Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

22 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eisenberg, M.L.; Esteves, S.C.; Lamb, D.J.; Hotaling, J.M.; Giwercman, A.; Hwang, K.; Cheng, Y.-S. Male Infertility. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2023, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gül, M.; Russo, G.I.; Kandil, H.; Boitrelle, F.; Saleh, R.; Chung, E.; Kavoussi, P.; Mostafa, T.; Shah, R.; Agarwal, A. Male Infertility: New Developments, Current Challenges, and Future Directions. World J Mens Health 2024, 42, 502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naamneh Elzenaty, R.; du Toit, T.; Flück, C.E. Basics of Androgen Synthesis and Action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 2022, 36, 101665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, W.H. Androgen Actions in the Testis and the Regulation of Spermatogenesis. In Advances in experimental medicine and biology; Adv Exp Med Biol, 2021; Vol. 1288, pp. 175–203. [CrossRef]

- Brown, C.J.; Goss, S.J.; Lubahn, D.B.; Joseph, D.R.; Wilson, E.M.; French, F.S.; Willard, H.F. Androgen Receptor Locus on the Human X Chromosome: Regional Localization to Xq11-12 and Description of a DNA Polymorphism. Am J Hum Genet 1989, 44, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lee, X.Y.; Van Eynde, W.; Helsen, C.; Willems, H.; Peperstraete, K.; De Block, S.; Voet, A.; Claessens, F. Structural Mechanism Underlying Variations in DNA Binding by the Androgen Receptor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2024, 241, 106499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.; Kazmi, DR.S.U.; Tariq, H.; Munir, A.; Rehman, R. Association of Trinucleotide Repeat Polymorphisms CAG and GGC in Exon 1 of the Androgen Receptor Gene with Male Infertility: A Cross-Sectional Study. Turk J Med Sci 2022, 52, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyutyusheva, N.; Mancini, I.; Baroncelli, G.I.; D’Elios, S.; Peroni, D.; Meriggiola, M.C.; Bertelloni, S. Complete Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome: From Bench to Bed. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.-M.; Zhang, Y.-N.; Du, J.; Li, W.; Tu, C.-F.; Meng, L.-L.; Lin, G.; Lu, G.-X.; Tan, Y.-Q. Phenotypic and Molecular Characteristics of Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome Patients. Asian J Androl 2018, 20, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Heemers, H.; Sharifi, N. Androgen Signaling in Prostate Cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2017, 7, a030452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, A.R. La; Wilson, E.M.; Lubahn, D.B.; Harding, A.E.; Fischbeck, K.H. Androgen Receptor Gene Mutations in X-Linked Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy. Nature 1991, 352, 77–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchioretti, C.; Andreotti, R.; Zuccaro, E.; Lieberman, A.P.; Basso, M.; Pennuto, M. Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy: From Molecular Pathogenesis to Pharmacological Intervention Targeting Skeletal Muscle. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2023, 71, 102394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christin-Maitre, S.; Young, J. Androgens and Spermatogenesis. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2022, 83, 155–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mifsud, A.; Sim, C.K.S.; Boettger-Tong, H.; Moreira, S.; Lamb, D.J.; Lipshultz, L.I.; Yong, E.L. Trinucleotide (CAG) Repeat Polymorphisms in the Androgen Receptor Gene: Molecular Markers of Risk for Male Infertility. Fertil Steril 2001, 75, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nenonen, H.A.; Giwercman, A.; Hallengren, E.; Giwercman, Y.L. Non-Linear Association between Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Length and Risk of Male Subfertility - a Meta-Analysis. Int J Androl 2011, 34, 327–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, B.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wu, W.; Chen, L.; Lu, C.; Pan, F.; Ding, H.; Xia, Y.; et al. Genetic Association Between Androgen Receptor Gene CAG Repeat Length Polymorphism and Male Infertility. Medicine 2016, 95, e2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobasseri, N.; Babaei, F.; Karimian, M.; Nikzad, H. Androgen Receptor (AR)-CAG Trinucleotide Repeat Length and Idiopathic Male Infertility: A Case-Control Trial and a Meta-Analysis. EXCLI J 2018, 17, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westerveld, H.; Visser, L.; Tanck, M.; van der Veen, F.; Repping, S. CAG Repeat Length Variation in the Androgen Receptor Gene Is Not Associated with Spermatogenic Failure. Fertil Steril 2008, 89, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamberlain, N.L.; Driver, E.D.; Miesfeld, R.L. The Length and Location of CAG Trinucleotide Repeats in the Androgen Receptor N-Terminal Domain Affect Transactivation Function. Nucleic