Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dumitrescu, Magdalena; Iliescu, Gabriela Madalina; Mazilu, Laura; Micu, S.I.; Suceveanu, A.P.; Voinea, F.; Voinea Claudia; Stoian-Pantea, Anca; Suceveanu, Andra-Iulia. Benefits of crenotherapy in digestive tract pathology. Exp Ther Med 2022, 23, 122. [CrossRef]

- Ziemska, Joanna; Szynal, T.; Mazańska, M.; Solecka, J. Natural medicinal resources and their therapeutic applications, Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2019, 70(4), 407-413.

- Savulescu-Fiedler, I.; Mihalcea, R.; Dragosloveanu, S.; Scheau, C.; Baz, R.O.; Caruntu, A.; Scheau, A.-E.; Caruntu, C.; Benea, S.N. The Interplay between Obesity and Inflammation. Life 2024, 14, 856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dragosloveanu, S.; Capitanu, B.-S.; Josanu, R.; Vulpe, D.; Cergan, R.; Scheau, C. Radiological Assessment of Coronal Plane Alignment of the Knee Phenotypes in the Romanian Population. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 4223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Periferakis, A.; Periferakis, A.-T.; Troumpata, L.; Dragosloveanu, S.; Timofticiuc, I.-A.; Georgatos-Garcia, S.; Scheau, A.-E.; Periferakis, K.; Caruntu, A.; Badarau, I.A.; et al. Use of Biomaterials in 3D Printing as a Solution to Microbial Infections in Arthroplasty and Osseous Reconstruction. Biomimetics 2024, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gere, Dóra; Róka, Eszte; Záray, G. ; Varga, Márta. Disinfection of Therapeutic Spa Waters: Applicability of Sodium Hypochlorite and Hydrogen Peroxide-Based Disinfectants, Water 2022, 14, 690.

- Lebaron, P. Thermal waters: when minerality and biological signature combine to explain their properties, Ann Dermatol Venereol 2020, 147(15), 1520-1524.

- Kulikov, A.G.; Turova, E.A. Drinking mineral waters: problematic issues and prospects of use in treatment and rehabilitation, Vopr Kurortol Fizioter Lech Fiz Kult. 2021, 98(6),.54-60. https://doi.org./10. 1711. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez, Maria; Fernandez-Lao, Carolina; Martin-martin, Lydia; Gonzalez-Santos, Angela; Lopez-Garzon, Maria; Ortiz-Comino, Lucia; Lozano-Lozano, M. Therapeutic benefits of Balneotherapy on Quality of Life of Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review, Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021, 18(24), 13216. [CrossRef]

- Curuţiu, Carmen; Iordache, F; Gurban Petruţ; Lazăr, Veronica; Chifiriuc, Mariana- Carmen. Main Microbiological Pollutants of Bottled Waters and Beverages, Bottles and Packaged Water, Woodhead Publishing Bucharest, Romania, 2019, pp. 403-422. [CrossRef]

- Platzer, Sabine; Baumert, Rita; Reinthaler, F.; Kopeinig-Ofner, Petra (Eds.) ; Inwinkl, Sarah, Maria; Platzer, Sabine; Baumert, Rita; Reinthaler, F.; Kopeinig-Ofner, Petra (Eds.) Hass, Dora. Cefsulodin and Vancomycin: A Supplement for Cromogenic Coliform Agar for Detection of Escherichia coli and Coliform Bacteria from Different Water Sources, Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2499.

- Aram Appah, S.; Saalidong, M.B.; Lartey, O.P. Comparative assessment of the relationship between coliform bacteria and water geochemistry in surface and ground water systems, PLoS ONE 2021, 16(9). [CrossRef]

- Reitter, Carolin; Petzoldt, H.; Korth, A.; Schwab, F.; Stange, Claudia; Hambsch, B.; Tiehm, A.; Lagkouvardos, I.; Gescher, J.; Hügler, M. Seasonal dynamics in the number and composition of coliform bacteria in drinking water reservoirs, Sci Total Environ 2021, 787. [CrossRef]

- Purohit, M.; Diwan, V.; Parashar, V.; Tamhankar, A.J.; Stålsby Lundborg, C. Mass bathing events in River KShipra, central India- influence on the water quality and the antibiotic susceptibility patter of commensal E.coli, PloS ONE 2020, 15(3).

- Pokharel, P.; Dhakal, S.; Dozois, C.M. The Diversity of Escherichia coli Pathotypes and Vaccination Strategies against This Versatile Bacterial Pathogen, Microorganisms 2023, 11, 344. 11. [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.H.R.; Dutra, M.L.S.; Lima, N.S.; da Sila, G.M.; de Miranda, R.C.M.; Firmo, W.C.A.; de Moura, A.R.L.; Monteiro, A.S.; da Silva, L.C.N.; da Silva, D.F.; Silva, M.R.C. Study of the Influence of Physicochemical Parameters on the Water Quality Index (WQI) in the Maranhão Amazon, Brazil, Water 2022, 14, 1546. 14,. [CrossRef]

- Jang, C-S. Aquifer vulnerability assessment for fecal coliform bacteria using multi-threshold logistic regression, Environ Monit Assess 2022, 194(10), 800. [CrossRef]

- Behruznia, M.; Gordon, D.M. Molecular and metabolic characteristics of wastewater associated Escherichia coli strains, Env Microbiol Rep 2022, 14(4), 646-654. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.S.; Islam, M.; Hassan, M.; Bilal, H.; Ali Shah, I.; Ourania, T. Modeling the fecal contamination (fecal coliform bacteria) in transboundary waters using the scenario matrix approach: a case study of Sutlej River, Pakistan, Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2022, 52, 79555-79566. [CrossRef]

- SR EN ISO Standard, No. 10523:2012. Water quality. Determination of pH. The Romanian Standardization Association, Bucharest, Romania, 2012.

