Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Cardiac Alterations Related to Heart Aging

3. Oxidative Stress

3.1. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

3.2. Inflammation

4. Mechanism of Plant-Derived Antioxidants on Heart Aging

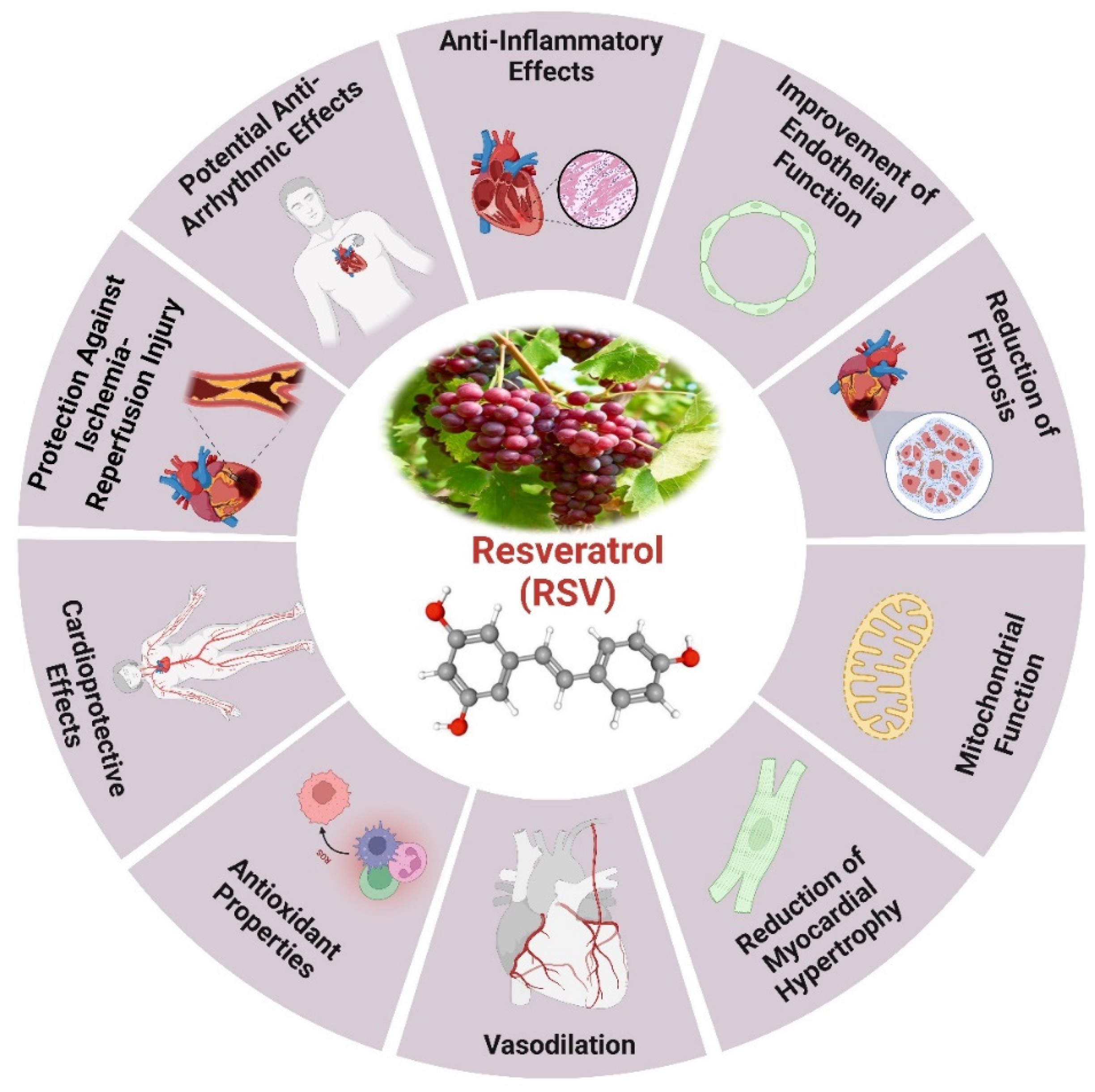

4.1. Resveratrol

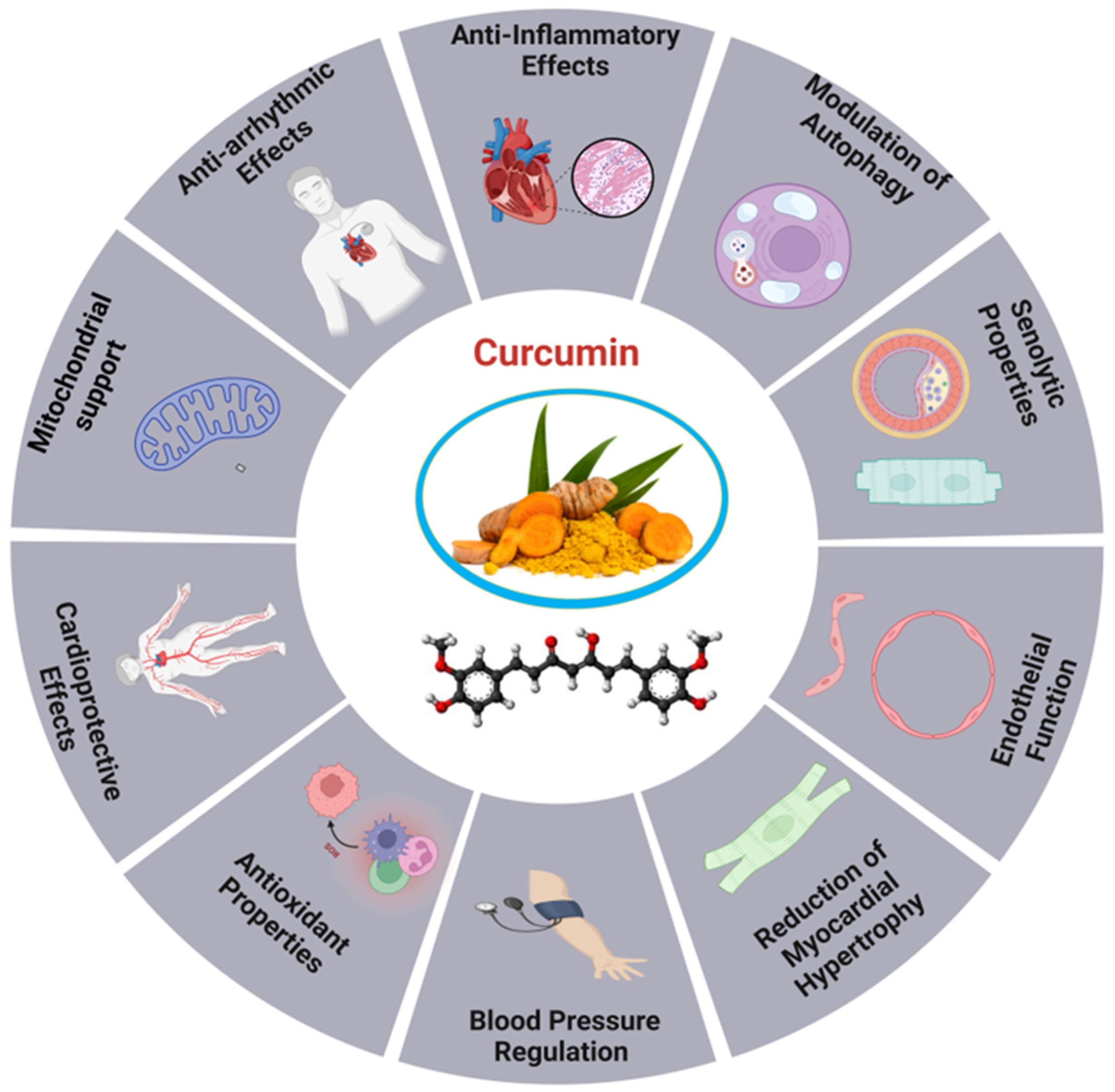

4.2. Curcumin

4.3. Quercetin

4.4. Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG)

5. Other Plant-Derived Antioxidants

5.1. Anthocyanins

5.2. Allicin

5.3. Ginkgolides Biloba

5.4. Berberine (BBR)

6. Future Prospective and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Sang, S.; McClements, D.J.; Chen, L.; Long, J.; Jiao, A.; Jin, Z.; Qiu, C. Polyphenols as plant-based nutraceuticals: health effects, encapsulation, nano-delivery, and application. Foods 2022, 11, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phu, H.T.; Thuan, D.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Posadino, A.M.; Eid, A.H.; Pintus, G. Herbal medicine for slowing aging and aging-associated conditions: efficacy, mechanisms and safety. Current vascular pharmacology 2020, 18, 369–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flora, G.D.; Nayak, M.K. A brief review of cardiovascular diseases, associated risk factors and current treatment regimes. Current pharmaceutical design 2019, 25, 4063–4084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, E.J.; Blaha, M.J.; Chiuve, S.E.; Cushman, M.; Das, S.R.; Deo, R.; De Ferranti, S.D.; Floyd, J.; Fornage, M.; Gillespie, C. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2017 update: a report from the American Heart Association. circulation 2017, 135, e146–e603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wu, Y.; Wei, J.; Xia, F.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, S.; Miao, J.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, C.; Yan, W. Global, regional, and national time trends in incidence for migraine, from 1990 to 2019: an age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2019. The Journal of Headache and Pain 2023, 24, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Yin, P. Cause-specific mortality for 240 causes in China during 1990–2013: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. The Lancet 2016, 387, 251–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Wang, H.; Zeng, X.; Yin, P.; Zhu, J.; Chen, W.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y. Mortality, morbidity, and risk factors in China and its provinces, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 2019, 394, 1145–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhavan, M.V.; Gersh, B.J.; Alexander, K.P.; Granger, C.B.; Stone, G.W. Coronary artery disease in patients≥ 80 years of age. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2018, 71, 2015–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare Engineering, J.o. Retracted: Changes of Multisectoral Collaboration and Service Delivery in Hypertension Prevention and Control before and after the 2009 New Healthcare Reform in China: An Interrupted Time-Series Study. 2022.

