Submitted:

16 October 2024

Posted:

17 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

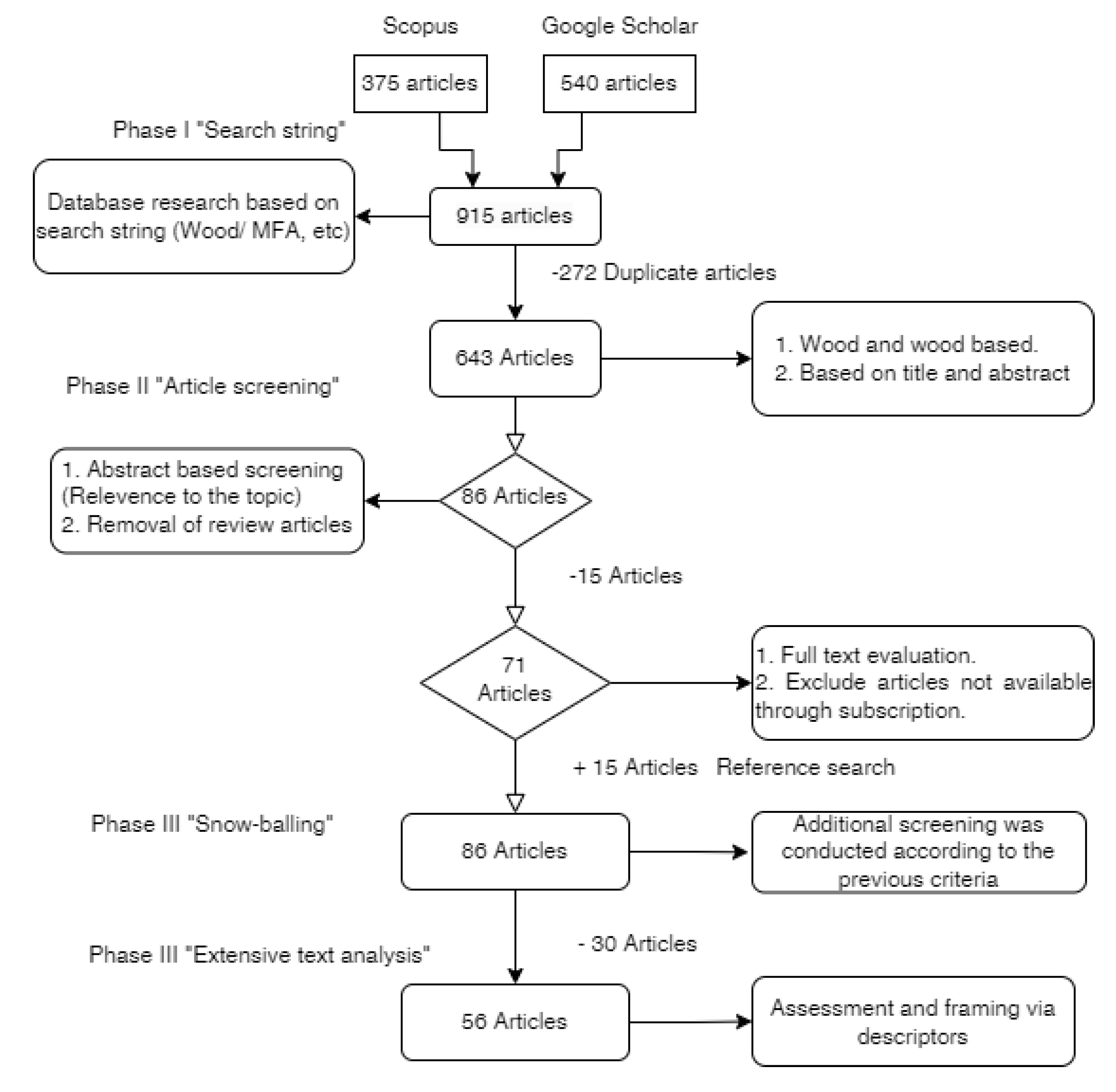

2.1. Literature Collection

2.2. Article Screening and Eligibility Criteria

- geographical scale (3.1),

- time scale (3.2),

- methodological approaches used in the construction of the MFA for wood-based products, related to the predominant use of the MFA (3.3),

- MFA data sources (3.4).

