1. Introduction

Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder that is characterised by the progressive degeneration of the bone microarchitecture [

1]. The asymptomatic nature of osteoporosis allows it to progress without noticeable symptoms until a fracture occurs, leading to substantial morbidity rates [

2]. Estimates indicate that osteoporosis-related fractures will rise significantly in the next two decades, placing a significant burden on healthcare systems [

3].

Osteoporosis involves an imbalance in the bone turnover rate where the rate of bone resorption (osteoclasts) exceeds the rate of bone formation (osteoblasts) resulting in a net loss of bone mass [

4]. Osteoclasts play a crucial role in bone resorption by secreting acids and enzymes to absorb the bone matrix [

5]. Osteoclast differentiation is mainly regulated by receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL), produced by bone-forming osteoblasts, which binds to the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B (RANK) receptor on the surface of osteoclast precursors [

6]. RANKL stimulates key mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) such as extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK),

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38 MAPK, and further activates the nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) pathway to promote osteoclast proliferation, differentiation, activation and cell survival [

7]. These pathways result in the expression of nuclear factor of activated T-cells, cytoplasmic 1 (

NFATc1), via Fos proto-oncogene (

c-Fos), which is a major regulator of osteoclastogenesis [9].

NFATc1 stimulates transcription of osteoclast-specific markers like tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP), a biomarker for osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption [

8,

9]. Compounds that reduce TRAP activity or inhibit specific MAPKs are being investigated as potential treatments for osteoporosis [

10].

Runt-related transcription factor 2 (

Runx2), is the master transcription factor for osteoblasts, essential for activating the translation of genes such as alkaline phosphatase (

ALP) and osteocalcin (

OC) that promote osteoblast maturation and function [

11].

Runx2 expression peaks in immature osteoblasts and diminishes in mature osteoblasts illustrating its pivotal role in determining the lineage and function of osteoblasts [

12]. During early osteoblastogenesis, ALP activity is crucial for bone mineralization by releasing inorganic phosphate ions (Pi) that form hydroxyapatite crystals [

13] OC, a mature osteoblast marker, is secreted during the later stages of bone differentiation and mineralization, and plays a critical role in skeletal development and bone remodelling [

14] The precise coordination of

Runx2,

OC, and

ALP is crucial for osteoblast differentiation and bone formation, providing valuable insights into the efficacy of osteoprotective agents such as zingerone [

15].

Zingerone (4-(4-hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone), a compound found in cooked ginger, is renowned for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and hypoglycaemic properties [

16,

17]. Recent studies have highlighted its potential benefits for bone health [

18,

19,

20]. For instance, zingerone has been shown to suppress osteoclast formation in RAW264.7 cells by downregulating the NF-κB signalling pathway potentially preventing excessive bone loss [

19] Additionally, zingerone's anti-inflammatory properties may protect against bone loss by reducing inflammation [

21]. It inhibits inflammatory mediators such as interleukin (IL); IL-6, IL-1β, and Tumour Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF-α), while attenuating oxidative stress and preventing apoptosis. These combined effects likely benefit bone health by inhibiting the MAPK and NF-κB signalling pathways [

22,

23]. Furthermore, Song

et al. (2020) found that zingerone promotes osteoblast differentiation through miR-200c-3p upregulation and smad7 downregulation in human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (hBMSC) [

18]. This regulation enhances the expression of osteoblast differentiation markers such as

ALP,

Runx2 and

OC [

18].

Given these health benefits, further in vitro research is warranted to explore zingerone’s molecular interactions in bone metabolism and its osteogenic potentials. This study investigated the in vitro osteogenic potential of zingerone using SAOS-2 osteosarcoma and RAW264.7 macrophage cell lines.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Zingerone Sample Preparation

Stock solutions of 0.1M zingerone (Alfa Aeasar; Haverhill, USA) was prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and stored at -80°C. The stock solution was diluted to concentrations ranging from 0.1-200µM in McCoy’s 5A or Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) media media (GIBCO; Carlsbad, USA) [

18,

20].

2.2. Cell Lines, Culture and Treatment

2.2.1. SAOS-2 (Osteoblast)

The human osteosarcoma cell line, SAOS-2 (European Collection of Cell Culture

®, Sigma-Aldrich, CAT# 89050205, Missouri, USA) was used as a human osteoblast-like cell line [

24]. SAOS-2 cells are able to form mineral deposits and express several key genes involved in osteoblast differentiation. Therefore, these cells are commonly used as an

in vitro model for osteoblast activity [

25]. SAOS-2 cells were cultured and maintained in complete McCoy’s 5A containing 20% heat-inactivated Foetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Capricorn Scientific; Ebsdorfergrund, Germany) at 37°C in 5% CO

2 humidified atmosphere. Cells with a confluency of 70-80% were trypsinised with 0.25% trypsin- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), centrifuged for 2 minutes at 1000×

g and resuspended in McCoy’s 5A [

26]. Following trypan blue exclusion, and seeded for subsequent experiments [

27].

2.2.2. RAW264.7 (Osteoclast)

RAW264.7 murine macrophages (American Type Culture Collection; Rockville, USA) were used as an osteoclast precursor cell line [

28]. These cells express the RANK receptor and can form large, multinucleated, bone resorbing cells in the presence of RANKL [

29]. RAW264.7 cells were cultured in complete DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS and incubated at 37°C and 5% CO

2. For experimental seeding, cells were detached using a cell scraper and seeded for subsequent experiments following trypan blue exclusion [

26].

2.3. Cell Viability and Proliferation: Resazurin Assay

The effect of zingerone on bone cell viability was evaluated via resazurin assay. SAOS-2 or RAW264.7 cells were seeded separately in a 96-well plate containing complete McCoy’s 5A and DMEM media at a density of 2.5

cells/mL overnight. Subsequently, media was replaced, and the cells were exposed to zingerone (0.1-200µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 48h. The positive control was replicated by exposing cells to 0.2% triton X-100. Media was replaced with 10% resazurin solution and incubated for 4h at 37°C [

30]. Absorbance was measured at 570nm and 600nm using Epoch Micro-plate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, Vermont, USA) [

31].

