Submitted:

23 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation & Empirical Evidence

2.1.1. The Rise of Gig Economy

2.2. The Concept & Reality of the VUCA Times

2.3. Theoretical Grounding An O-B Approach For Gig Economy

- 1.

- Agency Theory

- 2.

- Goal-Setting Theory

- 3.

- Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

- 4.

- Equity Theory

- 5.

- Dynamic Capabilities Theory

- 6.

- Contingency Theory

3. Material and Methods

Conceptual Review Approach:

4. Results

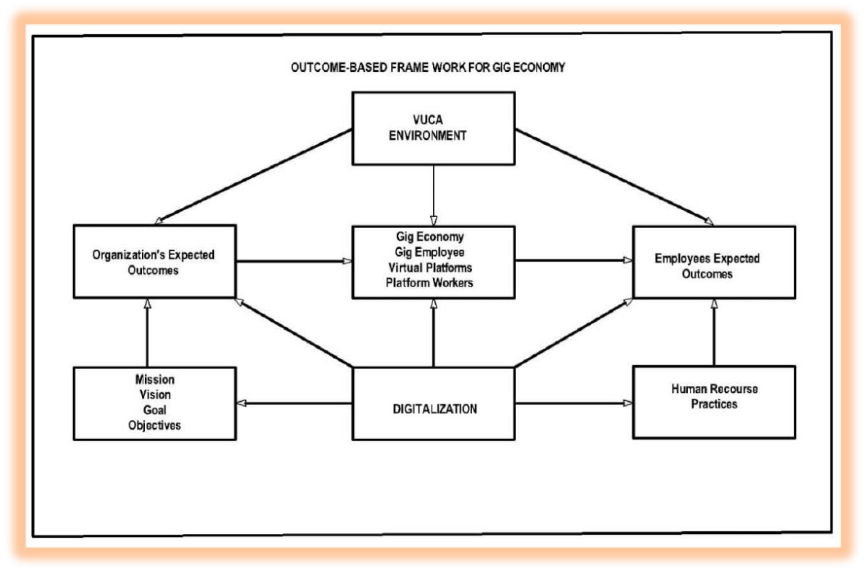

Conceptualization of the Relevance of O-B Model for Gig Economy in VUCA Times

OB-Model - Conceptualization & Characteristics

- Focuses on Results Rather Than Processes - At its core, the O-B approach centers around defining clear, measurable objectives and holding workers accountable for achieving those objectives, without mandating specific processes or methods for how the work should be done. This principle is derived from agency theory (Eisenhardt, 1989), which highlights the need for aligning the interests of workers (agents) with those of employers (principals). In an O-B model, the focus is on the outcomes, which fosters greater autonomy for workers to utilize their skills and resources in the most effective manner possible (Drucker, 1993). This is especially beneficial in the gig economy, where workers often operate in decentralized and autonomous environments.

- Autonomy and Flexibility - The O-B approach allows for high levels of autonomy and flexibility, making it particularly suitable for gig workers who value control over their work schedules and methodologies. By emphasizing results rather than prescriptive procedures, workers can choose the best ways to accomplish their tasks, which aligns with self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985). This theory asserts that autonomy, competence, and relatedness are key drivers of motivation, and an O-B framework allows workers to take ownership of their tasks, fostering intrinsic motivation and engagement (Hackman & Oldham, 1976).

- Clarity and Alignment of Expectations - One of the primary advantages of the O-B approach is the clear alignment of expectations between workers and employers. By setting specific, measurable goals, both parties are able to understand what is required for success. This aligns with goal-setting theory (Locke & Latham, 1990), which emphasizes that specific, challenging goals lead to better performance. In the gig economy, where tasks may vary widely in scope and nature, having clearly defined outcomes ensures that both the gig worker and the platform or client are aligned on deliverables and performance metrics (Friedman, 2014).

