1. Introduction

Lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)] is a lipoprotein particle structurally similar to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) with an additional apolipoprotein(a) [apo(a)] covalently attached to apolipoprotein B. Its serum concentration is primarily determined by genetics and is not significantly affected by dietary or lifestyle changes (1). Lp(a) is prone to oxidative modifications and possesses proinflammatory and proatherogenic properties, and due to its similarity to plasminogen, it may also exert potential prothrombotic effects (2). It is a well-recognized causal risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9]. Numerous epidemiologic and Mendelian studies have confirmed its association with incident cardiovascular (CV) events [

3,

4,

5,

6,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. However, its role in patients with established ASCVD remains controversial, with varying findings in previous reports [

6,

16,

17,

18,

19]. Extensive analysis of Lp(a) data from the United Kingdom (UK) Biobank suggested that the impact of Lp(a) on CV events is attenuated in secondary compared with primary prevention settings [

6]. To further investigate Lp(a) as a risk factor for recurrent acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and mortality, we conducted a retrospective analysis of data from our clinical routine.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

Using the Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) diagnostic codes, we identified all patients admitted for AMI to the Clinical Department of Cardiology and Angiology at the University Clinical Centre Maribor, Slovenia, between 2000 and 2022 who had available Lp(a) results at admission. Patients treated with monoclonal antibodies against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 and inclisiran were excluded because of known interference with Lp(a) levels. Most Lp(a) values were collected between 2005 and 2008 when Lp(a) was part of the routine laboratory protocol at admission. Outside this period, Lp(a) was occasionally measured if requested by the attending physician for additional CV risk assessment. Finally, a total of 2248 patients were included in the study. Patients were treated in accordance with the guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology [

20].

The study protocol was approved by the institution's ethics committee (UKC-MB-KME-8/23; February 23, 2023). The retrospective data analysis was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2. Methods

In all patients, Lp(a) samples were collected within 24 hours of admission for incident AMI and analyzed on the same day. Quantitative serum determination of Lp(a) was performed using a fully automated particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assay (Siemens Prospec R, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Erlangen, Germany). Lp(a) results are expressed in mass units (mg/dL). Fasting triglycerides were measured using the enzymatic method, and total serum cholesterol was determined by the cholesterol esterase enzymatic assay. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) were measured using the homogeneous direct method (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Erlangen, Germany).

All medical reports concerning recurrent AMI, as well as the time and cause of death, were retrospectively collected from our hospital database and regional referring hospitals until December 31, 2022. The mean observation time was 9.5 years. For all patients who died during the observational period, the time of death and the ICD-10 codes defining the principal cause of death were provided by the National Institute of Health, Slovenia.

A recurrent AMI was defined as either a repeat hospitalization with principal ICD-10 discharge codes I21/I22, or when I21/I22 ICD-10 codes were identified as the principal cause of death in the National Mortality Database (National Institute of Public Health, Slovenia). CV death was defined by I00-I99 (cardiovascular disease) ICD-10 codes identified as the principal cause of death in the National Mortality Database (National Institute of Health, Slovenia).

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Normally distributed continuous variables are presented as the means ± standard deviations (SDs), whereas nonnormally distributed variables are presented as the medians and corresponding interquartile ranges (IQRs).

Initially, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to analyze the association of Lp(a) levels as a continuous variable with CV events (recurrent AMI, CV death, all-cause death). The model was adjusted for age, sex, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, statin use, and diabetes mellitus.

Second, a multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to analyze the association of Lp(a) as an interval variable with CV events (recurrent AMI, CV death, all-cause death). Patients were stratified into three groups based on their Lp(a) level: ≤50 mg/dL, 50–90 mg/dL, and >90 mg/dL. These cutoff values were derived from previous studies and recommendations (2). The model was adjusted for age, sex, LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, statin use, and diabetes mellitus.