- Slivnick, J.; Lampert, B.C. Hypertension and heart failure. Heart failure clinics 2019, 15, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sciarretta, S.; Forte, M.; Castoldi, F.; Frati, G.; Versaci, F.; Sadoshima, J.; Kroemer, G.; Maiuri, M.C. Caloric restriction mimetics for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Cardiovascular research 2021, 117, 1434–1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-Y.; Chen, W.-W.; Gao, R.-L.; Liu, L.-S.; Zhu, M.-L.; Wang, Y.-J.; Wu, Z.-S.; Li, H.-J.; Gu, D.-F.; Yang, Y.-J. China cardiovascular diseases report 2018: an updated summary. Journal of geriatric cardiology: JGC 2020, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Saenjum, C.; Pattananandecha, T.; Apichai, S. Plant bioactives, aging research, and drug industry: procedures and challenges. In Plant Bioactives as Natural Panacea Against Age-Induced Diseases; Elsevier: 2023; pp. 447-468.

- Sinclair, A.; Saeedi, P.; Kaundal, A.; Karuranga, S.; Malanda, B.; Williams, R. Diabetes and global ageing among 65–99-year-old adults: Findings from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas. Diabetes research and clinical practice 2020, 162, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olayem, B.S.; Olaitan, O.B.; Akinola, A.B. Immunomodulatory Plant Based Foods, It’s Chemical, Biochemical and Pharmacological Approaches. Medicinal Plants-Chemical, Biochemical, and Pharmacological Approaches 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Huang, X.; Dou, L.; Yan, M.; Shen, T.; Tang, W.; Li, J. Aging and aging-related diseases: from molecular mechanisms to interventions and treatments. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; McVey, D.G.; Shen, D.; Huang, X.; Ye, S. Phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis. Journal of the American Heart Association 2023, 12, e031121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.-H.; Lei, M. Cardiomyocyte electrophysiology and its modulation: current views and future prospects. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2023, 378, 20220160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, A.S.F.; Zerolo, B.E.; López-Espuela, F.; Sánchez, R.; Fernandes, V.S. Cardiac system during the aging process. Aging and disease 2023, 14, 1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamo, C.E.; DeJong, C.; Hartshorne-Evans, N.; Lund, L.H.; Shah, S.J.; Solomon, S.; Lam, C.S. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2024, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Totoń-Żurańska, J.; Mikolajczyk, T.P.; Saju, B.; Guzik, T.J. Vascular remodelling in cardiovascular diseases: hypertension, oxidation, and inflammation. Clinical Science 2024, 138, 817–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, I.; Wang, X.; Pratt, R.E.; Dzau, V.J.; Hodgkinson, C.P. The impact of aging on cardiac repair and regeneration. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2024, 107682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saheera, S.; Krishnamurthy, P. Cardiovascular changes associated with hypertensive heart disease and aging. Cell transplantation 2020, 29, 0963689720920830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hastings, M.H.; Zhou, Q.; Wu, C.; Shabani, P.; Huang, S.; Yu, X.; Singh, A.P.; Guseh, J.S.; Li, H.; Lerchenmüller, C. Cardiac ageing: from hallmarks to therapeutic opportunities. Cardiovascular Research 2024, cvae124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldfield, C.J.; Duhamel, T.A.; Dhalla, N.S. Mechanisms for the transition from physiological to pathological cardiac hypertrophy. Canadian journal of physiology and pharmacology 2020, 98, 74–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.-F.; Kang, P.; Bai, H. The mTOR signaling pathway in cardiac aging. The journal of cardiovascular aging 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatif, M.; Madeo, F.; Sedej, S.; Kroemer, G. Antagonistic pleiotropy: the example of cardiac insulin-like growth factor signaling, which is essential in youth but detrimental in age. Expert opinion on therapeutic targets 2023, 27, 87–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.Y.; Sabatini, D.M. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology 2020, 21, 183–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannick, J.B.; Lamming, D.W. Targeting the biology of aging with mTOR inhibitors. Nature Aging 2023, 3, 642–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.-S.; Kim, J. Insulin-like growth factor-1 signaling in cardiac aging. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease 2018, 1864, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.S.; Sane, D.C.; Wannenburg, T.; Sonntag, W.E. Growth hormone, insulin-like growth factor-1 and the aging cardiovascular system. Cardiovascular research 2002, 54, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, J.A.; Coppotelli, G.; Rolo, A.P.; Palmeira, C.M.; Ross, J.M.; Sinclair, D.A. Mitochondrial and metabolic dysfunction in ageing and age-related diseases. Nature Reviews Endocrinology 2022, 18, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liao, X.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, Q. Mitophagy and its contribution to metabolic and aging-associated disorders. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2020, 32, 906–927. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, A.M.; Özsoy, M.; Zimmermann, F.A.; Feichtinger, R.G.; Mayr, J.A.; Kofler, B.; Sperl, W.; Weghuber, D.; Mörwald, K. Age-Related Deterioration of Mitochondrial Function in the Intestine. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, 4898217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.; Zhu, Y.; Deng, C.; Liang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Yang, Y. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1 (PGC-1) family in physiological and pathophysiological process and diseases. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2024, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Du, T.; Long, T.; Liao, X.; Dong, Y.; Huang, Z.-P. Signaling cascades in the failing heart and emerging therapeutic strategies. Signal transduction and targeted therapy 2022, 7, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proshkina, E.; Solovev, I.; Shaposhnikov, M.; Moskalev, A. Key molecular mechanisms of aging, biomarkers, and potential interventions. Molecular biology 2020, 54, 777–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karamanos, N.K.; Theocharis, A.D.; Piperigkou, Z.; Manou, D.; Passi, A.; Skandalis, S.S.; Vynios, D.H.; Orian-Rousseau, V.; Ricard-Blum, S.; Schmelzer, C.E. A guide to the composition and functions of the extracellular matrix. The FEBS journal 2021, 288, 6850–6912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halper, J. Basic components of connective tissues and extracellular matrix: fibronectin, fibrinogen, laminin, elastin, fibrillins, fibulins, matrilins, tenascins and thrombospondins. Progress in heritable soft connective tissue diseases 2021, 105–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lunde, I.G.; Rypdal, K.B.; Van Linthout, S.; Diez, J.; González, A. Myocardial fibrosis from the perspective of the extracellular matrix: mechanisms to clinical impact. Matrix Biology 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shan, L.; Wang, F.; Zhai, D.; Meng, X.; Liu, J.; Lv, X. Matrix metalloproteinases induce extracellular matrix degradation through various pathways to alleviate hepatic fibrosis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 161, 114472. [Google Scholar]

- Antar, S.A.; Ashour, N.A.; Marawan, M.E.; Al-Karmalawy, A.A. Fibrosis: types, effects, markers, mechanisms for disease progression, and its relation with oxidative stress, immunity, and inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, K.E.; Pontes, M.H.B.; Cantão, M.B.S.; Prado, A.F. The role of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in cardiac remodeling and dysfunction and as a possible blood biomarker in heart failure. Pharmacological Research 2024, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Huang, J.; He, S.; Du, R.; Shi, W.; Wang, Y.; Du, D.; Du, Y.; Liu, Q.; Wang, Y. Senescent endothelial cells’ response to the degradation of bioresorbable scaffold induces intimal dysfunction accelerating in-stent restenosis. Acta Biomaterialia 2023, 166, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Ren, C.; Hu, J.; Greenberg, D.A.; Chen, T.; Xie, L.; Jin, K. Age-related impairment of vascular structure and functions. Aging and disease 2017, 8, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Đorđević, D.B.; Koračević, G.P.; Đorđević, A.D.; Lović, D.B. Hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of Hypertension 2024, 10, 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oknińska, M.; Mączewski, M.; Mackiewicz, U. Ventricular arrhythmias in acute myocardial ischaemia—Focus on the ageing and sex. Ageing Research Reviews 2022, 81, 101722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, L.A.; Young, A.; Li, H.; Billcheck, H.O.; Wolf, M.J. Loss of endogenously cycling adult cardiomyocytes worsens myocardial function. Circulation Research 2021, 128, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, M.L.; Brunt, K.R.; Kirk, J.A.; Kleinbongard, P.; Calvert, J.W.; de Castro Brás, L.E.; DeLeon-Pennell, K.Y.; Del Re, D.P.; Frangogiannis, N.G.; Frantz, S. Guidelines for in vivo mouse models of myocardial infarction. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2021, 321, H1056–H1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-García, V.A.; Alameda, J.P.; Page, A.; Casanova, M.L. Role of NF-κB in ageing and age-related diseases: lessons from genetically modified mouse models. Cells 2021, 10, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, O.O.; Kipp, Z.A.; Bates, E.A.; da Silva, A.A.; Taylor, L.C.; Martinez, G.J.; Lee, W.-H.; Creeden, J.F.; Hinds Jr, T.D.; Stec, D.E. Loss of hepatic PPARα in mice causes hypertension and cardiovascular disease. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology 2023, 325, R81–R95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzeroni, D.; Villatore, A.; Souryal, G.; Pili, G.; Peretto, G. The aging heart: a molecular and clinical challenge. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 16033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyane, T.S.; Jere, S.W.; Houreld, N.N. Oxidative stress in ageing and chronic degenerative pathologies: molecular mechanisms involved in counteracting oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23, 7273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobo, V.; Patil, A.; Phatak, A.; Chandra, N. Free radicals, antioxidants and functional foods: Impact on human health. Pharmacognosy reviews 2010, 4, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martemucci, G.; Portincasa, P.; Centonze, V.; Mariano, M.; Khalil, M.; D’Alessandro, A.G. Prevention of oxidative stress and diseases by antioxidant supplementation. Medicinal Chemistry 2023, 19, 509–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratovcic, A. Antioxidant enzymes and their role in preventing cell damage. Acta Sci. Nutr. Health 2020, 4, 01–07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jomova, K.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Several lines of antioxidant defense against oxidative stress: antioxidant enzymes, nanomaterials with multiple enzyme-mimicking activities, and low-molecular-weight antioxidants. Archives of Toxicology 2024, 98, 1323–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skoryk, O.; Horila, M. Oxidative stress and disruption of the antioxidant defense system as triggers of diseases. Regulatory Mechanisms in Biosystems 2023, 14, 665–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, N.N.; Vetoshkina, D.V.; Marenkova, T.V.; Borisova-Mubarakshina, M.M. Antioxidants of Non-Enzymatic Nature: Their function in higher plant cells and the ways of boosting their Biosynthesis. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umber, J.; Qasim, M.; Ashraf, S.; Ashfaq, U.A.; Iram, A.; Bhatti, R.; Tariq, M.; Masoud, M.S. Antioxidants Mitigate Oxidative Stress: A General Overview. The Role of Natural Antioxidants in Brain Disorders 2023, 149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Jomova, K.; Raptova, R.; Alomar, S.Y.; Alwasel, S.H.; Nepovimova, E.; Kuca, K.; Valko, M. Reactive oxygen species, toxicity, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: Chronic diseases and aging. Archives of toxicology 2023, 97, 2499–2574. [Google Scholar]

- Alwadei, N.S. The Role of Cytochrome P450 2E1 in Hepatic Ischemia Reperfusion Injury and Reactive Oxygen Species Formation. Chapman University, 2023.

