1. Introduction

Recent data highlight the promise of cancer vaccines for melanoma, and likely for other cancers [

1,

2,

3]. Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) attributed to vaccines against human cancers are commonly limited to grade 1 and 2 severity but can occasionally be more serious and dose-limiting [

1]. Therefore, although these TRAEs are not generally dose-limiting in the context of vaccines against human cancer, they are important to study because they may reflect autoimmune disease or predict potential clinical benefit [

4,

5].

The impact of biologic sex on clinical outcomes is a high priority for the National Institutes of Health but is understudied. We recently identified sex-related differences in clinical benefit, as biological males have better durable long-term survival than females receiving a multipeptide melanoma vaccine [

3]. A similar trend favoring males was identified in patients receiving checkpoint blockade cancer therapy, for metastatic melanoma and other advanced cancers [

6,

7]. Further, other cancer therapies including immunotherapy have induced more frequent general TRAEs and immune-related TRAEs in females than in males [

8,

9]. Very little is known about the sex-related differences in TRAEs induced by cancer vaccines. Detailed analysis of differences by sex in incidence and grade of TRAEs in cancer vaccine therapy might help to guide the risk-benefit ratio discussion.

The objective of this current study was to determine whether there are differences in TRAEs as a function of biologic sex in the context of multipeptide melanoma vaccines, independent of age, American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) stage and treatment arm. We examined the sex-related differences in TRAEs in the context of the Mel44 peptide vaccine trial (NCT00118274), in which there was a difference in clinical benefit between males and females [

3]. We hypothesized that biological females would experience higher rates and grades of TRAEs.

2. Materials and Methods

Clinical Trial Design

Mel44 was a multicenter randomized trial approved by the institutional review board designed to test the safety and immunogenicity of two different peptide vaccine combinations as well as the potential for clinical benefit with the addition of low-dose cyclophosphamide (CY) pretreatment, for which the trial design and primary results have been reported [

10]. Briefly, the study enrolled patients with resected high-risk melanoma, AJCC (v6) stage IIB-IV, clinically free of disease, and randomized patients equally among four treatment arms in a 2x2 design to either of two peptide vaccine regimens, with or without low-dose CY pre-treatment. Both vaccine regimens contained 12 class 1 major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-restricted melanoma peptides stimulating CD8+ T cells (12MP), but the vaccine regimens differed in the peptides designed to stimulate CD4+ T cells. Patients on arms A, B received a nonspecific tetanus helper peptide (Tet); patients on arms C, D received six melanoma-associated class 2 MHC-restricted melanoma helper peptides to stimulate CD4+ T cells (6MHP) (Supplemental

Table S1) [

11].

TRAE Data Collection

The trial was monitored continuously for TRAEs with National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 3.0 (v3). TRAEs were reviewed weekly by patient interview with a study clinician and recorded in the case report forms and clinical record. TRAEs were given one of the following labels according to the study clinician’s assessment of relatedness to vaccine treatment: “unrelated,” “unlikely,” “possible,” “probable,” or “definite,” according to National Cancer Institute Guidelines for Investigators [

12]. Attributions of “possible,” “probable,” or “definite” were deemed treatment-related. Protocol treatment was to be discontinued for unexpected grade 3, ocular grade 1, allergic grade 2, or higher TRAEs. TRAE data have been stored in the University of Virginia C3TO Cancer Center clinical trials office database.

Data Analyses

The number of TRAEs, organized by CTCAE v3 toxicity category/unique descriptions, was reported in the study population. The maximum grade of any TRAE for each patient, the number of TRAEs for each patient, and the maximum grade of unique TRAEs for each patient were extracted. Patient data were organized by the maximum grade of any TRAEs for that patient, by study arm, and by biological sex. Only TRAEs that occurred in more than 5% of the population were further analyzed. The proportion of patients with each grade of TRAE (maximum per patient) as well as the cumulative proportions of patients with one or more different TRAEs were plotted on cumulative frequency curves, for each sex. The incidence rates for each of the unique TRAEs were compared between the biological sexes using Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The total number of TRAEs and the average grade for each TRAE were compared between males and females by t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test, as appropriate. P-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Using a linear mixed-effects model with patient and type of TRAE as the random effects, the incidence rate of TRAEs was modeled as a function of biological sex, age, AJCC stage and treatment arm. Maximum TRAE grade was modeled as a function of biological sex, age, AJCC staging class and treatments using a mixed-effect ordinal logistic regression with patient and type of TRAE as random effects. (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2.3 software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) with packages lme4, car and ordinal.

