1. Introduction

Image registration is a fundamental technique in medical imaging, playing a crucial role in various clinical applications such as image-guided radiation therapy, image-guided surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. The core objective of registration is to identify an optimal transformation that aligns images from different datasets, which is vital in scenarios where valuable information is distributed across multiple images (e.g., images acquired at different time points or from different modalities) [

1,

2]. Accurate image registration is essential for the integration of relevant information, aiding in clinical decision-making and improving patient outcomes [

3,

4].

In a typical registration task, one image is designated as the "fixed" image, while the other, the "moving" image, undergoes transformation based on the reference provided by the fixed image [

4]. Over the years, various techniques have been proposed for image registration, ranging from classical intensity-based methods to more sophisticated approaches incorporating machine learning [

2,

5]. More recently, deep learning-based strategies have gained popularity for their ability to perform fast and accurate registration. These models, such as those proposed by Vos et al. [

6], use convolutional neural networks (CNNs) to learn complex transformation models, often leveraging image similarity measures to align images in an unsupervised manner.

However, despite the advancements made by deep learning approaches [

7,

8,

9], several challenges persist. These include high computational costs, limited interpretability of the deformation fields, and a tendency to produce anatomically implausible transformations in critical structures. Additionally, deep learning-based methods often require large datasets for effective training, making their deployment in scenarios with limited data challenging [

10]. Furthermore, local pixel-based loss functions in these models may fail to capture the global context of the medical images, potentially leading to misalignment or deformation of important anatomical structures.

Beyond image registration using pixel-based methods, deformable registration methods have been widely applied in medical imaging for aligning anatomical structures in a flexible manner [

5,

11]. Deformable registration allows for non-linear transformations that adapt to local tissue variations, making them especially suitable for complex organ modeling and tracking in dynamic scenarios such as brain or lung imaging. Approaches such as B-spline free-form deformations (FFD) [

5,

12,

13] and diffeomorphic methods, including large displacement diffeomorphic metric mapping (LDDMM), are widely used to model such deformations while preserving the topology of anatomical structures [

14,

15].

However, as with most deformable registration methods, there are challenges, such as the risk of misaligning structures or overfitting noise if regularization terms are poorly chosen [

16]. To address these issues and improve performance, recent strategies have focused on more robust optimization methods, such as Conformal Bayesian Optimization (CBO).

Conformal Bayesian Optimization builds upon standard Bayesian Optimization (BO) but introduces conformal prediction techniques, which provide calibrated uncertainty estimates in the optimization process [

17,

18]. CBO offers several advantages over traditional BO, including more reliable and interpretable uncertainty quantification, making it well-suited for tasks in medical image registration, where the alignment of critical anatomical structures must be highly accurate and reliable. By leveraging conformal prediction, CBO provides statistically valid coverage guarantees, ensuring that the proposed transformations during the registration process remain within plausible bounds of uncertainty. This helps in controlling the trade-off between exploration (searching new areas of the parameter space) and exploitation (refining known good solutions) [

17].

Additionally, CBO’s ability to incorporate prior knowledge into the optimization framework allows for better alignment in complex cases, where traditional optimization methods might fall into poor local minima or produce unrealistic deformations. The conformal aspect helps adjust the confidence intervals around model predictions, enabling the registration model to more effectively balance between speed and precision, especially in high-dimensional and noisy datasets.

In this paper, we propose a novel deformable point cloud registration approach that utilizes Conformal Bayesian Optimization (CBO) to align 3D point clouds representing brain structures. Our method frames the point cloud registration task as an optimization problem, where the transformation parameters are modeled using a probabilistic framework with conformal predictions. The key contribution of this work is the development of a robust and interpretable model for point cloud alignment, leveraging the advantages of CBO to achieve more accurate and plausible deformations, especially in anatomically sensitive regions. This approach enhances both the interpretability of the registration process and the overall accuracy of point cloud alignment.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets

This study uses two datasets to evaluate our proposed method for anatomically plausible nonrigid shape matching via Bayesian optimization.

The first dataset is the TOSCA dataset [

19,

20], which contains high-resolution three-dimensional nonrigid shapes. The dataset consists of 80 objects with varying poses and shapes, including 11 cats, nine dogs, three wolves, eight horses, six centaurs, four gorillas, 12 female figures, and two male figures, each with 7 and 20 poses.

The second dataset, referred to as the Brain Asphyxia Dataset, comprises Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) scans from patients with perinatal asphyxia acquired during early childhood at a medical center in Colombia. We process the MRI images using the infant FreeSurfer framework [

21] to obtain 3D point cloud representations of the neuroanatomical structures. Specifically, we segment 20 different neuroanatomical regions relevant to perinatal asphyxia [

22,

23]. Each subject’s anatomy is thus represented by a collection of

m (

) point clouds

, where each point cloud represents a specific brain structure. Each point cloud

consists of

points, with each point

defined by its coordinates

[

24].

We test our approach on 20 different point clouds for the TOSCA dataset. We apply random rigid transformations to evaluate the model’s ability to recover rigid transformations on point clouds with significant variability. For the Brain Asphyxia Dataset, we test our model with MRI scans acquired at different times for the same patient (e.g., at birth and one year later) to evaluate clinical outcomes. Each patient has 20 different neuroanatomical structures at different ages, including the left and right white matter, caudate nucleus, putamen, and thalamus.

2.2. Deformable Registration of Point Clouds

Let us consider two point clouds: the fixed point cloud and the moving point cloud , where . The goal is to find a transformation that aligns to by minimizing the alignment error.

In the case of nonrigid registration, a global transformation is insufficient to recover the point correspondences accurately due to the deformable nature of the shapes. Therefore, we approximate the transformation function locally by grouping points into

c clusters, where neighboring points are likely to undergo similar transformations. The deformation of the moving point cloud is modeled as:

where

represents the affine transformation matrix for cluster

j, and

are weights indicating the influence of cluster

j on point

. The homogeneous coordinate (factor 1) is used to facilitate affine transformations.

The choice of the number of clusters c is crucial; if , where n is the number of points, the problem becomes mathematically and computationally intractable. Conversely, a very low c may not capture the complexity of the deformation. We typically select c such that is sufficient to model the deformation accurately.

To determine the clusters, we use an initial set of correspondences, possibly obtained through a matching strategy or feature descriptors, to group each point with key points . We define the surface representation of as and of as . We then partition the surfaces into patches and based on geodesic distances from the key points.

Each patch and is further divided into r neighboring rings and , respectively, based on geodesic distances. The entire surface can thus be represented as , and each patch as . The same applies to .

We estimate the deformation hierarchically at different geometric levels: local, intermediate, and global. At the local level, we estimate the transformation for each neighboring ring . At the intermediate level, we estimate the transformation for each patch based on the deformed neighboring rings. Finally, at the global level, we estimate the overall transformation based on the deformed patches.

The estimation of the transformation parameters is performed iteratively, updating one level at a time while keeping others fixed, as summarized in Algorithm 1.

|

Algorithm 1: Estimation of Transformation Parameters |

- Require:

Initial correspondences between and - Require:

Geodesic surface partitions - 1:

while Convergence criterion not met do

- 2:

for each patch i do - 3:

for each neighboring ring j do - 4:

Compute local transformation by minimizing local energy - 5:

Update positions of vertices in - 6:

end for - 7:

Compute intermediate transformation by minimizing intermediate energy - 8:

Update positions of vertices in - 9:

end for - 10:

Compute global transformation by minimizing global energy - 11:

Update positions of all vertices in - 12:

end while |

2.2.1. Energy Model

The total energy function

guiding the deformation is composed of three terms:

where

,

and

are the local, intermediate, and global energy terms, respectively. The core idea is to combine local and global geometric information along with an intermediate representation to ensure accurate and smooth deformations.

