1. Introduction

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease that affects over 105,000 people worldwide. High prevalence is mainly found in the Caucasian population in the northern hemisphere, with recently published studies suggesting an unreported figure of over 50,000 in other parts of the world [

1]. CF is caused by mutations in the gene encoding the CFTR (Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator) channel protein, located in the secretory glandular epithelium of multiple organ systems such as the airways, sweat glands, gastrointestinal tract, hepatobiliary system, reproductive system, and pancreas, where it plays an important role in epithelial bicarbonate and chloride transport. More precisely, the disturbed metabolism causes a pathologically composed glandular secretion, the removal of which is disturbed by increased viscosity. CF is therefore characterized by pulmonary obstruction, pancreatic insufficiency, reduced fertility, and an increased salt content in sweat [

2]. Currently, people with CF (pwCF) in Germany still have a reduced life expectancy, due to cardiopulmonary causes, diabetes, liver failure [

3]. As a chronic and life-shortening illness, CF leads to twice the prevalence of depression and anxiety disorders in pwCF and their caregivers compared to the normal population [

4].

CFTR modulators are small molecules that intervene directly in the defective CFTR protein production and can also improve the function of the CFTR channels [

5]. Since 2020, the CFTR modulator Elexcaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor (ETI) has been the first highly efficient causal therapeutic approach on the market for the vast majority of pwCF in the European Union (EU). More specifically, ETI is currently authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) for all pwCF aged 2 years and older with at least one phe508del CFTR mutation [

6], but not for pwCF with much rarer non-phe508del mutations.

Clinically, the effect of CFTR modulators is primarily seen in an improvement in lung function (FEV1), sweat chloride levels, BMI, and a reduction in exacerbations [

6,

7]. Only recently, over 2600 pwCF in Germany were evaluated for 24 weeks under ETI therapy and positive effects of ETI on lung function, sweat chloride concentration and results of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire revised (CFQ-R) were confirmed [

8]. Since the introduction of ETI, life expectancy of newborn pwCF in Germany has increased from 53 years in 2019 to 60 years in 2022 [

3,

9].

In addition to the classic improvements in FEV1, BMI and sweat chloride concentration, improvements in physical resilience [

10] or improvement in the situation of the upper airways have now also been shown. The improved ENT symptoms under ETI have been demonstrated in several studies by significant improved results in the Sinonasal Outcome Test 22 (SNOT-22) questionnaire [

11,

12,

13] as well as by radiological imaging [

14] and through objective examinations by an otorhinolaryngologist [

15]. Even though there are some case reports on the occurrence of ETI associated depression and anxiety [

16,

17], a recently published review which considered over 14 clinical trials and over 60,000 pwCF under ETI could not prove a causal relationship between ETI and depression and a prospective study from 2023 even reported a significant decrease in depressive symptoms under ETI therapy [

18,

19].

In contrast to the EU, the ETI authorization in the USA was extended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to include 177 rarer non-phe508del CFTR mutations, which were not necessarily responsive to Ivacaftor or Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor [

6], but for which the ETI-producing pharmaceutical company had provided unpublished in vitro data, with demonstrable CFTR function, regardless of the mutation class or the underlying mechanism, therefore defined as “responsive” to ETI [

20]. This was based on the following in vitro data: CFTR wild-type activity was measured in Fisher rat thyroid (FRT) cell cultures transduced with various CFTR mutations after the addition of ETI. ETI was considered effective for the respective CFTR mutation if chloride transport increased by at least 10% of normal (wild-type chloride transport) compared to baseline [

21], as the threshold for CF diagnosis was less than 10 % CFTR wild-type activity [

22]. Based on this decision, the authorization for this pwCF group has also been extended in the UK.

As authorizations based on in vitro data are not permitted in the EU and the pwCF group with rare non-phe508del-CFTR mutations is too small for a pivotal trial, this extended ETI authorization was not possible in the EU. Recently, ETI has been prescribed off-label in Germany for pwCF with FDA-approved non-phe508del responsive CFTR mutations following a successful application to the health insurance funds. Apart from data on the French Compassionate Program published at the beginning of 2023 [

23] and a few individual case reports [

24,

25,

26], there are hardly any data worldwide and none in Germany on the treatment response of ETI in pwCF with non-phe508del CFTR mutations, even though some responsive CFTR mutations are included in the current study VX21-121-445, a phase 3 trial evaluating ETI effects in pwCF 6 years and older with non-phe508del CFTR mutations, with so far unpublished results.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This retrospective two-center, longitudinal study was considered as an evaluation of case reports. Since start of CFTR modulator therapy, the centers at Ulm University Hospital (UKU) and Munich Pasing Lung Clinic decided to include questionnaires as outlined below in our routine care. The data were collected at routine appointments in the period from February 2021 to February 2024. All pwCF in the two centers have three-monthly outpatient appointments. These appointments include pulmonary function testing, laboratory chemistry controls, a detailed medical history and clinical examination. Sweat chloride was measured before and at least three months after starting a new CFTR modulator. In addition, we used the following questionnaires: SNOT-22, CFQ-R and a self-designed Activity Questionnaire (AQ) as well as Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication (TSQM). No data deviating from the routine were collected. All data were retrospectively analyzed after the end of the survey period.

Six pwCF aged 6 to 66 years (3 female, 3 male) with at least one FDA-approved non-phe508del-CFTR mutation from the Cystic Fibrosis Outpatient Clinic at UKU and the Munich Pasing Lung Clinic were evaluated immediately before and 3/6/9/12 months (+/- 1) after start of ETI therapy. ETI was prescribed off-label in doses as recommended by the manufacturer after approval of reimbursement of costs by the health insurance companies. Four pwCF without ETI therapy with classic CF symptoms served as a control group. Exclusion criteria were organ transplants, acute infections, unstable pulmonary or cardiovascular diseases, pregnancy, recent pneumothorax (< 6 weeks), relevant hemoptysis (old blood > 5 ml or fresh blood more than traces < 4 weeks), pronounced liver disease (cirrhosis with portal hypertension, Child Pugh Score >7) and malignant disease.

Clinical parameters such as lung function, sweat test, BMI (percentiles in children) and laboratory chemistry values were observed. In addition, the development of ENT symptoms was analyzed using the SNOT-22 [

27], quality of life using the CFQ-R [

28] and medication satisfaction using the TSQM [

29]. Every day and physical performance were measured using an a self-designed AQ that contained individual elements of the BSA questionnaire for measuring physical activity and sport [

30]. The current number of minutes of walking and cycling without a break and the number of flights of stairs that can be climbed were asked. In addition, the average number of steps per day in the week of the outpatient appointment was asked if a pedometer including a smartphone that was able to count steps was available.

2.2. Data analysis and Statistics

All data sets were collected using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA 98052-6399, USA), the respective files were stored on a secure server, access- and password-restricted, based at Ulm University Hospital. Using descriptive statistics to describe the patient collectives, individual values, minima, maxima, medians and interquartile ranges were analyzed. Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism (Version 10.1.0., GraphPadSoftware, La Jolla, California, USA, ww.graphpad.com). Due to the small number of patients, only non-parametric tests were used. The significance level was set at p<0.05 in all analyses. The non-parametric Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank test was used to test for a significant difference in parameters between immediately before and at different times after the start of ETI therapy. The non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was used to test for a significant difference between the target group and the control group at the same point in time.

2.3. Ethics

The need for an ethics vote was waived by Ulm University Ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study, considered as evaluation of case reports (Chairman Florian Steger; no. 114/23, approved May 24, 2023) and conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients were informed about the study by their treating physicians and written information material. Opportunities to ask questions were given at any time. They were included in the study after providing written consent in the form of an informed consent form and a data protection declaration. None of the patients withdrew their consent at any point during the study.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort

The study included 6 pwCF (3 male, 3 female) aged 6 to 66 years who were carriers of at least one FDA-approved non-phe508del CFTR mutation with presumed responsive CFTR function, sometimes in combination with nonsense mutations. One patient had already received another CFTR modulator (Ivacaftor) before starting ETI therapy. Detailed demographic data for the intervention and control group can be found in

Table 1.