- Santos, D.F.; Simão, S.; Nóbrega, C.; Bragança, J.; Castelo-Branco, P.; Araújo, I.M.; Consortium, A.S. Oxidative stress and aging: synergies for age related diseases. FEBS letters 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouyahya, A.; Bakrim, S.; Aboulaghras, S.; El Kadri, K.; Aanniz, T.; Khalid, A.; Abdalla, A.N.; Abdallah, A.A.; Ardianto, C.; Ming, L.C. Bioactive compounds from nature: Antioxidants targeting cellular transformation in response to epigenetic perturbations induced by oxidative stress. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 174, 116432. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Li, Q.; Shi, H.; Li, F.; Duan, Y.; Guo, Q. New insights into the role of mitochondrial dynamics in oxidative stress-induced diseases. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 178, 117084. [Google Scholar]

- Berthiaume, J.M.; Kurdys, J.G.; Muntean, D.M.; Rosca, M.G. Mitochondrial NAD+/NADH redox state and diabetic cardiomyopathy. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2019, 30, 375–398. [Google Scholar]

- Juan, C.A.; Pérez de la Lastra, J.M.; Plou, F.J.; Pérez-Lebeña, E. The chemistry of reactive oxygen species (ROS) revisited: outlining their role in biological macromolecules (DNA, lipids and proteins) and induced pathologies. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Möller, M.N.; Denicola, A. Diffusion of peroxynitrite, its precursors, and derived reactive species, and the effect of cell membranes. Redox Biochemistry and Chemistry 2024, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, B.; Dong, G.; Pang, T.; Sun, X.; Liu, X.; Nie, Y.; Chang, X. Emerging insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutic strategies for vascular endothelial injury-associated diseases: focus on mitochondrial dysfunction. Angiogenesis 2024, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Liu, R.; Li, R.; Peng, Y.; Zhu, P.; Zhou, H. Molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial quality control in ischemic cardiomyopathy. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2023, 19, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Ghosh, S.; Mandal, A.; Ghosh, N.; Sil, P.C. ROS-associated immune response and metabolism: a mechanistic approach with implication of various diseases. Archives of Toxicology 2020, 94, 2293–2317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, J.A.; Silva, J.E.; Di Genaro, M.S.; Davicino, R.C. The multiple faces of nitric oxide in chronic granulomatous disease: A comprehensive update. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianazza, E.; Brioschi, M.; Martinez Fernandez, A.; Casalnuovo, F.; Altomare, A.; Aldini, G.; Banfi, C. Lipid peroxidation in atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2021, 34, 49–98. [Google Scholar]

- Leal, M.A.; Aires, R.; Pandolfi, T.; Marques, V.B.; Campagnaro, B.P.; Pereira, T.M.; Meyrelles, S.S.; Campos-Toimil, M.; Vasquez, E.C. Sildenafil reduces aortic endothelial dysfunction and structural damage in spontaneously hypertensive rats: Role of NO, NADPH and COX-1 pathways. Vascular pharmacology 2020, 124, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, T.; Rodriguez, S. Mitochondrial DNA: Inherent Complexities Relevant to Genetic Analyses. Genes 2024, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, M.; Patergnani, S.; Di Mambro, T.; Palumbo, L.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Giorgi, C.; Pinton, P. Calcium homeostasis in the control of mitophagy. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling 2023, 38, 581–598. [Google Scholar]

- Grel, H.; Woznica, D.; Ratajczak, K.; Kalwarczyk, E.; Anchimowicz, J.; Switlik, W.; Olejnik, P.; Zielonka, P.; Stobiecka, M.; Jakiela, S. Mitochondrial dynamics in neurodegenerative diseases: unraveling the role of fusion and fission processes. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 13033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistiakov, D.A.; Shkurat, T.P.; Melnichenko, A.A.; Grechko, A.V.; Orekhov, A.N. The role of mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiovascular disease: a brief review. Annals of medicine 2018, 50, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, G.; Fasciolo, G.; Venditti, P. Mitochondrial management of reactive oxygen species. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, F.R.; Gantner, B.N.; Sakiyama, M.J.; Kayzuka, C.; Shukla, S.; Lacchini, R.; Cunniff, B.; Bonini, M.G. ROS production by mitochondria: function or dysfunction? Oncogene 2024, 43, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, C.N.; Koren, S.A.; Wojtovich, A.P. Mitochondrial complex I ROS production and redox signaling in hypoxia. Redox biology 2023, 67, 102926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiq, I.Z. Free radicals and oxidative stress: Signaling mechanisms, redox basis for human diseases, and cell cycle regulation. Current Molecular Medicine 2023, 23, 13–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skulachev, V.P.; Vyssokikh, M.Y.; Chernyak, B.V.; Mulkidjanian, A.Y.; Skulachev, M.V.; Shilovsky, G.A.; Lyamzaev, K.G.; Borisov, V.B.; Severin, F.F.; Sadovnichii, V.A. Six functions of respiration: Isn’t it time to take control over ROS production in mitochondria, and aging along with it? International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2023, 24, 12540. [Google Scholar]

- Ježek, P.; Dlasková, A.; Engstová, H.; Špačková, J.; Tauber, J.; Průchová, P.; Kloppel, E.; Mozheitova, O.; Jabůrek, M. Mitochondrial Physiology of Cellular Redox Regulations. Physiological Research 2024, 73, S217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Gómez, B.; Ortega-Sáenz, P.; Gao, L.; González-Rodríguez, P.; García-Flores, P.; Chandel, N.; López-Barneo, J. Transgenic NADH dehydrogenase restores oxygen regulation of breathing in mitochondrial complex I-deficient mice. Nature communications 2023, 14, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.F. Antioxidant systems in poultry biology: superoxide dismutase. Journal of Animal Research and Nutrition 2016, 1, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, J.N.; Saraf, A.; Ghazal, N.; Pham, T.T.; Kwong, J.Q. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Experimental & molecular medicine 2019, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Branicky, R.; Noë, A.; Hekimi, S. Superoxide dismutases: Dual roles in controlling ROS damage and regulating ROS signaling. Journal of Cell Biology 2018, 217, 1915–1928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eleutherio, E.C.A.; Magalhães, R.S.S.; de Araújo Brasil, A.; Neto, J.R.M.; de Holanda Paranhos, L. SOD1, more than just an antioxidant. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2021, 697, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, Y.D.; Kim, H.J.; Lee, Z.H.; Kim, H.H. SOD2 and Sirt3 control osteoclastogenesis by regulating mitochondrial ROS. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 2017, 32, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mailloux, R.J. An update on mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaludercic, N.; Di Lisa, F. Mitochondrial ROS formation in the pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020, 7, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobhon, P.; Savedvanich, G.; Weerakiet, S. Oxidative stress and inflammation: the root causes of aging. Exploration of Medicine 2023, 4, 127–156. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.-l.; Lian, L.; Chen, X.-n.; Cai, W.-h.; Fan, X.-b.; Fan, Y.-j.; Li, T.-t.; Xie, Y.-y.; Zhang, J.-p. The role of mitochondria in myocardial damage caused by energy metabolism disorders: From mechanisms to therapeutics. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addo, K.M.; Khan, H. Factors affecting healthy aging and its interconnected pathways. Turkish Journal of Healthy Aging Medicine 2024, 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, P.; Fessler, M.B. Mechanisms and Effects of Activation of Innate Immunity by Mitochondrial Nucleic Acids. International Immunology 2024, dxae052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pena, E.; Brito, J.; El Alam, S.; Siques, P. Oxidative stress, kinase activity and inflammatory implications in right ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure under hypobaric hypoxia. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciutac, A.M.; Dawson, D. The role of inflammation in stress cardiomyopathy. Trends in cardiovascular medicine 2021, 31, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskalik, A.; Niderla-Bielińska, J.; Ratajska, A. Multiple roles of cardiac macrophages in heart homeostasis and failure. Heart Failure Reviews 2022, 27, 1413–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S.P.; Zhang, J.; Ye, L. Cardiomyocyte proliferation from fetal-to adult-and from normal-to hypertrophy and failing hearts. Biology 2022, 11, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacinella, G.; Ciaccio, A.M.; Tuttolomondo, A. Endothelial dysfunction and chronic inflammation: the cornerstones of vascular alterations in age-related diseases. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 15722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scioli, M.G.; Storti, G.; D’Amico, F.; Rodríguez Guzmán, R.; Centofanti, F.; Doldo, E.; Céspedes Miranda, E.M.; Orlandi, A. Oxidative stress and new pathogenetic mechanisms in endothelial dysfunction: potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2020, 9, 1995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-Y.; Lu, C.-H.; Cheng, C.-F.; Li, K.-J.; Kuo, Y.-M.; Wu, C.-H.; Liu, C.-H.; Hsieh, S.-C.; Tsai, C.-Y.; Yu, C.-L. Advanced Glycation End-Products Acting as Immunomodulators for Chronic Inflammation, Inflammaging and Carcinogenesis in Patients with Diabetes and Immune-Related Diseases. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Candore, G.; Caruso, C.; Jirillo, E.; Magrone, T.; Vasto, S. Low grade inflammation as a common pathogenetic denominator in age-related diseases: novel drug targets for anti-ageing strategies and successful ageing achievement. Current Pharmaceutical Design 2010, 16, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; Reeves, G.; Billman, G.E.; Sturmberg, J.P. Inflammation–nature’s way to efficiently respond to all types of challenges: implications for understanding and managing “the epidemic” of chronic diseases. Frontiers in medicine 2018, 5, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunta, S.; Wei, Y.; Xu, K.; Xia, S. Cold-inflammaging: When a state of homeostatic-imbalance associated with aging precedes the low-grade pro-inflammatory-state (inflammaging): Meaning, evolution, inflammaging phenotypes. Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology and Physiology 2022, 49, 925–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oishi, Y.; Manabe, I. Macrophages in age-related chronic inflammatory diseases. NPJ aging and mechanisms of disease 2016, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijaz, N.; Jamil, Y.; Brown IV, C.H.; Krishnaswami, A.; Orkaby, A.; Stimmel, M.B.; Gerstenblith, G.; Nanna, M.G.; Damluji, A.A. Role of Cognitive Frailty in Older Adults With Cardiovascular Disease. Journal of the American Heart Association 2024, 13, e033594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baechle, J.J.; Chen, N.; Makhijani, P.; Winer, S.; Furman, D.; Winer, D.A. Chronic inflammation and the hallmarks of aging. Molecular Metabolism 2023, 74, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahuja, S.K.; Manoharan, M.S.; Lee, G.C.; McKinnon, L.R.; Meunier, J.A.; Steri, M.; Harper, N.; Fiorillo, E.; Smith, A.M.; Restrepo, M.I. Immune resilience despite inflammatory stress promotes longevity and favorable health outcomes including resistance to infection. Nature communications 2023, 14, 3286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhol, N.K.; Bhanjadeo, M.M.; Singh, A.K.; Dash, U.C.; Ojha, R.R.; Majhi, S.; Duttaroy, A.K.; Jena, A.B. The interplay between cytokines, inflammation, and antioxidants: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potentials of various antioxidants and anti-cytokine compounds. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 178, 117177. [Google Scholar]