Local Energy

The local energy operates at the finest level, focusing on small neighboring regions (rings) around each key point. For the i-th patch, we define the j-th neighboring ring as the set of vertices at geodesic distance j from the key point . The goal is to find the local transformation for each ring that aligns with the corresponding ring in the moving point cloud.

We formulate this as a weighted least squares problem:

where

is an influencing factor based on surface area or other criteria, and

is the corresponding point in

. The local transformations are assumed to be locally rigid and independent.

Intermediate Energy

We aim to integrate the deformed neighboring rings at the intermediate level to obtain a coherent transformation for each patch . We consider the deformed vertices from the local transformations and model the problem as fitting a Gaussian Mixture Model (GMM), where the deformed vertices are the centroids. The corresponding vertices in are observations.

We minimize the negative log-likelihood:

where

represents the GMM parameters for patch

i.

Global Energy

Global energy corrects any residual misalignments on a global scale. It refines the overall pose of the moving point cloud by finding a global rigid transformation

that minimizes:

where

are the deformed points after the intermediate step, and

is a weighting factor that may depend on the distance between corresponding points.

2.3. Anatomical Plausibility

While the deformation field provides a mechanism for aligning point clouds, ensuring that the resulting transformations adhere to anatomical constraints is vital for clinical validity. Deformable techniques can yield highly flexible mappings, but without constraints, they risk generating unrealistic or biologically implausible results.

To address this, we incorporate a regularization term

into the cost function to enforce anatomical plausibility:

where

is a similarity metric between the deformed moving point cloud and the fixed point cloud,

is a regularization parameter, and

quantifies the smoothness and plausibility of the deformation field.

2.3.1. Regularization Terms

We consider several regularization terms commonly used in deformable registration:

L2 Norm Regularization

Penalizes large gradients in the deformation field:

where

is the gradient of the deformation field.

Total Variation (TV) Regularization

Encourages piecewise smoothness while preserving edges:

where

.

Bending Energy Regularization

Penalizes curvature in the deformation field to maintain smoothness:

where

is the Laplacian operator.

Smoothness Constraints

Enforce smoothness by penalizing differences between neighboring deformation vectors:

2.3.2. Similarity Metric

We use the Hausdorff distance as the similarity metric, defined as:

This metric is sensitive to outliers and captures the maximum deviation between the point clouds, minimizing the largest errors.

2.4. Conformal Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Process Priors

To optimize the hyperparameters controlling the deformation model, we employ Bayesian Optimization with Gaussian Process (GP) priors. The objective is to minimize the cost function over the bounded domain .

We model as a sample from a GP prior, specified by a mean function (often zero) and a covariance function . The GP provides a probabilistic model of the function, allowing us to predict at unobserved points.

The acquisition function

guides the selection of the next hyperparameters to evaluate by balancing exploration and exploitation. We use Conformal Bayesian Optimization [

17], which provides robustness against model misspecification and covariate shift, offering coverage guarantees.

Table 1 presents the hyperparameters optimized within the proposed Bayesian framework for deformable point cloud registration. Each hyperparameter plays a crucial role in balancing the accuracy and computational feasibility of the registration process.

Number of clusters (c): This parameter determines the granularity of local deformations. A higher number of clusters allows for finer transformations; however, excessively high values may lead to overfitting or increase computational complexity. The range ensures adaptability without compromising efficiency.

Regularization weight (): It controls the trade-off between alignment precision and deformation smoothness. Higher values promote smoother transformations, which are crucial for maintaining anatomical plausibility, particularly in sensitive brain structures.

Number of neighboring rings (r): This parameter defines the local neighborhood around each point and influences how adjacent points contribute to the transformation. Smaller values encourage localized deformations, while higher values capture broader contextual relationships.

Influence factor (): It modulates the importance of local energy contributions from each neighboring ring. This ensures that the algorithm appropriately balances the impact of different regions on the final deformation, which is essential for aligning structures with varying geometric properties.

Threshold for global energy correction (d): This parameter determines when global transformations, such as translation and rotation, are applied. A lower threshold triggers more frequent global adjustments, ensuring accurate alignment across large-scale transformations.

By integrating anatomical plausibility through regularization and optimizing hyperparameters via Conformal Bayesian Optimization, our method aims to achieve accurate deformable registrations of point clouds.

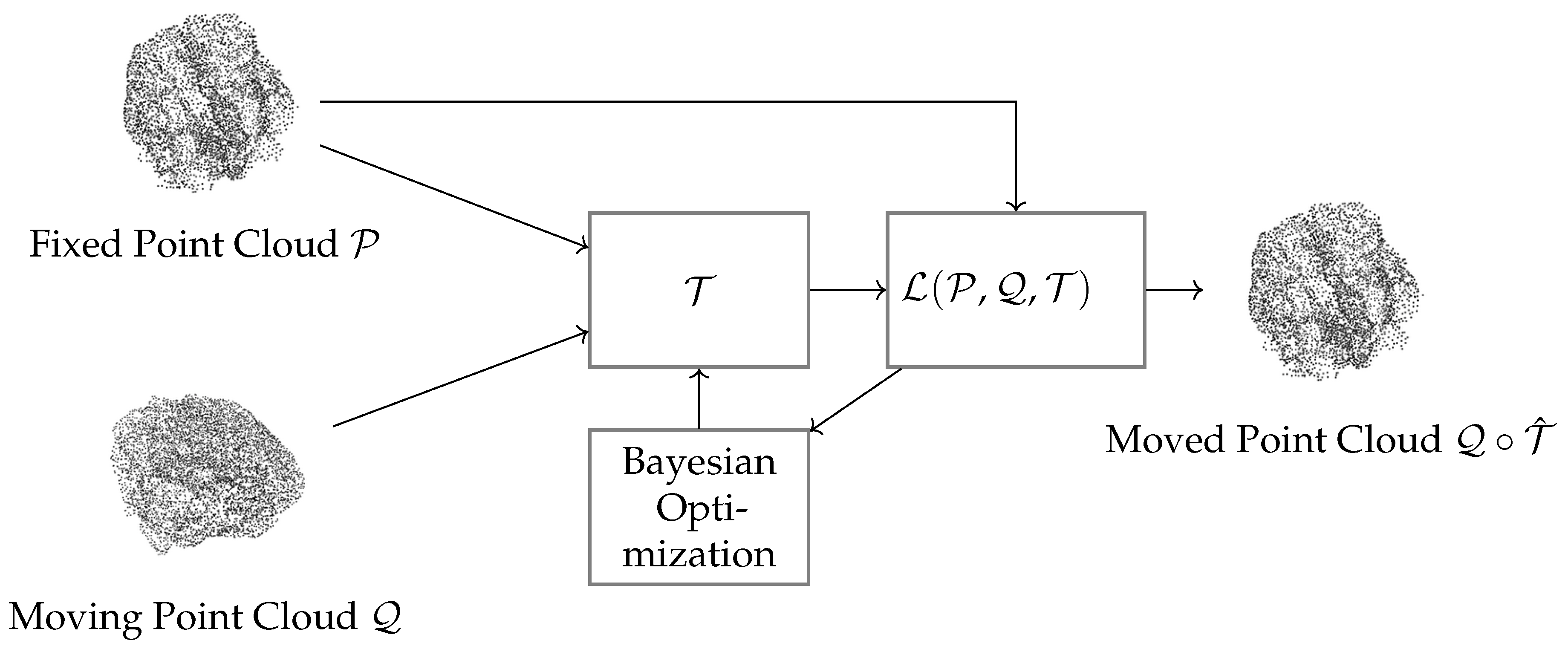

Figure 1 shows the proposed framework for deformable registration of point clouds, using Bayesian optimization to enhance alignment. The process starts with two input point clouds: a fixed cloud