One patient who underwent ETI therapy had to be excluded after 6 months due to the occurrence of a second malignant disease and the associated fulfilment of the exclusion criteria. Further observed data on this patient undergoing ETI are highlighted in grey in the tables and graphs. 4 pwCF (3 female / 1 male) with classic symptoms without ETI therapy aged between 7 and 44 years (with the mutations Q39X, R785X, phe508del, I506S, CFTRdele17a,17b, CFTRdele14b-17b) served as a control group.

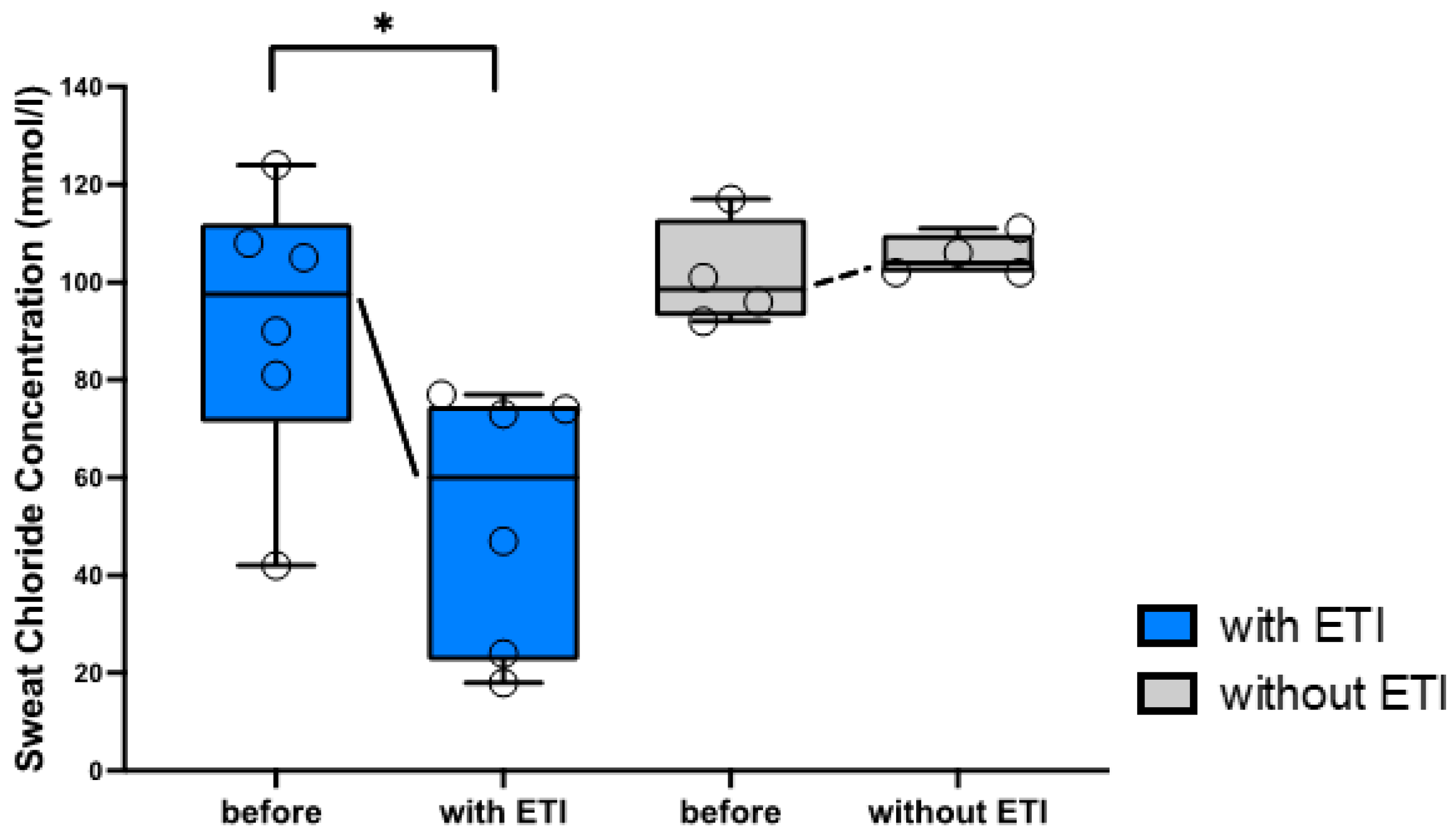

3.1. Clinical Parameters

After 1-3 months of ETI therapy, sweat chloride significantly fell in all pwCF taking ETI therapy by a median of 31.5 mmol/L (range: 24-66 mmol/L) (

Figure 1).

As can be seen in the detailed evaluation in

Suppl. Table S1, sweat chloride values dropped >30 (<60) mmol/L in three pwCF and even >60 mmol/L in two pwCF after 1-3 months undergoing ETI therapy, with four pwCF below 60 and two below 30 mmol/L absolute chloride levels. Only the patient treated with Ivacaftor before starting ETI therapy showed a decrease of only 24 mmol/L. Sweat tests from the control group were also available as part of an internal quality control of a study in 2023. The latter were compared with sweat test levels of the control group, carried out after birth at the time of diagnosis. Only minimal changes in median sweat chloride of +3.5 mmol/L ((-6) -14 mmol/L) were found in the control group over time.

