Submitted:

19 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

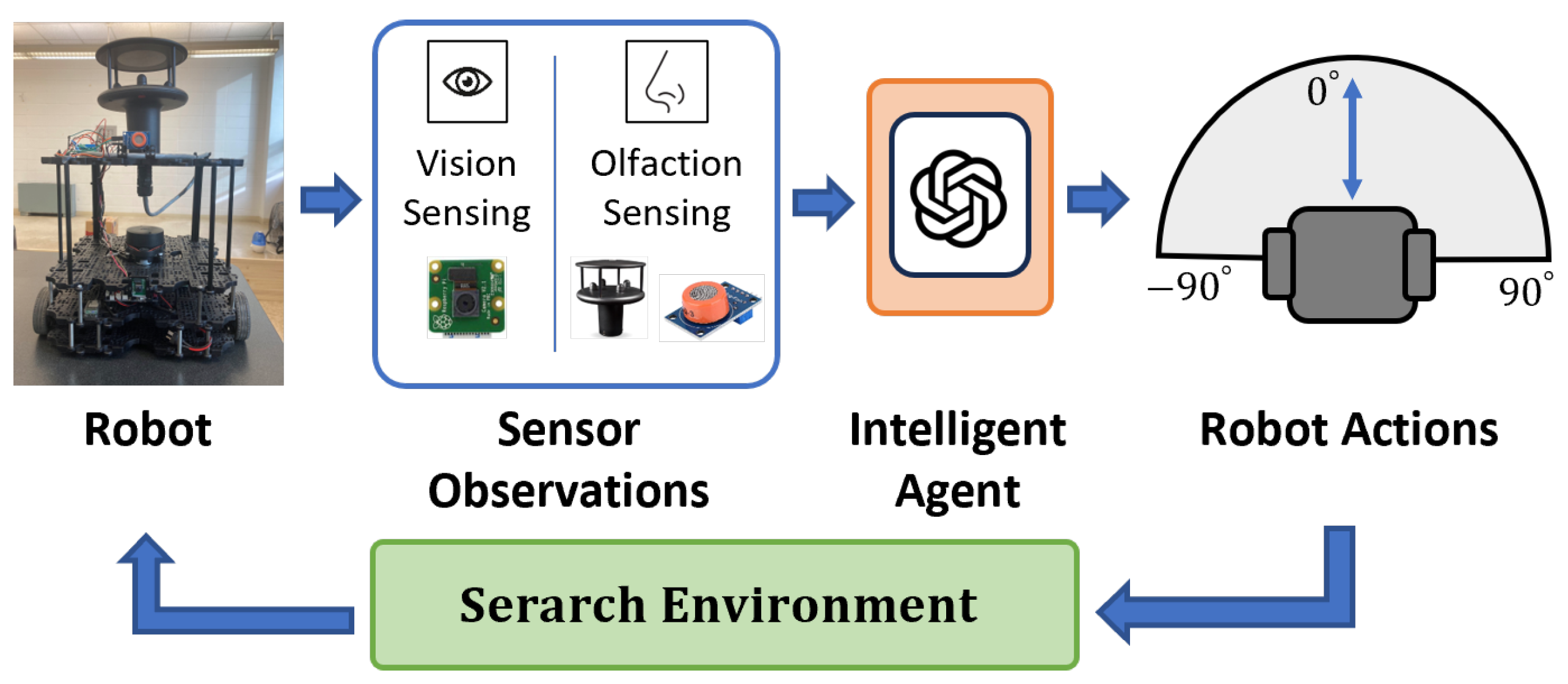

1. Introduction

- Integrating vision and olfaction sensing to localize odor source in complex real-world environments.

- Developing an OSL navigation algorithm that utilizes zero-shot multi-modal reasoning capability of multi-modal LLMs for OSL. This includes designing modules to process inputs to and outputs from the LLM model.

- Implementing the proposed intelligent agent in real-world experiments and comparing its search performance with the supervised learning-based vision and olfaction fusion navigation algorithm [25].