Finally, to examine the effect of age and sex on the relationship between Lp(a) and recurrent AMI/mortality, all patients were further stratified based on sex and age into four subgroups with an age threshold of 65 years (men/women aged ≤65 years and >65 years). For each age and sex subgroup, a multivariable-adjusted Cox regression analysis was performed to evaluate the impact of Lp(a) as an interval variable on recurrent AMI, CV death, and all-cause death. The model was adjusted for LDL-C, HDL-C, triglycerides, statin use, and diabetes mellitus.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28 (IBM, Armonk, New York, NY, USA). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 2248 patients, with a mean age of 64.7±12.2 years (31.5% women), were included in the study. At the time of inclusion, 24.8% of patients had diabetes mellitus, 9.1% were insulin-dependent, and 10.8% were treated with oral antidiabetic drugs. A statin was prescribed in 82.0% of patients, with 23.5% receiving high-intensity statin therapy (rosuvastatin 20–40 mg, atorvastatin 40–80 mg). Beta-blockers were used in 79.9%, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in 75.5%, and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists in 8.1% of patients. During the mean follow-up of 9.5 years, recurrent AMI occurred in 453 patients (20.2%), CV death in 650 (28.9%), and all-cause death in 1199 (53.3%) patients. The mean time to recurrent AMI was 58.5±56.5 months, to CV death was 74.6±58.8 months, and to all-cause death was 82.5±60.3 months. The median Lp(a) level in the cohort was 17.0 mg/dL, with an IQR of 7.0–47.0 mg/dL. The mean LDL-C level was 3.1±1.1 mmol/L, the mean HDL level was 1.1±0.3 mmol/L, and the mean triglyceride level was 1.9±1.2 mmol/L. The mean creatinine level was 91.9±53.3 mcmol/L. The basic characteristics of the included patients are summarized in

Table 1.

In the multivariable Cox regression model using Lp(a) as a continuous variable, no significant associations were found between Lp(a) and recurrent AMI (HR 1.00,

p=0.171), CV death (HR 1.00,

p=0.332), or all-cause death (1.00,

p=0.062) (Suppl.

Table S1).