and a moving cloud

. The transformation function

estimates the non-rigid transformations needed to align

with

. Besides, the alignment is driven by a cost function

, combining geometric distance with a regularization term to ensure smooth and anatomically plausible deformations. Bayesian optimization iteratively adjusts the transformation parameters to refine the alignment and optimize the number of initial correspondences. Finally, the output is the deformed point cloud

, representing the transformed version of the moving cloud. This approach balances local flexibility and global alignment, ensuring adherence to anatomical constraints. Its modular design and probabilistic strategy make it ideal for medical imaging, where precise and interpretable alignments are essential for clinical decision-making.

3. Results

3.1. Tosca Database

To validate the deformable registration model, the performance of the model is mainly analyzed in synthetic databases, such as the Tosca database. In this context, a series of experiments are initiated that allow us to identify how the cost function weights the deformations applied to the point clouds.

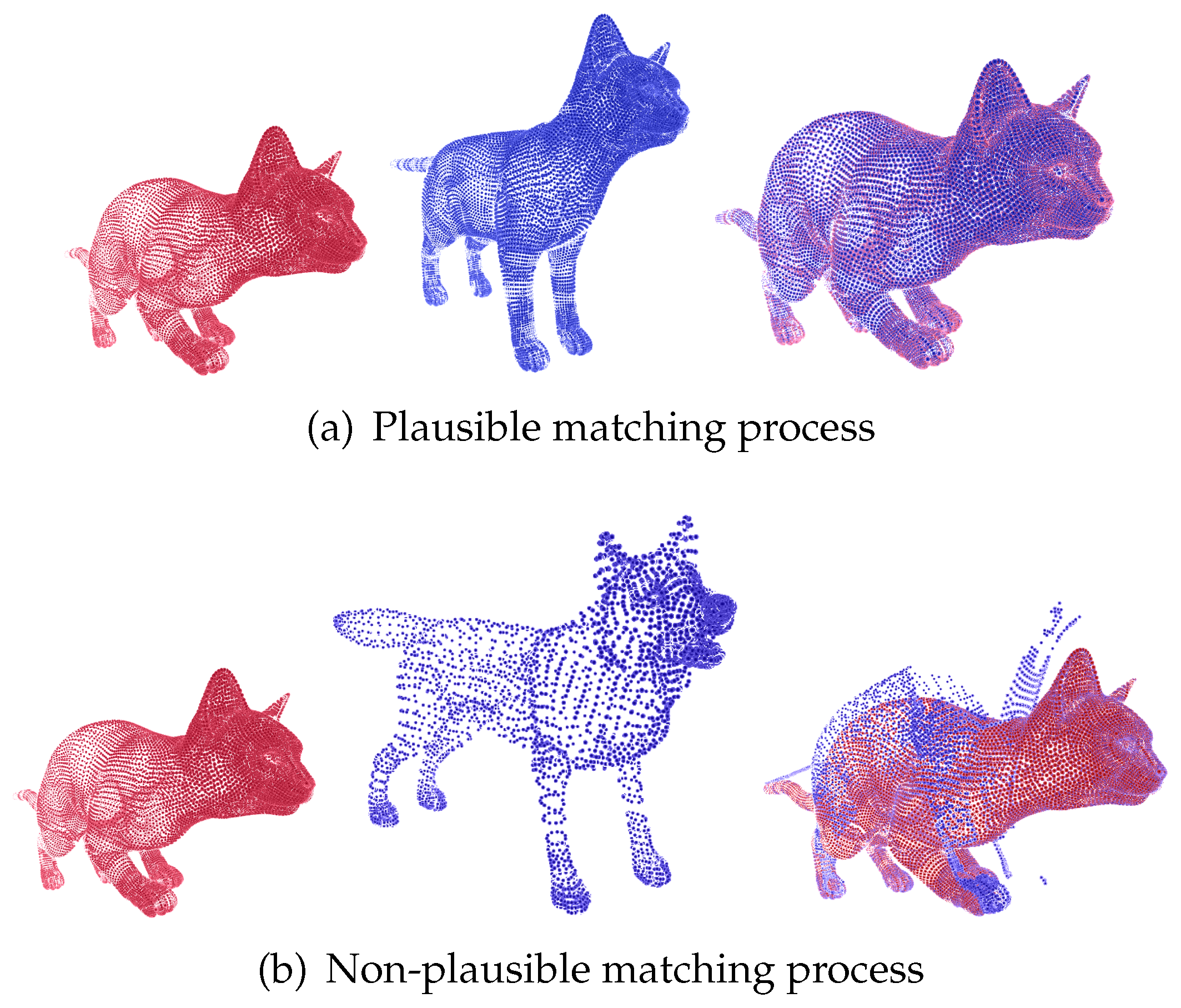

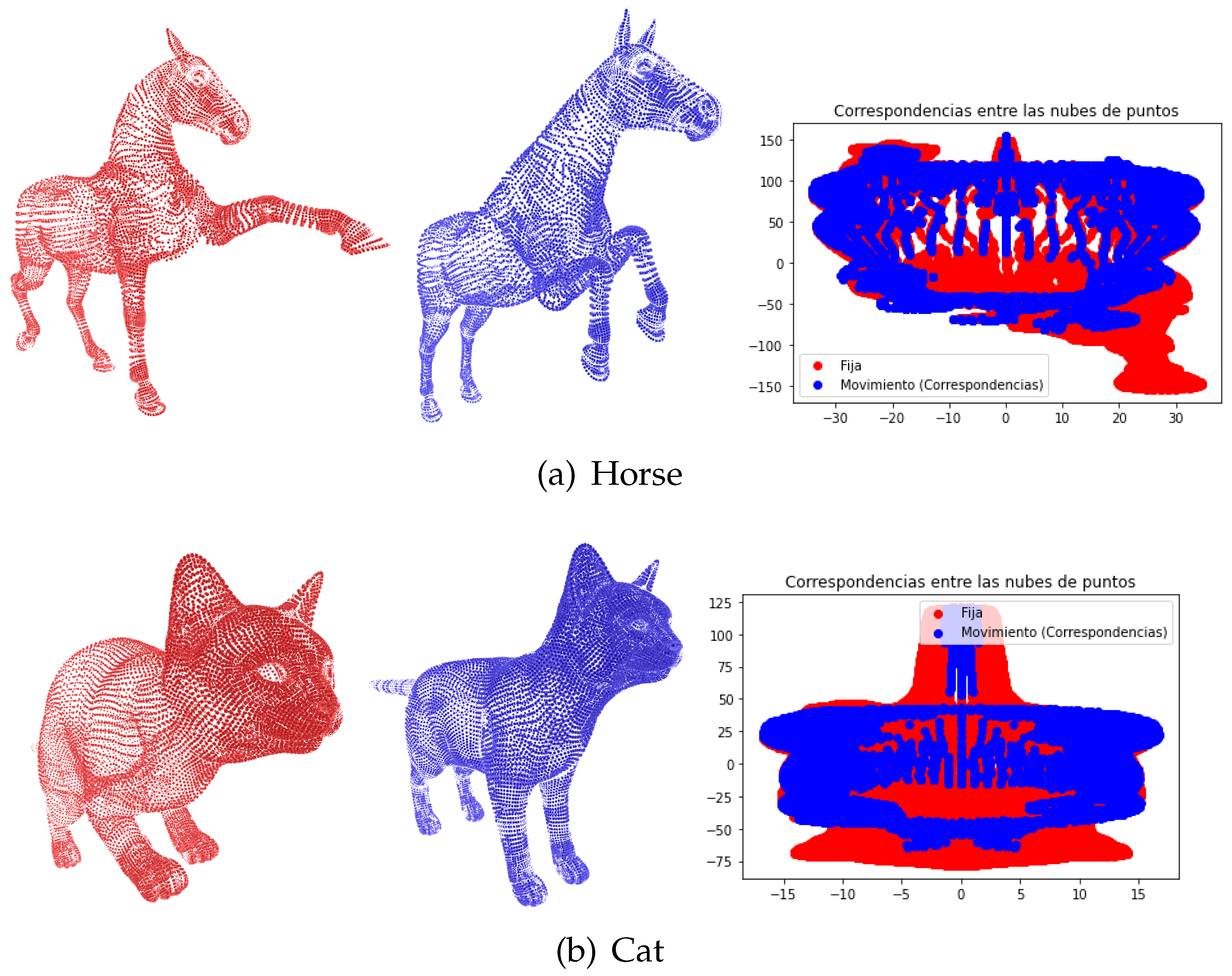

Figure 2 shows an example of the initial correspondence process applied to the point clouds to calculate the deformation

.

In our first experiment, we applied the proposed deformable registration method to the Tosca dataset, which consists of non-rigid 3D models of various subjects, such as horses and cats.

Figure 2 illustrates the registration process between a fixed point cloud (red) and a moving point cloud (blue). The right side of each subfigure presents the point correspondences established during the initial registration phase.

Figure 2a shows the deformable registration of the horse models, where both the fixed and moving point clouds exhibit significant variations in pose. The corresponding points identified between the clouds (shown on the right) highlight the complexity of aligning the limbs and head, which exhibit distinct positional changes. However, the method’s robustness is evident as it can initialize correspondences even when significant structural differences exist between poses.

