1. Introduction

Telerobotics is an emerging technology enabling remote operation of robotic systems and platforms. It holds transformative potential across both military and civilian domains. Machine fleets may be operated from central operating rooms by “telerobotics”, literally meaning robotics at a distance. In telerobotics, there is always a human operator-in-the-loop aspect in order to carry out various operational aspects - from high-level task planning and related decisions that leave the robot with the responsibility for the actual task execution [

1], down to low-level command and control communications that directly operate the robotic platform. Regardless of the level of involvement of the remote operator, the need remains for a control feedback loop between the operator remotely observing the robot’s environment via a variety of sensor feeds and control communications that send operational commands to the robot for execution.

In the military domain, telerobotics can enhance safety by allowing soldiers to control unmanned vehicles for reconnaissance, hazardous material disposal, and combat missions from a safe distance. Civilian applications are equally expansive, ranging from advanced medical surgeries performed by specialists controlling robotic arms, to autonomous robots being remotely controlled for performing search-and-rescue (SAR) operations in disaster-stricken areas [

2]. Telerobotics can also benefit industries such as agriculture and construction, with remote-controlled machinery optimizing crop management and robots performing dangerous tasks to minimize human risk and expand operational capabilities. The rise of Virtual Reality (VR) technologies also increases the performance of teleoperation in many domains, such as remote education [

3], and nuclear [

4], but where latency management is especially important to avoid VR sickness [

5]. Finally, regardless of the application domain, teleoperation will be needed even when the autonomy level of robotics increases, either by providing human demonstrations for Machine Learning (ML) algorithms (e.g., [

6]) or as a fallback when autonomous systems fail, even for autonomous driving [

7]. However,

To achieve this goal, telerobotics connects a robotic platform on one side to an operator on the other side through a network interconnect with varying complexity, performance, and scale. To provide direct user control, the robot is programmed to follow the motions of the master device. The robotic platform, often equipped with sensors, actuators, and cameras for feedback, receives commands from the operator and transmits data back to the operator through a network connection. These network connections for telerobotics can range from simple local networks to intricate global networks. These networks are comprised of a variety of hardware and software components and may implement different access controls, such as Virtual Private Networks (VPNs). These additional control schemes may add additional network routes for security and can affect the overall latency of robotic control [

8]. Some telerobotics systems provide force feedback as a sensor data stream, such that the user device not only measures motions but also displays forces to the user - via informational displays or haptic controller feedback. The user interface becomes fully bidirectional, with such telerobotic systems often referred to as being bilateral. Both motion and force may become the input or output to/from the user. This bilateral nature makes the control particularly challenging: with multiple feedback loops and even without environment contact or user intervention, the two devices form an internal closed loop, and communication delays raise significant challenges concerning the stability of the system [

9,

10].

The overall communications sent between the operator and robot in such bilateral telerobotic environments consist of a control input from the operator to the robot and feedback from the robot to the operator. The operator initiates communication by using a designated control system, which can be a specialty control system or a simple joystick controller. When an input is received on the control system, the corresponding action is forwarded to the robot. Depending on the system configuration, processing and solving the specific movements, such as joint positions in a robotic arm, may be completed on either the operator or robot side. In most cases, a separate visual feedback loop exists for the operator, often implemented as a camera stream. This visual feedback provides the operator with knowledge of the robot’s position and objects of interest. However, high-resolution video or pictures require a much larger amount of data than the data volume required for control data.

Consequently, this feedback loop may take considerably longer than the command’s being sent. Because of this, the robot may move more than the controller intended. Ultimately, reliable and safe telerobotics thus requires that the latency for both the control and feedback loops are minimized as much as possible in order to provide a near-presence operator experience.

Latency in telerobotic systems encompasses several components, including transmission delay, processing delay, propagation delay, sensor and actuator delay, and feedback delay. Transmission delay is influenced by network bandwidth and congestion, while processing delay depends on the computational power and software efficiency of both the operator’s and robot’s systems. Propagation delay is related to physical distance, while sensor and actuator delays impact how quickly the robot can respond. Feedback delay involves the time needed for the operator to receive and interpret sensory information. To reduce overall latency and improve the quality of service (QoS) and overall user experience, a comprehensive study of each factor is necessary. Our extensive literature review could not find such study, however. Therefore, this paper provides an in-depth analysis of these contributing elements.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 reviews publications that relate to this work, and

Section 3 goes into detail on the methodology of our work.

Section 4 provides an overview and discussion of the results we obtained, and

Section 5 presents the conclusions of the work and suggestions for future work.

2. Related Works

Telerobotics and teleoperations are a rapidly growing domain, with a growing number of worldwide installations and capability deployments. Teleoperations are also a continuing focus within the research domain and the scientific literature. For example, in [

11] the capability is introduced for improved telesurgery to be implemented over the well-established and widely used Robot Operation System (ROS) [

12]. The authors of [

13] worked on bringing 5G together with mobile edge computing to explore whether robotic telesurgery is feasible in such an environment. The authors created tests to analyze the difference between 4G and 5G in terms of delay, jitter, and throughput. In [

14], the authors used a Virtual Reality (VR) headset with the controllers to control a Rethink Robotics Baxter robot. The authors used ROS for the Baxter robot. They measured latency performance as well as conducted tests exploring the types of objects that the robot could successfully manipulate. A teleultrasound robot was used to conduct network latency tests under a Wireless Local Area Network (WLAN) connection and a Virtual Local Area Network (VLAN) in [

15]. The authors also measured the displacement error for both WLAN and VLAN network conditions. The authors of [

8] created their own robotic arm and attached a video camera onto the arm to test the teleoperation latency under various communication channels.

In [

16], the authors determined what is an acceptable latency for telesurgery. They tested 34 subjects, each of whom had a different level of surgical expertise. The paper concluded that the acceptable delay for telesurgery needs to be below 100ms. The authors of [

17] used a Phantom Omni Haptic device and a SimMechanics model to mimic an industrial robot arm. These experiments were conducted over various connections between Australia and Scotland, including segments utilizing 4G mobile networks. In [

18], a telesurgery system with image compression adapting to the available bandwidth was tested between Beijing and Sanya. In that study, non-invasive surgical operations on animals were conducted, with the measured latency ranging from 170ms to 320ms. They determined that reducing image quality can help reduce and control latency for telesurgery, but 320ms latency was an upper limit of latency for safe surgery. The authors of [

19] used a master-slave configuration of 3 robots, each using the ROS operating system. The authors explored the boundaries of achievable Wi-Fi performance for telerobotics, as well as explored the capabilities within ROS for such tasks. In remote driving, 300ms latency was found to deteriorate the performance [

7], whereas smaller but slightly varying latency was found more acceptable.

The work in [

20] discusses the teleoperation of automated vehicles. The authors measure the latency of the teleoperation setup and attempt to reduce the latency. The authors of [

21] present the effect of delay on robot mimicry in handwriting, with the operator’s only feedback being the robot’s writing. They found that users were able to adapt to any slowness of a robot’s movement but not onset latency as the robot was writing. In [

22], the authors discuss the merits of using ROS for teleoperation. The authors discuss ways to improve ROS to allow better response times and reduced latency. The tests conducted in this work helped identify areas of improvement within ROS for teleoperations. The authors of [

23] discuss how 5G represents a significant potential improvement for telerobotics compared to 4G, and also illuminate the further advantages that may be brought about by 6G, including considerable reductions in latency compared to previous generations of cellular networks. The work in [

24] explores Virtual Reality (VR) for teleoperations. The focus of this work is on improving the visual quality of VR and mitigating the risk of motion sickness resulting from VR usage. The authors also measure the visual latency and display-to-display latency.

The authors of [

25] test tele-ultrasound over multiple network conditions, including LTE, 5G, and Ethernet. They suggest that this particular teleoperation domain is rapidly approaching feasibility over such network technologies. The authors in [

26] explore various areas for improvement related to robotic surgery, for example, in instrument motion scaling. They tested various configurations to determine their relative merits and benefits. Their tests indicated the potential to achieve benefits to tasking times in telesurgery by using specific configuration sets for motion scaling.

The work by Tian

et al.presented in [

27] illustrates the potential for telerobotic surgery to be conducted over 5G cellular networks. They did surgery on 12 patients of various ages. They measured an average of 28ms during these surgeries, conducted with a 100% success rate. These tests were conducted between a host hospital where the patient and surgical robot were located and 5 test hospitals located in different cities where the surgeon was located. Similarly, in [

28], the authors used 5G for telesurgery experiments across a separation distance of 300km between the host and client. They used a video camera and reported that all the surgeries were successfully completed. The network latency was approximately 18ms throughout these tests for control communication and about 350ms for the video camera feed.

Isto

et al.and Uitto

et al. [

9,

10] have presented a demonstration system and experiments for a remote mobile machinery control system utilizing 5G radios and a digital twin with a hardware-in-the-loop development system. A 5G test network was used by harnessing the network within a virtual demonstration environment, with remote access from a distance of 500 – 600 km. Virtual private networks were utilized to better represent real-life scenarios. The haptic remote control experimental results indicated that with a suitable edge computing architecture, an order of magnitude improvement in delay over the 5G connection compared to existing LTE infrastructure was achieved, resulting in an achieved latency as low as 1.5ms.

To summarize our literature review, we were unable to find any study that could provide an in-depth latency analysis of telerobotics investigating the contributing factors to the end-to-end latency in typical telerobotics applications.

The work we are presenting in this paper thus explores network latency for a larger variety of network topologies and separation distances compared to the work presented thus far in the scientific literature. It also conducts an in-depth latency component analysis to further illuminate the contributing factors to the end-to-end latency in typical telerobotic applications.

3. Methodology

Remotely controlling a physical robot over a network connection introduces a number of factors contributing to the overall performance of its control feedback loop. One such factor that significantly contributes to the overall user experience of this telerobotics system is the network latency. A high latency results in a separation in time between observation and control response and is thus detrimental to reliable and accurate telerobotic operation.

To identify latency components that have the largest effect on the control loop, the setup utilized in our research was comprised of both a dynamic and a static segment.