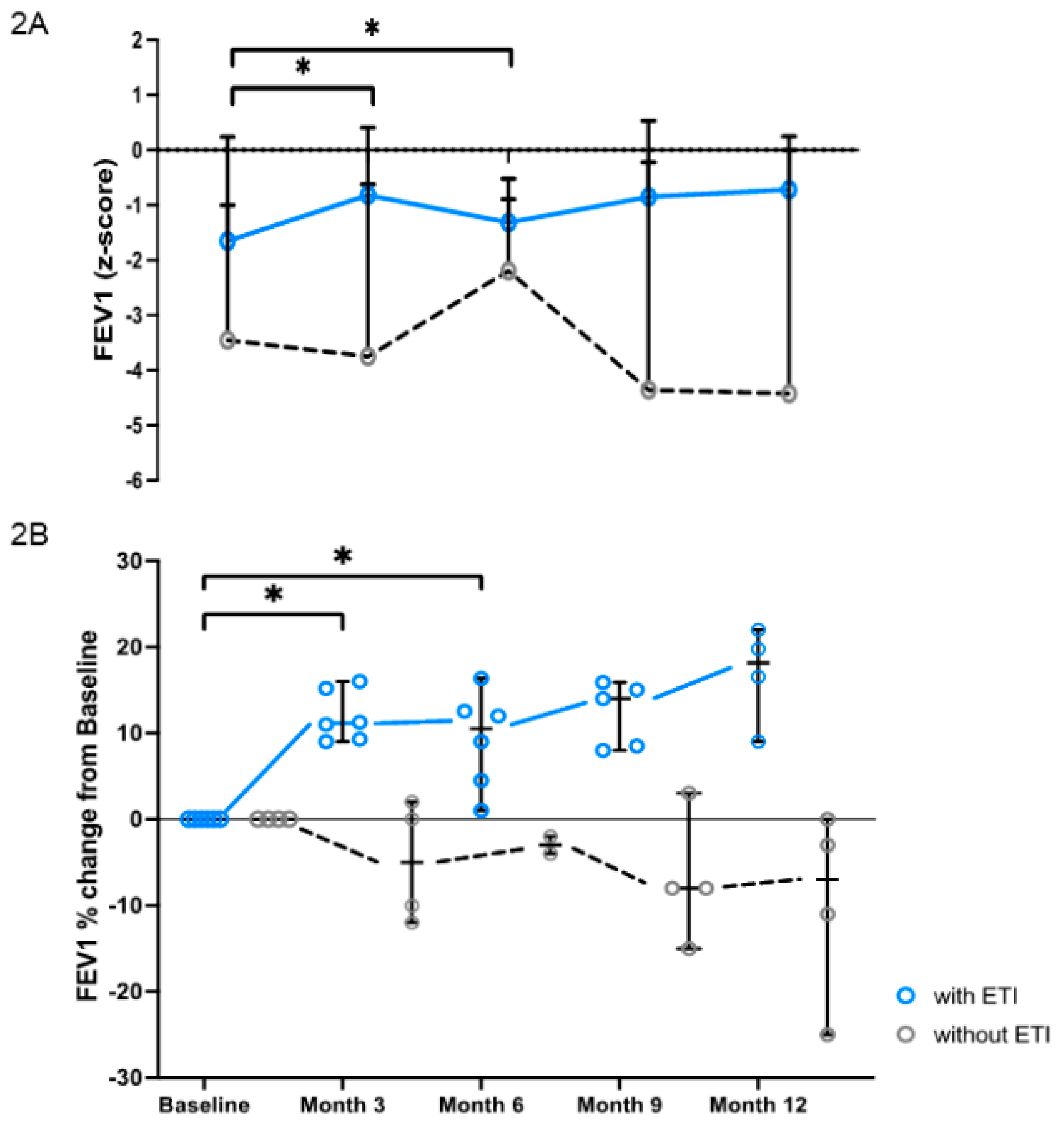

The FEV1 value continuously improved in all pwCF who took ETI therapy, as can be seen in

Figure 2. Significant increases were observed after 3 months (p=0,03) of ETI therapy by a median of 11 % (9-15 %) and after 6 months (p=0,03) of ETI therapy by 12 % (1-16 %) compared to baseline (

Figure 2A). At the timepoints 9 and 12 months ETI appears to further stabilize the FEV1 value, even though changes were not significant compared to baseline. Precisely, FEV1 was 14 % (8-16 %) higher than the baseline value after 9 months (p=0,06) of ETI and 18 % (9-22 %) higher after 12 months (p=0,13). In contrast, the FEV1 values of the control group by trend deteriorated over time, without significant changes compared to baseline. The median FEV1 value of the control group was -4 % (2-(-12) %) after 3 months, -3 % ((-2) -(-4) %) after 6 months, -8 % (3-(-15) %) after 9 months and -7 % (0-(-25) %) after 12 months compared to the baseline value. The different development can also be seen in the presentation of the z-scores (

Figure 2A).

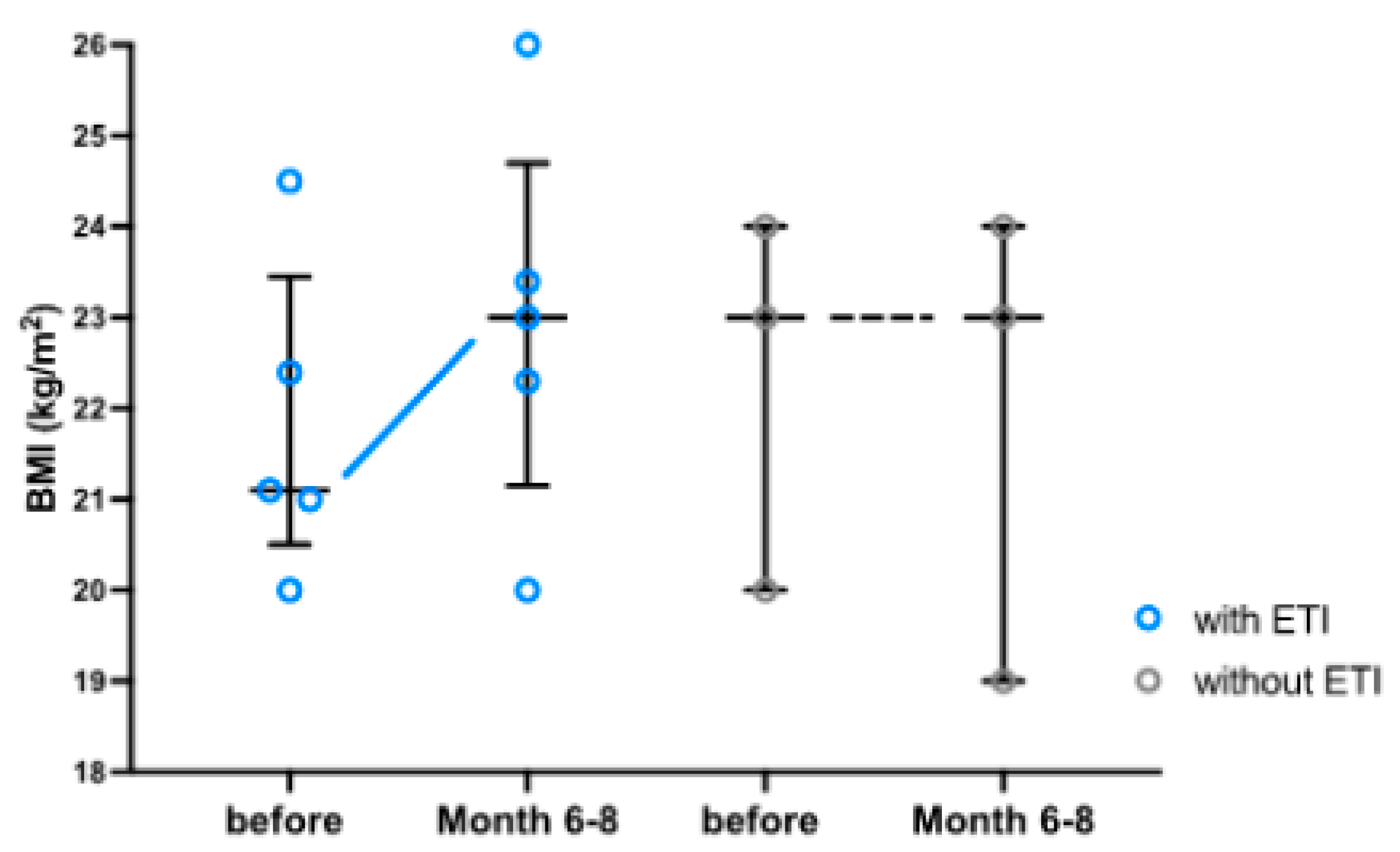

Since most BMI data are only available at month 0 and month 6-8 after the start of ETI therapy, as shown in

Suppl. Table S1, the analysis focuses on these two time points. In contrast to the untreated control group, almost all adult pwCF gained weight during ETI therapy (

Figure 3). Only the patient with the CFTR mutations R347P; R1066C remained constant in weight while taking ETI. A significant difference in the increase in weight/BMI with ETI was not observed. The CF child who started ETI gained weight only passingly during the observation period and remained almost constant at its percentiles after one year of observation. The CF child in the control group remained severely underweight during the observation period, while the BMI percentiles fell continuously.

There were temporary increases in total bilirubin under ETI therapy, but within reference values of 2-21 µmol/l for older children and adults (Clinical Chemistry at Ulm University Hospital) and lower than 2x ULN in the control (

Suppl. Table S1A), therefore without any clinical consequence. No adverse events such as rash, intolerance or psychological abnormalities occurred in the intervention group during ETI therapy.

3.2. Questionnaires

In the retrospective evaluation, apart from the time directly before the start of ETI therapy, almost only questionnaires from 6-8 months after the start of therapy were available. Therefore, the analysis of the questionnaires focused on these two time points: 0 months versus 6-8 months.

