1. Introduction

SARS-CoV-2, a novel coronavirus causing respiratory illnesses of varying severity in humans (denominated as COVID-19), was first detected in December 2019 and spread rapidly across the world, leading to the declaration of a worldwide emergency by the World Health Organization (WHO) by March 2020 [

1]. Despite widespread adoption of preventive measures, including social distancing, reduction of in-person activities in schools and workplaces, cancelation of massive events, mandatory usage of facemasks and extensive vaccination efforts, COVID-19 prevalence stayed stubbornly high throughout the world during 2020, 2021 and 2022, as the WHO would not declare the end of the sanitary emergency until May 2023 [

2]. Incidence of COVID-19 cases showed a highly fluctuating behavior due to the continued emergence of new variants, driven by the high mutation rate of the viral RNA genome and the process of adaptation to both human immune responses and the deployment of vaccines and therapeutic agents [

3]. While the definition of “wave” may vary depending on different criteria or geographical regions, between six [

4] and seven [

5] waves were registered between January 2020 and March 2023, with varying levels of intensity depending on the degree of infectivity of the underlying variants of concern. A total of 775,615,722 cases were reported worldwide by June 2024, although limited testing indicates that actual incidence must be higher [

6].

As a part of epidemiological containment and prevention efforts undertaken by public health authorities, there has been a growing interest in modelling the spread of the disease within populations [

7]. The main approaches have included mechanistic models, based on the infection patterns seen in the population and the deployment of protective measures, including social distancing and vaccination [

8], and statistic models, based mostly on clinical reports and supporting data, including social mobility dynamics, weather reports, pollution levels, and even social media activity, among others [

9]. Recent studies have taken advantage of machine-learning approaches to integrate large datasets (sometimes encompassing more than one country) and develop advanced regression models, as the capacity of linear models to reflect on infection patterns has proven limited [

10]. Neural network-based models, such as artificial neural networks (ANN), bidirectional long short term memory (LSTM), adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS), autoregressive integrated moving average (ARIMA), and multilayer perceptron (MLP), have been trained on clinical reports published by public health authorities to predict future cases, reaching R2 coefficients of determination (R2) between 0.62 and 1 and d mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) generally below 10% [

10].

While most studies have used reported clinical data, integrating parallel data to develop a fuller image of public health status in a population might be useful to develop better epidemiological models. In this regard, data arising from wastewater-based surveillance (WBS) might be a useful resource, as it allows for time and resource-efficient study of a population by tracking and quantifying specific biomarkers in wastewater samples, which are representative of the entire population within the catchment area of the sampling point of interest [

11]. Moreover, WBS data shows potential for risk assessment models as they can represent cases regardless of the level of individual clinical cases or the onset of symptoms [

12]. Moreover, as studies have demonstrated that COVID-19 has an incubation period of around 5 to 7 days [

13], increases in the load of viral genetic materials in wastewater samples may increase noticeably before the onset of epidemiological waves. However, it is important to note that WBS data should not be analyzed in isolation and should be integrated into epidemiological reports to obtain valuable information, as high biomarker variability, the lack of a standardized normalization technique and interference due to high matrix complexity are ongoing challenges for the interpretation of WBS data for public health assessment [

14].

Following this line, this work reports on the integration of WBS data obtained at key sampling points in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area (MMA, 5,341,171 inhabitants) and Mexico City (CDMX, 21,804,515 inhabitants) between January 2021 and June 2022 into simple, statistic prediction models based on machine-learning algorithms. Two main approaches were followed: clustering of weekly datapoints as above or below a threshold indicative of a COVID-19 outbreak, and regression models offering an estimate of the seven-day average new reported daily COVID-19 cases adjusted for population size.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Data Aquisition

Data on SARS-CoV-2 viral load in wastewater samples (presented as viral genome copies per liter of wastewater) originating from the MMA and CDMX was compiled from the dataset previously obtained from the WBS platform operated by our laboratory between January 2021 and March 2022 [

15]. Briefly, 1 liter grab samples were obtained weekly from designated sampling sites encompassing both facilities of the largest private higher education institution in Mexico and wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs), transported to the central laboratory and concentrated using a polyethylene glycol and NaCl-based method [

16]. RNA was extracted using the DNA/RNA Magnetic Bead Kit (IDEXX, Westbrook, Maine) adapted for automation using a KingFisher™ Flex instrument (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, Massachusetts), and SARS-CoV-2 viral load was determined through the SARS-CoV-2 RT-qPCR Test kit for wastewater samples (IDEXX) on a QuantStudio 5 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, Massachusetts). Sampling sites within the two university campuses (one in the MMA and one in CDMX) were clustered together, and the data captured each week includes the maximum viral load obtained across all sampling sites, the percentage of sampled buildings (calculated as the ratio between the number of samples obtained each week and the total amount of sampling sites within the campus) and the percentage of buildings were viral load was detected (calculated as the ratio between samples that tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 genetic materials). In samplings at WWTPs, only the total viral load detected was registered.

Daily new reported COVID-19 cases for the state of Nuevo León (where the MMA is located) and the CDMX were obtained from the dashboard published by the National Council of Humanities, Sciences and Technologies (CONAHCYT) with data provided by the General Direction of Epidemiology, a part of the Mexican Department of Health (available at

https://datos.covid-19.conacyt.mx/). To make both time series comparable, a seven-day average of daily new cases was calculated for each week. Finally, data on urban mobility for both the state of Nuevo León and the CDMX was obtained from the COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports published by Google in 2021 and 2022 for the Mexican state of Nuevo León (available at

https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/). The average of the six reported parameters was used as an overall indicator of mobility, and a seven-day average was calculated for each week. The complete database used for this study is reported in

Table S1.

2.2 PCA and Heatmap

To observe the behavior of the obtained parameters across the study period, data normalization for PCA plots and heatmaps were conducted in ClustVis [

17]. To ensure data robustness and comparability, weeks when the percentage of sampled buildings within either campus fell below 20% and no data from the WWTP was reported were filtered out of the database. To control the effect of the different population sizes, the seven-day average of daily new reported cases was inputted as the number of cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Data received no further transformation. For each parameter, data was scaled using unit variance scaling and PCA was conducted using the Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) method. Each data point was annotated by the city it represented (either MMA or CDMX), and whether it originates from a surge in clinical reports or not. Separated PCA plots were made classifying data points based on both criteria, and ellipses were drawn using a 95% level of confidence. For the heatmap, both rows and columns were clustered using the Ward algorithm through their degree of correlation.

