Submitted:

22 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

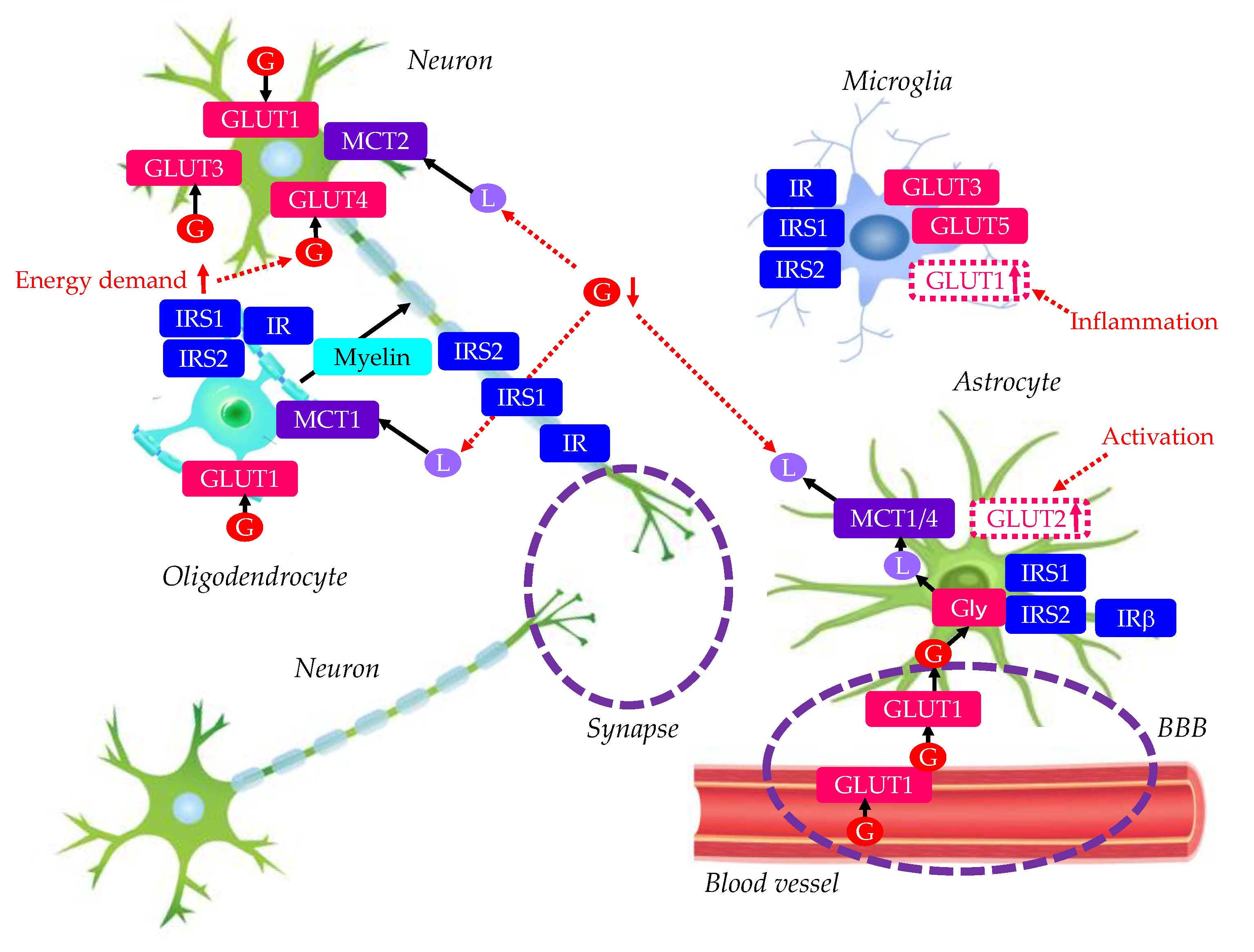

2. Glucose Metabolism and Insulin Signaling in Normal Brain

2.1. Neurons

2.2. Astrocytes

2.3. Oligodendrocytes

2.4. Microglia

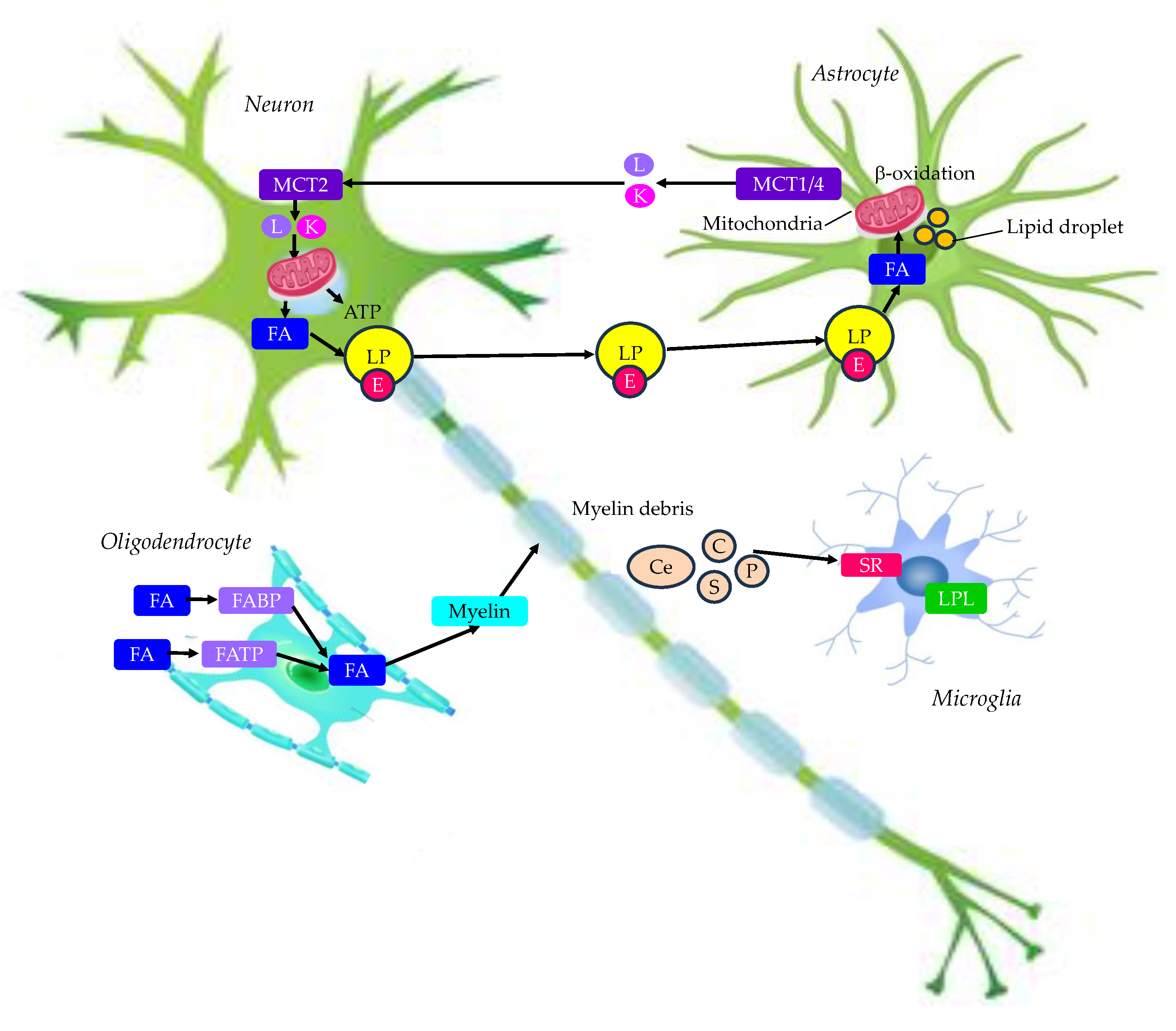

3. Lipid Metabolism in Normal Brain

3.1. Neurons and Astrocytes

3.2. Oligidendrocytes

3.3. Microglia

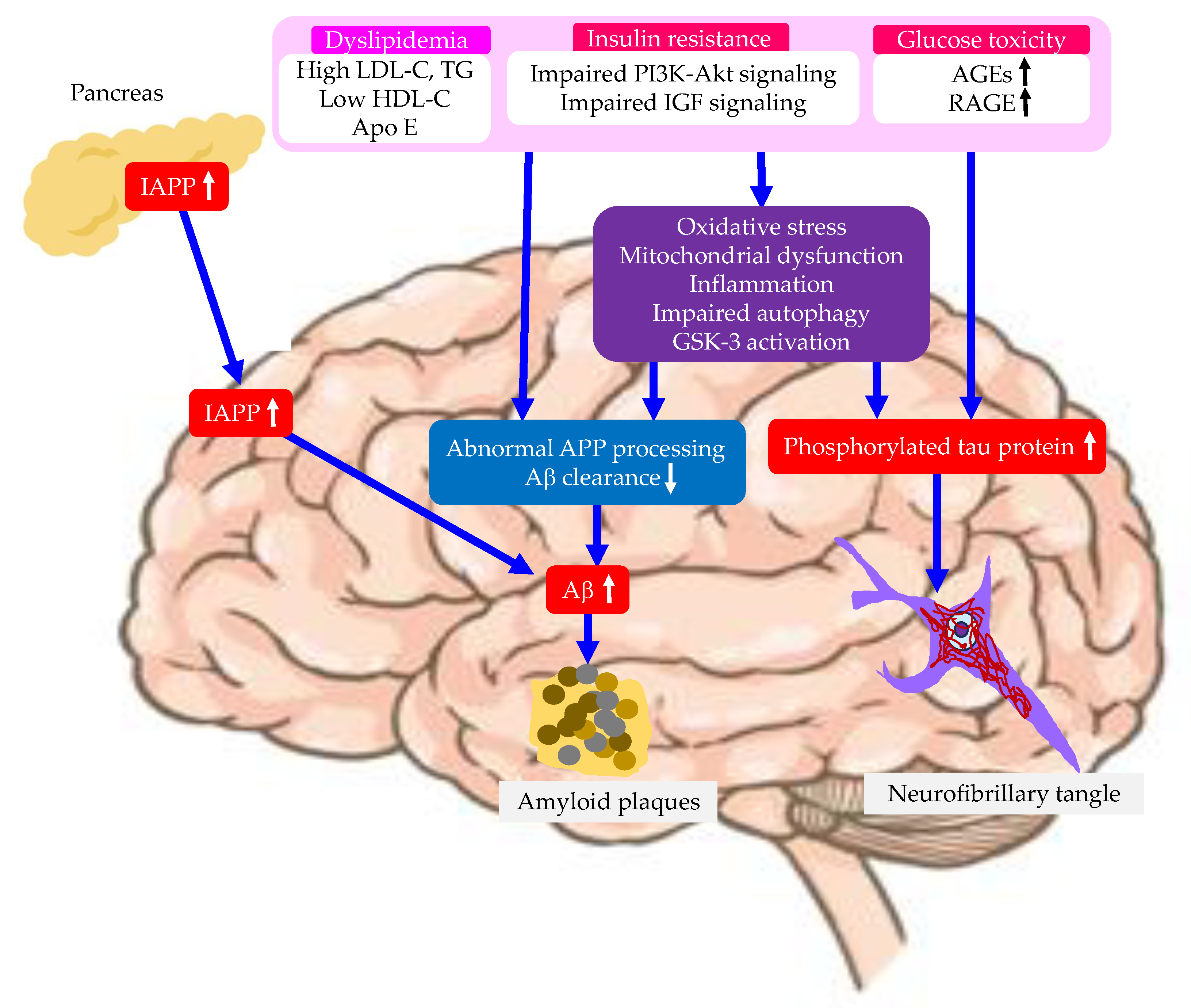

4. Risk Factors Related with Type 2 Diabetes for the Development of AD

4.1. Insulin Resistance

4.2. Dyslipidemia

4.3. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) and the Receptor for AGEs (RAGE)