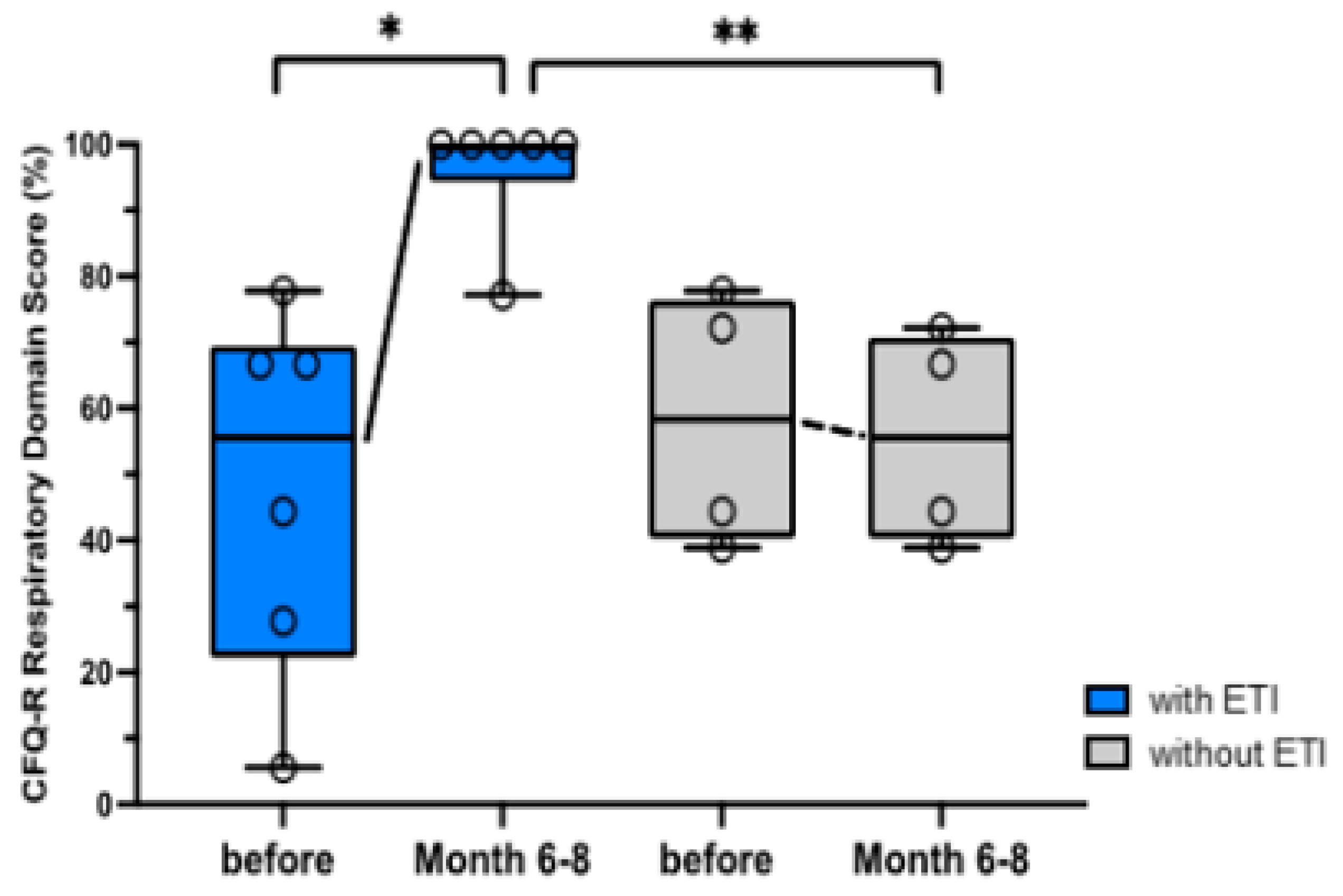

Respiratory symptoms in the respiratory domain (RD) of the CFQ-R (100 % best value) improved significantly by 33 % (22-67 %) after 6-8 months of ETI therapy compared to baseline. The median RD percentage of the control group fell from 58 % (39-78 %) to 56 % (39-72 %) over the same time period (

Figure 4). The difference after an observation period of 6-8 months between control and intervention group is also significant (p=0.005).

As shown in the Appendix, a more detailed analysis of all 12 CFQ-R domains showed significant (p<0.05) improvements in additional domains during ETI therapy, such as “Physical“, “Emotion”, “Treatment Burden” and “Health Perception” (

Suppl. Table S3).