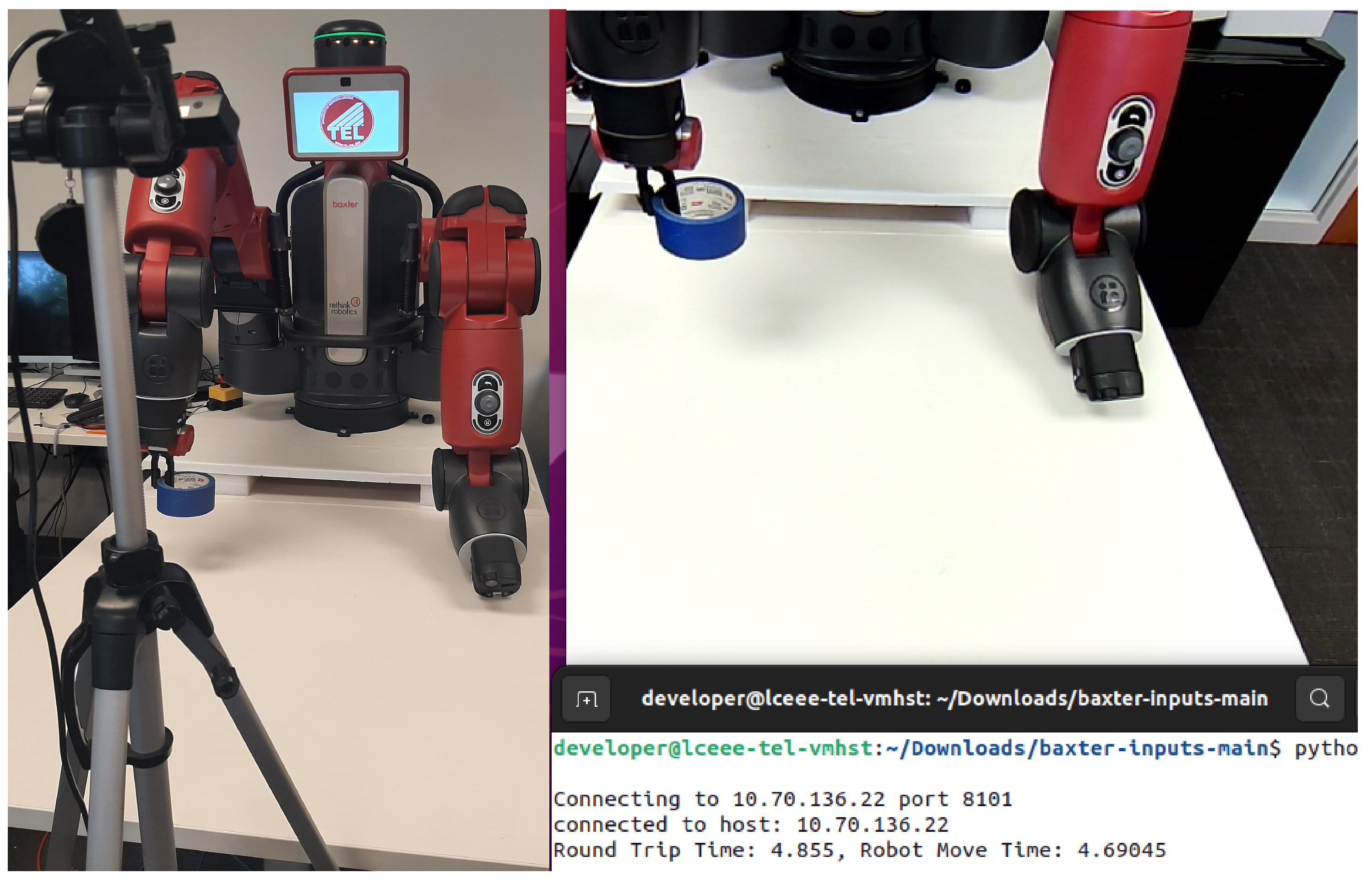

The components of the static segment include an in-lab Baxter robot [

29] by Rethink Robotics, shown in

Figure 1 and a desktop server that is the control host for the robot in our setup. The robot was connected via an Ethernet link through a managed switch to the host computer, which provided a server interface for external devices to connect to it, as well as a Robot Operation System (ROS) Python script [

30] for operating the Baxter robot. Our control method utilizes Baxter’s internal IK solver. Thus, every "move" transaction triggered by the teleoperator resulted in an Inverse Kinematics (IK) solver request/response cycle, followed by a ROS Move request/response cycle between host and robot. Our teleoperations script was optimized to bypass service availability checks in order to facilitate faster host operations. Since the local network configuration between the host and robot is static, the latency of these service interactions is highly stable throughout our tests.

The teleoperations client is the primary component within the dynamic segment of our test infrastructure. This client connects to the host server. Utilizing a game controller and associated Python library [

31], we capture control input from the controller and use these to transmit "Move" requests from the client to the host server. Each controller input was mapped to certain move commands comprised of speed and direction for the robot to move its arm and end effector by. Since the Baxter robot’s ROS interface supports the utilization of Cartesian coordinates for arm placement, we utilize Cartesian controls for movement and button presses for gripper open/close controls. When the host receives a "Move Request" from the client it queries the Baxter’s internal IK solver for the corresponding 7-joint solution to the movement request and, if a valid response is received, sends the joint solution request to the robot to trigger the actual movement.

The controlling client is connected to the host via a variable network setup. It is this variability that allows us to evaluate different network scenarios and control distances in our tests. To then analyze the impact of the client’s network connectivity has on the end-to-end latency of our telerobotic application, we conducted extensive tests for each network scenario we were targeting. These specific scenarios include:

a simple Wired network connection between the client and host through our internal University network, resulting in minimal network distance between client and host,

a connection involved the University’s Wi-Fi network as well as a VPN connection to expand our network radius to the network edge,

a Mobile Hotspot 4G Cellular connection that required the client to connect via Wi-Fi to the Mobile Hotspot, which in turn connected through the cellular service network to the University’s network edge and its VPN server, further widening the distance between client and host,

and finally, a connection by a duplicate of our client setup established at VTT in Finland through a transatlantic connection back to our University’s network edge and its VPN service to maximize the network distance between client and host.

For the visual feedback control loop within this system, a webcam is connected to the host server. Utilizing a low-latency video streaming server provided by the host, we enabled the teleoperating client to visually observe the robot’s activities from afar. The client connects to the video server on the host and renders the received video feed to the screen during our tests. The server and client scripts use the Python OpenCV library [

32].

3.1. Data Collection

Given the varied locations of the client within our network tests, it was impossible to accurately track each latency component of the entire system through traditional packet analysis. As a solution to this issue, TCP packets were utilized to track the end-to-end Client Request Duration for the client to request a movement, measured from the transmission of the "Move" Request until it is acknowledged as completed by the host using the "Move Complete" Response, as well as various individual constituent processing times between the host and the robot, as shown in

Figure 2. The IK Solver Request, IK Solver Response, Move Request, and Move Response are all ROS packets initiated from the host server to control the robot. Furthermore, by tracking the host’s processing duration from receiving the client’s Move Request to when it transmits the Move Complete Response and including that timing in the response message, we can subsequently also determine the round trip time (RTT) between the client and the host.

As each "Move Request" packet is sent from the client to the host, the client uses an internal timer to track the total time until a response is received from the host server. The host also utilizes internal timers to track the total IK solver time, move request time, and total processing time. This is then attached to the "Move Complete" packet for latency data collection. These results are then aggregated for the statistical analysis presented in

Section 4.1 of this paper. For camera latency, a precision timer was displayed on the client’s screen, the webcam was pointed at the timer, and the client then connected to the camera video stream to render the received video next to the displayed precision timer. Screenshots were then taken of the resulting difference between the streamed timer video feed and the directly displayed precision timer, acting as the ground truth, in order to measure the end-to-end camera latency. Utilizing this setup locally on the host device without a network connection, we found the webcam’s latency to be 100ms at 30 fps. Since this methodology cannot be utilized within our transatlantic tests, results are only presented for the first 3 latency cases.

3.2. Control Loop

The visual feedback in the control loop is independent of the controller inputs, and during normal network conditions we expect the latency to have less variability compared to the physical control of the robot. The client is able to connect and view the robot from a static position, and no additional control was given over the camera feed at this time.

Control over the Baxter Robot was limited to a single arm, with a bounding box defined in front of the robot as its operating area. This allowed for seamless mapping of controller inputs for smooth control over the robot, allowing for precision tasks such as gripping and moving objects. However, this added complexity for edge case detection and handling along the perimeter of the bounding box in order to prevent the robot from exiting its operating area, which would result in the possibility of failing to obtain valid IK solutions. To further limit this risk, we equipped the client with a reset command to re-center the robot arm within its operating area. An overview of the test platform, with the robot performing a task compared to what the operator sees, is present in

Figure 1.

3.3. Latency using Control Tests over the wired University Network

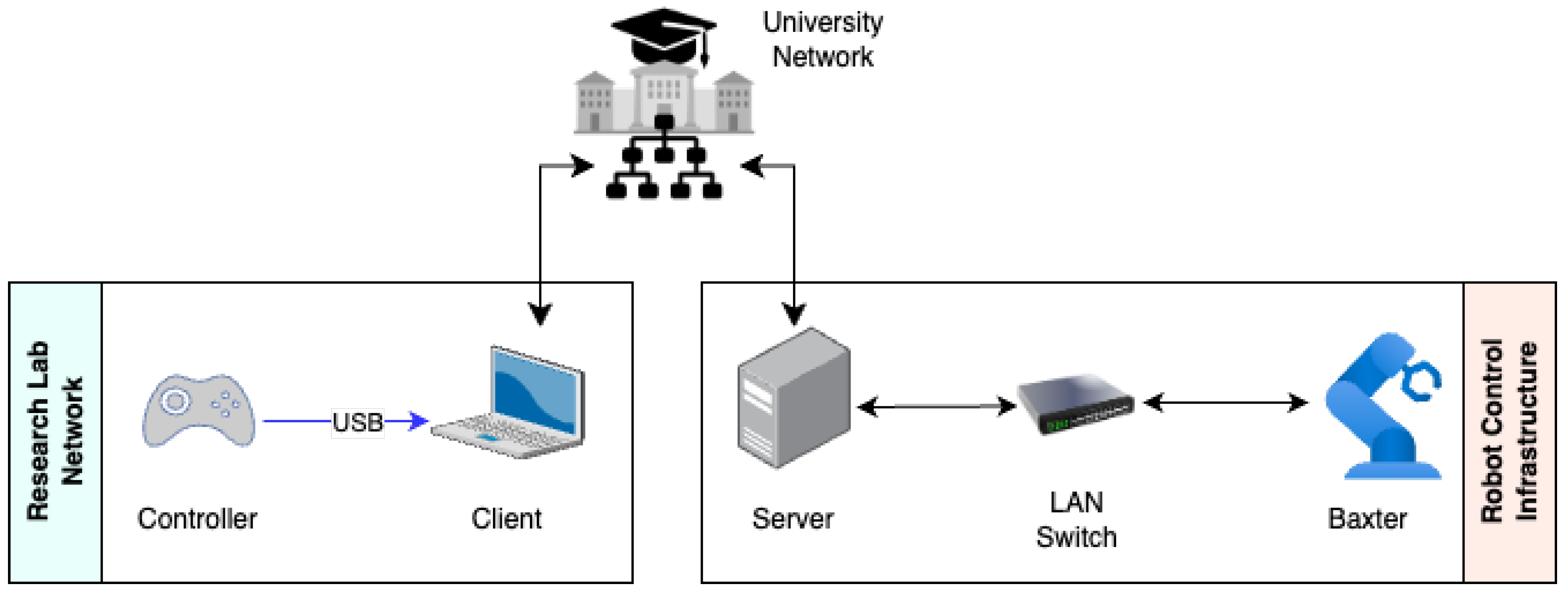

The initial tests performed were to conduct baseline and validation testing of controlling the robot over the same local university network to validate the correct operation of the control and visual feedback loops. This network scenario, shown in

Figure 3, also allowed us to ensure the accuracy of the precision timers within each script, as packets were captured on both the client and host server’s Ethernet interfaces.