- SR EN Standard, No. 27888:1997. Water quality. Determination of electrical conductivity. The Romanian Standardization Association, Bucharest, Romania, 1997.

- Kaynar, P.M.; Demli, P.; Orhan, G.; Ilter, H. Chemical and microbiological assessment of drinking water quality, Afr Health Sci 2022, 22(4), 648-652. [CrossRef]

- SR EN ISO Standard No. 19458:2007 Water quality. Sampling for microbiological analysis. The Romanian Standardization Association, Bucharest, Romania, 2007.

- SR EN ISO Standard No. 9308-1:2015/A1:2017. Water quality. Enumeration of Escherichia coli and coliform bacteria. Part 1: Membrane filtration method for waters with low bacterial background flora. The Romanian Standardization Association, Bucharest, Romania, 2017.

- Kosińska B, Grabowski ML. Sulfurous Balneotherapy in Poland: A Vignette on History and Contemporary Use. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1211:51-59. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aram Appah, S.; Saalidong, M.B.; Lartey, O.P. Comparative assessment of the relationship between coliform bacteria and water geochemistry in surface and ground water systems, PLoS ONE 2021, 16(9).

- Kemper, M.A.; Veenman, C.; Blakk, H.; Schets, Franciska M. A membrane filtration method for the enumeration of Escherichia coli in bathing water and other waters with high levels of background bacteria, J.Water Health 2023, 21(8), 995-1003.

- Maphanga, T.; Madonsela, B.S.; Chidi, B.S.; Shale, K.; Munjonji, L.; Lekata, S. The effect of Rainfall on Escherichia coli and Chemical Oxygen Demand in the Effluent Discharge from the Crocodile River Wastewater Treatment; South Africa, Water 2022, 14, 2802.

- Zaorska, Ewelina; Tomasova, Lenka; Koszelewski, D.; Ostaszewski, R.; Ufnal, M. Hydrogen Sulfide in Pharmacotherapy, Beyond the Hydrogen Sulfide-Donors, Biomol 2020, 10(323).

- Karagülle, M-Z.; Karagülle, M. Effects of drinking natural hydrogen sulfide (H2S) waters: a systematic review of in vivo animal studies, Int J Biometeorol 2020, 64(6), 1011-1022.

- Bazharov, N.; Escaffre, O.; Freiberg A.N. Broad-range antiviral activity of hydrogen sulfide against highly pathogenic RNA viruses, Sci Rep 2017, 7:41029.

- Bailly, Mélina; Evrard, B.; Coudeyre, E.; Rochette, Corrine; Meriade, L.; Blavignac, C.; Fournier, Anne-Cécile; Bignon, Y-J.; Duthell, F.; Duclos, M. Health management of patients with COVID-19: is there a room for hydrotherapeutic approaches ?, Int.J.Biometeorol 2022, 66, 1031-1038.

- Pozzi, Giulia; Masselli, Elena; Gobbi, Giuliana; Mirandola, P.; Taborda-Barata, L.; Ampollini, L.; Carbognani, P.; Micheloni, Cristina; Corazza, F.; Galli, Daniela; Carubbi, Cecilia; Vitale, M. Hydrogen Sulfide Inhibits TMPRSS2 in Human Airway Epithelial Cells: Implications for SARS-Cov-2 Infection, Biomedicines 2021, 9(9), 1273.

- Nola, M.; Njine, T.; Djulkom E.; Foko, V.S. Faecal coliforms and faecal streptococci community in the underground water in an equatorial area in Cameroon (Central Africa): the importance of some environmental chemical factors, Water Res. 2002, 36(13), 3289-97.

- Schalli, M.; Platzer, Sabine; Haas, Doris; Reinthaler, F.F. The behavior of Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in bottled mineral water, Heliyon 2023, 9(11).

- Thuy Do, Q. T.; Otaki, M.; Otaki, Y.; Tushara, C.; Sanjeewa, I. W. Pharmaceutical Contaminants in Shallow Groundwater and Their Implication for Poor Sanitation Facilities in Low-Income Countries, Environ Toxicol Chem 2022, 41(2), 266-274.

- Shaban J.; Al-Najar, H.; Kocadal K.; Almghari K.; Saygi, S. The effect of Nitrate-Contaminated Drinking Water and Vegetables on the Prevalence of Acquired Methemoglobinemia in Beit Lahia City in Palestine, Water 2023, 15, 1989.

- Kazemitabar, S.M.; Amirnezhad, R.; Rahnavard, A.; Fahimi, F. Exploring Relationships between Fecal Coliforms and Enterococci Groups as Microbial Indicators in Recreational Coastal Waters in Eastern Mazandaran, Iran-the Caspian Sea, Pol.J.Environ.Stud. 2021, 30(6), 5909-5915.

- Ramos-Ramirez, L.D.C; Romero-Bañuelos, C.A.; Jiménez-Ruiz, E.I.; Palomino-Hermosillo, Y.A.; Saldaña-Ahuactzi, Z.; Martinez-Laguna, Y.; Handal-Silva, A.; Castañeda-Roldán, E.I. Coliform Bacteria in San Pedro Lake, western Mexico, Water Environ Res 2021, 93(3), 384-392.

- Tiwari, A.; Oliver, D.M.; Bivins, A.; Sherchan, S.P.; Pitkȁnen, Taria Bathing Water Quality Monitoring Practices in Europe and the United States, Int.J. Environ.Res.Public Health 2021, 18, 5513.