2. Related Works

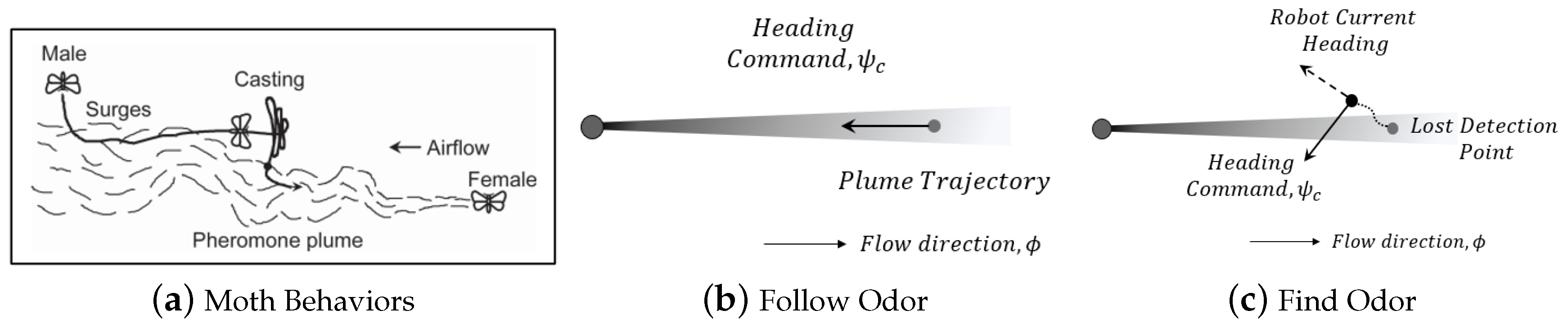

2.1. Olfaction-Only Methods

2.2. Vision and Olfaction Integration in OSL

2.3. LLM in Robotics

2.4. Research Niche

3. Methodology

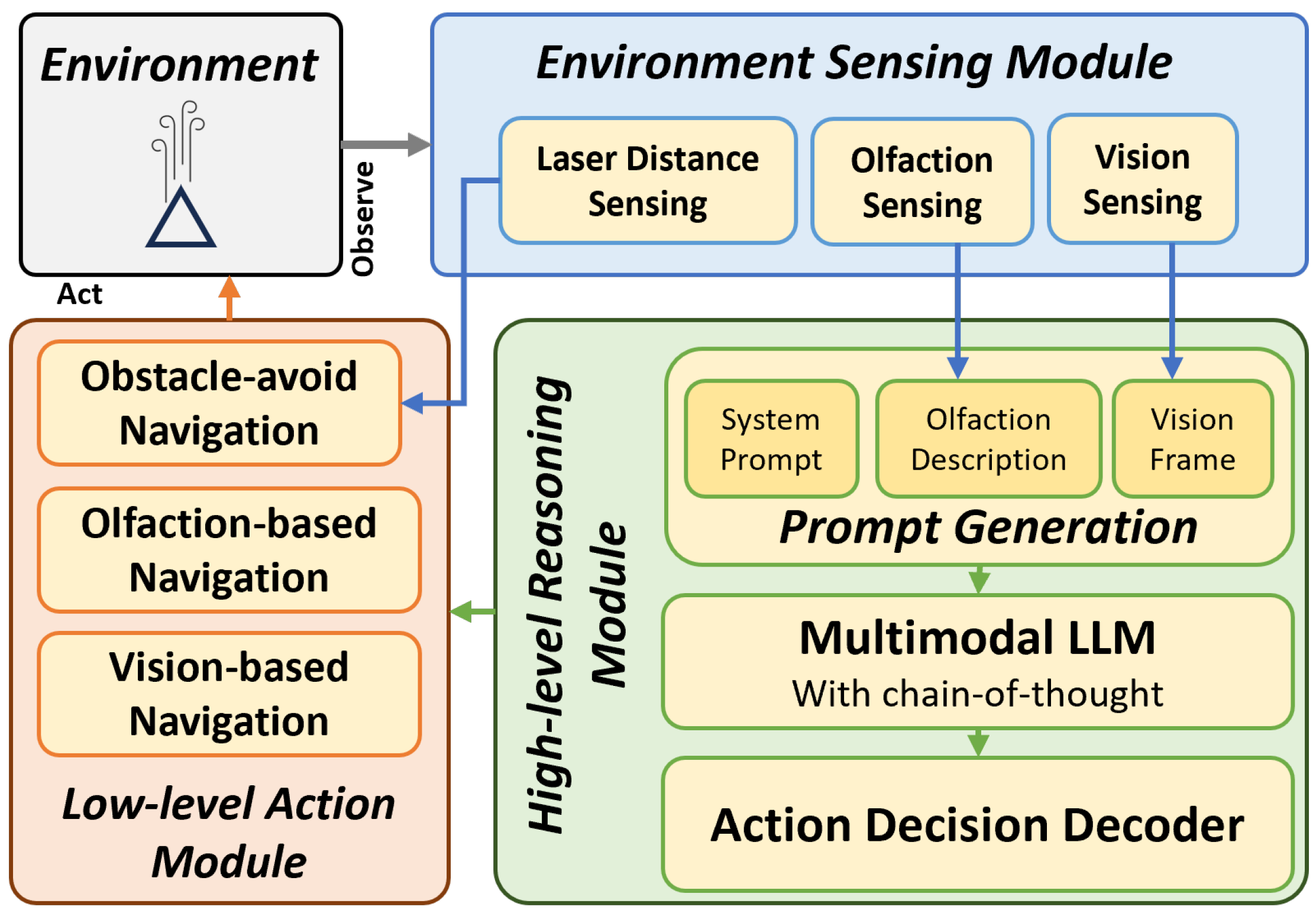

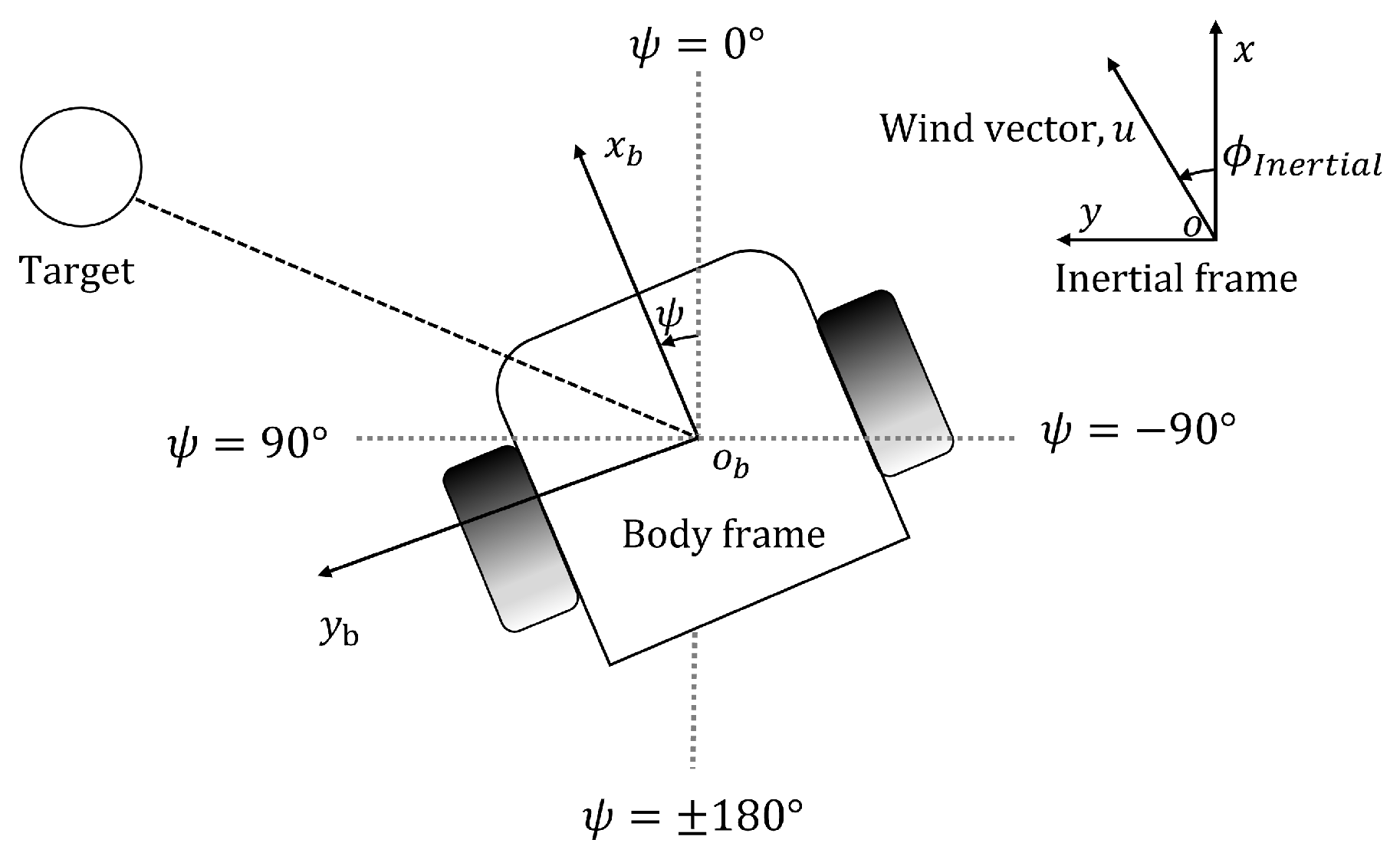

3.1. Problem Statement

3.2. Environment Sensing Module

3.3. High-level Reasoning Module

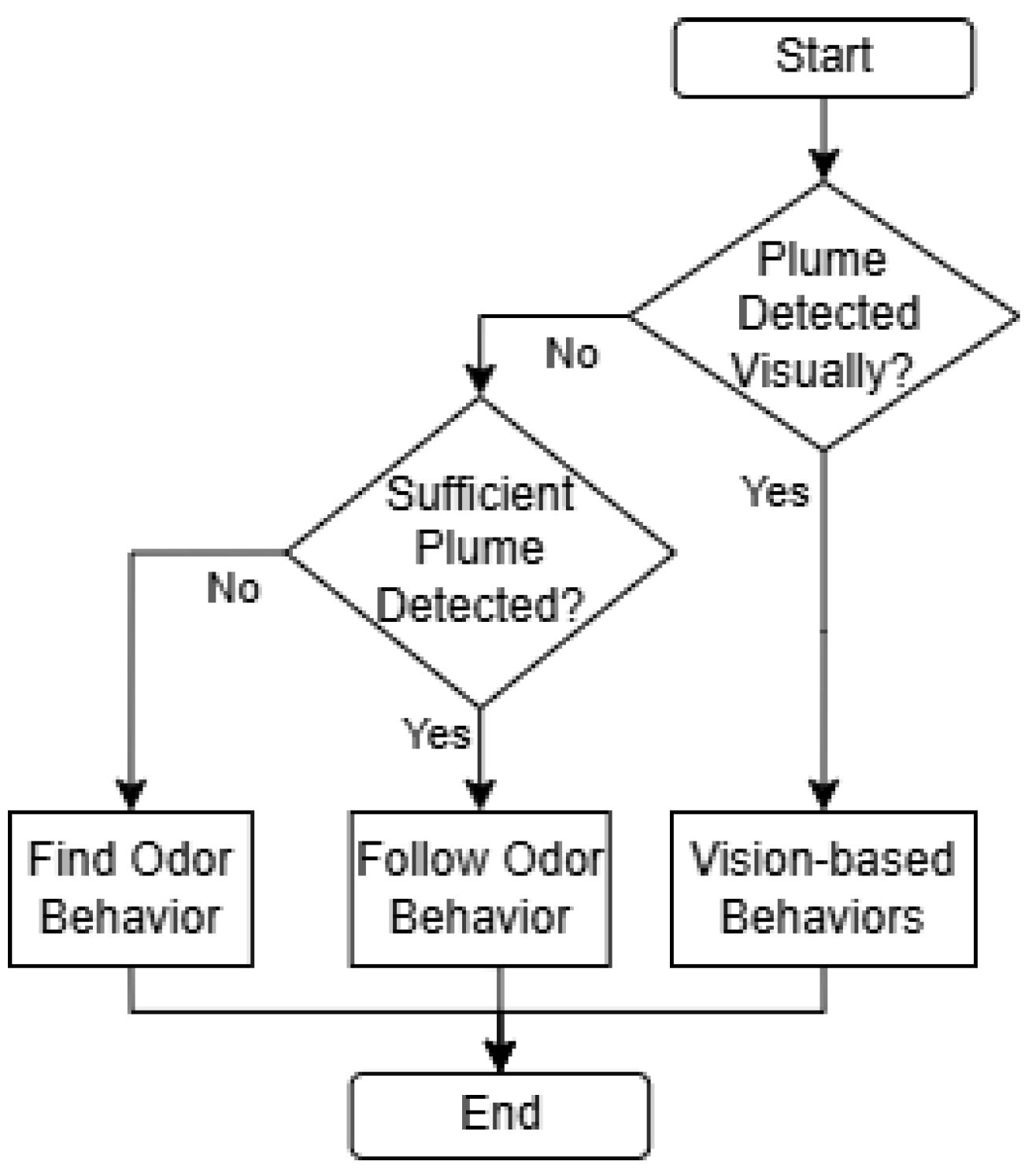