2.4. Alizarin Red S Staining and Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP) Activity Assay

SAOS-2 cells were seeded in sterile 96-well plates at a density of 2.5 cell/mL in osteogenic differentiation medium (osMcCoy) (McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10mM β-glycerophosphate, 50mM ascorbic acid and 10mM dexamethasone) and different concentrations of zingerone (5, 100 and 200µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 7, 14 and 21 days. These time points were used as correspondents to the three critical stages of the differentiation process. Therefore, the effects of zingerone on SAOS-2 cells were evaluated on early- (day 7), intermediate- (day 14) and late-stage (day 21) mineralisation. Media and all factors were changed every 2-3 days.

Cells were fixed with 10% formalin for 1h and stained with 2% (w/v) Alizarin Red S (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 10 minutes [

32]. Rinsed with double distilled water and air dried overnight before images were captured using Olympus BH2 microscope equipped with an SC30 camera (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Alizarin red S dye was extracted with 10% acetic acid, neutralized with 10% ammonium hydroxide and absorbance was measured at 405nm using Epoch Micro-plate spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments; USA). Cells were fixed for 5 minutes with 10% formalin following 1h incubation with ALP Buffer (5mM

p-nitrophenylphosphate, 0.5mM MgCl2·6H

2O, 0.1% triton-X 100X in 50mM Tris-HCl at pH 9.5) at 37°C. Thereafter, 100 µl of the product solution was transferred into a sterile 96-well plate and absorbance was measured at 405nm and 650nm using Epoch Micro-plate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments; USA). Data was calculated relative to vehicle.

2.5. Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (q-PCR)

SAOS-2 cells were seeded in 48-well plates at a density of 3

cells/mL with osMcCoy containing zingerone (200µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 7 and 14 days. The sub-maximal effective concentration of zingerone was selected based on the proliferation and differentiation assays. The expression of mRNA was evaluated at two different time points to capture the shifts in gene expression that characterize different stages of osteoblast differentiation. Day 7 represents an early to mid-stage in osteoblast differentiation, where the cells are beginning to express early markers of osteogenesis, such as

Runx2 and

ALP (alkaline phosphatase). Whilst day 14 is where SAOS-2 cells typically exhibit more mature osteoblast characteristics, including increased expression of late-stage markers like osteocalcin (

OC), as an indication of the progression towards mineralization. Total ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted using Aurum

TM total RNA Mini Kit (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Hercules, California, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was reverse transcribed to cDNA using a SensiFAST cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bioline Reagents Ltd, United Kingdom). The osteoblast-specific primers (

Table 1) were sourced from Inqaba Biotec (Pretoria, South Africa). qPCR was performed via Luna

® Universal q-PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA) and Light Cycler Nano (Roche Diagnostics; Basel, Switzerland) according to the protocol indicated in

Table 1. Data was analysed using the -2

ΔΔCT method with RPLPO as the loading control.

2.6. Tartrate-Resistant Acid Phosphatase (TRAP) Staining and Activity

RAW264.7 osteoclast-like cells were seeded in sterile 96-well culture plates at 2.5

cells/mL in complete DMEM together with 5ng/mL RANKL. A lower concentration of RANKL was used maintain cell viability and ensure that the observed effects were due to differentiation and not cell loss. This allowed for a clear and measurable readout of TRAP activity in response to zingerone treatment that directly correlated with the number and activity of mature osteoclast-like cells. RAW264.7 cells were exposed to zingerone (100, 150 and 200µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 5 days. Media and all factors were replaced on days 2-3. Thereafter, cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in PBS and stained for TRAP as described by Kasonga

et al. (2015). Images were captured (scale bar = 2mm) with Olympus BH2 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and TRAP-positive cells with three or more nuclei were counted as osteoclasts [

33]. Furthermore, conditioned media was collected from each well and TRAP enzyme activity was measured at 405nm and 650nm using an Epoch Micro-plate Spectrophotometer (BioTek Instruments; USA) [

5].

2.7. Western Blotting

RAW264.7 cells were seeded in 6-well plates at 5

cells/mL containing complete DMEM and incubated overnight to attach. Cells were pre-exposed to the sub-maximal effective concentration of zingerone (200µM) or vehicle (0.1% DMSO) for 4h at 37°C. For western blot analysis, a higher RANKL concentration (15ng/mL) was used to ensure that the specific proteins associated with osteoclast differentiation and activation were sufficiently expressed. This concentration produced a clear and detectable signal that ensured a strong activation of the investigated pathways and proteins therefore mitigating low protein expression with weak or undetectable bands on the membrane. After stimulation with RANKL (15ng/mL) for 5, 10 and 15 minutes, cells were lysed in ice-cold radio immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer supplemented with 0.3M phenylmethyl-sulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), 5% protease inhibitor cocktail and 5% phosphatase inhibitor cocktail. Purified proteins were quantified using a micro bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein kit (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, USA), fixed on a 4-15% Mini Protean TGX gel (BioRAD, Hercules, California, USA) at 200mV, and electro-transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using Tris-glycine transfer buffer (25mM Tris, 192mM glycine and 20% methanol) for 1h. Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin for 1h and probed with primary rabbit polyclonal antibodies (1:500;

p-p38,

p-JNK,

p-ERK and 1:1000; JNK, ERK and p38 (Abcam, Massachusetts, USA) overnight at 4⁰C. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as the loading control. After incubation with goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugates secondary antibody (BioRAD, Hercules, California, USA) for 1h at room temperature, membranes were developed using Clarity ECL substrate and visualized via Chemidoc MP (BioRAD, Hercules, California, USA). Band densities were quantified using ImageJ software (NIH, Version 1.53r) [

34].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

All data was displayed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) unless stated otherwise. All experiments were conducted in triplicate. Statistical analysis was performed with the aid of GraphPad Prism 9 software (San Diego, California, USA). Differences were analysed using two-way ANOVA following Tukey’s multiple comparison. Data was considered statistically significant if p<0.05.