4.4. Oxidative Stress

4.5. Inflammtion

4.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

4.7. Impaired Autophagy

4.8. Overactivity of GSK-3

4.9. Islet Amyloid Polypeptide (IAPP, or Amylin)

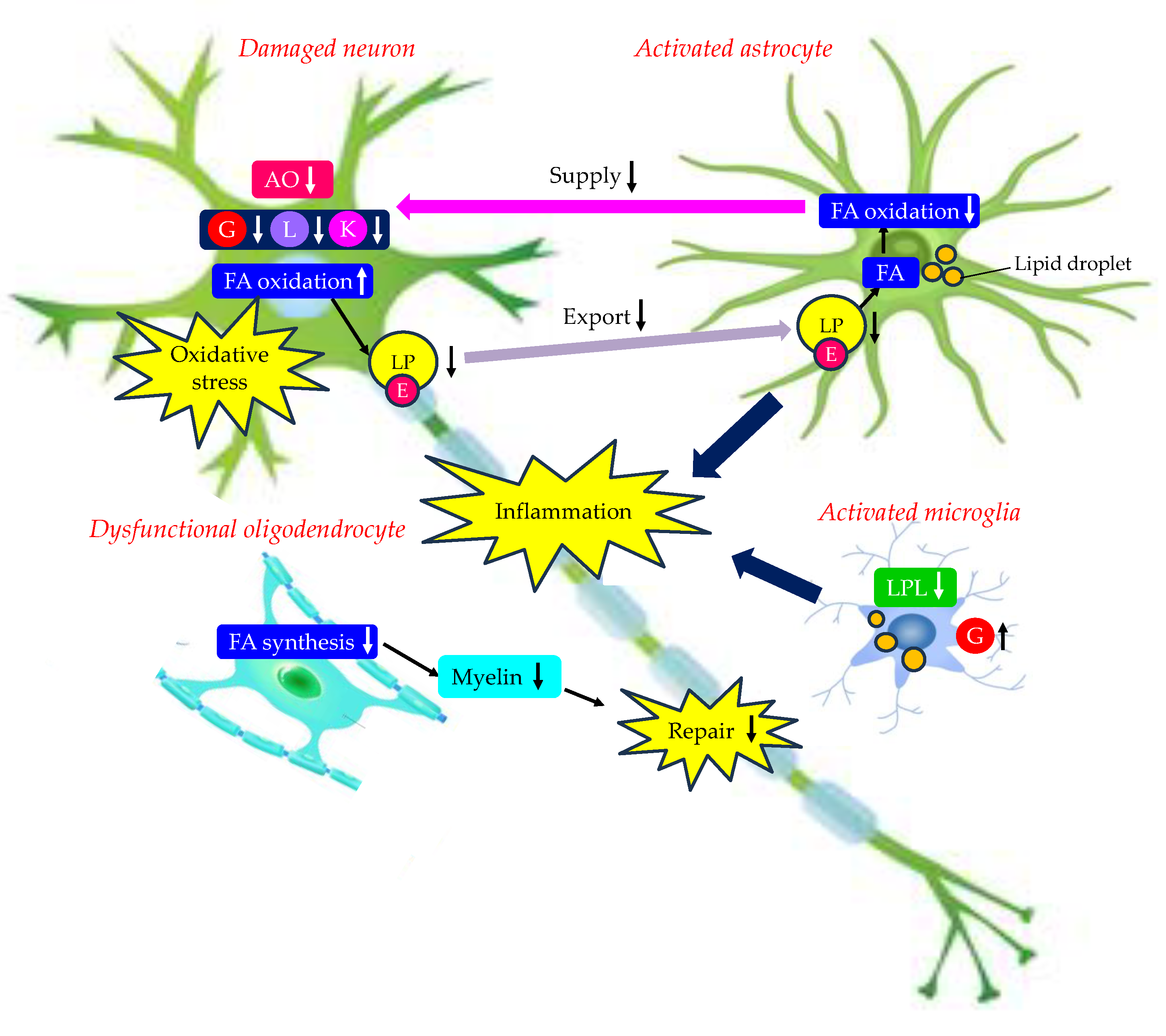

5. Changes in Energy Metabolism by Type 2 Diabetes and AD

5.1. Changes in GLUTs by Type 2 Diabetes

5.2. Changes in GLUTs by AD

5.3. Changes in MCTs by Type 2 Diabetes

5.4. Changes in MCTs by AD

5.5. Changes in Lipid Metabolism by AD

5.6. Effects of Changes in Energy Metabolim in Brain Due to Type 2 Diabetes on the Development of AD

6. Possible Therapeutic Intervention for AD Considering AD Risk Factors

6.1. Exercise

6.2. Diet

6.3. Antioxidants

6.3.1. Vitamin E

6.3.2. Vitamin C

6.3.3. Resveratrol

6.4. Statins

6.5. PPARα Agonists

6.6. n-3-PUFA

6.7. Anti-Diabetic Drugs

6.7.1. Pioglitazone

6.7.2. Metformin

6.7.3. SGLT2is

6.7.4. GLP-1RAs

6.7.5. Dual GLP-1 and Glucose Dependent Insulinotropic Polypeptide (GIP) Receptor Agonist (Dual GLP-1/GIP RA)

6.7.6. Imeglimin

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jia, L.; Quan, M.; Fu, Y.; Zhao, T.; Li, Y.; Wei, C.; Tang, Y.; Qin, Q.; Wang, F.; Qiao, Y.; et al. Dementia in China: epidemiology, clinical management, and research advances. Lancet. Neurol. 2020, 19, 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalal, S.; Ramirez-Gomez, J.; Sharma, B.; Devara, D.; Kumar, S. MicroRNAs and synapse turnover in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2024, 99, 102377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hardy, J.; Selkoe, D.J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: Progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002, 297, 353–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maccioni, R.B.; Farías, G.; Morales, I.; Navarrete, L. The revitalized tau hypothesis on Alzheimer’s disease. Arch. Med. Res. 2010, 41, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, A.V. Jr.; Buccafusco, J.J. The cholinergic hypothesis of age and Alzheimer’s disease-related cognitive deficits: Recent challenges and their implications for novel drug development. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003, 306, 821–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.; Boche, D.; Wilkinson, D.; Yadegarfar, G.; Hopkins, V.; Bayer, A.; Jones, R.W.; Bullock, R.; Love, S.; Neal, J.W.; et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunisation in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008, 372, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gravitz, L. Drugs: a tangled web of targets. Nature. 2011, 475, S9–S11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C.H.; Swanson, C.J.; Aisen, P.; Bateman, R.J.; Chen, C.; Gee, M.; Kanekiyo, M.; Li, D.; Reyderman, L.; Cohen, S. ; Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer's Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gozes, I. Tau pathology and future therapeutics. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 2010, 7, 685–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, M. Recent developments in tau-based therapeutics for neurodegenerative diseases. Recent. Pat. CNS. Drug. Discov. 2011, 6, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritchard, S.M.; Dolan, P.J.; Vitkus, A.; Johnson, G.V. The toxicity of tau in Alzheimer disease: turnover, targets and potential therapeutics. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 1621–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ott, A.; Stolk, R.P.; van Harskamp, F.; Pols, H.A.; Hofman, A.; Breteler, M.M. Diabetes mellitus and the risk of dementia: The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 1999, 53, 1937–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohara, T.; Doi, Y.; Ninomiya, T.; Hirakawa, Y.; Hata, J.; Iwaki, T.; Kanba, S.; Kiyohara, Y. Glucose tolerance status and risk of dementia in the community: the Hisayama study. Neurology. 2011, 77, 1126–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bigbee, J.W. Cells of the Central Nervous System: An Overview of Their Structure and Function. Adv. Neurobiol. 2023, 29, 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jurcovicova, J. Glucose transport in brain - effect of inflammation. Endocr. Regul. 2014, 48, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, F.; Davies-Hill, T.M.; Lysko, P.G.; Henneberry, R.C.; Simpson, I.A. Expression of two glucose transporters, GLUT1 and GLUT3, in cultured cerebellar neurons: Evidence for neuron-specific expression of GLUT3. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 1991, 2, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.S.; Reagan, L.P. Glucose transporter expression in the central nervous system: relationship to synaptic function. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 490, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grillo, C.A.; Piroli, G.G.; Hendry, R.M.; Reagan, L.P. Insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane in rat hippocampus is PI3-kinase dependent. Brain. Res. 2009, 1296, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson-Leary, J.; McNay, E.C. Novel roles for the insulin-regulated glucose transporter-4 in hippocampally dependent memory. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 11851–11864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, S.E.; Arvanitakis, Z.; Macauley-Rambach, S.L.; Koenig, A.M.; Wang, H.Y.; Ahima, R.S.; Craft, S.; Gandy, S.; Buettner, C.; Stoeckel, L.E.; et al. Brain insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer disease: concepts and conundrums. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 168–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, T.J.; Sun, M.K.; Hongpaisan, J.; Alkon, D.L. Insulin, PKC signaling pathways and synaptic remodeling during memory storage and neuronal repair. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008, 585, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heide, L.P.; Ramakers, G.M.; Smidt, M.P. Insulin signaling in the central nervous system: learning to survive. Prog. Neurobiol. 2006, 79, 205–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werther, G.A.; Hogg, A.; Oldfield, B.J.; McKinley, M.J.; Figdor, R.; Mendelsohn, F.A. Localization and characterization of insulin-like growth factor-i receptors in rat brain and pituitary gland using in vitro autoradiography and computerized densitometry* A distinct distribution from insulin receptors. J. Neuroendocrinol. 1989, 1, 369–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mielke, J.G.; Wang, Y.T. Insulin, synaptic function, and opportunities for neuroprotection. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2011, 98, 133–186. [Google Scholar]