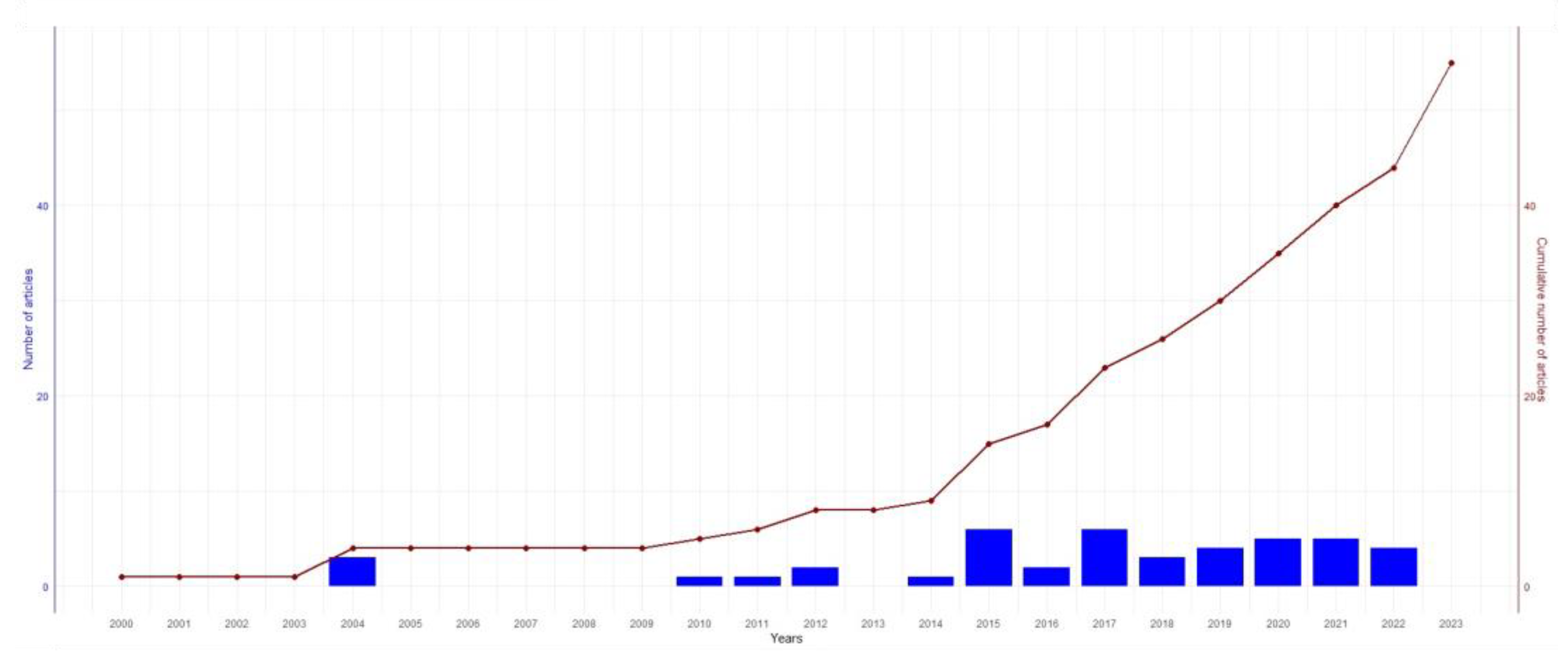

3. Results

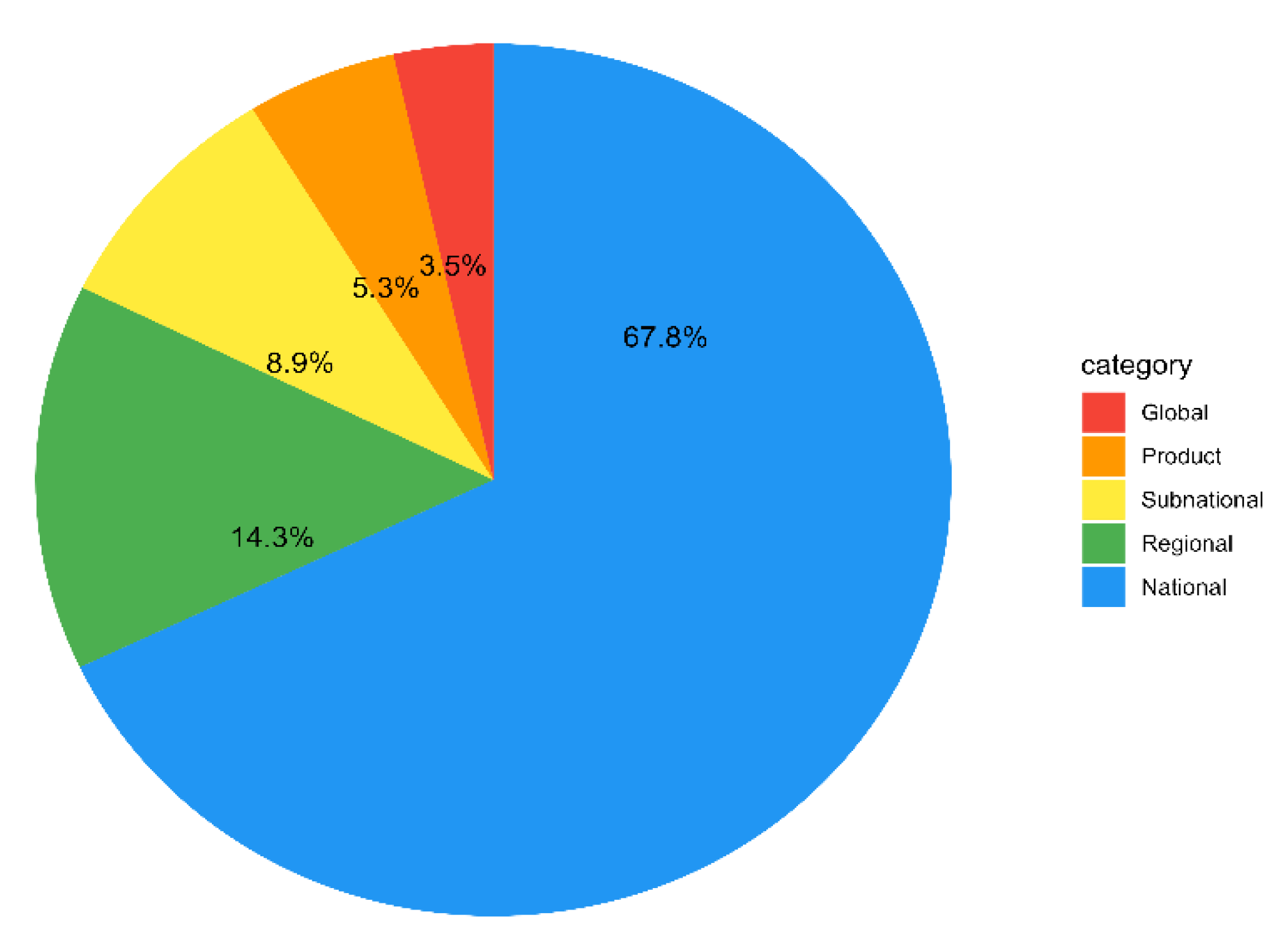

3.2. Geographical Scale

3.3. Time Scale

- Past-oriented MFA (ex-post assessment): 24 studies were based on past data, emphasizing the importance of ex-post ass assessments in understanding historical material trends and their implications. This perspective focus on analysing historical data to evaluate past material flow and stocks. By examining historical trends, past -oriented MFA offers insight into the evolution of material systems, identifies long-term patterns, and assesses the effectiveness of pervious material management practices. This approach aligns closely with spot MFA, which provides a snapshot at a specific point in time but can also utilize historical data to inform the current assessment.

- Future-oriented MFA (forecasting and scenarios analysis): 8 studies were focused on forecasting future trends, highlighting the value of scenarios-based forecasts for anticipating future material flows and potential sustainability challenges. This approach involves projecting future material flows based on different scenarios and assumptions. Future-oriented MFA is crucial for strategic planning and policymaking, as it helps anticipate potential challenges and opportunities in material management. By simulating various future scenarios, this perspective allows for the exploration of potential developments and supports informed decision-making for long-term sustainability.

- Routine vs ad-hoc: MFA studies can be part of routine assessment, regularly updated, or produced on an ad-hoc basis depending on specific research needs or emerging issues.

- Short-term vs. long-term perspectives: the temporal focus of MFA studies can range from short-term analyses, which are useful for immediate assessment, to long-term evaluation, which capture medium to long-term trends and impacts.