3. Results

One hundred seventy patients were enrolled in the Mel44 clinical trial. Adverse events were evaluated for the entire cohort, including 3 patients found ineligible on post-review [

10]. Treatment arms had similar numbers of patients (41, 43, 42, 44 for Arms A-D, respectively), with males predominating (67%).

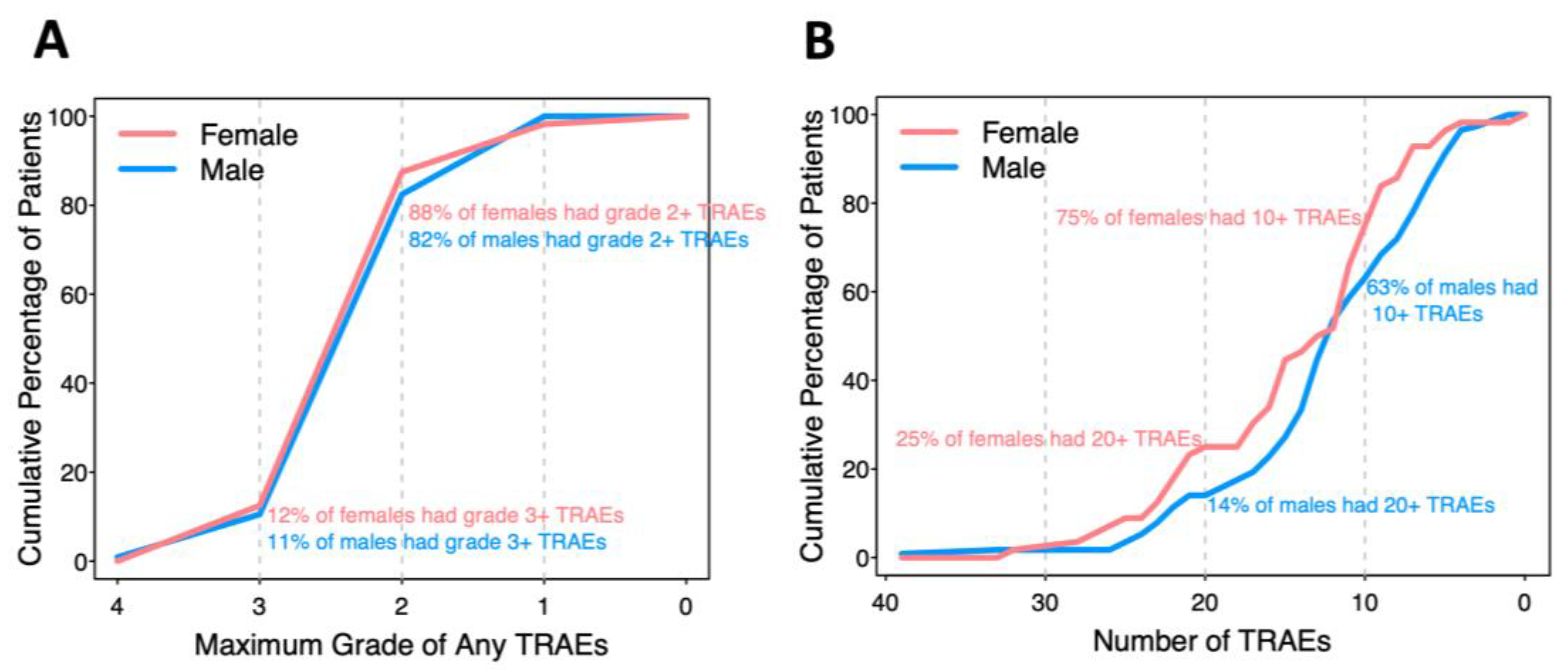

There were 2648 reported TRAEs involving almost every patient (99.4%), with 126 unique CTCAE descriptions ranging from grade 1 to 4. In analysis of grade, patients who did not experience a TRAE were assigned grade 0 for that TRAE. Some TRAEs were reported multiple times (up to 4) in the same patient. No treatment-related deaths or deaths on the study occurred. When a TRAE was reported more than once for a patient, the maximum grade was recorded, and the number with maximum grades 1-4 were 1770 (81%), 368 (17%), 39 (1.8%), and 1 (0.05%), respectively. Forty-two TRAEs occurred in at least 5% of participants and are the focus of comparisons by biologic sex. The percentages of patients with maximum grade 4, 3, 2, or 1 of any TRAE in each patient are presented in a cumulative incidence curve (

Figure 1A). Twelve percent of females and 11% of males had at least one TRAE grade 3 or above, while 88% of females and 82% of males had at least one TRAE grade 2 or above.

Most of the patients experienced multiple TRAEs (

Figure 1B). Twenty-five percent of females and 14% of males experienced 20 or more different TRAEs; 75% of females and 63% of males experienced 10 or more different TRAEs. Each male and female experienced an average of 12 or 14 TRAEs, respectively (p=0.077).

Total TRAEs by grade in the overall study population, as well as by study arms and sex, are presented in Supplemental

Table S2. Rates of patients with grade 0-1, grade 2, or grade 3-4 TRAEs in were similar by sex in arms A, B and C. In arm D, females trended toward higher grades of TRAEs than males (p = 0.052).