Figure 2 presents a similar process for the cat models, which also undergo non-rigid deformations. The initial correspondences are visualized, indicating a robust alignment of the major body components, such as the torso and limbs. The method’s versatility is demonstrated as it effectively handles variations in pose, with the established correspondences maintaining consistency despite local deformations. The results show that even in highly non-rigid cases, such as those seen in the Tosca dataset, our method successfully aligns the point clouds in an anatomically plausible manner, outperforming conventional rigid alignment techniques.

To validate the plausibility approach in the rough database, the behavior of the deformable model is analyzed for point clouds that present changes in pose,

Figure 2a or point clouds of different quadrupeds, as is the case of the

Figure 2b. At the same time, the cost function is analyzed in

Figure 4. For both experiments, we can observe that the point clouds belonging to the same subjects have, in general terms, a lower cost.

The results shown in

Figure 3c and d illustrate the effectiveness and limitations of our deformable registration approach using Bayesian optimization.

Figure 3c shows that the method successfully aligns point clouds with significant pose variations, demonstrating its robustness in handling non-rigid deformations. This capability is particularly useful in medical imaging scenarios where anatomical structures exhibit significant but plausible variations over time or due to patient movement. However, as shown in

Figure 3d, the method encounters challenges when applied to point clouds with fundamentally different anatomies, resulting in anatomically implausible registrations. This highlights the critical importance of incorporating anatomical constraints into the registration process. The method’s ability to preserve structural consistency in plausible cases underscores its potential for applications in clinical settings, particularly when tracking changes in brain structures over time or within a population.

Figure 3.

Example of deformable registration process in the Tosca database. The figure shows a representation of the registration process in point clouds for figures that present the same anatomy with a varied pose and for figures with different anatomy.

Figure 3.

Example of deformable registration process in the Tosca database. The figure shows a representation of the registration process in point clouds for figures that present the same anatomy with a varied pose and for figures with different anatomy.