- Adaptability in VUCA Environments - The O-B approach is particularly effective in VUCA environments, where traditional process-based management models may be ill-suited due to rapidly changing conditions. The flexibility inherent in an O-B framework allows organizations to remain agile, adapting quickly to changes in demand, market conditions, or technological disruptions (Bennett & Lemoine, 2014). This is especially relevant in the gig economy, where work assignments, clients, and platforms can change frequently, requiring both workers and employers to adapt quickly without sacrificing performance outcomes (Teece, 2014).

- Fairness and Accountability - The O-B model promotes fairness and accountability by tying compensation and rewards directly to performance outcomes. This aligns with equity theory (Adams, 1963), which suggests that individuals assess the fairness of their treatment by comparing their inputs and outcomes with those of others. In the gig economy, where work can be inconsistent and compensation can vary significantly, an outcome-based approach ensures that workers are rewarded based on their actual performance, reducing perceptions of unfairness and promoting greater accountability (Spreitzer et al., 2017).

- Efficiency in Resource Allocation - Another key advantage of the O-B approach is its efficiency in resource allocation. By focusing on outcomes, organizations can better align resources—such as time, tools, and human capital—with the specific goals they seek to achieve. This aligns with dynamic capabilities theory (Teece, 1997), which suggests that organizations must continuously align and reconfigure their resources to address changing environments. In the context of the gig economy, this means that platforms can better allocate tasks to workers with the skills and capacity to meet performance outcomes, ensuring more efficient use of resources and reducing the risk of over- or under-utilization (Doherty, 2010).

3.2. The Gig Economy - Conceptualization, Challenges & Relevance

- Enhanced Efficiency: By focusing on clearly defined outcomes, the O-B framework minimizes the need for micromanagement and oversight, streamlining processes in a gig-based environment (Cramer & Krueger 2016, Peticca-Harris et al 2020)

- Flexibility: The autonomy afforded to gig workers under an O-B model aligns with their preference for flexibility, allowing them to determine how best to meet performance expectations (Veen et al 2020; Gandini, A. 2019)

- Accountability and Fairness: Outcome-based metrics offer a transparent and objective way to measure performance, thereby promoting fairness and accountability in gig work (Healy & Pekarek 2020; Wood et al 2019)

- Stakeholder Alignment: The framework ensures alignment between platform operators, gig workers, and regulatory bodies by setting clear expectations and measurable performance standards (Howard & Borenstein 2018; Todoli-Signes 2017).

3.3. Justification and Proposition

3.4. Outcome-Based Framework for GIG Economy in VUCA Times

4. Discussion

4.2. Implementation & Measurement of Variables

- Define Clear and Measurable Outcomes - The first step in the implementation of the O-B model is to clearly define the outcomes that are expected from gig workers. These outcomes should be aligned with the goals of the organization or platform (Dweck & Yeager, 2019; Sundararajan, 2016). Clear and specific objectives help in maintaining focus on what matters most, avoiding ambiguity. Examples of such measurable outcomes may include project delivery timelines, quality of work, client satisfaction ratings, and other performance metrics that are directly linked to business objectives.

- Develop Outcome-Based Performance Metrics - Once outcomes are defined, the next phase is to develop metrics that evaluate performance based on these outcomes (Katz & Krueger, 2016; Kuhn & Maleki, 2017). These metrics should be transparent, objective, and easily understood by gig workers and platform operators. By focusing on performance-based evaluation, organizations reduce the need for process-oriented micromanagement, which can stifle the flexibility and autonomy that gig workers value.

- Establish a Feedback Mechanism - Implementing real-time, continuous feedback systems is crucial for the success of the O-B model. A transparent feedback loop ensures that gig workers can improve their performance and align better with outcome expectations (De Stefano & Aloisi, 2019). Performance reviews based on these metrics should not just focus on what is done but on how well it aligns with the outcomes. Gig platforms can integrate user ratings, peer reviews, and client feedback as part of this mechanism.