- Gusev, E.; Sarapultsev, A. Exploring the Pathophysiology of Long COVID: The Central Role of Low-Grade Inflammation and Multisystem Involvement. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25, 6389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, S.W.; Alibhai, F.J.; Weisel, R.D.; Li, R.-K. Considering cause and effect of immune cell aging on cardiac repair after myocardial infarction. Cells 2020, 9, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conte, M.; Petraglia, L.; Poggio, P.; Valerio, V.; Cabaro, S.; Campana, P.; Comentale, G.; Attena, E.; Russo, V.; Pilato, E. Inflammation and cardiovascular diseases in the elderly: the role of epicardial adipose tissue. Frontiers in Medicine 2022, 9, 844266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endres, M.; Moro, M.A.; Nolte, C.H.; Dames, C.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Meisel, A. Immune pathways in etiology, acute phase, and chronic sequelae of ischemic stroke. Circulation research 2022, 130, 1167–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, K.; Mavilavalappil, S.P. Cardiovascular Therapeutics from Natural Sources. In Drugs from Nature: Targets, Assay Systems and Leads; Springer: 2024; pp. 475-504.

- Najmi, A.; Javed, S.A.; Al Bratty, M.; Alhazmi, H.A. Modern approaches in the discovery and development of plant-based natural products and their analogues as potential therapeutic agents. Molecules 2022, 27, 349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaachouay, N.; Zidane, L. Plant-derived natural products: a source for drug discovery and development. Drugs and Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 184–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- YADAV, R.; PANDITA, A.; PANDITA, D.; MURTHY, K.S. Taxus brevifolia (Nutt.) Pilger. Potent Anticancer Medicinal Plants: Secondary Metabolite Profiling, Active Ingredients, and Pharmacological Outcomes 2023, 10.

- Qu, Y.; Safonova, O.; De Luca, V. Completion of the canonical pathway for assembly of anticancer drugs vincristine/vinblastine in Catharanthus roseus. The Plant Journal 2019, 97, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Lin, X.; Ruan, Q.; Wang, J.; Yang, Y.; Sheng, M.; Zhou, W.; Kai, G.; Hao, X. Research progress on the biosynthesis and metabolic engineering of the anti-cancer drug camptothecin in Camptotheca acuminate. Industrial Crops and Products 2022, 186, 115270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Imran, M.; Khan, I.A.; ur-Rehman, M.; Gilani, S.A.; Mehmood, Z.; Mubarak, M.S. Anticancer potential of quercetin: A comprehensive review. Phytotherapy research 2018, 32, 2109–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, R.; Nakashima, R.; Yano, M.; Iwahara, N.; Asakura, S.; Nojima, I.; Saga, Y.; Kunimoto, R.; Horio, Y.; Kuno, A. Resveratrol, a SIRT1 activator, attenuates aging-associated alterations in skeletal muscle and heart in mice. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2023, 152, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Mondo, A.; Smerilli, A.; Ambrosino, L.; Albini, A.; Noonan, D.M.; Sansone, C.; Brunet, C. Insights into phenolic compounds from microalgae: Structural variety and complex beneficial activities from health to nutraceutics. Critical Reviews in Biotechnology 2021, 41, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, S.; Nagarajan, R.; Kumar, J.; Salemme, A.; Togna, A.R.; Saso, L.; Bruno, F. Antioxidant activity of synthetic polymers of phenolic compounds. Polymers 2020, 12, 1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, M.; Dordevic, A.L.; Cox, K.; Scholey, A.; Ryan, L.; Bonham, M.P. Twelve weeks’ treatment with a polyphenol-rich seaweed extract increased HDL cholesterol with no change in other biomarkers of chronic disease risk in overweight adults: A placebo-controlled randomized trial. The Journal of Nutritional Biochemistry 2021, 96, 108777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, R.; Howlader, S.; Mamun-Or-Rashid, A.; Rafiquzzaman, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Albadrani, G.M.; Sayed, A.A.; Peluso, I.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Uddin, M.S. Antioxidant and Signal-Modulating Effects of Brown Seaweed-Derived Compounds against Oxidative Stress-Associated Pathology. Oxidative Medicine and cellular longevity 2021, 2021, 9974890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbia, D.; De Martin, S. Brown seaweeds for the management of metabolic syndrome and associated diseases. Molecules 2020, 25, 4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, L.; Cotas, J. Therapeutic potential of polyphenols and other micronutrients of marine origin. Marine drugs 2023, 21, 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W. Medicinal plants, economical and natural agents with antioxidant activity. Current Nutrition & Food Science 2023, 19, 763–784. [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal, I.; Wilairatana, P.; Saqib, F.; Nasir, B.; Wahid, M.; Latif, M.F.; Iqbal, A.; Naz, R.; Mubarak, M.S. Plant polyphenols and their potential benefits on cardiovascular health: A review. Molecules 2023, 28, 6403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrizzo, A.; Forte, M.; Damato, A.; Trimarco, V.; Salzano, F.; Bartolo, M.; Maciag, A.; Puca, A.A.; Vecchione, C. Antioxidant effects of resveratrol in cardiovascular, cerebral and metabolic diseases. Food and chemical toxicology 2013, 61, 215–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, S.; Moghadam, M.D.; Nasiriasl, M.; Akhzari, M.; Barazesh, M. Insights into the Therapeutic and Pharmacological Properties of Resveratrol as a Nutraceutical Antioxidant Polyphenol in Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Current Reviews in Clinical and Experimental Pharmacology Formerly Current Clinical Pharmacology 2024, 19, 327–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senoner, T.; Dichtl, W. Oxidative stress in cardiovascular diseases: still a therapeutic target? Nutrients 2019, 11, 2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandona, P.; Dhindsa, S.; Ghanim, H.; Chaudhuri, A. Angiotensin II and inflammation: the effect of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition and angiotensin II receptor blockade. Journal of human hypertension 2007, 21, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crismaru, I.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Bratu, O.G.; Gaman, M.-A.; Stanescu, A.M.A.; Bacalbasa, N.; Diaconu, C.C. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering treatment: the current approach. Lipids in health and disease 2020, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, M.R.; Izadi, A.; Kaviani, M. Antioxidants and exercise performance: with a focus on vitamin E and C supplementation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 8452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscolo, A.; Mariateresa, O.; Giulio, T.; Mariateresa, R. Oxidative stress: the role of antioxidant phytochemicals in the prevention and treatment of diseases. International journal of molecular sciences 2024, 25, 3264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: An updated overview. Archives of toxicology 2020, 94, 651–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, A.; Tiwari, R.; Tiwari, G.; Ramachandran, V. Resveratrol: A vital therapeutic agent with multiple health benefits. Drug Research 2022, 72, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, X.; Nie, Y.; Zhan, F.; Zhu, B. Oxidative stress and ROS-mediated cellular events in RSV infection: potential protective roles of antioxidants. Virology Journal 2023, 20, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, L.; Xiong, Y.; Wang, F.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ke, J. Resveratrol inhibits restenosis through suppressing proliferation, migration and trans-differentiation of vascular adventitia fibroblasts via activating SIRT1. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2024, 31, 242–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires, V.; Delmas, D. Common pathways in health benefit properties of RSV in cardiovascular diseases, cancers and degenerative pathologies. Current pharmaceutical biotechnology 2015, 16, 219–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.; Matta, M.J.; Sunderesan, N.; Gupta, M.P.; Periasamy, M.; Gupta, M. Resveratrol, an activator of SIRT1, upregulates sarcoplasmic calcium ATPase and improves cardiac function in diabetic cardiomyopathy. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2010, 298, H833–H843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolwicz Jr, S.C.; Tian, R. Glucose metabolism and cardiac hypertrophy. Cardiovascular research 2011, 90, 194–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, C.A.; Heiss, E.H.; Dirsch, V.M. Effect of resveratrol on endothelial cell function: Molecular mechanisms. Biofactors 2010, 36, 342–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Feng, Z.; Lu, B.; Fang, X.; Huang, D.; Wang, B. Resveratrol alleviates high glucose-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis in rat cardiac microvascular endothelial cell through AMPK/Sirt1 activation. Biochemistry and Biophysics Reports 2023, 34, 101444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungurianu, A.; Zanfirescu, A.; Margină, D. Sirtuins, resveratrol and the intertwining cellular pathways connecting them. Ageing Research Reviews 2023, 88, 101936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilkun, O.; Boudina, S. Cardiac dysfunction and oxidative stress in the metabolic syndrome: an update on antioxidant therapies. Current pharmaceutical design 2013, 19, 4806–4817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.-X.; Li, C.-X.; Kakar, M.U.; Khan, M.S.; Wu, P.-F.; Amir, R.M.; Dai, D.-F.; Naveed, M.; Li, Q.-Y.; Saeed, M. Resveratrol (RV): A pharmacological review and call for further research. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2021, 143, 112164. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, D. miR-217 and miR-543 downregulation mitigates inflammatory response and myocardial injury in children with viral myocarditis by regulating the SIRT1/AMPK/NF-κB signaling pathway. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2020, 45, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayakanti, S.R. Role of FoxO3 transcription factor in right ventricular remodeling and failure. 2022.