2.3 Cluster-Based Predictive Models

For the development of cluster-based predictive models, the seven-day average of new daily cases was plotted across the study period for both cities and a threshold was set for each city, to divide the weekly data points into two groups: those above the threshold (indicating a new outbreak) and those below the threshold (indicating the basal condition during the pandemic). For the MMA, the threshold was set at 200 daily cases, while for CDMX it was set at 1000 daily cases, which is consistent with the different population sizes. For each week, it was evaluated whether the seven-day average of new daily cases was above the threshold in the current week, and one and two weeks into the future, in accordance with the estimated incubation period reported by the WHO (of up to 14 days) [

13] to test if an increase in the viral loads detected in wastewater samples could be detected before a surge in reported cases. For each parameter, data was scaled using unit variance scaling and did not receive any transformation.

The resulting datasets for both cities were combined into one and divided randomly into a training set and a testing set. Clustering algorithms were developed using the fitcauto function in Matlab R2024a, running a Bayesian optimizer for 100 iterations for optimization with the default option to fold the training data five times for cross-validation. During training, whether clinical cases were above or below the set threshold in the same week as wastewater sampling was conducted. Only the training subset was fed into the learning function. Given the characteristics of the data being studied (small dataset with low dimensionality), the optimization process was centered around linear learners. Clustering model performance was evaluated by calculating its accuracy rate, sensitivity, specificity, and Youden’s index on both training and testing subsets. If performance metrics were found to be too different for both models, a sign of possible overfitting, training was repeated. After obtaining a suitable model, it was used to make forecasts one and two weeks into the future, which were evaluated using the same metrics mentioned above.

2.4 Regression-based Predictive Models

For the development of regression-based predictive model, only the maximum viral load from each university campus, the viral load from the selected WWTP from each city and the weekly average change in mobility was considered, while daily cases were set as the output of the model. Viral load data was transformed using the decimal logarithm of the viral load from each location plus one (to avoid indefinite numbers). The seven-day average daily cases were expressed as a ratio per 100,000 inhabitants to control for different population sizes across the two cities. The transformed values for each parameter were then scaled using unit variance scaling.

The resulting datasets for both cities were combined into one and divided randomly into a training set and a testing set. Regression models were obtained using the “fitrauto” function in Matlab R2024a, running a Bayesian optimizer for 100 iterations for optimization with the default option to fold the training data five times for cross-validation. Only the training subset was fed into the learning function. Learner algorithms were selected automatically by the training function to better suit the characteristics of the data (small dataset, low dimensionality, linear behavior). Model performance was evaluated using Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), R² coefficient, and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) on both training and testing subsets. If performance metrics were found to be too different for both models, a sign of possible overfitting, training was repeated.

3. Results

3.1. PCA and Heatmap

After filtration, the resulting database included 48 data points, 29 from the MMA and 19 from CDMX. The main limiting factor in the MMA was the large number of sampling sites encompassed within the studied university campus, which limited our ability to reliably sample them all across the entire study period. In CDMX, while the studied university campus was significantly smaller, our capacity to take samples from urban wastewater reduced the amount of available data. 19 of the 48 data points originated during reported surges in clinical reports, while the remaining 29 come from periods between surges.