- Enable Autonomy with Accountability - For the O-B approach to be effective, gig workers must be granted autonomy in how they complete tasks, so long as the outcome meets the established criteria. This autonomy encourages innovation, productivity, and personal responsibility (Kuhn & Maleki, 2017; Benkler & Faris, 2018). However, alongside this flexibility, the O-B model ensures accountability, as workers are evaluated based on the results they deliver rather than the processes they follow. This balance fosters trust and engagement while mitigating conflicts related to task execution.

- Incentivize Performance with Outcome-Based Compensation - To strengthen the link between effort and reward, compensation in an O-B model should be directly tied to the outcomes achieved. Traditional time-based compensation models often fail to reflect the complexities and impact of the gig economy(Katz & Krueger, 2016; Sundararajan, 2016). An outcome-based compensation system not only promotes fairness but also motivates gig workers to focus on delivering high-quality results, knowing that their earnings are tied to the value they create.

- Ensure Stakeholder Alignment - The success of the O-B model depends on alignment between platform operators, gig workers, and regulatory bodies. Clear communication about the expectations, rights, and responsibilities of all parties involved ensures that everyone operates under the same performance framework (Bennis & Thomas, 2022). This alignment minimizes disputes and promotes a culture of collaboration.

- Iterate and Adapt the Framework - Finally, the O-B model must remain adaptable to the changing conditions of the gig economy. As new technologies, regulatory frameworks, and market demands evolve, the framework should undergo periodic reviews to ensure its relevance and effectiveness. Continuous improvement processes can be employed to refine outcome-based metrics, feedback systems, and compensation structures.

- Task Completion Time: Measuring the time taken to complete tasks can be a key indicator of efficiency and adaptability. Shorter completion times for similar tasks can reflect worker productivity and their ability to operate efficiently in a flexible work environment (De Stefano & Aloisi, 2019).

- Quality of Output: Evaluating the quality of the delivered service or product is critical to assessing outcomes in the O-B framework. Quality can be measured through customer feedback, ratings, or adherence to predefined standards. Studies have shown that incentivizing quality can enhance both worker satisfaction and organizational performance (Kuhn & Maleki, 2017).

- Customer Satisfaction: This is a key variable that can be measured through surveys, ratings, and feedback on gig platforms. Positive customer reviews often correlate with higher-quality outcomes, creating a reliable performance metric in a gig economy environment (Sundararajan, 2016).

- Consistency and Reliability: Metrics that evaluate the frequency and reliability of work completed—such as the ratio of tasks completed to deadlines met—can help assess the accountability of gig workers. Consistency in delivering outcomes across tasks reflects both worker reliability and the effectiveness of the O-B model (Benkler & Faris, 2018).

- Worker Engagement: Measuring gig worker engagement, often through retention rates, participation in platform activities, or self-reported satisfaction, can provide insight into how the O-B model influences long-term worker motivation and productivity (Katz & Krueger, 2016).

- Earnings or Compensation per Outcome: Evaluating how fairly gig workers are compensated for each task or outcome relative to effort or time spent is crucial in ensuring fairness and motivating high performance (De Stefano & Aloisi, 2019).

4.2. Implications for Organizations & Practitioners

- Enhanced Performance and Accountability - Implementing an outcome-based approach within the gig economy fosters a culture of performance excellence and accountability (Smith et al., 2022). By setting clear objectives and expectations tied to specific outcomes, organizations empower gig workers to take ownership of their tasks and strive for excellence (Benkler & Faris, 2018). This heightened accountability not only drives individual performance but also contributes to overall organizational success (Cheng et al., 2021).

- Optimized Resource Allocation - A focus on outcomes allows organizations to allocate resources more effectively within the gig economy (Chen et al., 2021). By prioritizing tasks based on their potential impact on desired outcomes, organizations can ensure that resources are directed toward activities that generate the greatest value (Rogers, 2016). This optimization of resource allocation enhances efficiency and maximizes return on investment (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2008).