- Ho, J.-H.; Baskaran, R.; Wang, M.-F.; Yang, H.-S.; Lo, Y.-H.; Mohammedsaleh, Z.M.; Lin, W.-T. Bioactive peptides and exercise modulate the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α/FOXO3 pathway as a therapeutic approach for hypertensive rats. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Ma, E.; Ge, Y.; Yuan, M.; Guo, X.; Peng, J.; Zhu, W.; Ren, D.-n.; Wo, D. Resveratrol protects against myocardial ischemic injury in obese mice via activating SIRT3/FOXO3a signaling pathway and restoring redox homeostasis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2024, 174, 116476. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamoto, K.; Miura, Y.; Karnan, S.; Ota, A.; Konishi, H.; Hosokawa, Y.; Sato, K. Inhibition of NADPH oxidase 2 induces apoptosis in osteosarcoma: The role of reactive oxygen species in cell proliferation. Oncology Letters 2018, 15, 7955–7962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.-P.; Odewale, I.; Alcendor, R.R.; Sadoshima, J. Sirt1 protects the heart from aging and stress. 2008.

- Tseng, A.H.; Shieh, S.-S.; Wang, D.L. SIRT3 deacetylates FOXO3 to protect mitochondria against oxidative damage. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2013, 63, 222–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Yu, B.; Cong, X.; Zhang, W.-G.; Li, L.; Liu, L.-M.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.-L.; Gu, P.-L. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator-1α inhibits vascular calcification through sirtuin 3-mediated reduction of mitochondrial oxidative stress. Antioxidants & redox signaling 2019, 31, 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Kasai, S.; Shimizu, S.; Tatara, Y.; Mimura, J.; Itoh, K. Regulation of Nrf2 by mitochondrial reactive oxygen species in physiology and pathology. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, Y.; Jamadade, P.; Maharana, K.C.; Singh, S. Role of mitochondrial homeostasis in D-galactose-induced cardiovascular ageing from bench to bedside. Mitochondrion 2024, 101923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.A.; Franco, F.N.; Caldeira, C.A.; de Araújo, G.R.; Vieira, A.; Chaves, M.M. Resveratrol has its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory protective mechanisms decreased in aging. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics 2023, 107, 104895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.N.; Lu, J.M.; Jin, G.N.; Shen, X.Y.; Wang, J.H.; Ma, J.W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.M.; Quan, Y.Z.; Gao, H.Y. A novel mechanism of resveratrol alleviates Toxoplasma gondii infection-induced pulmonary inflammation via inhibiting inflammasome activation. Phytomedicine 2024, 155765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akgun-Unal, N.; Ozyildirim, S.; Unal, O.; Gulbahce-Mutlu, E.; Mogulkoc, R.; Baltaci, A.K. The effects of resveratrol and melatonin on biochemical and molecular parameters in diabetic old female rat hearts. Experimental Gerontology 2023, 172, 112043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sin, T.K.; Tam, B.T.; Yu, A.P.; Yip, S.P.; Yung, B.Y.; Chan, L.W.; Wong, C.S.; Rudd, J.A.; Siu, P.M. Acute treatment of resveratrol alleviates doxorubicin-induced myotoxicity in aged skeletal muscle through SIRT1-dependent mechanisms. Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biomedical Sciences and Medical Sciences 2016, 71, 730–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Ren, J.; Liu, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, H.; Zhou, T.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Tang, L.; Chen, H. Resveratrol inhibits autophagy against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury through the DJ-1/MEKK1/JNK pathway. European Journal of Pharmacology 2023, 951, 175748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Qian, S.; Tang, B.; Kang, P.; Zhang, H.; Shi, C. Resveratrol inhibits ferroptosis and decelerates heart failure progression via Sirt1/p53 pathway activation. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2023, 27, 3075–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, M.M.; Das, S.K.; Levasseur, J.; Byrne, N.J.; Fung, D.; Kim, T.T.; Masson, G.; Boisvenue, J.; Soltys, C.-L.; Oudit, G.Y. Resveratrol treatment of mice with pressure-overload–induced heart failure improves diastolic function and cardiac energy metabolism. Circulation: Heart Failure 2015, 8, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robich, M.P.; Osipov, R.M.; Nezafat, R.; Feng, J.; Clements, R.T.; Bianchi, C.; Boodhwani, M.; Coady, M.A.; Laham, R.J.; Sellke, F.W. Resveratrol improves myocardial perfusion in a swine model of hypercholesterolemia and chronic myocardial ischemia. Circulation 2010, 122, S142–S149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Cheng, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Wu, J.; Xu, B.; Chen, A.; He, F. Resveratrol pretreatment alleviates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury by inhibiting STIM1-mediated intracellular calcium accumulation. Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry 2019, 75, 607–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Qin, C.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, R.; Hu, J.; Zou, Q.; Niu, X. Resveratrol attenuate myocardial injury by inhibiting ferroptosis via inducing KAT5/GPX4 in myocardial infarction. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022, 13, 906073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuru, R.; Cai, Y.; Kandula, V.; Yan, D.; Wang, C.; Zheng, H.; Li, Y.; Irwin, M.G.; Singh, S.; Xia, Z. AMPK contributes to cardioprotective effects of pterostilbene against myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in diabetic rats by suppressing cardiac oxidative stress and apoptosis. Cellular Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, 46, 1381–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, R.A.; Tabassum, N.; Singh, M.P.; Gigli, G.; Ragusa, A.; Leporatti, S. Recent overview of resveratrol’s beneficial effects and its nano-delivery systems. Molecules 2022, 27, 5154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, S.; Chen, H.; Chen, M. Role of the Notch1 signaling pathway in ischemic heart disease. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2023, 51, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Li, N.; Wang, S.; Liu, H.; Zeng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Bu, P. Activation of SIRT3 by resveratrol ameliorates cardiac fibrosis and improves cardiac function via the TGF-β/Smad3 pathway. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2015, 308, H424–H434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Zeng, Y.; Yang, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Huang, S.; Zhong, Y.; Chen, M. Resveratrol ameliorates myocardial fibrosis by regulating Sirt1/Smad3 deacetylation pathway in rat model with dilated cardiomyopathy. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 2022, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbanzadeh, V.; Pourheydar, B.; Dariushnejad, H.; Ghalibafsabbaghi, A.; Chodari, L. Curcumin improves angiogenesis in the heart of aged rats: Involvement of TSP1/NF-κB/VEGF-A signaling. Microvascular Research 2022, 139, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox, F.F.; Misiou, A.; Vierkant, A.; Ale-Agha, N.; Grandoch, M.; Haendeler, J.; Altschmied, J. Protective effects of curcumin in cardiovascular diseases—Impact on oxidative stress and mitochondria. Cells 2022, 11, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aziz, S.G.-G.; Pourheydar, B.; Chodari, L.; Hamidifar, F. Effect of exercise and curcumin on cardiomyocyte molecular mediators associated with oxidative stress and autophagy in aged male rats. Microvascular Research 2022, 143, 104380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, M.; Nishida, K. Oxidative stress and left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction. Cardiovascular research 2009, 81, 457–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rysz, J.; Franczyk, B.; Rysz-Górzyńska, M.; Gluba-Brzózka, A. Ageing, age-related cardiovascular risk and the beneficial role of natural components intake. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 23, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, R. Curcumin Alleviates D-Galactose-Induced Cardiomyocyte Senescence by Promoting Autophagy via the SIRT1/AMPK/mTOR Pathway. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2022, 2022, 2990843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhou, X.; Lai, S.; Liu, J.; Qi, J. Curcumin activates Nrf2/HO-1 signaling to relieve diabetic cardiomyopathy injury by reducing ROS in vitro and in vivo. The FASEB Journal 2022, 36, e22505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Liao, H.; Hao, S.; Liu, R.; Huang, H.; Duan, C. Curcumin simultaneously improves mitochondrial dynamics and myocardial cell bioenergy after sepsis via the SIRT1-DRP1/PGC-1α pathway. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naaz, A.; Zhang, Y.; Faidzinn, N.A.; Yogasundaram, S.; Dorajoo, R.; Alfatah, M. Curcumin Inhibits TORC1 and Prolongs the Lifespan of Cells with Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Cells 2024, 13, 1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleenor, B.S.; Sindler, A.L.; Marvi, N.K.; Howell, K.L.; Zigler, M.L.; Yoshizawa, M.; Seals, D.R. Curcumin ameliorates arterial dysfunction and oxidative stress with aging. Experimental gerontology 2013, 48, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, X.-F.; Wen, R.-Q.; Liu, K.; Zhao, X.-K.; Pan, C.-L.; Gao, X.; Wu, X.; Zhi, X.-D.; Ren, C.-Z.; Chen, Q.-L. Role and molecular mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine in preventing cardiotoxicity associated with chemoradiotherapy. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9, 1047700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.; Yang, Z.; Fang, H.; Xiang, J.; Xu, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, Q.; Liu, J. Aging attenuates cardiac contractility and affects therapeutic consequences for myocardial infarction. Aging and disease 2020, 11, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Martinez, E.J.; Flores-Hernández, F.Y.; Salazar-Montes, A.M.; Nario-Chaidez, H.F.; Hernández-Ortega, L.D. Quercetin, a flavonoid with great pharmacological capacity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizmarova, B.; Hubkova, B.; Birkova, A. Quercetin as an effective antioxidant against superoxide radical. Functional Food Science-Online ISSN: 2767-3146 2023, 3, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulasova, E.; Perez, J.; Hill, B.G.; Bradley, W.E.; Garber, D.W.; Landar, A.; Barnes, S.; Prasain, J.; Parks, D.A.; Dell’Italia, L.J. Quercetin prevents left ventricular hypertrophy in the Apo E knockout mouse. Redox Biology 2013, 1, 381–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, C.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, S.; Yu, H.; Liu, L.; Yao, P. Myocardial mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in intense exercise: regulatory effects of quercetin. European journal of applied physiology 2014, 114, 695–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Zhao, X.; Amevor, F.K.; Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, D.; Shu, G.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, X. Therapeutic application of quercetin in aging-related diseases: SIRT1 as a potential mechanism. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 943321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadrani, G.M.; BinMowyna, M.N.; Bin-Jumah, M.N.; El–Akabawy, G.; Aldera, H.; Al-Farga, A.M. Quercetin prevents myocardial infarction adverse remodeling in rats by attenuating TGF-β1/Smad3 signaling: Different mechanisms of action. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences 2021, 28, 2772–2782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Kumari, A.; Jagdale, P.; Ayanur, A.; Pant, A.B.; Khanna, V.K. Potential of quercetin to protect cadmium induced cognitive deficits in rats by modulating NMDA-R mediated downstream signaling and PI3K/AKT—Nrf2/ARE signaling pathways in hippocampus. NeuroMolecular Medicine 2023, 25, 426–440. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Lou, H.; Lu, X.; Fan, X. Reduning injection and its effective constituent luteoloside protect against sepsis partly via inhibition of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB/MAPKs signaling pathways. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2021, 270, 113783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.-J.; Cheng, Y.; Li, W.; Dong, X.-K.; Wei, J.-l.; Yang, C.-H.; Jiang, Y.-H. Quercetin attenuates cardiac hypertrophy by inhibiting mitochondrial dysfunction through SIRT3/PARP-1 pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 739615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksymchuk, O.; Shysh, A.; Kotliarova, A. Quercetin inhibits the expression of MYC and CYP2E1 and reduces oxidative stress in the myocardium of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Acta Biochimica Polonica 2023, 70, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Rocha, E.V.; Falchetti, F.; Pernomian, L.; De Mello, M.M.B.; Parente, J.M.; Nogueira, R.C.; Gomes, B.Q.; Bertozi, G.; Sanches-Lopes, J.M.; Tanus-Santos, J.E. Quercetin decreases cardiac hypertrophic mediators and maladaptive coronary arterial remodeling in renovascular hypertensive rats without improving cardiac function. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Archives of Pharmacology 2023, 396, 939–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.-L.; Jiang, W.-J.; Zhou, Z.; Shi, T.-F.; Yu, M.; Yu, M.; Si, J.-Q.; Wang, Y.-P.; Li, L. Quercetin attenuates cisplatin-induced mitochondrial apoptosis via PI3K/Akt mediated inhibition of oxidative stress in pericytes and improves the blood labyrinth barrier permeability. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2024, 393, 110939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jubaidi, F.F.; Zainalabidin, S.; Taib, I.S.; Hamid, Z.A.; Budin, S.B. The potential role of flavonoids in ameliorating diabetic cardiomyopathy via alleviation of cardiac oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22, 5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Jia, Q.; Yan, L.; Chen, C.; Xing, S.; Shen, D. Quercetin suppresses the progression of atherosclerosis by regulating MST1-mediated autophagy in ox-LDL-induced RAW264. 7 macrophage foam cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 20, 6093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.-L.; Zhao, C.-H.; Yao, X.-L.; Zhang, H. Quercetin attenuates high fructose feeding-induced atherosclerosis by suppressing inflammation and apoptosis via ROS-regulated PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 85, 658–671. [Google Scholar]