3.4. Low-level Action Module

4. Experiment

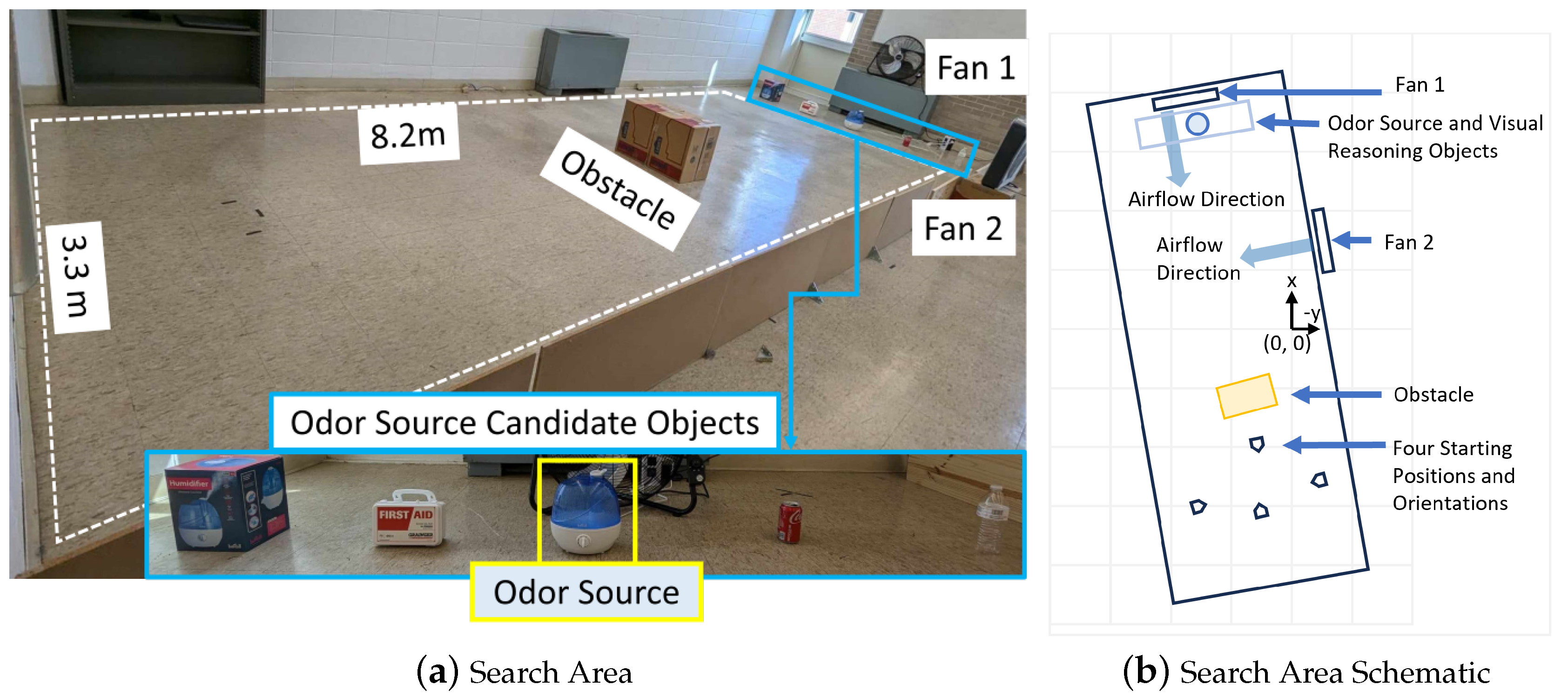

4.1. Experiment Setup

4.2. Comparison Algorithms

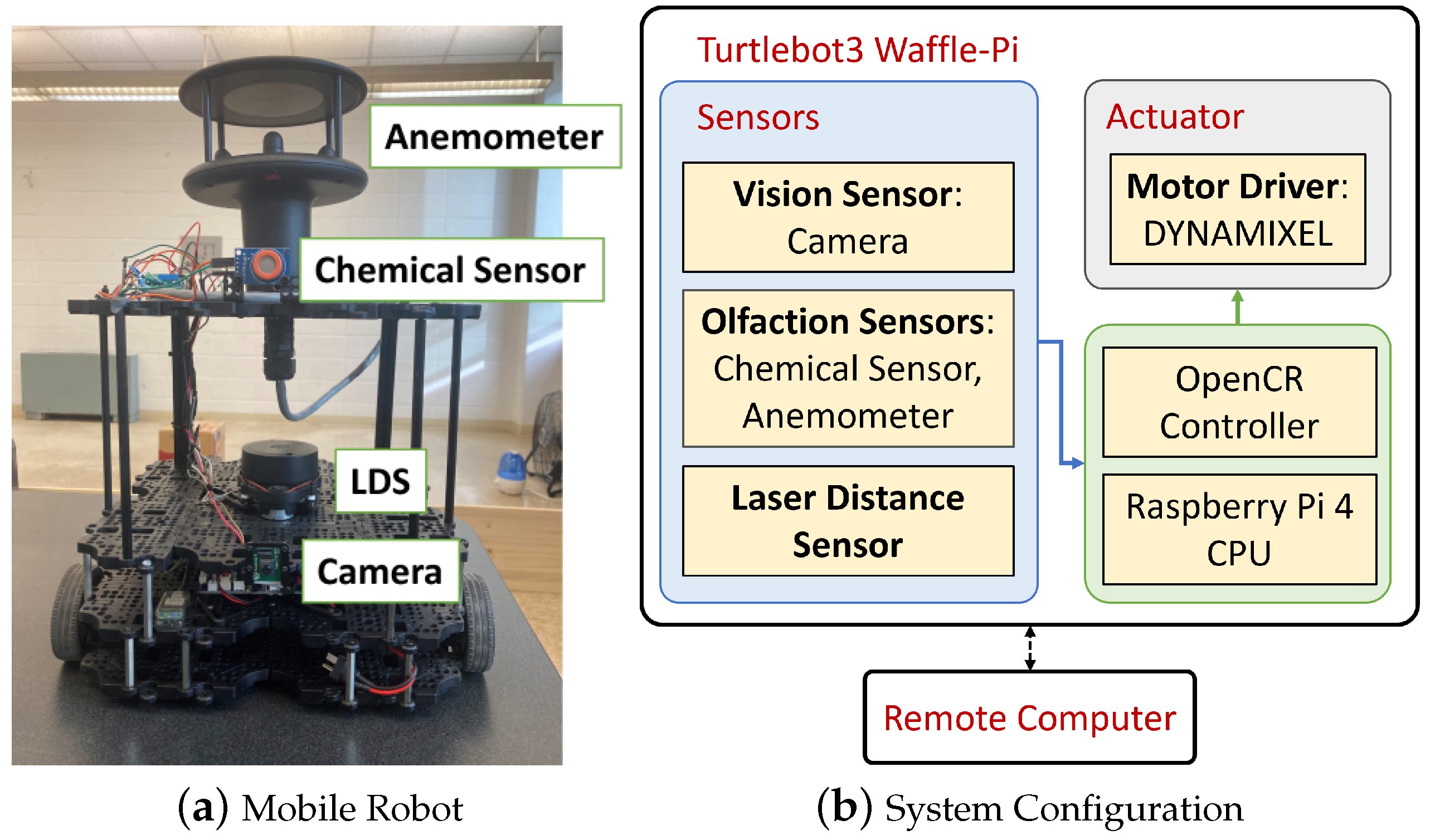

4.3. Robot Platform

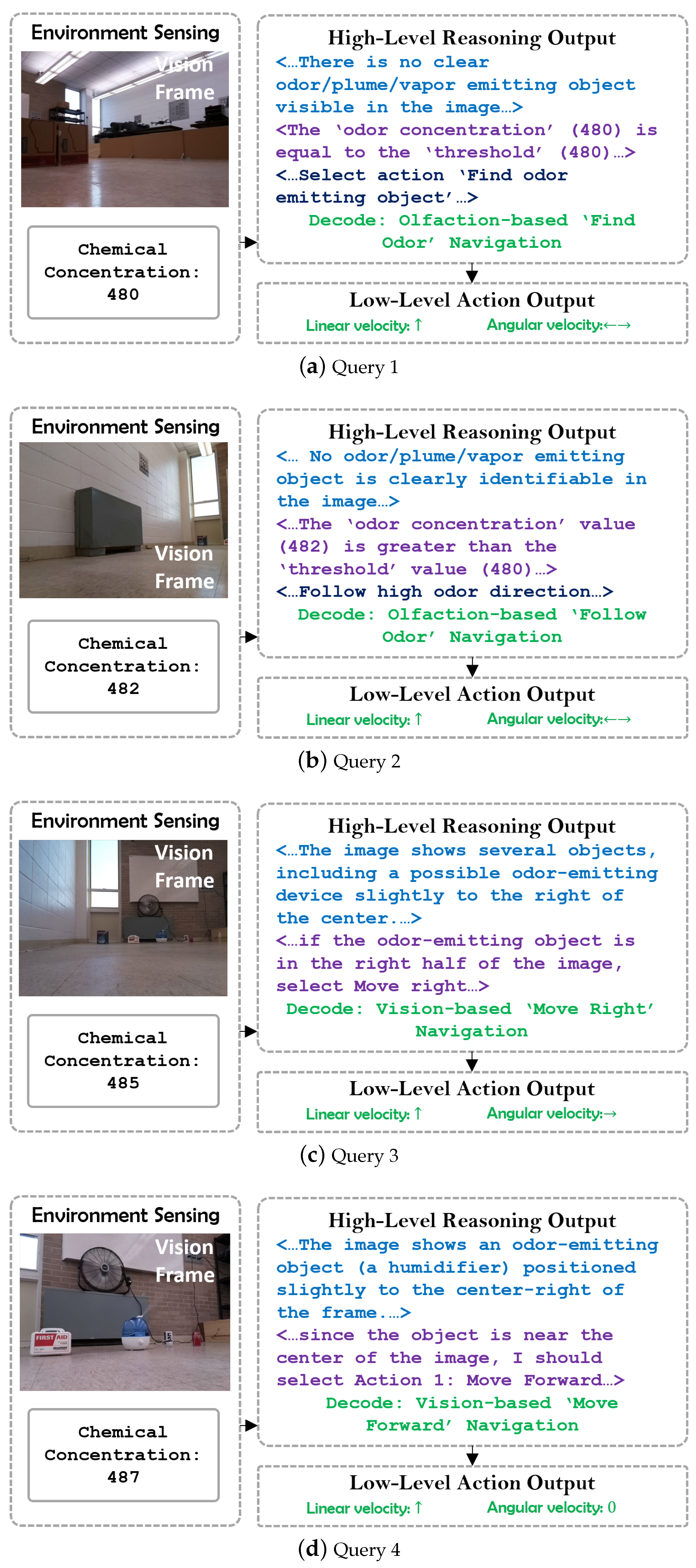

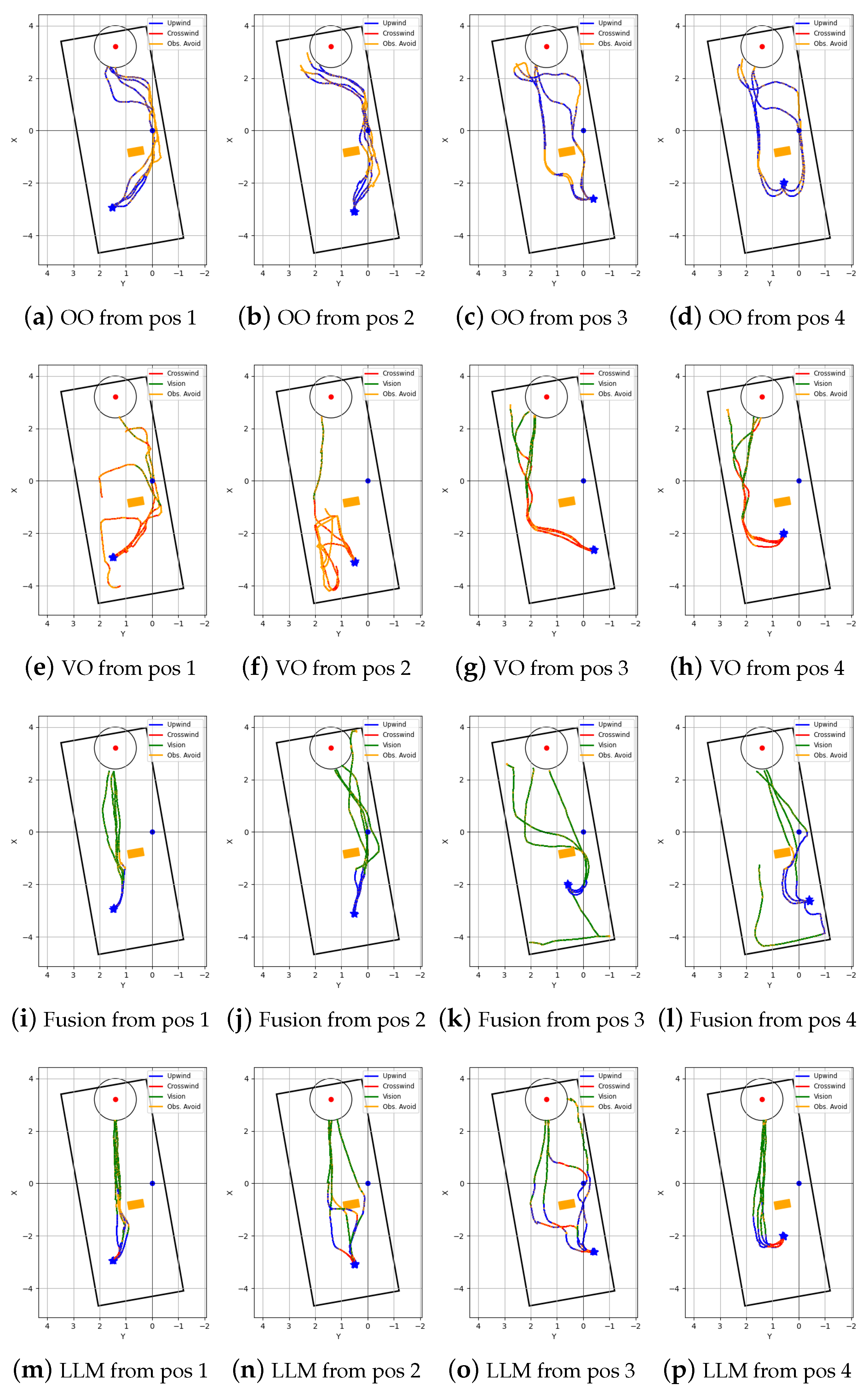

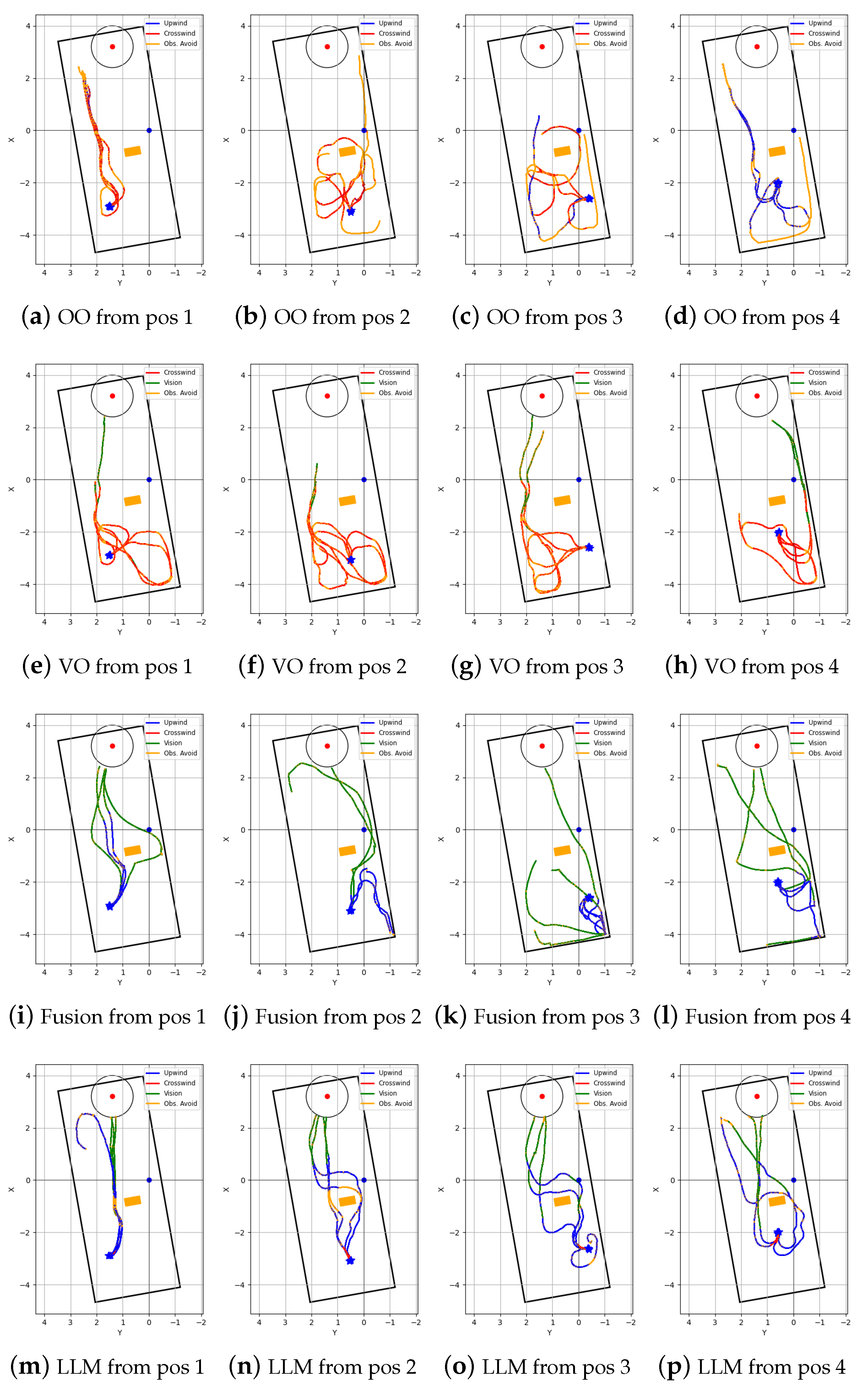

4.4. Sample Run

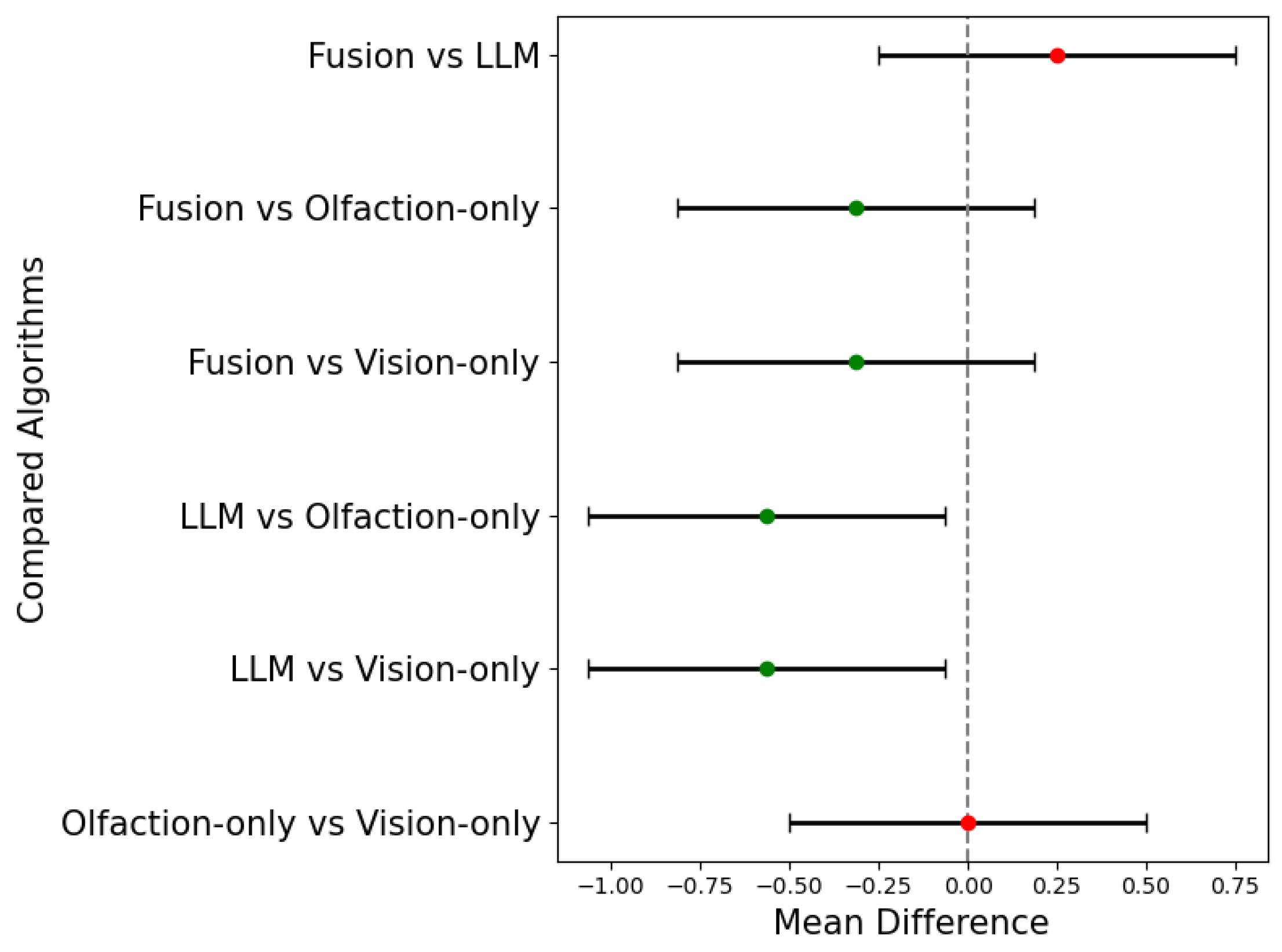

4.5. Repeated Test Result

5. Limitations and Future Works

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| OSL | Odor Source Localization |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| FWER | Family-Wise Error Rate |

| Tukey’s HSD | Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference Test |

| VLM | Vision Language Models |

| WOL | Web Ontology Language |

References

- Purves, D.; Augustine, G.; Fitzpatrick, D.; Katz, L.; LaMantia, A.; McNamara, J.; Williams, S. The Organization of the Olfactory System. Neuroscience 2001, 337–354. [Google Scholar]

- Sarafoleanu, C.; Mella, C.; Georgescu, M.; Perederco, C. The importance of the olfactory sense in the human behavior and evolution. Journal of Medicine and life 2009, 2, 196. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kowadlo, G.; Russell, R.A. Robot odor localization: a taxonomy and survey. The International Journal of Robotics Research 2008, 27, 869–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pang, S.; Noyela, M.; Adkins, K.; Sun, L.; El-Sayed, M. Vision and Olfactory-Based Wildfire Monitoring with Uncrewed Aircraft Systems. 2023 20th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR). IEEE, 2023, pp. 716–723.

