Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

24 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Crowdsourcing Software Design (CSD)

- Requesters: Companies or individuals, who post the issues they want to solve as a freelance job or contest.

- Crowd: The community of online workers who have signed up for the platforms and then decided as individuals or small teams whether to take on an open call challenge.

- Platforms: Computer systems that provide an online marketplace for workers and clients to meet. This marketplace mediates and connects requesters with online workers to solve tasks.

2.2. Literature Review

3. Approach

4. Stage 1: Investigating Current CSD Process

5. Stage 2: Identifying Coordination Needs

- What are the inputs/outputs to each activity (e.g., informational and other necessary pre-conditions/post-conditions)?

- What potential performance problems associated with this process? Do these problems reflect unmanaged [or poorly managed] dependencies?

6. Stage 3: Evaluation of Existing and Proposed Coordination Mechanisms

7. Stage 4: Design Process Models

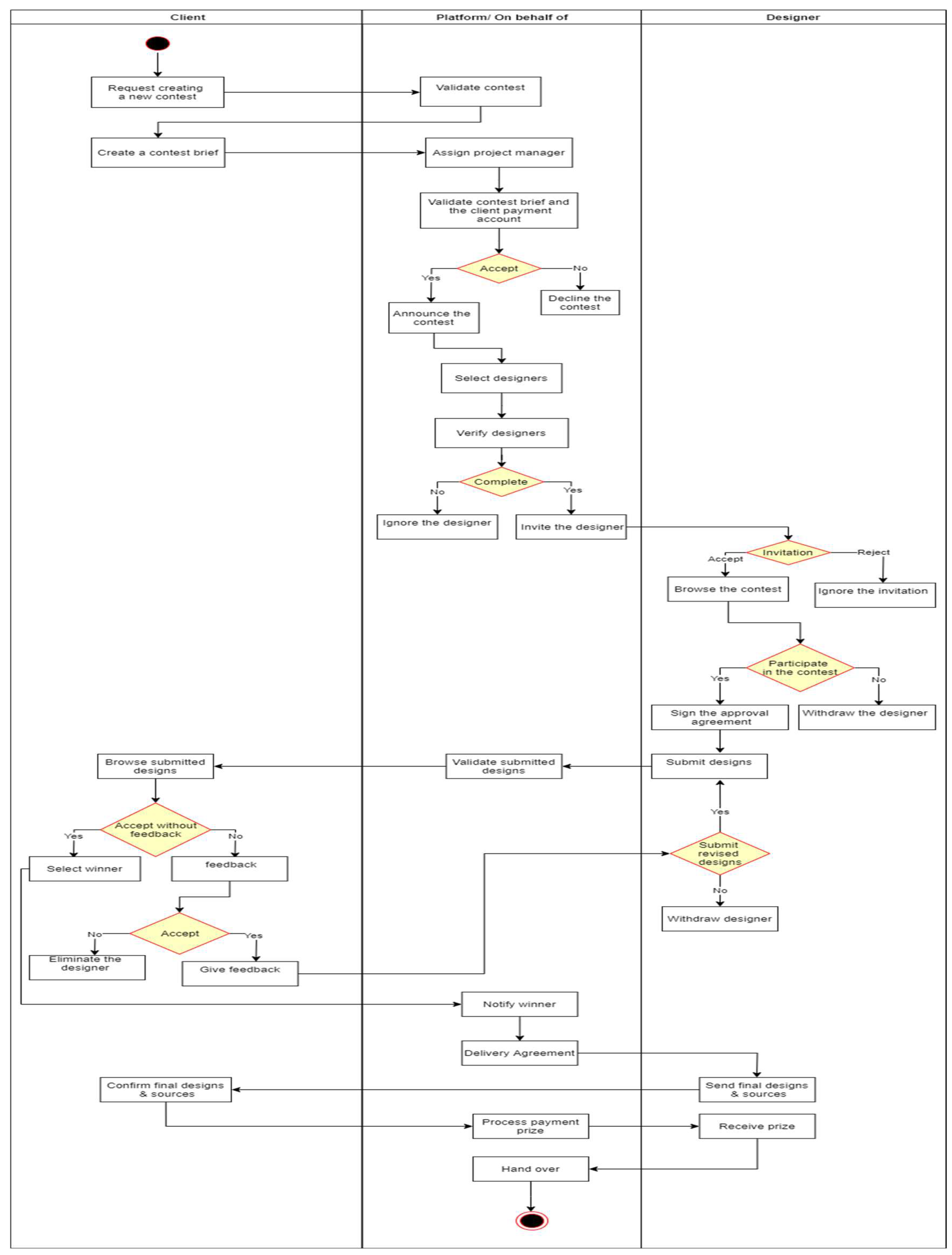

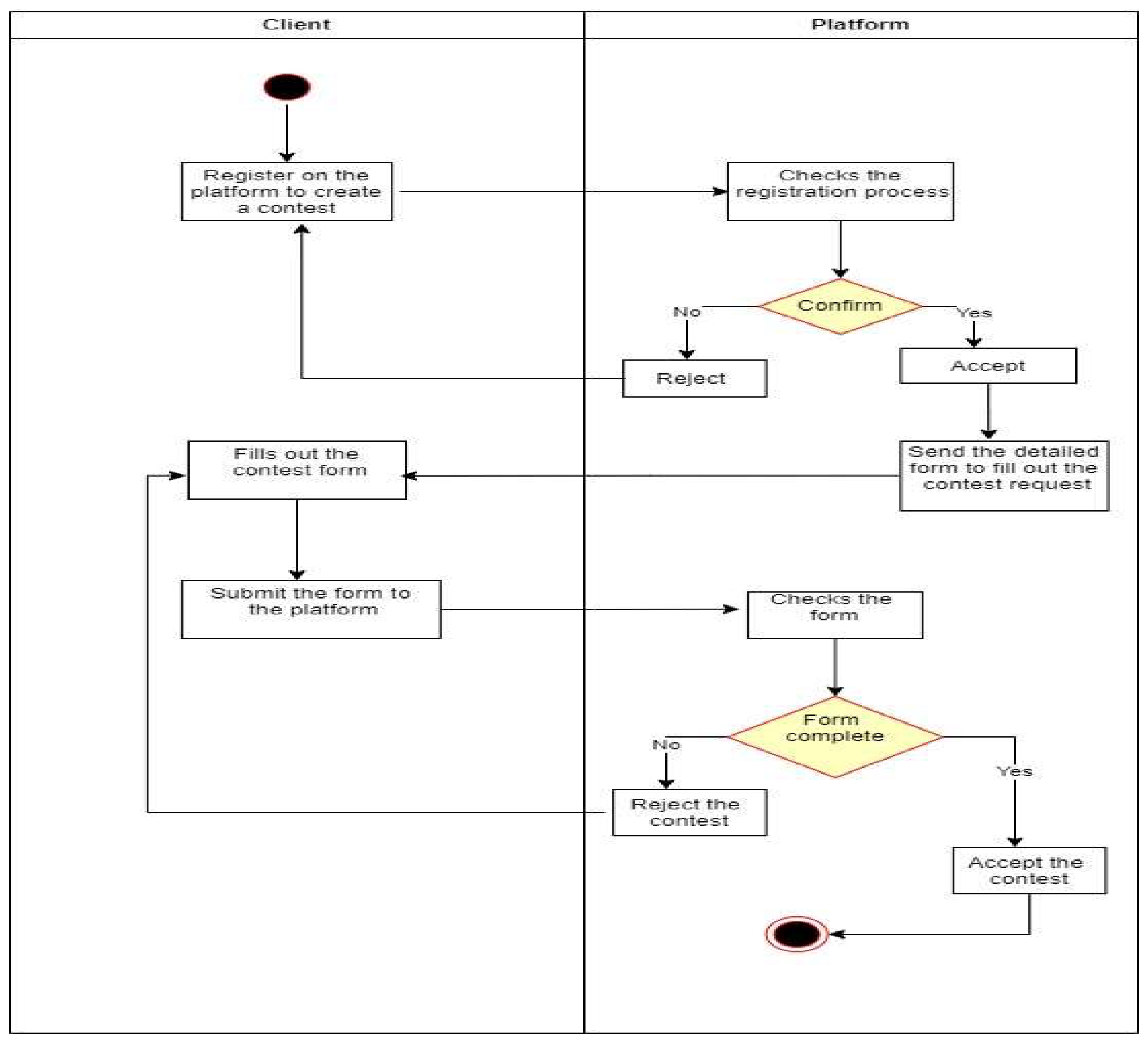

7.1. P1: Create Contest Brief

7.2. P2: Assign a Project Manager and Validate Contest Brief

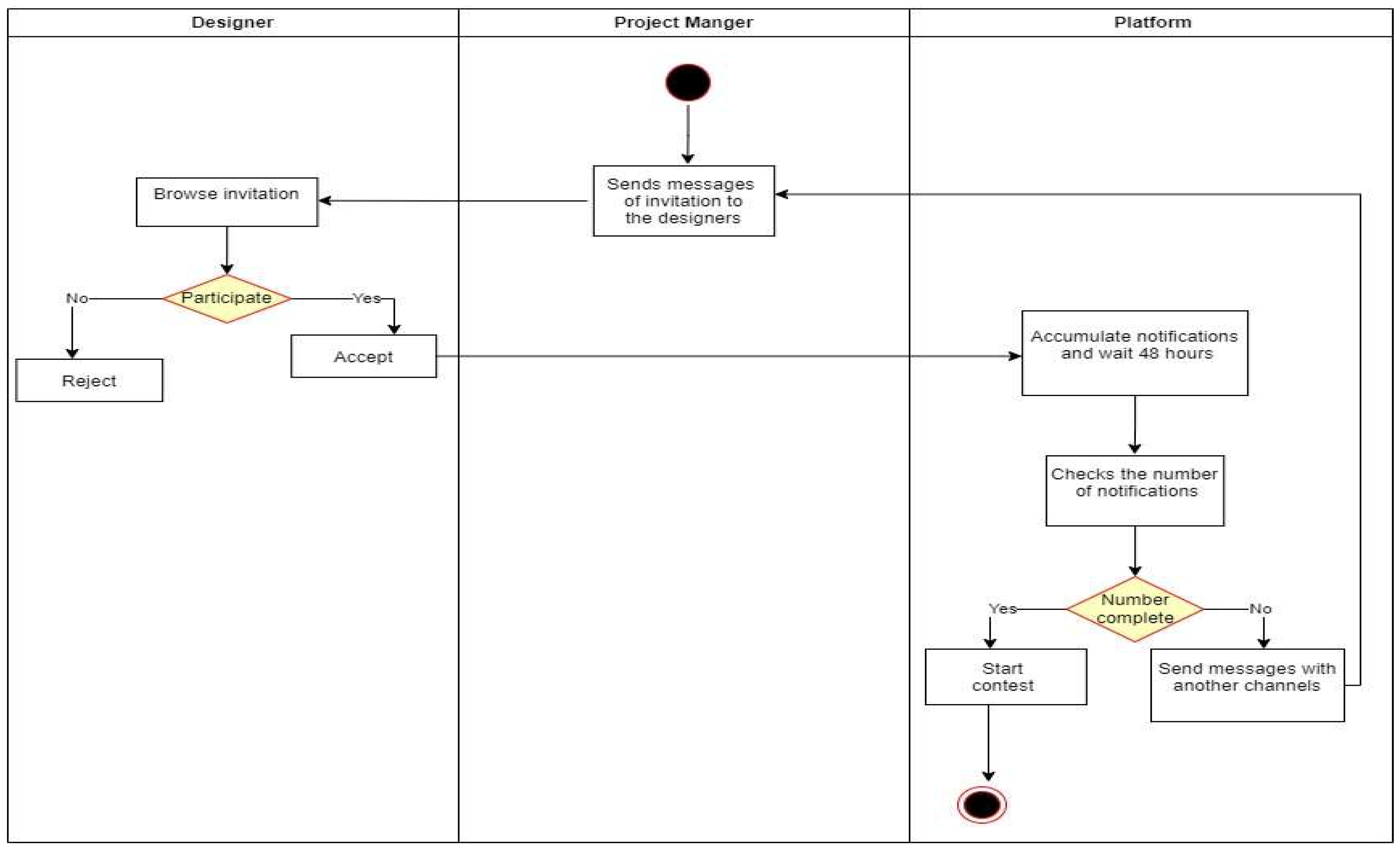

7.3. P3: Announce the Contest