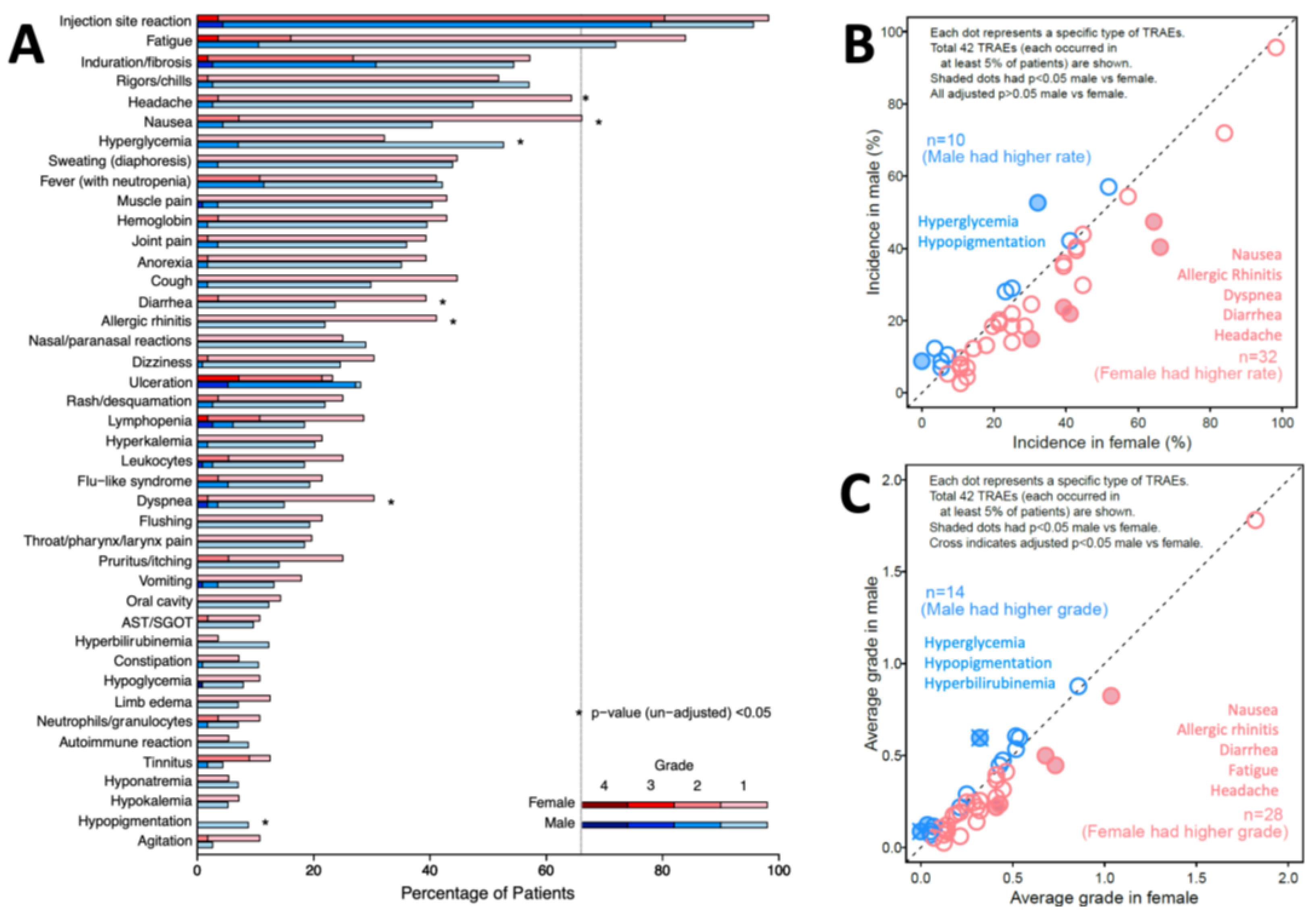

TRAE incidence is also presented by sex and grade (

Figure 2A). Distribution of grade is different between sex for 8 TRAEs. Four TRAEs occurred in more than half of patients, for both females and males: injection site reaction (98%, 96%, respectively), fatigue (84%, 72%), induration or fibrosis (57%, 54%), and rigors/chills (52%, 57%). Thirty-two unique TRAEs occurred more frequently in females, while 10 occurred more frequently in males. Before adjustment for multiple comparisons, 5 of these TRAEs were more frequent (p < 0.05) in females: nausea (p=0.002), allergic rhinitis (p=0.009), dyspnea (p=0.018), diarrhea (p=0.035), and headache (p=0.038); two were more frequent in males: hyperglycemia (p=0.012) and hypopigmentation (p=0.032), as marked with asterisks in

Figure 2A. However, with adjustment, p > 0.05 for all those TRAEs (

Figure 2B).

TRAE severity was calculated as the mean of the maximum grades of each TRAE across the population, assigning grade 0 for those without that TRAE. Females experienced higher average grades in 28 unique TRAEs, while males experienced higher average grades in 14 TRAEs (

Figure 2C). Without correcting for other covariates or p-value adjustment, females experienced significantly higher average grade for 5 TRAEs: nausea (p=0.004), allergic rhinitis (p=0.015), diarrhea (p=0.028), fatigue (p=0.046) and headache (p=0.048). Males experienced significantly higher average grade in 3 TRAEs, including hypopigmentation (p=0.001), hyperglycemia (p=0.002) and hyperbilirubinemia (p=0.030). Adjusted (p<0.05) were observed for increased hypopigmentation (p=0.042) and hyperglycemia (p=0.042) in males (

Figure 2C).

Grade 1-2 TRAEs are usually well-tolerated and not dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs). Severe TRAEs could impact patient outcomes and when considered DLTs, they limit completion of investigational therapy. Among the 170 patients, we previously reported10 that 15 (8.8%) experienced grade 3-4 treatment-related DLTs. We have now identified that they represented 11 males and 4 females. These represented 9.7% of males and 7.1% of females (p = 0.59). Thus, there was no sex-related difference in participants with grade 3-4 DLTs.