- Shemiakova, T.; Ivanova, E.; Grechko, A.V.; Gerasimova, E.V.; Sobenin, I.A.; Orekhov, A.N. Mitochondrial dysfunction and DNA damage in the context of pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaskar, S.; Sudhakaran, P.; Helen, A. Quercetin attenuates atherosclerotic inflammation and adhesion molecule expression by modulating TLR-NF-κB signaling pathway. Cellular immunology 2016, 310, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhou, J. Mechanisms of Abnormal Lipid Metabolism in the Pathogenesis of Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eng, Q.Y.; Thanikachalam, P.V.; Ramamurthy, S. Molecular understanding of Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) in cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. Journal of ethnopharmacology 2018, 210, 296–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Shankar, S.; Srivastava, R.K. Green tea catechin, epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG): mechanisms, perspectives and clinical applications. Biochemical pharmacology 2011, 82, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, R.; Jin, H.; Jin, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, H.; Chen, W. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate confers protection against corticosterone-induced neuron injuries via restoring extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase/protein kinase B signaling pathways. Plos One 2018, 13, e0192083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokra, D.; Joskova, M.; Mokry, J. Therapeutic effects of green tea polyphenol (‒)-Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) in relation to molecular pathways controlling inflammation, oxidative stress, and apoptosis. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 24, 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Chiou, Y.-S.; Pan, M.-H.; Shahidi, F. Anti-inflammatory activity of lipophilic epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) derivatives in LPS-stimulated murine macrophages. Food chemistry 2012, 134, 742–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-R.; Seong, K.-J.; Kim, W.-J.; Jung, J.-Y. Epigallocatechin gallate protects against hypoxia-induced inflammation in microglia via NF-κB suppression and Nrf-2/HO-1 activation. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2022, 23, 4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Luo, Y.; Yin, J.; Huang, M.; Luo, F. Targeting AMPK signaling by polyphenols: A novel strategy for tackling aging. Food & Function 2023, 14, 56–73. [Google Scholar]

- Brandt, M.; Dörschmann, H.; Khraisat, S.a.; Knopp, T.; Ringen, J.; Kalinovic, S.; Garlapati, V.; Siemer, S.; Molitor, M.; Göbel, S. Telomere shortening in hypertensive heart disease depends on oxidative DNA damage and predicts impaired recovery of cardiac function in heart failure. Hypertension 2022, 79, 2173–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyama, J.-i.; Shiraki, A.; Nishikido, T.; Maeda, T.; Komoda, H.; Shimizu, T.; Makino, N.; Node, K. EGCG, a green tea catechin, attenuates the progression of heart failure induced by the heart/muscle-specific deletion of MnSOD in mice. Journal of Cardiology 2017, 69, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Quan, J.; Liu, L.; Xu, Z.; Zhu, J.; Huang, X.; Tian, J. Epigallocatechin gallate reverses cTnI-low expression-induced age-related heart diastolic dysfunction through histone acetylation modification. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2017, 21, 2481–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Xu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, J.; Wang, X.; Nan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shen, W.; Huang, X. Diastolic dysfunction and cardiac troponin I decrease in aging hearts. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2016, 603, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinzel, F.R.; Hegemann, N.; Hohendanner, F.; Primessnig, U.; Grune, J.; Blaschke, F.; de Boer, R.A.; Pieske, B.; Schiattarella, G.G.; Kuebler, W.M. Left ventricular dysfunction in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction—molecular mechanisms and impact on right ventricular function. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy 2020, 10, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myhre, P.L.; Claggett, B.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Selvin, E.; Røsjø, H.; Omland, T.; Solomon, S.D.; Skali, H.; Shah, A.M. Association between circulating troponin concentrations, left ventricular systolic and diastolic functions, and incident heart failure in older adults. JAMA cardiology 2019, 4, 997–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, J.; Jia, Z.; Liu, L.; Tian, J. The effect of long-term administration of green tea catechins on aging-related cardiac diastolic dysfunction and decline of troponin I. Genes & Diseases 2024, 101284. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Pan, J.; Liu, H.; Jiao, Z. Characterization of the synergistic antioxidant activity of epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and kaempferol. Molecules 2023, 28, 5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdavi-Roshan, M.; Salari, A.; Ghorbani, Z.; Ashouri, A. The effects of regular consumption of green or black tea beverage on blood pressure in those with elevated blood pressure or hypertension: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2020, 51, 102430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Pan, B.; Liu, L.; Xu, X.; Zhao, W.; Mou, Q.; Hwang, N.; Chung, S.W.; Liu, X.; Tian, J. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate restores mitochondrial homeostasis impairment by inhibiting HDAC1-mediated NRF1 histone deacetylation in cardiac hypertrophy. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry 2024, 479, 963–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilasrusmee, K.T.; Sitticharoon, C.; Keadkraichaiwat, I.; Maikaew, P.; Pongwattanapakin, K.; Chatree, S.; Sririwichitchai, R.; Churintaraphan, M. Epigallocatechin gallate enhances sympathetic heart rate variability and decreases blood pressure in obese subjects: a randomized control trial. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 21628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-S.; Kuo, W.-W.; Huang, C.-Y. Autologous transplantation of green tea epigallocatechin-3-gallate pretreated adipose-derived stem cells increases cardiac regenerative capability through CXC motif chemokine receptor 4 expression in the treatment of rats with diabetic cardiomyopathy. Experimental Animals 2024, 73, 246–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banzubaze, E.; Ondari, E.; Aja, P.; Shinkafi, T.; Mulindwa, J. Epigenetic Regulation by Epi-gallocatechin-3-Galatte on Antioxidant Gene Expression in Mice That Are at High Risk for Heart Disease. J Anesth Pain Med 2024, 9, 01–12. [Google Scholar]

- Corrêa, R.C.; Peralta, R.M.; Haminiuk, C.W.; Maciel, G.M.; Bracht, A.; Ferreira, I.C. New phytochemicals as potential human anti-aging compounds: Reality, promise, and challenges. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition 2018, 58, 942–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, B.; Baghaei-Yazdi, N.; Bahmaie, M.; Mahdavi Abhari, F. The role of plant-derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. BioFactors 2022, 48, 611–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, T.C. Anthocyanins in cardiovascular disease. Advances in nutrition 2011, 2, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, G.H.; Hoang, T.H.; Jung, E.S.; Jung, S.J.; Han, S.K.; Chung, M.J.; Chae, S.W.; Chae, H.J. Anthocyanins attenuate endothelial dysfunction through regulation of uncoupling of nitric oxide synthase in aged rats. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafez, A.M.; Gaafar, N.K.; Mohamed, L.; Dawood, M.M.M.; Wagih, A.A.E.-F. The beneficial effects of anthocyanin on D-galactose induced cardiac muscle aging in rats.