3. Results

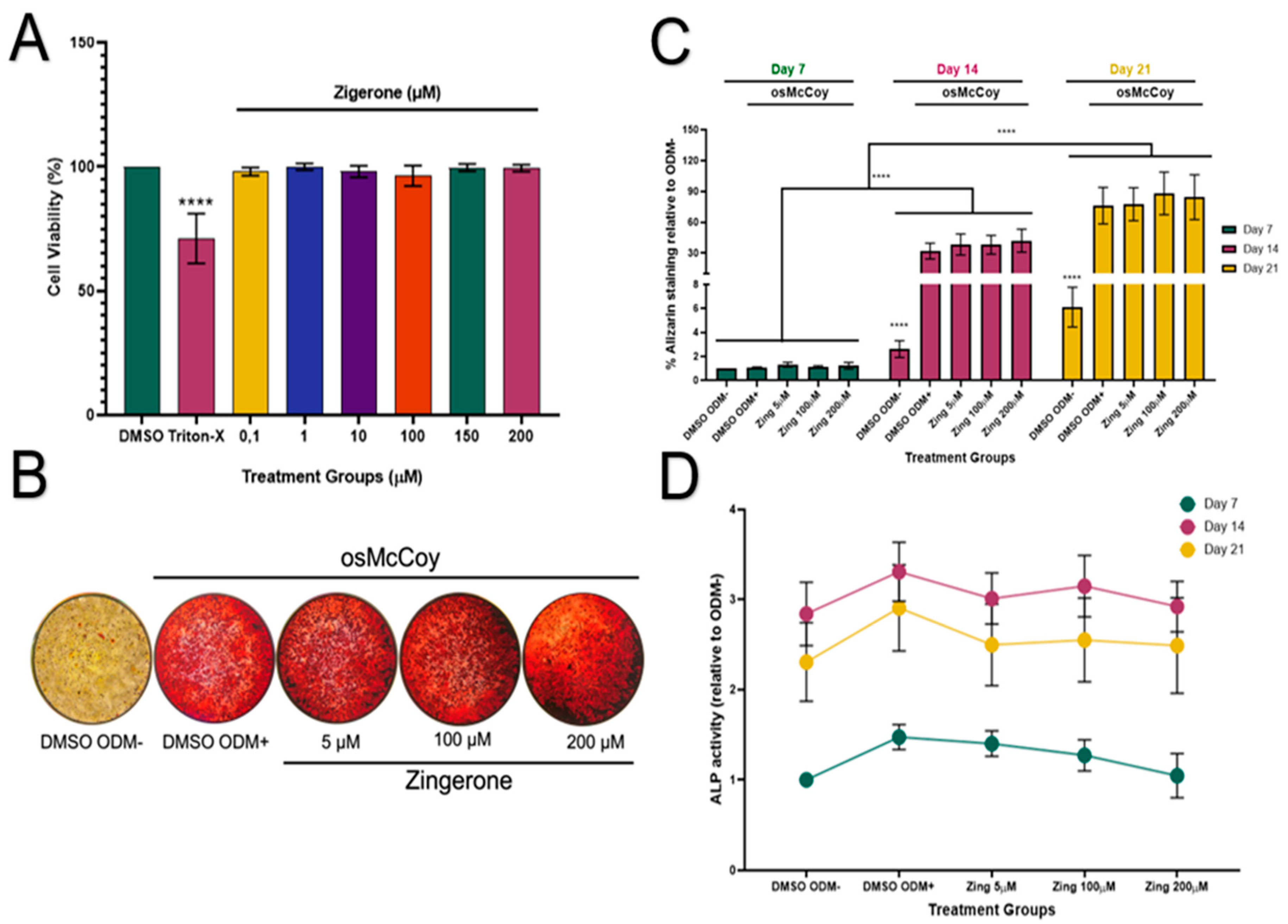

3.1. Zingerone Does Not Affect Mineralization or ALP Protein Activity in SAOS-2 Cells

Zingerone showed no cytotoxic effects to SAOS-2 cells at all tested concentrations (

Figure 1A; p>0.05). Cells treated with osMcCoy media (ODM+) induced mineralisation and stained pink for Alizarin red S compared to that grown without osMcCoy (ODM-) (

Figure 1B). The influence of zingerone on SAOS-2 differentiation was investigated during three critical stages: 7, 14 and 21 days. Mineralisation of SAOS-2 cells was at its lowest capacity on day 7 and peaked on day 21 (

Figure 1C). A significant increase in mineralisation was observed in SAOS-2 ODM+ cells on days 14 and 21 when compared to their corresponding SAOS-2 ODM- controls (p<0.001;

Figure 1C). Zingerone (5, 100 and 200µM) had no effect on osteoblast-like mineralisation of SAOS-2 cells from day 7-21 when compared to the ODM+ cells (p>0.05;

Figure 1C).

ALP activity increased significantly on day 14 for all treatment groups compared to day 7 (p<0.05;

Figure 1D;). However, the ODM- cells showed similar ALP levels as the ODM+ cells on days 7, 14 and 21, indicating that the ALP assay may lack sensitivity in detecting osteoblast-like differentiation of SAOS-2 cells. Zingerone (5-200µM) did not significantly affect ALP activity at days 7, 14 or 21 when compared to the ODM+ control (p>0.05;

Figure 1D).