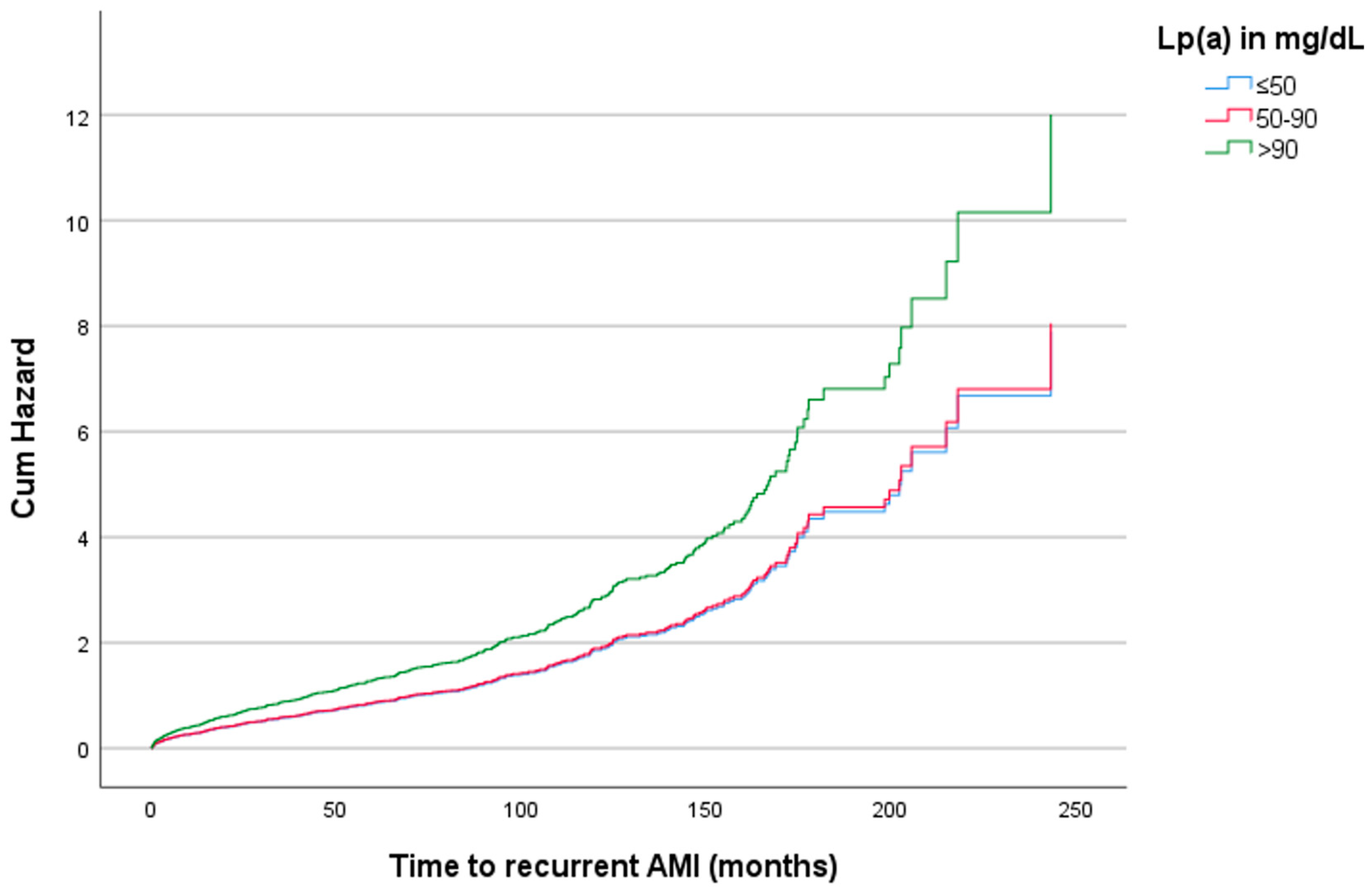

Patients were further stratified into three groups based on their Lp(a) level (≤50, 51–90, >90 mg/dL). The number of included patients and the sex distribution within each Lp(a) group are summarized in Suppl.

Table S2. T

he multivariable-adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of recurrent AMI were 1.01 (p=0.921, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.768–1.340) for levels between

51–90 mg/dL and 1.51 (p=0.013, 95% CI: 1.093–2.094) for levels >90 mg/dL, compared with levels ≤

50 mg/dL (Table 2, Figure 1). For CV mortality, the HRs were 1.13 (

p=0.300, 95% CI: 0.899–1.412) for levels between 51–90 mg/dL and 1.14 (

p=0.348, 95% CI: 0.869–1.487) for levels >90 mg/dL, compared with levels ≤50 mg/dL. For all-cause mortality, the HRs were 1.09 (

p=0.310, 95% CI: 0.923–1.285) for levels between 51–90 mg/dL and 1.20 (

p=0.090, 95% CI: 0.972–1.477) for levels >90 mg/dL, compared with levels ≤50 mg/dL

(Table 2).