- Edirisinghe, I.; Banaszewski, K.; Cappozzo, J.; McCarthy, D.; Burton-Freeman, B.M. Effect of black currant anthocyanins on the activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) in vitro in human endothelial cells. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2011, 59, 8616–8624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, C.; Blesso, C.N. Antioxidant properties of anthocyanins and their mechanism of action in atherosclerosis. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2021, 172, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, N.; Farrell, M.; O’Sullivan, L.; Langan, A.; Franchin, M.; Azevedo, L.; Granato, D. Effectiveness of anthocyanin-containing foods and nutraceuticals in mitigating oxidative stress, inflammation, and cardiovascular health-related biomarkers: a systematic review of animal and human interventions. Food & Function 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, T.; Liu, M.; Fu, D.; Xue, Y.; Liao, J.; Yang, P.; Li, X. Allicin treats myocardial infarction in I/R through the promotion of the SHP2 axis to inhibit p-PERK-mediated oxidative stress. Aging (Albany NY) 2024, 16, 5207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Saber Batiha, G.; Magdy Beshbishy, A.; G. Wasef, L.; Elewa, Y.H.; A. Al-Sagan, A.; Abd El-Hack, M.E.; Taha, A.E.; M. Abd-Elhakim, Y.; Prasad Devkota, H. Chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of garlic (Allium sativum L.): A review. Nutrients 2020, 12, 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.-n.; Li, L.-d.; Li, S.-c.; Hao, X.-m.; Zhang, J.-y.; He, P.; Li, Y.-k. Allicin improves cardiac function by protecting against apoptosis in rat model of myocardial infarction. Chinese journal of integrative medicine 2017, 23, 589–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Beek, T.A.; Montoro, P. Chemical analysis and quality control of Ginkgo biloba leaves, extracts, and phytopharmaceuticals. Journal of chromatography A 2009, 1216, 2002–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-G.; Lu, X.; Gao, W.; Li, P.; Yang, H. Structure, synthesis, biosynthesis, and activity of the characteristic compounds from Ginkgo biloba L. Natural Product Reports 2022, 39, 474–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medicine, C.A.o.I.; Association, C.M.D.; Cardiology, N.C.R.C.f.C.M.; Group, C.D.W.; Group, E.D.W.; Medicine, C.C.f.E.-B.C.; Chen, K.-j. Chinese expert consensus on clinical application of oral Ginkgo biloba preparations (2020). Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine 2021, 27, 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- Kadhim, S.M.; Mohammed, M.T.; Abbood, S.M. Biochemical studies of Ginkgo biloba extract on oxidative stress-induced myocardial injuries. Drug Invention Today 2020, 14, 817–820. [Google Scholar]

- Lejri, I.; Grimm, A.; Eckert, A. Ginkgo biloba extract increases neurite outgrowth and activates the Akt/mTOR pathway. PloS one 2019, 14, e0225761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, J.-H.; Sung, J.-H.; Cho, E.-H.; Won, C.-K.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, M.-O.; Koh, P.-O. Gingko biloba Extract (EGb 761) prevents ischemic brain injury by activation of the Akt signaling pathway. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2009, 37, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.-H.; Bao, Y.-M.; Wang, X.-Y.; Zhang, Z.-X. Cardio-protection by Ginkgo biloba extract 50 in rats with acute myocardial infarction is related to Na+–Ca 2+ exchanger. The American Journal of Chinese Medicine 2013, 41, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Gao, Q.; Liang, S.; Zhu, G.; Wang, D.; Feng, Y. Cardioprotective properties of ginkgo biloba extract 80 via the activation of AKT/GSK3β/β-Catenin signaling pathway. Frontiers in molecular biosciences 2021, 8, 771208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Lu, M.; Li, J.; Zhu, Z. Ginkgolide B protects cardiomyocytes from angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy via regulation of autophagy through SIRT1-FoxO1. Cardiovascular Therapeutics 2021, 2021, 5554569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; An, Z.; Xing, H.; Tian, J.; Song, X. Ginkgo biloba extract protects against diabetic cardiomyopathy by restoring autophagy via adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of the rapamycin pathway modulation. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 1377–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiwe, J.N.; Ben-Azu, B.; Yovwin, G.D.; Igben, V.-J.O.; Oritsemuelebi, B.; Efejene, I.O.; Adebayo, O.G.; Asiwe, N.; Ojieh, A.E. Ginkgo biloba supplement modulates mTOR/ERK1/2 activities to mediate cardio-protection in cyclosporin-A-induced cardiotoxicity in Wistar rats. Clinical Traditional Medicine and Pharmacology 2024, 5, 200134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Yan, C.; Zhang, R.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; Hu, S.; Zhao, X.; Liu, R.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y. Ginkgo biloba extract (EGb761) inhibits autophagy and apoptosis in a rat model of vascular dementia via the AMPK-mTOR signalling pathway. Journal of Functional Foods 2024, 116, 106168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, G.; Abd Allah, S.; Ezzat, R. Pharmacological activities and medicinal uses of berberine: A review. Journal of Advanced Veterinary Research 2024, 14, 330–334. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Jiang, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, Y.; Han, Y.; Jiang, J. Berberine exerts protective effects on cardiac senescence by regulating the Klotho/SIRT1 signaling pathway. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2022, 151, 113097. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Lu, C. Berberine ameliorates diabetic cardiomyopathy in mice by decreasing cardiomyocyte apoptosis and oxidative stress. Cardiovascular Innovations and Applications 2023, 8, 20230064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tang, X.-q.; Shi, Y.; Li, H.-m.; Meng, Z.-y.; Chen, H.; Li, X.-h.; Chen, Y.-c.; Liu, H.; Hong, Y. Tetrahydroberberrubine retards heart aging in mice by promoting PHB2-mediated mitophagy. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2023, 44, 332–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, X.; Rong, L.; Fu, B.; Cui, S.; Gu, Z.; Hu, F.; Lu, Y.; Yan, S.; Sun, B.; Jiang, W. Astragalus polysaccharides attenuate rat aortic endothelial senescence via regulation of the SIRT-1/p53 signaling pathway. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 2024, 24, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Hedström, D.; García-Villalón, Á.L.; Amor, S.; de la Fuente-Fernández, M.; Almodóvar, P.; Prodanov, M.; Priego, T.; Martín, A.I.; Inarejos-García, A.M.; Granado, M. Olive leaf extract supplementation improves the vascular and metabolic alterations associated with aging in Wistar rats. Scientific reports 2021, 11, 8188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomaa, A.M.; Abdelhafez, A.T.; Aamer, H.A. Garlic (Allium sativum) exhibits a cardioprotective effect in experimental chronic renal failure rat model by reducing oxidative stress and controlling cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase activity and Ca 2+ levels. Cell Stress and Chaperones 2018, 23, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Huang, D.; Li, S. Lycopene alleviates oxidative stress-induced cell injury in human vascular endothelial cells by encouraging the SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension 2023, 45, 2205051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z. Beta carotene protects H9c2 cardiomyocytes from advanced glycation end product-induced endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and autophagy via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Annals of Translational Medicine 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hada, Y.; Uchida, H.A.; Otaka, N.; Onishi, Y.; Okamoto, S.; Nishiwaki, M.; Takemoto, R.; Takeuchi, H.; Wada, J. The protective effect of chlorogenic acid on vascular senescence via the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway. International journal of molecular sciences 2020, 21, 4527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ping, P.; Yang, T.; Ning, C.; Zhao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Yang, T.; Gao, Z.; Fu, S. Chlorogenic acid attenuates cardiac hypertrophy via up-regulating Sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor1 to inhibit endoplasmic reticulum stress. ESC Heart Failure 2024, 11, 1580–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cicek, B.; Hacimuftuoglu, A.; Yeni, Y.; Danisman, B.; Ozkaraca, M.; Mokhtare, B.; Kantarci, M.; Spanakis, M.; Nikitovic, D.; Lazopoulos, G. Chlorogenic acid attenuates doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and markers of apoptosis in cardiomyocytes via Nrf2/HO-1 and dityrosine signaling. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2023, 13, 649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oskuye, Z.Z.; Mehri, K.; Mokhtari, B.; Bafadam, S.; Nemati, S.; Badalzadeh, R. Cardioprotective effect of antioxidant combination therapy: A highlight on MitoQ plus alpha-lipoic acid beneficial impact on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in aged rats. Heliyon 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Hsia, C.-C.; Hu, P.-A.; Yeh, C.-H.; Chen, C.-T.; Peng, C.-L.; Wang, C.-H.; Lee, T.-S. Bromelain ameliorates atherosclerosis by activating the TFEB-mediated autophagy and antioxidant pathways. Antioxidants 2022, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, L.; Han, X.; Sun, Z.; Chu, L. 8-Gingerol ameliorates myocardial fibrosis by attenuating reactive oxygen species, apoptosis, and autophagy via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2021, 12, 711701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.-L.; Yu, X.-J.; Hu, H.-B.; Yang, Q.-W.; Liu, K.-L.; Chen, Y.-M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, D.-D.; Tian, H.; Zhu, G.-Q. Apigenin improves hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy through modulating NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS generation and cytokines in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus. Cardiovascular Toxicology 2021, 21, 721–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Q.-z.; Zhao, S.-h.; Ji, X.; Qiu, J.; Wang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Cai, Q.; Zhang, J.; Gao, H.-q. Astaxanthin attenuated pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction and myocardial fibrosis: Partially by activating SIRT1. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects 2017, 1861, 1715–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, W.-J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.-G.; Jian, Z.-H.; Xiong, X.-X. Astaxanthin suppresses LPS-induced myocardial apoptosis by regulating PTP1B/JNK pathway in vitro. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 127, 111395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, S.; Ruan, Y.; Yan, M.; Xu, K.; Yang, Y.; Shen, T.; Jin, Z. Ferulic Acid Alleviates Oxidative Stress-Induced Cardiomyocyte Injury by the Regulation of miR-499-5p/p21 Signal Cascade. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2021, 2021, 1921457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testai, L.; Piragine, E.; Piano, I.; Flori, L.; Da Pozzo, E.; Miragliotta, V.; Pirone, A.; Citi, V.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Brogi, S. The Citrus Flavonoid Naringenin Protects the Myocardium from Ageing-Dependent Dysfunction: Potential Role of SIRT1. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2020, 2020, 4650207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elseweidy, M.M.; Ali, S.I.; Shaheen, M.A.; Abdelghafour, A.M.; Hammad, S.K. Vanillin and pentoxifylline ameliorate isoproterenol-induced myocardial injury in rats via the Akt/HIF-1α/VEGF signaling pathway. Food & Function 2023, 14, 3067–3082. [Google Scholar]

