Submitted:

17 October 2024

Posted:

18 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Population, Questions, and Collection of Data

2.2. Data Analysis Method

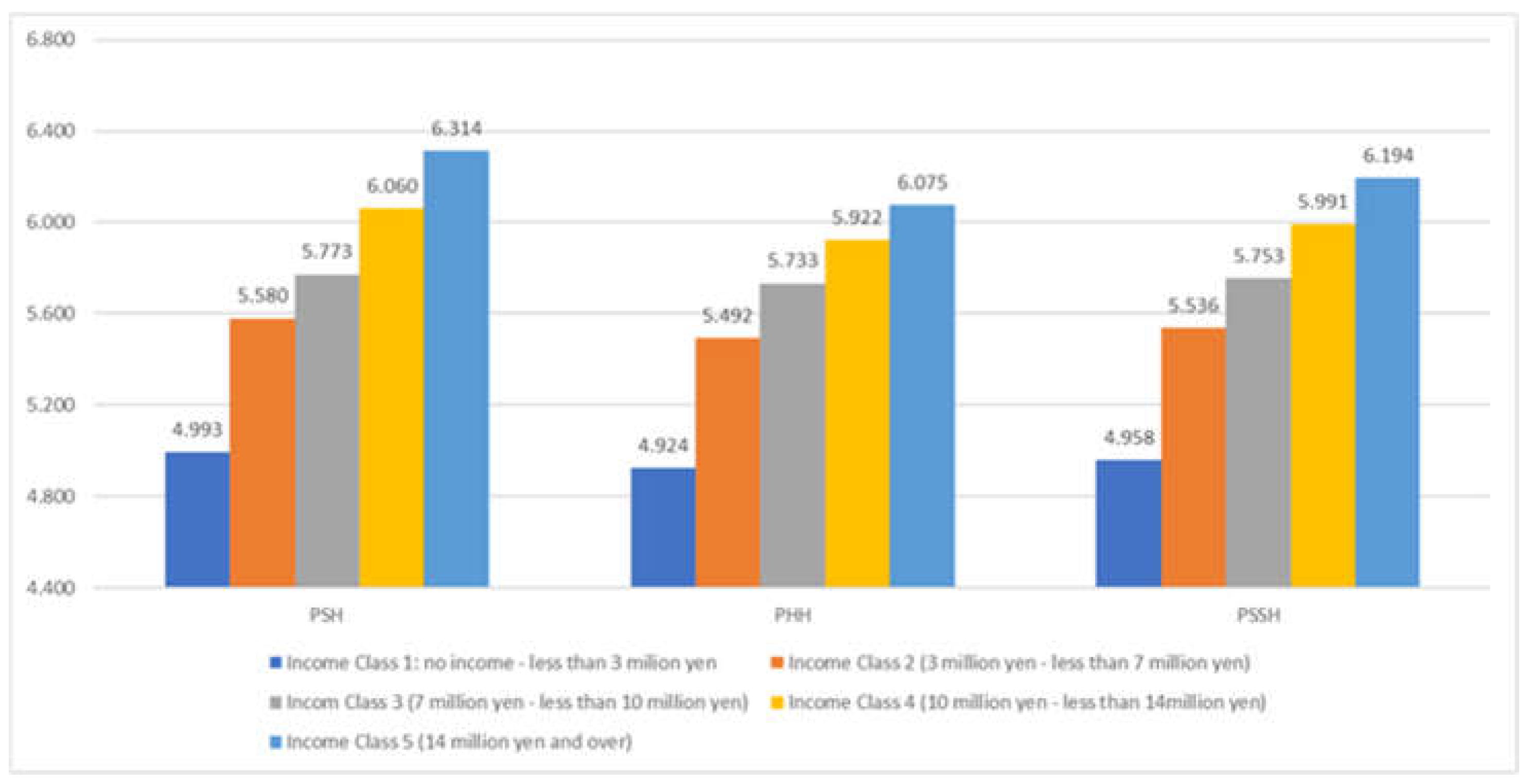

3. Results 1: Health Inequalities concerning Objective Personal Economic Situations

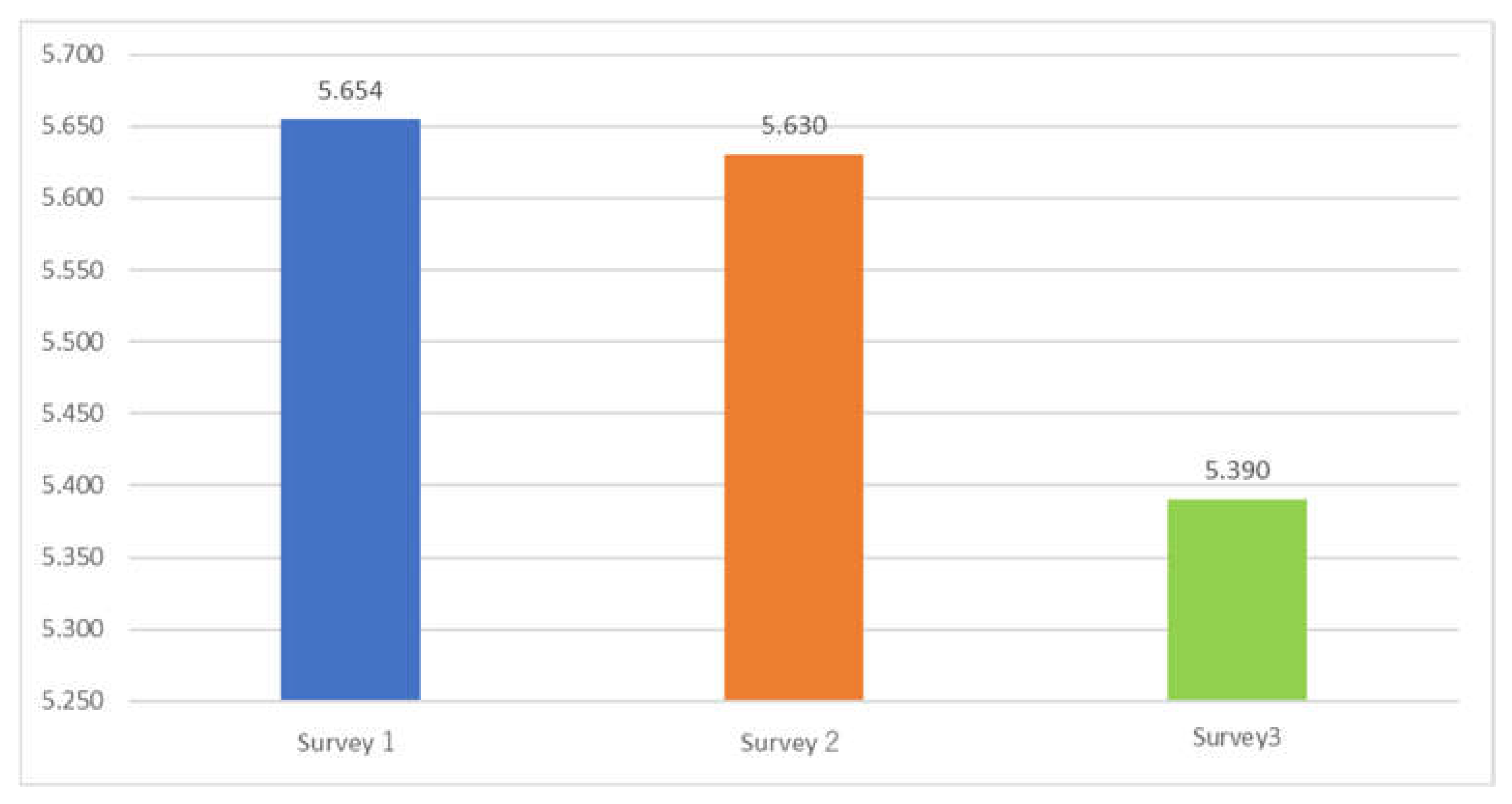

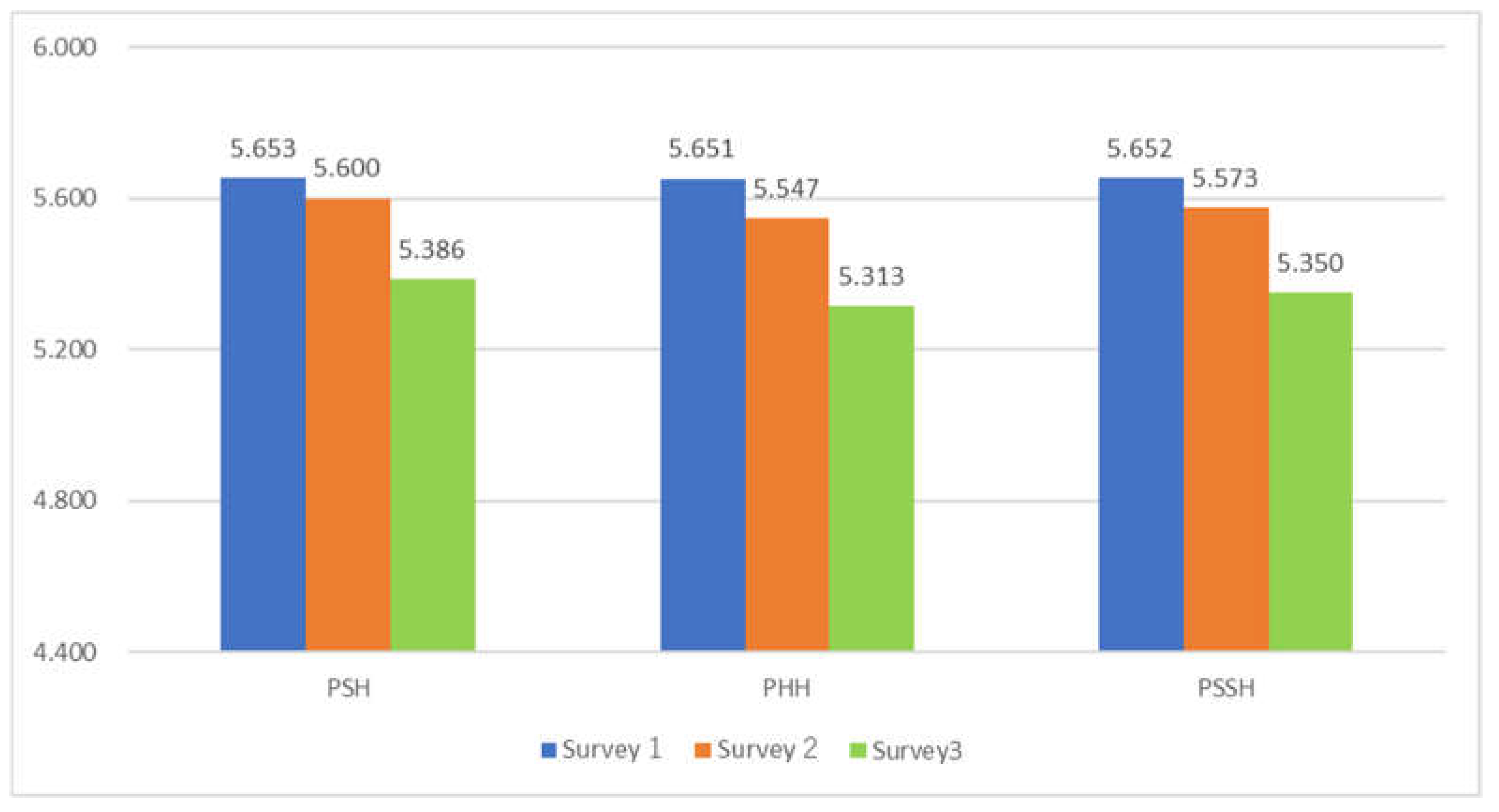

3.1. Decline in WB during the COVID-19

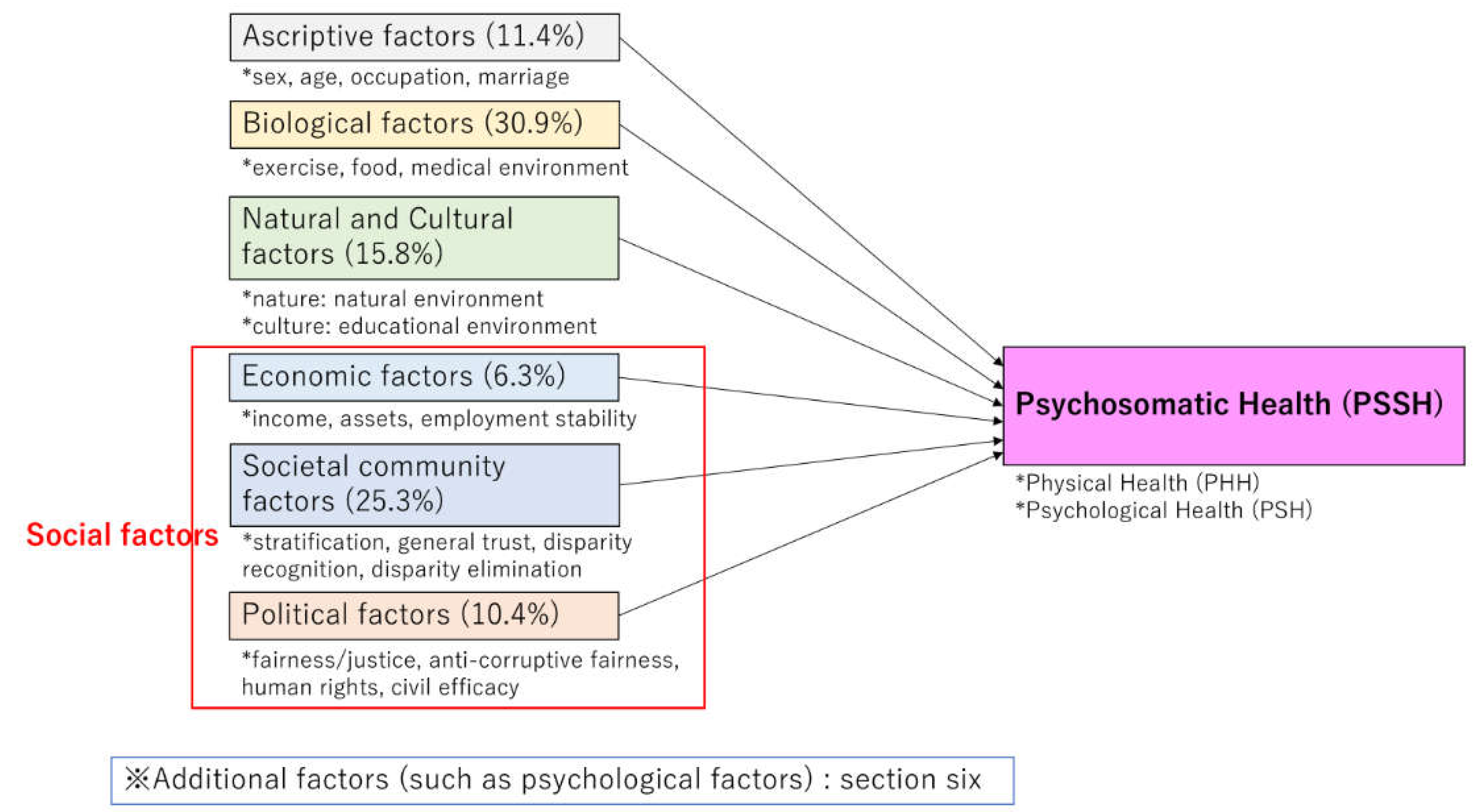

4. Results 2: Factors of Psychosomatic inequality

4.1. Correlations with Psychosomatic Inequalities

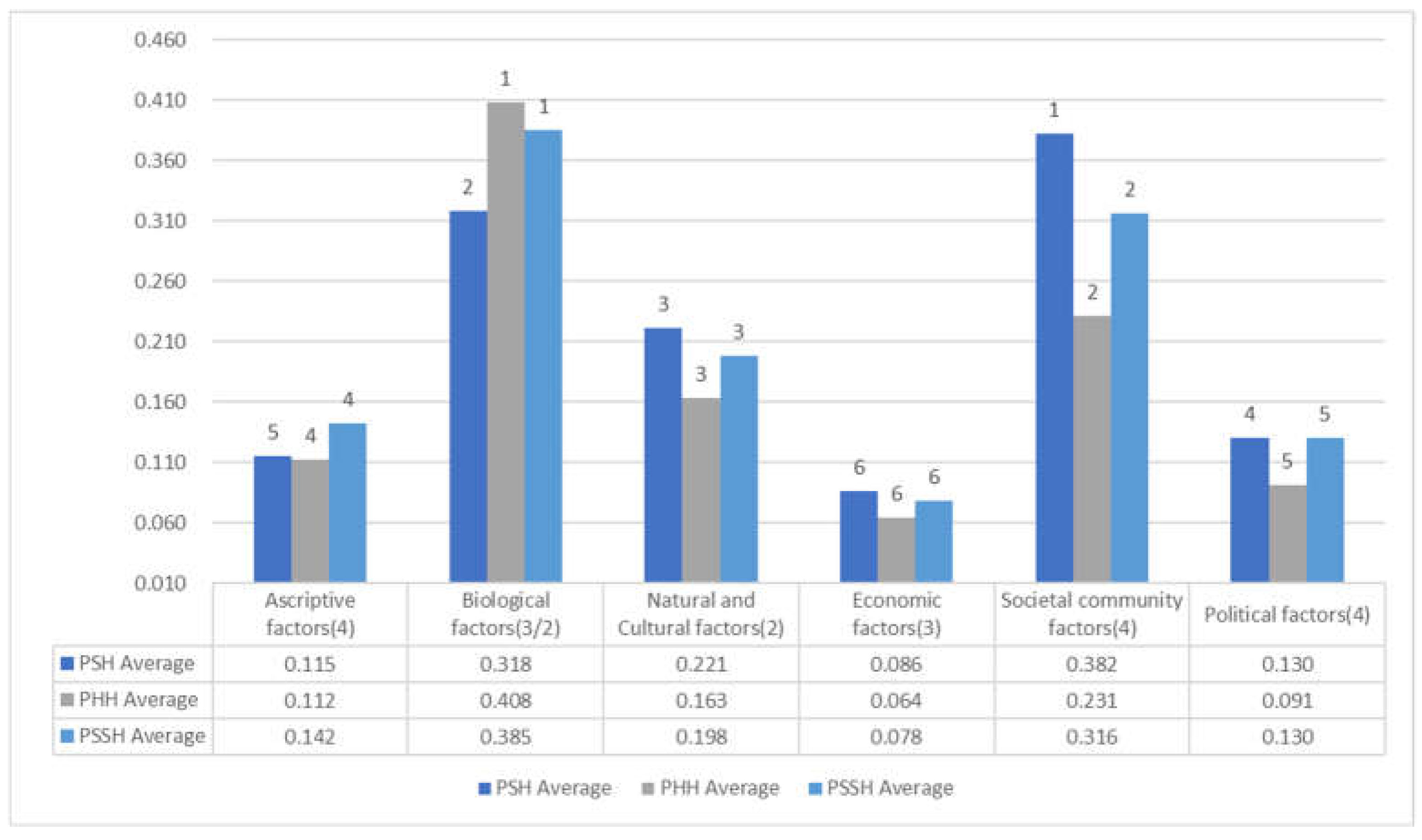

4.2. Multiple Regression Analyses on Psychosomatic Health

5. Examination of Psychosomatic Health

5.1. Liaison between Psychological and Physical Health