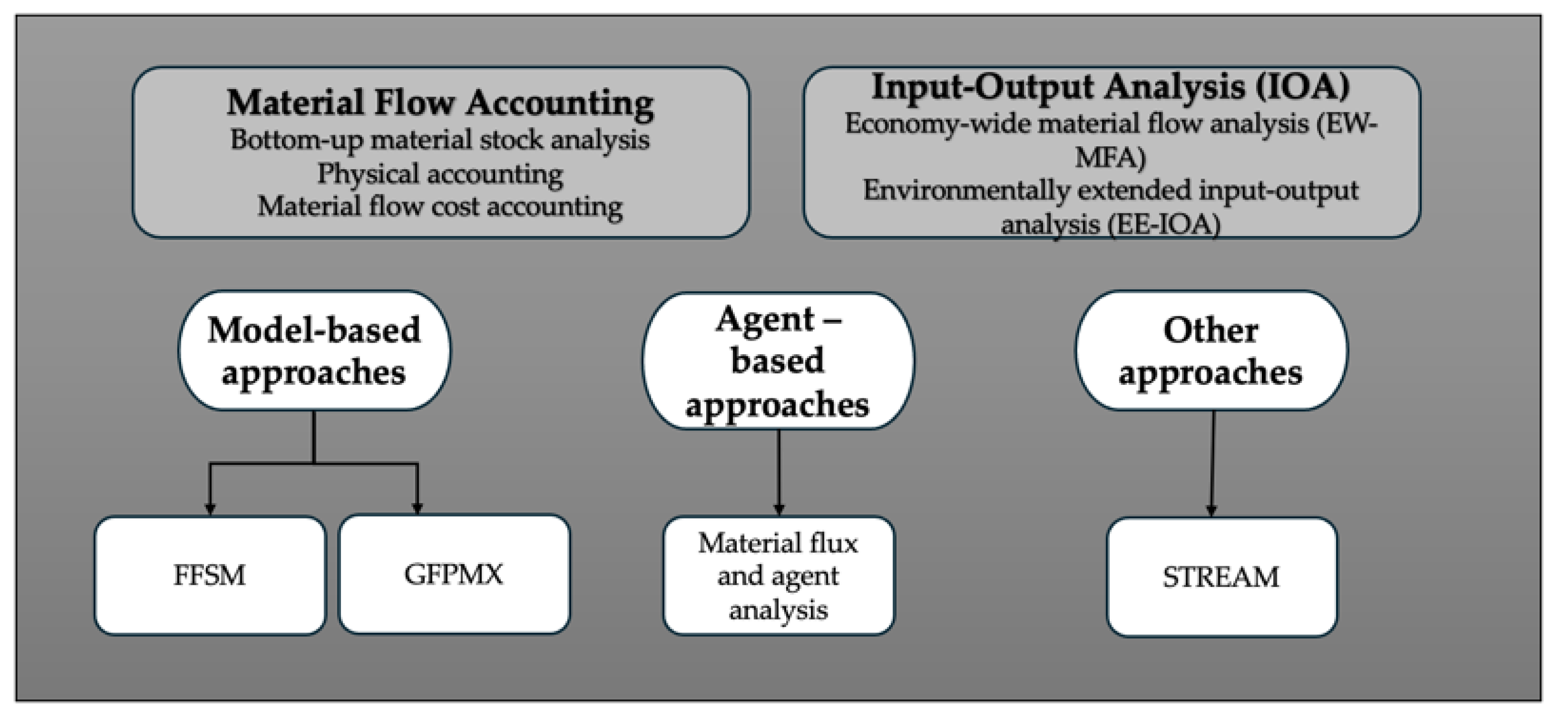

3.4. Methodological Approaches

3.4.1. Material Flow Accounting

3.4.2. Input-Output Analysis

3.4.3. Model-Based approaches

3.4.4. Agent-Based approaches

3.4.5. Other Approaches

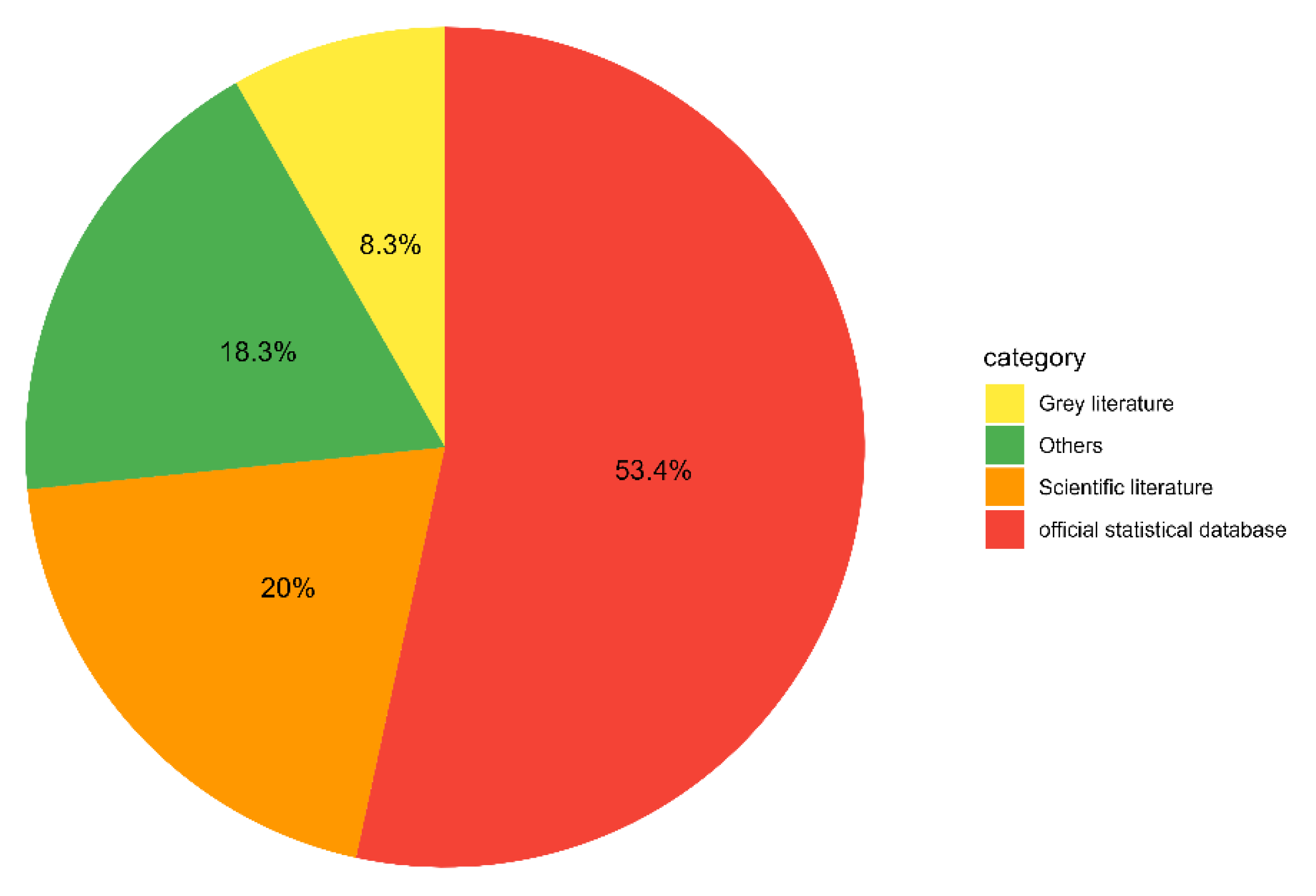

3.5. Data Sources

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kullmann, F., et al., Combining the worlds of energy systems and material flow analysis: a review. Energy, Sustainability and Society, 2021. 11(1): p. 13. [CrossRef]

- Balanay, R.M., R.P. Varela, and A.B. Halog, Circular economy for the sustainability of the wood-based industry: the case of Caraga Region, Philippines. Circular economy and sustainability, 2022: p. 447-462.

- Brunner, P.H. and H. Rechberger, Handbook of material flow analysis: For environmental, resource, and waste engineers. 2016: CRC press.

- OECD, O., Measuring material flows and resource productivity. 2008, Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development.

- Palahi, M. and J. Adams. Why the world needs a'circular bioeconomy'–for jobs, biodiversity and prosperity. in World Economic Forum. 2020. World Economic Forum Cologny, Switzerland.

- McCormick, K. and N. Kautto, The bioeconomy in Europe: An overview. Sustainability, 2013. 5(6): p. 2589-2608. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.T.P. and D.O. Meza, Lessons for the forest-based bioeconomy from non-timber forest products in Mexico, in The bioeconomy and non-timber forest products. 2022, Routledge. p. 92-108.

- Lenglet, J., J.-Y. Courtonne, and S. Caurla, Material flow analysis of the forest-wood supply chain: A consequential approach for log export policies in France. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2017. 165: p. 1296-1305. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J., et al., The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, 2021. 372. [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M. and H. Roberts, Systematic reviews in the social sciences: A practical guide. 2008: John Wiley & Sons.

- Mayring, P., Qualitative content analysis: theoretical foundation, basic procedures and software solution. 2014.

- Harzing, A.-W., The publish or perish book. 2010: Tarma Software Research Pty Limited Melbourne, Australia.

- Tsou, A.Y., et al., Machine learning for screening prioritization in systematic reviews: comparative performance of Abstrackr and EPPI-Reviewer. Systematic reviews, 2020. 9: p. 1-14. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T. and N. Huda, Reverse logistics and closed-loop supply chain of Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE)/E-waste: A comprehensive literature review. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2018. 137: p. 48-75.

