Submitted:

21 October 2024

Posted:

21 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Pfizer BNT162b4: Pfizer’s vaccine candidate BNT162b4 (an mRNA vaccine encoding segments of the N and M proteins, and short segments from the ORF1ab polyprotein), developed to enhance T-cell responses against conserved non-spike antigens of SARS-CoV-2, encodes conserved, immunogenic segments of the nucleocapsid, membrane, and ORF1ab proteins targeting diverse HLA alleles. BNT162b4 elicits robust CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to a wide array of epitopes in preclinical animal models, while preserving spike-specific immunity. Notably, BNT162b4 has been shown to protect animal models from severe disease and reduce viral loads following infection with various SARS-CoV-2 variants [147].

- Gritstone GRT-R910. GRT-R910 is an investigational vaccine that was designed to enhance the immunogenicity and protective efficacy against the current and future SARS-CoV-2 VOC. A randomized, double-blinded Phase 2b study has being conducted to assess the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of Gritstone bio’s next-generation COVID-19 vaccine candidate compared to an approved COVID-19 vaccine. Gritstone’s vaccine incorporates a self-replicating mRNA, encoding viral antigens, including both Spike protein (as seen in first-generation COVID-19 vaccines) and conserved non-Spike CD8 epitopes aimed at eliciting T-cell responses [93].

- OVX033 from Osivax: A protein subunit vaccine, aiming to protect against sarbecoviruses, the subgroup of coronaviruses from which SARS viruses come from. The vaccine contains the full-length nucleocapsid antigen of SARS-CoV-2 which is genetically fused to the self-assembling sequence OVX313, which is a “55-amino acids sequence, hybrid of the C-terminal fragments of two avian C4bp α-chain sequences, that naturally oligomerizes into heptamers.” The OVX033 aims to target the nucleocapsid (N) protein within SARS-CoV-2, which is highly conserved among the Sarbecoviruses [148]. OVX033 was tested either unadjuvanted or formulated with a squalene-in-water emulsion containing cholesterol and QS21 saponin [148]. After evaluating the efficiency of the OVX033 vaccine using a hamster model of SARS-CoV-2 infection, the vaccine proved effective against 3 different SARS-CoV-2 variants of concerns as seen through significant decrease in weight loss, lung viral loads, inflammation, lymphoplasmacytic perivascular infiltration, and pneumonia incidence. The vaccine also showed improved immunogenicity as T-cell responses were triggered within the hamsters due to the vaccine. These sufficient results supported further evaluation of the vaccine within human trials. Currently, participants are being recruited in Paris to test the safety and immunogenicity of three dosages – they’re aiming for 48 participants.

- PanCoV from LinkInVax, developed by INSERM: A protein subunit vaccine aiming at sarbecoviruses. It was developed by INSERM, the French national health agency similar to the US NIH. The vaccine targets “the RBD of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to the CD40 receptor” and includes “T- and B-cell epitopes spanning sequences from S and nucleocapsid (N) proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and highly homologous to 38 sarbecoviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 VOCs [149].” The vaccine was successful at eliciting SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein-specific IgG switched human B cells with a single injection adjuvanted with polyinosinic-polycytidylic acid [149]. There was also evidence of inducing human B-cell and T-cell responses in the humanized mice. Studies in Macaques demonstrated a “blockade” of new cell infections, the destruction of infected cells, and improved protection against SARS-CoV-2 reinfection [149,150] without the need for an adjuvant. Currently, a combined phase 1 and 2 trials has been registered to test this vaccine, with and without an adjuvant. They aim to recruit 240 people.

- CalTech: The California Institute of Technology (CalTech) is developing a Mosaic vaccine utilizing nanoparticles that display 60 randomly organized spike receptor-binding domains (RBDs) originated from the spike trimers of eight distinct sarbecoviruses (mosaic-8 RBD nanoparticles). The Mosaic-8b vaccine is designed to produce antibodies targeting against conserved and relatively hidden epitopes, as opposed to the more commonly targeted, variable, and prominently exposed epitopes. This vaccine includes RBDs from eight SARS-like betacoronaviruses (sarbecoviruses) that encompasses the RBD from the currently prevalent SARS-CoV-2 virus along with RBDs from seven other animal sarbecoviruses. This diverse RBD representation is intended to provide broad-spectrum protection against a variety of related viruses. Preclinical studies have demonstrated that immunization with mosaic-8 nanoparticles elicited anti-coronavirus antibodies with robust neutralizing capabilities and effectiveness against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the highly transmissible Omicron variant. Furthermore, the vaccination conferred protection against both SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV infections in mouse and nonhuman primate [151,152].

- DIOSynVax: Cambridge University spin-off DIOSynVax (Digitally Immune Optimized Synthetic Vaccines) is utilizing a highly advanced approach in vaccine development. In collaboration with PharmaJet, they have introduced pEVAC-PS, a needle-free intradermal vaccine encoding their synthetic antigen T2_17, designed based on coronavirus receptor binding domain (RBD) sequences [153]. DIOSynVax employs a viral-genome-informed methodology to generate an antigen sequence that phylogenetically aligns with representative sequences from all known sarbecoviruses, ensuring the retention of key antibody epitopes. This synthetic antigen has been evaluated across multiple platforms, including DNA, Modified Vaccinia Ankara (MVA), and mRNA. The antigen has elicited cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies against Delta and Omicron and other tested sarbecoviruses in preclinical studies different animal models [153].

- VBI Vaccines (USA, Canada): VBI Vaccines is developing vaccines that emulate the natural presentation of viruses to stimulate innate immune responses, leveraging their proprietary enveloped virus-like particle (eVLP) technology. Utilizing this technology, VBI designed VBI-2901, a vaccine that expresses a modified prefusion form of spike proteins from SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV-1, and MERS-CoV. In preclinical studies, mice immunized with VBI-2901 exhibited a potent neutralizing response against all variants tested, including Bat RaTG13. VBI-2901 elicited a 2.5-fold stronger response to the ancestral strain and a ninefold stronger response against the bat coronavirus when compared to the VBI-2902 vaccine ( containing only the ancestral Wuhan-Hu-1 spike protein) [154]. VBI-2901 is currently being evaluated in Phase I clinical trials.

- Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR, USA): The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) has engineered a recombinant spike ferritin nanoparticle (SpFN) vaccine for SARS-CoV-2 WA-1, in combination with the Army Liposomal Formulation (ALFQ) adjuvant, which includes monophosphoryl lipid A and QS-21 (SpFN/ALFQ). This self-assembling ferritin nanoparticle is designed to present eight prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 WA-1 spike glycoprotein trimers in an ordered and symmetrical fashion. The SpFN vaccine is paired with a unilamellar liposomal adjuvant that incorporates monophosphoryl lipid A and the saponin QS-21 (ALFQ), reputed for its ability to enhance the immunogenicity of various protein vaccine candidates and its favorable tolerance in human trials. This immunogen-adjuvant combination has demonstrated the capacity to elicit broad immunity against sarbecoviruses and confer protection against SARS-CoV-2 in preclinical models [155].

Challenges and Future Directions

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

References

- Prakash, S. , et al., Genome-Wide Asymptomatic B-Cell, CD4 (+) and CD8 (+) T-Cell Epitopes, that are Highly Conserved Between Human and Animal Coronaviruses, Identified from SARS-CoV-2 as Immune Targets for Pre-Emptive Pan-Coronavirus Vaccines. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Coulon, P.-G. , et al., High frequencies of alpha common cold coronavirus/SARS-CoV-2 cross-reactive functional CD4+ and CD8+ memory T cells are associated with protection from symptomatic and fatal SARS-CoV-2 infections in unvaccinated COVID-19 patients. Frontiers in Immunology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jackson, L.A. , et al., An mRNA Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1920–1931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishimaru, H. , et al., Epitopes of an antibody that neutralizes a wide range of SARS-CoV-2 variants in a conserved subdomain 1 of the spike protein. J Virol 2024, e0041624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magazine, N. , et al., Immune Epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and Considerations for Universal Vaccine Development. Immunohorizons 2024, 8, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, T.J.C. , et al., Evidence of antigenic drift in the fusion machinery core of SARS-CoV-2 spike. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2317222121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, S. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 spike-reactive naive B cells and pre-existing memory B cells contribute to antibody responses in unexposed individuals after vaccination. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1355949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanunliong, G. , et al., Persistence of Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies in Long Term Care Residents Over Seven Months After Two COVID-19 Outbreaks. Front Immunol 2021, 12, 775420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, T. , et al., Vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants and future pandemics. Expert Rev Vaccines 2022, 21, 1363–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdocca, M. , et al., Peptide Platform as a Powerful Tool in the Fight against COVID-19. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farlow, A. , et al., The Future of Epidemic and Pandemic Vaccines to Serve Global Public Health Needs. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A.M. , et al., Circulating cancer giant cells with unique characteristics frequently found in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS). Med Oncol 2023, 40, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghban, R., A. Ghasemian, and S. Mahmoodi, Nucleic acid-based vaccine platforms against the coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19). Arch Microbiol 2023, 205, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amano, T. , et al., Controllable self-replicating RNA vaccine delivered intradermally elicits predominantly cellular immunity. iScience 2023, 26, 106335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amano, T. , et al., Controllable self-replicating RNA vaccine delivered intradermally elicits predominantly cellular immunity. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelaziz, M.O. , et al., Early protective effect of a (“pan”) coronavirus vaccine (PanCoVac) in Roborovski dwarf hamsters after single-low dose intranasal administration. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1166765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keech, C. , et al., Phase 1-2 Trial of a SARS-CoV-2 Recombinant Spike Protein Nanoparticle Vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 2320–2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francica, J.R. , et al., Vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein and AS03 Adjuvant Induces Rapid Anamnestic Antibodies in the Lung and Protects Against Virus Challenge in Nonhuman Primates. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kyriakidis, N.C. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 vaccines strategies: a comprehensive review of phase 3 candidates. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goepfert, P.A. , et al., Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 recombinant protein vaccine formulations in healthy adults: interim results of a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 1-2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Infect Dis 2021, 21, 1257–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleanthous, H. , et al., Scientific rationale for developing potent RBD-based vaccines targeting COVID-19. NPJ Vaccines 2021, 6, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimmiraju, S.R. , et al., A trivalent protein-based pan-Betacoronavirus vaccine elicits cross-neutralizing antibodies against a panel of coronavirus pseudoviruses. NPJ Vaccines 2024, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