- Gralle, M. The neuronal insulin receptor in its environment. J. Neurochem. 2017, 140, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadel, J.R.; Reagan, L.P. Stop signs in hippocampal insulin signaling: the role of insulin resistance in structural, functional and behavioral deficits. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2016, 9, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.G. Alzheimer’s disease and insulin resistance: translating basic science into clinical applications. J. Clin. Invest. 2013, 123, 531–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, S.L.; Chen, C.M.; Cline, H.T. Insulin receptor signaling regulates synapse number, dendritic plasticity, and circuit function in vivo. Neuron. 2008, 58, 708–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.C.; Huang, C.C.; Hsu, K.S. Insulin promotes dendritic spine and synapse formation by the PI3K/Akt/mTOR and Rac1 signaling pathways. Neuropharmacology. 2011, 61, 867–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.J.; Han, Y. Insulin inhibits AMPA-induced neuronal damage via stimulation of protein kinase B (Akt). J. Neural. Transm (Vienna). 2005, 112, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasile, F.; Dossi, E.; Rouach, N. Human astrocytes: structure and functions in the healthy brain. Brain. Struct. Funct. 2017, 222, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oberheim, N.A.; Goldman, S.A.; Nedergaard, M. Heterogeneity of astrocytic form and function. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2012, 814, 23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ransom, B.R.; Ransom, C.B. Astrocytes: multitalented stars of the central nervous system. Methods. Mol. Biol. 2012, 814, 3–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Benarroch, E.E. Neuron-astrocyte interactions: partnership for normal function and disease in the central nervous system. Mayo. Clin. Proc. 2005, 80, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wender, R.; Brown, A.M.; Fern, R.; Swanson, R.A.; Farrell, K.; Ransom, B.R. Astrocytic glycogen influences axon function and survival during glucose deprivation in central white matter. J. Neurosci. 2000, 20, 6804–6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellerin, L.; Pellegri, G.; Bittar, P.G.; Charnay, Y.; Bouras, C.; Martin, J.L.; Stella, N.; Magistretti, P.J. Evidence supporting the existence of an activity-dependent astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle. Dev. Neurosci. 1998, 20, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suzuki, A.; Stern, S.A.; Bozdagi, O.; Huntley, G.W.; Walker, R.H.; Magistretti, P.J.; Alberini, C.M. Astrocyte-neuron lactate transport is required for long-term memory formation. Cell. 2011, 144, 810–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waitt, A.E.; Reed, L.; Ransom, B.R.; Brown, A.M. Emerging roles for glycogen in the CNS. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rinholm, J.E.; Hamilton, N.B.; Kessaris, N.; Richardson, W.D.; Bergersen, L.H.; Attwell, D. Regulation of oligodendrocyte development and myelination by glucose and lactate. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrecht, J.; Wroblewska, B.; Mossakowski, M.J. The binding of insulin to cerebral capillaries and astrocytes of the rat. Neurochem. Res. 1982, 7, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garwood, C.J.; Ratcliffe, L.E.; Morgan, S.V.; Simpson, J.E.; Owens, H.; Vazquez-Villaseñor, I.; Heath, P.R.; Romero, I.A.; Ince, P.G.; Wharton, S.B. Insulin and IGF1 signalling pathways in human astrocytes in vitro and in vivo; characterisation, subcellular localisation and modulation of the receptors. Mol. Brain. 2015, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielman, L.J.; Bahniwal, M.; Little, J.P.; Walker, D.G.; Klegeris, A. Insulin modulates in vitro secretion of cytokines and cytotoxins by human glial cells. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 2015, 12, 684–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heni, M.; Hennige, A.M.; Peter, A.; Siegel-Axel, D.; Ordelheide, A.M.; Krebs, N.; Machicao, F.; Fritsche, A.; Häring, H.U.; Staiger, H. . Insulin promotes glycogen storage and cell proliferation in primary human astrocytes. PLoS. ONE. 2011, 6, e21594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D.W.; Boyd, F.T. Jr.; Kappy, M.S.; Raizada, M.K. Insulin binds to specific receptors and stimulates 2-deoxy-D-glucose uptake in cultured glial cells from rat brain. J. Biol. Chem. 1984, 259, 11672–11675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradl, M.; Lassmann, H. Oligodendrocytes: biology and pathology. Acta. Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Ding, W.G. The 45 kDa form of glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) is localized in oligodendrocyte and astrocyte but not in microglia in the rat brain. Brain. Res. 1998, 797, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, P.; Li, L.; Lund, P.K.; D’Ercole, A.J. Deficient expression of insulin receptor substrate-1 (IRS-1) fails to block insulin-like growth factor-I (IGF-I) stimulation of brain growth and myelination. Brain. Res. Dev. Brain. Res. 2002, 136, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Q.L.; Fragoso, G.; Miron, V.E.; Darlington, P.J.; Mushynski, W.E.; Antel, J.; Almazan, G. Response of human oligodendrocyte progenitors to growth factors and axon signals. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2010, 69, 930–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalsbeek, M.J.; Mulder, L.; Yi, C.X. Microglia energy metabolism in metabolic disorder. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2016, 438, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payne, J.; Maher, F.; Simpson, I.; Mattice, L.; Davies, P. Glucose transporter Glut 5 expression in microglial cells. Glia. 1997, 21, 327–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douard, V.; Ferraris, R.P. Regulation of the fructose transporter GLUT5 in health and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 295, E227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Pavlou, S.; Du, X.; Bhuckory, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, M. Glucose transporter 1 critically controls microglial activation through facilitating glycolysis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, J.J.; Attwell, D. The energetics of CNS white matter. J. Neurosci. 2012, 32, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonfeld, P.; Reiser, G. Why does brain metabolism not favor burning of fatty acids to provide energy? Reflections on disadvantages of the use of free fatty acids as fuel for brain. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013, 33, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D.; Haller, R.G.; Walton, M.E. Energy contribution of octanoate to intact rat brain metabolism measured by 13c nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 5928–5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panov, A.; Orynbayeva, Z.; Vavilin, V.; Lyakhovich, V. Fatty acids in energy metabolism of the central nervous system. BioMed. Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 472459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barber, C.N.; Raben, D.M. Lipid metabolism crosstalk in the brain: Glia and neurons. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, M.S.; Jackson, J.; Sheu, S.H.; Chang, C.L.; Weigel, A.V.; Liu, H.; Pasolli, H.A.; Xu, C.S.; Pang, S.; Matthies, D.; et al. Neuron-Astrocyte Metabolic Coupling Protects against Activity-Induced Fatty Acid Toxicity. Cell. 2019, 177, 1522–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, M.; Allaman, I.; Magistretti, P.J. Brain energy metabolism: focus on astrocyte-neuron metabolic cooperation. Cell. Metab. 2011, 14, 724–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unger, R.H.; Clark, G.O.; Scherer, P.E.; Orci, L. Lipid homeostasis, lipotoxicity and the metabolic syndrome. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010, 1801, 209–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.B.; Louie, S.M.; Daniele, J.R.; Tran, Q.; Dillin, A.; Zoncu, R.; Nomura, D.K.; Olzmann, J.A. DGAT1-Dependent Lipid Droplet Biogenesis Protects Mitochondrial Function during Starvation-Induced Autophagy. Dev. Cell. 2017, 42, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rambold, A.S.; Cohen, S.; Lippincott-Schwartz, J. Fatty acid trafficking in starved cells: regulation by lipid droplet lipolysis, autophagy, and mitochondrial fusion dynamics. Dev. Cell. 2015, 32, 678–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, P.; Reiser, G. Why does brain metabolism not favor burning of fatty acids to provide energy? Reflections on disadvantages of the use of free fatty acids as fuel for brain. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2013, 33, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schönfeld, P.; Reiser, G. How the brain fights fatty acids' toxicity. Neurochem. Int. 2021, 148, 105050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smolič, T.; Zorec, R.; Vardjan, N. Pathophysiology of Lipid Droplets in Neuroglia. Antioxidants (Basel). 2021, 11, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rone, M.B.; Cui, Q.L.; Fang, J.; Wang, L.C.; Zhang, J.; Khan, D.; Bedard, M.; Almazan, G.; Ludwin, S.K.; Jones, R.; et al. Oligodendrogliopathy in multiple sclerosis: Low glycolytic metabolic rate promotes oligodendrocyte survival. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 4698–4707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosko, L.; Smith, V.N.; Yamazaki, R. , Huang, J.K. Oligodendrocyte bioenergetics in health and disease. Neuroscientist. 2019, 25, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fünfschilling, U.; Supplie, L.M.; Mahad, D.; Boretius, S.; Saab, A.S.; Edgar, J.; Brinkmann, B.G.; Kassmann, C.M.; Tzvetanova, I.D.; Möbius, W.; et al. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. 2012, 485, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saab, A.S.; Tzvetanova, I.D.; Nave, K.A. The role of myelin and oligodendrocytes in axonal energy metabolism. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2013, 23, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Späte, E.; Zhou, B.; Sun, T.; Kusch, K.; Asadollahi, E.; Siems, S.B.; Depp, C.; Werner, H.B.; Saher, G.; Hirrlinger, J.; et al. Downregulated expression of lactate dehydrogenase in adult oligodendrocytes and its implication for the transfer of glycolysis products to axons. Glia. 2024, 72, 1374–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, M.G.F.; Pernin, F.; Antel, J.P.; Kennedy, T.E. From BBB to PPP: Bioenergetic requirements and challenges for oligodendrocytes in health and disease. J. Neurochem. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poitelon, Y.; Kopec, A.M.; Belin, S. Myelin fat facts: An overview of lipids and fatty acid metabolism. Cells. 2020, 9, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimas, P.; Montani, L.; Pereira, J.A.; Moreno, D.; Trötzmüller, M.; Gerber, J.; Semenkovich, C.F.; Köfeler, H.C.; Suter, U. CNS myelination and remyelination depend on fatty acid synthesis by oligodendrocytes. Elife. 2019, 8, e44702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, N.; Goudriaan, A.; van Deijk, A.F.; Otte, W.M.; Brouwers, J.F.; Lodder, H.; Gutmann, D.H.; Nave, K.A.; Dijkhuizen, R.M.; Mansvelder, H.D.; et al. Oligodendroglial myelination requires astrocyte-derived lipids. PLoS Biol. 2017, 15, e1002605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shemer, A.; Erny, D.; Jung, S.; Prinz, M. Microglia Plasticity during Health and Disease: An Immunological Perspective. Trends Immunol. 2015, 36, 614–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Qadri, Y.J.; Serhan, C.N.; Ji, R.R. Microglia in Pain: Detrimental and Protective Roles in Pathogenesis and Resolution of Pain. Neuron. 2018, 100, 1292–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loving, B.A.; Bruce, K.D. Lipid and Lipoprotein Metabolism in Microglia. Front Physiol. 2020, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakovcevski, I.; Filipovic, R.; Mo, Z.; Rakic, S.; Zecevic, N. Oligodendrocyte development and the onset of myelination in the human fetal brain. Front. Neuroanat. 2009, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.K.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, S.; Xia, Y.; Maciejewski, D.; McNamara, R.K.; Streit, W.J.; Salafranca, M.N.; Adhikari, S.; Thompson, D.A.; et al. Role for neuronally derived fractalkine in mediating interactions between neurons and CX3CR1-expressing microglia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 1998, 95, 10896–10901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barres, B.A.; Hart, I.K.; Coles, H.S.R.; Burne, J.F.; Voyvodic, J.T.; Richardson, W.D.; Raff, M.C. Cell death and control of cell survival in the oligodendrocyte lineage. Cell. 1992, 70, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, Z.; Zhou, L.; Darmanis, S.; Neff, N.F.; Okamoto, J.; Gulati, G.; Bennett, M.L.; Sun, L.O.; Clarke, L.E.; et al. Developmental Heterogeneity of Microglia and Brain Myeloid Cells Revealed by Deep Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Neuron. 2019, 101, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruce, K.D.; Gorkhali, S.; Given, K.; Coates, A.M.; Boyle, K.E.; Macklin, W.B.; Eckel, R.H. Lipoprotein Lipase Is a Feature of Alternatively-Activated Microglia and May Facilitate Lipid Uptake in the CNS During Demyelination. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, A.F.; Miron, V.E. The pro-remyelination properties of microglia in the central nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Sloan, S.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Caneda, C.; Plaza, C.A.; Blumenthal, P.D.; Vogel, H.; Steinberg, G.K.; Edwards, M.S.B.; Li, G.; et al. Purification and Characterization of Progenitor and Mature Human Astrocytes Reveals Transcriptional and Functional Differences with Mouse. Neuron. 2016, 89, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Sloan, S.A.; Bennett, M.L.; Scholze, A.R.; Keeffe, S.; Phatnani, H.P.; Guarnieri, P.; Caneda, C.; Ruderisch, N.; et al. An RNA-Sequencing Transcriptome and Splicing Database of Glia, Neurons, and Vascular Cells of the Cerebral Cortex. J. Neurosci. 2014, 34, 11929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Clavel, S.; Julien, P.; Murthy, M.R.; de Bilbao, F.; Arsenijevic, D.; Giannakopoulos, P.; Vallet, P.; Richard, D. Lipoprotein lipase and endothelial lipase expression in mouse brain: Regional distribution and selective induction following kainic acid-induced lesion and focal cerebral ischemia. Neurobiol. Dis. 2004, 15, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Bao, J.; Zhao, X.; Shen, H.; Lv, J.; Ma, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Wang, Q.; et al. Activated cyclin-dependent kinase 5 promotes microglial phagocytosis of fibrillar beta-amyloid by up-regulating lipoprotein lipase expression. Mol. Cell Proteom. 2013, 12, 2833–2844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Dong, W.; Rostad, S.W.; Marcovina, S.M.; Albers, J.J.; Brunzell, J.D.; Vuletic, S. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) is associated with neurite pathology and its levels are markedly reduced in the dentate gyrus of Alzheimer’s disease brains. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2013, 61, 857–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keren-Shaul, H.; Spinrad, A.; Weiner, A.; Matcovitch-Natan, O.; Dvir-Szternfeld, R.; Ulland, T.K.; David, E.; Baruch, K.; Lara-Astaiso, D.; Toth, B.; et al. A Unique Microglia Type Associated with Restricting Development of Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. 2017, 169, 1276–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruce, K.D.; Gorkhali, S.; Given, K.; Coates, A.M.; Boyle, K.E.; Macklin, W.B.; Eckel, R.H. Lipoprotein Lipase Is a Feature of Alternatively-Activated Microglia and May Facilitate Lipid Uptake in the CNS During Demyelination. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Vidal-Itriago, A.; Kalsbeek, M.J.; Layritz, C.; Garcia-Caceres, C.; Tom, R.Z.; Eichmann, T.O.; Vaz, F.M.; Houtkooper, R.H.; van der Wel, N.; et al. Lipoprotein Lipase Maintains Microglial Innate Immunity in Obesity. Cell. Rep. 2017, 20, 3034–3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Y.; Dong, J.; Song, J.; Lvy, C.; Zhang, Y. Efficacy of Glucose Metabolism-Related Indexes on the Risk and Severity of Alzheimer's Disease: A Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2023, 93, 1291–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuin, M.; Roncon, L.; Passaro, A.; Cervellati, C.; Zuliani, G. Metabolic syndrome and the risk of late onset Alzheimer's disease: An updated review and meta-analysis. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 31, 2244–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steen, E.; Terry, B.M.; Rivera, E.J.; Cannon, J.L.; Neely, T.R.; Tavares, R.; Xu, X.J.; Wands, J.R.; de la Monte, S.M. Impaired insulin and insulin-like growth factor expression and signaling mechanisms in Alzheimer's disease--is this type 3 diabetes? J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2005, 7, 63–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Grundke-Igbal, I.; Igbal, K.; Gong, C.X. Deficient brain insulin signalling pathway in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes. J. Pathol. 2011, 225, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, D.; Fava, A.; Plastino, M.; Montalcini, T.; Pujia, A. Possible implications of insulin resistance and glucose metabolism in Alzheimer's disease pathogenesis. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2011, 15, 1807–1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Monte, S.M. Insulin resistance and Alzheimer's disease. BMB. Rep. 2009, 42, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, P.I.; Cardoso, S.M.; Pereira, C.M.; Santos, M.S.; Oliveira, C.R. Mitochondria as a therapeutic target in Alzheimer's disease and diabetes CNS. Neurol. Disord. Drug. Targets. 2009, 8, 492–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhu, R.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Q. Lipid levels and the risk of dementia: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2022, 9, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, A.P.; Vattathil, S.M.; Liu, J.; Fan, W.; Cutler, D.J.; Levey, A.I.; Schneider, J.A.; Bennett, D.A.; Wingo, T.S. LDL cholesterol is associated with higher AD neuropathology burden independent of APOE. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2022, 93, 930–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáiz-Vazquez, O.; Puente-Martínez, A.; Ubillos-Landa, S.; Pacheco-Bonrostro, J.; Santabárbara, J. Cholesterol and Alzheimer's Disease Risk: A Meta-Meta-Analysis. Brain. Sci. 2020, 10, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Q.; Wang, F.; Yang, J.; Peng, H.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, S. Revealing a Novel Landscape of the Association Between Blood Lipid Levels and Alzheimer's Disease: A Meta-Analysis of a Case-Control Study. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Jia, X.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, K. Prediction of Alzheimer's disease with serum lipid levels in Asian individuals: a meta-analysis. Biomarkers. 2019, 24, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuin, M.; Cervellati, C.; Trentini, A.; Passaro, A.; Rosta, V.; Zimetti, F.; Zuliani, G. Association between Serum Concentrations of Apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I) and Alzheimer's Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Diagnostics (Basel). 2021, 11, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippini, N.; MacIntosh, B.J.; Hough, M.G.; Goodwin, G.M.; Frisoni, G.B.; Smith, S.M.; Matthews, P.M.; Beckmann, C.F.; Mackay, C.E. Distinct patterns of brain activity in young carriers of the APOE-epsilon4 allele. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009, 106, 7209–7214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corder, E.H.; Saunders, A.M.; Strittmatter, W.J.; Schmechel, D.E.; Gaskell, P.C.; Small, G.W.; Roses, A.D.; Haines, J.L.; Pericak-Vance, M.A. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993, 261, 921–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrer, L.A.; Cupples, L.A.; Haines, J.L.; Hyman, B.; Kukull, W.A.; Mayeux, R.; Myers, R.H.; Pericak-Vance, M.A.; Risch, N.; van Duijn, C.M. Effects of age, sex, and ethnicity on the association between apolipoprotein E genotype and Alzheimer disease. A meta-analysis. APOE and Alzheimer disease meta analysis consortium. JAMA. 1997, 278, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stalmans, P.; Parys-Vanginderdeuren, R.; De Vos, R.; Feron, E.J. ICG staining of the inner limiting membrane facilitates its removal during surgery for macular holes and puckers. Bull. Soc. Belge. Ophtalmol. 2001, 281, 21–26. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, H.; Fu, J.; Mohammed Nazar, R.B.; Yang, J.; Chen, S.; Huang, Y.; Bao, T.; Chen, X. Investigation of the Relationship between Apolipoprotein E Alleles and Serum Lipids in Alzheimer's Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Brain. Sci. 2023, 13, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothandan, D.; Singh, D.S.; Yerrakula, G.; D, B.; N, P.; Santhana Sophia, B.V.; A, R.; Ramya Vg, S.; S, K.; M, J. Advanced Glycation End Products-Induced Alzheimer's Disease and Its Novel Therapeutic Approaches: A Comprehensive Review. Cureus. 2024, 16, e61373.