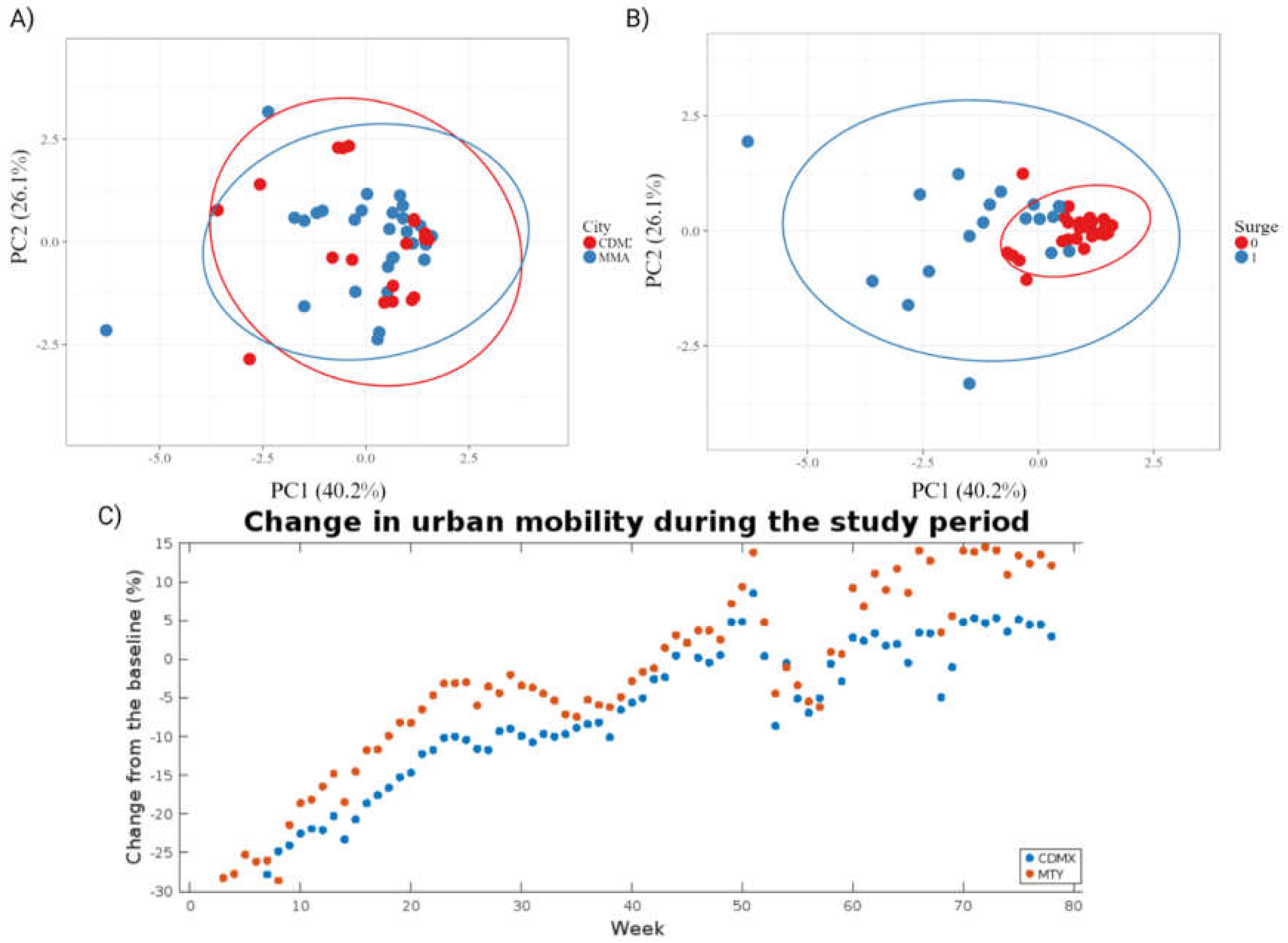

PCA plots for the data classified by city of origin and the reported epidemiological situation in the corresponding time frame are presented in

Figure 1A and 1B, respectively. As expected, no clear separation between the two cities is observed when plotting PC1 (accounting for 40.2% of variance) against PC2 (accounting for 26.1% of variance), indicating that transmission dynamics are likely similar after controlling for population size. In fact, the average change in mobility presented in the COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports published by Google during the study period, reported as percentage change from a pre-pandemic baseline, show similar behaviors in both cities (

Figure 1C). This is to be expected, since the interconnectedness of population centers due to economic globalization has been noted as a driver in the rapid spread of SARS-CoV-2 [

18]. Overall, similar patterns of surges and reductions in clinical cases, and comparable containment measures can be seen in both cities. As a result, datapoints can be reliably combined for modeling after controlling for the different population sizes. This is consistent with reports by [

19], where surges in COVID-19 cases at regional and country levels across 2020 and 2021 were found to appear at similar times and have similar durations.

Meanwhile, classifying data points by whether a surge in clinical cases was reported in the corresponding week yields some degree of separation in the PCA plot, although no clear clusters could be fully defined. The ellipses are drawn around the area of 95% confidence for each group overlap. However, data points corresponding to periods between surges (in red) show low dispersion along the PC1 (accounting for 40.2% of variance) and PC4 (10% of variance) axis, while the data points corresponding to surges (in blue) in clinical cases were noticeably more dispersed, most of them falling outside the cluster of data points corresponding to periods between surges. This indicates that differential patterns in the parameters of interest exist, although some degree of confusion in the model is to be expected.

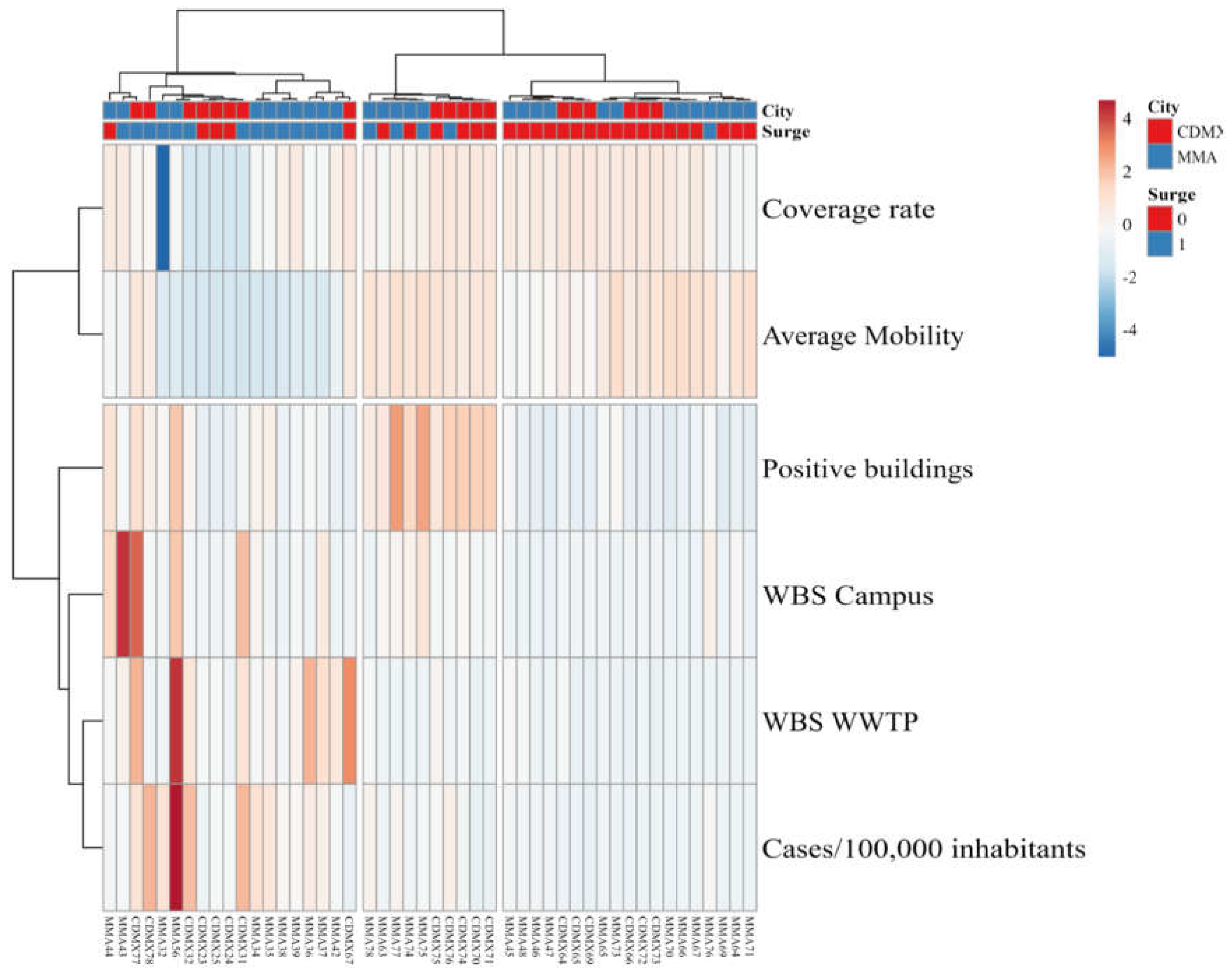

The obtained heatmap is presented in

Figure 2. Observations, presented in the columns, were clustered into three groups: one where data points taken during surges in clinical cases were overrepresented (14/19 data points), shown in the left; one where weeks in between surges are overrepresented (18/19 data points), shown in the right; and a middle group, composed of ten data points, that remained ambiguous. This degree of confusion during clustering is consistent with the overlap observed in the PCA plot presented in