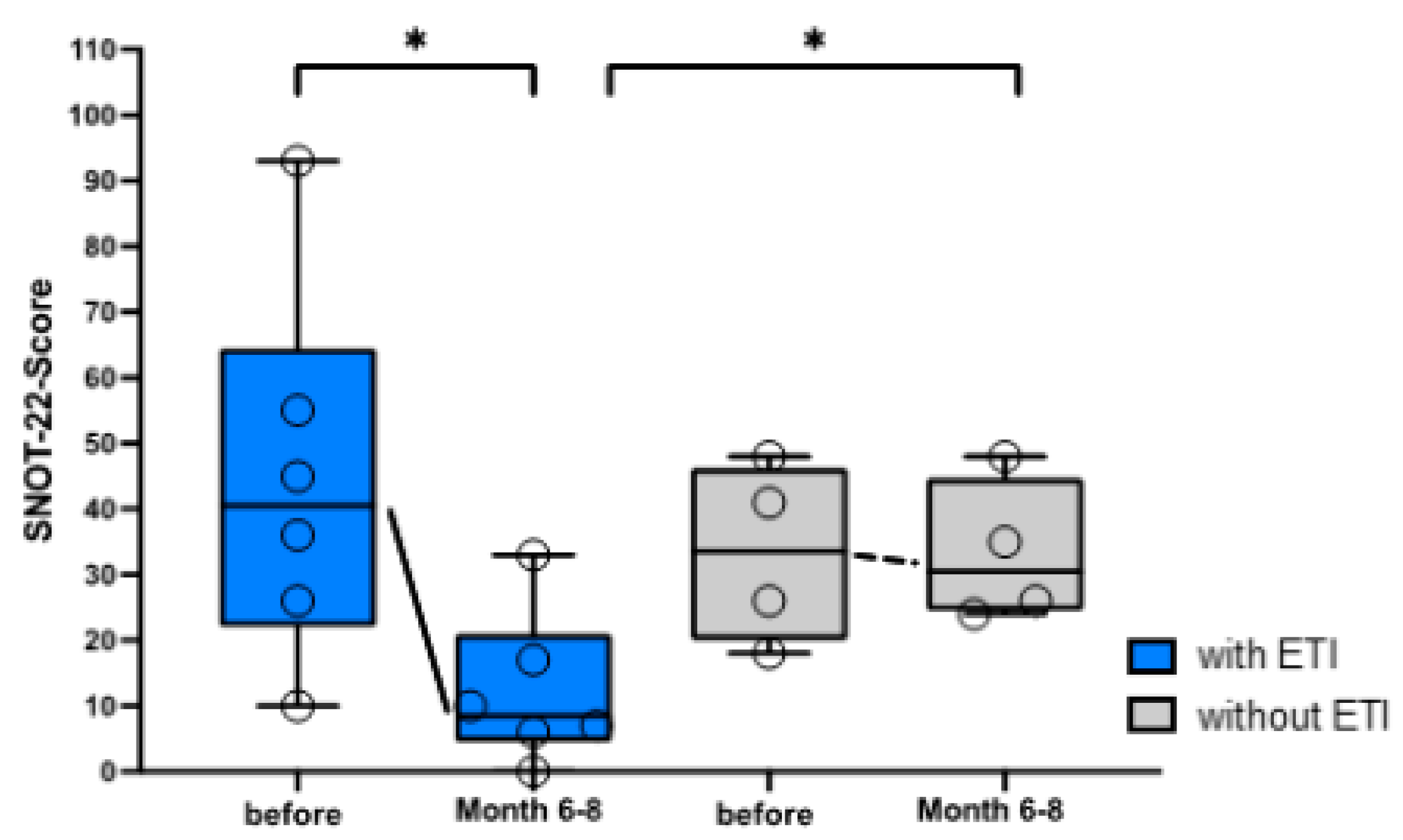

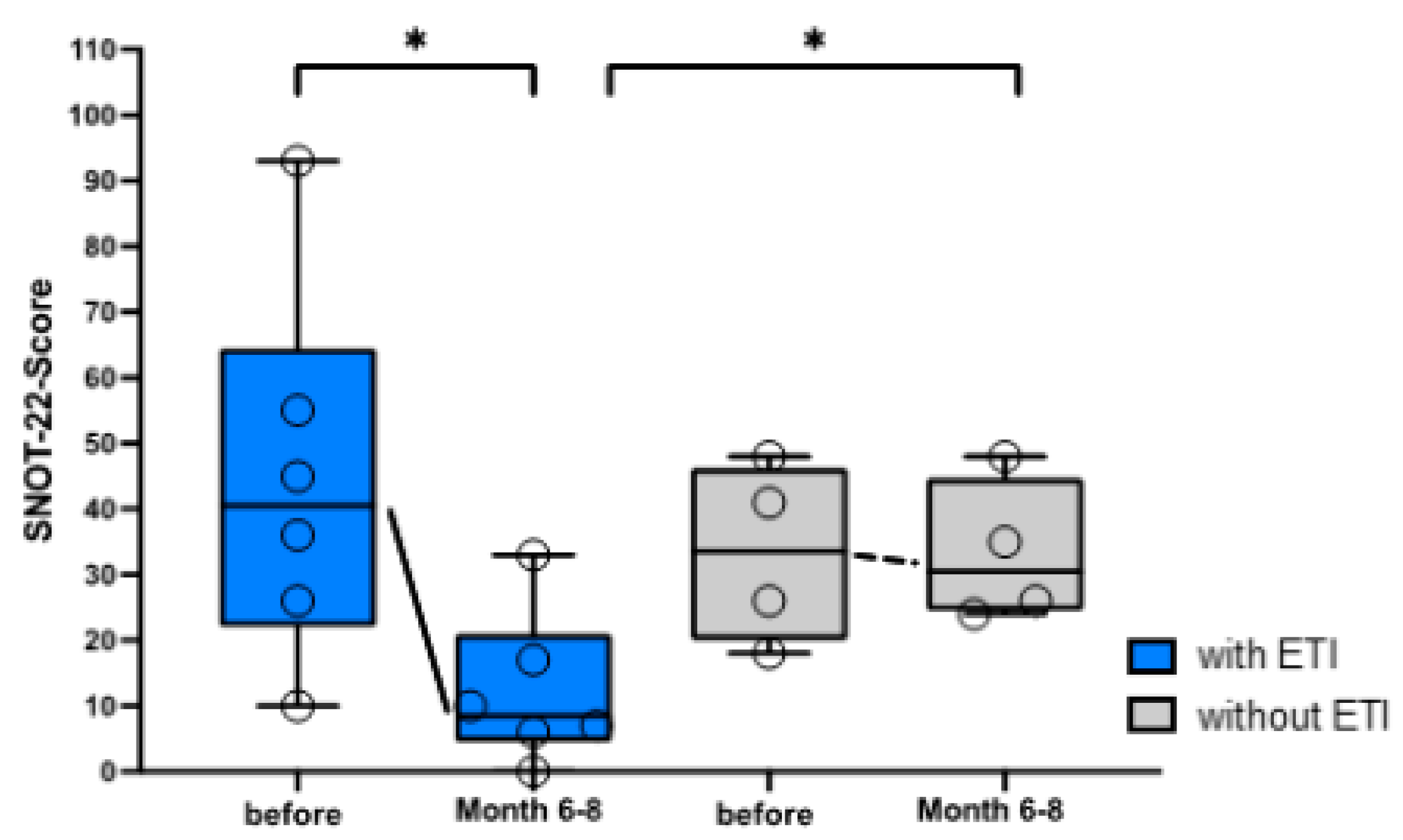

With ETI therapy, the ENT symptoms were significantly reduced compared to the control group and compared to the baseline value (

Figure 5). Since higher values in the SNOT-22 are associated with more severe ENT symptoms, reduced ENT-Symptoms meant a decrease in the SNOT score. The median SNOT score (worst value 110) fell in median from 40.5 (10-93) to 8.5 (0-33) after 6-8 months of ETI treatment. The control group started with an initial result of 33.5 (18-48) points in the SNOT score and deteriorated over the same time period to 43.5 (24-48) points.

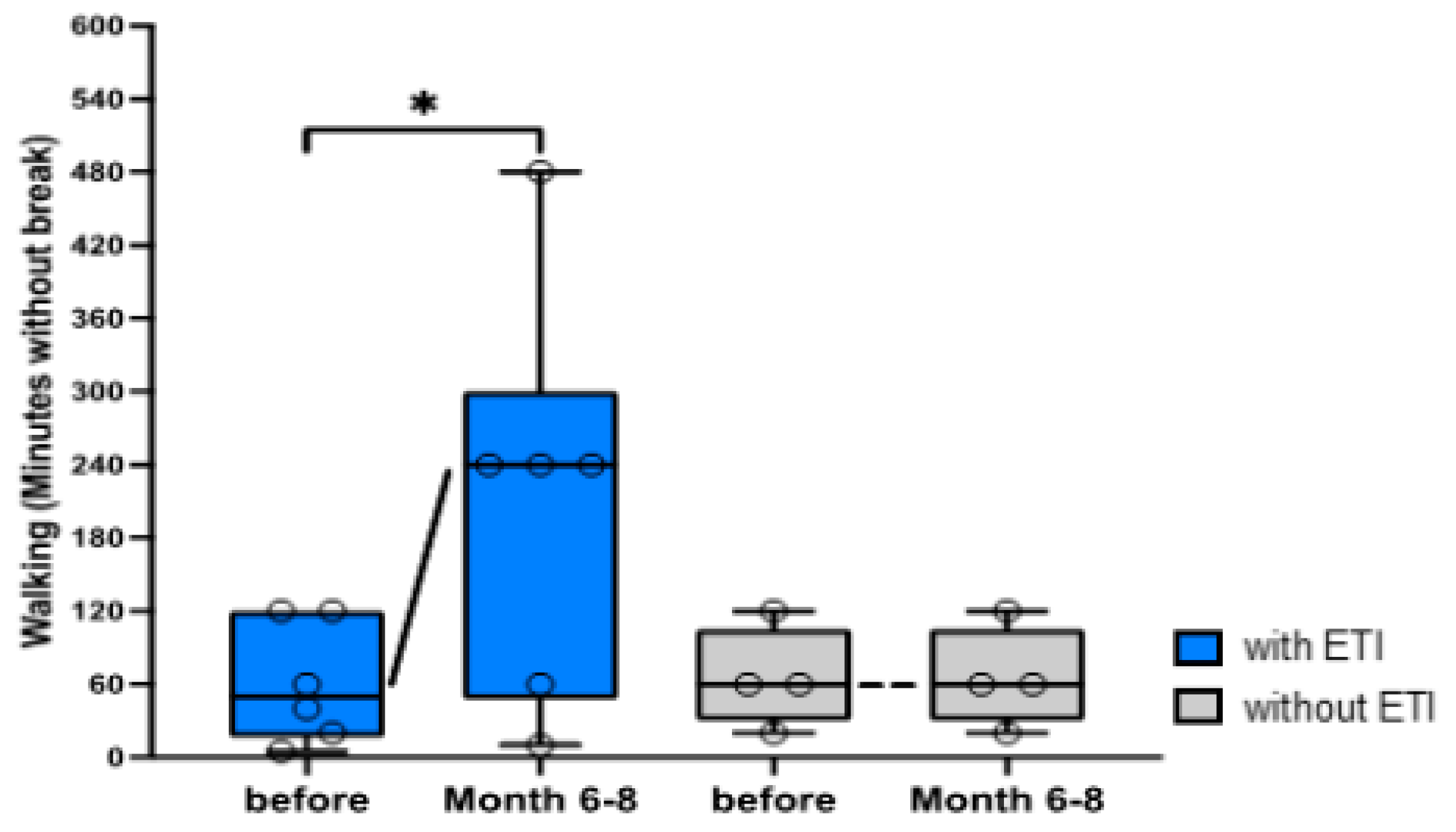

A significant increase in the number of minutes walked without a break was documented for a median of 150 minutes (5-360 min.) in all pwCF undergoing ETI therapy. In contrast, the physical performance measured by walking did not change at all in all pwCF in the control group after an observation period of 6-8 months (

