17 | NG | apoptosis | metacaspase-1 | 7QP0 | c1 | -7.6 |

| c5 | -7.8 | |||||

| 18 | NG CBS 138 | protein transport | importin alpha arm domain | 7VPT | c1 | -7.1 |

| c5 | -7.0 | |||||

| *SC - Saccharomyces cerevisiae, NG - Nakaseomyces glabratus (Candida glabrata), CA - Candida albicans. **Protein targets are taken from RCSB Protein Data Bank [56]. | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).