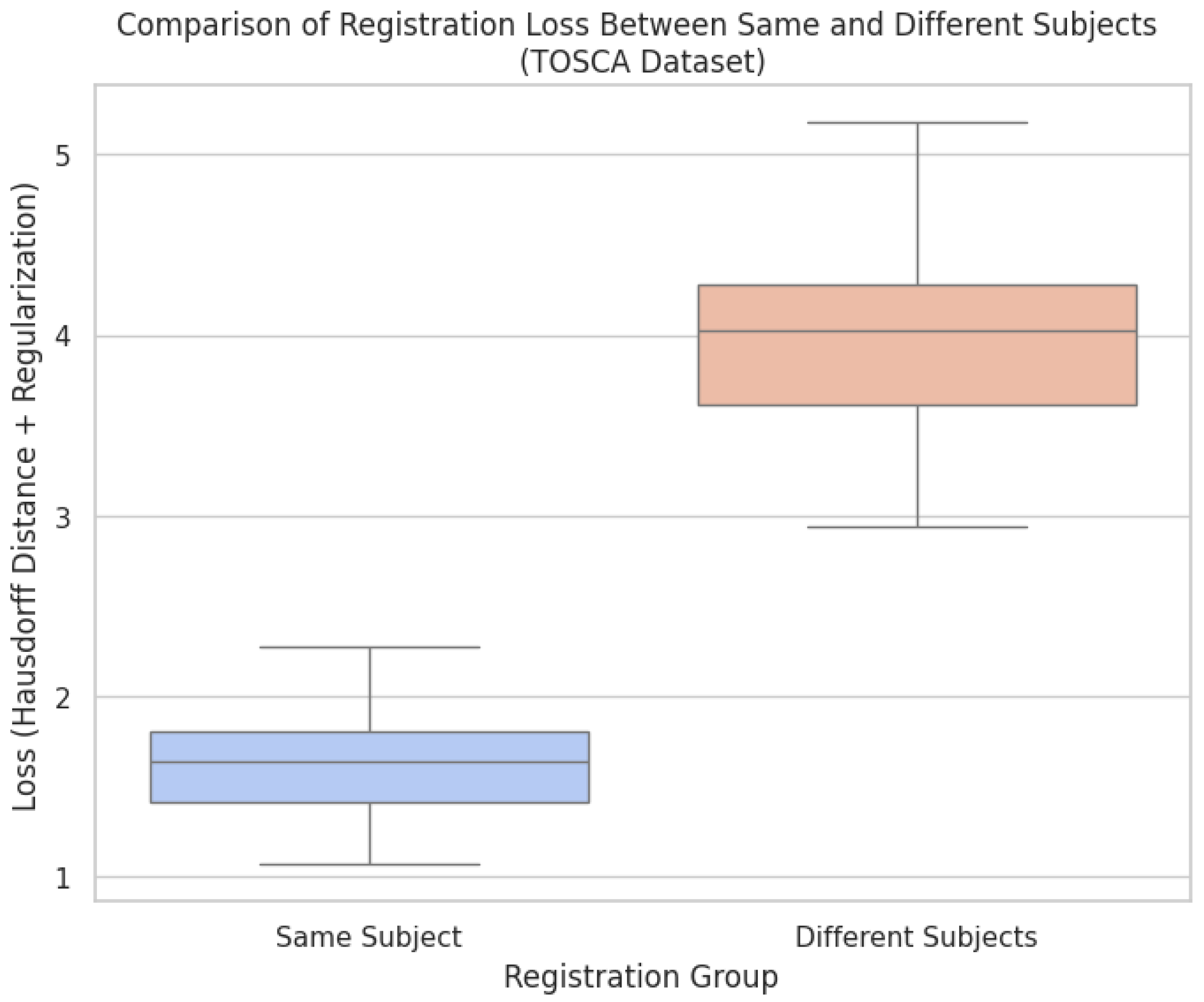

Figure 4.

Comparison of the registration process costs: aligning point clouds of the same subject in different poses versus aligning point clouds from different subjects.

Figure 4.

Comparison of the registration process costs: aligning point clouds of the same subject in different poses versus aligning point clouds from different subjects.

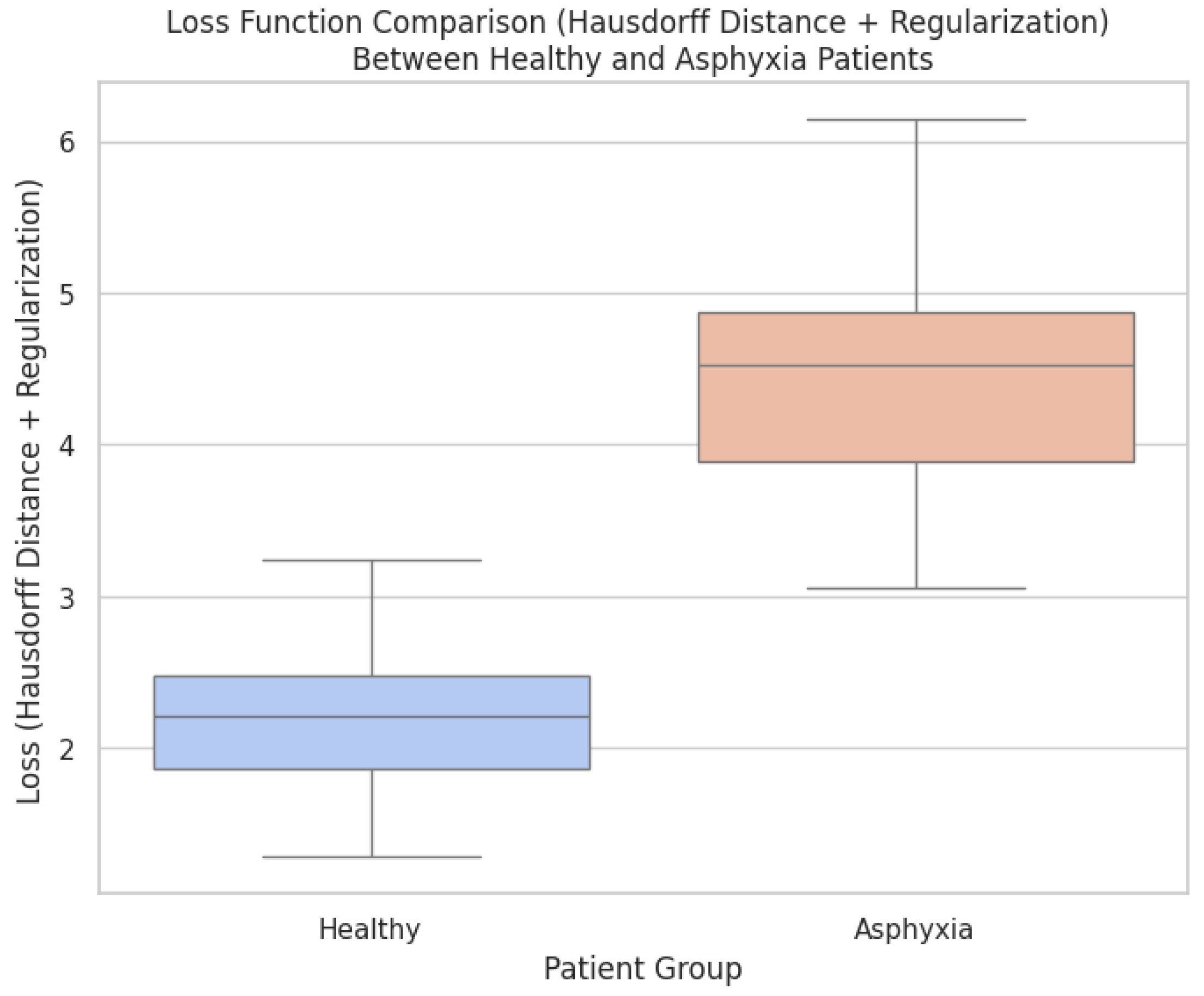

The results from

Figure 4 provide a quantitative analysis of the registration loss, comparing alignments between point clouds of the same subject in different poses versus point clouds from different subjects. The lower loss values observed in the same group indicate that the deformable registration framework, enhanced by Bayesian optimization, performs well in cases where anatomical consistency is preserved, as demonstrated in

Figure 2. The use of Hausdorff distance combined with regularization effectively captures the quality of the alignment, showing minimal deformation and high anatomical plausibility when the same subject is being registered across varying poses. In contrast, the higher loss values in the different shapes group, as seen in Figure, reflect the model’s limitations when aligning point clouds with fundamentally different anatomies. These higher loss values indicate that the method struggles to maintain anatomical fidelity when confronted with subjects that deviate significantly in shape and structure, leading to implausible deformations. The results further emphasize the importance of incorporating anatomical constraints and highlight that while the method excels in non-rigid but plausible scenarios, it requires further refinement to handle more complex cases involving diverse anatomies. Overall, the comparison shows the benefits of the framework’s applicability in medical imaging, where preserving anatomical accuracy is critical. It also points to enhanced regularization methods to address cross-subject variability.