Figure 1B.

When it comes to the parameters, presented in the rows, the number of new cases by 100,000 inhabitants showed correlation to both the viral load found in samples from the WWTPs, the maximum viral load found on any sample from the university campus studied in each city and the rate of sampling sites where viral load was detected on each campus, all of them increasing during surges in clinical case reports. Meanwhile, average urban mobility and the percentage of tested buildings on each campus showed the inverse behavior, being placed on a separate cluster.

Interestingly, data points in the middle cluster showed higher rates of positive buildings while sampling coverage remained close to the average on each campus, but no significant surge in clinical reports is observed. Data in this middle cluster comes from May and June 2022, after urban mobility for both cities went back to pre-pandemic levels and are likely an anticipation of the surge in cases that lead to the fifth wave of COVID-19 cases in Mexico, which took place during the summer of 2022 [

20]. This is consistent with our previous report, where we demonstrated that Omicron variants circulated in wastewater from university campuses across Mexico between January and March 2022 [

21]. This observation supports the potential of decentralized, building by building WBS platforms in high affluence areas, such as university campuses, as the rate of positive samples taken each week can provide relevant information for decision-making when overall populational dynamics are accounted for. Similar observations were reported by Wolken et al. [

22], from data using a similar WBS platform across preK-12 schools in Houston operated between December 2020 and May 2022.

3.2. Cluster-based risk asessment model

For training and testing of cluster-based risk assessment models, 30/48 and 18/48 of the total observations in the dataset, combining data from both the MMA and CDMX were used, respectively. After optimization, the resulting cluster-based risk assessment model was built using a linear classification discriminant. Model performance metrics are presented in

Table 1. In short, the model had an accuracy of 0.833 for both training and test subsets, indicating a clustering capacity close to that of the heatmap presented in the previous subsection.

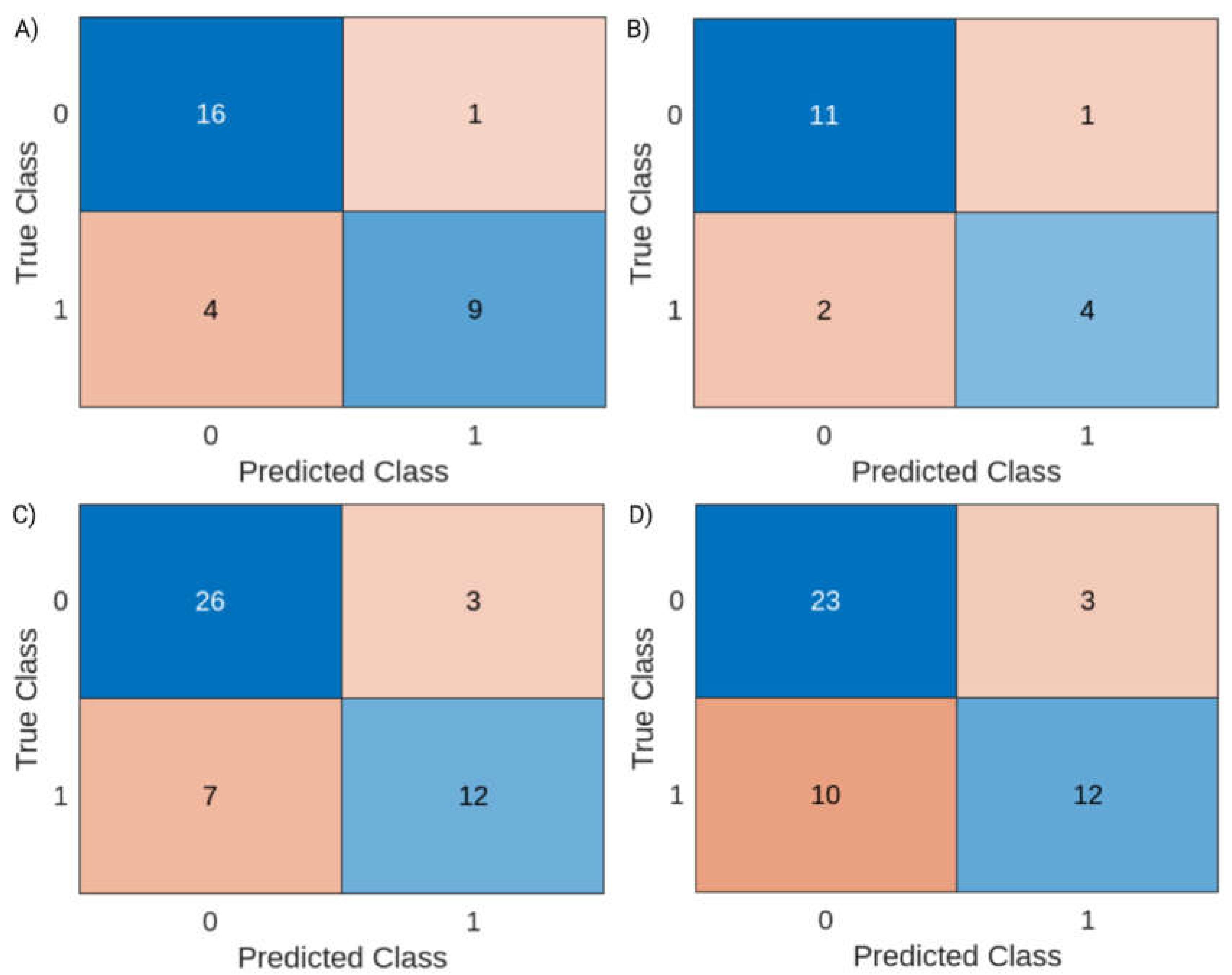

The confusion charts presented in

Figure 3A,B indicate that the model generalizes well, using general trends in WBS data to separate data points linked increased clinical reports were observed and those linked to periods between surges instead of amplifying unrelated background variances. However, the observed Youden’s index decreased slightly, from 0.63 in the training subset to 0.58 in the test subset. After the optimized model proved satisfactory, it was used to provide forecasts one and two weeks into the future using the same dataset to investigate whether the trends observed during clustering could be used for risk-. As seen in

