1. Introduction

One of the structured ways to making decisions involved criteria interaction is known as multi-criteria decision making (MCDM). In MCDM, the problem is framed as one involving multiple criteria, where data is essential for making an informed decision, and a balance needs to be found among competing goals. MCDM is specifically designed to handle decisions with multiple criteria. Techniques like the Technique for the Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) help decision-makers prioritize criteria and make more balanced decisions [

4,

17]. Not all criteria have the same level of importance in decision making. Some may be critical, while others are secondary and less significant. Decisions can be influenced by changes in the criteria or their weights. Sensitivity analysis helps us to understand the stability of decision outcomes under different weighting scenarios or criteria values and how robust a decision is if circumstances change. Weighting ensures that critical factors have more influence on the final decision than less significant ones. Ensuring a best approximate weighting based on the informed data can lead to robust decision making, and this could be achieved through a dynamic weighting system based on the data involved. Decision making often involves uncertainty and risk, where the outcomes cannot be predicted with certainty. Softness and / or fuzzy techniques incorporate uncertainty into the decision-making process, allowing more robust decisions even when the information is incomplete or uncertain [

19,

20,

21,

22]. However, none of these decision processes utilized dynamic weighting in the interaction of criteria. Instead, most authors rely on fixed weighting systems based on the expertise of the decision-makers. This approach often leads to uncertainty and confusion, making it difficult to achieve precise and robust decision-making. Rahman et al. [

32] introduced an informed dynamic weighting system based on the data involved to address the MCDM problem using random hypergraphs. The authors first defined a Choquet integral operator over a random hypergraph and applied it to the MCDM problem.

Graphs and hypergraphs are ideal for representing complex, non-linear network systems. Networks often involving uncertainties can be modeled using random graphs and hypergraphs. The use of random graphs and hypergraphs [

15,

34] explicitly addresses these uncertainties. In 1959, Erdos introduced random graphs [

7], which have since been extensively studied and applied in numerous network problems [

14]. The foundation of random graph theory was further solidified with a series of papers [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] by Erdos and R’enyi, which have been widely utilized by researchers. While graphs represent interactions between pairs of objects, hypergraphs capture interactions within groups [

3,

15], where the groups are referred to as hyperedges, and the objects as vertices [

3]. The random hypergraphs used to define the Choquet integral operator are a generalized version of the Erdos-R’enyi model of random hypergraphs [

32]. The Choquet integral [

28] plays a significant role in MCDM. Several key properties of the Choquet integral operator over random hypergraphs are discussed with relevant examples in [

32].

TOPSIS is a multi-criteria decision-making technique that allows individuals and organizations to evaluate and rank alternatives based on multiple criteria or attributes [

17]. Developed by Hwang and Yoon in the early 1980s, this method has since gained widespread popularity across various fields, including engineering, business, environmental management, healthcare, and social affinity [

16,

40]. TOPSIS facilitates systematic analysis of both qualitative and quantitative factors, supporting informed decision-making in social and community contexts [

24]. In this article, the TOPSIS method is applied to solve multi-criteria decision-making problems within random hypergraphs. Our discussion covers the use of TOPSIS with dynamic weights in random hypergraphs, as well as its application with fixed weights, supported by relevant examples.

2. Preliminaries

This section presents the preliminaries that will be used in the subsequent sections. Every effort has been made to ensure that the article is self-contained.

2.1. Graph and Hypergraph

A graph is a mathematical structure used to represent pairwise relationships between objects. It consists of two main components: vertices and edges. Vertices are points or entities within the graph, representing various concepts such as people, cities, or abstract ideas. Edges are the connections between pairs of vertices, illustrating the relationships between the objects they represent. Graphs have widespread applications across fields like computer science, social network analysis, operations research, biology, and more. They provide a flexible and intuitive framework for representing and analyzing relationships between objects or entities.

A hypergraph generalizes the graph structure by allowing edges to connect any number of vertices. In a hypergraph, a hyperedge may connect one, two, or more vertices. Formally, let be a finite set of vertices, and let be a family of subsets of V. The pair is called a hypergraph, where V is the vertex set and E is the edge set. The order of the hypergraph, denoted , is the cardinality of V, that is, . The elements are referred to as nodes or vertices, and the subsets are called hyperedges or edges. The size of the hypergraph is the cardinality of E, i.e., . A hypergraph with no edges and no vertices, where and , is called an empty hypergraph. Edges within a hypergraph can have different relationships. Some edges may be included within others, while edges that coincide are called multiple edges. A hypergraph with no included edges is termed a simple hypergraph.

