Submitted:

15 October 2024

Posted:

16 October 2024

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Changing from Research Questions to Purpose

- How can we adequately protect the health and safety of workers who work from home?

- How can supervisors effectively comply with their OHS responsibilities for at-home workers?

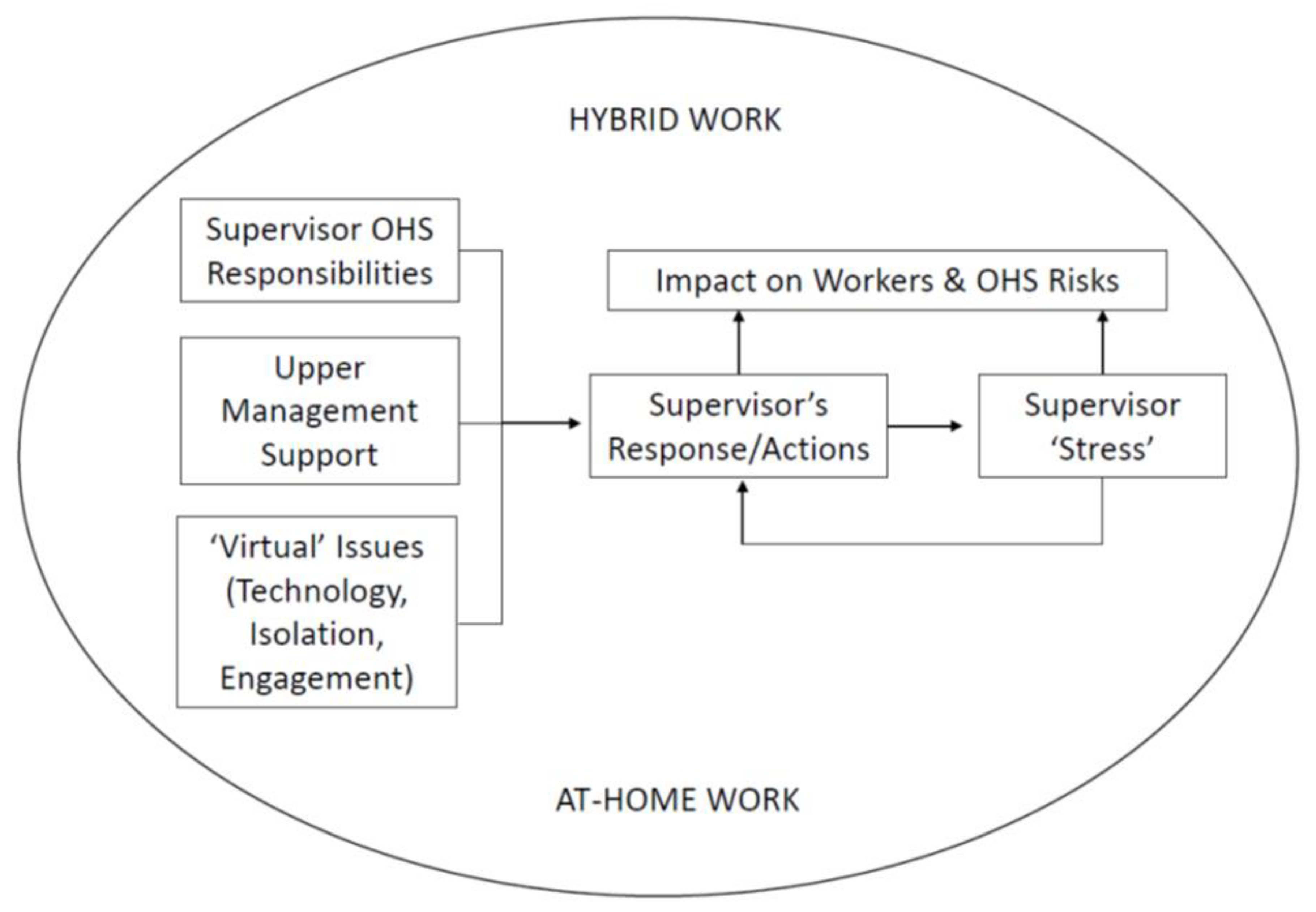

- Firstly, we have added to our understanding of the unique and complex experiences of supervisors because of the critical – but often uncomfortable -- role they play in most organizations. Supervisors hold a unique place in the hierarchy of a workplace. They are obliged to respond to workers’ needs, including being realistic about workloads and making demands, but they also need to respond to the requirements of upper management. This has led to a unique set of problems, challenges and issues faced by supervisors.