Table 1, predictions one week into the future showed an accuracy rate of 0.79 and a Youden of 0.53. Predictions two weeks into the future had a more modest outcome, with metrics of 0.73 and 0.43, respectively. As seen in the confusion charts presented in

Figure 3C,D, the model had a certain tendency to yield false negative predictions (7/48 for one-week predictions and 10/48 for two-week predictions).

The difference is likely since SARS-CoV-2 incubation period has been found to be between 5 to 7 days, shorter than initially expected [

13], reducing the window of time in which increased viral loads could be found in wastewater samples before surges. Still, this supports the potential of WBS platforms can provide valuable information on epidemiological trends, which can be used for decision-making by public health authorities [

23]. Moreover, sampling approaches such as this one, combining data from WWTPs and decentralized sampling points located at high affluency sites (in this case, at college campuses), can be used for more focalized preventive and containment measures, allowing for continued operation in such sites while keeping them from becoming transmission hotspots [

24]. In any case, it’s important to remark that WBS data cannot be used or isolation nor is it a substitute to individualized clinical testing; rather, as discussed by Islam et al. [

14], these approaches should be conducted collaboratively to obtain more robust datasets.

3.3 Regression-based Predictive Models

For training and testing of regression-based predictive models, 30/47 and 18/47 of the total observations in the dataset, combining data from both the MMA and CDMX were used, respectively. One data point, corresponding to data from the MMA during week 56 (January 2023) had to be eliminated since it represents unusually high clinical reports caused by Christmas-related increases in urban mobility. Moreover, insufficient sampling was conducted in the weeks prior and after this point due to the winter break at the institution and restricted laboratory activities in January and early February 2023 due to the fourth wave of contagions in Mexico [

25], leaving the datapoint from week 56 as an outlier that hindered the effectivity of regression learners during training. After optimization, the resulting model was a linear regression using a least squares-based learner. Model performance metrics are presented in

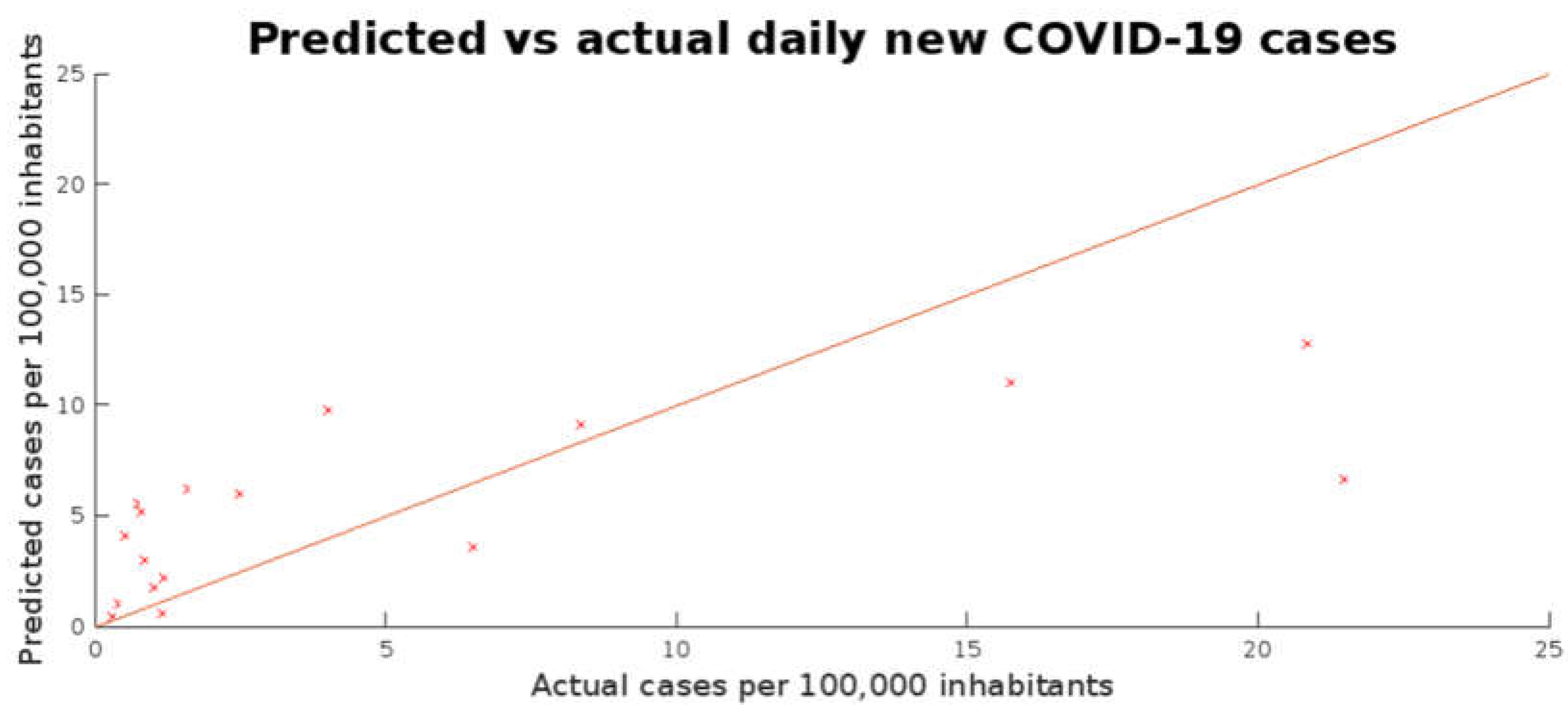

Table 2, while a plot of the predicted response against the actual weekly average of daily new COVID-19 cases is presented in

Figure 4.