For a vertex , let denote the set of edges containing v. The number is the degree of the vertex v, while the number is the degree of the edge . A hypergraph is called k-regular if all vertices have the same degree , and it is called r-uniform if all edges have the same degree .

Now, let’s recall the generalized version of the standard Erdos - Rényi and Edgar Gilbert models for

r-uniform random hypergraphs on

n vertices, as described by Rahman et al. [

32]. Consider a random experiment with a finite number of outcomes, where the sample space corresponds to the vertex set. Through inherent connections or links, certain vertices are grouped together to form hyperedges. Since vertices represent outcomes of a random experiment, the subsets of the vertex set (hyperedges) can also be viewed as events. The combination of the vertex set and these grouped vertices forms a random hypergraph, where each hyperedge can be assigned a weight representing the probability of the corresponding event.

This random hypergraph generalizes the binomial

r-uniform random hypergraph

, where

. Here,

possible hyperedges are included, and each hyperedge is present with probability

p. Importantly, the hyperedges are mutually independent events. For further details, refer to Rahman et al. [

32].

2.2. Multi-Criteria Decision Making and TOPSIS

Multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) is a field of study that addresses decision-making problems involving multiple criteria or objectives. The goal is to evaluate and select the best alternative from a set of options, considering various factors.

According to Roszkowska [

33], the primary steps in the MCDM process are:

Establish system evaluation criteria that link system capabilities to overall goals.

Develop alternative systems or approaches for achieving those goals (generating alternatives).

Evaluate the alternatives based on the established criteria.

Apply a normative multiple criteria analysis method.

Select the optimal (preferred) alternative.

If the final solution is not satisfactory, gather new information and repeat the process in another iteration of multiple criteria optimization.

One of the widely used MCDM methods is TOPSIS (Technique for Order of Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution). TOPSIS helps in selecting the best alternative from a set of options by considering multiple criteria or attributes. The core principle of TOPSIS is to choose the alternative that has the shortest distance from the ideal solution and the greatest distance from the negative ideal solution [

17]. It is a popular, straightforward, and intuitive method that provides a systematic approach to decision-making, especially when multiple criteria need to be considered simultaneously.

TOPSIS has been applied across a wide range of fields. In business [

35], it has been used for tasks such as supplier selection, project prioritization, and performance evaluation. In engineering and technology [

1,

5,

18,

23], it aids in optimal design selection, risk assessment, and quality control. In environmental management [

2], TOPSIS is employed for site selection, pollution control strategy evaluation, and sustainable development assessments. In healthcare, the method has been used for hospital rankings, medical equipment selection, and evaluating healthcare systems. In agriculture, it has been applied to crop selection, land-use planning, and agricultural technology evaluation. Educational contexts [

29] also benefit from TOPSIS, where it is used for school rankings, faculty performance evaluation, and curriculum development.

These examples illustrate the versatility of TOPSIS across various domains, demonstrating its broad applicability.

2.3. Choquet Integral Operator over Random Hypergraph

Let’s recall the Choquet integral operator over a random hypergraph, as introduced by Rahman et al. [

32]. Let

be the vertex set of a simple random hypergraph

H. A function

is referred to as a score function. Let

represent the set of edges, and let

be the corresponding weights of the groups

. These weights are assumed to satisfy the equation

. If the assigned weights do not satisfy this condition, appropriate adjustments can be made through proper formulation.

Since the hypergraph is simple, neither nor holds.

A measure

, where

represents the power set of

V can be defined as follows:

where

are levels of

with

such that

. Then

is a capacity on

V satisfies normalization.

Suppose, ’s are reordered as according to the preference order of the score function f. Here is a permutation on .

The Choquet integral of the alternatives

(where

) with respect to the measure

and score function

f over the random hypergraph

is defined as follows:

where,

and

.

Using the above operator, Rahman et al. [

32] introduced an MCDM algorithm. In the subsequent sections, we extend the Choquet integral-based MCDM algorithm over random hypergraphs to model a TOPSIS framework for solving multi-criteria decision-making problems. A comparative study is conducted between the conventional TOPSIS method, which considers a set of alternatives with multiple criteria, and the TOPSIS approach using a random hypergraph introduced in this article.