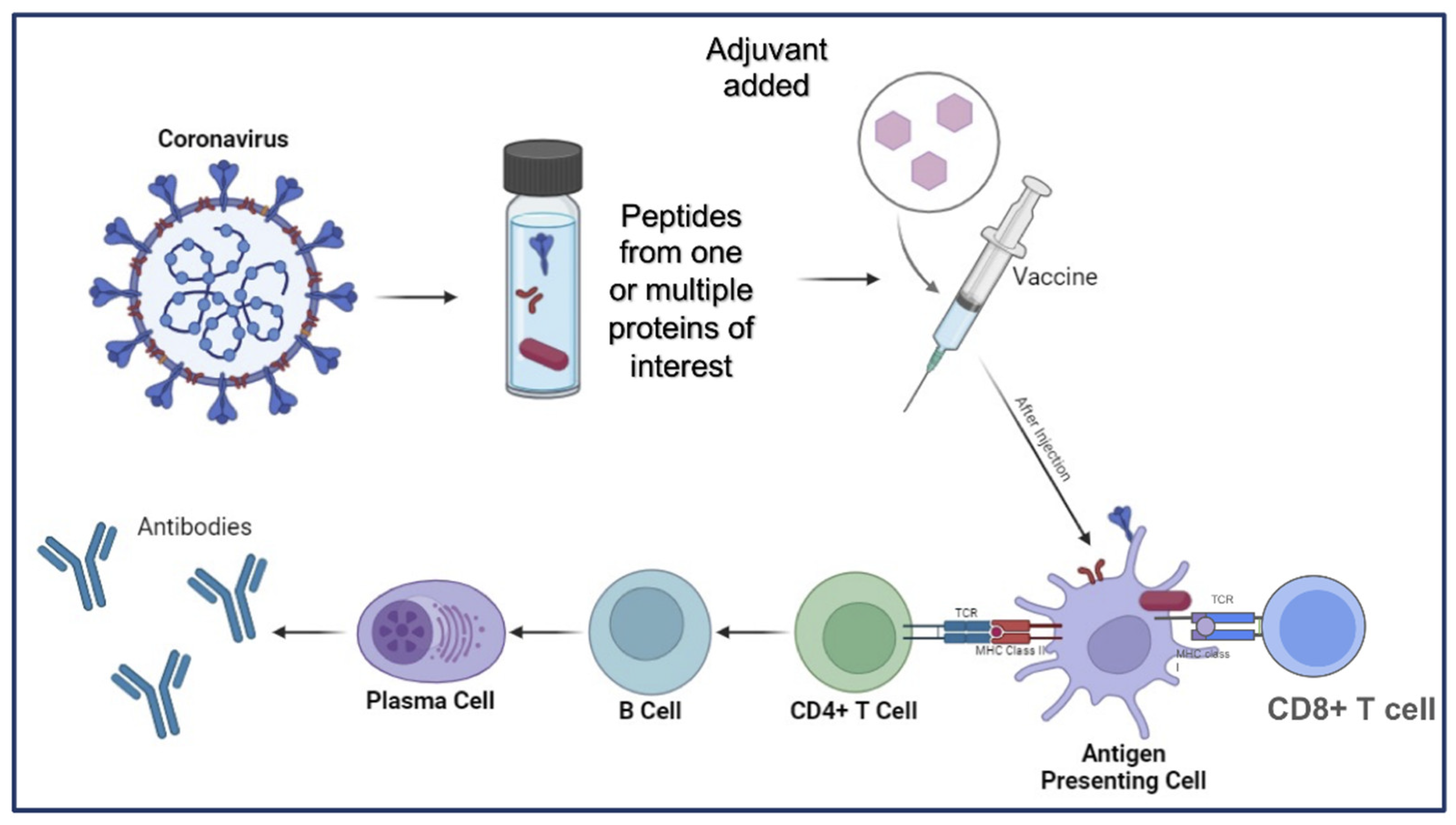

- Shalash, A.O. , et al., Peptide-Based Vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: Peptide Antigen Discovery and Screening of Adjuvant Systems. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skwarczynski, M. and I. Toth, Recent advances in peptide-based subunit nanovaccines. Nanomedicine (Lond) 2014, 9, 2657–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagwe, P.V. , et al., Peptide-Based Vaccines and Therapeutics for COVID-19. Int J Pept Res Ther 2022, 28, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cankat, S., M. U. Demael, and L. Swadling, In search of a pan-coronavirus vaccine: next-generation vaccine design and immune mechanisms. Cell Mol Immunol 2024, 21, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, C.W. , et al., Broad-spectrum pan-genus and pan-family virus vaccines. Cell Host Microbe 2023, 31, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