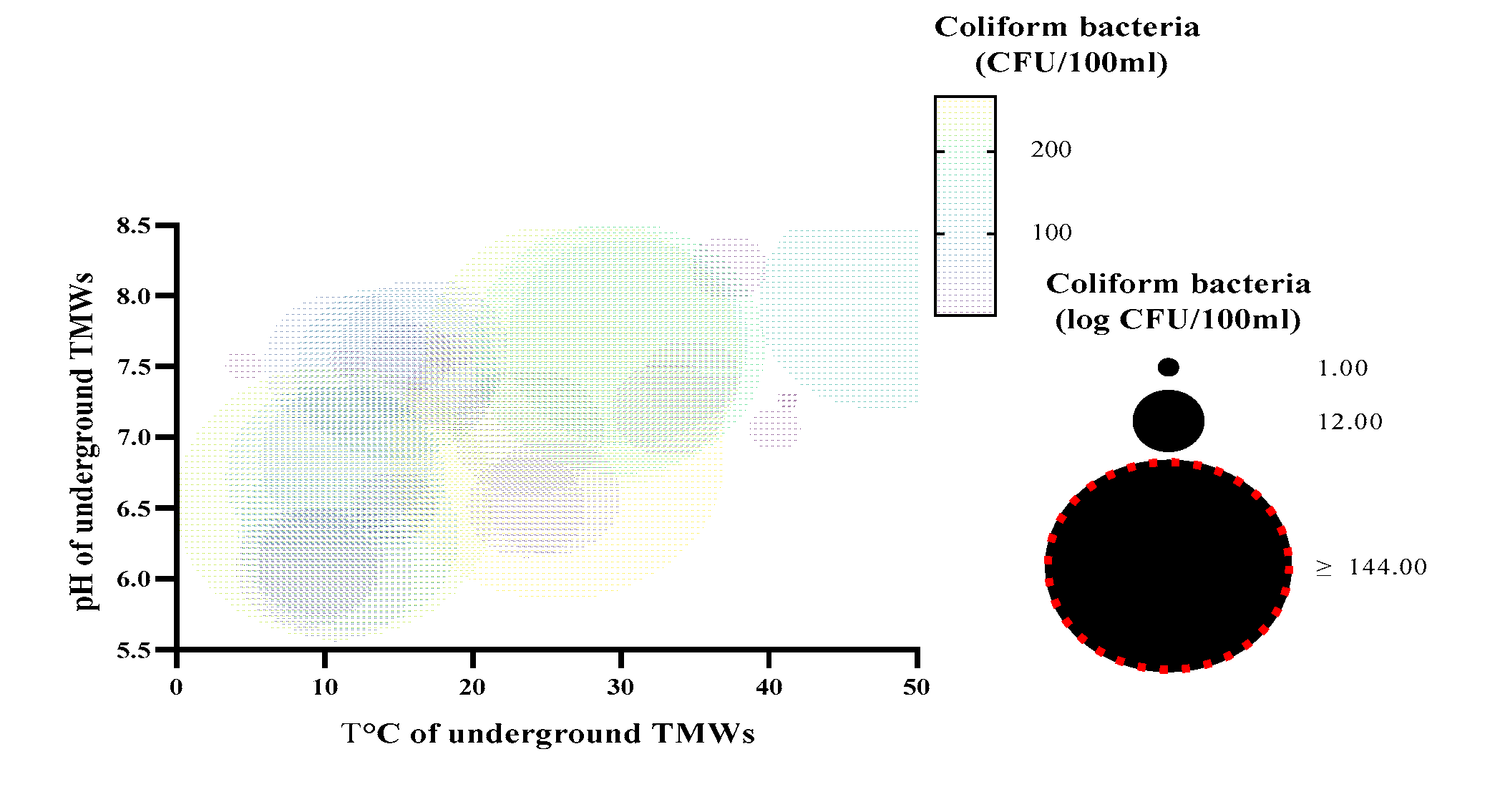

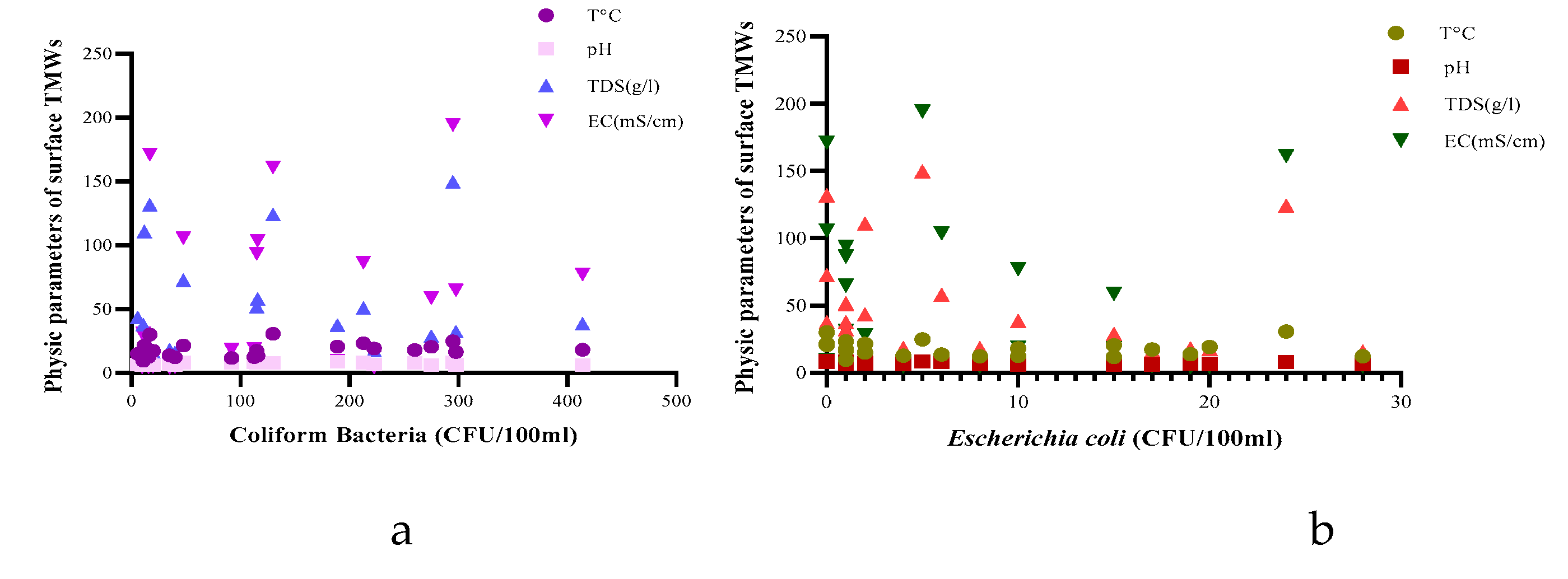

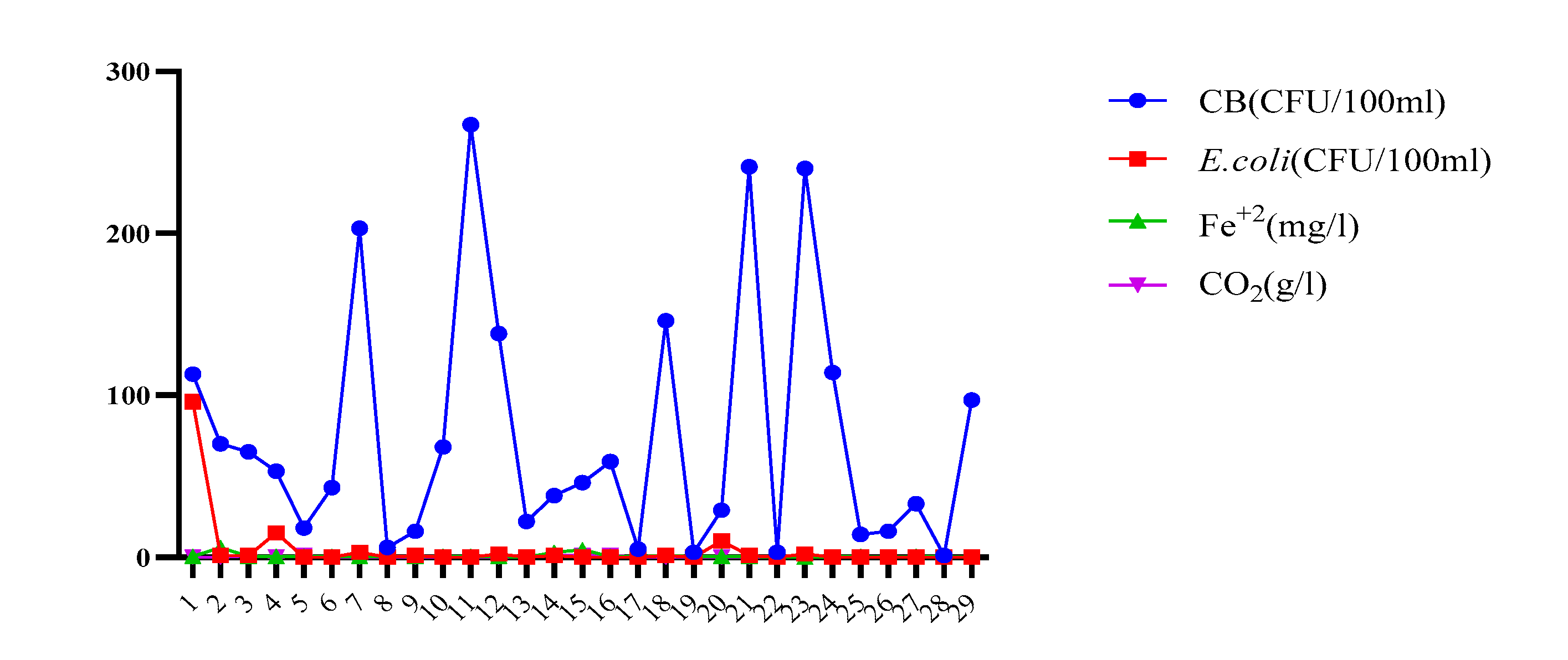