- Park, I.H.; Yeon, S.I.; Youn, J.H.; Choi, J.E.; Sasaki, N.; Choi, I.H.; Shin, J.S. Expression of a novel secreted splice variant of the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE) in human brain astrocytes and peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol. Immunol. 2004, 40, 1203–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emanuele, E.; D'Angelo, A.; Tomaino, C.; Binetti, G.; Ghidoni, R.; Politi, P.; Bernardi, L.; Maletta, R.; Bruni, A.C.; Geroldi, D. Circulating levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer disease and vascular dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2005, 62, 1734–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Liu, N.; Wang, C.; Qin, B.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, M.; Chang, L.; Yan, L.J.; Zhao, B. Role of RAGE in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016, 36, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.F.; Ramasamy, R.; Schmidt, A.M. Receptor for AGE (RAGE) and its ligands-cast into leading roles in diabetes and the inflammatory response. J. Mol. Med. 2009, 87, 235–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.Y.; Deng, C.Q.; Wang, J.; Deng, X.J.; Xiao, Q.; Li, Y.; He, Q.; Fan, W.H.; Quan, F.Y.; Zhu, Y.P.; et al. Plasma levels of soluble receptor for advanced glycation end products in Alzheimer’s disease. Int. J. Neurosci. 2017, 127, 454–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, W.H.; Chen, W.; Jiang, L.Y.; Yang, Y.X.; Yao, L.F.; Li, K.S. Influence of ADAM10 Polymorphisms on Plasma Level of Soluble Receptor for Advanced Glycation End Products and The Association With Alzheimer's Disease Risk. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Song, X.; Zhu, C.; Patrick, R.; Skurla, M.; Santangelo, I.; Green, M.; Harper, D.; Ren, B.; Forester, B.P.; et al. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2021, 72, 101503.