- Second, we have examined and improved our understanding of how supervisors have tried to continue to take responsibility for and execute their major occupational health and safety functions. Our study examined the stressors encountered by supervisors, the constraints they work under, and the distractions they encounter, all of which may be negatively affecting their ability to fulfil their OHS functions.

1.3. Project Description

1.4. Search Strategy for Evidence

2. Methods

2.1. Phases 1 and 2

2.1. Phase 3

3. Results

2.1. Standard Supervisor Functions – What Could Not Be Done?

In my head, it works like this. It's your house. We're telling you to do your job from your home. It should be a safe environment for you to do so. You know, we all have other things going on in our life, but it should be a safe location for you. So I think at one point we sent out [information on electrical safety -- like don't overload your plugs and crap like that, right? And don't run to any fire. [Don’t have too] many cords. Don't run them under your carpet, and stuff like that. But the adult who is employed by the employer should take some responsibility for their work environment, whether it is working in the workplace, or at home. We can give you guidelines to manage it. But it's really up to you to do it. (20)

Nobody has had an injury though. Nobody has said I've got a problem with my wrist, or I've got a specific problem, because you're making me sit at this awkward angle at my computer. I didn't have any. I didn't have any physical issues really that I can remember. (10)

In the field, there have been some job refusals, where people want to know if others in the group have been vaccinated, because they don't want to be in a cohort with someone who's not vaccinated. (8)

We're still in this moment of sort of lock down. We are not quite out of it. And I'm still trying to work with my community service staff. They always say, ‘Well, we're out in the community.’ Well, what does that mean, you're out in the community? ‘Are you working with a homeless person? Are you just out in the park checking on an opioid overdose, which we have lots of on the property? Like what are you actually doing?’ And then they look stressed and they say “We're doing really good work.” (10)

From a performance point, I find it exceptionally challenging. The tools that we have in place to track productivity, and how people move throughout their day aren't there. So when work is not to the quality that I expect it to be, I have lots of questions. One is: ‘Are you capable of doing it? Are you managing your time well? Is there a time management issue because you're working from home?’ I had a performance meeting with an employee last week. I actually gave her a letter of warning. I've never met her in person. I've met her on camera a couple of times. That is an instance where on a number of occasions I have asked her: ‘What have you been doing?’ And the response back hasn't been really reasonable, or she hasn't provided a reasonable explanation to how she's working or why the productivity isn't there. So I find that challenging as a manager, that's not something that would happen normally. Typically, in the same role when I was working in person, I could see people all the time and see when their productivity drops. (16)

I think, and I don't want to read people's minds, but I think that they believe that if they make it too difficult, I will say, ‘Oh, you can't work from home because it's too difficult’. [So they say:] “Oh, no, I'm fine. Everything's perfect. I feel no stress. I'm all good. It's all good.’ That's what I think. They are thinking, ‘Oh, well, if I say I need this, or if I say I fell, they're gonna say, well, it's not safe for you to work at home.’ I might be wrong. I don't think so though. I think that people are so keen on not wanting to go back to the office … [so they say:] ‘Everything's perfect.’ (17)

2.2. Standard Supervisory Functions – What Could Be Done?

So when the shift happened to go work at home, it was very quick and employees…took things from their office and brought them home. Many of us took our office chairs for example, and foot rests, and risers for monitors, and things of that nature…. And if they needed a mouse, for example … we'd look at getting that for them. The only thing was, if they wanted something fancy, like a sit-stand desk, they were probably on the hook to deal with that themselves. (1)

It was a challenge to outfit them at home, technology-wise…. for most people that have been working for 35 years prior to the pandemic…their Wi-Fi was only for, you know, Facebook, or basic leisure activities. It wasn't really set up for working or getting the signal that you need to get into our financial database…. So it was a challenge to get them outfitted with the technology they required, from laptops to tablets to cell phones. (19)

And so they got to a point where it became so frustrating for them that my worry was, you know, I didn't want to have a problem of turnover on my hands…. This one person, was saying, “No, I'm not into this technology. I just don’t want to do it”. I said, “Well, the reality is I can't come to your house and show you this thing, so we have to learn. Everybody's learning.” So it took a lot of patience. It took a lot of patience to work with this one particular staff, to walk her through how to use it. (4)