5.2. Relative Importance of Psychological/Physical Well-Being for Overall Well-Being

5.3. Calculation of Psychosomatic Health

6. Results 3: Psychosomatic Dynamics under COVID-19

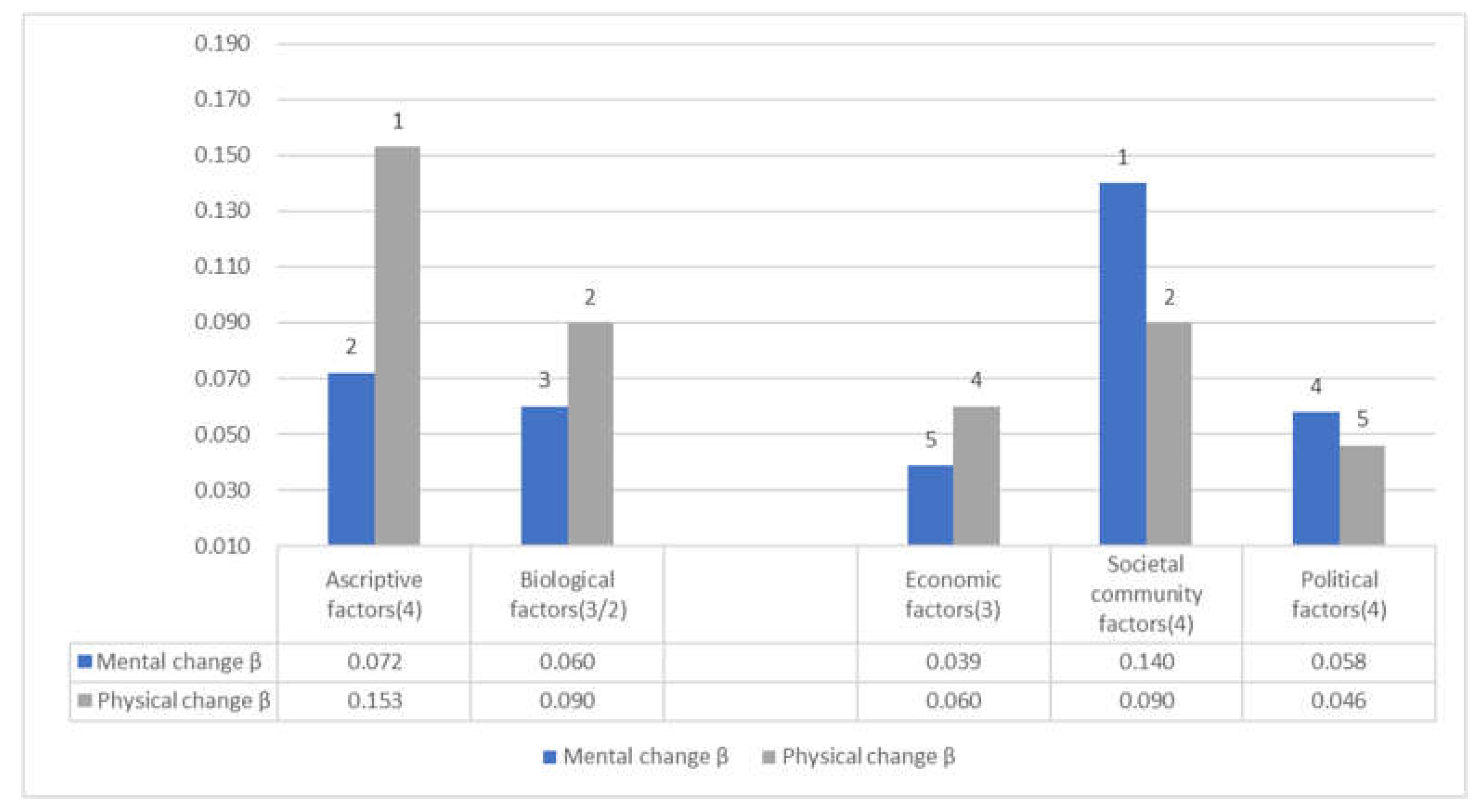

6.1. Factors Concerning Physical Changes under COVID-19: Appearance of Disparity Recognition and Fairness/ Justice

6.2. Pivotal Factors of Fair/Just Society and Distributive Justice in the COVID-19 Crisis

7. Discussions on Multi-Dimensional Dynamics of Psychosomatic Health Disparities

7.1. Multi-Dimensional Inequalities/Disparities and Policy Implications

7.2. Philosophical Implications: Multi-dimensional, Multi-layered, and Ethical Fairness and Justice Against Psychosomatic Health Disparity