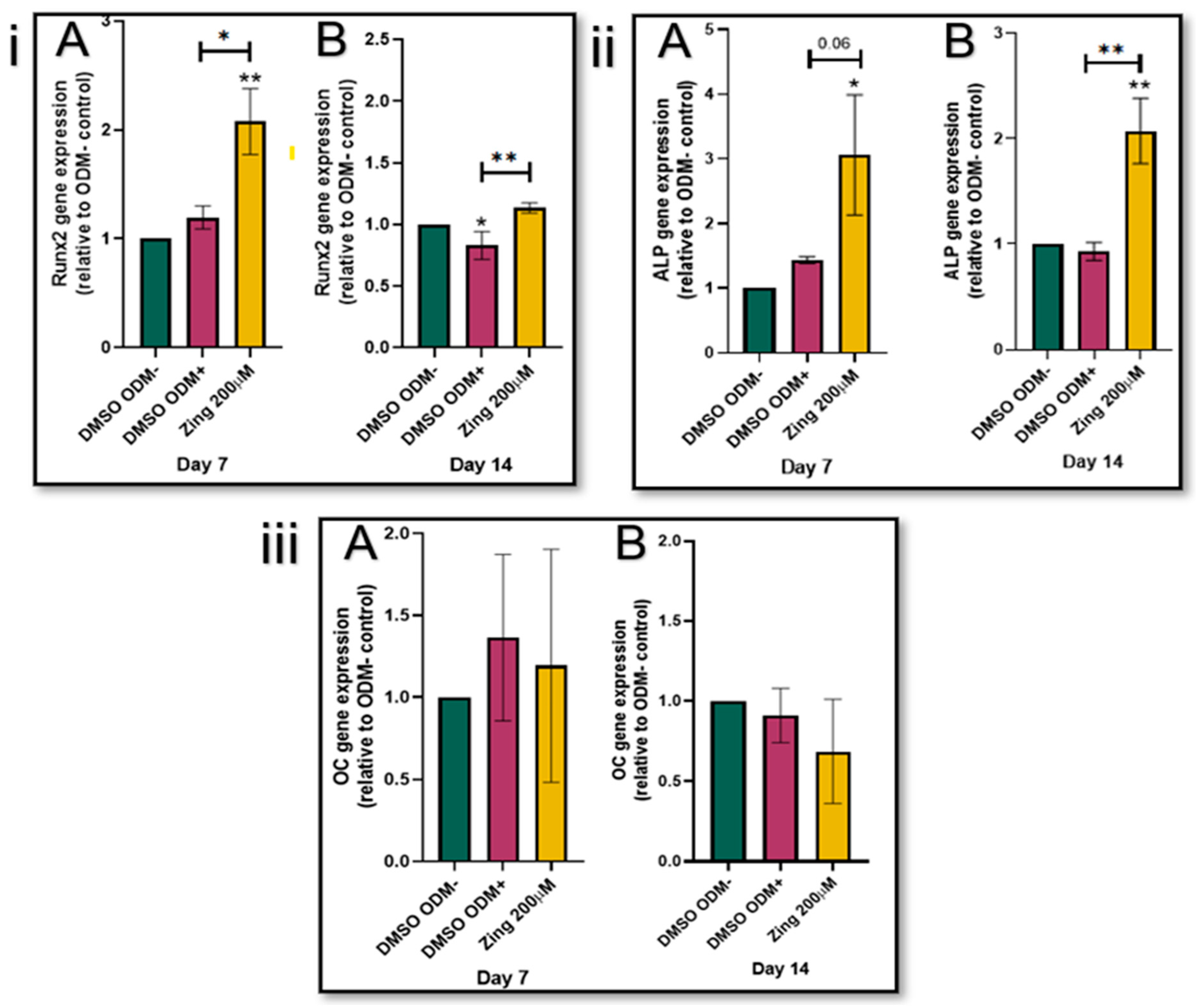

3.2. Zingerone Stimulates Runx2 and ALP Expression

The addition of zingerone (200µM) significantly increased

Runx2 expression levels in SAOS-2 cells on day 7 and 14 compared to their corresponding ODM+ controls (

p<0.05;

Figure 2(i); A & B). In the early stages of differentiation as represented by day 7 (

Figure 2(ii)A), ALP levels of zingerone-treated SAOS-2 cells were two-fold higher (3.06) compared to the osteogenic control without zingerone (ODM+; 1.44) (

p=0.06). On day 14, the zingerone-treated SAOS-2 cells had ALP levels significantly higher (2.07) than the ODM+ treated control (0.93) (

p<0.05;

Figure 2(i)B). The

Runx2 and

ALP gene expression of ODM+ cells were not significantly altered compared to their corresponding ODM- controls (

p>0.05;

Figure 2(i) & (ii)); Zingerone had no effect on

OC gene expression in SAOS-2 cells during the 7- and 14-day differentiation and maturation process (

p>0.05;

Figure 2(iii)).