- Agility and Adaptability - Outcome-based approaches promote agility and adaptability within organizations operating in VUCA environments (Smith & Brown, 2021). By defining outcomes as the primary measure of success, organizations can pivot quickly in response to changing market dynamics or emerging opportunities (Johnson & Patal, 2022). This flexibility enables organizations to remain competitive and resilient in the face of uncertainty and ambiguity (Cheng et al., 2021).

- Improved Decision-Making - Clear outcome expectations provide organizations with valuable insights for informed decision-making (Katz & Krueger, 2016). By tracking progress towards predefined outcomes, organizations can identify areas of strength and areas needing improvement, enabling them to make data-driven decisions to optimize performance and strategy (De Stefano & Aloisi, 2019).

- Enhanced Stakeholder Satisfaction - Aligning gig work with measurable outcomes enhances stakeholder satisfaction across the board (Benkler & Faris, 2018). Clients benefit from the assurance that their objectives will be met, leading to increased trust and loyalty (Sundararajan, 2016). Gig workers experience greater satisfaction as they see the direct impact of their contributions, leading to higher levels of engagement and retention (Chen et al., 2021).

- Promotion of Innovation - An outcome-based approach fosters a culture of innovation within organizations (O'Reilly & Tushman, 2008). By encouraging gig workers to focus on achieving specific outcomes rather than adhering to rigid processes, organizations create an environment conducive to experimentation and creativity (Smith & Brown, 2021). This promotes innovation and continuous improvement, driving long-term success (Johnson & Patal, 2022).

- Alignment with Organizational Goals - Outcome-based approaches ensure that gig work aligns closely with organizational goals and strategic objectives (Sundararajan, 2016). By defining outcomes that directly contribute to organizational success, organizations ensure that gig workers' efforts are aligned with broader business priorities, fostering unity of purpose and direction (Katz & Krueger, 2016).

4.3. Future Research Directions

- Implementation and Effectiveness: Future research could focus on empirically evaluating the implementation and effectiveness of outcome-based approaches within the gig economy across different industries and organizational contexts. This could involve longitudinal studies assessing the impact of outcome-based incentives on gig worker performance, client satisfaction, and organizational outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Given the growing reliance on digital platforms and algorithms in the gig economy, there is a need to examine the ethical implications of outcome-based approaches. Research could explore issues such as algorithmic bias, worker exploitation, and privacy concerns, and develop ethical frameworks to guide the implementation of outcome-based models.

- Stakeholder Perspectives: Understanding the perspectives of various stakeholders, including gig workers, platform operators, clients, and regulatory bodies, is crucial for informing the design and adoption of outcome-based approaches. Future research could employ qualitative methods to explore stakeholder perceptions, attitudes, and experiences related to outcome-based incentives in the gig economy.

- Long-Term Impact: Investigating the long-term impact of outcome-based approaches on gig worker well-being, career trajectories, and socio-economic outcomes is essential for ensuring sustainable and equitable employment practices. Longitudinal studies tracking gig workers over extended periods can provide valuable insights into the enduring effects of outcome-based models.

- Contextual Factors: Recognizing the influence of contextual factors such as regulatory environments, cultural norms, and technological advancements on the implementation and effectiveness of outcome-based approaches is crucial. Comparative studies across different countries and regions can help identify contextual factors that shape the adoption and outcomes of outcome-based models in the gig economy.

- Organizational Strategies: Exploring organizational strategies for integrating outcome-based approaches into broader talent management practices and organizational cultures is essential. Research could examine how organizations communicate performance expectations, provide feedback, and foster a results-oriented mindset among gig workers to maximize the benefits of outcome-based incentives.