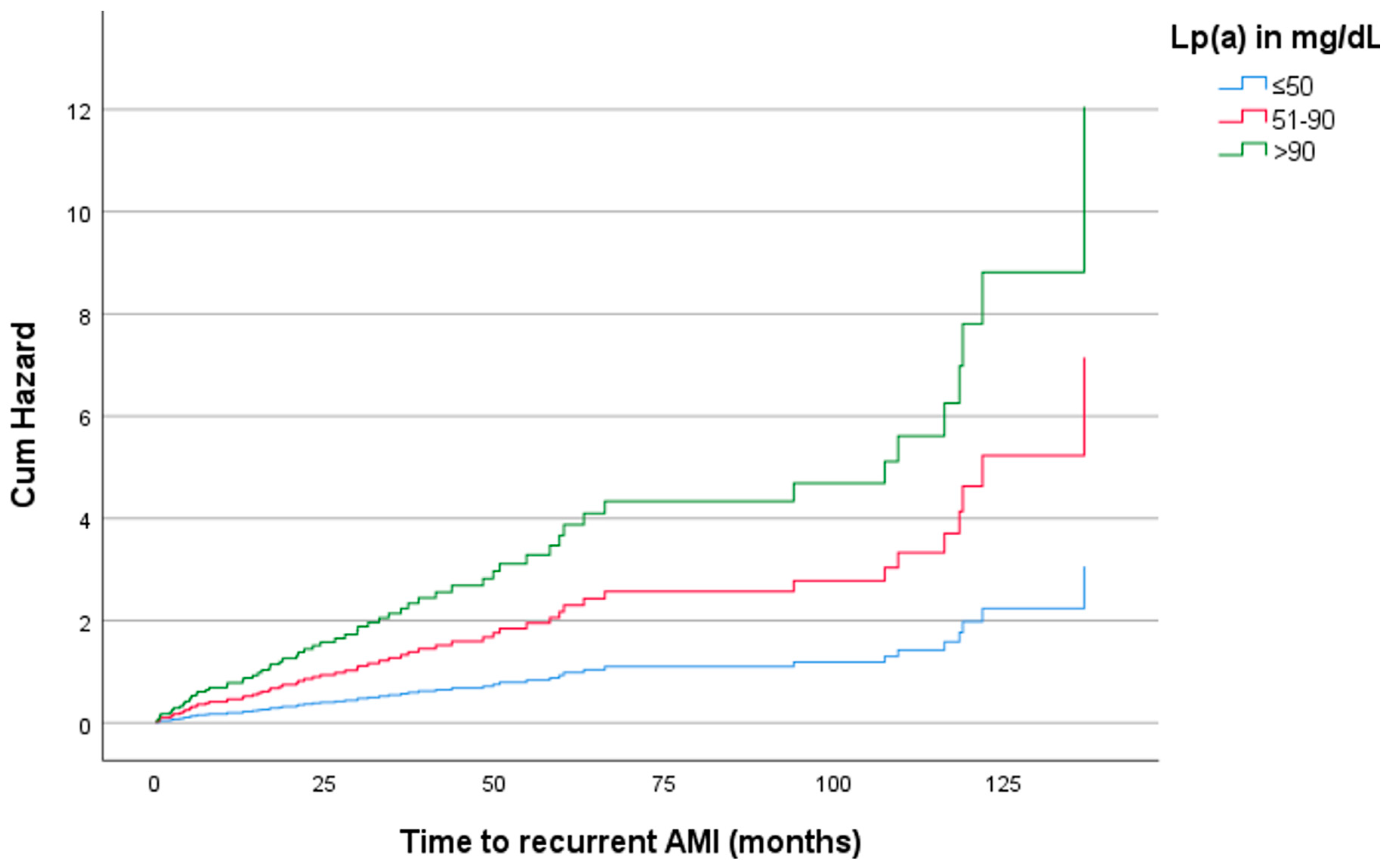

After stratification by sex and age, the positive association of Lp(a) with recurrent AMI remained statistically significant only for women aged >65 years, with a multivariable-adjusted HR of 2.34 (p=0.013, 95% CI: 1.198–4.563) for levels between 51–90 mg/dL and 3.94 (p<0.001, 95% CI: 1.760–8.833) for levels >90 mg/dL, compared with levels ≤50 mg/dL (

Table 3,

Figure 2). No significant associations of Lp(a) with CV or all-cause mortality were found in any age or sex subgroup (Suppl.

Tables S3 and S4).

4. Discussion

In our study, Lp(a) was associated with a significantly greater risk of recurrent AMI only in patients with extreme Lp(a) values beyond 90 mg/dL. We found no significant associations of Lp(a) with CV or all-cause mortality. After stratification by age and sex, the increased risk of recurrent AMI was restricted to women aged >65 years with Lp(a) levels >50 mg/dL.

Most large previous Lp(a) trials included patients in the primary prevention setting, confirming the causal association of Lp(a) with the first CV event [

2,

3,

4,

5,

21,

23]. However, the data concerning the impact of Lp(a) on recurrent CV events in patients with established ASCVD are more controversial [

6,

17,

18,

24]. In 1996, the first study comparing the role of Lp(a) in primary versus secondary prevention confirmed the association of Lp(a) only with the first CV event [

25]. In 2014, the first extensive meta-analysis of secondary prevention trials revealed heterogeneous results, showing a significant association between Lp(a) and the second CV event only in patients with LDL-C levels greater than 3.7 mmol/L [

17]. Similar to our findings, a study including STEMI patients found the association of Lp(a) with recurrent events only in patients with an extreme Lp(a) level above the

95th percentile (≥135 mg/dL) [

26]

. Furthermore, in a very recently published study of 32537

ASCVD patients, Lp(a) levels >150 nmol/L vs. <65 nmol/L were associated with an increased risk of recurrent CV events, particularly nonfatal AMI and coronary revascularizations, which was most evident in the first year following the index event [

16]. Conversely, in the subanalysis of the dal-Outcome randomized dalcetrapib trial, Lp(a) was not significantly associated with recurrent adverse CV outcomes [

18]

. In the analysis of the large UK Biobank data encompassing nearly half a million individuals, Lp(a)-

associated CV risk was attenuated among those with preexisting ASCVD compared to those without (5% versus 10% higher risk conferred by a 50 nmol/L increase in Lp(a) level) [

6,

19]

. This suggests that in very high-risk ASCVD patients, the relative risk contribution of Lp(a) may be outweighed by other more decisive factors. This is an important consideration in light of emerging Lp(a)-lowering drugs, underscoring the need for further research to identify subgroups that might benefit the most.

The differential impact of age and sex on Lp(a)-associated morbidity and mortality in the general population was recently evaluated using the data from the large Copenhagen general population cohort [

27]. This study demonstrated an increase in Lp(a) levels with increasing age, with a modest additional increase in women at menopause, which is consistent with previous reports [

2,

28,

29]. However, when individuals with Lp(a) levels >40 mg/dL were compared to those with levels <10 mg/dL, the increase in the risk of incident AMI was similar in both sexes [

27]. The same study reported a similar increase in Lp(a)-associated CV risk in those below and above 50 years of age [

27]. In a large pooled multiethnic sample from five landmark primary prevention cohorts, the Lp(a)-associated risk of long-term CV events was similar across age, sex, and race/ethnicity [

30]. On the other hand, the role of sex and age in patients with prevalent ASCVD is much less clear, and the data are limited. In our study, we found a strong association between Lp(a) levels and recurrent AMI only in women aged >65 years, and the risk increased beyond the Lp(a) level of 50 mg/dL. Similar to our findings, Bigazzi et al. highlighted the differential impact of sex in patients with prevalent coronary artery disease, noting a greater risk of future coronary revascularizations in women with elevated Lp(a) than in men [

31]. In contrast, a recent study of 12064 ASCVD patients following a percutaneous coronary intervention found no sex-related differences in the association between Lp(a) and future CV events [

32].