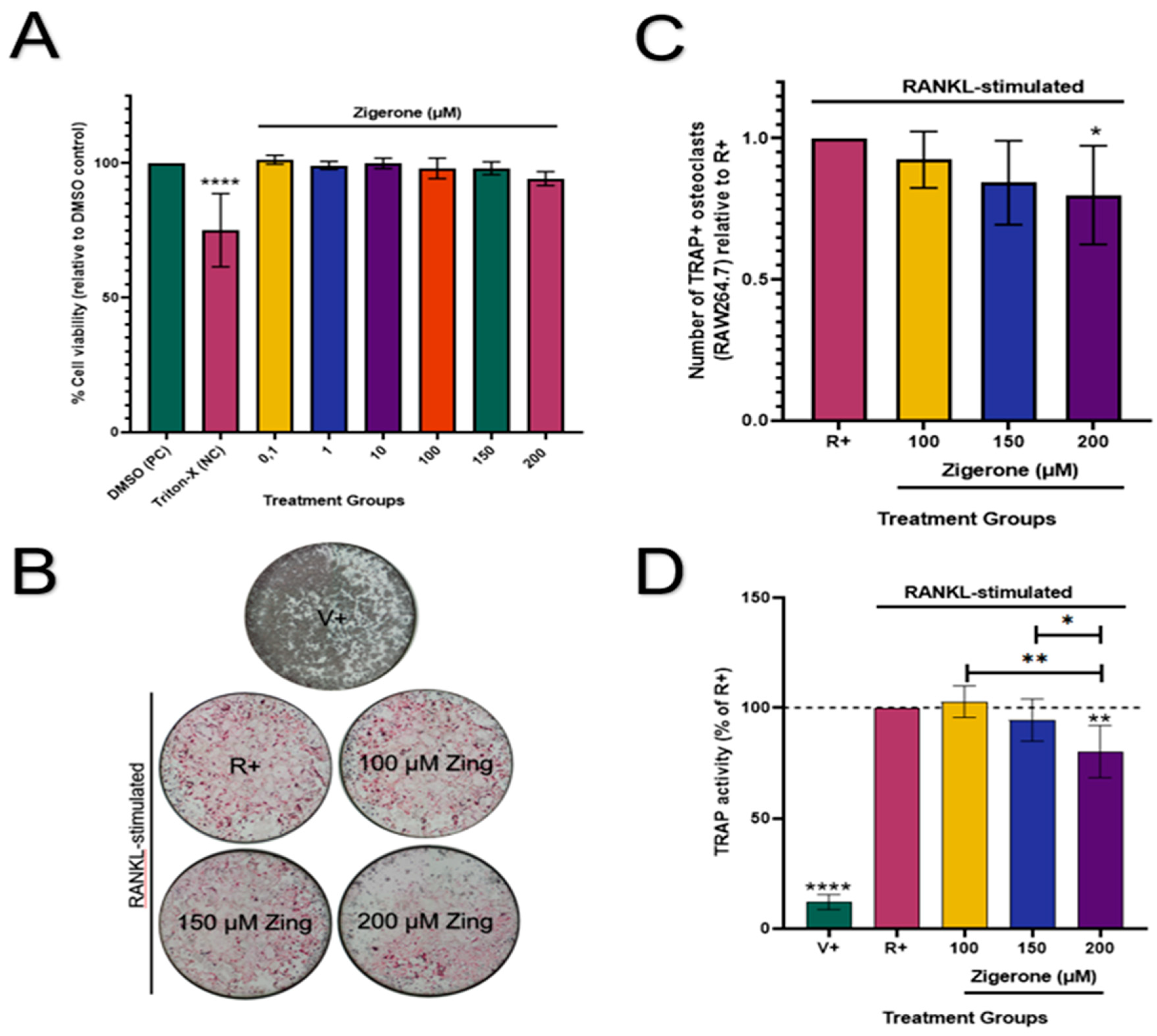

3.3. Zingerone Inhibits Osteoclast Formation and Activity in RAW264.7 Macrophages

Zingerone (0.1-200µM) had no cytotoxic effects on RAW264.7 osteoclast-like cells (

p>0.05;

Figure 3A) when compared to the vehicle. Therefore, these concentrations were used for downstream experiments. Cells that were not treated with RANKL showed no osteoclast formation (

Figure 3B). The number of osteoclasts decreased significantly (20%) in cells treated with 200µM zingerone when compared to the RANKL-positive cells (R+) (

p<0.05;

Figure 3C). Furthermore, TRAP activity was significantly reduced in the absence of RANKL (V+) compared to all treatments (

p<0.0001;

Figure 3D). Consistent with the TRAP staining results (

Figure 3C), treatment with zingerone (200µM) resulted in a significant 19.8% decrease in TRAP activity compared to the positive vehicle R+ (

p<0.05;

Figure 3 D).