3. TOPSIS Method over Random Hypergraph for Fixed Weights

To accommodate criteria interactions within the TOPSIS method, we propose a generalized TOPSIS approach that incorporates these interactions. In this approach, the set of criteria and their interaction groups are represented by a random hypergraph

, where

and

. Further details on criteria interactions over a random hypergraph can be found in [

32]. It is important to note that the weights of the hyperedges satisfy the condition

. The method proceeds through the following steps.

Express the assessment information of the alternatives corresponding to the criteria into the decision matrix , where indicates the partial evaluation of the alternative with respect to the criteria .

Criteria interacted decision matrix

where

if

indicates the partial evaluation of the

alternative

with respect to the

interacted group of criteria

.

Normalize the criteria interacted decision matrix

where

Construct the weightage matrix

-

Determine the positive ideal and negative ideal . Positive ideal can be defined as

where

Also negative ideal is defined as

-

calculation separation measure

The distance between the alternative with the positive ideal solution is defined as

The distance between the alternative with the negative ideal solution is defined as

-

Relative closeness from ideal solution or preference value for each alternatives is given as

If , then and if , then .

Greater value indicates that the preferred alternative

Remark 1. The TOPSIS method over a random hypergraph differs from the conventional TOPSIS method only in how it handles interactions among criteria and the weighting of criteria. All other computational steps remain almost identical to the original TOPSIS method. By doing so, the process also takes into account the impact of criteria interactions when determining the best alternatives.

4. Numerical Example Based on Fixed Weights TOPSIS Method over Random Hypergraph

We consider the same MCDM problem discussed in [

32] to facilitate a comparative study. The number of alternatives in the problem is 10, namely,

, and there are 4 criteria denoted as

. For our convenience, we recall the decision matrix, which is given as follows:

-

Step 1.

Decision matrix

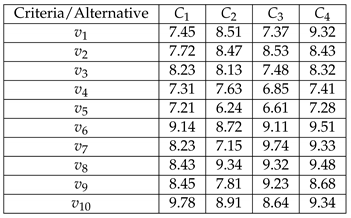

Table 1.

The assessment decision matrix D.

Table 1.

The assessment decision matrix D.

-

Step 2.

The hyperedges of the random hypergraph are , , . Based on these hyperedges, we construct the interacted decision matrix Q as follows.

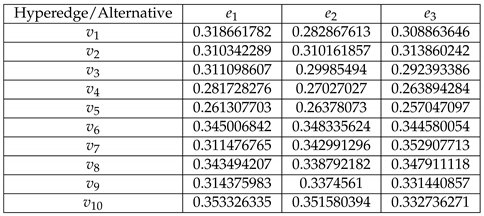

Table 2.

The interacted decision matrix Q.

Table 2.

The interacted decision matrix Q.

-

Step 3.

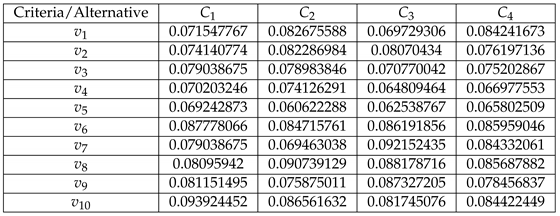

Construct the normalize matrix

Table 3.

The normalize matrix.

Table 3.

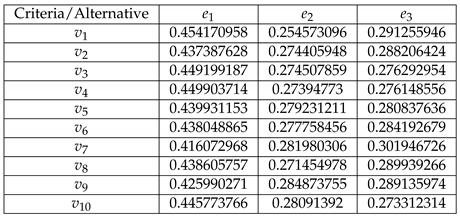

The normalize matrix.

-

Step 4.

-

Construct the weightage matrix

Weightage to the criteria. i.e. .

Table 4.

The weightage matrix.

Table 4.

The weightage matrix.

-

Step 5.

-

Positive ideal and negative ideal Positive ideal

where

Negative ideal

={, , }

={, , }

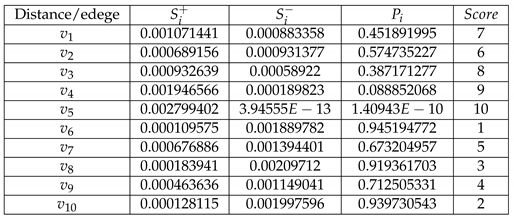

Table 5.

Table for .

Table 5.

Table for .

-

Step 6.

-

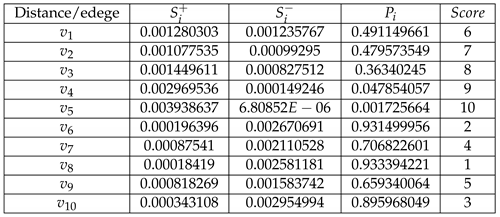

, , and can be calculated as

-

Step 7.