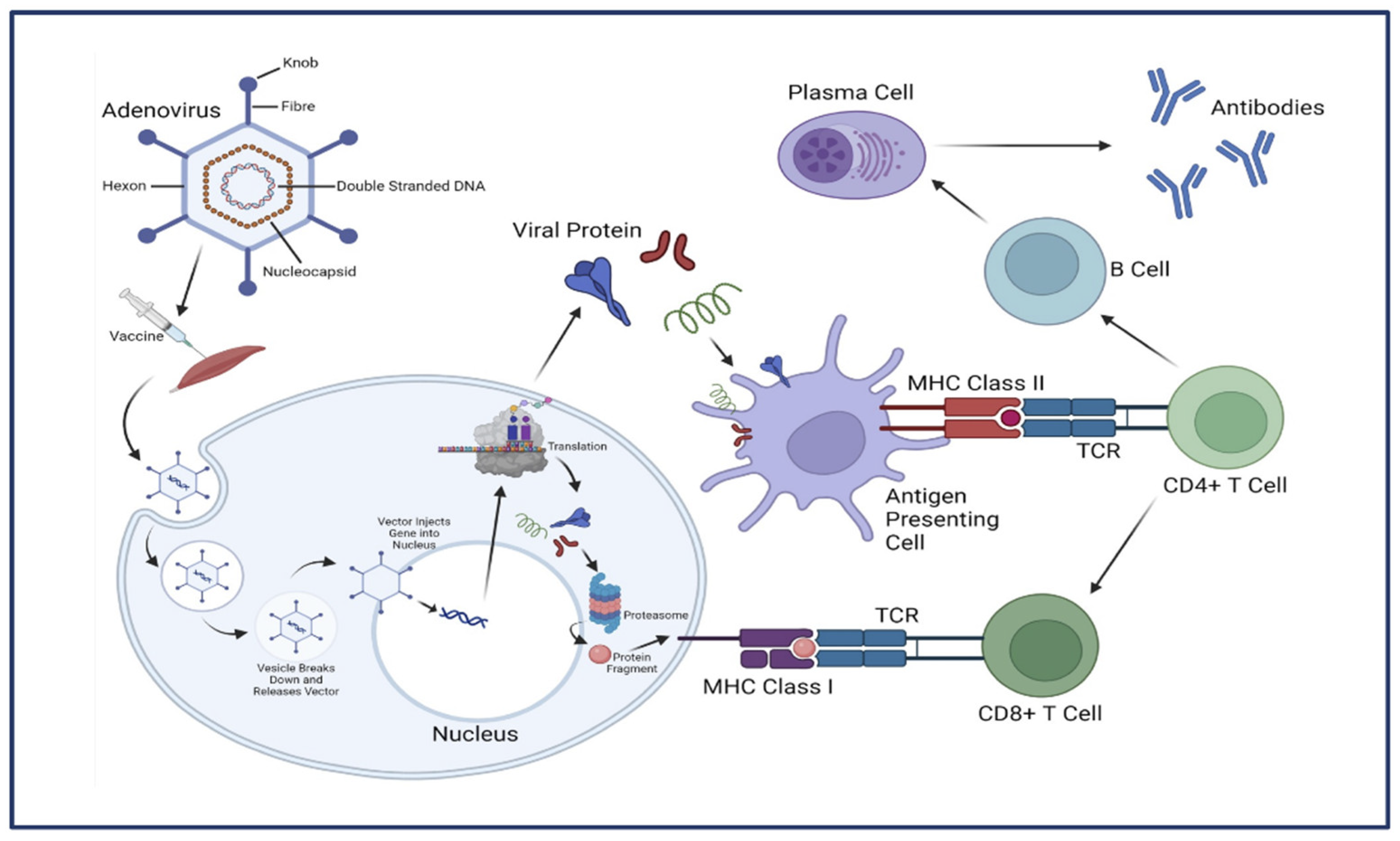

- Lee, C.S. , et al., Adenovirus-Mediated Gene Delivery: Potential Applications for Gene and Cell-Based Therapies in the New Era of Personalized Medicine. Genes Dis 2017, 4, 43–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crystal, R.G. , Adenovirus: the first effective in vivo gene delivery vector. Hum Gene Ther 2014, 25, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukashev, A.N. and A.A. Zamyatnin, Jr., Viral Vectors for Gene Therapy: Current State and Clinical Perspectives. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2016, 81, 700–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coughlan, L. , Factors Which Contribute to the Immunogenicity of Non-replicating Adenoviral Vectored Vaccines. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ewer, K. , et al., Chimpanzee adenoviral vectors as vaccines for outbreak pathogens. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017, 13, 3020–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghebremedhin, B. , Human adenovirus: Viral pathogen with increasing importance. Eur J Microbiol Immunol (Bp) 2014, 4, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- See, R.H. , et al., Comparative evaluation of two severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) vaccine candidates in mice challenged with SARS coronavirus. J Gen Virol 2006, 87, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E. , et al., COVID-19 Coronavirus Vaccine Design Using Reverse Vaccinology and Machine Learning. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, E. , et al., COVID-19 coronavirus vaccine design using reverse vaccinology and machine learning. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chavda, V.P., R. Pandya, and V. Apostolopoulos, DNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-2: toward third-generation vaccination era. Expert Rev Vaccines 2021, 20, 1549–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L. , et al., The SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein Biosynthesis, Structure, Function, and Antigenicity: Implications for the Design of Spike-Based Vaccine Immunogens. Front Immunol 2020, 11, 576622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. and Q. Ye, Safety and Efficacy of the Common Vaccines against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Folegatti, P.M. , et al., Safety and immunogenicity of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: a preliminary report of a phase 1/2, single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. and R.J. Samulski, Engineering adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Nat Rev Genet 2020, 21, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , et al., Novel AAV-based genetic vaccines encoding truncated dengue virus envelope proteins elicit humoral immune responses in mice. Microbes Infect 2012, 14, 1000–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, F. , et al., Novel adeno-associated virus-based genetic vaccines encoding hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein elicit humoral immune responses in mice. Mol Med Rep 2019, 19, 1016–1023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lin, J. , et al., A new genetic vaccine platform based on an adeno-associated virus isolated from a rhesus macaque. J Virol 2009, 83, 12738–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabaleta, N. , et al., An AAV-based, room-temperature-stable, single-dose COVID-19 vaccine provides durable immunogenicity and protection in non-human primates. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29, 1437–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F. , et al., Single-shot AAV-vectored vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 with fast and long-lasting immunity. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2219–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woldemeskel, B.A. , et al., CD4+ T cells from COVID-19 mRNA vaccine recipients recognize a conserved epitope present in diverse coronaviruses. J Clin Invest 2022, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pack, S.M. and P.J. Peters, SARS-CoV-2-Specific Vaccine Candidates; the Contribution of Structural Vaccinology. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Longet, S. , et al., mRNA vaccination drives differential mucosal neutralizing antibody profiles in naive and SARS-CoV-2 previously-infected individuals. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 953949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.L. , et al., Loss of Pfizer (BNT162b2) Vaccine-Induced Antibody Responses against the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variant in Adolescents and Adults. J Virol 2022, 96, e0058222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, L. , Advances in mRNA-Based Cancer Vaccines. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iavarone, C. , et al., Mechanism of action of mRNA-based vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines 2017, 16, 871–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Pilipich, N. , et al., Self-Amplifying RNA: A Second Revolution of mRNA Vaccines against COVID-19. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J. , et al., Circular RNA: A promising new star of vaccine. J Transl Int Med 2023, 11, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, E.A. , et al., A self-amplifying RNA vaccine against COVID-19 with long-term room-temperature stability. NPJ Vaccines 2022, 7, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhardt, A. , et al., A flexible, thermostable nanostructured lipid carrier platform for RNA vaccine delivery. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2022, 25, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, J. , et al., Recent advances in nanoparticulate RNA delivery systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2024, 121, e2307798120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhiz, H., E. N. Atochina-Vasserman, and D. Weissman, mRNA-based therapeutics: looking beyond COVID-19 vaccines. Lancet 2024, 403, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalski, P.S. , et al., Delivering the Messenger: Advances in Technologies for Therapeutic mRNA Delivery. Mol Ther 2019, 27, 710–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahin, U., K. Kariko, and O. Tureci, mRNA-based therapeutics--developing a new class of drugs. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 759–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenchov, R. , et al., Lipid Nanoparticles horizontal line From Liposomes to mRNA Vaccine Delivery, a Landscape of Research Diversity and Advancement. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16982–17015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harashima, H. , et al., Enhanced hepatic uptake of liposomes through complement activation depending on the size of liposomes. Pharm Res 1994, 11, 402–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagayasu, A. Uchiyama, and H. Kiwada, The size of liposomes: a factor which affects their targeting efficiency to tumors and therapeutic activity of liposomal antitumor drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 1999, 40, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oberli, M.A. , et al., Lipid Nanoparticle Assisted mRNA Delivery for Potent Cancer Immunotherapy. Nano Lett 2017, 17, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X. , et al., Lipid nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Nat Rev Mater 2021, 6, 1078–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magini, D. , et al., Self-Amplifying mRNA Vaccines Expressing Multiple Conserved Influenza Antigens Confer Protection against Homologous and Heterosubtypic Viral Challenge. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0161193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, A.B. , et al., Self-Amplifying RNA Vaccines Give Equivalent Protection against Influenza to mRNA Vaccines but at Much Lower Doses. Mol Ther 2018, 26, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, K., F. van den Berg, and P. Arbuthnot, Self-amplifying RNA vaccines for infectious diseases. Gene Ther 2021, 28, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakney, A.K., S. Ip, and A.J. Geall, An Update on Self-Amplifying mRNA Vaccine Development. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R. , et al., A comprehensive review of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: Pfizer, Moderna & Johnson & Johnson. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022, 18, 2002083. [Google Scholar]