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1. Adams, J. S. (1963). Toward an understanding of inequity. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 67(5), 422-436. [CrossRef]

- 2. Bennett, N., & Lemoine, J. (2014). What VUCA really means for you. Harvard Business Review, 92(1/2), 27-31.

- 3. Benkler, Y., & Faris, R. (2018). Principled artificial intelligence: Mapping consensus in ethical and rights-based approaches to principles for AI. *Harvard Kennedy School*. Retrieved from https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/41492384/Principled_Artificial_Intelligence.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- 4. Benkler, Y., & Faris, R. (2018). Peer production: A model for a new economy. Harvard University Press.

- 5. Bennis, W., & Thomas, R. J. (2022). Geeks and gurus: The role of leadership in the new economy. Leadership Quarterly, 33(4), 101-113. [CrossRef]

- 6. Burtch, G., Carnahan, S., & Greenwood, B. N. (2018). Can you gig it? An empirical examination of the gig economy and entrepreneurial activity. Management Science.

- 7. Bollerslev, T., & Todorov, V. (2021). Volatility: A statistical approach. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 13(1), 273-295. [CrossRef]

- 8. Bower, J. L., & Christensen, C. M. (1995). Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. Harvard Business Review, 73(1), 43-53.

- 9. Bradley, R., & Nolan, R. (1998). Sense and respond: Capturing value in the network era. Harvard Business Review, 76(3), 88-98.

- 10. Bollerslev, T., & Todorov, V. (2021). Tails, fears, and risk premia. *Journal of Econometrics, 213*(1), 29–48. [CrossRef]

- 11. Benkler, Y., & Faris, R. (2018). Peer production: A model for a new economy. Harvard University Press.

- 12. Benkler, Y., & Faris, R. (2018). Peer production: A model for a new economy. Harvard University Press.

- 13. Bennis, W., & Thomas, R. J. (2022). Geeks and gurus: The role of leadership in the new economy. Leadership Quarterly, 33(4), 101-113.

- 14. Bradley, L., & Nolan, R. (1998). Sense and respond: Capturing value in the network era. *Harvard Business Review Press*.

- 15. Candelon, B., & Joëts, M. (2022). The dynamics of volatility in financial markets: Implications for market participants. Journal of Banking & Finance, 132, 106360. [CrossRef]

- 16. Chen, L., Wang, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2021). Dynamic resource allocation strategy of supply chain considering market demand volatility. *Sustainable Production and Supply Chain Management, 7(2), 87–96. [CrossRef]

- 17. Cheng, M., Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2021). Agility and resilience in a post-COVID-19 environment: The case of small tourism businesses in Australia. *Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights, 4(2), 170–184. [CrossRef]

- 18. Christensen, C. M., & Bower, J. L. (1995). Disruptive technologies: Catching the wave. Harvard Business Review.

- 19. Cramer, J., & Krueger, A. B. (2016). Disruptive change in the taxi business: The case of Uber. American Economic Review, 106(5), 177-182. [CrossRef]

- 20. De Stefano, V., & Aloisi, A. (2016). The rise of the ‘just-in-time’ workforce: On-demand work, crowdwork and labor protection in the ‘gig economy’. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 40(3), 529-575. [CrossRef]

- 21. Dutton, J. E., & Glynn, M. A. (2021). The emergence of trust in organizations: The role of trust in organizational resilience. Academy of Management Perspectives, 35(1), 92-108. [CrossRef]

- 22. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press. [CrossRef]

- 23. Dweck, C. S., & Yeager, D. S. (2019). Mindsets: A view from two eras. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(3), 481-496.

- 24. Dalal, R. S., & Bonaccio, S. (2022). Decision-making and adaptability. *Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9*, 189–213. [CrossRef]

- 25. De Stefano, V., & Aloisi, A. (2019). Just a gig? The digitalization of work and human capital. *Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12*(1), 135–152. [CrossRef]

- 26. Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum Press.