End

5. TOPSIS Method over Random Hypergraph with Dynamic Weights

The working principle of this method is almost same as the previous method with exception that to incorporate the criteria interactions and their weights, the dynamic weights for each individual shall be taken instead of fixed weight. We note that we shall take dynamic weights computation technique that adopted in Pisand algorithm [

32]. We consider a random hypergraph

, where

(the set of criteria) and

(interacted groups). The process of the method involves the following steps.

Express the assessment information of the alternatives corresponding to the criteria into the decision matrix , where indicates the partial evaluation of the alternative with respect to the criteria .

Criteria interacted decision matrix

where

if

indicates the partial evaluation of the

alternative

with respect to the

interacted group of criteria

.

Normalize the criteria interacted decision matrix

where

-

Calculate the dynamic weights of the hyperedges for each individual.

Construct the interaction matrix

B as follows:

where

and

are the interaction levels of

, respectively.

-

Estimation of the weightage for the hyperedges for each alternative .

The procedure represents the partial evaluation for each alternative corresponding to the interrelated interactions of the criteria .

Construct the set , where . Then for each , the set represents a copy of the edge set E of the random hypergraph H.

Since the hypergraph

H is simple, for any two distinct groups

and

, neither

nor

for all

. The degree assignment

corresponding to each alternative

for hyperedges

is determined by

where

is the degree of

in

H. Then

Construct the weightage matrix

-

Determine the positive ideal and negative ideal . Positive ideal can be defined as

where

The negative ideal is also defined as

-

Calculation of separation measure.

The distance between the alternative and the positive ideal solution is defined as .

The distance between the alternative and the negative ideal solution is defined as .

-

Relative closeness from ideal solution or preference value for each alternatives is given as

If , then and if , then . The higher value of indicates the preferred alternative .

6. Numerical Example Based on Dynamic Weights TOPSIS Method over Random Hypergraph

In order to conduct a comparative study, we revisit the issue outlined above. The problem involves 10 alternatives, denoted as , and encompasses 4 criteria, represented as where j ranges from 1 to 4. To streamline our analysis, we reiterate the steps whose computation tables align with those utilized in previous methods.

-

Step 1.

For the assessment information of the alternatives, we refer to

Table 1.

-

Step 2.

For the interacted decision matrix of criteria, we refer to

Table 2.

-

Step 3.

For normalization of the interacted decision matrix of criteria, we refer to

Table 3.

-

Step 4.

For the dynamic weights, we construct the

Table 6.

-

Step 5.

Construct the weightage matrix

(see

Table 7).

-

Step 6.

-

Computed positive ideal and negative ideal.

={, , }

={, , }

For the ranking table, we refer to

Table 8.

-

Step 7.

End

7. Numerical Example Based on TOPSIS Method

We consider the same MCDM problem as in the previous example to facilitate a comparative study. The number of alternatives in the problem is 10, namely, , and there are 4 criteria denoted as . To solve this problem by TOPSIS method, we follow the following steps.

-

Step 1.

Construct the decision matrix D (the same as in the previous example).

Table 9.

The assessment decision matrix D.

Table 9.

The assessment decision matrix D.

-

Step 2.

-

Normalised the decision matrix.

We normalised the decision matrix by the relation

, where

Table 10.

The normalize matrix.

Table 10.

The normalize matrix.

-

Step 3.

-

Weightage matrix

The same weight has been given to the criteria. i.e. , .

Table 11.

The weightage matrix.

Table 11.

The weightage matrix.

-

Step 4.

-

Positive ideal and negative ideal Positive ideal

where

Negative ideal

={, , , }

={, , , }

-

Step 5.

-

, , and can be calculated as

Table 12.

.

Table 12.

.

-

Step 6.

End

8. Results and Discussions

As discussed in earlier, the formation of the individual sets () is contingent upon the levels of interaction (), which, in turn, is influenced by the criteria () and their interactions within the problem. Consequently, the outcomes derived from the dynamic weights TOPSIS method, as defined over the random hypergraph, reflect the combined effects of various interactions among individuals and criteria.

It’s worth noting that in cases where the criteria are independent, meaning there is no interaction among them, the random hypergraph

comprises only singleton subsets of

C as its hyperedges (refer to

Figure 1).

Furthermore, the interaction level of each hyperedge (where ) corresponding to each alternative i (where ) is . In such scenarios, both proposed TOPSIS methods reduce to the general TOPSIS method.