8. Stage 5: Evaluation of the Process Models

8.1. Interviewees Background

8.2. Interview Findings

9. Conclusions

Appendix: Process Models

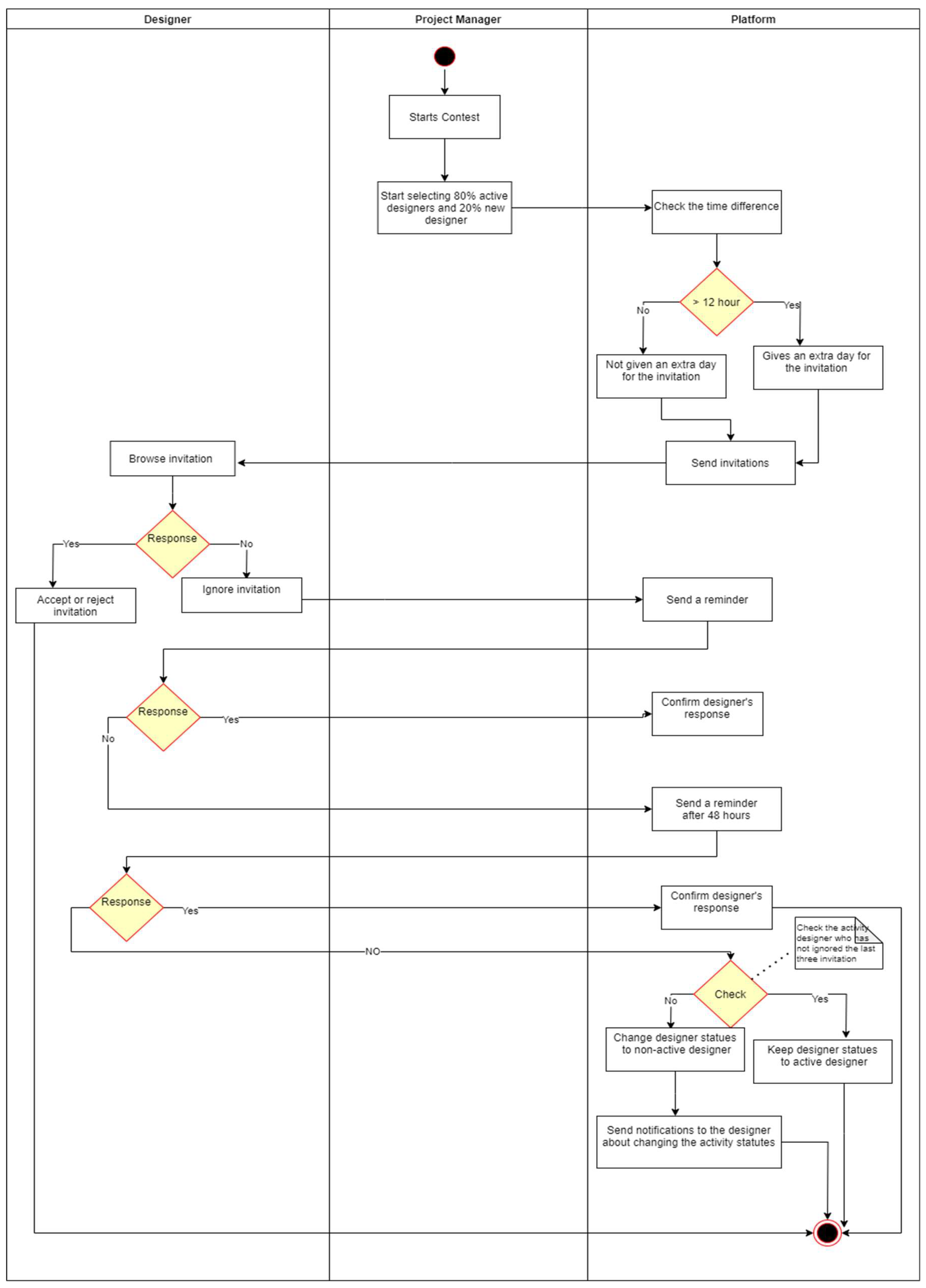

P4: Select Designers

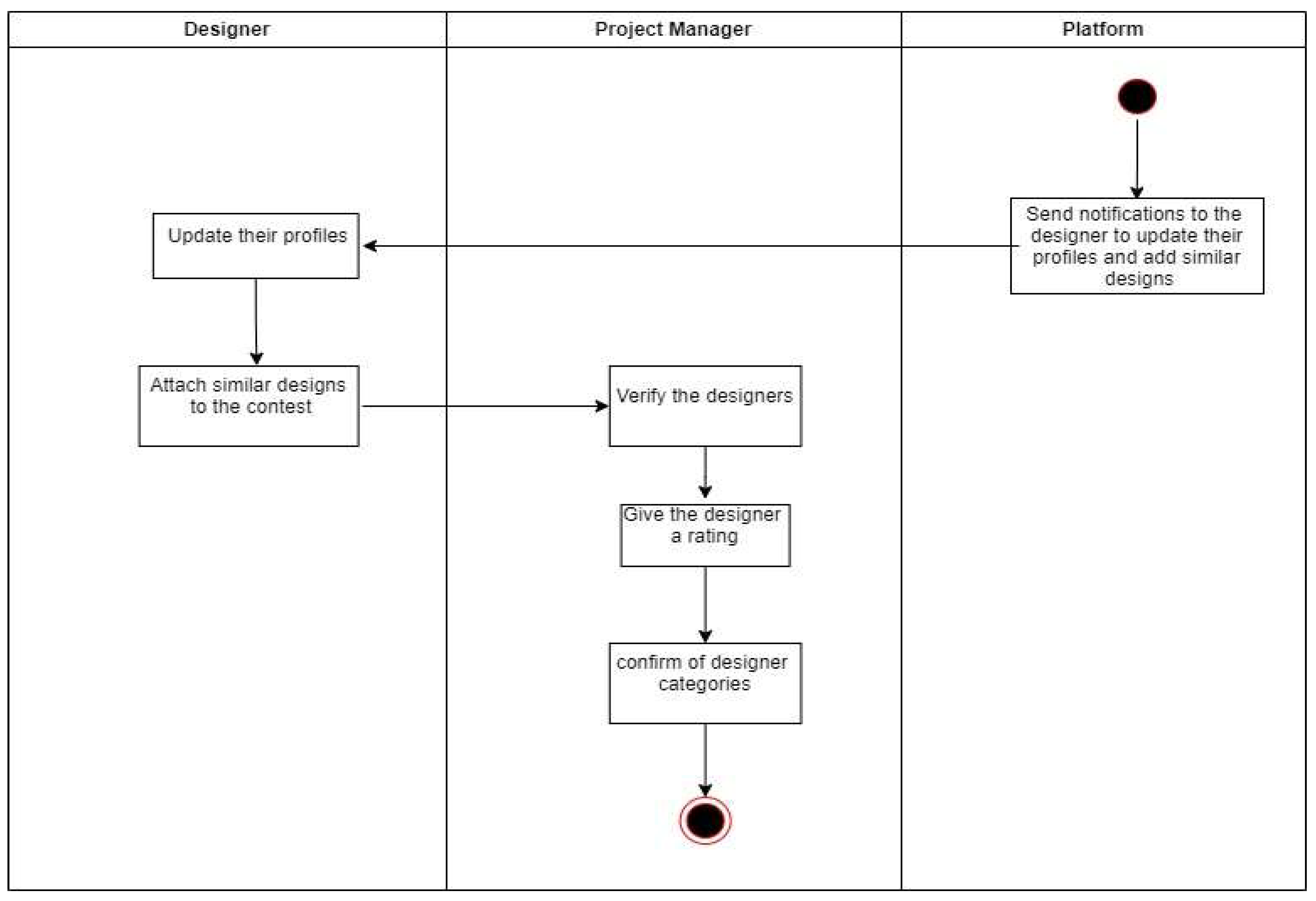

P5: Verify Designers

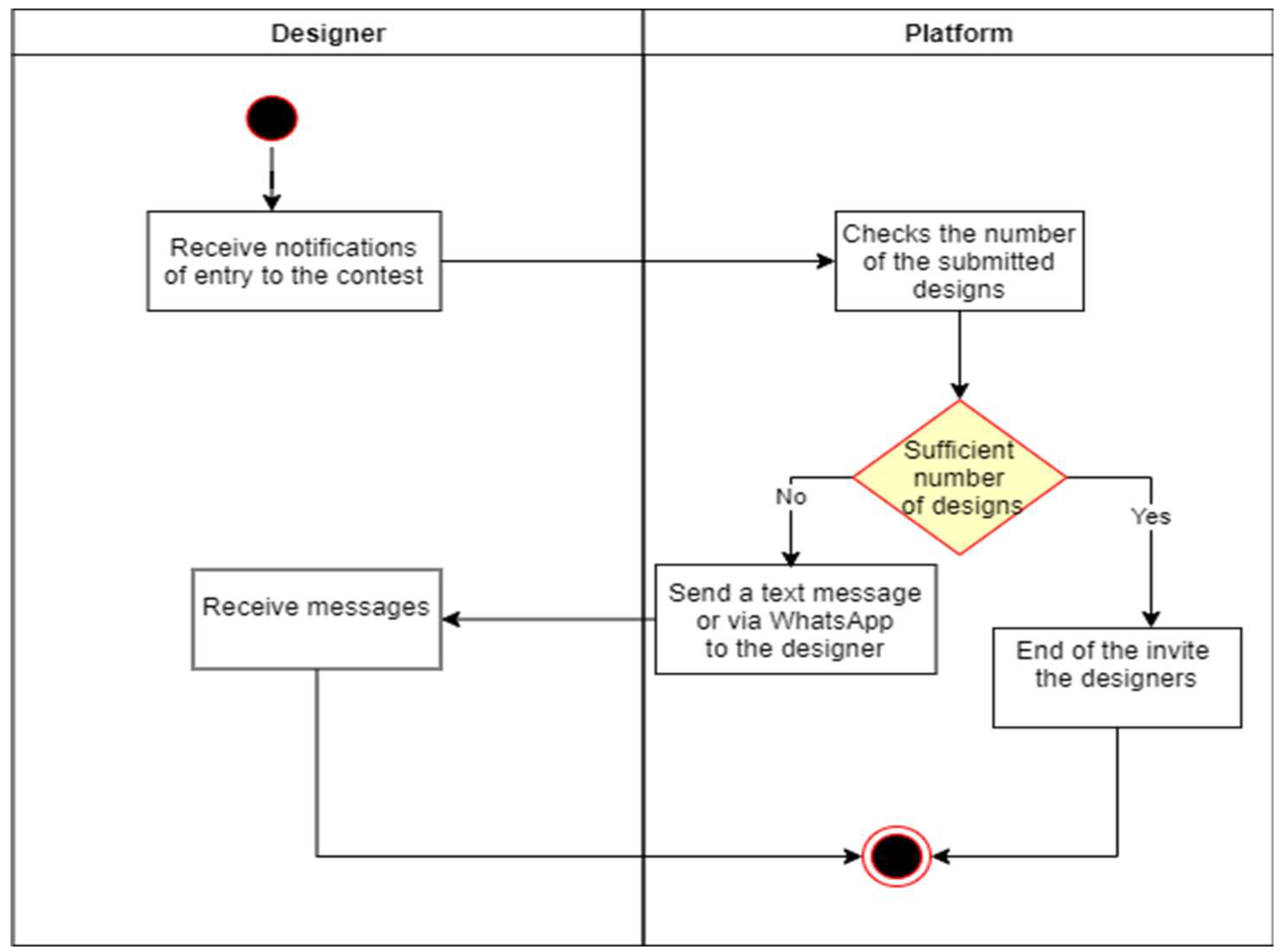

P6: Invite Designers

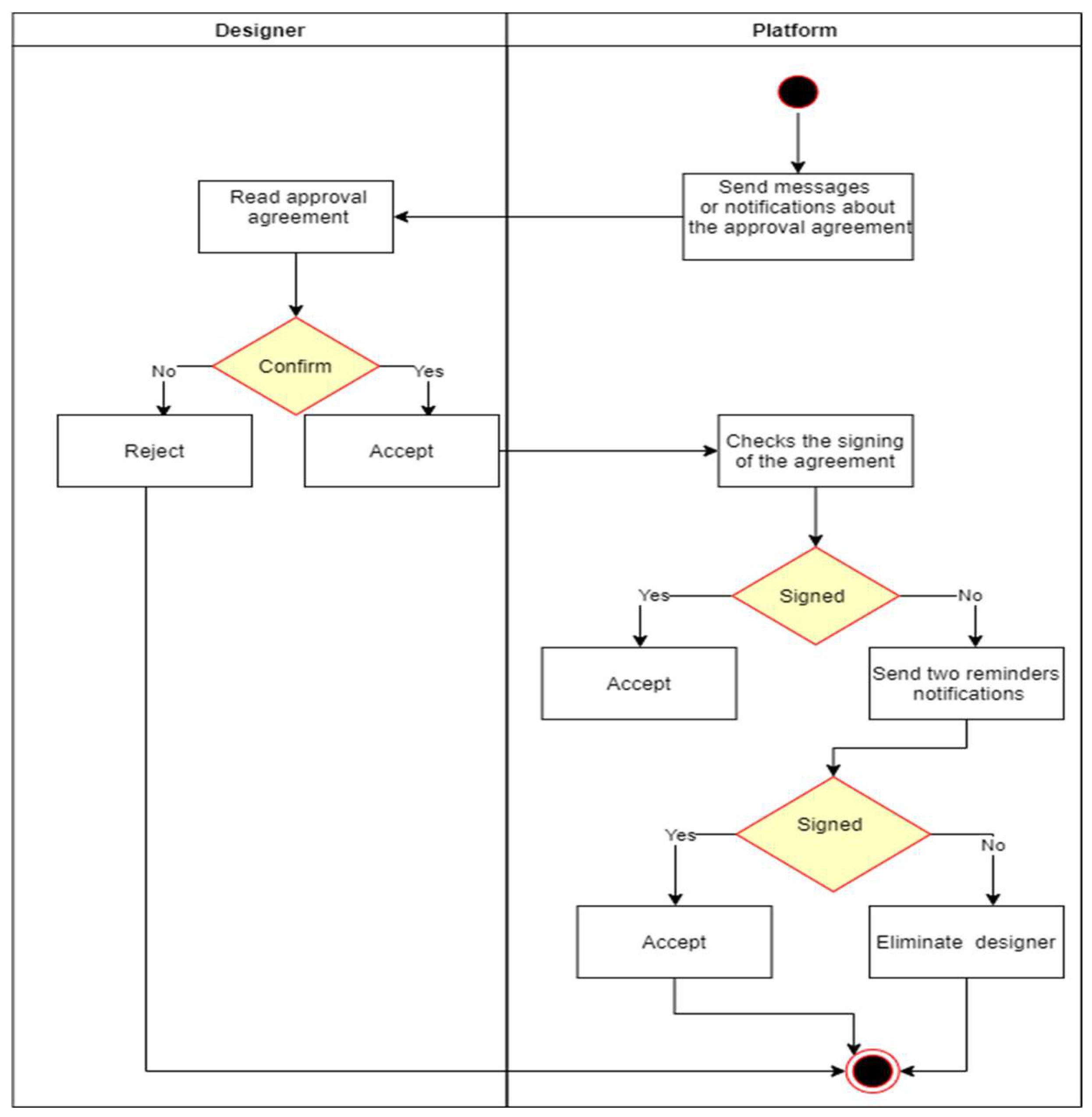

P7: Approval Agreement

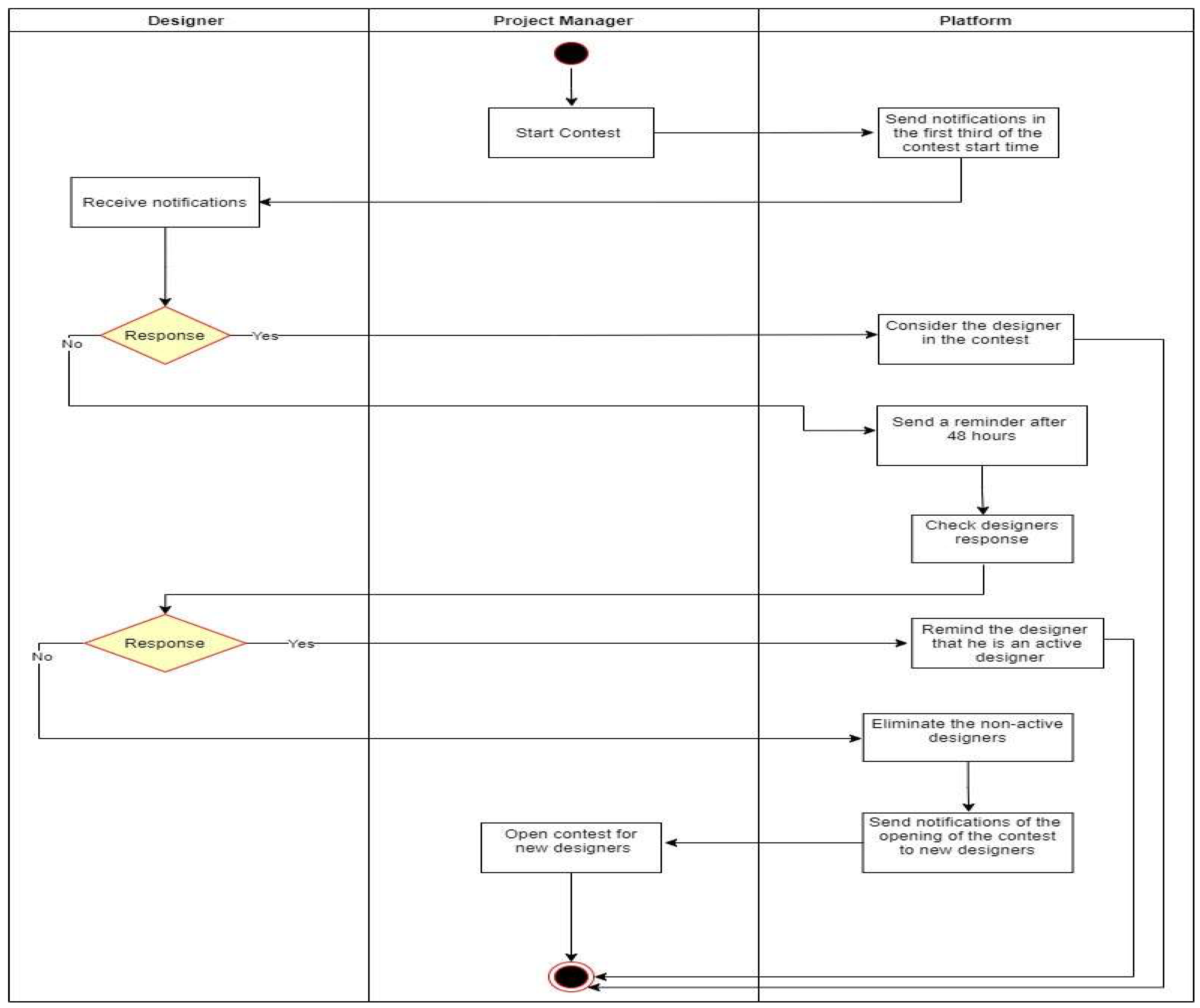

P8: Participate in the Contest

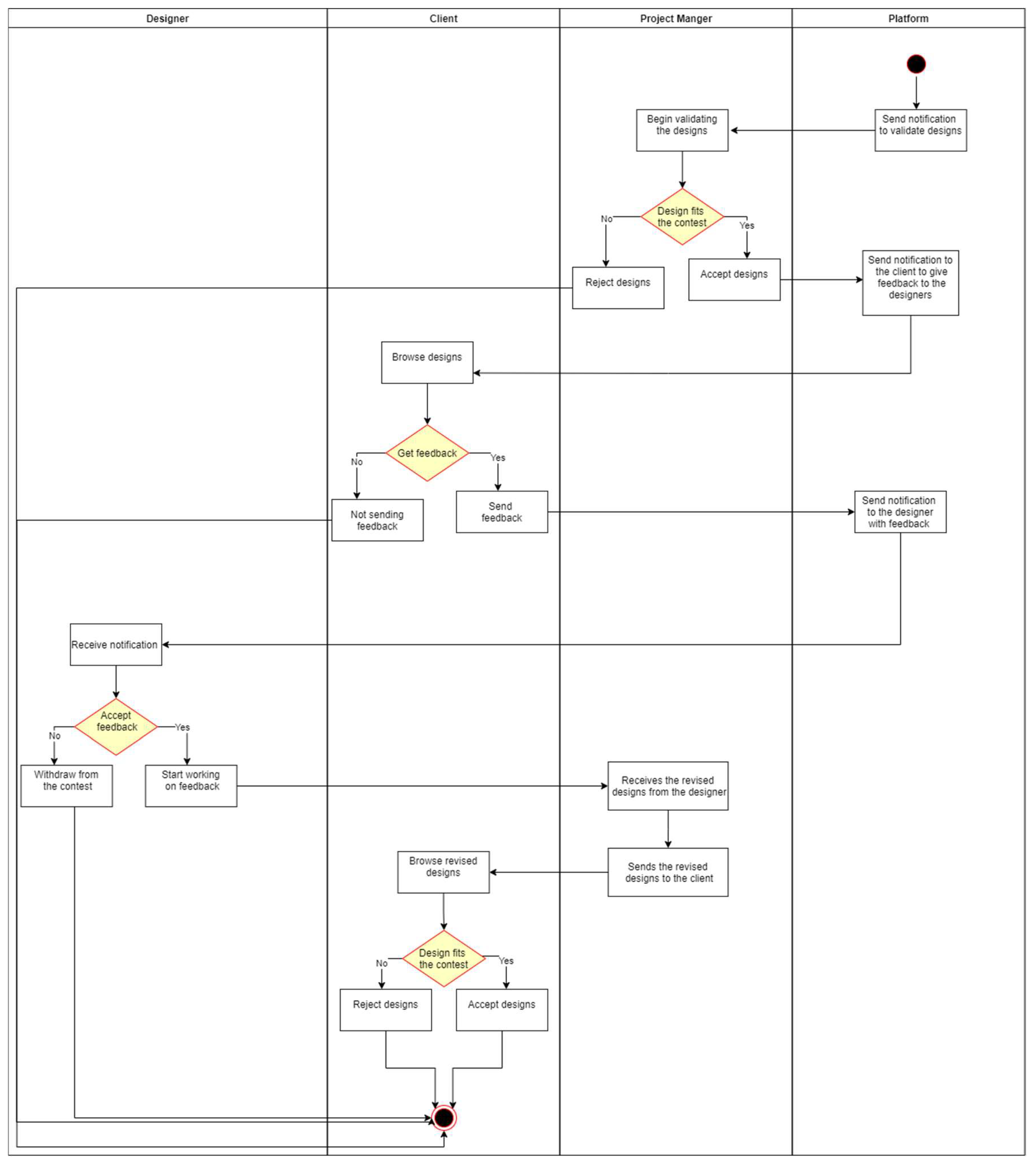

P9: Validate Designs and Provide Feedback by Client

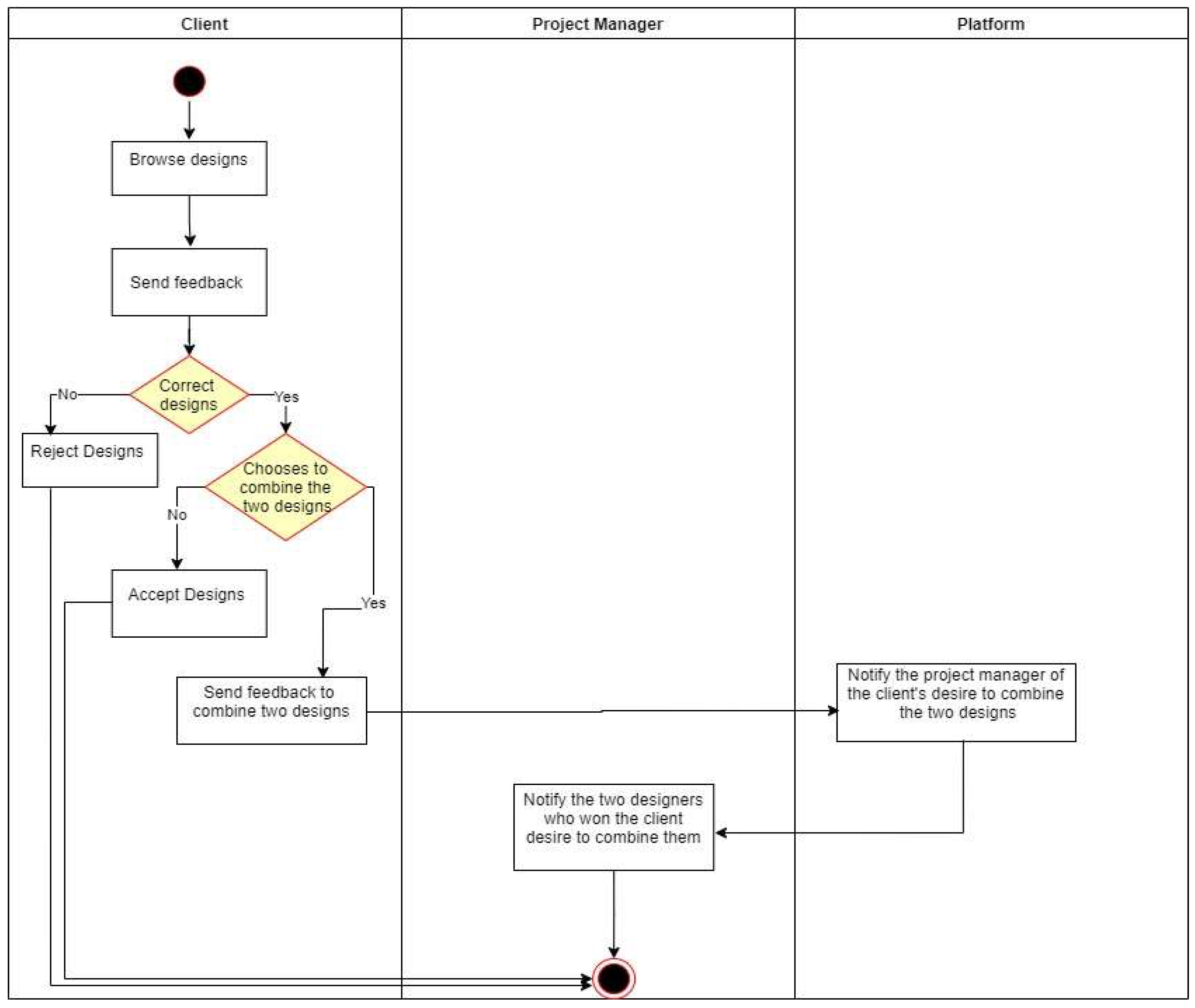

P10: Combine Two Designs That Complement Each Other Through Feedback

References

- X. Peng, M. Ali Babar, and C. Ebert, “Collaborative software development platforms for crowdsourcing,” IEEE Softw., 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Stol and B. Fitzgerald, “Research Protocol for a Case Study of Crowdsourcing Software Development,” Lero Tech. Rep. Lero, no. 10, 2014.

- C. Amrit, J. van Hillegersberg, and K. Kumar, “Identifying coordination problems in software development: finding mismatches between software and project team structures,” arXiv Prepr. arXiv1201.4142, 2012.