- Parobek, J. and H. Paluš, Wood-Based Waste Management—Important Resources for Construction of the Built Environment, in Creating a Roadmap Towards Circularity in the Built Environment. 2023, Springer Nature Switzerland Cham. p. 213-223.

- Cammack, C., Material Flow Analysis of Wood in a Self-Sufficient Community. 2023.

- Gonçalves, M., F. Freire, and R. Garcia, Material flow analysis of forest biomass in Portugal to support a circular bioeconomy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2021. 169: p. 105507. [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, C., et al., Material flow analysis: a tool to support environmental policy decision making. Case-studies on the city of Vienna and the Swiss lowlands. Local Environment, 2000. 5(3): p. 311-328. [CrossRef]

- Allesch, A. and P.H. Brunner, Material flow analysis as a decision support tool for waste management: A literature review. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2015. 19(5): p. 753-764. [CrossRef]

- Streeck, J., et al., A review of methods to trace material flows into final products in dynamic material flow analysis: From industry shipments in physical units to monetary input–output tables, Part 1. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2023. 27(2): p. 436-456. [CrossRef]

- Burritt, R.L., T. Hahn, and S. Schaltegger, Towards a comprehensive framework for environmental management accounting—Links between business actors and environmental management accounting tools. Australian Accounting Review, 2002. 12(27): p. 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Baccini, P. and P.H. Brunner, Metabolism of the anthroposphere: analysis, evaluation, design. 2023: mit Press.

- Müller, D.B., H.P. Bader, and P. Baccini, Long-term coordination of timber production and consumption using a dynamic material and energy flow analysis. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2004. 8(3): p. 65-88. [CrossRef]

- Baccini, P. and H.-P. Bader, Regionaler stoffhaushalt: erfassung, bewertung und steuerung. 1996: Spektrum Akademischer Verlag Heidelberg.

- Cordier, S., et al. Enhancing consistency in consequential life cycle inventory through material flow analysis. in IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 2019. IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, N.H. and H. Brattebø, Analysis of energy and carbon flows in the future Norwegian dwelling stock. Building Research & Information, 2012. 40(2): p. 123-139. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M. and H. Haberl, Sustainable development: socio-economic metabolism and colonization of nature. International Social Science Journal, 1998. 50(158): p. 573-587. [CrossRef]

- Eker, M.; and Acar, H.H Actual Wood Flow Analysis for State-Forestry in Turkey. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Symposium of Forest Engineering and Technologies, Tirana, Albania, 04-06 September 2019; pp. 92.