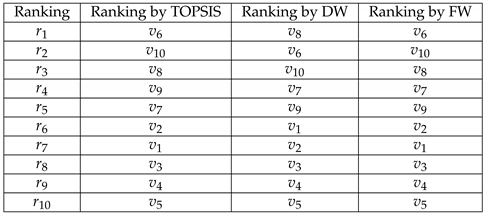

To offer a comprehensive comparison across various approaches, the overall evaluation of the alternatives

for each method is presented in

Table 13.

It is evident from

Table 13 that there is a noticeable variation in the ranking of alternatives between the proposed TOPSIS methods and the traditional TOPSIS method. This disparity arises from the distinct computational processes employed by each method. Furthermore, even within the two proposed methods, differences in alternative rankings are apparent, attributed to the use of dynamic weights versus fixed weights. However, the rankings produced by TOPSIS and the fixed weights method are nearly identical, except for ranks 4 and 5. Based on this comparison, we have made the following observations.

The dynamic weights method accounts for the cumulative effects of interactions among individuals and criteria, while the fixed weight method evaluates interactions solely among criteria. Despite these differences, the optimal (best and least preferable) alternatives identified through all three methods show proximity, validating the soundness and applicability of our proposed models. Additionally, with the dynamic weights method, there is no need to assign values to the interacted groups of criteria, as it generates weights based on interactions among individuals and criteria.

Given that the dynamic weights method incorporates the combined effects of interactions among individuals and criteria, it can be regarded as superior to the other two methods.

Author Contributions

All authors have equal contributions.

Funding

This study was carried out with financial support from Princess Nourah Bint Abdul rahman University (PNU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to Princess Nourah Bint Abdul rahman University (PNU), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, for funding this research under Researchers Supporting Project Number (PNURSP2024R231).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agrawal, V., Kohli, V., Gupta, S., Computer aided robot selection: the multiple attribute decision making approach, International Journal of Production Research, 29(8), 1629-1644, 1991.

- Akgül, E., Bahtiyari, B.R., Aydogan, E.Kizilkaya., Benli, H., Use of topsis method for designing different textile products in coloration via natural source madder, Journal of Natural Fibers, 19(14), 8993-9008, 2022.

- Berge, C., Graphs and Hypergraphs, North Holland Publishing Co., Amsterdam, The Netherland, (1990).

- Chakraborty, S., TOPSIS and Modified TOPSIS: A comparative analysis, Decision Analysis journal, Volume 2, March 2022.

- Chede, S.J., Adavadkar, B.R., Patil, A.S., Chhatriwala, H.K., Keswani, M.P., Material selection for design of powered hand truck using TOPSIS, International Journal of Industrial and systems Engineering, 39(2), 234-246, 2021.

- Deng, S., Huang, L., Xu, G., Social network-based service recommendation with trust enhancement, Expert Systems with Applications, 41(18), 8075-8084, 2014.

- Erdos, P., Graph Theory and Probability, Canadian Journal of Mathematics 11, 34-38 (1959).

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A., On random graphs I, Publ. Math. Debrecen 6 290-297 (1959).

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A., On the evolution of random graphs, Publ. Math. Inst. Hungar. Acad. Sci. 5, 17-61 (1960).

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A., On the strength of connectedness of a random graph, Acta. Math. Acad. Sci. Hungar., 8, 261-267 (1961).

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A., On random matrices, Publ. Math. Inst. Hungar. Acad. Sci. 8, 455-461 (1964).

- Erdos, P. and Rényi, A., On the existence of a factor of degree one of a connected random graph, Acta. Math. Acad. Sci. Hungar. 17, 359- 368 (1966).

- Feng, C. M., Wang, R. T., Considering the financial ratios on the performance evaluation of highway bus industry, Transport Reviews, 21(4), 449-467, 2001.

- Frieze, A., and Karoński, M., In Introduction to Random Graphs, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (2015).

- Ghoshal, G., Zlatic, V., Caldarelli, G., and Newman, M.E.J., Random Hypergraphs and its Applications, Phisical Review E 79, 066118, 1-10 (2009).

- Gourdine, G., Morrison, W., J., Social Affinity Flow Theory (SAFT) and New Insights into the Systems Archetypes of Escalation and Tragedy of the Commonsl, Journal of Behavioral and Applied Management, Vol. 23(2), 60–73, 2023.