- Rabaan, A.A. , et al., A Comprehensive Review on the Current Vaccines and Their Efficacies to Combat SARS-CoV-2 Variants. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Pegu, A. , et al., Durability of mRNA-1273 vaccine-induced antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science 2021, 373, 1372–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, T.R. , et al., Development of CRISPR as an Antiviral Strategy to Combat SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza. Cell 2020, 181, 865–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, M. and L. Song, Novel antibody epitopes dominate the antigenicity of spike glycoprotein in SARS-CoV-2 compared to SARS-CoV. Cell Mol Immunol 2020, 17, 536–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walls, A.C. , et al., Structure, Function, and Antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein. Cell 2020, 181, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilocca, B. , et al., Molecular basis of COVID-19 relationships in different species: a one health perspective. Microbes Infect 2020, 22, 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetro, J.A. , Is COVID-19 receiving ADE from other coronaviruses? Microbes Infect 2020, 22, 72–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grifoni, A. , et al., A Sequence Homology and Bioinformatic Approach Can Predict Candidate Targets for Immune Responses to SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe 2020, 27, 671–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, M. , et al., Development of epitope-based peptide vaccine against novel coronavirus 2019 (SARS-COV-2): Immunoinformatics approach. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.F. A. Quadeer, and M.R. McKay, Preliminary Identification of Potential Vaccine Targets for the COVID-19 Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) Based on SARS-CoV Immunological Studies. Viruses 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhard, P. and D.E. Lanar, Malaria vaccine based on self-assembling protein nanoparticles. Expert Rev Vaccines 2015, 14, 1525–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doll, T.A. , et al., Optimizing the design of protein nanoparticles as carriers for vaccine applications. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 1705–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bissati, K. , et al., Effectiveness of a novel immunogenic nanoparticle platform for Toxoplasma peptide vaccine in HLA transgenic mice. Vaccine 2014, 32, 3243–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bissati, K. , et al., Protein nanovaccine confers robust immunity against Toxoplasma. NPJ Vaccines 2017, 2, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q. , et al., Expression, purification and refolding of a self-assembling protein nanoparticle (SAPN) malaria vaccine. Methods 2013, 60, 242–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, S.A. , et al., A nonadjuvanted polypeptide nanoparticle vaccine confers long-lasting protection against rodent malaria. J Immunol 2009, 183, 7268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, S.A. , et al., Self-assembling protein nanoparticles with built-in flagellin domains increases protective efficacy of a Plasmodium falciparum based vaccine. Vaccine 2018, 36, 906–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaba, S.A. , et al., Protective antibody and CD8+ T-cell responses to the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein induced by a nanoparticle vaccine. PLoS One 2012, 7, e48304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karch, C.P. , et al., The use of a P. falciparum specific coiled-coil domain to construct a self-assembling protein nanoparticle vaccine to prevent malaria. J Nanobiotechnology 2017, 15, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.E. , et al., Mechanisms of protective immune responses induced by the Plasmodium falciparum circumsporozoite protein-based, self-assembling protein nanoparticle vaccine. Malar J 2013, 12, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seth, L. , et al., Development of a self-assembling protein nanoparticle vaccine targeting Plasmodium falciparum Circumsporozoite Protein delivered in three Army Liposome Formulation adjuvants. Vaccine 2017, 35, 5448–5454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prakash, S. , et al., Cross-protection induced by highly conserved human B, CD4(+), and CD8(+) T-cell epitopes-based vaccine against severe infection, disease, and death caused by multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern. Front Immunol 2024, 15, 1328905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palmer, C.D. , et al., GRT-R910: a self-amplifying mRNA SARS-CoV-2 vaccine boosts immunity for >/=6 months in previously-vaccinated older adults. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, N.T. , et al., Safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of the self-amplifying mRNA ARCT-154 COVID-19 vaccine: pooled phase 1, 2, 3a and 3b randomized, controlled trials. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 4081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- First self-amplifying mRNA vaccine approved. Nat Biotechnol 2024, 42, 4.