I'm here to coach and mentor him. [But] I can't sit down with him at the table and say, ‘This is what I want’, and have him look me in the eye so I could see that he understood what I was saying. His camera doesn't work on this computer. So I can't tell. I don't know if he understands me. I have no idea. Body language and eye contact are extremely important for me to understand if [workers] understand what I'm saying. And hearing ‘Uh huh.’ [is not enough for me] to think he got it. (15)

One of the big challenges [with virtual training] is that a competency check from an [online] exam does not equate to knowledge transfer. That's very obvious when it's a piece of equipment. And it's, “Hey, here's the auto scrubber. Here's how you use it.” Not that we had that on a digital video, but if we did, it still wouldn't translate to the same sort of competency check and kinesthetic learning.…And so I would say that that was a big transition. (6)

Horrible! I'm not doing a good job at [onboarding]. I’m just not. I just throw them to the wolves and hope that somebody is helping them with stuff. I mean, we have orientation checklists, but that’s not the same thing, right? …I don't know how, in a virtual world, to orient better. I just don't know. The connections are less easy to make, I guess. It’s hard to meet people. How do you get to know people? It's hard enough to make those connections with people who already know one another, let alone people who have not…. In that regard, I would say “Fail.” Like…it hasn't been easy for them. …And it's going to take them a longer time to get oriented because of just so many reasons. (13)

I'm a white heterosexual male. I know all the privilege that gives me today. And I mean, I'm learning as much as anybody, but I think there is value in trying to…test people objectively as much as possible by removing the bias that I know I have…I love having phone interviews. I never meet the person. (16)

2.3. Providing Workers with Social Support

I guess the stressors were the unknown. …or the mental health pieces. I knew some staff were maybe struggling with issues, either at home, issues because of children or ageing parents, parents getting sick. So a lot of it was the mental health piece, and some of my staff are more vulnerable to the mental health part of it perhaps. So understanding that people need more as we say, ‘Grace’. Or they need more time…. And I'd say “Just call me if there's something.” (10)

And then weekly, throughout the week, I connect with each person. I try and connect with everybody every day. So this morning I've already connected with six. So sometimes there's two or three people on a call together and we're talking about a specific business instance. But at least we're getting that interconnection. I'll text them to say, “You know what, I'm sorry, I didn't get to see you or connect today. Hope you had a great day.” So I’m really trying to keep in contact with them every day, just to let them know that I continue to be here, and to connect with each other as well, to keep that interconnection and support, team support going……(14)

We do icebreaker activities at the start of all of our meetings. I mean, for our team meetings, our staff meetings. Our billable time has gone down a little bit, because we're spending more time consciously and intentionally connecting, right. Whereas in the past I would do one staff meeting a month, now I do them weekly. So it takes more time. And it takes more effort, because you need to make sure your team is mentally okay. Like that's my number one priority….(2)

I'm in constant contact. I spoke with him this morning, I talked to him, I try to talk to him every day. I try to help him solve issues or problems he's going to be running into. I try to keep him as positive as I can. And I try to -- oftentimes he ends up making a bigger issue than what the issue actually is -- so my job really is just to make it simple and say, ‘Okay, here's what the issue is, and here's what I think you should be doing. Just don't look at anything else’…. And he’s like, ‘Okay, yeah, okay, thank you for that. I see what you mean’. (9)

2.4. From Supervision to Leadership

It was just the reality of the environment that we're working in. We needed to shift. And so the takeaway I would say is that it doesn't matter what level, how experienced you are, if anyone says they haven't shifted at all, or changed their leadership style or the way in which they're really engaging with their folks, I would say then, I don't really get that…..(11)

A learning for me was the big step change when [I realized] that you don't have to look over someone's shoulder for them to be productive. We can trust the person in a virtual environment. And when I say trust and credibility, I mean you have to build that…. But once you have that, it's up to them to break it, right? …. So what I'm saying is, my big learning is you can trust people in a remote workspace…. (5)