- Blohm, S. Zogaj, U. Bretschneider, and J. M. Leimeister, “How to manage crowdsourcing platforms effectively?,” Calif. Manage. Rev., vol. 60, no. 2, pp. 122–149, 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Coleman, S. Hurley, C. Koliba, and A. Zia, “Crowdsourced Delphis: Designing solutions to complex environmental problems with broad stakeholder participation,” Glob. Environ. Chang., vol. 45, pp. 111–123, 2017. [CrossRef]

- H. Wu, J. Corney, and M. Grant, “An evaluation methodology for crowdsourced design,” Adv. Eng. Informatics, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 775–786, 2015. [CrossRef]

- L. Xiao and H.-Y. Paik, “Supporting Complex Work in Crowdsourcing Platforms: A View from Service-Oriented Computing,” 2014 23rd Australian Software Engineering Conference. IEEE, pp. 11–14, 2014. [CrossRef]

- SARI and G. I. ALPTEK\.IN, “An Overview of Crowdsourcing Concepts in Software Engineering,” Int. J. Comput., vol. 2, 2017.

- X. Niu, S. Qin, H. Zhang, M. Wang, and R. Wong, “Exploring product design quality control and assurance under both traditional and crowdsourcing-based design environments,” Adv. Mech. Eng., vol. 10, no. 12, 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Simperl, “How to use crowdsourcing effectively: Guidelines and examples,” Lib. Q., vol. 25, no. 1, 2015. [CrossRef]

- K. Crowston, E. Mitchell, and C. Østerlund, “Coordinating Advanced Crowd Work: Extending Citizen Science,” Citiz. Sci. Theory Pract., 2019. [CrossRef]