- Trares, K.; Chen, L.J.; Schöttker, B. Association of F(2)-isoprostane levels with Alzheimer's disease in observational studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2022, 74, 101552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrag, M.; Mueller, C.; Zabel, M.; Crofton, A.; Kirsch, W.M.; Ghribi, O.; Squitti, R.; Perry, G. Oxidative stress in blood in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis. Neurobiol. Dis. 2013, 59, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varikasuvu, S.R.; Prasad, V.S.; Kothapalli, J.; Manne, M. Brain Selenium in Alzheimer's Disease (BRAIN SEAD Study): a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2019, 189, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buonacera, A.; Stancanelli, B.; Colaci, M.; Malatino, L. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio: an emerging marker of the relationships between the immune system and diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahorec, R. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, past, present and future perspectives. Bratisl. Lek. Listy. 2021, 122, 474–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, A.; Mohammadi, M.; Almasi-Dooghaee, M.; Mirmosayyeb, O. Neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio in Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS. One. 2024, 19, e0305322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cumming, P.; Burgher, B.; Patkar, O.; Breakspear, M.; Vasdev, N.; Thomas, P.; Liu, G.J.; Banati, R. Sifting through the surfeit of neuroinflammation tracers. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2018, 38, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Hu, K.; Shao, T.; Hou, L.; Zhang, S.; Ye, W.; Josephson, L.; Meyer, J.H.; Zhang, M.R.; Vasdev, N.; et al. Recent developments on PET radiotracers for TSPO and their applications in neuroimaging. Acta. Pharm. Sin. B. 2021, 11, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Picker, L.J.; Morrens, M.; Branchi, I.; Haarman, B.C.M.; Terada, T.; Kang, M.S.; Boche, D.; Tremblay, M.E.; Leroy, C.; Bottlaender, M.; et al. TSPO PET brain inflammation imaging: A transdiagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis of 156 case-control studies. Brain. Behav. Immun. 2023, 113, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, P.L.; Chou, K.H.; Chung, C.P.; Lai, T.H.; Zhou, J.H.; Wang, P.N.; Lin, C.P. Posterior cingulate cortex network predicts Alzheimer’s disease progression. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2020, 12, 608667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillardon, F.; Rist, W.; Kussmaul, L.; Vogel, J.; Berg, M.; Danzer, K.; Kraut, N.; Hengerer, B.; et al. Proteomic and functional alterations in brain mitochondria from Tg2576 mice occur before amyloid plaque deposition. Proteomics. 2007, 7, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, A.H.; Dar, K.B.; Anees, S.; Zargar, M.A.; Masood, A.; Sofi, M.A.; Ganie, S.A.; et al. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and neurodegenerative diseases; a mechanistic insight. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2015, 74, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, V.; Lodi, R.; Tonon, C.; D’Agata, V.; Sapienza, M.; Scapagnini, G.; Mangiameli, A.; Pennisi, G.; Stella, A.M.; Butterfield, D.A. Oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction and cellular stress response in Friedreich’s ataxia. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 233, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perry, G.; Cash, A.D.; Smith, M.A. Alzheimer disease and oxidative stress. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2002, 2, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, T.; Obi, T.; Bunai, T.; Matsudaira, T.; Yoshikawa, E.; Ando, I.; Futatsubashi, M.; Tsukada, H.; Ouchi, Y. In vivo mitochondrial and glycolytic impairments in patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2020, 94, e1592–e1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abyadeh, M.; Gupta, V.; Chitranshi, N.; Gupta, V.; Wu, Y.; Saks, D.; Wander Wall, R.; Fitzhenry, M.J.; Basavarajappa, D.; You, Y.; et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease - a proteomics perspective. Expert. Rev. Proteomics. 2021, 18, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klionsky, D.J.; Abdel-Aziz, A.K.; Abdelfatah, S.; Abdellatif, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abel, S.; et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (4th edition) 1. Autophagy. 2021, 17, 1–382. [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima, N.; Levine, B. Autophagy in human diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 1564–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riahi, Y.; Wikstrom, J.D.; Bachar-Wikstrom, E.; Polin, N.; Zucker, H.; Lee, M.S.; Quan, W.; Haataja, L.; Liu, M.; Arvan, P.; et al. Autophagy is a major regulator of beta cell insulin homeostasis. Diabetologia. 2016, 59, 1480–1491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherniya, M.; Butler, A.E.; Barreto, G.E.; Sahebkar, A. The effect of fasting or calorie restriction on autophagy induction: A review of the literature. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nixon, R.A. Amyloid precursor protein and endosomal-lysosomal dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease: inseparable partners in a multifactorial disease. FASEB. J. 2017, 31, 2729–2743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krance, S.H.; Wu, C.Y.; Chan, A.C.Y.; Kwong, S.; Song, B.X.; Xiong, L.Y.; Ouk, M.; Chen, M.H.; Zhang, J.; Yung, A.; et al. Endosomal-Lysosomal and Autophagy Pathway in Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2022, 88, 1279–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henriksen, E.J.; Dokken, B.B. Role of glycogen synthase kinase-3 in insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Curr. Drug. Targets. 2006, 7, 1435–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, A.; Roy, S.; Das, D.; Marturi, V.; Mondal, C.; Patra, S.; Haldar, P.K.; Samajdar, G. Role of Glycogen Synthase Kinase-3 in the Etiology of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Review. Curr. Diabetes. Rev. 2022, 18, e300721195147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Wei, M.; Guo, M.; Wang, M.; Niu, H.; Xu, T.; Zhou, Y. GSK3: A potential target and pending issues for treatment of Alzheimer's disease. CNS. Neurosci. Ther. 2024, 30, e14818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akter, R.; Cao, P.; Noor, H.; Ridgway, Z.; Tu, L.H.; Wang, H.; Wong, A.G.; Zhang, X.; Abedini, A.; Schmidt, A.M.; et al. Islet Amyloid Polypeptide: Structure, Function, and Pathophysiology. J. Diabetes. Res. 2016, 2016, 2798269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreno-Gonzalez, I.; Edwards Iii, G.; Salvadores, N.; Shahnawaz, M.; Diaz-Espinoza, R.; Soto, C. Molecular interaction between type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer's disease through cross-seeding of protein misfolding. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017, 22, 1327–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Claud, S.L.; Cantrell, K.L.; Bowers, M.T. Catalytic Prion-Like Cross-Talk between a Key Alzheimer's Disease Tau-Fragment R3 and the Type 2 Diabetes Peptide IAPP. ACS. Chem. Neurosci. 2019, 10, 4757–4765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Meng, L.; Wang, Z.; Peng, Q.; Chen, G.; Xiong, J.; Zhang, Z. Islet amyloid polypeptide cross-seeds tau and drives the neurofibrillary pathology in Alzheimer's disease. Mol. Neurodegener. 2022, 17, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, I.A.; Carruthers, A.; Vannucci, S.J. Supply and demand in cerebral energy metabolism: the role of nutrient transporters. J. Cereb. Blood. Flow. Metab. 2007, 27, 1766–1791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, A.F.; Nissen, J.D.; Garcia-Serrano, A.M.; Nussbaum, S.; Waagepetersen, H.S.; Duarte, J.M.N. (2019). Glycogen metabolism is impaired in the brain of male type 2 diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 2019, 97, 1004–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kothari, V.; Luo, Y.; Tornabene, T.; O’Neill, A.M.; Greene, M.W.; Geetha, T. , Babu, J.R. High fat diet induces brain insulin resistance and cognitive impairment in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017, 1863, 499–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Patil, I.Y.; Jiang, T.; Sancheti, H.; Walsh, J.P.; Stiles, B.L. , Yin, F.; Cadenas, E. (2015). High-fat diet induces hepatic insulin resistance and impairment of synaptic plasticity. PLoS. One. 2015, 10, e0128274. [Google Scholar]