The other thing we have had to allow for is more flexibility of scheduling while working from home. So some of it is re-identifying what is okay and [what is] not okay as far as those time limits on work. Because I now have staff that work different hours.… Sometimes I've called them and because they see me as their leader calling, they answer the phone. But it's really not their work time. Like they're making dinner for their kids. Or they're doing a lesson with their kids. And I'm like, ‘Oh, I'm sorry’. I have to try to remember what are all their best work schedules. (11)

At the bi-weekly, we have a team meeting….And it's really just “ Ok, what's on the docket this week? What are you working on? What did get done? What are your plans for the next two weeks? And we sort of chat about priorities, and maybe course calibrate, or I share with them, you know, things that are new and hot off the press that they're not aware of…(8)

I give them the freedom to do what they need to do, to be treated as the experts. I'm like, “You guys tell me what you need and I'm here to support you.” And they value that. They're adults, they're educated, they're informed, they're responsible, and I think they respect that. And I hear that from them often. (14)

My staff want the flexibility to come to work sort of when they want to come to work. They want to be, I guess, self empowered to get their jobs done. And they don't want to really be questioned about what they're doing. That's the downside. They're very defensive, like: ‘I'm not telling you anything. I'm going to manage my world, and you're not going to ask me anything.’ (10)

I do find remotely, it is harder to get a sense of how productive people are, because you don't want to evaluate people purely on production. Some people on my team are like, overly productive. Like they're too quick to just jump into action and get things done without actually thinking things through or doing a proper assessment. And then I have the other range of people who I'm like, ‘Hello? Any movement on this one tiny thing? Like, can you close off on it?’ And I think because my team is so big, it's hard for me to follow every action through to completion. (18)

I feel like I lost that human connection piece, and the biggest challenge has been trying to replicate that in a virtual world. And now almost two years later, [it is hard to keep] that momentum going, times 12, in a workday, and being there to let them know that I'm here every moment of every day to support them…..(13)

2.5. Supervisors under Stress

I think one of the things that we lack is concern for the supervisor and some of the stress we've been under. When it comes to our psychological stress, how do supervisors manage that? I care about my team, and when I know that something is upsetting to them -- and over the pandemic a lot has been upsetting to them -- they've contacted me. And it's been emotionally exhausting for me, because I know how much they've struggled…. But being there for them meant sometimes I was on the phone until six o'clock at night, you know, walking them off the ledge…. How do we protect our supervisors psychologically? (Focus group)

I'm picking up the slack for my team from being overburdened…. They have been crazy busy. ….So I was working around the clock to say, “Oh my god. They have 100 emails in there.” And so I would work until 10 o'clock, responding to those messages, so that when they came in in the morning, they wouldn't feel that, ‘Oh my gosh. Look at all these messages. I can't do this.’ (17)

You're doing a meeting with people who have this much weight on them, right? And how do you individually flex or manage those people with whatever they have on their plate, [with so much in] their heads? It's exhausting. Yeah. And you're trying to make connections when you're tired of trying to make that happen in your home, let alone make it happen in the workplace. I've been making fake proms, fake grads, fake get-togethers, fake Christmases, fake Easters for [months]…. You’re trying to do that at work, and you're trying to [do that at home]. But you can't make people happy…. I think in reality I know I can't make it. I didn't create the global pandemic, right? I can't make it go away. But you do what you can to give people joy, right? And to motivate and you’re a leader. And yeah, it's hard…. It's exhausting! (13)

I don't know how to explain. He [the manager] was never really available. Unfortunately, he was quite busy. Same with the vice president now. Trying to get time to speak with someone is difficult because they're in meeting after meeting after meeting. So my interaction with him was very minimal, and then he retired in May, and then we didn't have the current VP until the end of June, and she was new to [our] industry completely. So it's been, it's been, fun! (3)

I've heard from some of the folks that I've worked with closest over the years, [who] have directly said, even just as late as Monday of this week, that this is probably the lowest morale, yeah, the lowest morale that they have felt in their workplace in the decade that they've been part of the team. And yeah, so extremely alarming, right? It's like, “Whoa what? What is going on? How does this end up in the ditch that far?” (7)

[They tried to make] policies and procedures about what it is that we as a workplace were supposed to do. … But then there was the corporate US office, trying to tell us what to do and not do. I think corporate US was also distracted, because they couldn't have one solidified answer. Their rules differed from state to state. So they had a struggle trying to level the playing field for everyone. …So there was a mishmash of a lot of different areas to look at for getting information. But you know, I stuck to the Ontario rules, federal rules, and then if CDC provided us with some additional guidance, that was great. But really, I just stuck to what was Canadian. So there was confusion. (20)