- Chen, R. , et al., Engineering circular RNA for enhanced protein production. Nat Biotechnol 2023, 41, 262–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft, R.A. , et al., RNA Circularization Diminishes Immunogenicity and Can Extend Translation Duration In Vivo. Mol Cell 2019, 74, 508–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, J. , et al., What goes around comes around: Artificial circular RNAs bypass cellular antiviral responses. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2022, 28, 623–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselhoeft, R.A., P. S. Kowalski, and D.G. Anderson, Engineering circular RNA for potent and stable translation in eukaryotic cells. Nat Commun 2018, 9, 2629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enuka, Y. , et al., Circular RNAs are long-lived and display only minimal early alterations in response to a growth factor. Nucleic Acids Res 2016, 44, 1370–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memczak, S. , et al., Circular RNAs are a large class of animal RNAs with regulatory potency. Nature 2013, 495, 333–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, L. , et al., Circular RNA vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 and emerging variants. Cell 2022, 185, 1728–1744.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoenmaker, L. , et al., mRNA-lipid nanoparticle COVID-19 vaccines: Structure and stability. Int J Pharm 2021, 601, 120586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guan, S. and J. Rosenecker, Nanotechnologies in delivery of mRNA therapeutics using nonviral vector-based delivery systems. Gene Ther 2017, 24, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, K.J. , et al., Optimization of Lipid Nanoparticles for Intramuscular Administration of mRNA Vaccines. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 2019, 15, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumru, O.S. , et al., Vaccine instability in the cold chain: mechanisms, analysis and formulation strategies. Biologicals 2014, 42, 237–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. and D. Zehrung, Desirable attributes of vaccines for deployment in low-resource settings. J Pharm Sci 2013, 102, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crommelin, D.J.A. , et al., Addressing the Cold Reality of mRNA Vaccine Stability. J Pharm Sci 2021, 110, 997–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.S. , et al., mRNA-based vaccines and therapeutics: an in-depth survey of current and upcoming clinical applications. J Biomed Sci 2023, 30, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichmuth, A.M. , et al., mRNA vaccine delivery using lipid nanoparticles. Ther Deliv 2016, 7, 319–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, K. , et al., Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Mol Ther 2017, 25, 1316–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahl, K. , et al., Preclinical and Clinical Demonstration of Immunogenicity by mRNA Vaccines against H10N8 and H7N9 Influenza Viruses. Mol Ther 2022, 30, 2874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P. , et al., Long-term storage of lipid-like nanoparticles for mRNA delivery. Bioact Mater 2020, 5, 358–363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stitz, L. , et al., A thermostable messenger RNA based vaccine against rabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2017, 11, e0006108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.N. , et al., A Thermostable mRNA Vaccine against COVID-19. Cell 2020, 182, 1271–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S. , et al., Structure-based design of peptides that self-assemble into regular polyhedral nanoparticles. Nanomedicine 2006, 2, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Sagaseta, J. , et al., Self-assembling protein nanoparticles in the design of vaccines. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2016, 14, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hernandez, S., N. Ugidos-Damboriena, and J. Lopez-Sagaseta, Self-Assembling Protein Nanoparticles in the Design of Vaccines: 2022 Update. Vaccines (Basel) 2022, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, K. , et al., Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and Influenza Coinfection and Clinical Characteristics Among Children and Adolescents Aged <18 Years Who Were Hospitalized or Died with Influenza - United States, 2021-22 Influenza Season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2022, 71, 1589–1596. [Google Scholar]

- Karch, C.P. , et al., Production of E. coli-expressed Self-Assembling Protein Nanoparticles for Vaccines Requiring Trimeric Epitope Presentation. J Vis Exp 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y. , et al., The biodistribution of self-assembling protein nanoparticles shows they are promising vaccine platforms. J Nanobiotechnology 2013, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tinkle, S. , et al., Nanomedicines: Addressing the Scientific and Regulatory Gap. Handbook of Clinical Nanomedicine: Law, Business, Regulation, Safety, and Risk 2016, 2, 413–470. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, P. , et al., pH-Triggered Size-Transformable and Bioactivity-Switchable Self-Assembling Chimeric Peptide Nanoassemblies for Combating Drug-Resistant Bacteria and Biofilms. Advanced Materials 2023, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, Y.S., Q. Luo, and J.Q. Liu, Protein self-assembly supramolecular strategies. Chemical Society Reviews 2016, 45, 2756–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundahl, M.L.E. , et al., Aggregation of protein therapeutics enhances their immunogenicity: causes and mitigation strategies. Rsc Chemical Biology 2021, 2, 1004–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Hernández, S., N. Ugidos-Damboriena, and J. López-Sagaseta, Self-Assembling Protein Nanoparticles in the Design of Vaccines: 2022 Update. Vaccines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, K., J. M. Zhuang, and S. Thayumanavan, Templated self-assembly of a covalent polymer network for intracellular protein delivery and traceless release. Abstracts of Papers of the American Chemical Society 2018, 256. [Google Scholar]

- Tapia, D., A. Reyes-Sandoval, and J.I. Sanchez-Villamil, Protein-based Nanoparticle Vaccine Approaches Against Infectious Diseases. Archives of Medical Research 2023, 54, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, E., H. Shen, and M. Ferrari, Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nature Biotechnology 2015, 33, 941–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkovich, N. , et al., Advancements in protein nanoparticle vaccine platforms to combat infectious disease. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews-Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S. , et al., Viruses from poultry and livestock pose continuous threats to human beings. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, C.E. , et al., Swine acute diarrhea syndrome coronavirus replication in primary human cells reveals potential susceptibility to infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117, 26915–26925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y. , et al., Functional and genetic analysis of viral receptor ACE2 orthologs reveals a broad potential host range of SARS-CoV-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2021, 118. [Google Scholar]