Once the measurement methods were confirmed to be accurate, results were collected from the control script. This script initiated a connection between the client and the host server and issued control commands. This network configuration was also utilized to test the effective movement command rate that can be sent from the client to the Baxter robot. While the Baxter accepts packets at much faster rate, even a 100ms delay between command packets still resulted in a smooth robot movement within our control scheme.

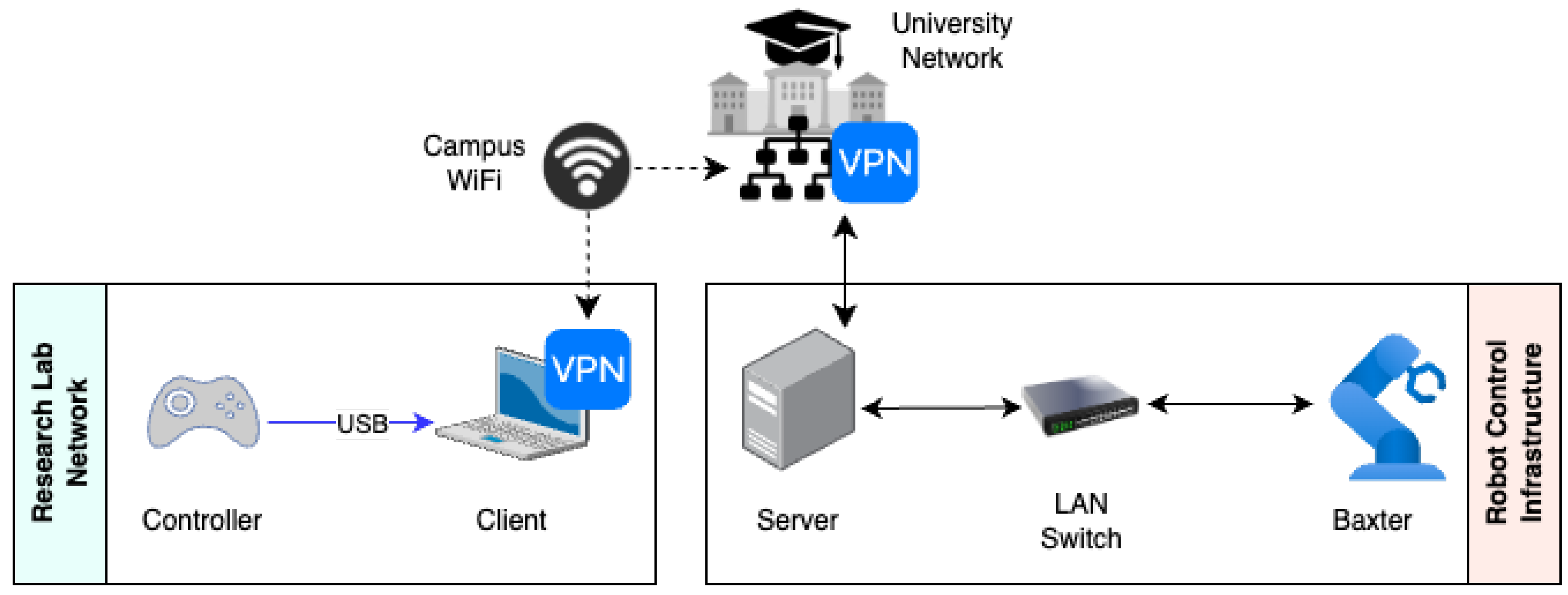

3.4. Latency Evaluation over the University Wi-Fi and a VPN at the Network Edge

The next test moved the client connection from the University’s internal network to a separate Wi-Fi network, which was still located on the University’s campus. This test also introduced a VPN connection into its topology to expand the network distance in these tests to the network edge. The client physically remained in our lab, but its network path length greatly increased, as shown in

Figure 4.

This network configuration introduces additional hops within the network path, including the VPN server, which increases security but adds to the overall latency. Results from this network configuration were collected strictly through each script’s internal timers, with the obtained results presented in

Section 4.1 further below.

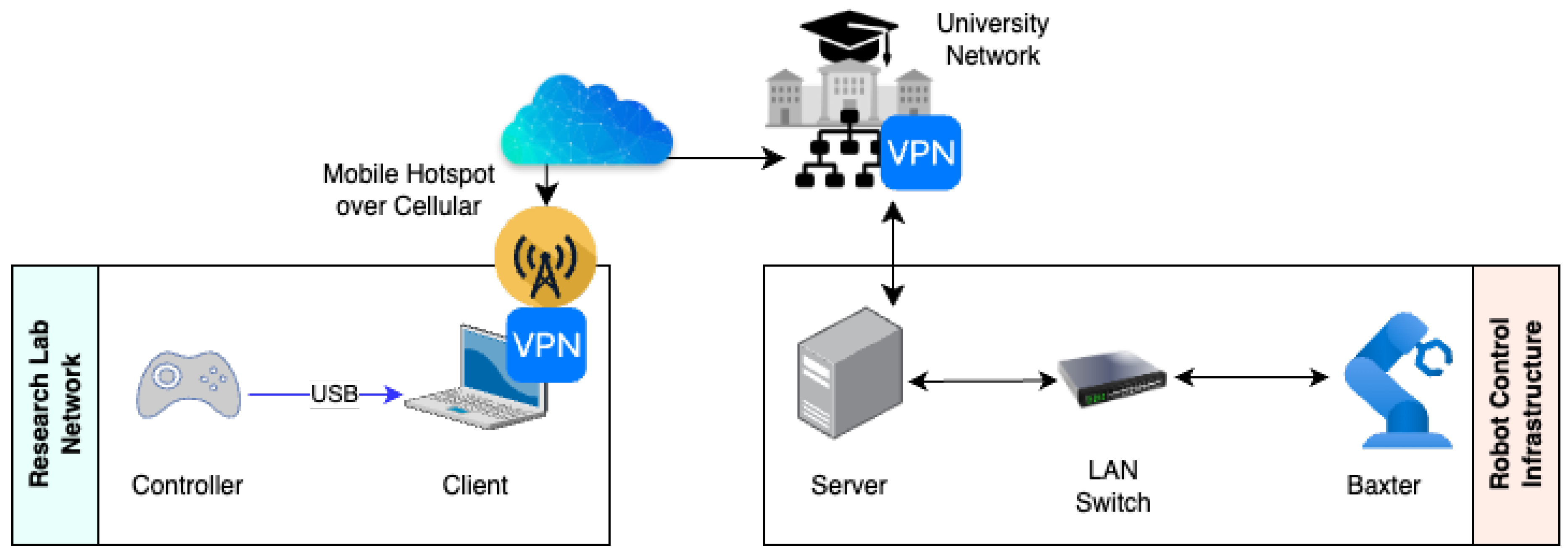

3.5. Latency Evaluation over a Mobile Hot-Spot and Edge VPN

Telerobotic operations may not always have strong network connections. In the case of rural or disaster-stricken areas, wireless access may be limited. Thus, our third test scenario we evaluated is the client connecting through a Mobile Hotspot over a cellular network, shown in

Figure 5. This test also includes the same Edge VPN, but further increases network distance and restricts network resources compared to the previous test scenarios. The cellular network utilized in this test was a commercial 4G network, which adds additional network routing through the cellular provider’s backhaul network before being routed through the University’s VPN. This also adds complexity to session establishment compared to the previous Wi-Fi network test.

3.6. Latency Evaluation using a Transatlantic Connection and Edge VPN

The final network scenario studied in this paper connected the collaborating researchers at the VTT Technical Research Centre of Finland to the Advanced Telecommunication lab in Lincoln, Nebraska, USA, as shown in

Figure 6. For this test, both VTT and the University network utilized high-speed connections, with the major network challenge arising from the inclusion of a Transatlantic Internet connection and the continued use of the Edge VPN.

3.7. Latency Evaluation of the Camera Feed across different Network Scenarios

Three tests were conducted for latency measurements with the camera feed, each measuring the latency of a full frame being received by the client from the host network. These tests were conducted with the camera pointed at a 100 s precision timer displayed on the screen via a command line interface (CLI) tool. The client computer then connected to the host’s video feed to display the timer video feed in an adjacent window. 100 screenshots were then taken for each test, displaying the total latency introduced from transmitting a frame over the network. As previously mentioned, the frame latency required for extracting a frame from the USB camera was 100 ms, so any latency above this time is added by the network. Since this measurement of camera latency was restricted to local network configurations, tests of a virtual network connection through a loopback interface on the same client machine, a local wired network, and Wi-Fi connection through VPN were tested. Our tests utilizing the mobile hotspot were highly inconsistent, likely due to the limited 4G performance experienced by the Mobile Hotspot itself, and thus resulting in us discarding these tests from consideration.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Initial Tests and Result Collection

For each test outlined in

Section 3, statistical analyses of the gathered results were performed, including mean, median, standard deviation, as well as the 95% confidence interval for each measured latency. Each measurement shown in