7.3. Dynamism in the COVID-19 Crisis: Critical Significance and Causality of Fairness and Justice

8. Towards Communitarian Interventions

8.1. Summary of the Analysis: Multi-Dimensional Factors of the Psychosomatic Health Inequalities/Disparities

8.2. Multi-dimensional Communitarian Interventions: Societal-Community, Political, and Economic Measures

9. Limits of This Study

10. Conclusion: Multi-Dimensional Factors and Interventions for Psychosomatic Health

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Questions in the Three Surveys

Appendix A.1. Factors in Survey 1, Survey2 and Survey 3

| Category | Factor | Survey 1 | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | Answer |

| Ascriptive factors | sex | Please let us know your sex. | Please let us know your sex. | Please let us know your sex. | 1 (Male), 2 (Female) |

| age | Please let us know your age. | Please let us know your age. | Please let us know your age. | ||

| occupation | Please let us know your occupation. | Please let us know your occupation. | Please let us know your occupation. | See Appendix B,“Occupation” | |

| marriage | Are you married? | Are you married? | Are you married? | See Appendix B,“Marital status” | |

| Biological factors | exercise/foods | Do you think you are doing healthy exercise and eating? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

||

| exercise | Do you consider your exercise habits to be adequate? | ||||

| foods | Do you consider yourself to eat healthily? | ||||

| medical environment | Do you think the medical environment in your neighborhood, such as hospitals and pharmacies, is well-developed? | Do you think the medical environment in your neighborhood, such as hospitals and pharmacies, is well-developed? | |||

| Natural and Cultural factors | natural environment | How rich and blessed do you feel about the natural environment surrounding you? | Do you think the natural environment surrounding you is good? | Do you think the natural environment surrounding you is good? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

| educational environment | How well do you feel about your own educational or lifelong learning environment and the learning environment of the children around you? | Do you think your own educational or lifelong learning and the learning environment of children around you are fulfilling? | Do you think your own educational or lifelong learning and the learning environment of children around you are fulfilling? | ||

| Economic factors | income | Do you think your income is sufficient for you to make a living now that COVID-19 has struck? | Do you think your income is sufficient to live your life? | Do you think your income is sufficient to live your life? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

| assets | Do you think you have sufficient assets (financial, house, land, car, etc.) to live your life now that COVID-19 has occurred? | Do you consider your assets (financial, house, land, car, etc.) sufficient for your life? | Do you consider your assets (financial, house, land, car, etc.) sufficient for your life? | ||

| employment stability | Now that COVID-19 has occurred, do you consider your employment to be stable? | Do you feel that you have stability in your employment? | Do you feel that you have stability in your employment? | ||

| Societal community factors | stratification satisfaction | I think I am satisfied with my social status and stratification. | Are you satisfied with your social status and stratification? | Are you satisfied with your social status and stratification? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

| general trust | Do you find people generally trustworthy? | Do you find people generally trustworthy? | Do you find people generally trustworthy? | ||

| disparity recognition | How much disparity do you think exists in the society around you? | Do you think that there is a disparity in the society around you? | Do you think that there is a disparity in the society around you? | ||

| disparity elimination | Do you think that the society around you realizes the elimination of disparities (equal society) through social welfare and redistribution through taxes? | Do you think that the society around you realizes the elimination of disparity (equal society) through social welfare and redistribution through taxes? | Do you think that the society around you realizes the elimination of disparity (equal society) through social welfare and redistribution through taxes? | ||

| Political factors | fairness/justice | I believe that fairness and justice are achieved in our country’s politics in terms of decision-making, the disparity between rich and poor, and so on. | Do you think that Japanese politics achieve fairness and justice in terms of decision-making, the disparity between rich and poor, and so on? | Do you think that Japanese politics achieve fairness and justice in terms of decision-making, the disparity between rich and poor, and so on? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

| Anti-corruptive fairness | I think that my government is corruption-free and fair. | Do you think that the Japanese government is corruption-free and fair? | Do you think that the Japanese government is corruption-free and fair? | ||

| human rights | I believe that fundamental human rights are respected in my country. | Do you think that fundamental human rights are respected in Japan? | Do you think that fundamental human rights are respected in Japan? | ||

| civil efficacy | How much do you think you can change the society and politics around you in a desirable direction through your involvement? | Do you want to change the society and politics around you in a desirable direction through your involvement? | Do you want to change the society and politics around you in a desirable direction through your involvement? |

| Category | Factor | Survey 2 | Survey 3 | Answer |

| Fair society | fair society | All things to be considered, I think our current society is fair . | All things to be considered, I think our current society is fair . | 0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

| Just society | just society | All things to be considered, I think our current society is just. | All things to be considered, I think our current society is just. | |

| Fair/Just Society * | 1 | All things to be considered, I think our current society is fair . | ||

| 2 | All things to be considered, I think our current society is unfair . | |||

| 3 | All things to be considered, I think our current society is just. | |||

| 4 | All things to be considered, I think our current society is unjust. | |||

| Distributive Justice ** | disparity of justice | Do you think the disparity in Japan is in the right/ just state? | ||

| welfare justice | Do you think that welfare is rightly/ justly correcting the disparity in current society? | |||

| Contribution Optimism | contribution | Do you want to contribute to society? | Do you usually seek to contribute to others or the world around you in your activities? | 0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

| optimism | How optimistic would you say you are about your future? | I am optimistic about my future. |

Appendix A.2.Changes

Mental and Physical Changes (Survey1)

| Item | Survey 1 |

| Mental change | Mental changes, such as anxiety and restlessness. |

| Physical Change | Physical Change, such as condition and health situation. |

Appendix A.3. PERMA Profiler, SWLS, I COPPE, and Revised HEMA—R

SWLS

| Question | Answer in this survey | Original answer | |

| 1 | In most ways, my life is close to my ideal. | 1 = Strongly disagree, 10 = Strongly agree |

1 = strongly disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Slightly disagree, 4 = Neither agree nor disagree, 5 = Slightly agree, 6 = Agree, 7 = Strongly agree |

| 2 | The conditions of my life are excellent. | ||

| 3 | I am satisfied with my life. | ||

| 4 | So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life. | ||

| 5 | If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing. |

PERMA Profiler

| # | Label | Question | Answer in This Survey | Original Response Anchors |

| Block 1 | A1 | How much of the time do you feel you are making progress toward accomplishing your goals? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = never, 10 = always |

| E1 | How often do you become absorbed in what you are doing? | |||

| P1 | In general, how often do you feel joyful? | |||

| N1 | In general, how often do you feel anxious? | |||

| A2 | How often do you achieve the important goals you have set for yourself? | |||

| Block 2 | H1 | In general, how would you say your health is? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = terrible, 10 = excellent |

| Block 3 | M1 | In general, to what extent do you lead a purposeful and meaningful life? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

| R1 | To what extent do you receive help and support from others when you need it? | |||

| M2 | In general, to what extent do you feel that what you do in your life is valuable and worthwhile? | |||

| E2 | In general, to what extent do you feel excited and interested in things? | |||

| Lon | How lonely do you feel in your daily life? | |||

| Block 4 | H2 | How satisfied are you with your current physical health? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

| Block 5 | P2 | In general, how often do you feel positive? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = never, 10 = always |

| N2 | In general, how often do you feel angry? | |||

| A3 | How often are you able to handle your responsibilities? | |||

| N3 | In general, how often do you feel sad? | |||

| E3 | How often do you lose track of time while doing something you enjoy? | |||

| Block 6 | H3 | Compared to others of your same age and sex, how is your health? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = terrible, 10 = excellent |

| Block 7 | R2 | To what extent do you feel loved? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

| M3 | To what extent do you generally feel you have a sense of direction in your life? | |||

| R3 | How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? | |||

| P3 | In general, to what extent do you feel contented? | |||

| Block 8 | hap | Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are? | 1 = not at all, 10 = completely |

0 = not at all, 10 = completely |

I COPPE/ I CCOPPPE

| Label | Question | Answer in This Survey | Original Answer |

| OV_WB_PR | When it comes to the best possible life for you, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be 10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| OV_WB_PA | When it comes to the best possible life for you, on which number, did you stand five years ago? | ||

| OV_WB_FU | When it comes to the best possible life for you, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| IN_WB_PR | When it comes to relationships with important people in your life, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| IN_WB_FU | When it comes to relationships with important people in your life, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| CO_WB_PR | When it comes to the community where you live, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| CO_WB_FU | When it comes to the community where you live, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| OC_WB_PR | When it comes to your main occupation (employed, self-employed, volunteer, stay at home), on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be 10 = the best your life can be |

| OC_WB_FU | When it comes to your main occupation (employed, self-employed, volunteer, stay at home), on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| PH_WB_PR | When it comes to your physical health, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| PH_WB_FU | When it comes to your physical health, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| PS_WB_PR | When it comes to your emotional and psychological well-being, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| PS_WB_FU | When it comes to your emotional and psychological well-being, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| EC_WB_PR | When it comes to your economic situation, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | 0 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be |

| EC_WB_FU | When it comes to your economic situation, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| PO_WB_PA | When it comes to your political situation, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | |

| PO_WB_FU | When it comes to your political situation, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? | ||

| CU_WB_PA | When it comes to your cultural situation, on which number, do you stand now? | 1 = the worst your life can be10 = the best your life can be | |

| CU_WB_FU | When it comes to your cultural situation, on which number, do you think you will stand five years from now? |