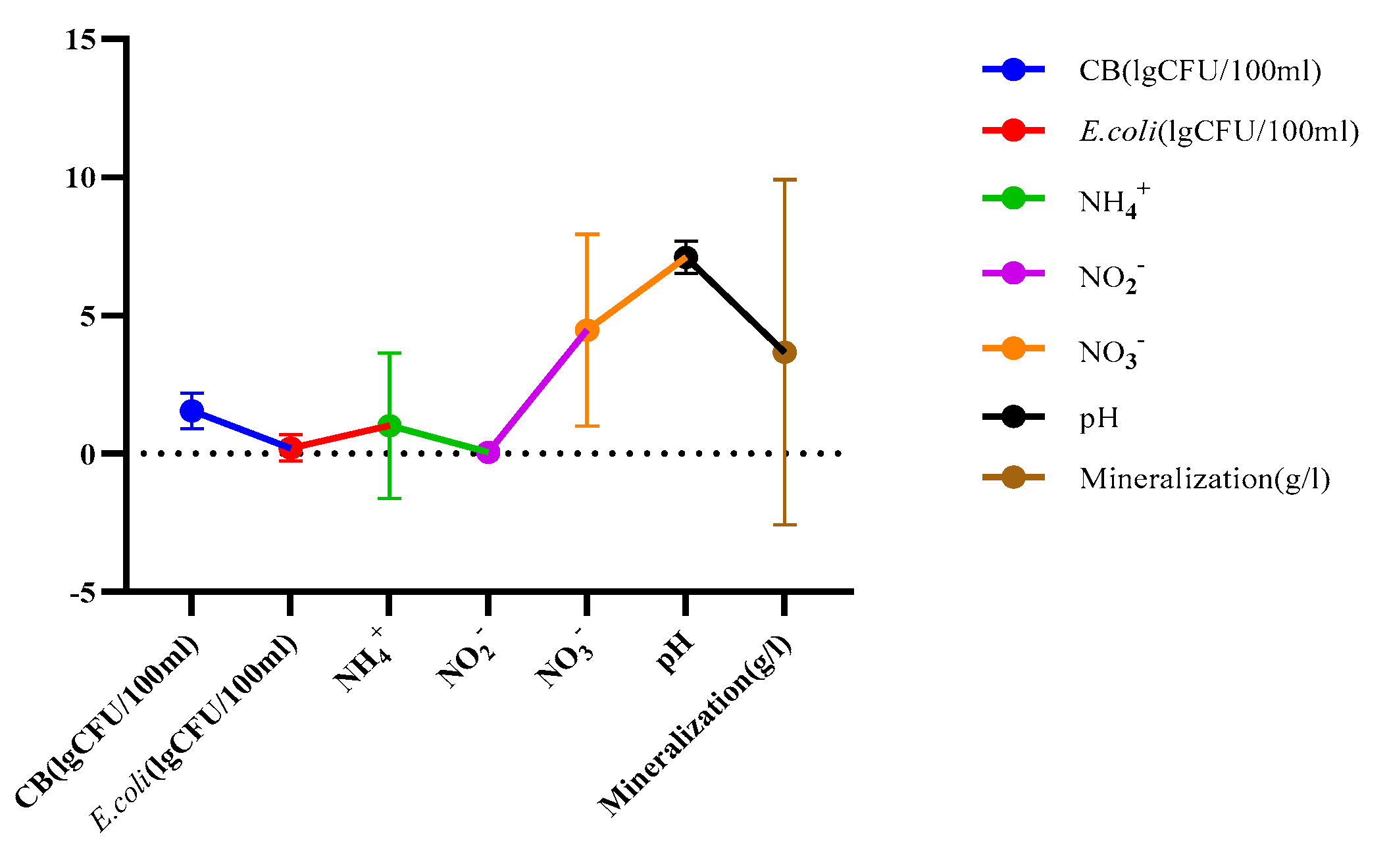

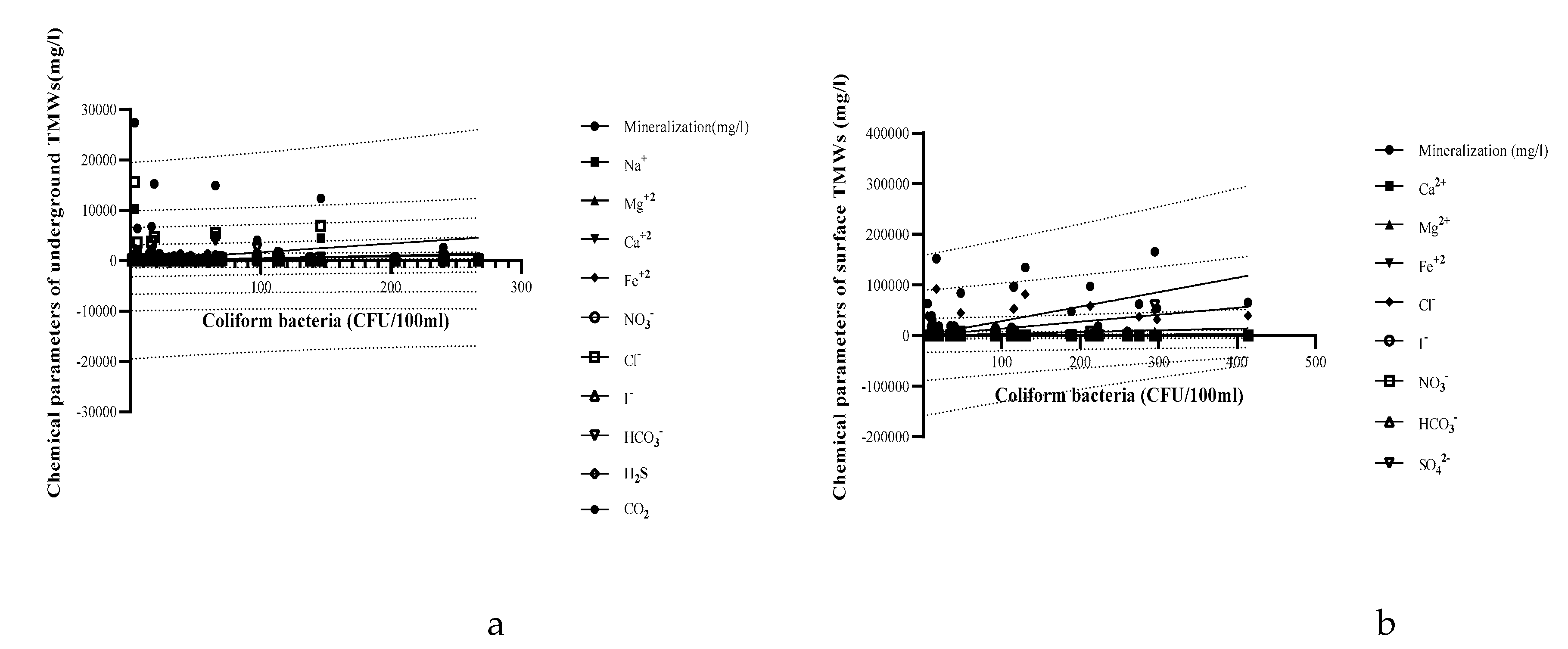

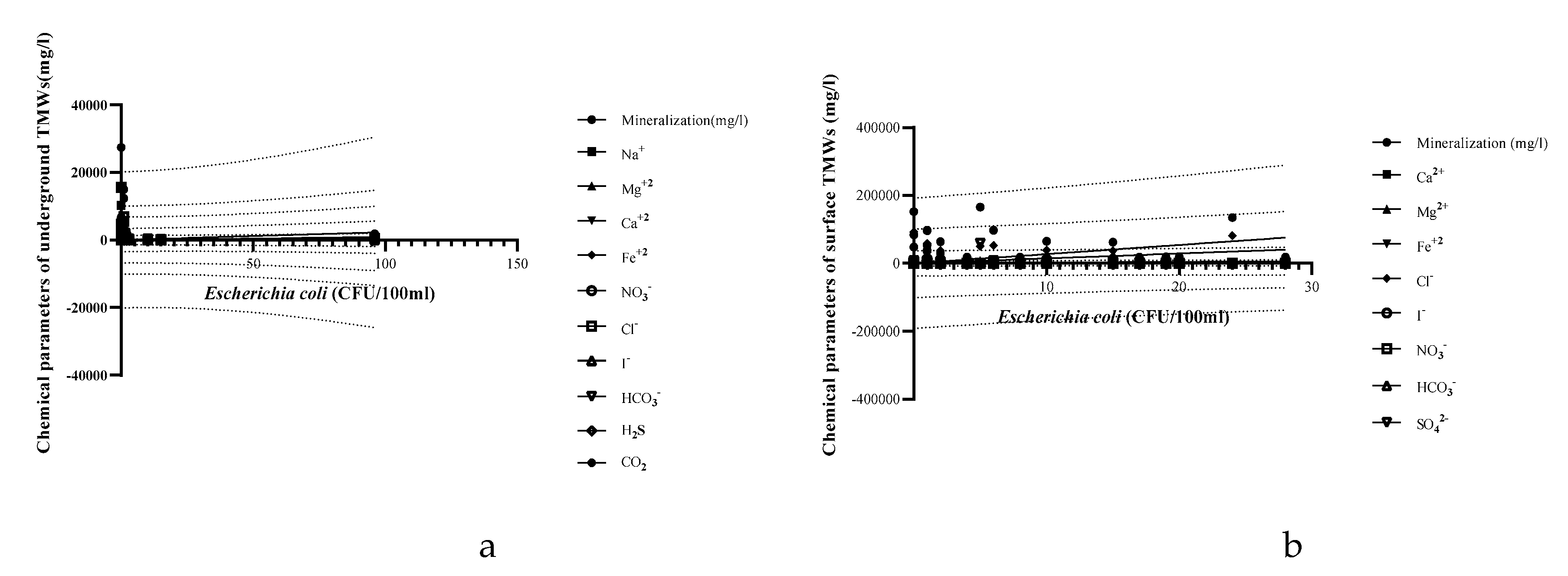

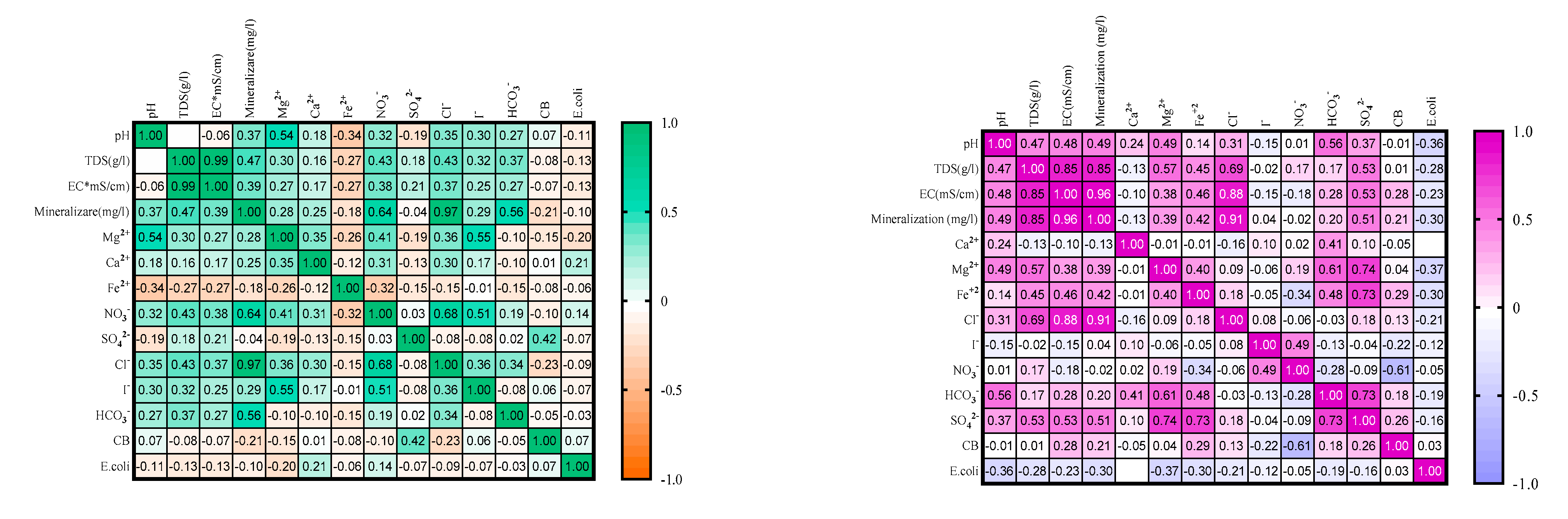

| Parameters | Underground TMWs (spring, well, drilling) N=29 |

Surface TMWs (natural lake, bathing basin) N=23 |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Min/Max/SD | Min/Max/SD |

| Temperature (°C) pH Total dissolve solids (g/l) Electrical Conductivity (mS/cm) |