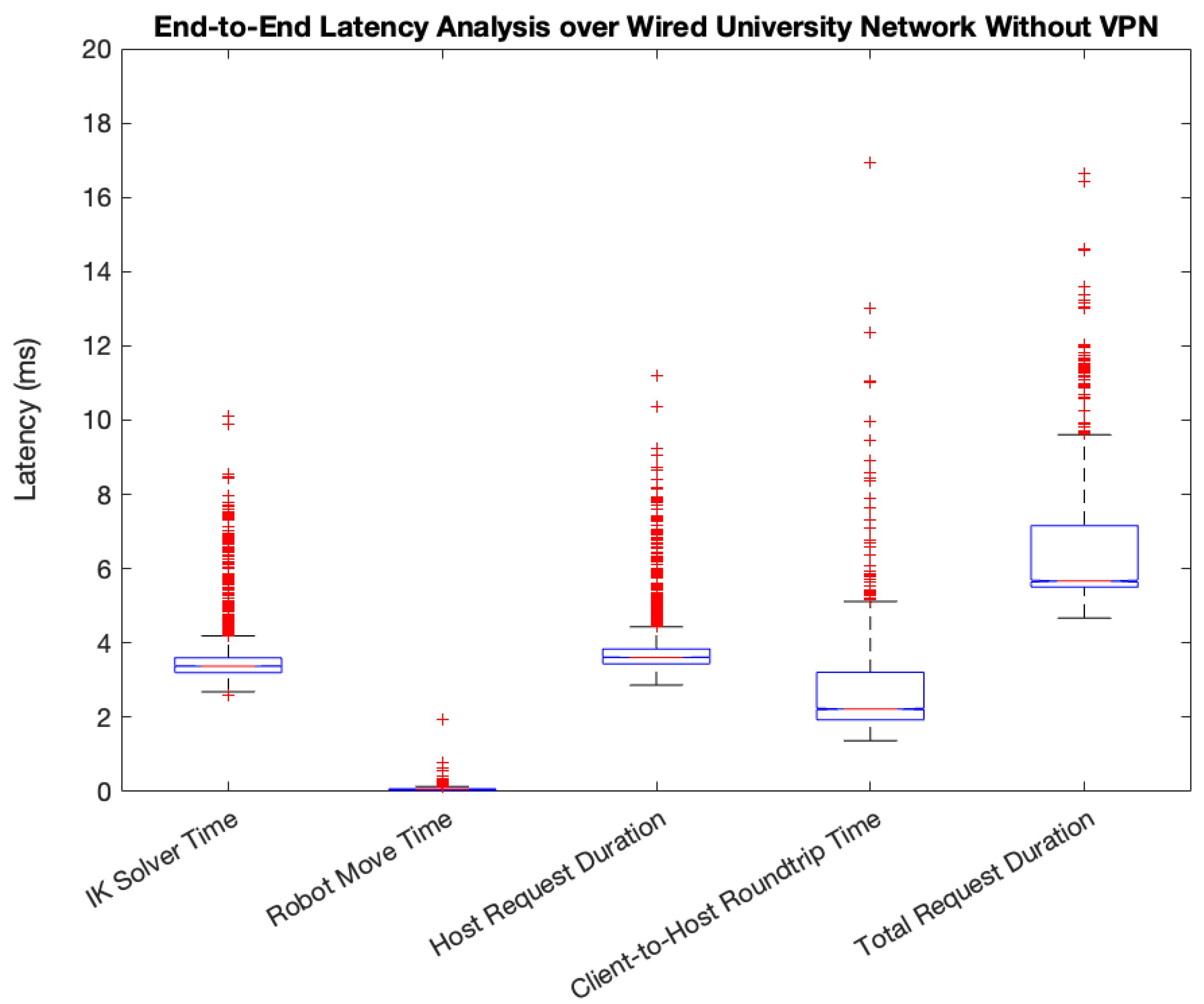

Figure 2 was collected for each of the targeted network scenarios. The results for the wired LAN scenario are shown in

Figure 7, which represents data from 8,730 samples taken during this experiment. From these results, we can see the robot’s IK solver contributed the highest latency for the total request duration, while the Baxter accepts movement commands with negligible latency.

Table 1 represents the Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, and Confidence Interval of the Round Trip Time. The confidence interval for this analysis is set at 95 percent. The observed mean latency is 6.616 ms, which indicates that in this scenario, we could achieve a very low latency that also remained low and consistent throughout the entire test. Out of the measured samples, none exceeded 18 ms, and these samples were influenced by the IK solver time. The 95% Confidence Interval (CI) is 0.3966, giving us a range of 6.220 ms to 7.013 ms. These results show a high level of reliability within the LAN test and, similarly, a high reliability of the robot in responding to movement commands. Finally, this test confirmed that the robot reliably handled the bounding box controls for its operating area, with no failures observed by the IK solver.

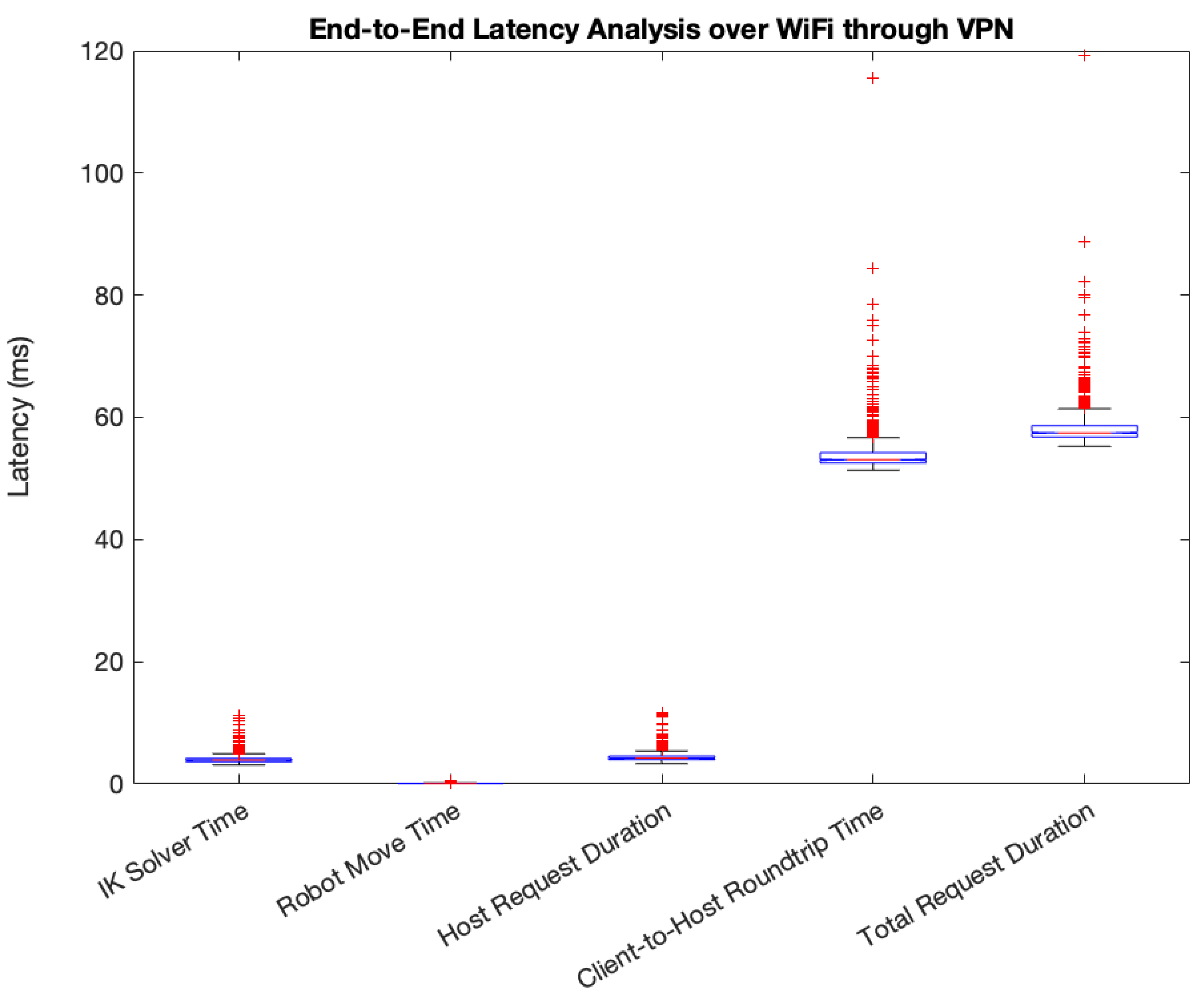

Figure 8 represents the collected data for the Lab WiFi-to-University network connection scenario, including the use of the VPN. 1019 samples were recorded during this experiment. The Round Trip Time and total request duration have noticeably increased in value compared to the wired LAN scenario. Most importantly, we observe that the impact of the network scenario change and corresponding latency increase does not appreciably influence the total duration of the static control loop elements between the host and the robot when compared to the previous test. However, this test shows the impact that a network topology utilizing access control, specifically a VPN, can have on an application’s end-to-end latency. While the test was conducted at the same physical location, the latency is over 8 times larger than what we observed during the initial Wired LAN test. This is, however, a necessary component for telerobotics, as access control mechanisms help ensure the safety and security of the robot against malicious actors.

Table 2 represents the corresponding Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, and Confidence Interval of the Round Trip Time. The Mean latency measured is 58.459ms, which is still below the previously recommended 100ms for critical applications such as telesurgery [

16]. The Median is 57.455ms, a difference of 1ms from the mean, which shows that the data is consistent throughout the samples. The Standard Deviation is 3.628, from which we can conclude that there is slightly more variance in the samples we collected than in the previous test. The 95% Confidence Interval is 0.222, which gives a range of 58.237ms to 58.681ms. These results show that implementing a VPN, while resulting in an increased latency, does not introduce enough latency to make telerobotics infeasible.