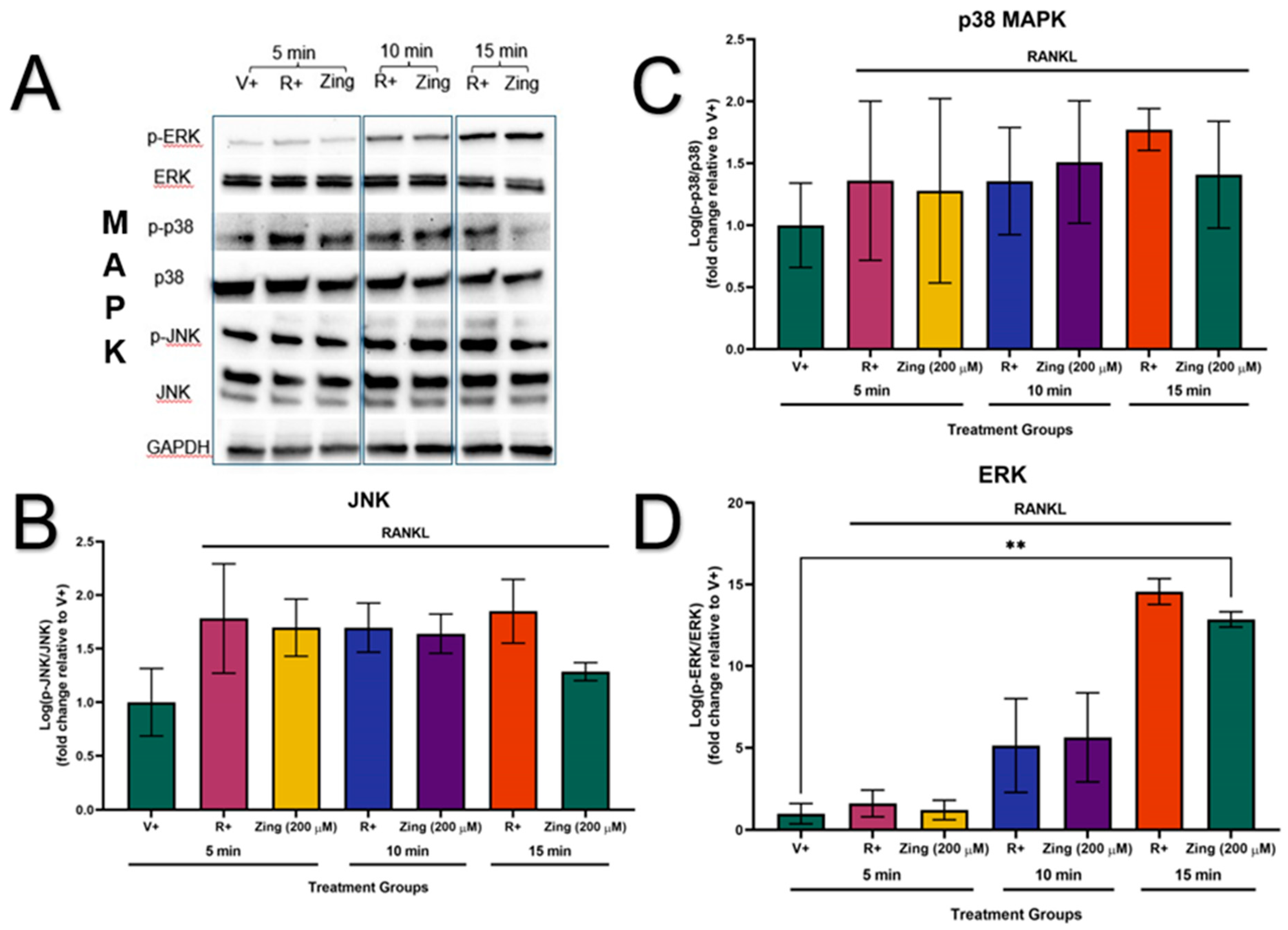

3.4. Western Blotting

The phosphorylation of the MAPK proteins (JNK, p38 and ERK) were not activated in the absence of RANKL-stimulation (V+) (

Figure 4A). The sub-maximal effective concentration of zingerone (200µM) did not decrease the expression of p-JNK/JNK, p-p38/p38, and p-ERK/ERK (p>0.05;

Figure 4B, C and D). However, the membranes showed that zingerone could potentially supress the activation of JNK, p38 and ERK at 15min of RANKL-stimulation compared to their corresponding R+ controls at 15min (

Figure 4A).

4. Discussion

Osteoporosis is a progressive bone degenerative disorder characterized by overactive osteoclasts and underactive osteoblasts. Although drug therapies are available, these are often costly and not readily available to individuals in low-income countries. This study investigated the

in vitro molecular mechanisms of zingerone on bone cells to assess its potential osteoprotective effects in bone health. These cell lines were selected to provide insights into the osteoclast formation and function that are crucial for evaluating therapeutic agents in bone [

29]. Zingerone, constituting approximately 9% of ginger, is known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties suggesting potential benefits for bone health [

35].

In vitro studies, are important for our understanding of cellular processes in a controlled environment. By testing zingerone under different experimental conditions, we contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of its action on both osteoblasts and osteoclasts

in vitro.

Findings from this study showed that zingerone did not significantly enhance SAOS-2 mineralization or ALP activity compared to the control. While there was a slight, non-significant increase in mineralization with 100 and 200µM zingerone from day 7-21, this was not statistically significant. However, zingerone did significantly stimulate

ALP gene expression on days 7 and 14. Despite the high ALP protein in SAOS-2 cells, the increased

ALP gene expression did not translate into higher ALP activity, possibly due to assay saturation or a delay between gene expression and enzyme activity [

25,

36] This inverse relationship between ALP activity and

ALP messenger RNA (mRNA) was also reported by Kyeyune-Nyombi

et al. (1995). These findings suggests that zingerone could potentially advance bone health by influencing bone mineralisation at a genetic level, significantly stimulating

ALP gene expression, without immediately increase ALP protein activity or mineralization. The complexity of the relationship between gene expression and enzyme activity suggests that the osteoprotective effects of zingerone may take longer to manifest or require different conditions, such as other cell lines with lower baseline ALP activity. These insights are crucial for developing targeted therapies for bone health, especially in conditions like osteoporosis. Furthermore, the treatment of SAOS-2 cells with zingerone (200µM) significantly upregulated

Runx2 expression, a key transcription factor in early osteoblast differentiation and mineralization [

20]. Despite this increase in

Runx2 gene expression, zingerone did not significantly enhance mineralisation or affect the expression levels of

OC, another marker linked to late stage osteoblastogenesis [

37]. This could suggest that the effects of zingerone are more specific to the early stages of osteoblast differentiation as indicated by the upregulation of

ALP and

Runx2 gene expression, without directly influencing later stages of differentiation. The lack of effect on

OC expression highlights the complexity of its role in bone formation, warranting further studies to understand the mechanism [

14,

38].

The mechanism of action of zingerone was further evaluated in an osteoclast-like cell model using RAW264.7 murine macrophages [

39]. Osteoclast differentiation was induced by RANKL-stimulation (5ng/mL) to achieve a more sensitive measurement of osteoclast activity without overwhelming the system, while 15 ng/mL RANKL was used in western blots to ensure robust protein expression for clear detection of key signaling molecules and differentiation markers. The difference in RANKL concentration reflects the distinct goals and sensitivity requirements of each experimental approach. Decreased concentrations of RANKL allowed for a more nuanced and controlled study of zingerone's effects on osteoclast differentiation in RAW264.7 cells. Studies have reported effective osteoclast differentiation in RAW264.7 cells with RANKL concentrations ranging between 0.5 to 100ng/mL [

40,

41]. Zingerone (200µM) effectively inhibited RANKL-induced TRAP activity and significantly reduced the number of osteoclast-like TRAP-positive cells. Similar reports have shown that zingerone (150-600µM) significantly inhibited the activity of TRAP in RAW264.7 cells [19]. This is contrary to our study that indicated cytotoxic effects on RAW264.7 cells when treated with zingerone above 200µM. This inhibition effect by Yang

et al. (2023) might be attributed to laboratory-specific environmental factors and not necessarily to the ability of zingerone to inhibit osteoclastogenesis [

19]. Some discrepancies may be attributed to genetic and epigenetic cellular variabilityand the purity and source of zingerone [

19]. Moreover, the same study that reported the inhibition effect on TRAP activity has also indicated that zingerone successfully attenuated MAPK signaling pathways in RAW264.7 cells [

19]. The ability of zingerone to suppress osteoclast function suggests potential benefits for conditions involving excessive bone resorption like osteoporosis. Our study indicated no significant differences in the expression levels of

p-JNK/JNK,

p-p38/p38, and

p-ERK/ERK with or without zingerone treatment. The discrepancies between studies may be due to differences in culture media and content [

42,

43]. Studies have shown that media supplementation with antibiotics such as penicillin-streptomycin (PenStrip) can significantly alter gene expression and transcription factors [

42,

43]. In our study, we avoided these potential metabolic effects by excluding antibiotics from the culture medium. In contrast, Yang

et al. (2023) not only used a different culture medium but also supplemented alpha-Minimum Essential Medium Eagle (MEM) with 1% PenStrip which may have affected the expression of MAPK signalling pathways [

42,

43].