Figure 6). Three pwCF of the intervention group had a pedometer and confirmed improved activity after 6-8 month on ETI with a median increase of 3744 steps (960-5000 steps) per day. In addition, we noted an increase in the number of minutes of cycling of 30 min. (0-60 min.) and an improvement in stair climbing with an increase of 2 floors (2-17 floors) in the pwCF after 6-8 months on ETI.

The evaluation of the TSQM revealed a consistent medication satisfaction of almost always 100 % in all 4 domains "Effectiveness", "Side effects", "Convenience" and "Global satisfaction", as can be seen in the detailed presentation of all data in the appendix (

Suppl. Table S2).

4. Discussion

This study evaluated the effectiveness of ETI in a small cohort of pwCF with rare non-phe508del responsive CFTR mutations. Site specific abilities were inclusion of ENT evaluation, Quality of life questionnaires and physical activity assessment, which are not routinely evaluated in CF centers. All measured parameters in our pwCF cohort undergoing ETI therapy changed in a comparable way to other ETI therapy studies, while the measured parameters of the control group showed hardly any changes. In addition, a long-term positive effect of ETI in the intervention group was confirmed over the observation period of more than one year, which is way longer than has been published so far for non-phe508del pwCF. Due to the lack of adverse events under ETI and the consistent satisfaction in the TSQM, we can assume good tolerability of ETI in our intervention group.

Burgel et al.[

23] published data in early 2023 on the effect of ETI on pwCF over 12 years of age with FDA-approved non-phe508del CFTR mutations. In an observation period of 4-6 weeks, a median decrease in sweat chloride of -36 mmol/l and a median increase in FEV1 of 12 % compared to baseline was documented. Likewise, ETI-treated pwCF in our cohort showed falling values of median sweat chloride values of -31.5 mmol/l and a rise of median FEV1 of 11 % already after 3 months. We not only confirmed the positive effect of ETI on non- phe508del mutations, but we also observed a stabilization of FEV1 over time, with a median FEV1 of 18 % in month 12 compared to baseline, which narrowly missed significance due to the dropout of one individual. In the French Compassionate Use Program, the subgroup of pwCF who had switched from Ivacaftor to ETI therapy no relevant changes in FEV1 and weight were measured, accompanied with only a slight drop in sweat chloride levels. In the one individual in our cohort, who switched from Ivacaftor monotherapy to ETI, we observed a mild FEV1 increase of 9%, a BMI increase from 14,5 to 25,8% and a sweat chloride drop of-22 mmol/l, even though this is just a single case report.

In comparison to ETI therapy studies of pwCF with at least one phe508del mutation, the clinical parameters developed similarly. The previously described 11-14 % increase in FEV1 and the increase in BMI of +1 kg/m² after 6 months of ETI therapy are consistent with our results. Sweat chloride decreases of 41-46 mmol/L after 6 months in individuals with CFTR phe508del mutations taking ETI are slightly higher than our values (31.5 mmol/L), probably due to our earlier measurement of sweat chloride after 1-3 months [

6,

8].

Although the following parameters have been used in many ETI studies of pwCF with at least one phe508del mutation, to our knowledge, this study was the first to analyze the group of pwCF with non-phe508del CFTR mutations under ETI using parameters such as the SNOT-22 score, the CFQ-R and the AQ. Therefore, we can only compare these data with ETI therapy studies of pwCF with at least one phe508del mutation. In the pivotal study of ETI [

6], for example, an increase in the RD of the CFQ-R of 20% after 6 months with ETI was noted. With our observed 33% increase in RD after 6-8 months, the presented cohort even exceed this data. In a more detailed analysis of the effect of ETI on the mental health of pwCF with at least one phe508del mutation from 2023[

18], significant improvements were observed in other CFQ-R domains such as "Physical", "Treatment Burden" and "Health Perception", as we did. The improved ENT symptoms under ETI in Bode et al[

15]. with the described 17-point SNOT score increase after 9 months is also confirmed in our study with an improvement by 28 points after 6-8 months. Data on the development of our analyzed physical activity parameters could not be found in any other ETI therapy studies, therefore comparison with current literature is difficult. Nevertheless, a few pilot studies using spiroergometry were able to prove that physical fitness improves under ETI, confirming our thesis [

31,

32].

It is important to mention that this study is the first to provide data on a child with CF under 12 years of age with a non-phe508del mutation who responded to ETI therapy in terms of parameters such as FEV1, sweat chloride and CFQ-R in the same way as other children with CF under 12 years of age with at least one phe508del mutation [

33].

The greatest strength of this study lies in the thorough analysis of pwCF with rare non-phe508del-CFTR variants, a subgroup for which hardly any data of ETI effects are available. It is noteworthy that our study was conducted over an observation period of 12 months, by far exceeding other published data [

23]. We not only evaluated both classical outcome parameters as lung function and BMI, but also ENT symptoms and everyday activity levels. Moreover, our study was carried out without industrial sponsoring, thereby delivering independent results. To our knowledge, our study is the first reporting on changes in ENT symptoms and activity under ETI therapy in pwCF with non-phe508del-CFTR mutations. Although non-phe508del mutations are rare, we were able to evaluate a cohort that represented both female/male sexes in equal proportions. The fact that there was one child in each of the control and ETI groups was also very helpful for comparability. In addition, to our knowledge, no data on the clinical course in children with CF under the age of 12 years with a non-phe508del CFTR mutation have yet been evaluated and published under ETI. Four of ETI- treated pwCF in our cohort have the CFTR mutation M1101K, initially defined as minimal function mutation, because of < 10% wild type chloride transport in FRT cells in vitro and further defined by the observation that effects of Ivacaftor alone or Ivacaftor/Tezacaftor did not reach at least 10% increase of CFTR wild type function compared to baseline [

6] unpublished in vitro observations by the ETI- producing company). However, M1101K was included in the list of eligible mutations for ETI triple treatment because ETI increased chloride transport by at least 10% of normal (wild-type chloride transport) compared to baseline. These unpublished in vitro results led to extension of FDA approval in the US and UK in 2020, but not yet in Europe due to the lack of in vivo data [

20].

The major limitation of the study is primarily the small number of participants, which was unavoidable due to the low incidence of non-phe508del-CFTR variants. Due to the fact that most pwCF now have access to ETI, the control group was also very small. All statistical statements must therefore be treated with caution and cannot be applied to the overall population of pwCF. However, together with other case reports on the tolerability of ETI in non-phe508del-CFTR mutations, this study supports the evidence that ETI is effective and safe in selected individuals with non phe508del CFTR mutations. Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

5. Conclusions

Our study showed an almost identical effect of ETI in pwCF with at least one phe508del mutation as on pwCF with FDA-approved non-phe508del CFTR mutations. Furthermore, this effect was confirmed over an observation period of one year and positive effects of ETI therapy in not yet measured parameters such as ENT symptoms, quality of life and physical activity were also observed. In conclusion, based on our results and comparable studies, it is worthwhile to sincerely consider expanding the ETI approval in the EU to include the rarer FDA-approved non-phe508del CFTR mutations, for which the number pwCF will always be limited.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Table S1: Detailed evaluation of the clinical data; Table S2: Detailed evaluation of the questionnaires; Table S3: Detailed CFQ-R Evaluation.