- Yonamine, C.Y.; Passarelli, M.; Suemoto, C.K.; Pasqualucci, C.A.; Jacob-Filho, W.; Alves, V.A.F.; Marie, S.K.N.; Correa-Giannella, M.L.; Britto, L.R.; Machado, U.F. Postmortem Brains from Subjects with Diabetes mellitus display reduced GLUT4 expression and soma area in hippocampal neurons: Potential involvement of inflammation. Cells. 2023, 12, 1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyrtata, N.; Emsley, H.C.A.; Sparasci, O.; Parkes, L.M.; Dickie, B.R. A Systematic Review of Glucose Transport Alterations in Alzheimer's Disease. Front. Neurosci. 2021, 15, 626636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cartier, N.; Lewis, C.A.; Zhang, R.; Rossi, FM. The role of microglia in human disease: therapeutic tool or target? Acta. Neuropathol. 2014, 128, 363–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pavlou, S.; Du, X.; Bhuckory, M.; Xu, H.; Chen, M. Glucose transporter 1 critically controls microglial activation through facilitating glycolysis. Mol. Neurodegener. 2019, 14, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, X.; Wind, K.; Wiedemann, T.; Blume, T.; Shi, Y.; Briel, N.; Beyer, L.; Biechele, G.; Eckenweber, F.; Zatcepin, A.; et al. Microglial activation states drive glucose uptake and FDG-PET alterations in neurodegenerative diseases. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabe5640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson-Leary, J.; McNay, E.C. Intrahippocampal administration of amyloid-beta(l-42) oligomers acutely impairs spatial working memory, insulin signaling, and hippocampal metabolism. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2012, 30, 413–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choeiri, C.; Staines, W.; Messier, C. Immunohistochemical localization and quantification of glucose transporters in the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2002, 111, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selkoe, D.J. Alzheimer’s Disease Is a Synaptic Failure. Science. 2002, 298, 789–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, P.; Maloney, A.J.F. Selective loss of central cholinergic neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet. 1976, 308, 1403–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, F.; Grundke-Iqbal, I.; Iqbal, K.; Gong, C.X. Brain glucose transporters, O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of tau in diabetes and Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurochem. 2009, 111, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaper, S.D. The brain as a target for inflammatory processes and neuroprotective strategies. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1122, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Debernardi, R.; Pierre, K.; Lengacher, S.; Magistretti, P.J.; Pellerin, L. Cell-specific expression pattern of monocarboxylate transporters in astrocytes and neurons observed in different mouse brain cortical cell cultures. J. Neurosci. Res. 2003, 73, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khatri, N.; Man, H.Y. Synaptic activity and bioenergy homeostasis: implications in brain trauma and neurodegenerative diseases. Front. Neurol. 2013, 4, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitlock, J.R.; Heynen, A.J.; Shuler, M.G. , Bear, M.F. Learning induces long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. Science. 2006, 313, 1093–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Mendez, A.; Almeida, A.; Fernández, E.; Maestre, C.; Moncada, S.; Bolaños, J.P. The bioenergetic and antioxidant status of neurons is controlled by continuous degradation of a key glycolytic enzyme by APC/C-Cdh1. Nat. Cell Biol. 2009, 11, 747–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, T.; Jesmin, S.; Matsui, T.; Soya, M.; Soya, H. Differential effects of type 2 diabetes on brain glycometabolism in rats: focus on glycogen and monocarboxylate transporter 2. J. Physiol. Sci. 2018, 68, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Cheng, X.; Dang, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Yao, Z. Lactate Deficit in an Alzheimer Disease Mouse Model: The Relationship With Neuronal Damage. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2018, 77, 1163–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, C.E.; Veerhuis, R.; De Vente, J.; Verhey, F.R.; Vreeling, F.; van Boxtel, M.P.; Glatz, J.F.; Pelsers, M.A. Brain-specific fatty acid-binding protein is elevated in serum of patients with dementia-related diseases. Eur. J. Neurol. 2011, 18, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosén, C.; Mattsson, N.; Johansson, P.M.; Andreasson, U.; Wallin, A.; Hansson, O.; Johansson, J.O.; Lamont, J.; Svensson, J.; Blennow, K.; et al. Discriminatory Analysis of Biochip-Derived Protein Patterns in CSF and Plasma in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2011, 3, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.T.; Chen-Plotkin, A.; Arnold, S.E.; Grossman, M.; Clark, C.M.; Shaw, L.M.; Pickering, E.; Kuhn, M.; Chen, Y.; McCluskey, L.; et al. Novel CSF biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment. Acta. Neuropathol. 2010, 119, 669–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammerschmidt, P.; Brüning, J.C. Contribution of Specific Ceramides to Obesity-Associated Metabolic Diseases. Cell. Mol. Life. Sci. 2022, 79, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boslem, E.; Meikle, P.J.; Biden, T.J. Roles of Ceramide and Sphingolipids in Pancreatic β-Cell Function and Dysfunction. Islets. 2012, 4, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paumen, M.B.; Ishida, Y.; Muramatsu, M.; Yamamoto, M.; Honjo, T. Inhibition of Carnitine Palmitoyltransferase I Augments Sphingolipid Synthesis and Palmitate-Induced Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 3324–3329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ji, R.; Akashi, H.; Drosatos, K.; Liao, X.; Jiang, H.; Kennel, P.J.; Brunjes, D.L.; Castillero, E.; Zhang, X.; Deng, L.Y.; et al. Increased de Novo Ceramide Synthesis and Accumulation in Failing Myocardium. JCI. Insight. 2017, 2, e82922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazvinšćak Jembrek, M.; Hof, P.R.; Šimić, G. Ceramides in Alzheimer’s Disease: Key Mediators of Neuronal Apoptosis Induced by Oxidative Stress and Aβ Accumulation. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2015, 2015, 346783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.; Melrose, J.; Chan, C. Involvement of Astroglial Ceramide in Palmitic Acid-Induced Alzheimer-like Changes in Primary Neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 26, 2131–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filippov, V.; Song, M.A.; Zhang, K.; Vinters, H.V.; Tung, S.; Kirsch, W.M.; Yang, J.; Duerksen-Hughes, P.J. Increased Ceramide in Brains with Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Alzheimer’s. Dis. 2012, 29, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Z.; Li, Z.Y.; Yu, M.T.; Tan, K.L.; Chen, S. Metabolic perspective of astrocyte dysfunction in Alzheimer's disease and type 2 diabetes brains. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, Y.; Qi, G.; Vitali, F.; Shang, Y.; Raikes, A.C.; Wang, T.; Jin, Y.; Brinton, R.D.; Gu, H.; Yin, F. Loss of fatty acid degradation by astrocytic mitochondria triggers neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration. Nat. Metab. 2023, 5, 445–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Jing, G.; Ma, M.; Yin, R.; Zhang, M. Microglial activation and polarization in type 2 diabetes-related cognitive impairment: A focused review of pathogenesis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2024, 165, 105848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loving, B.A.; Tang, M.; Neal, M.C.; Gorkhali, S.; Murphy, R.; Eckel, R.H.; Bruce, K.D. Lipoprotein Lipase Regulates Microglial Lipid Droplet Accumulation. Cells. 2021, 10, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Li, Q.; Cong, W.; Mu, S.; Zhan, R.; Zhong, S.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, C.; Kang, K.; Zhou, Z. Effect of physical activity on risk of Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis of twenty-nine prospective cohort studies. Ageing. Res. Rev. 2023, 92, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hu, X.; Zhang, L.; Xiong, Z.; Bai, Y.; Zeng, J.; Xu, F. Effective dosage and mode of exercise for enhancing cognitive function in Alzheimer's disease and dementia: a systematic review and Bayesian Model-Based Network Meta-analysis of RCTs. BMC. Geriatr. 2024, 24, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godos, J.; Micek, A.; Currenti, W.; Franchi, C.; Poli, A.; Battino, M.; Dolci, A.; Ricci, C.; Ungvari, Z.; Grosso, G. Fish consumption, cognitive impairment and dementia: an updated dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Aging. Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nucci, D.; Sommariva, A.; Degoni, L.M.; Gallo, G.; Mancarella, M.; Natarelli, F.; Savoia, A.; Catalini, A.; Ferranti, R.; Pregliasco, F.E.; et al. Association between Mediterranean diet and dementia and Alzheimer disease: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Aging. Clin. Exp. Res. 2024, 36, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashley, S.; Bradburn, S.; Murgatroyd, C. A meta-analysis of peripheral tocopherol levels in age-related cognitive decline and Alzheimer's disease. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 795–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Shu, Y.; Chen, T.; Xu, L.; Li, M.; Guan, X. Do low-serum vitamin E levels increase the risk of Alzheimer disease in older people? Evidence from a meta-analysis of case-control studies. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry. 2018, 33, e257–e263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Han, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, S.; Li, R.; Cai, H.; You, H. Association of vitamin E intake in diet and supplements with risk of dementia: A meta-analysis. Front. Aging. Neurosci. 