The effects of zingerone on bone metabolism are multifaceted and involve a combination of antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and direct effects on bone cells. By addressing these specific areas, our study contributes to the growing body of knowledge on zingerone and its potential role in bone cells, while also offering novel perspectives and experimental insights that could inspire further research in the field. The overall effect of zingerone on bone health depends on its concentration, duration of exposure, and interaction with other factors (culture medium; cell line; cell density) affecting bone metabolism. Further research, including preclinical studies are needed to fully understand the mechanism underlying the effect of zingerone on bone health and its potential application in humans.

5. Conclusions

We have shown that zingerone exhibits moderate potential as a therapeutic agent for bone health by effectively reducing RAW264.7 differentiation through targeted pathways and factors, while not directly stimulating later stages of mineralisation in SAOS-2 osteosarcoma cells. Our findings suggest that, at a concentration of 200µM, zingerone has the potential to reduce osteoclast differentiation and enhance the expression of key genes involved in osteoblast differentiation. However, its impact on MAPK signalling in osteoclasts and later stages of osteoblast differentiation or maturation was less potent. Our findings suggest an alternative hypothesis regarding how zingerone affects bone metabolism, particularly in relation to cell viability and differentiation at higher concentrations. While prior research has focused on its osteoclast-inhibiting properties, we explore whether these effects could extend to other bone-related processes or cell types. The moderate anti-osteoclastic effects of zingerone suggest that it may potentially aid in preserving bone mass by reducing bone resorption. The mechanism of action exhibited by zingerone in the current study provides new insights into how zingerone modulates bone cell activity. These findings highlight the potential of zingerone as a dietary supplement for maintaining bone health. However further research, including its underlying mechanisms for bone-related disorders and in vivo and clinical studies, is necessary to fully understand its clinical relevance and the mechanisms involved in maintaining bone health.

Author Contributions

TN, AK, and AJ conceived the study. BDV performed the experiments and data analyses with AK assisting in data analysis. BDV wrote the final draft which all authors read and approved.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Research Foundation of South Africa, grant number 121828).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This preclinical study was ethically approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of Pretoria (ethics number: 491/2022).

Data Availability Statement

Data available on reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest between authors.

References

- Pouresmaeili F, Kamalidehghan B, Kamarehei M, Goh YM. A comprehensive overview on osteoporosis and its risk factors. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2018, 14, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sozen T, Ozisik L, Basaran NC. An overview and management of osteoporosis. Eur J Rheumatol. 2017, 4, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coughlan T, Dockery F. Osteoporosis and fracture risk in older people. Clin Med (Lond). 2014, 14, 187–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foger-Samwald U, Dovjak P, Azizi-Semrad U, Kerschan-Schindl K, Pietschmann P. Osteoporosis: Pathophysiology and therapeutic options. EXCLI J. 2020, 19, 1017–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasonga AE, Deepak V, Kruger MC, Coetzee M. Arachidonic acid and docosahexaenoic acid suppress osteoclast formation and activity in human CD14+ monocytes, in vitro. PLoS One. 2015, 10, e0125145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shyu JF, Liu WC, Zheng CM, Fang TC, Hou YC, Chang CT, Liao TY, Chen YC, Lu KC. Toxic effects of indoxyl sulfate on osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis. Toxic effects of indoxyl sulfate on osteoclastogenesis and osteoblastogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee K, Seo I, Choi MH. Roles of mitogen-activated protein kinases in osteoclast biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2018, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li L, Sapkota M, Gao M, Choi H, Soh Y. Macrolactin F inhibits RANKL-mediated osteoclastogenesis by suppressing Akt, MAPK and NFATc1 pathways and promotes osteoblastogenesis through a BMP-2/smad/Akt/Runx2 signaling pathway. Eur J Pharmacol. 2017, 815, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim K, Lee SH, Ha Kim J, Choi Y, Kim N. NFATc1 induces osteoclast fusion via up-regulation of Atp6v0d2 and the dendritic cell-specific transmembrane protein (DC-STAMP). Mol Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 176–185. [CrossRef]