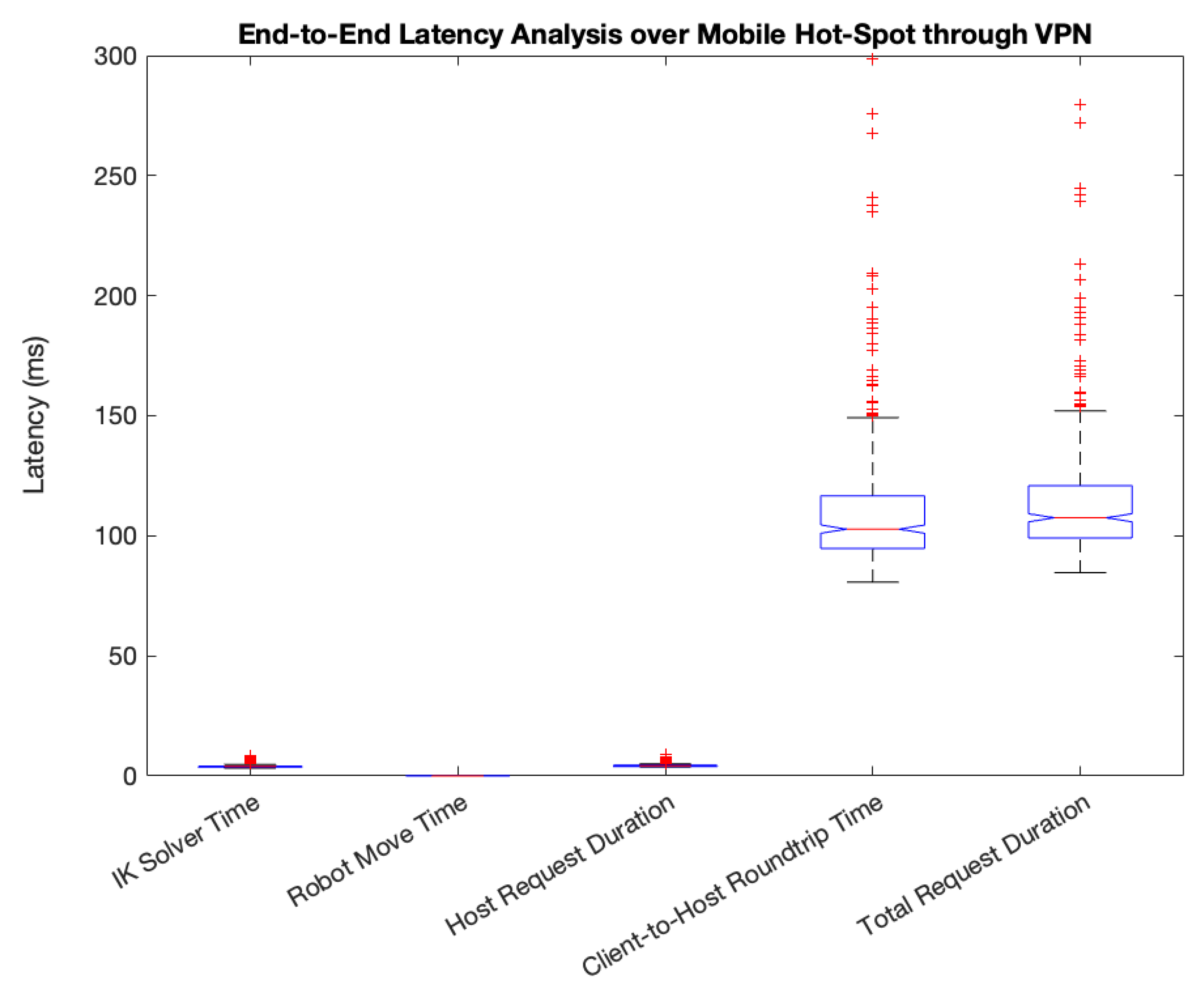

With the testing of the VPN-controlled network access over Wi-Fi completed, the same test was performed with a cellular hotspot for the client connection, as opposed to the University WiFi network. This test introduced a cellular network component to these experiments that would require additional cellular session establishment, with more restricted network resources available for uplink communications, especially in terms of throughput, and adds additional network segments and route hops through the cellular provider’s backhaul network before reaching once again our University’s network edge and its access control mechanisms. For this test, 410 samples were taken during our experiments. From the results presented in

Figure 9, we can see that the latency has nearly doubled compared to the previous test, averaging 115 ms for the total request duration. We also observe an increase in outliers that reach as high as 300ms delay, which is approaching concerning levels of delay for smooth telerobotic operation. This illustrates the need for telerobotics research to consider remedies to make telerobotics tolerant to spurious large latency spikes.

Table 3 represents the Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, and Confidence Interval of the Round Trip Time. The Mean of the samples collected is 115.381ms, which shows the latency reaching levels that would be noticeable to the operator. Given that the median is 107.515ms, a nearly 8ms difference, the test data contains more outliers with higher values than previous tests and contains a larger latency spread. Due to this, the standard deviation is 30.577ms, and the 95% confidence interval is 2.960ms, giving us a range of 112.421ms to 118.340ms.

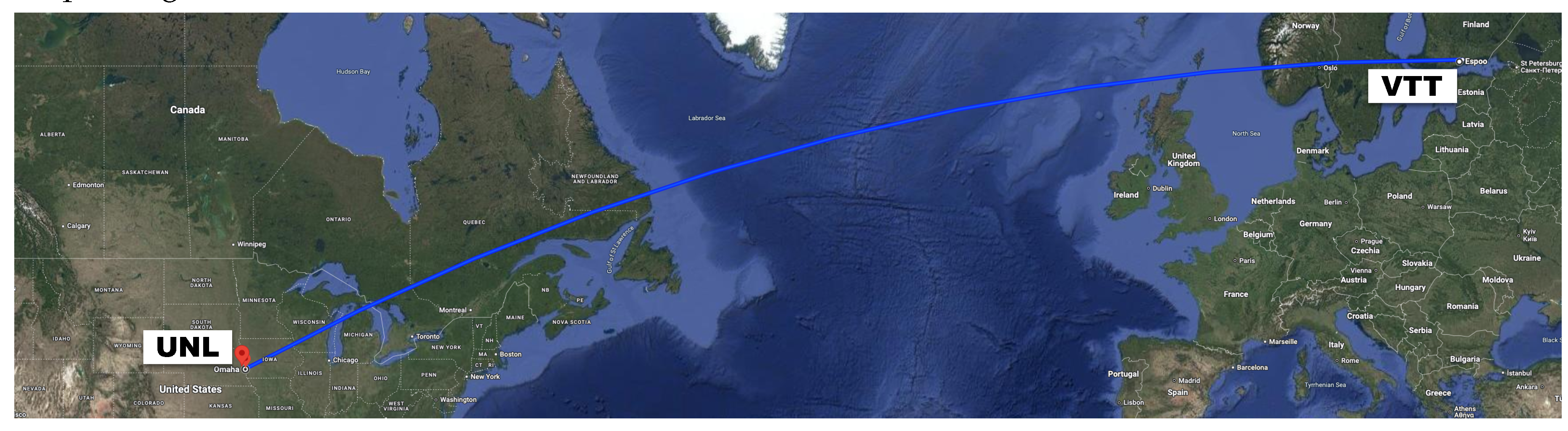

The final test conducted for the operator’s control latency experiments was a connection from VTT in Finland to the University of Nebraska in the United States, with both locations shown in the map in

Figure 10.

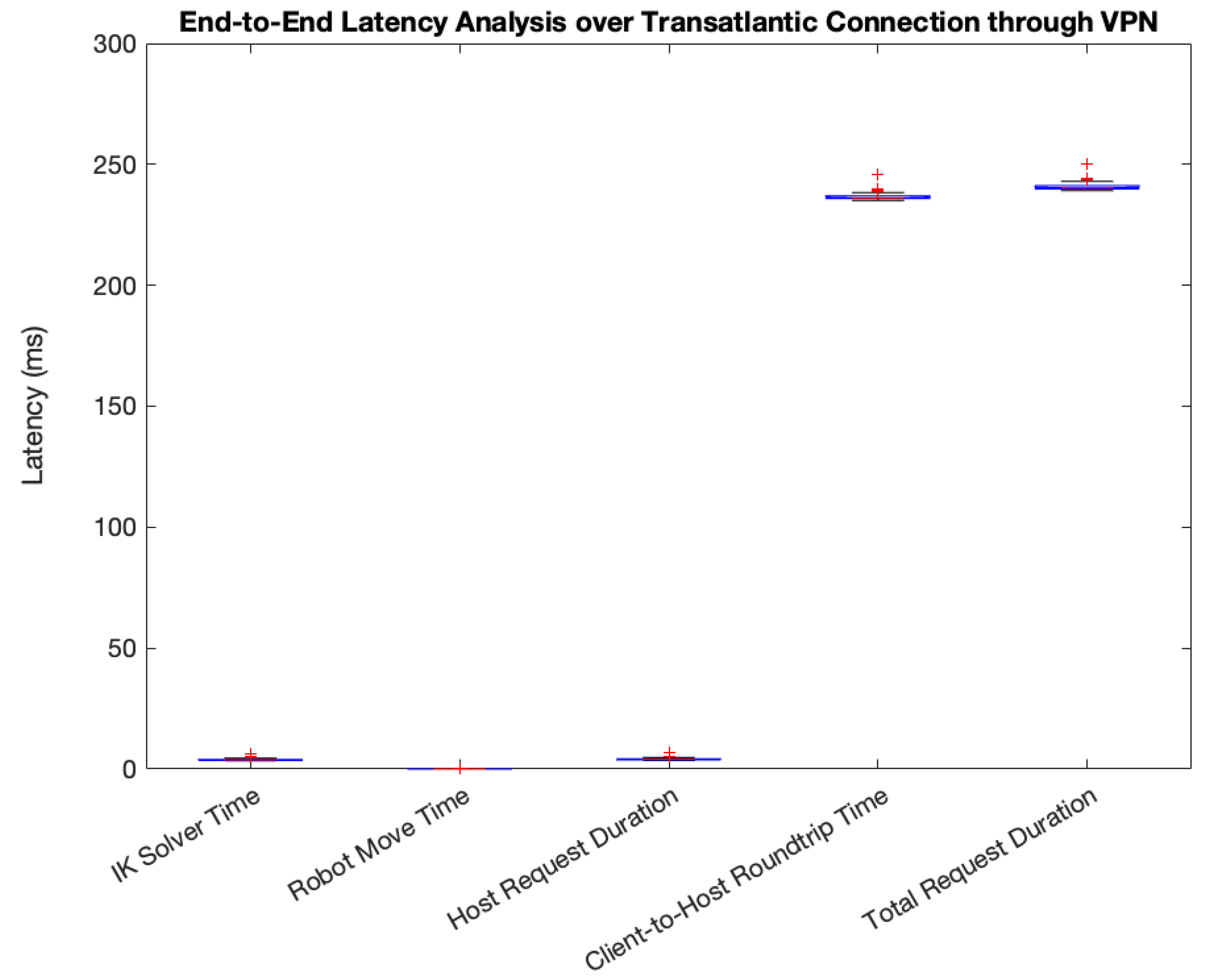

This test provided a substantial challenge to the reliability of the control scripts and video stream reliability, as additional network routes are added through a transatlantic internet connection. However, both VTT and the University of Nebraska each have reliable, high-speed network infrastructures, and consequently, our tests showed high reliability of the overall control elements, as shown in

Figure 11. These results represent the latency of 53 movement request measurements taken during this experiment. The average total request time increased significantly. However, there is increased reliability compared to the previous cellular test. This test also shows the negligible effect of the robot’s processing time on the system’s overall request time. With the increased client-to-host round trip time, our control scheme only sends 4 commands per second to ensure valid execution of the previous command. This slow request interval limit may not be sufficient in some use cases, illustrating the need for complex "request debouncing" techniques to be implemented to ensure stable and reliable telerobotics controls.

Similar to our previous tests,

Table 4 represents the statistical analysis of the tests conducted for this network. The mean value of 240.769 ms, and a median of 240.316 ms, which shows a highly reliable network without much variation. Given the additional network complexities that were added with this test, successful telerobotics operations would require high-reliability network connections on both the operator and robot side. We also see a much lower standard deviation than the previous test of only 1.714ms, which does indicate some variance within the measured latency. The calculated 95% confidence interval is 0.857, giving a range of 239.912ms to 240.855ms.

4.2. Examining the Robot’s Processing Latency in Detail

When comparing the robot processing latency to the overall request duration and client-to-host round trip latency, both the IK solver and Move Request time appeared to comprise a significant portion of the overall latency only in the local Wired LAN connection scenario. That’s a consequence of the low network latency itself and not indicative of a high processing duration, however.