Author Contributions

TS and DF: conceptualization, methodology, supervision and writing—original draft preparation. TS: investigation, data curation, visualization. SFNB, PF, DF: patient treatment, resources. All authors: writing—reviewing and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The need for an ethics vote was waived by Ulm University Ethics committee due to the retrospective nature of the study, considered as evaluation of case reports (Chairman Florian Steger; no. 114/23, approved May 24, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author and yet are not openly available due to ongoing analysis and observation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the whole team of the CF outpatient clinic, Ulm University and the Cystic Fibrosis Center Munich West, Ludwig Maximilian University for support during the study. We are thankful to all participants.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guo, J.; Garratt, A.; Hill, A. Worldwide rates of diagnosis and effective treatment for cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2022, 21, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shteinberg, M.; Haq, I.J.; Polineni, D.; Davies, J.C. Cystic fibrosis. Lancet 2021, 397, 2195–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nährlich, L.; Burkhart, M.; Wosniok, J. German Cystic Fibrosis Registry Annual Report 2022. Available online: https://www.muko.info/fileadmin/user_upload/was_wir_tun/register/berichtsbaende/annual_report_2022.pdf (accessed on 8 Jul 2024).

- Lord, L.; McKernon, D.; Grzeskowiak, L.; Kirsa, S.; Ilomaki, J. Depression and anxiety prevalence in people with cystic fibrosis and their caregivers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2023, 58, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veit, G.; Roldan, A.; Hancock, M.A.; da Fonte, D.F.; Xu, H.; Hussein, M. , et al. Allosteric folding correction of F508del and rare CFTR mutants by elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor (Trikafta) combination. JCI Insight 2020, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middleton, P.G.; Mall, M.A.; Dřevínek, P.; Lands, L.C.; McKone, E.F.; Polineni, D. , et al. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor for Cystic Fibrosis with a Single Phe508del Allele. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heijerman, H.G.M.; McKone, E.F.; Downey, D.G.; Van Braeckel, E.; Rowe, S.M.; Tullis, E. , et al. Efficacy and safety of the elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor combination regimen in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for the F508del mutation: a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019, 394, 1940–1948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sutharsan, S.; McKone, E.F.; Downey, D.G.; Duckers, J.; MacGregor, G.; Tullis, E. , et al. Efficacy and safety of elexacaftor plus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor versus tezacaftor plus ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis homozygous for F508del-CFTR: a 24-week, multicentre, randomised, double-blind, active-controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022, 10, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nährlich, L.; Burkhart, M.; Wosniok, J. German Cystic Fibrosis Registry Annual Report 2019. Available online: https://www.muko.info/fileadmin/user_upload/was_wir_tun/register/berichtsbaende/annual_report_2019.pdf (accessed on 20 Sep 2024).

- Gruber, W.; Stehling, F.; Blosch, C.; Dillenhoefer, S.; Olivier, M.; Brinkmann, F. , et al. Longitudinal changes in habitual physical activity in adult people with cystic fibrosis in the presence or absence of treatment with elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor. Front Sports Act Living 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMango, E.; Overdevest, J.; Keating, C.; Francis, S.F.; Dansky, D.; Gudis, D. Effect of highly effective modulator treatment on sinonasal symptoms in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2021, 20, 460–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.E.; Civantos, A.M.; Locke, T.B.; Sweis, A.M.; Hadjiliadis, D.; Hong, G. , et al. Impact of novel CFTR modulator on sinonasal quality of life in adult patients with cystic fibrosis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2021, 11, 201–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, S.; Echevarria, C.; Doe, S.; Brodlie, M.; Ward, C.; Bourke, S.J. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor improve Gastro-Oesophageal reflux and Sinonasal symptoms in advanced cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2022, 21, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beswick, D.M.; Humphries, S.M.; Balkissoon, C.D.; Strand, M.; Vladar, E.K.; Lynch, D.A. , et al. Impact of Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator Therapy on Chronic Rhinosinusitis and Health Status: Deep Learning CT Analysis and Patient-reported Outcomes. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2022, 19, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bode, S.F.N.; Rapp, H.; Lienert, N.; Appel, H.; Fabricius, D. Effects of CFTR-modulator triple therapy on sinunasal symptoms in children and adults with cystic fibrosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2023. [CrossRef]

- Arslan, M.; Chalmers, S.; Rentfrow, K.; Olson, J.M.; Dean, V.; Wylam, M.E. , et al. Suicide attempts in adolescents with cystic fibrosis on Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor therapy. J Cyst Fibros 2023, 22, 427–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathgate, C.J.; Muther, E.; Georgiopoulos, A.M.; Smith, B.; Tillman, L.; Graziano, S. , et al. Positive and negative impacts of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor: Healthcare providers’ observations across US centers. Pediatr Pulmonol 2023, 58, 2469–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piehler, L.; Thalemann, R.; Lehmann, C.; Thee, S.; Röhmel, J.; Syunyaeva, Z. , et al. Effects of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor therapy on mental health of patients with cystic fibrosis. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramsey, B.; Correll, C.U.; DeMaso, D.R.; McKone, E.; Tullis, E.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L. , et al. Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor Treatment and Depression-related Events. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2024, 209, 299–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration. HIGHLIGHTS OF PRESCRIBING INFORMATION; Available online:. Available online: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2021/212273s004lbl.pdf (accessed on 16 Aug 2024).

- Durmowicz, A.G.; Lim, R.; Rogers, H.; Rosebraugh, C.J.; Chowdhury, B.A. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Experience with Ivacaftor in Cystic Fibrosis. Establishing Efficacy Using In Vitro Data in Lieu of a Clinical Trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2018, 15, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosnay, P.R.; Siklosi, K.R.; Van Goor, F.; Kaniecki, K.; Yu, H.; Sharma, N. , et al. Defining the disease liability of variants in the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene. Nat Genet [Internet]. 2023, 45, pp. 1160–1167. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23974870/.

- Burgel, P.R.; Sermet-Gaudelus, I.; Durieu, I.; Kanaan, R.; Macey, J.; Grenet, D. , et al. The French Compassionate Program of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor in people with cystic fibrosis with advanced lung disease and no F508del CFTR variant. European Respiratory Journal 2024, 2202437. [Google Scholar]