Revised HEMA—R

| Question | Answer in This Survey | Original answer | |

| 1 | Seeking relaxation? | 1 = not at all, 10 = very much |

1 = not at all, 7 = very much |

| 2 | Seeking to develop a skill, learn, or gain insight into something? | ||

| 3 | Seeking to do what you believe in? | ||

| 4 | Seeking pleasure? | ||

| 5 | Seeking to pursue excellence or a personal ideal? | ||

| 6 | Seeking enjoyment? | ||

| 7 | Seeking to take it easy? | ||

| 8 | Seeking to use the best in yourself? | ||

| 9 | Seeking fun? | ||

| 10 | Seeking to contribute to others or the surrounding world? |

Appendix B. Respondents of the Three Surveys (after Data Screening)

| Survey 1 (%) | Survey 2 (%) | Survey 3 (%) | |

| Number of respondents | 4698 | 6855 | 2472 |

| Number of survey questions | 383 | 401 | 174 |

| Residence | |||

| 16 prefectures with big cities | 2783(59.2) | 1520(22.2) | 1207(48.8) |

| 32 prefectures without big cities | 1915(40.8) | 5335(77.8) | 1265(51.2) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 2283(48.6) | 4404(64.2) | 1626(65.8) |

| Female | 2415(51.4) | 2451(35.8) | 846(34.2) |

| Age | |||

| 10’s | 790(16.8) | 36(0.5) | 7(0.3) |

| 20’s | 759(16.2) | 460(6.7) | 125(5.1) |

| 30’s | 785(16.7) | 1038(15.1) | 346(14.0) |

| 40’s | 783(16.7) | 1726(25.2) | 610(24.7) |

| 50’s | 777(16.5) | 1740(25.4) | 626(25.3) |

| 60’s | 804(17.1) | 1236(18.0) | 480(19.4) |

| 70’s and more | 619(9.0) | 278(11.2) | |

| Marital status | |||

| married | 2172(46.2) | 4074(59.4) | 1418(57.4) |

| unmarried | 2301(49.0) | 2242(32.7) | 846(34.2) |

| separation | 225(4.8) | 539(7.9) * | 208(8.4) ** |

| Occupation | |||

| executive of a company or association | 44(0.9) | 123(1.8) | 53(2.1) |

| office worker, staff of an association | 1386(29.5) | 2085(30.4) | 734(29.7) |

| Part-time employee, contract employee, dispatched labor | 206(4.4) | 1196(17.4) | 433(17.5) |

| Part-time worker, part-time job, home-based workers without an employment contract | 585(12.5) | 17(0.2) | 7(0.3) |

| civil servants | 140(3.0) | 253(3.7) | 68(2.8) |

| Self-employed, family employee, freelance | 286(6.1) | 818(11.9) | 294(11.9) |

| faculty member | 123(1.8) | 39(1.6) | |

| student | 795(16.9) | 95(1.4) | 26(1.1) |

| homemaker | 700(14.9) | 766(11.2) | 292(11.8) |

| pensioner | 147(3.1) | 603(8.8) | 267(10.8) |

| none | 365(7.8) | 690(10.1) | 240(9.7) |

| others | 44(0.9) | 86(1.3) | 19(0.8) |

| Education | |||

| currently attending high school | 351(7.5) | 43(0.6) | 7(0.3) |

| currently attending vocational college, specialized training college | 75(1.6) | 84(1.2) | 26(1.1) |

| currently attending junior college, college | 48(1.0) | 47(0.7) | 8(0.3) |

| university/college preparatory school | 14(0.3) | 4(0.1) | |

| currently attending university | 366(7.8) | 88(1.3) | 35(1.4) |

| currently attending a Master’s or Doctoral course | 22(0.5) | 19(0.3) | 3(0.1) |

| junior high school | 70(1.5) | 175(2.6) | 50(2.0) |

| high school | 997(21.2) | 2153(31.4) | 664(26.9) |

| vocational college, specialized training college | 370(7.9) | 638(9.3) | 240(9.7) |

| junior college, college | 404(8.6) | 598(8.7) | 217(8.8) |

| university | 1778(37.8) | 2657(38.8) | 1081(43.7) |

| more than a Master’s degree | 203(4.3) | 349(5.1) | 141(5.7) |

Appendix C. Multiple Regression Analysis of the Basic Factors (Surveys 1 and Survey2)

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | |||||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | Survey1 | ||

| R | 0.815 | 0.835 | 0.708 | 0.727 | 0.795 | 0.818 | 0.203 | 0.210 | |

| R2 | 0.664 | 0.697 | 0.501 | 0.529 | 0.631 | 0.670 | 0.041 | 0.044 | |

| adjusted R2 | 0.663 | 0.696 | 0.500 | 0.528 | 0.630 | 0.669 | 0.040 | 0.042 | |

| β | β | ||||||||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.031** | 0.022 | 0.017* | 0.043** | ||||

| [13] | [14] | [5] | |||||||

| Age | -0.033* | 0.023** | -0.109** | -0.087** | -0.075** | -0.048** | 0.029* | 0.116** | |

| [11] | [13] | [3] | [4] | [9] | [8] | [7] | [1] | ||

| Occupation | 0.033** | 0.027** | 0.046** | 0.036** | 0.042** | 0.033** | |||

| [11] | [12] | [11] | [9] | [12] | [11] | ||||

| Marriage | 0.052** | 0.031** | 0.036** | 0.045** | 0.024* | -0.037* | |||

| [10] | [10] | [13] | [11] | [13] | [7] | ||||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | ー | 0.296** | ー | 0.411** | ー | 0.377** | ||

| ー | [1] | ー | [1] | ー | [1] | ||||

| Exercise | ー | 0.064** | ー | 0.040** | ー | -0.060** | |||

| ー | [9] | ー | [13] | ー | [2] | ||||

| Diets | 0.155** | ー | 0.198** | ー | 0.185** | ー | -0.090** | ||

| [2] | ー | [2] | ー | [2] | ー | [2] | |||

| Medical environment | 0.078** | 0.106** | 0.086** | 0.057** | 0.087** | 0.081** | |||

| [8] | [5] | [5] | [7] | [7] | [6] | ||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.114** | 0.088** | 0.083** | 0.108** | 0.103** | 0.097** | ||

| [4] | [6] | [6] | [2] | [3] | [5] | ||||

| Educational environment | 0.090** | 0.149** | 0.071** | 0.064** | 0.084** | 0.111** | |||

| [7] | [2] | [7] | [5] | [8] | [3] | ||||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.029* | |||||||

| [11] | |||||||||

| Assets | 0.061** | 0.046** | 0.044** | 0.057** | 0.055** | 0.064** | |||

| [9] | [7] | [12] | [7] | [10] | [7] | ||||

| Employment stability | 0.036** | 0.027* | 0.037** | -0.039* | -0.060** | ||||

| [9] | [11] | [10] | [6] | [3] | |||||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.322** | 0.137** | 0.242** | 0.095** | 0.294** | 0.121** | -0.087** | |

| [1] | [4] | [1] | [3] | [1] | [2] | [1] | |||

| General trust | 0.126** | 0.144** | 0.067** | 0.058** | 0.100** | 0.100** | -0.040* | ||

| [3] | [3] | [8] | [6] | [5] | [4] | [6] | |||

| Disparity recognition | 0.034** | 0.016* | 0.053** | 0.050** | |||||

| [14] | [15] | [4] | [4] | ||||||

| Disparity elimination | |||||||||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | -0.046** | |||||||

| [5] | |||||||||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | -0.076** | -0.048** | -0.045** | -0.063** | -0.042** | -0.058** | |||

| [14] | [15] | [14] | [14] | [16] | [3] | ||||

| Human rights | 0.103** | 0.089** | 0.101** | 0.027* | |||||

| [6] | [4] | [4] | [12] | ||||||

| Civil efficiency | 0.114** | 0.042** | 0.064** | 0.028* | 0.092** | 0.039** | |||

| [4] | [8] | [10] | [10] | [6] | [9] | ||||

Appendix D. Multiple Regression Analysis: Total Value of the Standardized Partial Regression Coefficients of Basic Variables for Each Category (Top 2 Items)

| PHH | PSH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | |||||||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | ||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | 0.155(14.1%) | 0.123(12.0%) | 0.139(13.1%) | 0.085(6.8%) | 0.058(5.3%) | 0.072(6.1%) | 0.120(9.8%) | 0.081(7.1%) | 0.101(8.5%) | 0.072(19.5%) | 0.153(34.9%) |

| [5] | [4] | [4] | [5] | [5] | [5] | [5] | [4] | [5] | [2] | [1] | |

| Biological factors(3/2) | 0.284(25.8%) | 0.468(45.5%) | 0.376(35.4%) | 0.233(18.7%) | 0.402(36.5%) | 0.318(27.0%) | 0.272(22.3%) | 0.458(40.4%) | 0.365(31.0%) | 0.060(16.3%) | 0.090(20.5%) |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | [2] | [1] | [2] | [2] | [1] | [1] | [3]1 | [2]1 | |

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | 0.154(14.0%) | 0.172(16.7%) | 0.163(15.3%) | 0.204(16.3%) | 0.237(21.5%) | 0.221(18.8%) | 0.187(15.3%) | 0.208(18.3%) | 0.198(16.8%) | ||

| [3] | [2] | [3] | [3] | [3] | [3] | [4] | [3] | [3] | |||

| Economic factors(3) | 0.044(4.0%) | 0.084(8.2%) | 0.064(6.0%) | 0.061(4.9%) | 0.082(7.4%) | 0.072(6.1%) | 0.055(4.5%) | 0.101(8.9%) | 0.078(6.6%) | 0.039(10.6%) | 0.060(13.7%) |

| [6]1 | [5] | [6] | [6]1 | [4] | [5] | [6]1 | [5] | [6] | [5]1 | [4]1 | |

| Societal community factors(4) | 0.309(28.1%) | 0.153(14.9%) | 0.231(21.7%) | 0.448(35.9%) | 0.281(25.5%) | 0.365(31.0%) | 0.394(32.3%) | 0.221(19.5%) | 0.308(26.1%) | 0.140(37.9%) | 0.090(20.5%) |

| [2] | [3] | [2] | [1] | [2] | [1] | [1] | [2] | [2] | [1] | [2] | |

| Political factors(4) | 0.153(13.9%) | 0.028(2.7%) | 0.091(8.5%) | 0.217(17.4%) | 0.042(3.8%) | 0.130(11.0%) | 0.193(15.8%) | 0.066(5.8%) | 0.130(11.0%) | 0.058(15.7%) | 0.046(10.5%) |

| [4] | [6]1 | [5] | [4] | [6]1 | [4] | [3] | [6] | [4] | [4]1 | [5]1 | |

Appendix E. Multiple Regression Analysis of All Factors, Including Additional Items

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | ||

| R | 0.882 | 0.747 | 0.851 | |

| R2 | 0.778 | 0.558 | 0.725 | |

| adjusted R2 | 0.778 | 0.557 | 0.724 | |

| β | ||||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.021** | 0.016* | |

| [12] | [17] | |||

| Age | -0.090** | -0.049** | ||

| [3] | [9] | |||

| Occupation | 0.021** | 0.037** | 0.029** | |

| [12] | [8] | [11] | ||

| Marriage | 0.031** | 0.022** | ||

| [10] | [15] | |||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | 0.181** | 0.355** | 0.287** |

| [2] | [1] | [1] | ||

| Medical environment | 0.070** | 0.036** | 0.052** | |

| [7] | [9] | [8] | ||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.036** | 0.078** | 0.056** |

| [9] | [4] | [6] | ||

| Educational environment | 0.063** | 0.045** | ||

| [8] | [10] | |||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.025** | ||

| [11] | ||||

| Assets | 0.033** | 0.025* | ||

| [11] | [13] | |||

| Employment stability | 0.018* | |||

| [16] | ||||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.095** | 0.068** | 0.081** |

| [5] | [6] | [5] | ||

| General trust | 0.082** | 0.029* | 0.055** | |

| [6] | [12] | [7] | ||

| Disparity recognition | ||||

| Disparity elimination | ||||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | |||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | -0.041** | -0.034** | ||

| [15] | [18] | |||

| Human rights | 0.022* | 0.025** | ||

| [13] | [13] | |||

| Civil efficiency | ||||

| HED | 0.120** | 0.074** | 0.097** | |

| [4] | [5] | [4] | ||

| EUD | 0.177** | 0.052** | 0.118** | |

| [3] | [7] | [3] | ||

| Fair/Just Society | 0.016** | |||

| [14] | ||||

| Contribution | -0.035** | -0.027** | ||

| [10] | [12] | |||

| Optimism | 0.268** | 0.210** | 0.251** | |

| [1] | [2] | [2] | ||

References

- Aisenstein, M. and Rappoport de Aisemberg, E. (eds.), Psychosomatics Today. (The International Psychoanalytical Association Psychoanalytic Ideas and Applications Series), New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Wolman, B.B., Psychosomatic Disorders, New York: Plenum Pub Corp, 1988.