3.2. Database Brain Asphyxia

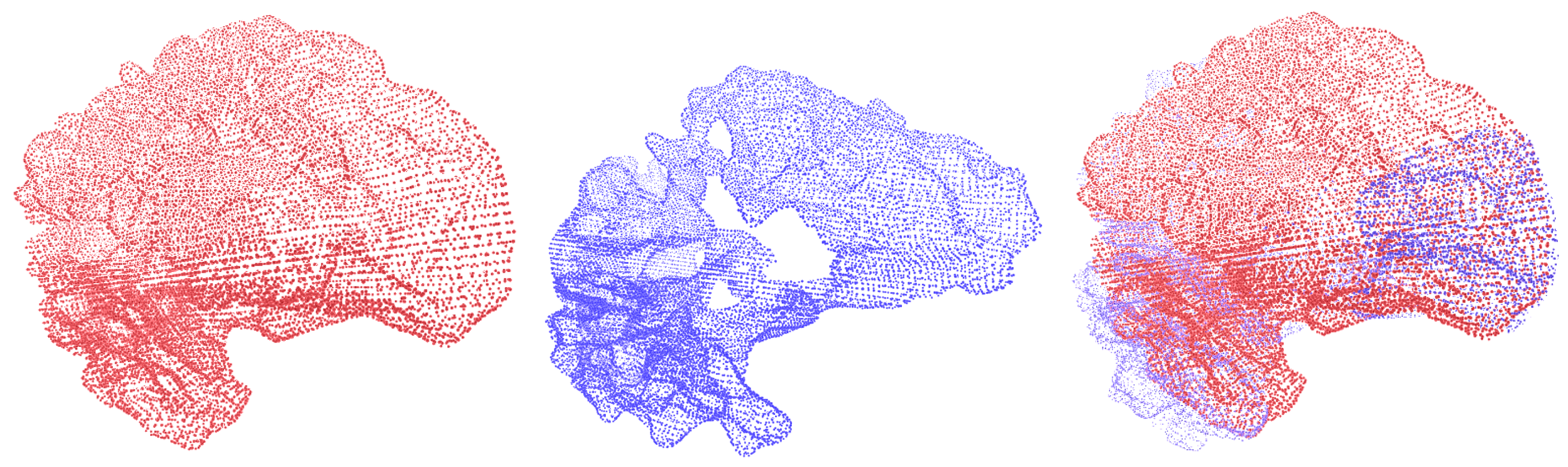

In the case of

Brain Asphyxia, two sets of experiments were conducted: one focused on registering point clouds of brain structures from healthy patients and another on registering point clouds from patients diagnosed with perinatal asphyxia. In the case of healthy patients, the brain structures, while exhibiting non-rigid changes, tend to maintain volumetric consistency across time points. This consistency means that although slight variations in contours may exist, critical features such as size and shape are preserved, as illustrated in

Figure 6. These deformations are typically mild, which makes the registration task less challenging. One potential reason for this uniformity is that the point clouds were extracted using probabilistic atlases, which ensure a high level of alignment. On the other hand, brain structures from patients with perinatal asphyxia exhibit a significant degree of variability in both shape and size. This is due to the severe anatomical changes caused by the condition. The increased variability leads to a more complex and challenging registration task, where the model struggles to converge, resulting in a higher cost function, as shown in

Figure 7. The comparative analysis of different regularization terms—such as L2 Norm, Total Variation, Bending Energy, and Smoothness Constraints—reveals their distinct impact on deformable registration performance. For healthy patients, where deformations are relatively small, the L2 Norm effectively maintains the overall smoothness and alignment accuracy of the registration. It imposes a penalty on large deformations, ensuring that the anatomical consistency of brain structures is preserved.

For patients with perinatal asphyxia, where significant deformations are present, the use of more advanced regularization terms like Total Variation and Bending Energy becomes crucial. The Bending Energy regularization helps to maintain the smoothness of large deformations, ensuring anatomically plausible transformations by minimizing sharp or unnatural changes. Total Variation, on the other hand, balances smoothness with the ability to preserve sharp edges or discontinuities in the deformation, which can be critical in pathological cases where certain brain regions undergo more pronounced changes.

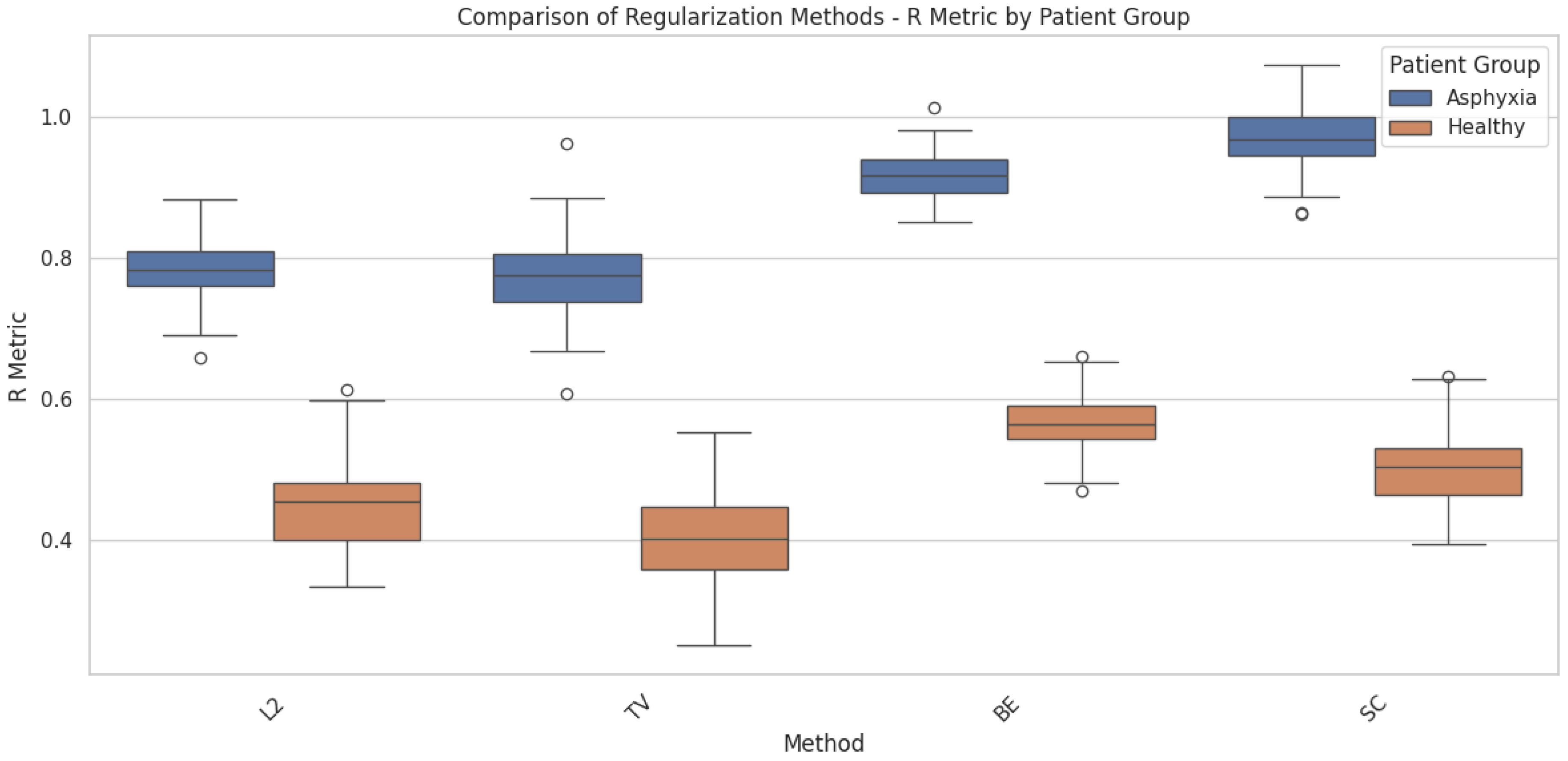

Figure 5 provides a comparative analysis of the loss function

across four different regularization methods—L2 norm, Total Variation (TV), Bending Energy (BE), and Smoothness Constraints (SC). The comparison is presented for two patient groups: healthy individuals and patients diagnosed with perinatal asphyxia. This analysis highlights how each regularization method influences the deformation field in brain structure registration, emphasizing the variability between patient groups. The Smoothness Constraints regularization assists in controlling local deformations, ensuring that small neighborhoods within the brain structure undergo consistent transformations without introducing unrealistic distortions. However, its effectiveness diminishes when the variability in the shape and size of the structures is extreme, as seen in perinatal asphyxia cases. This variability explains the more significant performance variance observed for asphyxia patients when using SC, as illustrated in the figure. The findings further underscore the adaptability of different regularization terms to varying levels of deformation complexity. Standard regularization methods, such as the L2 Norm and Smoothness Constraints, perform well for healthy patients, ensuring smooth transformations and accurate alignment. However, for patients with perinatal asphyxia, more advanced methods like Total Variation and Bending Energy become essential due to their ability to handle complex anatomical alterations. This adaptability highlights the need for case-specific approaches in medical imaging to ensure accurate and anatomically plausible brain structure registration across diverse clinical scenarios.