The rates of the 42 TRAEs by sex were assessed in a linear mixed-effects model, adjusting by age, AJCC staging, and vaccine treatments. Considering patient and TRAE type as random effects, biological sex did not influence the incidence of TRAE (p=0.105). However, there is a 7% increase in the odds of the incidence of TRAEs for patients treated with 12MP + Tet, than patients treated with 12MP + 6MHP (p=0.001,

Table 1). Similarly, in an ordinal mixed-effects logistic regression analysis, biological sex also did not influence the grades of TRAE (p=0.358). However, there was a 60% increase in the odds of experiencing higher grade TRAEs for patients who received 12MP + Tet than patients who received 12MP + 6MHP (p<0.001,

Table 2).

4. Discussion

We identified interesting trends for differences in incidence and grades of TRAEs as a function of biologic sex on this trial. There was a trend to higher numbers of TRAEs in females (p = 0.077,

Figure 1A), and to higher grades of TRAEs overall (p = 0.052,

Figure 1B). Initial assessments identified 8 (19%) TRAEs with different incidence in females or males, but none were different with adjustment for multiple comparisons (

Figure 2B). There were significantly higher grades of hyperglycemia and hypopigmentation in males, after correction for multiple comparisons (

Figure 2C). Overall, however, mixed-effect models did not support differences in TRAEs by biologic sex when controlling for other factors. On the other hand, the modeling supported that patients vaccinated with 12MP + Tet rather than those vaccinated with 12MP + 6MHP experienced greater TRAE frequency (p = 0.001) and severity (p < 0.001).

5. Conclusions

In prior work, we have reported that selected inflammatory TRAEs were associated with higher rates of immune response across several vaccine trials [

4]. Stronger immune responses may be associated with greater local toxicity due to inflammation at the vaccine sites and systemic toxicities mediated by cytokine release. However, we have recently identified more favorable long-term overall survival in patients on the Mel44 trial who were vaccinated with 12MP + 6MHP, than those vaccinated with 12MP + Tet, and specifically in males, despite lower CD8+ T cell responses rates with the 12MP + 6MHP vaccines [

3,

10]. Relationships between TRAEs and clinical outcome are likely complex, as TRAEs may reflect non-specific inflammatory effects as well as antigen-specific reactivities.

Study limitations include analysis of just one clinical trial. However, this clinical trial was multicenter and randomized, and included a sizeable number of patients for a phase II trial. It is possible that in a larger study, some of the TRAEs may differ in frequency even after correcting for multiple comparisons. However, this analysis supports safety of the multipeptide vaccines in both males and females and does not support the hypothesis that TRAEs were more frequent in females. Further, in mixed models controlling for sex, age, stage and treatment, TRAEs were significantly associated with the vaccine regimen including tetanus toxoid peptide.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1: Treatments assigned for patients enrolled on Mel44 trial in 4 study arms; Table S2: TRAE counts in Mel44 clinical vaccine trial, organized by grade, vaccine arm and biological sex.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, CEL and CLS.; methodology, CEL and CLS; validation, CLS and RJ; formal analysis, CEL, RJ, and HZ; investigation, CLS; resources, CLS; data curation, CLS and CEL; writing—original draft preparation, CEL and RJ; writing—review and editing, CLS, ADS, and CEL; visualization, HZ and CLS; supervision, CLS; project administration, CLS; funding acquisition, CLS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

CLS has the following disclosures: research support to the University of Virginia from Celldex (funding, drug), GSK (funding), Merck (funding, drug), 3M (drug), Theraclion (device staff support); funding to the University of Virginia from Polynoma for PI role on the MAVIS Clinical Trial; funding to the University of Virginia for roles on Scientific Advisory Boards for Immatics and CureVac. CLS also receives licensing fee payments through the UVA Licensing and Ventures Group for patents for peptides used in cancer vaccines.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, as part of the clinical trial MEL44, which was approved the institutional review boards (IRB) at the 3 participating institutions (University of Virginia, MD Anderson Cancer Center at the University of Texas – Houston, and Fox Chase Cancer Center), with the University of Virginia at the lead institution (IRB-HSR #11491). Original approval was 9/24/2004. The most recent continuation approval was 2/14/2024. It was also performed with FDA approval (IND #12191) and is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00118274).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study prior to participating in this trial.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Merrick I. Ross, Naomi B. Haas, and Margaret von Mehren for their work on the Mel44 trial.