At the start of the pandemic, we had a few meetings with our leadership with: ‘Okay. Stay the course. We're here’, and ‘Mental health [is important]’, and you know, ‘We’ll keep in contact with everyone.’ And then eventually that stopped. So it's been probably over a year since we've had any sort of meaningful staff meetings with our President…(7)

They now love working from home. They love it. They don't want to go back to the office. That's been kind of the struggle. Every time we talk, and I think the longer we stayed home, the harder it's been to anticipate going back to the office. And I understand that because I'm feeling it too now. I love working from home. I miss seeing my office people. I do go in maybe once a month to the office, and I like it when I'm there. But for them, I would say 80% don't ever want to go to the office again, and the other 20% would like to go in maybe once every couple of weeks, or once a week. (17)

I don't want to open it up to be people's choice. I think as an employer of choice, we will accommodate people who need to work from home for whatever reason. But my opinion on that is that when people work from home, yeah, it might make their life better, but it's disrupting other’s [lives]. So that's another Zoom call that we need to take, that's another phone call. I can't just walk across the hallway. I lose something when my staff is working from home. Even though they may be comfortable, I'm inconvenienced, and they have to look at the other side. (15)

4. Discussion

- There were precursors to the COVID-19 pandemic such as SARS (that occurred in Canada in 2003), which emphasized the need for isolation, personal protective equipment, and vaccines. However, the shutdown during COVID-19 has highlighted the need to not only provide these physical protections, but also provide social support for the psychological health of supervisors and workers working from home.

- This study was conducted when workers and supervisors were still working from home all the time, and on the cusp of the change to beginning to come back to work. It is important to learn what we can from that time. However, we equally need to acknowledge that many workplaces have changed by adopting a hybrid work environment. What we learned during the intense shutdown period about the importance of the psychological health of workers working from home, continues to be very applicable to the hybrid work environment.

-

The Internal Responsibility System (IRS), which is the philosophical underpinnings to the Canadian occupational health and safety legislation, was challenged during the time of the COVID-19 shutdown. The challenge was primarily because supervisors did not have control over workers’ homes, and hence were unable to perform many of their OHS functions. The IRS needs to be reinterpreted and reconsidered within this current context, with the following recommendations:

- ○

- Increase and expand the OHS responsibilities of workers working from home since they have knowledge about and control over their home workspace.

- ○

- Make more explicit the OHS responsibilities of workers when they are not working in an employer-controlled workplace.

- ○

- Make more explicit supervisors’ responsibilities and limitation over all remote workers, whether they are working from home, or visiting clients.

- ○

- Expand the OHS responsibility of supervisors to emphasize their role in responding to workers’ needs whether that is educational or motivational.

4.1. Implications for Further Research

- Supervisors have challenges with the psychological health and safety (both of their employees and their own), and do not feel they are supported. The responsibility of upper management to be supportive of supervisors needs to be emphasized.

- Upper management should provide supervisors with the needed resources and training to be competent in dealing with workers who have psychological health and safety issues.

- The psychological health and safety of workers working from home, and supervisors’ responsibilities in this regard, may need to be explicitly outlined in OHS legislation, in the same way as violence and harassment have been.

- Hybrid work arrangements should be written into company policy, so that there are explicit expectations and enforcement of “anchor days” when workers need to come into the workplace. It should not be the supervisors’ responsibility to tell workers to come into the office.

- Difficult functions which could not effectively be done during the time of virtual work, such as training, onboarding, job performance and evaluation, and disciplining, are best handled in person during these “anchor days”.

4.2. Future Work

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coronavirus: How the world of work may change forever. 2020. BBC, Oct 25. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/worklife/article/20201023-coronavirus-how-will-the-pandemic-change-the-way-we-work (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- MacLeod, M. 2020. Is the great shift to working from home here to stay? CTV News, June 15. Available online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/coronavirus/is-the-great-shift-to-working-from-home-here-to-stay-1.4981456 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Choudhury, P. 2020. Our Work-from-Anywhere Future: Best practices for all-remote organizations. Harvard Bus Rev, Nov-Dec. Available online: https://hbr.org/2020/11/our-work-from-anywhere-future (accessed on 5 December 2022).