- Hwang, C.L. and Yoon, K., Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications, Springer-Verlag, New York, (1981). [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C., Engin, O., Kabak, O¨., Kaya, I˙, Information systems outsourcing decisions using a group decision-making approach, Engineering Applications of Artificial Inteligence, Volume 22, 6, 832-841, 2009.

- Kakati, P., Borkotokey, S., Mesiar, R., and Rahman, S. (2018). Interval neutrosophic hesitant fuzzy choquet integral in multicriteria decision making. Journal of Intelligent & Fuzzy Systems, 35(3), 3213-3231.

- Kakati, P., Borkotokey, S., Rahman, S., and Davvaz, B. (2020). Interval neutrosophic hesitant fuzzy Einstein Choquet integral operator for multicriteria decision making. Artificial Intelligence Review, 53, 2171-2206.

- Kakati, P. and Borkotokey, S. (2020). Generalized interval-valued intuitionistic fuzzy Hamacher generalized Shapley Choquet integral operators for multicriteria decision making. Iranian Journal of Fuzzy Systems, 17(1), 121-139.

- Kakati, P. and Rahman, S. (2022). The q-rung orthopair fuzzy hamacher generalized shapley choquet integral operator and its application to multiattribute decision making.

- Khan, M.S., Shah, S.I.A., Javed, A., Qadri, N.M., Hussain, N., Drone selection using multi-criteria decision-making methods, International Bhurban Conference on Applied Sciences and Technologies, IBCAST, IEEE, 256-270, 2021.

- Kim, J.K., Kim, H.K., Oh, H.Y., Ryu, Y.U., A group recommendation system for online communities., International Journal of Information Management, 30(3), 212–219, 2010.

- Laroche, M., Mukherjee, A., Nath, P.,An empirical assessment of comparative approaches to service quality measurement, Journal of Services Marketing, 19, 174-184, 2005.

- Mandic, K., Bobar, V. and Delbasic, B., Modelling interactions among criteria in MCDM methods: A review, Conference Paper in Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing, May 2015. [CrossRef]

- Murofushi, T., Sugeno, M., & Machida, M. (1994). Non-monotonic fuzzy measures and the Choquet integral. Fuzzy Sets and Systems, 64(1), 73-86.

- Murofushi, T. , and Sugeno, M. An interpretation of fuzzy measures and the Choquet integral as an integral with respect to a fuzzy measure, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, C., Yeoh, W., Lee, A., Moayedikia, A., Deciding discipline, course and university through TOPSIS, Studies in Higher Education, 45(12), 2497-2512, 2020.

- Nilashi, M., Ibrahim, bin, O., Ithnin, N., Hybrid recommendation approaches for multi-criteria collaborative filtering, Expert Systems with Applications, 41(8), 3879-3900, 2014.

- Parkan, C., Wu, M.L., Decision-making and performance measurement models with applications to robot selection, Computers and Industrial Engineering, 36(3), 503-523, 1999.

- Rahman, S., Baro, N., and Kakati, P. Choquet integral operator over random hypergraph and its application in multicriteria decision making, 10 October 2023, PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Roszkowska, E. Multi-criteria decision making models by applying the TOPSIS method to crips and interval data. Multi. Criteria Decis. Mak./Univ. Econ. katow, 2011, 6, 200–230. [Google Scholar]

- Shirzadian, P, Antony1, B, Gattani, A. G., Tasnina, N. and Heath, L. S., A time evolving online social network generation algorithm, Sci Rep 13, 2395, (2023). [CrossRef]

- Shyur H., J., Shih, H. S., A hybrid MCDM model for strategic vendor selection, Mathematical and Computer Modelling, 44, 749-761, 2006.

- Tavana, M., Hatami-Marbini, A., A group AHP-TOPSIS framework for human spaceflight mission planning at NASA, Expert Systems and Applications, 38(11), 13588-13603, 2011.

- Ture, H., Dogan, S., Kocak, D., Assessing euro strategy using multi-criteria decision making methods: VIKOR and TOPSIS, Social Indicators Research, 142, 645-665, 2018.

- Ucer, S., Ozyer, T. and Alhajj, R., Explainable artificial intelligence through graph theory by generalized social network analysis-based classifier, Sci Rep 12, 15210 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Wang, D., Liang, Y., Xu, D., Feng, X., A content-based recommender system for computer science publications, Knowledge based System, 157, 1-9, 2018.

- Xiwang, Y., Yang, G., Yong, L., Harald, S., A survey of collaborative filtering based social recommender systems, Computer Communications, Vol. 41, 1-10, 2014.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).