- K. Crowston and C. S. Osborn, “A coordination theory approach to process description and redesign,” Organ. Bus. Knowl. MIT Process Handb., 2003.

- Almughram and S. Alyahya, “Coordination support for integrating user centered design in distributed agile projects,” 2017. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Stol and B. Fitzgerald, “Researching crowdsourcing software development: Perspectives and concerns,” 2014. [CrossRef]

- K. Mao, L. Capra, M. Harman, and Y. Jia, “A survey of the use of crowdsourcing in software engineering,” J. Syst. Softw., 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. T. D. Yuan and C. F. Hsieh, “An impactful crowdsourcing intermediary design - a case of a service imagery crowdsourcing system,” Inf. Syst. Front., 2018. [CrossRef]

- S. Alyahya, “Collaborative Crowdsourced Software Testing,” Electron., vol. 11, no. 20, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Alyahya, “Crowdsourced software testing: A systematic literature review,” Information and Software Technology, vol. 127. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhao and Q. Zhu, “Evaluation on crowdsourcing research: Current status and future direction,” Inf. Syst. Front., 2014. [CrossRef]

- M. Hosseini, K. Phalp, J. Taylor, and R. Ali, “The four pillars of crowdsourcing: A reference model,” 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. D. LaToza and A. Van Der Hoek, “Crowdsourcing in software engineering: Models, motivations, and challenges,” IEEE Softw., 2016. [CrossRef]

- D. Murray-Rust, O. Scekic, and D. Lin, “Worker-Centric Design for Software Crowdsourcing: Towards Cloud Careers,” Progress in IS. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 39–50, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Alyahya and G. Alamer, “Managing work dependencies in open source software platforms,” 2019. [CrossRef]

- L. dos S. Machado, “Empirical studies about collaboration in competitive software crowdsourcing,” The Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande, Brazil, 2018.

- C. Amrit, “Coordination in software development: The problem of task allocation,” 2005. [CrossRef]

- R. Aliady and S. Alyahya, “Crowdsourced software design platforms: Critical assessment,” J. Comput. Sci., vol. 14, no. 4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sultan, W. K. Ivins, and W. A. Gray, “A holistic approach to developing a progress tracking system for distributed agile teams,” 2012. [CrossRef]

- “99designs.” https://99designs.com.

- “DesignCrowd.” https://www.designcrowd.com/.

- “DesignHill.” DesignHill.com.

- “CrowdSpring.” CrowdSpring.com.

- “CrowdSite.” CrowdSite.com.