2022, 14, 955878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Lu, Y.; Chen, M.; He, Y.; Xu, H.; Zheng, L. The impact of plasma vitamin C levels on the risk of cardiovascular diseases and Alzheimer's disease: A Mendelian randomization study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 5327–5334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Xie, X.; Zhang, H.; Liu, T. Effect of antioxidant intake patterns on risks of dementia and cognitive decline. Eur. Geriatr. Med. 2023, 14, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surya, K.; Manickam, N.; Jayachandran, K.S.; Kandasamy, M.; Anusuyadevi, M. Resveratrol Mediated Regulation of Hippocampal Neuroregenerative Plasticity via SIRT1 Pathway in Synergy with Wnt Signaling: Neurotherapeutic Implications to Mitigate Memory Loss in Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2023, 94, S125–S140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, S.; Guan, X.; Min, D. Evidence of Clinical Efficacy and Pharmacological Mechanisms of Resveratrol in the Treatment of Alzheimer's Disease. Curr. Alzheimer. Res. 2023, 20, 588–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, X.; Wang, R.; Han, L.; Li, H.; Zhao, W. Mechanisms of 3-Hydroxyl 3-Methylglutaryl CoA Reductase in Alzheimer's Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 25, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmastroni, E.; Molari, G.; De Beni, N.; Colpani, O.; Galimberti, F.; Gazzotti, M.; Zambon, A.; Catapano, A.L.; Casula, M. Statin use and risk of dementia or Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2022, 29, 804–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wójtowicz, S.; Strosznajder, A.K.; Jeżyna, M.; Strosznajder, J.B. The Novel Role of PPAR Alpha in the Brain: Promising Target in Therapy of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Neurodegenerative Disorders. Neurochem. Res. 2020, 45, 972–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Fujioka, H.; Wang, W.; Zhu, X. Bezafibrate confers neuroprotection in the 5xFAD mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Mol. Basis. Dis. 2023, 1869, 166841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, Y.; Qiao, P.F.; Zhao, F.L.; Yan, Y. Fenofibrate reduces amyloidogenic processing of APP in APP/PS1 transgenic mice via PPAR-α/PI3-K pathway. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 2014, 38, 223–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Ding, Y.; Wu, F.; Li, R.; Hou, J.; Mao, P. Omega-3 fatty acids intake and risks of dementia and Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 48, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon Martinez, E.; Zachariah Saji, S.; Salazar Ore, J.V.; Borges-Sosa, O.A.; Srinivas, S.; Mareddy, N.S.R.; Manzoor, T.; Di Vanna, M.; Al Shanableh, Y.; Taneja, R.; et al. The effects of omega-3, DHA, EPA, Souvenaid in Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychopharmacol. Rep. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuate Defo, A.; Bakula, V.; Pisaturo, A.; Labos, C.; Wing, S.S.; Daskalopoulou, S.S. Diabetes, antidiabetic medications and risk of dementia: A systematic umbrella review and meta-analysis. Diabetes. Obes. Metab. 2024, 26, 441–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basutkar, R.S.; Sudarsan, P.; Robin, S.M.; Bhaskar, V.; Viswanathan, B.; Sivasankaran, P. Drug Repositioning of Pioglitazone in Management and Improving the Cognitive Function among the Patients With Mild to Moderate Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neurol. India. 2023, 71, 1132–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunwoo, Y.; Park, J.; Choi, C.Y.; Shin, S.; Choi, Y.J. Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer's Disease Associated With Antidiabetics: A Bayesian Network Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2024, 67, 434–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.H.; Zhang, X.Y.; Sun, Y.Q.; Lv, R.H.; Chen, M.; Li, M. Metformin use is associated with a reduced risk of cognitive impairment in adults with diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Neurosci. 2022, 16, 984559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, A.; Ning, P.; Lu, H.; Huang, H.; Shen, Q.; Zhang, D.; Xu, F.; Yang, L.; Xu, Y. Association Between Metformin and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Observational Studies. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2022, 88, 1311–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, D.; Cao, F.; Xiao, W.; Zhao, L.; Ding, G.; Wang, Z.Z. Identification of Human Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors from the Constituents of EGb761 by Modeling Docking and Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Comb. Chem. High. Throughput. Screen. 2018, 21, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H.; Mesulam, M.M.; Cuello, A.C.; Farlow, M.R.; Giacobini, E.; Grossberg, G.T.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Vergallo, A.; Cavedo, E.; Snyder, P.J.; et al. The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2018, 141, 1917–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arafa, N.M.S.; Ali, E.H.A.; Hassan, M.K. Canagliflozin prevents scopolamine-induced memory impairment in rats: comparison with galantamine hydrobromide action. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 277, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanciu, G.D.; Ababei, D.C.; Solcan, C.; Bild, V.; Ciobica, A.; Beschea Chiriac, S.I.; Ciobanu, L.M.; Tamba, B.I. Preclinical Studies of Canagliflozin, a Sodium-Glucose Co-Transporter 2 Inhibitor, and Donepezil Combined Therapy in Alzheimer's Disease. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023, 16, 1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, P.; Liang, L.; Dai, Y.; Hui, S. The role and mechanism of dapagliflozin in Alzheimer disease: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024, 103, e39687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, M.G.; García-Lluch, G.; Moreno, L.; Pardo, J.; Pericas, C.C. Assessment of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and other antidiabetic agents in Alzheimer's disease: A population-based study. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 206, 107295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.K.; Biessels, G.J.; Yu, M.H.; Hong, N.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, B.W.; Kang, E.S.; Cha, B.S.; Lee, E.J.; Lee, M. SGLT2 Inhibitor Use and Risk of Dementia and Parkinson Disease Among Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Neurology. 2024, 103, e209805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClean, P.L.; Parthsarathy, V.; Faivre, E.; Hölscher, C. The diabetes drug liraglutide prevents degenerative processes in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 6587–6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Wu, T.; Dai, J.; Zhai, Z.; Cai, J.; Zhu, Z.; Xu, Y.; Sun, T. Glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in experimental Alzheimer's disease models: a systematic review and meta-analysis of preclinical studies. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1205207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Femminella, G.D.; Frangou, E.; Love, S.B.; Busza, G.; Holmes, C.; Ritchie, C.; Lawrence, R.; McFarlane, B.; Tadros, G.; Ridha, B.H.; et al. Correction to: Evaluating the effects of the novel GLP-1 analogue liraglutide in Alzheimer's disease: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial (ELAD study). Trials. 2020, 21, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.J.; Li, X.R.; Chai, S.F.; Li, W.R.; Li, S.; Hou, M.; Li, J.L.; Ye, Y.C.; Cai, H.Y.; Hölscher, C.; et al. Semaglutide ameliorates cognition and glucose metabolism dysfunction in the 3xTg mouse model of Alzheimer's disease via the GLP-1R/SIRT1/GLUT4 pathway. Neuropharmacology. 2023, 240, 109716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hölscher, C. Glucagon-like peptide-1 class drugs show clear protective effects in Parkinson's and Alzheimer's disease clinical trials: A revolution in the making? Neuropharmacology. 2024, 253, 109952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.Q.; Hölscher, C. GIP has neuroprotective effects in Alzheimer and Parkinson's disease models. Peptides. 2020, 125, 170184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L.; Hölscher, C. A novel dual GLP-1/GIP receptor agonist alleviates cognitive decline by re-sensitizing insulin signaling in the Alzheimer icv. STZ rat model. Behav. Brain. Res. 2017, 327, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.Y.; Yang, D.; Qiao, J.; Yang, J.T.; Wang, Z.J.; Wu, M.N.; Qi, J.S.; Hölscher, C. A GLP-1/GIP Dual Receptor Agonist DA4-JC Effectively Attenuates Cognitive Impairment and Pathology in the APP/PS1/Tau Model of Alzheimer's Disease. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2021, 83, 799–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maskery, M.; Goulding, E.M.; Gengler, S.; Melchiorsen, J.U.; Rosenkilde, M.M.; Hölscher, C. The Dual GLP-1/GIP Receptor Agonist DA4-JC Shows Superior Protective Properties Compared to the GLP-1 Analogue Liraglutide in the APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease. Am. J. Alzheimers. Dis. Other. Demen. 2020, 35, 1533317520953041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatton, W.G.; Chalmers-Redman, R.M. Mitochondria in neurodegenerative apoptosis: an opportunity for therapy? Ann. Neurol. 1998, 44, S134–S141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanai, H.; Adachi, H.; Hakoshima, M.; Katsuyama, H. Glucose-Lowering Effects of Imeglimin and Its Possible Beneficial Effects on Diabetic Complications. Biology (Basel). 2023, 12, 726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zemgulyte, G.; Umbrasas, D.; Cizas, P.; Jankeviciute, S.; Pampuscenko, K.; Grigaleviciute, R.; Rastenyte, D.; Borutaite, V. Imeglimin Is Neuroprotective Against Ischemic Brain Injury in Rats-a Study Evaluating Neuroinflammation and Mitochondrial Functions. Mol. Neurobiol. 2022, 59, 2977–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Glucose transporters | Type 2 diabetes | AD |

| GLUT1 | ↓ | ↓(↑ in microglia) |

| GLUT2 | Unknown | ↑(in astrocytes) |

| GLUT3 | ↓ | ↓ |

| GLUT4 | ↓ | Translocation↓ |

| Risk factors | Possible therapeutic interventions |

| High LDL-C | Diet, Exercise, Statin |

| High TG | Diet, Exercise, PPAR-a agonists, n3-PUFA |

| Low HDL-C | Diet, Exercise, Stain, PPAR-a agonists |

| Apo E abnormality | PPAR-a agonists |

| Insulin resistance | Diet, Exercise, Metformin, Pioglitazone, SGLT2is, GLP-1RAs |

| Oxidative stress | Antioxidants (Vitamin C and E, Polyphenols) |

| Mitochondrial dysfunction | Imeglimin |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).