The association of Lp(a) with CV and all-cause mortality is another unresolved issue. While some studies aligned with our findings and reported no association, others identified Lp(a) as a risk factor for increased CV or all-cause mortality in the general population [

33,

34,

35,

36]. In 2009, the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration meta-analysis demonstrated that one standard deviation higher Lp(a) was associated with significantly higher CV mortality (HR 1.14, 95% CI: 1.07–1.22), whereas all-cause mortality was not analyzed [

3]. In a large cohort of the Danish general population, a 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) increase in Lp(a) level was associated with an HR of 1.16 for CV mortality (95% CI: 1.09–1.23) and 1.05 (95% CI: 1.01–1.09) for all-cause mortality, which was further confirmed by genetic associations on the basis of the number of

LPA kringle 4 type-2 repeats and the

LPA rs10455872 genotype [

37]. In patients with prevalent coronary heart disease, a large genetic association study revealed no associations between Lp(a) levels/corresponding genetic variants and long-term mortality, which is consistent with our findings [

38]. Intriguingly, a Japanese general population study of 10413 individuals showed paradoxically higher all-cause mortality in patients with low (<8 mg/dL) versus intermediate-high Lp(a) (≥8 mg/dL) (HR 1.43, 95% CI: 1.21–1.68) [

39]. This could at least partly be explained by the higher incidence of cancer-related deaths observed in the group with low Lp(a) levels in their study, while the potential antineoplastic properties of Lp(a) are an area of research [

39]. Furthermore, increased Lp(a) might protect against major bleeding due to its structural homology with plasminogen and potential antifibrinolytic properties. This hypothesis was recently tested by Langsted A et al. in Danish general population study participants, demonstrating that one standard deviation increase in Lp(a) (31 mg/dL) was associated with a decreased hazard for major bleeding in the brain and airways (HR 0.95, 95%: CI 0.91–1.00), which was further confirmed by a genetic association study [

40].

Our results should be interpreted in light of certain limitations. First, the analysis was retrospective and relied on the ICD-10 diagnoses reported at hospital discharge by the discharging physician. The retrospective approach inherently limits our ability to control for unrecorded variables. The absence of genetic data restricts our ability to establish causality between Lp(a) levels and the outcomes observed in this study. Additionally, Lp(a) measurements were conducted only on a limited number of patients admitted for AMI during the study period, which may introduce potential selection bias.

The major strengths of our study are the inclusion of a homogeneous Caucasian (Slovenian) population and the consistency in Lp(a) measurements on the day of blood sampling, thereby avoiding potential measurement errors due to delayed sample analysis [

41]. Moreover, all the measurements were conducted using the same laboratory method (nephelometry) and were performed with Siemens laboratory equipment.

5. Conclusions

Lp(a) is a well-established risk factor for incident CV events, particularly AMI. However, its role in patients with established ASCVD is less clear. In our study, we found a significant association between Lp(a) levels exceeding 90 mg/dL and recurrent AMI, while no associations were observed between Lp(a) levels and CV or all-cause mortality. The association with recurrent AMI was most pronounced in women aged >65 years.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S1: Association of Lp(a) as a continuous variable (in mg/dL) and other covariates with recurrent AMI and mortality; Table S2. Number and sex distribution of patients stratified by Lp(a) level in three groups; Table S3: Association of Lp(a) as an interval variable with CV mortality stratified by age and sex; Table S4: Association of Lp(a) as an interval variable with all-cause mortality stratified by age and sex.

Author Contributions

DŠ: Conceptualization; Resources; Data curation; Methodology; Writing - original draft. VK: Conceptualization; Writing - review & editing. PK: Data curation; Formal analysis; Writing - review & editing. BŽ: Data curation; Formal analysis. TZ: Data curation; Writing - review & editing. FV: Data curation; Writing - review & editing. AS: Conceptualization; Writing - review & editing. FHN: Conceptualization; Writing - review & editing.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University Medical Centre Maribor, Slovenia (UKC-MB-KME-8/23; Feb 23, 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon a reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to ethical concerns.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institute of Public Health of Slovenia for providing the mortality data used in this study. We are also grateful to the referring regional hospitals (General Hospital Slovenj Gradec, General Hospital Murska Sobota, and General Hospital Celje) for providing data regarding hospital readmissions of patients in our study.