- Ackerman, D.K. and DiMartini, A. F. (eds.), Psychosomatic Medicine (Pittsburgh Pocket Psychiatry), New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

- Turp, M., Psychosomatic Health: The Body and the Word, London: Red Globe Press, 2001.

- Spillane, A., Larkin, C., Cocroan, P., Matvienko-Sikar, K. and Riordan, F. , "Physical and Psychosomatic Health Outcomes in People Bereaved by Suicide Compared to People Bereaved by Other Modes of Death: A Systematic Review," BMC Public Health, vol. 17, no. 939, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Friberg, P., Hagquist, C. and Osika, W., "Self-perceived Psychosomatic Health in Swedish Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults: An Internet-Based Survey over Time," 2012. [Online].

- Paschouna, D. A., Damigosa, D., Skapinakisa, P. and Siamopoulosa,, "The Psychosomatic Health of the Spouses of Chronic Kidney Disease Patients," European Psychiatry, no. 30, 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Kobayashi, H. Ishido, J. Mizushima and H. Ishikawa, "Multi-Dimensional Dynamics of Psychological Health Disparities under the COVID-19 in Japan: Fairness/Justice in Socio-Economic and Ethico-Political Factors," International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, vol. 19, no. 24, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Kobayashi, "Chapter 7 Well-being and Fairness in the COVID-19 Crisis in Japan: Insights from Positive Political Psychology," in Social Fairness in a Post-Pandemic World: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, New York, Palgrave, forthcoming.

- Kobayashi, M, "Political Philosophies and Positive Political Psychology: Inter-Disciplinary Framework for the Common Good," Front. Psychol., no. 12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed., The Science of Well-Being: The Collected Works of Ed Diener, Springer Science + Business Media, 2009.

- Seligman, M.E.P., Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being, New York: Atria, 2012.

- Butler, J. and Kern, M.L., "The PERMA-Profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing," International Journal of Wellbeing, vol. 6, pp. 1-48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526, 2016. [CrossRef]

- Prilleltensky, I., Foodsz, S., Prilleltensky, O., Myers, N., Rubenstein, C., Jin, Y. and McMahon, A., "Assessing multi-dimensional well-being: development and validation of the I COPPE scale," Journal of Community Psychology, no. 43, p. 199–226, 2015.

- Wilkinson, R.G., The Impact of Inequality: How to Make Sick Societies Healthier, New York: The New Press, 2005.

- Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, S., The inner level: How more equal societies reduce stress, restore sanity and improve everyone’s well-being, London: Penguin Books, 2019.

- Wilkinson, R. and Pickett, S., The spirit level: Why greater equality makes societies stronger, London: Bloomsbury, 2011.

- Marmot, M.G., The Health Gap: the Challenge of an Unequal World, New York: Bloomsbury Pub Plc, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Marmot, M. and Wilkinson, R.G. (eds), Social Determinants of Health, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B.P. and Wilkinson, R.G., The Society and Population Health Reader: Income Inequality and Health, New York: New Press, 1999.

- Hunt, S.M., "Subjective Health Indicators and Health Promotion," Health Promotion International, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 23-34, 1988. [CrossRef]

- C. Monden, "Subjective Health and Subjective Well-Being," in Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research, vol. 20, Dordrecht, Springer, 2014.

- Peterson, C., A Primer in Positive Psychology, New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Huta, V., "Eudaimonic and Hedonic Orientations: Theoretical Considerations and Research Findings," in Handbook of Eudaimonic Well-being, New York, Springer, 2016.

- M. J. Sandel, Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do?, Farrar, Straus and Giroux-Macmillan, 2009.

- M. J. Sandel, Liberalism and the Limits of Justice, Cambridge University Press, 1982.

- Kobayashi, M., "Psychological Examination of Political Philosophies: Interrelationship Among Citizenship, Justice, and Well-Being in Japan. " Front. Psychol. , no. 12, 2022.

- Mizushima, J., "Yoroppa Shokoku no Koronaka eno Taiou to Shakaiteki Kousei (Response to the Corona Disaster and Social Justice in European Countries)," in Afuta Korona no Kousei Shakai (in Japanese) (Fair Society after the COVID-19), Tokyo: Akashi Shoten, 2022.

- P. and. O. Prilleltensky, Promoting Well-Being: Linking Personal, Organizational, and Community Change, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., 2006.

- Kobayashi, M., "“Tajigenteki na Tougouteki Kouseishakai Riron” (in Japanese) (Multidimensional Integrative Fair Society Theory)," in Kouseishakai no Bijon (The Vision for a Fair Society), Tokyo, Akashi Shoten, 2021.

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey1(N=4698) | Survey2(N=6855) | Survey3(N=2472) | Average | Survey1(N=4698) | Survey2(N=6855) | Survey3(N=2472) | Average | Survey1(N=4698) | Survey2(N=6855) | Survey3(N=2472) | Average | Survey1(N=4698) | Survey1(N=4698) | ||

| r | |||||||||||||||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.053** | 0.006 | 0.007 | △ | 0.021 | 0.023† | 0.039* | △ | 0.038** | 0.016 | 0.024 | △ | 0.059** | 0.026† |

| [19] | [18] | [17] | [19] | [16] | [19] | ||||||||||

| Age | 0.033* | 0.124** | 0.175** | 0.111 | -0.062** | 0.005 | 0.064** | △ | -0.018 | 0.065** | 0.124** | △ | 0.048** | 0.099** | |

| [20] | [18] | [14] | [18] | [19] | [16] | [18] | [16] | [19] | [10] | ||||||

| Occupation | 0.239** | 0.194** | 0.153** | 0.195 | 0.213** | 0.169** | 0.163** | 0.182 | 0.237** | 0.191** | 0.166** | 0.198 | -0.050** | -0.059** | |

| [16] | [17] | [15] | [16] | [16] | [15] | [14] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [14] | [15] | [18] | [17] | ||

| Marriage | 0.161** | 0.231** | 0.257** | 0.216 | 0.081** | 0.160** | 0.189** | 0.143 | 0.125** | 0.205** | 0.233** | 0.188 | -0.005 | 0.000 | |

| [17] | [16] | [13] | [15] | [17] | [17] | [13] | [16] | [17] | [16] | [13] | [16] | ||||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | (0.466**) | 0.705** | (0.585) | (0.458**) | 0.663** | (0.561) | (0.485**) | 0.723** | (0.604) | (-0.115**) | (-0.126**) | |||

| [1] | [4] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [2] | ||||||||||

| Exercise | 0.375** | 0.392** | 0.403** | -0.135** | -0.123** | ||||||||||

| [13] | [12] | [13] | [3] | [6] | |||||||||||

| Diets | 0.556** | 0.524** | 0.566** | -0.096** | -0.129** | ||||||||||

| [4] | [2] | [2] | [11] | [2] | |||||||||||

| Medical environment | 0.480** | 0.565** | 0.523 | 0.427** | 0.451** | 0.439 | 0.475** | 0.534** | 0.505 | -0.075** | -0.087** | ||||

| [10] | [8] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [9] | [9] | [9] | [8] | [13] | [12] | |||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.536** | 0.610** | 0.579** | 0.575 | 0.443** | 0.512** | 0.481** | 0.479 | 0.512** | 0.591** | 0.555** | 0.553 | -0.061** | -0.076** |

| [8] | [5] | [5] | [6] | [8] | [4] | [6] | [7] | [8] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [15] | [14] | ||

| Educational environment | 0.549** | 0.684** | 0.629** | 0.621 | 0.472** | 0.555** | 0.540** | 0.522 | 0.535** | 0.652** | 0.612** | 0.600 | -0.112** | -0.097** | |

| [5] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [5] | [2] | [1] | [3] | [5] | [2] | [2] | [3] | [9] | [11] | ||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.539** | 0.591** | 0.577** | 0.569 | 0.472** | 0.494** | 0.487** | 0.484 | 0.530** | 0.572** | 0.557** | 0.553 | -0.128** | -0.129** |

| [7] | [7] | [6] | [7] | [5] | [7] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [7] | [5] | [6] | [6] | [2] | ||

| Assets | 0.541** | 0.598** | 0.599** | 0.579 | 0.478** | 0.511** | 0.518** | 0.502 | 0.534** | 0.584** | 0.585** | 0.568 | -0.135** | -0.128** | |

| [6] | [6] | [4] | [5] | [3] | [5] | [3] | [4] | [6] | [6] | [3] | [5] | [3] | [5] | ||

| Employment stability | 0.462** | 0.553** | 0.538** | 0.518 | 0.399** | 0.469** | 0.465** | 0.444 | 0.451** | 0.538** | 0.525** | 0.505 | -0.126** | -0.133** | |

| [11] | [9] | [7] | [9] | [11] | [8] | [7] | [8] | [11] | [8] | [7] | [8] | [7] | [1] | ||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.692** | 0.638** | 0.647** | 0.659 | 0.580** | 0.525** | 0.529** | 0.545 | 0.666** | 0.612** | 0.616** | 0.631 | -0.151** | -0.120** |

| [1] | [4] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [2] | [2] | [1] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [7] | ||

| General trust | 0.564** | 0.640** | 0.602** | 0.602 | 0.464** | 0.506** | 0.495** | 0.488 | 0.538** | 0.602** | 0.574** | 0.571 | -0.103** | -0.116** | |

| [2] | [3] | [3] | [3] | [7] | [6] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [4] | [4] | [4] | [10] | [8] | ||

| Disparity recognition | 0.086** | 0.239** | 0.143** | 0.156 | 0.066** | 0.166** | 0.116** | 0.116 | 0.080** | 0.212** | 0.136** | 0.413 | 0.053** | 0.045** | |

| [18] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [18] | [16] | [15] | [17] | [18] | [15] | [15] | [17] | [17] | [18] | ||

| Disparity elimination | 0.310** | 0.429** | 0.440** | 0.393 | 0.275** | 0.380** | 0.400** | 0.352 | 0.307** | 0.427** | 0.441** | 0.392 | -0.095** | -0.065** | |

| [15] | [12] | [10] | [13] | [15] | [12] | [10] | [13] | [15] | [12] | [10] | [13] | [12] | [16] | ||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | 0.419** | 0.365** | 0.407** | 0.397 | 0.380** | 0.330** | 0.367** | 0.359 | 0.419** | 0.367** | 0.406** | 0.397 | -0.134** | -0.129** |

| [12] | [13] | [11] | [12] | [13] | [13] | [11] | [12] | [12] | [13] | [11] | [12] | [5] | [2] | ||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | 0.338** | 0.314** | 0.346** | 0.333 | 0.315** | 0.296** | 0.330** | 0.314 | 0.343** | 0.322** | 0.355** | 0.340 | -0.141** | -0.115** | |