- Livnat, G.; Dagan, A.; Heching, M.; Shmueli, E.; Prais, D.; Yaacoby-Bianu, K. , et al. Treatment effects of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in people with CF carrying non-F508del mutations. J Cyst Fibros 2023, 22, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, W.M.; Davoodi, P.M.; Langevin, A.; Smith, C.; Parkins, M.D. Elexacaftor-Tezacaftor-Ivacaftor in 2 cystic fibrosis adults homozygous for M1101K with end-stage lung disease. Respir Med Case Rep 2023, 46, 101938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, M.O.; Santos, A.S.; Castanhinha, S. Efficacy of elexacaftor-tezacaftor-ivacaftor in portuguese adolescents and adults with cystic fibrosis carrying non-F508del variants. Pulmonology 2024. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, T.; Beule, A.G.; Hildenbrand, T.; Gerstacker, K.; Praetorius, M.; Rudack, C. , et al. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the 22-item sinonasal outcome test (SNOT-22) in German-speaking patients: a prospective, multicenter cohort study. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2022, 279, 2433–2439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henry, B.; Aussage, P.; Grosskopf, C.; Goehrs, J. Development of the Cystic Fibrosis Questionnaire (CFQ) for assessing quality of life in pediatric and adult patients. Qual Life Res 2003, 12, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnault, A.; Balp, M.M.; Kulich, K.; Viala-Danten, M. Validation of the Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire for Medication in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros 2012, 11, 494–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, R.; Klaperski, S.; Gerber, M.; Seelig, H. Messung der Bewegungs- und Sportaktivität mit dem BSA-Fragebogen. Eur J Health Psychol 2015, 23, 60–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Causer, A.J.; Shute, J.K.; Cummings, M.H.; Shepherd, A.I.; Wallbanks, S.R.; Pulsford, R.M. , et al. Elexacaftor–Tezacaftor–Ivacaftor improves exercise capacity in adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol 2022, 57, 2652–2658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stastna, N.; Hrabovska, L.; Homolka, P.; Homola, L.; Svoboda, M.; Brat, K. , et al. The long-term effect of elexacaftor/tezacaftor/ivacaftor on cardiorespiratory fitness in adolescent patients with cystic fibrosis: a pilot observational study. BMC Pulm Med 2024, 24, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zemanick, E.T.; Taylor-Cousar, J.L.; Davies, J.; Gibson, R.L.; Mall, M.A.; McKone, E.F. , et al. A Phase 3 Open-Label Study of Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor in Children 6 through 11 Years of Age with Cystic Fibrosis and at Least One F508del Allele. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2021, 203, 1522–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Significant decrease in sweat chloride concentration of people with CF undergoing ETI therapy. Sweat chloride levels (mmol/l) are shown as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Sweat chloride of pwCF under ETI therapy (n=6) is documented directly before and 1-3 months after ETI therapy compared to sweat chloride of the pwCF control group without ETI (n=4) at birth and in 2023. Using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test significant values were assessed by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CF= Cystic Fibrosis, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 1.

Significant decrease in sweat chloride concentration of people with CF undergoing ETI therapy. Sweat chloride levels (mmol/l) are shown as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Sweat chloride of pwCF under ETI therapy (n=6) is documented directly before and 1-3 months after ETI therapy compared to sweat chloride of the pwCF control group without ETI (n=4) at birth and in 2023. Using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test significant values were assessed by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CF= Cystic Fibrosis, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 2.

Improvement in FEV1 of people with CF under ETI therapy. FEV1 of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy (n=6) directly before and 3/6/9/12 months after ETI therapy compared to the FEV1 of the pwCF control group without ETI (n=4). Using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test significant values were evaluated, with p<0.05. 2A: FEV1 z-score values are shown as medians with minima and maxima. 2B: Percent predicted FEV1 values are demonstrated as percentage difference from baseline (month 0, directly before starting ETI therapy). Differences are outlined as individual single values, medians with minima and maxima. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CF= Cystic Fibrosis, FEV1= Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 2.

Improvement in FEV1 of people with CF under ETI therapy. FEV1 of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy (n=6) directly before and 3/6/9/12 months after ETI therapy compared to the FEV1 of the pwCF control group without ETI (n=4). Using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test significant values were evaluated, with p<0.05. 2A: FEV1 z-score values are shown as medians with minima and maxima. 2B: Percent predicted FEV1 values are demonstrated as percentage difference from baseline (month 0, directly before starting ETI therapy). Differences are outlined as individual single values, medians with minima and maxima. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CF= Cystic Fibrosis, FEV1= Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 Second, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 3.

BMI of adult pwCF undergoing ETI therapy. BMI values are depicted as individual values and whisker plots with medians and interquartile range. BMI values of adult pwCF under ETI therapy (n=5) are shown directly before and 6-8 months after ETI therapy compared to the pwCF control group without ETI (n=3). Abbreviations: ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, BMI= Body-Mass-Index, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 3.

BMI of adult pwCF undergoing ETI therapy. BMI values are depicted as individual values and whisker plots with medians and interquartile range. BMI values of adult pwCF under ETI therapy (n=5) are shown directly before and 6-8 months after ETI therapy compared to the pwCF control group without ETI (n=3). Abbreviations: ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, BMI= Body-Mass-Index, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 4.

CFQ-R RD results (%) are presented as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant improvement in respiratory symptoms of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy compared to baseline (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test) and to the control group (using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test) after 6-8 months. CFQ-R RD results of pwCF under ETI (n=6) are demonstrated immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, **=p<0.005, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CFQ-R RD= Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Respiratory Domain, pwCF=people with CF.

Figure 4.

CFQ-R RD results (%) are presented as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant improvement in respiratory symptoms of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy compared to baseline (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test) and to the control group (using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test) after 6-8 months. CFQ-R RD results of pwCF under ETI (n=6) are demonstrated immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, **=p<0.005, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, CFQ-R RD= Cystic Fibrosis Quality of Life Respiratory Domain, pwCF=people with CF.

Figure 5.

Significant decrease in ENT symptoms of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy compared to baseline (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test) could be seen, as well as compared to the control group (using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test) at 6-8 months. SNOT-22 scores of pwCF under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4), presented as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Figure 6: Significant improvement in physical performance of pwCF under ETI therapy compared to baseline after 6-8 months (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test). Walking minutes under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Number of minutes are demonstrated as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant values were defined by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, ENT= Ear, Nose and Throat, SNOT-22= Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 5.

Significant decrease in ENT symptoms of pwCF undergoing ETI therapy compared to baseline (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test) could be seen, as well as compared to the control group (using the Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test) at 6-8 months. SNOT-22 scores of pwCF under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4), presented as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Figure 6: Significant improvement in physical performance of pwCF under ETI therapy compared to baseline after 6-8 months (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test). Walking minutes under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Number of minutes are demonstrated as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant values were defined by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, ENT= Ear, Nose and Throat, SNOT-22= Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 6.

Significant improvement in physical performance of pwCF under ETI therapy compared to baseline after 6-8 months (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test). Walking minutes under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Number of minutes are demonstrated as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant values were defined by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, pwCF=people with CF

Figure 6.

Significant improvement in physical performance of pwCF under ETI therapy compared to baseline after 6-8 months (using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank-test). Walking minutes under ETI (n=6) are shown immediately before and 6-8 months after the start of ETI therapy compared to the control group (n=4). Number of minutes are demonstrated as individual values and box-whisker plots with medians, interquartile range, minima and maxima. Significant values were defined by p<0.05. Abbreviations: *=p<0.05, ETI= Elexacaftor/Tezacaftor/Ivacaftor, pwCF=people with CF

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the intervention group (patient 1-6) and the control group (patient A-D) including age, gender, CFTR mutations and CFTR modulator pre-medication are summarized.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the intervention group (patient 1-6) and the control group (patient A-D) including age, gender, CFTR mutations and CFTR modulator pre-medication are summarized.

| Patient |

Age (y) |

Gender |

CFTR-Mutation 1 |

CFTR-Mutation 2 |

ETI |

Ivacaftor before ETI |

| 1 |

45 |

f |

R347P* |

R1066C |

Yes |

No |

| 2 |

6 |

m |

Q220X |

M1101K* |

Yes |

No |

| 3 |

66 |

f |

M1101K* |

2789+5G>A |

Yes |

No |

| 4 |

35 |

m |

G542X |

M1101K* |

Yes |

No |

| 5 |

45 |

m |

CFTRdele2,3 |

M1101K* |

Yes |

No |

| 6 |

29 |

f |

G551D* |

M1101K* |

Yes |

Yes |

| A |

22 |

f |

Q39X |

CFTRdele17a,17b |

No |

No |

| B |

7 |

m |

Q39X |

R785X |

No |

No |

| C |

46 |

f |

phe508del* |

phe508del* |

No |

No |

| D |

23 |

f |

I506S |

CFTRdele14b-17b |

No |

No |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).