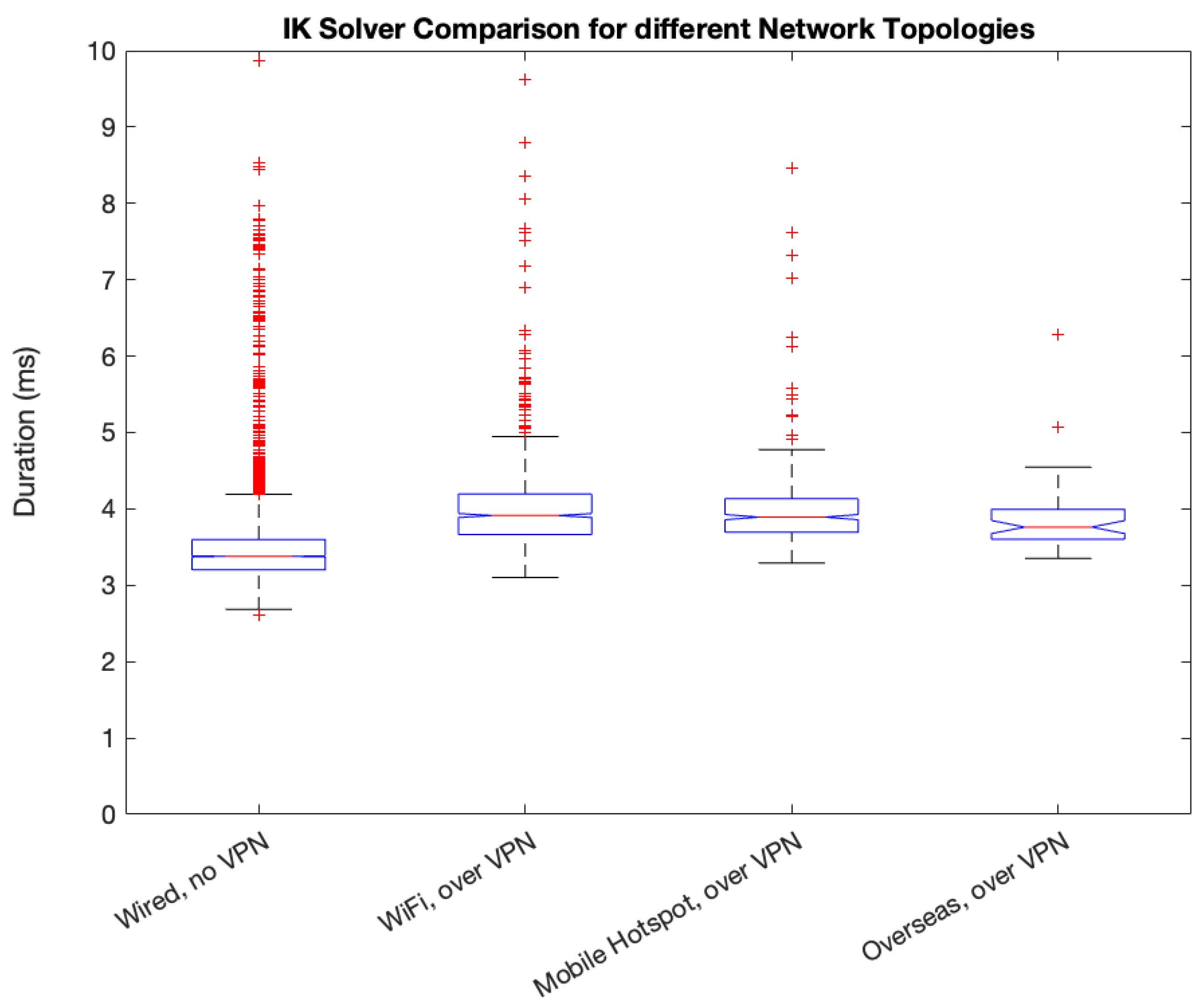

The previous analysis did not make any comparisons between the individual latencies for each network configuration and presented conclusions only in relation to the client-to-host round trip time and total request duration. Regarding the IK solver, some latency may be expected with the complex calculations dependent on arm position and movement request. In this section, we are thus comparing specifically the IK Solver latencies we observed across all four network topology scenarios, with the aim of determining whether there is any dependency between IK Solver latency and network complexity. Our resulting observations are shown in

Figure 12. As can be observed, the average response times remain close to 4ms across all 4 network scenarios, with occasional outliers reaching as high as 10ms.

Thus, the latency contributed by the IK Solver to the total request duration can be characterized as minimal since even in the best-case scenario of a direct Wired LAN connection, the IK Solver accounted for only 4ms out of the measured 58ms total request duration, and independent of the network topology in use between client and host. This is true also for any network access technology usage. Overall, we can observe that the latency distribution remains similar for each of the tested network scenarios. This latency will be treated as static for the context of this paper, as the network has no effect on the robot’s IK performance, and improvements to IK algorithms are outside the scope of this paper.

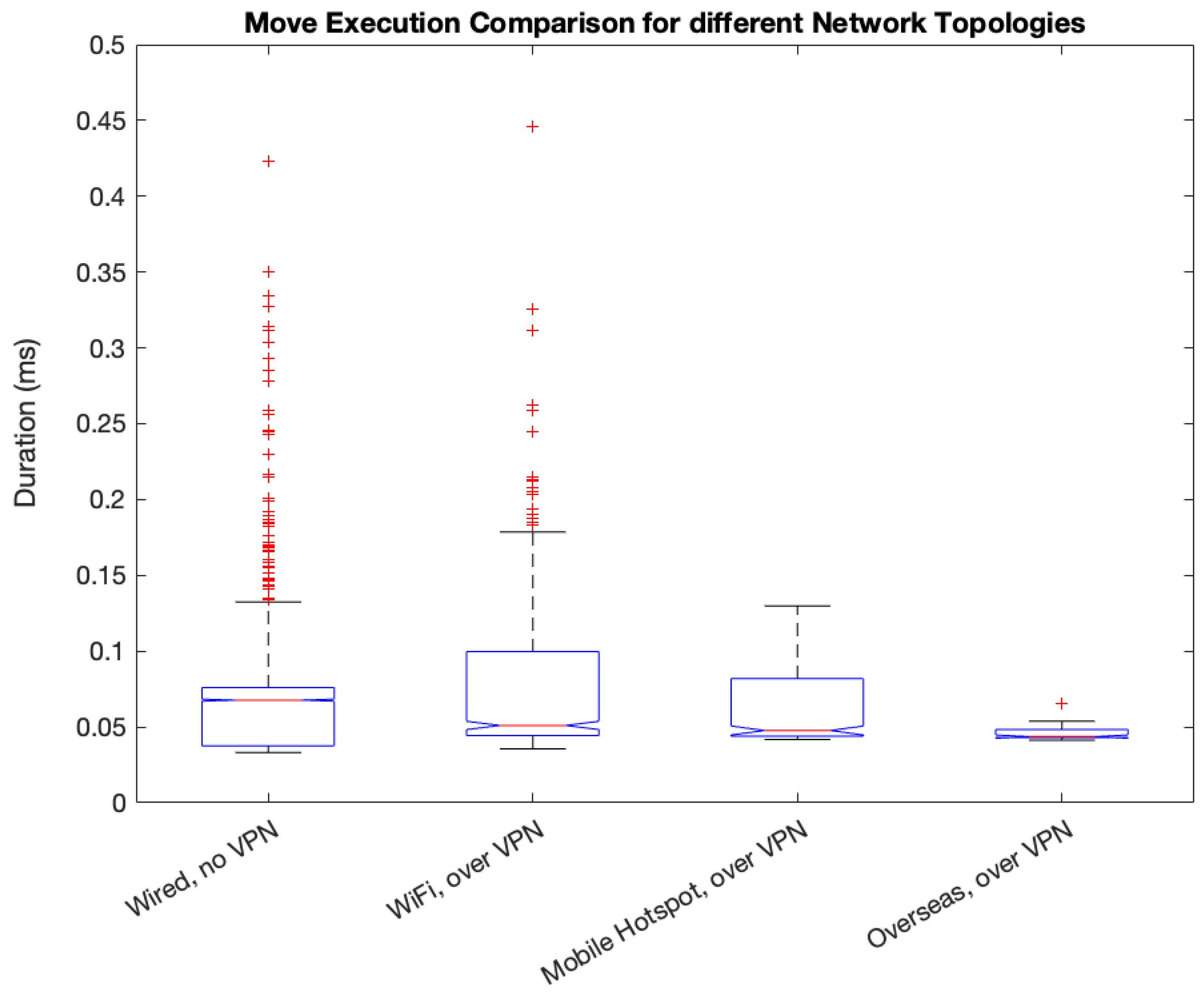

Similarly, when we specifically evaluate the Move Request latency between host and robot, shown in

Figure 13, we observe a similar outcome compared to the IK solver latency. The important characteristic of this test is that it shows that the latency contribution of the Move Request never rises to a full millisecond, indicating minimal computations and network activity for this request within ROS. Given that the latency also remains stable at or below 1 ms across all network scenarios we tested, the latency can be considered static, with minimal impact on the end-to-end latency of each test. We do note that we observed a larger number of outliers within the first tests, which is likely due to the larger number of measurements conducted in these tests.

Since both the IK solver time and Move Request duration have stable and similar contributions across all network tests we conducted, we can conclude that they are, in fact:

independent of any client-to-host network topology considerations and, furthermore,

represent only a minimal portion of the overall total request duration.

This signifies that the client’s connectivity to the robotic control infrastructure represents the largest impact on the reliability and usefulness of a telerobotic system. For future improvements of the operator’s control loop, utilization of loss-tolerant unidirectional packet flows, such as via UDP, may be beneficial. However, this represents its own set of challenges to control loop operations, which warrants further investigations, such as addressing the risk of erratic behavior from the robot during unstable network conditions.