- “Freelancer.” .

- “Upwork.” Upwork.com.

- “Designfier.” .

- “DesignContest.” DesignContest.com.

- “Guerra Creativa.” https://www.guerra-creativa.com.

- “hatchwise.” .

- “110designs.” .

- “MOJO Marketplace.” .

- “Fiverr.” .

| Platforms | Platform type | Year of Foundation | Head Quarter | Community Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 99design [28] | Design | 2008 | Australia | 4 million |

| DesignCrowd [29] | Design | 2008 | Australia | 616,000 |

| DesignHill [30] | Design | 2014 | India | 125,000 |

| CrowdSpring [31] | Generic | 2008 | USA | 210,000 |

| CrowdSite [32] | Generic | 2009 | Netherland | 532,000 |

| Freelancer [33] | Generic | 2009 | Australia | 34 million |

| Upwork [34] | Generic | 2000 | Athens | 5 million |

| Designfier [35] | Design | 2017 | USA | Unknown |

| DesignContest [36] | Design | 2003 | USA | 160,000 |

| Guerra Creativa [37] | Design | 2011 | Argentina | 14,000 |

| Hatchwise [38] | Design | 2008 | USA | 8 million |

| 110designs [39] | Design | 2011 | USA | 22,000 |

| MOJO Marketplace [40] | Generic | 2009 | USA | 5.8 million |

| Fiverr [41] | Generic | 2010 | USA | Unknown |

| Activity | Dependency | Current Platform Support | Potential Limitations | Proposed Coordination Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1: Create contest brief |