- 27. Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Agency theory: An assessment and review. Academy of Management Review, 14(1), 57-74. [CrossRef]

- 28. Friedman, G. (2014). "Workers without employers: Shadow corporations and the rise of the gig economy." Review of Keynesian Economics, 2(2), 171-188. [CrossRef]

- 29. Friedman, G. (2014). Workers without employers: Shadow corporations and the rise of the gig economy. Review of Radical Political Economics, 48(4), 593-610. [CrossRef]

- 30. Garcia, J., de Sa, A. M., & Mendonça, J. F. (2020). Complexity in supply chains: A systematic literature review. *International Journal of Production Economics, 230*, Article 107879. [CrossRef]

- 31. Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331-362. [CrossRef]

- 32. Garcia, R., Inoue, C., & Hoshino, T. (2020). Complexity in supply chain dynamics: A network analysis approach. International Journal of Production Economics, 225, 107569. [CrossRef]

- 33. Gilbert, M., Fajardo, R., & Doyle, A. (2020). Exploring the future of gig economy work: Shaping the workforce in an age of uncertainty. Journal of Organizational Change Management.

- 34. Gandini, A. (2019). Labour process theory and the gig economy. Human Relations, 72(6), 1039-1056. [CrossRef]

- 35. Healy, J., & Pekarek, A. (2020). Work, control and employment relationships in the gig economy. Work, Employment and Society, 34(3), 478-495. [CrossRef]

- Heath, C., & Sitkin, S. B. (2001). Big-b tents and small umbrellas: Lessons for organizational learning from the complexity of the physical world. Organization Science, 12(5), 731-735. [CrossRef]

- 37. Howard, J., & Borenstein, J. (2018). The gig economy and worker benefits: Emerging issues in employment law. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(1), 31-40. [CrossRef]

- 38. Jaskyte, K., & Lebedeva, N. (2021). Ambiguity in nonprofit management. *Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 32*(1), 5–23. [CrossRef]

- 39. Johnson, M., & Lee, J. (2018). Uncertain regulatory environments and organizational responses: The case of U.S. healthcare. *Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37*(3), 589–616. [CrossRef]

- 40. Jaskyte, K., & Lebedeva, N. (2021). Ambiguity in organizational decision-making: The effects of emotional intelligence and psychological safety. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 225-239. [CrossRef]

- 41. Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305-360. [CrossRef]

- 42. Johnson, R. E., & Lee, K. (2018). Managing regulatory uncertainty: Strategic responses in the healthcare sector. Journal of Business Research, 89, 318-328. [CrossRef]

- 43. Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2016). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. NBER Working Paper No. 22667. [CrossRef]

- 44. Kachaner, N., Volini, E., & Seo, J. (2021). The future of work: How to keep pace with the rapid changes in the workplace. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from McKinsey.

- 45. Kuhn, K. M., & Maleki, A. (2017). Work on demand: How the gig economy is changing the nature of work and employment. Industrial Relations Research Association.

- 46. Kuhn, K. M., & Galloway, T. L. (2019). "Expanding perspectives on gig work and gig workers." Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 12(3), 358-362. [CrossRef]

- 47. Kuhn, K. M., & Maleki, A. (2017). "Micro-entrepreneurs, dependent contractors, and instaserfs: Understanding online labor platform workforces." Academy of Management Perspectives, 31(3), 183-200. [CrossRef]

- 48. Kachaner, N., Volini, E., & Seo, J. (2021). Organizing for the future: Six strategies for organizational success. *McKinsey & Company*.

- 49. Katz, L. F., & Krueger, A. B. (2016). The rise and nature of alternative work arrangements in the United States, 1995–2015. *National Bureau of Economic Research*. [CrossRef]

- 50. Liu, Y., Guo, Y., & Yu, Y. (2021). Understanding ambiguity in organizational decision-making: The role of leadership and employee involvement. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 28(2), 137-151. [CrossRef]

- 51. Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist.