Acids Res 1994, 22, 3181–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartor, O.; Zheng, Q.; Eastham, J.A. Androgen Receptor Gene CAG Repeat Length Varies in a Race-Specific Fashion in Men without Prostate Cancer. Urology 1999, 53, 378–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhaylenko, D.S.M.; Sobol, I.Y.S.; Safronova, N.Y.S.; Simonova, O.A.S.; Efremov, E.A.E.; Efremov, G.D.E.; Alekseev, B.Y.A.; Kaprin, A.D.K.; Nemtsova, M.V.N. The Incidence of AZF Deletions, CFTR Mutations and Long Alleles of the Ar CAG Repeats during the Primary Laboratory Diagnostics in a Heterogeneous Group of Infertily Men. Urologiia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fesai, O.A.; Kravchenko, S.A.; Tyrkus, M.Ya.; Makuh, G. V.; Zinchenko, V.M.; Strelko, G. V.; Livshits, L.A. CAG Polymorphism of the Androgen Receptor Gene in Azoospermic and Oligozoospermic Men from Ukraine. Cytol Genet 2009, 43, 401–405 [In Russian]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osadchuk, L.; Vasiliev, G.; Kleshchev, M.; Osadchuk, A. Androgen Receptor Gene CAG Repeat Length Varies and Affects Semen Quality in an Ethnic-Specific Fashion in Young Men from Russia. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melikyan, L.P.; Bliznetz, E.A.; Polyakov, A. V.; Mironovich, O.L.; Kuznetsova, I.A.; Sorokina, T.M.; Shtaut, M.I.; Sedova, A.O.; Kurilo, L.F.; Solovova, O.A.; et al. Polymorphism of CAG Repeats in Exon 1 of the Androgen Receptor Gene in Russian Men with Various Forms of Pathozoospermia. Russ J Genet 2020, 56, 1000–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Zoubi, M.S.; Bataineh, H.; Rashed, M.; Al-Trad, B.; Aljabali, A.A.A.; Al-Zoubi, R.M.; Al Hamad, M.; Issam AbuAlArjah, M.; Batiha, O.; Al-Batayneh, K.M. CAG Repeats in the Androgen Receptor Gene Is Associated with Oligozoospermia and Teratozoospermia in Infertile Men in Jordan. Andrologia 2020, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharestani, S.; Mehdi Kalantar, S.; Ghasemi, N.; Farashahi Yazd, E. CAG Repeat Polymorphism in Androgen Receptor and Infertility: A Case-Control Study. Int J Reprod Biomed 2021, 19, 845–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metin Mahmutoglu, A.; Hurre Dirie, S.; Hekim, N.; Gunes, S.; Asci, R.; Henkel, R. Polymorphisms of Androgens-related Genes and Idiopathic Male Infertility in Turkish Men. Andrologia 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Kazmi, S.U.; Tariq, H.; Munir, A.; Rehman, R. Association of Trinucleotide Repeat Polymorphisms CAG and GGC in Exon 1 of the Androgen Receptor Gene with Male Infertility: A Cross-Sectional Study. Turk J Med Sci 2022, 52, 1793–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heald, A.; Cook, M.J.; Antonio, L.; Tournoy, J.; Ghaffari, P.; Mannan, F.; Fachim, H.; Vanderschueren, D.; Laing, I.; Hackett, G.; et al. Number of CAG Repeats and Mortality in Middle Aged and Older Men. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2023, 99, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi-Esfarjani, P.; Trifiro, M.A.; Pinsky, L. Evidence for a Repressive Function of the Long Polyglutamine Tract in the Human Androgen Receptor: Possible Pathogenetic Relevance for the (CAG)n-Expanded Neuronopathies. Hum Mol Genet 1995, 4, 523–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tut, T.G.; Ghadessy, F.J.; Trifiro, M.A.; Pinsky, L.; Yong, E.L. Long Polyglutamine Tracts in the Androgen Receptor Are Associated with Reduced Trans-Activation, Impaired Sperm Production, and Male Infertility. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997, 82, 3777–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beilin, J.; Ball, E.; Favaloro, J.; Zajac, J. Effect of the Androgen Receptor CAG Repeat Polymorphism on Transcriptional Activity: Specificity in Prostate and Non-Prostate Cell Lines. J Mol Endocrinol 2000, 25, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heemers, H. V.; Tindall, D.J. Androgen Receptor (AR) Coregulators: A Diversity of Functions Converging on and Regulating the AR Transcriptional Complex. Endocr Rev 2007, 28, 778–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertelli, M.A.; Scheller, A.; Brogley, M.; Robins, D.M. Replacing the Mouse Androgen Receptor with Human Alleles Demonstrates Glutamine Tract Length-Dependent Effects on Physiology and Tumorigenesis in Mice. Mol Endocrinol 2006, 20, 1248–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheppard, R.L.; Spangenburg, E.E.; Chin, E.R.; Roth, S.M. Androgen Receptor Polyglutamine Repeat Length Affects Receptor Activity and C2C12 Cell Development. Physiol Genomics 2011, 43, 1135–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibañez, K.; Jadhav, B.; Zanovello, M.; Gagliardi, D.; Clarkson, C.; Facchini, S.; Garg, P.; Martin-Trujillo, A.; Gies, S.J.; Galassi Deforie, V.; et al. Increased Frequency of Repeat Expansion Mutations across Different Populations. Nat Med 2024. [CrossRef]