4.5/47.6/11.34 6.04/8.2/0.58 |

9.7/30.7/5.53 6.08/8.94/0.95 |

| 0.24/14.94/4.19 | 9.15/149.61/41.01 | |

| 0.19/16.76/2.6 | 4.2/194.3/57.87 | |

| Chemical | ||

| Total Mineralization (g/l) | 0.25/27.44/6.13 | 8.11/165.80/45.91 |

| Cations | ||

| Na+ (g/l) Ca2+(mg/l) Mg2+ (mg/l) Fe+2(mg/l) NH4+(mg/l) |

0.012.7/1.03/2.29 | 1.95/59.32/17.09 |

| 16.1/234.1/53.32 0.5/79.7/33.38 0.05/6.1/1.33 0.06/12.2/2.58 |

32.1/3935.7/770.22 25.3/7898.1/2166.16 0.05/2.1/0.49 Abs* |

|

| Anions | ||

| Cl-(g/l) I-(mg/l) NO2-(mg/l) NO3-(mg/l) HCO3-(mg/l) SO42-(mg/l) |

0.018/15.61/3.27 | 0.027/92.18/25.98 |

| 0.1/6.6/0.46 | 0.1/1.2/0.22 | |

| 0.06/0.1/0.06 | Abs | |

| 0.06/12.5/3.41 48.8/4148.1/991.97 2.4/652.3/167.3 |

2.5/20.1/3.94 146.4/1189.1/268.2 28.4/59800.1/11979.2 |

|

| Gas | ||

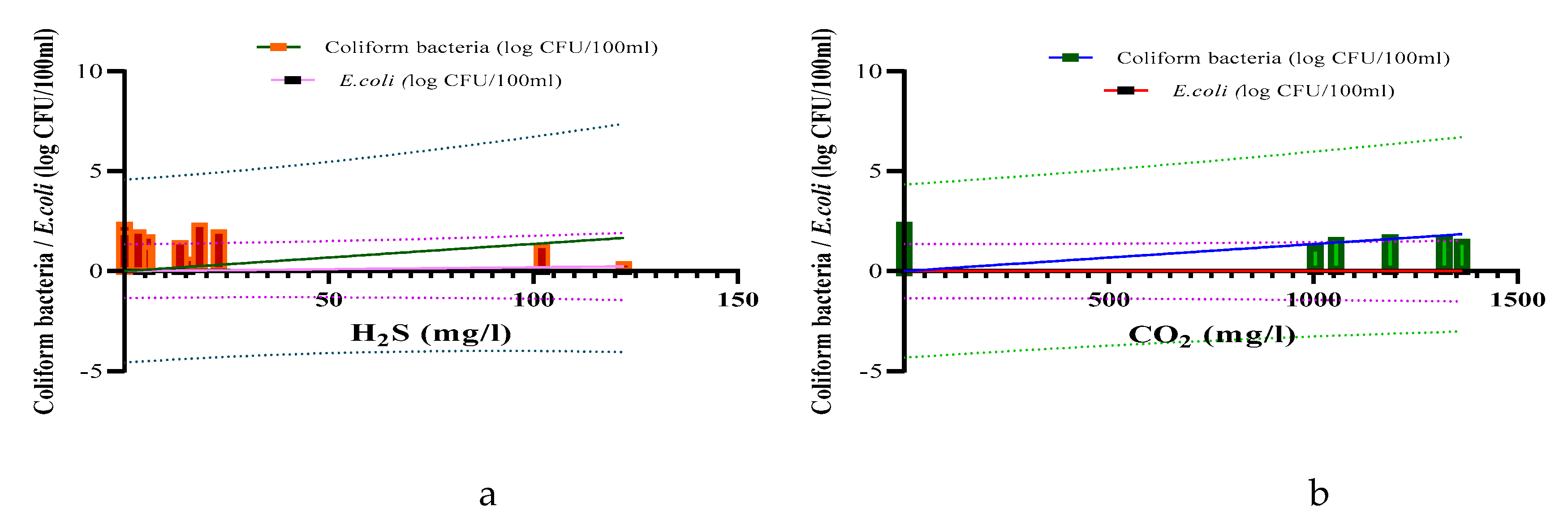

| H2S(mg/l) CO2(mg/l) |

Abs/122.1/28.26 Abs/1364.1/452.05 |

Abs Abs |

| Microbiological | ||

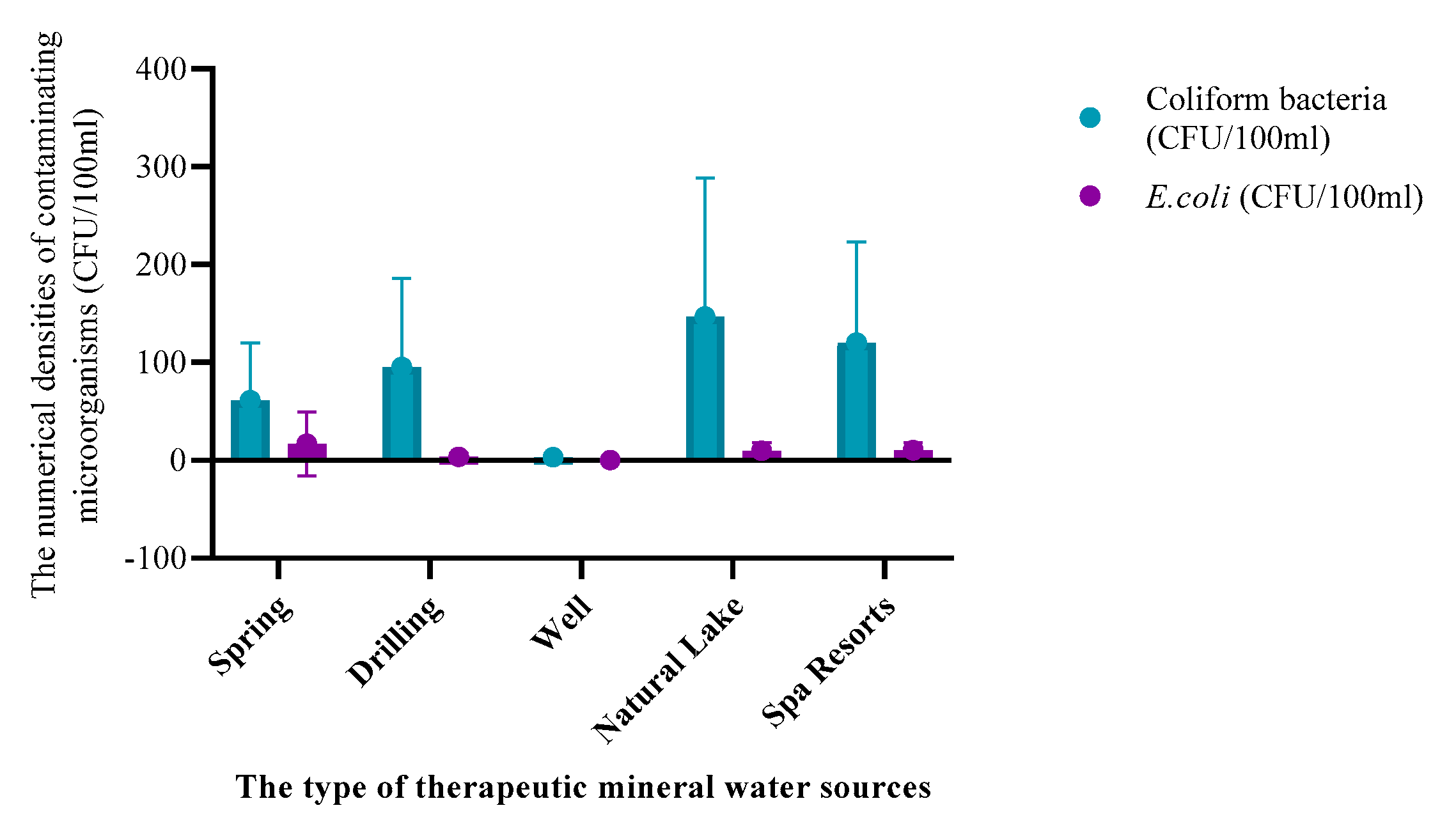

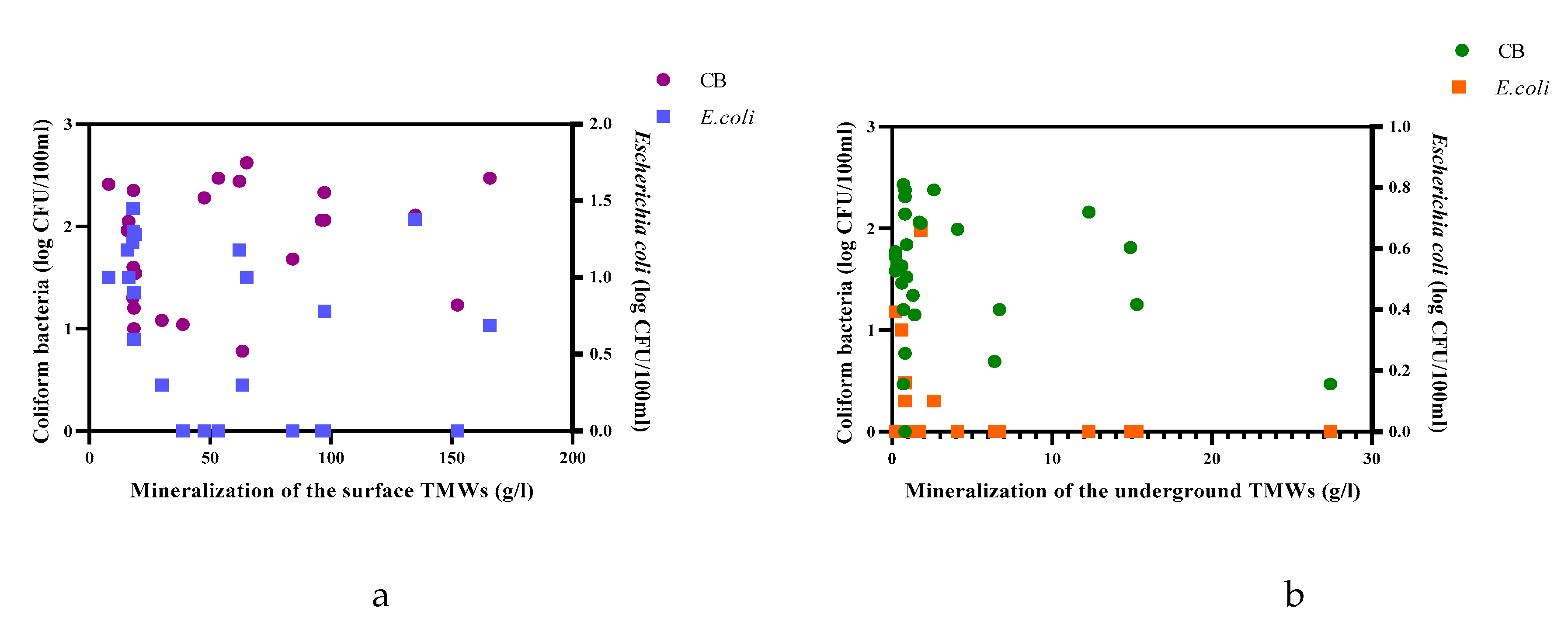

| Coliform bacteria (β-galactosidase+) (CFU/100ml) Escherichia coli (β-galactosidase+, indol+) (CFU/100ml) |

1/267/76.73 | 6/414/116.97 |

| Abs/96/17.56 | Abs/28/8.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).