- Fu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Ding, Y.; He, D. Pollution source localization based on multi-UAV cooperative communication. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 29304–29312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgués, J.; Hernández, V.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Marco, S. Smelling nano aerial vehicle for gas source localization and mapping. Sensors 2019, 19, 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.A. Robotic location of underground chemical sources. Robotica 2004, 22, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, J. Underground odor source localization based on a variation of lower organism search behavior. IEEE Sensors Journal 2017, 17, 5963–5970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Pang, S.; Xu, G. 3-dimensional hydrothermal vent localization based on chemical plume tracing. Global Oceans 2020: Singapore–US Gulf Coast. IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Jing, T.; Meng, Q.H.; Ishida, H. Recent progress and trend of robot odor source localization. IEEJ Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Engineering 2021, 16, 938–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardé, R.T.; Mafra-Neto, A. Mechanisms of flight of male moths to pheromone. In Insect pheromone research; Springer, 1997; pp. 275–290.

- López, L.L.; Vouloutsi, V.; Chimeno, A.E.; Marcos, E.; i Badia, S.B.; Mathews, Z.; Verschure, P.F.; Ziyatdinov, A.; i Lluna, A.P. Moth-like chemo-source localization and classification on an indoor autonomous robot. In On Biomimetics; IntechOpen, 2011. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Wang, Y.; Du, C.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, W. A novel odor source localization system based on particle filtering and information entropy. Robotics and autonomous systems 2020, 132, 103619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, M.; Kim, C.W.; Shin, D. Source localization for hazardous material release in an outdoor chemical plant via a combination of LSTM-RNN and CFD simulation. Computers & Chemical Engineering 2019, 125, 476–489. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Song, S.; Chen, C.P. Plume Tracing via Model-Free Reinforcement Learning Method. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockery, S.R. The computational worm: spatial orientation and its neuronal basis in C. elegans. Current opinion in neurobiology 2011, 21, 782–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potier, S.; Duriez, O.; Célérier, A.; Liegeois, J.L.; Bonadonna, F. Sight or smell: which senses do scavenging raptors use to find food? Animal Cognition 2019, 22, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frye, M.A.; Duistermars, B.J. Visually mediated odor tracking during flight in Drosophila. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments), 2009; e1110. [Google Scholar]

- Van Breugel, F.; Riffell, J.; Fairhall, A.; Dickinson, M.H. Mosquitoes use vision to associate odor plumes with thermal targets. Current Biology 2015, 25, 2123–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- L. Yv, F.; Hai, X.; Wang, Z.; Yan, A.; Liu, B.; Bi, Y. Integration of visual and olfactory cues in host plant identification by the Asian longhorned beetle, Anoplophora glabripennis (Motschulsky)(Coleoptera: Cerambycidae). PLoS One 2015, 10, e0142752.

- Kuang, S.; Zhang, T. Smelling directions: olfaction modulates ambiguous visual motion perception. Scientific reports 2014, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S. ; others. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar]

- Team, G.; Anil, R.; Borgeaud, S.; Wu, Y.; Alayrac, J.B.; Yu, J.; Soricut, R.; Schalkwyk, J.; Dai, A.M.; Hauth, A. ; others. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.11805. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, Y.; Li, C.; Dong, J.; Su, D.; Chu, C.; Yu, D. Mm-llms: Recent advances in multimodal large language models. arXiv, 2024; arXiv:2401.13601 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S.; Wang, L.; Mahmud, K.R. Robotic Odor Source Localization via Vision and Olfaction Fusion Navigation Algorithm. Sensors 2024, 24, 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, H.C. Motile behavior of bacteria. Physics today 2000, 53, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radvansky, B.A.; Dombeck, D.A. An olfactory virtual reality system for mice. Nature communications 2018, 9, 839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandini, G.; Lucarini, G.; Varoli, M. Gradient driven self-organizing systems. Proceedings of 1993 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS’93). IEEE, 1993, Vol. 1, pp. 429–432.

- Grasso, F.W.; Consi, T.R.; Mountain, D.C.; Atema, J. Biomimetic robot lobster performs chemo-orientation in turbulence using a pair of spatially separated sensors: Progress and challenges. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2000, 30, 115–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, R.A.; Bab-Hadiashar, A.; Shepherd, R.L.; Wallace, G.G. A comparison of reactive robot chemotaxis algorithms. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 2003, 45, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilienthal, A.; Duckett, T. Experimental analysis of gas-sensitive Braitenberg vehicles. Advanced Robotics 2004, 18, 817–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, H.; Nakayama, G.; Nakamoto, T.; Moriizumi, T. Controlling a gas/odor plume-tracking robot based on transient responses of gas sensors. IEEE Sensors Journal 2005, 5, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murlis, J.; Elkinton, J.S.; Carde, R.T. Odor plumes and how insects use them. Annual review of entomology 1992, 37, 505–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vickers, N.J. Mechanisms of animal navigation in odor plumes. The Biological Bulletin 2000, 198, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardé, R.T.; Willis, M.A. Navigational strategies used by insects to find distant, wind-borne sources of odor. Journal of chemical ecology 2008, 34, 854–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevitt, G.A. Olfactory foraging by Antarctic procellariiform seabirds: life at high Reynolds numbers. The Biological Bulletin 2000, 198, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallraff, H.G. Avian olfactory navigation: its empirical foundation and conceptual state. Animal Behaviour 2004, 67, 189–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigaki, S.; Sakurai, T.; Ando, N.; Kurabayashi, D.; Kanzaki, R. Time-varying moth-inspired algorithm for chemical plume tracing in turbulent environment. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 2017, 3, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigaki, S.; Shiota, Y.; Kurabayashi, D.; Kanzaki, R. Modeling of the Adaptive Chemical Plume Tracing Algorithm of an Insect Using Fuzzy Inference. IEEE Transactions on Fuzzy Systems 2019, 28, 72–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, F.; Marjovi, A.; Kibleur, P.; Martinoli, A. A 3-D bio-inspired odor source localization and its validation in realistic environmental conditions. 2017 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2017, pp. 3983–3989.

- Shigaki, S.; Yoshimura, Y.; Kurabayashi, D.; Hosoda, K. Palm-sized quadcopter for three-dimensional chemical plume tracking. IEEE Transactions on Instrumentation and Measurement 2022, 71, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakuba, M.V. Stochastic mapping for chemical plume source localization with application to autonomous hydrothermal vent discovery. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2007. [CrossRef]

- Vergassola, M.; Villermaux, E.; Shraiman, B.I. ‘Infotaxis’ as a strategy for searching without gradients. Nature 2007, 445, 406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luong, D.N.; Kurabayashi, D. Odor Source Localization in Obstacle Regions Using Switching Planning Algorithms with a Switching Framework. Sensors 2023, 23, 1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahbar, F.; Marjovi, A.; Martinoli, A. An algorithm for odor source localization based on source term estimation. 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2019, pp. 973–979.