- Koff, W.C. and S.F. Berkley, A universal coronavirus vaccine. Science 2021, 371, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giurgea, L.T., A. Han, and M.J. Memoli, Universal coronavirus vaccines: the time to start is now. NPJ Vaccines 2020, 5, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morens, D.M., J. K. Taubenberger, and A.S. Fauci, Universal Coronavirus Vaccines - An Urgent Need. N Engl J Med 2022, 386, 297–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S. , et al., Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 (previously 2019-nCoV) infection by a highly potent pan-coronavirus fusion inhibitor targeting its spike protein that harbors a high capacity to mediate membrane fusion. Cell Res 2020, 30, 343–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vithani, N. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 Nsp16 activation mechanism and a cryptic pocket with pan-coronavirus antiviral potential. Biophys J 2021, 120, 2880–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sewell, A.K. , Why must T cells be cross-reactive? Nat Rev Immunol 2012, 12, 669–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarke, A. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 vaccination induces immunological T cell memory able to cross-recognize variants from Alpha to Omicron. Cell 2022, 185, 847–859.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeton, R. , et al., Author Correction: T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike cross-recognize Omicron. Nature 2022, 604, E25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeton, R. , et al., T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 spike cross-recognize Omicron. Nature 2022, 603, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y. , et al., Ancestral SARS-CoV-2-specific T cells cross-recognize the Omicron variant. Nat Med 2022, 28, 472–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flament, H. , et al., Outcome of SARS-CoV-2 infection is linked to MAIT cell activation and cytotoxicity. Nat Immunol 2021, 22, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolton, G. , et al., Emergence of immune escape at dominant SARS-CoV-2 killer T cell epitope. Cell 2022, 185, 2936–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, T.I. , et al., The impact of viral mutations on recognition by SARS-CoV-2 specific T cells. iScience 2021, 24, 103353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arieta, C.M. , et al., The T-cell-directed vaccine BNT162b4 encoding conserved non-spike antigens protects animals from severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell 2023, 186, 2392–2409.e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Primard, C. , et al., OVX033, a nucleocapsid-based vaccine candidate, provides broad-spectrum protection against SARS-CoV-2 variants in a hamster challenge model. Front Immunol 2023, 14, 1188605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleon, S. , et al., Design, immunogenicity, and efficacy of a pan-sarbecovirus dendritic-cell targeting vaccine. EBioMedicine 2022, 80, 104062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, M. , et al., Modelling the response to vaccine in non-human primates to define SARS-CoV-2 mechanistic correlates of protection. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.A. , et al., Mosaic RBD nanoparticles protect against multiple sarbecovirus challenges in animal models. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A.A. , et al., Mosaic sarbecovirus nanoparticles elicit cross-reactive responses in pre-vaccinated animals. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Vishwanath, S. , et al., A computationally designed antigen eliciting broad humoral responses against SARS-CoV-2 and related sarbecoviruses. Nat Biomed Eng 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozic, J. , et al., Use of eVLP-based vaccine candidates to broaden immunity against SARS-CoV-2 variants. bioRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ober Shepherd, B.L. , et al., SARS-CoV-2 recombinant spike ferritin nanoparticle vaccine adjuvanted with Army Liposome Formulation containing monophosphoryl lipid A and QS-21: a phase 1, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human clinical trial. Lancet Microbe 2024, 5, e581–e593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardi, N. , et al., mRNA vaccines - a new era in vaccinology. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2018, 17, 261–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiba, K. , et al., Overcoming thermostability challenges in mRNA-lipid nanoparticle systems with piperidine-based ionizable lipids. Commun Biol 2024, 7, 556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