The project manager is assigned to the contest after the client creates the contest brief. | The project manager will only be assigned by filling out the contest form, as the platform provides a form for the client to manually write the contest brief and attach all files and contest details, and this form helps reduce time and effort in selecting the project manager. | L1. The unavailability of a form including all the information related to the contest that will be conducted may lead to a misunderstanding of the requirements of the contest. | S1. The platform provides a detailed form that includes all the requirements to ensure the proper functioning of the contest (i.e., client expectations, design preferred colors, design plans). |

| L2. The client may ignore the need to attach important files to the contest, which may lead to design errors. |

S2. Set constraints on the client to ensure they add all the information and details related to the contest in terms of the objectives and the expected final result from the contest and that they attach the files related to the design. | |||

| A2: Assign a project manager | Platforms assign a project manager for each contest and then start an announcement for the contest. | The platform assigns the project manager manually based on the contest brief and client requirements, and the project manager must validate the contest, then publish the contest announcement on the platform page. |

L3. Manually selecting a project manager may take a significant amount of time away from the contest. | S3. Automatically select the project manager based on the type of contest. |

| L4. A project manager who is busy with too many contests may be selected, and therefore, the project manager’s schedule would not fit the new contest and thus may affect the effectiveness of the contest. | S4. Set constraints on capacity related to the association of contests with project manager. | |||

| A3: Validate contest brief |

Before the contest can be announced, the project manager must validate the contest and payment. | The project manager manually validates the contest, reviews the contest feed, verifies all client accounts and data, and then publishes the contest announcement. | L5. A project manager may publish unqualified contests because he may not be in his fields of interest or competence. | S5. It is good to categorize the contest by making a list of contest types by field and competency and to ensure that the project manager has a background related to the type of contest to help validate the contest efficiently. |

| A4: Announce the contest |

The project manager chooses the designers after the contest is announced. | The project manager announces the contest by announcing it on the platform page, and thus the project manager can select the designers following the requirements attached to the contest brief. | L6. There is a lack of multiple communication channels available to send contest announcement messages to designers, thus resulting in a potential missed opportunity for different designers to participate in the contest. | S6. Send messages or notifications on social media accounts or email regarding a new contest. |

| A5: Select designers |

The project manager selects suitable designers to invite to participate in the contest. | The project manager selects the designers based on the client’s requirements, the selection is based on the designer’s rank, grade, and the number of times to participate in contests and similar designs, then the project manager sends invitations to the designers. | L7. The availability of designers on the platform is not considered so there is no distinction made between active and inactive designers when they are invited to participate in the contest. This may lead to a lack of diversity in designs because not all different designers who have been invited participate, and this may lead to the loss of the opportunity to participate for new active designers. | S7. Set a constraint to select active designers only. |

| L8. New designers may not be selected because they did not participate in any contests. | S8. Reserve some invitations for new designers to participate in the contest. | |||

| A6: Verify designers |

The project manager verifies the designers, to invite them to participate in the contest. | The project manager can manually determine the suitability of designers who have a design history registered in the platform. | L9. It may be difficult for the project manager to verify some designers because new designers do not have a design history or because there is no history of the designers in the contest field. | S9. The suitability of designers without history can still be evaluated by asking them to submit a sample of similar designs so that the project manager can check their skill level. |

| A7: Invite designers |

The project manager sends invitations to designers to participate in the contest, so the designers can browse the contest and accept the invitation or not participate. | The project manager automatically invites the appropriately selected designers via email or through notifications on the designer page, thus through the invitation designers can browse the contest and see the contest brief, which helps them decide whether to accept the invitation and participate in the contest or not to accept the invitation to participate. | L10. Designers may not check their email for contest notifications. |

S10. To communicate with designers through various communication channels, such as WhatsApp or text messages. |

| L11. The time difference between countries is not considered when sending invitations to designers. | S11. Take into account the time difference when sending invitations to designers; The project manager must check the time before sending out invitations to the designers, and an additional day can be added to the invitation if there is a significant difference in time zones before the start of the contest. | |||

| A8: Approval Agreement |

Before designers can browse the contest, they must accept or reject the approval agreement on the invitation. | The project manager sends the invitation to the designers by email. If the designers decide to participate in the contest, they move to the contest page and then move to the approval agreement. The designer can, then agrees and browse the contest brief. | L12. The platform does not remind designers about the need to agree to the Approval Agreement if they do not respond. | S12. Remind the designers that the approval agreement has not been completed and that he is not currently considered a participant in the contest. It is also a good idea to provide automated support to respond to the approval agreement through notifications or multiple communication channels, such as WhatsApp or text messages. |

| A9: Participate in the contest |

Designers work on the contest and submit their designs for validation, based on the time specified in the contest brief. | Platform can only prevent designers from submitting their works if deadline is reached. | L13. There is a lack of mechanisms to monitor contest progress and designers who do not submit designs to the contest. | S13. Send notifications to designers about the progress of the contest or notify inactive designers to fulfill their obligation to submit designs; otherwise, they must be withdrawn to allow new designers to join the contest. |

| A10: Validate submitted designs |

The project manager waits until a sufficient number of designs have been sent by the designers, and the project manager validates the designs before submitting them to the client. | The Project Manager validates designs for compliance with the contest brief, browses, reviews and ratings, and presents fair designs in proportion to the contest brief to the client to save his time and effort in searching for designs. | L14. The validation process takes place in the final stages of the contest. Thus, the validation process may take long time. This may waste the designers’ time and effort. |

S14. Provide support by notifying the client to validate the designs as soon as the project manager receives the designs from designers. |

| A11: Browse submitted designs |

The client browses and reviews submitted designs that meet the requirements of the contest brief | The client browses the designs submitted by the designers, and reviews them in accordance with the requirements of the contest brief. The client either selects the designs that are compatible with feedback, or cancels the designs that are not appropriate. | L15. The client eliminates some designs during the evaluation phase when they are evaluating the designs, which in turn may result in wasted designer effort. |

S15. Setting constraints and obligations on the client to oblige him to browse all designers’ designs that are in the meet with the contest brief that was sent by the project manager in the early stages of the contest. |

| A12: Give Feedback |

The client has to browse the designs in the first round and give feedback on the designs, until they move to the final stage of the contest and the designers submit the revised designs. | The client browses the designs submitted in the first stage and chooses, while browsing, the designs that suit the requirements of the contest, while giving manual feedback to make the required modifications so that they can move to the final stage. | L16. Clients do not provide designers with direct feedback nor communicate with designers during the contest period. This may result in poor designs. | S16. Provide a mechanism for communication through the platform that enables clients to provide feedback to the designers during the contest. |

| L17. It is possible that two designs are submitted, but neither can be accepted in their current states. Currently, there is no mechanism to enable clients to request to combine both designs to produce a better design. | S17. Provide a mechanism during the feedback phase that enables the client to combine two designs that complement each other. |

| Limitations / Suggestions | Average | Interpretation | Limitations / Suggestions | Average | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 4.09 | Positive | S9 | 3.41 | Positive |

| S1 | 3.88 | Positive | L10 | 3.53 | Positive |

| L2 | 3.76 | Positive | S10 | 3.32 | Moderate |

| S2 | 3.68 | Positive | L11 | 3.37 | Moderate |

| L3 | 3.71 | Positive | S11 | 3.26 | Moderate |

| S3 | 3.62 | Positive | L12 | 3.52 | Positive |

| L4 | 3.82 | Positive | S12 | 3.35 | Moderate |

| S4 | 3.74 | Positive | L13 | 3.77 | Positive |

| L5 | 3.91 | Positive | S13 | 3.65 | Positive |

| S5 | 3.65 | Positive | L14 | 3.47 | Positive |

| L6 | 3.88 | Positive | S14 | 3.56 | Positive |

| S6 | 3.79 | Positive | L15 | 3.32 | Moderate |

| L7 | 3.52 | Positive | S15 | 3.35 | Moderate |

| S7 | 3.27 | Moderate | L16 | 3.68 | Positive |

| L8 | 3.38 | Positive | S16 | 3.71 | Positive |

| S8 | 3.56 | Positive | L17 | 3.53 | Positive |

| L9 | 3.65 | Positive | S17 | 3.47 | Positive |

| The design contest part | The corresponding process model | Activity covered | The Proposed Coordination mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Creating design contest |