| [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [2] | [9] | ||

| Human rights | 0.560** | 0.483** | 0.502** | 0.515 | 0.473** | 0.417** | 0.422** | 0.437 | 0.541** | 0.475** | 0.484** | 0.500 | -0.074** | -0.070** | |

| [3] | [11] | [8] | [10] | [4] | [11] | [8] | [10] | [3] | [11] | [8] | [10] | [14] | [15] | ||

| Civil efficiency | 0.493** | 0.551** | 0.481** | 0.508 | 0.413** | 0.458** | 0.401** | 0.424 | 0.475** | 0.531** | 0.462** | 0.489 | -0.122** | -0.082** | |

| [9] | [10] | [9] | [11] | [10] | [9] | [9] | [11] | [10] | [10] | [9] | [11] | [8] | [13] | ||

| PSH | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.809** | 0.784** | 0.816** | 0.803 | 0.947** | 0.937** | 0.950** | 0.945 | -0.157** | -0.145** | ||

| PHH | 0.809** | 0.784** | 0.816** | 0.803 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.955** | 0.951** | 0.955** | 0.954 | -0.154** | -0.189** | ||

| PSSH | 0.947** | 0.937** | 0.950** | 0.945 | 0.955** | 0.951** | 0.955** | 0.954 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | -0.164** | -0.177** | ||

| Mental change | -0.157** | -0.154** | -0.164** | 1.000 | 0.457** | ||||||||||

| Physical change | -0.145** | -0.189** | -0.177** | 0.457** | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| Fair society | 0.428** | 0.463** | 0.446 | 0.384** | 0.404** | 0.394 | 0.428** | 0.455** | 0.442 | ||||||

| Just society | 0.426** | 0.481** | 0.454 | 0.370** | 0.421** | 0.396 | 0.419** | 0.472** | 0.446 | ||||||

| Fair/Just society | 0.243** | 0.221** | 0.245** | ||||||||||||

| Distributive justice | 0.472** | 0.420** | 0.471** | ||||||||||||

| Contribution | 0.505** | 0.588** | 0.576** | 0.556 | 0.419** | 0.452** | 0.476** | 0.449 | 0.484** | 0.546** | 0.551** | 0.527 | -0.046* | -0.073** | |

| Optimism | 0.624** | 0.752** | 0.716** | 0.697 | 0.514** | 0.611** | 0.605** | 0.577 | 0.595** | 0.718** | 0.692** | 0.668 | -0.145** | -0.132** | |

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Average | Survey1 | ||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | 0.122(4.8%) | 0.183(6.2%) | 0.195(8.6%) | 0.167(6.0%) | 0.119(5.4%) | 0.176(7.0%) | 0.228(11.4%) | 0.174(7.2%) | 0.133(5.4%) | 0.154(5.4%) | 0.174(8.0%) | 0.154(5.7%) | 0.052(8.5%) | 0.061(10.6%) |

| [6] | [6] | [5] | [6] | [6] | [6] | [5] | [6] | [6] | [6] | [5] | [6] | [6] | [6] | |

| Biological factors(3/2) | 0.469(18.7%) | 0.635(21.4%) | 0.552(20.0%) | 0.450(20.3%) | 0.557(22.0%) | 0.504(20.9%) | 0.482(19.4%) | 0.629(22.0%) | 0.555(20.6%) | 0.102(16.5%) | 0.113(19.6%) | |||

| [3] | [2] | [3] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [1] | [2] | [4] | [2] | ||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | 0.543(21.6%) | 0.647(21.9%) | 0.604(26.7%) | 0.598(21.6%) | 0.458(20.6%) | 0.534(21.1%) | 0.511(25.6%) | 0.501(20.7%) | 0.524(21.1%) | 0.622(21.8%) | 0.584(26.7%) | 0.576(21.4%) | 0.117(18.9%) | 0.087(15.0%) |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [2] | [1] | [2] | [1] | [2] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [4] | |

| Economic factors(3) | 0.514(20.5%) | 0.581(19.6%) | 0.571(25.3%) | 0.555(20.1%) | 0.450(20.3%) | 0.491(19.4%) | 0.490(24.6%) | 0.477(19.8%) | 0.505(20.3%) | 0.565(19.8%) | 0.556(25.5%) | 0.542(20.1%) | 0.130(20.9%) | 0.130(22.6%) |

| [2] | [3] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [3] | [2] | [3] | [2] | [3] | [2] | [3] | [1] | [1] | |

| Societal community factors(4) | 0.413(16.4%) | 0.487(16.4%) | 0.458(16.4%) | 0.453(16.4%) | 0.346(15.6%) | 0.394(15.6%) | 0.385(19.3%) | 0.375(15.5%) | 0.398(16.0%) | 0.463(16.2%) | 0.442(20.2%) | 0.434(16.1%) | 0.101(16.2%) | 0.087(15.0%) |

| [5] | [4] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [3] | [5] | [5] | [4] | [3] | [4] | [5] | [4] | |

| Political factors(4) | 0.453(18.0%) | 0.428(14.5%) | 0.434(19.2%) | 0.438(15.9%) | 0.395(17.8%) | 0.375(14.8%) | 0.380(19.1%) | 0.384(15.9%) | 0.445(17.9%) | 0.424(14.8%) | 0.427(19.6%) | 0.432(16.0%) | 0.118(19.0%) | 0.099(17.2%) |

| [4] | [5] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [4] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [5] | [2] | [3] | |

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey1 | ||

| R | 0.815 | 0.835 | 0.708 | 0.727 | 0.795 | 0.818 | 0.203 | 0.210 |

| R2 | 0.664 | 0.697 | 0.501 | 0.529 | 0.631 | 0.670 | 0.041 | 0.044 |

| adjusted R2 | 0.663 | 0.696 | 0.500 | 0.528 | 0.630 | 0.669 | 0.040 | 0.042 |

| 1 | Stratification | Exercise/Foods | Stratification | Exercise/Foods | Stratification | Exercise/Foods | Stratification | Age |

| (0.322**) | (0.296**) | (0.242**) | (0.411**) | (0.294**) | (0.377**) | (-0.087**) | (0.116**) | |

| 2 | Foods | Educational environment | Foods | Natural environment | Foods | Stratification | Exercise | Foods |

| (0.155**) | (0.149**) | (0.198**) | (0.108**) | (0.185**) | (0.121**) | (-0.060**) | (-0.090**) | |

| 3 | General trust | General trust | Age | Stratification | Natural environment | Educational environment | Anti-corruptive fairness | Employment stability |

| (0.126**) | (0.144**) | (-0.109**) | (0.095**) | (0.103**) | (0.111**) | (-0.058**) | (-0.060**) | |

| 4 | Natural environment | Stratification | Human rights | Age | Human rights | General trust | Disparity recognition | Disparity recognition |

| (0.114**) | (0.137**) | (0.089**) | (-0.087**) | (0.101**) | (0.100**) | (0.053**) | (0.050**) | |

| 5 | Civil efficacy | Medical environment | Medical environment | Educational environment | General trust | Natural environment | Sex | Fairness/Justice |

| (0.114**) | (0.106**) | (0.086**) | (0.064**) | (0.100**) | (0.097**) | (0.043*) | (-0.046**) | |

| 6 | Human rights | Natural environment | Natural environment | General trust | Civil efficacy | Medical environment | Employment stability | General trust |

| (0.103**) | (0.088**) | (0.083**) | (0.058**) | (0.092**) | (0.081**) | (-0.039*) | (-0.040*) | |

| 7 | Educational environment | Assets | Educational environment | Medical environment | Medical environment | Assets | Age | Marital status |

| (0.090**) | (0.046**) | (0.071**) | (0.057**) | (0.087**) | (0.064**) | (0.029*) | (-0.037*) | |

| 8 | Medical environment | Civil efficacy | General trust | Assets | Educational environment | Age | ||

| (0.078**) | (0.042**) | (0.067**) | (0.057**) | (0.084**) | (-0.048**) | |||

| 9 | Assets | Employment stability | Exercise | Occupation | Age | Civil efficacy | ||

| (0.061**) | (0.036**) | (0.064**) | (0.036**) | (-0.075**) | (0.039**) | |||

| 10 | Marital status | Marital status | Civil efficacy | Civil efficacy | Assets | Employment stability | ||

| (0.052**) | (0.031**) | (0.064**) | (0.028*) | (0.055**) | (0.037**) | |||

| PSH | PHH | PSSH | Mental change | Physical change | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | Survey2 | Average | Survey1 | ||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | 0.149(11.4%) | 0.081(6.8%) | 0.115(9.2%) | 0.101(9.1%) | 0.123(12.0%) | 0.112(10.5%) | 0.162(12.4%) | 0.122(10.2%) | 0.142(11.4%) | 0.072(19.5%) | 0.153(34.9%) |

| [5]4 | [5]3 | [5] | [5]3 | [4]2 | [4] | [5]3 | [4]4 | [4] | [2]2 | [1]2 | |

| Biological factors(3/2) | 0.233(17.8%) | 0.402(33.8%) | 0.318(25.4%) | 0.348(31.4%) | 0.468(45.5%) | 0.408(38.2%) | 0.312(23.9%) | 0.458(38.4%) | 0.385(30.9%) | 0.060(16.3%) | 0.090(20.5%) |

| [2]2 | [1]2 | [2] | [1]3 | [1]2 | [1] | [2]3 | [1]2 | [1] | [3]1 | [2]1 | |

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | 0.204(15.5%) | 0.237(19.9%) | 0.221(17.6%) | 0.154(13.9%) | 0.172(16.7%) | 0.163(15.3%) | 0.187(14.4%) | 0.208(17.4%) | 0.198(15.8%) | ||

| [3]2 | [3]2 | [3] | [3]2 | [2]2 | [3] | [4]2 | [3]2 | [3] | |||

| Economic factors(3) | 0.061(4.6%) | 0.111(9.3%) | 0.086(6.9%) | 0.044(4.0%) | 0.084(8.2%) | 0.064(6.0%) | 0.055(4.2%) | 0.101(8.5%) | 0.078(6.3%) | 0.039(10.6%) | 0.060(13.7%) |

| [6]1 | [4]3 | [6] | [6]1 | [5]2 | [6] | [6]1 | [5]2 | [6] | [5]1 | [4]1 | |

| Societal community factors(4) | 0.448(34.1%) | 0.315(26.5%) | 0.382(30.5%) | 0.309(27.9%) | 0.153(14.9%) | 0.231(21.6%) | 0.394(30.2%) | 0.237(19.9%) | 0.316(25.3%) | 0.140(37.9%) | 0.090(20.5%) |

| [1]2 | [2]3 | [1] | [2]2 | [3]2 | [2] | [1]2 | [2]3 | [2] | [1]2 | [2]2 | |

| Political factors(4) | 0.217(16.5%) | 0.042(3.5%) | 0.130(10.4%) | 0.153(13.8%) | 0.028(2.7%) | 0.091(8.5%) | 0.193(14.8%) | 0.066(5.5%) | 0.130(10.4%) | 0.058(15.7%) | 0.046(10.5%) |

| [4]2 | [6]1 | [4] | [4]2 | [6]1 | [5] | [3]2 | [6]2 | [5] | [4]1 | [5]1 | |

| IOv | IPs | IPh | IN | IC | IO | IE | IPo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOv | 1.000 | 0.817** | 0.717** | 0.814** | 0.709** | 0.790** | 0.796** | 0.664** | ||||||||