- Park E, Lee CG, Lim E. Osteoprotective effects of loganic acid on osteoblastic and osteoclastic cells and osteoporosis-induced mice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu TM, Lee EH. Transcriptional regulatory cascades in Runx2-dependent bone development. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2013, 19, 254–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maruyama Z, Yoshida CA, Furuichi T, Amizuka N, Ito M, Fukuyama R, Miyazaki T, Kitaura H, Nakamura K, Fujita T. Runx2 determines bone maturity and turnover rate in postnatal bone development and is involved in bone loss in estrogen deficiency. Developmental dynamics: an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2007, 236, 1876–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ansari S, Ito K, Hofmann S. Alkaline phosphatase activity of serum affects osteogenic differentiation cultures. ACS Omega. 2022, 7, 12724–12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao YT, Huang YJ, Wu HH, Liu YA, Liu YS, Lee OK. Osteocalcin mediates biomineralization during osteogenic maturation in human mesenchymal stromal cells. Osteocalcin mediates biomineralization during osteogenic maturation in human mesenchymal stromal cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2017, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florencio-Silva R, Sasso GRdS, Sasso-Cerri E, Simões MJ, Cerri PS. Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed Research International. 2015, 2015, 421746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani V, Arivalagan S, Siddique AI, Namasivayam N. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory role of zingerone in ethanol-induced hepatotoxicity. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016, 421, 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad B, Rehman MU, Amin I, Mir MUR, Ahmad SB, Farooq A, Muzamil S, Hussain I, Masoodi M, Fatima B. Zingerone (4-(4-hydroxy-3-methylphenyl) butan-2-one) protects against alloxan-induced diabetes via alleviation of oxidative stress and inflammation: probable role of NF-kB activation. Saudi Pharm J. 2018, 26, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song Y, Mou R, Li Y, Yang T. Zingerone promotes osteoblast differentiation via MiR-200c-3p/smad7 regulatory axis in human bone mesenchymal stem cells. Med Sci Monit. 2020, 26, e919309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang D, Tan Y, Xie X, Xiao W, Kang J. Zingerone attenuates Ti particle-induced inflammatory osteolysis by suppressing the NF-κB signaling pathway in osteoclasts. Int Immunopharmacol. 2023, 115, 109720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinaath N, Balagangadharan K, Pooja V, Paarkavi U, Trishla A, Selvamurugan N. Osteogenic potential of zingerone, a phenolic compound in mouse mesenchymal stem cells. Biofactors. 2019, 45, 575–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginaldi L, Di Benedetto MC, De Martinis M. Osteoporosis, inflammation and ageing. Immun Ageing. 2005, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman MU, Rashid SM, Rasool S, Shakeel S, Ahmad B, Ahmad SB, Madkhali H, Ganaie MA, Majid S, Bhat SA. Zingerone (4-(4-hydroxy-3-methylphenyl)butan-2-one) ameliorates renal function via controlling oxidative burst and inflammation in experimental diabetic nephropathy. Arch Physiol Biochem. 2019, 125, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsabadi S, Nazer Y, Ghasemi J, Mahzoon E, Baradaran Rahimi V, Ajiboye BO, Askari VR. Promising influences of zingerone against natural and chemical toxins: a comprehensive and mechanistic review. Toxicon. 2023, 233, 107247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodan SB, Imai Y, Thiede MA, Wesolowski G, Thompson D, Bar-Shavit Z, Shull S, Mann K, Rodan GA. Characterization of a human osteosarcoma cell line (SAOS-2) with osteoblastic properties. Cancer Res. 1987, 47, 4961–4966. [Google Scholar]

- Dvorakova J, Wiesnerova L, Chocholata P, Kulda V, Landsmann L, Cedikova M, Kripnerova M, Eberlova L, Babuska V. Human cells with osteogenic potential in bone tissue research. Biomed Eng Online. 2023, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis KS, Siegel AC. Cell viability analysis using trypan blue: manual and automated methods. Methods Mol Biol. 2011, 740, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strober, W. Trypan blue exclusion test of cell viability. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2015, 111, A3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taciak B, Białasek M, Braniewska A, Sas Z, Sawicka P, Kiraga Ł, Rygiel T, Król M. Evaluation of phenotypic and functional stability of RAW 264.7 cell line through serial passages. PLoS One. 2018, 13, e0198943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong L, Smith W, Hao D. Overview of RAW264.7 for osteoclastogensis study: phenotype and stimuli. J Cell Mol Med. 2019, 23, 3077–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasonga A, Kruger MC, Coetzee M. Activation of PPARs modulates signalling pathways and expression of regulatory genes in osteoclasts derived from human CD14+ monocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 1798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nasiry S, Geusens N, Hanssens M, Luyten C, Pijnenborg R. The use of Alamar Blue assay for quantitative analysis of viability, migration and invasion of choriocarcinoma cells. Hum Reprod. 2007, 22, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sagar T, Kasonga A, Baschant U. Aspalathin from Aspalathus linearis (rooibos) reduces osteoclast activity and increases osteoblast activity in vitro. J Funct Foods. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akchurin T, Aissiou T, Kemeny N, Prosk E, Nigam N, Komarova SV. Complex dynamics of osteoclast formation and death in long-term cultures. PLoS One. 2008, 3, e2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012, 9, 671–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad B, Rehman MU, Amin I, Arif A, Rasool S, Bhat SA, Afzal I, Hussain I, Bilal S, Mir M. A review on pharmacological properties of zingerone (4-(4-Hydroxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-2-butanone). ScientificWorldJournal. 2015, 2015, 816364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyeyune-Nyombi E, Nicolas V, Strong DD, Farley J. Paradoxical effects of phosphate to directly regulate the level of skeletal alkaline phosphatase activity in human osteosarcoma (SaOS-2) cells and inversely regulate the level of skeletal alkaline phosphatase mRNA. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995, 56, 154–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Bari AA, Al Mamun A. Current advances in regulation of bone homeostasis. FASEB Bioadv. 2020, 2, 668–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neve A, Corrado A, Cantatore FP. Osteocalcin: skeletal and extra-skeletal effects. J Cell Physiol. 2013, 228, 1149–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borciani G, Montalbano G, Baldini N, Cerqueni G, Vitale-Brovarone C, Ciapetti G. Co-culture systems of osteoblasts and osteoclasts: Simulating in vitro bone remodeling in regenerative approaches. Acta Biomater. 2020, 108, 22–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skubica P, Husakova M, Dankova P. In vitro osteoclastogenesis in autoimmune diseases - strengths and pitfalls of a tool for studying pathological bone resorption and other disease characteristics. Heliyon. 2023, 9, e21925. [CrossRef]

- Cheng Y, Liu H, Li J, Ma Y, Song C, Wang Y, Li P, Chen Y, Zhang Z. Evaluation of culture conditions for osteoclastogenesis in RAW264.7 cells. PLoS One. 2022, 17, e0277871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu AH, Eckalbar WL, Kreimer A, Yosef N, Ahituv N. Use antibiotics in cell culture with caution: genome-wide identification of antibiotic-induced changes in gene expression and regulation. Sci Rep. 2017, 7, 7533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch C, Schildknecht S. In vitro research reproducibility: keeping up high standards. Front Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 1484. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).