P1: Create contest brief |

A1 | S1. The platform provides a detailed form that includes all the requirements to ensure the proper functioning of the contest (i.e., client expectations, design preferred colors, design plans). |

| S2. Set constraints on the client to ensure they add all the information and details related to the contest in terms of the objectives and the expected final result from the contest and that they attach the files related to the design. | |||

| P2: Assign a project manager and Validate contest brief | A2 |

S3. Automatically select the project manager based on the type of contest. | |

| S4. Set constraints on capacity related to the association of contests with project manager. | |||

| A3 | S5. It is good to categorize the contest by making a list of contest types by field and competency and to ensure that the project manager has a background related to the type of contest to help validate the contest efficiently. | ||

| P3: Announce the contest | A4 | S6. Send messages or notifications on social media accounts or email regarding a new contest. | |

| Performing designs and following up on contest design activities |

P4: Select designers |

A5 |

S7. Set a constraint to select active designers only. |

| S8. Reserve some invitations for new designers to participate in the contest. | |||

| P5: Verify designers | A6 | S9. The designer who wants to participate in a new type of contest or for new designers who do not have a history to submit a sample of similar designs so that the project manager can check their skill level. | |

| P6: Invite designers | A7 | S10. To communicate with designers through various communication channels, such as WhatsApp or text messages. | |

| S11. Take into account the time difference when sending invitations to designers; The project manager must check the time before sending out invitations to the designers, and an additional day can be added to the invitation if there is a significant difference in time zones before the start of the contest. | |||

| P7: Approval agreement | A8 | S12. Remind the designers that the approval agreement has not been completed and that he is not currently considered a participant in the contest. It is also a good idea to provide automated support to respond to the approval agreement through notifications or multiple communication channels, such as WhatsApp or text messages. | |

| P8: Participate in the contest | A9 | S13. Send notifications to designers about the progress of the contest or notify inactive designers to fulfill their obligation to submit designs; otherwise, they must be withdrawn to allow new designers to join the contest. | |

| P9: Validate designs and provide feedback by client. | A10 |

S14. Provide support by notifying the client to validate the designs as soon as the project manager receives the designs from designers. | |

| A11 | S15. Set constraints and obligations on the client to oblige him or her to provide feedback to the designers in the first stages of the contest in addition to browsing all the designs submitted in the first stage. | ||

| P10: Combine two designs that complement each other through feedback | A12 | S16. Provide a mechanism for communication through the platform that enables clients to provide feedback to the designers during the contest. | |

| S17. Provide a mechanism during the feedback phase that enables the client to combine two designs that complement each other. |

| D1 | D 2 | D 3 | D4 | C1 | C 2 | PM1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Experience | 3 Years | 2 Years | 1 Year | 3 Years | 2 Years | 1 Year | 2 Years |

| Job Title | Web designer and developer | Web developer | Web designer | Web designer and developer | Software company manager | Application team leader | Project Manager |

| Use of Platforms | 99designs, Upwork, Crowdsit, Freelance, Fiverr. | 99designs, Freelancer, Upwork. | 99designs, Freelance, Upwork. | Upwork, Freelancer, Fiverr. | 99designs, Upwork, Freelancer. | 99designs, Upwork, Freelancer, Fiverr. | 99designs, Upwork, Freelancer. |

| Process model | Proposed Suggestion | Comments of the interviewees | Remarks of authors |

|---|---|---|---|

|

P1: Create contest brief |

S1: It is good that a platform provides a detailed form that includes all the requirements to ensure the proper functioning of the contest (e.g., client expectations, design preferred colors, design plans). | D1: Agreed with S1, but he gave recommendations for the use of artificial intelligence technology to initially classify the contest according to specialization. |

Using artificial intelligence technology for review is a good idea, but it could be expensive for platforms. However, it can be considered in future studies. |

| D4: Agreed with S1, but he recommended that a blank box is placed in the form for any additions by the client. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model | ||

| C2: Not agreed with S1, because he believed that providing a specific form would restrict the client from adding contest requirements. | Placing a blank box in the form for any additions by the client helps to add more details and information. | ||

| S2: It is good to set constraints on the client when writing the contest brief to ensure they add all the information and details related to the contest in terms of the objectives and the expected final result from the contest and that they attach the files. | D1/C2: Not agreed with S2, because they believe that constraints placed on the client do not allow him to work freely in attaching files, and do not give complete freedom in detailing the requirements of the contest. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model so that the constraints are not mandatory but optional. | |

|

P2: Assign a project manager and Validate contest brief |

S3: It is good to automatically select the project manager based on the type of contest. | D1: Agreed with S3, but he recommended that the client could determine the need for having a project manager depending on the complexity and rating of the contest. | Having project manager is essential. The absence of a project manager for each contest leads to not obtaining the final results of the required quality. |

| D1: Agreed with S3, but made recommendations that the client can accept or reject the project manager chosen by the platform, and the client decides to appoint the project manager himself. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model so that the client can suggest a particular project manager, but his suggestion can be considered only if the chosen project manager has capacity. | ||

| S4: It is good to set constraints on capacity related to the association with contests on the project manager. | C1/C2: Agreed with S4, but suggested that a method is put in place by which the project manager selected by the platform could be approved or rejected by the client. | The suggestion was outside the scope of the limitation definition but can be considered in future studies. | |

| PM1: Not agreed with S4, he state that there is no specific mechanism to distinguish between a full-time project manager and a part-time project manager, which in turn leads to a loss of opportunity for the full-time project manager to participate in the contest. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model so that the capacity of the project managers with the contest is determined based on the mechanism of the project managers association with the contest, either full-time or part-time. | ||

|

P6: Invite designers |

S10: It is good to message designers through different communication channels, such as WhatsApp or text message. |

D4: Agreed with S10, but recommended that the communication mechanism is specified in the contest page. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model |

| PM1: Not agreed with S10, because he believes using multiple channels to communicate with designers increases the cost, in addition to more time and effort. | The opinion was not agreed on, because the process of sending notifications via WhatsApp does not require effort, and does not require an increase in cost because the cost is marginal compared to the benefit. | ||

| S11: It is good to consider the time difference when sending invitations to designers; the project manager should check the time before sending invitations to designers, and an extra day may be added to the invitation if there is a significant difference in time zones before the start of a contest. | D2: Agreed with S11, but recommended to send the invitation from 7 am to 7 pm, in order to consider the time zone differences. | In fact, adding extra day can solve the time zone differences. | |

|

P9: Validate submit designs, Browse submitted designs and Providing feedback |

S15: It is good to set constraints and obligations on the client to oblige him to provide feedback to the designers in the first stages of the contest in addition to browsing all the designs submitted in the first stage. | C1/C2: Not agreed with S15, stating that there should be no obligations on the client to give feedback on all designs. | The recommendation can be reflected in the process model so that written feedback on all designs are not mandatory, but optional. However, the client at least gives a rating to the designers, while for the designers closest to winning. |

|

P10: Providing feedback |

S17: It is good to provide a mechanism during the feedback phase that enables the client to combine two designs that complement each other. | D2/D4: Not agreed with S17, Because of designer property rights and the possibility of misunderstanding between designers. |

The idea of combining two designs serves the interest of the designers and the interest of the client so that instead of choosing one designer whose design could be incomplete, two designs are chosen that complement each other. This still preserves the property rights of each designer regarding his own design. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).