- Clarke, S.; Hardy, V. Working from home during the COVID-19 pandemic: How rates in Canada and the United Sates compare. Economic and Social Reports 2022, 2, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Nixon, G. 2022. COVID-19 changed office work. Here's what the 'next normal' looks like as people return. CBC News, Sept 4. Available online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/canada-return-office-wfh-fall-pandemic-1.6570575 (accessed on 19 December 2022).

- Faulds, D.J.; Raju, P.S. The work-from-home trend: An interview with Brian Kropp. Bus Horiz 2021, 64, 29-35. [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, P.; Khanna, T.; Makridis, C.; Schirmann, K. 2022. Is Hybrid Work the Best of Both Worlds? Evidence from a Field Experiment. Harvard Business School Technology & Operations Mgt. Unit Working Paper No. 22-063, Harvard Business School Strategy Unit Working Paper No. 22-063. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4068741 (accessed 19 December 2022).

- Constantz, J. 2022. Middle managers are not alright. Caught in the crossfire over remote work, they’re the most at risk of burnout. Fortune, Oct 20. Available online: https://fortune.com/2022/10/20/middle-managers-greatest-burnout-risk-return-to-work/ (accessed on 24 November 2022).

- Chu, A.M.Y.; Chan; T.W.C.; So, M.K.P. Learning from work-from-home issues during the COVID-19 pandemic: Balance speaks louder than words. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0261969. [CrossRef]

- Manroop, L.; Petrovski, D. Exploring layers of context-related work-from-home demands during COVID-19. Pers Rev 2023, 52, 1708-1727. [CrossRef]

- Eichenauer, C.J.; Ryan, A.M.; Alanis, J. M. Leadership During Crisis: An Examination of Supervisory Leadership Behavior and Gender During COVID-19. J Leadersh Org Stud 2021, 29, 190-207. [CrossRef]

- Charalampous, M.; Grant, C.A.; Tramontano, C. “It needs to be the right blend”: a qualitative exploration of remote e-workers’ experience and well-being at work. Empl Relat 2022, 44, 335-355. [CrossRef]

- Crawford, J.O.; MacCalman, L.; Jackson, C.A. The health and well-being of remote and mobile workers. Occup Med-C 2011; 61, 385–394. [CrossRef]

- Guidetti, G.; Cortini, M.; Fantinelli, S.; Di Fiore, T.; Galanti, T. Safety Management and Wellbeing during COVID-19: A Pilot Study in the Manufactory Sector. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022, 19, 3981. [CrossRef]

- Mihalache, M.; Mihalache, O.R. How workplace support for the COVID-19 pandemic and personality traits affect changes in employees' affective commitment to the organization and job-related well-being. Hum Resour Manage 2022, 61, 295–314. [CrossRef]

- Parker, S.K.; Axtell, C.M.; Turner, N. Designing a safer workplace: Importance of job autonomy, communication quality, and supportive supervisors. J Occup Health Psychol 2001, 6, 211–228. [CrossRef]

- Urbaniec, M.; Małkowska, A.; Włodarkiewicz-Klimek, H. The Impact of Technological Developments on Remote Working: Insights from the Polish Managers’ Perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 552. [CrossRef]

- Gjerde, S.; Alvesson, M. Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Hum Relat2020, 73, 124-151. [CrossRef]

- McConville, T.; Holden, L. The filling in the sandwich: HRM and middle managers in the health sector. Pers Rev 1999, 28, 406-424. [CrossRef]

- de Jong, J.P.; Clinton, M.; Bal, M.; Van Der Heijden, B. Caught in the Middle: How and When Psychological Contract Breach by Subordinates Relates to Weekly Emotional Exhaustion of Supervisors. Front Psychol 2021, 11, 464774. [CrossRef]

- Plummer, I.M.; Strahlendorf, P.W.; Holliday, M.G. The Internal Responsibility System in Ontario Mines: Final Report. Queen’s Printer for Ontario: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2000.

- Strahlendorf, P.W. The Internal Responsibility System. Occupational Health and Safety Canada 2001; March: 30-42.

- Strahlendorf, P.W. What Supervisors Need to Know. Occupational Health and Safety Canada, January/February, 1996.