- Bellai, D.J.; Rae, M.G. A Systematic Review of the Association between the Age of Onset of Spinal Bulbar Muscular Atrophy (Kennedy’s Disease) and the Length of CAG Repeats in the Androgen Receptor Gene. eNeurologicalSci 2024, 34, 100495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laskaratos, A.; Breza, M.; Karadima, G.; Koutsis, G. Wide Range of Reduced Penetrance Alleles in Spinal and Bulbar Muscular Atrophy: A Model-Based Approach. J Med Genet 2021, 58, 385–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanovello, M.; Ibáñez, K.; Brown, A.-L.; Sivakumar, P.; Bombaci, A.; Santos, L.; van Vugt, J.J.F.A.; Narzisi, G.; Karra, R.; Scholz, S.W.; et al. Unexpected Frequency of the Pathogenic AR CAG Repeat Expansion in the General Population. Brain 2023, 146, 2723–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen, 5th ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010; 271p. [Google Scholar]

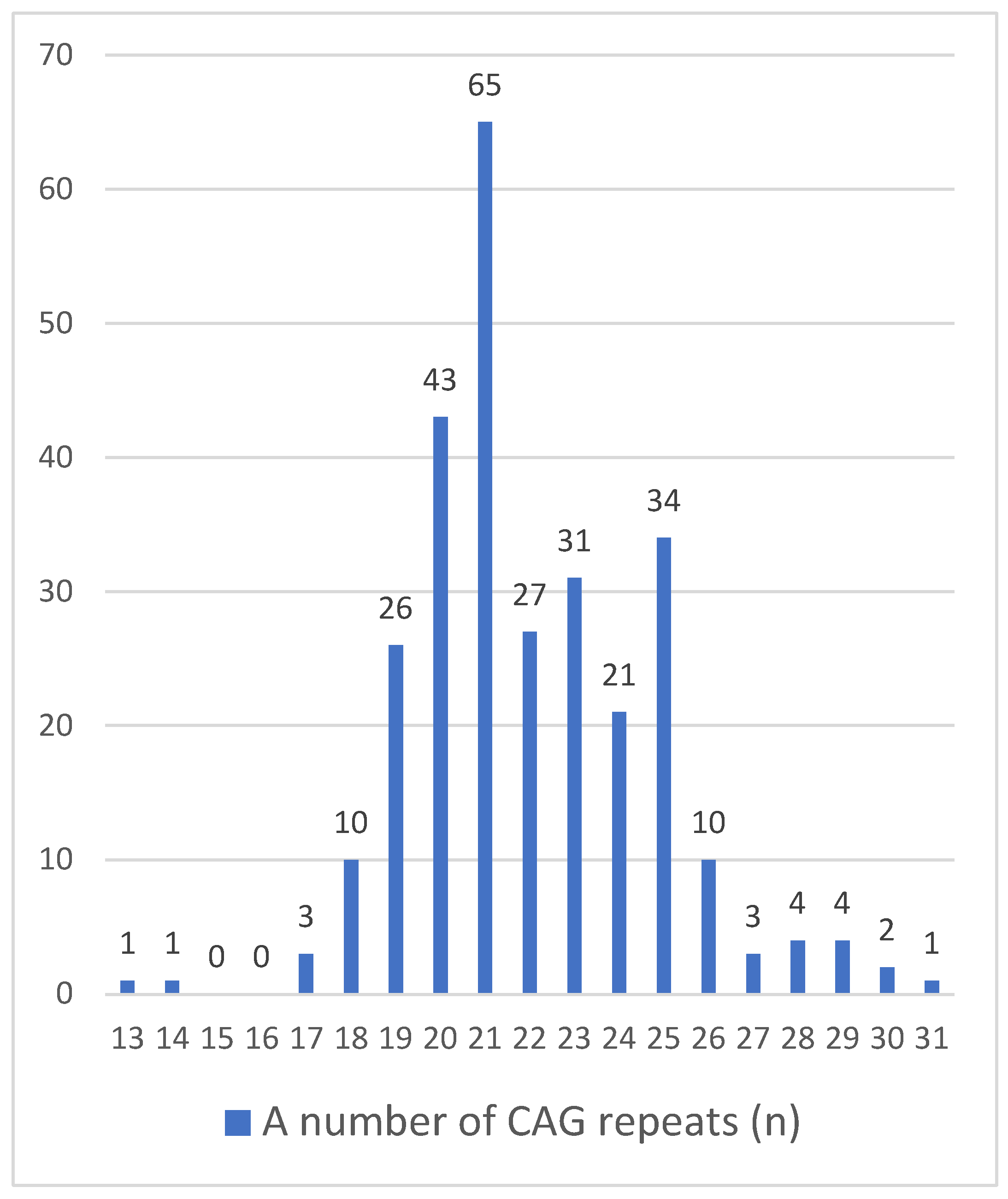

| Variants of the CAGn* polymorphic locus of the androgen receptor (AR) gene | Number of patients, allele frequency (AF) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Russian infertile men (n=9000) | Russian fertile men (n=286) | ||

| 16 | 99 (0.0110) | - | - |

| 17 | 132 (0.0147) | 3 (0.0105) | 0.742 |

| 18 | 359 (0.0399) | 10 (0.0350) | 0.675 |

| 19 | 747 (0.0830) | 26 (0.0909) | 0.634 |

| 20 | 1088 (0.1209) | 43 (0.1450) | 0.134 |

| 21 | 1528 (0.1698) | 65 (0.2273) | 0.012 |

| 22 | 1051 (0.1168) | 27 (0.0944) | 0.245 |

| 23 | 1074 (0.1193) | 31 (0.1084) | 0.574 |

| 24 | 1028 (0.1142) | 21 (0.0734) | 0.032 |

| 25 | 670 (0.0744) | 34 (0.1189) | 0.006 |

| 26 | 442 (0.0491) | 10 (0.0350) | 0.274 |

| 27 | 221 (0.0246) | 3 (0.0105) | 0.184 |

| 28 | 158 (0.0176) | 4 (0.0140) | 0.823 |

| 29 | 137 (0.0152) | 4 (0.0140) | 0.939 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).