| IPs | 0.817** | 1.000 | 0.807** | 0.776** | 0.701** | 0.771** | 0.777** | 0.676** | ||||||||

| IPh | 0.717** | 0.807** | 1.000 | 0.693** | 0.660** | 0.716** | 0.723** | 0.638** | ||||||||

| INT | 0.814** | 0.776** | 0.693** | 1.000 | 0.749** | 0.765** | 0.732** | 0.636** | ||||||||

| IC | 0.709** | 0.701** | 0.660** | 0.749** | 1.000 | 0.752** | 0.702** | 0.687** | ||||||||

| IO | 0.790** | 0.771** | 0.716** | 0.765** | 0.752** | 1.000 | 0.774** | 0.706** | ||||||||

| IE | 0.796** | 0.777** | 0.723** | 0.732** | 0.702** | 0.774** | 1.000 | 0.735** | ||||||||

| IPo | 0.664** | 0.676** | 0.638** | 0.636** | 0.687** | 0.706** | 0.735** | 1.000 | ||||||||

| IOv | IPs | IPh | IN | IC | IO | IE | IPo | ICul | ||||||||

| IOv | 1.000 | 0.828** | 0.723** | 0.824** | 0.720** | 0.778** | 0.794** | 0.645** | 0.694** | |||||||

| IPs | 0.828** | 1.000 | 0.796** | 0.778** | 0.708** | 0.768** | 0.770** | 0.657** | 0.725** | |||||||

| IPh | 0.723** | 0.796** | 1.000 | 0.680** | 0.657** | 0.709** | 0.694** | 0.632** | 0.672** | |||||||

| INT | 0.824** | 0.778** | 0.680** | 1.000 | 0.752** | 0.749** | 0.718** | 0.634** | 0.697** | |||||||

| IC | 0.720** | 0.708** | 0.657** | 0.752** | 1.000 | 0.752** | 0.689** | 0.672** | 0.718** | |||||||

| IO | 0.778** | 0.768** | 0.709** | 0.749** | 0.752** | 1.000 | 0.765** | 0.661** | 0.700** | |||||||

| IE | 0.794** | 0.770** | 0.694** | 0.718** | 0.689** | 0.765** | 1.000 | 0.718** | 0.738** | |||||||

| IPo | 0.645** | 0.657** | 0.632** | 0.634** | 0.672** | 0.661** | 0.718** | 1.000 | 0.808** | |||||||

| ICul | 0.694** | 0.725** | 0.672** | 0.697** | 0.718** | 0.700** | 0.738** | 0.808** | 1.000 | |||||||

| IOv | IPs | IPh | IN | IC | IO | IE | IPo | ICul | ||||||||

| IOv | 1.000 | 0.815** | 0.738** | 0.831** | 0.712** | 0.803** | 0.829** | 0.688** | 0.704** | |||||||

| IPs | 0.815** | 1.000 | 0.810** | 0.785** | 0.708** | 0.773** | 0.767** | 0.697** | 0.738** | |||||||

| IPh | 0.738** | 0.810** | 1.000 | 0.698** | 0.672** | 0.740** | 0.719** | 0.664** | 0.700** | |||||||

| INT | 0.831** | 0.785** | 0.698** | 1.000 | 0.735** | 0.763** | 0.738** | 0.669** | 0.709** | |||||||

| IC | 0.712** | 0.708** | 0.672** | 0.735** | 1.000 | 0.758** | 0.670** | 0.697** | 0.736** | |||||||

| IO | 0.803** | 0.773** | 0.740** | 0.763** | 0.758** | 1.000 | 0.788** | 0.705** | 0.727** | |||||||

| IE | 0.829** | 0.767** | 0.719** | 0.738** | 0.670** | 0.788** | 1.000 | 0.730** | 0.728** | |||||||

| IPo | 0.688** | 0.697** | 0.664** | 0.669** | 0.697** | 0.705** | 0.730** | 1.000 | 0.820** | |||||||

| ICul | 0.704** | 0.738** | 0.700** | 0.709** | 0.736** | 0.727** | 0.728** | 0.820** | 1.000 | |||||||

| IPs | IPh | PSSH−PHH | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | ||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.047** | 0.010 | 0.005 | 0.029* | 0.029* | 0.047* | 0.046** | -0.027* | -0.054** |

| [19] | [20] | [18] | [16] | [10] | [14] | [12] | ||||

| Age | 0.022 | 0.111** | 0.150** | -0.084** | -0.002 | 0.042* | 0.155** | 0.167** | 0.171** | |

| [18] | [14] | [17] | [17] | [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||

| Occupation | 0.210** | 0.170** | 0.130** | 0.207** | 0.160** | 0.160** | 0.011 | 0.006 | -0.028 | |

| [16] | [17] | [15] | [16] | [17] | [14] | |||||

| Marriage | 0.138** | 0.212** | 0.225** | 0.073** | 0.161** | 0.185** | 0.112** | 0.073** | 0.095** | |

| [17] | [15] | [13] | [18] | [16] | [13] | [2] | [6] | [9] | ||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | 0.660** | 0.656** | -0.059** | ||||||

| [1] | [1] | [8] | ||||||||

| Exercise | 0.339** | 0.378** | -0.080** | |||||||

| [13] | [12] | [6] | ||||||||

| Diets | 0.519** | 0.507** | -0.022 | |||||||

| [4] | [2] | |||||||||

| Medical environment | 0.458** | 0.529** | 0.431** | 0.456** | 0.023 | 0.082** | ||||

| [9] | [8] | [9] | [10] | [4] | ||||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.506** | 0.568** | 0.533** | 0.457** | 0.514** | 0.472** | 0.094** | 0.048** | 0.118** |

| [5] | [5] | [5] | [8] | [5] | [6] | [3] | [11] | [4] | ||

| Educational environment | 0.496** | 0.628** | 0.552** | 0.479** | 0.565** | 0.533** | 0.054** | 0.084** | 0.100** | |

| [7] | [2] | [2] | [4] | [2] | [1] | [9] | [3] | [6] | ||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.493** | 0.551** | 0.511** | 0.468** | 0.498** | 0.476** | 0.039** | 0.049** | 0.106** |

| [8] | [7] | [6] | [6] | [7] | [5] | [12] | [10] | [5] | ||

| Assets | 0.499** | 0.559** | 0.534** | 0.473** | 0.515** | 0.507** | 0.033* | 0.032** | 0.088** | |

| [6] | [6] | [4] | [5] | [4] | [3] | [13] | [13] | [10] | ||

| Employment stability | 0.427** | 0.508** | 0.474** | 0.398** | 0.479** | 0.446** | 0.042** | 0.034** | 0.080** | |

| [11] | [9] | [7] | [11] | [8] | [7] | [11] | [12] | [11] | ||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.628** | 0.590** | 0.578** | 0.577** | 0.530** | 0.514** | 0.093** | 0.065** | 0.147** |

| [1] | [4] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [2] | [4] | [7] | [2] | ||

| General trust | 0.521** | 0.596** | 0.542** | 0.463** | 0.512** | 0.482** | 0.091** | 0.099** | 0.132** | |

| [3] | [3] | [3] | [7] | [6] | [4] | [5] | [2] | [3] | ||

| Disparity recognition | 0.069** | 0.205** | 0.128** | 0.073** | 0.164** | 0.109** | 0.021 | 0.073** | 0.034† | |

| [18] | [16] | [16] | [19] | [15] | [15] | [5] | [14] | |||

| Disparity elimination | 0.282** | 0.394** | 0.386** | 0.277** | 0.385** | 0.384** | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.033† | |

| [15] | [12] | [10] | [15] | [12] | [10] | [15] | ||||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | 0.380** | 0.345** | 0.362** | 0.377** | 0.344** | 0.358** | 0.007 | -0.008 | 0.035† |

| [12] | [13] | [11] | [13] | [13] | [11] | [13] | ||||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | 0.310** | 0.293** | 0.310** | 0.315** | 0.310** | 0.323** | -0.006 | -0.027* | -0.001 | |

| [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | ||||

| Human rights | 0.524** | 0.452** | 0.460** | 0.481** | 0.427** | 0.417** | 0.070** | 0.019 | 0.095** | |

| [2] | [11] | [8] | [3] | [11] | [8] | [7] | [8] | |||

| Civil efficiency | 0.443** | 0.498** | 0.414** | 0.418** | 0.468** | 0.391** | 0.066** | 0.049** | 0.096** | |

| [10] | [10] | [9] | [10] | [9] | [9] | [8] | [9] | [7] | ||

| EUD | 0.524** | 0.656** | 0.580** | 0.501** | 0.582** | 0.528** | 0.092** | 0.145** | 0.168** | |

| HED | 0.321** | 0.647** | 0.588** | 0.305** | 0.570** | 0.516** | 0.064** | 0.122** | 0.173** | |

| Fair/Just society | 0.242** | 0.228** | -0.009 | |||||||

| Distributive justice | 0.436** | 0.428** | -0.001 | |||||||

| Contribution | 0.444** | 0.573** | 0.497** | 0.419** | 0.507** | 0.461** | 0.075** | 0.124** | 0.122** | |

| Optimism | 0.572** | 0.720** | 0.671** | 0.499** | 0.621** | 0.606** | 0.100** | 0.090** | 0.129** | |

| IOv | |||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | |

| R | 0.822 | 0.835 | 0.825 |

| R2 | 0.676 | 0.697 | 0.681 |

| adjusted R2 | 0.676 | 0.697 | 0.681 |

| β(standardized partial regression coefficient) | |||

| IPs | 0.682** | 0.689** | 0.632** |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | |

| IPh | 0.167** | 0.174** | 0.225** |

| [2] | [2] | [2] | |

| IOv | |||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | |

| R | 0.887 | 0.895 | 0.904 |

| R2 | 0.787 | 0.802 | 0.818 |

| adjusted R2 | 0.787 | 0.801 | 0.817 |

| β (standardized partial regression coefficient) | |||

| IPs | 0.269** | 0.275** | 0.193** |

| [2] | [2] | [3] | |

| IPh | -0.001 | 0.041** | 0.023* |

| [5] | [7] | ||

| IN | 0.307** | 0.335** | 0.323** |

| [1] | [1] | [2] | |

| IC | 0.003 | 0.026** | 0.026† |

| [7] | [6] | ||

| IO | 0.168** | 0.113** | 0.144** |

| [4] | [4] | [4] | |

| IE | 0.235** | 0.243** | 0.324** |

| [3] | [3] | [1] | |

| IPo | -0.004 | -0.017† | 0.001 |

| [8] | |||

| ICul | -0.029** | -0.050** | |

| [6] | [5] | ||

| IOv | |||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | |

| R | 0.883 | 0.892 | 0.903 |

| R2 | 0.780 | 0.796 | 0.816 |

| adjusted R2 | 0.780 | 0.796 | 0.815 |

| β (standardized partial regression coefficient) | |||

| (IPs+IPh)/2 | 0.226** | 0.268** | 0.202** |

| [3] | [2] | [3] | |

| IN | 0.331** | 0.358** | 0.339** |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | |

| IC | -0.001 | 0.024** | 0.024 |

| [6] | |||

| IO | 0.174** | 0.117** | 0.142** |

| [4] | [7] | [4] | |

| IE | 0.244** | 0.259** | 0.328** |

| [2] | [3] | [2] | |

| IPo | -0.003 | -0.027** | 0.000 |

| [5] | |||

| ICul | -0.022* | -0.048** | |

| [7] | [5] | ||

| IOv | general WB | SWLS | |||||||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | |

| R | 0.887 | 0.895 | 0.904 | 0.833 | 0.799 | 0.847 | 0.738 | 0.686 | 0.746 |

| R2 | 0.787 | 0.802 | 0.818 | 0.693 | 0.639 | 0.717 | 0.545 | 0.470 | 0.557 |

| adjusted R2 | 0.787 | 0.801 | 0.817 | 0.693 | 0.639 | 0.717 | 0.545 | 0.470 | 0.557 |

| β (standardized partial regression coefficient) | |||||||||

| IPs | 0.682** | 0.689** | 0.632** | 0.663** | 0.674** | 0.681** | 0.576** | 0.570** | 0.608** |

| [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | [1] | |

| IPh | 0.167** | 0.174** | 0.225** | 0.200** | 0.151** | 0.195** | 0.190** | 0.139** | 0.163** |

| [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | [2] | |

| PSSH | APSSH(IOv: overall WB) | APSSH(general WB) | ||||||||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | ||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.038** | 0.016 | 0.024 | 0.047** | 0.01 | 0.016 | 0.046** | 0.01 | 0.015 |

| [19] | [19] | [19] | ||||||||

| Age | -0.018 | 0.065** | 0.124** | 0.013 | 0.102** | 0.150** | 0.010 | 0.104** | 0.154** | |

| [18] | [16] | [18] | [15] | [18] | [15] | |||||

| Occupation | 0.237** | 0.191** | 0.166** | 0.241** | 0.196** | 0.162** | 0.241** | 0.196** | 0.161** | |

| [16] | [17] | [14] | [16] | [17] | [14] | [16] | [17] | [14] | ||

| Marriage | 0.125** | 0.205** | 0.233** | 0.149** | 0.224** | 0.248** | 0.146** | 0.225** | 0.250** | |

| [17] | [16] | [13] | [17] | [16] | [13] | [17] | [16] | [13] | ||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | 0.723** | 0.723** | 0.722** | ||||||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||||||

| Exercise | 0.403** | 0.391** | 0.393** | |||||||

| [13] | [13] | [13] | ||||||||

| Diets | 0.566** | 0.567** | 0.568** | |||||||

| [2] | [2] | [2] | ||||||||

| Medical environment | 0.475** | 0.534** | 0.484** | 0.561** | 0.484** | 0.562** | ||||

| [9] | [9] | [10] | [8] | [10] | [8] | |||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.520** | 0.591** | 0.555** | 0.544** | 0.612** | 0.573** | 0.542** | 0.612** | 0.575** |

| [8] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [5] | [6] | [7] | [5] | [5] | ||

| Educational environment | 0.535** | 0.652** | 0.612** | 0.550** | 0.682** | 0.628** | 0.550** | 0.682** | 0.629** | |

| [5] | [2] | [2] | [5] | [2] | [2] | [5] | [2] | [2] | ||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.530** | 0.572** | 0.557** | 0.542** | 0.592** | 0.574** | 0.542** | 0.593** | 0.575** |

| [7] | [7] | [5] | [8] | [7] | [5] | [7] | [7] | [5] | ||

| Assets | 0.534** | 0.584** | 0.585** | 0.545** | 0.601** | 0.599** | 0.545** | 0.601** | 0.600** | |

| [6] | [6] | [3] | [6] | [6] | [3] | [6] | [6] | [3] | ||

| Employment stability | 0.451** | 0.538** | 0.525** | 0.464** | 0.555** | 0.538** | 0.463** | 0.556** | 0.539** | |

| [11] | [8] | [7] | [11] | [9] | [7] | [11] | [9] | [7] | ||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.666** | 0.612** | 0.616** | 0.691** | 0.637** | 0.639** | 0.689** | 0.638** | 0.641** |

| [1] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [1] | ||

| General trust | 0.538** | 0.602** | 0.574** | 0.561** | 0.635** | 0.595** | 0.559** | 0.636** | 0.597** | |

| [4] | [4] | [4] | [3] | [4] | [4] | [3] | [4] | [4] | ||

| Disparity recognition | 0.080** | 0.212** | 0.136** | 0.085** | 0.232** | 0.141** | 0.084** | 0.232** | 0.142** | |

| [18] | [15] | [15] | [18] | [15] | [16] | [18] | [15] | [16] | ||

| Disparity elimination | 0.307** | 0.427** | 0.441** | 0.313** | 0.435** | 0.446** | 0.313** | 0.435** | 0.446** | |

| [15] | [12] | [10] | [15] | [12] | [10] | [15] | [12] | [10] | ||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | 0.419** | 0.367** | 0.406** | 0.424** | 0.372** | 0.411** | 0.425** | 0.371** | 0.411** |

| [12] | [13] | [11] | [12] | [13] | [11] | [12] | [13] | [11] | ||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | 0.343** | 0.322** | 0.355** | 0.345** | 0.322** | 0.355** | 0.345** | 0.322** | 0.354** | |

| [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [14] | [12] | [14] | [14] | [12] | ||

| Human rights | 0.541** | 0.475** | 0.484** | 0.560** | 0.487** | 0.499** | 0.559** | 0.487** | 0.500** | |

| [3] | [1]] | [8] | [4] | [11] | [8] | [4] | [11] | [8] | ||

| Civil efficiency | 0.475** | 0.531** | 0.462** | 0.492** | 0.551** | 0.477** | 0.491** | 0.552** | 0.479** | |

| [10] | [10] | [9] | [9] | [10] | [9] | [9] | [10] | [9] | ||

| PSSH | APSSH(IOv: overall WB) | APSSH(general WB) | ||||||||

| Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | Survey1 | Survey2 | Survey3 | ||

| R | 0.794 | 0.818 | 0.739 | 0.816 | 0.840 | 0.762 | 0.815 | 0.840 | 0.765 | |

| R2 | 0.630 | 0.670 | 0.546 | 0.666 | 0.705 | 0.581 | 0.664 | 0.705 | 0.585 | |

| adjusted R2 | 0.628 | 0.669 | 0.542 | 0.664 | 0.704 | 0.578 | 0.663 | 0.705 | 0.582 | |

| β(standardized partial regression coefficient) | ||||||||||

| Ascriptive factors(4) | Sex | 0.026** | 0.016* | 0.076** | 0.033** | 0.022** | 0.074** | 0.032** | 0.022** | 0.073** |

| [15] | [16] | [7] | [13] | [16] | [7] | [13] | [16] | [7] | ||

| Age | -0.061** | -0.049** | 0.003 | -0.036** | -0.016* | 0.021 | -0.039** | -0.014† | 0.024 | |

| [10] | [8] | [12] | [17] | [12] | [17] | |||||

| Occupation | 0.045** | 0.032** | 0.026† | 0.040** | 0.029** | 0.017 | 0.041** | 0.029** | 0.016 | |

| [11] | [12] | [13] | [11] | [11] | [11] | [11] | ||||

| Marriage | 0.026* | 0.023** | 0.051** | 0.031* | 0.027** | 0.056** | 0.031** | 0.027** | 0.057** | |

| [16] | [14] | [10] | [14] | [12] | [9] | [14] | [12] | [9] | ||

| Biological factors(3/2) | Exercise/ Foods | 0.376** | 0.333** | 0.330** | ||||||

| [1] | [1] | [1] | ||||||||

| Exercise | 0.039** | 0.019† | 0.021* | |||||||

| [13] | [15] | [15] | ||||||||

| Diets | 0.183** | 0.165** | 0.167** | |||||||

| [2] | [2] | [2] | ||||||||

| Medical environment | 0.088** | 0.080** | 0.084** | 0.095** | 0.084** | 0.096** | ||||

| [6] | [6] | [7] | [5] | [8] | [5] | |||||

| Natural and Cultural factors(2) | Natural environment | 0.097** | 0.098** | 0.136** | 0.110** | 0.091** | 0.141** | 0.108** | 0.091** | 0.142** |

| [5] | [5] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [4] | [5] | [6] | [4] | ||

| Educational environment | 0.069** | 0.109** | 0.169** | 0.071** | 0.135** | 0.168** | 0.071** | 0.136** | 0.168** | |

| [8] | [3] | [2] | [8] | [2] | [2] | [8] | [2] | [2] | ||

| Economic factors(3) | Income | 0.017 | 0.021† | 0.048* | 0.021 | 0.026* | 0.055* | 0.021 | 0.027* | 0.056* |

| [15] | [11] | [13] | [10] | [12] | [10] | |||||

| Assets | 0.043* | 0.055** | 0.121** | 0.043** | 0.050** | 0.114** | 0.043** | 0.050** | 0.113** | |

| [12] | [7] | [5] | [10] | [7] | [5] | [10] | [7] | [5] | ||

| Employment stability | 0.001 | 0.033** | 0.003 | 0.003 | 0.036** | -0.005 | 0.003 | 0.036** | -0.007 | |

| [11] | [10] | [10] | ||||||||

| Societal community factors(4) | Stratification satisfaction | 0.298** | 0.118** | 0.173** | 0.318** | 0.130** | 0.195** | 0.316** | 0.130** | 0.199** |

| [1] | [2] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [1] | [1] | [3] | [1] | ||

| General trust | 0.105** | 0.101** | 0.145** | 0.121** | 0.126** | 0.154** | 0.120** | 0.128** | 0.155** | |

| [4] | [4] | [3] | [3] | [4] | [3] | [3] | [4] | [3] | ||

| Disparity recognition | -0.008 | 0.016* | 0.046** | -0.006 | 0.026** | 0.041** | -0.007 | 0.026** | 0.040** | |

| [16] | [12] | [13] | [12] | [14] | [12] | |||||

| Disparity elimination | -0.020† | 0.009 | 0.031 | -0.018† | 0.006 | 0.027 | -0.018† | 0.006 | 0.026 | |

| [17] | [16] | [16] | ||||||||

| Political factors(4) | Fairness/ Justice | 0.028† | -0.009 | -0.058* | 0.024 | -0.009 | -0.055* | 0.024 | -0.009 | -0.054* |

| [14] | [9] | [10] | [11] | |||||||

| Anti-corruptive fairness | -0.064** | -0.042** | -0.006 | -0.070** | -0.048** | -0.019 | -0.069** | -0.049** | -0.021 | |

| [9] | [9] | [9] | [8] | [9] | [8] | |||||

| Human rights | 0.107** | 0.029** | 0.078** | 0.111** | 0.024* | 0.082** | 0.111** | 0.023* | 0.083** | |

| [3] | [13] | [6] | [4] | [15] | [6] | [4] | [15] | [6] | ||

| Civil efficiency | 0.077** | 0.038** | 0.060** | 0.090** | 0.041** | 0.064** | 0.088** | 0.041** | 0.065** | |

| [7] | [10] | [8] | [6] | [9] | [8] | [6] | [9] | [8] | ||

| 1 | [1] Cells are counted only when the sign(+ or -) of correlations is the presumed direction. |

| 2 | [2] Equality and equity here correspond to arithmetic and geometrical equality/jusitce in Aristotle’s political philofsophy. The concept of fairness are, in our view, four-dimensional, and there are are two other kinds of fairness: compliance(fairness as law-abidingness) and reciprocity(firness as reciproccity) [30] [9] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).