Figure 5.

Comparison of the loss function across different regularization terms—L2 norm, Total Variation, Bending Energy, and Smoothness Constraints—applied to the deformation field in brain structure registration. The analysis includes both healthy patients and patients diagnosed with Perinatal Asphyxia. The figure highlights how each regularization term influences the deformation model

Figure 5.

Comparison of the loss function across different regularization terms—L2 norm, Total Variation, Bending Energy, and Smoothness Constraints—applied to the deformation field in brain structure registration. The analysis includes both healthy patients and patients diagnosed with Perinatal Asphyxia. The figure highlights how each regularization term influences the deformation model

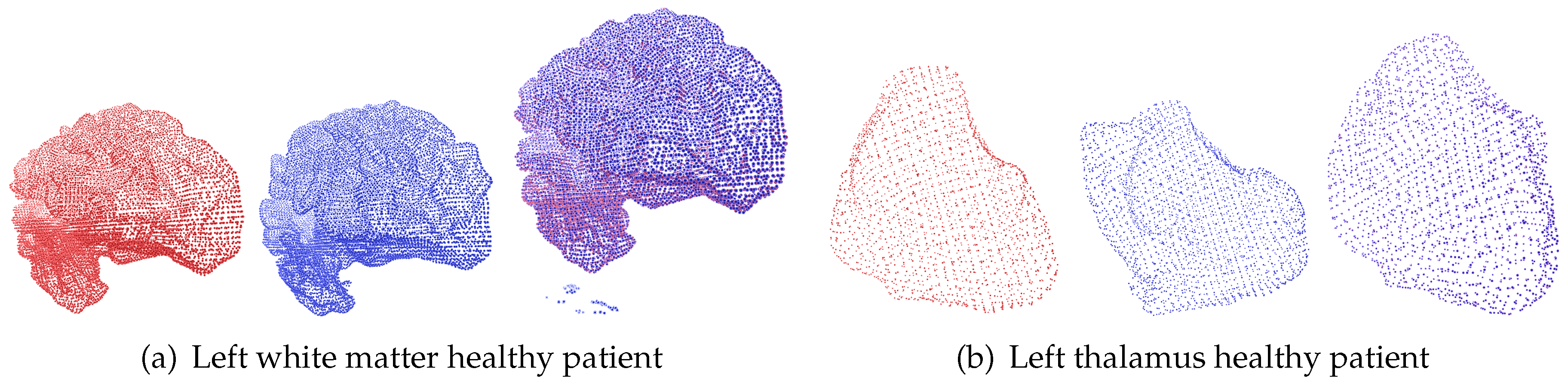

Figure 6.

Example of deformable registration of point clouds belonging to brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database. This case shows the registration process in patients with healthy brain structures.

Figure 6.

Example of deformable registration of point clouds belonging to brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database. This case shows the registration process in patients with healthy brain structures.

Figure 7.

Example of deformable registration of point clouds belonging to brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database. This case shows the registration process between healthy patients’ brain structures (red) and those affected by perinatal asphyxia (blue).

Figure 7.

Example of deformable registration of point clouds belonging to brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database. This case shows the registration process between healthy patients’ brain structures (red) and those affected by perinatal asphyxia (blue).

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 show the deformable registration of point clouds representing brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database.

Figure 6 shows the registration process in healthy patients, focusing on two brain structures: the left white matter and the left thalamus. These examples highlight the algorithm’s ability to align brain structures with minimal deformation, ensuring smooth transformations and accurate alignment. In contrast,

Figure 7 presents the registration between brain structures of healthy patients (red) and those affected by perinatal asphyxia (blue). The comparison reveals a higher degree of structural variability in the asphyxia group, requiring more complex deformation fields to achieve alignment. Despite this complexity, the framework successfully aligns the brain structures, showcasing the robustness of the approach. The benefit of incorporating probabilistic optimization through Conformal Bayesian Optimization (CBO) is evident in these results. CBO enables the framework to iteratively learn plausible shape deformations, balancing local flexibility with global alignment. The probabilistic nature of CBO ensures that transformations adhere to anatomical constraints, reducing the risk of producing unrealistic deformations. This is particularly valuable in cases with significant anatomical variability, such as perinatal asphyxia, where traditional optimization techniques might struggle to maintain anatomical plausibility. The framework’s modular design allows it to adapt to the specific anatomical characteristics of each patient group. In healthy patients, simpler deformations suffice, while in the asphyxia group, the optimization dynamically adjusts the deformation parameters to account for more substantial changes in brain structures. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach in addressing varying levels of complexity, ensuring both accuracy and clinical relevance in brain structure registration.

Figure 8 compares the registration costs for aligning brain structures from healthy patients and those affected by perinatal asphyxia. The cost metric combines Hausdorff distance and regularization terms, reflecting alignment precision and deformation smoothness. As depicted, the registration cost is consistently higher for the asphyxia group, indicating the increased complexity associated with aligning brain structures exhibiting significant anatomical variability. The elevated costs observed in the asphyxia group reflect the more significant structural deformations required to achieve alignment. Brain structures affected by perinatal asphyxia often exhibit altered shapes and sizes, making the registration task more challenging. In contrast, healthy patients display more consistent anatomical features across different scans, lowering registration costs. This contrast highlights the importance of advanced optimization methods, such as Conformal Bayesian Optimization (CBO), in adapting deformation models to varying anatomical conditions. The results further demonstrate the benefit of incorporating regularization into the loss function. While achieving accurate alignment is crucial, the regularization term ensures that the deformations remain anatomically plausible. The balance between alignment precision and regularization promotes meaningful transformations for both patient groups, minimizing the risk of overfitting or producing unrealistic deformations. These findings emphasize the need for adaptive frameworks in medical imaging to address the complexities inherent in pathological conditions like perinatal asphyxia.