In short, the model showed a consistent performance on both the training and test subsets, with R2 of 0.452 and 0.464, respectively, indicating that variations in viral loads in wastewater samples from both university campuses and WWTPs in the MMA and CDMX, urban mobility rates and the rate of positive samples within each of the university campuses could account for roughly half of the variance seen in epidemiological results. However, quantitative error remains significant: RMSE for the training subset was 5.223 and 5.118 for the test subset, when the average true responses were 6.405 and 5.1712, respectively. This is consistent with the MAPE observed in both subsets, which was close to 200%.

In the same line,

Figure 4 shows that in data points where the actual responses were below 5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants, the model tended to overestimate cases based on viral loads in wastewater samples, while it underestimated when the actual responses were above 5 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. A possible explanation for this indicates two main shortcomings in the dataset. The first is its size, as observations where campus coverage was below 20% and no corresponding sampling at the city’s selected WWTP was reported were filtered out of the database before training. Second, surges in COVID-19 case reports were followed by restrictions in campus occupancy rates and reduced urban mobility. While urban mobility could be accounted for, no direct data on campus occupancy or clinical testing within the institution was available to the team. Integrating such parameters into the model may increase the variance in the responses explained by the model. While some of these shortcomings could be addressed using non-linear regression learners, overfitting remains a concern in such models, especially when using datasets published by public health authorities, which tend to be incomplete [

26].

The models reported here show significantly lower predictive performance when compared to those reviewed by Ghafouri-Fard et al. [

10], which offer forecasts based on previous clinical reports, weather data and even internet search history with R2 values between 0.65 and 1 and MAPE values below 10%. However, the use of data from WBS platforms for predictive models has proven significantly more difficult. In a study by Lai et al. [

27] investigating the potential of time series machine learning to make forecasts of COVID-19 cases using both epidemiological reports WBS data from the states of Pennsylvania and Wyoming, the lowest MAPE values observed were still around 39%, with some WBS-based models still being outperformed by “naïve” models, which did not take WBS data into account for training. A similar approach by Ai et al. [

28] recommends the use of long short-term memory to obtain highly generalizable models that could account for a higher degree of variance in the response (R2 of up to 0.81 in the test set), while also highlighting the importance of avoiding overfitting when using such learner algorithms. This is because detection and quantification of viral loads in wastewater samples shows a high level of variability due to unsteady wastewater flow in the sampling sites and degradation of genetic materials because of external factors, such as pH, temperature, enzymatic activity, and light exposure [

29]. Taking these factors into account during feature engineering has proven relevant by the two studies mentioned previously, although data allowing for such fine-tuned predictive models was unavailable for the present study.

4. Discussion

This work presents an evaluation of simple machine-learning models using linear learners for risk assessment using WBS data from both university campuses and WWTPs in CDMX and MMA, the two largest cities in Mexico. Such models were sufficient to observe correlations between viral loads in wastewater samples and offer forecasts that could be used for risk management and contention in high facilities, like educative centers or workspaces, although their capacity for long-term forecasting may be limited when compared to more sophisticated models, like long short-term memory regressions. The ability to use finer models, however, was limited by the size and the dimensionality of the dataset, as proven by the higher performance of models that took environmental factors that could drive genetic material degradation into account, such as wastewater flow at the sampling sites, pH and temperature, among others [

27,

28]. Integrating viral load data from a wider arrange of sampling sites located across the country with relevant epidemiological factors at play (mobility within cities, vaccination rates, test positivity rates) could be used to provide models that can better represent trends across the country. In any case, adequate measures should be taken to prevent model overfitting, especially if non-linear models are used [

26].

In any case, drawing correlations between the quantification of disease-related biomarkers and the prevalence of the disease of interest within a population remains an area of opportunity for developments in WBS. McMahan et al. [

30] integrated wastewater measurements into a susceptible-exposed-infectious-recovered (SEIR) model which led to an estimation of the rate of COVID-19 cases underreporting of roughly 11 unreported cases for each reported case, which closely matched previous estimates by public health officials for the area at the time of study (15 unreported cases for each reported case). Melvin et al. [

31] proposed a novel normalization and standardization process, the Melvin Index, to control the impact of site variability during sampling in qPCR-based SARS-CoV-2 genetic material quantification. Using this method, surges in clinical reports could be predicted over up to 15-17 days using data from several sampling sites across the state of Minnesota, USA. Hewitt et al. [

32] related the frequency of SARS-CoV-2 viral detection at a managed isolation and quarantine facility to the one seen at a WWTP during a window of time at which incidence was reportedly low. By relating both measures, they estimated the possibility of detecting SARS-CoV-2 genetic materials in wastewater from WWTPs, representative of the overall population, at 87% when prevalence in the population was at 0.01%.

Recently, Mohring et al. [

33] reported on an approach for a finer estimate of COVID-19 cases from WBS data where a cohort was regularly followed during the study period using self-administered antigen tests. They reported the need to use both a scaling factor and a delay window to relate SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in wastewater samples with COVID-19 prevalence. Interestingly, the delay window they found, around 5 days, closely matches the incubation period of the virus (Zaki and Mohamed, 2021).

Development of statistical models integrating WBS data for risk assessment will likely be useful during the first stages of future pathogen outbreaks as a first tool for decision-making if the modeled pathogen proves to have similar transmission routes to the novel pathogen of concern. For instance, knowledge obtained from modelling the COVID-19 pandemic could be useful in case of an outbreak of a highly transmissible, airborne, viral disease, such as a possible increase in zoonotic transmission of Influenza A H5N1, as it has been reported recently (Dye & Barclay, 2024).