- 52. Malik, R.; Visvizi, A.; Skrzek-Lubasi ´ nska, M. The GigEconomy: Current Issues, the Debate,and the New Avenues of Research.Sustainability 2021, 13, 5023. [CrossRef]

- 52. Meyer, C. B. (2014). Short-termism and corporate performance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 29, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- 53. O'Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2008). Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator's dilemma. *Research in Organizational Behavior, 28*, 185–206. [CrossRef]

- 54. Peticca-Harris, A., DeGama, N., & Ravishankar, M. N. (2020). Postcapitalist precarious work and those in the ‘drivers’ seat: Exploring the motivations and lived experiences of Uber drivers in Canada. Organization, 27(1), 36-59. [CrossRef]

- 55. Piore, M. J., & Sabel, C. F. (1984). The second industrial divide: Possibilities for prosperity. *Basic Books*.

- 56. Perrin, M. (2015). "Outcome-based management: New rules for business performance." Journal of Business Strategy, 36(5), 20-27. [CrossRef]

- 57. Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2021). Entrepreneurship and the Fourth Industrial Revolution. *Routledge*.

- 58. Rousseau, D. M., & Tett, R. P. (2020). Organizational climate: Past, present, and future. *Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 7*, 87–107. [CrossRef]

- 59. Ratten, V., & Jones, P. (2021). The influence of social capital on entrepreneurial success in a VUCA world. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 27(3), 570-590. [CrossRef]

- 60. Rousseau, D. M., & Tett, R. P. (2020). A new model for organizational behavior: Understanding how organizations can thrive in uncertainty. Academy of Management Perspectives, 34(1), 70-84. [CrossRef]

- Smith, J., & Brown, A. (2021). Adaptability and agility: Key determinants of organizational resilience in the face of uncertainty. *Journal of Change Management, 21*(2), 81–101. [CrossRef]

- 61. Smith, J., Johnson, M., & Brown, A. (2022). Managing volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous times: The role of leader humility. *The Leadership Quarterly, 33*(2), Article 101642. [CrossRef]

- 62. Sundararajan, A. (2016). The sharing economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism. *The MIT Press*.

- 63. Snowden, D. J., & Boone, M. (2007). A leader's framework for decision making. Harvard Business Review, 85(11), 68-76.

- 64. Silva, A., & Rodrigues, J. (2019). "Outcome-based approaches in project management: A critical review." International Journal of Project Management, 37(4), 556-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.01.007.

- 65. Sundararajan, A. (2016). The sharing economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism. MIT Press.

- 66. Sundararajan, A. (2016). The sharing economy: The end of employment and the rise of crowd-based capitalism. MIT Press.

- 67. Todoli-Signes, A. (2017). The ‘gig economy’: Employee, self-employed or the need for a special employment regulation? Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 23(2), 193-205. [CrossRef]

- 68. Teece, D. J. (2014). A dynamic capabilities-based entrepreneurial theory of the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(1), 8-37. [CrossRef]

- 69. Todorov, V., & Bollerslev, T. (2021). The impact of volatility and uncertainty on economic decision-making. Journal of Economic Perspectives.

- 70. U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2020). Contingent and alternative employment arrangements. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/news.release/conemp.nr0.htm.

- 71. Veen, A., Barratt, T., & Goods, C. (2020). Platform capitalism and the gig economy: Investigating the role of digital labour platforms in shaping modern work and its implications for worker flexibility. Journal of Industrial Relations, 62(4), 485-500. [CrossRef]

- 72. Wang, Y., & Chen, Y. (2017). Navigating technological disruptions: Interpreting ambiguous signals in the telecommunications industry. *Strategic Management Journal, 38*(9), 1875–1892. [CrossRef]

- 73. Wood, A. J., Graham, M., Lehdonvirta, V., & Hjorth, I. (2019). "Good gig, bad gig: Autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy." Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 56-75. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).