4. Conclusions

This study presents a novel framework for deformable registration of 3D point clouds representing brain structures, leveraging Conformal Bayesian Optimization (CBO) to enhance alignment precision and maintain anatomical plausibility. The proposed method integrates probabilistic modeling to optimize non-rigid transformations, addressing critical challenges in aligning brain structures with significant anatomical variability. Through the combination of Hausdorff distance and regularization terms, the framework ensures smooth deformations that respect anatomical constraints, reducing the risk of implausible transformations. The experiments conducted on both the Tosca and Brain Asphyxia databases demonstrate the robustness and versatility of the approach. Results from the Tosca database highlight the model’s ability to handle substantial non-rigid deformations, achieving accurate alignments even with significant pose variations. Furthermore, analyzing brain structures from the Brain Asphyxia database underscores the importance of adaptive optimization strategies. The use of CBO enabled the framework to accommodate the anatomical complexities presented by pathological conditions such as perinatal asphyxia, ensuring that transformations remained clinically relevant. Comparative evaluations of different regularization methods revealed the necessity of case-specific configurations to optimize performance. While standard regularization techniques proved sufficient for aligning healthy brain structures, more advanced methods, such as Bending Energy and Total Variation, were critical for managing the more complex deformations observed in asphyxia cases. The modular nature of the proposed framework allows it to adjust to varying anatomical conditions dynamically, enhancing its applicability across diverse clinical scenarios. Besides, integrating CBO into the deformable registration process offers several advantages, including improved alignment accuracy, reduced computational complexity, and better control over deformation smoothness. This framework addresses key limitations of existing methods by providing an interpretable and adaptable approach that balances alignment precision with anatomical plausibility. The findings of this study demonstrate the potential of CBO-enhanced registration models to support clinical decision-making, particularly in scenarios that require tracking anatomical changes over time or across patient populations. Future work will explore the extension of this approach to other imaging modalities and further refine the optimization framework to better address cross-subject anatomical variability.

For future works, we plan to integrate elastic transformations controlled by Bayesian latent variable frameworks to enhance the reliability and robustness of the registration process. Bayesian latent variables will enable probabilistic representations of deformation fields, better capturing global and local anatomical variability. Elastic transformations will offer greater adaptability to handle complex deformations, especially in pathological cases, while maintaining anatomical plausibility. We also aim to optimize the computational cost of these models, ensuring efficient training and uncertainty management. This approach will support more reliable alignment across diverse imaging modalities, promoting better clinical outcomes.

Author Contributions

MSc. MCA and Dr. HFG conceptualized the methodology, developed the machine learning methods, and prepared the original draft of the manuscript. Dr. MCA was responsible for data curation, investigation, validation, and contributed to the methodology. Drs. GLPH and DACP curated the data and contributed to the original draft preparation. Drs. DACP, MCA and HFG contributed to the conceptualization, development of artificial intelligence methods, and took part in writing, reviewing, and editing the original draft. Drs. GLPH, and AAOG were involved in the conceptualization, reviewing, and editing the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This research was developed under the project: “SISTEMA DE MONITOREO AUTOMÁTICO PARA LA EVALUACIÓN CLÍNICA DE INFANTES CON ALTERACIONES NEUROLÓGICAS MOTORAS MEDIANTE EL ANÁLISIS DE VOLUMETRÍA CEREBRAL Y PATRÓN DE LA MARCHA” financed by MINCIENCIAS, COLOMBIA with code COL111089784907.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures performed in the study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Colombian institutional and/or national research committee and with the 8430-1993 Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The Ethics committee Review Board approved the study at COMFAMILIAR RISARALDA CLINIC (Approval No. 00049-2019-05-09). The patients legal guardian provided informed consent for publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent or guardian for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the MINISTRY OF SCIENCES COLOMBIA - MINCIENCIAS and the institutions involved in the present project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIE |

Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy |

| MRI |

Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| CBO |

Conformal Bayesian Optimization |

| FFD |

Free-form deformation |

References

- Jiang, S.e.a. Robust Medical Image Registration Using Machine Learning. Medical Image Analysis 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zitová, B.; Flusser, J. Image Registration Methods: A Survey. Image and Vision Computing 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maintz, J.; Viergever, M. A Survey of Medical Image Registration. Medical Image Analysis 1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, F.P.M.; Tavares, J. Medical image registration: a review. Computer Methods in Biomechanics and Biomedical Engineering 2014, 17, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rueckert, D.e.a. Nonrigid Registration Using Free-Form Deformations: Application to Breast MR Images. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vos, B.e.a. A Deep Learning Framework for Unsupervised Affine and Deformable Image Registration. Medical Image Analysis 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, G.; Zhao, A.; Sabuncu, M.; Guttag, J.; Dalca, A.V. VoxelMorph: A Learning Framework for Deformable Medical Image Registration. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 38, 1788–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krebs, J.; Delingette, H.; Mailhé, B.; Ayache, N.; Mansi, T. Learning a Probabilistic Model for Diffeomorphic Registration. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2019, 38, 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Dong, Y.; Chang, E.; Xu, Y. Recursive Cascaded Networks for Unsupervised Medical Image Registration. 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 2019, 10599–10609. [Google Scholar]

- Mansilla, L.; Milone, D.H.; Ferrante, E. Learning Deformable Registration of Medical Images with Anatomical Constraints. Neural networks: the official journal of the International Neural Network Society 2020, 124, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashburner, J. A Fast Diffeomorphic Image Registration Algorithm. NeuroImage 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, F.; Kong, Y.; Hu, M.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, C.; Kuang, L.; Han, X. A multi-scale covariance matrix descriptor and an accurate transformation estimation for robust point cloud registration 2024.

- Rodgers, G.; Sigron, G.R.; Tanner, C.; Hieber, S.E.; Beckmann, F.; Schulz, G.; Scherberich, A.; Jaquiéry, C.; Kunz, C.; Müller, B. Combining high-resolution hard X-ray tomography and histology for stem cell-mediated distraction osteogenesis. Applied Sciences 2022, 12, 6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beg, M.e.a. Computing Large Deformation Metric Mappings via Geodesic Flows of Diffeomorphisms. International Journal of Computer Vision 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, Y.H.; Karabacak, O.; Kandemir, M.; Unal, G. ALReg: Registration of 3D Point Clouds Using Active Learning. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotiras, A.e.a. Deformable Medical Image Registration: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, E.; Holmes, C.C. Conformal Bayesian Computation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Ranzato, M., Beygelzimer, A., Dauphin, Y., Liang, P., Vaughan, J.W., Eds.; Curran Associates, Inc., 2021; Volume 34, pp. 18268–18279. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, S.; Maddox, W.J.; Wilson, A.G. Bayesian Optimization with Conformal Coverage Guarantees. arXiv 2210, arXiv:abs/2210.12496. [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein, A.M.; Bronstein, M.M.; Kimmel, R. Efficient Computation of Isometry-Invariant Distances Between Surfaces. SIAM J. Sci. Comput. 2006, 28, 1812–1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronstein, A.M.; Bronstein, M.M.; Kimmel, R. Calculus of Nonrigid Surfaces for Geometry and Texture Manipulation. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2007, 13, 902–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischl, B.R. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 2012, 62, 774–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satheesan, A.P.; Chinnappa, A.R.; Goudar, G.; Raghoji, C.R. Correlation between early magnetic resonance imaging brain abnormalities in term infants with perinatal asphyxia and neuro developmental outcome at one year. International Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S.P.; Ramaswamy, V.; Michelson, D.J.; Barkovich, A.J.; Holshouser, B.A.; Wycliffe, N.; Glidden, D.V.; Deming, D.D.; Partridge, J.C.; Wu, Y.W.; Ashwal, S.; Ferriero, D.M. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. The Journal of pediatrics 2005, 146 4, 453–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Becker, B.; Wachinger, C. Deep Multi-structural Shape Analysis: Application to Neuroanatomy. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018; Frangi, A.F., Schnabel, J.A., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 523–531. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).