5. Conclusions

In this paper, a database resulting from the detection and quantification of SARS-CoV-2 viral loads in wastewater samples originating from university campuses and WWTPs in the MMA and CDMX were used to train both clustering and regression models built using linear learner algorithms to study trends in the evolution of daily new COVID-19 during the pandemic. While linear classification discriminant analysis could distinguish between wastewater data obtained during clinical report surges and periods between surges at 83.3% accuracy, and the trends observed by the model could be used for forecasting, the performance of regression-based models remained limited due to low dimensionality in the data, as relevant environmental measurements for determination of sample integrity, such as pH, temperature or wastewater flow at the sampling sites were not available. While the approach explored here can be used for simple risk assessment for the deployment of adequate prevention and containment strategies within high-affluence facilities, such as universities or workspaces, especially in the early stages of a possible epidemiological outbreak, further work toward integration of more robust datasets into more complex models, capable of long-term forecasting that could be used for future pathogens similar to COVID-19 is still needed.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Table S1. Complete database used in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.-C.; O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A.; M.A.O.-M.; and J.E.S.-H; methodology, A.A.-C.; software, A.A.-C.; A.F.-T.; validation, A.A.-C.; O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A and J.E.S.-H.; formal analysis, A.A.-C.; investigation, A.A.-C.; O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A.; M.A.O.-M. and J.E.S.-H; data curation, A.A.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A.-C.; O.d.l.R.; and J.E.S.-H; writing—review and editing, A.A.-C.; O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A, A.F.-T. and J.E.S.-H; visualization, A.A.-C.; A.F.-T.; validation; supervision, O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A.; R. P. S.; and J.E.S.-H; project administration, O.d.l.R.; A.A.-A.; M.A.O.-M.; R. P.-S.; and J.E.S.-H; funding acquisition, R. P.-S.; and J.E.S.-H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundación FEMSA project entitled “Unidad de respuesta rápida al monitoreo de COVID19 por agua residual” (grant number NA). This work was supported by Tecnologico de Monterrey through the project Challenge-Based Research Funding Program 2022 (Muestreador Pasivo I026 - IAMSM005 - C4-T1 - T).

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting results is available in the supplementary materials section. For any other related information please contact the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This project acknowledges the Biotechnology Center - FEMSA and MARTEC from Tecnológico de Monterrey for the provision of the physical space for the development of the project. The authors aknowledge the support of Tecnologico de Monterrey for granting access to literature services and the scholarship awarded to Arnoldo Armenta-Castro (CVU: 1275527) and partially supporting this work under Sistema Nacional de Investigadores program awarded to Alberto Aguayo-Acosta (CVU: 403948), Mariel A. Oyervides-Muñoz (CVU: 422778), Roberto Parra-Saldívar (CVU: 35753) and Juan Eduardo Sosa-Hernández (CVU: 375202).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mingaleeva, R.N.; Nigmatulina, N.A.; Sharafetdinova, L.M.; Romozanova, A.M.; Gabdoulkhakova, A.G.; Filina, Y.V.; Shavaliyev, R.F.; Rizvanov, A.A.; Miftakhova, R.R. Biology of the SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2022, 87, 1662–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bennett, C.M.; Vally, H. The evolving epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. Microbiology Australia 2024, 45, 4–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, E.C. (2024). The Emergence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Annual Review of Virology. [CrossRef]

- Manabe, H.; Manabe, T.; Honda, Y.; Kawade, Y.; Kambayashi, D.; Manabe, Y.; Kudo, K. Simple mathematical model for predicting COVID-19 outbreaks in Japan based on epidemic waves with a cyclical trend. BMC Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Martín-López, J.V.; Mesa, N.; Bernal-Bello, D.; Morales-Ortega, A.; Rivilla, M.; Guerrero, M.; Calderón, R.; Farfán, A.I.; Rivas, L.; Soria, G.; Izquierdo, A.; Madroñal, E.; Duarte, M.; Piedrabuena, S.; Toledano-Macías, M.; Marrero, J.; De Ancos, C.; Frutos, B.; Cristóbal, R.; … Ruiz-Giardin, J.M. Seven Epidemic Waves of COVID-19 in a Hospital in Madrid: Analysis of Severity and Associated Factors. Viruses 2023, 15, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, H.; Mathieu, E.; Rodés-Guirao, L.; Appel, C.; Giattino, C.; Hasell, J. (2020, 2024). Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19) (6). Our World in Data. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus.