Conflicts of Interest

The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Weber JS, Carlino MS, Khattak A, Meniawy T, Ansstas G, Taylor MH, Kim KB, McKean M, Long GV, Sullivan RJ, et al.: Individualised neoantigen therapy mRNA-4157 (V940) plus pembrolizumab versus pembrolizumab monotherapy in resected melanoma (KEYNOTE-942): a randomised, phase 2b study. Lancet 2024, 403:632-644.

- Kjeldsen JW, Lorentzen CL, Martinenaite E, Ellebaek E, Donia M, Holmstroem RB, Klausen TW, Madsen CO, Ahmed SM, Weis-Banke SE, et al.: A phase 1/2 trial of an immune-modulatory vaccine against IDO/PD-L1 in combination with nivolumab in metastatic melanoma. Nature Medicine 2021, 27:2212-2223.

- Ninmer EK, Zhu H, Chianese-Bullock KA, von Mehren M, Haas NB, Ross MI, Dengel LT, Slingluff CL, Jr.: Multipeptide vaccines for melanoma in the adjuvant setting: long-term survival outcomes and exploratory analysis of a randomized phase II trial. Nature Communications 2024.

- Hu Y, Smolkin ME, White EJ, Petroni GR, P.Y. N, Slingluff CL, Jr. Inflammatory Adverse Events are Associated with Disease-Free Survival after Vaccine Therapy among Patients with Melanoma. Annals of Surgical Oncology. 2014 2014;in press.

- Chianese-Bullock KA, Woodson EMH, Tao H, et al. Autoimmune Toxicities Associated with the Administration of Antitumor Vaccines and Low-Dose Interleukin-2. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2005;28(4):412-419. [CrossRef]

- Grassadonia A, Sperduti I, Vici P, et al. Effect of Gender on the Outcome of Patients Receiving Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors for Advanced Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Phase III Randomized Clinical Trials. J Clin Med. 2018;7(12):542. [CrossRef]

- Özdemir BC, Csajka C, Dotto GP, Wagner AD. Sex Differences in Efficacy and Toxicity of Systemic Treatments: An Undervalued Issue in the Era of Precision Oncology. JCO. 2018;36(26):2680-2683. [CrossRef]

- Duma N, Abdel-Ghani A, Yadav S, et al. Sex Differences in Tolerability to Anti-Programmed Cell Death Protein 1 Therapy in Patients with Metastatic Melanoma and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer: Are We All Equal?. Oncologist. 2019;24(11):e1148-e1155. [CrossRef]

- Unger JM, Vaidya R, Albain KS, et al. Sex Differences in Risk of Severe Adverse Events in Patients Receiving Immunotherapy, Targeted Therapy, or Chemotherapy in Cancer Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(13):1474-1486. [CrossRef]

- Slingluff CL, Jr., Petroni GR, Chianese-Bullock KA, et al. Randomized multicenter trial of the effects of melanoma-associated helper peptides and cyclophosphamide on the immunogenicity of a multipeptide melanoma vaccine. J Clin Oncol. Jul 20 2011;29(21):2924-32. [CrossRef]

- Slingluff CL Jr, Petroni GR, Olson W, et al. Helper T-cell responses and clinical activity of a melanoma vaccine with multiple peptides from MAGE and melanocytic differentiation antigens. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(30):4973-4980. [CrossRef]

- Institute NC: NCI Guidelines for Investigators: Adverse Event Reporting Requirements for DCTD (CTEP and CIP) and DCP INDs and IDEs. Edited by Institute NC. https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/aeguidelines.pdf: National Cancer Institute; 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).