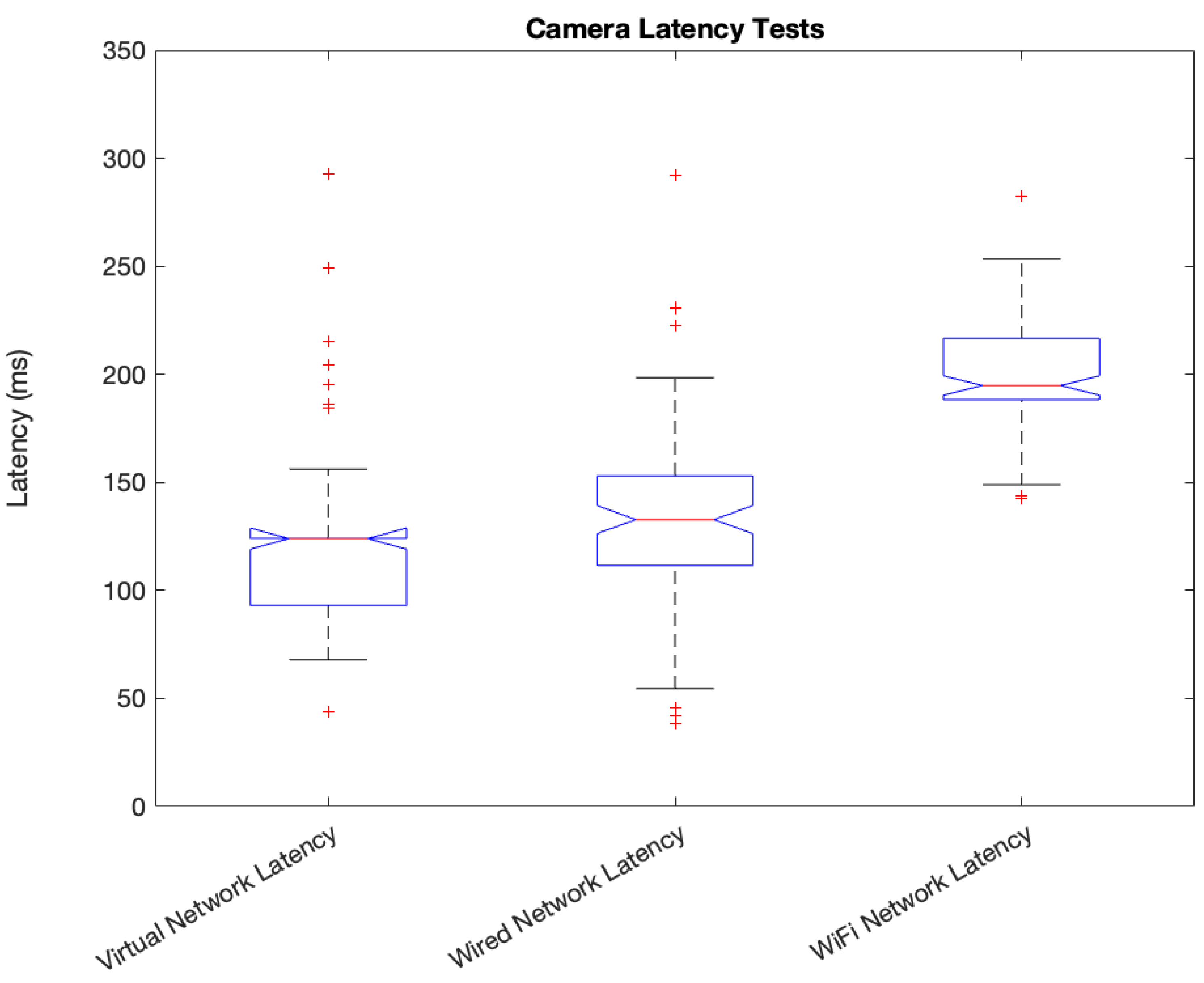

4.3. Camera’s Network Latency

A critical portion of the overall control feedback loop in our telerobotics experiments is the ability for sensor data and video feeds to be sent back from the robot environment to the operator client in order to observe the impact their control instructions have on the state of the robot. Thus, the camera latency measurements are an important consideration in these scenarios as well and are shown in

Figure 14. As outlined in

Section 3, the latency measured is the complete time for a frame to be captured, encoded, transmitted, decoded, and displayed on the client’s screen. We conducted these measurements with the help of a high-speed, high-precision timer displayed on a screen. The transmission method utilized for these tests is lossless, as TCP packet transportation is utilized. This is done to ensure the clarity of frames being captured, avoiding any artifacts that may appear with lossy transmission channels. Each test is comprised of 100 individual camera latency measurements over various network scenarios. Specifically, we studied the camera latency over three different scenarios:

A Virtual Network within the same physical host, where the camera feed is captured and encoded in a Virtual Machine and transmitted to the VM’s host computer for decoding and rendering over a Virtual Network Link,

A Wired LAN Network environment between two different physical hosts,

A Wi-Fi Network environment between a computer connected to the University’s Wi-Fi and a computer connected to the University’s Wired Network environment, including the use of the VPN, similar to the previous latency tests conducted and presented in this paper.

Given that the camera’s internal processing introduces an average of 100ms per captured frame, the latency presented for the Virtual Network communications and the Wired network environment show only a minimal difference in latency. Once the VPN was introduced during the Wi-Fi camera latency tests, the latency increased to 200ms per frame. This latency provides the largest impact to the overall control feedback loop of the entire telerobotic system. To address this, multicast approaches may be implemented for transmissions, as most applications support UDP for fast, loss-tolerant systems. For the application presented in this paper, reliable network connections would be required, so protocols that have built-in acknowledgments, like TCP, or external tools for monitoring network conditions would be required.

4.4. Comparing the achieved Total Request Durations across different Network Scenarios

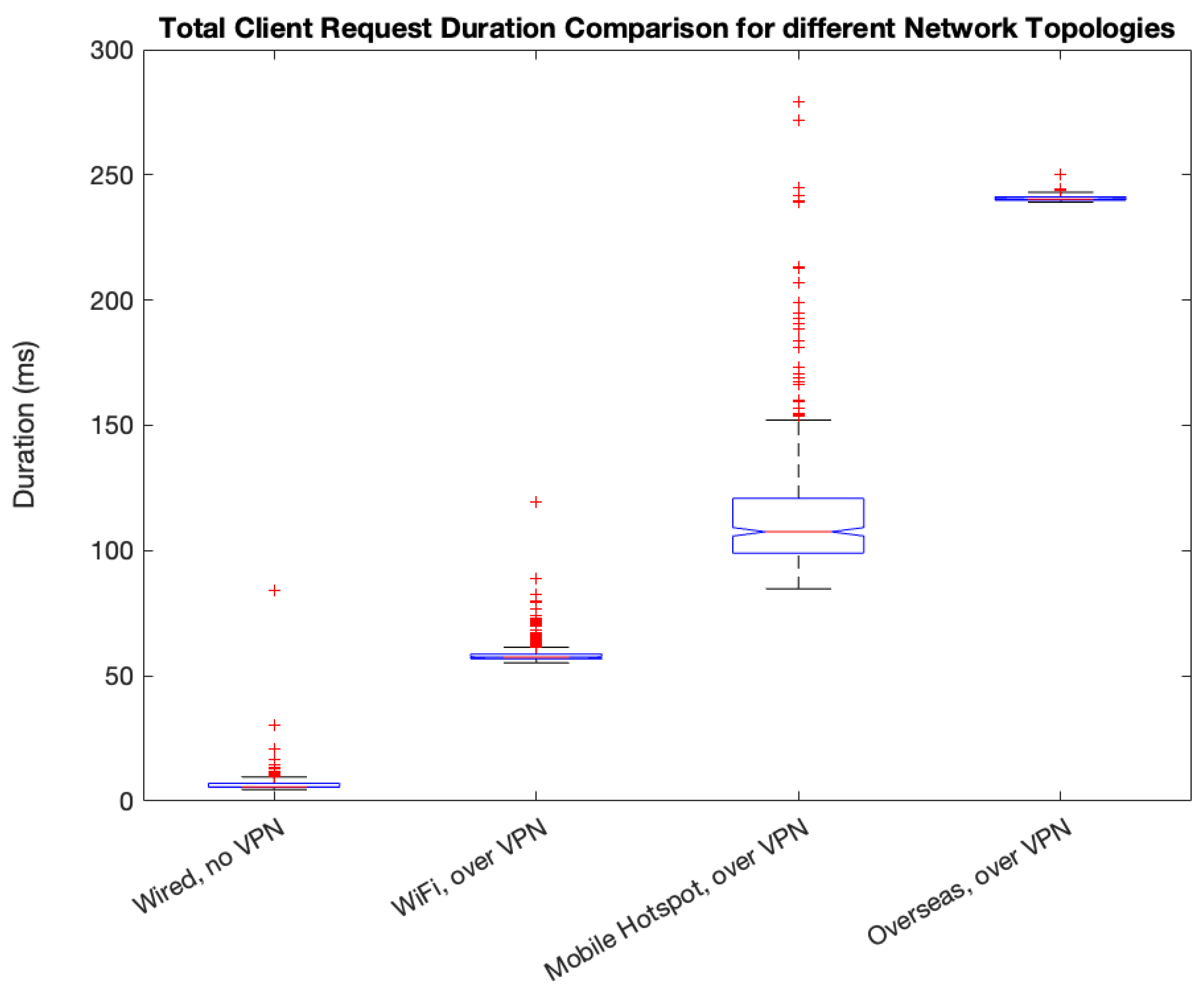

A comparison of the total request duration for each network configuration is shown in

Figure 15. From this comparison, we can see the reliability of the network has a large effect on the spread of reported latency. In the case of the mobile hotspot, outliers often introduced greater latency than the connection between Finland and the United States. This may be the result of connecting through a cellular network in a congested campus environment, but it shows a distinct disadvantage for use in populated areas without dedicated infrastructure.

In contrast, the other network scenarios we evaluated provided high-reliability connections for both the operator and robot networks. As a result, these networks had a far lower variability in their resulting latency. This did not, however, eliminate the outliers from occurring. In both the wired and WiFi tests, at least one sample took nearly 100ms in the wired network and 130ms in the WiFi network. The main difference is the latency is still at or only slightly above the control message interval of the control loop. Given these measurements, both network use cases are capable of low latency and reliable control.

However, the overseas connection tells a slightly different story than the other networks. While the latency is much higher, the stability of the network still shows reliable latency, with an average of 240.769ms. This may make control more challenging, as the robot will only move just over 4 times per second, but the reliability shows tasks such as grasping an object are feasible.

Table 5 shows combined data of the Mean, Median, Standard Deviation, and Confidence Interval for each network test. These results tell a similar story to the presented boxplot, as the standard deviation and confidence interval are far greater during hotspot testing than with networks with more reliable connections. An interesting note is that the standard deviation of the overseas connection more closely matches the wired local connection, suggesting that Wi-Fi connectivity may play a role in some latency variation.

5. Conclusion

Telerobotics is growing in popularity and deployment, as dedicated infrastructure is no longer required for applications that have some latency tolerance. A growing benefit of this approach is to perform tasks in hazardous environments without putting personnel at risk or allowing skilled individuals to perform tasks without being physically present. These applications are of interest in both civilian and military applications and can be applied to a wide variety of use cases.

This variety of use cases introduces different complex network topologies, however, which can greatly affect the reliability and latency of a telerobotic system. In this paper, we presented a latency analysis for a telerobotic system that utilizes an operator sending control information captured from a gamepad controller over a dynamically reconfigurable network topology to a remote robot platform that then is tasked with executing those movement inputs from the controller, and also a video feed being streamed back from the robotic platform to the operator for visual feedback.

Tests were then conducted with a locally wired network connection and through VPN access controlled networks with the operator connecting through Wi-Fi, a cellular hotspot, and through an overseas connection from Finland to the United States. The results presented in this paper show stable average request durations of 6.6 ms, 58.4 ms, 115.4 ms, and 240.7 ms for each of the respective network scenarios.

This research helped identify several potential latency issues for applications that require a high level of Quality of Service, or for telerobotics applications that cannot tolerate fluctuations in the connection latency or overall QoS. Additionally, these results help outline the required controls and the need for further research in order to achieve reliable near-presence telerobotic controls over commodity networks, which is the focus of our ongoing efforts.