- Bringezu, S., Material Flow Analysis—unveiling the physical basis of economies, in Unveiling Wealth: On Money, Quality of Life and Sustainability. 2002, Springer. p. 109-134.

- Mancini, L., L. Benini, and S. Sala, Resource footprint of Europe: Complementarity of material flow analysis and life cycle assessment for policy support. Environmental Science & Policy, 2015. 54: p. 367-376. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimian, F. and A. Mohammadi, Assessing the environmental footprints and material flow of 2, 3-butanediol production in a wood-based biorefinery. Bioresource Technology, 2023. 387: p. 129642. [CrossRef]

- Las Heras Hernández, M., System Analysis of a Multi-Plant Sawmill Company. Application to inform logistics. 2021, NTNU.

- Layton, R.J., et al., Material flow analysis to evaluate supply chain evolution and management: An example focused on maritime pine in the landes de gascogne forest, France. Sustainability, 2021. 13(8): p. 4378. [CrossRef]

- Hurmekoski, E., et al., Does expanding wood use in construction and textile markets contribute to climate change mitigation? Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2023. 174: p. 113152.

- Sevigné-Itoiz, E., et al., Methodology of supporting decision-making of waste management with material flow analysis (MFA) and consequential life cycle assessment (CLCA): case study of waste paper recycling. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015. 105: p. 253-262. [CrossRef]

- Szichta, P., et al., Potentials for wood cascading: A model for the prediction of the recovery of timber in Germany. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2022. 178: p. 106101. [CrossRef]

- Müller, D.B., Stock dynamics for forecasting material flows—Case study for housing in The Netherlands. Ecological economics, 2006. 59(1): p. 142-156. [CrossRef]

- Kalcher, J., G. Praxmarer, and A. Teischinger, Quantification of future availabilities of recovered wood from Austrian residential buildings. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2017. 123: p. 143-152. [CrossRef]

- Aryapratama, R. and S. Pauliuk, Estimating in-use wood-based materials carbon stocks in Indonesia: Towards a contribution to the national climate mitigation effort. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2019. 149: p. 301-311. [CrossRef]

- Suter, F., B. Steubing, and S. Hellweg, Life cycle impacts and benefits of wood along the value chain: the case of Switzerland. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2017. 21(4): p. 874-886. [CrossRef]

- Mehr, J., et al., Environmentally optimal wood use in Switzerland—Investigating the relevance of material cascades. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2018. 131: p. 181-191. [CrossRef]

- Bais-Moleman, A.L., et al., Assessing wood use efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions of wood product cascading in the European Union. Journal of cleaner production, 2018. 172: p. 3942-3954. [CrossRef]

- Nikodinoska, N., et al., Wood-based bioenergy value chain in mountain urban districts: An integrated environmental accounting framework. Applied Energy, 2017. 186: p. 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Bais, A.L.S., et al., Global patterns and trends of wood harvest and use between 1990 and 2010. Ecological Economics, 2015. 119: p. 326-337. [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Kowalski, M., et al., Methodology and indicators of economy-wide material flow accounting: State of the art and reliability across sources. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2011. 15(6): p. 855-876.

- Bide, T., et al., A bottom-up building stock quantification methodology for construction minerals using Earth Observation. The case of Hanoi. Cleaner Environmental Systems, 2023. 8: p. 100109. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadiziazi, R. and M.M. Bilec, Building material stock analysis is critical for effective circular economy strategies: a comprehensive review. Environmental Research: Infrastructure and Sustainability, 2022. 2(3): p. 032001. [CrossRef]

- Bilot, N., et al., Management-related energy, nutrient and worktime efficiencies of the wood fuel production and supply chain: modelling and assessment. Annals of Forest Science, 2023. 80(1): p. 15. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., et al., An urban material flow analysis framework and measurement method from the perspective of urban metabolism. Journal of cleaner production, 2020. 257: p. 120564. [CrossRef]

- Nasiri, B., C. Piccardo, and M. Hughes, Estimating the material stock in wooden residential houses in Finland. Waste management, 2021. 135: p. 318-326. [CrossRef]

- Seifert, H., New results about ternary lanthanide chlorides. Thermochimica acta, 1993. 214(1): p. 41-46. [CrossRef]

- Development, U.N.D.f.S., et al., Environmental management accounting procedures and principles. 2001: UN.