- Hutchinson, M.; Liu, C.; Chen, W.H. Information-based search for an atmospheric release using a mobile robot: Algorithm and experiments. IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 2018, 27, 2388–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiu, H.; Chen, Y.; Deng, W.; Pang, S. Underwater chemical plume tracing based on partially observable Markov decision process. International Journal of Advanced Robotic Systems 2019, 16, 1729881419831874. [Google Scholar]

- Luong, D.N.; Tran, H.Q.D.; Kurabayashi, D. Reactive-probabilistic hybrid search method for odour source localization in an obstructed environment. SICE Journal of Control, Measurement, and System Integration 2024, 17, 2374569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Zhu, F. Reactive planning for olfactory-based mobile robots. 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. IEEE, 2009, pp. 4375–4380.

- Wang, L.; Pang, S. Chemical Plume Tracing using an AUV based on POMDP Source Mapping and A-star Path Planning. OCEANS 2019 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE. IEEE, 2019, pp. 1–7.

- Wang, L.; Pang, S. An Implementation of the Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) for Odor Source Localization. 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. IEEE, 2021.

- Monroy, J.; Ruiz-Sarmiento, J.R.; Moreno, F.A.; Melendez-Fernandez, F.; Galindo, C.; Gonzalez-Jimenez, J. A semantic-based gas source localization with a mobile robot combining vision and chemical sensing. Sensors 2018, 18, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, K. Natural language processing for word sense disambiguation and information extraction. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.02256. [Google Scholar]

- Nayebi, A.; Rajalingham, R.; Jazayeri, M.; Yang, G.R. Neural foundations of mental simulation: Future prediction of latent representations on dynamic scenes. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2024, 36. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. Advances in neural information processing systems 2017, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Wang, X.; Schuurmans, D.; Bosma, M.; Xia, F.; Chi, E.; Le, Q.V.; Zhou, D.; others. Chain-of-thought prompting elicits reasoning in large language models. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 24824–24837. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; others. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems 2022, 35, 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.D.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; others. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in neural information processing systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv, 2018; arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.A.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F. ; others. Llama: Open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13971. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Gan, Z.; Yang, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, L.; Gao, J.; others. Multimodal foundation models: From specialists to general-purpose assistants. Foundations and Trends® in Computer Graphics and Vision 2024, 16, 1–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J. ; others. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. International conference on machine learning. PMLR, 2021, pp. 8748–8763.

- Shi, Y.; Shang, M.; Qi, Z. Intelligent layout generation based on deep generative models: A comprehensive survey. Information Fusion 2023, 101940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Wu, Z.; Li, Y.; Jiang, H.; Shu, P.; Shi, E.; Hu, H.; Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X. ; others. Large language models for robotics: Opportunities, challenges, and perspectives. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.04334. [Google Scholar]

- Dorbala, V.S.; Sigurdsson, G.; Piramuthu, R.; Thomason, J.; Sukhatme, G.S. Clip-nav: Using clip for zero-shot vision-and-language navigation. arXiv, 2022; arXiv:2211.16649. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P.; Sun, X.; Zhi, H.; Zeng, R.; Li, T.H.; Liu, G.; Tan, M.; Gan, C. A2 Nav: Action-Aware Zero-Shot Robot Navigation by Exploiting Vision-and-Language Ability of Foundation Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.07997. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, G.; Hong, Y.; Wu, Q. Navgpt: Explicit reasoning in vision-and-language navigation with large language models. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 7641–7649.

- Schumann, R.; Zhu, W.; Feng, W.; Fu, T.J.; Riezler, S.; Wang, W.Y. Velma: Verbalization embodiment of llm agents for vision and language navigation in street view. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2024, Vol. 38, pp. 18924–18933.

- Shah, D.; Osinski, B.; Ichter, B.; Levine, S. Robotic Navigation with Large Pre-Trained Models of Language. Vision, and Action, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Kasaei, H.; Cao, M. L3mvn: Leveraging large language models for visual target navigation. 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS). IEEE, 2023, pp. 3554–3560.

- Zhou, K.; Zheng, K.; Pryor, C.; Shen, Y.; Jin, H.; Getoor, L.; Wang, X.E. Esc: Exploration with soft commonsense constraints for zero-shot object navigation. International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR, 2023, pp. 42829–42842.

- Jatavallabhula, K.M.; Kuwajerwala, A.; Gu, Q.; Omama, M.; Chen, T.; Maalouf, A.; Li, S.; Iyer, G.; Saryazdi, S.; Keetha, N. ; others. Conceptfusion: Open-set multimodal 3d mapping. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2302.07241. [Google Scholar]

- Brohan, A.; Brown, N.; Carbajal, J.; Chebotar, Y.; Dabis, J.; Finn, C.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Hausman, K.; Herzog, A.; Hsu, J. ; others. Rt-1: Robotics transformer for real-world control at scale. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.06817. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell, J.A.; Pang, S.; Li, W. Chemical plume tracing via an autonomous underwater vehicle. IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 2005, 30, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.; Wang, L.; Mahmud, K.R. Multi-Modal Robotic Platform Development for Odor Source Localization. 2023 Seventh IEEE International Conference on Robotic Computing (IRC). IEEE, 2023, pp. 59–62.

| Symbols | Parameters |

|---|---|

| p | Visual Observation |

| u | Wind Speed |

| Wind Direction | |

| Chemical Concentration |

| Source | Sensor Type | Module Name | Specification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Built-in | Camera | Raspberry Pi Camera v2 | Video Capture: 1080p30, 720p60 and VGA90. |

| Laser Distance Sensor | LDS-02 | Detection Range: 360-degree. Distance Range: 160∼8000 mm. |

|

| Added | Anemometer | WindSonic, Gill Inc. | Speed: 0–75 m/s. Wind direction: 0–360 degrees. |

| Chemical Sensor | MQ3 alcohol detector | Concentration: 25–500 ppm. |

|

Navigation Algorithm |

Search Time (s) | Travelled Distance (m) |

Success Rate ↑ |

||

| Mean ↓ |

Std. dev. ↓ |

Mean ↓ |

Std. dev. ↓ |

||

| Olfaction-only | 98.46 | 11.87 | 6.86 | 0.35 | 10/16 |

| Vision-only | 95.23 | 3.91 | 6.68 | 0.27 | 8/16 |

| Fusion | 84.2 | 12.42 | 6.12 | 0.52 | 12/16 |

| Proposed LLM-based | 80.33 | 4.99 | 6.14 | 0.34 | 16/16 |

|

Navigation Algorithm |

Search Time (s) | Travelled Distance (m) |

Success Rate ↑ |

||

| Mean ↓ |

Std. dev. ↓ |

Mean ↓ |

Std. dev. ↓ |

||

| Olfaction-only | - | - | - | - | 0/16 |

| Vision-only | 90.67 | - | 6.69 | - | 2/16 |

| Fusion | 97.79 | 4.69 | 7.08 | 0.53 | 8/16 |

| Proposed LLM-based | 85.3 | 5.03 | 6.37 | 0.31 | 12/16 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).