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest regarding the submitted study. Outside the submitted work, David Šuran and Franjo Naji report talks or consultancies sponsored by Novartis, Amgen, Swixx BioPharma, Sanofi, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Servier, and Krka.

List of abbreviations

| AMI |

acute myocardial infarction |

| ASCVD |

atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease |

| CV |

cardiovascular |

| HDL-C |

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, |

| ICD-10 |

Tenth Revision of the International Classification of Diseases diagnostic codes |

| IQR |

interquartile range |

| LDL-C |

low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| Lp(a) |

lipoprotein(a) |

| NSTEMI |

myocardial infarction without ST-segment elevation |

| SD |

standard deviation |

| STEMI |

myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation |

References

- Reyes-Soffer, G.; Ginsberg, H.N.; Berglund, L.; Duell, P.B.; Heffron, S.P.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Lloyd-Jones, D.M.; Marcovina, S.M.; Yeang, C.; Koschinsky, M.L.; et al. Lipoprotein(a): A Genetically Determined, Causal, and Prevalent Risk Factor for Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2022, 42, e48–e60. [CrossRef]

- Kronenberg, F.; Mora, S.; Stroes, E.S.G.; Ference, B.A.; Arsenault, B.J.; Berglund, L.; Dweck, M.R.; Koschinsky, M.; Lambert, G.; Mach, F.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) in Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Aortic Stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Statement. Eur. Heart J. 2022, 43, 3925–3946. [CrossRef]

- Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration; Erqou, S.; Kaptoge, S.; Perry, P.L.; Di Angelantonio, E.; Thompson, A.; White, I.R.; Marcovina, S.M.; Collins, R.; Thompson, S.G.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Concentration and the Risk of Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Nonvascular Mortality. JAMA 2009, 302, 412–423. [CrossRef]

- Kamstrup, P.R.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Steffensen, R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Genetically Elevated Lipoprotein(a) and Increased Risk of Myocardial Infarction. JAMA 2009, 301, 2331–2339. [CrossRef]

- Kamstrup, P.R.; Benn, M.; Tybjaerg-Hansen, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Extreme Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Risk of Myocardial Infarction in the General Population: The Copenhagen City Heart Study. Circulation 2008, 117, 176–184. [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.P.; Wang (汪敏先), M.; Pirruccello, J.P.; Ellinor, P.T.; Ng, K.; Kathiresan, S.; Khera, A.V. Lp(a) (Lipoprotein[a]) Concentrations and Incident Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease: New Insights From a Large National Biobank. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 465–474. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.P.; Jacobson, T.A.; Jones, P.H.; Koschinsky, M.L.; McNeal, C.J.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Orringer, C.E. Use of Lipoprotein(a) in Clinical Practice: A Biomarker Whose Time Has Come. A Scientific Statement from the National Lipid Association. J. Clin. Lipidol. 2019, 13, 374–392. [CrossRef]

- Nissen, S.E.; Wolski, K.; Cho, L.; Nicholls, S.J.; Kastelein, J.; Leitersdorf, E.; Landmesser, U.; Blaha, M.; Lincoff, A.M.; Morishita, R.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Levels in a Global Population with Established Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. Open Heart 2022, 9, e002060. [CrossRef]

- Mach, F.; Baigent, C.; Catapano, A.L.; Koskinas, K.C.; Casula, M.; Badimon, L.; Chapman, M.J.; De Backer, G.G.; Delgado, V.; Ference, B.A.; et al. 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidaemias: Lipid Modification to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk: The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 111–188. [CrossRef]

- Waldeyer, C.; Makarova, N.; Zeller, T.; Schnabel, R.B.; Brunner, F.J.; Jørgensen, T.; Linneberg, A.; Niiranen, T.; Salomaa, V.; Jousilahti, P.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in the European Population: Results from the BiomarCaRE Consortium. Eur. Heart J. 2017, 38, 2490–2498. [CrossRef]

- Arora, P.; Kalra, R.; Callas, P.W.; Alexander, K.S.; Zakai, N.A.; Wadley, V.; Arora, G.; Kissela, B.M.; Judd, S.E.; Cushman, M. Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Ischemic Stroke in the REGARDS Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 810–818. [CrossRef]

- Gurdasani, D.; Sjouke, B.; Tsimikas, S.; Hovingh, G.K.; Luben, R.N.; Wainwright, N.W.J.; Pomilla, C.; Wareham, N.J.; Khaw, K.-T.; Boekholdt, S.M.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) and Risk of Coronary, Cerebrovascular, and Peripheral Artery Disease: The EPIC-Norfolk Prospective Population Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2012, 32, 3058–3065. [CrossRef]