- Yuvaraj, S.; Ramprasath, T.; Saravanan, B.; Vasudevan, V.; Sasikumar, S.; Selvam, G.S. Chrysin attenuates high-fat-diet-induced myocardial oxidative stress via upregulating eNOS and Nrf2 target genes in rats. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2021, 476, 2719–2727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, F.; Lei, Z.; Peng, X.; Chen, L.; Peng, L.; Liu, Y.; Rao, Z.; Yang, R.; Zeng, N. Cardioprotective effect of cinnamaldehyde pretreatment on ischemia/reperfusion injury via inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome activation and gasdermin D mediated cardiomyocyte pyroptosis. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2022, 368, 110245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosuru, R.; Kandula, V.; Rai, U.; Prakash, S.; Xia, Z.; Singh, S. Pterostilbene decreases cardiac oxidative stress and inflammation via activation of AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 pathway in fructose-fed diabetic rats. Cardiovascular drugs and therapy 2018, 32, 147–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cai, Z.; Zhan, G.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Li, S.; Luo, A. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester suppresses oxidative stress and regulates M1/M2 microglia polarization via Sirt6/Nrf2 pathway to mitigate cognitive impairment in aged mice following anesthesia and surgery. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kuo, Y.-H.; Du, C.-X.; Huang, C.-W.; Ku, H.-C. A novel caffeic acid derivative prevents angiotensin II-induced cardiac remodeling. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2023, 162, 114709. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Wang, X.; Huang, Q.; Li, S.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Z. Cardioprotection of CAPE-oNO2 against myocardial ischemia/reperfusion induced ROS generation via regulating the SIRT1/eNOS/NF-κB pathway in vivo and in vitro. Redox Biology 2018, 15, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liu, X.; Pi, W.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, L.; Xu, C.; Sun, Z.; Jiang, J. Fisetin attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy in vivo and in vitro by inhibiting ferroptosis through SIRT1/Nrf2 signaling pathway activation. Frontiers in pharmacology 2022, 12, 808480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, P.; Li, J.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Xue, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Han, X.; Jing, X.; Chu, L. Hesperetin modulates the Sirt1/Nrf2 signaling pathway in counteracting myocardial ischemia through suppression of oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 139, 111552. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, L.; Xu, H.; Yao, Z.; Zeng, X.; Kang, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, G.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, D. Jin-Xin-Kang alleviates heart failure by mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction through the Calcineurin/Dynamin-Related Protein 1 signaling pathway. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2024, 335, 118685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, M.; Zheng, T.; Shen, L.; Tan, Y.; Fan, Y.; Shuai, S.; Bai, L.; Li, X.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S. Genistein reverses isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy by regulating miR-451/TIMP2. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2019, 112, 108618. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, L.; Huang, Y.; Li, W.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, Z. Saponins of Panax japonicus ameliorates cardiac aging phenotype in aging rats by enhancing basal autophagy through AMPK/mTOR/ULK1 pathway. Experimental Gerontology 2023, 182, 112305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumerle, S.; Sarill, M.; Saponaro, M.; Colucci, M.; Contu, L.; Lazzarini, E.; Sartori, R.; Pezzini, C.; Rinaldi, A.; Scanu, A. Targeting senescence induced by age or chemotherapy with a polyphenol-rich natural extract improves longevity and healthspan in mice. Nature Aging 2024, 4, 1231–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yan, M.; He, S.; Xie, Y.; Wei, L.; Xuan, B.; Shang, Z.; Wu, M.; Zheng, H.; Chen, Y. Baicalin alleviates angiotensin II-induced cardiomyocyte apoptosis and autophagy and modulates the AMPK/mTOR pathway. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2024, 28, e18321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Dosage | Pathway | Impact | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astragalus polysaccharides | 200 mg/kg/d | SIRT-1/p53 | Improved SIRT-1 protein expression in rat aortic tissue, decreased aging marker proteins, reduced hydrogen peroxide-induced cell senescence, and restored MMP and T-AOC impairment in RAECs. | [253] |

| Olive leaves | 100 mg/kg/d | COX-2/ IL-6/ GPx/NOX-1/ & IL-10 | Significantly reduces inflammation and oxidative stress, potentially enhancing cardiometabolic health in older patients by alleviating the metabolic and vascular changes associated with aging. | [254] |

| Garlic (A. sativum) | 100 mg/kg−1/d | Na+/K+-ATPase and Ca2+ | The experimental CRF model revealed that GE administration effectively protected the heart by lowering oxidative stress, modulating cardiac Na+/K+-ATPase activity, and regulating Ca2+ levels. | [255] |

| EGCG | 100 or 200 mg/kg/d | cTnI | Combat the aging-related decrease in CDD and cTnI expression. | [219] |

| Lycopene | 0.5, 1, or 2 µm/d | SIRT1/Nrf2/HO-1 | Reduces intracellular ROS levels, the synthesis of inflammatory factors, cell adhesiveness, and the rate of apoptosis under oxidative stress conditions, therefore mitigating oxidative damage in human VECs. | [256] |

| β-carotene | 40 µM/d | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Significantly reduced AGE-induced cell death, apoptosis, ROS production, antioxidative enzyme reduction, ER stress, autophagy, and cardioprotection in H9c2 cells, thereby reducing ER stress and autophagy. | [257] |

| Chlorogenic acid | 20 or 40 mg/kg/d | Nrf2/HO-1 | Positive impact on vascular senescence. | [258] |

| Chlorogenic acid | 90 mg/kg/d | AMPK/SIRT1 | AMPK/SIRT1 pathway activation by S1pr1 regulation decreased ISO-induced ERS and cardiac hypertrophy. | [259] |

| Chlorogenic acid | 15 mg/kg i.p./h | Nrf2/HO-1 | Inhibit DT expression, activate the Nrf2/HO-1 signaling pathway, decrease oxidative stress, and decrease apoptotic markers to lessen DOX-induced cardiotoxicity in vivo. | [260] |

| Alpha-lipoic acid | 100 mg/kg/d | Upregulated Mfn1, Mfn2 & Foxo1 downregulated Drp1 and Fis1 | Preventing the aging heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, and dynamics in elderly rats. | [261] |

| Bromelain | 20 mg/kg/d | AMPK/TFEB | Facilitated anti-hyperlipidemic, antioxidant, & anti-inflammatory actions, contributing to the mitigation of atherosclerosis. | [262] |

| 8-Gingerol | 10 or 20 mg/kg/d | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | The findings imply that via inhibiting ROS production, apoptosis, and autophagy, ISO-induced MF may have cardioprotective benefits. | [263] |

| Apigenin | 20 μg/h | NADPH oxidase | Reduce inflammation in the PVN and down-regulating NADPH oxidase-dependent ROS generation in SHRs can improve hypertension and cardiac hypertrophy. | [264] |

| Astaxanthin | 75 mg/kg/d | SIRT1 | Improves cardiac function and diminishes fibrosis by decreasing the phosphorylation and deacetylation of R-SMADs. | [265] |

| Astaxanthin | 10 µg/ml/48h | PTP1B/JNK | Reduce LPS-induced mitochondrial apoptosis in H9C2 cells by regulating JNK signaling. | [266] |

| Ferulic acid | 30 mg/kg/d | miR-499-5p/p21 | Protect cardiomyocytes from oxidative stress-induced injury, suggesting potential use in treating cardiovascular diseases. | [267] |

| Naringenin | 100 mg/kg/d | SIRT1 | A nutraceutical strategy utilizing NAR may ameliorate myocardial senescence by targeting essential characteristics, potentially enhancing heart function in elderly individuals. | [268] |

| Vanillin | 150 mg kg−1/d−1 | Akt/HIF-1α/VEGF | Potential of Van and PTX in lowering MI through improving cardiac angiogenesis and controlling apoptosis, inflammation, and oxidative stress. | [269] |

| Chrysin | 100 mg/kg/d | eNOS & Nrf2 | Prevents myocardial complications from hypercholesterolemia-induced oxidative stress by activating eNOS and Nrf2 signaling. | [270] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | 45 and 90 mg/kg/d | NLRP3 | Exhibits cardioprotective characteristics by suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation and GSDMD-mediated pyroptosis in cardiomyocytes, presenting potential uses for myocardial ischemia/reperfusion damage. | [271] |

| Pterostilbene | 20 mg kg−1 day−1 | AMPK/Nrf2/HO-1 | In diabetic rats, it decreases inflammation and heart oxidative stress. | [272] |

| Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester | 10 mg/kg i.p./d | Sirt6/Nrf2 | Effectively suppresses oxidative stress and promotes protective polarization in microglia. | [273] |

| Caffeic acid derivative | 3 mg/kg/ i.p./d | TGF-β/SMAD/NOX4 | Potential to prevent the progression of Ang II-induced cardiac remodeling. | [274] |

| Caffeic acid phenethyl ester | 1 mg/kg/d | SIRT1/eNOS/NF-κB | The treatment improved MIRI by reducing oxidative stress, inflammatory response, fibrosis, and necrocytosis. | [275] |

| Fisetin | 20 mg/kg/d | SIRT1/Nrf2 | Effectively treats DOX-induced cardiomyopathy by inhibiting ferroptosis. | [276] |

| Hesperidin | 25 to 50 mg/kg/d | Sirt1/Nrf2 | Protects against ISO-induced myocardial ischemia by regulating oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis. | [277] |

| Jin-Xin-Kang | 4.38 -13.14g/kg/d | CaN/Drp1 | Plays a crucial role in cardioprotection, particularly in regulating mitochondrial function. | [278] |