Author Contributions

Investigation, N.B., M.B., M.H. H.S., H.T., S.M., and S.T.; writing—original draft preparation, N.B., M.B., M.H. and H.S.; writing—review and editing, N.B., M.B., M.H., H.S., H.T., and S.M.; supervision, H.S., M.H., and H.T.; project administration, H.S. and M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Niemeyer, G.; Preusche, C.; Stramigioli, S.; Lee, D. Telerobotics. Springer handbook of robotics, 2016; 1085–1108. [Google Scholar]

- Babaei, A.; Kebria, P.M.; Nahavandi, S. 5G for Low-latency Human-Robot Collaborations and Challenges and Solutions. 2022 15th International Conference on Human System Interaction (HSI), 2022, pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Botev, J.; Rodríguez Lera, F.J. Immersive robotic telepresence for remote educational scenarios. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, G.; Bridgwater, T.; Bremner, P.; Giuliani, M. Towards an immersive user interface for waypoint navigation of a mobile robot. Int. Workshop on Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality for HRI, 2020.

- LaViola Jr, J.J. A discussion of cybersickness in virtual environments. ACM Sigchi Bulletin 2000, 32, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havoutis, I.; Calinon, S. Learning from demonstration for semi-autonomous teleoperation. Autonomous Robots 2019, 43, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumeier, S.; Wintersberger, P.; Frison, A.K.; Becher, A.; Facchi, C.; Riener, A. Teleoperation: The holy grail to solve problems of automated driving? Sure, but latency matters. Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Automotive User Interfaces and Interactive Vehicular Applications, 2019, pp. 186–197.

- Pop, B.; Moldovan, C.; Florescu, F.; Popescu, I.E. Study of Latency for a Teleoperation System with Video Feedback using Wi-Fi and 4G-LTE Networks. 2022 International Conference on Communications, Information, Electronic and Energy Systems (CIEES), 2022, pp. 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Isto, P.; Heikkilä, T.; Mämmelä, A.; Uitto, M.; Seppälä, T.; Ahola, J.M. 5G based machine remote operation development utilizing digital twin. Open Engineering 2020, 10, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uitto, M.; Hoppari, M.; Heikkilä, T.; Isto, P.; Anttonen, A.; Mämmelä, A. Remote control demonstrator development in 5G test network. 2019 European Conference on Networks and Communications (EuCNC). IEEE, 2019, pp. 101–105.

- Heemeyer, F.; Boehler, Q.; Leuenberger, F.; Nelson, B.J. ROSurgical: An Open-Source Framework for Telesurgery. 2024 International Symposium on Medical Robotics (ISMR), 2024, pp. 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Stanford Artificial Intelligence, Laboratory; et al. . Robotic Operating System.

- Meshram, D.A.; Patil, D.D. 5G Enabled Tactile Internet for Tele-Robotic Surgery. Procedia Computer Science 2020, 171, 2618–2625, Third International Conference on Computing and Network Communications

(CoCoNet’19). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, P.; Hempel, M.; Sharif, H. A novel Approach to Engineering Education Laboratory Experiences through the Integration of Virtual Reality and Telerobotics. 2023 ASEE Midwest Section Conference, 2023.

- Noguera Cundar, A.; Fotouhi, R.; Ochitwa, Z.; Obaid, H. Quantifying the Effects of Network Latency for a Teleoperated Robot. Sensors (Basel) 2023, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nankaku, A.; Tokunaga, M.; Yonezawa, H.; Kanno, T.; Kawashima, K.; Hakamada, K.; Hirano, S.; Oki, E.; Mori, M.; Kinugasa, Y. Maximum acceptable communication delay for the realization of telesurgery. Maximum acceptable communication delay for the realization of telesurgery, 2022.

- Kebria, P.M.; Khosravi, A.; Nahavandi, S.; Shi, P.; Alizadehsani, R. Robust Adaptive Control Scheme for Teleoperation Systems With Delay and Uncertainties. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics 2020, 50, 3243–3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Ai, Q.; Shi, T.; Gao, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zhao, W.; Jiang, C.; Liu, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Gao, F.; Ma, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, X. Influence of network latency and bandwidth on robot-assisted laparoscopic telesurgery: A pre-clinical experiment. Chin Med J (Engl) 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petershans, J.; Herbst, J.; Rueb, M.; Mittag, E.; Schotten, H.D. Robotic Teleoperation: A Real-World Test Environment for 6G Communications. Mobilkommunikation; 28. ITG-Fachtagung, 2024, pp. 106–111.

- George, J.M.; Feiler, J.; Hoffmann, S.; Diermeyer, F. Sensor and Actuator Latency during Teleoperation of Automated Vehicles. 2020 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), 2020, pp. 760–766. [CrossRef]

- Rakita, D.; Mutlu, B.; Gleicher, M. Effects of Onset Latency and Robot Speed Delays on Mimicry-Control Teleoperation. 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, 2020.

- Baklouti, S.; Gallot, G.; Viaud, J.; Subrin, K. On the Improvement of ROS-Based Control for Teleoperated Yaskawa Robots. Applied Sciences 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Sarma, H.K.D.; Biradar, S.R. (Eds.) "IoT and Cloud Computing-Based Healthcare Information Systems"; Biomedical Engineering, Apple Academic Press: Oakville, MO, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Ahn, J.; Park, J. Stereoscopic low-latency vision system via ethernet network for Humanoid Teleoperation. 2022 19th International Conference on Ubiquitous Robots (UR), 2022, pp. 313–317. [CrossRef]

- Black, D.G.; Andjelic, D.; Salcudean, S.E. Evaluation of Communication and Human Response Latency for (Human) Teleoperation. IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics 2024, 6, 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orosco, R.K.; Lurie, B.; Matsuzaki, T.; Funk, E.K.; Divi, V.; Holsinger, F.C.; Hong, S.; Richter, F.; Das, N.; Yip, M. Compensatory motion scaling for time-delayed robotic surgery. Surgical Endoscopy 2021, 35, 2613–2618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, W.; Fan, M.; Zeng, C.; Liu, Y.; He, D.; Zhang, Q. Telerobotic Spinal Surgery Based on 5G Network: The First 12 Cases. Neurospine 2020, 17, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George Moustris, Costas Tzafestas, K.K. A long distance telesurgical demonstration on robotic surgery phantoms over 5G. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery, 2023, Vol. 18, pp. 1577–1587. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, L.A.; Le, K.D.; Harman, T.L. Kinematic Redundancy Resolution for Baxter Robot. 2021 7th International Conference on Automation, Robotics and Applications (ICARA), 2021, pp. 6–9. [CrossRef]

- McMahon, I. "Rethink Robotics Library". https://github.com/RethinkRobotics/baxter, 2013.

- Zeth. "Cross-platform Python support for keyboards, mice and gamepads". https://github.com/zeth/inputs, 2018.

- Open-CV. "Automated CI toolchain to produce precompiled opencv-python, opencv-python-headless, opencv-contrib-python and opencv-contrib-python-headless packages". https://github.com/opencv/opencv-python, 2000.

Figure 1.

Photo of Baxter Robot.

Figure 1.

Photo of Baxter Robot.

Figure 2.

Timing Diagram and request/response flow between Client, Host and Robotic Platform

Figure 2.

Timing Diagram and request/response flow between Client, Host and Robotic Platform

Figure 3.

Network Diagram of Wired Non-VPN University Network Connection Scenario.

Figure 3.

Network Diagram of Wired Non-VPN University Network Connection Scenario.

Figure 4.

Network Diagram of Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 4.

Network Diagram of Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 5.

Network Diagram of Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 5.

Network Diagram of Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 6.

Network Diagram of Overseas Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 6.

Network Diagram of Overseas Network Connection Scenario including VPN.

Figure 7.

Box Plot of Latency Over University Network

Figure 7.

Box Plot of Latency Over University Network

Figure 8.

Box Plot of Latency for the Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Figure 8.

Box Plot of Latency for the Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Figure 9.

Box Plot of Latency from the Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Figure 9.

Box Plot of Latency from the Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Figure 10.

Map showing the endpoint locations of our overseas tests between UNL and VTT

Figure 10.

Map showing the endpoint locations of our overseas tests between UNL and VTT

Figure 11.

Box Plot of Latency from the Transatlantic Network Connection Scenario and Edge VPN

Figure 11.

Box Plot of Latency from the Transatlantic Network Connection Scenario and Edge VPN

Figure 12.

IK Solver Latency Comparison for all tested Network Scenarios

Figure 12.

IK Solver Latency Comparison for all tested Network Scenarios

Figure 13.

Move Request Latency Comparison

Figure 13.

Move Request Latency Comparison

Figure 14.

Box Plot of Camera Feed Latency across different Network Scenarios

Figure 14.

Box Plot of Camera Feed Latency across different Network Scenarios

Figure 15.

Box Plot Comparison of the Client’s Request Duration across different Network Scenarios

Figure 15.

Box Plot Comparison of the Client’s Request Duration across different Network Scenarios

Table 1.

Round Trip Time in the Wired Non-VPN University Network Connection Scenario

Table 1.

Round Trip Time in the Wired Non-VPN University Network Connection Scenario

| Round Trip Time (ms) |

| Mean |

6.617 |

| Median |

5.667 |

| Standard Dev. |

1.357 |

| Confidence Int. |

0.397 |

Table 2.

Round Trip Time of the Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Table 2.

Round Trip Time of the Lab WiFi-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

| Round Trip Time (ms) |

| Mean |

58.459 |

| Median |

57.455 |

| Standard Dev. |

3.629 |

| Confidence Int. |

0.223 |

Table 3.

Round Trip Time of the Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

Table 3.

Round Trip Time of the Mobile Hotspot-to-University Network Connection Scenario including VPN

| Round Trip Time (ms) |

| Mean |

115.381 |

| Median |

107.515 |

| Standard Dev. |

30.577 |

| Confidence Int. |

2.960 |

Table 4.

Round Trip Time of the Transatlantic Network Connection Scenario and Edge VPN

Table 4.

Round Trip Time of the Transatlantic Network Connection Scenario and Edge VPN

| Round Trip Time (ms) |

| Mean |

240.769 |

| Median |

240.317 |

| Standard Dev. |

1.714 |

| Confidence Int. |

0.857 |

Table 5.

Results of Latency across different Network Scenarios

Table 5.

Results of Latency across different Network Scenarios

| Results (ms) |

Wired |

Wi-Fi |

Hot-Spot |

Overseas |

| Mean |

6.617 |

58.459 |

115.381 |

240.769 |

| Median |

5.667 |

57.455 |

107.515 |

240.317 |

| Standard Dev. |

1.357 |

3.629 |

30.577 |

1.714 |

| Confidence Int. |

0.397 |

0.223 |

2.960 |

0.857 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).