- Paré, G.; Çaku, A.; McQueen, M.; Anand, S.S.; Enas, E.; Clarke, R.; Boffa, M.B.; Koschinsky, M.; Wang, X.; Yusuf, S.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Levels and the Risk of Myocardial Infarction Among 7 Ethnic Groups. Circulation 2019, 139, 1472–1482. [CrossRef]

- Šuran, D.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Završnik, J.; Kokol, P.; Sinkovič, A.; Kanič, V.; Kokol, M.; Naji, F.; Završnik, T. Lipoprotein(a) in Cardiovascular Diseases: Insight From a Bibliometric Study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 923797. [CrossRef]

- Virani, S.S.; Brautbar, A.; Davis, B.C.; Nambi, V.; Hoogeveen, R.C.; Sharrett, A.R.; Coresh, J.; Mosley, T.H.; Morrisett, J.D.; Catellier, D.J.; et al. Associations between Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Black and White Subjects: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. Circulation 2012, 125, 241–249. [CrossRef]

- Welsh, P.; Al Zabiby, A.; Byrne, H.; Benbow, H.R.; Itani, T.; Farries, G.; Costa-Scharplatz, M.; Ferber, P.; Martin, L.; Brown, R.; et al. Elevated Lipoprotein(a) Increases Risk of Subsequent Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE) and Coronary Revascularisation in Incident ASCVD Patients: A Cohort Study from the UK Biobank. Atherosclerosis 2024, 389, 117437. [CrossRef]

- O’Donoghue, M.L.; Morrow, D.A.; Tsimikas, S.; Sloan, S.; Ren, A.F.; Hoffman, E.B.; Desai, N.R.; Solomon, S.D.; Domanski, M.; Arai, K.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) for Risk Assessment in Patients with Established Coronary Artery Disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2014, 63, 520–527. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Ballantyne, C.M.; Barter, P.J.; Kallend, D.; Leiter, L.A.; Leitersdorf, E.; McMurray, J.J.V.; Nicholls, S.J.; Olsson, A.G.; Shah, P.K.; et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) With Risk of Recurrent Ischemic Events Following Acute Coronary Syndrome: Analysis of the Dal-Outcomes Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2018, 3, 164–168. [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, J.C.; Clarke, R.; Watkins, H. Lp(a) (Lipoprotein[a]), an Exemplar for Precision Medicine. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2021, 41, 475–477. [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.A.; Rossello, X.; Coughlan, J.J.; Barbato, E.; Berry, C.; Chieffo, A.; Claeys, M.J.; Dan, G.-A.; Dweck, M.R.; Galbraith, M.; et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the Management of Acute Coronary Syndromes. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 3720–3826. [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.; Sun, W.; Agarwala, A.; Virani, S.S.; Nambi, V.; Coresh, J.; Selvin, E.; Boerwinkle, E.; Jones, P.H.; Ballantyne, C.M.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease Events in Individuals with Diabetes Mellitus or Prediabetes: The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Atherosclerosis 2019, 282, 52–56. [CrossRef]

- Šuran, D.; Završnik, T.; Kokol, P.; Kokol, M.; Sinkovič, A.; Naji, F.; Završnik, J.; Blažun Vošner, H.; Kanič, V. Lipoprotein(a) As a Risk Factor in a Cohort of Hospitalised Cardiovascular Patients: A Retrospective Clinical Routine Data Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3220. [CrossRef]

- Langsted, A.; Nordestgaard, B.G.; Kamstrup, P.R. Low Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Risk of Disease in a Large, Contemporary, General Population Study. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 1147–1156. [CrossRef]

- Galasso, G.; De Angelis, E.; Silverio, A.; Di Maio, M.; Cancro, F.P.; Esposito, L.; Bellino, M.; Scudiero, F.; Damato, A.; Parodi, G.; et al. Predictors of Recurrent Ischemic Events in Patients With ST-Segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021, 159, 44–51. [CrossRef]

- Kinlay, S.; Dobson, A.J.; Heller, R.F.; McELDUFF, P.; Alexander, H.; Dickeson, J. Risk of Primary and Recurrent Acute Myocardial Infarction From Lipoprotein(a) in Men and Women1. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1996, 28, 870–875. [CrossRef]

- Miñana, G.; Gil-Cayuela, C.; Bodi, V.; de la Espriella, R.; Valero, E.; Mollar, A.; Marco, M.; García-Ballester, T.; Zorio, B.; Fernández-Cisnal, A.; et al. Lipoprotein(a) and Long-Term Recurrent Infarction after an Episode of ST-Segment Elevation Acute Myocardial Infarction. Coron. Artery Dis. 2020, 31, 378. [CrossRef]