- Parobek, J., et al., Analysis of wood flows in Slovakia. BioResources, 2014. 9(4): p. 6453-6462. [CrossRef]

- Kalt, G., Biomass streams in Austria: Drawing a complete picture of biogenic material flows within the national economy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2015. 95: p. 100-111. [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.J.d., G. Schmidt, and U. Mantau, Wood resource balance for plantation forests in brazil: Resources, consumption and cascading use. Cerne, 2020. 26: p. 247-255. [CrossRef]

- Mantau, U., Wood flow analysis: Quantification of resource potentials, cascades and carbon effects. Biomass and bioenergy, 2015. 79: p. 28-38. [CrossRef]

- Parobek, J. and H. Paluš, Material flows in primary wood processing in Slovakia. Acta logistica, 2016. 3(2): p. 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Iost, S., et al., Setting up a bioeconomy monitoring: Resource base and sustainability. 2020.

- De Laurentiis, V., A. Galli, and S. Sala, Modelling the land footprint of EU consumption. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, 2022.

- Stahmer, C., M. Kuhn, and N. Braun, Physical Input-Output Tables for Germany, 1990, German Federal Statistical Office, prepared for DG XI and Eurostat. 1998.

- Bennett, M. and P. James, The Green Bottom Line: current practice and future trends in environmental management accounting. Sheffield: Greenleaf Publishing, 1998.

- Papaspyropoulos, K.G., et al., Challenges in implementing environmental management accounting tools: the case of a nonprofit forestry organization. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2012. 29: p. 132-143. [CrossRef]

- Kennerley, M. and A. Neely, A framework of the factors affecting the evolution of performance measurement systems. International journal of operations & production management, 2002. 22(11): p. 1222-1245. [CrossRef]

- Papaspyropoulos, K.G., et al., Enhancing sustainability in forestry using material flow cost accounting. Open Journal of Forestry, 2016. 6(5): p. 324-336. [CrossRef]

- Kokubu, K. and H. Tachikawa, Material flow cost accounting: significance and practical approach∗. Handbook of sustainable engineering, 2013: p. 351-369.

- ANDREADOU, M.V., Material Flow Cost Accounting as a method for finding Bioeconomy opportunities in the Forest Industry.

- Wagner, B., A report on the origins of Material Flow Cost Accounting (MFCA) research activities. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015. 108: p. 1255-1261. [CrossRef]

- Jasch, C.M., Environmental and material flow cost accounting: principles and procedures. Vol. 25. 2008: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Kovanicová, D., Material flow cost accounting in Czech environment. European Financial and Accounting Journal, 2011. 6(1): p. 7-18. [CrossRef]

- Herzig, C., et al., Environmental management accounting: case studies of South-East Asian companies. 2012: Routledge.

- Schaltegger, S. and D. Zvezdov, Expanding material flow cost accounting. Framework, review and potentials. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2015. 108: p. 1333-1341. [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, S. and K. Nakajima, Waste input–output material flow analysis of metals in the Japanese economy. Materials transactions, 2005. 46(12): p. 2550-2553. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, R., Ecological input-output analysis of material flows in industrial systems, in Handbook of Input-Output Economics in Industrial Ecology. 2009, Springer. p. 715-733.

- Bösch, M., et al., Physical input-output accounting of the wood and paper flow in Germany. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2015. 94: p. 99-109. [CrossRef]

- Bösch, M., et al., Costs and carbon sequestration potential of alternative forest management measures in Germany. Forest policy and Economics, 2017. 78: p. 88-97. [CrossRef]

- Krausmann, F., et al., Economy-wide material flow accounting introduction and guide. Institute of Social Ecology: Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- Krausmann, F., et al., From resource extraction to outflows of wastes and emissions: The socioeconomic metabolism of the global economy, 1900–2015. Global environmental change, 2018. 52: p. 131-140. [CrossRef]

- O'Brien, M. and S. Bringezu, European timber consumption: developing a method to account for timber flows and the EU's global forest footprint. Ecological economics, 2018. 147: p. 322-332.

- Kanianska, R., et al., Use of material flow accounting for assessment of energy savings: A case of biomass in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Energy Policy, 2011. 39(5): p. 2824-2832. [CrossRef]

- Wiedmann, N.S., A. Athanassiadis, and C.R. Binder, Streamlining the regionalization of economy-wide material flow accounts (EW-MFA): The case of swiss cantons. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 2023. 10: p. 100127. [CrossRef]

- Schweinle, J., et al., Monitoring sustainability effects of the bioeconomy: a material flow based approach using the example of softwood lumber and its core product Epal 1 Pallet. Sustainability, 2020. 12(6): p. 2444. [CrossRef]

- Matthews, A., Productivity growth in Irish agriculture. 2000.

- Weisz, H., et al., Economy-wide material flow accounting. A compilation guide. Eurostat and the European Commission, 2007.

- Schandl, H., et al., Handbook of Physical Accounting: Measuring Bio-Physical Dimensions of Socio-economic Activities; MFA, EFA, HANPP. 2002: Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Environment and Water ….

- Kitzes, J., An introduction to environmentally-extended input-output analysis. Resources, 2013. 2(4): p. 489-503. [CrossRef]

- Giljum, S., Environmentally extended input–output analysis (EE-IOA), in Dictionary of Ecological Economics. 2023, Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 204-205.