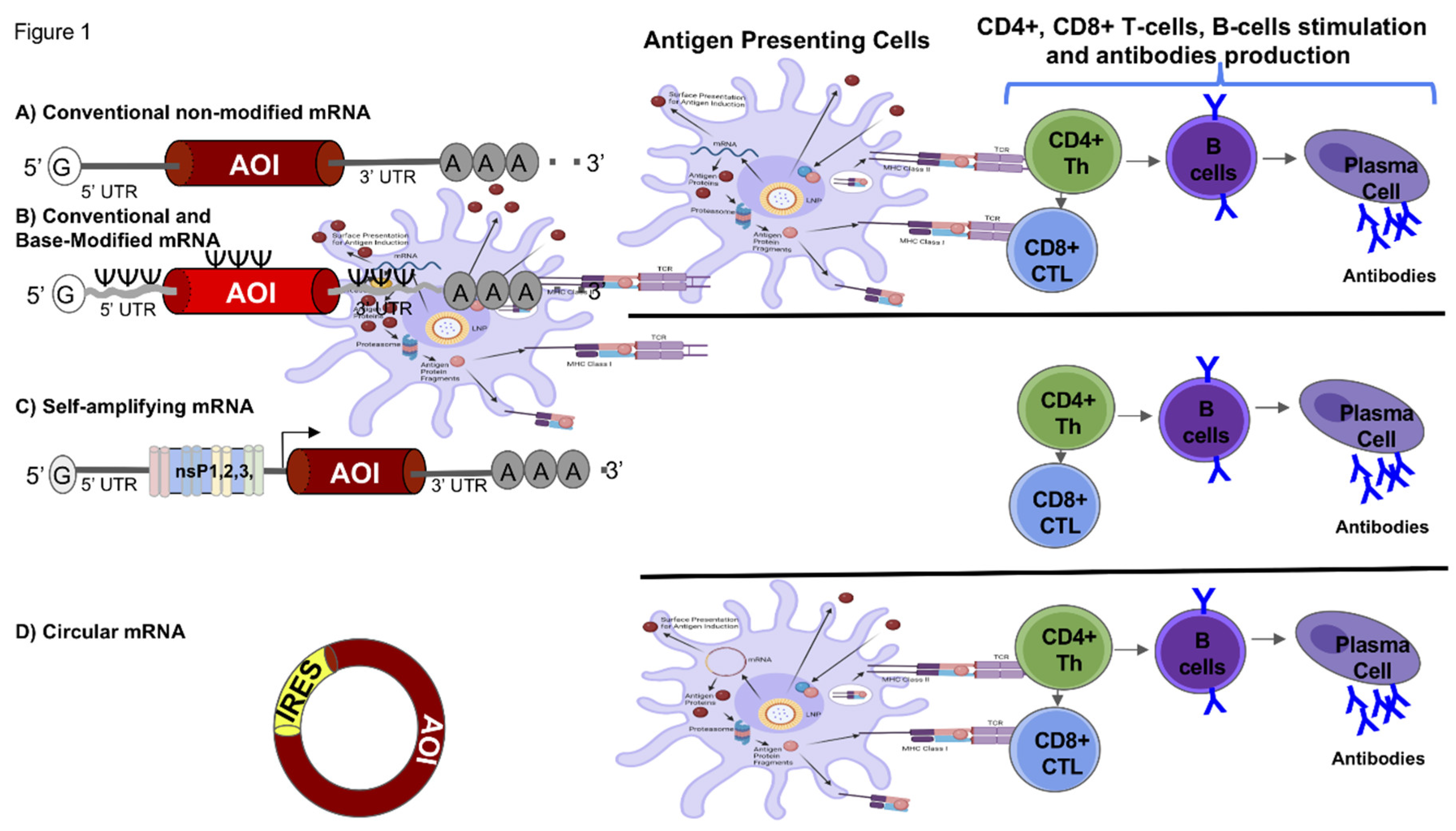

| Type of RNA Vaccine | Size of mRNA | Half-life in cells | Expression Duration | Cold Chain Required? | Mode of Action | Example of Vaccine | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional and base-modified mRNA, non-amplifying mRNA | Variable typically 1-5 kb | 6-12 hours | 1-3 days | Yes, typically requires cold storage (refrigeration) | Uses chemically modified nucleotides to enhance stability and translation, leading to protein antigen production and immune response induction. |

BioNTech/Pfizer. Highly effective, 95% efficacy, approved globally. Moderna. Highly effective, 94% efficacy, approved globally. |

[60,156] |

| Self-amplifying mRNA (saRNA) | 10-15 kb | 2-4 days | 1-2 months | Yes, typically requires cold storage (refrigeration) | Contains viral replicase machinery that allows the RNA to self-amplify within cells, producing a larger amount of antigen over an extended period. |

Arcturus Therapeutics. Ongoing, early results show strong immune response. Imperial College London. Phase 1 trial ongoing, safety and immune response being evaluated Gritstone. Phase I trials ongoing. |

[53,69,93] |

| Circular mRNA (circRNA) | Variable, typically 1-5 kb | 1-3 weeks | 1-3 months | No, can be stored at room temperature | Circular structure is resistant to exonucleases, leading to increased stability and prolonged antigen expression. | Laronde. Preclinical studies indicate potential for durability and stability | [54,99] |

| Thermostable mRNA | Variable typically 1-5 kb | 6-12 hours | 1-3 days | No, can be stored at room temperature | Engineered to maintain stability and function at higher temperatures. | CureVac. Moderate efficacy, 48% in Phase 3 trials | [115,157] |

| Vaccine Name | Vaccine Type | Developer | Clinical Phase | Dose and Regimen | Antigen | Publications (PMID, Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b4 | mRNA | Pfizer | Phase I trial ongoing | N/A | segments of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid, membrane, and ORF1ab proteins, targeting diverse HLA alleles. | 37164012 (2023) |

| GRT-R910 | saRNA | Gritstone bio, Inc. | Phase 1, NCT05148962 | 2 different doses (10 or 30 mcg) | Full-length Spike and selected conserved non-Spike T cell epitopes. | 37280238 (2023 |

| Mosaic-8b | Protein subunit | California Institute of Technology (Caltech) | Yet to begin | N/A | 1 SARS-CoV-2 RBD + 7 sarbecovirus RBD | 38148330, (2024) 33436524 (2021) 35857620 (2022) 36370711 (2022) 36865256 (2023) |

| DIOS-CoVax/ pEVAC-PS |

mRNA | DIOSynvax | Phase I, (https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN87813400) |

1.2mg, 0.8mg 0.4mg, or 0.2mg, 2 doses, 30 days apart |

T2_17 (DIOSynVax Generated) | 38148330, (2024) https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-995273/v1 (Under Review - Nature) |

| CD40.CoV2 | Protein subunit | Inserm Vaccine Research Institute | Yet to begin | N/A | Receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein | 38148330, (2024) 34471122 (2021) 35594660 (2022) 35801637 (2022) |

| OVX033 | Protein subunit | Osivax | Yet to begin | N/A | Nucleocapsid (N) Protein | 37409116 (2023) |

| Unnamed | mRNA, Viral vector and Protein subunit |

University of California Irvine/TechImmune LLC | Yet to begin | N/A | Multi-epitope | 33911008 (2021) 37292861 (2023) https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.05.23.542024 (Under Review - JV) |

| VBI-2901 | eVLP | VBI Vaccines | Phase I, NCT05548439 |

15-20 µg, 2 doses, 55 days apart | Spike trivalent (SARS- CoV-1, SARS-CoV-2, MERS-CoV) | 38148330, (2024) https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.28.462109 (Under Review) |

| SpFN 1B-06-PL | Protein subunit | Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR) | Phase I, NCT04784767 |

25 µg or 50 µg, 2 doses | SARS-CoV-2 Spike Ferritin Nanoparticle | 34711815 (2021) 34903722 (2021) 34919799 (2021) 34914540 (2022) 35632473 (2022) 36934088 (2023) 37023746 (2023) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).