- Simony, S.B.; Mortensen, M.B.; Langsted, A.; Afzal, S.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Sex Differences of Lipoprotein(a) Levels and Associated Risk of Morbidity and Mortality by Age: The Copenhagen General Population Study. Atherosclerosis 2022, 355, 76–82. [CrossRef]

- Derby, C.A.; Crawford, S.L.; Pasternak, R.C.; Sowers, M.; Sternfeld, B.; Matthews, K.A. Lipid Changes during the Menopause Transition in Relation to Age and Weight: The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009, 169, 1352–1361. [CrossRef]

- Suk Danik, J.; Rifai, N.; Buring, J.E.; Ridker, P.M. Lipoprotein(a), Hormone Replacement Therapy, and Risk of Future Cardiovascular Events. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 124–131. [CrossRef]

- Wong, N.D.; Fan, W.; Hu, X.; Ballantyne, C.; Hoodgeveen, R.C.; Tsai, M.Y.; Browne, A.; Budoff, M.J. Lipoprotein(a) and Long-Term Cardiovascular Risk in a Multi-Ethnic Pooled Prospective Cohort. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 1511–1525. [CrossRef]

- Bigazzi, F.; Minichilli, F.; Sbrana, F.; Pino, B.D.; Corsini, A.; Watts, G.F.; Sirtori, C.R.; Ruscica, M.; Sampietro, T. Gender Difference in Lipoprotein(a) Concentration as a Predictor of Coronary Revascularization in Patients with Known Coronary Artery Disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA - Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2021, 1866, 158869. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, Y.-H.; Ahn, J.-M.; Kang, D.-Y.; Lee, P.H.; Kang, S.-J.; Park, D.-W.; Lee, S.-W.; Kim, Y.-H.; Han, K.H.; Lee, C.W.; et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) With Recurrent Ischemic Events Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2021, 14, 2059–2068. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Li, H.-L.; Bei, W.-J.; Guo, X.-S.; Wang, K.; Yi, S.-X.; Luo, D.-M.; Li, X.; Chen, S.-Q.; Ran, P.; et al. Association of Lipoprotein(a) with Long-Term Mortality Following Coronary Angiography or Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Clin. Cardiol. 2017, 40, 674–678. [CrossRef]

- Konishi, H.; Miyauchi, K.; Shitara, J.; Endo, H.; Wada, H.; Doi, S.; Naito, R.; Tsuboi, S.; Ogita, M.; Dohi, T.; et al. Impact of Lipoprotein(a) on Long-Term Outcomes in Patients With Diabetes Mellitus Who Underwent Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. Am. J. Cardiol. 2016, 118, 1781–1785. [CrossRef]

- Ariyo, A.A.; Thach, C.; Tracy, R. Lp(a) Lipoprotein, Vascular Disease, and Mortality in the Elderly. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2108–2115. [CrossRef]

- Fogacci, F.; Cicero, A.F.G.; D’Addato, S.; D’Agostini, L.; Rosticci, M.; Giovannini, M.; Bertagnin, E.; Borghi, C.; Brisighella Heart Study Group Serum Lipoprotein(a) Level as Long-Term Predictor of Cardiovascular Mortality in a Large Sample of Subjects in Primary Cardiovascular Prevention: Data from the Brisighella Heart Study. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 37, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Langsted, A.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. High Lipoprotein(a) and High Risk of Mortality. Eur. Heart J. 2019, 40, 2760–2770. [CrossRef]

- Zewinger, S.; Kleber, M.E.; Tragante, V.; McCubrey, R.O.; Schmidt, A.F.; Direk, K.; Laufs, U.; Werner, C.; Koenig, W.; Rothenbacher, D.; et al. Relations between Lipoprotein(a) Concentrations, LPA Genetic Variants, and the Risk of Mortality in Patients with Established Coronary Heart Disease: A Molecular and Genetic Association Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 534–543. [CrossRef]

- Sawabe, M.; Tanaka, N.; Mieno, M.N.; Ishikawa, S.; Kayaba, K.; Nakahara, K.; Matsushita, S.; JMS Cohort Study Group Low Lipoprotein(a) Concentration Is Associated with Cancer and All-Cause Deaths: A Population-Based Cohort Study (the JMS Cohort Study). PloS One 2012, 7, e31954. [CrossRef]

- Langsted, A.; Kamstrup, P.R.; Nordestgaard, B.G. High Lipoprotein(a) and Low Risk of Major Bleeding in Brain and Airways in the General Population: A Mendelian Randomization Study. Clin. Chem. 2017, 63, 1714–1723. [CrossRef]

- Marcovina, S.M.; Albers, J.J. Lipoprotein (a) Measurements for Clinical Application. J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 526–537. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).