- Johansen, U., A. Werner, and V. Nørstebø, Optimizing the wood value chain in northern Norway taking into account national and regional economic trade-offs. Forests, 2017. 8(5): p. 172. [CrossRef]

- Miller, R.E. and P.D. Blair, Input-output analysis: foundations and extensions. 2009: Cambridge university press.

- Fujino, M. and M. Hashimoto, Economic and Environmental Analysis of Woody Biomass Power Generation Using Forest Residues and Demolition Debris in Japan without Assuming Carbon Neutrality. Forests, 2023. 14(1): p. 148. [CrossRef]

- Buongiorno, J., GFPMX: A Cobweb Model of the Global Forest Sector, with an Application to the Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability, 2021. 13(10): p. 5507. [CrossRef]

- Caurla, S. and P. Delacote, FFSM: a French forest-wood sector model which takes forestry issues into account in the fight against climate change. INRA Sciences sociales, 2013. 2013.

- Lecocq, F., et al., Paying for forest carbon or stimulating fuelwood demand? Insights from the French Forest Sector Model. Journal of Forest Economics, 2011. 17(2): p. 157-168. [CrossRef]

- Babuka, R., A. Sujová, and V. Kupčák, Cascade use of wood in the Czech Republic. Forests, 2020. 11(6): p. 681. [CrossRef]

- Binder, C.R., et al., Transition towards improved regional wood flows by integrating material flux analysis and agent analysis: The case of Appenzell Ausserrhoden, Switzerland. Ecological Economics, 2004. 49(1): p. 1-17.

- Binder, C.R., From material flow analysis to material flow management Part II: the role of structural agent analysis. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2007. 15(17): p. 1605-1617. [CrossRef]

- Ilc, S., ASSESSMENT OF THE DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL OF FOREST-WOOD PROCESSING CHAIN. 2016, Univerza v Novi Gorici, Fakulteta za podiplomski študij.

- Emmenegger, M.F., et al., Métabolisme des activités économiques du Canton de Genève–Phase 1. Repéré sur le site de la République et canton de Genève, section Thèmes, Environnement, Ecologie industrielle: http://www. ge. ch/themes/themes_environnement. asp, 2003.

- Suomalainen, E., Dynamic Modelling of Material Flows and Sustainable Resource Use: Case Studies in Regional Metabolism and Space Life Support Systems. 2012, Université de Lausanne, Faculté des géosciences et de l'environnement.

- Zhu, W., et al., Tracking the post-1990 sociometabolic transitions in Eastern Europe with dynamic economy-wide material flow analysis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2023. 199: p. 107280. [CrossRef]

- Mayer, A., et al., Measuring progress towards a circular economy: a monitoring framework for economy-wide material loop closing in the EU28. Journal of industrial ecology, 2019. 23(1): p. 62-76. [CrossRef]

- Streeck, J., et al., A review of methods to trace material flows into final products in dynamic material flow analysis: Comparative application of six methods to the United States and EXIOBASE3 regions, Part 2. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 2023. 27(2): p. 457-475. [CrossRef]

- Marques, A., et al., Contribution towards a comprehensive methodology for wood-based biomass material flow analysis in a circular economy setting. Forests, 2020. 11(1): p. 106. [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, O.G. and N.N. Deveci, Construction of physical supply-use and input-output tables for Denmark. Statistics Denmark, Eurostat grant agreement, 2014. 50904: p. 004-2012.432.

- Joosten, L., et al., STREAMS: a new method for analysing material flows through society. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 1999. 27(3): p. 249-266. [CrossRef]

- Hekkert, M.P., L.A. Joosten, and E. Worrell, Analysis of the paper and wood flow in the Netherlands. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2000. 30(1): p. 29-48. [CrossRef]

- Brownell, H., B.E. Iliev, and N.S. Bentsen, How much wood do we use and how do we use it? Estimating Danish wood flows, circularity, and cascading using national material flow accounts. Journal of Cleaner Production, 2023. 423: p. 138720. [CrossRef]

- Goldhahn, C., E. Cabane, and M. Chanana, Sustainability in wood materials science: An opinion about current material development techniques and the end of lifetime perspectives. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 2021. 379(2206): p. 20200339. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R. and P. Haller, Dynamic material flow analysis of wood in Germany from 1991 to 2020. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 2024. 201: p. 107339. [CrossRef]

- Van Eygen, E., et al., Resource savings by urban mining: The case of desktop and laptop computers in Belgium. Resources, conservation and recycling, 2016. 107: p. 53-64.

| Article title, Abstract, Keywords: mass flow analysis OR wood flow analysis OR wood value chain OR material flow analysis OR paper flow analysis |

| AND |

| Article title, Abstract, Keywords: wood resource balance OR wood balance OR spatial and temporal resource flows OR physical input-output table OR economic modelling OR dynamic modelling economic-wide material flow accounting OR dynamic stock modelling OR sankey diagram |

| AND |

| Article title OR keywords: Raw material OR Wood processing residues OR Wood utilization OR Natural resources OR Forest resources OR Forest product OR Forest sector modelling OR Wood based products OR Natural resources. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).