- Strahlendorf, P.W. Doomed if You Don't: Supervisory Due Diligence. Occupational Health & Safety Canada 1998, 14, 34-42.

- Strahlendorf, P.W. Do You Know Your Responsibilities as a Supervisor? Workplace Environment Health & Safety Reporter, Nov 1999, p. 942.

- Karasek, R.; Theorell, T. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. Basic Books: New York, NY, USA, 1990.

- Kramer, D.M.; Cole, D.C.; Leithwood, K. Doing Knowledge Transfer: Engaging management and labour with research on employee health and safety. B Sci Technol Soc 2004, 24, 316-330. [CrossRef]

- Sargent, L.D.; Terry, D.J. The moderating role of social support in Karasek's job strain model. Work Stress 2000, 14, 245-261. [CrossRef]

- Van der Doef, M.; Maes, S. The job demand-control(-support) model and physical health outcomes: A review of the strain and buffer hypotheses. Psychol Health 1998, 13, 909-936. [CrossRef]

- Mehdi, T.; Morissette, R. Working from home in Canada: what have we learned so far? Economic and Social Reports 2021, 1, 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Needleman, C.; Needleman, M.L. Qualitative methods for intervention research. Am J Ind Med 1996, 29, 329-337. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, E.; Kramer, D.M.; Strahlendorf, P.; Holness, D.L.; Kushner, R.; Tenkate, T. A cross-Canada knowledge transfer and exchange workplace intervention targeting the adoption of sun safety programs and practices: Sun Safety at Work Canada. Safety Sci 2018, 102, 238-250. [CrossRef]

- Kramer, D.M.; Haynes, E.; McMillan, K.; Lightfoot, N.E.; Holness, D.L. 2018. Iterative method of analysis of 90 interviews from two communities: Understanding how Sudbury and Sarnia reduced occupational exposures and industrial pollution. In Sage Research Methods Cases Part 2. SAGE Publications Ltd. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781526443779 (accessed on 20 December 2022).

- Kushner, R.; Kramer, D.M.; Holness, D.L. Feasibility of clinicians asking patients about their exposure to occupational hazards: An intervention at five primary care health centres. Work 2018, 60, 365-384. [CrossRef]

- Tenkate, T.; Kramer, D.M.; Strahlendorf, P.; Szymanski, T. Setting priorities: Testing a tool to assess and prioritize workplace chemical hazards. Work 2021, 70, 85-98. [CrossRef]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013, 13, 117. [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Sourcebook of New Methods. Sage Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1984.

- Seale, C. Quality in Qualitative Research. Qual Inq 1999, 5, 465-478. [CrossRef]

| Participant Number |

Gender | Title | # people WFH reporting to them | Industry | Province |

| 1 | F | Manager of training and standards | 3 | Forestry | B.C. |

| 2 | M | Manager procurement | 14 | Federal Public Sector | B.C. |

| 3 | F | Freight claims | 3 | Trucking | N.S. |

| 4 | M | Integrated facilities managers | 8 | Healthcare | Ontario |

| 5 | M | Safety and Assurance | 25 | Utilities | B.C. |

| 6 | M | Director OHS | 4 | Education | B.C. |

| 7 | M | Director OHS | 7 | Education/OHS | B.C. |

| 8 | F | Snr Manager, National Training | 8 | Manufacturing | Ontario |

| 9 | M | Manager Strategic Programs | 5 | Education/OHS | Ontario |

| 10 | F | Director of Administration | 11 | Charitable/Religious | Ontario |

| 11 | F | VP Human Resources | 5 | Insurance | Ontario |

| 12 | F | Owner | 15 | OHS Consulting | B.C. |

| 13 | F | Director | 12 | NGO/Healthcare | Ontario |

| 14 | F | Managing Coordinator | 14 | Municipal Public Sector | Ontario |

| 15 | F | Manager, Safety and Compliance | 4 | Maritime Services, Energy | Newfoundland |

| 16 | M | Manager, Central Staffing | 18 | Healthcare | Nova Scotia |

| 17 | F | Manager, Customer Care | 10 | Education/OHS | Ontario |

| 18 | F | Director, Marketing | 9 | Education/OHS | Ontario |

| 19 | M | Public Works Manager | 7 | Municipal Public Sector | N.S. |

| 20 | F | Director OHS | 20 | Utilities | Ontario |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).