- Jewell, N.P.; Lewnard, J.A.; Jewell, B.L. Predictive Mathematical Models of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Underlying Principles and Value of Projections. JAMA 2020, 323, 1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desikan, R.; Padmanabhan, P.; Kierzek, A.M.; Van Der Graaf, P.H. Mechanistic Models of COVID-19: Insights into Disease Progression, Vaccines, and Therapeutics. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 2022, 60, 106606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolkewitz, M.; Lambert, J.; Von Cube, M.; Bugiera, L.; Grodd, M.; Hazard, D.; White, N.; Barnett, A.; Kaier, K. Statistical Analysis of Clinical COVID-19 Data: A Concise Overview of Lessons Learned, Common Errors and How to Avoid Them. Clinical Epidemiology, 2020; 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghafouri-Fard, S.; Mohammad-Rahimi, H.; Motie, P.; Minabi, M.A.S.; Taheri, M.; Nateghinia, S. Application of machine learning in the prediction of COVID-19 daily new cases: A scoping review. Heliyon 2021, 7, e08143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Rodríguez, M.G.; Silva-Lance, F.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Medina-Salazar, D.A.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Martínez-Prado, M.A.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Barceló, D.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E. Biosensors for the detection of disease outbreaks through wastewater-based epidemiology. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2022, 155, 116585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.C.; Aubee, A.; Babahaji, L.; Vigil, K.; Tims, S.; Aw, T.G. Targeted wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 on a university campus for COVID-19 outbreak detection and mitigation. Environmental Research 2021, 200, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, N.; Mohamed, E.A. The estimations of the COVID-19 incubation period: A scoping reviews of the literature. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2021, 14, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, Md. A.; Hossen, F.; Rahman, Md. A.; Sultana, K.F.; Hasan, M.N.; Haque, Md. A.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Ahmed, T.; Islam, Md. T.; Dhama, K.; Sangkham, S.; Bahadur, N.M.; Reza, H.M.; Jakariya, Md.; Al Marzan, A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Sonne, C.; Ahmed, F. An opinion on Wastewater-Based Epidemiological Monitoring (WBEM) with Clinical Diagnostic Test (CDT) for detecting high-prevalence areas of community COVID-19 infections. Current Opinion in Environmental Science & Health 2023, 31, 100396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Driver, E.M.; Bowes, D.A.; Kraberger, S.; Lucero-Saucedo, S.L.; Fontenele, R.S.; Parra-Arroyo, L.; Holland, L.A.; Peña-Benavides, S.A.; Newell, M.E.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Adhikari, S.; Rodas-Zuluaga, L.I.; Kumar, R.; López-Pacheco, I.Y.; Castillo-Zacarias, C.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; … Parra-Saldívar, R. Extensive Wastewater-Based Epidemiology as a Resourceful Tool for SARS-CoV-2 Surveillance in a Low-to-Middle-Income Country through a Successful Collaborative Quest: WBE, Mobility, and Clinical Tests. Water 2022, 14, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapula, S.A.; Whittall, J.J.; Pandopulos, A.J.; Gerber, C.; Venter, H. An optimized and robust PEG precipitation method for detection of SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 785, 147270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metsalu, T.; Vilo, J. ClustVis: A web tool for visualizing clustering of multivariate data using Principal Component Analysis and heatmap. Nucleic Acids Research 2015, 43, W566–W570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeanne, L.; Bourdin, S.; Nadou, F.; Noiret, G. Economic globalization and the COVID-19 pandemic: Global spread and inequalities. GeoJournal 2022, 88, 1181–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali Swain, R.; Lin, X.; Wallentin, F.Y. COVID-19 pandemic waves: Identification and interpretation of global data. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada, B.I.; Zárate, S.; García-López, R.; Muñoz-Medina, J.E.; Gómez-Gil, B.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Sanchez-Flores, A.; Salas-Lais, A.G.; Roche, B.; Martínez-Morales, G.; Domínguez Zárate, H.; Duque Molina, C.; Avilés Hernández, R.; López, S.; Arias, C.F. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants BA.4 and BA.5 dominated the fifth COVID-19 epidemiological wave in Mexico. Microbial Genomics, 2023; 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguayo-Acosta, A.; Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Rodriguez-Aguillón, K.O.; Ovalle-Carcaño, A.; Romero-Castillo, K.D.; Robles-Zamora, A.; Johnson, M.; Parra-Saldívar, R.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E. Omicron and Delta variant prevalence detection and identification during the fourth COVID-19 wave in Mexico using wastewater-based epidemiology. IJID Regions 2024, 10, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolken, M.; Sun, T.; McCall, C.; Schneider, R.; Caton, K.; Hundley, C.; Hopkins, L.; Ensor, K.; Domakonda, K.; Kalvapalle, P.; Persse, D.; Williams, S.; Stadler, L.B. Wastewater surveillance of SARS-CoV-2 and influenza in preK-12 schools shows school, community, and citywide infections. Water Research 2023, 231, 119648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, D.; Quintela-Baluja, M.; Corbishley, A.; Jones, D.L.; Singer, A.C.; Graham, D.W.; Romalde, J.L. Making waves: Wastewater-based epidemiology for COVID-19 – approaches and challenges for surveillance and prediction. Water Research 2020, 186, 116404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, J.; Torres-Franco, A.; Rodriguéz, E.; Diaz, I.; Koritnik, T.; Silva, P.G.D.; Mesquita, J.R.; Trkov, M.; Paragi, M.; Muñoz, R.; García-Encina, P.A. Centralized and decentralized wastewater-based epidemiology to infer COVID-19 transmission – A brief review. One Health 2022, 15, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De La Cruz-Hernández, S.I.; Álvarez-Contreras, A.K. Omicron Variant in Mexico: The Fourth COVID-19 Wave. Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 2022, 16, 2260–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Nagata, M.H. An empirical overview of nonlinearity and overfitting in machine learning using COVID-19 data. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2020, 139, 110055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.; Cao, Y.; Wulff, S.S.; Robinson, T.J.; McGuire, A.; Bisha, B. A time series based machine learning strategy for wastewater-based forecasting and nowcasting of COVID-19 dynamics. Science of The Total Environment 2023, 897, 165105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ai, Y.; He, F.; Lancaster, E.; Lee, J. Application of machine learning for multi-community COVID-19 outbreak predictions with wastewater surveillance. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0277154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Arroyo, L.; Martínez-Ruiz, M.; Lucero, S.; Oyervides-Muñoz, M.A.; Wilkinson, M.; Melchor-Martínez, E.M.; Araújo, R.G.; Coronado-Apodaca, K.G.; Velasco Bedran, H.; Buitrón, G.; Noyola, A.; Barceló, D.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Sosa-Hernández, J.E.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Degradation of viral RNA in wastewater complex matrix models and other standards for wastewater-based epidemiology: A review. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 158, 116890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, C.S.; Self, S.; Rennert, L.; Kalbaugh, C.; Kriebel, D.; Graves, D.; Colby, C.; Deaver, J.A.; Popat, S.C.; Karanfil, T.; Freedman, D.L. COVID-19 wastewater epidemiology: A model to estimate infected populations. The Lancet Planetary Health 2021, 5, e874–e881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melvin, R.G.; Hendrickson, E.N.; Chaudhry, N.; Georgewill, O.; Freese, R.; Schacker, T.W.; Simmons, G.E. A novel wastewater-based epidemiology indexing method predicts SARS-CoV-2 disease prevalence across treatment facilities in metropolitan and regional populations. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 21368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, J.; Trowsdale, S.; Armstrong, B.A.; Chapman, J.R.; Carter, K.M.; Croucher, D.M.; Trent, C.R.; Sim, R.E.; Gilpin, B.J. Sensitivity of wastewater-based epidemiology for detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA in a low prevalence setting. Water Research 2022, 211, 118032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohring, J.; Leithäuser, N.; Wlazło, J.; Schulte, M.; Pilz, M.; Münch, J.; Küfer, K.-H. Estimating the COVID-19 prevalence from wastewater. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 14384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dye, C.; Barclay, W.S. (2024). Should we worry about a growing threat from “bird flu”? BMJ, q1199. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).